Abstract

The mycobacteria RNA polymerase (RNAP) is a target for antimicrobials against tuberculosis, motivating structure/function studies. Here we report a 3.2 Å-resolution crystal structure of a Mycobacterium smegmatis (Msm) open promoter complex (RPo), along with structural analysis of the Msm RPo and a previously reported 2.76 Å-resolution crystal structure of an Msm transcription initiation complex with a promoter DNA fragment. We observe the interaction of the Msm RNAP α-subunit C-terminal domain (αCTD) with DNA, and we provide evidence that the αCTD may play a role in Mtb transcription regulation. Our results reveal the structure of an Actinobacteria-unique insert of the RNAP β′ subunit. Finally, our analysis reveals the disposition of the N-terminal segment of Msm σA, which may comprise an intrinsically disordered protein domain unique to mycobacteria. The clade-specific features of the mycobacteria RNAP provide clues to the profound instability of mycobacteria RPo compared with E. coli.

Understanding of the mycobacterial transcription system is useful to the development of therapeutics against tuberculosis infection. Here the authors present the crystal structure of a complete M. smegmatis RNA polymerase open promoter complex that reveals unique features of the mycobacterial polymerase.

The infectious disease tuberculosis (TB), caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), claims almost 2 million lives annually. Efforts to combat TB are impeded by the increase of multi-drug resistant Mtb strains. Rifamycins, an important component of modern TB therapy1, target the Mtb RNA polymerase (RNAP), the enzyme responsible for all transcription in the bacterium. This provides an incentive to determine structures of the mycobacteria RNAP to aid in the development of improved therapeutics.

In bacteria, transcription initiation occurs when the ∼400 kDa RNAP catalytic core enzyme (E, subunit composition α2ββ′ω) associates with the promoter specificity subunit, σA, to create the holoenzyme (EσA), which directs the enzyme to promoter DNA sites through sequence-specific recognition of the −35 and −10 promoter elements by σA domains 4 (σA4) and 2 (σA2), respectively2. Initial EσA/promoter DNA recognition triggers a series of events as the enzyme unwinds 12–14 bp of DNA to form the transcriptionally competent open promoter complex (RPo)3,4. This functional paradigm was developed through studies of the RNAP from Escherichia coli (Eco)3. While structures of Eco RNAP are available5,6,7, most high-resolution structures of bacterial RNAPs in different states of the transcription cycle come from Thermus RNAPs8. Recent mechanistic studies have revealed that mycobacteria RNAP exhibits unexpected differences in basic and regulated functions from those of Eco and Thermus. These include differences in: (1) termination signals and the influence of elongation factors9; (2) the kinetic landscape during initiation4,10,11,12; (3) the dependence on essential general transcription factors such as CarD (absent in Eco) and RbpA (absent in both Eco and thermus)13,14 and (4) the structures and insertion points of lineage-specific inserts in the RNAP large subunits15.

Previously we described a 2.76 Å-resolution crystal structure of M. smegmatis (Msm) EσA with RbpA and bound to an upstream fork (us-fork) promoter DNA fragment (RbpA/EσA/us-fork), focusing on the roles of the essential transcription factors RbpA and CarD in the initiation process4. Here, we present a 3.2 Å-resolution crystal structure of a full Msm RPo containing RbpA/EσA and promoter DNA containing a complete transcription bubble and a 4-mer RNA hybridized to the DNA template strand (t-strand) in the RNAP active site. Analysis of these two structures, focusing on RNAP structural features not addressed in our previous manuscript4, provides several highlights, including: (1) the highest resolution view available of conserved RNAP/DNA interactions in RPo, (2) the interaction of the Msm RNAP α-subunit C-terminal domain (αCTD) with an AT-rich segment of the DNA along with evidence that the αCTD may play a previously unappreciated role in mycobacteria transcription regulation, (3) the structure of lineage-specific insert β′i1, unique to Actinobacteria15 and (4) the disposition and unique features of the N-terminal segment of Msm σA, unique to mycobacteria (termed σAN here).

Results

Overall structure of Msm transcription initiation complexes

Structure determination of the Msm RbpA/EσA with an us-fork promoter fragment (Supplementary Fig. 1) was previously described4. We formed a complete RPo by combining Msm RbpA/EσA with a duplex promoter DNA scaffold (−37 to +13 with respect to the transcription start site at +1) but with a non-complementary transcription bubble generated by altering the sequence of the t-strand DNA from −11 to +2 plus an RNA primer complementary to the t-strand DNA from +1 to −3, yielding a 4 bp RNA/DNA hybrid (Fig. 1a). The Msm RbpA/RPo crystallized in the same space group (P21) with very similar unit cell parameters as the us-fork complex and diffraction data were collected to a resolution of 3.2 Å. The RPo structure was solved by molecular replacement and refined (Fig. 1b; Supplementary Table 1). There were no significant conformational differences between the two structures, which superimposed with a root-mean-square deviation (r.m.s.d.) of 0.59 Å over 2,933 α-carbons.

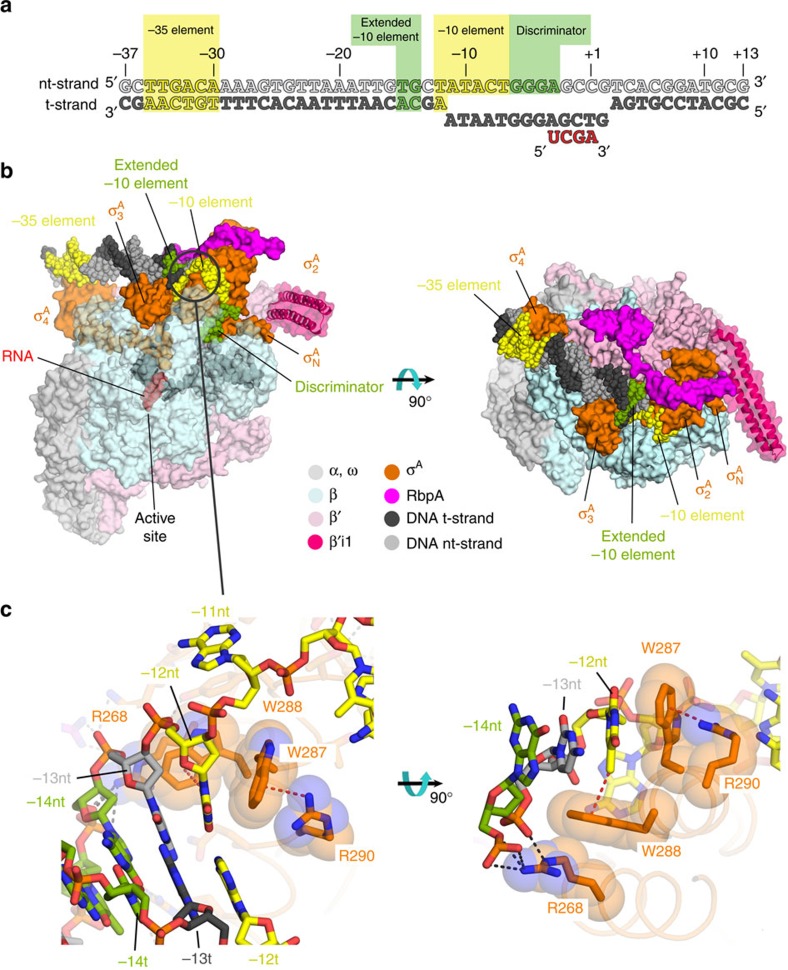

Figure 1. Structure of the Msm RbpA/RPo.

(a) Synthetic oligonucleotides used for the Msm RbpA/RPo crystallization. The numbers above denote the DNA position with respect to the RNA transcript 3′-end (+1). The DNA sequence is derived from the full con promoter63. The nt-strand DNA (top strand) is coloured light grey; the t-strand DNA (bottom strand), dark grey; RNA, red. The −35 and −10 elements are shaded yellow. The extended −10 (ref. 38) and discriminator64,65 elements are coloured green. (b) Overall structure of the Msm RbpA/RPo. The color-coding of most of the structural features is denoted in the legend. Protein components (core RNAP, σA, RbpA) are shown as molecular surfaces. The surface of the RNAP β subunit is transparent, revealing the nucleic acids and σA elements located in the RNAP active centre cleft. The surface of the lineage-specific insert β′i1 is transparent, revealing the α-carbon backbone ribbon underneath. The nucleic acids are shown as CPK atoms, coloured as in Fig. 1a. The circled region in the left view is magnified in Fig. 1c. (c) Magnified views showing the upstream ds/ss junction of the transcription bubble in RPo (obscuring elements of the structure have been removed). Side chains of the absolutely conserved σA W-dyad (W288/W287) and conserved σA Arg residues that buttress the W-dyad (R268, R290) are shown in orange along with transparent CPK spheres (Supplementary Fig. 2D). Polar interactions (hydrogen bonds, salt bridges) are shown as grey dashed lines. The cation-π interaction19 (R290-W287) and the methyl-π interaction17,18 [T−12(nt)-W288] are shown as red dashed lines.

