Abstract

Objective

It is thought that an imbalance in serotonergic neurotransmission may underlie many affective disorders. Thus, the serotonin-1A (5-HT1A) receptor is a target for antidepressant and neuroleptic drugs. It has been reported that estrogens modulate serotonergic neurotransmission. Therefore, we investigated the effect of long-term ovariectomy on 5-HT1A receptor–specific binding and G-protein activation in the brain. Correction therapy with estradiol was compared with treatments using the selective estrogen receptor modulators tamoxifen and raloxifene.

Methods

Four months after ovariectomy, Sprague–Dawley rats were treated with vehicle, 17β-estradiol (80 μg/kg), tamoxifen (1 mg/kg) or raloxifene (1 mg/kg) subcutaneously for 2 weeks. Specific binding to 5-HT1A receptors was assessed by autoradiography of brain sections using the 5-HT1A agonist [3H]8-OH-DPAT. 5-HT1A receptor stimulation was measured using R-(+)-8-OH-DPAT-stimulated [35S]GTPγS-binding autoradiography.

Results

Ovariectomy decreased uterine weight, which was corrected by estradiol; tamoxifen and raloxifene partially corrected this decrease. Hormonal withdrawal and replacement left [3H]8-OH-DPAT-specific binding unchanged in the cortex. In contrast, ovariectomy induced a decrease in R-(+)-8-OH-DPAT-stimulated [35S]GTPγS-specific binding in the cortex; this was corrected by estradiol but was not corrected significantly by tamoxifen or raloxifene. In the hippocampus, ovariectomy had no effect on [3H]8-OH-DPAT-specific binding, whereas only 17β-estradiol treatment decreased this binding in a subregion of the CA3. Ovariectomy increased R-(+)-8-OH-DPAT-stimulated [35S]GTPγS-specific binding in the dentate gyrus (but not in the CA1 or CA3); this was corrected by estradiol and raloxifene, but not by tamoxifen. In the dorsal raphe nucleus, ovariectomy increased [3H]8-OH-DPAT-specific binding and R-(+)-8-OH-DPAT-stimulated [35S]GTPγS-specific binding; estradiol corrected this increase, but this was not corrected significantly by tamoxifen or raloxifene.

Conclusions

An overall stimulation by estradiol of 5-HT1A receptor–specific binding and coupling was observed, decreasing raphe somatodendritic receptors and increasing cortical postsynaptic receptors.

Medical subject headings: estrogens; G proteins; models, animal; raloxifene; rats; receptors, serotonin; tamoxifen

Abstract

Objectif

On pense qu'un déséquilibre au niveau de la neurotransmission sérotoninergique pourrait sous-tendre un grand nombre des troubles affectifs. C'est pourquoi les antidépresseurs et les neuroleptiques ciblent le récepteur de la sérotonine-1A (5-HT1A). On a signalé que les œstrogènes modulent la neurotransmission sérotoninergique. Nous avons donc étudié l'effet à long terme d'une ovariectomie sur la liaison spécifique des récepteurs de la 5-HT1A et sur l'activation de la protéine G dans le cerveau. Un traitement correctif faisant appel à l'œstradiol a été comparé avec des traitements fondés sur des modulateurs sélectifs des récepteurs des œstrogènes, le tamoxifène et le raloxifène.

Méthodes

Quatre mois après l'ovariectomie, des rats de Sprague-Dawley ont reçu pendant deux semaines, par voie sous-cutanée, soit le véhicule, de l'œstradiol-17β (80 μg/kg), soit du tamoxifène (1 mg/kg), ou encore du raloxifène (1 mg/kg). On a évalué par autoradiographie de coupes du cerveau la liaison spécifique des récepteurs de la 5-HT1A, au moyen du [3H]8-OH-DPAT, agoniste de la 5-HT1A. La stimulation des récepteurs de la 5-HT1A a été mesurée au moyen d'une autoradiographie de la liaison du [35S]GTPγS stimulée par le R-(+)-8-OH-DPAT.

Résultats

L'ovariectomie a entraÎné une réduction du poids de l'utérus qu'a corrigée le traitement par œstradiol; le tamoxifène et le raloxifène ont corrigé en partie cette réduction. Suite à la suppression des hormones et au traitement de substitution, la liaison spécifique du [3H]8-OH-DPAT est demeurée la même dans le cortex. Par ailleurs, l'ovariectomie a entraÎné une diminution de la liaison spécifique du [35S]GTPγS stimulée par le R-(+)-8-OH-DPAT dans le cortex; l'œstradiol a corrigé cet effet, mais ni le tamoxifène ni le raloxifène ne l'ont corrigé signicativement. En ce qui concerne l'hippocampe, l'ovariectomie n'a pas eu d'effet sur la liaison spécifique du [3H]8-OH-DPAT, tandis que seul le traitement par œstradiol-17β a entraÎné une diminution de cette liaison dans une sous-région du CA3. L'ovariectomie a entraÎné un accroissement de la liaison spécifique du [35S]GTPγS stimulée par le R-(+)-8-OH-DPAT dans le gyrus denté (mais pas au niveau du CA1 ou du CA3); l'œstradiol et le raloxifène ont corrigé cet effet, mais non le tamoxifène. Au niveau du noyau du raphé dorsal, l'ovariectomie a entraÎné un accroissement de la liaison spécifique du [3H]8-OH-DPAT ainsi que de la liaison spécifique du [35S]GTPγS stimulée par le R-(+)-8-OH-DPAT; l'œstradiol a corrigé cet accroissement, mais le tamoxifène et le raloxifène ne l'ont pas corrigé significativement.

Conclusions

On a observé que l'œstradiol entraÎne une stimulation générale de la liaison spécifique et du couplage des récepteurs de la 5-HT1A avec une diminution des récepteurs somatodendritiques du raphé et une augmentation des récepteurs postsynaptiques corticaux.

