Abstract

Iterative structure–activity analyses in a class of highly functionalized furo[2,3-b]pyridines led to the identification of the second generation pan-genotypic hepatitis C virus NS5B polymerase primer grip inhibitor BMT-052 (14), a potential clinical candidate. The key challenge of poor metabolic stability was overcome by strategic incorporation of deuterium at potential metabolic soft spots. The preclinical profile and status of BMT-052 (14) is described.

Keywords: Hepatitis C virus, azabenzofuran, NS5B polymerase, primer grip, deuterium, metabolic stability

There are an estimated 130–150 million people chronically infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) worldwide.1 The prevalence of HCV infection varies throughout the world with an estimated 3.2 million individuals infected within the United States and even larger population percentages in Africa and Asia.2 There are seven major genotypes (1–7) and five subclasses (a–e) of HCV, all of which vary globally.3−5 The standard of care has rapidly evolved over the past few years as a result of recent approvals of new direct acting antivirals and combination therapies.6 The appropriate treatment regimen and duration can vary depending on the patient’s viral genotype.6 One overarching goal is to have a single treatment regimen that is effective across all genotypes. To that end, second generation pan-genotypic NS5B polymerase inhibitors could be an important part of an ideal regimen.

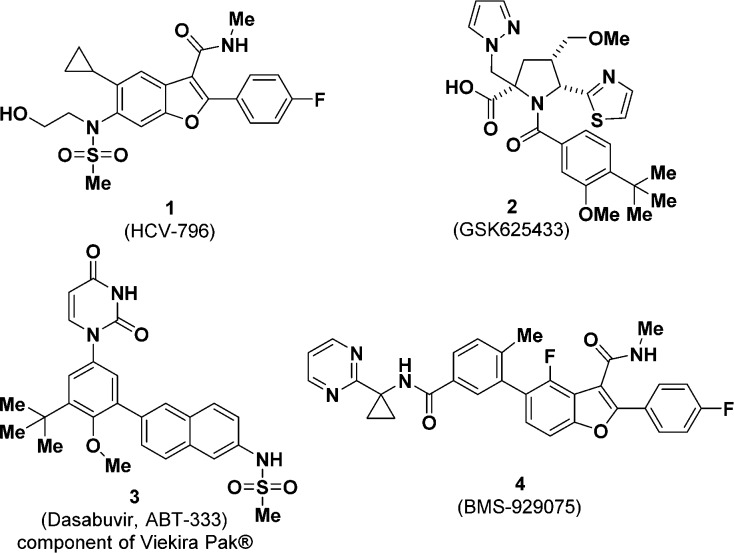

NS5B polymerase is essential for viral replication and contains three main domains (thumb, palm, and fingers) and four allosteric sites (thumb-I, thumb-II, palm-I, and palm-II).7 The two overlapping palm binding sites span a relatively large area that extends across the palm to the interior of the thumb domain and encompasses part of the active site.8 Inhibitors binding to this area, often referred to as the primer grip, can be characterized by varying degrees of resistance to mutated residues at 414, 316, or 447.8 Due to the size of the area (15 Å wide and 20 Å deep) a diverse variety of chemotypes are tolerated (Figure 1).7

Figure 1.

Literature examples of first generation palm inhibitors of HCV NS5B polymerase.8,9

Several recent publications have described some of our efforts in this area, documenting the progression of compounds from HTS leads through first generation compounds (BMS-929075) to the second generation pan-genotypic inhibitor BMS-986139 (5).9−11 The development of 5 was halted do to unexpected microcrystallization in multiple tissues at elevated doses in both rats and dogs in investigational new drug (IND) toxicology studies. Herein we report the efforts to identify a back-up candidate to 5.

The initial structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies began with modifications to the C5 phenyl ring of 5, as summarized in Table 1. The screening paradigm used to evaluate analogues involved measuring the replicon inhibitory activity against genotype (GT) 1a, 1b, 2a, and the 1b existing mutant C316N. For the purposes of this discussion, only GT 1a and GT 1a in the presence of 40% human serum (1aHS) will be discussed since the antiviral activity of all compounds described expressed EC50 values toward GT 1b, 2a replicons, and the GT 1b 316N mutant of <15 nM.13

Table 1. C5 Modifications of BMS-986139 (5).

Half-lives determined using liver microsomes in the presence of NADPH.

GT 1a in the presence of 40% human serum.

