Abstract

Therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is associated with enteropathy in humans and experimental animals, a cause of considerable morbidity. Unlike foregut NSAID-associated mucosal lesions, most treatments for this condition are of little efficacy. We propose that the endogenously-released intestinotrophic hormone glucagon-like peptide-2 (GLP-2) prevents the development of NSAID-induced enteropathy. Since the short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) receptor FFA3 is expressed on enteroendocrine L cells and on enteric nerves in the gastrointestinal tract, we further hypothesized that activation of FFA3 on L cells protects the mucosa from injury via GLP-2 release with enhanced duodenal HCO3− secretion. We thus investigated the effects of synthetic selective FFA3 agonists with consequent GLP-2 release on NSAID-induced enteropathy.

We measured duodenal HCO3− secretion in isoflurane anesthetized rats in a duodenal loop perfused with the selective FFA3 agonists MQC or AR420626 (AR) while measuring released GLP-2 in the portal vein (PV). Intestinal injury was produced by indomethacin (IND, 10 mg/kg, sc) with or without MQC (1 – 10 mg/kg, ig) or AR (0.01 – 0.1 mg/kg, ig or ip) treatment.

Luminal perfusion with MQC or AR (0.1 – 10 μM) dose-dependently augmented duodenal HCO3− secretion accompanied by increased GLP-2 concentrations in the PV. The effect of FFA3 agonists was inhibited by co-perfusion of the selective FFA3 antagonist CF3-MQC (30 μM). AR-induced augmented HCO3− secretion was reduced by iv injection of the GLP-2 receptor antagonist GLP-2(3-33) (3 nmol/kg), or by pretreatment with the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) inhibitor CFTRinh-172 (1 mg/kg, ip). IND-induced small intestinal ulcers were dose-dependently inhibited by intragastric administration of MQC or AR. GLP-2(3-33) (1 mg/kg, ip) or CF3-MQC (1 mg/kg, ig) reversed AR-associated reduction of IND-induced enteropathy. In contrast, ip injection of AR had no effect on enteropathy.

These results suggest that luminal FFA3 activation enhances mucosal defenses and prevents NSAID-induced enteropathy via the GLP-2 pathway. The selective FFA3 agonist may be a potential therapeutic candidate for NSAID-induced enteropathy.

Introduction

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) that inhibit cyclooxygenase (COX) with consequent inhibition of prostaglandin (PG) synthesis are often the cause of erosive mucosal gastroenteropathy and gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. NSAID use, etiological in 10% of subjects diagnosed with obscure GI bleeding [1] is associated with a 50% prevalence of small intestinal mucosal injury [2], increasing to 70% in arthritis patients [3]. Since the mechanism of and treatment for this increasingly recognized NSAID-related morbidity are at present unclear [4], it is important to further explore the mechanism of NSAID-related mucosal injury so as to inform therapeutics designed to prevent injury and accelerate mucosal healing.

The pathogenesis of NSAID-induced enteropathy includes: 1) direct cytotoxicity of NSAIDs [5] since most NSAIDs such as indomethacin (IND), are continually present in the intestinal lumen up to 24 hrs after ingestion due to their enterohepatic circulation [6], sparing the colon; 2) the reduction of mesenteric blood flow by COX inhibition in the small intestine [7,8]; 3) the reduction of epithelial anion and mucus secretion by COX inhibition [9,10]; 4) hypermotility due to the reduction of PG synthesis, since PG inhibits intestinal motility [11]; 5) transmucosal movement of luminal bacteria (translocation) or bacteria-derived products such as endotoxin, releasing pro-inflammatory mediators in the submucosa, since antibiotic treatment reduces NSAID-induced small intestinal injury [12,13]; and/or 6) dysbiosis (alteration of the gut microbiome) [14], which generates toxic metabolites such as secondary bile acids [15].

Due to these multiple mechanisms, NSAID-induced enteropathy has been treated experimentally and clinically with oxygen radical scavengers, exogenous PGE2, agonists of the E-type PG receptor EP4, atropine, and antibiotics [4]. We have reported that activation of the glucagon-like peptide-2 (GLP-2) pathway prevents ulcer formation and accelerates ulcer healing in IND-induced enteropathy [16], since GLP-2 not only has an intestinotrophic effect, but also increases mesenteric blood flow and augments the rate of mucosal protective HCO3− secretion via the vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and nitric oxide (NO) pathways [17,18]. Although exogenous GLP-2 increases overall survival in a mouse model of IND-induced enteropathy [19], we have confirmed that exogenous GLP-2 treatment prevents ulcer formation and accelerates ulcer healing of IND-induced enteropathy in a rat model [16]. Furthermore, a dipeptidyl protease-4 (DPP4) inhibitor, which stabilizes released GLP-2, reduces IND-induced enteropathy and promotes ulcer healing [16]. Since GLP-2 release is associated with luminal nutrient sensing [20], we propose that luminal nutrient-induced GLP-2 release combined with DPP4 inhibition will be a useful therapeutic for the treatment of NSAID-induced enteropathy.