Protein–DNA interactions

Interactions of RNAP with the full transcription bubble and the upstream double-strand/single-strand (ds/ss) DNA junction at the upstream edge of the −10 element where transcription bubble formation initiates in RPo have only been visualized at 4 Å resolution16. The structures reported here at much higher resolution confirm and extend these previous observations (Figs 1c and 2a, Supplementary Figs 2–4).

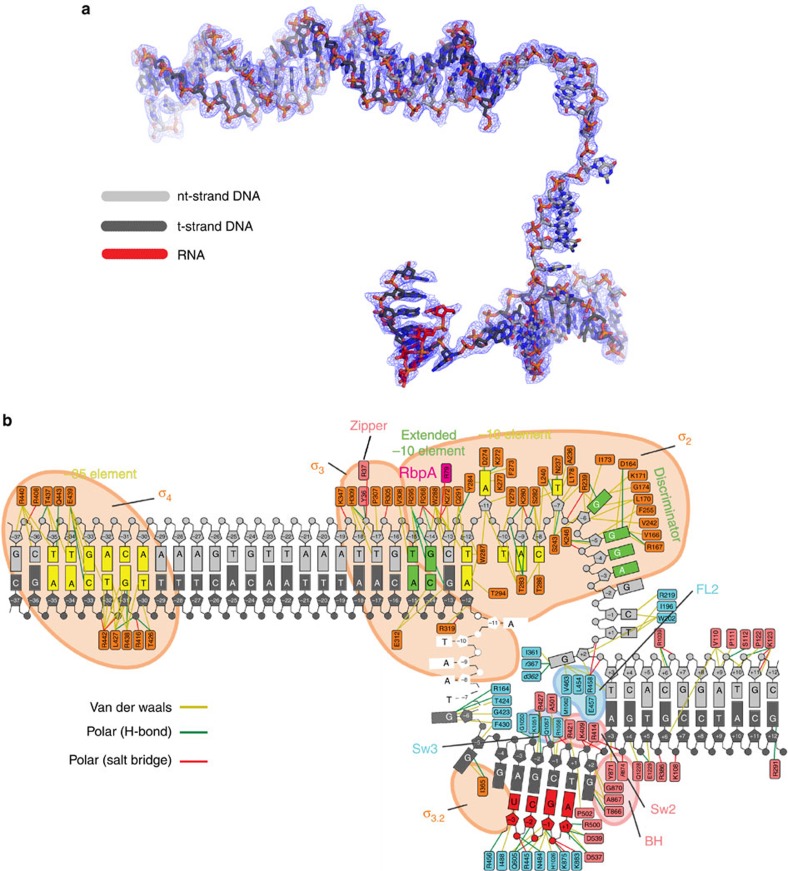

Figure 2. Msm RPo electron density and protein–DNA interactions.

(a) Electron density and model for RPo nucleic acids. Blue mesh, 3.2 Å resolution 2Fo−Fc map for nucleic acids (contoured at 1.0σ). (b) The nucleic acids shown are from the RPo structure (Fig. 1a). The protein–DNA interactions for the −10 element and upstream were derived from the 2.76 Å-resolution Msm RbpA/EσA/us-fork complex (PDB ID 5VI8)4, but only a small handful of these interactions differed in the 3.2 Å-resolution RPo structure. The protein/nucleic acid interactions for nucleic acids downstream of the −10 element were derived from the 3.2 Å-resolution RPo structure (Figs 1b and 2a). The t-strand DNA from −7 to −11 was disordered and not modelled. Protein/DNA interactions were defined as follows: van der Waals (≤ 4.5 Å), yellow lines; H-bonds (≤ 3.5 Å); salt bridges (≤ 4.5 Å), red lines.

As seen previously16, the invariant W-dyad of σA2 (Msm σA W287/W288; Supplementary Fig. 2D) maintains the ds/ss (−12/−11) junction at the upstream edge of the transcription bubble (Fig. 1c). The W-dyad forms a ‘chair’-like structure, with W287 serving as the back of the chair, and W288 as the seat, buttressing the T−12(nt) from the major groove side. The methyl group of the T−12(nt) base approaches the face of the W288 side chain at a nearly orthogonal angle, forming a favourable methyl-π interaction17,18 (Fig. 1c).

Arg residues of σA2 support the role of the W-dyad in stabilizing the upstream ds/ss junction by buttressing the Trp side chains from the face opposite the T−12(nt) base (Fig. 1c). The guanidino group of R290 (absolutely conserved among Group 1 σ’s; Supplementary Fig. 2D) forms a cation-π interaction19 with the downstream face of W287, sandwiching the W287 indole side chain between the exposed T−12(nt) base with an inter-ring angle of ∼27° (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 4). R268 reaches across from the σA2 region 2.2 α-helix to make salt bridges with the −13 nt and −14 nt phosphates, positioning the R268 hydrophobic alkyl chain to interact with the underside of the W288 side chain (opposite the methyl-π interaction with the T-12(nt) base;Fig. 1c). The position corresponding to Msm σA R268 is conserved as either K or R (Supplementary Fig. 2D). In the 4 Å-resolution Taq RPo structure (PDB ID 4XLN (ref. 16)), the electron density for both of the corresponding Arg side chains (Taq σA R237/R259) was weak and interactions with the W-dyad were not observed. The ionic strength of the Taq RPo crystallization solution was ∼4.9 M [1.6 M (NH4)2SO4], while the ionic strength of the Msm RbpA/EσA transcription initiation complexes (TICs) was ∼0.6 M (polyethylene glycol+0.2 M Li2SO4). The electrostatic interactions formed by these two Arg residues (corresponding to Msm σA R268/R290; Taq σA R237/R259) were likely weakened in the high ionic strength of the Taq RPo crystallization solution.

Additional RNAP/promoter DNA interactions were described at 4 Å resolution but are now observed much more clearly (Supplementary Figs 2C, 3,4). A summary of the RNAP/promoter DNA interactions is shown schematically in Fig. 2b.

