Abstract

Objective:

The aim of the study was to investigate whether the deformation of left atrium (LA) measured by speckle-tracking analysis (STE) is associated with the presence of LA appendage thrombus (LAAT) during non-valvular atrial fibrillation (AF).

Methods:

Eighty-seven patients (mean age 67 years, 59% men) were included to retrospective cross-sectional study. On top of standard echocardiography we assessed: LA longitudinal systolic strain (LS), systolic (LSSR) and early diastolic strain rate (LESR) in four-chamber and two-chamber apical views. All patients underwent transesophageal echocardiography disclosing LAAT in 36 (41%) patients.

Results:

Subgroups with and without thrombi did not differ with regard to clinical characteristics. Univariate factors associated with LAAT were as follows: CH2ADS2-VASc Score, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), LV mass, and STE measurements. In a multivariate model only LVEF (p=0.002), LS (p=0.02), LESR (p=0.008), and LSSR (p=0.045) were independently associated with LAAT presence. Moreover, LVEF and LA STE measurements provided incremental value over the CH2ADS2-VASc Score.

Conclusion:

Speckle-tracking TTE may be used to describe LA reservoir and conduit function during AF, allowing the identification of patients with higher risk of LAAT and providing incremental value over the CH2ADS2-VASc Score.

Keywords: heart failure, left atrial deformation, left atrial strain, left atrial strain rate, left ventricular systolic dysfunction, thromboembolism

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia and affects 1%–2% of the general population (1, 2). Its presence is associated with the worsening of quality of life, the development of heart failure symptoms, and the risk of thromboembolic events, including stroke or transient ischemic attack (3–5).

AF, especially longer in duration and managed by rate control strategy, leads to fibrosis and remodeling of left atrial (LA) wall. Structural atrial remodeling in AF is manifested by lower myocardial velocities, lower compliance, worsening in strain and strain rate, lower emptying fraction, and cavity enlargement (6–8). The contractile dysfunction of atria during arrhythmia leads to decreased blood flow velocity and favors the creation of thrombi (4, 9). Most commonly, thrombi develop in LA appendage (LAA; 2, 4). The prevalence of thrombi in LAA (LAAT) in anticoagulated patients with AF before cardioversion amounts to 7%–8% and still poses a problem (10, 11). The gold-standard technique for detecting flow stasis, spontaneous echo contrast and LAAT is transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), a semi-invasive method (2, 9, 12).

There are several established methods of LA echocardiographic quantification e.g., anteroposterior and superoinferior diameter, area in four-chamber view and volumes by area–length formulas in single or biplane views (13, 14). The utility of linear measurements is limited, because LA enlarges in an asymmetrical way (13). However, echocardiography enables not only morphological but also functional assessment of LA. Normal LA function consists of three phases: a reservoir component relevant to a blood inflow from pulmonary veins beginning with ventricular systole, a passive conduit component during early ventricular diastole, and a pump component during the late diastole of ventricle (12, 15, 16). The last component is absent in AF (6, 15).

Speckle-tracking echocardiography (STE) is a non-Doppler, angle-independent technique allowing the measurement of global and regional atrial strain (6, 17). Several studies have already proved the usefulness of LA STE in sinus rhythm (12, 18) and in AF (19, 20). LA strain has been shown to have additive value for the risk stratification of embolism and post-stroke mortality (20).

On the basis of these observations, we hypothesized that the worsening of LA function demonstrated by TTE combined with STE may be associated with the presence of LAAT in patients with AF. Potentially, LA regional strain maps could be useful for identifying patients with worse function of LAA and higher probability of LAAT. Moreover, we studied the potential incremental significance of LA strain and strain rate over traditional risk stratification scheme.

Methods

Population characteristics

We conducted retrospective, cross-sectional study. We analyzed the database of reports of a tertiary cardiology center echocardiographic laboratory and identified 104 patients (mean age 67±11 years, 57% men) referred for clinically indicated TEE with non-valvular AF who underwent TTE and whose stored TTE images were suitable for STE-based offline analysis. We excluded patients with significant valvular heart disease (prosthetic valve, significant valve insufficiency and moderate stenosis).

Indications for TEE included: scheduled cardioversion (63 patients, 60.6%), scheduled ablation (27 patients, 26%), scheduled implantation of implantable cardioverter–defibrillator (6 patients, 5.8%), pathologies of the thoracic aorta (8 patients, 7.7%).

Data regarding clinical characteristics and treatment were collected on the basis of interviews and hospital documentation using standardized questionnaire. We calculated the CH2ADS2-VASc Score for each patient. The presence of AF was confirmed by means of 12-lead electrocardiogram in each patient. We classified AF as paroxysmal, persisting and permanent.

The anticoagulation was considered therapeutic if anticoa-gulants were used for at least 3 weeks before TEE in proper dosage. In the case of vitamin K antagonists anticoagulation was considered therapeutic if there were at least three recent consecutive measurements of International Normalized Ratio showing values ≥2.

