Abstract

Background: The 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter, phase 3 REJOICE trial demonstrated that TX-004HR, an investigational, applicator-free, low-dose vaginal softgel capsule containing solubilized 17β-estradiol, effectively and rapidly treats symptoms of vulvar and vaginal atrophy (VVA) with negligible to very low systemic absorption. The aim of this analysis was to assess whether the efficacy of TX-004HR varies with age, body mass index (BMI), uterine status, pregnancy status, and vaginal delivery.

Methods: The REJOICE trial evaluated the efficacy of 4-, 10-, and 25-μg doses of TX-004HR in postmenopausal women (40–75 years) with VVA and a self-identified most bothersome symptom of moderate-to-severe dyspareunia. Prespecified subgroup analyses of the four co-primary endpoints (percentages of superficial cells and parabasal cells, vaginal pH, and severity of dyspareunia) were analyzed with respect to age, BMI, uterine status, pregnancy status, and vaginal births. Each dose was compared with placebo for change from baseline to week 2 through week 12, respectively.

Results: TX-004HR significantly improved superficial cells, parabasal cells, and vaginal pH from baseline to weeks 2 and 12 in most subgroups. All TX-004HR doses numerically reduced the severity of dyspareunia by 2 weeks and maintained efficacy over 12 weeks, with many of the subgroups having statistically significant improvement relative to placebo.

Conclusions: TX-004HR was efficacious for treating symptomatic VVA, and it demonstrated a consistency of effect when women's age, BMI, uterine status, pregnancy status, and vaginal births were evaluated. Clinical Trial Identifier: NCT02253173.

Keywords: : age, body mass index, dyspareunia, vaginal atrophy, 17-β estradiol

Introduction

Vulvar and vaginal atrophy (VVA), resulting from estrogen loss, is characterized by the thinning, drying, and loss of elasticity of the vaginal epithelium.1 A component of genitourinary syndrome of menopause,2 VVA is a chronic, progressive condition that clinically manifests as vaginal dryness, irritation, dysuria, and pain (dyspareunia) or bleeding with sexual activity.3 VVA, unlike vasomotor symptoms, is progressive and not likely to resolve without treatment.4

TX-004HR (TherapeuticsMD, Inc., Boca Raton, FL) is an investigational, applicator-free, muco-adhesive, vaginal, softgel capsule containing low-dose solubilized 17β-estradiol that is designed to provide relief from postmenopausal symptoms of VVA. The randomized, double-blind, phase 3 REJOICE trial recently demonstrated that TX-004HR at doses of 4, 10, and 25 μg significantly improved the percentages of superficial cells by 17% to 23% versus 6% with placebo, parabasal cells by 41% to 46% versus 7%, vaginal pH by 1.3 to 1.4 versus 0.3, and severity of dyspareunia by 1.5 to 1.7 versus 1.3 in postmenopausal women with VVA after 12 weeks of treatment.5 Significant improvements were observed as early as 2 weeks of treatment,5 and with negligible to very low systemic absorption of estradiol.6 All three doses also significantly reduced the severity of vaginal dryness and, with the exception of the 4 μg dose, vulvar and/or vaginal itching/irritation when compared with placebo at 12 weeks.5

Demographic factors, such as age and parity, may affect the severity of VVA and the response to therapy; however, published data on such effects are limited. The relationship of age and body mass index (BMI) with circulating estrogens has been reported in postmenopausal women; estrogen levels decrease with advancing age and increase with increasing BMI.7 Thus, the severity of VVA would be expected to increase with age and decrease with increasing BMI. The reported association between VVA and BMI has shown that women with an atrophic cell pattern were significantly more likely to have low BMI compared with those with a mature cell pattern.8 An analysis of vaginal symptoms reported by postmenopausal women participating in the 2-year Prospective Evaluation of Postmenopausal Cystitis study also identified low BMI as a risk factor for dyspareunia.9

The objective of this analysis was to evaluate whether the clinical efficacy of TX-004HR for treating VVA (as measured by the percentages of superficial and parabasal cells, vaginal pH, and severity of dyspareunia in the REJOICE trial) is maintained regardless of women's age, BMI, uterine status, pregnancy history, and vaginal delivery.