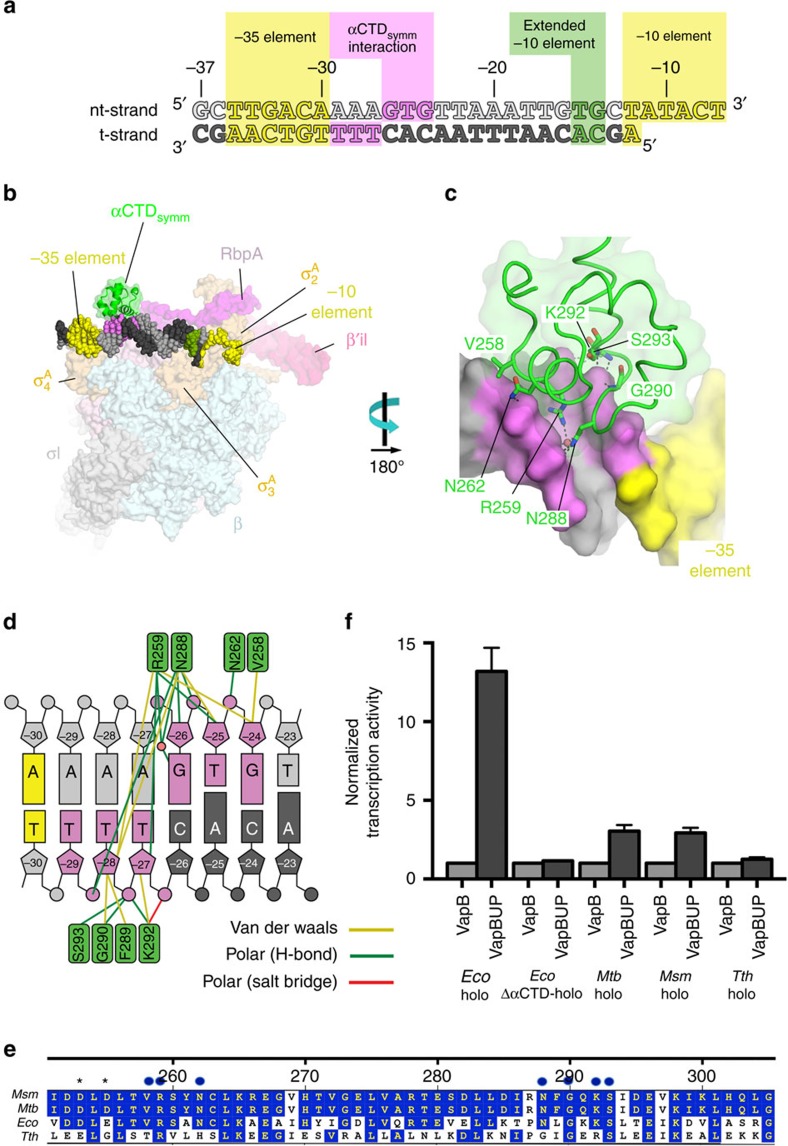

A mycobacteria αCTD–DNA interaction

During refinement of the Msm RbpA/EσA/us-fork complex4, unaccounted difference density appeared that corresponded to an αCTD bound to an A/T-rich region of the promoter DNA from −29 to −24 (A−29AAGTG−24; Fig. 3). The αCTD structure was built and refined previously but was not addressed in the earlier manuscript4. Very weak and broken electron density for the αCTD was also observed in the Msm RPo structure, indicating very low occupancy. The α-N-terminal domain (essential for α dimerization and RNAP assembly)20,21 is flexibly linked to the αCTD by a ∼25 residue unstructured linker. In Eco, the αCTD binds to A/T-rich regions upstream of the promoter −35 element (UP elements), activating transcription at many promoters22. The Eco αCTD also plays a major role in interacting with transcription factors23,24. The role, or even existence, of UP elements in mycobacteria transcription regulation has not, to our knowledge, been identified.

Figure 3. Mycobacteria αCTD/DNA interactions.

(a) Sequence of the us-fork promoter fragment used in the 2.76 Å-resolution Msm TIC structure4. The numbers above denote the DNA position with respect to the transcription start site (+1). The DNA sequence is derived from the full con promoter63. The nt-strand DNA (top strand) is coloured light grey; the t-strand DNA (bottom strand), dark grey. The −35 and −10 elements are shaded yellow. The extended −10 (ref. 38) is coloured green. The DNA nts interacting with a symmetry-related αCTD (αCTDsymm) are coloured violet. (b) Overall view of the Msm RbpA/EσA/us-fork complex. The color-coding is the same as Fig. 1b. The RNAP is shown as a molecular surface. The DNA is shown in CPK format, color-coded as Fig. 2a. Also shown is αCTDsymm (green backbone ribbon with transparent green molecular surface). (c) Close-up of αCTDsymm/DNA interactions (viewed from the back side of Fig. 2b). The αCTDsymm is shown as a green backbone worm with conserved DNA-interacting side chains shown (polar interactions are shown as grey dashed lines). A well-ordered water molecule mediating αCTDsymm interactions is shown as a pink sphere. The DNA is shown as a molecular surface. (d) Schematic illustrating αCTDsymm/DNA interactions. (e) Sequence alignment of Msm, Mtb, Eco and Tth αCTDs. The numbering at the top denotes the Msm and Mtb numbering. Residues conserved in at least three of the seqences are shaded blue. Residues that interact with the DNA are denoted with blue dots above the sequences. The DNA-interacting residues are all conserved between Msm, Mtb, and Eco, but not with Tth. Negatively charged residues shown to be important for Eco αCTD/σ704 interactions that play a role in stimulating transcription are are denoted with asterisks (*) above. We infer that these residues also play a role in stimulatory Msm and Mtb αCTD/σA4 interactions as well since they are conserved as negatively charged residues in Msm and Mtb. (f) Histogram showing abortive transcription activity of various holoenzymes (shown below) on the Mtb VapB promoter (normalized to 1) and VapBUP (engineered to contain a proximal UP-element sequence (Supplementary Fig. 6B,C). The values are the average of triplicate experiments. The error bars denote the s.e.m.

The location of the Msm αCTD and its relationship to neighbouring molecules in the crystal packing environment indicates that the αCTD belongs to a symmetry-related RNAP (Supplementary Fig. 5A) and is bound to the DNA adventitiously (αCTDsymm) in a non-physiologically relevant position of the promoter between the −10 and −35 elements (Fig. 3a,b) rather than the physiologically relevant position upstream of the −35 element22. The structure of the Msm αCTD is essentially identical to the Eco αCTD (r.m.s.d. of 0.586 Å over 40 Cα’s)25. All of the αCTD DNA-interacting residues are conserved between Msm, Mtb and Eco, and the αCTD/DNA interactions are essentially identical, including an ordered water molecule that mediates interactions between Msm/Eco R259/R265, N288/N294 and the DNA (Fig. 3c–e). Finally, Eco αCTD D259 and E261 have been shown to facilitate UP-element function by interacting with σ70 R603 (ref. 26); all of these residues are conserved in the Msm and Mtb proteins (αCTD D253/D255, Fig. 2e, and σA R457) but do not interact due to the non-physiological position of the αCTD.

UP-element-like sequences are enriched in Mtb promoters

The striking similarities between Eco and Msm αCTD structure and DNA interactions (Fig. 3) raises the possibility that αCTD/UP-element interactions play a role in mycobacteria transcription regulation. To further explore this idea, we used RNA-seq with transcriptional start site (TSS) mapping data to compare the occurrence of promoter motifs upstream of TSSs in the Eco (ref. 27) and Mtb (ref. 28) genomes. We searched DNA sequences29 within 50 bp upstream of the identified TSSs for motifs (denoted in Table 1), taking into account the variability in spacing between the −10 element and the TSS30 and between the −10 and −35 elements31. We note that the search parameters (Table 1) are fairly restrictive and are expected to miss divergent promoters, so our analysis yields lower bounds on the estimates of promoter motif occurrence. Nevertheless, these searches provide a good basis for direct comparison of global promoter architecture in the two genomes. We note that the Eco and Mtb genomes have very different GC contents [Eco, 50.8% GC32; Mtb, 65.6% (ref. 33)] so promoter elements such as the A/T-rich UP-element34 may have diverged between Eco and Mtb.

The −10 element31,35,36: Most of the conservation in the −10 element is captured by the ANNNT motif31,37, and the spacing to the TSS varies between 6 and 9 nt (ref. 30). Thus, we searched upstream of the 3,746 Eco and the 1,775 Mtb TSSs for an ANNNT (6–9 N) motif and identified 2,953 (Eco) and 1,702 (Mtb) −10 elements (Table 1). The −10 element is the most highly conserved31 and the only essential element for Group 1 σ factor promoters, so the searches for the remaining promoter elements were done in the context of the −10 element hits for each genome.

Extended −10 element38: The Eco and Mtb genomes utilize the extended −10 motif (TGNNANNNT) to very similar extents. In Eco, 18% of the 2,953 −10 element hits used an extended −10 element, while in Mtb, 15% of the 1,702 −10 element hits used an extended −10 element (Table 1). In both genomes, the extended −10 motif was found at nearly three times the expected frequency for chance occurrence of the motif.

−35 element31: Previous analyses of the Eco and Mtb TSS data did not take into account the known variability in spacing between the −10 and −35 elements. The optimal −10/−35 spacing is 17 nt, and spacings of 16, 17 and 18 nt account for more than 75% promoters analysed by Shultzaberger et al. 31. We searched for a −35 element motif comprising T(G/T)(G/T)(A/C/T)NN (which accounts for most of the sequence conservation of the motif)31 spaced 16, 17 or 18 nt upstream of the −10 element (Table 1). We found that Eco makes more extensive use of the paridigmatic −10/−35 promoter architecture, with 43% of the −10 element hits harbouring the −35 element compared to 19% in Mtb (Table 1).

UP element34: UP-element sequences are highly divergent, essentially comprising A/T-rich sequences upstream of the −35 element22. However, Estrem et al 34. used a SELEX approach to identify UP-element consensus sequences. We probed for the possible occurrence of UP element regulatory sequences in Mtb compared to Eco by searching for the most prominent feature of the proximal UP element, an ‘AAA’ motif 26, 27 or 28 nt upstream of the −10 element34. According to this stringent criterium, 15% of the Eco −10 element promoters harboured an UP element, while 3.2% of the Mtb promoters did (Table 1). While the occurrence of the UP element motif in Mtb appears to be small, the high GC content of the Mtb genome makes the ‘AAA’ motif highly unlikely to occur by chance; the 15% UP-element occurrence in Eco is 3.3-fold enriched over random, while the 3.2% UP-element occurrence in Mtb is 2.1-fold enriched over random (Table 1).

