Abstract

Background

Insulin resistance is highly prevalent among patients with atherosclerosis and is associated with an increased risk for myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke. The Insulin Resistance Intervention after Stroke (IRIS) trial demonstrated that pioglitazone decreased the composite risk for fatal or non-fatal stroke and MI in patients with insulin resistance without diabetes, after a recent ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack. The type and severity of cardiac events in this population, and the impact of pioglitazone on these events has not been described.

Methods

We performed a secondary analysis of the effects of pioglitazone, compared to placebo, on acute coronary syndromes (ACS) (MI and unstable angina) among IRIS participants. All potential ACS episodes were adjudicated in a blinded fashion by an independent clinical events committee.

Results

The study cohort was composed of 3876 IRIS participants, mean age 63 years, 65% male, 89% white race, and 12% with a history of coronary artery disease. Over a median follow-up of 4.8 years, there were 225 ACS events, including 141 MI's and 84 episodes of unstable angina. The MI's included 28 (19%) with ST-segment elevation. The majority of MI's were type 1 (94, 65%), followed by type 2 (45, 32%). Serum troponin was 10× to 100× upper limit of normal (ULN) in 49 (35%) and >100× ULN in 39 (28%). Pioglitazone reduced the risk of ACS (hazard ratio [HR] 0.71, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.54, 0.94; p=0.02). Pioglitazone also reduced the risk of type 1 MI (HR 0.62, 95% CI, 0.40, 0.96; log-rank p=0.03) but not type 2 MI (HR 1.05, 95% CI 0.58, 1.91; p=0.87). Similarly, pioglitazone reduced the risk of large MI's with serum troponin >100× ULN (HR 0.44, 95% CI, 0.22, 0.87; p=0.02), but not smaller MI's.

Conclusions

Among patients with insulin resistance without diabetes, pioglitazone reduced the risk for acute coronary syndromes after a recent cerebrovascular event. Pioglitazone appeared to have its most prominent effect in preventing spontaneous type 1 MI's.

Keywords: Insulin resistance, pioglitazone, ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction

Subject Terms: Cerebrovascular Disease/Stroke, Ischemic Stroke, Myocardial Infarction, Metabolic Syndrome, Acute Coronary Syndromes

Introduction

Insulin resistance is a common condition in which intracellular insulin signaling is impaired, resulting in compensatory hyperinsulinemia and, eventually, hyperglycemia and type 2 diabetes in those who also develop relative insulin secretory impairment. Risk factors include family history, older age, central obesity, and greater weight. In epidemiologic research, insulin resistance is associated with an increased risk for both myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke. This condition is highly prevalent in patients with established cardiovascular disease.1-3 We recently reported that insulin resistance was present in 63% of patients without diabetes after a recent ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA).4 Because of the strong association of insulin resistance with vascular disease, there is emerging interest in whether interventions that ameliorate insulin resistance reduce cardiovascular risk in patients without diabetes.

The most effective drugs for reducing insulin resistance are the thiazolidinedione (TZD) class of PPAR-γ agonists, which include pioglitazone and rosiglitazone.5 Both drugs improve insulin sensitivity, prevent (or delay) diabetes in patients at risk, and improve glycemic control in patients with established type 2 diabetes. One of them, pioglitazone, has been shown to prevent clinical macrovascular events in patients with cerebrovascular disease. In 2005, the Prospective Pioglitazone Clinical Trial in Macrovascular events (PROactive) trial of patients with diabetes, found that pioglitazone reduced risk for a secondary outcome of cardiovascular mortality and non-fatal stroke or MI by 28% (p=0.047) in the subgroup who entered with a history of stroke.6 The Insulin Resistance Intervention in Stroke (IRIS) trial extended the evidence for the effectiveness of pioglitazone to patients with insulin resistance without diabetes and a recent stroke or TIA. Compared to placebo, pioglitazone reduced insulin resistance, prevented onset of diabetes, improved hsCRP and reduced the risk for the primary outcome of fatal or non-fatal stroke or MI by 24% (p=0.007).4

Pioglitazone, compared to glimepiride, reduces the progression of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with type 2 diabetes.7 Pioglitazone also reduces coronary inflammation,8 alters coronary plaque composition by reducing necrotic core,9,10 and prevents intimal hyperplasia after coronary stenting, 11,12 in patients with and without diabetes. Thus, in this analysis of the IRIS study, we tested the hypothesis that pioglitazone's coronary artery anti-atherosclerotic and potential vascular stabilizing effects might result in the reduction of acute coronary syndromes in insulin-resistant patients. We analyzed the effects of pioglitazone treatment on the incidence and timing of cardiac ischemic events, including spontaneous type 1 MI, using the 2012 Third Universal definition of MI.13

Methods

Study Participants

The design and primary results of IRIS have been published.4, 14 The study was approved by the Yale Human Investigation Committee, and IRB's at each of the participating sites, and the participants gave written informed consent. In this multinational, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, patients were required to have had a qualifying ischemic stroke or TIA within six months of randomization and insulin resistance as defined by a value greater than 3.0 on the Homeostasis Model Assessment-Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) ((fasting insulin, μU/ml X fasting glucose, mmol/L) /22.5). This threshold was chosen because it identifies the highest quartile among populations without diabetes.15, 16 Since insulin sensitivity is impaired after a week of bedrest17 and may be impaired for 2 weeks following a stroke,18 the screening blood test was conducted at least 14 days after the index event. Patients with diabetes were excluded. Diabetes was defined if a patient was taking medication for diabetes within 90 days of screening, met (2005) American Diabetes Association (ADA) criteria19 for diabetes (fasting plasma glucose ≥7 mmol/L (126 mg/dL), confirmed by repeat test) or had a HbA1c ≥53 mmol/mol (7.0%) at screening.

Patients with heart failure were excluded because of the potential for fluid retention related to pioglitazone therapy.14 In the initial protocol, patients with New York Heart Association class III or IV heart failure or class II heart failure with reduced ejection fraction were excluded in accordance with a 2003 consensus statement from the American Heart Association and ADA.20 In 2008, the exclusion was again expanded to patients with any history of heart failure, and previously randomized participants with a history of heart failure were permanently removed from study drug. The trial was monitored by an independent data and safety monitoring board (DSMB) appointed by the funding agency, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Study Procedures

Eligible participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to pioglitazone or matching placebo. Contingent upon the absence of signs and symptoms of heart failure or fluid retention, study medication was titrated over 8 weeks from 15 mg daily to a target dose of pioglitazone 45 mg daily or matching placebo. If participants subsequently reported shortness of breath, excessive weight gain or edema, study drug was reduced or discontinued according to pre-specified algorithms. Any patient who developed new or worsening heart failure was removed from study drug even if their symptoms had improved with dose reduction or diuretic therapy.

