Abstract

Bartonella spp. are parasites of mammalian erythrocytes and endothelial cells, transmitted by blood-feeding arthropod ectoparasites. Different species of rodents may constitute the main hosts of Bartonella, including several zoonotic species of Bartonella. The aim of this study was to identify and compare Bartonella species and genotypes isolated from rodent hosts from the South Sinai, Egypt. Prevalence of Bartonella infection was assessed in rodents (837 Acomys dimidiatus, 73 Acomys russatus, 111 Dipodillus dasyurus, and 65 Sekeetamys calurus) trapped in 2000, 2004, 2008, and 2012 in four dry montane wadis around St. Katherine town in the Sinai Mountains. Total DNA was extracted from blood samples, and PCR amplification and sequencing of the Bartonella-specific 860-bp gene fragment of rpoB and the 810-bp gene fragment of gltA were used for molecular and phylogenetic analyses. The overall prevalence of Bartonella in rodents was 7.2%. Prevalence differed between host species, being 30.6%, 10.8%, 9.6%, and 3.6% in D. dasyurus, S. calurus, A. russatus, and A. dimidiatus, respectively. The phylogenetic analyses of six samples of Bartonella (five from D. dasyurus and one from S. calurus) based on a fragment of the rpoB gene, revealed the existence of two distinct genetic groups (with 95–96% reciprocal sequence identity), clustering with several unidentified isolates obtained earlier from the same rodent species, and distant from species that have already been described (90–92% of sequence identity to the closest match from the GenBank reference database). Thus, molecular and phylogenetic analyses led to the description of two species: Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae n. sp. and Candidatus Bartonella sanaae n. sp. The identification of their vectors and the medical significance of these species need further investigation.

Keywords: : Acomys, Bartonella, Dipodillus dasyurus, genotypes, rodent, Sekeetamys calurus, Sinai

Introduction

Bartonella spp. are gram-negative bacteria found in mammalian erythrocytes and endothelial cells and are transmitted by blood-feeding arthropod ectoparasites (Birtles 2005, Morick et al. 2011). The genus Bartonella belongs to the Alphaproteobacteria class, order Rhizobiales, and family Bartonellaceae (Inoue et al. 2010). Among 33 confirmed Bartonella species to date, more than half are hosted by rodent species. Moreover, at least seven species have been linked to human diseases: Bartonella elizabethae (Daly et al. 1993), Bartonella grahamii (Birtles et al. 1995), Bartonella rochalimae (Lin et al. 2008), Bartonella tamiae (Kosoy et al. 2008), Bartonella tribocorum (Heller et al. 1998), Bartonella vinsonii (Welch et al. 1999), and Bartonella washoensis (Kosoy et al. 2003), most of them being associated with a wide range of symptoms, including fever, myocarditis, endocarditis, lymphadenitis, and hepatitis (Buffet et al. 2013). Certain Bartonella species are known to cause a febrile bacteremia in humans and other mammals, including Bartonella quintana, the agent of trench fever, and Bartonella henselae, causing a cat scratch disease (Vayssier-Taussat et al. 2016).

In almost all countries, wild rodents are infected by an extremely diverse range of Bartonella species/strains and generally with a high prevalence. Examples include rodents in North America (Kosoy et al. 1997), Asia (Ying et al. 2002, Inoue et al. 2008, 2010), Australia (Gundi et al. 2009), Africa (Bajer et al. 2006, Sato et al. 2013), and Europe (Birtles et al. 1995, Tea et al. 2004, Welc-Faleciak et al. 2010, Paziewska et al. 2011). Prevalence of Bartonella infections in rodents ranges from 6% in the Greater Jakarta area in Indonesia (Winoto et al. 2005) to 70% in the Russian Far East (Mediannikov et al. 2005, Morick et al. 2011). To date, the arthropods that have been confirmed as competent vectors for Bartonella are the sand fly Lutzomyia verrucarum as a vector for Bartonella bacilliformis (Noguchi and Battistini 1926) and the louse Pediculus humanus humanus as a vector for B. quintana (Swift 1920). Moreover, recent studies have revealed that a range of flea species may also play a role as vectors of Bartonella: the flea Ctenophthalmus nobilis as a vector for B. grahamii and Bartonella taylorii (Bown et al. 2004), Ctenocephalides felis as a vector for B. henselae (Chomel et al. 1996), the fleas Megabothris turbidus, M. walkeri, Hystrichopsylla talpae, Ctenophthalmus assimilis, and Ctenophthalmus agyrtes as vectors for B. taylorii (Jusko 2015), and the fleas M. turbidus, M. walkeri and C. assimilis, as vectors of B. grahamii (Jusko 2015).

Because of the difficulties in identifying Bartonella and distinguishing between the species through the use of conventional microscopy and biochemical tests, molecular approaches have been developed based on PCR, followed by sequencing of several housekeeping genes, such as citrate synthase (gltA) and RNA polymerase beta subunit (rpoB) genes (Norman et al. 1995, Renesto et al. 2001, La Scola et al. 2003, Inoue et al. 2008). In particular, the molecular marker genes, rpoB and gltA, have been widely used for differentiating between species because of the much lower degrees of taxonomically relevant variability in these genes within Bartonella species (La Scola et al. 2003). Therefore, variation in the rpoB and gltA genes can be applied as a cutoff criterion for the designation of novel species in the genus Bartonella.

Our long-term studies on temporal changes in the hemoparasite community (Babesia, Bartonella, Haemobartonella, Hepatozoon, and Trypanosoma) of rodents in Egypt (Behnke et al. 2000, Bajer et al. 2006) have led to the description of a novel species—Babesia behnkei (Bajer et al. 2014a), and provided molecular evidence for the existence of two different variants of Hepatozoon and two novel variants of Trypanosoma acomys in Acomys dimidiatus (Alsarraf et al. 2016). The aim of the current study was to identify the Bartonella species/strains in rodent hosts, including Wagner's gerbil Dipodillus dasyurus and the bushy-tailed jird Sekeetamys calurus, inhabiting isolated montane valleys in the Sinai Massif, Egypt.

Materials and Methods

Field studies in Sinai, Egypt

Fieldwork was conducted over 4–5-week periods in August and September in 2000, 2004, 2008, and 2012 and was based at the Environmental Research Centre of Suez Canal University (2000, 2004) or at Fox Camp (2008, 2012) in the town of St. Katherine, South Sinai, Egypt. Trapping was carried out in four montane wadis (dry valleys) in the vicinity of St. Katherine. The local environment and general features of the four study sites (W. Arbaein, W. Gebal, W. Tlah, W. Gharaba), as well as their spatial relationships with one another, have been described previously (Behnke et al., 2000). Details of the number of rodents sampled by site and year of study are presented in Table 1. At each site, rodents were caught live in Sherman traps that had been placed among the rocks and boulders around walled gardens and occasionally along the lower slopes of wadis. These were set out at dusk and inspected in the early morning before exposure to direct sunlight. All traps were brought into the local or base camp, where the animals were removed, identified, and processed. Traps were reset the following evening.

