ABSTRACT

Genetic competence is a process in which cells are able to take up DNA from their environment, resulting in horizontal gene transfer, a major mechanism for generating diversity in bacteria. Many bacteria carry homologs of the central DNA uptake machinery that has been well characterized in Bacillus subtilis. It has been postulated that the B. subtilis competence helicase ComFA belongs to the DEAD box family of helicases/translocases. Here, we made a series of mutants to analyze conserved amino acid motifs in several regions of B. subtilis ComFA. First, we confirmed that ComFA activity requires amino acid residues conserved among the DEAD box helicases, and second, we show that a zinc finger-like motif consisting of four cysteines is required for efficient transformation. Each cysteine in the motif is important, and mutation of at least two of the cysteines dramatically reduces transformation efficiency. Further, combining multiple cysteine mutations with the helicase mutations shows an additive phenotype. Our results suggest that the helicase and metal binding functions are two distinct activities important for ComFA function during transformation.

IMPORTANCE ComFA is a highly conserved protein that has a role in DNA uptake during natural competence, a mechanism for horizontal gene transfer observed in many bacteria. Investigation of the details of the DNA uptake mechanism is important for understanding the ways in which bacteria gain new traits from their environment, such as drug resistance. To dissect the role of ComFA in the DNA uptake machinery, we introduced point mutations into several motifs in the protein sequence. We demonstrate that several amino acid motifs conserved among ComFA proteins are important for efficient transformation. This report is the first to demonstrate the functional requirement of an amino-terminal cysteine motif in ComFA.

KEYWORDS: ATPase, Bacillus subtilis, DEXD/DEXH box, genetic competence, helicase, natural transformation systems, transformation

INTRODUCTION

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) is a widespread phenomenon in bacteria and thought to be a major driver of biodiversity. HGT in bacteria is known to be the result of three major processes: conjugation, transformation, and bacteriophage transduction (1). All of these processes appear to be dependent on motors or motor-like proteins to function. Transformation is distinct from other HGT processes, as it is the only one that does not require an active donor. Genetic competence is a physiological state in which a naturally transformable cell takes up DNA from its environment. This process has been well studied in Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Helicobacter pylori (2, 3). The gene products involved in genetic competence are well conserved among these organisms, with the exception of H. pylori (4). Here, we used B. subtilis as a model system for genetic competence in bacteria.

The transforming DNA undergoes a three-step process during competence in B. subtilis. First, the DNA is bound to the outside of the cell. Next, it is fragmented and internalized. During internalization, one DNA strand is degraded to generate single-stranded DNA inside the cell (5). Lastly, the transforming DNA is integrated into the genome or other circularized DNA element in the cell via homologous recombination (6, 7). Internalization is mediated largely by two molecular machines, the possibly dynamic ComG protein pseudopilus and the molecular transport complex of the proteins ComEA, ComEC, and ComFA (reviewed in reference 6). Although comFA is not essential, it is required for efficient transformation (6).

DNA uptake in genetically competent cells appears to be a rapid and processive process, and ComFA is thought to be the major molecular motor central to this uptake process, requiring the power of ATP (8–10). ComFA shows homology to the members of the DEAD box family of helicases and translocases, which are generally low-processivity helicases that act predominantly on RNA substrates. The duplex unwinding activity of DEAD box proteins is often limited to tens of base pairs, with no additional translocase activity. This raises the question of the central role of ComFA in a highly processive process where hundreds or thousands of nucleotides are imported. To understand how the competence machinery functions, we must determine whether the unexpected behavior is the result of a unique feature intrinsic to ComFA. Here we conducted a mutational analysis of the canonical DEAD box helicase motifs, as well as another motif conserved among ComFA homologs but absent from DEAD box helicases. We confirm the classification of ComFA as a DEAD box helicase family member. We have also discovered a metal binding motif in the protein that might allow the helicase to coordinate activities with other components of the machinery to augment its activity.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

ComFA is a DEAD box helicase.

