Abstract

Elevated levels of chemokine receptor CCR9 expression in solid tumors may contribute to poor patient prognosis. In this study, we characterized a novel CCR9‐mediated pathway that promotes pancreatic cancer cell invasion and drug resistance, indicating that CCR9 may play a critical role in cancer progression through activation of β‐catenin. We noted that the CCL25/CCR9 axis in pancreatic cancer cells induced the activation of β‐catenin, which enhanced cell proliferation, invasion, and drug resistance. CCR9‐mediated activation of β‐catenin and the resulting downstream effects were effectively inhibited by blockade of the PI3K/AKT pathway, but not by antagonism of Wnt. Importantly, we discovered that CCR9/CCL25 increased the lethal dose of gemcitabine, suggesting decreased efficacy of anti‐cancer drugs with CCR9 signaling. Through in silico computational modeling, we identified candidate CCR9 antagonists and tested their effects on CCR9/β‐catenin regulation of cell signaling and drug sensitivity. When combined with gemcitabine, it resulted in synergistic cytotoxicity. Our results show that CCR9/β‐catenin signaling enhances pancreatic cancer invasiveness and chemoresistance, and may be a highly novel therapeutic target.

Keywords: β‐catenin, CCL25, CCR9, Drug resistance, Pancreatic cancer

Highlights

CCR9 receptor mediated signaling increases resistance to chemotherapy agents.

CCR9 receptor mediated signaling activates β‐catenin.

CCR9‐mediated activation of β‐catenin is dependent on the PI3K/AKT pathway.

Novel CCR9 inhibitor was identified in silico study of the CCR9 protein structure.

Novel CCR9 inhibitor synergizes with standard chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer.

1. Introduction

Chemokines and their corresponding receptors mediate cellular movement, such as leukocyte trafficking, stem cell migration, and recruitment of progenitor cells in organ development (Masyuk and Brand‐Saberi, 2015; Zlotnik et al., 2011). The chemokine receptor–ligand axis CCR9/CCL25 is responsible for T‐cell development and chemotrafficking of thymocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells in normal tissues of the thymus and small intestine (Vicari et al., 1997; Zaballos et al., 1999). There is now considerable evidence linking the CCR9/CCL25 axis to cancer progression and metastasis (Amersi et al., 2008; Heinrich et al., 2013; Singh et al., 2011; Zaballos et al., 1999). For example, CCR9 involvement in melanoma‐specific metastasis to the small intestine has been attributed to the invasion of CCR9‐expressing melanoma cells toward the specific chemoattractant CCL25 in the small intestine (Amersi et al., 2008). Because we have previously demonstrated high expression of CCR9 in pancreatic cancer cells, we aim to further characterize CCR9‐mediated signaling and the potential role of CCR9 in the invasive phenotype of pancreatic cancer (Heinrich et al., 2013; Shen et al., 2009).

β‐catenin is a key factor in the Wnt signaling pathway with its active dephosphorylated form serving as a transcriptional co‐activator of genes involved in cell cycle progression and proliferation (Vlad et al., 2008). It is also a crucial component of adherens junctions, mediating cell–cell adhesion (Valenta et al., 2012) and regulating cell migratory behavior (Kikuta et al., 2010). Interestingly, active β‐catenin is removed from adherens junctions, resulting in disintegration of the junction and increased cell mobility (Al‐Aynati et al., 2004). Studies examining the role of β‐catenin in pancreatic cancer are limited, but published reports suggest it may influence the progression of human pancreatic cancer (Froeling et al., 2011; Li et al., 2005; Morris et al., 2010). Because both β‐catenin and the CCR9/CCL25 axis are involved in cell movement and migration, we hypothesized a potential link between β‐catenin and CCR9 and that this relationship could enhance pancreatic cancer invasiveness.

Given the emerging data on the role of CCR9 in neoplastic progression, we also hypothesized that CCR9 signaling was a potential novel therapeutic target in pancreatic cancer. Accordingly, the objectives of this study were two‐fold. First, we sought to characterize CCR9 signaling in pancreatic cancer cells. Second, our aim was to identify a candidate CCR9 antagonist to show that blockade of CCR9‐mediated signaling could abrogate the invasiveness of pancreatic cancer cells.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents

Recombinant human CCL25 was obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Additional reagents include: 10 mM para‐nitrophenyl phosphate (Sigma Aldrich; St. Louis, MO), gemcitabine (LC Laboratories; Woburn, MA), WNT3a (R&D Systems), IWR‐1‐endo, a WNT inhibitor (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; Santa Cruz, CA), 1‐[1,1′‐biphenyl]‐4‐yl‐2‐(2,3‐dihydro‐9H‐imidazo[1,2‐a]benzimidazol‐9‐yl) ethanone hydrobromide (CCT), a β‐catenin inhibitor (R&D Systems), and LY294002, a phosphoinositol‐3 kinase (PI3K) inhibitor (Sigma Aldrich). Treatment with CCL25 was performed at a concentration of 400 ng/ml. The following antibodies were used: active β‐catenin (unphosphorylated on serine 37) (Millipore; Billerica, MA), total β‐catenin (BD Bioscience; Sparks, MD), phospho and total AKT (Cell Signaling; Beverly, MA), Cyclin E1 (BD Bioscience), Cyclin D1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), E‐Cadherin (BD Bioscience), p84 (Genetex; Irvine, CA), and GAPDH (Advanced Immunochemical; Long Beach, CA).

2.2. Cell culture

The established human pancreatic cancer cell lines AsPC‐1, MIAPaCa‐2 and PANC‐1, were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The cell lines were immediately cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen after they were obtained. PANC‐1 cells were grown in Dulbecco's Minimal Essential Medium (DMEM) (Mediatech; Manassas, VA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Omega Scientific; Tarzana, CA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S) (Gibco; Grand Island, NY) under standard conditions at 37 °C with 5% CO2. MIAPaCa‐2 cells were grown in as the same media as PANC‐1 cells with an additional 2.5% horse serum (Omega Scientific; Tarzana, CA). AsPC‐1 cells were grown in RPMI1640 (Mediatech; Manassas, VA) with 10% FBS, 1% P/S, 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Gibco; Grand Island, NY) and 1% non‐essential amino acids (Irvine Scientific; Santa Ana, CA).

2.3. Phospho‐protein array

To determine signaling pathways that were activated following exposure of MIAPaCa‐2 cells to CCL25, the Phospho Explorer Array (Full Moon Biosystems; Sunnyvale, CA) was used according to the manufacturer's protocol. The assay measures the levels of over 200 phospho‐specific antibodies and corresponding total proteins. Briefly, MIAPaCa‐2 cells were treated with CCL25 for 15 min, and cell lysates were extracted as suggested in the manufacturer's protocol. The antibody array was incubated with a blocking solution for 45 min and then washed extensively with double distilled water. Biotin‐labeled cells were added to the array and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The array slide was rinsed with double distilled water prior to detection with Cy3‐Streptavidin using Axon GenePix® 4000B microarray scanner (Molecular Devices). Ratios of phosphorylated to unphosphorylated proteins were calculated from the intensity values obtained.