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Local Institutional Review Board and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. This project was approved by the Local Bioethics Committee. All patients gave their written informed consent before the study.

Transthoracic echocardiography

Echocardiographic examinations were performed using Vivid 7 (20 exams, 19.2%) or Vivid E9 (84 exams, 80.8%) echocardiograph (GE Healthcare, Horten, Norway) equipped with M4S (1.5–4.0 MHz) and M5S-D (1.5–4.5 MHz) probe, respectively. All images were acquired during AF. Five cardiac cycles were stored in cine-loop format for further offline analysis. Echocardiographic measurements were done for consecutive beats and thereafter averaged. All linear dimensions and area measurements were taken according to current recommendations (21). Left ventricular (LV) mass was measured using the cube formula (21). The assessment of LV ejection fraction (LVEF) was done using a modified Simpson’s method. LA area was measured by indicating its inner contours in four-chamber (4CH) and two-chamber (2CH) apical views during left ventricular end-systole. LAA and the inlet of the pulmonary veins were excluded. The LA volumes and emptying fraction were obtained using the biplane summation of disks method in the 4CH and 2CH views. Maximal LA volume was measured at the end-systolic phase and minimal at the end-diastolic phase–just before mitral valve opening and closure, respectively.

Transesophageal echocardiography

Transesophageal exams were performed using Vivid 7 (11 exams, 10.6%), Vivid E9 (80 exams, 76.9%; GE Healthcare, Horten, Norway) and Philips iE33 (13 exams, 12.5%; Philips Medical Systems, Bothell, WA) ultrasound machine. We performed detailed assessment of LAA. Second harmonic imaging was applied. Thrombus was defined as echodensity with distinct borders, separate from an endocardium and seen in multiple views. We took into account also LAA emptying velocity with pulse Doppler. The presence of LAAT was verified by two independent echocardiographers. For better visualization in 11 (10.6%) cases a second-generation contrast agent (SonoVue, Bracco International B.V., Amsterdam, the Netherlands) was used to exclude or confirm presence thrombi.

Speckle-tracking echocardiography

On top of standard echocardiographic evaluation of LA function, two-dimensional STE analysis was performed offline using EchoPAC software version 112, revision 1.3 (GE Healthcare, Horten, Norway). We used 4CH and 2CH apical views acquired with frame rate of at least 60 frames per second during breath hold. The LA endocardium was manually contoured and thereafter the region of interest was reduced to the wall thickness. We performed the visual revision of speckle-tracking and in some cases manual adjustments were necessary because of insufficient tracking quality. The software automatically divided LA wall longitudinally into six segments. We measured average peak positive left atrial longitudinal systolic atrial strain (LS, LA lengthening; Fig. 1a), longitudinal systolic strain rate (LSSR, LA reservoir function), and longitudinal early diastolic strain rate (LESR, LA conduit function; Fig. 1b). To resolve the problem of beat-to-beat variation in STE measurements we employed the index-beat method (Fig. 2). This technique has been proved valuable in the assessment of LV strain during AF (22). Particular results were estimated using the ratio of preceding to pre-preceding R-R’ interval. We selected the beat with the smallest difference between prevenient R-R’ intervals.

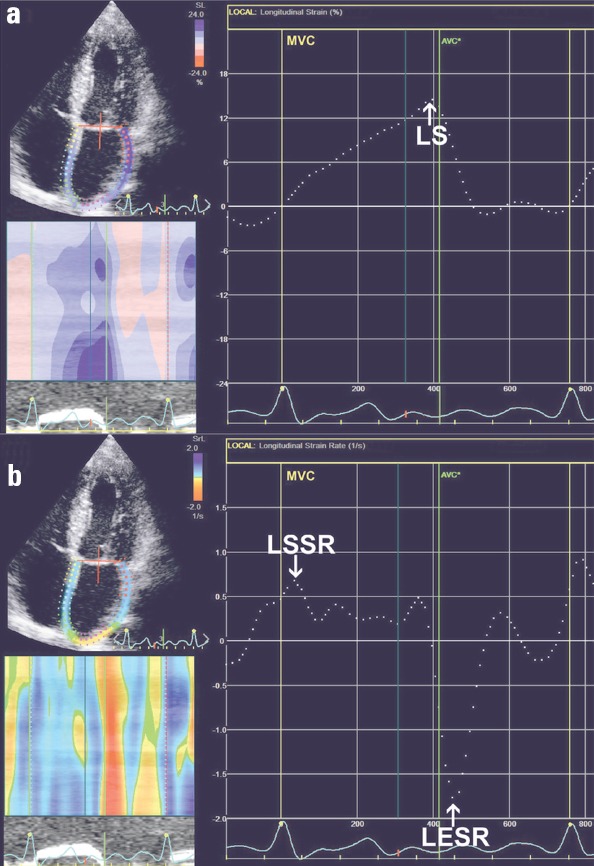

Figure 1.