Materials and Methods

Study design

The 12-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group REJOICE trial (NCT02253173) evaluated the clinical safety and efficacy of 4-, 10-, and 25-μg doses of TX-004HR in postmenopausal women diagnosed with VVA and having a self-reported most bothersome symptom (MBS) of moderate-to-severe dyspareunia. The study design for the REJOICE trial has been previously reported.5 Women were randomized 1:1:1:1 to 4-, 10-, and 25-μg TX-004HR or placebo.5 Women self-administered 1 capsule per day intravaginally for 2 weeks, followed by bi-weekly dosing (3 to 4 days apart) for 10 weeks.5 Changes from baseline to week 12 in the percentages of superficial cells and parabasal cells, vaginal pH, and severity of the patient-reported MBS of moderate-to-severe dyspareunia were measured as co-primary endpoints.5 Secondary outcome measures included change from baseline to week 2, 6, and 8 in the same endpoints, as well as vaginal dryness and vulvar and/or vaginal itching or irritation.5 Patients self-identified their MBS by using a 4-point scale, where a score of 3 = severe, 2 = moderate, 1 = mild, and 0 = none.

The REJOICE trial was designed, conducted, and monitored in accordance with the study protocol, Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and the principles specified in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at all the participating centers. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Study population

Postmenopausal women (age, 40–75 years; BMI, ≤38 kg/m2) with ≤5% superficial cells on vaginal cytological smear, vaginal pH >5.0, and a MBS of moderate-to-severe dyspareunia due to menopause were included in this study. In addition, women were to be sexually active (with vaginal penetration) and anticipate sexual activity during the trial period. Postmenopausal women with an intact uterus were required to have an acceptable result from an endometrial biopsy conducted at screening.

Women were not permitted to use an oral estrogen-, progestin-, androgen-, or selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM)-containing product within 8 weeks; transdermal hormones within 4 weeks; vaginal hormones (rings, creams, gels) within 4 weeks; intrauterine progestins within 8 weeks; progestin implants/injectables or estrogen pellets/injectables within 6 months; vaginal lubricants or moisturizers within 7 days before vaginal pH assessment during screening; investigational drugs within 60 days; or an intrauterine device within 12 weeks before screening. Use of concomitant medications was allowed and recorded in patient diaries; however, use of investigational drugs other than TX-004HR; estrogen-, progestin-, androgen-containing medications, or SERMs; and prescription- and nonprescription medications/remedies for VVA (including vaginal lubricants and moisturizers) was not permitted.

Statistical analyses

The REJOICE trial was sufficiently powered to compare mean change from baseline to week 12, with each TX-004HR dose versus placebo for each of the four co-primary endpoints. Descriptive analyses were the most suitable for subgroup analyses, because the study was not powered to evaluate the smaller subgroups for the prespecified secondary analyses. Changes from baseline to weeks 2, 6, 8, and 12 in the percentages of superficial and parabasal cells, vaginal pH, and severity of dyspareunia for each TX-004HR dose versus placebo were compared within the following subgroups: age (≤56, 57 to 61, and ≥62 years), BMI (≤24, 25 to 28, and ≥29 kg/m2), uterine status (intact uterus or no intact uterus), pregnancy history (n = 0 or n ≥ 1), and the number of vaginal births in women who reported pregnancy (vaginal birth = 0 or vaginal births ≥1). Mixed model repeated measures (MMRM) was used to compare each TX-004HR dose with placebo. The MMRM was based on postbaseline visits and used baseline and age as covariates with random intercept.