2.4. Immunoblotting

Cell lysates were collected as previously described (Shen et al., 2009). Twenty micrograms of protein were separated on SDS‐polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore). The membranes were blocked for 2 h and probed overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies. After washing, membranes were labeled with horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated secondary antibodies (BioRad; Hercules, CA). Blots were developed with a chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce; Rockford, IL) and imaged. Fold‐changes were determined using Alpha View Software (Protein Simple; Santa Clara, CA).

2.5. Immunofluorescence

MIAPaCa‐2 cells were seeded on chamber slides, allowed to attach overnight, then serum‐starved for 24 h prior to treatment with CCL25 for 0–30 min. After treatment, cells were fixed and permeabilized. We then probed for β‐catenin (1:100 dilution, incubated overnight at 4 °C) following standard methods. Slides were visualized and photographed using LSM510 upright 2‐photon confocal microscope (Zeiss; Jena, Germany) at 60× magnification. Fold‐change was determined using Image‐pro software (Media Cybernetics; Rockville, MD).

2.6. Nuclear extraction

Cells were plated at 2.5 × 106 and incubated overnight. Cells were serum‐starved for 24 h and treated with CCL25 for 0–30 min. Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were separated using a commercial assay (Ne‐Per extraction reagents) (Thermo Scientific; Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were collected using trypsin and washed with PBS. After centrifugation, cell pellets were incubated with supplied reagents to permeate the cell membrane and extract the cytoplasmic proteins. The remaining insoluble pellet was incubated with a supplied reagent to extract the nuclear proteins. Protein fractions were used in Western blots with GADPH as the control for cytoplasmic proteins and p84 for the nuclear fraction.

2.7. Proliferation assay

Cells were pre‐treated with 15 μM Ly294002 for 60 min, then stimulated with CCL25 for 48 h followed by re‐feeding CCL25 and grown for another 24 h. Cell growth was measured using CellTiter‐Glo Luminescent assay kit (Promega; San Luis Obispo, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and luminescence was measured using Veritas software (Luminometer; Turner Biosystems‐Promega).

2.8. Invasion assay

Invasion was measured using a matrigel invasion assay (BD Biosciences). In brief, chemoattractant was placed in the wells of a 24‐well plate, and pancreatic cancer cells (1 × 105) were plated on each matrigel‐coated insert. Cells were then pretreated with and without the corresponding drugs and allowed to invade through the matrigel for 24 h toward the bottom chamber, which contained media and the chemoattractant, CCL25. The invading cells were fixed and stained using DiffQuik staining kit (Siemens; Newark, DE), and those in 5 random adjacent fields at 200× magnification were counted under light microscopy.

2.9. Computational modeling

Previously, we predicted the three‐dimensional structure of the human chemokine receptor CXCR4 and the binding site of the small molecule antagonist 1T1t (Lam et al., 2011). In this study, a homology model of CCR9 was generated using MODELLER (Sali and Blundell, 1993) based on the recently‐solved crystal structure of CXCR4 (PDB code 3ODU) as the template structure (Wu et al., 2010). The CLUSTALW sequence alignment algorithm (Larkin et al., 2007) was used to align the human CCR9 sequence to human CXCR4 sequence, with manual adjustments to ensure the alignment of highly conserved residues in the Class A G‐protein coupled receptor (GPCR) family. In order to equilibrate this structure in lipid bilayer and water, we performed 40 ns of molecular dynamics simulations using the GROMACS simulation software (Berendsen et al., 1995). Representative stable protein conformations from the molecular dynamics simulations were selected for ligand docking. These structures were selected from the simulations based on the distance (RMSD) from the average simulation structure. Long periods, on the order of hundreds of picoseconds, of stable RMSD were assumed to represent potential energy wells in the protein's conformational landscape. Docking was performed on the structures in the middle of the stable periods.

2.10. Docking of ligands

In prior work we performed virtual ligand screening of the National Cancer Institute small molecule compound library (∼360,000 compounds) and tested 36 candidate CXCR4 antagonists (Kim et al., 2012). We docked these same 36 NCI compounds along with CCX282, a known CCR9 antagonist, into four CCR9 models extracted from the dynamics trajectories of CCR9. Multiple CCR9 models were used for docking to account for protein flexibility. Fifty initial conformations of each ligand were generated using the Monte Carlo method in the Macromodel module (MacroModel, version 9.9) (Schrödinger, LLC; New York, NY) for each ligand. The compounds were docked using Glide SP (Glide, version 5.5, Schrödinger) with an energy cutoff of 100 kcal/mol and a maximum of 10,000 docked poses were retained. The van der Waals radii of the ligand atoms were scaled to 50% of their original radii to accommodate for protein flexibility in the binding site. The interaction energy of each residue within 5 Å of the ligand was calculated using a cavity analysis program developed in our laboratory. The side chain conformations of the residues within 5 Å of the ligand were optimized using the PRIME side chain optimization module (Prime, version 3.0, Schrödinger). Some of the side chain conformations were also optimized to make close polar contacts.

2.11. CCR9 recruitment of β‐arrestin

CCR9‐mediated signaling results in the recruitment of β‐arrestin to the carboxy terminus of CCR9. To verify the inhibition of β‐arrestin recruitment by candidate CCR9 antagonists, we used a commercial CCR9 assay (PathHunter eXpress) (DiscoveRx; Fremont, CA). Briefly, CCR9‐positive cells (8 × 103) were seeded in 96‐well plates and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. Cells were pre‐treated with candidate antagonists for 30 min and then exposed to CCL25 (400 nM) for 1.5 h. Cells were then incubated in PathHunter Detection Reagent mixture (DiscoveRx) at room temperature for 1 h. Plates were read on a luminescence plate reader (BMG PHERAstar) (BMG Labtech; Cary, NC). β‐Arrestin recruitment (%) was calculated by dividing the luminescence signal of the testing well by the CCL25‐treated control well.

2.12. Calcium flux assay

A calcium flux assay was performed to assess the candidate anti‐CCR9 compounds using commercial AequoZen FroZen cells (PerkinElmer; Shelton, CT). Cells were thawed and resuspended in assay medium with 5 μM Coelenterazine h at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml and incubated at room temperature protected from light and with constant agitation overnight. Cells were then diluted to 1 × 105 cells/ml with assay medium and incubated as described above for 30 min. Cells (5 × 104) were seeded in 96‐well plates by a Synergy reader's dispenser (BioTek; Winooski, VT) and pre‐treated with candidate antagonists for 30 min at room temperature. Changes in intracellular calcium concentration with CCL25 (30 nM) were monitored by fluorescence at 494 nm and 516 nm using a Synergy reader (BioTek).