Introduction

Estrogens modulate brain activity from development to aging.1 Throughout a lifetime, estrogens influence mood, memory and mental state.2 A large body of data suggests that estrogens could be beneficial in the treatment of mental disorders.3 In support of this, the risk of depression has been found to be increased in women with low plasma levels of estradiol.4 In addition, estrogen replacement in patients with depression has been seen to mimic the effect of antidepressants.5

Menopause is associated with decreased ovarian hormones.6 Clinical studies have reported that menopausal women are more vulnerable to mental disorders.4 Experimentally, ovariectomized animals are used as models to investigate the impact of ovarian hormone loss.7 In the central nervous system, ovariectomy was reported to affect the serotonergic, glutamatergic and dopaminergic systems, that is, neurotransmitters implicated in mental disorders.3,7

A decrease in serotonergic function is associated with several mental disorders. The prefrontal cortex and hippocampus are affected in many cognitive and affective disorders.8 Many antidepressants and neuroleptics target the serotonin-1A (5-HT1A) receptor. In the dorsal raphe, the 5-HT1A receptor is an autoreceptor that exerts a negative feedback on the firing activity of 5-HT neurons.9 5-HT1A receptors are present in high density in limbic brain areas, notably, the hippocampus, lateral septum, cortical areas (particularly the prefrontal, cingulate and entorhinal cortex) and the mesencephalic raphe.10 The 5-HT1A receptor activates the Gi/o and Gz proteins family, transmitting inhibitory signals.10 In patients with depression, the 5-HT1A autoreceptor has been reported to be increased, thus, decreasing brain 5-HT function.11

It has been reported that estrogens modulate 5-HT1A receptors. Autoradiography with specific ligands for the 5-HT1A receptor or in situ hybridization of 5-HT1A receptor mRNA levels in the brains of ovariectomized rats have shown a decrease or no effect of short-term or long-term estradiol treatments in the cortex, the hippocampus and the raphe.12,13,14 An action of estrogen on lordosis induced by the 5-HT1A agonist 8-OH-DPAT is reported, without changes in 5-HT1A receptor density in the hypothalamus.15 Estradiol was thus hypothesized to act downstream from the receptor. 5-HT1A agonist–stimulated [35S]GTPγS-specific binding was used to investigate estradiol action on 5-HT1A receptor stimulation and as an indication of coupling of this receptor. This assay provides measures of the first step in the signal transduction cascade.16 In nonhuman primates, long-term estradiol treatment decreases 8-OH-DPAT-stimulated 5-HT1A receptors in the dorsal raphe.12 In ovariectomized rats, estradiol (in vivo and in vitro) was reported to rapidly decrease 8-OH-DPAT stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding in the cortex and hippocampus, whereas no effect was reported with long-term estradiol treatment.17,18,19

Estrogens modulate cellular functions through 2 estrogen receptors, ERα and ERβ.20,21 These receptors mediate principally genomic actions by activating transcription of target genes.22 Estrogens can also mediate nongenomic effects related to membrane action,1 and accumulating evidence supports the existence of a membrane estrogen receptor.23 In the brain, ERα and ERβ have a specific expression pattern.24,25 The mechanisms involved in estrogen's beneficial effects related to mental disorders remain to be understood.

Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) were developed to mimic estradiol's beneficial action in bone and the cardiovascular system without the increased risk of breast and uterine cancer.26 Tamoxifen, a first-generation SERM, is widely used in the treatment of breast cancer.27,28 Raloxifene, a second-generation SERM, is given to menopausal women to treat osteoporosis.27,28 Few studies are available of the actions of SERMs in the brain.3,29

The aim of the present study was to investigate the impact of long-term ovariectomy (4 months) on brain 5-HT1A receptor–specific binding using the agonist ligand [3H]8-OH-DPAT. An indication of coupling of brain 5-HT1A receptors with Gi proteins was assessed with R-(+)-8-OH-DPAT- stimulated [35S]GTPγS-specific binding. The effect of a correction treatment of 2 weeks with estradiol was compared with tamoxifen and raloxifene. This paradigm was designed to mimic postmenopausal hormonal changes and hormone replacement to maintain a tonic rather than a cyclic fluctuation of estrogens.

Methods

Adult, female Sprague–Dawley rats weighing about 250 g were purchased from Charles River Canada (St. Constant, Que.). The animals were housed 2 per cage in an environment that was light-controlled (12 h light per day, lights on at 7 am) and temperature-controlled (22°C–23°C). The animals had free access to rat food and water. The Laval University Animal Care Committee approved all the animal studies. All efforts were made to minimize the animals' suffering and to reduce the number of rats used.

The rats were divided into 5 groups of 10–17 animals. The first group comprised 12 intact control rats at random stages of the estrous cycle treated with vehicle (4% ethanol, 4% polyethylene glycol 600, 1% gelatin and 0.9% NaCl). The 4 other groups were rats that had been ovariectomized 4 months before and were treated with either vehicle (11 rats), 80 μg/kg 17β-estradiol (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.; 10 rats), 1 mg/kg tamoxifen citrate (Sigma, 10 rats) or 1 mg/kg raloxifene (17 rats). Raloxifene was extracted from pills (Evista; Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, Ind.) as previously described.30 The drug doses were the same as in our previous studies.31 The rats were ovariectomized under anesthesia with a 1.5% isoflurane–air mixture. Treatment began 4 months after ovariectomy, once daily for 14 days; 0.5 mL per rat was injected subcutaneously as suspension (in vehicle).

Animals were killed by decapitation, and their brains were rapidly removed, flash-frozen in isopentane over dry ice, individually wrapped in aluminum foil and kept at –80°C. The uteri were immediately removed at sacrifice, freed from connective and adipose tissue, and weighed. For cryosection, brains were immersed in Tissue-Tek (Miles, Inc., Elkhart, Ind.) at –20°C, mounted on cryostat chucks and cut into 20-μm coronal slices. Adjacent coronal slices were cut from the anterior region of the prefrontal cortex and cingulate cortex (bregma 4.2 to 3.7), the hippocampus (bregma –3.14 to –3.80), and dorsal raphe nucleus (bregma –7.04 to –7.64) according to the Paxinos and Watson atlas.32 The subregions CA1 stratum oriens, CA1 stratum radiatum, CA3 low subregion, CA3 high subregion (low and high denominations reflect the density of 5HT1A receptor–specific binding in the CA3 region) and the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus were quantified. Slices were thaw-mounted on pre-cleaned slides (Snowcoat X-tra; Surgipath, Richmond, Ill.) and vacuum desiccated at 4°C for 12 hours before storing at –80°C.