Two-dimensional STE analysis of LA in the apical four-chamber view in patient with AF. (a) Dashed line reflects mean LA longitudinal strain and allows the measurement of mean peak positive LS. (b) Dashed curve depicts mean LA longitudinal strain rate and allows the assessment of LSSR and LESR

AF - atrial fibrillation; AVC - aortic valve closure; LA - left atrium; LESR - average LA longitudinal early diastolic strain rate; LS - average peak positive longitudinal systolic atrial strain; LSSR - average LA longitudinal systolic strain rate; MVC - mitral valve closure; STE - speckle-tracking echocardiography

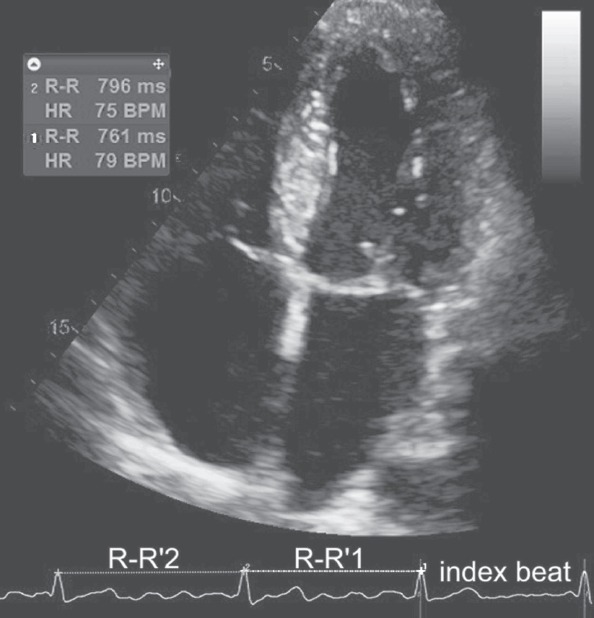

Figure 2.

The scheme of the selection of index beat during AF. The STE results were estimated using the ratio of preceding (1) to pre-preceding (2) R-R’ interval. We selected the beat with the smallest difference between prevenient R-R’ intervals

BPM - beats per minute; HR - heart rate; STE - speckle-tracking echocardiography

Statistical analysis

For continuous variables data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median (25th–75th percentiles) values. Dichotomous variables are presented as absolute values and frequencies. To verify the normality of data distribution we used D’Agostino–Pearson test. Differences in continuous parameters between groups with and without LAAT were investigated using Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test for independent samples according to the normality of distribution. For dichotomous data we applied Fisher’s exact test or χ2 test depending on sample size. We used Pearson’s coefficient to assess the correlations between particular parameters. Kappa statistics were used to determine the intraobserver and interobserver concordance in the assessment of particular STE measurements.

We generated receiver operating characteristics (ROC curves to determine the ability of different variables for discriminating between patients with and those without LAAT. The cut-off was gained using the criterion corresponding with the highest Youden index.

Regression analysis was performed to identify markers connected with LAAT. The covariates with p value ≤0.05 identified by univariate analysis were thereafter included in multivariate model in a stepwise manner. The most of univariate parameters were correlated. To avoid the problem of collinearity we constructed alternative multiple regression models for each STE result, LVEF, and iLV mass. Considering previously published findings, the models included prespecified variables such as CH2ADS2-VASc score and effective anticoagulation (14, 23). Risks were expressed as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). The possible incremental value of each univariate factor over traditional risk stratification scheme was tested. The incremental value was assessed by comparing the global χ2 value for each model.

A two-tailed probability value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The data were processed using MedCalc Software version 12.2.1 and SPSS version 20.0.

Results

Study population

Preliminary analysis excluded 11 (10.6%) patients because of suboptimal quality of transthoracic images. In TEE, interobserver discrepancies regarding LAAT vs. “sludge” differentiation involved 6 (5.8%) patients. These cases were excluded from further analysis. Finally, we enrolled into the study 36 patients with LAAT and 51 patients without LAAT as controls according to previously established criteria. Demographic, clinical, and echocardiographic data for the study group are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical and echocardiographic characteristics of patients with and without LAAT

| Parameter | Without LAAT (n=51) | With LAAT (n=36) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 65±13.5 | 70±7.5 | 0.14 |

| Gender, female, % | 24 (47) | 12 (33) | 0.27 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29 (26–33) | 28 (26–31) | 0.24 |

| Body surface area, m2 | 2±0.3 | 1.9±0.2 | 0.05 |

| Heart rate, BPM | 90±19 | 88±24 | 0.75 |

| AF, n, % | |||

| paroxysmal | 6 (12) | 1 (3) | 0.23 |

| persistent | 38 (75) | 31 (86) | 0.3 |

| permanent | 7 (14) | 4 (11) | 1 |

| CH2ADS2-VASc Score | 3.1±2.1 | 3.9±1.6 | 0.3 |

| <2, % | 10 (20) | 3 (8) | 0.22 |

| ≥2, % | 41 (80) | 33 (92) | 0.16 |

| Prior stroke or TIA, n, % | 2 (4) | 8 (22) | 0.01 |

| Hypertension, n, % | 42 (82) | 31 (86) | 0.86 |

| Heart failure, n, % | 19 (37) | 20 (56) | 0.13 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n, % | 36 (71) | 26 (72) | 0.94 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n, % | 22 (43) | 13 (36) | 0.66 |

