Abstract

Objective

Advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a lethal malignancy with limited treatment options. Palbociclib, a well-tolerated and selective CDK4/6 inhibitor, has shown promising results in the treatment of retinoblastoma (RB1)-positive breast cancer. RB1 is rarely mutated in HCC, suggesting that palbociclib could potentially be used for HCC therapy. Here, we provide a comprehensive characterisation of the efficacy of palbociclib in multiple preclinical models of HCC.

Design

The effects of palbociclib on cell proliferation, cellular senescence and cell death were investigated in a panel of human liver cancer cell lines, in ex vivo human HCC samples, in a genetically engineered mouse model of liver cancer, and in human HCC xenografts in vivo. The mechanisms of intrinsic and acquired resistance to palbociclib were assessed in human liver cancer cell lines and human HCC samples by protein and gene expression analyses.

Results

Palbociclib suppressed cell proliferation in human liver cancer cell lines by promoting a reversible cell cycle arrest. Intrinsic and acquired resistance to palbociclib was determined by loss of RB1. A signature of ‘RB1 loss of function’ was found in <30% of HCC samples. Palbociclib, alone or combined with sorafenib, the standard of care for HCC, impaired tumour growth in vivo and significantly increased survival.

Conclusions

Palbociclib shows encouraging results in preclinical models of HCC and represents a novel therapeutic strategy for HCC treatment, alone or particularly in combination with sorafenib. Palbociclib could potentially benefit patients with RB1-proficient tumours, which account for 70% of all patients with HCC.

Keywords: HEPATOCELLULAR CARCINOMA, CELL CYCLE

Significance of this study.

What is already known on this subject?

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. The only US Food and Drug Administration-approved targeted therapy for advanced HCC patients is the multikinase inhibitor sorafenib, which offers limited survival benefits.

Palbociclib is a selective CDK4/6 inhibitor that has demonstrated outstanding results in phase II clinical trials of oestrogen receptor (ER)-positive HER2-negative breast cancer in combination with ER inhibitors. There is an ongoing phase II clinical trial in HCC as second-line therapy after sorafenib failure.

A comprehensive study in preclinical models testing the potential of palbociclib for HCC treatment, combined or as a single agent, is lacking.

What are the new findings?

Palbociclib is effective in human liver cancer cell lines in vitro, in ex vivo HCC samples, in a genetically engineered mouse model of liver cancer and in human HCC xenografts in vivo.

Palbociclib induces a reversible cell cycle arrest, which indicates that the current dosing schedule (3 weeks of treatment, 1 week of drug holiday) may not be optimal for HCC therapy.

Intrinsic and acquired resistance to palbociclib is marked by loss of functional retinoblastoma (RB1), and an ‘RB1 loss of function’ signature could potentially be used as a biomarker of non-response.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

Our study represents the most extensive preclinical characterisation of palbociclib for HCC treatment to date and supports its clinical development, alone or in combination with sorafenib. Further studies will optimise patient target selection as well as the best treatment combinations.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a very aggressive disease and represents the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide.1 2 Although treatment of HCC has greatly improved over the last decade, most HCC patients diagnosed at advanced stages are ineligible for curative ablative therapies such as liver resection, liver transplantation or local ablation.3 The multikinase inhibitor sorafenib remains the only approved systemic drug for these patients; however, their median life expectancy is restricted to 1 year.4 Other molecular therapies targeting signalling cascades involved in HCC have rendered negative results,3 emphasising the urgent need for alternative therapeutic strategies with improved potency.

Cell cycle control is frequently disrupted in cancer,5 and as a consequence, cell cycle inhibitors constitute an attractive therapeutic option.6 Several selective cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 (CDK4/6) inhibitors have been developed in the last decade: abemaciclib (LY2835219; Elli Lilly), ribociclib (LEE011; Novartis) and palbociclib (PD0332991, Ibrance; Pfizer).7 Among them, palbociclib was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for breast cancer treatment, after impressive improvement in progression-free survival in phase II clinical trials of oestrogen receptor (ER)-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer, in combination with letrozole or fulvestrant.8 9 Palbociclib presents tolerable toxicity (mostly neutropenia and thrombocytopenia)10 11 and is predicted to be efficacious in those tumour types, such as HCC, that frequently harbour an intact retinoblastoma (RB1).1 6 12 Despite promising data, the potential of palbociclib for HCC treatment has not been extensively analysed in preclinical models of HCC.

Here, we provide a comprehensive preclinical evaluation of palbociclib activity in HCC. Treatment with palbociclib induced a reversible cell cycle arrest that depended on an intact RB1. A signature of ‘RB1 loss of function’ was found in <30% of HCC patients, which are predicted to be non-responders. Moreover, palbociclib behaved as efficiently as sorafenib in vivo and their combination, which was well tolerated, offered superior results. Taken together, our study provides preclinical evidence supporting clinical trials to evaluate the potential of palbociclib, alone or in combination with sorafenib, for HCC treatment.

Results

Palbociclib inhibits growth of human liver cancer cell lines

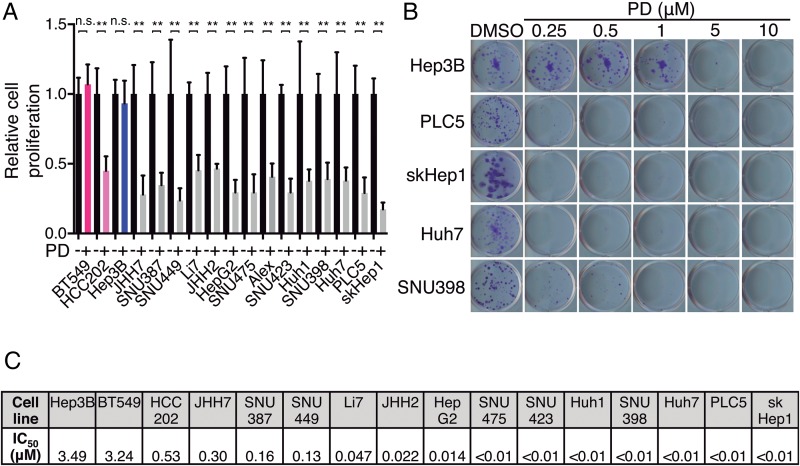

To evaluate the potential of palbociclib for HCC treatment, we first tested the effect of palbociclib in a comprehensive panel of human liver cancer cell lines representative of a range of HCC patient subclasses.13 14 Palbociclib displayed potent antiproliferative activity in 14 of 15 liver cancer cell lines (figure 1A). Palbociclib-sensitive (HCC202) and palbociclib-resistant (BT549) breast cancer cell lines were used as controls.8 Similar results were obtained by performing colony formation assays with a wide range of palbociclib concentrations (figure 1B, C; see online supplementary figure S1A), which provided IC50 values ranging from 1 to 300 nM in the sensitive cell lines. The IC50 value for the two resistant cell lines, BT549 and Hep3B, was >3 μM, a 1–3 log-fold difference compared with the sensitive cell lines. These results indicate that palbociclib treatment restricts proliferation in the majority of human liver cancer cell lines.

Figure 1.

