ABSTRACT

The last few years have seen the advancement of high-throughput experimental techniques that have produced an extraordinary amount of data. Bioinformatics and statistical analyses have become instrumental to interpreting the information coming from, e.g., sequencing data and often motivate further targeted experiments. The broad discipline of “computational biology” extends far beyond the well-established field of bioinformatics, but it is our impression that more theoretical methods such as the use of mathematical models are not yet as well integrated into the research studying microbial interactions. The empirical complexity of microbial communities presents challenges that are difficult to address with in vivo/in vitro approaches alone, and with microbiology developing from a qualitative to a quantitative science, we see stronger opportunities arising for interdisciplinary projects integrating theoretical approaches with experiments. Indeed, the addition of in silico experiments, i.e., computational simulations, has a discovery potential that is, unfortunately, still largely underutilized and unrecognized by the scientific community. This minireview provides an overview of mathematical models of natural ecosystems and emphasizes that one critical point in the development of a theoretical description of a microbial community is the choice of problem scale. Since this choice is mostly dictated by the biological question to be addressed, in order to employ theoretical models fully and successfully it is vital to implement an interdisciplinary view at the conceptual stages of the experimental design.

KEYWORDS: interdisciplinary approaches, marine ecosystems, mathematical modeling, microbial communities

INTRODUCTION

Theoretical biology is a very broad field where mathematical and physical concepts are used to describe biological systems. Computational models are being widely applied in the investigation of biological phenomena, and their potential goes well beyond simply reproducing and validating experimental data. To achieve predictive power, however, a theoretical model needs to be fully integrated into the experimental design. Indeed, modeling techniques are very diverse and their efficacy is highly specific to the problem scale and the objective of the study. The selection of the most appropriate method for the question at hand depends not only on the intuition and experience of the modeler but also on the type and quality of the data available (1). This is why it is crucial that modelers and experimentalists come together at the conceptual stages of a project to jointly plan experiments, measurements, and data management. An experimental protocol design that ignores the modeling aspect is set up to obtain data that would most likely be suboptimal for modeling.

The research interest in microbial communities is gaining momentum, and we think that now is the time for setting new standards in the scientific methods for understanding and potentially engineering such complex systems. It is our impression that rapid technological advances in experimental techniques providing high-throughput data are not accompanied by proportional advances in the theoretical methods to interpret them systematically. Interdisciplinary studies of microbial consortia are becoming more common (2) but are still exceptions rather than the norm, especially if compared to the fields of ecology (3) and metabolism (4), where mathematics has since long been integrated. In this minireview, we want to provide a glimpse of the broad ranges of available mathematical models. We use the example of marine ecosystems with their wide variation of complexity scales to highlight how experiments and theory can be successfully paired, with the goal of motivating scientists to engage in a multidisciplinary approach for understanding microbial interactions.

MATHEMATICAL MODELS FROM THE OCEAN TO THE PHYCOSPHERE

Classical terminology defines an ecosystem as a community of living organisms interacting with one another and with the physical environment. Covering approximately 70% of Earth's surface and contributing to one-half of global primary production (5, 6), the ocean is the largest biome on our planet and provides illustrative examples of ecosystems exhibiting spatial and temporal heterogeneity. With an estimated 104 to 106 cells per milliliter (7), marine microbes make up the vast majority of oceanic biomass but have historically been ignored by oceanographers (8). We have only recently begun to understand their importance in fundamental phenomena such as biogeochemical cycling and primary productivity which play vital roles in the ability of animals and plants to exist and thrive on Earth. Members of the plankton ecosystem (viruses, bacteria, archaea, protists, and metazoans) have recently been systematically collected in their natural habitats (9) to explore ecosystem dynamics at the ocean scale. However, much is still unknown about how these microorganisms interact with one another (Table 1 provides examples of marine microbial interactions).

TABLE 1.

Types of marine microbial interactions

| Relationship | Diagram | Example | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutualism |  |

A Sulfitobacter species promoted cell division of a coastal diatom, Pseudo-nitzschia multiseries, via secretion of the auxin phytohormone indole-3-acetic acid synthesized by the bacterium using diatom-secreted tryptophan | 10, 11 |

| Competition |  |

Competition for “free” orthophosphates in the predominantly nutrient-limited marine biome; marine bacteria are better competitors for phosphorus than eukaryotic algae at low ambient nutrient concentrations | 12–15 |

| Parasitism |  |

Lytic viral infection of other single-celled organisms by attachment of virus to a host cell and injection of its nucleic acid into the cell, directing the host to produce numerous progeny viruses; these are released by fatal bursting of the cell, allowing the cycle to begin again | 16–18 |

| Predation |  |

Ciliated bacteriovores in marine environments such as aloricate oligotrichous ciliates graze on bacteria | 19–21 |

| Commensalism |  |

Certain bacteria found in the algal sheath where they look for carbon and shelter with no effect on the algal host | 22, 23 |

| Amensalism |  |

Marine bacteria such as Kordia algicida and Pseudoalteromonas sp. strain A28 can secrete enzymes capable of lysing diatoms | 24–26 |

| Neutralism |  |

A debated phenomenon, often suggested to rarely exist in natural communities but possibly occurring in ecosystem structures where two species are too far apart spatially; industrial examples exist; e.g., the population densities of a Lactobacillus sp. and a Streptococcus sp. grown in continuous culture were observed to be similar in mixed cultures and in individual cultures | 27–29 |