| Coronary artery disease, n, % | 14 (27) | 18 (50) | 0.04 |

| Coronary artery bypass surgery, n, % | 3 (6) | 2 (6) | 1 |

| Post myocardial infarction, n, % | 9 (18) | 11 (31) | 0.2 |

| Smoking, n, % | 5 (10) | 3 (8) | 1 |

| Alcohol abuse, n, % | 4 (8) | 0 | 0.14 |

| Anticoagulation, n, % | 31 (61) | 24 (67) | 0.74 |

| Therapeutic anticoagulation, n, % | 23 (45) | 14 (39) | 0.66 |

| Acenocumarol, n, % | 15 (29) | 23 (64) | 0.002 |

| Warfarin, n, % | 2 (4) | 0 | 0.51 |

| Dabigatran, n, % | 7 (14) | 0 | 0.04 |

| Rivaroxaban, n, % | 7 (14) | 1 (3) | 0.13 |

| LVEF, % | 50 (40–58) | 38 (28–53) | 0.001 |

| preserved | 26 (51) | 14 (39) | 0.4 |

| mid-range | 17 (33) | 3 (8) | 0.009 |

| decreased | 8 (16) | 19 (53) | 0.0004 |

| iLV mass, g/m2 | 123±32 | 139±38 | 0.04 |

| LAA emptying velocity, cm/s | 48±17 | 26±10 | 0.0001 |

| LA anteroposterior diameter, mm/m2 | 24 (22–27) | 26 (24–28) | 0.07 |

| iLA area, cm2/m2 | 12 (10–13) | 14 (11–15) | 0.03 |

| iLA volume min, mL/m2 | 28 (22–37) | 34 (28–39) | 0.02 |

| iLA volume max, mL/m2 | 38 (31–48) | 45 (38–54) | 0.04 |

| LA total emptying fraction, % | 26±10 | 24±7 | 0.34 |

| LS-4Ch, % | 12.2±6.7 | 9.5±5.9 | 0.05 |

| LS-2CH, % | 13.2±7.1 | 9±4.6 | 0.002 |

| LS, % | 12.5±6.2 | 9.1±4.6 | 0.006 |

| LSSR-4CH, 1/s | 0.8±0.3 | 0.6±0.3 | 0.04 |

| LSSR-2CH, 1/s | 0.8±0.3 | 0.6±0.3 | 0.002 |

| LSSR, 1/s | 0.8±0.2 | 0.6±0.3 | 0.01 |

| LESR-4CH, 1/s | -1.1±0.6 | -0.7±0.4 | 0.0005 |

| LESR-2CH, 1/s | -1.1±0.5 | -0.8±0.5 | 0.01 |

| LESR, 1/s | -1.1±0.5 | -0.8±0.4 | 0.0009 |

Results are shown as mean±standard deviation, median (25th–75th percentiles) or numbers (percentages). 2CH - two-chamber; 4CH –four chamber, AF - atrial fibrillation; BPM - beats per minute; iLA - parameter indexed to body surface area; LA -left atrial; LAAT -left atrial appendage thrombus; LESR -average LA longitudinal early-diastoli strain rate; LS -average peak positive longitudinal systolic atrial strain; LSSR – average LA longitudinal systolic strain rate; LV - left ventricular; LVEF - left ventricular ejection fraction; TIA - transient ischemic attack

Demographic and clinical parameters

The prevalence of particular AF types (paroxysmal, persistent, permanent) was similar in both subgroups. There were no significant differences between these patients with respect to age, body mass index, CH2ADS2-VASc Score, hypertension, heart failure, creatinine clearance, diabetes mellitus, and percentage of patients on therapeutic anticoagulation. The prevalence of coronary artery disease was higher in the LAAT group. Thirty-one (61%) patients without LAAT was treated with anticoagulants and this treatment was administered for at least 3 weeks before TEE in proper dosage in 23 (74%) of them. In patients with LAAT, the corresponding numbers were 24 (67%) and 14 (58%) patients, respectively.

Standard echocardiographic parameters

Patients with LAAT had lower LVEF and LAA emptying velocity, higher indexed LV mass, higher indexed LA area, maximal LA volume, and minimal LA volume. Both groups were comparable with regard to LA anteroposterior diameter and LA total emptying fraction.

Speckle-tracking echocardiography results

We noticed 33 (3.2%) segments with any positive peak on strain curve. Five subjects (5.7%) had only negative average strain curve in one of view. Moreover 66 (6.3%) segments had inadequate quality and were excluded from further assessment. All obtained STE measurements were indexed by preceding to pre-preceding R–R’ ratio.