Palbociclib inhibits the proliferation of human liver cancer cell lines. (A) Number of cells, relative to dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-treated condition, after 3 days of treatment with 1 μM palbociclib (PD). BT549 and HCC202 (in pink) are two breast cancer cell lines used as retinoblastoma (RB1)-negative and RB1-positive controls, respectively. Hep3B, indicated in blue, was the only hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)-resistant cell line. The mean+SD is shown. (B) Crystal violet staining of colonies from five representative cell lines treated during 2 weeks with the indicated doses of PD. (C) IC50 values calculated by quantifying the extracted crystal violet in (B).

gutjnl-2016-312268supp001.pdf (1.6MB, pdf)

Palbociclib induces a reversible cell cycle arrest in human liver cancer cell lines

Palbociclib is a potent inhibitor of cell growth and suppresses DNA replication by preventing cells from entering S phase.15 Bromodeoxyuridine (incorporation, a measure of cell proliferation, was profoundly attenuated in most of the liver cancer cell lines upon palbociclib treatment for 3 days at 1 μM (see online supplementary figure S2A). Cell cycle analyses performed by flow cytometry using DAPI staining revealed a G0/G1-phase arrest, consistent with suppression of CDK4/6 activity (see online supplementary figure S2B, C). However, palbociclib-treated cells displayed minimal cell death as indicated by negligible sub-G1 accumulation (see online supplementary figure S2D). Together, these data support a proposed cytostatic mechanism of action of palbociclib in liver cancer cell lines.

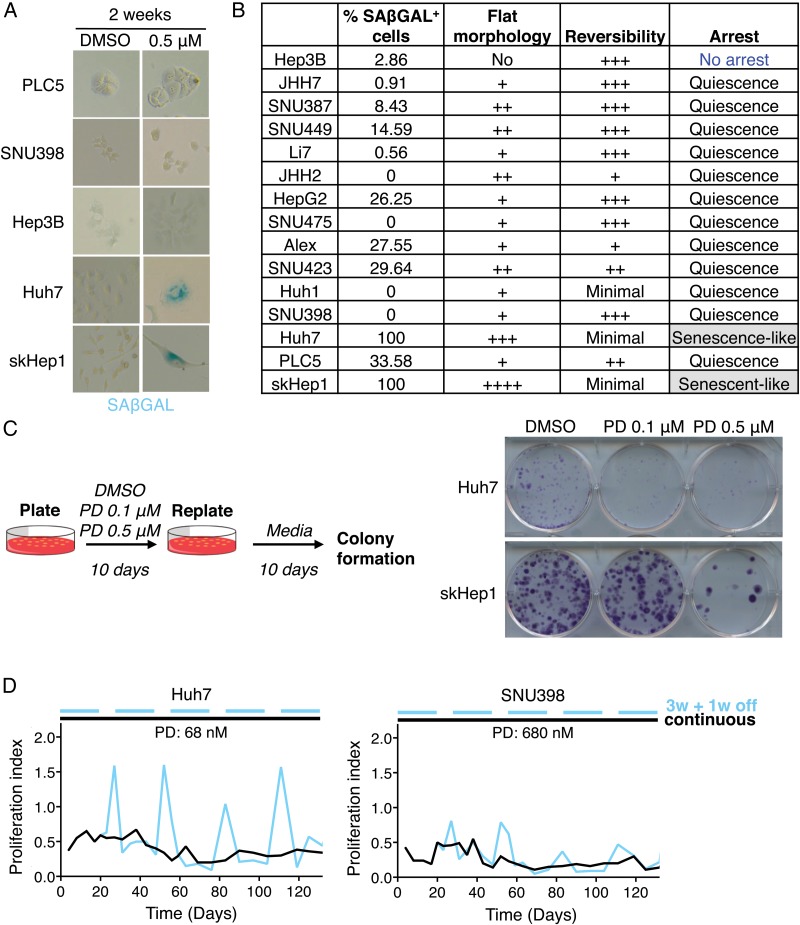

Cell cycle arrest can be reversible (quiescence) or irreversible (senescence).16 Cellular senescence is defined by several non-exclusive features including flat cell morphology, positive staining for senescence-associated β-galactosidase at pH 6.0 (SAβGAL), DNA damage and a specific secretory phenotype.17 In order to distinguish between quiescent and senescent states, we stained liver cancer cell lines for SAβGAL after long-term exposure to palbociclib (14 days at 0.5 μM). Only two of the cell lines, Huh7 and skHep1, were consistently positive for staining (figure 2A, B). Furthermore, after palbociclib treatment, these two cell lines displayed flat and enlarged morphology (figure 2A, B), suggesting that they could have undergone senescence.

Figure 2.

Palbociclib (PD) induces a reversible cell cycle arrest in human liver cancer cell lines. (A) Representative pictures (×200 magnification) of senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SAβGAL) staining in five representative cell lines treated with PD. Blue indicates positive staining. (B) Table summarising the assays to evaluate cellular senescence. (C) Reversibility assay. Left, schematic. Right, crystal violet staining after replating cells that were pretreated as indicated. (D) Proliferation of cells, relative to dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-treated cells, treated continuously (black) or discontinuously (blue) with PD, over time. W, week.

To test for reversibility of the cell cycle arrest, which is the key distinguishing factor between senescence and quiescence, cells were treated with palbociclib (0.1 and 0.5 μM) for 10 days to arrest them, and then replated in equal numbers and cultured for 10 additional days in the absence of the inhibitor. Crystal violet staining revealed that most of the cell lines were barely affected by previous palbociclib treatment as cells grew similar to vehicle-treated cells (dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)) (see online supplementary figure S2E). In the case of Huh7 and skHep1 cell lines, there was a drastic reduction in the number of colonies that emerged (figure 2C), indicating that some cells were in fact irreversibly arrested. However, there was still some growth, particularly at lower doses of palbociclib (figure 2C). These results imply that while palbociclib may induce an irreversible cell cycle arrest in some cells, this may be dose dependent.

To explore this hypothesis further, we treated two cell lines, Huh7 and SNU398, either continuously or discontinuously, with palbociclib. Huh7 cells, which showed an irreversible arrest at 0.1 μM, were treated with a lower dose (68 nM) while SNU398 cells, which underwent a reversible cell cycle arrest at 0.5 μM, were subjected to a higher dose (680 nM). The discontinuous treatment resembled the typical regimen in the clinic, with 3 weeks of treatment and 1 week of drug holiday.7 Huh7 cells during the drug holiday resumed proliferation while SNU398 showed a less pronounced recovery of proliferation (figure 2D). These results suggest that the effects of palbociclib are cell line and dose dependent. Taken together, our results show that palbociclib predominantly induces a reversible cell cycle arrest in human liver cancer cell lines and that the current treatment schedule may lead to tumour regrowth during the drug holiday if senescence is not successfully achieved.