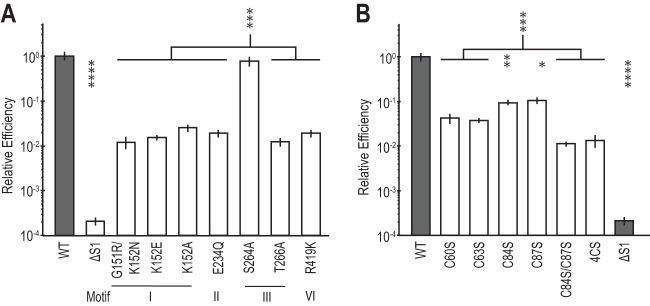

Bioinformatic analysis has identified ComFA as a member of the DEAD box helicase/translocase family (8, 10) through assignment of nine conserved amino acid motifs that together indicate DEAD box subfamily membership (11, 12). Previous functional studies have confirmed that ComFA is a P-loop-containing ATPase. Specifically, substitutions at residues (G151 and K152) in the ATP binding pocket of the P loop, designated motif I in the DEAD box motifs, disrupted ComFA activity (9). Here, we set out to determine whether the full complement of helicase motifs, highly conserved throughout ComFA proteins, is important to ComFA function, particularly those specific to the DEAD box family (Fig. 1; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). To do this, we measured the effects of mutations in four of the nine DEAD box motifs, I, II, III, and VI, on transformation efficiency. Motifs I and II, often known as Walker A and B motifs and associated with ATP binding and hydrolysis, respectively, are not specific to the DEAD box proteins but are expected to be central to protein function. Motifs III and VI are both associated with DEAD box proteins, and on the basis of homology to the helicase family, their mutation is expected to produce the most dramatic functional defects. We found that relative to the wild type (WT), predicted loss-of-function mutations in motif I, II, III, or VI led to 100-fold decreases in transformation efficiency (Fig. 2A). One exception was comFAS264A, a mutation in motif III that did not result in a transformation efficiency defect.

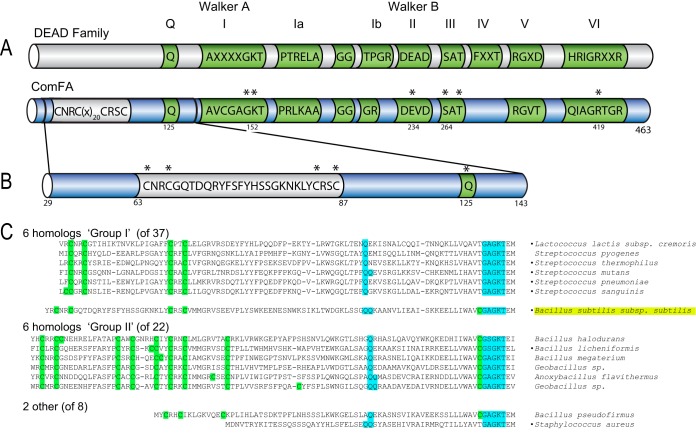

FIG 1.

Schematics of ComFA and relevant motifs. (A) DEAD box and ATPase motifs are green. Within ComFA, the zinc finger motif is silver. Asterisks denote residues subjected to mutational analysis. (B) Schematic of ComFA amino acid sequence ΔS1 region enlarged to show the primary sequence and the motifs comprising the region. (C) Alignment of N-terminal regions of 15 ComFA homologs divided into groups based on the numbers of cysteine residues in their zinc finger motifs, i.e., group I with four conserved cysteines and group II with nine conserved cysteines. B. subtilis falls between the groups with five cysteines, four in the zinc finger domain and one just before the Walker A-I motif. The cysteine residues are highlighted in green, and the Q and Walker A-I motifs are highlighted in blue. Strain names are on the right with bullets indicating the strains listed as naturally transformable in reference 24. Though naturally competent, S. aureus ComFA notably lacks this zinc finger motif. See Fig. S1 in the supplemental material for the sequence alignments of this region from 68 different ComFA proteins.

FIG 2.

The DEAD box and C4 motifs are required for efficient transformation and DNA uptake. (A) Transformation efficiency of strains carrying unmarked mutations of ComFA canonical DEAD box helicase motifs. All transformation efficiency values are normalized to the WT. The ΔS1 strain is included as a comFA mutant control (8, 9). (B) Transformation efficiency for unmarked mutations of the ComFA putative C4 zinc finger motif. All transformation efficiency values are normalized to the WT. WT and ΔS1 values are the same in panels A and B. The relative efficiency axis is on a log10 scale. Error bars show standard errors. WT, n = 35; all mutants, n = 5. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

The ΔS1 in-frame deletion is very disruptive to ComFA activity.

While conducting experiments to determine whether ComFA is a DEAD box family member, we noticed that none of the DEAD box motif point mutations caused transformation defects as severe as the comFAΔS1 in-frame deletion (Fig. 2A). The ΔS1 in-frame deletion was originally designed as a comFA mutant allele that lacked polar effects on the downstream comFB and comFC genes (8). To explore possible causes for the severe comFAΔS1 transformation defect, we reexamined the ComFA protein sequence. We found that the in-frame deletion encompasses two possible motifs and resolves just upstream of motif I, likely disrupting the helicase fold (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, we noted that the ΔS1 in-frame deletion also removes a possible C4 zinc finger motif (Fig. 1B). The removal of this motif could contribute to the severity of the phenotype caused by comFAΔS1. Therefore, we determined the effect of mutations in this motif on transformation efficiency.

The possible C4 zinc finger region is required for ComFA function and binds zinc.

Mutation of each individual cysteine in the putative C4 zinc finger motif to a serine produced a marginal, 10-fold defect in transformation efficiency. The conversion of at least two cysteines to serines produced a transformation efficiency defect similar to that observed with the canonical DEAD box motif mutants (Fig. 2B versus A). The severity of the double and quadruple cysteine-to-serine mutants (here nicknamed the 4CS mutant allele, comFA4CS) suggests that the motif plays a role in transformation.