2.13. Drug toxicity assay

A cell acid phosphatase activity assay was used to determine if CCL25 could alter the lethal dose of gemcitabine. Pancreatic cancer cells (3.5 × 103) were seeded and grown for 24 h in 96‐well plates and then treated with various concentrations of gemcitabine (0.1 nM−1 mM) for an additional 72 h. In order to measure the portion of viable cells, para‐nitrophenyl phosphate reaction solution (0.1 M sodium acetate, 0.1% triton, 10 mM para‐nitrophenyl phosphate) was added to cells for 2 h at 37 °C, and the reaction was stopped by adding 1 N NaOH. The absorbance was then read at OD 405 nm (SpectraMax M2) (Molecular Devices; Sunnyvale, CA). The IC50, the drug concentration leading to a decrease in cell acid phosphatase activity of 50%, was determined for the cells.

2.14. Combination index determination

Cells were plated in 96‐well plates and treated with gemcitabine, candidate CCR9 antagonist alone, or a combination of the two for 72 h. They were then incubated with para‐nitrophenyl phosphate reaction solution for 2 h at 37 °C. The reaction was stopped with the addition of 1 N NaOH and the plate was read at OD 405 nm (SpectraMax M2). The combination index was calculated using Calcusyn software (Biosoft; Cambridge, U.K.). Values <1.0 indicate a synergistic cytotoxic effect of two compounds.

3. Results

3.1. CCR9 stimulation results in activation of β‐catenin

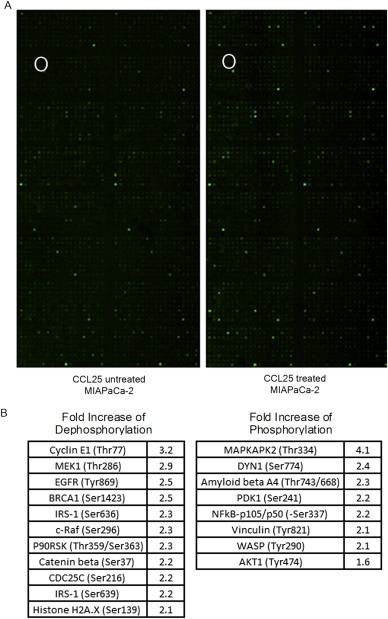

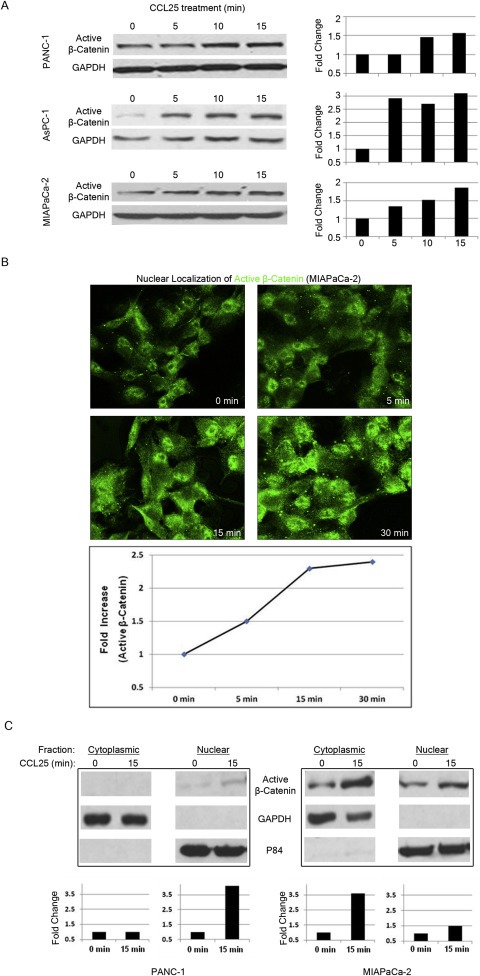

Our aim was to identify activated signaling pathways in pancreatic cancer cells following exposure to CCL25. We selected the MIAPaCa‐2 cell line for this assay since these cells responded consistently to CCL25 within 20 min in prior experiments (Supplementary Figure 1). We performed a phospho‐protein array, in which MIAPaCa‐2 cells were treated with CCL25 for 15 min (Figure 1A). We observed a 2.2‐fold increase in the expression of the active form of β‐catenin (dephosphorylated on Ser 37) (Figure 1B). To verify increased β‐catenin by CCL25, we examined active β‐catenin expression by western blot assay in AsPC‐1, MIAPaCa‐2, and PANC‐1 cells, and noted increased expression in all three lines within 15 min of stimulation (Figure 2A). We also performed immunofluorescence (IF) imaging in MIAPaCa‐2 cells, observing increased active β‐catenin expression (range 1.5‐ to 2.4‐fold) and nuclear localization beginning at 5 min post‐stimulation and lasting at least 30 min (Figure 2B). To confirm increased nuclear transportation of β‐catenin following CCL25 stimulation, we performed a nuclear‐cytoplasmic extraction of cell lysates. We discovered that active β‐catenin increased in both the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions at 15 min post‐stimulation (Figure 2C).

Figure 1.

Quantitative analysis of activated signaling pathways following CCL25 treatment. A) Phospho‐specific antibody microarrays were utilized to identify key signaling pathways regulated by CCL25 in MIAPaCa‐2 cells. The spot for active β‐catenin in the phospho‐protein array was marked with circle. B) Ratios of phosphorylated to unphosphorylated proteins quantified by fluorescent intensity in CCL25‐treated cells were calculated and compared to the untreated cell.

Figure 2.

β‐catenin is activated following CCL25 exposure. A) PANC‐1, AsPC‐1 and MIAPaCa‐2 cells were treated with CCL25 for the indicated times and expression of activated β‐catenin was quantified after protein blotting. B) Increased expression and nuclear localization of active β‐catenin by CCL25 stimulation in MIAPaCa‐2 cells. C) Increased expression of active β‐catenin by CCL25 stimulation in the cell lysates extracted from both cytoplasmic and nuclear cell fractions. GAPDH and p84 were used as loading control for cytoplasmic and nuclear lysates, respectively.

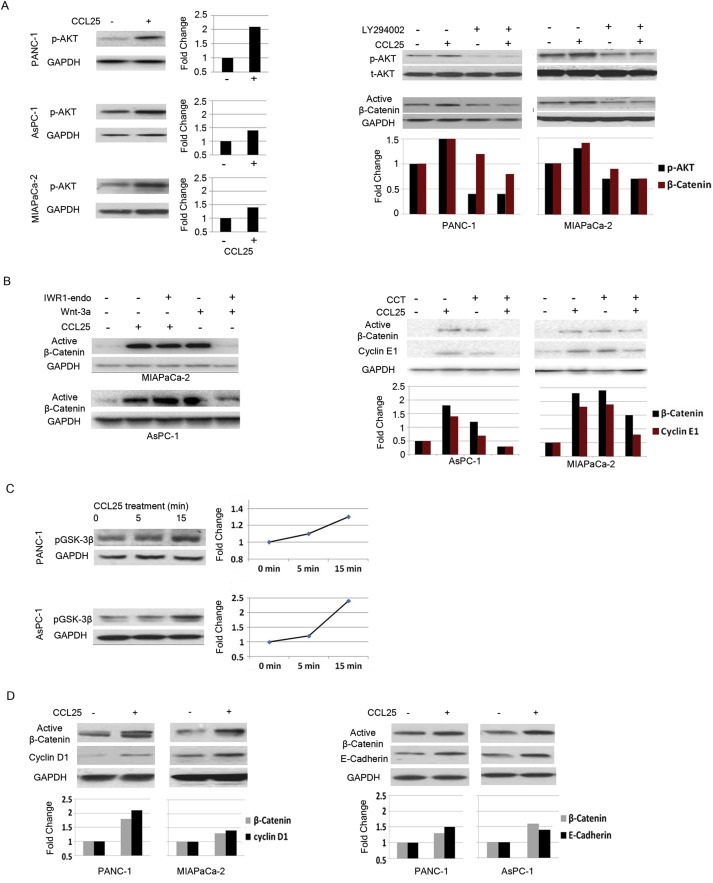

3.2. β‐catenin activation is dependent on the PI3K/AKT pathway but independent of Wnt

