Abstract

Background

Primiparous women are at-risk for early, unintended breastfeeding reduction and cessation. Breastfeeding patterns that contribute to these outcomes require further exploration.

Research Aim/Questions

To describe early, “real time” breastfeeding behaviors and perceived problems of primiparous women.

Methods

First-time mothers intending to exclusively breastfeed downloaded a commercial infant feeding app during their postpartum hospitalization. Women logged feedings and their breastfeeding experiences, as they occurred, through eight weeks postpartum. Additional feeding and background data were collected via EMR and questionnaires administered at enrollment, two, and eight weeks postpartum. Summary statistics were compiled to examine weekly breastfeeding behaviors and problems.

Results

In this sample of 61 primarily highly-educated, White women committed to breastfeeding, 38% (n=23) used formula during the postpartum hospitalization and 68% (n=34) used formula at least once by two weeks. Nine women stopped breastfeeding during the study. Women using any formula in the hospital and those with less positive baseline attitudes toward breastfeeding were less likely to be exclusively breastfeeding at two and eight weeks, respectively (p<0.05). There was a trend toward declining at-breast feeds and high rates of milk expression during the study. Breastfeeding problems peaked at Week 2, with 81% of women (n=39) endorsing at least one problem at that time. The most prevalent problems included perception of inadequate milk, pain, latching, and inefficient feeds.

Conclusions

Interventions to address suboptimal breastfeeding in primiparous women should consider the pervasiveness of early milk expression and in-hospital formula supplementation in this population, as well as the trajectory of common problems.

INTRODUCTION

According to the U.S. National Immunization Survey for 2013 births, 81% of infants are breastfed at birth, but there is a precipitous drop in both breastfeeding exclusivity and continuation in the first few weeks. By two weeks, only 60% of mothers are breastfeeding exclusively, and this drops to 50% by eight weeks with 72% still breastfeeding at all (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016). Over half of women who intend to exclusively breastfeed report not meeting their breastfeeding goals (Perrine, Scanlon, Li, Odom, & Grummer-Strawn, 2012).

Primiparous women are particularly vulnerable to early, unintended formula supplementation and breastfeeding cessation; the majority experience one or more breastfeeding problems associated with breastfeeding discontinuation before two months (Wagner, Chantry, Dewey, & Nommsen-Rivers, 2013). A small body of research characterizes factors, though not unique to first-time mothers, may be pronounced in this group and contribute to breastfeeding difficulties, including low breastfeeding self-efficacy, high rates of in-hospital formula use (Chantry, Dewey, Peerson, Wagner, & Nommsen-Rivers, 2014), and the cognitive dissonance between prenatal breastfeeding expectations and postnatal reality (Williamson, Leeming, Lyttle, & Johnson, 2012).

To address suboptimal breastfeeding outcomes among primiparous women, a nuanced understanding of their breastfeeding behaviors and problems is needed. Presently, our understanding is based largely upon retrospective self-report data, which is subject to social desirability and recall bias. Current breastfeeding status, interim events, mood, fatigue, and societal expectations can compromise accuracy and details of memory and reporting (Barbosa, Oliveira, Zandonade, & Neto, 2012; Burnham et al., 2014). Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) offers a methodological solution to this issue by sampling subject experiences—thoughts, behaviors, symptoms—concurrently with, or close to, their actual occurrence (Runyan & Steinke, 2015; Shiffman, Stone, & Hufford, 2008). In the current study, we describe breastfeeding behaviors of first-time mothers using EMA via a mobile infant feeding application (i.e., “app”).

METHODS

This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. Methods and reliability data were previously published (Demirci & Bogen, 2016).

Design

We conducted a prospective, observational study tracking breastfeeding behaviors and thoughts of primiparous women through eight weeks postpartum via a commercial infant feeding tracking app. The ultimate goal of the study was to inform timing and content of another technology-based intervention to deliver targeted breastfeeding support. Women were compensated up to $105 for study participation and the cost of the app.

Setting

Between October 2014 and August 2015, we approached, screened, and enrolled women during their postpartum hospitalization at a regional obstetrical hospital in the northeastern United States.

Sample

We aimed to enroll a convenience sample of 50–60 participants to inform breastfeeding support content for a subsequent study; no formal power calculation was performed. Women were eligible if they were at least 18 years, English-speaking, had no other children, delivered a healthy, singleton infant, owned a smartphone, intended to breastfeed exclusively ≥2 months, and had no conditions expected to adversely impact breastfeeding or milk supply. The decision to include only primiparous women, rather than all women without prior breastfeeding experience (and thus women at potentially similar risk for breastfeeding problems), was based upon recruitment logistics and difficulty in parsing what constituted “any breastfeeding experience” (e.g., one breastfeeding attempt, any milk expression, etc.). All participants provided written informed consent.

Data Collection via the App

At enrollment, we assisted women in downloading and initial use of the app (BabyConnect) on their smartphone or mobile device. We instructed participants to begin entering feeding and milk expression data into the app, as close as possible to the time it occurred (e.g., time, duration, volume, comments/notes). We also encouraged participants to free-text their breastfeeding thoughts and experiences (e.g., problems, successes, unexpected events) daily or at least once per week using the app diary. Women sent us their app data daily or weekly through eight weeks via an email summary feature (HTML format).

Data Collection at Enrollment

At enrollment, we administered an investigator-created questionnaire assessing demographics, medical and perinatal history, breastfeeding intentions/plans, breastfeeding education, and current breastfeeding concerns. We abstracted pregnancy, delivery, and infant feeding data from the hospital electronic medical record (EMR). We also assessed breastfeeding attitude, stress, and anxiety as covariates impacting breastfeeding outcomes.