A wide range of theoretical modeling techniques has been developed to address different temporal and spatial scales. The flexibility of a model, combined with rigorous mathematical thinking, allows the translation of working hypotheses into reproducible in silico experiments. In this way, mechanistic insights into fundamental processes as diverse as evolution and metabolism can be gained. The relatively low cost of generating copious amounts of simulated data enables testing of an assortment of hypotheses with a freedom not achievable with in vivo/in vitro experiments. With this freedom, however, comes the risk of deviating from biologically meaningful results, and it is therefore necessary to plan a continuous and reciprocal integration of simulations and experiments. In this section, we provide a short overview of mathematical methods used to model microbial communities with a focus on ocean-wide systems, biofilms, and the phycosphere. The reader interested in more extended reviews of mathematical modeling of microbes is referred to references 27 and 30.

DIFFERENT UNITS FOR DIFFERENT QUESTIONS

A general rule when developing a mathematical model is that one should keep it “as simple as it can be, but not simpler” (words attributed to Albert Einstein by the writer and composer Roger Sessions in 1950). As simple as it sounds, this remains one of the main challenges in modeling, as a “combinatorial explosion” of the number of variables and parameters can easily occur. This is particularly true in natural microbial ecosystems, where diversity levels are high and countless cell-to-cell and cell-to-environment interactions can be considered. Ranging from meters to kilometers in size, large marine ecosystems include relatively permanent systems such as coral reefs and salt marshes but also temporary phenomena such as algal blooms (31). Spanning meters to millimeters, marine biofilms are found on mineral macrostructures (e.g., rocks) and man-made infrastructures (e.g., ships) but also on small-scale organic and inorganic matter in oceans (“marine snow”) (87). Biofilms are the result of growth and aggregation of microbial organisms and their exudates, particularly extracellular polymeric substances, on a surface (32, 33). Zooming in to the micro- and nanometer scale, cell-to-cell relationships include interactions that occur in the phycosphere, a term coined by Bell and Mitchell in 1972 (34) to denote the region extending outward from the microalgal cell in which bacterial growth is stimulated by extracellular products of the eukaryote.

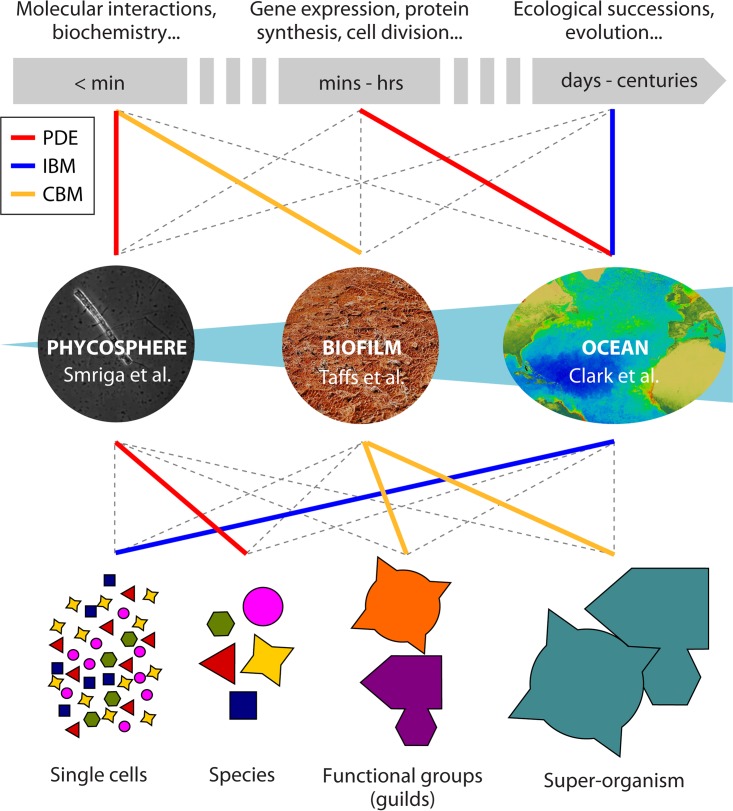

Different levels of abstraction can be defined, determined by the community dynamics at the core of the research question. Figure 1 illustrates examples of the scales at which systems of the marine biome can be investigated independently of their actual size. Starting from single-cell resolution, we can first average individuals as a whole population (species) and then further reduce the complexity by considering functional groups (also called guilds) of species performing the same role in the ecosystem and finally define a single superorganism interacting with the environment. The choice of problem scaling is determined by the research question and is not directly related to the physical size of the biological system. For example, effective models can be built of oceanic ecosystems at the cell level and of a bacterial culture as a single superorganism. A similar argument holds for temporal scales, with the difference being that the time scale is an intrinsic characteristic of the phenomenon being addressed. Indeed, the same ecosystem can be investigated at the biochemical level or in an evolutionary perspective, a choice that will set the time constants at the order of fractions of seconds or centuries, respectively.