The short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) receptors are nutrient-sensing G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) termed free fatty acid receptor 2 (FFA2) and 3 (FFA3). We have reported that in rat duodenum FFA2 is expressed in serotonin- (5-hydroxytryptamine; 5-HT) containing enterochromaffin (EC) cells, whereas FFA3 is present in enteroendocrine L cells containing GLP-1 and GLP-2 [21]. Luminal perfusion of the selective FFA2 agonist phenylacetamide-1 (PA1) dose-dependently augments the rate of duodenal HCO3− secretion via activation of the 5-HT4 receptor and muscarinic M1 and M3 receptors, but not via 5-HT3 receptor activation [21]. Acetate, a ligand for both FFA2 and FFA3, augments the rate of duodenal HCO3− secretion and increases GLP-2 release, suggesting that FFA3 activation increases GLP-2 release. Nevertheless, the lack of available selective FFA3 agonists in the past has limited efforts to clarify the contribution of FFA3 activation towards GLP-2 release in vivo. Furthermore, it is uncertain whether the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), a major HCO3− secretory pathway in the duodenum [22], is involved in GLP-2-related HCO3− secretion.

Here, we examined the effect of selective FFA3 agonists on duodenal HCO3− secretion and IND-induced enteropathy, reporting that FFA3 activation is associated with GLP-2 release, an increased rate of duodenal protective HCO3− secretion via CFTR, and the prevention of IND-induced enteropathy via the GLP-2 pathway.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 200–250 g (Harlan, San Diego, CA, USA) were fed a pellet diet and water ad libitum. All studies were performed with approval of the Veterans Affairs Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Rats were fasted overnight with free access to water before the experiments. Animals were euthanized by terminal exsanguination under deep isoflurane anesthesia, followed by thoracotomy.

Chemicals

N-[2-methylphenyl]-[4-furan-3-yl]-2-methyl-5-oxo-1,4,5,6,7,8-hexahydroquinoline-3-carboxamide (MQC) and N-(2-methylphenyl)-4-[5-(2-trifluoromethoxy-phenyl)-furan-2-yl)-2-methyl-5-oxo-1,4,5,6,7,8- hexahydro-quinoline-3-carboxamide (CF3-MQC), according to the structures reported previously [23], were synthesized, purified and verified in Laboratory of Organic Chemistry, School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Shizuoka, Japan. CFTRinh-172, the selective inhibitor for cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), was synthesized by Dr. Samedy Ouk in the Department of Chemistry, UCLA [24]. AR420626 was obtained from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Rat GLP-2 was obtained from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO). Rat GLP-2(3-33) was synthesized by Bachem Americas, Inc. (Torrance, CA). Indomethacin (IND) and other chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO). IND was dissolved in 100% ethanol. MQC, CF3-MQC, AR420626 and CFTRinh-172 were dissolved in DMSO. 0.1% DMSO in Krebs buffer or 3% in saline was used as vehicle control for the perfusion or intestinal injury experiments, respectively, as described below.

Duodenal loop perfusion in vivo

Duodenal loops and PV cannulations were prepared as previously reported [21,25]. Briefly, under isoflurane anesthesia (2%), the PV was cannulated with a polyethylene (PE)-50 tube attached with 23-G needle and fixed by methylacrylate adhesive at the insertion site. A PE tube (5 mm diameter) was inserted from the incision of the forestomach through the pyloric ring, where it was sutured in place. Another PE tube was inserted from the distal duodenum, creating 2-cm duodenal loop. The pancreaticobiliary duct was ligated, followed by duct cannulation with a PE-10 tube with attached 30-G needle in order to avoid contaminating the duodenal lumen with pancreatic and biliary secretions. The effluent tube was connected to flow-through pH and CO2 electrodes. The loop was perfused with O2-bubbled normal saline pH 7 at 1 ml/min by a peristaltic pump. After stabilization for ~ 30 min, time was set as t = 0 min. The loop was perfused with saline from t = 0 to t = 10 min, followed by the perfusion of pH 7 Krebs buffer with or without MQC or AR420626 (0.1 – 10 μM), or CF3-MQC (30 μM) from t = 10 to t = 35 min. Some animals were bolus iv injected with the GLP-2 receptor antagonist GLP-2(3-33) (3 nmol/kg) at t = 10 min as previously described [18]. Some animals were pretreated with CFTRinh-172 (1 mg/kg, ip) 1 hr before the experiment [24]. pH and CO2 electrode measurement was recorded every 5 min to calculate total CO2 output as previously described [26]. PV blood (200 μl) was collected at t = 10, 15, 20 and 35 min, followed by infusion of equal volume of saline immediately after each PV blood withdrawal.

GLP-2 measurement in PV plasma

After centrifugation at 5,000x g for 5 min, PV plasma was kept at −80 °C until use. GLP-2 content in PV plasma was measured using a GLP-2 ELISA kit (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Burlingame, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

IND-Induced Intestinal Injury

IND-induced small intestinal injury was induced as previously described [16]. IND (10 mg/kg) was subcutaneously injected under brief isoflurane anesthesia (4 %).