Telephone Interviews at Two and Eight Weeks

We called all women at two and eight weeks postpartum to administer a feeding questionnaire and again assess stress and anxiety. If participants stopped breastfeeding, we assessed applicable items at the point of notification. Feeding questionnaires assessed current breastfeeding status and problems. The two-week questionnaire also assessed more detailed breastfeeding information and events (e.g., onset of copious milk production in lactogenesis stage II, use of assistive feeding devices, reason(s) for milk expression, etc.).

Measurement

Breastfeeding attitude was assessed via the Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale (IIFAS), a widely used and validated 17-item instrument with scores ranging from 17 to 85, where a higher score indicates a more favorable attitude toward breastfeeding (Chen et al., 2013; de la Mora, Russell, Dungy, Losch, & Dusdieker, 1999). Stress and anxiety were assessed via the combined PROMIS Emotional Distress-Anxiety Scale Short Form (4-item) and the Perceived Stress Scale 4-item (Combined EDA/PSS) (NIH PROMIS Assessment Center, 2012; Warttig, Forshaw, South, & White, 2013). Possible scores for the Combined EDA/PSS range from 0–32, a higher score indicating greater stress and anxiety.

At enrollment, breastfeeding concerns were assessed via an investigator-created 16-item checklist, gleaned from the literature, which also included an “other” write-in option. Women were queried on breastfeeding problems at both two and eight weeks using an open-ended question (“What breastfeeding problems are you currently experiencing?”). The two-week response was immediately categorized utilizing the same problem/concern checklist as at enrollment. Problems at eight weeks were recorded as close to participants’ actual words as possible and later coded.

We entered and managed all data in REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Pittsburgh (Vanderbilt University, 2017).

Analysis

We used SPSS v. 24 (IBM Corporation, 2016) to conduct all statistical analyses. We calculated summary statistics for hospital feeding EMR data, as well as background demographic, health, and breastfeeding intention data.

Data abstracted from the app summaries sent by participants included daily number of at-breast feeds, formula feeds, and milk expressions; daily volumes of formula and milk expressed and/or provided to infant; current breastfeeding problems and reasons for formula use. Only complete daily feeding data was abstracted and included in analyses, which was operationalized by researcher consensus to include at least six documented feedings in a 24-hour period and gaps of no greater than five hours between feeding sessions during daytime hours. At-breast feeding sessions documented less than five minutes apart were counted as a single session. We condensed daily summaries into weekly summaries for each participant by averaging feeding data across the number of days of complete data. Due to wide inconsistencies in participant documentation, we were unable to reliably capture volume of formula or expressed milk feeds.

We analyzed the association between the sample characteristics listed in Table 1 (as well as early milk expression at one and two weeks) with provision of any human milk, exclusive human milk, and any formula at both two and eight weeks. We used binary logistic regression with unadjusted odds ratios to determine the relationship between categorical characteristics and breastfeeding outcomes (inclusion limited to categorical variables with least five cases per discrete category). For continuous-level variables, we used independent sample t-tests to assess the relationship with breastfeeding outcomes.

Table 1.

Categorical-level sample characteristics and relationship with exclusive and any breast milk at two and eight weeks postpartum (n and proportions).

| Characteristic | Baseline | 2 Week Total | Breastfeeding Status at 2 weeks | 8 Week Total | Breastfeeding Status at 8 weeks | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exclusive HM | Any HM | Exclusive HM | Any HM | ||||

| Totals | 61 (100) | 47 (100) | 26 (54) | 44 (94) | 41 (100) | 21 (51) | 33 (81) |

| Married | 41 (67) | 35 (75) | 21 (81) | 33 (75) | 31 (76) | 18 (86) | 27 (82) |

| Education | |||||||

| High school diploma | 10 (16) | 5 (11) | 2 (8) | 5 (11) | 5 (12) | 2 (10) | 4 (12) |

| Some college or vocational program | 14 (23) | 10 (21) | 6 (23) | 10 (23) | 8 (20) | 3 (14) | 5 (15) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 20 (33) | 17 (35) | 8 (31) | 15 (34) | 15 (37) | 9 (43) | 12 (36) |

| Post-graduate degree | 17 (28) | 15 (32) | 10 (39) | 14 (32) | 13 (32) | 7 (33) | 12 (36) |

| Race | |||||||

| White/Caucasian | 45 (74) | 35 (75) | 20 (77) | 33 (75) | 31 (76) | 16 (76) | 27 (82) |

| Black/African American | 9 (15) | 6 (13) | 4 (15) | 6 (14) | 5 (12) | 2 (10) | 3 (9) |

| Other | 7 (11) | 6 (13) | 2 (8) | 5 (11) | 5 (12) | 3 (14) | 3 (9) |

| WIC recipient | 17 (28) | 11 (23) | 5 (19) | 11 (25) | 10 (24) | 4 (19) | 7 (21) |

| Current or recent smoker* | 9 (15) | 4 (9) | 1 (4) | 3 (6) | 4 (10) | 1 (5) | 3 (9) |

| Prenatal Care Provider(s) | |||||||

| Physician | 58 (95) | 45 (96) | 24 (92) | 42 (95) | 40 (98) | 20 (95) | 32 (97) |

| Midwife | 9 (15) | 8 (17) | 6 (23) | 7 (16) | 6 (15) | 3 (14) | 5 (15) |

| NP or PA | 10 (16) | 7 (15) | 3 (12) | 5 (11) | 7 (17) | 2 (10) | 5 (15) |

| Planned return to work** | |||||||

| No return or uncertain | 12 (20) | 8 (17) | 3 (12) | 8 (18) | 7 (17) | 4 (19) | 6 (18) |