FIG 1.

Schematic representation of different choices of temporal (top) and spatial (bottom) scales for the same ecosystem (center). PDE, IBM, and CBM methods are represented with red, blue, and yellow lines, respectively. Smriga et al. (80) used PDE to model a phycosphere community at the species level (picture from Smriga et al. [80]). Taffs et al. (74) used CBM to model a biofilm at the guild and superorganism levels (the picture of thermophilic bacteria in Mickey Hot Springs, Oregon, is from https://en.wikipedia.org [contributed by Amateria1121]). Clark et al. (53) used IBM plus PDE to model an ocean system at the single-cell level (the ocean picture is from the SeaWiFS instrument [https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/]).

POPULATION MODELS

Population-scale models were among the earliest applications of mathematical models, dating back to 1838 when the mathematician Verhulst developed the equation that describes logistic growth (35). Almost a century later, Lotka (36) and Volterra (37) independently described the oscillatory behavior of multispecies populations with a system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs), developing one of the first ecosystem models. ODEs describe the temporal change of a variable (e.g., a population) as a function of other dynamic variables as well as of parameters that define external (e.g., environmental) factors. One variable may positively (if it causes an increase) or negatively (if it causes a reduction) influence another variable. ODEs do not include spatial inhomogeneities, but these can be described by partial differential equations (PDEs). Due to their versatility and ease of implementation, differential equations (38) are among the tools most widely used in kinetic modeling methods and have been applied to understand phenomena in fields such as economics, hydrodynamics, and biochemistry.

Table 1 illustrates how microbial interactions can be classified into positive, negative, and neutral actions. Deciphering the interplay between the microbial population and the physicochemical environment is a critical step to further understanding and predicting phenomena related to ecological succession (39). In 1946, Gordon Arthur Riley was arguably the first to describe the phytoplankton annual cycle with mathematical models based on concentrations of dissolved nutrients, solar radiation, and other environmental factors (40, 41). Recent advancements in network inference techniques have allowed the reconstruction of interaction networks from co-occurrence patterns in time series of metagenomic sequencing data (42). Such networks are used to build generalized Lotka-Volterra (gLV) models, where each species is parameterized with a growth rate and a strength of interaction with other community members (43).

Hoffmann et al. (44) developed a gLV model to describe the dynamics of marine phages preying on bacteria (45). They tested different population distributions to explain metagenomics data from shotgun experiments performed on natural marine phage communities and found a modified gLV model to fit the data best. The equation form of the model is interpreted as a cooperation mechanism for phage predation and predicts that the community follows kill-the-winner dynamics where blooming periods are followed by rapid decay. As was demonstrated in gLV models of gut bacteria communities (46), other effects such as environmental perturbations can be also introduced.

INDIVIDUAL-BASED MODELS

Conventionally, mathematical models based on differential equations are deterministic and do not capture effects of stochastic processes. Individual-based models (IBMs) (47)—sometimes referred to as “agent-based models”—implement Monte Carlo techniques to introduce the randomness required to model the dynamics of single individuals. In these discrete models, each unit temporally evolves to the next stage according to probabilistic rules, making them ideal for describing the single-cell level. High degrees of complexity can be introduced to account for interaction mechanisms as well as individual variability, parameterized as metabolic states and mutation rates, to name two. IBMs are widely used in diverse disciplines and can be successfully applied to describe different temporal and spatial resolutions (47, 48).

A comprehensive review by Costerton et al. (49) reports that biofilms predominate, numerically and metabolically, in virtually all nutrient-sufficient ecosystems. Understanding the metabolic cooperation dynamics is fundamental, and the bacterial composition (relative abundance and spatial distribution of the species) of a biofilm is mainly determined by three processes that take place within the film: (i) conversion of substrates by bacteria, (ii) volume expansion of biomass, and (iii) transport of substrates by molecular diffusion. Early models of biofilm development used a set of mass balance PDEs (50, 51), and IBMs (adding individual variability factors) and PDEs (describing molecular diffusion) have been extensively combined over the last decade. Within a model, however, different scales have to be carefully integrated in a theoretically justified manner. For example, processes occurring over shorter time scales can be considered to be in a quasi-steady state in comparison to processes occurring over longer time scales. This is the case in the framework proposed by Lardon et al. (52), where solute diffusion and reaction dynamics are considered to be in a quasi-steady state with respect to biomass growth. They investigated individual metabolic switching in response to environmental changes in a community of denitrifying bacteria and identified a tradeoff between cost and response time, explaining the maintenance of different denitrifying strategies in fluctuating environments.

Despite the correlation between increasing system size and computational “cost,” Clark et al. (53) implemented IBMs to model an ocean-scale system. The authors developed a trait-based model where a single agent represents individuals with identical traits. An ocean PDE model discretized into cell grids provides the environmental conditions (temperature, salinity, and diffusion of dissolved nutrients), and agents are mixed between the spatial units. By performing simulations on an evolutionary time scale, it was demonstrated that different environments select for different traits such as cell size in phytoplankton.