Speckle-tracking analysis revealed significant differences between groups with and without LAAT. Patients with LAAT had more pronounced impairment of LA reservoir function expressed by LS and LSSR as well as conduit function, expressed by LESR. Strain and strain rate results were similar in a comparative analysis between 4CH and 2CH views.

Observer variability

Ten studies were randomly selected for intraobserver and interobserver variability assessment. The kappa coefficient of intraobserver agreement was 0.89 for LS, 0.85 for LESR, and 0.91 for LSSR. These results reflect very good agreement. The concordance between independent observers was good and very good (kappa coefficient was 0.80 for LS, 0.78 for LESR and 0.86 for LSSR).

Factors associated with LAAT presence

Parameters showing any statistically significant diagnostic value for identifying LAAT presence in ROC curves analysis are listed in Table 2. The area under ROC curve (AUC) for the CH2ADS2-VASc Score was 0.645 and for LVEF was 0.706. The best cut-off values of the CH2ADS2-VASc Score and LVEF were >2 and ≤30%, respectively. The CHA2DS2-VASc Score and LESR had the highest negative predictive value and LVEF had the highest positive predictive value.

Table 2.

Receiver operating characteristics curves for the identifying of LAAT. Data present best case scenario

| Parameter | AUC | P | Criterion of highest diagnostic value | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Predictive value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (%) | Negative (%) | ||||||

| CH2ADS2-VASc | 0.645 | 0.01 | >2 | 89 | 49 | 55 | 86 |

| LVEF | 0.706 | 0.0004 | ≤30% | 42 | 96 | 88 | 70 |

| iLV mass | 0.618 | 0.06 | >160 g/m2 | 39 | 90 | 74 | 68 |

| iLA diameter | 0.622 | 0.04 | >23 mm/m2 | 80 | 43 | 49 | 76 |

| iLA area | 0.639 | 0.02 | >13 cm2/m2 | 58 | 71 | 58 | 71 |

| iLA volume max | 0.643 | 0.02 | >38 ml/m2 | 74 | 58 | 55 | 76 |

| iLA volume min | 0.651 | 0.01 | >28 ml/m2 | 71 | 58 | 54 | 74 |

| LS | 0.668 | 0.004 | ≤10.6% | 72 | 67 | 60 | 77 |

| LESR | 0.709 | 0.0002 | >-0.6 (1/s) | 90 | 42 | 52 | 86 |

| LSSR | 0.667 | 0.006 | ≤0.6 (1/s) | 56 | 78 | 64 | 72 |

AUC - area under receiver operating characteristics curve; iLA - parameter indexed to body surface area; LA - left atrial; LAAT - left atrial appendage thrombus; LESR - average LA longitudinal early-diastolic strain rate; LS - average peak positive longitudinal systolic atrial strain; LSSR - average LA longitudinal systolic strain rate; LV - left ventricular; LVEF - left ventricular ejection fraction

AUCs for LA planimetric and volumetric parameters varied from 0.56 in the case of LA emptying fraction to 0.651 for LA minimal volume indexed to body surface area (BSA). Indexing to BSA increased the accuracy of planimetric and volumetric measurements. AUCs for STE measurements of LA function varied from 0.668 to 0.709 (p<0.05 for all measurements).

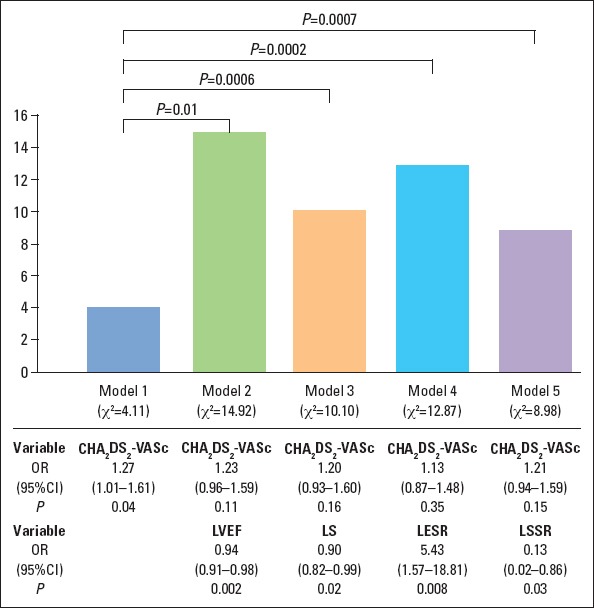

Table 3 lists univariate and multivariate parameters associated with LAAT. We observed the additional value of LVEF, LS, LESR, and LSSR over CHA2DS2-VASc Score (Fig. 3). The iLV mass was insignificant in this aspect. The multivariate factors for identifying LAAT even after adjustment for CHA2DS2-VASc and effective anticoagulation were LVEF, LS, LESR, and LSSR.

Table 3.

