Abstract

Purpose

Gender nonconformity, that is, transgressing conventionally “masculine” vs. “feminine” characteristics, is often stigmatized. Stigmatization and discrimination are social stressors that raise risk of adverse mental and physical health outcomes and may drive health inequities. However, little is known about the relationship between such social stressors and health-related quality of life (HRQOL). This paper aimed to examine associations between perceived gender nonconformity and HRQOL in a cohort of U.S. adolescents and young adults.

Methods

Using data from 8,408 participants (18–31 years) in the U.S. Growing Up Today Study (93% white, 88% middle-to-high income), we estimated risk ratios (RRs) for the association of gender nonconformity (3 levels: highly gender conforming, moderately conforming, and gender nonconforming) and HRQOL using the EuroQol questionnaire (EQ-5D-5L). Models were adjusted for demographic characteristics, including sexual orientation identity.

Results

Gender nonconformity was independently associated with increased risk of having problems with mobility (RR [95% confidence interval]: 1.76 [1.16, 2.68]), usual activities (2.29 [1.67, 3.13]), pain or discomfort (1.59, [1.38, 1.83]) and anxiety or depression (1.72 [1.39, 2.13]), after adjusting for sexual orientation and demographic characteristics. Decrements in health utility by gender nonconformity were observed: compared to persons who were highly gender conforming, mean health utility was lower for the moderately gender conforming (beta [SE]: −.011 [.002]) and lowest for the most gender nonconforming (-.034 [.005]).

Conclusions

In our study, HRQOL exhibited inequities by gender nonconformity. Future studies, including in more diverse populations, should measure the effect of gender-related harassment, discrimination, and violence victimization on health and HRQOL.

Keywords: masculinity, femininity, stigma, EQ5D, gender nonconformity, health-related quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Adolescents and young adults who have a nonconforming gender expression—that is, who visibly transgress societal gender norms and expectations for their perceived gender—are at heightened risk of social and physical stressors such as harassment, discrimination, and violence victimization [1–4]. Sexual minority stress theory posits that such social stressors may drive mental and physical health inequities in sexual minorities compared to heterosexuals [5, 6]. Mounting evidence points to the serious mental health consequences of these social determinants for persons who are gender nonconforming, whether or not they are also sexual minorities [7–11], suggesting that physical health outcomes also warrant attention. Stigma and discrimination based on gender, race, and sexual orientation have been associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease, pain, physical functioning, disability, and overall poor physical health status [12–19]. Stigma has also been linked to reduced personal wellbeing and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) for those with specific health conditions, such as HIV or Parkinson’s Disease [20–22]. However, we are not aware of studies analyzing gender nonconformity and HRQOL in non-clinical populations of young people.

Given the importance of stigmatization and discrimination [23], more research is needed on the potential physical as well as mental health impacts of socially assigned gender nonconformity, that is, the extent to which a person is perceived by others as transgressing conventionally “masculine” vs. “feminine” characteristics [24]. In addition, studies of masculine gender conformity support need for closer investigations of the health consequences associated with the spectrum of gender conformity and nonconformity. Higher levels of conformity to masculinity norms have been linked to alcohol, tobacco, and illegal substance use, to greater depressive symptomology, and to medical mistrust in men [25–30], all of which might influence HRQOL. Though fewer, studies of gender nonconformity among men and women have found varying associations with cancer-related health behaviors, such as physical activity, chewing tobacco, and tanning bed use [31, 32]. For example, some studies have found that inclination towards stereotypically “feminine” norms is associated with less physical activity in young men and young women [31, 33], with implications for HRQOL. Some research suggests that health impacts of gender conformity and nonconformity may differ for women and men, but findings are mixed [7, 8, 31, 32] and there is a need to better understand gender-based differences across multiple health domains and in relation to overall HRQOL.

The present study investigated whether self-reported appraisal of socially assigned gender nonconformity was associated with overall HRQOL in a cohort of adolescents and young adults. HRQOL is a critical indicator of population health and wellbeing that can be used to quantify: (a) the public health toll of adverse exposures, including harassment, discrimination, or violence due to gender nonconforming and (b) the cost-effectiveness of interventions, e.g., initiatives to reduce stigma.

Following from our conceptualization of socially assigned gender nonconformity as a potential indicator of exposure to stigma-related social stressors, we hypothesized that:

Study participants who reported higher levels of socially assigned gender nonconformity would have reduced HRQOL in young adulthood after accounting for sexual orientation, including greater risk of poor mental health (anxiety or depressive symptoms), greater risk of physical health limitations (limitations in mobility and usual activities and problems with pain), and lower health utility scores, compared to participants who reported less gender nonconformity.

Moderator effects by gender will be observed, whereby there will be a stronger association between gender nonconformity and lower HRQOL in women than in men (with the hypothesis that gender nonconforming women are more likely than gender nonconforming men to engage in conventional masculine behaviors associated with physical risk-taking and substance use, reducing HRQOL [26, 34]).

METHODS

Participants

Participants were drawn from the Growing Up Today Study (GUTS), a U.S. cohort study of children of women in the Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII) that began in 1996 with 16,882 children ages 9–14 years (GUTS1) and was expanded in 2004 with 10,923 additional participants ages 9–15 years (GUTS2). Both women in the Nurses’ Health Study and their children have been primarily white and from middle-to-high income families.