METABOLIC NETWORK MODELS

By correctly assigning metabolic functions to the enzymes encoded in a whole genome, it is possible to obtain a genome-scale metabolic network model (54, 55). This reconstruction is close to becoming an automated process (56, 57), but it still requires careful manual curation thereafter, because incomplete or inaccurate genome annotations can lead to unreliable models (58). Various mathematical methods have been developed to analyze metabolic network models. Network expansion (59) is an error-tolerant qualitative method useful to infer minimal nutrient requirements (60) and to classify organisms by lifestyle based on their metabolic capabilities (61). Christian et al. (62) demonstrated how the range of possible biosynthetic products increases if two or more organisms cooperate on a metabolic level, illustrating the potential of synergistic interactions of organisms (including bacteria). Stoichiometric models (4, 63, 64) are mathematical representations of metabolic networks in the form of a matrix with the stoichiometric coefficients of the reactions present as elements. At the steady state, the requirement of mass balance translates into a mathematical system of equations whose solutions represent feasible metabolic fluxes. Because the solution is not unique, constraint-based models (CBMs) (65–67) impose biophysically motivated boundary conditions with respect to reaction rates in order to reduce the space of possible flux distributions. Elementary mode analysis (EMA) (68, 69) identifies all minimal subnetworks that allow a steady-state solution, thus reducing the complexity of the original network. The widely used flux balance analysis (FBA) (88) method finds a unique solution by defining an objective function to be optimized with linear programming. “Optimality” is, however, a rather subjective concept, and what optimality means for an organism is debatable (70), particularly in considering not only single organisms but also diverse communities. An extended list of examples of CBMs of microbial systems is nicely summarized in reference 89.

The typical application of CBMs is at the species level or at a higher abstraction level (Fig. 1), with the flux distribution of a single model representing the average metabolic state of a population. Examples of CBMs taking into account interspecies interactions include lumping the metabolic networks of different organisms together into a single superorganism (71) or treating different species as separate compartments, where metabolite sharing is simulated as intracompartment fluxes (72, 73). In their theoretical work, Taffs et al. (74) used EMA to study a biofilm community of sulfate-reducing bacteria, cyanobacteria, and filamentous anoxygenic phototrophs, modeled both as compartmentalized functional guilds and as a superorganism. Compared to measured data on bacterial abundances, their models offer insights into fundamental ecological questions on community composition and robustness. In particular, the identification of interguild classes of metabolic interactions associated with many elementary modes suggests the importance of such interactions to stabilization of the community.

INTEGRATION OF MODELS, EXPERIMENTS, AND DIFFERENT SCALES

Figure 1 illustrates the key concept that the same ecosystem can be approached at different temporal and spatial scales. The integration of different methods and scales has to be theoretically justified. In dynamic FBA (dFBA) (75), for example, metabolism is considered to occur faster than external metabolite concentration changes and it is modeled with CBMs at a quasi-steady state, whereas the slower external dynamics are modeled as differential equations. dFBA has been used on compartmentalized community models (76–78), and Harcombe et al. (79) coupled these temporal dynamics with spatial discretization in a modeling framework that integrates dFBA and PDEs. Simulations of cross-feeding bacterial communities could predict cooperation and competition dynamics emerging from the spatial distribution of colonies and nutrients, followed by experimental verification.

Smriga et al. (80) studied how oligotrophic (nonmotile) and copiotrophic (motile) bacteria compete for dissolved organic matter (DOM) (organic material that is <0.7 μm in size) (90) in the phycosphere. It is estimated that up to 50% of carbon fixed via phytoplankton-mediated photosynthesis is utilized by marine bacteria (81), mainly as DOM. DOM from phytoplankton originates either from live cells or from recently lysed or grazed cells, and the quality of DOM available shapes the bacterial community in the phycosphere (82, 83). Using time-lapse microscopy, Smriga et al. measured the spatiotemporal distribution of bacteria in the phycosphere. These data were used to develop a PDE model quantifying how DOM production and consumption select for bacterial chemotaxis traits. Their results offer insights into mechanisms that can drive larger-scale ecological succession. Such a model could be, in principle, coupled to approaches like Klitgord and Segrè's (84), where CBMs are used to investigate environmental conditions driving commensalism and mutualism for different pairs of bacteria.

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

Most of our current understanding of the natural world comes from meticulous ecological and physiological studies, more recently complemented by modern high-throughput techniques such as metagenomics surveys. As this knowledge was largely driven by successful exploratory approaches, we strongly believe that it is time to develop more extensively hypothesis-driven methods to advance the field from a purely descriptive representation to a sound biological theory. This minireview presents examples of mathematical models developed to address specific biological questions related to microbial communities. We argue that modelers and experimentalists must work together from the conceptual phases of the project design to ensure correct integration of theory and experiments. In this way, a common interdisciplinary language will be developed that will aid in the unraveling of mechanisms that lie at the heart of complex natural phenomena such as microbial interactions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are supported by funding from the European Commission Seventh Framework Programme (FP7 PITN-GA-2012-316427) and from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (EXC-1028-CEPLAS).