| 5–8 weeks | 13 (21) | 9 (19) | 3 (12) | 6 (14) | 8 (20) | 1 (5) | 2 (6) |

| 9–12 weeks | 27 (44) | 22 (47) | 15 (58) | 22 (50) | 21 (51) | 13 (62) | 20 (61) |

| 13 weeks–1 year | 9 (15) | 8 (17) | 5 (19) | 8 (18) | 5 (12) | 3 (14) | 5 (15) |

| Planned duration of any bf | |||||||

| Unsure | 7 (12) | 3 (6) | 2 (8) | 3 (7) | 2 (5) | 1 (5) | 2 (6) |

| ≤ 6 months | 18 (30) | 13 (28) | 6 (23) | 12 (27) | 11 (27) | 3 (14) | 8 (24) |

| >6 months | 36 (59) | 31 (66) | 18 (69) | 29 (66) | 28 (68) | 17 (81) | 23 (70) |

| Planned duration of exclusive bf (n=60) | |||||||

| Unsure | 14 (23) | 7 (15) | 2 (8) | 7 (16) | 6 (15) | 3 (14) | 6 (18) |

| < 6 months | 8 (13) | 7 (15) | 4 (15) | 7 (16) | 7 (17) | 2 (10) | 5 (15) |

| ≥ 6 months | 38 (63) | 33 (70) | 20 (77) | 30 (68) | 28 (68) | 16 (76) | 22 (67) |

| Formula use in hospital | 23 (38) | 15 (32) | 5 (19) | 12 (27) | 13 (32) | 5 (24) | 9 (27) |

| First bf ≤ 1 hour after delivery | 30 (49) | 24 (51) | 14 (54) | 22 (50) | 23 (56) | 12 (57) | 17 (52) |

| Lactation consult in hospital | 48 (79) | 40 (85) | 21 (81) | 37 (84) | 34 (83) | 17 (81) | 27 (82) |

| Delivery method | |||||||

| Vaginal | 42 (69) | 30 (64) | 17 (65) | 28 (64) | 29 (71) | 15 (71) | 22 (67) |

| Cesarean section | 19 (31) | 17 (36) | 9 (35) | 16 (36) | 12 (29) | 6 (29) | 11 (33) |

| Vacuum or forceps use | 5 (8) | 4 (9) | 4 (15) | 4 (9) | 4 (10) | 3 (14) | 4 (12) |

| Male infant | 39 (64) | 31 (66) | 17 (65) | 29 (66) | 27 (66) | 13 (62) | 22 (67) |

Smoked during pregnancy or in 12 months prior to pregnancy;

No participants planned to return to work prior to 5 weeks postpartum

HM=human milk; bf=breastfeeding; NP=nurse practitioner; PA=physician’s assistant; WIC= WIC=Women, Infants, and Children Special Supplemental Nutrition Program

Note: While 48 women completed a two-week interview and provided self-report data on breastfeeding events in the hospital and after hospital discharge, one two-week interview was completed at four weeks due to difficulty establishing contact. Breastfeeding problems and behaviors for that participant are included in Week 4, rather than Week 2.

We identified breastfeeding problems by week from three sources: 1) problem checklists completed at enrollment and two weeks postpartum; 2) interview content at eight weeks; and 3) free-text app entries by participants throughout the study. JD scanned and coded free-text data from the eight-week interview and app entries using the problem checklists. New codes were created for problems that did not fit list categories. Problems were counted and summary statistics were calculated by week. App entries were also scanned and coded for reason(s) for formula use.

Two research assistants duplicated weekly data summaries (feeding count summaries and problem coding) for 13 of the 38 participants with app data (34% of those with data).