Table 1.

Prevalence of Bartonella spp. by Host, Site, and Year

| Acomys dimidiatus | Acomys russatus | Dipodillus dasyurus | Sekeetamys calurus | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Host Site | Infection | % | Infection | % | Infection | % | Infection | % | Total | % |

| 2000 | Arbaein | 2/58 | 3.44 | ¼ | 25 | 1/3 | 33.33 | ND | ND | 4/65 | 6.15 |

| Gebal | 1/28 | 3.57 | 0/4 | 0 | 2/6 | 33.33 | ND | ND | 3/38 | 7.89 | |

| Gharaba | 1/28 | 3.57 | 0/1 | 0 | 0/2 | 0 | ND | ND | 1/31 | 3.22 | |

| Tlah | 0/46 | 0 | 2/6 | 33.33 | 0/2 | 0 | ND | ND | 2/54 | 3.70 | |

| Total | 4/160 | 2.5 | 3/15 | 20 | 3/13 | 23.07 | ND | ND | 10/188 | 5.31 | |

| 2004 | Arbaein | 0/43 | 0 | 0/1 | 0 | 1/4 | 25 | ND | ND | 1/48 | 2.08 |

| Gebal | 10/43 | 23.25 | 1/8 | 12.5 | 15/16 | 93.75 | ND | ND | 26/67 | 38.80 | |

| Gharaba | 1/60 | 1.66 | 0/3 | 0 | 0/7 | 0 | ND | ND | 1/70 | 1.42 | |

| Tlah | 7/70 | 10 | 3/8 | 37.5 | 0/0 | 0 | 0/2 | 0 | 10/80 | 12.50 | |

| Total | 18/216 | 8.33 | 4/20 | 16.66 | 16/27 | 59.25 | 0/2 | 0 | 38/265 | 14.33 | |

| 2008 | Arbaein | 1/66 | 1.51 | 0/3 | 0 | 0/2 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 1/71 | 1.40 |

| Gebal | 0/43 | 0 | 0/6 | 0 | 0/15 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0/64 | 0 | |

| Gharaba | 0/52 | 0 | 0/3 | 0 | 0/2 | 0 | 0/8 | 0 | 0/65 | 0 | |

| Tlah | 1/80 | 1.25 | 0/8 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0/6 | 0 | 1/94 | 1.06 | |

| Total | 2/241 | 0.82 | 0/20 | 0 | 0/19 | 0 | 0/14 | 0 | 2/294 | 0.68 | |

| 2012 | Arbaein | 5/64 | 7.81 | 0/0 | 0 | 3/14 | 21.42 | 0/2 | 0 | 8/80 | 10 |

| Gebal | 0/46 | 0 | 0/7 | 0 | 11/22 | 50 | 2/5 | 40 | 13/80 | 16.25 | |

| Gharaba | 1/52 | 1.92 | 0/2 | 0 | 1/16 | 6.25 | 2/17 | 11.76 | 4/87 | 4.59 | |

| Tlah | 0/58 | 0 | 0/9 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 3/25 | 12 | 3/92 | 3.26 | |

| Total | 6/220 | 2.72 | 0/18 | 0 | 15/52 | 28.84 | 7/49 | 14.28 | 28/339 | 8.25 | |

| Overall total | 30/837 | 3.58 | 7/73 | 9.58 | 34/111 | 30.63 | 7/65 | 10.76 | 78/1086 | 7.18 | |

At inspection, each of the four rodent species (A. dimidiatus, Acomys russatus, D. dasyurus, and S. calurus) was sexed, weighed, measured, and scrutinized for obvious lesions as described by Behnke et al. (2004). Ectoparasites visible during field examination were removed and placed into 70% ethanol. Blood and fecal samples were taken and animals were then either fur marked individually, or ear clipped and released close to the point of capture, or returned to the main camp at St. Katherine for autopsy. A maximum of 40% of the captured rodents from each site were culled (by agreement with the St. Katherine National Protectorate authorities).

Blood collection and DNA extraction

Thin blood smears were prepared from drops of blood taken from the retro-orbital plexus using heparinized capillary tubes of animals lightly anesthetized with ether during examination in the field and from the heart of those that were autopsied under terminal anesthesia with ether. Blood smears were air-dried, fixed in absolute methanol, and stained for 1 h in Giemsa stain in buffer at pH 7.2 or by Hemacolor stain (Merck, Germany). Each smear was examined under oil immersion ( × 1000 magnification). Erythrocytes infected with Bartonella spp. were counted in 200 fields of vision. Microscopical observation of stained blood smears was used as the only detection method for study in 2000. Thereafter, from 2004 onward, molecular techniques were also used. For these, 200 μL of whole blood was collected into 0.001 M EDTA from all the culled animals and frozen at −20°C. Total DNA was extracted from whole blood using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen) and stored at a temperature of −20°C.

Molecular characterization

For the amplification of the rpoB gene fragment, we used the primers 1400F 5′-CGCATTGGCTTACTTCGTATG-3′ and 2300R 5′-GTAGACTGATTAGAACGCTG-3′ (Renesto et al. 2001). The PCR program was modified starting by denaturation for 5 min in 95°C, followed by 38 cycles (95°C for 45 s, 55°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 45 s), and then an extension step at 72°C for 7 min. For the gltA gene, we used the primers CS140f 5′-TTACTTATGATCC(GT)GG(CT)TTTA-3′ (Birtles and Raoult 1996) and CS1137r 5′-AATGCAAAAAGAACAGTAAACA-3′ (Norman et al. 1995). The PCR was started by denaturation for 2 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 54°C, and 2 min at 72°C, with a final extension step of 7 min at 72°C. Reactions were performed in a 20 μL volume, containing 1 × PCR buffer, 0.2 U Taq polymerase (Thermo Scientific), 1 μM of each primer, 2 mM dNTP (A&A Biotechnology), and 2 μL of the extracted DNA sample. Negative controls were carried out in the absence of template DNA and the positive control was genomic DNA of B. grahamii from our earlier study (Alsarraf 2012, Bajer et al. 2014b). PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel, stained with Midori Green stain (Nippon Genetics GmbH), and sequenced by a private company (Genomed S.A., Poland).