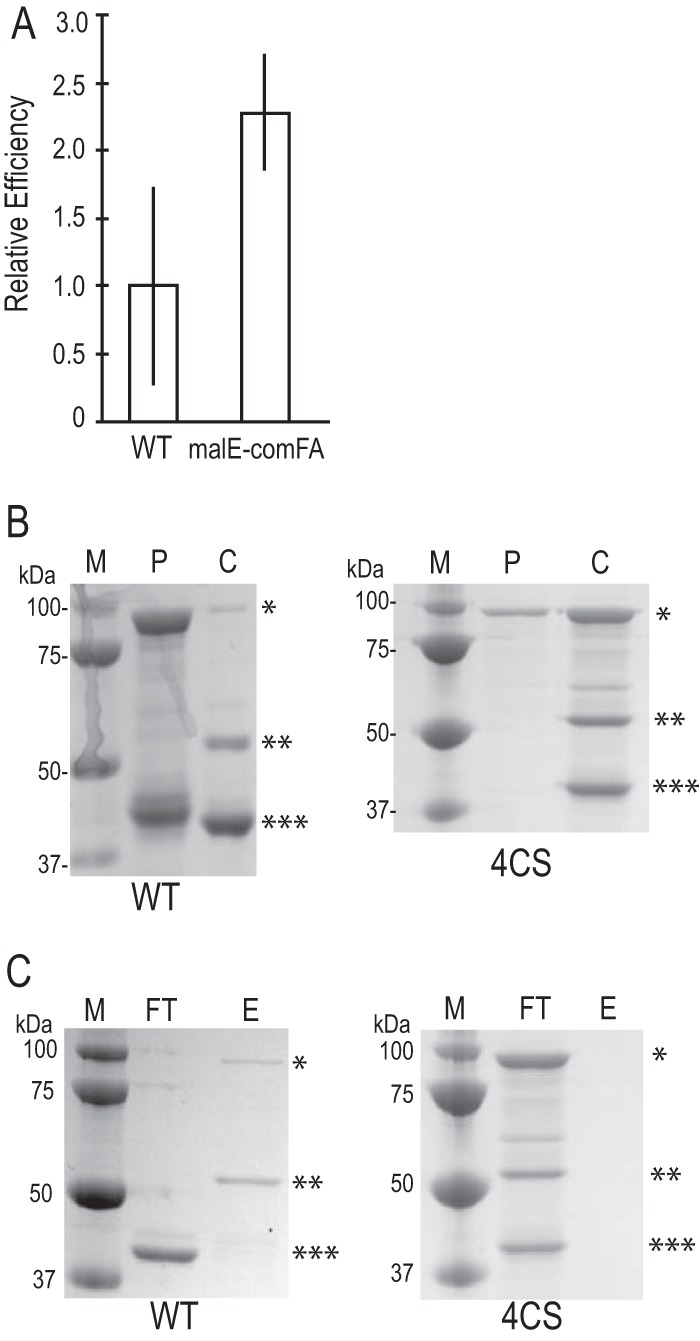

Since the highly conserved cysteines comprise a motif reminiscent of a C4 zinc finger, we tested whether the cysteines could be involved in zinc binding. To do so, we made WT and 4CS mutant malE-comFA fusion constructs for heterologous expression of maltose binding protein (MBP)-ComFA translational fusions in Escherichia coli. Transformation efficiency experiments showed that malE-comFA complements a comF::cat mutation comparably to untagged comFA in B. subtilis (Fig. 3A). We purified the MBP-ComFA and MBP-ComFA4CS fusions expressed in E. coli and cleaved them with human rhinovirus 3C protease to separate the ComFA and MBP components of the fusions (Fig. 3B). The cleaved protein mixtures were tested for zinc binding by immobilized metal affinity chromatography with immobilized Zn2+. We found that while ComFA and MBP-ComFA were immobilized on the column and eluted with the addition of imidazole, MBP and the components the MBP-ComFA4CS fusion cleavage reaction did not interact with the immobilized metal (Fig. 3C). Thus, the four cysteine-to-serine conversions together disrupt the metal binding activity of the 4CS mutant.

FIG 3.

The cysteines in the C4 motif are required for metal binding. (A) Transformation efficiency of a malE-comFA fusion relative to that of WT comFA. Both constructs were expressed from the yvbJ ectopic locus under the control of the PcomF promoter. The comF locus has been replaced with a cat cassette. Error bars show standard errors. WT, n = 2; malE-comFA mutant, n = 4. (B) SDS-PAGE of 3C protease cleavage of translational fusion constructs. Lanes M, molecular mass markers; lanes P, precleavage elution from Sepharose-dextrin column; lanes C, cleaved after a 2-h incubation with 1:100 (wt/wt) 3C protease. (C) SDS-PAGE of fractions from zinc-IMAC analysis. Lanes FT, flowthrough from the column; lanes E, eluate from the column following addition of 250 mM imidazole-HCl. Asterisks in panels B and C: *, MBP-ComFA; **, ComFA; ***, MBP.

The 4CS motif contributes to ComFA function independently of DEAD box motifs.