Results

Patient disposition and demographics at baseline

A total of 764 women satisfied the REJOICE study inclusion/exclusion criteria and were randomized to TX-004HR 4 μg (n = 191), 10 μg (n = 191), 25 μg (n = 190), or placebo (n = 192). The study was completed by 704 women (92%). Most women were white, had a mean age of 59 years, a mean BMI of 27 kg/m2, and a mean time since menopause of 14 years (Table 1). Demographics and baseline characteristics of the modified intent-to-treat (MITT) population were comparable between the four treatment groups.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics and Baseline Characteristics (MITT Population)

| TX-004HR 4 μg | TX-004HR 10 μg | TX-004HR 25 μg | Placebo | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 186 | 188 | 186 | 187 |

| Age, years | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 59.8 ± 6.0 | 58.6 ± 6.3 | 58.8 ± 6.2 | 59.4 ± 6.0 |

| Range | 41–75 | 42–75 | 40–74 | 43–73 |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White | 162 (87.1) | 165 (87.8) | 161 (86.6) | 160 (85.6) |

| Black or African American | 20 (10.8) | 21 (11.2) | 24 (12.9) | 21 (11.2) |

| Asian | 3 (1.6) | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 26.6 ± 4.9 | 26.8 ± 4.7 | 26.8 ± 4.8 | 26.6 ± 4.6 |

| Range | 18–38 | 18–37 | 17–38 | 18–38 |

| Time since menopause, years | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 14.2 ± 8.9 | 14.3 ± 9.4 | 13.8 ± 9.4 | 13.9 ± 9.4 |

| Range | 1–42 | 1–46 | 1–43 | 1–45 |

| Superficial cells, % | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 1.3 ± 1.2 | 1.2 ± 1.2 | 1.3 ± 1.2 | 1.3 ± 1.3 |

| Parabasal cells, % | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 52.3 ± 39.2 | 51.3 ± 38.0 | 53.5 ± 38.3 | 52.0 ± 39.2 |

| Vaginal pH | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 6.3 ± 0.9 | 6.3 ± 0.8 | 6.3 ± 0.9 | 6.3 ± 1.0 |

| Dyspareunia, severity score | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 2.7 ± 0.5 |

BMI, body mass index; MITT, modified intent-to-treat; SD, standard deviation.

The percentage of parabasal cells (p < 0.0001) and vaginal pH (p = 0.0018) at baseline varied significantly between the age subgroups, with both being greater among women aged ≥62 years (60.3% and 6.43%, respectively) relative to the youngest group (43.1% and 6.16%, respectively). Similar significant baseline differences in percentage of parabasal cells (p < 0.0001) and vaginal pH (p = 0.0018) were also seen among women when analyzed by BMI, with the lowest BMI group (≤24 kg/m2) having the highest percentage of parabasal cells (62.3%) and vaginal pH (6.42) and the highest BMI group having the lowest of these parameters (37.4% and 6.16%, respectively).

Changes in the co-primary endpoints from baseline to weeks 2 and 12 are discussed later; data for subgroup analyses conducted at weeks 6 and 8 (data not shown) follow trends that are similar to what were seen for weeks 2 and 12.