Cardiac Outcomes

The primary outcome in IRIS was time to first fatal or non-fatal stroke or MI. Time to first episode of acute coronary syndrome (ACS), defined as acute MI or unstable angina, was a pre-specified secondary outcome for IRIS.

When IRIS was initiated in 2005, the original protocol used criteria for cardiac outcomes that were based on the 2000 Consensus Conference of the European and American Colleges of Cardiology for MI21 and definitions used in the Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study (AFCAPS/TexCAPS) study for unstable angina.22 In 2012, the Third Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction13 was published. It is considered the current standard for diagnosis of MI and provides criteria for 5 subcategories of MI based on presumptive pathophysiologic mechanisms. Following its publication, the IRIS Operations and Steering Committees agreed to pre-specify an additional secondary analysis evaluating the effect of pioglitazone on acute MI according to the revised definition. The NINDS appointed DSMB was aware of this decision. The online supplement provides detailed criteria for cardiac outcomes (Supplementary Table 1). Each suspected cardiac event (unstable angina or myocardial infarction) was adjudicated by an independent external committee who were blinded to treatment assignment. Events were adjudicated using both the 2000 and 2012 criteria for MI. Two blinded investigators (LHY, JC) independently extracted information on the type, setting and maximal level of troponin elevation for events meeting the updated 2012 criteria for MI. Any differences were reconciled by consensus.

Statistical Analysis

The time to the first episode of adjudicated ACS (MI or unstable angina), MI alone, and unstable angina alone, were analyzed by intention to treat. In time-to-event analyses, patients without outcome events were censored at the date of the last completed follow-up contact. Cumulative event-free rates were calculated by the method of Kaplan-Meier23 and treatment group differences were tested by the log-rank statistic using a type I error of 0.05 (2-sided). The effect of pioglitazone relative to placebo was estimated as a hazard ratio (HR) from a Cox model24 with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We examined the effect of pioglitazone on the risk of MI overall, and according to the presence or absence of ST-segment elevation, the setting (MI type), and the level of troponin elevation. In exploratory analysis, we also examined the risk of a clinically important MI, defined as an event associated with ST-segment elevation, troponin increase > 100× upper limit of normal (ULN) or death, by treatment group. The decision to perform these analyses was made in all cases prior to evaluating the effect of study drug on outcome. In the primary report of IRIS, the outcome of acute coronary syndrome was one of five time-to-event secondary outcomes, and was accordingly adjusted for multiple testing.4 In this report, the analyses of ACS outcomes using the 2012 MI criteria were not adjusted for multiplicity. SAS version 9.3 was used for all analyses (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

The IRIS cohort included 3876 participants with either ischemic stroke (3375, 87.1%) or TIA (483, 12.5%) who were randomized at 179 sites in seven countries between February 2005 and January 2013.4 Randomization yielded treatment groups with similar features at baseline (Table 1). Mean age was 63.5 years, 65.5% were men, 11.6% were African American and 3.8% Hispanic. Mean fasting glucose concentration was 5.5±0.6 mmol/L and HbA1C was 5.8±0.4%. Median values for insulin and HOMA were 19 μU/ml (interquartile range [IQR]=16, 25) and 4.6 (IQR=3.7, 6.2), respectively. Pre-diabetes defined by fasting glucose ≥5.5 mmol/L, but less than 7.0 mmol/L, was present in 41.6% of subjects. No participants were taking anti-hyperglycemic agents at baseline.

Table 1. Baseline Features by Treatment Group.

| Pioglitazone | Placebo | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic features | (n=1939) | (n=1937) | ||

| Age (yrs), mean ±SD | 63.5 ±10.6 | 63.5 ±10.7 | ||

| Male sex, no. (%) | 1293 | 66.7% | 1245 | 64.3% |

| Black race, no. (%) | 218 | 11.4% | 225 | 11.8% |

| Hispanic ethnic group, no. (%) | 75 | 3.9% | 72 | 3.7% |

| Clinical history, no. (%) | ||||

| Stroke at entry (vs. TIA) | 1693 | 87.8% | 1682 | 87.2% |

| Prior stroke (before index event) | 246 | 12.7% | 242 | 12.5% |

| Hypertension | 1380 | 71.2% | 1390 | 71.8% |

| Coronary artery disease | 241 | 12.4% | 221 | 11.4% |

| Myocardial infarction | 148 | 7.6% | 131 | 6.8% |

| Coronary artery bypass graft | 123 | 6.3% | 133 | 6.9% |

| Coronary angioplasty or stenting | 95 | 4.9% | 79 | 4.1% |

| Carotid artery intervention* | 132 | 6.8% | 155 | 8.0% |

| Atrial fibrillation | 134 | 6.9% | 130 | 6.7% |

| Current cigarette smoking | 323 | 16.7% | 299 | 15.4% |

| Physical examination | ||||

| Body mass index (kg/m2), mean SD | 29.9 ±5.6 | 30.0 ±5.3 | ||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean SD | 133.2 ±17.7 | 133.0 ±17.3 | ||

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean SD | 79.4 ±10.7 | 79.0 ±10.5 | ||

| Laboratory data | ||||

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L), mean SD | 5.5 ±0.6 | 5.5 ±0.5 | ||

| Insulin (IU/mL), median (Q1, Q3) | 19 (16, 26) | 19 (16, 25) | ||

| HOMA-IR, median (Q1, Q3) | 4.7 (3.8, 6.2) | 4.6 (3.7, 6.2) | ||

| HbA1c (%), mean SD | 5.8 ±0.4 | 5.8 ±0.4 | ||

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/L), mean SD | 2.3 ±0.8 | 2.3 ±0.8 | ||

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L)-men, mean SD | 1.1 ±0.3 | 1.1 ±0.3 | ||