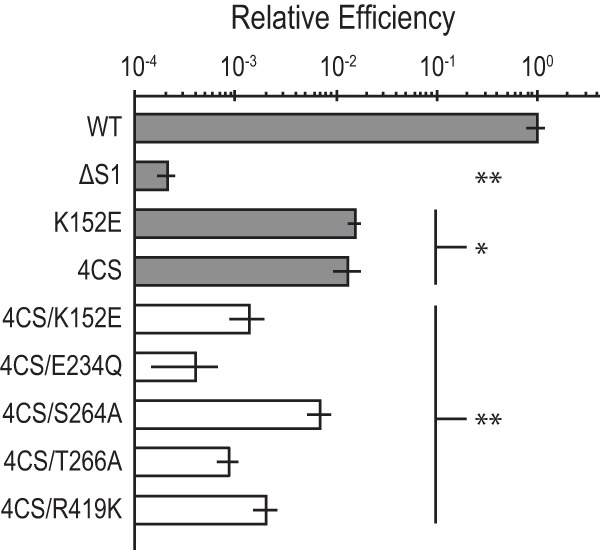

Finally, we sought to determine whether the contribution of the C4 motif to transformation efficiency is distinct from the contribution we observed from the canonical DEAD box helicase motifs. We asked whether the effect of mutation of both a helicase motif and the C4 motif is more severe than the individual mutations. To this end, we introduced each of the canonical DEAD box motif mutations into the comFA4CS background. The double motif mutants displayed an approximately 1,000-fold defect in transformation efficiency, which is greater than the defects observed in the DEAD box and C4 motif mutations alone (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

The C4 motif requirement is independent of the DEAD box motif requirement. Transformation efficiency for mutations of ComFA putative C4 zinc finger motif combined with canonical DEAD box helicase motifs. All transformation efficiency values are normalized to the WT. WT, K152E, and ΔS1 values are those reported in Fig. 2A, and the 4CS value is that reported in Fig. 2B. The relative efficiency axis is on a log10 scale. Error bars show standard errors. WT, n = 35; all mutants, n = 5. *, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.0001.

The 4CS mutation appears to destabilize the ComFA protein.