GUTS participants have been sent questionnaires (paper and online formats) annually or biennially. The current analyses include 8,408 individuals who provided information on the key predictor, gender expression, in 2010–2011 and on the key outcome, HRQOL, in 2013; individuals missing vs. not missing these data had similar sociodemographic characteristics, with the exception of being slightly more likely to be male (37% vs 30%; p<0.001) and self-identified as being completely heterosexual (85% vs. 82%; p<0.01). Transgender-identified participants were excluded (n=18) as this group was too small for analysis. We used multiple imputation to adjust for covariate missingness (household income, n=1,503; sexual orientation identity, n=34). The Brigham & Women’s Hospital Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Measures

Primary predictor: Gender nonconformity

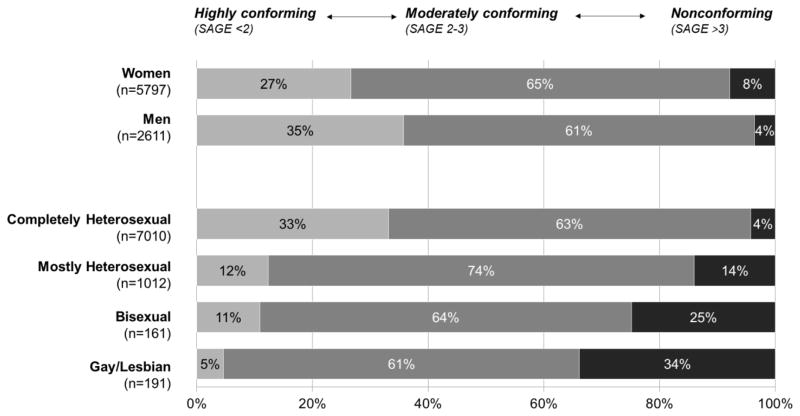

Gender nonconformity was measured using two variables: (1) the participant’s gender as reported at baseline ; and (2) the Socially Assigned Gender Expression (SAGE) Scale, a two-item self-report measure that has been validated through cognitive testing [24, 35] and which was administered in 2010–2011 when participants were 16–29 years old. For the SAGE Scale, respondents self-reported how they thought people would, on average, describe their (a) appearance, style, or dress and (b) mannerisms. Response options ranged on a seven-point scale from “very masculine” to “very feminine.” The two items were recoded relative to participant’s gender (e.g., “very feminine” coded as 1 for women and 7 for men) and summed to produce a gender nonconformity summary score (range: 1 to 7) where low scores indicate high socially assigned gender conformity and high scores indicate high nonconformity. Based on the distribution of scores and the study’s focus on gender nonconformity relative to gender conformity, this score was used to construct three analytic categories: (1) Highly gender conforming (score <2); (2) Moderately gender conforming (score 2–3); and (3) Most gender nonconforming (score>3; corresponds to any report of being feminine among men, masculine among women, or “equally feminine/masculine”). Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of these groups by gender and sexual orientation identity in the study sample.

Fig 1.

Socially assigned gender expression in three categories by gender and sexual orientation identity among young men and women in the Growing Up Today Study 2010–2013 (US; n=8,408)

Note: Sexual orientation identity categories do not add up to 8,408 due to missing information on sexual orientation identity (n=34).

Outcome: Health-related quality of life (HRQOL)

HRQOL was assessed using the EuroQol-5D-5L (EQ-5D) [36]. The instrument asks about degree of health problems along five dimensions: mobility, self-care (e.g., dressing oneself), usual activities (e.g., housework, leisure), pain or discomfort, and anxiety or depression, with five response categories for each (from no problems to extreme problems). Following recommendations from the EuroQol group [36] and based on the low expected prevalence of functional limitations in a young non-clinical cohort such as GUTS, outcomes in each physical functioning dimension (mobility, self-care, usual activities) and pain/discomfort were dichotomized into “no problems” (1) vs. “any problems” (2–5). Responses on anxiety/depression were dichotomized into “none or slight problems” (1–2) vs. “moderate, severe, or extreme problems” (3–5), following prior EQ-5D classifications [37, 38].

Responses were converted into health utility scores using the standard U.S. preference-weighted health utility algorithm [39]. As EQ-5D-5L value sets were not yet available for the U.S., we relied on a crosswalk value set, which maps EQ-5D-5L responses to the former EQ-5D-3L instrument [40]. These responses generate a total of 243 possible health states, which are then converted into a summary index by applying scores from a valuation set derived from a probability sample of English- and Spanish-speaking U.S. adults [41]. This results in a U.S.-specific estimated health utility, calibrated to reflect the degree to which different health statuses are valued in the U.S. population overall. Index values for the U.S. population range from most severe impairment on all five dimensions, considered a state “worse than death” (value= −0.109), to full health (value=1.0) [42].

Covariates

Age at questionnaire return was assessed in 2013 (range: 18–31 years in 2013). We used annual household income in 2001 (when participants were ages 7 to 19 years) as this was the only available indicator of childhood socioeconomic position (SEP). This was reported by mothers and coded categorically (<$40,000, $40–49,999, $50–74,999, $75–99,999, $100,000+). Self-reported sexual orientation identity was collected on the same wave as SAGE (2010–2011) and coded as sexual minority (mostly heterosexual, bisexual, or gay/lesbian/homosexual) or completely heterosexual; 2013 report of sexual orientation identity was used for those missing 2010–2011 data (n=651). Data on race/ethnicity were provided by self-report and are displayed for descriptive purposes (Table 1); we did not include this covariate in the analyses because inclusion had no impact on results.

Table 1.