Autoradiography of 5-HT1A receptor–binding sites with [3H]8-OH-DPAT and of Gi protein–specific binding with [35S]GTPγS was performed, as previously described.33,34,35 Sections and calibrated [3H] standards for [3H]8-OH-DPAT binding and [14C] standards for [35S]GTPγS binding (Microscales; Amersham, Arlington Height, Ill.) were exposed for 4 weeks for [3H]8-OH-DPAT and 48 hours for [35S]GTPγS to Kodak BioMax MR film at room temperature. The autoradiograms were analyzed using the software package NIH Image 1.63 on a Power-Macintosh 7100 assisted videodensitometry (Sony camera XC-77).

The percentage of stimulation was determined as follows (Equation 1):

The experimental data were compared using 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using Statviews 4.51 for Macintosh Computer, followed by post hoc pairwise comparisons with a Fisher's probability of least significant difference test (PLSD). The results were considered statistically significant when p 0.05. Statistical comparisons of logarithms of uterine weights were used.

Results

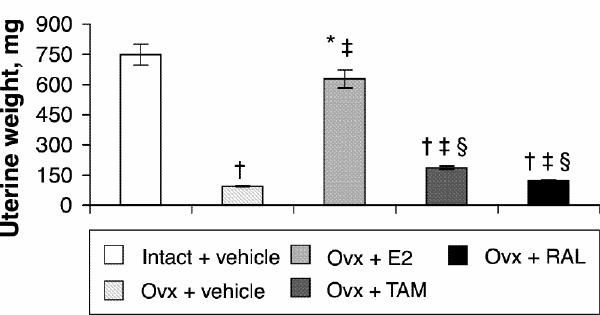

Four months after ovariectomy, uterine weights were decreased by 87% in ovariectomized rats compared with intact rats (Fig. 1). Correction therapy with estradiol for 2 weeks significantly stimulated uterine weight compared with that of ovariectomized rats, but partially (84%) compared with intact rats (Fig. 1). Tamoxifen and raloxifene induced a 49% and a 22% increase, respectively, compared with vehicle-treated ovariectomized rats and significantly less than estradiol treatment (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Uterine weight of intact rats treated with vehicle and ovariectomized (Ovx) rats treated with vehicle or a correction therapy of estradiol (E2), tamoxifen (TAM) or raloxifene (RAL) for 2 weeks. The results are mean weights (and the standard error of the mean [SEM]). *p < 0.05; †p < 0.001 v. intact rats, vehicle; ‡p < 0.001 v. ovariectomized rats, vehicle; §p < 0.001 v. ovariectomized rats, estradiol.

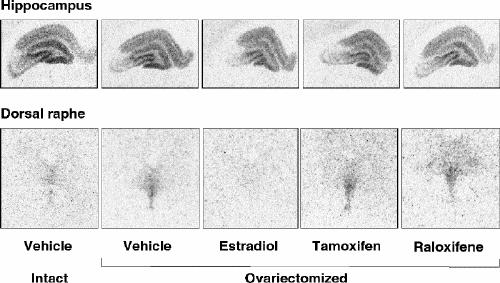

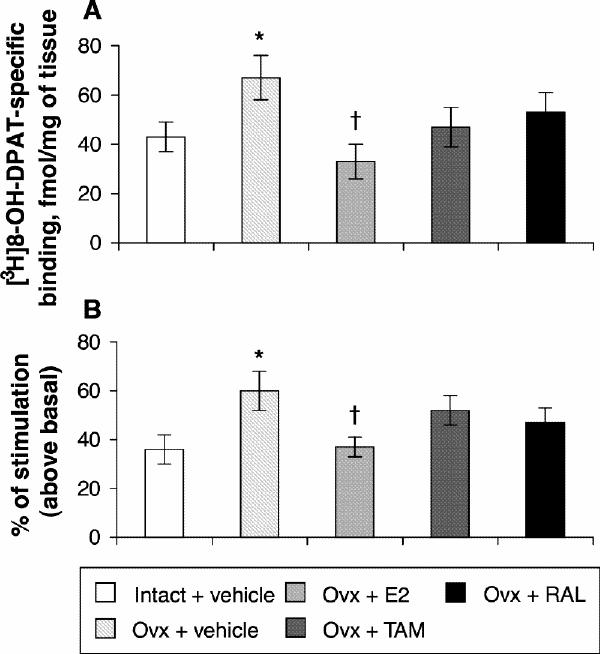

In the dorsal raphe, ovariectomy led to a 36% increase in [3H]8-OH-DPAT-specific binding that was corrected by estradiol (Fig. 2, Fig. 3A). Examples of autoradiograms of basal and stimulated [35S]GTPγS-specific binding in the dorsal raphe are shown in Figure 4. Ovariectomy increased R-(+)- 8-OH-DPAT-stimulated [35S]GTPγS-specific binding by 46% compared with that in intact rats (Fig. 3B). Estradiol decreased and restored binding to intact values. In rats treated with tamoxifen and raloxifene, dorsal raphe [3H]8-OH-DPAT-specific binding and R-(+)-8-OH-DPAT-stimulated [35S]GTPγS-specific binding were not significantly different from that in intact or ovariectomized rats (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2: Examples of autoradiograms of specific binding of [3H]8-OH-DPAT (2 nmol/L) in the hippocampus and dorsal raphe of intact rats and ovariectomized rats treated with vehicle or with a correction therapy of estradiol, tamoxifen or raloxifene for 2 weeks.