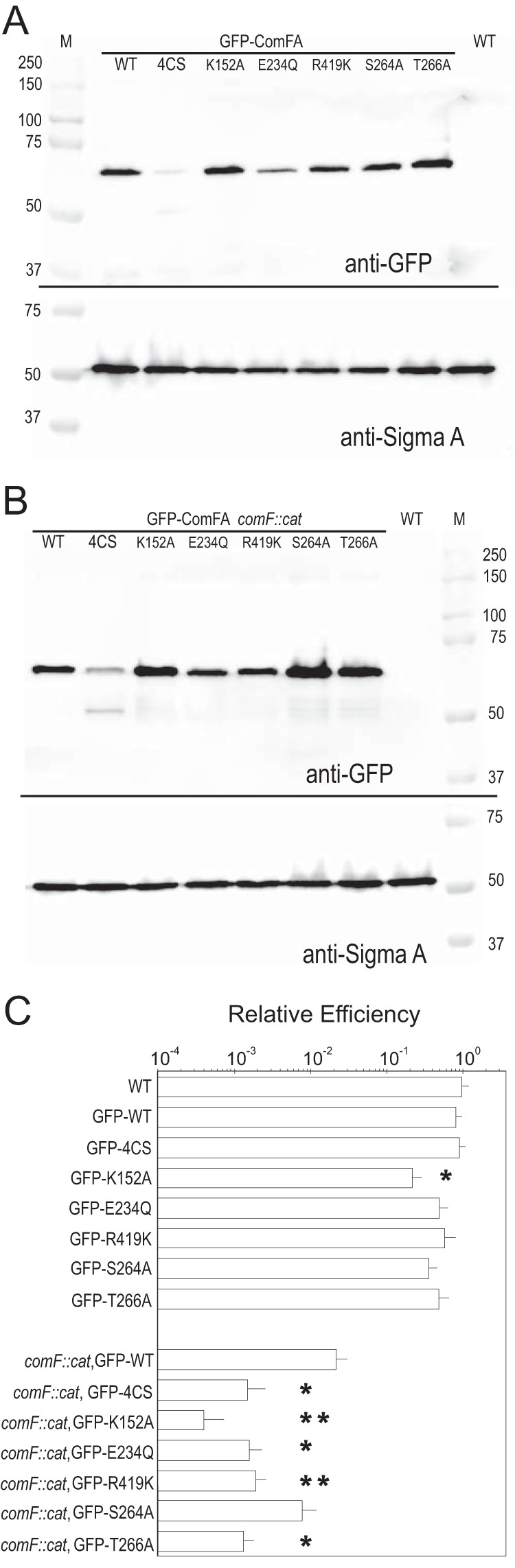

We created a WT and six mutant green fluorescent protein (GFP)-ComFA fusions to control for whether either the 4CS or any DEAD box mutation would affect the stability of ComFA. GFP-ComFA, GFP-ComFA4CS, and five of the DEAD box mutations used in Fig. 2 were compared for transformation efficiency and immunoblotted with anti-GFP antiserum (Fig. 5) to determine whether these mutant strains express the same amount of protein as the WT. We tested the effects both in the presence and in the absence of the endogenous comF operon; the operon contains three open reading frames, comFA, comFB, and comFC. We found that all five DEAD box mutant forms were present at levels similar to those of WT GFP-ComFA, but GFP-ComFA4CS was present at notably lower levels than the WT, and an immunoreactive breakdown product was observed. As GFP is famously stable, this breakdown product most likely corresponds to GFP fused to degraded ComFA. The relative transformation efficiencies of the mutant versus WT GFP fusion proteins are comparable to results shown in Fig. 2 and 4. The strain producing GFP-ComFA in the context of whole operon deletion, comF::cat, has a lower transformation efficiency than in the context of the WT operon, comF+. This difference is due to the contribution of ComFB and ComFC to transformation efficiency, consistent with our previously published data (13). Therefore, the metal binding domain may have a role in the stabilization of the ComFA protein in the complex involved in DNA transport.

FIG 5.

Stability and transformation efficiency of WT and mutant GFP-ComFA proteins. (A, B) Immunoblot assay showing WT, 4CS, K152A, E234Q, R419K, S264A, and T266A GFP-ComFA fusions in the presence (A) or absence (B) of the endogenous comF operon. Note that GFP-ComFA4CS is less stable, showing less signal, as well as a 50-kDa immunoreactive degradation product, but all of the other mutants are stable. SigmaA was used as a loading control. M, molecular mass markers in kilodaltons. (C) Relative transformation efficiencies of the GFP-ComFA fusions in the presence or absence of the comF operon. The absolute efficiency of the GFP-WT ComFA fusion ectopically expressed at yvbJ (comF::cat [SC054]) is the same as that of WT ComFA (comF::cat [SC140]) also expressed at yvbJ (shown in Fig. 3A). The relative efficiency axis is on a log10 scale. Error bars show standard errors. WT, n = 14; GFP-ComFA, n = 10; comF::cat GFP-ComFA, n = 7; GFP-ComFA4CS, n = 6; all other mutant GFP fusions, n = 3 or 4. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (log-transformed data).

The GFP-ComFAK152A protein showed the lowest transformation efficiency in the comF::cat background and, when expressed in the presence of the endogenous comF operon, showed a dominant negative effect (Fig. 5C) on transformation efficiency. The GFP-ComFAK152A mutant protein, presumably unable to bind ATP, was produced, as confirmed by immunoblot analysis, but the transformation efficiency was >10-fold less than that of the WT or the GFP-ComFA4CS construct. Dominant negative mutations often arise when inactive subunits are incorporated into an oligomeric protein complex. Therefore, we propose the following model. The C4 motif is required for metal binding and perhaps for incorporation of the ComFA protein in the complex. Once there, the complex requires a functioning P loop for ATP binding. We hypothesize that the additive effect of these two mutations (Fig. 4) can be explained by the additive action of these two regions of the protein. ComFA4CS alone has a higher transformation efficiency than ComFAK152A because it has a functioning K152, so when ComFA4CS occasionally (but unstably) binds in the protein complex, ATP binding/hydrolysis can occur, but the combined allele ComFA4CS/K152E is more severe (Fig. 4) because the protein is either not in the complex or is nonfunctional when it is there.

Conclusions.

The experiments presented here experimentally support the designation of ComFA as a DEAD box DNA helicase/translocase and identify an additional four-cysteine motif potentially involved in metal binding and required for ComFA function. Prior work on ComFA only experimentally tested the contribution of motif I (9, 10). Londoño-Vallejo et al. chose the comFAΔS1 mutation because of the level of the defect it created in the ComFA protein while allowing expression of the two downstream components of the operon (8). The comFAΔS1 defect compared with comFA4CS/E234Q, which contains a mutation in motif II, suggests that the ΔS1 transformation efficiency defect is the result of removal of the putative metal binding activity and disruption of the P-loop ATPase fold in ComFA (Fig. 1A and 4). The defect in the motif I mutants may not be as severe, since motif I point mutants do retain some nucleotide binding activity and therefore likely still hydrolyze ATP (14). Disruption of the ATPase fold in the ΔS1 protein would reflect complete loss of ATP binding, which would phenocopy a hydrolysis-dead (motif II) mutation.

The region removed by the ΔS1 in-frame deletion contained two parts, the putative zinc finger and part of DEAD box helicase motif I. One interesting feature of comFAΔS1 was the greatly reduced transformation efficiency observed in the deletion, relative to any of the individual mutations. Londoño-Vallejo et al. found the transformation efficiency defects of the motif I point mutations and the ΔS1 mutation to be equivalent (9). The difference in relative efficiency may be the result of differences in how the experiments were conducted, as each of our strains contains a single allele of comFA and our comparable ATP binding site mutations result in less severe phenotypes than the experiments performed in reference 9.