Table 1. Promoter motifs in Eco and Mtb.

|

Eco

(3,746) |

Mtb

(1,775) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Element | Sequence motif | Hits | Expected random hits | Enrichment over random | Hits | Expected random hits | Enrichment over random |

| −10 element | ANNNT(6−9 N) | 2,953 | 680 | 4.3 | 1,702 | 53 | 32 |

| Ext. −10 element | TGNNANNNT | 530 (18%) | 185 (6.3%) | 2.9 | 256 (15%) | 96 (5.6%) | 2.7 |

| −35 element | TKKHNN(16 N)NANNNT | 346 (12%) | 137 (4.6%) | 2.5 | 69 (4.1%) | 47 (2.8%) | 1.5 |

| TKKHNN (17 N)NANNNT | 583 (20%) | 137 (4.6%) | 4.3 | 146 (8.6%) | 47 (2.8%) | 3.1 | |

| TKKHNN (18 N)NANNNT | 330 (11%) | 137 (4.6%) | 2.4 | 116 (6.8%) | 47 (2.8%) | 2.5 | |

| All −35 elements | 1,259 (43%) | 411 (14%) | 3.1 | 331 (19%) | 141 (8.3%) | 2.3 | |

| −35 and ext. −10 elements | 172 (5.8%) | 26 (0.88%) | 6.6 | 44 (2.6%) | 8 (0.47%) | 5.5 | |

| UP-element | AAANNNNNNNNNN(16 N)NANNNT | 145 (4.9%) | 44 (1.5%) | 3.3 | 21 (1.2%) | 8.7 (0.51%) | 2.4 |

| AAANNNNNNNNNN(17 N)NANNNT | 150 (5.1%) | 44 (1.5%) | 3.4 | 17 (1.0%) | 8.7 (0.51%) | 2.0 | |

| AAANNNNNNNNNN(18 N)NANNNT | 144 (4.9%) | 44 (1.5%) | 3.3 | 16 (0.94%) | 8.7 (0.51) | 1.8 | |

| All UP elements | 439 (15%) | 132 (4.5%) | 3.3 | 54 (3.2%) | 26 (1.5%) | 2.1 | |

N: any nt. K: G/T. H: not G.

An UP-element-like sequence enhances Mtb transcription

Our promoter motif searches indicate that UP element sequences are enriched upstream of Mtb promoters. To test if a consensus proximal UP element can play a role in activating mycobacteria transcription, we engineered a native Mtb promoter, the vapB10p antitoxin promoter (VapB)28 to contain a proximal UP-element sequence (VapBUP; Supplementary Fig. 5B). We compared transcription activity of VapB with VapBUP using Eco RNAP (positive control), Eco ΔαCTD-RNAP (negative control), and Mtb and Msm RNAPs. Transcription by Eco Eσ70 was stimulated more than tenfold by the presence of the UP element, while Eco ΔαCTD-Eσ70 was not (Fig. 3f), consistent with the role of the αCTDs in UP element activation22. Both Mtb and Msm holoenzymes were stimulated roughly threefold by the presence of the UP element (Fig. 3f), suggesting that αCTD/UP element interactions play a role in regulating mycobacteria transcription. Finally, we tested Tth RNAP on the same pair of promoters. Some of the DNA-binding residues of the αCTD are not conserved in Tth αCTD (Fig. 2e), and the presence of the UP-element did not stimulate Tth RNAP transcription (Fig. 3f).

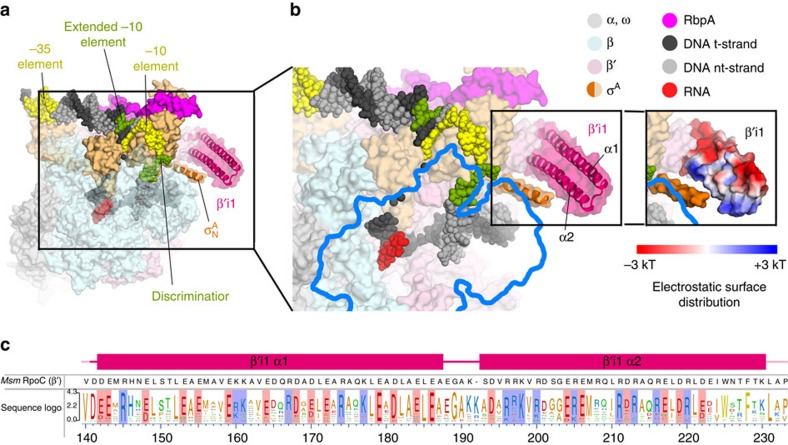

An Actinobacteria-specific insertion in the β′ subunit

The RNAP β and β′ subunits comprise linearly arranged segments of sequence conserved between all five kingdoms of life15. These conserved segments are separated by spacer regions that are not conserved between phylogenetically distinct groups of bacteria and large, lineage-specific domain insertions can occur within the spacer regions15,39. The Actinobacteria RNAPs, which includes Msm and Mtb RNAPs, contain one lineage-specific insertion, a ∼90 residue insertion at about position 140 of the β′ subunit (β′i1)15. The insertion point of the Actinobacteria β′i1 is identical to the insertion point of an unrelated lineage-specific insertion, β′i2 of deinococcus-thermus15 (Supplementary Fig. 6). The deinococcus-thermus β′i2 comprises five sandwich-barrel hybrid motifs39 with complex topological connections and plays a role in σA binding40 (Supplementary Fig. 6A).

The Msm TIC structures show that β′i1 spans roughly residues 140–230 and folds into two long anti-parallel α-helices (β′i1-α1, residues 141–186; β′i1-α2, residues 191–228; Figs 1b and 4a,b). The two helices emerge from the tip of the RNAP clamp module and extend across the entrance to the RNAP active centre cleft (Figs 1b and 4a,b). An analysis of the electrostatic surface charge distribution revealed an asymmetry, with a positively charged surface facing the RNAP active site cleft and a negatively charged surface facing outwards (Fig. 4b). A Blast search against Msm β′ residues 130–240 identified 720 homologues, all from Actinobacteria. Sequence alignments revealed a pattern of conserved charged residues: the first β′i1 α-helix (β′i1-α1, distal to the entrance to the RNAP active site cleft; Fig. 4b,c) contains a net charge of −8, while the β′i1-α2 helix (facing the entrance to the RNAP active site cleft) contains a net charge of +2 (Fig. 4c). Thus, the asymmetric charge distribution is a conserved structural feature of the Actinobacteria β′i1, suggesting a functional role.

Figure 4. The Actinobacteria β′i1.

(a) Overall view of the Msm RbpA/RPo. The color-coding of most of the structural features is denoted in the legend (Fig. 3b). Protein components (core RNAP, σA, RbpA) are shown as molecular surfaces. The surface of the RNAP β subunit is transparent, revealing the nucleic acids and σA elements located in the RNAP active centre cleft. The surfaces of σAN and the lineage-specific insert β′i1 are transparent, revealing the α-carbon backbone ribbons underneath. The nucleic acids are shown as CPK atoms. The boxed region is magnified in Fig. 3b. (b) Magnified view of the boxed region from Fig. 3a. Obscuring elements of the RNAP β subunit have been removed (outlined in blue), revealing the nucleic acids in the RNAP active site cleft. The boxed region shows β′i1, with the two α-helices (α1, α2) labelled. The boxed region on the right shows the same view of β′i1 but with the molecular surface coloured according to the electrostatic surface potential (red, −3 kT; blue, +3 kT)66, illustrating the asymmetric charge distribution. (c) The secondary structure of the Msm β′i1 (Msm β′ residues 141–230, Msm numbering shown at the bottom) is schematically illustrated (α-helices are shown as rectangles), with the Msm β′ sequence shown below. The sequence logo67 shown below was derived from a sequence alignment of 720 Msm β′i1 homologues (all Actinobacteria). Conserved negatively charged (D/E) and positively charged (K/R) positions on the α-helices are shaded red or blue, respectively. The α1 harbours 14 positions of conserved negative charge and 6 positions of conserved positive charge (net charge −8), while α2 harbours 7 positions of conserved negative charge and 9 positions of conserved positive charge (net charge +2).