We thank Patrick Lane (ScEYEnce Studios) for graphical enhancement of Fig. 1.

Biographies

Antonella Succurro completed her Ph.D. in physics at the Institut de Fisica de Altas Energias (Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain) as a member of the ATLAS Collaboration (CERN, Geneva, Switzerland). Soon thereafter, she joined the Institute for Quantitative and Theoretical Biology (Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany) to follow her interest in applying analytical methods to the study of biological systems. She developed kinetic and metabolic models to study the dynamics of bacterial communities associated with microalgae (85) and the effect of cofactors on metabolic regulation. She is now a fellow of the Cluster of Excellence on Plant Sciences (University of Cologne, Germany) and collaborates closely with experimentalists to understand bacterial communities associated with plant roots. Her current research integrates computational biology, statistical analysis, and network modeling to obtain a comprehensive picture of community assembly in the rhizosphere, with a focus on metabolism and environmental factors. She is a strong supporter of open science.

Fiona Wanjiku Moejes received a Ph.D. in biology from Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany, and is currently the micro- and macroalgal principal investigator at Bantry Marine Research Station (Ireland). Her Ph.D. research focused on the microbial community associated with marine algae, unveiling a dynamic bacterial community affected by the temporal evolution of the algal culture and by the presence/absence of certain nutrients (85). Her research is based on a multispecies community-based approach that will allow the sustainable management of resources in industry. This multidisciplinary task requires plant/algal and microbial biotechnology to be coupled with mathematical modelling systems, chemical engineering, economic feasibility studies, and the support of policymakers and legislative bodies. Born on the shores of Lake Nakuru (Kenya), Fiona is also keen to create awareness of the potential of algal biotechnology as a sustainable development tool in Africa and to incentivize algal research, particularly on native species, by researchers in Africa (86).