The evidence that the four-cysteine motif is required to allow proper ComFA function is consistent with work that has shown that zinc homeostasis is important for the transformation of B. subtilis (15). It is still unclear how the newly demonstrated C4 motif contributes to efficient transformation. A simple explanation is that the C4 motif forms a metal binding domain. Metal binding domains such as zinc fingers are often involved in protein-DNA interactions and protein-protein interactions (16). The canonical nucleic acid binding surfaces of DEAD box helicases and the relative promiscuity of the DNA uptake apparatus in B. subtilis with respect to the source of the donor DNA argue against the idea that metal binding makes a significant DNA binding contribution (17). Our GFP immunoblot assays suggest one possibility, i.e., that the C4 motif is involved in some sort of protein-DNA or protein-protein interaction without which ComFA becomes somewhat destabilized.

The additional understanding of the metal binding activities of the competence protein ComFA sheds some light on how the competence machinery is unique in B. subtilis, as the metal binding motif is not observed in other DEAD box helicases as part of the same domain as the motor. The requirement for metals, potentially specifically zinc, may also explain the importance of zinc importers in B. subtilis and their modulated activity during the development of competence (15).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction for B. subtilis mutant and expression constructs.

All of the strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in Tables S1 and S2 in the supplemental material. The constructs used to make unmarked mutations in the comFA coding sequence were PCR amplified and subcloned into pMiniMAD2 (18). Point mutations in the constructs were introduced by site-directed mutagenesis and verified by sequencing. Table S3 lists the oligonucleotides used for PCR and mutagenesis. All plasmids were propagated in E. coli DH5α, which was grown and transformed as described previously (19).

Construction of plasmids for integration at yvbJ.

PcomF-comFA-, PcomF-malE-comFA-, and PcomF-GFP-comFA-containing plasmids were constructed to express ComFA or the MBP-ComFA and GFP-ComFA fusion proteins at yvbJ as described in the supplemental material. PcomF-comFA, PcomF-malE-comFA, and PcomF-GFP-comFA constructs were transferred from pSC048, pSC262, and pSC114, respectively, into to pBB268 by digestion with EcoRI and BamHI to generate pSC036, pSC266, and pSC127, respectively. Mutant GFP fusion constructs pTF010 (for comFA4CS), pTF011 (for comFAK152A), and pTF016-pTF019 (for comFAE234Q, comFAR419K, comFAS264A, and comFAT266A) were derived from pSC114 or pSC127 and constructed as described in the supplemental material.

Construction of comF deletion plasmid.

Primers oSC032 and oSC033 were used to amplify a region upstream of comFA from B. subtilis PY79 genomic DNA. Primers oSC193 and oSC194 were used to amplify a region downstream of comFC from B. subtilis PY79 genomic DNA. The upstream fragments were inserted into pBB028 in separate steps following digestion with EagI and SalI and with SphI and XbaI, respectively, to create pSC104.

B. subtilis strain construction.

All of the B. subtilis strains used in this study were derived from laboratory prototrophic strain PY79 (20). Transformation of B. subtilis was performed with relevant plasmid constructs, linearization with ScaI, and selection on LB plates supplemented with 1 μg/ml erythromycin plus 25 μg/ml lincomycin (MLS).

comF expression strains.

Unmarked mutations were introduced into the genome as described in reference 18, with the following modifications. The transduction step was omitted. Transformed colonies carrying pMiniMAD2 constructs were restreaked onto MLS resistance selective plates and grown at 37°C overnight. One colony from five to eight of the restreaked isolates was used to inoculate a 5-ml LB culture and grown while rolling at 37°C for 6 to 8 h. Cells were diluted 1:1,000 in 25 ml of LB, grown at the permissive temperature for 24 h, diluted again, and grown at the permissive temperature for an additional 24 h. Mutations were verified by sequencing of PCR products produced from genomic DNA preparations or colony PCR with primers oSC085 and oSC086. Sequencing was performed with oSC311, oSC312, oSC313, and/or oSC314, depending on the location of the mutation.

Construction of yvbJ ectopic haploid strains.

Merodiploid strains for ectopic expression of ComFA or WT and mutant fusion proteins were made with the plasmids constructed for integration at yvbJ. Strains SC032, SC234, SC050, TF039, TF040, TF053, TF054, TF055, and TF056 were constructed in a comF+ background. SC049, a comF::cat mutant strain, was generated with comF deletion plasmid pSC104. Genomic DNA from SC049 was used to remove the endogenous comF locus from SC032, SC234, SC050, TF039, TF040, and TF053 to TF056 to generate SC140, SC238, SC054, TF042, TF043, and TF057 to TF060, respectively.

Transformation efficiency.