Distribution of participant characteristics for variables included in the analyses, by socially assigned gender nonconformity group among men and women (ages 18–31 years) in the Growing Up Today Study 2010–2013 (US; n=8,408)

| Total (n=8408) | Highly gender conforming (n=2472, 29%) | Moderately gender conforming (n=5380, 64%) | Gender nonconforming (n=556, 7%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | p-valuea | |||||

| Age (Years) | 0.001 | ||||||||

| 18–22 yrs | 23.4 | (1967) | 24.7 | (610) | 22.2 | (1196) | 29.0 | (161) | |

| 22–27 yrs | 40.4 | (3398) | 39.4 | (975) | 40.9 | (2201) | 39.9 | (222) | |

| 28–31 yrs | 36.2 | (3043) | 35.9 | (887) | 36.9 | (1983) | 31.1 | (173) | |

| Gender | <.0001 | ||||||||

| Men | 31.1 | (2611) | 37.7 | (931) | 29.5 | (1585) | 17.1 | (95) | |

| Women | 69.0 | (5797) | 62.3 | (1541) | 70.5 | (3795) | 82.9 | (461) | |

| Childhood Household Income (Annual)b | 0.03 | ||||||||

| <$40,000 | 5.6 | (384) | 6.9 | (140) | 5.0 | (219) | 5.3 | (25) | |

| $40–49,999 | 6.7 | (466) | 6.3 | (127) | 6.7 | (297) | 8.9 | (42) | |

| $50–74,999 | 23.7 | (1641) | 24.1 | (489) | 23.4 | (1035) | 24.7 | (117) | |

| $75–99,999 | 21.7 | (1501) | 20.5 | (416) | 22.4 | (989) | 20.3 | (96) | |

| $100,000+ | 42.3 | (2931) | 42.3 | (858) | 42.5 | (1879) | 40.9 | (194) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.0005 | ||||||||

| White | 93.3 | (7761) | 94.3 | (2305) | 93.2 | (4963) | 89.3 | (493) | |

| Black/African American | 0.6 | (50) | 0.7 | (18) | 0.5 | (27) | 0.9 | (5) | |

| Latino/Hispanic | 2.0 | (162) | 1.4 | (33) | 2.2 | (117) | 2.2 | (12) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1.8 | (147) | 1.4 | (35) | 1.8 | (94) | 3.3 | (18) | |

| Another race; Multiracial | 2.4 | (200) | 2.2 | (54) | 2.3 | (122) | 4.4 | (24) | |

| Sexual Orientation Identityc | <.0001 | ||||||||

| Completely heterosexual | 83.7 | (7010) | 93.8 | (2317) | 82.0 | (4391) | 55.0 | (302) | |

| Mostly heterosexual | 12.1 | (1012) | 5.1 | (126) | 13.9 | (745) | 25.7 | (141) | |

| Bisexual | 1.9 | (161) | 0.7 | (18) | 1.9 | (102) | 7.5 | (41) | |

| Gay/Lesbian | 2.3 | (191) | 0.4 | (9) | 2.2 | (117) | 11.8 | (65) | |

| Outcomes: Dimensions of HRQOLd | |||||||||

| Mobility | 3.9 | (327) | 2.8 | (70) | 4.0 | (215) | 7.6 | (42) | <.0001 |

| Self-care | 0.7 | (60) | 0.5 | (13) | 0.7 | (39) | 1.4 | (8) | 0.07 |

| Usual Activities | 5.9 | (495) | 4.1 | (102) | 5.9 | (316) | 13.9 | (77) | <.0001 |

| Pain or Discomfort | 28.0 | (2352) | 23.0 | (569) | 29.1 | (1566) | 39.0 | (217) | <.0001 |

| Anxiety or Depression | 13.6 | (1139) | 10.8 | (267) | 13.6 | (731) | 25.4 | (141) | <.0001 |

| Outcomes: HRQOL (Health Utility) | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) HRQOL | 0.908 | (0.094) | 0.922 | (0.090) | 0.905 | (0.093) | 0.871 | (0.104) | <.0001 |

Note: Data presented are raw data with no imputation for missingness. Sample does not include respondents with no information on socially assigned gender nonconformity or any of the five EQ-5D-5L dimensions.

. P-values based on Chi-square tests for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variable.

. Household income assessed via maternal report in 2001 when participants were ages 7–19 years.

. Sexual orientation identity was measured on the same wave as gender nonconformity (2010/2011); 2013 sexual orientation identity responses were used for those missing 2010/2011 (n=651).

. Five dimensions of EQ-5D-5L used to construct HRQOL index score. Dimensions show percent reporting any problems with mobility, self-care, usual activities or pain/discomfort; percent reporting moderate-to-extreme problems with anxiety/depression as reported in 2013 using EQ-5D-5L measure of health-related quality of life.

Analysis

We examined the association between gender nonconformity at ages 16–29 years and outcomes at ages 18–31 years, including: (1) risk of poor health in each of the five health dimensions of the EQ-5D and (2) overall preference-weighted HRQOL scores. After fitting bivariate models to assess crude associations, we used multivariable regression to account for potential confounders (age, gender, childhood SEP, sexual orientation identity, GUTS1 vs. GUTS2 cohort). Because some mothers enrolled more than one child in the GUTS cohort, we used generalized estimating equations (GEE) and the robust sandwich estimator to account for within-family clustering [43]. Throughout, we used a log link function to estimate adjusted relative risks for each EQ-5D dimension modeling combined levels 2–5 vs. 1 (or 3–5 vs. 1, for anxiety/depression) and, given the large sample size we used an identity link function to estimate changes in overall utility as a linear function of gender nonconformity. We tested for interactions between gender nonconformity and gender; we present both aggregated and gender-stratified results for all outcomes.