PV and arterial blood were collected under isoflurane anesthesia, followed by euthanasia by terminal exsanguination 24 hrs after IND treatment. The GI tract from the stomach to terminal ileum was removed and longitudinally opened along the anti-mesenteric curvature, since IND-induced intestinal ulcers are principally localized to the mesenteric curvature. After carefully removing the luminal contents and gently rinsing the mucosa in normal saline, the small intestine was cut into ~ 10-cm segments. The gastric antrum was defined as segment 0, the duodenum as segment 1, the jejunum as segments 2 and 3, and the ileum as segments 4–7. Observed ulcers were typically circular and linearly arrayed. The diameter of each ulcer was macroscopically measured with the cumulative ulcer length of all ulcers in each segment calculated. Total ulcer length (mm) was defined by the sum of overall ulcer length in each segment.

Drug treatment

The following drugs were given intragastrically (ig) or intraperitoneally (ip) just before IND treatment; MQC (1 – 10 mg/kg, ig), AR420626 (0.01 – 0.1 mg/kg, ig or ip), CF3-MQC (1 mg/kg, ig), and GLP-2(3-33) (1 mg/kg, ip) [16]. GLP-2 (10 or 100 μg/kg, ip) was given twice a day (20 or 200 μg/kg/day), just before IND treatment and 6 hr after IND treatment. All chemicals were diluted in saline. All solutions were given at 1 ml/kg. DMSO 0.1% in saline was used as vehicle control.

Statistics

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. The number of animals in each experimental group was n = 6. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 6 (La Jolla, CA, USA) using one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons. Differences were considered significant when P values < 0.05. EC50 or IC50 was calculated using GraphPad Prism 6 with non-linear regressions of log (agonist) to normalized responses.

Results

Effect of luminal perfusion of FFA3 agonists on duodenal HCO3− secretion

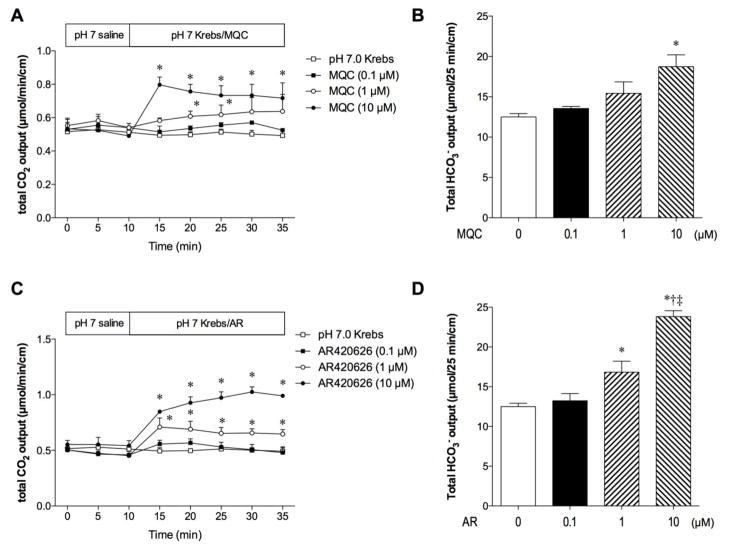

Luminal perfusion of MQC (0.1 – 10 μM) dose-dependently increased the rate of HCO3− secretion as measured as total CO2 output (Fig. 1A, B). AR420626 (0.1 – 10 μM) also dose-dependently stimulated HCO3− secretion, more potently than did MQC (Fig. 1C, D). EC50 values of MQC and AR420626 were 7.8 and 1.7 μM, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Effect of the FFA3 agonists on duodenal HCO3− secretion

The duodenal loop was perfused with pH 7.0 Krebs buffer with or without MQC or AR420626 (0.1 – 10 μM) in vivo. Duodenal HCO3− secretion was measured with flow-through pH and CO2 electrodes and expressed as total CO2 output. Luminal perfusion of MQC (A, B) or AR420626 (C, D) dose-dependently stimulated HCO3− secretion. A, C: Time course of secretory rate (μmol/min/cm). Each data point is expressed as mean ± SEM (n=6). *p < 0.05 vs. pH 7.0 Krebs group. B, D: Total HCO3− output (μmol/25 min/cm). Each column represents mean ± SEM (n=6). *p < 0.05 vs. pH 7.0 Krebs control group (0 μM agonist). †p < 0.05 vs. 0.1 μM agonist, ‡p < 0.05 vs. 1 μM agonist.

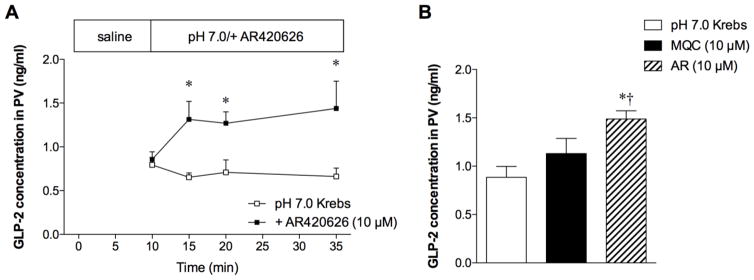

Luminal perfusion of AR420626 (10 μM) increased GLP-2 concentrations in PV plasma (Fig. 2A). At t = 35 min, PV GLP-2 concentrations of the AR420626 group were higher than in the pH 7.0 Krebs control and the MQC (10 μM) groups (Fig. 2B), consistent with higher HCO3− output in the AR420626 group than in the MQC group (Fig. 1). These results suggest that luminal FFA3 agonists increase GLP-2 release, stimulating duodenal HCO3− secretion.