Fig. 3: Specific binding of [3H]8-OH-DPAT (2 nmol/L) (A) and specific binding of R-(+)-8-OH-DPAT-stimulated [35S]GTPγS (50 pmol/L) (B) in the dorsal raphe of intact rats treated with vehicle and ovariectomized rats treated with vehicle or a correction therapy of estradiol, tamoxifen or raloxifene for 2 weeks. Results in A are expressed as mean fmol/mg of tissue (and SEM). Results in B are expressed as a percentage of stimulated over basal specific binding (and SEM).*p < 0.05 v. intact rats, vehicle; †p < 0.05 v. ovariectomized rats, vehicle.

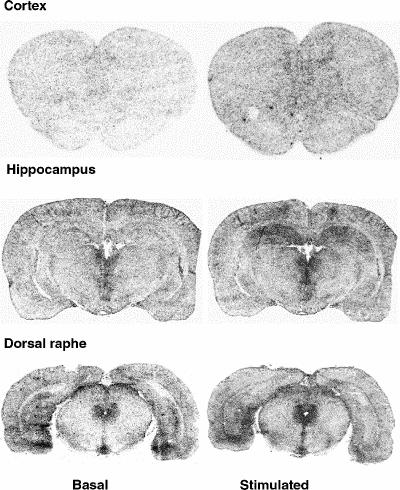

Fig. 4: Examples of autoradiograms of basal and R-(+)-8-OH-DPAT (1 μmol/L) stimulated [35S]GTPγS-specific binding. Coronal sections at the level of the cortex, hippocampus and dorsal raphe were incubated with [35S]GTPγS (50 pmol/L).

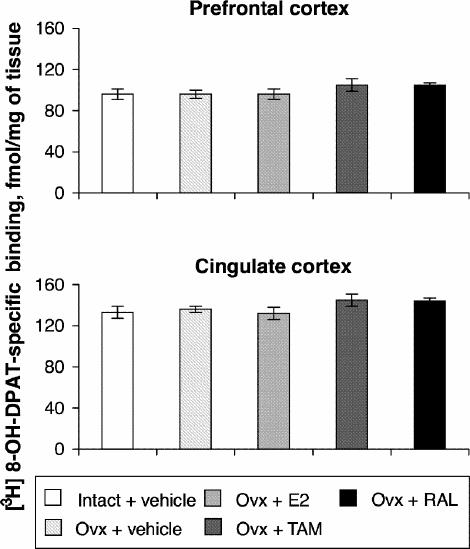

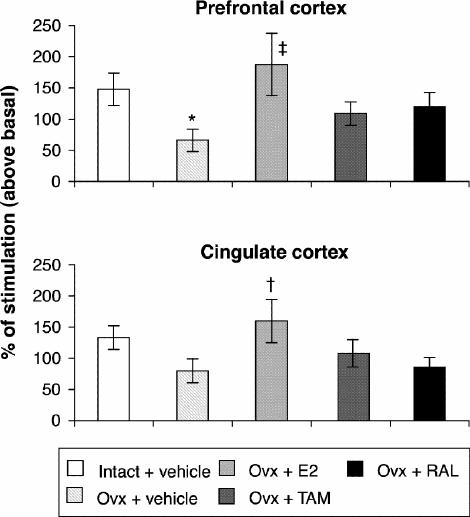

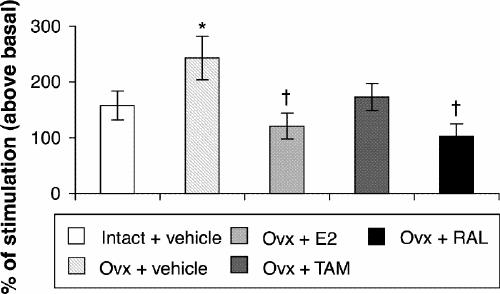

Ovariectomy and treatments left [3H]8-OH-DPAT-specific binding unchanged in the prefrontal and cingulate cortices (Fig. 5). Examples of autoradiograms of basal and stimulated [35S]GTPγS-specific binding in the cortex are shown in Figure 4. In cortical subregions, ovariectomy decreased R-(+)-8-OH-DPAT-stimulated [35S]GTPγS-specific binding by 55% and 40%, respectively, compared with intact rats (Fig. 6); this finding reached statistical significance in the prefrontal cortex. Estradiol treatment restored R-(+)-8-OH-DPAT-stimulated [35S]GTPγS-specific binding to intact values both in the prefrontal and cingulate cortices (Fig. 6). In rats treated with tamoxifen and raloxifene, cortical [3H]8-OH-DPAT-specific binding and R-(+)-8-OH-DPAT-stimulated [35S]GTPγS- specific binding were not significantly different from that in intact or vehicle-treated ovariectomized rats (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5: Specific binding of [3H]8-OH-DPAT (2 nmol/L) in the cortex of intact rats treated with vehicle and ovariectomized rats treated with vehicle or a correction therapy of estradiol, tamoxifen or raloxifene for 2 weeks. Results are expressed as mean fmol/mg of tissue (and SEM).

Fig. 6: R-(+)-8-OH-DPAT-stimulated [35S]GTPγS-specific binding (50 pmol/L) in the cortex of intact rats treated with vehicle and ovariectomized rats treated with vehicle or a correction therapy of estradiol, tamoxifen or raloxifene for 2 weeks. Results are expressed as percentage of stimulated over basal specific binding (and SEM). *p < 0.05 v. intact rats, vehicle; †p < 0.05, ‡p < 0.01 v. ovariectomized rats, vehicle.