Genotyping and phylogenetic analysis

Analysis of 860-bp rpoB gene fragment

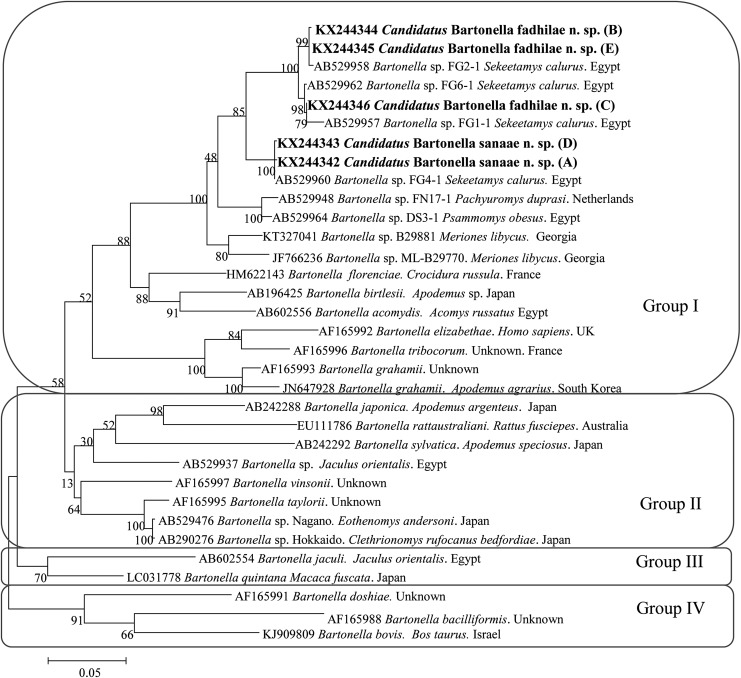

From the eight Bartonella-positive rodent samples (Table 2), six Bartonella rpoB sequences were obtained from D. dasyurus and one from S. calurus (Table 2). In addition, one Bartonella sample obtained from A. dimidiatus from W. Tlah was genotyped by the amplification and sequencing of a shorter 333-bp fragment of the rpoB gene (Paziewska et al. 2011). All obtained sequences were aligned using MEGA v. 6.0 (Tamura et al. 2013). All our consensus sequences have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession numbers KX244342, KX244343, KX244344, KX244344, and KX244346). Akaike information criterion was used in the jModel Test to identify the most appropriate model of nucleotide substitution. A representative tree for rpoB sequences was constructed using MEGA v. 6.0, applying the maximum likelihood method and a Hasegawa–Kishino–Yano (I+G) model (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Origin of the Samples of Bartonella spp. from Rodents Used for Genotyping and Phylogenetic Analysis

| Gene | Sample number | Sample code | Host | Site | Year | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rpoB | 49 | A | D. dasyurus | Arbaein | 2012 | KX244342 |

| 91 | B | D. dasyurus | Gebal | 2012 | KX244344 | |

| 122 | C | S. calurus | Gebal | 2012 | KX244346 | |

| 59 | D | D. dasyurus | Gebal | 2004 | KX244342 | |

| 104 | E | D. dasyurus | Gebal | 2004 | KX244345 | |

| 224 | F | A. dimidiatus | Tlah | 2004 | ||

| gltA | 49 | A | D. dasyurus | Arbaein | 2012 | KX137114 |

| 91 | B | D. dasyurus | Gebal | 2012 | KX137116 | |

| 122 | C | S. calurus | Gebal | 2012 | KX137118 | |

| 58 | G | D. dasyurus | Gebal | 2004 | KX137115 | |

| 176 | H | D. dasyurus | Gharaba | 2012 | KX137117 |

FIG. 2.

The phylogenetic tree of Bartonella spp., based on a fragment of the rpoB gene, was inferred using the maximum likelihood method and a Hasegawa–Kishino–Yano (G+I). The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) are shown next to the branches. The analysis involved 33 nucleotide sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA6.0.

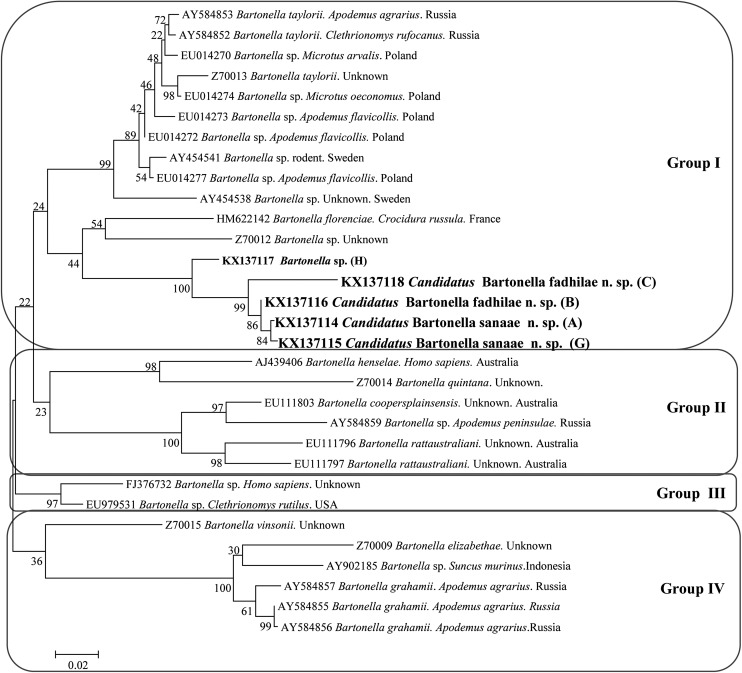

Analysis of 810-bp gltA gene fragment

The analysis of eight Bartonella-positive rodent samples (Table 2) yielded four Bartonella gltA sequences from D. dasyurus and one sequence from S. calurus (Table 2). All obtained sequences were aligned using MEGA v. 6.0 (Tamura et al. 2013). All obtained sequences of Bartonella spp. have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession numbers KX137114, KX137115, KX137116, KX137117, and KX137118). Akaike information criterion was used in the jModel Test to identify the most appropriate model of nucleotide substitution. A representative tree for gltA sequences was obtained using the maximum likelihood method and a Hasegawa–Kishino–Yano (+G) model (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

The phylogenetic tree of Bartonella spp., based on a fragment of the gltA gene, was inferred using the maximum likelihood method and a Hasegawa–Kishino–Yano (G). The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) are shown next to the branches. The analysis involved 31 nucleotide sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA6.0.