RB1 loss and palbociclib resistance in HCC

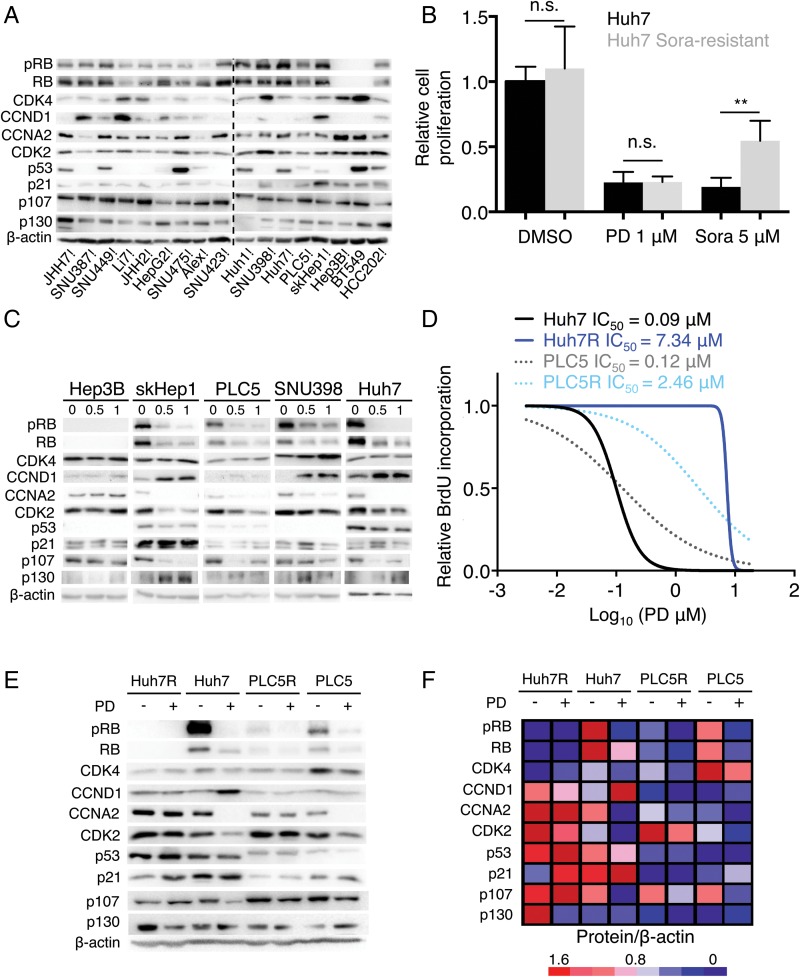

Palbociclib is an orally active, potent and highly selective inhibitor of the CDK4 (IC50, 11 nM) and CDK6 (IC50, 16 nM) kinases,15 which in turn block RB1 activity.18–20 Palbociclib arrests cell cycle progression only if RB1 is functionally intact.6 7 As expected, RB1 was absent in palbociclib-resistant Hep3B and BT549 cells (figure 3A). The protein levels of CDK4 and CCNA2, a well-characterised RB/E2F-target gene and positive indicator of proliferation,21 were higher in palbociclib-resistant cells (figure 3A). However, there was no apparent association between resistance to the drug and a panel of other cell cycle-related proteins, including the RB1-like proteins p107 (RBL1) and p130 (RBL2) (figure 3A). Notably, response to palbociclib was not affected by acquired resistance to sorafenib (figure 3B and see online supplementary figure S3A),22 the standard of care for HCC patients.4

Figure 3.

Retinoblastoma (RB1) loss of function correlates with resistance to palbociclib (PD) in human liver cancer cell lines. (A) Immunoblotting analysis of indicated proteins (basal levels) in the panel of liver cancer cell lines. BT549 and HCC202 are two breast cancer cell lines used as RB1-negative and RB1-positive controls, respectively. The dashed line separates independent gels. (B) Number of cells, relative to dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-treated condition, after 3 days of treatment with 1 μM PD or 5 μM sorafenib (Sora). The mean+SD is shown. (C) Immunoblotting of different proteins after treatment with the indicated doses of PD during 3 days for five representative cell lines. (D) Dose–response curves for different doses of PD. The corresponding IC50 value of each cell line is included. (E) Immunoblotting of designated proteins after treatment with 0.5 μM of PD for 3 days in the parental or resistant (R) cell lines. (F) Heatmap showing protein levels relative to β-actin. Red indicates high while blue indicates low, and it is relative in each row.

CDK4/6 assembles with its allosteric activators, the D-type cyclins, to phosphorylate and inactivate RB1 allowing cell cycle progression.7 As a confirmatory measure of functional activity of CDK4/6, the Ser780 phosphorylation state of RB1 was assessed. Exposure of liver cancer cell lines to palbociclib resulted in a dose-dependent inhibition of RB1 phosphorylation in the sensitive cell lines as well as a substantial decrease in total RB1 levels (figure 3C) that has been previously observed in other tumour types.15 23 In all cells tested, protein levels of CDK4 were unchanged or slightly increased by palbociclib. Cyclin D1 (CCND1) was consistently increased in sensitive cell lines, possibly as a result of the stabilisation of an inactive CCND1-CDK4 complex by palbociclib,24 whereas cyclin A2 (CCNA2) was attenuated by palbociclib in sensitive cell lines. Similarly, cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2), which facilitates S phase entry,25 was decreased in sensitive cell lines. As described previously,26 the levels of RB1 related protein p107 were decreased while the levels of p130 were increased. As expected, palbociclib effectively inhibits CDK4/6 activity to suppress S-phase entry and proliferation of RB1-proficient liver cancer cell lines.

Given these findings, we attempted to generate palbociclib-resistant cell lines by continuously exposing cells to increasing doses of the drug (see online supplementary figure S3B). This approach led to the generation of palbociclib-resistant PLC/PRF/5 (PLC5 hereafter) and Huh7 cells with a 20-fold increase in the IC50 for palbociclib for PLC5-resistant (PLC5R) and 80-fold for Huh7R cells (figure 3D). The fact that Huh7 cells can get irreversibly arrested was not impediment for the emergence of resistant cells. Further analysis revealed that RB1 protein was completely lost (Huh7R) or persisted at a greatly reduced level (PLC5R) in resistant variants (figure 3E). In both cases, there was a moderate decrease in CDK4 protein levels and a slight increase in CDK2 and CCNA2 levels (figure 3E).