Fig. 2.

Effect of the FFA3 agonists on GLP-2 release into portal vein (PV)

GLP-2 concentrations in PV were measured during the perfusion of the FFA3 agonists. A: Luminal perfusion of AR420626 (10 μM) increased PV GLP-2 concentrations. Each data point is expressed as mean ± SEM (n=6). *p < 0.05 vs. pH 7.0 Krebs group. B: GLP-2 concentrations in PV at t = 35 min. Each column represents mean ± SEM (n=6). *p < 0.05 vs. pH 7.0 Krebs group.

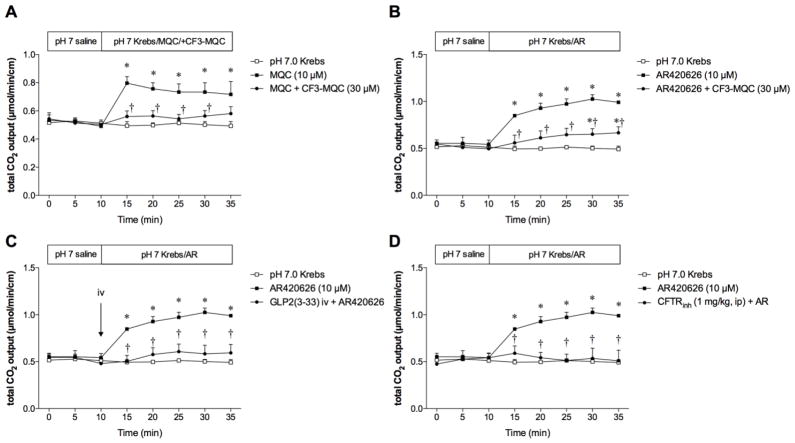

To confirm the selectivity of FFA3 activation, the FFA3 antagonist CF3-MQC (30 μM) was co-perfused with MQC or AR420626 (10 μM). Luminal co-perfusion of CF3-MQC reversed the MQC-induced augmentation of HCO3− secretion (Fig. 3A) and inhibited the AR420626-induced HCO3− secretion (Fig. 3B), supporting the hypothesis that the augmentation of HCO3− secretion due to luminal FFA3 agonists is mediated by FFA3 activation. The lesser efficacy of CF3-MQC for AR420626 than for MQC is possibly due to the greater potency of AR420626 than MQC for HCO3− secretion, as mentioned above.

Fig. 3.

Underlying mechanisms of FFA3 agonist-induced HCO3− secretion

Duodenal loops were perfused with a FFA3 agonist (10 μM) with or without the FFA3 antagonist CF3-MQC (30 μM, A, B), iv injection of the GLP-2 receptor antagonist GLP-2(3-33) (3 nmol/kg, C), or pretreatment with the CFTR inhibitor CFTRinh-172 (1 mg/kg, ip, D). Each data point is expressed as mean ± SEM (n=6). *p < 0.05 vs. pH 7.0 Krebs group, †p < 0.05 vs. MQC or AR420626 group.

Next, we examined the mechanism of AR420626-induced HCO3− secretion. The GLP-2 receptor antagonist GLP-2(3-33) (3 nmol/kg, iv) abolished AR420626-induced HCO3− secretion (Fig. 3C), consistent with the increased release of GLP-2 into the PV during AR420626 perfusion (Fig. 2A), strongly suggesting that luminal FFA3 agonists stimulate HCO3− secretion via GLP-2 release followed by GLP-2 receptor activation.

Since GLP-2-mediated HCO3− secretion is further mediated by vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) release, possibly followed by CFTR activation, we also examined the effect of CFTR inhibition on AR420626-induced HCO3− secretion. Pretreatment with the CFTR inhibitor CFTRinh-172 (1 mg/kg, ip) counteracted the stimulatory effect of AR420626 (10 μM) (Fig. 3D), suggesting that AR420626-induced HCO3− secretion is mediated by CFTR activation.

These results suggest that luminal FFA3 activation stimulates protective duodenal HCO3− secretion via GLP-2 release from FFA3-expressing L cells and via GLP-2 receptor activation in the myenteric plexus [17], followed by epithelial CFTR activation.