Compared to 5, fluorine-containing C5s maintained intrinsic potency but led to decreased 1aHS activity (6 and 7), while the methoxy and methoxy pyridine analogues 8 and 10, respectively, had improved GT 1a and 1aHS activity. However, the human and cynomolgus monkey (cyno) liver microsomes (LMs) metabolic half-lives of 8 and 10 were shortened. This led us to investigate ways of improving the metabolic stability while maintaining the virology profile. It was determined that transposing the methyl group from the oxygen to the nitrogen (10 to 12) maintained 1aHS activity and improved stability in HLM significantly, as represented by compound 12. Unfortunately, 12 was shown to be a potent competitive inhibitor of CYP3A4 (IC50 = 0.44 μM) and was not pursued further.

Based on the possibility that the MeO moieties of 8 and 10 may be metabolically labile, another potential pathway toward improving the metabolic stability was explored, which involved harnessing the ability of deuterium to alter a compound’s metabolic liabilities while maintaining its inherent biological activity.14,15 Due to the deuterium kinetic isotope effect, the carbon-deuterium bond is more stable than a carbon–hydrogen bond, which leads to decreased kinetic rates of metabolism of ∼6–10-fold when bond breakage is the rate limiting step.15 The heavier isotope has a lower vibrational frequency and thus larger amounts of energy are required to break the bond.16 Moreover, deuterium has similar electron clouds, and polar surface areas resulting in molecules with biochemical activity and selectivity largely comparable to their hydrogen parents.15 Ultimately, this made deuterium an attractive hydrogen bioisostere to evaluate. Therefore, modifications to the methoxy groups of 8 and 10 were made by incorporating deuterium, affording compounds 9 and 11, respectively. In each case, there was a modest improvement in metabolic stability determined in both human and cyno LMs. We proceeded to investigate further by incorporating deuterium into the oxadiazole ring (13) as well as into the gem-dimethyl moiety (14 and 15) based on the potential for oxidative metabolism to occur at these sites, and the results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Deuterium Incorporation into the Oxadiazole Amide.

Half-lives determined using liver microsomes in the presence of NADPH.

GT 1a in the presence of 40% human serum.

While compound 13 provided no advantage in metabolic stability compared to 11, this strategy afforded compounds 14 (BMT-052) and 15 both of which exhibited further improvements in metabolic stability in human and cyno LMs. In order to ensure that deuterium was necessary in both the amide moiety as well as C5, several C5 derivatives were re-evaluated in the context of the gem-dimethyl-d6 oxadiazole amide, and the results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. C5 Modifications of BMT-052 (14).

Half-lives determined using liver microsomes in the presence of NADPH.

GT 1a in the presence of 40% human serum.

When comparing compounds 17, 18, and 19 to their proto gem-dimethyl oxadiazole counterparts 8, 9, and 10, respectively, it was evident that the gem-dimethyl-d6 oxadiazole alone is not sufficient to address the poor metabolic stability in human LMs. Compound 16 had a suitable metabolic stability profile but led to decreased activity toward 1aHS, leaving both 14 and 15 with the best balance of biological activity and metabolic stability. Since 15 was more synthetically challenging and offered only modest improvements in metabolic stability, attention was directed toward 14 (BMT-052), which was investigated in further detail. Compound 14 had good genotype coverage with the least sensitive virus being the existing 1b C316N mutant where the EC50 value was 7 nM, as summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. Genotype Coverage of BMT-052 (14).

IC50.

The pharmacokinetic (PK) properties of 14 were evaluated in three preclinical species: rat, dog, and cyno, and the results are summarized in Table 5. Compound 14 exhibited low clearance (Cl), a moderate volume of distribution (Vss), and good oral bioavailability (F%) across the species. The overall profile of 14 supported a low projected human dose consistent with once daily (QD) dosing similar to that of 5 (35 mg QD).11

Table 5. Preclinical PK Properties of BMT-052 (14).

| dose (mg/kg) |

t1/2 (h) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| species | IVa | POb | Cl (mL/min/kg) | Vss (L/kg) | IV | PO | PO AUC (μM h) | F % |

| rat | 2 | 6 | 1.6 | 11 | 79 | 76 | 95 | 100 |

| dog | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2.1 | 18 | >48 | 125 | 90 |

| cyno | 1 | 3 | 4.7 | 2.3 | 6.3 | 10 | 16 | 85 |

Dose formulations: PEG 400/ethanol (90:10).

Dose formulations: PEG 400/ethanol/vitamin E TPGS (90:5:5).