We implemented multiple imputation methods to account for uncertainty due to missing data on covariates (childhood SEP and sexual orientation identity) [44, 45], using SAS PROC MI with the FCS logistic specification and PROC MIANALYZE [46]. We checked the sensitivity of our findings by comparing the results using multiply imputed values to findings using complete case analysis as well as inverse probability weighted analyses and found no substantive differences in results. We also conducted sensitivity analyses in which we used two alternative cut-points to identify those in the most gender nonconforming group: a lower cut-point of 3 for the whole sample (gender nonconforming group=15.2%), and a more stringent cut-point of 4 in a sample restricted to women (gender nonconforming women=4.5%, not possible for men due to small sample size). All analyses were conducted using SAS v9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

The study sample included 2,611 men and 5,797 women. Participants were 93% white and 88% had mothers who reported an annual household income ≥ $50,000 in 2001 (when participants were ages 7–18 years). Approximately 4% of young men and 8% of young women reported high levels of socially assigned gender nonconformity (Figure 1). As shown in Table 1, socially assigned gender nonconformity was significantly more common among women than men (p<.0001) and among those who identified as sexual minorities compared to their heterosexual counterparts (p<.0001).

Prevalence of functional limitations was relatively low, as expected in a young non-clinical sample: 4% reported currently experiencing any mobility limitations, <1% reported any self-care limitations, and 6% reported any limitations in usual activities. In addition, 28% of participants reported pain or discomfort and nearly 14% reported moderate-to-severe levels of anxiety or depressive symptoms. In bivariate analyses there were significant positive associations between higher levels of gender nonconformity and poorer health status in young adulthood for all dimensions (p<.0001) with the exception of self-care (p=.07). Overall, the mean HRQOL health utility score was 0.908 (SD=0.094). In bivariate analyses, higher levels of gender nonconformity were associated with poorer HRQOL: mean health utility was 0.922, 0.905, and 0.871 among persons who were highly gender conforming, moderately gender conforming, and gender conforming, respectively (p<0.0001).

In multivariable models (Table 2), participants reporting the highest levels of gender nonconformity experienced higher risk of health problems relative to those who were highly gender conforming on four dimensions: mobility limitations, usual activities limitations, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. For example, those who were most gender nonconforming had 2.3 times greater risk of reporting limitations in their usual activities compared to those who were most gender conforming (RR=2.29, 95% CI: 1.67, 3.13).

Table 2.

Results of multivariable analysis of EQ-5D health dimensionsa and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) by gender nonconformityb (GNC) among men and women (ages 18–31 years) in the Growing Up Today Study 2010–2013 (US; n=8,408)

| Base Modelsc | Fully Adjusted Modelsd | Fully Adjusted Models by Gender | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Men (n=2611) | Women (n=5797) | |||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| EQ-5D Dimensions | RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | ||||

| MOBILITY | ||||||||||||

| GNC (Ref=highly conforming) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Moderate level | 1.40 | (1.08, 1.83) | 1.24 | (0.93, 1.65) | 1.25 | (0.94, 1.66) | 1.25 | (0.89, 1.76) | ||||

| Most nonconforming | 2.68 | (1.85, 3.88) | 1.76 | (1.16, 2.68) | 1.81 | (1.19, 2.76) | 1.99 | (1.27, 3.13) | ||||

| SELF-CARE | ||||||||||||

| GNC (Ref=highly conforming) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Moderate level | 1.37 | (0.73, 2.58) | 1.18 | (0.59, 2.37) | na | na | 0.94 | (0.44, 2.00) | ||||

| Most nonconforming | 2.88 | (1.20, 6.89) | 1.87 | (0.68, 5.10) | na | na | 1.98 | (0.71, 5.57) | ||||

| USUAL ACTIVITIES | ||||||||||||

| GNC (Ref=highly conforming) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Moderate level | 1.39 | (1.12, 1.73) | 1.28 | (1.01, 1.64) | na | na | 1.48 | (1.10, 1.98) | ||||

| Most nonconforming | 3.17 | (2.40, 4.18) | 2.29 | (1.67, 3.13) | na | na | 2.60 | (1.82, 3.71) | ||||

| PAIN OR DISCOMFORT | ||||||||||||

| GNC (Ref=highly conforming) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Moderate level | 1.25 | (1.15, 1.36) | 1.21 | (1.11, 1.33) | 1.15 | (0.98, 1.34) | 1.25 | (1.11, 1.40) | ||||

| Most nonconforming | 1.69 | (1.49, 1.92) | 1.59 | (1.38, 1.83) | 1.09 | (0.72, 1.65) | 1.69 | (1.44, 1.97) | ||||

| ANXIETY OR DEPRESSION | ||||||||||||

| GNC (Ref=highly conforming) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Moderate level | 1.25 | (1.10, 1.43) | 1.18 | (1.02, 1.37) | 1.44 | (1.09, 1.89) | 1.07 | (0.90, 1.27) | ||||

| Most nonconforming | 2.31 | (1.92, 2.78) | 1.72 | (1.39, 2.13) | 1.82 | (1.09, 3.04) | 1.63 | (1.29, 2.06) | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| EQ-5D Health Utility Index | Beta | (SE) | p-value | Beta | (SE) | p-value | Beta | (SE) | p-value | Beta | (SE) | p-value |

|

| ||||||||||||

| OVERALL HRQOL | ||||||||||||

| GNC (Ref=most conforming) | ||||||||||||

| Middle level | −0.017 | (0.002) | <.0001 | −0.011 | (0.002) | <.0001 | −0.014 | (0.004) | 0.001 | −0.009 | (0.003) | 0.003 |

| Most nonconforming | −0.051 | (0.005) | <.0001 | −0.034 | (0.005) | <.0001 | −0.030 | (0.012) | 0.02 | −0.033 | (0.006) | <.0001 |

na = Could not estimate due to small sample size. Bold effect estimates are statistically significant (p<.05).