Effect of FFA3 agonists on IND-induced enteropathy

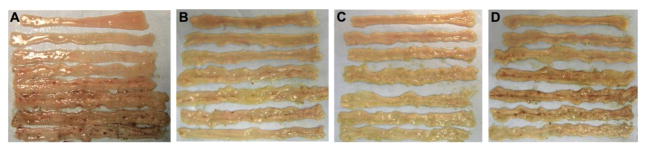

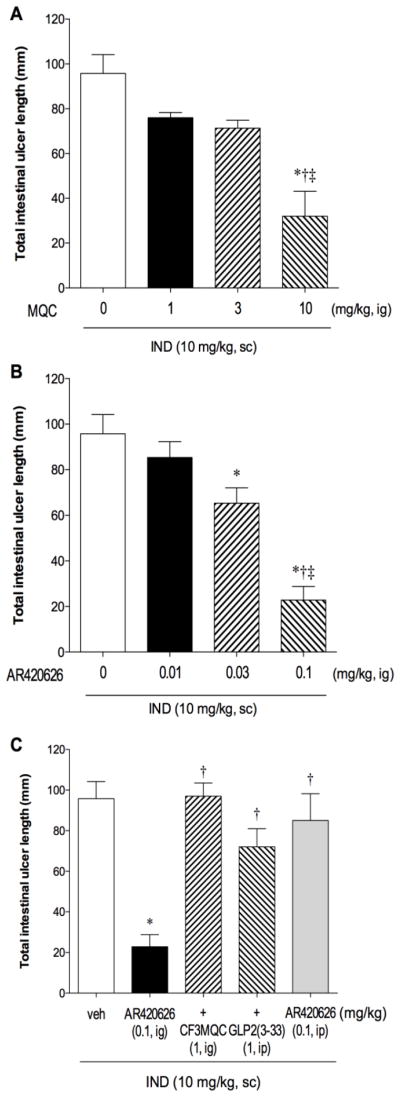

IND (10 mg/kg, sc) reproducibly produced small intestinal ulcers, mainly in the ileum (Fig. 4A), as previously reported [16]. MQC treatment (1–10 mg/kg, ig) with IND dose-dependently reduced intestinal injury (Fig. 4B) and ulcer scores (Fig. 5A). AR420626 (0.01 – 0.1 mg/kg, ig) also dose-dependently inhibited intestinal injury with higher potency (Fig. 4C, 5B). IC50 values of MQC and AR420626 were 6.0 and 0.047 mg/kg, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Representative macroscopic images of indomethacin (IND)-induced small intestinal ulcers

Small intestinal ulcers were induced by IND treatment (10 mg/kg, sc), with or without FFA3 agonist treatment. A: IND + vehicle. B: IND + MQC (10 mg/kg, ig). C: IND + AR420626 (0.1 mg/kg, ig). D: IND + AR420626 + GLP-2(3-33) (1 mg/kg, ip).

Fig. 5.

Effect of FFA3 agonists on indomethacin (IND)-induced small intestinal ulcers

Small intestinal ulcers were induced by IND treatment (10 mg/kg, sc), evaluated 24 hr after the treatment and expressed as total intestinal ulcer length (mm). MQC (1 – 10 mg/kg) or AR420626 (0.01 – 0.1 mg/kg) was given intragastrically (ig). MQC (A) and AR420626 (B) dose-dependently reduced IND-induced intestinal lesions. Each column represents mean ± SEM (n=6). A: *p < 0.05 vs. vehicle group (0 μM agonist). †p < 0.05 vs. 1 mg/kg agonist, ‡p < 0.05 vs. 3 mg/kg agonist. B: *p < 0.05 vs. vehicle group (0 μM agonist). †p < 0.05 vs. 0.01 mg/kg agonist, ‡p < 0.05 vs. 0.03 mg/kg agonist. C: AR420626 (0.1 mg/kg, ig)-induced prevention was reversed by co-treatment with the FFA3 antagonist CF3-MQC (1 mg/kg, ig), or GLP-2(3-33) (1 mg/kg, ip), whereas ip injection of AR420626 had no effect on IND-induced lesions. Each column represents mean ± SEM (n=6). *p < 0.05 vs. IND+vehicle (veh) group. †p < 0.05 vs. AR420626 group.

The reduction of IND-induced intestinal ulcers by AR420626 (0.1 mg/kg) was counteracted by co-treatment with the FFA3 antagonist CF3-MQC (1 mg/kg, ig) (Fig. 4C), indicating that the mucosal protective effect of AR420626 was mediated by FFA3 activation. Furthermore, co-treatment with the GLP-2 receptor antagonist GLP-2(3-33) (1 mg/kg, ip) reversed the inhibitory effect of AR420626 (Fig. 4D, 5C), supporting our hypothesis that GLP-2 released by FFA3 activation protects the mucosa.

FFA3 is also expressed in the enteric nerves in addition to L cells. FFA3 activation inhibits cholinergic-mediated ion secretion [27] and colonic motility [28] via direct neural FFA3 activation. We thus examined the effect of ip injection of AR420626 on IND-induced intestinal ulcer scores. AR420626 (0.1 mg/kg, ip) had no effect (Fig. 5C), suggesting that luminal rather than systemic effects of AR420626 protects against intestinal injury, and that the inhibitory effect of AR420626 is not mediated by cholinergic nerves, at least in our protocol.