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L)-women, mean SD | 1.4 ±0.3 | 1.4 ±0.3 | ||

| Triglycerides (mmol/L), mean SD | 1.6 ±0.8 | 1.6 ±0.8 | ||

| C-reactive protein, median (Q1, Q3) | 2.2 (1.0, 4.9) | 2.3 (1.1, 5.0) | ||

| Concomitant medications, no. (%) | ||||

| Antihypertensive | 1528 | 79.1% | 1541 | 79.8% |

| ACE inhibitor | 828 | 42.9% | 791 | 40.9% |

| ARB | 270 | 14.0% | 276 | 14.3% |

| Beta-blocker | 615 | 31.8% | 613 | 31.7% |

| Thiazide diuretic | 521 | 27.0% | 499 | 25.8% |

| Other anti-hypertensive | 518 | 26.8% | 521 | 27.0% |

| Lipid lowering agent | 1645 | 85.1% | 1641 | 85.0% |

| Statin | 1594 | 82.5% | 1592 | 82.4% |

| Fibrate | 58 | 3.0% | 53 | 2.7% |

| Lipid-lowering agent | 126 | 6.5% | 123 | 6.4% |

| Antiplatelet | 1776 | 91.9% | 1782 | 92.2% |

| Aspirin alone | 945 | 48.9% | 956 | 49.5% |

| Aspirin and other anti-platelet | 456 | 23.6% | 473 | 24.5% |

| Non-aspirin anti-platelet | 375 | 19.4% | 353 | 18.3% |

| Anticoagulant | 232 | 12.0% | 209 | 10.8% |

| Coumadin | 205 | 10.6% | 178 | 9.2% |

| Other anticoagulant | 27 | 1.4% | 31 | 1.6% |

| Anti-arrhythmic | 32 | 1.7% | 48 | 2.5% |

| Loop diuretic | 63 | 3.3% | 45 | 2.3% |

Data are presented as mean±SD (standard deviation) if normally distributed, otherwise median (25th percentile, 75% percentile) are reported.

Carotid endarterectomy, angioplasty or stenting before or after index event.

Number of participants with missing data (pioglitazone, placebo): Black race (33,33); Hispanic (12,8); prior stroke (1,2); hypertension history (1,1); MI history (3,3); coronary intervention (1,1); carotid intervention (1,1); BMI (6,6); atrial fibrillation (2,0); blood pressure (6,6); LDL (21,17); HDL (5,3); triglycerides (4,3); CRP (17,12); prescription medications (7,5).

Cardiac risk factors were common but were generally well controlled with medications (Table 1). A history of hypertension was present in 71.5% of participants, and 41.9% were taking an ACE inhibitor, 14.1% an ARB, 31.8% a beta-blocker, 26.4% a thiazide diuretic and 26.9% other anti-hypertensive therapy. At baseline, 82.5% of participants were using statins, 2.9% fibrates and 6.4% other lipid lowering therapies. Mean values for LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides were 2.3 ±0.8 mmol/L, 1.2±0.3 mmol/L, and 1.6 ±0.8 mmol/L, respectively. Median CRP was 2.2 (IQR=1.0, 4.9). Current cigarette use at baseline was reported by 16.1% of participants.

While all participants qualified for the trial with an ischemic stroke or TIA, only 462 (11.9%) participants had a prior history of coronary artery disease based upon hospitalization for MI, coronary angioplasty or stenting, or coronary artery bypass grafting. In addition, 287 (7.4%) participants had a history of carotid artery intervention.

Antiplatelet agents were used by 3558 (92%) participants, including 1901 on aspirin alone, 929 on aspirin and another anti-platelet agent, and 728 on a non-aspirin anti-platelet agent alone. Oral anticoagulation therapy was used in 441 (11.4%) participants. Atrial fibrillation was not an exclusion for randomization because of the residual risk for recurrent stroke in these patients despite anticoagulation therapy.25 There was a history of atrial fibrillation in 264 (6.8%) participants, of whom 227 were on anticoagulant therapy and 36 were on antiplatelet drugs.

During the initial recruitment phase, 19 participants with NYHA class I-II heart failure symptoms without a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (<40%) were randomized; all were subsequently withdrawn from study drug in 2008 according to protocol but were retained in follow-up and are included in the analysis. Follow-up completed was similar in the pioglitazone and placebo groups: 7951 and 7952 person-years, respectively. A total of 301 patients became lost-to-follow-up (i.e., missed more than 12 months of follow-up) due to withdrawal of consent or becoming unable to be located (165 patients in pioglitazone group missed 501 person-years and 136 patients in the placebo group missed 435 patient-years) (Supplementary Figure 1).

Cardiac Outcomes

Patients were randomized a median of 80 days after the index event and followed for a median of 4.8 years. The incidence of ACS using the 2012 MI criteria was 5.1%, including 0.1% with fatal MI, 3.1% with non-fatal MI and 1.9% with unstable angina (Table 2). Of the 141 MIs, 28 were ST-segment elevation MIs (STEMIs), 98 were non-STEMIs and 15 events could not be classified due to inadequate information (Table 3). The setting of the MI was spontaneous (type 1) for 94 events, myocardial oxygen supply/demand imbalance (type 2) for 43, sudden death without biomarker ascertainment (type 3) in one, and after percutaneous coronary intervention (type 4a) in one other (Table 3). Serum troponin elevation was minimal (<3× ULN) in 20, mild (3-10× ULN) in 32, moderate (10-100× ULN) in 49 and severe (>100× ULN) in 39 MI events (Table 3). Severe troponin elevation was more common with type 1 MI (34 of 94) compared to type 2 MI (5 of 45) (chi-square p-value=.002) (Supplementary Table 1). Of the 128 participants with MI after randomization, 25% had reported a history of CAD at randomization; for the remaining 75% the MI event was the first manifestation of CAD.

Table 2. Acute Coronary Syndrome Events by 2012 Criteria, Overall and by Treatment Group.

| Cardiac Outcome | All Participants (n=3876) | Pioglitazone (n=1939) | Placebo (n=1937) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI)* | P† | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Events) | Pts. | % | (Events) | Pts. | % | (Events) | Pts. | % | |||

| Acute coronary syndrome | (225) | 199 | 5.1% | (99) | 83 | 4.3% | (126) | 116 | 6.0% | 0.71 (0.54, 0.94) | 0.02 |

| Fatal MI | 5 | 0.1% | 1 | 0.1% | 4 | 0.2% | |||||

| Non-fatal MI | 121 | 3.1% | 52 | 2.7% | 69 | 3.6% | |||||

| Unstable Angina | 73 | 1.9% | 30 | 1.5% | 43 | 2.2% | |||||

| Fatal or Non-fatal MI | (141) | 128 | 3.3% | (61) | 54 | 2.8% | (80) | 74 | 3.8% | 0.73 (0.51, 1.03) | 0.08 |

| Fatal MI | (5) | 5 | 0.1% | (1) | 1 | 0.1% | (4) | 4 | 0.2% | 0.25 (0.03, 2.24) | 0.22 |

| Non-fatal MI | (136) | 123 | 3.2% | (60) | 53 | 2.7% | (76) | 70 | 3.6% | 0.76 (0.53, 1.08) | 0.12 |

| Unstable Angina | (84) | 77 | 2.0% | (38) | 33 | 1.7% | (46) | 44 | 2.3% | 0.75 (0.48, 1.18) | 0.21 |

Unadjusted 95% confidence interval (CI)

Unadjusted p-value from log-rank test.