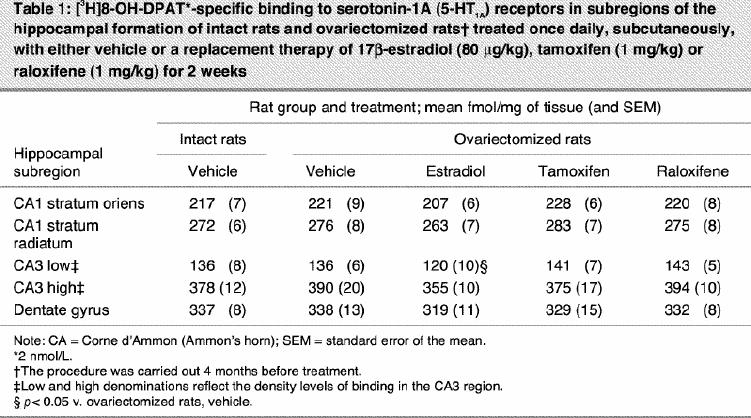

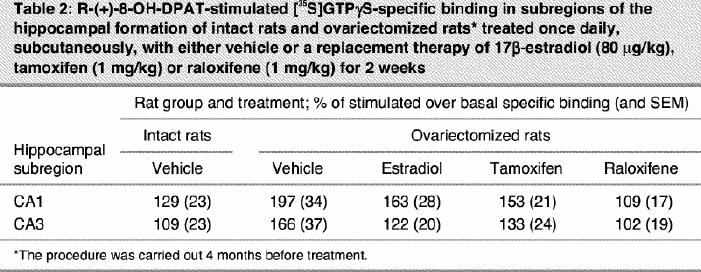

Ovariectomy and treatments left [3H]8-OH-DPAT-specific binding unchanged in the CA1, CA3 high subregion and the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus (Table 1). In the CA3 low subregion, estradiol treatment decreased this binding by 12% compared with that in intact and ovariectomized rats (Fig. 2, Table 1). Autoradiograms of basal and stimulated [35S]GTPγS-specific binding in the hippocampus are shown (Fig. 4). Ovariectomy and treatments did not alter R-(+)-8-OH-DPAT-stimulated [35S]GTPγS-specific binding in the CA1 and CA3 subregions (Table 2). In the dentate gyrus, ovariectomy increased R-(+)-8-OH-DPAT-stimulated [35S]GTPγS-specific binding by 56% compared with that in intact rats; this was corrected with estradiol and raloxifene treatments, but not with tamoxifen (Fig. 7).

Table 1

Table 2

Fig. 7: R-(+)-8-OH-DPAT-stimulated [35S]GTPγS-specific binding (50 pmol/L) in the dentate gyrus of intact rats treated with vehicle and ovariectomized rats treated with vehicle or a correction therapy of estradiol, tamoxifen or raloxifene for 2 weeks. Results are expressed as a percentage of stimulated over basal specific binding (and SEM). *p < 0.05 v. intact rats, vehicle; †p < 0.01 v. ovariectomized rats, vehicle.

Discussion

Our results showed that ovariectomy and estradiol differentially affect [3H]8-OH-DPAT-specific binding and R-(+)-8-OH-DPAT-stimulated [35S]GTPγS-specific binding in the prefrontal and cingulate cortices and the hippocampus compared with the dorsal raphe nucleus. [35S]GTPγS-binding autoradiography used in the present experiments has been called “functional autoradiography” and has the advantage of providing functional information in an anatomical context.16 The essence of the method is to visualize agonist-activated receptors by labelling receptor-coupled G-proteins with a radiolabelled analogue of guanosine triphosphate (GTP). This assay measures the first step in the signal transduction cascade and is an indication of coupling to the receptor.

In the dorsal raphe, 4 months after ovariectomy, 5-HT1A receptor density and agonist stimulation were increased compared with those in intact rats. This suggests that ovariectomy, modelling hormonal withdrawal in menopause, leads to a state of 5-HT1A inhibitory autoreceptor hyperactivity in the dorsal raphe. This receptor decreases neuronal firing and serotonin release. The risk of depression has been found to be increased in women with low plasma levels of estradiol.4 In addition, patients with depression have an increase of [3H]8-OH-DPAT-specific binding to 5-HT1A receptors in the dorsal raphe.11

This 5-HT1A autoreceptor hyperactivity was corrected (decreased to intact rat values) by an estradiol treatment of 2 weeks but was not corrected significantly with tamoxifen or raloxifene. This estrogenic effect has similarities to the effects of long-term treatment with the antidepressants fluoxetine, clorgyline and ipsapirone, as well as the 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist buspirone, which also decrease dorsal raphe 5-HT1A-receptor-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding.36 Hence, these data suggest that estrogens could be a beneficial adjunct to antidepressant treatment in postmenopausal women with mood disorders, by decreasing the 5-HT1A autoreceptor–specific second messenger pathway.

In the dorsal raphe, the effects of hormonal status on receptor density and coupling were similar, suggesting that a change in coupling reflects a change in receptor availability. In the other brain regions investigated, this was not the case.

In nonhuman primates, long-term estradiol treatment was also reported to decrease 5-HT1A receptor density and stimulation.12 Hence, these results in ovariectomized monkeys and rats could explain why estradiol is seen to improve the mental state of postmenopausal women by increasing 5-HT firing, as antidepressants do.5 The decrease in 5-HT1A stimulation could be achieved by a decrease in receptor density and by the modulation of Gi protein expression. Indeed, in nonhuman primates, estradiol was reported to decrease the Gαi3 subtype in the midbrain.12 Fluoxetine was also reported to decrease Gi2 and Go subunit protein expression in the rat midbrain.37 In the dorsal raphe nucleus, ERβ is expressed in 5-HT neurons, whereas ERα is expressed in non-5-HT neurons.38 It is likely that ERβ mediates the estradiol decrease in 5-HT1A receptor density and coupling. Rats treated with tamoxifen and raloxifene had R-(+)-8-OH-DPAT-stimulated GTPγS binding in the dorsal raphe, which was neither different from that in intact nor ovariectomized rats, suggesting that these drugs have no estrogenic agonist activity or weak estrogenic agonist activity on the coupling to this receptor. In the raphe of ovariectomized macaques, treatment for 30 days with estradiol, raloxifene or arzoxifene left 5-HT1A mRNA unchanged, whereas tryptophan hydroxylase mRNA was increased and serotonin transporter mRNA decreased.39 Hence, SERMs are likely candidates to modulate serotonin neurons at different steps of neurotransmission.