Discussion

We have reported that FFA3 is expressed on L cells in rat duodenum [21], that stimulation of L cells releases GLP-2 [18,29], and that GLP-2 increases the rate of duodenal HCO3− secretion [18] and reduces IND-induced enteropathy [16]. In light of these data, we further hypothesized that selective FFA3 agonists might enhance mucosal defenses and prevent mucosal injury via the GLP-2 pathway.

We demonstrated that luminal FFA3 agonists stimulated mucosal protective duodenal HCO3− secretion with increased release of GLP-2 into the PV, followed by GLP-2 receptor activation. Furthermore, intragastric administration of FFA3 agonists prevented IND-induced enteropathy via GLP-2 receptor activation. Since exogenous GLP-2 prevents IND-induced enteropathy in rat model [16], the present study supports our hypothesis that enhancement of endogenous GLP-2 release by luminal agonists or nutrients that activate their corresponding receptors on L cells may protect the mucosa from injury [30].

We used two selective FFA3 agonists, MQC and AR420626 [31] in this study. Although the EC50 values of MQC and AR420626 are equivalent (pEC50 = 5.24 and 5.74, respectively) for human FFA3 [31], our study showed that in the rat, AR420626 was more potent than MQC with regard to duodenal HCO3− secretion and IND-induced enteropathy. Since the relative affinities of SCFAs for FFA3 is likely species-dependent [32], AR420626 may activate rat FFA3 more potently than does MQC.

We have reported that luminal perfusion of the non-selective FFA2 and FFA3 agonists, acetate and propionate, increase the rate of duodenal HCO3− secretion accompanied by increased GLP-2 release into the PV, the secretory response enhanced by a DPP4 inhibitor, whereas a selective FFA2 agonist stimulates HCO3− secretion via the 5-HT/acetylcholine pathway [21], suggesting that selective FFA3 activation induces GLP-2-related responses. As predicted, luminal perfusion of selective FFA3 agonists augmented duodenal HCO3− secretion accompanied by increased GLP-2 release, inhibited by a FFA3 antagonist and a GLP-2 receptor antagonist. The present study showed that pretreatment with a CFTR inhibitor abolished FFA3 agonist-induced augmented HCO3− secretion. Since GLP-2 receptors are expressed on enteric neurons, including VIPergic neurons, [17] and since VIP stimulates anion secretion via Gs-coupled GPCR activation followed by cAMP-mediated secretion [33] with increased insertion of CFTR into the apical membrane [34], this result suggests that GLP-2 activates a pathway that includes VIP release and CFTR activation. The observation that GLP-2-related HCO3− secretion via umami receptor activation increases VIP release, the effect inhibited by a GLP-2 receptor antagonist [18], also supports our hypothesis.

The mechanism underlying the protective effects of GLP-2 on IND-induced enteropathy remains unclear. GLP-2 followed by VIP and NO release stimulates duodenal HCO3− secretion [18], independent of PG-mediated anion secretion, suggesting that the GLP-2 pathway may compensate for the reduced anion secretion due to COX inhibition. Furthermore, GLP-2 is an intestinotrophic hormone due to release of the trophic factors epidermal growth factor (EGF) or insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) from subepithelial myofibroblasts expressing GLP-2 receptors [35,36]. EGF and/or IGF-1 may be involved in mucosal protection during the development of IND-induced injury. Since GLP-2 and IGF-1 are involved in the maintenance of intestinal permeability to macromolecules [36], exogenous or enhanced release of endogenous GLP-2 may augment epithelial barrier function to endotoxin, a luminal aggravating factor of NSAID-induced enteropathy [13]. Further study regarding the involvement of EGF or IGF-1 in intestinal barrier function will clarify the detailed mechanisms of GLP-2-mediated mucosal protection during the development of NSAID-induced enteropathy. Another possibility is that GLP-2 or FFA3 agonists reduce the enterohepatic circulation or biliary concentrations of IND, decreasing mucosal injury. Measurement of luminal and/or biliary IND concentrations in the presence of exogenous GLP-2 or FFA3 agonists would help test this hypothesis.

FFA3 is expressed on L cells [21], but also on enteric nerves [27,37]. Neural FFA3 activation inversely regulates nicotinic acetylcholine receptor-mediated anion secretion [27] and motility [28] in rat proximal colon. Since IND-induced enteropathy is reduced by the anti-motility effects of atropine on IND-induced hypermotility [11], it is possible that the prevention of NSAID injury by FFA3 agonists is mediated via neural pathways. Our results showed that luminally-applied FFA3 agonists prevent IND-induced enteropathy, whereas ip injection of FFA3 agonists failed to inhibit the injury, suggesting that luminal FFA3 activation on L cells rather than neural FFA3 activation by absorbed FFA3 agonists is therapeutic for IND-induced enteropathy.

We have also found that although FFA2 activation enhances duodenal HCO3− secretion via 5-HT4 receptor activation [21], FFA2 activation accompanying IND treatment induces duodenal erosions with excessive release of 5-HT from EC cells, increasing the vulnerability of the duodenal mucosa to gastric acid via 5-HT3 receptor activation with consequent reduction of blood flow [38]. Intragastric administration of the mixed FFA2/FFA3 agonist acetate had variable effects on IND-induced enteropathy with injury either aggravated or reduced (data not shown). This result also supports our observations that FFA2 activation aggravates, but FFA3 activation prevents IND-induced enteropathy.