Recently, it was shown that CCL25 binding induces the phosphorylation of AKT (Youn et al., 2001). To confirm the involvement of the PI3K/AKT pathway in CCR9‐mediated activation of β‐catenin, we examined the expression of phospho‐AKT following CCL25 treatment. We observed increased levels of phospho‐AKT in all three cell lines (Figure 3A‐left). Pre‐treatment with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (15 μM) attenuated CCL25‐mediated increases in both phospho‐AKT and active β‐catenin (Figure 3A‐right).

Figure 3.

CCL25‐mediated activation of β‐catenin is PI3K‐dependent, but Wnt‐independent. A) CCL25‐treated PANC‐1, AsPC‐1 and MiaPaCa2 cells for the indicated times induced activation of AKT (left), and treatment with LY294002 suppressed CCL25‐mediated p‐AKT expression (right). B) IWR1‐endo was able to block β‐catenin activation following Wnt‐3a stimulation, but did not inhibit CCL25‐mediated activation of β‐catenin (left). The β‐catenin‐specific inhibitor, CCT, blocked CCL25‐mediated activation of β‐catenin and inhibited expression of cyclin E (right). C) The activation of β‐catenin induced phosphorylation of pGSK‐3β. D) Protein expression levels of cyclin D1 (left) and E‐Cadherin (right) were also increased. Protein lysates were collected for immunoblotting 15 min after CCL25 treatment from pancreatic cancer cells.

Because β‐catenin is one of the major downstream targets of the Wnt signaling pathway, we assessed whether the Wnt pathway was integral to CCR9/CCL25 signaling. Exposure to CCL25 or Wnt3a (agonist of Wnt signaling) both induced active β‐catenin expression in pancreatic cancer cells. Pre‐treatment with IWR‐1‐endo (15 μM) (Wnt pathway inhibitor) attenuated Wnt3a‐driven increases in active β‐catenin expression, but IWR‐1‐endo did not inhibit CCL25‐mediated increases in active β‐catenin (Figure 3B‐left). Co‐treatment of CCL25 with CCT (20 μM) (β‐catenin specific inhibitor) blocked the expected increase in active β‐catenin and its transcriptional target cyclin E1 (Figure 3B‐right). These results suggest that Wnt signaling is not measurably involved in CCR9‐mediated activation of β‐catenin in pancreatic cancer cells. Furthermore, GSK‐3β, the β‐catenin inhibiting kinase that is destabilized by AKT‐dependent phosphorylation, was shown to have increased phosphorylation levels following exposure to CCL25 (Figure 3C). Taken together, these results indicate that CCR9/CCL25 receptor mediated activation of β‐catenin occurs through the PI3K/AKT pathway independent of Wnt.

3.3. CCL25 increases expression of Cyclin E1, Cyclin D1, and E‐Cadherin

The effects of β‐catenin are wide‐ranging and include transcription of a number of proteins including Cyclin E1 and Cyclin D1 (Botrugno et al., 2004; Li et al., 2005). We found that expression of cyclin E1 and D1 increased following exposure to CCL25 (Figure 3B‐right and 3D‐left). This finding verifies that active β‐catenin not only enters the nucleus, but is functionally active. CCL25 treatment also induced a minor increase in E‐Cadherin expression (Figure 3D‐right).

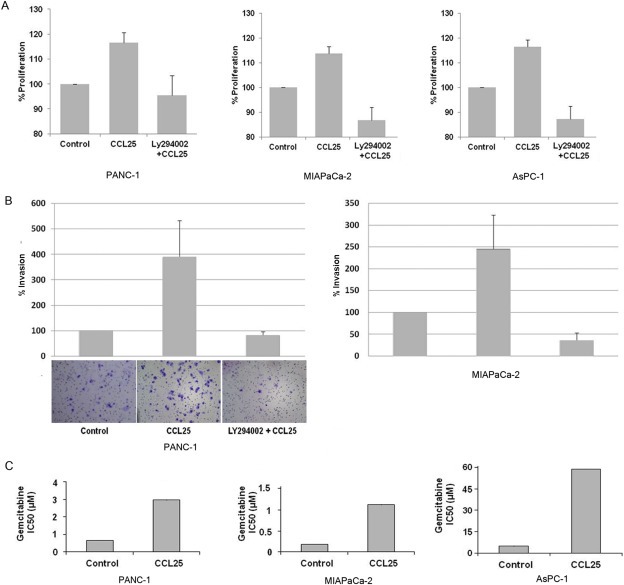

3.4. CCL25 increases proliferation and invasiveness in a PI3K/AKT‐dependent manner

Pancreatic cancer cells were treated with CCL25 under serum‐free conditions for 72 h with and without pre‐treatment of LY294002 prior to assessing proliferation. The cells treated with CCL25 demonstrated an approximate 20% increase in cell population compared to control cells (Figure 4A). Cells, which were pre‐treated with LY294002, had attenuated CCL25‐mediated growth stimulation (Figure 4A), indicating that the PI3K/AKT pathway regulates CCL25‐mediated proliferation.

Figure 4.

CCL25 increases proliferation and invasion of pancreatic cancer cell lines and augments resistance to gemcitabine. A) PANC‐1, MIAPaCa‐2 and AsPC‐1 cells were treated with CCL25 under serum‐free condition for 72 h with and without LY294002 prior to assessing proliferation. B) PANC‐1 and MIAPaCa‐2 cells were plated in the Boyden chamber with or without LY294002. CCL25 was used as a chemoattractant in the serum free media, and cells were allowed to invade for 24 h. The invading cells were stained and counted at 5 different fields per experiment. The left bottom panels show photographs taken of a representative field in each condition. C) Pre‐treatment of PANC‐1, MIAPaCa‐2 and ASPC‐1 cells with CCL25 increased IC50 values for gemcitabine treatment.