RESULTS

Sample and Baseline Feeding Characteristics

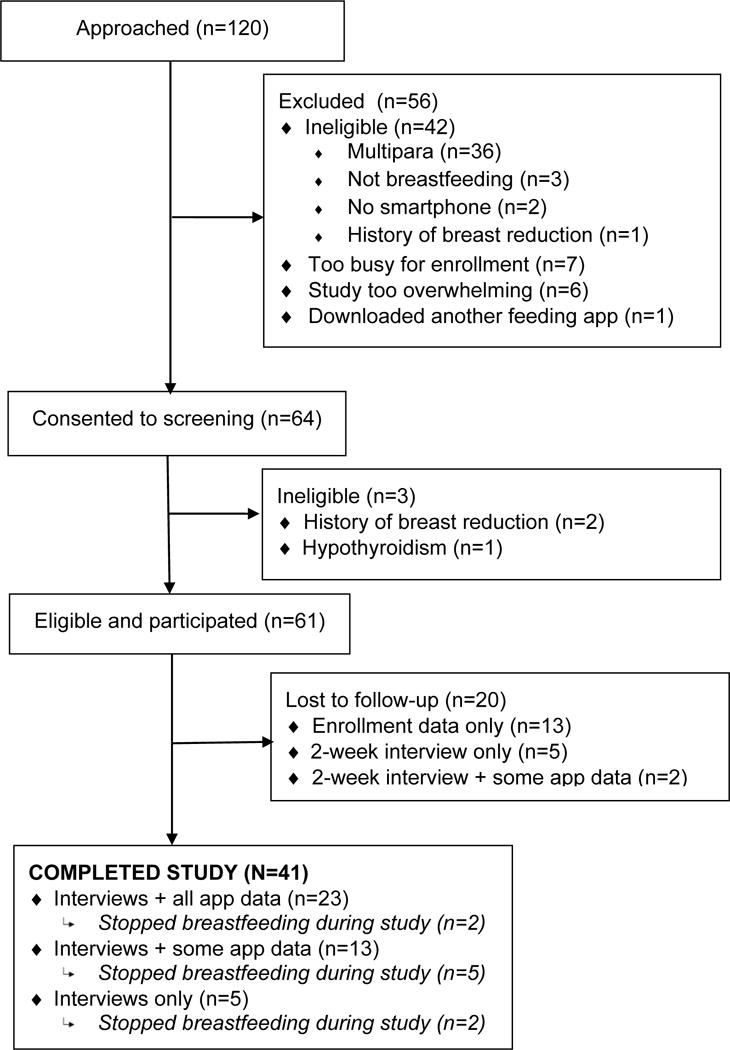

We enrolled 61 women into the study, 48 of whom provided any app data and/or completed follow-up interviews (Figure 1). Participants were 18–35 years old and delivered at 362/7–416/7 weeks. Two mothers were of Hispanic ethnicity. Infant birthweights ranged from 2596–4645 grams, and no infants were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit during the birth hospitalization (Tables 1 & 2). Nearly all mothers (n=58; 95%) reported receiving some type of breastfeeding education in pregnancy; the most common source was books, magazines, or pamphlets (n=27; 44%).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Table 2.

Continuous-level sample characteristics and relationship with exclusive and any breast milk at two and eight weeks postpartum (means and standard deviations).

| Characteristic | Baseline (n=61) |

2 Week Total (n=47) |

Breastfeeding Status at 2 weeks | 8 Week Total (n=41) |

Breastfeeding Status at 8 weeks | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exclusive HM (n=26) |

Any HM (n=44) |

Exclusive HM (n=21) |

Any HM (n=33) |

||||

| Maternal age (y) | 27.4±4.4 | 27.6±4.4 | 27.7± 4.4 | 27.6±4.5 | 27.8±4.1 | 28.8±3.8 | 28.3±4.2 |

| IIFAS score (baseline) | 64.9±6.3 | 66.2±6.1 | 67.4±5.5 | 66.5±6.1 | 65.4±5.8 | 67.6±4.9 | 66.0±6.1 |

| Combined EDA/PSS score (2 wks, n=45; 8 wks, n=40) | 11.0±4.9 | 8.2±5.7 | 7.5±5.7 | 8.4±5.7 | 11.2±3.0 | 10.2±2.4 | 11.2±2.7 |

| Weeks gestation at birth | 39.4±1.4 | 39.2± 1.2 | 39.4± 1.3 | 39.4± 1.3 | 39.5± 1.3 | 39.5± 1.2 | 39.5±1.3 |

| Infant birthweight (g) | 3389±449 | 3433±462 | 3359±456 | 3407±466 | 3423±482 | 3301±482 | 3406±509 |

HM=human milk; IIFAS=Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale; EDA/PSS=Emotional Distress-Anxiety (PROMIS)/Perceived Stress Scale

Note: While 48 women completed a two-week interview and provided self-report data on breastfeeding events in the hospital and after hospital discharge, one two-week interview was completed at four weeks due to difficulty establishing contact. Breastfeeding problems and behaviors for that participant are included in Week 4, rather than Week 2.

Among infants who received formula in the hospital (n=23), the median total formula volume given was 74ml (IQR=139ml; range=5–481 ml; n=22 infants, 24 undocumented volumes), the mean volume for a single formula feeding was 25ml (SD=14.5ml; n=105 feedings), and the average number of formula feedings was six (range: 1–20). Six infants received expressed milk in the hospital an average of two times (range 1–4), with a total volume per infant of 1–60mL. Nearly all enrolled women (98%) breastfed at-breast prior to hospital discharge, with 95% initiating within two hours post-birth. The average number of at-breast feeds in the 24 hours prior to discharge was 6.3 (SD=2; range 0–12). Among women completing a two-week interview, 94% (45/48) reported that a medical professional had observed at least one breastfeeding session during hospitalization.

Baseline IIFAS scores were slightly, but significantly lower among women using any formula at eight weeks (M=63.6), compared to those exclusively breastfeeding at that time (M=67.6) (t=−2.29, df=37, p=0.03). Women whose infants were given formula in the hospital were significantly less likely to be exclusively breastfeeding at two weeks postpartum compared to women whose infants received only human milk (uOR 0.3, 95% CI: 0.1–0.9, p=0.04).There were no other significant differences in feeding outcomes (any breastfeeding, exclusive breastfeeding, any formula) among Table 1 baseline sample characteristics.

Breastfeeding Behaviors through 8 Weeks Postpartum

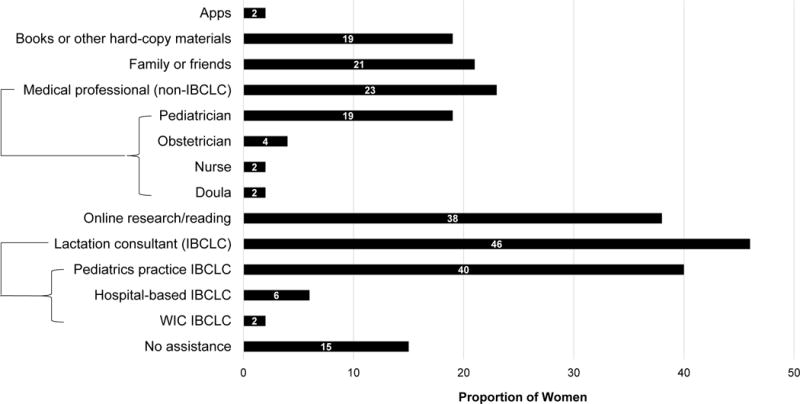

At the two-week interview, 85% (41/48) of women reported receiving breastfeeding assistance after hospital discharge; pediatric office-based lactation consultants were the most common source (Figure 2). Thirty-three (69%) mothers reported that their milk volume substantially increased within four days of delivery (after 4 days: 23%; never increased: 8%). At the two-week interview, 31 women (69%) reported that their infant had returned to or surpassed birth weight (below birth weight: 7%; not sure: 24%). At two weeks, eight women (13%) were using a nipple shield, and one was using a supplemental nursing system; 95% (n=41/43) of women feeding at breast at two weeks reported latching to occur immediately or within a few minutes.