Since there is no widely accepted clinical therapeutic for NSAID-induced enteropathy, we propose that orally ingested synthetic chemical compounds or nutrients intended to maximally stimulate endogenous GLP-2 release from foregut L-cells may be effective in the treatment of NSAID-induced enteropathy. These candidates are the umami receptor agonists including amino acids [16,18,39], the bile acid receptor TGR5 agonists [29,40], the addition of a DPP4 inhibitor to reduce GLP-2 degradation [16,39], and the FFA3 agonists shown in the present study. We hope that clinical translation of these novel mechanisms can lead to safer and more effective therapies of NSAID-induced enteropathy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stacey Jung for her assistance with manuscript preparation and Drs. Paul Guth and Eli Engel for their helpful discussion.

Funding

This work was supported by a Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Review Award and NIH R01 DK54221.

Abbreviations

- 5-HT

5-hydroxytryptamine

- CF3-MQC

N-(2-methylphenyl)-4-[5-(2-trifluoromethoxy-phenyl)-furan-2-yl)- 2-methyl-5-oxo-1,4,5,6,7,8-hexahydro-quinoline-3-carboxamide

- CFTR

cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- DPP4

dipeptidyl peptidase 4

- FFA3

free fatty acid receptor 3

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- GLP

glucagon-like peptide

- IND

indomethacin

- MQC

N-[2-methylphenyl]-[4-furan-3-yl]-2-methyl- 5-oxo-1,4,5,6,7,8-hexahydroquinoline-3-carboxamide

- PV

portal vein

- SCFA

short-chain fatty acid

Footnotes

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

Y.A. and J.D.K. were responsible for the study concept and design, and for drafting article. Ay.K. and K.I. were responsible for chemical design and synthesis. H.S., Y.A., K.N. and K.M. were responsible for collection, assembly, and analysis of data. Y.A., At.K. and J.D.K. were responsible for data interpretation.