Because pancreatic cancer has the propensity to metastasize, we examined the effects of CCR9 signaling on the invasiveness of pancreatic cancer cells. Using a modified Boyden chamber matrigel invasion assay, we discovered that CCL25 increased invasion of PANC‐1 and MIAPaCa‐2 cells by 4.0 and 2.5‐fold, respectively (Figure 4B). Inhibiting the PI3K/AKT pathway with LY294002 also blocked the CCL25‐driven invasiveness. In contrast, AsPC‐1 cells were not invasive in this setting and showed no invasive capabilities even when 10% FBS was used as the chemoattractant. Taken together, the CCR9/CCL25 axis is an important mechanism for enhanced pancreatic cancer invasiveness that is dependent on the PI3K/AKT pathway.

3.5. CCL25 increases resistance to gemcitabine

Pancreatic cancer cell lines were treated with gemcitabine for 72 h, and the IC50 was determined. Cells were also treated with CCL25 for 6 h prior to 72‐h incubation with gemcitabine. Pre‐treatment with CCL25 increased the IC50 of gemcitabine 4.3‐fold (from 0.7 μM to 3.0 μM) in PANC‐1 cells, 6.0‐fold (from 0.2 μM to 1.2 μM) in MIAPaCa‐2, and 9.8‐fold (from 5.7 μM to 56.0 μM) in AsPC‐1 cells, indicating a dramatic decrease in the cytotoxicity of gemcitabine when cells were exposed to CCL25 (Figure 4C).

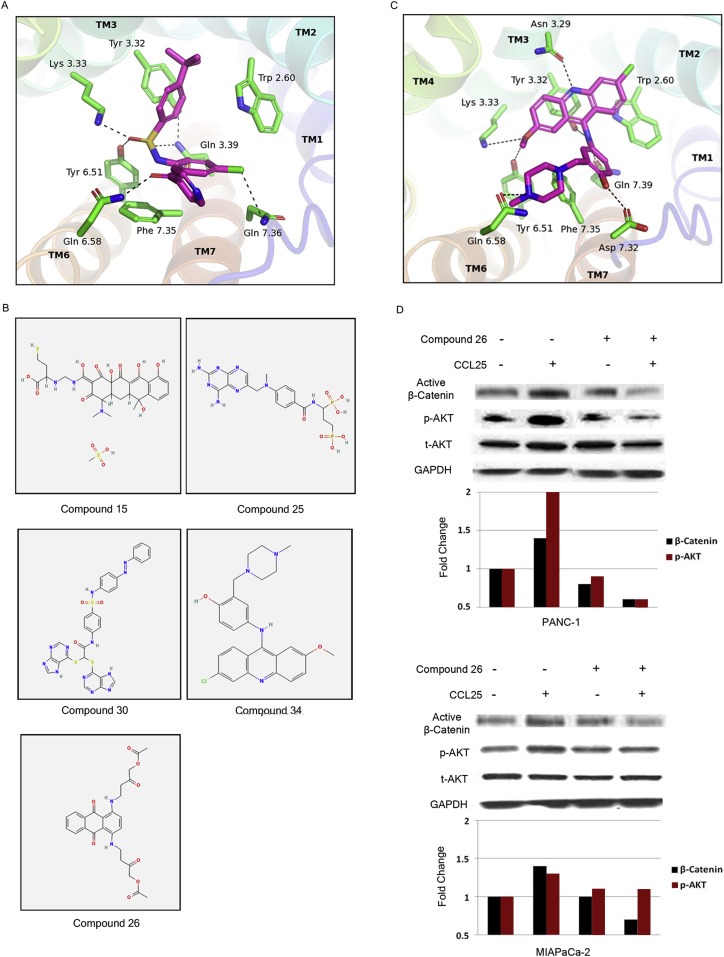

3.6. Computational modeling for CCR9 antagonist binding

Using techniques described above (Methods), we predicted the binding site of the CCR9 antagonist CCX282 and validated the predicted binding site using site‐directed mutagenesis data for antagonist binding in related chemokine receptors (Hall et al., 2009; Lam et al., 2011; Vaidehi et al., 2009). Figure 5A shows the predicted binding site of CCX282 at CCR9. The antagonist CCX282 binds between transmembrane (TM) helices TM3, TM6 and TM7, similar to the binding site of 1T1t in the CXCR4 crystal structure (Wu et al., 2010). According to our predicted structures, the important residues that contribute significantly to the binding energy of CCX282 are Trp1042.60, Tyr1263.32, Lys1273.33, Tyr2706.51, Asp2967.32, and Gln3047.39. Here we used the Ballesteros and Weinstein residue numbering scheme used for class A GPCRs (Ballesteros et al., 1995). These residues have been implicated in antagonist binding in CCR2 and CCR5 previously (Hall et al., 2009). The best docked structures of the 36 compounds that were screened for CCR9 were selected based on ligand binding energies as well as residue contacts with Trp1042.60, Tyr1263.32, Lys1273.33, Tyr2706.51, Asp2967.32, and Gln3037.39. After sorting by percentage of docked poses bound to Tyr1263.32, Lys1273.33, Tyr2706.51 or Asp2967.32, the nine most potent antagonists were selected.

Figure 5.

Computational modeling of CCR9. A) Predicted binding site of antagonist CCX282 and the residues of interaction in the CCR9 structural model. B) Five potent CCR9 antagonist compounds screened from the NCI small molecular compound library. C) Predicted binding site of Compound 26 in CCR9. D) Compound 26 inhibited CCL25‐mediated activation of β‐catenin and AKT. Cells were pre‐treated with Compound 26 for 5 min prior to exposure to CCL25 for 15 min.

3.7. Identification of a potent CCR9 antagonist

The compounds identified by virtual screening using the computational model of the CCR9 binding site were also screened for their ability to inhibit CCL25‐induced recruitment of β‐arrestin, since GPCRs are known to recruit β‐arrestin. Cells were pre‐treated with each compound prior to CCL25 stimulation and β‐arrestin recruitment was measured via luminescence using Tango assays. Signals for each compound were compared to CCL25 treatment alone and were presented as a percentage of CCL25‐mediated β‐arrestin recruitment. Five compounds (Compounds 15, 25, 26, 30, and 34) were identified as having the strongest inhibitory effect on β‐arrestin recruitment (80%, 90%, 90%, 80%, and 50%, respectively). The chemical structures of these five compounds are shown in Figure 5B.

Since calcium flux is initiated upon GPCR stimulation, we tested the candidate antagonists for their ability to inhibit calcium flux. In this assay cells were stimulated with either CCL25 alone or CCL25 with the candidate CCR9 antagonists at doses ranging from 3 to 300 μM. Then, the effect on calcium flux was assessed. The concentrations of each compound required to inhibit calcium flux by at least 50% were as follows: Compound 15 (10 μM), Compound 25 (30 μM), Compound 26 (10 μM), Compound 30 (30 μM), and Compound 34 (100 μM). Due to its combined superior inhibition of β‐arrestin recruitment and calcium flux, Compound 26 was further screened for CCR9 binding.