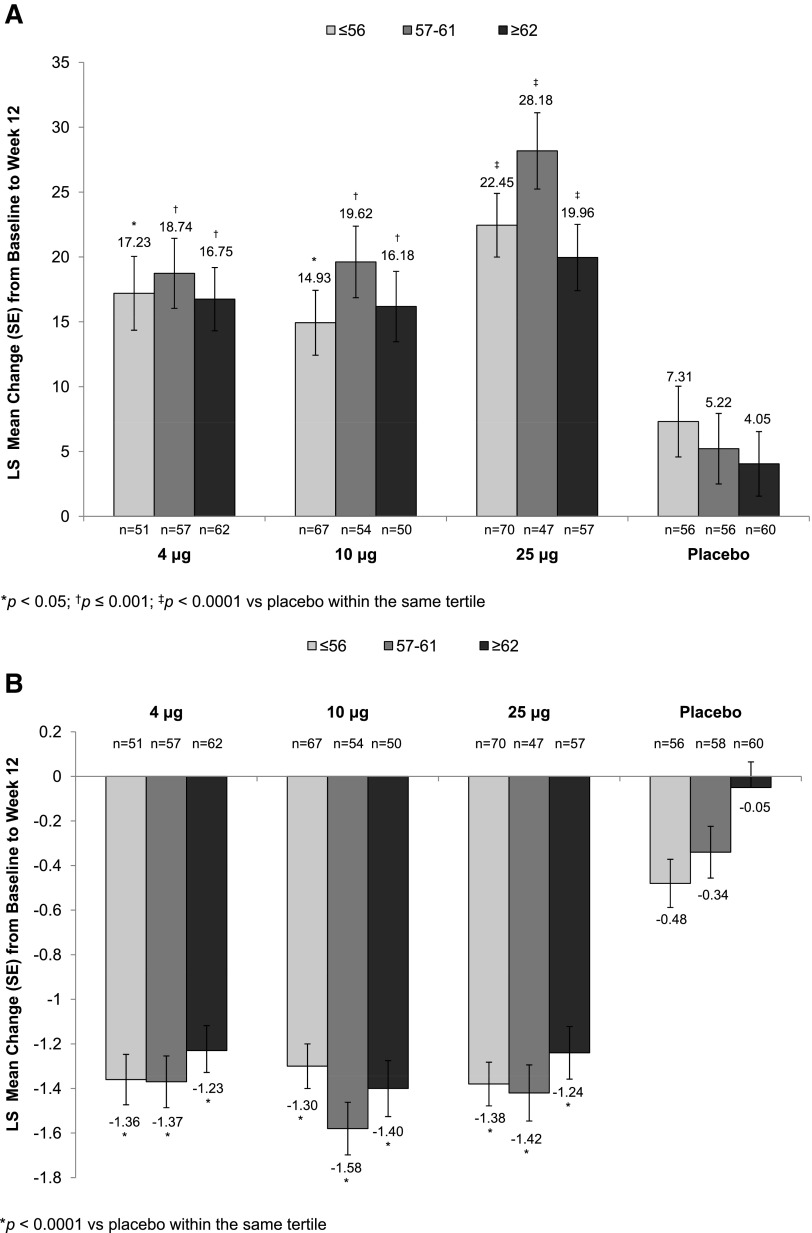

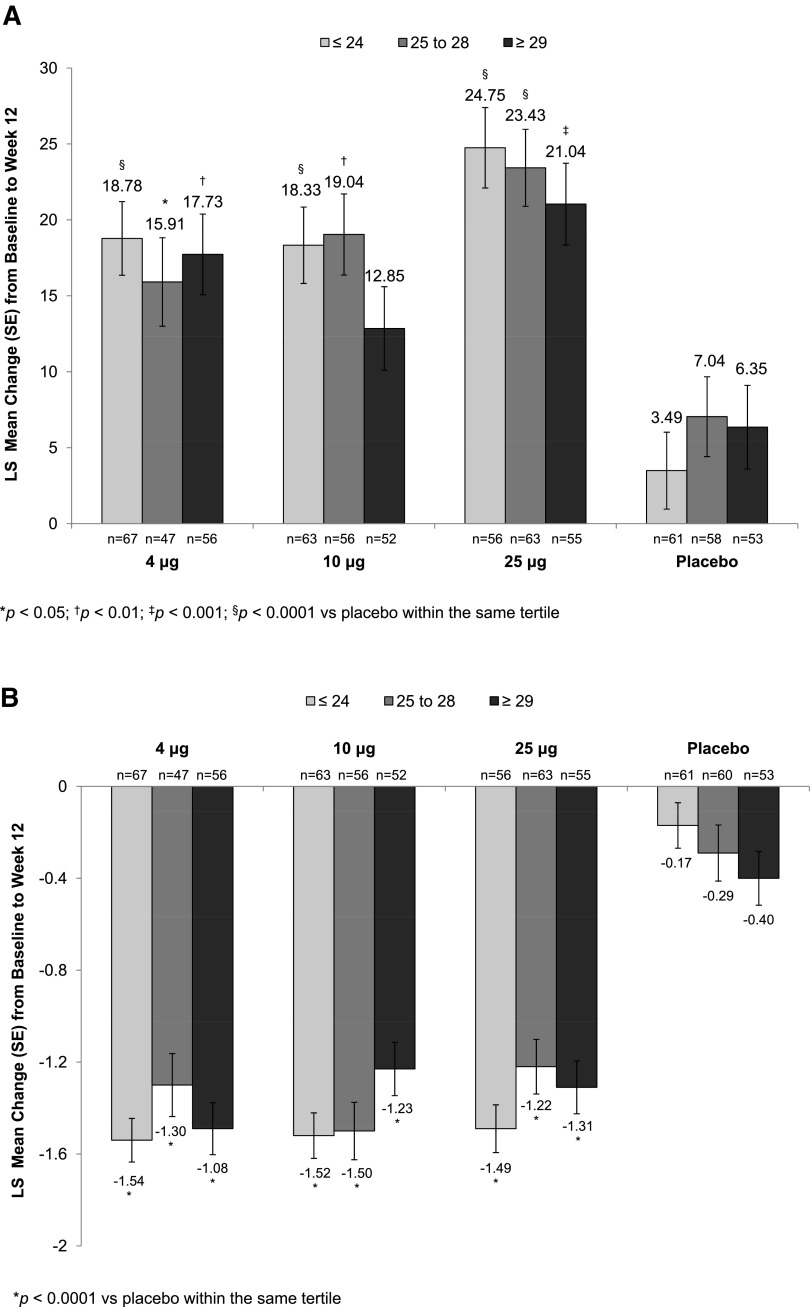

Age

All three TX-004HR doses, when compared with placebo, significantly increased the percentage of superficial cells from baseline to week 2 (Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/jwh) and week 12 (Fig. 1A), regardless of age. Similarly, significant reductions in the percentage of parabasal cells (data not shown) and vaginal pH from baseline to week 2 (Supplementary Table S2) and week 12 (Fig. 1B) were seen in all age subgroups. TX-004HR-treated women of all ages reported a reduction in the severity of dyspareunia from baseline to week 2 (Supplementary Table S3) and week 12 (Fig. 1C), with some age subgroups having significant greater improvement compared with placebo over the 12-week study period (Supplementary Table S3).

FIG. 1.

Least square (LS) mean change from baseline to week 12 in (A) percentage of superficial cells, (B) vaginal pH, and (C) dyspareunia by age tertile.