Table 3. Myocardial Infarctions (2012 criteria), Overall and by Treatment Group.

| All Participants (n=3876) | Pioglitazone (n=1939) | Placebo (n=1937) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI)* | P† | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Events) | Pts. | % | (Events) | Pts. | % | (Events) | Pts. | % | |||

| Any MI | (141) | 128 | 3.3% | (61) | 54 | 2.8% | (80) | 74 | 3.8% | 0.73 (0.51, 1.03) | 0.08 |

| STEMI vs Non-STEMI | |||||||||||

| ST-segment elevation MI | (28) | 28 | 0.7% | (12) | 12 | 0.6% | (16) | 16 | 0.8% | 0.75 (0.35, 1.58) | 0.45 |

| Non-STEMI | (98) | 86 | 2.2% | (44) | 38 | 2.0% | (54) | 48 | 2.5% | 0.79 (0.52, 1.21) | 0.28 |

| Unknown | (15) | 15 | 0.4% | (5) | 5 | 0.3% | (10) | 10 | 0.5% | 0.50 (0.17, 1.46) | 0.20 |

| MI Setting | |||||||||||

| Spontaneous (type 1) | (94) | 86 | 2.2% | (39) | 33 | 1.7% | (55) | 53 | 2.7% | 0.62 (0.40, 0.96) | 0.03 |

| Oxygen imbalance (type 2) | (45) | 43 | 1.1% | (22) | 22 | 1.1% | (23) | 21 | 1.1% | 1.05 (0.58, 1.91) | 0.87 |

| Sudden death (type 3) | (1) | 1 | 0.0% | (0) | 0 | 0.0% | (1) | 1 | 0.1% | ||

| After PCI (type 4a) | (1) | 1 | 0.0% | (0) | 0 | 0.0% | (1) | 1 | 0.1% | ||

| Troponin (Tp) Elevation (xULN) | |||||||||||

| 1-3× (minimal) | (20) | 19 | 0.5% | (9) | 9 | 0.5% | (11) | 10 | 0.5% | 0.90 (0.37, 2.22) | 0.82 |

| 3-10× (mild) | (32) | 32 | 0.8% | (16) | 16 | 0.8% | (16) | 16 | 0.8% | 1.00 (0.50, 2.00) | 0.99 |

| 10-100× (moderate) | (49) | 45 | 1.2% | (24) | 20 | 1.0% | (25) | 25 | 1.3% | 0.80 (0.44, 1.44) | 0.46 |

| >100× (severe) | (39) | 39 | 1.0% | (12) | 12 | 0.6% | (27) | 27 | 1.4% | 0.44 (0.22, 0.87) | 0.02 |

| Unknown | (1) | (0) | (1) | ||||||||

| Fatal MI, STEMI, Tp >100×ULN | (54) | 54 | 1.4% | (18) | 18 | 0.9% | (36) | 36 | 1.9% | 0.50 (0.28, 0.88) | 0.02 |

Unadjusted 95% confidence interval (CI).

Unadjusted p-value from log-rank test.

Effect of Pioglitazone on Cardiac Outcomes

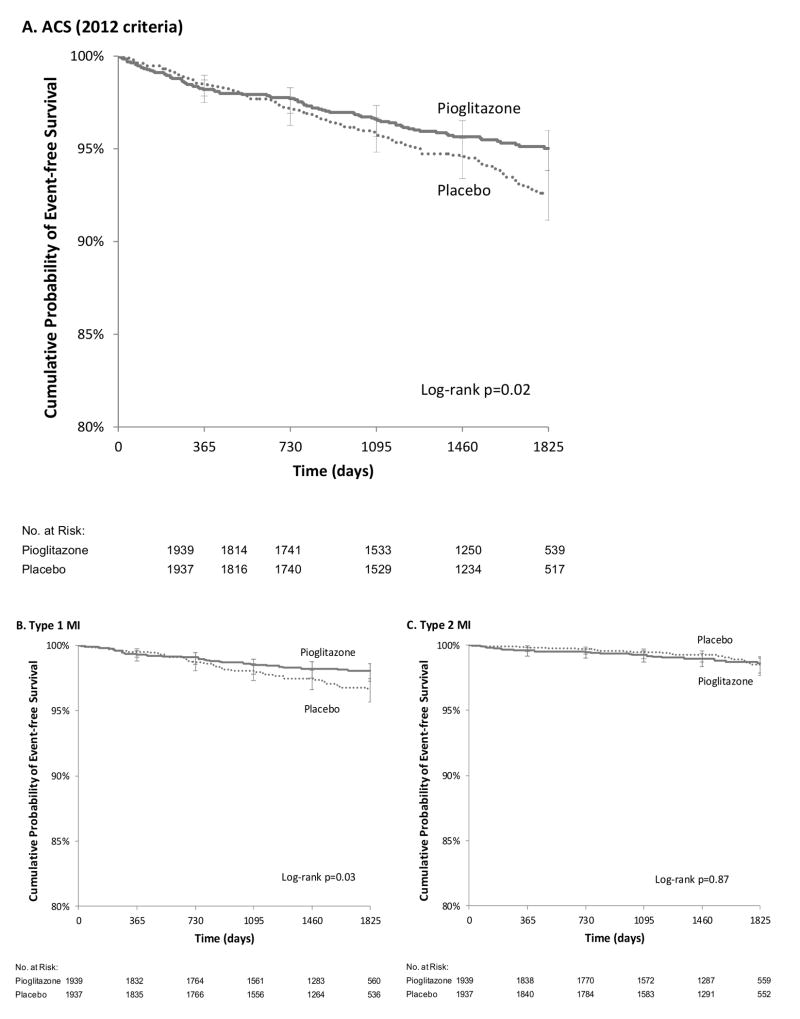

Using 2012 criteria for MI, there were a total of 99 ACS events (61 MIs and 38 episodes of unstable angina) in 83 participants in the pioglitazone group compared to 126 events (80 MIs and 46 episodes of unstable angina) in 116 participants in the placebo group (HR 0.71, 95% CI, 0.54, 0.94, p=0.02) (Table 2). Pioglitazone was associated with a similar directional change in each component of ACS, with a reduction in fatal MI, non-fatal MI and unstable angina events (Table 2). ACS-free survival curves showed separation after two years (p=0.02) (Figure 1a).