. EQ-5D health dimensions risk ratios (RRs) represent the relative risk of reporting any problems (slight, moderate, severe, or completely unable) vs. no problems with the following: (1) Mobility = walking about; (2) Self-care = washing or dressing myself; (3) Usual activities = usual activities, e.g., work, study, housework, family, or leisure activities; (4) pain or discomfort; or represent the risk of reporting moderate, severe or extreme problems vs. no or slight problems with (5) being anxious or depressed.

. GNC = Gender nonconformity (assessed in 2010 for GUTS1 and 2011 for GUTS2 using Socially Assigned Gender Expression scale and participant gender). Continuous scale score (range: 1–7, with higher scores representing greater nonconformity to gender expectations relative to gender) was classified into 3 categories: 1=Most conforming (Score <2), 2=Middle level of conformity/nonconformity (Score 2–3), 3=Most nonconforming (Score >3).

. Base models adjust for age (in years, continuous), gender (men (ref) vs. women), and cohort (GUTS2 (ref) vs. GUTS1).

. Fully adjusted models additionally adjust for annual household income in childhood ($40K/year, $40–49K, $50–74K, $75–99K, $100K (ref)), and most recent report of sexual orientation identity (completely heterosexual (ref) vs. gay/lesbian, bisexual, or mostly heterosexual). Multiple imputation implemented to address covariate missingness (household income and sexual orientation identity). Gender not included in stratified models.

. RRs represent the relative risk of reporting less than perfect health (HRQOL index score <1) compared to perfect health (index score = 1)

. Restricted health utility index score models restricted to those with a health utility score <1 (n=4,721)

Gender partially modified the associations between gender nonconformity and pain and anxiety/depressive symptoms (pain: p<.05 for gender-by-highly-gender nonconforming interaction term; anxiety/depression: p<.05 for gender-by-moderately gender conforming); interaction terms for usual activities were marginally significant (p for gender-by-moderate gender conformity =.10). Young women reporting the highest levels of gender nonconformity had over two times greater risk of reporting limitations in their usual activities (RR=2.60, 95% CI: 1.82, 3.71) and 1.7 times greater risk of reporting problems with pain (RR=1.69, 95% CI: 1.44, 1.97) compared to young women reporting highest gender conformity. In addition, a gradient was observed within these dimensions, such that each level of gender nonconformity was significantly associated with greater risk of mobility and usual activities limitations and pain in young women. Among young men, the associations with mobility, usual activities, and pain were not statistically significant or could not be estimated due to sample size limitations. However, the association between gender nonconformity and anxiety/depressive symptoms was significantly greater magnitude among young men than among young women, particularly for men in the moderately gender conforming group. Gender nonconforming young men had the highest risk of anxiety/depressive symptoms, relative to highly gender conforming men, followed by moderately conforming men.

In linear regression models examining the association between gender nonconformity and overall health utility score, a gradient was also observed: the most gender nonconforming group, on average, experienced a statistically significant 0.034 unit decrement in health utility relative to the most gender conforming group (SE=.005, p<.0001), while the moderately conforming group has a 0.011 unit decrement in health utility compared to their highly gender conforming peers. We did not find support for our hypothesis of moderation by gender in the health utility analyses.

DISCUSSION

Our findings provide novel evidence of a relationship between socially assigned gender nonconformity and risk for poor HRQOL in a U.S. cohort of primarily white young adults raised in middle-to-upper income households, independent of sexual orientation. Young adults in this study who reported being perceived as gender nonconforming (i.e., more feminine males and more masculine females) had higher risk of functional limitations with regards to mobility and usual activities as well as higher risk of experiencing pain and anxiety or depressive symptoms compared to those perceived as highly gender conforming. There was partial evidence of effect measure modification by gender, including a significant relationship between gender nonconformity and mobility limitations, usual activities limitations, and pain among young women but not young men. Further, there was a higher magnitude relationship between gender nonconformity and anxiety/depressive symptoms among men at all levels of gender nonconformity than among women. We also found that gender nonconformity was significantly associated with decrements in health utility, but moderation by gender was not statistically significant. Although there is no standard delineating what change in health utility score would constitute a clinically important difference, the difference in mean health utility between gender nonconforming and the most conforming respondents (0.871 vs. 0.922 , difference of 0.051, p<0.001) exceeds the minimally important difference in HRQOL identified in prior research (0.03 and 0.05 units difference) [42, 47].

Our findings regarding elevated anxiety/depressive symptoms are consistent with prior studies demonstrating that gender nonconforming young people are at elevated risk of negative mental health outcomes such as depressive symptoms, anxious symptoms, PTSD, self-harm behaviors, and suicidality [7–9, 48–52]. Our findings on mobility and usual activities limitations and pain are new contributions; little, if any, prior research has examined these elements of HRQOL in relation to gender nonconformity in young adults. To the best of our knowledge this is also the first study to document the association between gender nonconformity and health utility.

Several pathways could potentially link gender nonconformity to HRQOL, which incorporates multiple dimensions of physical and mental health status. The minority stress framework posits that discrimination and violence targeting gender nonconformity act as social stressors that impact mental health via psychological and physiological stress responses [4, 5, 53]. In the GUTS cohort, childhood abuse (exposure to violence) has been shown to mediate the relationship between childhood gender nonconformity and adolescent depressive symptoms [8]. This might also extend to pain and functional limitations as many pain and somatic disorders, including chronic pain syndromes, functional abdominal pain, chronic headaches, and arthritis have been associated with a history of abuse [54]. Exposure to violence and discrimination can also be linked to stress-related coping behaviors, such as substance use, which can reduce HRQOL. Sexual minority young people in the U.S. report higher levels of alcohol, tobacco, and other substance use compared to their heterosexual peers [55–57], suggesting that links between gender expression, sexual minority stress, substance use, and HRQOL warrant further investigation.