The factors associated with LAAT in univariate analysis and multivariate analysis after adjustment for the CH2ADS2-VASc Score and therapeutic anticoagulation

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | χ2 |

| CH2ADS2-VASc Score | 1.27 | 1.01–1.61 | 0.04 | ||||

| LVEF | 0.94 | 0.91–0.98 | 0.001 | 0.94 | 0.91–0.98 | 0.002 | 15.5 |

| iLV mass | 1.01 | 1.00–1.03 | 0.04 | 1.01 | 0.99–1.02 | 0.1 | 7.1 |

| LS | 0.89 | 0.82–0.97 | 0.005 | 0.89 | 0.82–0.98 | 0.02 | 10.6 |

| LSSR | 0.10 | 0.02–0.62 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.02–0.96 | 0.045 | 8.6 |

| LESR | 6.42 | 1.94–21.24 | 0.0005 | 5.3 | 1.5–18.3 | 0.008 | 12.7 |

CI - confidence interval; iLV mass - left ventricular mass indexed to body surface area; LAAT - left atrial appendage thrombus; LESR - average LA longitudinal early diastolic strain rate; LS - average peak positive longitudinal systolic atrial strain; LSSR - average LA longitudinal systolic strain rate; LVEF - left ventricular ejection fraction; OR - odds ratio

Figure 3.

Incremental value of left ventricular ejection fraction, left atrial longitudinal strain, systolic strain, and early diastolic strain rate over the CH2ADS2-VASc Score for the stratification of the presence of thrombi. Presented factors significantly improved χ2 value of the CH2ADS2-VASc Score

CI - confidence interval; LESR - average LA longitudinal early diastolic strain rate; LS -average peak positive longitudinal systolic atrial strain; LSSR - average LA longitudinal systolic strain rate; LVEF - left ventricular ejection fraction; OR - odds ratio

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge our study is the first one to investigate potential use of transthoracic STE to identify patients with higher probability of LAAT presence during AF. Previous studies concerning echocardiographic analysis of LA function, even in the context of AF, were mostly performed during sinus rhythm (24). Left atrial strain was documented as predictor of LAAT in patients with sinus rhythm with suspected cardioembolic stroke (12).

We analyzed population with AF. Both subgroups were similar with regard to demographic characteristics, cardiovascular risk factors, and anticoagulant therapy. The absence of difference in anticoagulation status resulted from the duration of AF and the previous implementation of treatment. We noticed many significant differences in standard and advanced echo measurements. The low or absent correlations between LA conventional and STE parameters may suggest that LA deformation has many determinants (25).

Clinical and standard echocardiographic factors associated with LAAT

To evaluate the diagnostic value of clinical data for the identification of the higher risk of LAAT we used the CH2ADS2-VASc Score—a well-established and validated scale stratifying stroke risk in AF (1). Higher values of this score has been also reported in the patients with LAAT (26). In our study, despite comparable CH2ADS2-VASc Score values in both subgroups (with and without LAAT), the score was statistically significant univariate factor of LAAT. Contrary to earlier reports our analysis did not confirm significant meaning of more sustained AF forms for thrombus formation (27). It may be hypothesized that high prevalence of risk factors (85% patients had at least the CH2ADS2-VASc Score equal 2) and sustained forms of AF in our study group was the reason for this lack of significant differences.

With regard to standard echocardiographic parameters, prior studies have shown that LVEF <40% implicates the presence of thrombus (28); our results confirm these observations. Moreover decreased LVEF is the predictor of warfarin-resistant LA thrombus (29). However, in our study another parameter previously reported (28) as the predictor of LAAT presence, i.e., LA diameter, had poor diagnostic value only after indexing for BSA. It was indicated that enlargement of LA observed in echo, independently of applied method of calculation was associated with LAAT, dense spontaneous echo contrast or LAA low flow velocity. However, indexed LA area in 4-CH view and indexed volume had the highest prognostic value (14). In our analysis standard LA echocardiographic area–length parameters had no or poor discriminative ability for the identification of thrombi. Moreover, none of them reached statistical significance in regression model. It may be explained by small variety of LA size in our group. In another study (11) LV mass measured by area–length method has predicted LAAT in persistent AF. This is partially consistent with our findings. We employed a cube formula and identified iLV mass as a univariate marker of LAAT, but without additive value over the CH2ADS2-VASc Score. Furthermore, increased LV end-diastolic pressure (typical for hypertrophy) has been associated with impaired LA filling in the analysis of changes in LA volume (30). This fact may result in impaired LA hemodynamics and contribute to the higher probability of LAAT appearance.

Speckle-tracking echocardiographic factors associated with LAAT

We demonstrated that assessment of LA strain during AF is feasible. This is consistent with previous studies (19, 26). Subgroup without LAAT had significantly higher strain and absolute strain rate values. These parameters have also been shown in previous studies to be predictive of reverse remodeling and identifying responders to cardioversion (19) and ablation (24).