Statistical analyses

Prevalence (percentage of animals infected) was calculated based on microscopical observations and PCR results. For analysis of prevalence, we used maximum likelihood techniques based on log-linear analysis of contingency tables in the software package IBM SPSS (version 21.0.; IBM Corp). Initially, a full factorial model was fitted, incorporating as factors host species (four levels), year of study (four levels, each of the four surveys), and site (four levels, the four wadis). The presence of Bartonella was implemented as “infection” and was considered as a binary factor (two levels, present or absent).

Ethical issue

Rodents from St. Katherine National Protectorate were sampled by agreement with the St. Katherine National Protectorate authorities obtained for each phase of the fieldwork. A maximum of 40% of the captured rodents from each site were culled by agreement with the St. Katherine National Protectorate authorities.

Results

Family Bartonellaceae, Gieszczykiewicz 1939 (Vos et al. 2009)

Genus Bartonella Strong et al. 1915 (Vos et al. 2009)

Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae n. sp.

Type-hosts: Wagner's gerbil, D. dasyurus (Rodentia, Muridae, Gerbillinae) and bushy-tailed jird, S. calurus (Rodentia, Muridae, Gerbillinae).

Type-locality: Wadi Gebal in the Sinai Mountains, Egypt.

Type-specimens: I.91 from D. dasyurus, sampled on August 21, 2012, in W. Gebal, Sinai Mountains, Egypt, and I.122 from S. calurus sampled on August 23, 2012, in W. Gebal, Sinai Mountains, Egypt.

Vector: Currently unknown.

Representative sequences: GenBank KX244344 and KX244346 (rpoB gene); KX137116 and KX137118 (gltA gene).

ZooBank registration: Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae n. sp. act:A9459D34-9962-4DA6-B82B-B748277602CF

Candidatus Bartonella sanaae n. sp.

Type-host: Wagner's gerbil, D. dasyurus (Rodentia, Muridae, Gerbillinae)

Type-locality: Wadi Gebal in the Sinai Mountains, Egypt.

Other localities: Wadi Arbaein in Sinai Mountains, Egypt.

Type-specimens: I.59 from D. dasyurus, sampled on August 21, 2004, in W. Gebal, Sinai Mountains, Egypt, and I.49 from D. dasyurus, sampled on August 18, 2012, in W. Arbaein, Sinai Mountains, Egypt.

Vector: Currently unknown.

Representative sequences: GenBank KX244343, KX244342 (rpoB gene), KX137114, KX137115 (gltA gene).

ZooBank registration: act:76DC10B7-9536-4600-930A-2920DD483C3F

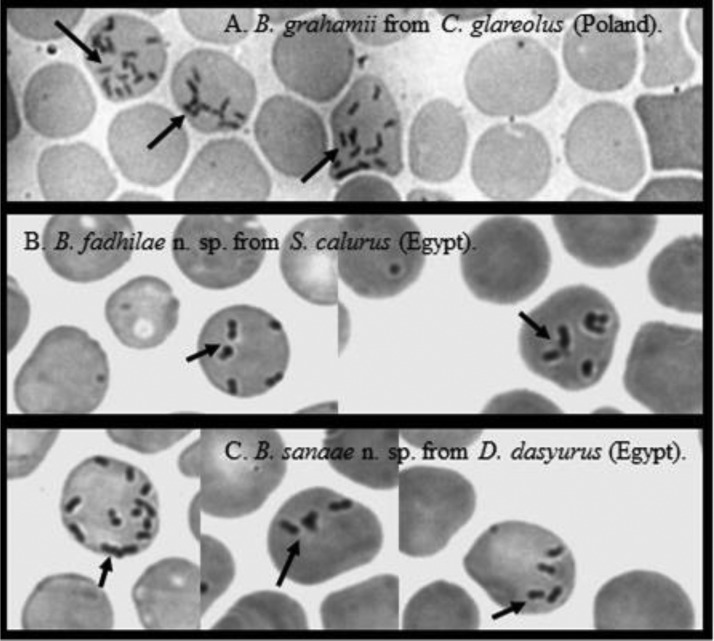

Morphological characteristics

Microscopic examination of blood smears revealed that Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae n. sp., Candidatus Bartonella sanaae n. sp., and other samples of Bartonella sp. were indistinguishable morphologically as viewed through conventional microscopy (Fig. 1). Individual bacteria appeared as thin, short, pleomorphic bacilli or coccobacilli and were also morphologically indistinguishable from other Bartonella spp., known to occur in rodent hosts (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

(A) The type-forms of Bartonella grahamii from bank vole Clethrionomys glareolus from NE of Poland. (B) The type-forms of Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae n. sp. from bushy-tailed jird Sekeetamys calurus from W. Gebal, Sinai Massif (Egypt). (C) The type-forms Candidatus Bartonella sanaae n. sp. from Wagner's gerbil Dipodillus dasyurus from W. Arbaein, Sinai Massif (Egypt).

Field studies: spatiotemporal dynamics of Bartonella infection in rodents

Altogether, 1086 rodents from the Sinai Mountains, Egypt, were sampled in four montane valleys (wadis) in 2000, 2004, 2008, and 2012, including 837 individuals of the spiny mouse A. dimidiatus, 111 Wagner's gerbils D. dasyurus, 73 A. russatus, and 65 bushy-tailed jirds S. calurus (Table 1). Overall prevalence of Bartonella spp. was highest in Wagner's gerbils (30.63%) in comparison with A. dimidiatus (3.58%) or A. russatus (9.58%) and S. calurus (10.76%) (host species × Bartonella infection: χ2 = 59.3, df = 3, p < 0.001) (Table 1). The highest prevalence of Bartonella infection in the rodent communities from the Sinai was recorded in 2004—14.33% (year of study × Bartonella infection: χ2 = 47.221, df = 3, p < 0.001). Infections with Bartonella spp. were identified in all host populations and in all study sites, but we noted the highest prevalence in W. Gebal in three surveys 2000, 2008, and 2012 and the lowest was in W. Gharaba in 2000, 2004, and 2008 (year of study × site × Bartonella infection: χ2 = 28.1, df = 9, p = 0.001) (Table 1).

Molecular identification of Bartonella sp. from A. dimidiatus, D. dasyurus, and S. calurus

We amplified the DNA of Bartonella spp. from eight rodent samples, six were from D. dasyurus, one from S. calurus, and one from A. dimidiatus (Table 2). Good quality sequences of both molecular markers rpoB and gltA were obtained only for three rodents: samples A and B from D. dasyurus and sample C from S. calurus (Table 2). Bartonella samples from the remaining rodents (D–H) were genotyped based only on a single marker (rpoB or gltA; Table 2).