Figure 2.

Proportion of women seeking breastfeeding assistance after birth hospitalization from various sources (maternal self-report at two-week interview; n=48).

WIC=Women, Infants, and Children Special Supplemental Nutrition Program

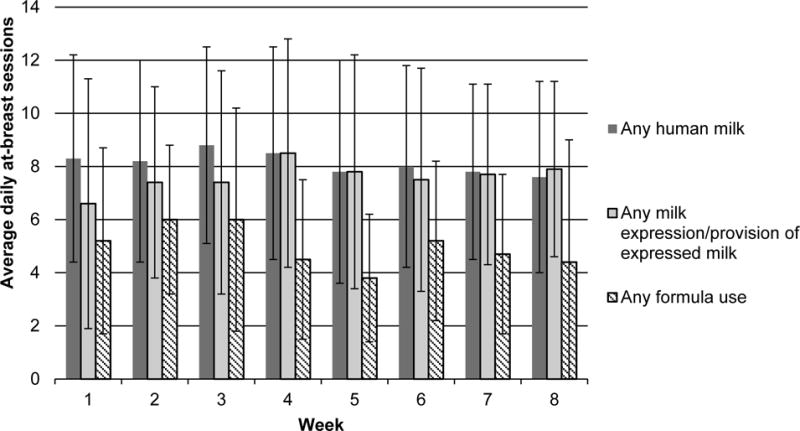

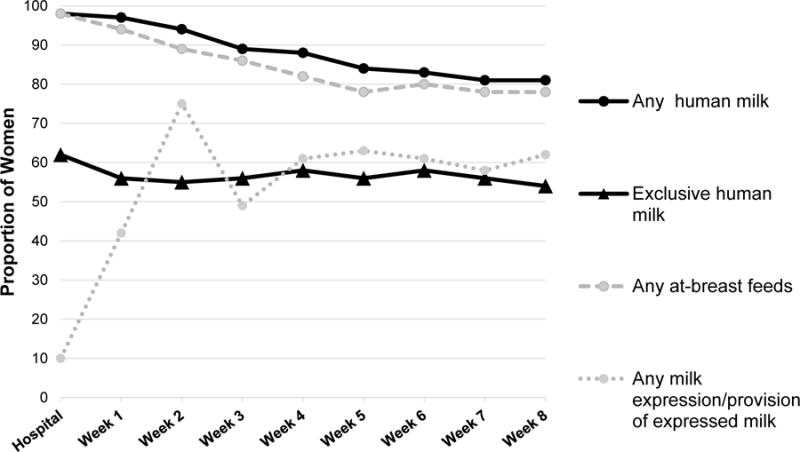

The average number of at-breast feeds (8.1/day) and proportion of women providing human milk exclusively remained relatively stable over eight weeks. The proportion of women doing any at-breast feeding fell over eight weeks, while the proportion of women expressing/pumping or providing any expressed milk generally trended upward (Figures 3 & 4). The most common reasons for milk expression were to relieve engorgement and to replace/supplement at-breast feeds due to breastfeeding difficulties (Table 3). By two weeks, 68% of women (n=34/50) had given formula at least once. By eight weeks, 77% (n=37/48) had given formula at least once. There was no significant association between milk expression at one or two weeks and any or exclusive human milk feeds at two or eight weeks postpartum.

Figure 3. Average number of daily at-breast feeding sessions with standard deviation bars for women giving any human milk, expressing milk/providing expressed milk, and providing any formula (app data).

Total participants included: Week 1, n=30; Week 2, n=29; Week 3, n=28; Week 4, n=25–26; Week 5, n=24–25; Week 6, n=24; Week 7, n=24; Week 8, n=21–22. Where n is a range, the number of participants with data available or complete varied by outcome (e.g., data for at-breast feeding sessions but not milk expression or formula use).

Figure 4. Proportion of women providing any and exclusive human milk, and engaging in any at-breast feeds and milk expression, by postpartum week (app and interview data).

Weeks 2 and 8 include data from both app and interviews. Total participants included: Hospital, n=61; Week 1, n=36; Week 2, n=47; Week 3, n=35–36; Week 4, n=33–34; Week 5, n=32; Week 6, n=30–31; Week 7, n=31–32; Week 8, n=39–41. Where n is a range, the number of participants with data available or complete varied by outcome (e.g., participants who logged any at-breast feeding did not necessarily have complete data to determine breastfeeding exclusivity).

Table 3.