Our results indicate that the worsening of LA function detected by STE is associated with the higher risk of thrombi in LAA. However, each of STE measurement had poor to fair discriminative accuracy. In multivariate model after adjustment for the CH2ADS2-VASc Score and effective anticoagulation only LVEF, LA lengthening, LA conduit, and reservoir function were independently associated with the presence of LAAT.

We also demonstrated incremental diagnostic value of LA STE measurements over established risk stratification scale in identifying patients with LAAT. Previously it was established that LS measured in 4CH and 2CH views (without roof segments) has additional value over CHA2DS2-VASc Score, but for the risk stratification of embolism in patients with AF (20). The data considering the additional value of LA strain rate are unavailable so far. Furthermore, our model of LA consisted of 12 segments.

In our study we also analyzed a number of segments with any positive peak on strain curve. Positive strain value reflects LA wall lengthening during pulmonary veins inflow. Negative strain value represents wall shortening when atrium empties into ventricle (19). Lack of positive peak represents greater stiffness and lack of compliance. We included the number of segments with only negative strain to regression model. However, it was not statistically significant factor of LAAT appearance.

Study limitations

Our study has some limitations. This is a single-center, retrospective project with a relatively small group of patients, with high incidence of risk factors and LAA thrombi, but relatively low percentage of them on full anticoagulation. Therefore, these results need to be validated in a larger, prospective study. Another limitation is high prevalence of patients with mid-range LVEF in the group without LAAT and the high percentage of heart failure with decreased LVEF in the group with LAAT. We did not analyze exact duration of arrhythmia episodes because of potential inaccuracies associated with asymptomatic course. The analysis was performed using a software dedicated for left ventricle because software for LA STE is not available. Our results cannot be directly compared to previously reported (13, 20) because of different methodology. Our analysis involved 12 LA segments, including roof segments, and global LA strain values are relatively low despite pretty normal mean LAA emptying velocities. Another limitation is that reported diagnostic values are derived from Youden index. Values of diagnostic accuracy presented in Table 2 represent the best case scenario.

Conclusions

STE may be used to describe the LA reservoir and conduit function during AF. The deformation analysis of LA function in TTE provides additional diagnostic value for discriminating between patients with and without LAAT. Left ventricular systolic dysfunction and impaired LA deformation are independent markers of LAAT in patients with AF. Analysis according to LA strain may be useful and important for the better understanding of pathophysiological conditions. Further prospective longitudinal studies in the larger group of patients are needed to validate our results, clarify raised issues and indicate their potential role in daily practice.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Authorship contributions: Concept – K.K., P.L.; Design – K.K., B.W.M., P.L.; Supervision – J.D.K., P.L.; Providing tools and instruments – J.D.K., P.L.; Materials – K.K., B.W.M., P.W.M., K.W.O.; Data collection and/or processing – K.K., D.M., P.W.M., K.W.O.; Analysis and/or interpretation – K.K., B.W.M., D.M., P.W.M., K.W.O.; Literature review – K.K., D.M.; Writing – K.K., P.L.; Critical review – J.D.K., P.L., B.W.M.