Figure 1. Time to First Cardiac Event by Type and Treatment Group.

A. Acute Coronary Syndrome (2012 criteria). B. Type 1 Myocardial Infarction. C. Type 2 Myocardial Infarction.

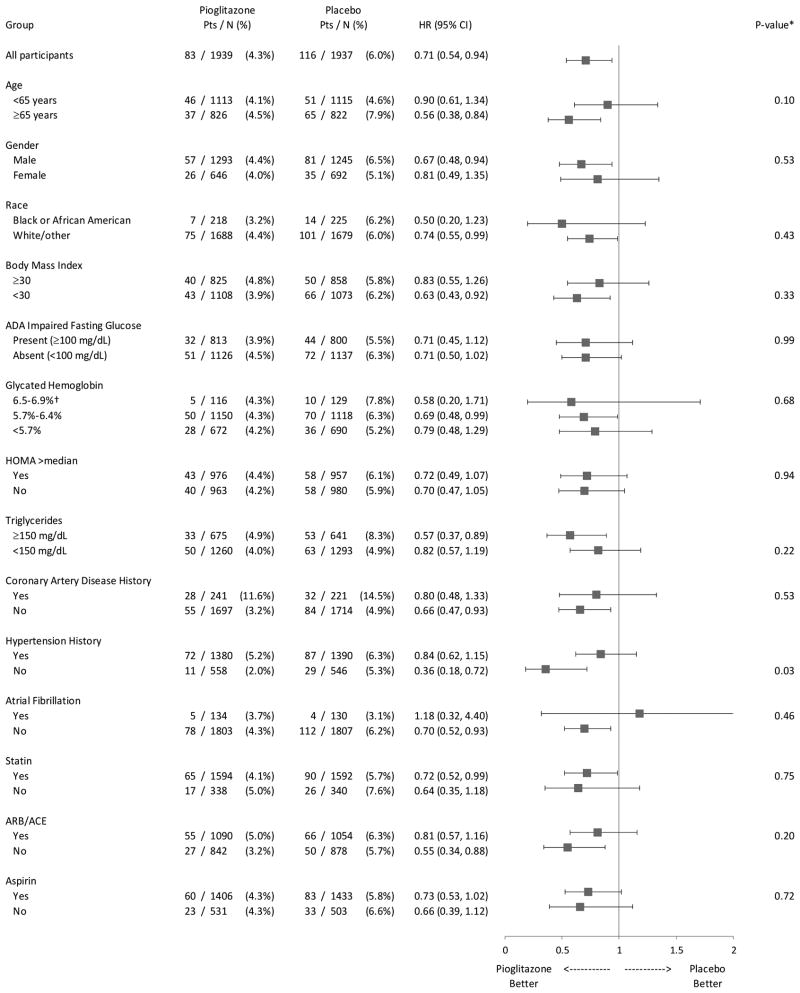

The effect of pioglitazone on ACS risk was uniform across most subgroups examined, including patients with and without impaired fasting glucose, HOMA values above and below the median, and by use of cardiovascular therapies, including statins, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors, and aspirin (Figure 2). Pioglitazone was associated with a reduction in ACS events in patients without a history of CAD at baseline (HR 0.66, 95% CI, 0.47, 0.93), with a similar trend in the smaller subgroup with a history (HR 0.80, 95% CI 0.48, 1.33). In patients with no history of hypertension at baseline, the hazard ratio was significantly lower (HR 0.36, 95% CI 0.18, 0.72) than the hazard ratio observed in patients with a history of hypertension (HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.62, 1.15) (p-value for interaction=0.03). Because p-values were not adjusted for multiple testing, this finding may be attributable to chance.

Figure 2. Risk of Acute Coronary Syndrome (2012 criteria), Overall and by Subgroups.

(*P-value is from test for interaction between treatment and each subgroup unadjusted for multiplicity. †Participants with HbA1c below 7.0%, the usual target for treatment, were permitted to enroll.)

The risk for MI was lower in the pioglitazone group compared to the placebo group, but did not reach statistical significance (HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.51, 1.03; p=0.08) (Table 2). However, pioglitazone significantly reduced the risk of spontaneous type 1 MI (HR 0.62, 95% CI 0.40, 0.96; p=0.03). In contrast, there was no effect of pioglitazone on type 2 MI (HR 1.05, 95% CI 0.58, 1.91; p=0.87) (Table 3, Figure 1b-c). In a pre-specified exploratory analysis, pioglitazone had a greater effect in reducing risk for MI events associated with ST-segment elevation, troponin increase >100× ULN, or death (18 vs. 36 patients; HR 0.50, 95% CI 0.28, 0.88; p=0.02) compared with less severe MI events (33 vs. 34 patients; HR 0.97, 95% CI 0.60, 1.57; p=0.91) (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 2). Among patients with MI in the placebo group, median peak troponin was 37× ULN; among patients with MI in the pioglitazone group it was 15 × ULN (Wilcoxon rank-sum p-value: 0.18).

Effect of pioglitazone on cardiac outcomes using the original IRIS criteria

The IRIS trial was initiated prior to the 2012 Third Universal Definition of MI. The original IRIS MI criteria had a higher troponin threshold (>2× for spontaneous MI) and included patients with presumed sudden cardiac death. Adjudications based on the original IRIS criteria resulted in the reclassification of 47 events: 12 non-fatal MIs changed to episodes of unstable angina, 3 non-fatal MIs changed to no event, 8 ruled-out events changed to non-fatal MI, and 24 ruled-out events changed to presumed sudden cardiac death (i.e., fatal MI). Despite these differences in the adjudication criteria, the beneficial effect of pioglitazone on ACS outcomes was very similar to that using the 2012 Third Universal Definition of MI (unadjusted HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.57, 0.97, p=0.03) (Table 4, Supplementary Figure s2).