No effect of hormonal withdrawal and replacement was measured on the 5-HT1A receptor labelled with [3H]8-OH-DPAT in the prefrontal and cingulate cortices. We observed similar results in short-term ovariectomized rats.40

In the prefrontal and cingulate cortices, long-term ovariectomy decreased R-(+)-8-OH-DPAT stimulated [35S]GTPγS-specific binding. This result suggests that hormonal withdrawal can reduce 5-HT1A signalling. Many affective disorders are linked to a hypofunction of the serotonergic system in the cortex.41 This observation may be implicated in menopausal women's vulnerability to mental disorders.4

This is the first report to show that estradiol treatment for 2 weeks increases R-(+)-8-OH-DPAT-stimulated [35S]GTPγS-specific binding in the prefrontal and cingulate cortices and counteracts the effect of ovariectomy. Mize and Alper17 reported that a 14-day estradiol treatment of ovariectomized rats left 8-OH-DPAT-stimulated GTPγS binding unchanged. However, they used a lower dose of estradiol and membrane from the anterior cortex, which could have diluted an effect concentrated in the anterior prefrontal and cingulate cortices.17 In addition, in the present experiments, estradiol treatment was started 4 months after ovariectomy, whereas it was started 2 weeks after ovariectomy in the study by Mize and Alper.17 Short-term and in-vitro estradiol treatment was shown to decrease the percentage of 5-HT1A receptor stimulation in the anterior cortex.17,19 Long-term estradiol treatment could modulate 5-HT1A receptor functionality. Indeed, it has been suggested that in-vitro estradiol, by activating protein kinase A and C, may lead to 5-HT1A phosphorylation and uncoupling.18 These effects observed with short-term estradiol treatments were mimicked by the membrane-impermeable bovine serum albumin–estradiol (E2-BSA), reinforcing the idea of the involvement of a membrane estrogen receptor.19

As in the raphe, rats treated with tamoxifen and raloxifene had cortical R-(+)-8-OH-DPAT-stimulated GTPγS binding that was neither different from that in intact nor ovariectomized rats, suggesting that these drugs have no estrogenic agonist activity or weak estrogenic agonist activity on the coupling to this receptor. Mize et al19 previously reported that tamoxifen, in a dose-dependent manner, decreased the percentage of stimulation of 5-HT1A receptors. This decrease was observed with a high dose of tamoxifen (10-6 mol/L),19 which is unlikely to have been reached in our in-vivo experiment using 1 mg/kg subcutaneously of tamoxifen. In the cortex, ERα and ERβ are expressed, with a higher proportion of ERβ;25,42,43 therefore, the estrogenic effects observed could involve either of these receptors.

In the hippocampus, long-term ovariectomy had no effect on [3H]8-OH-DPAT-specific binding; estradiol treatment decreased this binding in the CA3 low subregion of the hippocampus without affecting the other subregions. These results are consistent with a previous report concerning long-term treatment of rats with estradiol,14 whereas no effect of ovariectomy and estradiol treatment was observed on 5-HT1A receptors in the hippocampus in recently ovariectomized rats.40 Long-term estradiol treatment induced a decrease in 5-HT1A receptor–specific binding and mRNA in the CA3, and single administration of estradiol had no effect.13,14 This could involve a downregulation by estradiol of 5-HT1A receptor gene transcription. The 5-HT1A receptor gene contains an Sp1 sequence where estradiol could interact.44,45 Tamoxifen and raloxifene did not mimic the estradiol effect in the CA3, indicating that they have no estrogenic properties on 5-HT1A receptor–specific binding. ERα and ERβ are both expressed in the subregions of the hippocampus;46 however, on the Sp1 promoter, ERβ was reported to be ineffective.47,48 It seems likely that estradiol decreased 5-HT1A receptor expression in the hippocampus through an ERα pathway.

Ovariectomy increased R-(+)-8-OH-DPAT-stimulated GTPγS binding only in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. This increase was corrected by estradiol. A previous study reported no effect of long-term estradiol treatment in the whole hippocampus.17 Similarly, if our results for R-(+)-8-OH-DPAT-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding are quantified for the whole hippocampus, no effect of ovariectomy and estradiol treatment is observed, masking the subregional effect reported here. Short-term administration of estradiol has been reported to decrease 5-HT1A receptor coupling.17 It was proposed that this effect involved an increase of protein kinase A and protein kinase C activities.18 In the hippocampus, estradiol was previously shown to enhance the 5-HT1A signal in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells by c-fos activation and GAD65 inhibition.49,50,51,52

Long-term treatment with fluoxetine has been reported to leave 5-HT1A receptor–specific binding unchanged in all the brain regions investigated, including the raphe, the cortex and the hippocampus.53,54 Long-term treatment with antidepressants like fluoxetine and imipramine, however, induces an increase in agonist-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in the hippocampus of ovariectomized rats, whereas clorgyline, ipsapirone and buspirone did not change this binding.36,55 More specifically, fluoxetine increases or leaves unchanged 5-HT1A receptor stimulation in the CA1 and dentate gyrus.53,54 Hence, in the hippocampus, 5-HT1A receptor stimulation is either not modulated or is differently modulated in some subregions by estradiol and antidepressants. Raloxifene, but not tamoxifen, decreased the percentage of stimulation. This is unlikely to be because of their absence or a concentration that is too low in the brain, because both tamoxifen and raloxifene were previously reported to have estrogenic activity and mimic the estradiol effect on N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and 2-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionate (AMPA) receptors.56,57,58

In conclusion, the present data show regional specific changes in 5-HT1A receptor stimulation by long-term ovariectomy that are corrected with estradiol treatment. The receptor coupling changes observed with gonadal hormone withdrawal and replacement are not always associated with changes in 5-HT1A receptor–specific binding. The estradiol effect on 5-HT1A receptors in the brain regions investigated, decreasing raphe somatodendritic and increasing cortical postsynaptic receptors, is generally either only modestly reproduced or not reproduced with tamoxifen and raloxifene treatments. Interestingly, in the dorsal raphe, estradiol decreases 5-HT1A receptor coupling, as do antidepressants.36,55

Acknowledgments

A grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) to Dr. Di Paolo supported this research. Ms. Le Saux holds a studentship from the Fondation de l'Universtité Laval.