From Prof. Dr. Hasan Veysi Güneş’s collections

References

- 1.Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GY, Schotten U, Savelieva I, Ernst S, et al. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation:the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2369–429. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romero J, Cao JJ, Garcia MJ, Taub CC. Cardiac imaging for assessment of left atrial appendage stasis and thrombosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11:470–80. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirchhof P, Auricchio A, Bax J, Crijns H, Camm J, Diener HC, et al. Outcome parameters for trials in atrial fibrillation:recommendations from a consensus conference organized by the German Atrial Fibrillation Competence NETwork and the European Heart Rhythm Association. Europace. 2007;9:1006–23. doi: 10.1093/europace/eum191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uretsky S, Shah A, Bangalore S, Rosenberg L, Sarji R, Cantales DR, et al. Assessment of left atrial appendage function with transthoracic tissue Doppler echocardiography. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2009;10:363–71. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jen339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sugioka K, Fujita S, Iwata S, Ito A, Matsumura Y, Hanatani A, et al. Relationship between CHADS2 score and complex aortic plaques by transesophageal echocardiography in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2014;40:2358–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cianciulli TF, Saccheri MC, Lax JA, Bermann AM, Ferreiro DE. Two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography for the assessment of atrial function. World J Cardiol. 2010;2:163–70. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v2.i7.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kallergis EM, Goudis CA, Vardas PE. Atrial fibrillation:a progressive atrial myopathy or a distinct disease? Int J Cardiol. 2014;171:126–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nattel S, Harada M. Atrial remodeling and atrial fibrillation:recent advances and translational perspectives. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2335–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.02.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kupczynska K, Kasprzak JD, Michalski B, Lipiec P. Prognostic significance of spontaneous echocardiographic contrast detected by transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography in the era of harmonic imaging. Arch Med Sci. 2013;9:808–14. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2013.38674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maltagliati A, Galli CA, Tamborini G, Calligaris A, Doria E, Salehi R, et al. Usefulness of transoesophageal echocardiography before cardioversion in patients with atrial fibrillation and different anticoagulant regimens. Heart. 2006;92:933–8. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.071860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyd AC, McKay T, Nasibi S, Richards DA, Thomas L. Left ventricular mass predicts left atrial appendage thrombus in persistent atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;14:269–75. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jes153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karabay CY, Zehir R, Güler A, Oduncu V, Kalaycı A, Aung SM, et al. Left atrial deformation parameters predict left atrial appendage function and thrombus in patients in sinus rhythm with suspected cardioembolic stroke:a speckle tracking and transesophageal echocardiography study. Echocardiography. 2013;30:572–81. doi: 10.1111/echo.12089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuppahally SS, Akoum N, Burgon NS, Badger TJ, Kholmovski EG, Vijayakumar S, et al. Left atrial strain and strain rate in patients with paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation:relationship to left atrial structural remodeling detected by delayed-enhancement MRI. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:231–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.109.865683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faustino A, Providência R, Barra S, Paiva L, Trigo J, Botelho A, et al. Which method of left atrium size quantification is the most accurate to recognize thromboembolic risk in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation? Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2014;12:28–39. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-12-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cameli M, Lisi M, Righini FM, Mondillo S. Novel echocardiographic techniques to assess left atrial size, anatomy and function. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2012;10:4–16. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-10-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ataş H, Kepez A, Tigen K, Samadov F, Özen G, Cincin A, et al. Evaluation of left atrial volume and function in systemic sclerosis patients using speckle tracking and real-time three-dimensional echocardiography. Anatol J Cardiol. 2016;16:316–22. doi: 10.5152/AnatolJCardiol.2015.6268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurt M, Tanboğa IH, Büyükkaya E, Karakaş MF, Akçay AB, Sen N, et al. Relation of presence and severity of metabolic syndrome with left atrial mechanics in patients without overt diabetes:a deformation imaging study. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2014;14:128–33. doi: 10.5152/akd.2014.4686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miskowiec D, Kupczynska K, Michalski BW, Uznanska-Loch B, Kurpesa M, Kasprzak JD, et al. Left atrial dysfunction assessed by two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography in patients with impaired left ventricular ejection fraction and sleep-disordered breathing. Echocardiography. 2016;33:38–45. doi: 10.1111/echo.12987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dell'Era G, Rondano E, Franchi E, Marino PN Novara Atrial Fibrillation (NAIF) Study Group. Atrial asynchrony and function before and after electrical cardioversion for persistent atrial fibrillation. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2010;11:577–83. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jeq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Obokata M, Negishi K, Kurosawa K, Tateno R, Tange S, Arai M, et al. Left atrial strain provides incremental value for embolism risk stratification over CHA2DS2-VASc score and indicates prognostic impact in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2014;27:709–16. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults:an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16:233–70. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jev014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kusunose K, Yamada H, Nishio S, Tomita N, Hotchi J, Bando M, et al. Index-beat assessment of left ventricular systolic and diastolic function during atrial fibrillation using myocardial strain and strain rate. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2012;25:953–9. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ayirala S, Kumar S, O'Sullivan DM, Silverman DI. Echocardiographic predictors of left atrial appendage thrombus formation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2011;24:499–505. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Motoki H, Negishi K, Kusunose K, Popović ZB, Bhargava M, Wazni OM, et al. Global left atrial strain in the prediction of sinus rhythm maintenance after catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2014;27:1184–92. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2014.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim D, Shim CY, Hong GR, Kim MH, Seo J, Cho IJ, et al. Clinical implications and determinants of left atrial mechanical dysfunction in patients with stroke. Stroke. 2016;47:1444–51. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Providência R, Faustino A, Paiva L, Trigo J, Botelho A, Nascimento J, et al. Cardioversion safety in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation:which patients can be spared transesophageal echocardiography? Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2012;23:597–602. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e3283562d4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wysokinski WE, Ammash N, Sobande F, Kalsi H, Hodge D, McBane RD. Predicting left atrial thrombi in atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J. 2010;159:665–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleemann T, Becker T, Strauss M, Schneider S, Seidl K. Prevalence and clinical impact of left atrial thrombus and dense spontaneous echo contrast in patients with atrial fibrillation and low CHADS2 score. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2009;10:383–8. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jen256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watanabe A, Yamashita N, Yamashita T. Blood stasis secondary to heart failure forms warfarin-resistant left atrial thrombus. Int Heart J. 2014;55:506–11. doi: 10.1536/ihj.14-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Küçük U, Küçük HO, Demirkol S, İyisoy A. Left atrial deformation parameters predict left atrial appendage function and thrombus in patients in sinus rhythm with suspected cardioembolic stroke:a speckle tracking and transesophageal echocardiography study:left atrial filling and emptying velocities as indicators of left atrial mechanics. Echocardiography. 2013;30:860–1. doi: 10.1111/echo.12230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]