Table 4. Acute Coronary Syndrome Events by Original Criteria, Overall and by Treatment Group.

| Cardiac Outcome | All Participants (n=3876) | Pioglitazone (n=1939) | Placebo (n=1937) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI)* | P† | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Events) | Pts. | % | (Events) | Pts. | % | (Events) | Pts. | % | |||

| Acute coronary syndrome‡ | (254) | 224 | 5.8% | (114) | 96 | 5.0% | (140) | 128 | 6.6% | 0.75 (0.57, 0.97) | 0.03 |

| Fatal MI | 26 | 0.7% | 11 | 0.6% | 15 | 0.8% | |||||

| Non-fatal MI | 116 | 3.0% | 51 | 2.6% | 65 | 3.4% | |||||

| Unstable angina | 82 | 2.1% | 34 | 1.8% | 48 | 2.5% | |||||

| MI, fatal or non-fatal | (158) | 144 | 3.7% | (70) | 62 | 3.2% | (88) | 82 | 4.2% | 0.75 (0.54, 1.05) | 0.09 |

| Fatal MI | (29) | 29 | 0.7% | (12) | 12 | 0.6% | (17) | 17 | 0.9% | 0.70 (0.34, 1.47) | 0.35 |

| Non-fatal MI | (129) | 118 | 3.0% | (58) | 51 | 2.6% | (71) | 67 | 3.5% | 0.76 (0.53, 1.09) | 0.14 |

| Unstable angina | (96) | 87 | 2.2% | (44) | 38 | 2.0% | (52) | 49 | 2.5% | 0.77 (0.51, 1.18) | 0.24 |

Unadjusted 95% confidence interval (CI)

Unadjusted p-value from log-rank test.

Discussion

This analysis of the results of the IRIS trial provides insight into the characteristics of acute coronary syndromes that occur after ischemic stroke or TIA. Importantly, it also demonstrates that pioglitazone, a TZD class PPARγ agonist with potent insulin sensitizing effects, reduced the risk of ACS, particularly the most serious events in insulin-resistant patients without diabetes. These findings were evident for both ACS components (i.e., unstable angina and MI). The beneficial effect of pioglitazone was most prominent in spontaneous type 1 MI, with no effect observed on type 2 MI. When we dichotomized MI according to severity, pioglitazone was more effective in preventing more clinically significant MIs characterized by ST-segment elevation, troponin > 100× ULN, or death.

Coronary artery disease is relatively common in patients with ischemic stroke and these individuals are known to be at risk for subsequent cardiac events.28, 29 Only 12% of IRIS participants had a prior history of coronary artery disease (defined as MI, percutaneous coronary artery intervention or CABG). As expected, these subjects were at greater risk for ACS events compared to patients without such a history (14.5% vs. 4.9% in placebo group). Nonetheless, pioglitazone was associated with a significant reduction in ACS events in the larger sub-group of patients without pre-existing coronary artery disease.

The risk reduction for ACS in IRIS occurred despite broad use of background evidence-based cardiovascular preventive therapies, including statins, anti-platelet agents, and anti-hypertensive drugs. These results indicate that a substantial portion of residual coronary risk in patients with insulin resistance without diabetes is modifiable by additional treatment with pioglitazone. The reduction in ACS risk in IRIS was independent of effects on LDL cholesterol; in fact, pioglitazone slightly increased LDL cholesterol.4 Although TZDs increase LDL cholesterol, they have little effect on particle number, but rather increase LDL particle size which may render LDL less atherogenic.30 It is important to note that 82% of our patients were on statins, a therapy shown in the SPARCL trial of high-dose atorvastatin to be effective after stroke for reducing risk of both recurrent stroke and ACS.29 Furthermore, because of the widespread use of statins in IRIS, LDL concentrations remained in a desirable range in both treatment groups during follow-up (overall mean ±standard error, 2.32 ±0.02 mmol/L in the pioglitazone group and 2.28 ±0.02 mmol/L) in the placebo group).

Pioglitazone appeared to be particularly effective in reducing the more clinically important ACS outcomes, defined as MIs associated with ST elevation, large troponin increase (>100× ULN) or death. Moreover, pioglitazone reduced the incidence of spontaneous (type 1) MI events, but not those induced by supply/demand imbalance (type 2). The former finding suggests a benefit of pioglitazone to stabilize coronary atheroma, possibly through anti-inflammatory effects. Pioglitazone is known to reduce coronary arterial inflammation8 and in the IRIS trial, pioglitazone reduced CRP by 25% at one year after randomization.4 The latter finding is notable since the vast majority (82%) of patients were already treated with statins. Pioglitazone may also have acted to reduce type 1 MI by retarding the progression of atherosclerosis,7 reducing the necrotic core of plaques,9, 10 or exerting anti-thrombotic effects.31 In contrast, pioglitazone did not appear to prevent type 2 MIs, which were characterized by lower levels of troponin elevation. This category of MI is usually attributed to hemodynamic or metabolic stress (e.g. sepsis, trauma, GI bleeding, rapid atrial fibrillation and hypoxemia), which may not have been affected by pioglitazone treatment. Alternatively, pioglitazone might have had coronary atheroprotective and anti-inflammatory actions that were counter-balanced by volume expansion, anemia or minor reductions in blood pressure,4 resulting in a neutral overall effect on the incidence of type 2 MI.

Our primary analysis of ACS events used the Third Universal Definition of MI criteria, which were published in 201213 during the course of the trial. This was a pre-specified analysis, but we also evaluated the results using the originally designated IRIS study criteria14 that were based on the 2000 Consensus Conference criteria.21 Overall, these analyses yielded very similar point estimates for the benefit of pioglitazone on both ACS and MI events. Although the 2012 criteria are now considered the standard for clinical trials, the convergence of results using the original IRIS criteria provide additional support for a therapeutic benefit of pioglitazone. The 2012 criteria are more conservative in excluding patients with presumed sudden cardiac death, but are arguably less stringent in including events with troponin elevations in the 1-2× ULN range, these being categorized as unstable angina with the 2000 criteria.

Although IRIS is the first study to demonstrate the efficacy of pioglitazone for reducing risk of ACS in patients with insulin resistance without diabetes after stroke or TIA, pioglitazone had been shown previously to have benefit in preventing cardiovascular complications in patients with macrovascular disease and type 2 diabetes.32 In a post-hoc analysis of the PROactive study, among the entire cohort, pioglitazone reduced the risk of the composite outcome of cardiac death, nonfatal MI, and ACS.33 Taken together with the current analysis, these data support the efficacy of pioglitazone for prevention of cardiovascular events in patients with vascular disease and a metabolic disorder as manifested by either diabetes or insulin resistance.