Only one sample was successfully identified through a BLAST search in the GenBank database: sample F from A. dimidiatus was recognized based on the short fragment of the rpoB gene (333 bp). The BLAST revealed 99.37% identity of sample F to B. acomydis from A. russatus from Egypt (accession number AB602556) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Percent of Homology of Sequences for Bartonella fadhilae n. sp. and Bartonella sanaae n. sp. with the Closest Bartonella spp. Using the rpoB Gene

| Bartonella florenciae HM622143 | Bartonella grahamii AF165993 | Sample A Candidatus Bartonella sanaae | Sample B Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae | Sample C Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae | Sample D Candidatus Bartonella sanaae | Sample E Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae | Sample F 224_Tlah_A. dimidiatus | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Similarity | Cov. | Similarity | Cov. | Similarity | Cov. | Similarity | Cov. | Similarity | Cov. | Similarity | Cov. | Similarity | Cov. | Similarity | Cov. | |

| Bartonella acomydis AB602556 | 764/825 92.60% |

100% | 704/789 89.22% |

100% | 718/789 91.00% |

100% | 704/786 89.56% |

99% | 708/789 89.73% |

100% | 719/789 91.12% |

100% | 707/789 89.60% |

100% | 317/319 99.37% |

40% |

| B. florenciae HM622143 | 709/788 89.97% |

100% | 723/788 91.75% |

100% | 708/785 90.19% |

99% | 712/788 90.35% |

100% | 724/788 91.87% |

100% | 711/788 90.22% |

100% | 294/321 91.58% |

40% | ||

| B. grahamii AF165993 | 702/788 89.08% |

100% | 696/785 88.66% |

99% | 702/788 89.08% |

100% | 703/788 89.21% |

100% | 699/788 88.70% |

100% | 274/322 85.09% |

40% | ||||

| Sample A Candidatus Bartonella sanaae | 748/785 95.28% |

99% | 750/788 95.17% |

100% | 785/788 99.61% |

100% | 751/788 95.30% |

100% | 290/321 90.34% |

41% | ||||||

| Sample B Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae | 776/785 98.85% |

99% | 749/785 95.41% |

99% | 758/759 99.86% |

99% | 286/321 89.09% |

40% | ||||||||

| Sample C Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae | 751/788 95.30% |

100% | 779/788 99.85% |

100% | 286/321 89.09% |

40% | ||||||||||

| Sample D Candidatus Bartonella sanaae | 752/788 95.43% |

100% | 290/321 90.34% |

40% | ||||||||||||

| Sample E Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae | 286/321 89.09% |

40% | ||||||||||||||

Cov., coverage.

Among the seven remaining Bartonella samples, seven different variants with varying degrees of similarity were recognized based on two markers (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 4.

Percent of Homology of Sequences for Bartonella fadhilae n. sp. and Bartonella sanaae n. sp. with the Closest Bartonella spp. Using the gltA Gene

| B. acomydis AB602553 | B. grahamii AY584855 | Sample A Candidatus Bartonella sanaae | Sample B Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae | Sample C Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae | Sample G Candidatus Bartonella sanaae | Sample H Bartonella sp. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Similarity | Cov. | Similarity | Cov. | Similarity | Cov. | Similarity | Cov. | Similarity | Cov. | Similarity | Cov. | Similarity | Cov. | |

| B. florenciae HM622142 | 300/317 94.63% |

26% | 861/975 88.30% |

99% | 837/922 90.78% |

99% | 684/761 89.88% |

99% | 596/667 89.35% |

92% | 799/887 90.07% |

99% | 701/768 91.27% |

99% |

| B. acomydis AB602553 | 293/330 88.78% |

55% | 299/322 92.85% |

55% | 215/234 91.88% |

55% | 149/164 90.85% |

47% | 243/261 93.10% |

56% | 192/206 93.20% |

56% | ||

| B. grahamii AY584855 | 819/928 88.25% |

99% | 667/762 87.53% |

99% | 574/667 86.05% |

92% | 780/887 87.93% |

99% | 682/766 89.03% |

99% | ||||

| Sample A Candidatus Bartonella sanaae | 752/762 98.68% |

100% | 640/666 96.09% |

92% | 864/868 99.53% |

100% | 739/768 96.22% |

100% | ||||||

| Sample B Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae | 643/669 96.11% |

92% | 752/762 98.68% |

100% | 707/735 96.19% |

100% | ||||||||

| Sample C Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae | 639/666 95.94% |

81% | 625/666 93.84% |

81% | ||||||||||

| Sample G Candidatus Bartonella sanaae | 740/768 96.35% |

100% | ||||||||||||

Sequences of the rpoB gene from samples A and D, both from Wagner's gerbil, showed 99.61% identity to each other and varied by only three nucleotides and, therefore, constituted a single group (R1) (Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/vbz). This group showed the highest degree of similarity (91–92%) to Bartonella florenciae from the greater white-toothed shrew Crocidura russula from France. However, the sequences that we obtained differed by 64–65 nucleotides from the reference sequence of B. florenciae (HM622143). Sequences of the rpoB gene of samples B, C, and E, from two D. dasyurus and one S. calurus individuals, showed a high reciprocal similarity (98.85–99.86%) and differed only by 1–11 nucleotides (Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. S1), and thus formed a separate group of Bartonella variants, named R2. For this group, the BLAST search revealed the highest similarity level (90–91%) to B. florenciae, although the sequences differed by as many as 67–77 nucleotides to the reference sequence (HM622143) (Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. S1). The similarity between those two groups of variants, R1 and R2, was 95–96% and the sequences varied between these two groups by 31–38 nucleotides.

The phylogenetic analyses of the rpoB sequences of our samples described in this work and the reference sequences from the GenBank database revealed the presence of three major groups (Fig. 2). In the first group our sequences clustered in two subgroups, R1 and R2, creating a polyphyletic group together with several unnamed isolates of Bartonella from S. calurus from Egypt (Inoue et al. 2009). The two subgroups of Bartonella sequences, R1 and R2, were clearly separated and distinct from each other, as confirmed by the significant bootstrap support (Fig. 2). Almost all of the Bartonella spp. in the phylogenetic tree that we derived are from rodents, and include two sequences from pathogenic species: B. elizabethae from humans from the United Kingdom and B. bacilliformis, but both are distinct from Bartonella spp. described by us.