Oliver Ebenhöh is a physicist by training and received his Ph.D. in theoretical biophysics at the Humboldt University in Berlin. He is now professor for quantitative and theoretical biology at Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany. Considering evolution and metabolism to be inherently open systems far from equilibrium, he combines methods from statistical thermodynamics and computational biology, aiming at making these fundamental processes predictable by optimality principles. A key research issue is that of understanding how the dynamics and stability of complex microbial ecosystems can be explained by cooperation and competition of the metabolic networks of the involved organisms. Using the method of network expansion (59) developed in his group, he has shown how the network structure allows researchers to draw conclusions with regard to the lifestyle of microorganisms (61) and how synergies of cooperating metabolisms in an ecosystem can be quantified (62), setting the basis for novel theoretical approaches to study ecosystems from a metabolic perspective.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pfau T, Christian N, Ebenhöh O. 2011. Systems approaches to modelling pathways and networks. Brief Funct Genomics 10:266–279. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elr022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Widder S, Allen RJ, Pfeiffer T, Curtis TP, Wiuf C, Sloan WT, Cordero OX, Brown SP, Momeni B, Shou W, Kettle H, Flint HJ, Haas AF, Laroche B, Kreft JU, Rainey PB, Freilich S, Schuster S, Milferstedt K, van der Meer JR, Groβkopf T, Huisman J, Free A, Picioreanu C, Quince C, Klapper I, Labarthe S, Smets BF, Wang H; Isaac Newton Institute Fellows, Soyer OS. 2016. Challenges in microbial ecology: building predictive understanding of community function and dynamics. ISME J 10:2557–2568. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray JD. 2004. Mathematical biology. Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heinrich R, Schuster S. 1996. The regulation of cellular systems. Springer, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Field CB. 1998. Primary production of the biosphere: integrating terrestrial and oceanic components. Science 281:237–240. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5374.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falkowski PG. 1998. Biogeochemical controls and feedbacks on ocean primary production. Science 281:200–206. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5374.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitman WB, Coleman DC, Wiebe WJ. 1998. Prokaryotes: the unseen majority. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:6578–6583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azam F, Malfatti F. 2007. Microbial structuring of marine ecosystems. Nat Rev Microbiol 5:782–791. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karsenti E, Acinas SG, Bork P, Bowler C, De Vargas C, Raes J, Sullivan M, Arendt D, Benzoni F, Claverie J-M, Follows M, Gorsky G, Hingamp P, Iudicone D, Jaillon O, Kandels-Lewis S, Krzic U, Not F, Ogata H, Pesant S, Reynaud EG, Sardet C, Sieracki ME, Speich S, Velayoudon D, Weissenbach J, Wincker P. 2011. A holistic approach to marine eco-systems biology. PLoS Biol 9:e1001177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maruyama A, Maeda M, Simidu U. 1989. Microbial production of auxin indole-3-acetic acid in marine sediments. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 58:69–75. doi: 10.3354/meps058069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amin S, Hmelo LR, van Tol HM, Durham BP, Carlson LT, Heal KR, Morales RL, Berthiaume CT, Parker MS, Djunaedi B, Ingalls AE, Parsek MR, Moran MA, Armbrust EV. 2015. Interaction and signalling between a cosmopolitan phytoplankton and associated bacteria. Nature 522:98–101. doi: 10.1038/nature14488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jansson M. 1988. Phosphate uptake and utilization by bacteria and algae. Hydrobiologia 170:177–189. doi: 10.1007/BF00024904. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simon M, Azam F. 1989. Protein content and protein synthesis rates of planktonic marine bacteria. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 51:201–213. doi: 10.3354/meps051201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thingstad T, Skjoldal E, Bohne R. 1993. Phosphorus cycling and algal-bacterial competition in Sandsfjord, western Norway. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 99:239–259. doi: 10.3354/meps099239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karl DM. 2000. Aquatic ecology. Phosphorus, the staff of life. Nature 406:31–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Middelboe M, Jorgensen N, Kroer N. 1996. Effects of viruses on nutrient turnover and growth efficiency of noninfected marine bacterioplankton. Appl Environ Microbiol 62:1991–1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuhrman JA. 1999. Marine viruses and their biogeochemical and ecological effects. Nature 399:541–548. doi: 10.1038/21119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suttle CA. 2005. Viruses in the sea. Nature 437:356–361. doi: 10.1038/nature04160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sherr EB, Sherr BF. 1987. High rates of consumption of bacteria by pelagic ciliates. Nature 325:710–711. doi: 10.1038/325710a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fenchel T. 1988. Marine plankton food chains. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 19:19–38. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.19.1.19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pernthaler J. 2005. Predation on prokaryotes in the water column and its ecological implications. Nat Rev Microbiol 3:537–546. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramanan R, Kim BH, Cho DH, Oh HM, Kim HS. 2016. Algae-bacteria interactions: evolution, ecology and emerging applications. Biotechnol Adv 34:14–29. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cho D-H, Ramanan R, Heo J, Lee J, Kim B-H, Oh H-M, Kim H-S. 2015. Enhancing microalgal biomass productivity by engineering a microalgal–bacterial community. Bioresour Technol 175:578–585. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.10.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee S, Kato J, Takiguchi N, Kuroda A, Ikeda T. 2000. Involvement of an extracellular protease in algicidal activity of the marine bacterium Pseudoalteromonas sp. strain A28. Appl Environ Microbiol 66:4334–4339. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.10.4334-4339.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sohn JH. 2004. Kordia algicida gen. nov., sp. nov., an algicidal bacterium isolated from red tide. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 54:675–680. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02689-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paul C, Pohnert G. 2011. Interactions of the algicidal bacterium Kordia algicida with diatoms: regulated protease excretion for specific algal lysis. PLoS One 6:e21032. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song H-S, Cannon W, Beliaev A, Konopka A. 2014. Mathematical modeling of microbial community dynamics: a methodological review. Processes 2:711–752. doi: 10.3390/pr2040711. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.James GA, Beaudette L, Costerton JW. 1995. Interspecies bacterial interactions in biofilms. J Ind Microbiol 15:257–262. doi: 10.1007/BF01569978. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis P. 1967. A note on the continuous flow culture of mixed populations of lactobacilli and streptococci. J Appl Bacteriol 30:406–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1967.tb00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zomorrodi AR, Segrè D. 2016. Synthetic ecology of microbes: mathematical models and applications. J Mol Biol 428:837–861. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smayda T. 1997. Harmful algal blooms: their ecophysiology and general relevance to phytoplankton blooms in the sea. Limnol Oceanogr 42:1137–1153. doi: 10.4319/lo.1997.42.5_part_2.1137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davey ME, O'toole GA. 2000. Microbial biofilms: from ecology to molecular genetics. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 64:847–867. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.64.4.847-867.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salta M, Wharton JA, Blache Y, Stokes KR, Briand J-F. 2013. Marine biofilms on artificial surfaces: structure and dynamics. Environ Microbiol 15:2879–2893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bell W, Mitchell R. 1972. Chemotactic and growth responses of marine bacteria to algal extracellular products. Biol Bull 143:265–277. doi: 10.2307/1540052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verhulst P-F. 1838. Notice sur la loi que la population suit dans son accroissement. Corresp Math Phys 10:113–121. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lotka A. 1925. Elements of physical biology. Williams & Wilkins Company, Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Volterra V. 1926. Fluctuations in the abundance of a species considered mathematically. Nature 118:558–560. doi: 10.1038/118558a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holmes EE, Lewis MA, Banks JE, Veit RR. 1994. Partial differential equations in ecology: spatial interactions and population dynamics. Ecology 75:17–29. doi: 10.2307/1939378. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Odum EP. 1969. The strategy of ecosystem development. Science 164:262–270. doi: 10.1126/science.164.3877.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Riley GA. 1946. Factors controlling phytoplankton populations on Georges Bank. J Mar Res 6:54–73. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson TR, Gentleman WC. 2012. The legacy of Gordon Arthur Riley (1911–1985) and the development of mathematical models in biological oceanography. J Mar Res 70:1–30. doi: 10.1357/002224012800502390. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Faust K, Lahti L, Gonze D, de Vos WM, Raes J. 2015. Metagenomics meets time series analysis: unraveling microbial community dynamics. Curr Opin Microbiol 25:56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Faust K, Raes J. 2012. Microbial interactions: from networks to models. Nat Rev Microbiol 10:538–550. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoffmann KH, Rodriguez-Brito B, Breitbart M, Bangor D, Angly F, Felts B, Nulton J, Rohwer F, Salamon P. 2007. Power law rank–abundance models for marine phage communities. FEMS Microbiol Lett 273:224–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gavin C, Pokrovskii A, Prentice M, Sobolev V. 2006. Dynamics of a Lotka-Volterra type model with applications to marine phage population dynamics. J Phys Conf Ser 55:80–93. doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/55/1/008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stein RR, Bucci V, Toussaint NC, Buffie CG, Rätsch G, Pamer EG, Sander C, Xavier JB. 2013. Ecological modeling from time-series inference: insight into dynamics and stability of intestinal microbiota. PLoS Comput Biol 9:e1003388. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grimm V, Berger U, Bastiansen F, Eliassen S, Ginot V, Giske J, Goss-Custard J, Grand T, Heinz SK, Huse G, Huth A, Jepsen JU, Jørgensen C, Mooij WM, Müller B, Pe'er G, Piou C, Railsback SF, Robbins AM, Robbins MM, Rossmanith E, Rüger N, Strand E, Souissi S, Stillman RA, Vabø R, Visser U, DeAngelis DL. 2006. A standard protocol for describing individual-based and agent-based models. Ecol Modell 198:115–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2006.04.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hellweger FL, Clegg RJ, Clark JR, Plugge CM, Kreft J-U. 2016. Advancing microbial sciences by individual-based modelling. Nat Rev Microbiol 14:461–471. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Costerton JW, Lewandowski Z, Caldwell DE, Korber DR, Lappin-Scott HM. 1995. Microbial biofilms. Annu Rev Microbiol 49:711–745. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.003431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wanner O, Gujer W. 1986. A multispecies biofilm model. Biotechnol Bioeng 28:314–328. doi: 10.1002/bit.260280304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wanner O, Reichert P. 1996. Mathematical modeling of mixed-culture biofilms. Biotechnol Bioeng 49:172–184. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lardon LA, Merkey BV, Martins S, Dötsch A, Picioreanu C, Kreft J-U, Smets BF. 2011. iDynoMiCS: next-generation individual-based modelling of biofilms. Environ Microbiol 13:2416–2434. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clark JR, Lenton TM, Williams HTP, Daines SJ. 2013. Environmental selection and resource allocation determine spatial patterns in picophytoplankton cell size. Limnol Oceanogr 58:1008–1022. doi: 10.4319/lo.2013.58.3.1008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thiele I, Palsson BØ. 2010. A protocol for generating a high-quality genome-scale metabolic reconstruction. Nat Protoc 5:93–121. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Durot M, Bourguignon P-Y, Schachter V. 2009. Genome-scale models of bacterial metabolism: reconstruction and applications. FEMS Microbiol Rev 33:164–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00146.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fell DA, Poolman MG, Gevorgyan A. 2010. Building and analysing genome-scale metabolic models. Biochem Soc Trans 38:1197–1201. doi: 10.1042/BST0381197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Henry CS, DeJongh M, Best AA, Frybarger PM, Linsay B, Stevens RL. 2010. High-throughput generation, optimization and analysis of genome-scale metabolic models. Nat Biotechnol 28:977–982. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ravikrishnan A, Raman K. 2015. Critical assessment of genome-scale metabolic networks: the need for a unified standard. Brief Bioinform 16:1057–1068. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbv003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Handorf T, Ebenhöh O, Heinrich R. 2005. Expanding metabolic networks: scopes of compounds, robustness, and evolution. J Mol Evol 61:498–512. doi: 10.1007/s00239-005-0027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Handorf T, Christian N, Ebenhöh O, Kahn D. 2008. An environmental perspective on metabolism. J Theor Biol 252:530–537. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2007.