Limitations of the current analysis warrant consideration. First, IRIS was designed to test the effects of pioglitazone on the composite outcome of stroke and MI and was not powered adequately to show an effect on MI alone. Although ACS (including both MI and unstable angina) was a pre-specified secondary endpoint, the statistically significant benefit of pioglitazone on ACS was demonstrated without adjustment for multiple secondary outcomes. Second, similar to prior stroke trials,29, 34, 35 there was loss to follow-up in IRIS patients; although the missingness of follow-up was similar, we cannot exclude the possibility that outcome events were differentially missed in the two treatment groups. Third, it remains uncertain whether the benefits of pioglitazone were related to insulin sensitization, additional effects of PPAR-γ activation and/or other pharmacological effects of pioglitazone. Fourth, it is uncertain whether pioglitazone would be effective as secondary prevention therapy after myocardial infarction or ACS, as opposed to stroke or TIA. Last, the overall benefit of pioglitazone on cardiovascular outcomes needs to be considered in the context of the side effects of weight gain, edema and bone fracture.4 Heart failure is also a known risk associated with pioglitazone therapy.32 Although the incidence of serious heart failure was not increased in IRIS,4 this may reflect the exclusion of patients with pre-existing heart failure, as well as post-randomization procedures to reduce dose or discontinue treatment for excessive weight gain or edema, and to discontinue study drug for heart failure.

In conclusion, this analysis of the IRIS trial demonstrates that pioglitazone reduced the risk of ACS in patients with insulin resistance without diabetes after ischemic stroke or TIA. This benefit was derived from a reduction in the incidence of spontaneous type 1 MI, suggesting coronary artery plaque stabilization. The results warrant consideration as clinicians weigh the potential benefits and risks of pioglitazone as a secondary prevention therapy in patients with insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease.

Supplementary Material

Clinical perspective.

What is new?

The IRIS trial compared the effects of pioglitazone with placebo on major cardiovascular events after stroke or TIA in patients without diabetes who had evidence of insulin resistance.

IRIS showed that pioglitazone improved insulin resistance, prevented diabetes, improved CRP, and reduced fatal or non-fatal stroke or MI.

This secondary analysis of IRIS examined the effect of pioglitazone on acute coronary syndromes (MI or unstable angina).

Pioglitazone reduced the risk of these events by 29%, with benefit emerging after 2 years of treatment.

Pioglitazone reduced the incidence of type 1 (spontaneous) MI, with a neutral effect on type 2 (demand-related) MI.

What are the clinical implications?

Insulin resistance is highly prevalent among patients with stroke who do not have diabetes and is a marker of subsequent cardiovascular risk.

The present analysis suggests that pioglitazone may stabilize coronary atheroma in such patients, and may serve as a useful secondary prevention therapy in addition to statins, aspirin, and other established treatments.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients who participated in the IRIS trial and the study coordinators who implemented the protocol; and C. Moy, S. Janis, L. Gutmann and B. Radziszewska of the National Institutes of Health/NINDS.

Sources of Funding: This study was supported by a National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grant (U01-NS-044876-07). Pioglitazone and placebo were provided by Takeda Pharmaceuticals International.

Footnotes

Clinical Trial Registration: Clinicaltrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov), Unique Identifier: NCT00091949. US Food & Drug Administration IND: 64,622; EudraCT#2008-005546-23