As the analysis of the gltA sequences showed high similarity among sequences A, B, and G (98.7–99.5%) and our sequences differed only by 4–10 nucleotides (Table 4 and Supplementary Fig. S2), they constitute one group of Bartonella variants (G1). Interestingly, all these sequences were obtained from one host species, D. dasyurus from W. Gebal (Table 3). A BLAST search revealed that the G1 group showed the highest similarity (91–93%) to B. acomydis from A. russatus from Egypt, and our sequences differed by 18–23 nucleotides compared with the reference sequence of B. acomydis (AB602553) (Supplementary Fig. S2).

The gltA sequence of the sample C from S. calurus (Table 2) showed 95–96% identity to the sequences from the G1 group (26 nucleotide differences), and displayed also the highest identity (90.85%) with B. acomydis from A. russatus from Egypt (15 nucleotide differences in relation to the B. acomydis reference sequence AB602553) (Table 4 and Supplementary Fig. S2).

The gltA sequence of the unique sample H (from D. dasyurus from W. Gharaba) was quite distinct from all other gltA sequences, displaying a low similarity of 93–96% to our sequences, with 28–41 nucleotide differences, and 93% identity to B. acomydis from A. russatus from Egypt with 14 nucleotide differences (Table 4 and Supplementary Fig. S2).

The phylogenetic analyses of the gltA sequences revealed four main groups (Fig. 3). The samples belonging to the abovementioned group G1 clustered together with samples C and H, and created a polyphyletic subgroup, which is distinct from all other representatives within this group. Interestingly, all Bartonella spp. in this group are from rodents originating from different regions of the world (Fig. 3), while all other main groups contain a range of Bartonella species from different hosts and every group contains at least one pathogenic Bartonella, distinct from our sequences.

Discussion

Molecular and phylogenetic analyses of the Bartonella spp. infecting Wagner's gerbil and the bushy-tailed jird from the Sinai Mountains revealed their distant relationships to all known species in this genus, and therefore, two novel species of Bartonella are proposed. Infections with the Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae n. sp. were found in two host species D. dasyurus and S. calurus, and Candidatus Bartonella sanaae n. sp. was found only in D. dasyurus. Morphologically there were no differences between the two novel species of Bartonella.

Our study has two pertinent limitations, the principal being a lack of conventional microbiological description based on cultured isolates; none of the samples in our study was maintained as an axenic isolate. However, our samples were collected from rodents trapped in remote sites in the deserts of the southern Sinai, and there was no possibility for initiating bacterial cultures in that setting. However, almost all known Bartonella species share very similar biochemical activity, as in other groups of organisms, for this genus also new species descriptions are mainly based on molecular data (Birtles et al. 1995, Gundi et al. 2004, Inoue et al. 2010, Mediannikov et al. 2013, Sato et al. 2013). Second, while the study could have benefitted from an multilocus sequence analysis, we were only able to use two genetic markers because our attempts to amplify several other genetic markers using published sets of primers were unsuccessful (16S rDNA, ribC, ftsZ (Paziewska et al. 2011) and gro EL (Zeaiter et al. 2002). Nevertheless, our study clearly emphasizes the genetic diversification of Egyptian Bartonella from the species/strains of Bartonella described and recognized from other regions of the world.

The rpoB and gltA genetic markers enable a clear discrimination of the known Bartonella species (Gundi et al. 2009). Molecular analyses of the rpoB sequences from this and previous studies (Inoue et al. 2009) have revealed that there are two variants of Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae n. sp.: one infecting two host species D. dasyurus and S. calurus, and the second one that has been identified so far in only one host species D. dasyurus (Fig. 2). All our rpoB variants of Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae n. sp were obtained from rodents trapped in one valley, W. Gebal in 2004 and 2012, which may suggest that it is an endemic population of Bartonella spp. In the case of Candidatus Bartonella sanaae n. sp., we also found two rpoB variants, both from the same host species (D. dasyurus) but from two isolated montane valleys, W. Gebal (2004) and W. Arbaein (2012) (Fig. 3).

It has been reported previously that the Bartonella isolates should be considered to represent a novel species, if the hypervariable 327 bp gltA gene fragment shares <96% sequence similarity and if an 825 bp rpoB fragment shares <95.4% sequence similarity with sequences from strains of species with validly published names (La Scola et al., 2003, Gundi et al., 2009). In the current study, we amplified and analyzed a near full-length (810 bp) fragment of the gltA gene with identity below 91% to B. florenciae, and an 860 bp long fragment of the rpoB gene with identity below 92% to B. florenciae. To check, if these differences were spread throughout the whole gene fragment, we analyzed and compared also genetic diversity among 190 bp of the hypervariable 327 bp gltA gene fragment extracted from our longer sequences and four reference sequences of Bartonella (Bartonella doshiae AF207827, B. grahamii Z70016, B. henselae L38987, and B. taylorii AF191502) from the GenBank database. The latter all contained the hypervariable 327 bp gltA gene fragment (La Scola et al. 2003, Gundi et al. 2009). Although the fragment that we compared was short (190 bp), sequence homology based on this region was only 90–95% (data not presented). Accordingly, these low similarity values for two genetic markers justify the description of two new species, supported also by phylogenetic analyses.

The similarity of our rpoB sequences with the human pathogenic B. elizabethae was only 88.30% in the case Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae n. sp. and 88.62% for Candidatus Bartonella sanaae n. sp. Moreover, analyses of our gltA sequences showed a similarity of 88.46% for Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae n. sp. with the pathogenic B. henselae and 88.80% similarity between Candidatus Bartonella sanaae n. sp. and B. henselae. Thus, any possible pathogenic consequences of infection with these new species cannot be currently assessed. Two pathogenic Bartonella spp. from humans in Africa are known to exist, B. henselae from Namibia (Noden et al. 2014) and B. quintana from Senegal (Diatta et al. 2014). Both these pathogenic Bartonella species have been reported also in South Africa with a high prevalence of up to 23% in people with HIV (Trataris-Rebisz 2012).

Our phylogenetic analyses of the rpoB sequences revealed four main genetic groups. In the first, the Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae n. sp. and Bartonella sanaae n. sp. sequences cluster with an unnamed Bartonella spp. from S. calurus from Egypt (Inoue et al. 2009), comprising a polyphyletic group/clade, supported by high bootstrap values, and a separate group/clade of other Bartonella sp. sequences from different regions of the world and derived from different hosts. This phylogenetic tree for rpoB sequences clearly highlights the difference between our sequences belonging to groups R1 and R2, and shows that these groups are separate from all other named Bartonella spp. With the exception of only one sequence of the pathogenic B. elizabethae, isolated from a human heart (Daly et al. 1993), all other Bartonella spp. sequences from this group/clade are derived from rodents.