Participant self-reported reason(s) for current milk expression at the time of the two-week interview (n=34).

| Reason(s) | Participants endorsing n (%) |

|---|---|

| Relieve engorgement | 11 (32) |

| Replace or supplement at-breast feeds with expressed milk, related to: | |

| Infant medical issues (poor weight gain, jaundice, dehydration; pediatrician advice) | 6 (18) |

| Breastfeeding difficulties (e.g., infant inefficiency at-breast, poor latch, sore nipples) | 7 (21) |

| Perception that bottle-feeding more convenient or predictable | 3 (9) |

| Desire or need for others to participate in infant feeding (e.g., “break” for mother, mother-infant separation) | 4 (12) |

| Mother’s preference not to breastfeed in public | 2 (6) |

| Establish a back-up or stock-pile of expressed milk, related to: | |

| Possibility of future breastfeeding difficulties | 2 (6) |

| Mother’s return to work | 2 (6) |

| Other (e.g., “just in case,” if unanticipated separation from infant) | 2(6) |

| Increase or maintain milk supply | 5 (15) |

| Visualize milk volume/ensure sufficient milk production | 2 (6) |

| Accustom infant to receiving bottles (e.g., mother’s return to work) | 2 (6) |

| Learn/practice how to use electric breast pump if needed in future | 1 (3) |

Among the 41 women who completed the study, nine (22%) stopped breastfeeding during the study (Week 1=2, Week 2=2, Week 4=1, Week 5=2, Week 7=1, Week 8=1). Reason(s) for breastfeeding cessation included inadequate volume of milk (n=6), latch problems (n=2), return to work without adequate time/space to express milk (n=1), and belief that breastfeeding was causing acid reflux in the infant (n=1). Reasons for formula supplementation included: pediatrician advice related to insufficient infant weight gain or jaundice; infant unsatisfied/fussy after at-breast feeds; perceived inadequate milk volume; convenience of formula when away from home; inadequate time/facilities to express milk upon return to work; maternal re-hospitalization with infrequent opportunities to express milk or breastfeed; sore nipples; and desire for partner to share in infant feeding.

While 67% (n=31/46) of women were on track to meet their goals for breastfeeding duration at the end of the study, just 22% (n=11/50) were on track to meet their goals for breastfeeding exclusivity; 15% (n=7/46) had no goal at enrollment for breastfeeding duration, and 30% (n=15/50) had no goal for length of exclusive breastfeeding.

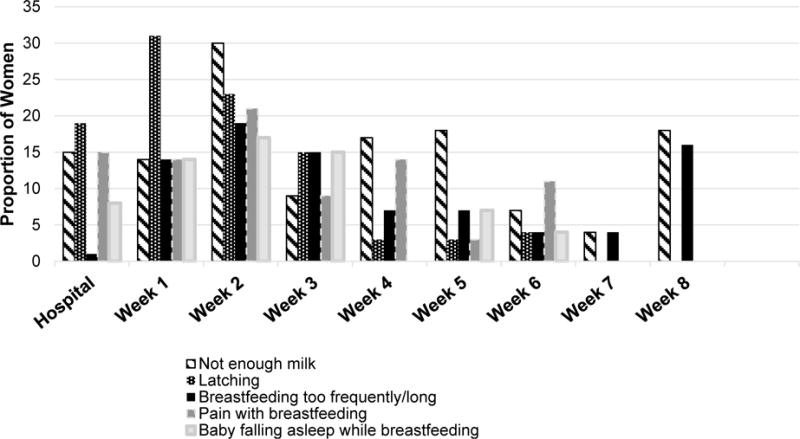

Breastfeeding Problems

Women identified 46 unique breastfeeding problems over eight weeks. Latching, perception of inadequate milk, pain, infant falling asleep while breastfeeding, and infant feeding too much were the most frequently identified breastfeeding concerns. All peaked at Week 2, with the exception of latching (Week 1). Problems trended downward over the course of the study, with a high of 81% of women endorsing at least one breastfeeding concern at Week 2 (n= 39/48) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Proportion of women endorsing the top five most frequently identified breastfeeding problems, via app diaries and interviews.

Proportion denominator encompasses the number of participants sending any app data for the week and/or completing 2 & 8 week interview where problems were assessed. Hospitalization, n=61; Week 1, n=36; Week 2, n=47; Week 3, n=33; Week 4, n=29; Week 5, n=29; Week 6, n=27; Week 7, n=27; Week 8, n=38.

The most frequently endorsed breastfeeding problems varied by week. During the birth hospitalization, top problems were latching (19%), pain (15%), and perception of inadequate milk (15%). During weeks 1–3 (n=33–47 women), top problems were latching (15–31%), fatigue with frequent feeds (15–19%), engorgement (3–19%), perception of inadequate milk (9–29%), and pain (9–21%). From weeks 4–5 (n=29–30 women), top problems included perception of inadequate milk (17–18%), device issues (e.g., electric breast pump, weaning from nipple shield) (3–10%), perceived breastfeeding-related gas or suspected reflux (7–10%), and pain (3–14%). From week 6–8 (n=27–38 women), top problems were perception of inadequate milk (4–18%), perceived breastfeeding-related gas or suspected reflux (7–11%), infant breastfeeding too much (4–16%), instituting a feeding schedule (3–11%), and managing breastfeeding when back to work (0–16%).

DISCUSSION

Among first-time mothers in our sample, the majority did not meet their goals for breastfeeding exclusivity. While the demographics of our sample (high socioeconomic status, healthy, White race) are typically associated with high rates of exclusive breastfeeding, we observed pervasive formula use and breastfeeding problems, particularly in the first two postpartum weeks. In addition, almost a quarter of participants stopped breastfeeding during the study. These findings are consistent with a previous prospective study which demonstrated that in a more diverse population of primiparous women, 21% weaned and almost half were not exclusively breastfeeding by eight weeks (Wagner et al., 2013). Similar to another recent longitudinal cohort study of primiparous women (Chantry et al., 2014), we found that in-hospital formula supplementation was positively associated with early, unintended formula use. Collectively, this research underscores a critical need to address modifiable barriers to exclusive, continued breastfeeding among primiparous women.

Notably, we observed high rates of milk expression throughout the study, with a peak at two weeks postpartum. This pattern paralleled a steady decrease in any at-breast feeds and a reduced number of daily at-breast feeds in those expressing milk. This suggests many women were likely replacing a portion of at-breast feeds with expressed milk beginning shortly after birth (confirmed by participants’ open-ended responses regarding reasons for milk expression at the two-week interview). Our data are consistent with a prospective cohort study in the U.S., which found that 75% (n=18/24) of primiparous women had expressed milk by four weeks postpartum (Geraghty, Davidson, Tabangin, & Morrow, 2012).