Footnotes

2003 CCNP Heinz Lehmann Award Paper

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Thérèse Di Paolo, Molecular Endocrinology and Oncology Research Center, Laval University Medical Centre (CHUL), 2705 Laurier Blvd., Sainte-Foy QC G1V 4G2; fax 418 654-2761; therese.dipaolo@crchul.ulaval.ca

Submitted Dec. 29, 2003; Revised Apr. 1, 2004; Accepted Apr. 6, 2004

References

- 1.McEwen BS, Alves SE. Estrogen actions in the central nervous system. Endocr Rev 1999;20(3):279-307. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.McEwen BS. Clinical review 108: the molecular and neuroanatomical basis for estrogen effects in the central nervous system. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999;84(6):1790-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Cyr M, Calon F, Morissette M, Grandbois M, Di Paolo T, Callier S. Drugs with estrogen-like potency and brain activity: potential therapeutic application for the CNS. Curr Pharm Des 2000; 6 (12): 1287-312. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Buckwalter JG, Stanczyk FZ, McCleary CA, Bluestein BW, Buckwalter DK, Rankin KP, et al. Pregnancy, the postpartum, and steroid hormones: effects on cognition and mood. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1999;24(1):69-84. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Panay N, Studd JW. The psychotherapeutic effects of estrogens. Gynecol Endocrinol 1998;12(5):353-65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Zapantis G, Santoro N. The menopausal transition: characteristics and management. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;17(1): 33-52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Bosse R, Di Paolo T. The modulation of brain dopamine and GABAA receptors by estradiol: a clue for CNS changes occurring at menopause. Cell Mol Neurobiol 1996;16(2):199-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Benes FM. Emerging principles of altered neural circuitry in schizophrenia. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 2000;31(2-3):251-69. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Blier P, Lista A, De Montigny C. Differential properties of pre- and postsynaptic 5-hydroxytryptamine1A receptors in the dorsal raphe and hippocampus: II. Effect of pertussis and cholera toxins. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1993;265(1):16-23. [PubMed]

- 10.Barnes NM, Sharp T. A review of central 5-HT receptors and their function. Neuropharmacology 1999;38(8):1083-152. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Stockmeier CA, Shapiro LA, Dilley GE, Kolli TN, Friedman L, Rajkowska G. Increase in serotonin-1A autoreceptors in the midbrain of suicide victims with major depression-postmortem evidence for decreased serotonin activity. J Neurosci 1998;18(18):7394-401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Lu NZ, Bethea CL. Ovarian steroid regulation of 5-HT1A receptor binding and G protein activation in female monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology 2002;27(1):12-24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Osterlund MK, Hurd YL. Acute 17 beta-estradiol treatment down-regulates serotonin 5HT1A receptor mRNA expression in the limbic system of female rats. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 1998;55(1):169-72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Osterlund MK, Halldin C, Hurd YL. Effects of chronic 17beta-estradiol treatment on the serotonin 5-HT(1A) receptor mRNA and binding levels in the rat brain. Synapse 2000;35(1):39-44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Jackson A, Etgen AM. Estrogen modulates 5-HT(1A) agonist inhibition of lordosis behavior but not binding of [(3)H]-8-OH-DPAT. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2001;68(2):221-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Sovago J, Dupuis DS, Gulyas B, Hall H. An overview on functional receptor autoradiography using [35S]GTPgammaS. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 2001;38(1-2):149-64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Mize AL, Alper RH. Acute and long-term effects of 17beta- estradiol on G(i/o) coupled neurotransmitter receptor function in the female rat brain as assessed by agonist-stimulated [35S]GTPgammaS binding. Brain Res 2000;859(2):326-33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Mize AL, Alper RH. Rapid uncoupling of serotonin-1A receptors in rat hippocampus by 17beta-estradiol in vitro requires protein kinases A and C. Neuroendocrinology 2002;76(6):339-47. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Mize AL, Young LJ, Alper RH. Uncoupling of 5-HT1A receptors in the brain by estrogens: regional variations in antagonism by ICI 182,780. Neuropharmacology 2003;44(5):584-91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Giguere V, Yang N, Segui P, Evans RM. Identification of a new class of steroid hormone receptors. Nature 1988;331(6151):91-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Kuiper GG, Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA. Cloning of a novel receptor expressed in rat prostate and ovary. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996;93(12):5925-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Sanchez R, Nguyen D, Rocha W, White JH, Mader S. Diversity in the mechanisms of gene regulation by estrogen receptors. Bioessays 2002; 24 (3):244-54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Belcher SM, Zsarnovszky A. Estrogenic actions in the brain: estrogen, phytoestrogens, and rapid intracellular signaling mechanisms. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2001;299(2):408-14. [PubMed]

- 24.Laflamme N, Nappi RE, Drolet G, Labrie C, Rivest S. Expression and neuropeptidergic characterization of estrogen receptors (ERalpha and ERbeta) throughout the rat brain: anatomical evidence of distinct roles of each subtype. J Neurobiol 1998;36(3):357-78. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Shughrue PJ, Lane MV, Merchenthaler I. Comparative distribution of estrogen receptor-alpha and -beta mRNA in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol 1997;388(4):507-25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Sismondi P, Biglia N, Giai M, Ponzone R, Roagna R, Sgro L, et al. HRT, breast and endometrial cancers: strategies and intervention options. Maturitas 1999;32 (3): 131-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Sato M, Rippy MK, Bryant HU. Raloxifene, tamoxifen, nafoxidine, or estrogen effects on reproductive and nonreproductive tissues in ovariectomized rats. FASEB J 1996;10(8):905-12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Grese TA, Dodge JA. Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs). Curr Pharm Des 1998;4(1):71-92. [PubMed]

- 29.Dhandapani KM, Brann DW. Protective effects of estrogen and selective estrogen receptor modulators in the brain. Biol Reprod 2002; 67 (5):1379-85. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Jones CD, Jevnikar MG, Pike AJ, Peters MK, Black LJ, Thompson AR, et al. Antiestrogens. 2. Structure-activity studies in a series of 3-aroyl-2-arylbenzo[b]thiophene derivatives leading to [6- hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)benzo[b]thien-3-yl] [4-[2-(1-piperidinyl)ethoxy]-phenyl]methanone hydrochloride (LY156758), a remarkably effective estrogen antagonist with only minimal intrinsic estrogenicity. J Med Chem 1984;27(8):1057-66. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Cyr M, Landry M, Di Paolo T. Modulation by estrogen-receptor directed drugs of 5-hydroxytryptamine-2A receptors in rat brain. Neuropsychopharmacology 2000;23(1):69-78. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. 4th ed. San Diego: Academic Press; 1998.