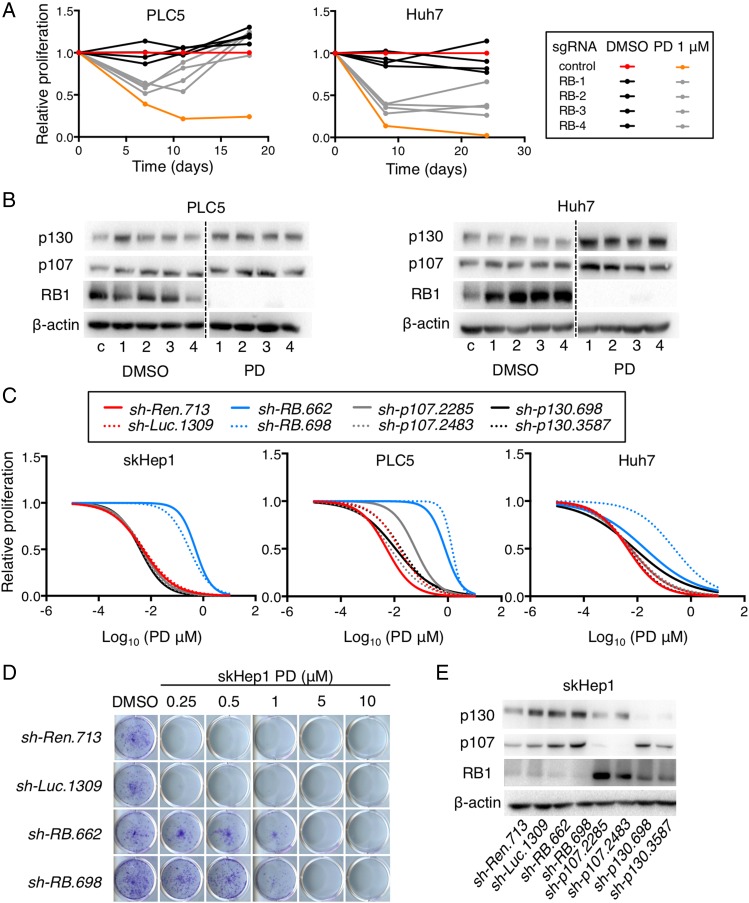

To functionally explore whether partial or complete loss of RB1 was required to confer resistance to palbociclib, we undertook two orthogonal approaches. First, we used Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) technology, which is a genome-editing tool, and transfected four single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) directed against human RB1 into Huh7 and PLC5 cells, which were then treated with DMSO or 1 μM of palbociclib, to study changes in cell proliferation over time (see online supplementary figure S4A). As expected, palbociclib treatment affected the proliferation rate of the control-transfected cells.27 However, cells transfected with RB1 sgRNAs were less affected by palbociclib (figure 4A). The diminished response was more pronounced over time, suggesting the selection of RB1-deficient cells with palbociclib. Indeed, immunoblot analysis indicated that RB1 was lost at the end of the treatment only in cells expressing sgRNAs for RB1 (figure 4B), demonstrating that complete loss of RB1 can confer resistance to palbociclib. Second, we infected Huh7, PLC5 and skHep1 with two validated shRNAs (short hairpin RNAs) for RB1.28 Two control shRNAs as well as shRNAs against RB1-related proteins p107 and p130 were also included.28 Knockdown of RB1 was enough to confer resistance to palbociclib while knockdown of p107 or p130 did not (figure 4C, D; see online supplementary figure S4B, C). Most importantly, after RB1 knockdown, the levels of p107 and p130 remained were not decreased, indicating that knockdown of RB1 alone is enough to confer resistance to palbociclib. Taken together, RB1 loss is a key mechanism of palbociclib resistance in human liver cancer cell lines.

Figure 4.

Loss of retinoblastoma (RB1) confers resistance to palbociclib (PD) in human liver cancer cell lines. (A) Proliferation of cells, relative to control cells treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), at different time points. (B) Immunoblotting analysis of indicated proteins at the end of the experiment in (A). The dashed line separates different portions of the same gel. (C) Dose–response curves for different doses of PD and cells infected with different shRNAs. (D) Crystal violet staining of colonies from a representative cell line infected with control or RB1 shRNAs and treated during 2 weeks with the indicated doses of PD. (E) Immunoblotting analysis of indicated proteins (basal levels) of cells in (C). c, control. 1–4 represent the different single-guide RNAs for RB1.

RB1 loss of function signature in human HCC patient samples

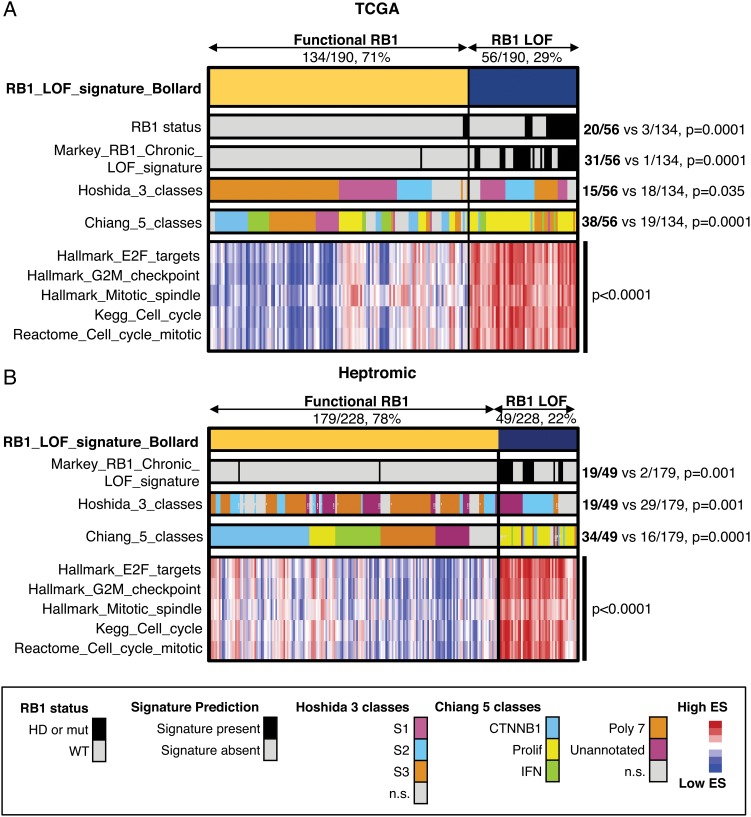

To estimate the percentage of HCC patients that could respond to palbociclib based on RB1 activity, we first compared the expression profiles of RB1 wild-type (WT) and altered (mutation, homozygous deletion) HCC patient samples from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). Gene set enrichment analysis revealed that the gene sets ‘E2F_targets’, ‘G2M_checkpoint’ and ‘mitotic_spindle’ from the Hallmarks collection29 were significantly enriched in RB1-deficient patient samples (see online supplementary figure S5A). Similar results were obtained by Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) analysis (see online supplementary figure S5B).30 We then established a gene signature of ‘RB1 loss of function’ (‘RB1_LOF’) by comparing the same RB1 WT and altered HCC patient samples (see online supplementary table S1). The signature was present in 29% of the samples and included both RB1-altered and RB1-WT samples (figure 5A). ‘RB1_LOF’ signature correlated with a previously defined signature of RB1 loss in mice,31 with the S1 and proliferative HCC subclasses,13 32 and with several cell cycle-related gene sets, including ‘E2F_targets’, ‘G2M_checkpoint’, ‘mitotic spindle’, ‘KEGG_cell_cycle’ and ‘Reactome_cell_cycle_mitotic’ (figure 5A). By applying this signature to an independent data set,33 we found that 22% of the human HCC patient samples had enrichment of ‘RB1_LOF’ (figure 5B), suggesting that overall around 70% of all HCC patients could potentially respond to palbociclib.

Figure 5.

Retinoblastoma (RB1) loss of function (RB1_LOF) signature in human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients. (A) Heatmap showing the distribution of different gene sets in 190 human HCC patients from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). The proportions of patients for ‘RB1_LOF’ presence or absence are also included. The values for Hoshida class 2 and Chiang proliferation are included. (B) Same as in (A) but for a different patient cohort including 278 HCC patients. HD, homozygous deletion; IFN, interferon; mut, mutation; WT, wild-type; ES, enrichment score; n.s., not significant.