Our phylogenetic analyses of gltA sequences also revealed four groups, the first comprising our Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae n. sp. and Candidatus Bartonella sanaae n. sp., with one sequence from D. dasyurus (sample H) from Egypt. This group clusters with B. florenciae from the greater white-toothed shrew C. russula from France and one unnamed Bartonella sp.; otherwise, this group contains different species of Bartonella from rodents from different regions of Europe.

The topology of the gltA tree differs from the rpoB tree primarily because of sample B, which belongs to group R2 of Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae n. sp. and is closely related to group G1 of Candidatus Bartonella sanaae n. sp. As reported previously by Paziewska et al. (2011), diversity in the gltA gene is highly associated with host specificity. Both samples in group G1 are from the same host species D. dasyurus and that is most likely the reason for sample B from D. dasyurus, identified as Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae n. sp, ending up so close to group G1 of Candidatus Bartonella sanaae n. sp. and why sample C from S. calurus identified as Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae n. sp. is separated from group G1 on this tree. This difference between samples B and C in the gltA gene sequence reflects also the difference that is apparent in the rpoB tree between the two variants of Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae n. sp.

An alternative interpretation of the differences between the two phylogenetic trees may be the possibility that horizontal gene transfer has occurred in the vector (flea), as reported in Paziewska et al. (2011). There is no recognized vector specificity for Bartonella spp. (Jusko 2015), and therefore, a horizontal gene transfer of the gltA gene is theoretically possible if a flea happens to be coinfected concurrently by two different species of Bartonella sp. from different hosts. As all the most similar gltA sequences (G1) originated from only one valley (W. Gebal), the possibility of a horizontal gene transfer of this marker cannot be excluded. Unfortunately, no other gltA sequences from the same or related host species are available from the GenBank database for comparison, in contrast to the rpoB gene, for which several sequences from S. calurus from Egypt have been deposited by Inoue et al. (2009) and are very similar to our sequences (although the exact region of origin in Egypt is not provided—the Bartonella strains in this study were isolated from rodents imported to Japan from Egypt, as pets). For these reasons, we consider the results of our phylogenetic analysis based on rpoB sequences to be more reliable, and based on this analysis, we have classified sample B from D. dasyurus as Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae n. sp.

Conclusions

Molecular and phylogenetic analyses of Bartonella samples from rodents from the Sinai Massif of Egypt have led to the description of two new species: Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae n. sp. and Candidatus Bartonella sanaae n. sp. The identification of their vectors, full microbiological assessment, and the medical significance of these species require further investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Etymology: the Candidatus Bartonella fadhilae n. sp. is named after the engineer Fadhil Naqi (the father of the first author of this study, M.A.), who was a fatal victim of terrorism in Iraq in 2005. The Candidatus Bartonella sanaae n. sp. is named after the dentist Sanaa Shukur (the mother of the first author of this study, M.A.), who took care of the family following loss their father. This study was funded by the National Science Center (NCN), Poland, grant OPUS 2011/03/B/NZ6/02090 (2012–2015) (to A.B.) and by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education through the Faculty of Biology, University of Warsaw intramural grant DSM number 140000/501/86-110101 (2014/2015) (to M.A.).

Authors' Contributions

A.B. designed the study and supervised laboratory and field analyses, M.A., R.W.F., and L.D. performed molecular and phylogenetic studies, M.B. participated in biological characterization of novel Bartonella spp., F.G. and S.Z. organized and supervised field work in Sinai, E.J.M., J.B.B., E.M.M., and J.M.B. carried out the laboratory and field studies and contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Alsarraf M. Ecology and Genetic Diversity of Blood Parasites in Bank Vole (Myodes glareolus) in the Masurian Lake District. MSc Research Thesis. Warsaw, Poland: Unversity of Warsaw, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Alsarraf M, Bednarska M, Mohallal EM, Mierzejewska EJ, et al. Long-term spatiotemporal stability and dynamic changes in the haemoparasite community of spiny mice (Acomys dimidiatus) in four montane wadis in the St. Katherine Protectorate, Sinai, Egypt. Parasit Vectors 2016; 9:195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajer A, Alsarraf M, Bednarska M, Mohallal EM, et al. Babesia behnkei sp. nov., a novel Babesia species infecting isolated populations of Wagner's gerbil, Dipodillus dasyurus, from the Sinai Mountains, Egypt. Parasit Vectors 2014a; 7:572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajer A, Harris PD, Behnke JM, Bednarska M, et al. Local variation of haemoparasites and arthropod vectors, and intestinal protozoans in spiny mice (Acomys dimidiatus) from four montane wadis in the St Katherine Protectorate, Sinai, Egypt. J Zool 2006; 270:9–24 [Google Scholar]