3.8. Compound 26 binds favorably to CCR9 and inhibits CCR9 signaling

Experimental screening of these compounds in a CCR9‐expressing cell line showed that Compound 26, which is also one of the nine top scoring compounds in the computational screening described above, showed the most potent inhibitory effect on CCR9. The predicted binding site of Compound 26 (shown in Figure 5C) is between TM2, TM3, TM6, and TM7. Residues Trp2.60, Gln7.39, Tyr3.32, and Lys3.33, which are known to contribute to antagonist binding in other CCR chemokine receptors (Hall et al., 2009; Vaidehi et al., 2009), also make strong contact with Compound 26. Therefore, Compound 26 was selected for in vitro studies to determine its ability to inhibit signaling pathways activated by CCR9. Accordingly, pancreatic cancer cells were treated with Compound 26 for 5 min prior to CCL25 exposure. Immunoblotting revealed that pretreatment with Compound 26 effectively blocked CCR9‐mediated activation of β‐catenin and AKT (Figure 5D).

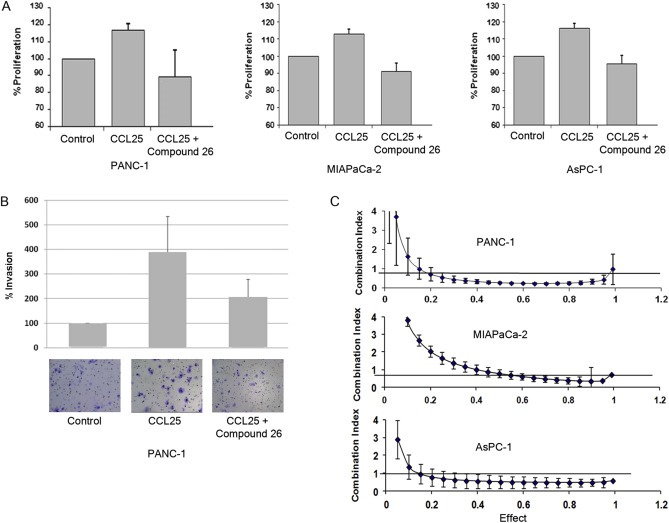

3.9. Compound 26 inhibits CCR9‐mediated proliferation and invasion

Given that Compound 26 inhibited CCL25‐induced signaling, we next determined if there was an effect on the cellular functions related to CCL25. In order to rule out intrinsic cytotoxicity of Compound 26, we performed a proliferation assay, which revealed no inhibition of growth (Supplementary Figure 2). We observed attenuated proliferation in cells co‐treated with Compound 26 (Figure 6A), an outcome similar to the effects with LY294002 (Figure 4A). We also observed a decrease in the invasion of CCL25‐treated PANC‐1 cells when co‐treated with Compound 26 (Figure 6B), similar to the effects of LY294002‐mediated antagonism of invasion (Figure 4B).

Figure 6.

Compound 26 antagonizes CCL25 receptor mediated signaling. A) PANC‐1, MIAPaCa‐2 and ASPC‐1 cells were pre‐treated with Compound 26 (4uM) for 5 min prior to CCL25 treatment and cell growth was measured after 72 h. B) Pre‐treatment of Compound 26 inhibited CCL25‐mediated invasion in PANC‐1 cells. C) Synergistic effects on cell death were observed with the combination of Compound 26 and gemcitabine.

3.10. Compound 26 interacts synergistically with gemcitabine to increase cytotoxicity

The effect of Compound 26 on drug sensitivity was measured in pancreatic cancer cells. All three pancreatic cancer cell lines, when treated with the combination of gemcitabine and Compound 26, revealed a synergistic increase in cytotoxicity with 72‐h treatment (Figure 6C). This data suggests that CCR9 antagonism may have a role in therapeutic targeting of pancreatic cancer.

4. Discussion

Since current treatment options for pancreatic cancer have marginal impact on long‐term outcomes, the identification of novel therapeutic targets remains paramount. Our current investigations have demonstrated that the CCR9/CCL25 axis not only promotes the growth and invasion of pancreatic cancer cells, but also importantly decreases the efficacy of cytotoxic agents. These study results suggest that the downstream effects of CCR9‐mediated signaling appear to be dependent on the PI3K/AKT pathway and the activation of β‐catenin. Building upon these initial findings, we used established computational methods and chemical library screening to identify Compound 26 as a potent CCR9 antagonist. We discovered that Compound 26 effectively inhibited CCR9‐mediated pancreatic cancer cell growth and invasion and synergistically enhanced the cytotoxicity of gemcitabine. These results highlight the potential important roles for CCR9 in pancreatic cancer invasiveness and in novel therapeutic targeting of pancreatic cancer.

Although CCR9 signaling regulates T‐cell proliferation, anti‐apoptosis, and mucosal immunity under normal physiologic conditions (Chen et al., 2012), it has been implicated in the mechanisms of tumor metastasis and in poor prognosis in a variety of human malignancies, including skin, ovarian, and breast cancers (Amersi et al., 2008; Johnson‐Holiday et al., 2011; Shen et al., 2009; Singh et al., 2011). In our own prior investigations we demonstrated high expression of CCR9 in pancreatic cancer cells and tissues (Heinrich et al., 2013; Shen et al., 2009). Here, we report highly novel findings regarding CCR9 signaling and its activation of β‐catenin in a PI3K/AKT‐dependent and Wnt‐independent manner. Indeed, the magnitude of increased active β‐catenin in our current studies is consistent with increases of active β‐catenin in other published reports (Kwon et al., 2011). Under typical conditions the Wnt pathway is activated when Wnt binds to the Frizzled receptor, ultimately leading to downstream dephosphorylation of β‐catenin. This active (dephosphorylated) form of β‐catenin translocates to the nucleus, increasing gene expression of its transcriptional targets. Our results showed that antagonism of Wnt did not block CCL25‐mediated activation of β‐catenin, suggesting that CCR9‐mediated signaling is independent of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. Previously, we also investigated the MAPK and JAK/STAT pathways as targets of the CCL25/CCR9 axis; and observed enhanced pancreatic cancer proliferation (Le et al., 2012). In future studies, we will explore whether cross‐talk between potent downstream pathways occurs with CCR9/β‐catenin signaling.

It is well known that β‐catenin promotes cell cycle progression through transcriptional upregulation of cell cycle regulatory genes (Davidson and Niehrs, 2010). In our current study, elevated β‐catenin signaling was associated with increased expression of cell cycle regulators, cyclin D1 and cyclin E1. Although β‐catenin is also involved in upholding the integrity of adherens junctions by its interactions with E‐cadherin (Valenta et al., 2012), our study did not show a corresponding decrease in E‐cadherin expression concurrent with increased active β‐catenin in response to CCL25 treatment. Instead, we observed that E‐cadherin expression slightly increased within 30 min after CCL25 treatment (Figure 3D‐right). These findings are consistent with a recent report showing elevated E‐cadherin expression along with high levels of β‐catenin expression in pancreatic cancer (Zeng et al., 2006).