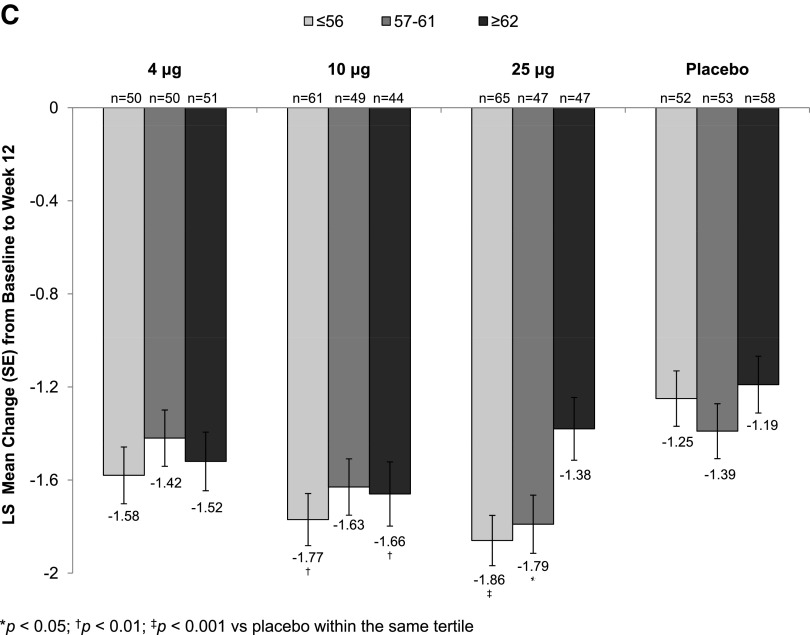

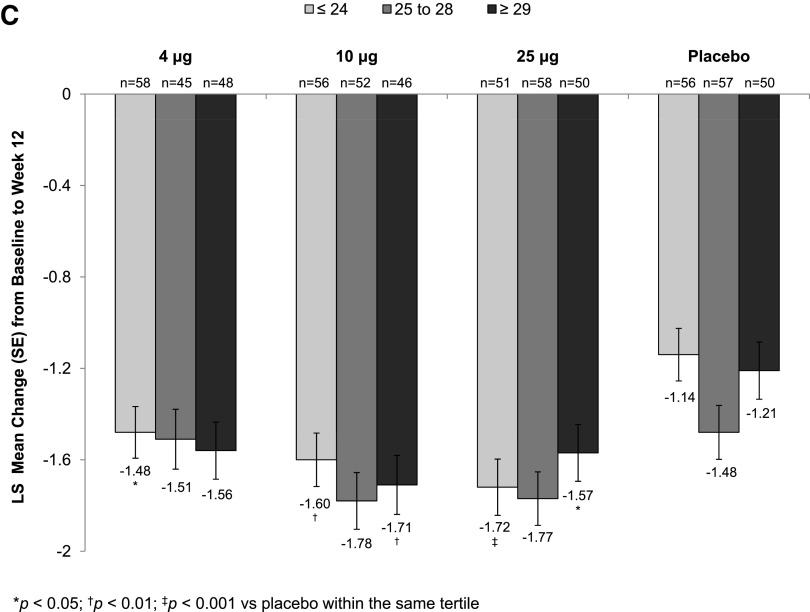

Body mass index

Statistically significant increases in the percentage of superficial cells from baseline to week 2 (Supplementary Table S1) were seen with all TX-004HR doses versus placebo, irrespective of BMI. These improvements were maintained over the 12-week period for all BMI subgroups except for the 10 μg TX-004HR-treated women with BMI ≥29 kg/m2 (Fig. 2A). All three TX-004HR doses significantly reduced the percentage of parabasal cells (data not shown) and vaginal pH from baseline to week 2 (Supplementary Table S2) and week 12 (Fig. 2B) in all subgroups. TX-004HR 4, 10, and 25 μg also reduced the severity of dyspareunia from baseline to week 2 (Supplementary Table S3) and week 12 (Fig. 2C) in all women, with some subgroups achieving statistical significance relative to placebo.

FIG. 2.

LS mean change from baseline to week 12 in (A) percentage of superficial cells, (B) vaginal pH, and (C) dyspareunia by BMI tertile. BMI, body mass index.

Uterine status

TX-004HR 4, 10, and 25 μg significantly improved the percentages of superficial (Supplementary Table S1) and parabasal cells (data not shown) and vaginal pH (Supplementary Table S2) from baseline to weeks 2 and 12, regardless of uterine status. All three TX-004HR doses reduced the severity of dyspareunia from baseline to weeks 2 and 12 in women with and without an intact uterus, with most subgroups having a significantly greater improvement over placebo (Supplementary Table S3).

Pregnancy history

Statistically significant increases in the percentage of superficial cells from baseline were seen with all TX-004HR doses versus placebo at 2 weeks and, with exception of the 10 μg TX-004HR-treated women with no prior pregnancy, they were maintained over the 12 weeks (Supplementary Table S1). TX-004HR doses, when compared with placebo, significantly reduced the percentage of parabasal cells (data not shown) and vaginal pH (Supplementary Table S2) from baseline to weeks 2 and 12, irrespective of pregnancy history. Women with and without a prior pregnancy also reported a numerical reduction in baseline severity of dyspareunia with all three TX-004HR doses at weeks 2 and 12, with many subgroups having a significantly greater improvement versus placebo (Supplementary Table S3).