When comparing 5 and 14, both the antiviral profiles and preclinical PK properties led to a similar human dose projection. However, the physiochemical properties of 14 showed improvements over 5. Compound 14 has both a lower measured log D at pH 6.5 (3.73) and a lower melting point (177 °C) when compared to 5 (log D = 4.43, mp = 241 °C, respectively). The solubility of 5 and 14 were evaluated in a range of media, and the data are summarized in Figure 2. While there was little difference observed between the two compounds in phosphate buffer and fasted state simulated intestinal fluid (FaSSIF), 14 had an improved solubility in fed state simulated intestinal fluid (FeSSIF) at both pH 6.5 and 5 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Solubility of 14 vs 5.

Both the improvements in solubility and physiochemical properties of 14 provides a potential means of overcoming the microcrystallization problems observed during the IND toxicology studies of 5.

The chemistry used to prepare 14 involved independently preparing both the C5 and amide moieties. The C5 methoxy-d3 pyridine synthesis is summarized in Scheme 1. The commercially available chloropyridine 20 was treated with sodium dissolved in methanol-d4, which afforded 21. Compound 21 was then subjected to standard Miyaura borylation reaction conditions yielding compound 22.

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) Na, MeOH-d4, 76%; (b) bis(pinacolato)diboron, Pd(dppf)Cl2, KOAc, dioxane, 80 °C, 91%.

The synthesis of the gem-dimethyl-d6 oxadiazole is summarized in Scheme 2. Acetone-d6 was treated with TMSCN in the presence of TiOEt4 and (R)-2-methylpropane-2-sulfinamide (23) to afford compound 24, which was then treated with hydroxylamine hydrochloride and potassium carbonate to give compound 25. The oxadiazole 26 was formed upon treatment of 25 with acetic acid in triethoxymethane. Finally, deprotection of 26 with acid revealed the amine salt 27.

Scheme 2.

Reagents and conditions: (a) acetone-d6, TiOEt4, TMSCN, DCM, 40 °C, 58%; (b) H2NOH·HCl, K2CO3, EtOH, 60 °C, 60%; (c) triethyl orthoformate, AcOH, 80%; (d) HCl, MeOH, 80%.

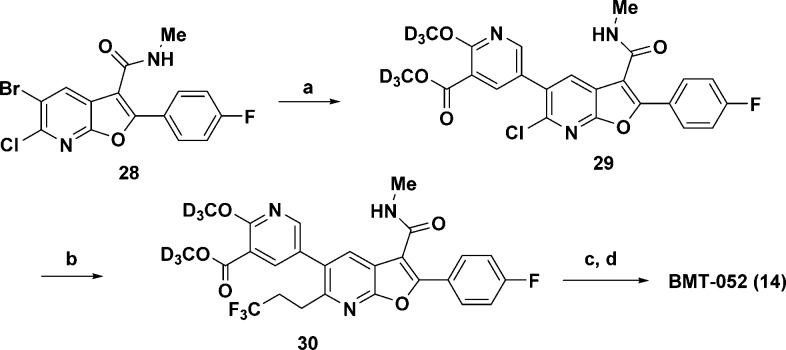

Compound 14 was assembled by first selectively coupling the 7-azabenzofuran 28(17) with 22 under standard Suzuki conditions. A subsequent Suzuki reaction with the Molander salt 3,3,3-trifluoropropane-1-trifluoroborate afforded 30 (Scheme 3). After saponification of the ester and amide coupling, 14 was realized in 35% yield over four steps.

Scheme 3.

Reagents and conditions: (a) 22, Pd(dppf)Cl2, Cs2CO3, DMF, H2O, 55 °C, 54%; (b) potassium 3,3,3-trifluoropropane-1-trifluoroborate, RuPhos, Pd(OAc)2, Cs2CO3, toluene, H2O, 80 °C, 77%; (c) NaOH, MeOH, THF, 98%; (d) 27, HATU, DIPEA, DMF, 85%.

In conclusion, through iterative SAR studies and systematically incorporating deuterium into both the C5 and amide substituents, the promising preclinical compound 14 was identified. Compound 14 expressed potent, pan-genotype HCV inhibition, a PK profile predictive of QD dosing in humans and improved physiochemical properties compared to 5. Empirically, in this context we have shown the ability of deuterium to reduced metabolic rates in LMs as evident by the longer recorded half-lives.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- IND

investigational new drug

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

- GT

genotype

- 1aHS

1a in the presence of 40% human serum

- cyno

cynomolgus monkey

- LMs

liver microsomes

- PK

pharmacokinetic

- Cl

clearance

- Vss

volume of distribution

- F%

oral bioavailability

- QD

once daily

- FaSSIF

fasted state simulated intestinal fluid

- FeSSIF

fed state simulated intestinal fluid

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.7b00211.