The recent widespread trend toward expressing milk, as a substitute for or in addition to at-breast feeds, as we observed in our data, was likely ushered in by several factors. This includes improvements in electric breast pump efficiency and design, near universal access to free, personal-use electric breast pumps through the 2010 Affordable Care Act, and conflicting societal expectations placing a high value on human milk with low tolerance for the act of breastfeeding, the latter perceived to limit maternal autonomy and involve greater ambiguity, effort, time, and pain (Crossland et al., 2016). Specific reasons provided for milk expression by our study participants at two weeks were similar to reasons provided by mothers of 1.5–4.5 month old infants part of the Infant Feeding Practices II Survey (IFPS II), with several exceptions. In the IFPS II, women also expressed milk to donate it and mix it with infant foods (Felice, Cassano, & Rasmussen, 2016). In our study, women cited expressing milk as a way to visualize how much milk they were producing, accustom their infant to taking bottles, and “practice” using the electric pump.

While women may perceive milk expression as equitable alternative to at-breast feeds when they cannot or do not prefer to breastfeed, exclusive expressed milk feedings may carry risks, including contamination of milk in the collection or storage process (Peters, McArthur, & Munn, 2016; Smith & Serke, 2016), degradation of immune properties during milk storage (Peters et al., 2016), reduced ability of the infant to regulate intake (Li, Fein, & Grummer-Strawn, 2010; Ventura, 2016), compositional differences in nutrients and fat between expressed milk and milk consumed at the breast (Garcia-Lara et al., 2012), and decreased protection against various infant morbidities (Boone, Geraghty, & Keim, 2016; Soto-Ramirez et al., 2013). In cases where milk expression minimizes potential formula use, however, these risks may be balanced. While we did not find an association between early milk expression and reduced breastfeeding exclusivity or duration, two studies powered to assess this relationship found that women expressing frequently between six and eighteen weeks were at higher risk for shortened breastfeeding duration compared to women not expressing or expressing less often (Felice et al., 2016; Jiang et al., 2015).

The most common breastfeeding problems identified by women in our sample, (latch problems, pain, perceived insufficient milk), are consistent with problems cited by primiparous women in the IFPS II (O’Sullivan, Perrine, & Rasmussen, 2015). We also identified more nuanced issues of first-time breastfeeding mothers throughout the first two months postpartum, including concerns about establishing consistency in a breastfeeding schedule, problems with devices (e.g., pumps, shields), and infant gastrointestinal issues attributed to breastfeeding (e.g., gas, reflux). Our data on breastfeeding problems provide a framework for the timing and content of general breastfeeding support and anticipatory guidance for primiparous women (Table 4).

Table 4.

Framework for delivery of postpartum breastfeeding support for primiparous women.

| Postpartum timing | Common problems/concerns | Potential considerations for counseling and assistance |

|---|---|---|

| First few days |

|

|

| Weeks 1–3 |

|

|

| Weeks 4–5 |

|

|

| Weeks 6–8 |

|

|

| Ongoing |

|

|

Confidence in our results is strengthened by presumed concurrent data capture of mothers’ feeding activities and experiences. In a prior analysis, we demonstrated the reliability of the app to track breastfeeding by comparing mothers’ 24-hour recall to app-reported breastfeeding intensity (Demirci & Bogen, 2016). Limitations of our study include a lack of generalizability to women of color and those of lower socioeconomic status. There was also a lack of power to examine potentially significant relationships between breastfeeding outcomes and sociodemographic variables, in-hospital and early postpartum events, and feeding behaviors. In addition, this analysis did not capture intensity or facets of problems at a detailed level.

Extrapolation of study results are also limited by the large amount of missing app feeding data. It was not always possible to determine whether missing data represented a logging omission or infrequent feeds. Likewise, it is unclear whether women who did not log breastfeeding problems had no problems or simply did not document them. In future work, methods triangulation could be utilized to counterbalance these issues, as well as uncover reasons for missing feeding data.

Loss to follow-up was another study limitation. Given our study’s focus and the societal importance attached to breastfeeding, it is possible that early drop-outs were also women that stopped breastfeeding prior to eight weeks. Thus, our data is likely an underrepresentation of formula use, breastfeeding problems, and breastfeeding cessation rates among primiparous women intending to exclusively breastfeed.

CONCLUSION

Real-time, app-based capture of breastfeeding thoughts and behaviors of first-time mothers during the first two months postpartum shows a trend toward pervasive breastfeeding problems, formula use, and replacement of at-breast feeds with expressed milk. Our data indicate that a generalized framework for delivery of postpartum breastfeeding support for first-time mothers should address a number of concerns, some of which tend to be ongoing and others which are more transient. Interventions should also address high rates of in-hospital formula supplementation among primiparous women reported by us and others. Future studies should examine the progression of the breastfeeding patterns we observed in our data beyond two months, as well as the relationship between the intensity and protraction of primiparous breastfeeding problems and breastfeeding outcomes with adequately powered, diverse samples.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Baby Connect for permitting use of their app. They also thank Kathleen Daniluk, Briana Deer, and Anastasia Alberty for their assistance with data entry and reliability. They are indebted to the mothers who participated in the study and shared their personal breastfeeding experiences with them.