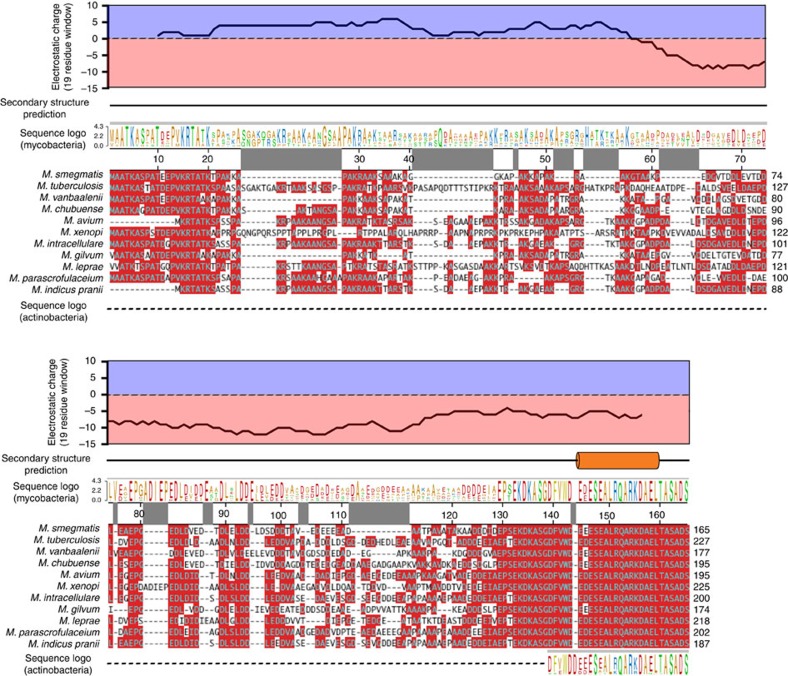

Group 1 σ N-terminal extension

Group 1 σ’s comprise three conserved structured domains (σ2,σ3 and σ4)41 and one divergent N-terminal extension (σAN). Group 1 σAN’s vary greatly in length (residues N-terminal of conserved region 1.2: Mtb σAN, 225; Msm σAN, 163; Eco σ70N, 95) and are not conserved across all clades (see below).

The Eco Group 1 σ, σ70, is autoregulated by σ701.1, which serves to prevent σ70 interactions with promoter DNA in the absence of RNAP42,43,44 and also plays a role in the formation of RPo45,46. Based on solution FRET and structural studies, Eco σ701.1 is located within the RNAP active-site channel in Eσ70, but in RPo, σ701.1 is displaced outside the channel by the entering promoter DNA6,47. Eco σ701.1 comprises a compact three-helical domain linked to the rest of σ70 by a 37-residue linker, facilitating the large movements of σ701.1 during RPo formation6,44. The sequence of Eco σ701.1 is conserved among many bacterial Group 1 σ’s (Supplementary Fig. 7A,B) but not universally so: the sequence bears no apparent relationship with Group 1 σN sequences from several clades, including ε-proteobacteria, deinococcus-thermus (Supplementary Fig. 7C), Mollicutes, Actinobacteria (Fig. 5), Cyanobacteria, Bacteroidetes and Chlorobi (Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 5. Sequence characteristics of the σAN> of mycobacteria and Actinobacteria.

The Msm σAN (163 residues N-terminal of conserved region 1.2 (ref. 68)) is aligned with representative mycobacteria σAN sequences (the number scale on top of the alignment shows the Msm σA numbering). Residues conserved in more than half of the sequences are shaded red. The sequence logo67 shown above was derived from an alignment containing 45 mycobacteria σAN sequences. The predicted secondary structure48,49 for the Msm σAN is shown schematically above the logo. One α-helix is predicted (Msm σAN residues 144–159, orange cylinder), with the rest of the sequence lacking any secondary structure. The net electrostatic charge of the derived consensus sequence, calculated in a 19-residue window, is plotted at the top (net positive charge is shaded blue, negative charge shaded red). A sequence logo derived from the Msm σAN with 199 Actinobacteria σAN sequences (excluding other mycobacteria sequences) is shown below. The region corresponding to Msm σAN residues 139–165, which includes the predicted α-helix, was conserved with all Actinobacteria σAN sequences, while Msm σAN residues 1–138 (the region predicted to lack secondary structure) showed no sequence relationship with other Actinobacteria σAN sequences (except for other mycobacteria σAN sequences) and could not be aligned.

The Msm TIC structures contain full-length σA, and clear electron density for an α-helix extending from the N-terminus of σA1.2 was observed (Fig. 6a; Supplementary Fig. 8). We have not been able to unambiguously assign the sequence register of the σA N-terminal helix. Msm σA harbours 163 residues N-terminal to σA1.2 (σAN). Secondary structure prediction algorithms predict a total lack of secondary structure for residues 1–143 (refs 48, 49), and one α-helix is predicted (∼residues 145–160) as observed in our structure (Figs 5 and 6a). Strikingly, Blast searches identified sequence homologues for Msm σAN only among Actinobacteria, and for most Actinobacteria, the only conserved sequence segment corresponded to Msm σA residues 139–163, corresponding to the α-helix observed in the structure (Figs 5 and 6a). The mycobacteria σAN displays a striking separation of charge, where roughly the first half of the sequence is biased towards positive charged residues, while the C-terminal half is biased towards negatively charged residues (Fig. 5).

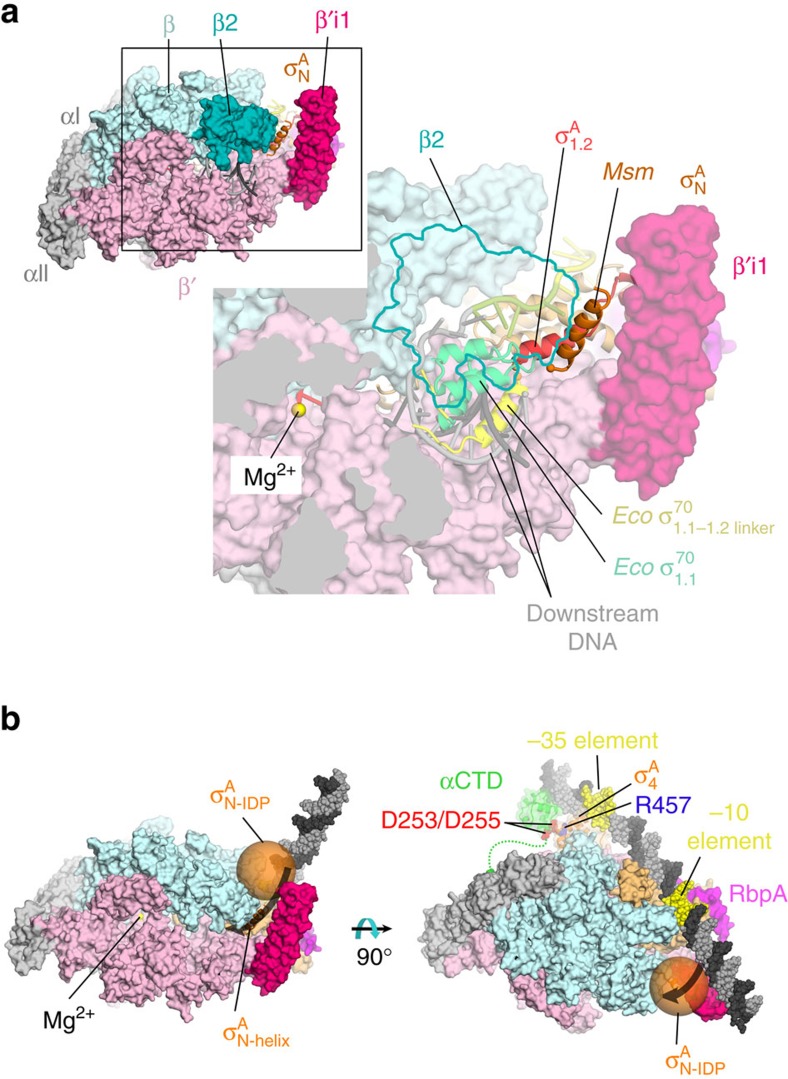

Figure 6. Structural and functional context of the Msm σAN.

(a) (upper left) Overall view of the Msm RbpA/RPo. The color-coding is the same as Fig. 1b except the β2 domain is coloured slate blue. The RNAP is shown as a molecular surface except σA is shown as a backbone ribbon. The nucleic acids are shown in cartoon format. The boxed region is magnified on the lower right. (lower right) Magnified view of the boxed region from the upper right. The β2 domain (outlined in blue) as well as other obscuring regions of the structure have been removed, revealing the RNAP active site cleft and the nucleic acids therein. The σA, shown as a backbone ribbon, is coloured light orange, except the σA1.2 N-terminal helix is coloured orange-red, and the σAN-α-helix is coloured orange. Shown in the downstream duplex DNA-binding channel is the superimposed position of Eco σ701.1 (light green) and the σ701.1–1.2 linker (yellow) from PDB ID 4LK1 (ref. 6). (b) Model of an Msm closed promoter complex (RPc or RP1)4 summarizing the role of the αCTD (green), β′i1 (hot pink), and σAN (orange) in RPo formation. The αCTD was modelled bound upstream of the −35 element, placing conserved negatively charged αCTD residues D253/D255 (Fig. 2e; shown as red CPK atoms) near conserved σA4 R457 (blue CPK atoms), inferring interactions analogous to Eco CTD D259/E261 with σ704 R603 (ref. 26). The σAN-helix is shown as an orange backbone ribbon as observed in the crystal structures (Fig. 5a). The rest of the σAN (approximately residues 1–143) is predicted to comprise an intrinsically disordered region (IDR) and is modelled as a (transparent orange) sphere with the expected radius (30 Å) of a Flory random coil for an IDR with κ (measurement of the extent of charge separation) of 0.42 (ref. 50). The sphere was placed to connect with the N-terminus of the σAN-helix and simultaneously minimize steric clashes. The combined placement of β′i1 and the σAN-IDR blocks the path the DNA must traverse to enter the active site cleft (indicated by thick black arrows).