Experimental protocols and characterization data (PDF)

Author Present Address

† ViiV Healthcare, 5 Research Parkway, c/o Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Wallingford, Connecticut 06492, United States

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- World Health Organization Hepatitis C fact sheet. Updated July 2016. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs164/en/ (accessed 4/19/17).

- Averhoff F. M.; Glass N.; Holtzman D. Global burden of hepatitis C: considerations for healthcare providers in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 55 (Suppl 1), S10–S15. 10.1093/cid/cis361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis G. L. Hepatitis C virus genotypes and quasispecies. Am. J. Med. 1999, 107, 21S–26S. 10.1016/S0002-9343(99)00376-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandres-Saune K.; Deny P.; Pasquier C.; Thibaut V.; Du verlie G.; Izopet J. Determining hepatitis C genotype by analyzing the sequence of the NS5b region. J. Virol. Methods 2003, 109, 187–193. 10.1016/S0166-0934(03)00070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy D. G.; Sablon E.; Chamberland J.; Fournier E.; Dandavino R.; Tremblay C. L. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 967–972. 10.1128/JCM.02831-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Nguyen D.; Hu K.-Q. Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection: A Review of Current Direct Acting Antiviral Treatment Strategies. N Am. J. Med. Sci. (Boston) 2016, 9, 47–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenaux M.; Mo H. NS5B polymerase non-nucleoside inhibitors. Hepatitis C 2011, 311–320. [Google Scholar]

- Sofia M. J.; Chang W.; Furman P. A.; Mosley R. T.; Ross B. S. Nucleoside, Nucleotide, and Non-Nucleoside Inhibitors of Hepatitis C Virus NS5B RNA-Dependent RNA-Polymerase. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 2481–2531. 10.1021/jm201384j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung K.-S.; Beno B. R.; Parcella K.; Bender J. A.; Grant-Young K. A.; Nickel A.; Gunaga P.; Anjanappa P.; Rajesh Bora O.; Selvakumar K.; Rigat K.; Wang Y.-K.; Liu M.; Lemm J.; Mosure K.; Sheriff S.; Wan C.; Witmer M.; Kish K.; Hanumegowda U.; Zhuo X.; Shu Y.-Z.; Parker D.; Roy Haskell R.; Ng A.; Gao Q.; Colston E.; Raybon J.; Grasela D. M.; Santone K.; Gao M.; Meanwell N. A.; Sinz M.; Soars M. G.; Knipe J. O.; Roberts S. B.; Kadow J. F. Discovery of BMS-929075 an HCV NS5B Replicase Palm Site Allosteric Inhibitor Advanced to Phase 1 Clinical Studies. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 4369–4385. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parcella K.; Nickel A.; Beno B. R.; Sheriff S.; Wan C.; Wang Y.-K.; Roberts S. B.; Meanwell N. A.; Kadow J. F. Discovery and initial optimization of alkoxyanthranilic acid derivatives as inhibitors of HCV NS5B polymerase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 295–298. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastman K. J.; Parcella K.; Yeung K.-S.; Grant-Young K. A.; Zhu J.; Wang T.; Zhang Z.; Yin Z.; Beno B. R.; Sheriff S.; Kish K.; Tredup J.; Jardel A. G.; Halan V.; Ghosh K.; Parker D.; Mosure K.; Fang H.; Wang Y.-K.; Lemm J.; Zhuo X.; Hanumegowda U.; Rigat K.; Donoso M.; Tuttle M.; Zvyaga T.; Haarhoff Z.; Meanwell N. A.; Soars M. G.; Roberts S. B.; Kadow J. F. The discovery of a pan-genotypic, primer grip inhibitor of HCV NS5B polymerase. MedChemComm 2017, 8, 796–806. 10.1039/C6MD00636A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EC50 values are an average value of n ≥ 2 independent experiments and were determined in a HCV replicon luciferase whole cell assay, as described in the Supporting Information.

- Eastman K.; Parcella K.; Kadow J. US Patent 20140275154.

- Katsnelson A. Heavy drugs draw heavy interest from pharma backers. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 656. 10.1038/nm0613-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung R. The Development of Deuterium-Containing Drugs. www.concertpharma.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/IPT-0310.pdf (accessed 7/15/15).

- Gant T. G. Using Deuterium in Drug Discovery; Leaving the Label in the Drug. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 3595–3611. 10.1021/jm4007998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The preparation of compound 28 is described in reference (11).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.