Palbociclib is effective in organotypic ex vivo human HCC samples

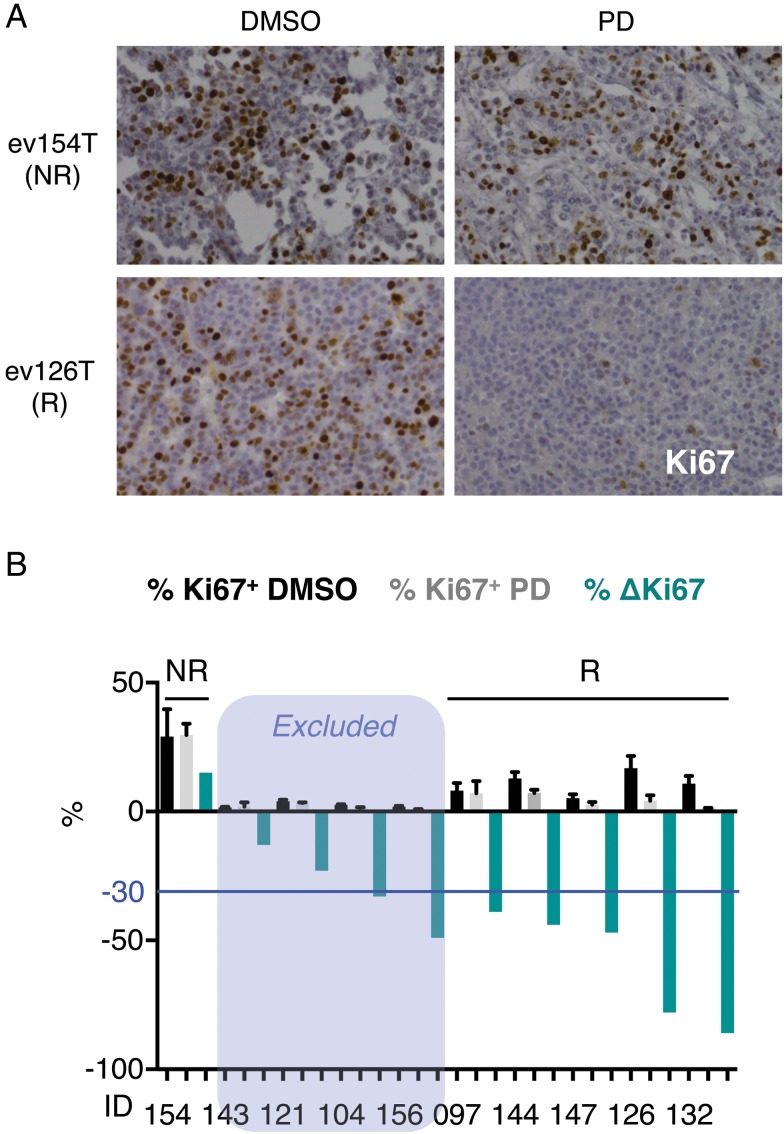

We next tested the effects of palbociclib in a more physiological setting, in organotypic ex vivo culture of HCC tumour tissues from 10 patients, where multi-cell-type tissue microenvironment is preserved.34 This ex vivo assay allows assessment of novel therapies in tumour tissues explanted from patients without the difficulty and expense of implanting tumour cells into animals. Ex vivo culture for 2 days in vehicle (DMSO) or palbociclib (10 μM) did not overtly disrupt the morphological features, as indicated by H&E staining (see online supplementary figure S6A). High concentrations of the drug were used to allow for tissue perfusion.34 After excluding those samples with low percentage of Ki67-positive cells in the vehicle (DMSO) condition (Ki67+<5%; n=4), five out of six remaining samples responded to palbociclib treatment (figure 6A, B). A significant increase in the percentage of cleaved-caspase 3-positive cells was observed in some samples, although overall changes were limited (see online supplementary figure S6B). Unexpectedly, RB1 was expressed in the non-responder ex vivo sample (see online supplementary figure S6C), suggesting that RB1 loss of function, rather than RB1 lack of expression, can dictate resistance to palbociclib.

Figure 6.

Palbociclib (PD) is effective in organotypic ex vivo human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) samples. (A) Immunostaining for Ki67 (×200 magnification), a marker of cell proliferation, in representative responder (R) and non-responder (NR) ex vivo human HCC samples treated with PD for 2 days. (B) Percentage of Ki67-positive cells in ex vivo human HCC samples treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (black) or PD (grey) for 2 days. The mean+SD is shown. The percentage of change in Ki67 staining is shown in green. The blue line indicates the threshold (–30%) used to assign responsiveness to PD.

Palbociclib, alone or in combination with sorafenib, has potent antitumour effects in vivo

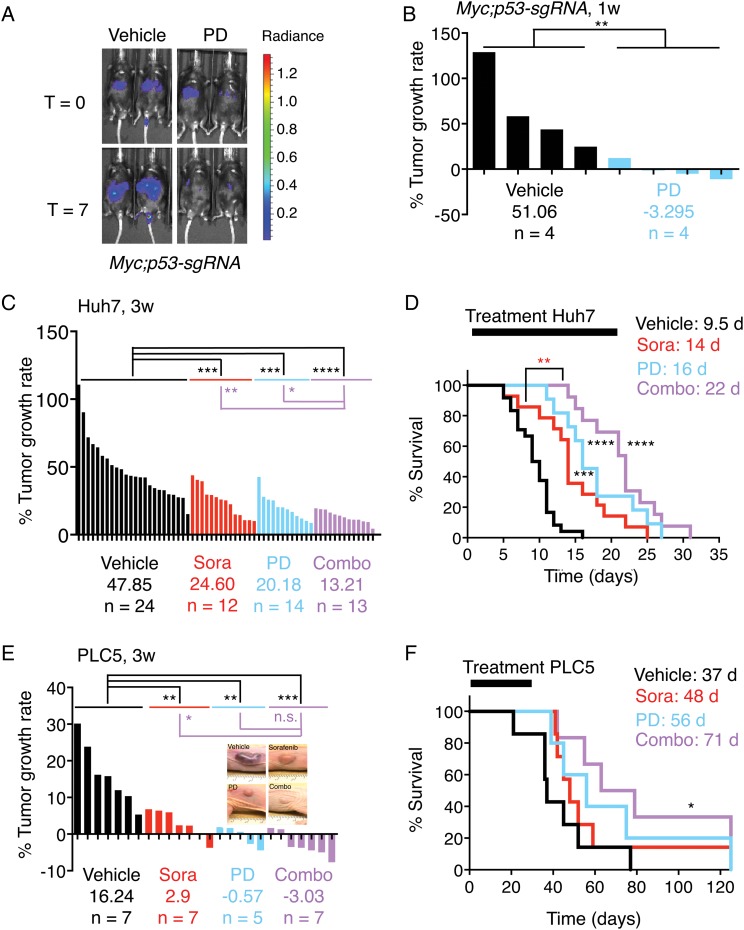

Although palbociclib is effective against liver cancer cells in vitro and ex vivo, additional analyses were performed to discern the in vivo benefit of palbociclib treatment in HCC. We first investigated the potential of palbociclib for liver cancer treatment in a genetically engineered mosaic mouse model of liver cancer (Myc;p53-sgRNA).35 To induce liver tumours, we performed hydrodynamic tail vein injections of transposons expressing Myc36 and luciferase,37 which are integrated into the DNA of hepatocytes following transient expression of transposase from a recombinant transposon vector (see online supplementary figure S7A). A validated sgRNA targeting tumour suppressor p53 was also included to accelerate tumorigenesis (see online supplementary figure S7A).38 Three weeks after the injections, we performed bioluminescence imaging, randomised the mice according to their signal and started daily treatment with either vehicle (n=4, sodium lactate buffer) or palbociclib (n=4, 100 mg/kg). After 1 week of treatment, the luminescence signal in vehicle-treated mice increased dramatically, whereas in palbociclib-treated mice there was a significant decrease (figure 7A, B), indicating that palbociclib treatment can be effective in liver tumours in vivo.