The orientation of the Msm σAN-helix positioned between the RNAP β2 domain and β′i1, places the rest of the Msm σAN outside of the RNAP active site cleft near the β2 domain (Fig. 6). The placement of the Msm σA N-terminal helix is suggestive that it defines the path of Eco σ701.1 after being displaced from the RNAP active site cleft by incoming promoter DNA6,47. However, it is not clear that movements of mycobacteria σAN during transcription initiation will parallel those of Eco σ701.1 for the following reasons:

Msm σA N bears no sequence nor structural relationship with σ70 N of Eco σ70 (Fig. 5, Supplementary Fig. 7; Supplementary Table 2) and therefore cannot be assumed to bear a functional relationship.

Msm σA[1–143] is predicted to behave like an intrinsically disordered region and, as such, is predicted to have a molecular volume much too large to fit in the RNAP active site cleft50.

In the Msm RbpA/TIC structures, σA N is located outside of the RNAP active site cleft whether or not nucleic acids are present in the active site cleft.

This analysis suggests that unlike Eco σ701.1, Msm σAN may never reside in the RNAP active site cleft. Like Eco σ701.1, however, the placement of Msm σAN between the RNAP β2 domain and β′i1 suggests that Msm σAN plays a role in regulating RPo formation by blocking or restricting the entrance of the DNA template into the active site cleft (Fig. 6b)45,46.

Discussion

Here we present in-depth analyses leading to a comprehensive summary of the structural and functional features of mycobacteria RNAP that are similar to and distinct from Eco. The high resolution views of Msm EσA/promoter DNA interactions detailed here (Fig. 1, Supplementary Figs 2–4) are conserved with those seen in Thermus but with new interactions observed due to the increased resolution from previous Thermus16,37,41,51 and Eco (ref. 52) structures. Our results point to a conserved role for αCTD/UP element DNA interactions in regulating transcription initiation between Eco (ref. 22) and mycobacteria (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 5), a role not shared with Thermus (Fig. 3e,f). Although the insertion point of a lineage-specific insert is identical in the β′ subunit of Thermus and Actinobacteria RNAP (Supplementary Fig. 6), the structures and likely functional roles of the inserts in their respective organisms are unrelated (and the insert is absent in Eco RNAP). Finally, the Group 1 σ factors are among the most highly conserved proteins across all of the bacterial kingdom53. Nevertheless, a defining feature of Group 1 σ’s, σN that harbours Eco σ701.1, bears no apparent structural relationship with the σA N-terminal extensions for either Thermus or Actinobactera (Figs 5 and 6a, Supplementary Fig. 7, Supplementary Table 2). We postulate that the Actinobacteria σAN plays a similar functional role as Eco σ701.1 (licensing access of nucleic acids to the active site channel), but does so in a mechanistically unique way. This work illustrates that structural and functional paradigms developed from the study of the Eco transcription system are not universally applicable among bacteria, and highlights the importance of studying phlyogenetically distinct bacteria to gain comprehensive insight into transcription and its regulation.

Paradigms of transcription have evolved from years of studies using Eco as the model organism. Investigations of transcription mechanisms in other bacteria continue to reveal significant differences with mechanisms in Eco. For example, although the overall mechanism of RPo formation appears to be conserved4, mycobacteria have unique activators that act at the ds/ss (−12/−11) junction instead of at canonical sites upstream of the −35 element4. Why? We propose that this positioning is critical to overcome the block created by the combination of the Msm σAN and β′i1 (Fig. 6b): CarD and RbpA stabilize the bend that places DNA into the RNAP active site cleft4. Lacking this reinforcement, mycobacteria RPo readily dissociates, presumably because DNA loses the competition for active site cleft access. In contrast, no lineage-specific insertions in Eco directly block the active site15,54. Instead two insertions absent in Actinobacteria may form a stabilizing clamp on the downstream duplex DNA, creating a highly stable RPo at many promoters3.

During the review of this manusript, a report describing a number of crystal structures (ranging between 4.3 and 3.8 Å resoultion) of Mtb EσA bound to a downstream-fork (ds-fork) promoter fragment was published55. The Mtb EσA/ds-fork complex is remarkably similar to the Msm RPo: superimposing the Mtb EσA/ds-fork complex (PDB ID 5UHA)55 with the Msm RPo results in a r.m.s.d. of 1.02 Å over 2,783 α-carbon positions. The crystal packing environments of the Mtb (space group P212121) and Msm (space group P21) structures are very similar.

The Mtb EσA/ds-fork structures revealed the Actinobacteria-specific β′i1 and the σAN-helix in essentially identical conformations to those we observe in the Msm TIC structures (Figs 4a,b and 6a)4 but Lin et al.55 proposed a different mechanistic role for these structural elements. Lin et al.55 suggest that in the Mtb EσA, the σA N-terminal extension resides in the RNAP active site cleft and is displaced by the entering promoter DNA in a manner analagous to Eco σ701.1 (refs 6, 47). Once ejected from the RNAP active site cleft, the Mtb σAN is proposed to cooperate with β′i1 to trap the promoter DNA in the cleft, thereby stabilizing RPo. In support of this hypothesis, Lin et al.55 report that deleting σAN, β′i1, or both destabilizes complexes of the resulting holoenzymes with the ds-fork DNA.

However, unlike the compact folded domain Eco σ701.1 (ref. 6), mycobacterial σAN’s are predicted to be intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs; Fig. 5). The IDRs of the Msm (143 residues) and Mtb (205 residues) σAN’s (Fig. 5) are predicted to have effective molecular radii of ∼30 and 34 Å, respectively (Fig. 6b)50, too large to fit into the RNAP cleft. So while Eco σ701.1 (∼90 residues, molecular radius of ∼14 Å) starts in the RNAP cleft6, we propose that the mycobacterial σAN initially lies outside the cleft. In our model of EσA, the mycobacterial σAN with β′i1 cooperate to impede promoter DNA entry into the channel (Fig. 6b) but do not exclude the possibility that one or both inserts could stabilize the DNA once established in the RNAP cleft as proposed by Lin et al.55.

The ds-fork promoter template studied by Lin et al.55 is ‘pre-melted’ and lacks DNA upstream of its single-stranded −10 element. The association pathway of this template is unknown but is almost certainly very different than the assocation pathway of a fully duplex promoter. Initial recognition of a fully duplex promoter occurs outside of the RNAP cleft, with subsequent initiation of −10 element melting (also outside of the RNAP cleft), bending of the downstream DNA across the entrance to the cleft, and finally full transcription bubble melting and loading of the DNA into the cleft (Fig. 6b)3,4. Thus, we suggest that the effect of deleting Mtb σAN and/or β′i1 in stabilizing ds-fork binding55 may not reflect the effects of these deletions on fully duplex promoter interactions. In summary, we propose a very different role for the mycobacteria σAN from Lin et al.55, one where σAN is never in the RNAP cleft and cooperates with β′i1 to impede DNA entry into the cleft. Clearly, further studies are required to understand the role of the mycobacterial σAN and β′i1 in both the association and dissociation of fully duplex promoter DNA and how these elements are regulated.

Continued emergence of multi-antibiotic resistant bacteria present the sobering reality that the clinical anti-bacterial arsenal is becoming increasingly depleted56. We suggest studies of phlyogenetically distinct bacteria such as mycobacteria provide the fudamental groundwork needed to develop novel antibiotics to combat TB and other devastating bacterial diseases.

Methods

Protein expression and purification

Msm RbpA/σA. Msm pET-SUMO σA and pET21c-RbpA were co-expressed in Eco BL21 (DE3) by induction with 0.5 mM isopropyl-beta-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 3 h at 30 °C, affinity purified on a Ni2+-column, and cleaved by ULP1 protease overnight4. The cleaved complex was loaded onto a second nickel column, collected from the flow-through and further purified by size exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200, GE Healthcare).