Prior research has also suggested several gender-specific pathways to consider for the HRQOL dimensions on which we observed moderation by gender. Among young women, higher adherence to masculine role norms (which includes socially assigned gender nonconformity) has been associated with higher body mass index (BMI) relative to women who adhere to feminine role norms [58], and high BMI may be linked to poorer HRQOL [59]. Greater gender nonconformity among women could also predict greater participation in stereotypically masculine occupations involving physical labor or in sports-related activities, all of which could increase risk of injury [31, 60, 61], causing problems with pain and mobility. Alternatively, more gender nonconforming boys might engage in less stereotypically masculine and less physically risky activities, which might be protective against injury and subsequent chronic pain or physical limitations; there is limited research on this to date, although a study of preschool age children in France found that lower masculinity scores predicted lower injury risk behaviors among both boys and girls [34]. Yet even for outcomes in which gender was not a significant moderator, gender nonconforming men were at higher risk of poorer HRQOL than their conforming peers, further underscoring the plausibility of the minority stress pathway—which is to say that stigma and discrimination related to gender nonconformity is taking a toll on the HRQOL of both women and men in this study.

Although the most gender conforming women and men had, on average, the highest HRQOL, some key questions remain unanswered. At the same time, important questions remain We recommend that future research on the relationship between gender conformity/nonconformity and health outcomes that influence HRQOL should examine the question of whether, for some health domains, the most gender conforming may have elevated health risks, and those who are more moderately conforming may experience some protective effects.

These findings must be considered in light of several limitations. We measured the key predictor, gender nonconformity, at a single time point; therefore we are not able to detect changes in gender expression over adolescence and young adulthood and the effect such changes may have on health status; however, at least one study has found that childhood and adulthood self-reported gender nonconformity are positively correlated [62]. Although gender nonconformity was assessed in 2010–2011 prior to the measurement of HRQOL in 2013, this does not eliminate the possibility that prior poor health might influence individuals’ understandings of others’ perceptions of their masculinity or femininity. Further, although this study found that the most highly gender conforming were at lowest risk of having poor HRQOL, future research in this area should consider whether there are gender-related health domains for which the moderate group might be protected while those at the most highly conforming end of the spectrum may have elevated risks (e.g., disordered eating behaviors for young women, aggression-related injuries for young men) that could negatively impact HRQOL. Like any survey research, this analysis relies on self-report data, which can lead to measurement error and item non-response. Yet it is notable that prior research has found that self-reported gender nonconformity is positively correlated with observer-reported gender nonconformity [62].

Power limitations were also a concern in this analysis, given relative sparseness of data for men at the most nonconforming end of the original gender expression scale, which may have hindered our ability to obtain effect estimates for rare outcomes and to detect interaction effects. This suggests that gender nonconforming young men of all sexual orientations are an important group for further study, in both similar and more heterogeneous cohorts. In addition, in sensitivity analyses using higher cut-points to define the most gender nonconforming group in young women, we found similar but slightly greater magnitude effect estimates, suggesting that we may be underestimating the association between gender nonconformity and HRQOL, and this underestimation may apply to young men as well as young women. We also note that small numbers precluded analysis of transgender-identified individuals. Finally, these findings are based on a predominantly white and middle-to-high income cohort of the children of U.S. nurses and may not be generalizable to other U.S. populations.

CONCLUSION

This study’s findings contribute to a nascent body of evidence on the role of gender expression in the health and well-being of adolescents and young adults. The fact that the observed health inequities emerge even in a relatively young, healthy sample is striking as inequities in young adulthood have the potential to be exacerbated over the life course. In addition, to the extent that HRQOL is the result of exposure to stigma or violence, our study suggests that the EQ-5D can be used to evaluate cost-effectiveness of policies that aim to reduce victimization. Further research into the potential pathways between gender conformity, nonconformity, and health—in interaction with other vectors of social inequity such as racism, heterosexism, and class inequality—is needed to build a more complete understanding of gender and HRQOL across the life course, with implications for public health and policy efforts to improve adolescent and young adult health.

Acknowledgments

Data analyses and article preparation were supported by the Kate and Murray Seiden and Frank Denny Fund for Children Scholarship received by A.R. Gordon. A.R. Gordon is also supported by F32DA042506 from the National Institute of Drug Abuse. The Growing Up Today Study (R01HD057368 and R01HD066963) and B. M. Charlton (F32HD084000) are supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. S.B. Austin is supported by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (T71-MC00009 and T76-MC00001) and C.A. Okechukwu is supported by T76-MC00001. The funders had no role in the study other than the funding. The authors would like to thank the members of the Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity & Expression (SOGIE) Working Group and the GUTS team of investigators for their contributions to this paper. The authors would also like to express their gratitude to the thousands of young people across the country participating in the Growing Up Today Study.

Footnotes

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

The Brigham & Women’s Hospital Institutional Review Board approved this study.