Figure 7.

Palbociclib (PD), alone or in combination with sorafenib (Sora), has potent antitumour effects in vivo. (A) Bioluminescence imaging of representative mice (Myc;p53-sgRNA) before and after 1 week of treatment. The colour scale is shown on the right. (B) The percentage of tumour growth rate (per day) per each individual mouse measured by bioluminescence imaging. The average tumour growth rate per group is shown as well as the number of mice. (C) As in (B) but for Huh7 xenografts. (D) Survival curves of the mice in (C). The duration of treatment and median survival per group are indicated at the top. (E) As in (B) but for PLC5 xenografts. (F) Survival curves of the mice in (E). The treatment window and median survival per group are indicated as in (D). combo, combination of sorafenib and palbociclib; d, days; V, vehicle; W, weeks.

To validate this further, we also studied human HCC xenografts. Sorafenib, the standard of care for HCC treatment,3 was also included for comparison. Mice harbouring Huh7 and PLC5 xenografts were treated with vehicle (sodium lactate buffer or cremophor/ethanol), sorafenib (30 mg/kg), palbociclib (100 mg/kg) or a combination of both once the tumours reached a volume of 100–200 mm3. The single or combined treatments were well tolerated, with no obvious clinical signs of distress and either minimal weight loss or some weight gain (see online supplementary figure S7B). Tumour development was manifested for mice harbouring Huh7 xenografts (figure 7C), and all vehicle-treated mice (n=24) died within 16 days, with a median survival of 9.5 days (figure 7D). Both sorafenib (n=12) and palbociclib (n=14) significantly delayed tumour growth (figure 7C) and increased survival (figure 7D) to 14 and 16 days, respectively. The combination of sorafenib and palbociclib (n=13) was even more effective, with a significant and pronounced reduction in tumour growth (figure 7C) and by significantly increasing the median survival to 22 days (figure 7D). The combination was also significantly more efficacious than sorafenib (figure 7C, D), the standard of care for HCC patients. Similar results were obtained in PLC5 xenografts, which were treated for up to 30 days (figure 7E, F). Moreover, tumour regressions were observed for this cell line, particularly following combination treatment (figure 7E). The median survival with sorafenib (n=7) and palbociclib (n=5) was extended from 37 days (vehicle, n=7) to 48 and 56 days, respectively (figure 7F). The longest median survival was achieved with the combination treatment (n=7; 71 days) (figure 7F). Three mice treated with the combination therapy and one mouse treated with palbociclib were kept for 4 months with no signs of disease pointing to complete cures. In the remaining mice, after stopping treatment at day 30, tumours grew back (see online supplementary figure S7C), denoting that the arrest or regression in tumour growth is temporary, at least for this cell line. Taken together, our results indicate that palbociclib is as beneficial as sorafenib, whereas the combination of palbociclib and sorafenib is significantly more effective than sorafenib alone.

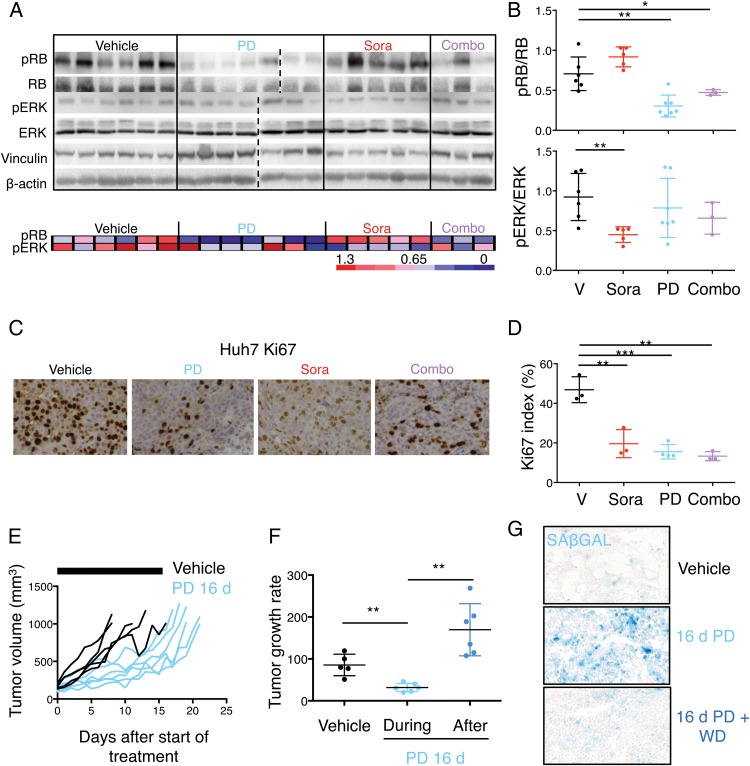

In parallel with the in vivo efficacy tests (figure 7), additional Huh7 tumours, treated for 5 days, were harvested for pharmacodynamic and mechanistic analyses to test whether antitumor activity correlated with modulation of the targets. Phosphorylation of Ser780 in RB1 was significantly decreased in tumours treated with palbociclib, alone or in combination with sorafenib, and phosphorylation of ERK was significantly decreased in sorafenib-treated tumours (figure 8A, B). However, only a slight decrease in phosphorylation of ERK was observed in the combination-treated tumours, possibly as a result of the rebound in ERK phosphorylation (tumours were collected 4 hours after the last dose).39 Palbociclib has been shown to provide a significant benefit when combined with inhibitors that target the levels of D-type cyclins.7 8 To test whether this prediction holds true for palbociclib and sorafenib, we tested the effects of sorafenib on CCND1 levels in vitro in Huh7 and PLC5 cells. Treatment with sorafenib led to a decrease in the phosphorylation of ERK and CCND1 protein levels (see online supplementary figure S8A), in part explaining the benefits of combining palbociclib and sorafenib.

Figure 8.

Effects of mono or combinatorial therapies in vivo. (A) Top, immunoblotting of designated proteins in tumours isolated from Huh7 xenografted mice after 5 days of treatment. Bottom, heatmap showing phospho-RB (pRB) and phospho-ERK (pERK) levels relative to RB and ERK, respectively, from (A). Red indicates high while blue indicates low, and it is relative in each row. (B) Dot plots with quantification of the relative pRB and pERK levels. The mean±SD is shown. (C) Immunostaining for Ki67 (×200 magnification), a marker of cell proliferation, in representative tumours treated with the indicated treatments for 5 days. (D) Quantification of Ki67 index in the different treatment groups. The mean±SD is shown. (E) Spider plots depicting tumour growth in each group of treatment over time. The black bars represent the treatment period (16 days). (F) Quantification of tumour growth rate in vehicle-treated and palbociclib-treated mice (during the 16 days of treatment and after treatment). The mean±SD is shown. (G) Representative images of senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SAβGAL) staining in vehicle-treated and palbociclib-treated tumours at day 16. A representative image of a tumour treated for 16 days and left untreated for additional 3 days it shown ×100 magnification. Combo, combination of sorafenib and palbociclib; d, days; PD, palbociclib; Sora, sorafenib; V, vehicle; WD, withdrawal.