Vaginal births

Among women who reported a prior pregnancy, TX-004HR 4, 10, and 25 μg significantly improved the percentages of superficial (Supplementary Table S1) and parabasal cells (data not shown) and vaginal pH (Supplementary Table S2) from baseline to weeks 2 and 12, regardless of vaginal birth status. TX-004HR 4, 10, and 25 μg also reduced the severity of dyspareunia from baseline to week 2 and maintained this reduction over the 12-week study period, with many subgroups having statistically significant improvements over placebo (Supplementary Table S3).

Discussion

Subgroup analyses of the REJOICE trial data revealed that TX-004HR, at doses of 4, 10, and 25 μg, had a robust, consistent, and positive effect on vaginal physiology and severity of dyspareunia in postmenopausal women with VVA, regardless of their age, BMI, uterine status, pregnancy history, and vaginal birth status. All three TX-004HR doses significantly improved the percentages of superficial and parabasal cells and vaginal pH at week 2 and for the most part, they maintained this improvement across all subgroups over the 12-week study period. The three TX-004HR doses also reduced the severity of dyspareunia, with many subgroups achieving statistical significance relative to placebo.

The data from these subanalyses also support previous reports of the progressive nature of VVA, with women older in age having more severe VVA. Consistent with an increasing severity of VVA with age, our data show that women in the oldest age group had the highest percentage of parabasal cells and vaginal pH. These data from the REJOICE trial also support the previously described association of lower BMI and lower estrogen levels with more severe VVA. At baseline, the percentage of parabasal cells and vaginal pH varied significantly between BMI subgroups. Of the BMI subgroups, women with the lowest BMI (≤24 kg/m2) had the highest percentage of parabasal cells and vaginal pH. Both of these trends are consistent with the expected relative levels of endogenous estrogens in these subgroups based on age and body fat.

The results of this phase 3 trial demonstrate the consistency of TX-004HR's effect on the vaginal health of postmenopausal women. All three TX-004HR doses significantly improved the vaginal physiology, despite the observed differences in baseline severity among women based on age and BMI. TX-004HR, at doses of 4, 10, and 25 μg, elicited and maintained a therapeutic response in postmenopausal women, regardless of their uterine status or pregnancy history. Similarly, TX-004HR also improved the vaginal health in women who had never given birth vaginally, a subset of women who were believed to have more pronounced and difficult-to-treat vaginal atrophy. All three doses of TX-004HR also had a consistently positive effect on the severity of dyspareunia across all subgroups. The association between age and severity of dyspareunia (a primary endpoint of the REJOICE trial) is unknown; however, it is expected to worsen due to declining estrogen levels and vaginal health. It is believed that younger women are more likely to report dyspareunia, as they tend to be more sexually active than older women10; however, studies have reported mixed results, with dyspareunia increasing,11,12 decreasing,9,10,13–15 or fluctuating16 with age. Regardless of this, TX-004HR provided symptomatic relief from dyspareunia to all women regardless of their age.

As with age, the association between BMI and dyspareunia is poorly understood, with one study reporting low BMI as a risk factor for dyspareunia.9 In this analysis, improvements in the severity of dyspareunia varied among TX-004HR-treated BMI subgroups. For instance, all three doses of TX-004HR significantly reduced the severity of dyspareunia among women with low BMI after a 12-week treatment. However, in women with higher BMIs (>29 kg/m2), statistically significant improvements in dyspareunia were only achieved with the 10 and 25 μg doses. Since TX-004HR has a local effect with negligible to very low systemic absorption,6 the reason for this difference is unknown, but as shown in this trial, women with higher BMIs had less severe atrophy as noted by vaginal pH and cytology at baseline, and perhaps their VVA symptoms were less severe than those with lower BMI during the conduct of the trial. Higher doses of TX-004HR may be needed to achieve a statistically significant change versus placebo for women with higher BMI and less severe atrophy if they have higher endogenous estrogen levels.