References

- 1.Grossman AH, D’Augelli AR. Transgender youth: invisible and vulnerable. Journal of homosexuality. 2006;51(1):111–128. doi: 10.1300/J082v51n01_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Palmer NA, Boesen MJ. The 2013 National School Climate Survey: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Youth in Our Nation’s Schools. New York: GLSEN; 2014. Retrieved from http://www.glsen.org/article/2013-national-school-climate-survey. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant JM, Mottet LA, Tanis J, Harrison J, Herman J, Keisling M. Injustice at Every Turn: A report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Washington, D.C: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force; National Gay and Lesbian Task Force; 2011. Retrieved from http://endtransdiscrimination.org/report.html. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordon AR, Meyer IH. Gender nonconformity as a target of prejudice, discrimination, and violence against LGB individuals. Journal of LGBT Health Research. 2007;3(3):55–71. doi: 10.1080/15574090802093562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(5):674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer IH, Schwartz S, Frost DM. Social patterning of stress and coping: does disadvantaged social statuses confer more stress and fewer coping resources? Social Science & Medicine (1982) 2008;67(3):368–379. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts AL, Rosario M, Corliss HL, Koenen KC, Austin SB. Childhood gender nonconformity: a risk indicator for childhood abuse and posttraumatic stress in youth. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):410–417. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts AL, Rosario M, Slopen N, Calzo JP, Austin SB. Childhood gender nonconformity, bullying victimization, and depressive symptoms across adolescence and early adulthood: an 11-year longitudinal study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52(2):143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toomey RB, Ryan C, Diaz RM, Card NA, Russell ST. Gender-nonconforming lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: School victimization and young adult psychosocial adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46(6):1580–1589. doi: 10.1037/a0020705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bontempo DE, D’Augelli AR. Effects of at-school victimization and sexual orientation on lesbian, gay, or bisexual youths’ health risk behavior. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2002;30(5):364–374. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00415-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Plöderl M, Fartacek R. Childhood Gender Nonconformity and Harassment as Predictors of Suicidality among Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Heterosexual Austrians. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2007;38(3):400–410. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9244-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borrell LN, Jacobs DR, Jr, Williams DR, Pletcher MJ, Houston TK, Kiefe CI. Self-reported racial discrimination and substance use in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Adults Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2007;166(9):1068–1079. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krieger N. Social Epidemiology. 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2014. Discrimination and Health Inequities; pp. 63–125. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beatty DL, Matthews KA, Bromberger JT, Brown C. Everyday Discrimination Prospectively Predicts Inflammation Across 7-Years in Racially Diverse Midlife Women: Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. The Journal of Social Issues. 2014;70(2):298–314. doi: 10.1111/josi.12061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lepore SJ, Revenson TA, Weinberger SL, Weston P, Frisina PG, Robertson R, … Cross W. Effects of social stressors on cardiovascular reactivity in Black and White women. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;31(2):120–127. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3102_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Case P, Bryn Austin S, Hunter DJ, Manson JE, Malspeis S, Willett WC, Spiegelman D. Sexual orientation, health risk factors, and physical functioning in the Nurses’ Health Study II. Journal of Women’s Health. 2004;13(9):1033–1047. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2004.13.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Institute of Medicine. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, D.C: Institute of Medicine: Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities; 2011. (Consensus Report) Retrieved from http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2011/The-Health-of-Lesbian-Gay-Bisexual-and-Transgender-People.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim HJ, Barkan SE, Muraco A, Hoy-Ellis CP. Health disparities among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults: results from a population-based study. American journal of public health. 2013;103(10):1802–1809. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conron KJ, Mimiaga MJ, Landers SJ. A population-based study of sexual orientation identity and gender differences in adult health. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(10):1953–1960. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.174169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma H, Saint-hilaire M, Thomas CA, Tickle-degnen L. Stigma as a key determinant of health-related quality of life in Parkinson’s disease. Quality of Life Research. 2016;25(12):3037–3045. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1329-z. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1329-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holzemer WL, Human S, Arudo J, Rosa ME, Hamilton MJ, Corless I, … Maryland M. Exploring HIV Stigma and Quality of Life for Persons Living With HIV Infection. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2009;20(3):161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hutton VE, Misajon R, Collins FE. Subjective wellbeing and “felt” stigma when living with HIV. Quality of Life Research. 2013;22(1):65–73. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goffman E. Stigma; notes on the management of spoiled identity. Vol. 1963 Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wylie S, Corliss HL, Boulanger V, Prokop LA, Austin SB. Socially Assigned Gender Nonconformity: A brief measure for use in surveillance and investigation of health disparities. Sex Roles. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s11199-010-9798-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Courtenay WH. Engendering health: A social constructionist examination of men’s health beliefs and behaviors. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2000;1(1):4–15. doi: 10.1037/1524-9220.1.1.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iwamoto DK, Cheng A, Lee CS, Takamatsu S, Gordon D. “Man-ing” up and getting drunk: the role of masculine norms, alcohol intoxication and alcohol-related problems among college men. Addictive behaviors. 2011;36(9):906–911. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pachankis JE, Westmaas JL, Dougherty LR. The influence of sexual orientation and masculinity on young men’s tobacco smoking. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2011;79(2):142–152. doi: 10.1037/a0022917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hammond WP. Taking it like a man: masculine role norms as moderators of the racial discrimination-depressive symptoms association among African American men. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(Suppl 2):S232–241. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Halkitis PN, Moeller RW, Siconolfi DE, Jerome RC, Rogers M, Schillinger J. Methamphetamine and poly-substance use among gym-attending men who have sex with men in New York City. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;35(1):41–48. doi: 10.1007/s12160-007-9005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hammond WP, Matthews D, Mohottige D, Agyemang A. Masculinity, medical mistrust, and preventive health services delays among community-dwelling African-American men. Journal of general internal medicine. 2010;25(12):1300–1308. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1481-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calzo JP, Roberts AL, Corliss HL, Blood EA, Kroshus E, Austin SB. Physical activity disparities in heterosexual and sexual minority youth ages 12–22 years old: roles of childhood gender nonconformity and athletic self-esteem. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. 2014;47(1):17–27. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9570-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roberts AL, Rosario M, Calzo JP, Corliss HL, Frazier L, Austin SB. Masculine Boys, Feminine Girls, and Cancer Risk Behaviors: An 11-Year Longitudinal Study. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davison KK, Schmalz DL, Downs DS. Hop, skip... no! Explaining adolescent girls’ disinclination for physical activity. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;39(3):290–302. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9180-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Granié MA. Gender stereotype conformity and age as determinants of preschoolers’ injury-risk behaviors. Accident; analysis and prevention. 2010;42(2):726–733. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2009.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greytak EA, Gill A, Conron KJ, Matthews PA, Scout, Reisner SL, … Tamar-Mattis A. In: Identifying Transgender and Other Gender Minority Respondents on Population-Based Surveys: Special Considerations for Adolescents, Race/Ethnicity, Socioeconomic Status, and Intersex Status. Herman JL, editor. Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute; 2014. pp. 29–43. Retrieved from http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/geniuss-report-sep-2014.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 36.EuroQol Group. 2014 www.euroqol.orgRetrieved January 22, 2014, from http://www.euroqol.org/about-eq-5d.html.