Both one- and two-step transformation protocols were used to measure transformation efficiency. The two-step protocol is as follows. A fresh colony was picked from an LB plate grown overnight at 37°C and used to inoculate a 5- to 6-ml LB culture grown in a roller drum at 24°C for 12 to 16 h or a 1-ml LB culture grown at 37°C for 1.5 to 2 h. Cells from cultures with a final optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.2 to 1.2 were harvested by pelleting at 6,010 × g, washed three times with 1 ml of 1× PBS, and resuspended in 500 μl of 1× modified competence medium (MC) (25), and the OD600 was measured. The washed cells were used to inoculate a 1-ml 1× MC culture to a starting OD600 of 0.01 to 0.05. Cells were grown while rolling at 37°C for 5 h. At 5 h postinoculation, 400 to 900 μl of the culture was transferred to 13-mm glass tubes, 0.4 to 0.9 μg of gSC018 genomic DNA was added for a final DNA concentration of 1 μg/ml of culture, and the MgSO4 concentration was increased to 8 mM. Cells were grown while rolling at 37°C for an additional 2 h. For CFU counting, 100 μl of a 10−6 dilution in 1× PBS was plated in duplicate on nonselective medium. Dilutions to allow for 50 to 1,000 CFU per plate, when possible, were plated on selective plates containing 100 μg/ml spectinomycin. Plates were incubated at 37°C overnight, and colonies were counted the following day. Transformation efficiency was calculated with the formula ηS = Cr/(CTρD), where Cr is the average number of resistant CFU (transformants), CT is the average total number of CFU, and ρD is the DNA concentration in micrograms per milliliter. Each round was normalized to WT PY79 run at the same time. The limit of detection of the assay is 0.5 transformant/CFU/μg of genomic DNA.

The one-step transformation method differed from the two-step method only in that fresh colonies were inoculated directly into 1 ml of 1× MC and 40 or 400 ng of DNA was typically added to 400 μl of cells transferred into 13-mm glass tubes after growth in MC for 4 to 5 h. From the two-step transformations, samples from the remaining 600 μl of the starter culture were taken at time of plating (6 to 7 h of growth in 1× MC) for subsequent immunoblot analysis.

malE-comFA and GFP-comFA complementation test.

Complementation tests were run as for the other transformation efficiency experiments, except that SC140 (yvbJ::PcomF-comFA ermr comF::cat) was used as the control strain for the test.

Statistical analysis.

Relative efficiency values were converted to arcsine values with the following equation to allow for normally distributed input for Dunnett's multiple-comparison test (for comparison of all mutants together with the control): DS = [180 sin−1(ηS/6)]/π.

Dunnett's multiple-comparison test was performed on converted data with the multcomp package in the R statistical analysis software. Relative transformation efficiencies of WT and mutant GFP-ComFA fusions were log transformed to generate normally distributed data, and t tests comparing each mutant pairwise with corresponding controls were used to test for significant differences.

Plasmid construction for expression in E. coli.

The comFA coding sequence was subcloned into the pMAL-c5E expression vector (New England Biolabs) (see the supplemental material for full details). All constructs contained a C-to-A mutation at the first position in the comFA coding sequence to create an NdeI site for subcloning and to maintain the methionine in the sequence when inserted into the amino-terminal translational fusion with malE. A BamHI site was added following the stop codon in the sequence with PCR primer oSC061. All plasmids were propagated in E. coli DH5α.

Protein expression and purification. (i) MBP-ComFA expression.

MBP-ComFA and MBP-ComFA4CS expression vectors (pSC042 and pSC287) were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) cells. LB broth was supplemented with ampicillin, 10% glycerol, and 200 μM ZnSO4; bacteria were grown to an OD600 of 0.2 to 0.4 at 37°C; the temperature was dropped to 16°C; and growth continued until the OD600 reached 0.4. Cultures were then induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 16°C for 16 h. Cells were harvested by pelleting at 5,000 × g for 10 min and resuspended in 20 ml of buffer M1 (50 mM HEPES [pH 8], 200 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol) plus 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Cell suspensions were dipped in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until used for purification.

(ii) MBP-ComFA purification and 3C proteolysis.

Frozen cells were thawed, diluted 1:5 in cold buffer M1, and then lysed by passage through the One Shot Cell Disruptor (Constant Systems) at 20,000 lb/in2. The lysate was clarified at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C and then passed over Sepharose-dextrin resin (GE Lifesciences) equilibrated with buffer M1. After being washed with the same buffer, protein was eluted with buffer M1 plus 10 mM d-(+)-maltose. Elutions were pooled, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. The protein content of the eluate was estimated by A280 measurement and calculated by using the predicted MBP-ComFA extinction coefficient and molecular mass (128,230 M−1 cm−1 and 94.34 kDa). Purified glutathion S-transferase (GST)–protease (21) was added from a 3-mg/ml concentrated stock at 1:100 (wt/wt) to purified fusion proteins, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 2 h.

Zinc-IMAC analysis.

Following proteolysis, the sample was loaded onto an IMAC FF column (GE Life Sciences) charged with ZnSO4 and equilibrated with buffer M1. Chromatography was performed as described in reference 22. After being washed with buffer, the protein was eluted with buffer M1 plus 10 mM d-(+)-maltose and 250 mM imidazole.

Immunoblot analysis.

Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (8% total acrylamide) and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Membranes were probed with anti-GFP and anti-SigmaA polyclonal antibodies (23) diluted 1:10,000 in 2% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline–0.05% Tween 20, followed by a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Amersham) secondary antibody. Clarity ECL substrate (Bio-Rad) was used to detect the chemiluminescent signal on a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc Touch Imaging System.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of the Burton and Losick labs for assistance with materials and useful discussions. The constructs and E. coli strains used in this study and the procedure used to purify the GST-3C protease were a generous gift from Rachelle Gaudet. Thanks also go to Cécile Ané for consultation on statistical methods.

This work was funded by a grant from the Rita Allen Foundation to Briana M. Burton. Scott S. Chilton was supported by a Harvard University Graduate Science Fellowship and a Howard Hughes Gilliam Fellowship for Advanced Study.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00272-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ochman H, Lawrence JG, Groisman EA. 2000. Lateral gene transfer and the nature of bacterial innovation. Nature 405:299–304. doi: 10.1038/35012500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergé M, Moscoso M, Prudhomme M, Martin B, Claverys JP. 2002. Uptake of transforming DNA in Gram-positive bacteria: a view from Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol 45:411–421. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen I, Christie PJ, Dubnau D. 2005. The ins and outs of DNA transfer in bacteria. Science 310:1456–1460. doi: 10.1126/science.1114021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stingl K, Muller S, Scheidgen-Kleyboldt G, Clausen M, Maier B. 2010. Composite system mediates two-step DNA uptake into Helicobacter pylori. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:1184–1189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909955107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piechowska M, Fox MS. 1971. Fate of transforming deoxyribonucleate in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 108:680–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen I, Dubnau D. 2004. DNA uptake during bacterial transformation. Nat Rev Microbiol 2:241–249. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dubnau D, Provvedi R. 2000. Internalizing DNA. Res Microbiol 151:475–480. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(00)00166-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Londoño-Vallejo JA, Dubnau D. 1993. comF, a Bacillus subtilis late competence locus, encodes a protein similar to ATP-dependent RNA/DNA helicases. Mol Microbiol 9:119–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Londoño-Vallejo JA, Dubnau D. 1994. Mutation of the putative nucleotide binding site of the Bacillus subtilis membrane protein ComFA abolishes the uptake of DNA during transformation. J Bacteriol 176:4642–4645. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.15.4642-4645.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeno M, Taguchi H, Akamatsu T. 2011. Role of ComFA in controlling the DNA uptake rate during transformation of competent Bacillus subtilis. J Biosci Bioeng 111:618–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Linder P. 2006. Dead-box proteins: a family affair—active and passive players in RNP-remodeling. Nucleic Acids Res 34:4168–4180. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linder P, Jankowsky E. 2011. From unwinding to clamping—the DEAD box RNA helicase family. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 12:505–516. doi: 10.1038/nrm3154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sysoeva TA, Bane LB, Xiao DY, Bose B, Chilton SS, Gaudet R, Burton BM. 2015. Structural characterization of the late competence protein ComFB from Bacillus subtilis. Biosci Rep 35:e00183. doi: 10.1042/BSR20140174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matte A, Delbaere LT. 2010. ATP-binding motifs. In Encyclopedia of life sciences. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., London, United Kingdom: http://www.els.net/WileyCDA/ElsArticle/refId-a0003050.html. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogura M. 2011. ZnuABC and ZosA zinc transporters are differently involved in competence development in Bacillus subtilis. J Biochem 150:615–625. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvr098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Auld DS. 2001. Zinc coordination sphere in biochemical zinc sites. Biometals 14:271–313. doi: 10.1023/A:1012976615056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kidane D, Carrasco B, Manfredi C, Rothmaier K, Ayora S, Tadesse S, Alonso JC, Graumann PL. 2009. Evidence for different pathways during horizontal gene transfer in competent Bacillus subtilis cells. PLoS Genet 5:e1000630. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patrick JE, Kearns DB. 2008. MinJ (YvjD) is a topological determinant of cell division in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 70:1166–1179. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Youngman PJ, Perkins JB, Losick R. 1983. Genetic transposition and insertional mutagenesis in Bacillus subtilis with Streptococcus faecalis transposon Tn917. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 80:2305–2309. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.8.2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walker PA, Leong LE, Ng PW, Tan SH, Waller S, Murphy D, Porter AG. 1994. Efficient and rapid affinity purification of proteins using recombinant fusion proteases. Biotechnology (NY) 12:601–605. doi: 10.1038/nbt0694-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voráčková I, Suchanova S, Ulbrich P, Diehl WE, Ruml T. 2011. Purification of proteins containing zinc finger domains using immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography. Protein Expr Purif 79:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2011.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huppert LA, Ramsdell TL, Chase MR, Sarracino DA, Fortune SM, Burton BM. 2014. The ESX system in Bacillus subtilis mediates protein secretion. PLoS One 9:e96267. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnston C, Martin B, Fichant G, Polard P, Claverys JP. 2014. Bacterial transformation: distribution, shared mechanisms and divergent control. Nat Rev Microbiol 12:181–196. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Konkol MA, Blair KM, Kearns DB. 2013. Plasmid-encoded ComI inhibits competence in the ancestral 3610 strain of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 195:4085–4093. doi: 10.1128/JB.00696-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.