Disclosures: L.H.Y. received research grant support unrelated to this study from Merck, Mifcor, and Novartis (to Yale University). C.M.V. received a consulting fee from Takeda Pharmaceuticals International for analyzing prostate cancer data in the IRIS trial. G.G.S. received research grant support unrelated to this study from Cerenis, Roche, Resverlogix, Sanofi, and The Medicines Company (to the University of Colorado). S.E.I. is a consultant to or has served on research steering committees for AstraZeneca (modest), Boehringer Ingelheim (significant), Daichii Sankyo (modest), Lexicson (modest) Janssen (modest), Merck (significant), Poxel (modest), Sanofi (modest), and vTv Pharmaceuticals (modest.) He has also served on data monitoring committees for Novo Nordisk (modest) and Intarcia (significant). No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1.Stubbs P, Alaghband-Zadeh J, Laycock J, Collinson P, Carter G, Noble M. Significance of an index of insulin resistance on admission in non-diabetic patients with acute coronary syndromes. Heart. 1999;82:443–447. doi: 10.1136/hrt.82.4.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartnik M, Rydén L, Ferrari R, Malmberg K, Pyörälä K, Simoons M, Standl E, Soler-Soler J, Ohrvik J, Investigators EHS. The prevalence of abnormal glucose regulation in patients with coronary artery disease across europe. The euro heart survey on diabetes and the heart. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1880–1890. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi K, Lee K, Kim S, Kim N, Park C, Seo H, Oh D, Choi D, Baik S. Inflammation, insulin resistance, and glucose intolerance in acute myocardial infarction patients without a previous diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:175–180. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kernan WN, Viscoli CM, Furie KL, Young LH, Inzucchi SE, Gorman M, Guarino PD, Lovejoy AM, Peduzzi PN, Conwit R, Brass LM, Schwartz GG, Adams HP, Jr, Berger L, Carolei A, Clark W, Coull B, Ford GA, Kleindorfer D, O' Leary JR, Parsons MW, Ringleb P, Sen S, Spence JD, Tanne D, Wang D, Winder T, for the IRIS Trial Investigators Pioglitazone after ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1321–1331. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soccio R, Chen E, Lazar M. Thiazolidinediones and the promise of insulin sensitization in type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2014;20:573–591. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilcox R, Bousser M-G, Betteridge DJ, Shernthaner G, Pirags V, Kupfer S, Dormandy JA, for the PROactive Investigators Effects of pioglitazone in patients with type 2 diabetes with or without previous stroke. Results from proactive (prospective pioglitazone clinical trial in macrovascular events 04) Stroke. 2007;38:865–873. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000257974.06317.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nissen SE, Nicholls SJ, Wolski K, Nesto R, Kupfer S, Perez A, Jure H, De Larochelliere R, Staniloae CS, Mavromatis K, Saw J, Hu B, Lincoff AM, Tuzcu EM, for the PERISCOPE Investigators Comparison of pioglitazone vs glimepiride on progression of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2008;299:1561–1573. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.13.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nitta Y, Tahara N, Tahara A, Honda A, Kodama N, Mizoguchi M, Kaida H, Ishibashi M, Hayabuchi N, Ikeda H, Yamagishi S, Imaizumi T. Pioglitazone decreases coronary artery inflammation in impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes mellitus: Evaluation by FDG-PET/CT imaging. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:1172–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogasawara D, Shite J, Shinke T, Watanabe S, Otake H, Tanino Y, Sawada T, Kawamori H, Kato H, Miyoshi N, Hirata K. Pioglitazone reduces the necrotic-core component in coronary plaque in association with enhanced plasma adiponectin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2009;73:343–351. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-08-0699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christoph M, Herold J, Berg-Holldack A, Rauwolf T, Ziemssen T, Schmeisser A, Weinert S, Ebner B, Said S, Strasser R, Braun-Dullaeus R. Effects of the PPARγ agonist pioglitazone on coronary atherosclerotic plaque composition and plaque progression in non-diabetic patients: A double-center, randomized controlled VH-IVUS pilot-trial. Heart Vessels. 2015;30:286–295. doi: 10.1007/s00380-014-0480-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takagi T, Yamamuro A, Tamita K, Yamabe K, Katayama M, Mizoguchi S, Ibuki M, Tani T, Tanabe K, Nagai K, Shiratori K, Morioka S, Yoshikawa J. Pioglitazone reduces neointimal tissue proliferation after coronary stent implantation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: An intravascular ultrasound scanning study. Am Heart J. 2003;146:e5. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marx N, Wohrel J, Nusser T, Walcher D, Rinker j, Hombach V, Koenig W, Hoher M. Pioglitazone reduces neointima volume after coronary stent implantation. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial in nondiabetic patients. Circulation. 2005;112:2792–2798. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.535484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thygesen K, Alpert J, Jaffe A, Simoons M, Chaitman B, White H, Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2012;126:2020–2035. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viscoli CM, Brass LM, Carolei A, Conwit R, Ford GA, Furie KL, Gorman M, Guarino PD, Inzucchi SE, Lovejoy AM, Parsons MW, Peduzzi PN, Ringleb PA, Schwartz GG, Spence JD, Tanne D, Young LH, Kernan WN, for the IRIS Trial investigators Pioglitazone for secondary prevention after ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack: Rationale and design of the insulin resistance intervention after stroke trial. Am Heart J. 2014;168:823–829. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.07.016. e826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balkau B, Charles MA, for the European Group for the Study of Insulin Resistance (EGIR) Comment on the provisional report from the who consultation. Diabetic Med. 1999;16:442–443. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.1999.00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ascaso JF, Pardo S, Real JT, Lorente RI, Priego A, Carmena R. Diagnosing insulin resistance by simple quantitative methods in subjects with normal glucose metabolism. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:3320–3325. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.12.3320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dirks M, Wall B, van de Valk B, Holloway T, Holloway G, Chabowski A, Goossens G, van Loon L. One week of bed rest leads to substantial muscle atrophy and induces whole-body insulin resistance in the absence of skeletal muscle lipid accumulation. Diabetes. 2016;65:2862–2875. doi: 10.2337/db15-1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huff TA, Lebovitz HE, Heyman A, Davis L. Serial changes in glucose utilization and insulin and growth hormone secretion in acute cerebrovascular disease. Stroke. 1972;3:543–552. doi: 10.1161/01.str.3.5.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:S37–S42. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.suppl_1.s37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nesto RW, Bell D, Bonow RO, Fonseca V, Grundy SM, Horton ES, LeWinter M, Porte D, Semenkovich CF, Smith S, Young L, Kahn R. Thiazolidinediones use, fluid retention, and congestive heart failure. Circulation. 2003;108:2941–2948. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000103683.99399.7E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee. Myocardial infarction redefined - a consensus document of the joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:959–969. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00804-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Downs JR, Beere PA, Whitney E, Clearfield M, Weis S, Rochen J, Stein EA, Shapiro DR, Langendorfer A, Gotto AM. Design and rationale of the air force/texas coronary atherosclerosis prevention study (AFCAPS/TEXCAPS) Am J Cardiol. 1997;80:287–293. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00347-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc. 1972;34:187–202. [Google Scholar]

- 25.The Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) Investigators. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1825–1833. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hochberg Y. A sharper bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika. 1988;75:800–802. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elfird J, Nielsen S. A method to compute multiplicity corrected confidence intervals for odds ratios and other relative effect estimates. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2008;5:394–398. doi: 10.3390/ijerph5050394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dhamoon MS, Tai W, Boden-Albala B, Rundek T, Paik MC, Sacco RL, Elkind MS. Risk of myocardial infarction or vascular death after first ischemic stroke. The Northern Manhattan Study. Stroke. 2007;38:1752–1758. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.480988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels (SPARCL) Investigators. High-dose atorvastatin after stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:549–559. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deeg MA, Buse JB, Goldberg RB, Kendall DM, Zagar AJ, Jacober SJ, Khan MA, perez AT, Tan MH, on behalf of the GLAI Study Investigators Pioglitazone and rosiglitazone have different effects on serum lipoprotein particle concentrations and sizes in patients with type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2458–2464. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mongan J, Mieszczanska H, Smith B, Messing S, Phipps R, Francis C. Pioglitazone inhibits platelet function and potentiates the effects of aspirin: A prospective observation study. Thromb Res. 2012;129:760–764. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dormandy JA, Charbonnel B, Eckland DJ, Erdmann E, Massi-Benedetti M, Moules IK, Skene AM, Tan MH, LeFefebvre PJ, Murray GD, Standl E, Wilcox RG, Wilhelmsen L, Betteridge J, Birkeland K, Golay A, Heine RJ, Koranyi L, Laakso M, Mokan M, Norkus A, Pirags V, Podar T, Sheen A, Scherbaum W, Shernthaner G, Schmitz O, Skrha J, Smith V, Taton J. Secondary prevention of macrovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Proactive study (prospective pioglitazone clinical trial in macrovascular events): A randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:1279–1289. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67528-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilcox R, Kupfer S, Erdmann E, PROactive Study investigators Effects of pioglitazone on major adverse cardiovascular events in high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes: Results from prospective pioglitazone clinical trial in macro vascular events (Proactive 10) Am Heart J. 2008;155:712–717. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Toole JF, Malinow MR, Chambless LE, Spence JD, Pettigrew LC, Howard VJ, Sides EG, Wang C-H, Sampfer M. Lowering homocysteine in patients with ischemic stroke to prevent recurrent stroke, myocardial infarction, and death. The vitamin intervention for stroke prevention (VISP) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:565–575. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.5.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.SPS3 Investigators. Effects of clopidogrel added to aspirin in patients with a recent lacunar stroke. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:817–825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.