References

- 1.Higuchi K, Umegaki E, Watanabe T, et al. Present status and strategy of NSAIDs-induced small bowel injury. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:879–888. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsumoto T, Kudo T, Esaki M, et al. Prevalence of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced enteropathy determined by double-balloon endoscopy: a Japanese multicenter study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:490–496. doi: 10.1080/00365520701794121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graham DY, Opekun AR, Willingham FF, Qureshi WA. Visible small-intestinal mucosal injury in chronic NSAID users. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:55–59. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00603-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallace JL. NSAID gastropathy and enteropathy: distinct pathogenesis likely necessitates distinct prevention strategies. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165:67–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01509.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Omatsu T, Naito Y, Handa O, et al. Reactive oxygen species-quenching and anti-apoptotic effect of polaprezinc on indomethacin-induced small intestinal epithelial cell injury. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:692–702. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0213-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duggan DE, Hooke KF, Noll RM, Kwan KC. Enterohepatic circulation of indomethacin and its role in intestinal irritation. Biochem Pharmacol. 1975;24:1749–1754. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(75)90450-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iwai T, Ichikawa T, Kida M, et al. Vulnerable sites and changes in mucin in the rat small intestine after non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs administration. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3369–3376. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1185-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimizu K, Koga H, Iida M, Haruma K. Microcirculatory changes in experimental mesenteric longitudinal ulcers of the small intestine in rats. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:3019–3028. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9804-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takeuchi K, Kita K, Hayashi S, Aihara E. Regulatory mechanism of duodenal bicarbonate secretion: Roles of endogenous prostaglandins and nitric oxide. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;130:59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akiba Y, Guth PH, Engel E, Nastaskin I, Kaunitz JD. Dynamic regulation of mucus gel thickness in rat duodenum. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;279:G437–G447. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2000.279.2.G437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takeuchi K, Miyazawa T, Tanaka A, Kato S, Kunikata T. Pathogenic importance of intestinal hypermotility in NSAID-induced small intestinal damage in rats. Digestion. 2002;66:30–41. doi: 10.1159/000064419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Konaka A, Kato S, Tanaka A, Kunikata T, Korolkiewicz R, Takeuchi K. Roles of enterobacteria, nitric oxide and neutrophil in pathogenesis of indomethacin-induced small intestinal lesions in rats. Pharmacol Res. 1999;40:517–524. doi: 10.1006/phrs.1999.0550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watanabe T, Higuchi K, Kobata A, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced small intestinal damage is Toll-like receptor 4 dependent. Gut. 2008;57:181–187. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.125963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallace JL, Syer S, Denou E, et al. Proton pump inhibitors exacerbate NSAID-induced small intestinal injury by inducing dysbiosis. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1314–1322. 1322. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uchida A, Yamada T, Hayakawa T, Hoshino M. Taurochenodeoxycholic acid ameliorates and ursodeoxycholic acid exacerbates small intestinal inflammation. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272:G1249–G1257. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.5.G1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inoue T, Higashiyama M, Kaji I, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibition prevents the formation and promotes the healing of indomethacin-induced intestinal ulcers in rats. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:1286–1295. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-3001-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guan X, Karpen HE, Stephens J, et al. GLP-2 receptor localizes to enteric neurons and endocrine cells expressing vasoactive peptides and mediates increased blood flow. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:150–164. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang JH, Inoue T, Higashiyama M, et al. Umami receptor activation increases duodenal bicarbonate secretion via glucagon-like peptide-2 release in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;339:464–473. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.184788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boushey RP, Yusta B, Drucker DJ. Glucagon-like peptide 2 decreases mortality and reduces the severity of indomethacin-induced murine enteritis. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:E937–E947. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.277.5.E937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rønnestad I, Akiba Y, Kaji I, Kaunitz JD. Duodenal luminal nutrient sensing. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2014;19C:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akiba Y, Inoue T, Kaji I, et al. Short-chain fatty acid sensing in rat duodenum. J Physiol. 2015;593:585–599. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.280792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hogan DL, Crombie DL, Isenberg JI, Svendsen P, Schaffalitzky de Muckadell OB, Ainsworth MA. CFTR mediates cAMP- and Ca2+-activated duodenal epithelial HCO3− secretion. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:G872–G878. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.4.G872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ulven T. Short-chain free fatty acid receptors FFA2/GPR43 and FFA3/GPR41 as new potential therapeutic targets. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2012;3:111. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2012.00111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akiba Y, Jung M, Ouk S, Kaunitz JD. A novel small molecule CFTR inhibitor attenuates HCO3− secretion and duodenal ulcer formation in rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G753–G759. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00130.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaji I, Iwanaga T, Watanabe M, et al. SCFA transport in rat duodenum. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2015;308:G188–G197. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00298.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mizumori M, Meyerowitz J, Takeuchi T, et al. Epithelial carbonic anhydrases facilitate PCO2 and pH regulation in rat duodenal mucosa. J Physiol. 2006;573:827–842. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.107581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaji I, Akiba Y, Konno K, et al. Neural FFA3 activation inversely regulates anion secretion evoked by nicotinic ACh receptor activation in rat proximal colon. J Physiol. 2016;594:3339–3352. doi: 10.1113/JP271441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaji I, Akiba Y, Furuyama T, Kaunitz JD. FFA3 activation inhibits nicotine-induced secretion and motility via enteric nervous reflex in rat proximal colon. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:S352. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inoue T, Wang JH, Higashiyama M, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibition potentiates amino acid- and bile acid-induced bicarbonate secretion in rat duodenum. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;303:G810–G816. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00195.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akiba Y, Kaunitz JD. Duodenal chemosensing and mucosal defenses. Digestion. 2011;83(Suppl 1):25–31. doi: 10.1159/000323401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hudson BD, Christiansen E, Murdoch H, et al. Complex pharmacology of novel allosteric free fatty acid 3 receptor ligands. Mol Pharmacol. 2014;86:200–210. doi: 10.1124/mol.114.093294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown AJ, Goldsworthy SM, Barnes AA, et al. The Orphan G protein-coupled receptors GPR41 and GPR43 are activated by propionate and other short chain carboxylic acids. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11312–11319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211609200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amelsberg M, Amelsberg A, Ainsworth MA, Hogan DL, Isenberg JI. Cyclic adenosine-3′, 5′-monophosphate production is greater in rabbit duodenal crypt than in villus cells. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:233–239. doi: 10.3109/00365529609004872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ameen NA, Martensson B, Bourguinon L, Marino C, Isenberg J, McLaughlin GE. CFTR channel insertion to the apical surface in rat duodenal villus epithelial cells is upregulated by VIP in vivo. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(Pt 6):887–894. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.6.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bahrami J, Yusta B, Drucker DJ. ErbB activity links the glucagon-like peptide-2 receptor to refeeding-induced adaptation in the murine small bowel. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2447–2456. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dong CX, Zhao W, Solomon C, et al. The intestinal epithelial insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor links glucagon-like peptide-2 action to gut barrier function. Endocrinology. 2014;155:370–379. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nøhr MK, Egerod KL, Christiansen SH, et al. Expression of the short chain fatty acid receptor GPR41/FFAR3 in autonomic and somatic sensory ganglia. Neuroscience. 2015;290:126–137. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akiba Y, Kaji I, Guth PH, Engel E, Kaunitz JD. GPR43 activation with COX inhibition induces duodenal injury via 5-HT pathway. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:S504–S505. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fujiwara K, Inoue T, Yorifuji N, et al. Combined treatment with dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) inhibitor sitagliptin and elemental diets reduced indomethacin-induced intestinal injury in rats via the increase of mucosal glucagon-like peptide-2 concentration. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2015;56:155–162. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.14-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sakanaka T, Inoue T, Yorifuji N, et al. The effects of a TGR5 agonist and a dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitor on dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in mice. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30(Suppl 1):60–65. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]