FUNDING: This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NINR 1K99NR015106; PI: Demirci). Data collection was also supported through National Institutes of Health grant UL1TR001857.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Baby-Friendly USA, Inc. The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative guidelines and evaluation criteria for facilities seeking Baby-Friendly designation 2016 revision. 2016 Retrieved January 20, 2017, from http://www.babyfriendlyusa.org/get-started/the-guidelines-evaluation-criteria.

- Barbosa RW, Oliveira AE, Zandonade E, Neto ETS. Mothers’ memory about breastfeeding and sucking habits in the first months of life for their children. Revista Paulista de Pediatria. 2012;30(2):180–186. [Google Scholar]

- Boone KM, Geraghty SR, Keim SA. Feeding at the Breast and Expressed Milk Feeding: Associations with Otitis Media and Diarrhea in Infants. Journal of Pediatrics. 2016;174:118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnham L, Buczek M, Braun N, Feldman-Winter L, Chen N, Merewood A. Determining length of breastfeeding exclusivity: Validity of maternal report 2 years after birth. Journal of Human Lactation. 2014;30(2):190–194. doi: 10.1177/0890334414525682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breastfeeding among U.S. Children Born 2002–2013. CDC National Immunization Surveys. 2016 Retrieved September 21, 2016, from http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/NIS_data/

- Chantry CJ, Dewey KG, Peerson JM, Wagner EA, Nommsen-Rivers LA. In-hospital formula use increases early breastfeeding cessation among first-time mothers intending to exclusively breastfeed. Journal of Pediatrics. 2014;164(6):1339–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Binns CW, Liu Y, Maycock B, Zhao Y, Tang L. Attitudes towards breastfeeding – the Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale in Chinese mothers living in China and Australia. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2013;22(2):266–269. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.2013.22.2.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossland N, Thomson G, Morgan H, MacLennan G, Campbell M, Dykes F, Hoddinott P. Breast pumps as an incentive for breastfeeding: A mixed methods study of acceptability. Maternal & Child Nutrition. 2016;12(4):726–739. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Mora A, Russell DW, Dungy CI, Losch M, Dusdieker L. The Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale: Analysis of reliability and validity. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1999;29(11):2362–2380. [Google Scholar]

- Demirci JR, Bogen DL. Feasibility and acceptability of a mobile app in an ecological momentary assessment of early breastfeeding. Maternal & Child Nutrition. 2016 doi: 10.1111/mcn.12342. e-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felice JP, Cassano PA, Rasmussen KM. Pumping human milk in the early postpartum period: Its impact on long-term practices for feeding at the breast and exclusively feeding human milk in a longitudinal survey cohort. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2016;103(5):1267–1277. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.115733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Lara NR, Escuder-Vieco D, Garcia-Algar O, De la Cruz J, Lora D, Pallas-Alonso C. Effect of freezing time on macronutrients and energy content of breastmilk. Breastfeeding Medicine. 2012;7:295–301. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2011.0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraghty S, Davidson B, Tabangin M, Morrow A. Predictors of breastmilk expression by 1 month postpartum and influence on breastmilk feeding duration. Breastfeeding Medicine. 2012;7(2):112–117. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2011.0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang B, Hua J, Wang Y, Fu Y, Zhuang Z, Zhu L. Evaluation of the impact of breast milk expression in early postpartum period on breastfeeding duration: a prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth. 2015;15:268. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0698-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Fein SB, Grummer-Strawn LM. Do infants fed from bottles lack self-regulation of milk intake compared with directly breastfed infants? Pediatrics. 2010;125(6):e1386–1393. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIH PROMIS Assessment Center. PROMIS instruments available for use. 2012 Retrieved July 2, 2012, from http://www.nihpromis.org.

- O’Sullivan EJ, Perrine CG, Rasmussen KM. Early Breastfeeding Problems Mediate the Negative Association between Maternal Obesity and Exclusive Breastfeeding at 1 and 2 Months Postpartum. Journal of Nutrition. 2015;145(10):2369–2378. doi: 10.3945/jn.115.214619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrine Cria G, Scanlon Kelley S, Li Ruowei, Odom Erika, Grummer-Strawn Laurence M. Baby-Friendly hospital practices and meeting exclusive breastfeeding intention. Pediatrics. 2012;130(1):54–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters MD, McArthur A, Munn Z. Safe management of expressed breast milk: A systematic review. Women and Birth. 2016;29(6):473–481. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runyan JD, Steinke EG. Virtues, ecological momentary assessment/intervention and smartphone technology. Frontiers in Psychology. 2015;6:481. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SL, Serke L. Case Report of Sepsis in Neonates Fed Expressed Mother’s Milk. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing: JOGNN. 2016;45(5):699–705. doi: 10.1016/j.jogn.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Ramirez N, Karmaus W, Zhang H, Davis S, Agarwal S, Albergottie A. Modes of infant feeding and the occurrence of coughing/wheezing in the first year of life. Journal of Human Lactation. 2013;29(1):71–80. doi: 10.1177/0890334412453083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura AK. Developmental Trajectories of Bottle-Feeding During Infancy and Their Association With Weight Gain. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2016 doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000372. e-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner Erin A, Chantry Caroline J, Dewey Kathryn G, Nommsen-Rivers Laurie A. Breastfeeding concerns at 3 and 7 days postpartum and feeding status at 2 months. Pediatrics. 2013;132(4):e865–875. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warttig SL, Forshaw MJ, South J, White AK. New, normative, English-sample data for the Short Form Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4) Journal of Health Psychology. 2013;18(12):1617–1628. doi: 10.1177/1359105313508346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson I, Leeming D, Lyttle S, Johnson S. ‘It should be the most natural thing in the world’: Exploring first-time mothers’ breastfeeding difficulties in the UK using audio-diaries and interviews. Maternal & Child Nutrition. 2012;8(4):434–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00328.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]