Msm RNAP. Msm RNAP was purified from the Msm mc2155 strain expressing a native chromosomal copy of rpoC with a C-terminal His10-tag4. Msm cells were grown at the Bioexpression and Fermentation Facility at the University of Georgia, lysed, and core RNAP was precipitated by polyethyleneimine (PEI) precipitation (0.35% w/v). Protein was precipitated with ammonium sulfate (35% w/v) and purified on a Ni2+-affinity column. Fractions containing RNAP were loaded on a Biorex (BioRad) column and RNAP was eluted with a salt gradient. A five-fold molar excess of the purified Msm RbpA/σA was added to the core RNAP and the resulting holoenzyme was further purified by size exclusion chromatography. The purified complex was dialyzed into 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 100 mM K-glutamate, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, concentrated by centrifugal filtration to ∼15 mg ml−1, and stored at −80 °C.

Eco RNAP. Eco core RNAP was overexpressed and purified from Eco BL21(DE3) cells co-transformed with pEcrpoABC(-XH)Z (encoding Eco RNAP rpoA, rpoB and rpoC-His10) and pACYCDuet-1_Ec_rpoZ (encoding rpoZ)57. Eco RNAP subunits were co-overexpressed overnight at room temperature for ∼16 h after induction with 0.1 mM IPTG. Cells were lysed, and core RNAP was precipitated with 0.6% PEI. Proteins eluted from the PEI pellet were then purified by Ni2+-affinity chromatography, Bio-Rex 70 chromatography, and finally purified by size exclusion chromatography4,10,14. Eco core RNAP (Δ-αCTD) was purified as described for the full-length protein but using protein expressed from pECrpoA(-X234–241H)BCZ containing a PreScission protease site between the αNTD and αCTD-His10 (ref. 57). The only difference in the purification occurred after the first Ni2+-affinity step where the protein was subjected to PreScission protease cleavage, dialyzed to remove imidazole. The sample was reapplied to a Ni2+-affinity column and the flow-through collected for subsequent steps57.

Eco σ70 was expressed from a pET21a-based expression vector encoding an N-terminal His6-tag followed by a PreScission protease (GE Healthcare) cleavage site. The protein was expressed using standard methods and purified by Ni2+-affinity chromatography, protease cleavage to remove the His6-tag, anion exchange chromatography, and finally size exclusion chromatography.

Mtb RNAP. Mtb core RNAP subunits were co-overexpressed in Eco BL21 (DE3) pRARE2 (Novagen) cells overnight at room temperature for ∼16 h after induction with 0.1 mM IPTG10. Cells were lysed, and core RNAP was precipitated with 0.6% PEI. Proteins eluted from the PEI pellet were then purified by Ni2+-affinity chromatography and subsequently purified by size exclusion chromatography4,10,14.

Mtb σA was expressed from pAC27 (ref. 9) in Eco BL21 (DE3) pRARE2 and purified by Ni2+-affinity chromatography and size exclusion chromatography9.

Crystallization of Msm RbpA/RPo

To generate the full Msm RPo, Msm RbpA/EσA was mixed in a 1:1 molar ratio with duplex promoter DNA scaffold (−37 to +13) and a five-fold molar excess of RNA primer complementary to the t-strand DNA from +1 to −3 (GE Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO, United States; Fig. 1a) as previously described Bae:2015fc}. Crystals were grown by hanging drop vapour diffusion by mixing 1 μl of Msm RbpA/RPo solution (11 mg ml−1 protein) with 1 μl of crystallization solution [0.1 M Bis–Tris, pH 6.0, 0.2 M LiSO4, 16% (w/v) polyethylene glycol 3350, 2.5% (v/v) ethylene glycol] and incubating over a well containing crystallization solution at 22 °C. The crystals were cryo-protected by step-wise transfer (three steps) into 0.1 M Bis–Tris, pH 6.0, 0.2 M LiSO4, 22% (w/v) polyethylene glycol 3350, 20% (v/v) ethylene glycol and flash frozen by plunging into liquid nitrogen.

Data collection and structure determination

X-ray diffraction data were collected at the Argonne National Laboratory Advanced Photon Source (APS) NE-CAT beamline 24-ID-E at a wavelength of 0.97918 Å. Structural biology software was accessed through the SBGrid consortium58. Data were integrated and scaled using HKL2000 (ref. 59).

An initial electron density map was calculated by molecular replacement using Phaser60 from a starting model of the Msm RbpA/EσA/us-fork structure (PDB ID 5TW1)4. The model was first improved using rigid body refinement of 20 individual mobile domains using PHENIX61. The resulting model was improved by iterative cycles of manual building with COOT62 and refinement with PHENIX61. The final refined model had 94% of residues in the favored region of the Ramachandran plot, 0.71% in the region of Ramachandran outliers.

In vitro transcription assays

In vitro abortive initiation transcription assays were performed at 37 °C as described10, or at 50 °C with Tth holo. VapB and VapBUP promoter templates were prepared using PCR amplification on a synthesized template (Integrated DNA Technologies; Supplementary Fig. 6). Assays with VapB and VapBUP promoter templates were performed in assay buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM DTT, 50 μg ml−1 BSA) with 100 mM K-glutamate when using Msm holoenzyme, or with 50 mM K-glutamate with Mtb holoenzyme. Assays with Eco RNAP and Eco ΔαCTD-RNAP were performed in assay buffer with 50 mM KCl.

Abortive initiation assays were initiated on VapB and VapBUP templates with ApU dinucleotide primer (250 μM; Trilink Biotechnologies, San Diego, CA), [α-32P]GTP (1.25 μCi; Perkin Elmer Life Sciences, Waltham, MA), and unlabelled GTP (50 μM; GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Mbo, Msm, Tth RNAPs (50 nM) were added to DNA template (10 nM) and nucleotide mix, and the reaction was incubated for 10 min at 37 °C (Mbo or Msm) or 50 °C (Tth). Eco holoenzyme or Eco ΔαCTD-holoenzyme were used at 5 nM and the DNA template was 1 nM. Transcription products were visualized by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (23%) followed by phosphorimagery and quantitation using Image J.

Promoter searches and annotation

To annotate and compare promoter motifs we performed identical analyses on Eco and Mtb, using previously determined TSS from each organism. The 3,746 TSSs (Table 1) from Eco were previously determined in Eco K-12 MG1655 cells growing in mid-exponential phase27. The 1,779 TSSs (Table 1) from Mtb were previously determined from exponentially growing Mtb H37Rv (ref. 28).

Using defined spacings from the −10 promoter to the TSS30 and the sequence characteristics and variable spacing between the promoter elements defined in Eco31, we searched the deposited RNA-seq sequences within 50 bp upstream of the identified TSSs for motifs as denoted in Table 1. We accounted for the variability in spacing between the −10 element and the TSS30 and between the −10 and −35 elements by performing separate searches31. Searches were performed using Microsoft Excel Filter functions.

Data availability

The original 2.76 Å resolution Msm RbpA/EσA/us-fork coordinates (5TW1)4 have been updated by the addition of some water molecules, including the ordered water facilitating αCTD binding to DNA (Fig. 3c,d) and have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession ID 5VI8. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates and structure factor file for the Msm RbpA/RPo structure have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession ID 5VI5. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Hubin, E. A. et al. Structural insights into the mycobacteria transcription initiation complex from analysis of X-ray crystal structures. Nat. Commun. 8, 16072 doi: 10.1038/ncomms16072 (2017).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Saecker for insightful discussion. This work is based upon research conducted at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team beamlines, which are funded by the NIGMS from the NIH (P41 GM103403). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. The use of the Rockefeller University Structural Biology Resource Center was made pssible by NIH/NCRR 1S10RR027037. This work was supported by NIH grant RO1 GM114450 to E.A.C.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions All authors designed the project, performed the experiments, and analysed the data. S.A.D. and E.A.C. wrote the paper.