The prognosis for patients with pancreatic cancer remains dismal even with current chemotherapy regimens. Gemcitabine is frequently used for pancreatic cancer, but it has little impact on survival (Louvet et al., 2005; Oettle et al., 2007); and all patients eventually develop resistance to the drug (Shah et al., 2007). In this study we discovered that exposure of pancreatic cancer cells to CCL25 decreased the cytotoxic response to gemcitabine, suggesting that CCR9 signaling may contribute to chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. Interestingly, Shah and colleagues reported that resistance to gemcitabine correlated with increased nuclear localization of β‐catenin (Shah et al., 2007). Although it was not examined here, other studies have identified β‐catenin activity in cancer stem cells (CSCs) as the potential mechanism for chemoresistance (Li and Zhou, 2011; Rogers et al., 2012; Vermeulen et al., 2010). Nevertheless, our results are consistent with the prior reports that CCR9‐mediated activation of β‐catenin promotes chemoresistance. Our results provide sufficient evidence that CCR9 signaling is a promising therapeutic target.

Because there is no published crystal structure for CCR9, we used our prior experience with computational modeling of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 combined with high throughput screening methods (Kim et al.) to create a model of this receptor and its binding site to identify potential CCR9 antagonists. To test the efficacy of these compounds, we assessed their antagonism of canonical GPCR‐mediated cellular events, including calcium mobilization and recruitment of β‐arrestin. Using this systematic approach, we identified several promising small molecule compounds that were structurally distinct from a previously reported CCR9 antagonist (2012). We identified Compound 26 as the most potent antagonist, effectively blocking CCL25‐mediated β‐catenin activation, cell proliferation, and invasion. Perhaps more important clinically, we observed that Compound 26 synergistically increased the cytotoxicity of gemcitabine in pancreatic cancer cells. Future studies will be necessary to optimize the delivery of Compound 26 in vivo.

In conclusion, our studies have uncovered a highly novel molecular pathway from CCR9‐mediated signaling to the activation of β‐catenin. This activated signaling pathway has great implications for our understanding of cancer invasion mechanisms, but also for the clinical management of pancreatic cancer. The identification of a novel CCR9 antagonist may present an innovative, therapeutic strategy for patients with pancreatic cancer.

Authors contributions

Conception and Design by SL, ELH, NV and JK; Development of Methodology by SL ELH, RL, JEW, RY, NV and JK; Acquisition of Data by SL, ELH, LL, JL, NV and JK; Analysis and Interpretation of Data by SL, ELH, JL, AHC, RL, JEW, NV and JK; Writing, Review, and Revision by SL, ELH, LL, AHC, NV and JK; Study Supervision by JK. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

None to report.

Supporting information

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Research Scholar Grant (120687‐RSG‐11‐070‐01‐TBE from the American Cancer Society. Additional financial support was provided by the City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30 CA33572‐27).

Supplementary data 1.

1.1.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molonc.2015.04.012.

Lee Sangjun, Heinrich Eileen L., Li Lily, Lu Jianming, Choi Audrey H., Levy Rachel A., Wagner Jeffrey E., Yip M.L. Richard, Vaidehi Nagarajan, Kim Joseph, (2015), CCR9‐mediated signaling through β‐catenin and identification of a novel CCR9 antagonist, Molecular Oncology, 9, doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2015.04.012.

References

- 2012. CCR9 Program – Overview. http://www.chemocentryx.com/about/overview.html.

- Al-Aynati, M.M. , Radulovich, N. , Riddell, R.H. , Tsao, M.S. , 2004. Epithelial-cadherin and beta-catenin expression changes in pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 10, 1235–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amersi, F.F. , Terando, A.M. , Goto, Y. , Scolyer, R.A. , Thompson, J.F. , Tran, A.N. , Faries, M.B. , Morton, D.L. , Hoon, D.S. , 2008. Activation of CCR9/CCL25 in cutaneous melanoma mediates preferential metastasis to the small intestine. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 14, 638–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros, J.A. , Weinstein, H. , Stuart, C.S. , 1995. [19] Integrated Methods for the Construction of Three-dimensional Models and Computational Probing of Structure-function Relations in G Protein-coupled Receptors, Methods in Neurosciences Academic Press; 366–428. [Google Scholar]