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ebenhöh O, Handorf T. 2009. Functional classification of genome-scale metabolic networks. EURASIP J Bioinform Syst Biol 2009:570456. doi: 10.1155/2009/570456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Christian N, Handorf T, Ebenhöh O. 2007. Metabolic synergy: increasing biosynthetic capabilities by network cooperation. Genome Informatics 18:320–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fell DA, Small JR. 1986. Fat synthesis in adipose tissue. An examination of stoichiometric constraints. Biochem J 238:781–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Varma A, Boesch BW, Palsson BO. 1993. Stoichiometric interpretation of Escherichia coli glucose catabolism under various oxygenation rates. Appl Environ Microbiol 59:2465–2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bordbar A, Monk JM, King ZA, Palsson BO. 2014. Constraint-based models predict metabolic and associated cellular functions. Nat Rev Genet 15:107–120. doi: 10.1038/nrg3643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hanemaaijer M, Roeling WFM, Olivier BG, Khandelwal RA, Teusink B, Bruggeman FJ. 2015. Systems modeling approaches for microbial community studies: from metagenomics to inference of the community structure. Front Microbiol 6:213. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gottstein W, Olivier BG, Bruggeman FJ, Teusink B. 2016. Constraint-based stoichiometric modelling from single organisms to microbial communities. J R Soc Interface 13:20160627. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2016.0627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schuster S, Hilgetag C. 1994. On elementary flux modes in biochemical reaction systems at steady state. J Biol Syst 2:165–182. doi: 10.1142/S0218339094000131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schuster S, Dandekara T, Fell DA. 1999. Detection of elementary flux modes in biochemical networks: a promising tool for pathway analysis and metabolic engineering. Trends Biotechnol 17:53–60. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(98)01290-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schuetz R, Kuepfer L, Sauer U. 2007. Systematic evaluation of objective functions for predicting intracellular fluxes in Escherichia coli. Mol Syst Biol 3:119. doi: 10.1038/msb4100162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rodríguez J, Kleerebezem R, Lema JM, van Loosdrecht MCM. 2006. Modeling product formation in anaerobic mixed culture fermentations. Biotechnol Bioeng 93:592–606. doi: 10.1002/bit.20765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stolyar S, Van Dien S, Hillesland KL, Pinel N, Lie TJ, Leigh JA, Stahl DA. 2007. Metabolic modeling of a mutualistic microbial community. Mol Syst Biol 3:92. doi: 10.1038/msb4100131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Khandelwal RA, Olivier BG, Röling WFM, Teusink B, Bruggeman FJ. 2013. Community flux balance analysis for microbial consortia at balanced growth. PLoS One 8:e64567. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Taffs R, Aston JE, Brileya K, Jay Z, Klatt CG, McGlynn S, Mallette N, Montross S, Gerlach R, Inskeep WP, Ward DM, Carlson RP. 2009. In silico approaches to study mass and energy flows in microbial consortia: a syntrophic case study. BMC Syst Biol 3:114. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-3-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mahadevan R, Edwards JS, Doyle FJ. 2002. Dynamic flux balance analysis of diauxic growth in Escherichia coli. Biophys J 83:1331–1340. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)73903-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhuang K, Izallalen M, Mouser P, Richter H, Risso C, Mahadevan R, Lovley DR. 2011. Genome-scale dynamic modeling of the competition between Rhodoferax and Geobacter in anoxic subsurface environments. ISME J 5:305–316. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hanly TJ, Henson MA. 2011. Dynamic flux balance modeling of microbial co-cultures for efficient batch fermentation of glucose and xylose mixtures. Biotechnol Bioeng 108:376–385. doi: 10.1002/bit.22954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zomorrodi AR, Islam MM, Maranas CD. 2014. d-OptCom: Dynamic multi-level and multi-objective metabolic modeling of microbial communities. ACS Synth Biol 3:247–257. doi: 10.1021/sb4001307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Harcombe WR, Riehl WJ, Dukovski I, Granger BR, Betts A, Lang AH, Bonilla G, Kar A, Leiby N, Mehta P, Marx CJ, Segrè D. 2014. Metabolic resource allocation in individual microbes determines ecosystem interactions and spatial dynamics. Cell Rep 7:1104–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.03.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Smriga S, Fernandez VI, Mitchell JG, Stocker R. 2016. Chemotaxis toward phytoplankton drives organic matter partitioning among marine bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:1576–1581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1512307113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Azam F, Fenchel T, Field J, Gray J, Meyer-Reil L, Thingstad F. 1983. The ecological role of water-column microbes in the sea. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 10:257–263. doi: 10.3354/meps010257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Amin S, Parker MS, Armbrust EV. 2012. Interactions between diatoms and bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 76:667–684. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00007-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Stocker R, Seymour JR. 2012. Ecology and physics of bacterial chemotaxis in the ocean. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 76:792–812. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00029-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Klitgord N, Segrè D. 2010. Environments that induce synthetic microbial ecosystems. PLoS Comput Biol 6:e1001002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Moejes FW, Popa O, Succurro A, Maguire J, Ebenhoeh O. 2016. Dynamics of the bacterial community associated with Phaeodactylum tricornutum cultures. bioRxiv doi: 10.1101/077768. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Moejes FW, Moejes KB. 2017. Algae for Africa: microalgae as a source of food, feed and fuel in Kenya. African J Biotechnol 16:288–301. doi: 10.5897/AJB2016.15721. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Caron DA, Davis PG, Madin LP, Sieburth JM. 1986. Enrichment of microbial populations in macroaggregates (marine snow) from surface waters of the North Atlantic. J Mar Res 44:543–565. doi: 10.1357/002224086788403042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Varma A, Palsson BO. 1994. Stoichiometric flux balance models quantitatively predict growth and metabolic by-product secretion in wild-type Escherichia coli W3110. Appl Environ Microbiol 60:3724–3731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Perez-Garcia O, Lear G, Singhal N. 2016. Metabolic network modeling of microbial interactions in natural and engineered environmental systems. Front Microbiol 7:673. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Stocker R. 2012. Marine microbes see a sea of gradients. Science 338:628–633. doi: 10.1126/science.1208929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]