References

- Chakraborty S. & Rhee K. Y. Tuberculosis drug development: history and evolution of the mechanism-based paradigm. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 5, a021147 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami K. S., Masuda S., Campbell E. A., Muzzin O. & Darst S. A. Structural basis of transcription initiation: an RNA polymerase holoenzyme-DNA complex. Science 296, 1285–1290 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saecker R. M., Record M. T. Jr & deHaseth P. L. Mechanism of bacterial transcription initiation: RNA polymerase - promoter binding, isomerization to initiation-competent open complexes, and initiation of RNA synthesis. J. Mol. Biol. 412, 754–771 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubin E. A. et al. Structure and function of the mycobacterial transcription initiation complex with the essential regulator RbpA. Elife 6, e22520 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo Y., Wang Y. & Steitz T. A. The mechanism of E. coli RNA polymerase regulation by ppGpp is suggested by the structure of their complex. Mol. Cell 50, 430–436 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae B. et al. Phage T7 Gp2 inhibition of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase involves misappropriation of σ70 domain 1.1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 19772–19777 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami K. S. X-ray crystal structure of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase σ70 holoenzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 9126–9134 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami K. S. Structural biology of bacterial RNA polymerase. Biomolecules 5, 848–864 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czyz A., Mooney R. A., Iaconi A. & Landick R. Mycobacterial RNA polymerase requires a U-tract at intrinsic terminators and is aided by NusG at suboptimal terminators. MBio 5, e00931 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis E., Chen J., Leon K., Darst S. A. & Campbell E. A. Mycobacterial RNA polymerase forms unstable open promoter complexes that are stabilized by CarD. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 433–445 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rammohan J., Ruiz Manzano A., Garner A. L., Stallings C. L. & Galburt E. A. CarD stabilizes mycobacterial open complexes via a two-tiered kinetic mechanism. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 3272–3285 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rammohan J. et al. Cooperative stabilization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis rrnAP3 promoter open complexes by RbpA and CarD. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 7304–7313 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stallings C. L. et al. CarD is an essential regulator of rRNA transcription required for Mycobacterium tuberculosis persistence. Cell 138, 146–159 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubin E. A. et al. Structural, functional, and genetic analyses of the actinobacterial transcription factor RbpA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 7171–7176 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane W. J. & Darst S. A. Molecular evolution of multisubunit RNA polymerases: sequence analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 395, 671–685 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae B., Feklistov A., Lass-Napiorkowska A., Landick R. & Darst S. A. Structure of a bacterial RNA polymerase holoenzyme open promoter complex. Elife 4, e08504 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umezawa Y. & Nishio M. CH/pi interactions as demonstrated in the crystal structure of guanine-nucleotide binding proteins, Src homology-2 domains and human growth hormone in complex with their specific ligands. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 6, 493–504 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandl M., Weiss M. S., Jabs A., Sühnel J. & Hilgenfeld R. C-H…pi-interactions in proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 307, 357–377 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallivan J. P. & Dougherty D. A. Cation-pi interactions in structural biology. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 9459–9464 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi K. & Ishihama A. Bipartite functional map of the E. coli RNA polymerase alpha subunit: involvement of the C-terminal region in transcription activation by cAMP-CRP. Cell 65, 1015–1022 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G. & Darst S. A. Structure of the Escherichia coli RNA polymerase alpha subunit amino-terminal domain. Science 281, 262–266 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourse R. L., Ross W. & Gaal T. UPs and downs in bacterial transcription initiation: the role of the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase in promoter recognition. Mol. Microbiol. 37, 687–695 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild A. & Dove S. L. Protein-protein contacts that activate and repress prokaryotic transcription. Cell 92, 597–600 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busby S. J. W. & Ebright R. H. Transcription activation by catabolite activator protein (CAP). J. Mol. Biol. 293, 199–213 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoff B. et al. Structural basis of transcription activation: the CAP-alpha CTD-DNA complex. Science 297, 1562–1566 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross W., Schneider D. A., Paul B. J., Mertens A. & Gourse R. L. An intersubunit contact stimulating transcription initiation by E coli RNA polymerase: interaction of the alpha C-terminal domain and sigma region 4. Genes Dev. 17, 1293–1307 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. et al. Comparative analysis of regulatory elements between Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae by genome-wide transcription start site profiling. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002867 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes T. et al. Genome-wide mapping of transcriptional start sites defines an extensive leaderless transcriptome in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell Rep. 5, 1121–1131 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey T. L. et al. MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, W202–W208 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vvedenskaya I. O. et al. Massively systematic transcript end readout, ‘MASTER’: transcription start site selection, transcriptional slippage, and transcript yields. Mol. Cell 60, 953–965 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shultzaberger R. K., Chen Z., Lewis K. A. & Schneider T. D. Anatomy of Escherichia coli 70 promoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 771–788 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley M. et al. Escherichia coli K-12: a cooperatively developed annotation snapshot--2005. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 1–9 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole S. T. et al. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393, 537–544 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrem S. T., Gaal T., Ross W. & Gourse R. L. Identification of an UP element consensus sequence for bacterial promoters. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 9761–9766 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pribnow D. Nucleotide sequence of an RNA polymerase binding site at an early T7 promoter. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 72, 784–788 (1975). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pribnow D. Bacteriophage T7 early promoters - nucleotide-sequences of 2 RNA-polymerase binding-sites. J. Mol. Biol. 99, 419 (1975). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feklistov A. & Darst S. A. Structural basis for promoter-10 element recognition by the bacterial RNA polymerase σ Subunit. Cell 147, 1257–1269 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keilty S. & Rosenberg M. Constitutive function of a positively regulated promoter reveals new sequences essential for activity. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 6389–6395 (1987). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer L. M., Koonin E. V. & Aravind L. Evolution of bacterial RNA polymerase: implications for large-scale bacterial phylogeny, domain accretion, and horizontal gene transfer. Gene 335, 73–88 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chlenov M. et al. Structure and function of lineage-specific sequence insertions in the bacterial RNA polymerase β′ subunit. J. Mol. Biol. 353, 138–154 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell E. A. et al. Structure of the bacterial RNA polymerase promoter specificity sigma subunit. Mol. Cell 9, 527–539 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camarero J. A. et al. Autoregulation of a bacterial sigma factor explored by using segmental isotopic labeling and NMR. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 8536–8541 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombroski A. J., Walter W. A., Record M. T. Jr, Siegele D. A. & Gross C. A. Polypeptides containing highly conserved regions of transcription initiation factor sigma 70 exhibit specificity of binding to promoter DNA. Cell 70, 501–512 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz E. C. et al. A full-length group 1 bacterial sigma factor adopts a compact structure incompatible with DNA binding. Chem. Biol. 15, 1091–1103 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson C. & Dombroski A. J. Region 1 of sigma70 is required for efficient isomerization and initiation of transcription by Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J. Mol. Biol. 267, 60–74 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuthoori S., Bowers C. W., McCracken A., Dombroski A. J. & Hinton D. M. Domain 1.1 of the σ70 subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase modulates the formation of stable polymerase/promoter complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 309, 561–572 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekler V. et al. Structural organization of bacterial RNA polymerase holoenzyme and the RNA polymerase-promoter open complex. Cell 108, 599–614 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rost B., Yachdav G. & Liu J. The PredictProtein server. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, W321–W326 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linding R. et al. Protein disorder prediction: implications for structural proteomics. Structure 11, 1453–1459 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das R. K. & Pappu R. V. Conformations of intrinsically disordered proteins are influenced by linear sequence distributions of oppositely charged residues. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 13392–13397 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. et al. Structural basis of transcription initiation. Science 338, 1076–1080 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo Y. & Steitz T. A. Crystal structures of the E. coli transcription initiation complexes with a complete bubble. Mol. Cell 58, 534–540 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber T. M. & Bryant D. A. Molecular systematic studies of eubacteria, using sigma70-type sigma factors of group 1 and group 2. J. Bacteriol. 179, 1734–1747 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opalka N. et al. Complete structural model of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase from a hybrid approach. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000483 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W. et al. Structural basis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis transcription and transcription inhibition. Mol. Cell 66, 169–179 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria to guide research, discovery, and development of new antibiotics. http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/global-priority-list-antibiotic-resistant-bacteria/en/ (2017).

- Twist K.-A. et al. A novel method for the production of in vivo-assembled, recombinant Escherichia coli RNA polymerase lacking the α C-terminal domain. Protein Sci. 20, 986–995 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin A. et al. Collaboration gets the most out of software. Elife 2, e01456 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z. & Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 267, 307–326 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy A. J. et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams P. D. et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P. & Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaal T. et al. Promoter recognition and discrimination by EsigmaS RNA polymerase. Mol. Microbiol. 42, 939–954 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feklistov A. et al. A basal promoter element recognized by free RNA polymerase σ Subunit determines promoter recognition by RNA polymerase holoenzyme. Mol. Cell 23, 97–107 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugen S. P. et al. rRNA promoter regulation by nonoptimal binding of σ region 1.2: an additional recognition element for RNA polymerase. Cell 125, 1069–1082 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker N. A., Sept D., Joseph S., Holst M. J. & McCammon J. A. Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 10037–10041 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider T. D. & Stephens R. M. Sequence logos: a new way to display consensus sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 18, 6097–6100 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonetto M., Gribskov M. & Gross C. A. The sigma 70 family: sequence conservation and evolutionary relationships. J. Bacteriol. 174, 3843–3849 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original 2.76 Å resolution Msm RbpA/EσA/us-fork coordinates (5TW1)4 have been updated by the addition of some water molecules, including the ordered water facilitating αCTD binding to DNA (Fig. 3c,d) and have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession ID 5VI8. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates and structure factor file for the Msm RbpA/RPo structure have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession ID 5VI5. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.