- Berendsen, H.J.C. , van der Spoel, D. , van Drunen, R. , 1995. GROMACS: a message-passing parallel molecular dynamics implementation. Computer Phys. Commun. 91, 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Botrugno, O.A. , Fayard, E. , Annicotte, J.S. , Haby, C. , Brennan, T. , Wendling, O. , Tanaka, T. , Kodama, T. , Thomas, W. , Auwerx, J. , Schoonjans, K. , 2004. Synergy between LRH-1 and beta-catenin induces G1 cyclin-mediated cell proliferation. Mol. Cel. 15, 499–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.J. , Edwards, R. , Tucci, S. , Bu, P. , Milsom, J. , Lee, S. , Edelmann, W. , Gumus, Z.H. , Shen, X. , Lipkin, S. , 2012. Chemokine 25-induced signaling suppresses colon cancer invasion and metastasis. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 3184–3196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, G. , Niehrs, C. , 2010. Emerging links between CDK cell cycle regulators and Wnt signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 20, 453–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froeling, F.E. , Feig, C. , Chelala, C. , Dobson, R. , Mein, C.E. , Tuveson, D.A. , Clevers, H. , Hart, I.R. , Kocher, H.M. , 2011. Retinoic acid-induced pancreatic stellate cell quiescence reduces paracrine Wnt-beta-catenin signaling to slow tumor progression. Gastroenterology. 141, 1486–1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, S.E. , Mao, A. , Nicolaidou, V. , Finelli, M. , Wise, E.L. , Nedjai, B. , Kanjanapangka, J. , Harirchian, P. , Chen, D. , Selchau, V. , Ribeiro, S. , Schyler, S. , Pease, J.E. , Horuk, R. , Vaidehi, N. , 2009. Elucidation of binding sites of dual antagonists in the human chemokine receptors CCR2 and CCR5. Mol. Pharmacol. 75, 1325–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, E.L. , Arrington, A.K. , Ko, M.E. , Luu, C. , Lee, W. , Lu, J. , Kim, J. , 2013. Paracrine activation of chemokine receptor CCR9 enhances the invasiveness of pancreatic Cancer cells. Cancer Microenviron. 6, 241–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Holiday, C. , Singh, R. , Johnson, E. , Singh, S. , Stockard, C.R. , Grizzle, W.E. , Lillard, J.W. , 2011. CCL25 mediates migration, invasion and matrix metalloproteinase expression by breast cancer cells in a CCR9-dependent fashion. Int. J. Oncol. 38, 1279–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuta, K. , Masamune, A. , Watanabe, T. , Ariga, H. , Itoh, H. , Hamada, S. , Satoh, K. , Egawa, S. , Unno, M. , Shimosegawa, T. , 2010. Pancreatic stellate cells promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 403, 380–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. , Yip, M.L. , Shen, X. , Li, H. , Hsin, L.Y. , Labarge, S. , Heinrich, E.L. , Lee, W. , Lu, J. , Vaidehi, N. , 2012. Identification of anti-malarial compounds as novel antagonists to chemokine receptor CXCR4 in pancreatic cancer cells. PLoS One. 7, e31004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, C. , Cheng, P. , King, I.N. , Andersen, P. , Shenje, L. , Nigam, V. , Srivastava, D. , 2011. Notch post-translationally regulates beta-catenin protein in stem and progenitor cells. Nat. Cel. Biol. 13, 1244–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam, A.R. , Bhattacharya, S. , Patel, K. , Hall, S.E. , Mao, A. , Vaidehi, N. , 2011. Importance of receptor flexibility in binding of cyclam compounds to the chemokine receptor CXCR4. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 51, 139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin, M.A. , Blackshields, G. , Brown, N.P. , Chenna, R. , McGettigan, P.A. , McWilliam, H. , Valentin, F. , Wallace, I.M. , Wilm, A. , Lopez, R. , Thompson, J.D. , Gibson, T.J. , Higgins, D.G. , 2007. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). 23, 2947–2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le, Maithao N. , S., X. , Lee, Wendy , Duldulao, Marjun Philip , Garcia-Aguilar, Julio , Kim, Joseph , 2012. Paradoxical cross-talk between the Stat3 and MAPK pathways in CCL25-CCR9 mediated pancreatic cancer growth and proliferation. J. Clin. Oncol. 30, (Suppl. 4) (abstr 231) [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. , Zhou, B.P. , 2011. Activation of beta-catenin and Akt pathways by Twist are critical for the maintenance of EMT associated cancer stem cell-like characters. BMC Cancer. 11, 49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.J. , Wei, Z.M. , Meng, Y.X. , Ji, X.R. , 2005. Beta-catenin up-regulates the expression of cyclinD1, c-myc and MMP-7 in human pancreatic cancer: relationships with carcinogenesis and metastasis. World J. Gastroenterol. 11, 2117–2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louvet, C. , Labianca, R. , Hammel, P. , Lledo, G. , Zampino, M.G. , Andre, T. , Zaniboni, A. , Ducreux, M. , Aitini, E. , Taieb, J. , Faroux, R. , Lepere, C. , de Gramont, A. , 2005. Gemcitabine in combination with oxaliplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: results of a GERCOR and GISCAD phase III trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 23, 3509–3516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masyuk, M. , Brand-Saberi, B. , 2015. Recruitment of skeletal muscle progenitors to secondary sites: a role for CXCR4/SDF-1 signalling in skeletal muscle development. Results Probl. Cel. Differ. 56, 1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris, J.P.t. , Wang, S.C. , Hebrok, M. , 2010. KRAS, Hedgehog, Wnt and the twisted developmental biology of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 10, 683–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oettle, H. , Post, S. , Neuhaus, P. , Gellert, K. , Langrehr, J. , Ridwelski, K. , Schramm, H. , Fahlke, J. , Zuelke, C. , Burkart, C. , Gutberlet, K. , Kettner, E. , Schmalenberg, H. , Weigang-Koehler, K. , Bechstein, W.O. , Niedergethmann, M. , Schmidt-Wolf, I. , Roll, L. , Doerken, B. , Riess, H. , 2007. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine vs observation in patients undergoing curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 297, 267–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, H.A. , Sousa, S. , Salto, C. , Arenas, E. , Coyle, B. , Grundy, R.G. , 2012. WNT/beta-catenin pathway activation in Myc immortalised cerebellar progenitor cells inhibits neuronal differentiation and generates tumours resembling medulloblastoma. Br. J. Cancer. 107, 1144–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sali, A. , Blundell, T.L. , 1993. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 234, 779–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah, A.N. , Summy, J.M. , Zhang, J. , Park, S.I. , Parikh, N.U. , Gallick, G.E. , 2007. Development and characterization of gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic tumor cells. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 14, 3629–3637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, X. , Mailey, B. , Ellenhorn, J.D. , Chu, P.G. , Lowy, A.M. , Kim, J. , 2009. CC chemokine receptor 9 enhances proliferation in pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and pancreatic cancer cells. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 13, 1955–1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R. , Stockard, C.R. , Grizzle, W.E. , Lillard, J.W. , Singh, S. , 2011. Expression and histopathological correlation of CCR9 and CCL25 in ovarian cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 39, 373–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidehi, N. , Pease, J.E. , Horuk, R. , 2009. Modeling small molecule-compound binding to G-protein-coupled receptors. Methods Enzymol. 460, 263–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenta, T. , Hausmann, G. , Basler, K. , 2012. The many faces and functions of beta-catenin. EMBO J. 31, 2714–2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen, L. , De Sousa, E.M.F. , van der Heijden, M. , Cameron, K. , de Jong, J.H. , Borovski, T. , Tuynman, J.B. , Todaro, M. , Merz, C. , Rodermond, H. , Sprick, M.R. , Kemper, K. , Richel, D.J. , Stassi, G. , Medema, J.P. , 2010. Wnt activity defines colon cancer stem cells and is regulated by the microenvironment. Nat. Cel. Biol. 12, 468–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicari, A.P. , Figueroa, D.J. , Hedrick, J.A. , Foster, J.S. , Singh, K.P. , Menon, S. , Copeland, N.G. , Gilbert, D.J. , Jenkins, N.A. , Bacon, K.B. , Zlotnik, A. , 1997. TECK: a novel CC chemokine specifically expressed by thymic dendritic cells and potentially involved in T cell development. Immunity. 7, 291–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlad, A. , Rohrs, S. , Klein-Hitpass, L. , Muller, O. , 2008. The first five years of the Wnt targetome. Cell Signal. 20, 795–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B. , Chien, E.Y. , Mol, C.D. , Fenalti, G. , Liu, W. , Katritch, V. , Abagyan, R. , Brooun, A. , Wells, P. , Bi, F.C. , Hamel, D.J. , Kuhn, P. , Handel, T.M. , Cherezov, V. , Stevens, R.C. , 2010. Structures of the CXCR4 chemokine GPCR with small-molecule and cyclic peptide antagonists. Science (New York, N.Y.). 330, 1066–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youn, B.S. , Kim, Y.J. , Mantel, C. , Yu, K.Y. , Broxmeyer, H.E. , 2001. Blocking of c-FLIP(L)–independent cycloheximide-induced apoptosis or Fas-mediated apoptosis by the CC chemokine receptor 9/TECK interaction. Blood. 98, 925–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaballos, A. , Gutierrez, J. , Varona, R. , Ardavin, C. , Marquez, G. , 1999. Cutting edge: identification of the orphan chemokine receptor GPR-9-6 as CCR9, the receptor for the chemokine TECK. J. Immunol. 162, 5671–5675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, G. , Germinaro, M. , Micsenyi, A. , Monga, N.K. , Bell, A. , Sood, A. , Malhotra, V. , Sood, N. , Midda, V. , Monga, D.K. , Kokkinakis, D.M. , Monga, S.P. , 2006. Aberrant Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Neoplasia (New York, N.Y.). 8, 279–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnik, A. , Burkhardt, A.M. , Homey, B. , 2011. Homeostatic chemokine receptors and organ-specific metastasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 11, 597–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

Supplementary data

Supplementary data