- 33.Bonhomme N, Cador M, Stinus L, Le Moal M, Spampinato U. Short and long-term changes in dopamine and serotonin receptor binding sites in amphetamine-sensitized rats: a quantitative autoradiographic study. Brain Res 1995;675(1-2):215-23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Waeber C, Moskowitz MA. 5-Hydroxytryptamine1A and 5- hydroxytryptamine1B receptors stimulate [35S]guanosine-5'-O-(3-thio)triphosphate binding to rodent brain sections as visualized by in vitro autoradiography. Mol Pharmacol 1997;52(4):623-31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Meller E, Li H, Carr KD, Hiller JM. 5-Hydroxytryptamine(1A) receptor-stimulated [(35)S]GTPgammaS binding in rat brain: absence of regional differences in coupling efficiency. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2000;292(2):684-91. [PubMed]

- 36.Sim-Selley LJ, Vogt LJ, Xiao R, Childers SR, Selley DE. Region-specific changes in 5-HT(1A) receptor-activated G-proteins in rat brain following chronic buspirone. Eur J Pharmacol 2000;389(2-3):147-53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Li Q, Muma NA, van de Kar LD. Chronic fluoxetine induces a gradual desensitization of 5-HT1A receptors: reductions in hypothalamic and midbrain Gi and G(o) proteins and in neuroendocrine responses to a 5-HT1A agonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1996; 279 (2):1035-42. [PubMed]

- 38.Bethea CL, Lu NZ, Gundlah C, Streicher JM. Diverse actions of ovarian steroids in the serotonin neural system. Front Neuroendocrinol 2002;23(1):41-100. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Bethea CL, Mirkes SJ, Su A, Michelson D. Effects of oral estrogen, raloxifene and arzoxifene on gene expression in serotonin neurons of macaques. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2002;27(4):431-45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Landry M, Di Paolo T. Effect of chronic estradiol, tamoxifen or raloxifene treatment on serotonin 5-HT1A receptor. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 2003;112(1-2):82-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Mann JJ. Role of the serotonergic system in the pathogenesis of major depression and suicidal behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology 1999; 21 (2 Suppl):99S-105S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Butler JA, Kallo I, Sjoberg M, Coen CW. Evidence for extensive distribution of oestrogen receptor alpha-immunoreactivity in the cerebral cortex of adult rats. J Neuroendocrinol 1999;11(5):325-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Shughrue PJ, Lane MV, Merchenthaler I. Biologically active estrogen receptor-beta: evidence from in vivo autoradiographic studies with estrogen receptor alpha-knockout mice. Endocrinology 1999; 140 (6):2613-20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Parks CL, Shenk T. The serotonin 1a receptor gene contains a TATA-less promoter that responds to MAZ and Sp1. J Biol Chem 1996; 271(8):4417-30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Porter W, Saville B, Hoivik D, Safe S. Functional synergy between the transcription factor Sp1 and the estrogen receptor. Mol Endocrinol 1997;11(11):1569-80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Shughrue PJ, Merchenthaler I. Evidence for novel estrogen binding sites in the rat hippocampus. Neuroscience 2000;99(4):605-12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Safe S. Transcriptional activation of genes by 17 beta-estradiol through estrogen receptor-Sp1 interactions. Vitam Horm 2001; 62: 231-52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Saville B, Wormke M, Wang F, Nguyen T, Enmark E, Kuiper G, et al. Ligand-, cell-, and estrogen receptor subtype (alpha/beta)-dependent activation at GC-rich (Sp1) promoter elements. J Biol Chem 2000; 275 (8):5379-87. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Clarke WP, Goldfarb J. Estrogen enhances a 5-HT1A response in hippocampal slices from female rats. Eur J Pharmacol 1989; 160 (1): 195-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Clarke WP, Maayani S. Estrogen effects on 5-HT1A receptors in hippocampal membranes from ovariectomized rats: functional and binding studies. Brain Res 1990;518(1-2):287-91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Beck SG, Clarke WP, Goldfarb J. Chronic estrogen effects on 5- hydroxytryptamine-mediated responses in hippocampal pyramidal cells of female rats. Neurosci Lett 1989;106(1-2):181-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Rudick CN, Woolley CS. Selective estrogen receptor modulators regulate phasic activation of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells by estrogen. Endocrinology 2003;144(1):179-87. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Elena Castro M, Diaz A, del Olmo E, Pazos A. Chronic fluoxetine induces opposite changes in G protein coupling at pre and postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptors in rat brain. Neuropharmacology 2003;44 (1): 93-101. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Hensler JG. Differential regulation of 5-HT1A receptor-G protein interactions in brain following chronic antidepressant administration. Neuropsychopharmacology 2002;26(5):565-73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Shen C, Li H, Meller E. Repeated treatment with antidepressants differentially alters 5-HT(1A) agonist-stimulated [(35)S]GTPgammaS binding in rat brain regions. Neuropharmacology 2002;42 (8): 1031-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Cyr M, Ghribi O, Thibault C, Morissette M, Landry M, Di Paolo T. Ovarian steroids and selective estrogen receptor modulators activity on rat brain NMDA and AMPA receptors. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 2001;37(1-3):153-61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Cyr M, Ghribi O, Di Paolo T. Regional and selective effects of oestradiol and progesterone on NMDA and AMPA receptors in the rat brain. J Neuroendocrinol 2000;12(5):445-52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Cyr M, Thibault C, Morissette M, Landry M, Di Paolo T. Estrogen-like activity of tamoxifen and raloxifene on NMDA receptor binding and expression of its subunits in rat brain. Neuropsychopharmacology 2001;25(2):242-57. [DOI] [PubMed]