- 37.Luo N, Johnson JA, Shaw JW, Feeny D, Coons SJ. Self-reported health status of the general adult US population as assessed by the EQ-5D and Health Utilities Index. Medical care. 2005;43(11):1078–1086. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182493.57090.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson JA, Luo N, Shaw JW, Kind P, Coons SJ. Valuations of EQ-5D health states: are the United States and United Kingdom different? Medical care. 2005;43(3):221–228. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200503000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. U.S. Valuation of the EuroQol EQ-5D(TM) Health States (Text) Rockville, MD: 2012. Retrieved from http://www.ahrq.gov/rice/EQ5Dproj.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Hout B, Janssen MF, Feng YS, Kohlmann T, Busschbach J, Golicki D, … Pickard AS. Interim scoring for the EQ-5D-5L: mapping the EQ-5D-5L to EQ-5D-3L value sets. Value in Health: The Journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. 2012;15(5):708–715. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shaw JW, Johnson JA, Coons SJ. US valuation of the EQ-5D health states: development and testing of the D1 valuation model. Medical Care. 2005;43(3):203–220. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200503000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lubetkin EI, Jia H, Franks P, Gold MR. Relationship Among Sociodemographic Factors, Clinical Conditions, and Health-related Quality of Life: Examining the EQ-5D in the U.S. General Population. Quality of Life Research. 2005;14(10):2187–2196. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-8028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Horton NJ, Kleinman KP. Much ado about nothing: A comparison of missing data methods and software to fit incomplete data regression models. The American Statistician. 2007;61(1):79–90. doi: 10.1198/000313007X172556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Collins LM, Schafer JL, Kam CM. A comparison of inclusive and restrictive strategies in modern missing data procedures. Psychological methods. 2001;6(4):330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yuan Y. Multiple imputation using SAS software. Journal of Statistical Software. 2011;45(6):1–25. doi: 10.18637/jss.v045.i01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldsmith KA, Dyer MT, Schofield PM, Buxton MJ, Sharples LD. Relationship between the EQ-5D index and measures of clinical outcomes in selected studies of cardiovascular interventions. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2009;7(1):96. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Friedman MS, Koeske GF, Silvestre AJ, Korr WS, Sites EW. The impact of gender-role nonconforming behavior, bullying, and social support on suicidality among gay male youth. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2006;38(5):621–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Landolt MA, Bartholomew K, Saffrey C, Oram D, Perlman D. Gender Nonconformity, Childhood Rejection, and Adult Attachment: A Study of Gay Men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2004;33(2):117–128. doi: 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000014326.64934.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu RT, Mustanski B. Suicidal ideation and self-harm in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. American journal of preventive medicine. 2012;42(3):221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Remafedi G, Farrow JA, Deisher RW. Risk factors for attempted suicide in gay and bisexual youth. Pediatrics. 1991;87(6):869–875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rieger G, Savin-Williams RC. Gender nonconformity, sexual orientation, and psychological well-being. Archives of sexual behavior. 2012;41(3):611–621. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9738-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hendricks ML, Testa RJ. A Conceptual Framework for Clinical Work With Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Clients: An Adaptation of the Minority Stress Model. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2012;43(5):460. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Keeshin BR, Cronholm PF, Strawn JR. Physiologic changes associated with violence and abuse exposure: an examination of related medical conditions. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2012;13(1):41–56. doi: 10.1177/1524838011426152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Corliss HL, Rosario M, Wypij D, Wylie SA, Frazier AL, Austin SB. Sexual orientation and drug use in a longitudinal cohort study of U.S. adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(5):517–521. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Corliss HL, Rosario M, Wypij D, Fisher LB, Austin SB. Sexual orientation disparities in longitudinal alcohol use patterns among adolescents: findings from the Growing Up Today Study. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2008;162(11):1071–1078. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.11.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, King KM, Miles J, Gold MA, … Morse JQ. Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: a meta-analysis and methodological review. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2008;103(4):546–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Austin SB, Ziyadeh NJ, Calzo JP, Kennedy GA, Roberts AL, Haines J, Scherer EA. Gender expression associated with BMI in a prospective cohort study of U.S. adolescents. Obesity. 2016;24(2):506–15. doi: 10.1002/oby.21338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Okifuji A, Hare BD. The association between chronic pain and obesity. Journal of Pain Research. 2015;8:399–408. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S55598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sonderlund AL, O’Brien K, Kremer P, Rowland B, De Groot F, Staiger P, … Miller PG. The association between sports participation, alcohol use and aggression and violence: a systematic review. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport / Sports Medicine Australia. 2014;17(1):2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sorenson SB. Gender disparities in injury mortality: consistent, persistent, and larger than you’d think. American journal of public health. 2011;101(Suppl 1):S353–358. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rieger G, Linsenmeier JAW, Gygax L, Bailey JM. Sexual orientation and childhood gender nonconformity: Evidence from home videos. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(1):46–58. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]