Mechanistically, Huh7 tumours in control-treated animals were proliferative, determined by Ki67 staining. Quantification revealed a significant reduction (68%) in Huh7 proliferation upon palbociclib treatment, 63% with sorafenib and 73% with combination therapy (figure 8C, D). However, no changes in apoptosis were observed (see online supplementary figure S8B, C). To test whether palbociclib could induce cellular senescence in vivo, Huh7 cells (which show a senescent phenotype in vitro) were subcutaneously injected into nude mice. Once the tumours reached 100–200 mm3, we randomised the mice into two groups and treated them with vehicle or palbociclib (100 mg/kg) for 16 days. Tumour growth rate in palbociclib-treated mice was significantly lower than in vehicle-treated mice (figure 8E, F). However, once the treatment with palbociclib was discontinued, the tumour growth rate significantly increased, suggesting tumour cells were reversibly arrested by palbocilcib treatment (figure 8E, F). Analysis of tumours collected after treatment with vehicle or palbociclib (for 16 days) showed that palbociclib-treated tumours were positive for the senescence marker SAβGAL (figure 8G). However, a fraction of the tumour cells was negative for the staining. Those SAβGAL-negative cells could either be proliferative, contributing to the slow but positive growth of tumours upon palbociclib treatment, or reversibly arrested, being able to resume proliferation upon palbociclib withdrawal. In fact, SAβGAL staining of the tumours subjected to palbociclib withdrawal showed that the decrease in percentage of SAβGAL-positive cells correlated with the number of days in withdrawal (figure 8G; see online supplementary figure S8D), further supporting the hypothesis that SAβGAL-negative cells may be contributing to tumour growth. Taken together, our results indicate that palbociclib treatment of human liver tumours in vivo leads to cellular senescence in a high percentage of tumour cells. However, the remaining malignant cells are reversibly arrested and can still contribute to tumour growth. In conclusion, our results indicate that palbocilcib significantly reduces tumour growth, alone or in combination with sorafenib, and could represent a promising strategy for HCC.

Discussion

HCC is one of the most lethal malignancies, in part due to the lack of curative treatments. The multikinase inhibitor sorafenib is the only effective targeted therapy for advanced HCC patients, although most of them eventually undergo disease progression.4 Here, we provide the most comprehensive preclinical evaluation of a CDK4/6 inhibitor, palbociclib, in HCC to date, and build the case for its clinical development as first-line therapy, potentially in combination with sorafenib. Palbociclib efficiently reduced proliferation of HCC cells in vitro and of primary human tumour tissues ex vivo. Moreover, palbociclib decreased tumour burden in a genetically engineered mouse model of liver cancer and in human HCC xenografts in vivo, and cooperated with sorafenib to enhance therapeutic impact, being well tolerated.

Mechanistically, RB1 loss constituted the main mechanism of intrinsic and acquired resistance in human liver cancer cell lines, suggesting the need to stratify patients based on RB1 status. While acute loss of RB1 has been reported to have little effect on the short-term response to palbociclib in liver cancer cells, due to compensatory mechanisms by RB1 family members,26 we have now demonstrated that acquired resistance to palbociclib through chronic exposure to the drug is mediated by RB1 loss. Moreover, partial or complete loss of RB1 leads to palbociclib resistance, further confirming the key role of RB1 in response to palbociclib in human HCC. By creating a signature of ‘RB1-LOF’, we estimate that 70% of human HCC patients could respond to palbociclib. Nevertheless, additional preclinical and clinical studies will be needed to refine response prediction in HCC patients and optimise patient selection.

Recent studies in other tumour types have shown that palbociclib can induce cellular senescence,40–43 which is an irreversible cell cycle arrest.16 In HCC cells, we observed a reversible cell cycle arrest in most of the cell lines. Considering that the current clinical regimen for palbociclib includes a week of drug holiday, achieving an irreversible arrest in vivo or changing the dosing schedule (lower dose, continuous treatment) will be crucial to avoid tumour regrowth. This may also be avoided with the use of abemaciclib, another CDK4/6 inhibitor that presents lower associated toxicity that allows continuous treatment.7 Furthermore, understanding what determines the choice between quiescence and senescence after palbociclib treatment in HCC cells will be critical. As an alternative, the combination of palbociclib with other compounds (targeted therapies, chemotherapies, immunotherapies) may trigger senescence or apoptosis. In our in vivo models, combination of palbociclib with sorafenib, the standard of care for HCC patients,4 had additive effects and led, in some cases, to tumour regression and complete responses. Strategies that target D-type cyclins, such as inhibition of ER or ERK signalling, have been shown to synergise with palbociclib,7 8 and the ability of sorafenib to inhibit ERK signalling and CCND1 protein levels can explain the beneficial effects of combining sorafenib and palbociclib. The identification of synergistic partners for palbociclib in HCC will allow stronger effects by minimising undesirable toxicity.

Taken together, our findings support further clinical evaluation of palbociclib, as a single agent or in combination with sorafenib, in patients with HCC. Of note, palbociclib is well tolerated and lacks associated liver toxicity,8 9 further reinforcing its potential for liver cancer treatment. ‘RB1_LOF’ signature could be used as a predictor of resistance to palbociclib. The assessment of additional response predictors in these clinical trials may help to refine the patient subgroup most likely to benefit from treatment with palbociclib. Finally, the use of synergistic drug combinations with palbociclib in HCC will lead to stronger and more durable responses with reduced toxicity.

Materials and methods

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean±SD. Statistical significance was determined using Mann-Whitney U test (when n <10 or non-normal distribution) or Student’s t-test (n >10 and normal distribution). Correlation was calculated using the Pearson test. Group size was determined based on the results of preliminary experiments and no statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. Group allocation was performed randomly while outcome assessment was not performed in a blinded manner. The differences in survival were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier test. Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software) was used to create the graphs and for the statistical analysis. Significance values were set at *p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001.

The rest of materials and methods can be found in online supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully thank Charles J. Sherr, Scott L. Friedman, Augusto Villanueva and Andrew Koff for careful editing of the manuscript and useful comments on the paper. They thank members of the Koff Laboratory and the Division of Liver Diseases for stimulating discussions. They also thank the Bernstein, Parsons, Poulikakos, Mulholland, Papapetrou, and Koff Laboratories for reagents. In addition, the authors thank ISMMS Animal Facilities, ISMMS Imaging Facility, ISMMS Flow Cytometry Core. JB thanks the Claude Rose Award from the CECED. J

Footnotes

Contributors: JB designed the experiments, performed the majority of the experiments and analysed the data. VM, MRdG, AV, CBB, MPR, VT, DS, PM-S, CBN and SN performed critical experiments. JML and YH provided important intellectual input. AL designed the experiments, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript, which was edited by all authors.

Funding: JB and AL are funded by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) Pinnacle Research Award. VM, MRG, AV, CBB, MPR, DS, PMS, CBN, SN, and YH are funded by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. VT is supported by a grant from the Asociación Española Contral el Cáncer (AECC). JML is supported by grants from The European Commission Framework Programme 7 (HEP-CAR grant, number 667273-2 and HEPTROMIC, proposal no: 259744), the Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation, the Spanish National Health Institute (SAF-2013-41027) and the AECC.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: We are happy to share our data and resources upon request.