- Bajer A, Welc-Faleciak R, Bednarska M, Alsarraf M, et al. Long-term spatiotemporal stability and dynamic changes in the haemoparasite community of bank voles (Myodes glareolus) in NE Poland. Microb Ecol 2014b; 68:196–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke JM, Barnard CJ, Mason N, Harris PD, et al. Intestinal helminths of spiny mice (Acomys cahirinus dimidiatus) from St Katherine's Protectorate in the Sinai, Egypt. J Helminthol 2000; 74:31–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke JM, Harris PD, Bajer A, Barnard CJ, et al. Variation in the helminth community structure in spiny mice (Acomys dimidiatus) from four montane wadis in the St Katherine region of the Sinai Peninsula in Egypt. Parasitology 2004; 129:379–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birtles RJ. Bartonellae as elegant hemotropic parasites. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2005; 1063:270–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birtles RJ, Harrison TG, Saunders NA, Molyneux DH. Proposals to unify the genera Grahamella and Bartonella, with descriptions of Bartonella talpae comb. nov., Bartonella peromysci comb. nov., and three new species, Bartonella grahamii sp. nov., Bartonella taylorii sp. nov., and Bartonella doshiae sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1995; 45:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birtles RJ, Raoult D. Comparison of partial citrate synthase gene (gltA) sequences for phylogenetic analysis of Bartonella species. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1996; 46:891–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bown KJ, Bennet M, Begon M. Flea-borne Bartonella grahamii and Bartonella taylorii in bank voles. Emerg Infect Dis 2004; 10:684–687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffet JP, Kosoy M, Vayssier-Taussat M. Natural history of Bartonella-infecting rodents in light of new knowledge on genomics, diversity and evolution. Future Microbiol 2013; 8:1117–1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomel BB, Kasten RW, Floyd-Hawkins K, Chi B, et al. Experimental transmission of Bartonella henselae by the cat flea. J Clin Microbiol 1996; 34:1952–1956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly JS, Worthington MG, Brenner DJ, Moss CW, et al. Rochalimaea elizabethae sp. nov. isolated from a patient with endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol 1993; 31:872–881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diatta G, Mediannikov O, Sokhna C, Bassene H, et al. Prevalence of Bartonella quintana in patients with fever and head lice from rural areas of Sine-Saloum, Senegal. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2014; 91:291–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundi VA, Davoust B, Khamis A, Boni M, et al. Isolation of Bartonella rattimassiliensis sp. nov. and Bartonella phoceensis sp. nov. from European Rattus norvegicus. J Clin Microbiol 2004; 42:3816–3818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundi VA, Taylor C, Raoult D, La Scola B. Bartonella rattaustraliani sp. nov., Bartonella queenslandensis sp. nov. and Bartonella coopersplainsensis sp. nov., identified in Australian rats. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2009; 59:2956–2961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller R, Riegel P, Hansmann Y, Delacour G, et al. Bartonella tribocorum sp. nov., a new Bartonella species isolated from the blood of wild rats. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1998; 48 Pt 4:1333–1339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K, Kabeya H, Shiratori H, Ueda K, et al. Bartonella japonica sp. nov. and Bartonella silvatica sp. nov., isolated from Apodemus mice. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2010; 60:759–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K, Maruyama S, Kabeya H, Hagiya K, et al. Exotic small mammals as potential reservoirs of zoonotic Bartonella spp. Emerg Infect Dis 2009; 15:526–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K, Maruyama S, Kabeya H, Yamada N, et al. Prevalence and genetic diversity of Bartonella species isolated from wild rodents in Japan. Appl Environ Microbiol 2008; 74:5086–5092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jusko M. Flea Community and Their Role as Vectors of Bacteria Bartonella sp. in Three Sympatric Populations of Voles from the Mazury Lake District. MSc Research Thesis. Warsaw, Poland: University of Warsaw, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Kosoy M, Morway C, Sheff KW, Bai Y, et al. Bartonella tamiae sp. nov., a newly recognized pathogen isolated from three human patients from Thailand. J Clin Microbiol 2008; 46:772–775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosoy M, Murray M, Gilmore RD, Jr., Bai Y, et al. Bartonella strains from ground squirrels are identical to Bartonella washoensis isolated from a human patient. J Clin Microbiol 2003; 41:645–650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosoy MY, Regnery RL, Tzianabos T, Marston EL, et al. Distribution, diversity, and host specificity of Bartonella in rodents from the Southeastern United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1997; 57:578–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Scola B, Zeaiter Z, Khamis A, Raoult D. Gene-sequence-based criteria for species definition in bacteriology: The Bartonella paradigm. Trends Microbiol 2003; 11:318–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JW, Chen CY, Chen WC, Chomel BB, et al. Isolation of Bartonella species from rodents in Taiwan including a strain closely related to ‘Bartonella rochalimae’ from Rattus norvegicus. J Med Microbiol 2008; 57:1496–1501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mediannikov O, El Karkouri K, Robert C, Fournier PE, et al. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Bartonella florenciae sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2013; 9:185–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mediannikov O, Ivanov L, Zdanovskaya N, Vysochina N, et al. Molecular screening of Bartonella species in rodents from the Russian Far East. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2005; 1063:308–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morick D, Krasnov BR, Khokhlova IS, Gottlieb Y, et al. Investigation of Bartonella acquisition and transmission in Xenopsylla ramesis fleas (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). Mol Ecol 2011; 20:2864–2870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noden BH, Tshavuka FI, van der Colf BE, Chipare I, et al. Exposure and risk factors to coxiella burnetii, spotted fever group and typhus group Rickettsiae, and Bartonella henselae among volunteer blood donors in Namibia. PLoS One 2014; 9:e108674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi H, Battistini TS. Etiology of Oroya fever: I. Cultivation of Bartonella bacilliformis. J Exp Med 1926; 43:851–864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman AF, Regnery R, Jameson P, Greene C, et al. Differentiation of Bartonella-like isolates at the species level by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism in the citrate synthase gene. J Clin Microbiol 1995; 33:1797–1803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paziewska A, Harris PD, Zwolinska L, Bajer A, et al. Recombination within and between species of the alpha proteobacterium Bartonella infecting rodents. Microb Ecol 2011; 61:134–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renesto P, Gouvernet J, Drancourt M, Roux V, et al. Use of rpoB gene analysis for detection and identification of Bartonella species. J Clin Microbiol 2001; 39:430–437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato S, Kabeya H, Fujinaga Y, Inoue K, et al. Bartonella jaculi sp. nov., Bartonella callosciuri sp. nov., Bartonella pachyuromydis sp. nov. and Bartonella acomydis sp. nov., isolated from wild Rodentia. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2013; 63;1734–1740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift HF. Trench fever. Arch Intern Med 1920; 26;76–98 [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol 2013; 30:2725–2729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tea A, Alexiou-Daniel S, Papoutsi A, Papa A, et al. Bartonella species isolated from rodents, Greece. Emerg Infect Dis 2004; 10:963–964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trataris-Rebisz AN, Arntzen L, Rossouw J, Karstaedt A, Frean J. Bartonella henselae and Bartonella quintana’ seroprevalence in HIV-positive, HIV-negative and clinically healthy volunteers in gauteng province, South Africa. Annals of the ACTM: An International Journal of Tropical and Travel Medicine 2012; 13:10–12 [Google Scholar]

- Vayssier-Taussat M, Moutailler S, Femenia F, Raymond P, et al. Identification of novel zoonotic activity of Bartonella spp., France. Emerg Infect Dis 2016; 22:457–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos P, Garrity G, Jones D, Krieg NR, Ludwig W, et al. Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, vol. Springer Science & Business Media. New York: Springer, 2009: 21–128 [Google Scholar]

- Welc-Faleciak R, Bajer A, Behnke JM, Sinski E. The ecology of Bartonella spp. infections in two rodent communities in the Mazury Lake District region of Poland. Parasitology 2010; 137:1069–1077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch DF, Carroll KC, Hofmeister EK, Persing DH, et al. Isolation of a new subspecies, Bartonella vinsonii subsp. arupensis, from a cattle rancher: Identity with isolates found in conjunction with Borrelia burgdorferi and Babesia microti among naturally infected mice. J Clin Microbiol 1999; 37:2598–2601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winoto IL, Goethert H, Ibrahim IN, Yuniherlina I, et al. Bartonella species in rodents and shrews in the greater Jakarta area. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2005; 36;1523–1529 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying B, Kosoy MY, Maupin GO, Tsuchiya KR, et al. Genetic and ecologic characteristics of Bartonella communities in rodents in southern China. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2002; 66:622–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.