References

- 1. Llovet JM, Villanueva A, Lachenmayer A, et al. . Advances in targeted therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma in the genomic era. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2015;12:436 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. . Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:87–108. 10.3322/caac.21262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Llovet JM, Hernandez-Gea V. Hepatocellular carcinoma: reasons for phase III failure and novel perspectives on trial design. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20:2072–9. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. . Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2008;359:378–90. 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Malumbres M, Barbacid M. Cell cycle kinases in cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2007;17:60–5. 10.1016/j.gde.2006.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Asghar U, Witkiewicz AK, Turner NC, et al. . The history and future of targeting cyclin-dependent kinases in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2015;14:130–46. 10.1038/nrd4504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sherr CJ, Beach D, Shapiro GI. Targeting CDK4 and CDK6: from discovery to therapy. Cancer Discov 2016;6:353–67. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Finn RS, Crown JP, Lang I, et al. . The cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor palbociclib in combination with letrozole versus letrozole alone as first-line treatment of oestrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative, advanced breast cancer (PALOMA-1/TRIO-18): a randomised phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:25–35. 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71159-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Turner NC, Ro J, Andre F, et al. . Palbociclib in hormone-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;373:209–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schwartz GK, LoRusso PM, Dickson MA, et al. . Phase I study of PD 0332991, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, administered in 3-week cycles (Schedule 2/1). Br J Cancer 2011;104:1862–8. 10.1038/bjc.2011.177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Flaherty KT, Lorusso PM, Demichele A, et al. . Phase I, dose-escalation trial of the oral cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor PD 0332991, administered using a 21-day schedule in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:568–76. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schulze K, Imbeaud S, Letouzé E, et al. . Exome sequencing of hepatocellular carcinomas identifies new mutational signatures and potential therapeutic targets. Nat Genet 2015;47:505–11. 10.1038/ng.3252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hoshida Y, Nijman SM, Kobayashi M, et al. . Integrative transcriptome analysis reveals common molecular subclasses of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 2009;69:7385–92. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen B, Sirota M, Fan-Minogue H, et al. . Relating hepatocellular carcinoma tumor samples and cell lines using gene expression data in translational research. BMC Med Genomics 2015;8(Suppl 2):S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fry DW, Harvey PJ, Keller PR, et al. . Specific inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 by PD 0332991 and associated antitumor activity in human tumor xenografts. Mol Cancer Ther 2004;3:1427–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Campisi J, d'Adda di Fagagna F. Cellular senescence: when bad things happen to good cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2007;8:729–40. 10.1038/nrm2233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sharpless NE, Sherr CJ. Forging a signature of in vivo senescence. Nat Rev Cancer 2015;15:397–408. 10.1038/nrc3960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kato J, Matsushime H, Hiebert SW, et al. . Direct binding of cyclin D to the retinoblastoma gene product (pRb) and pRb phosphorylation by the cyclin D-dependent kinase CDK4. Genes Dev 1993;7:331–42. 10.1101/gad.7.3.331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Matsushime H, Ewen ME, Strom DK, et al. . Identification and properties of an atypical catalytic subunit (p34PSK-J3/cdk4) for mammalian D type G1 cyclins. Cell 1992;71:323–34. 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90360-O [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ewen ME, Sluss HK, Sherr CJ, et al. . Functional interactions of the retinoblastoma protein with mammalian D-type cyclins. Cell 1993;73:487–97. 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90136-E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Henglein B, Chenivesse X, Wang J, et al. . Structure and cell cycle-regulated transcription of the human cyclin A gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994;91:5490–4. 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tovar V, Cornella H, Moeini A, et al. . Tumour initiating cells and IGF/FGF signalling contribute to sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut Published Online First: 11 Dec 2015. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309501 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Finn RS, Dering J, Conklin D, et al. . PD 0332991, a selective cyclin D kinase 4/6 inhibitor, preferentially inhibits proliferation of luminal estrogen receptor-positive human breast cancer cell lines in vitro. Breast Cancer Res 2009;11:R77 10.1186/bcr2419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Comstock CE, Augello MA, Goodwin JF, et al. . Targeting cell cycle and hormone receptor pathways in cancer. Oncogene 2013;32:5481–91. 10.1038/onc.2013.83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tsai LH, Harlow E, Meyerson M. Isolation of the human cdk2 gene that encodes the cyclin A- and adenovirus E1A-associated p33 kinase. Nature 1991;353:174–7. 10.1038/353174a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rivadeneira DB, Mayhew CN, Thangavel C, et al. . Proliferative suppression by CDK4/6 inhibition: complex function of the retinoblastoma pathway in liver tissue and hepatoma cells. Gastroenterology 2010;138:1920–30. 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, et al. . Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 2013;339:819–23. 10.1126/science.1231143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chicas A, Wang X, Zhang C, et al. . Dissecting the unique role of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor during cellular senescence. Cancer Cell 2010;17:376–87. 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.01.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liberzon A, Birger C, Thorvaldsdottir H, et al. . The Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst 2015;1:417–25. 10.1016/j.cels.2015.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc 2009;4:44–57. 10.1038/nprot.2008.211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Markey MP, Bergseid J, Bosco EE, et al. . Loss of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor: differential action on transcriptional programs related to cell cycle control and immune function. Oncogene 2007;26:6307–18. 10.1038/sj.onc.1210450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chiang DY, Villanueva A, Hoshida Y, et al. . Focal gains of VEGFA and molecular classification of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 2008;68:6779–88. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Villanueva A, Portela A, Sayols S, et al. . DNA methylation-based prognosis and epidrivers in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2015;61:1945–56. 10.1002/hep.27732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vaira V, Fedele G, Pyne S, et al. . Preclinical model of organotypic culture for pharmacodynamic profiling of human tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010;107:8352–6. 10.1073/pnas.0907676107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chen X, Calvisi DF. Hydrodynamic transfection for generation of novel mouse models for liver cancer research. Am J Pathol 2014;184:912–23. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tschaharganeh DF, Xue W, Calvisi DF, et al. . p53-dependent Nestin regulation links tumor suppression to cellular plasticity in liver cancer. Cell 2014;158:579–92. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wiesner SM, Decker SA, Larson JD, et al. . De novo induction of genetically engineered brain tumors in mice using plasmid DNA. Cancer Res 2009;69:431–9. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Xue W, Chen S, Yin H, et al. . CRISPR-mediated direct mutation of cancer genes in the mouse liver. Nature 2014;514:380–4. 10.1038/nature13589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Caunt CJ, Sale MJ, Smith PD, et al. . MEK1 and MEK2 inhibitors and cancer therapy: the long and winding road. Nat Rev Cancer 2015;15: 577–92. 10.1038/nrc4000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kovatcheva M, Liu DD, Dickson MA, et al. . MDM2 turnover and expression of ATRX determine the choice between quiescence and senescence in response to CDK4 inhibition. Oncotarget 2015;6:8226–43. 10.18632/oncotarget.3364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Puyol M, Martin A, Dubus P, et al. . A synthetic lethal interaction between K-Ras oncogenes and Cdk4 unveils a therapeutic strategy for non-small cell lung carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2010;18:63–73. 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wiedemeyer WR, Dunn IF, Quayle SN, et al. . Pattern of retinoblastoma pathway inactivation dictates response to CDK4/6 inhibition in GBM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010;107:11501–6. 10.1073/pnas.1001613107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zou X, Ray D, Aziyu A, et al. . Cdk4 disruption renders primary mouse cells resistant to oncogenic transformation, leading to Arf/p53-independent senescence. Genes Dev 2002;16:2923–34. 10.1101/gad.1033002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

gutjnl-2016-312268supp001.pdf (1.6MB, pdf)