The clinical literature characterizing the association between postmenopausal dyspareunia and uterine status, pregnancy history, or child delivery is currently lacking. Prior pregnancy may affect the severity of dyspareunia, as loss of vulvar elasticity may be greater among women who have never been pregnant. Data from our analysis demonstrated that all three doses of TX-004HR had a positive effect among all women, regardless of their uterine status or pregnancy history.

Although the REJOICE trial was sufficiently powered to compare differences in the four primary co-endpoints between treatment arms and placebo in the total population, the study was not powered for evaluating those endpoints among smaller subgroups. Thus, even though magnitudes of improvement for dyspareunia severity were similar among subgroups, statistical significance may have not been observed in all subgroups due to their small sample sizes. Relatively small sample sizes are sufficient for assessing objective measures of VVA,17 whereas larger sample sizes are needed to accurately assess changes in highly subjective measures, such as the severity of dyspareunia. Larger sample sizes, particularly for the dyspareunia endpoint, may be necessary, since vaginal atrophy and severity of VVA symptoms at baseline can vary greatly between subgroups (particularly for those based on age or BMI) due to differences in estrogen levels. In addition, a larger sample size may be needed, as a greater placebo response may be expected due to the use of Miglyol, a fractionated coconut oil with potential lubricative properties, in the formulation of placebo and TX-004HR capsules.18 Another limitation is the fact that most of the women enrolled in the REJOICE study were white and nonobese, and the results of the study may not be generally applicable to the overall U.S. population. Regardless of this, the efficacy in these subgroup analyses was consistent with the onset of action observed at 2 weeks reported for the total population and maintained over the 12-week study period.5

The data from these subgroup analyses further extend the primary efficacy data by descriptively demonstrating that TX-004HR has a positive, beneficial clinical effect in postmenopausal women with VVA and moderate-to-severe dyspareunia, independent of their baseline characteristics. Furthermore, TX-004HR limits estrogen exposure to the vagina.6 In addition, although not compared in head-to-head trials, lower doses of estrogens have been associated with fewer adverse events. Local vaginal therapies are considered to have lower adverse event profiles than other commonly used systemic estrogen therapies,4 such as decreased risk of endometrial stimulation, breast tenderness, hemostatic changes, and venous thromboembolism.4,19–21 Overall, no unexpected adverse events were observed with the low-dose softgel estradiol capsule, TX-004HR.5

Conclusion

This article investigated the effects of patient characteristics on the clinical efficacy of the vaginal estrogen therapy, TX-004HR, for postmenopausal VVA. TX-004HR at doses of 4, 10, and 25 μg significantly increased superficial cells and reduced vaginal pH, parabasal cells, and severity of dyspareunia for a maximum of 12 weeks, with age, BMI, uterine status, pregnancy history, and vaginal birth status having little to no influence. All three doses of TX-004HR have a consistently positive and robust effect on the vaginal physiology and severity of dyspareunia in postmenopausal women with VVA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank and acknowledge the contributions of the investigators who participated in data collection for the REJOICE Study, Harvey Kushner for statistical analyses, and Disha Patel, PhD of Precise Publications, LLC for the medical writing support, which was funded by TherapeuticsMD.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr. Constantine consults to multiple pharmaceutical companies, including, but not limited to, TherapeuticsMD and has stock options with TherapeuticsMD. Dr. Bouchard has received research grants from TherapeuticsMD, Merck Canada, GlaxoSmithKline, Bayer, and Endoceutics and an educational grant from Merck Canada. Dr. Pickar has received consultant fees from Wyeth/Pfizer, Radius Health Inc., Shionogi Inc., and TherapeuticsMD; and has stock options with TherapeuticsMD. Dr. Archer (within the past 3 years) has received research support from Actavis (previously Allergan, Watson Pharmaceuticals, Warner Chilcott), Bayer Healthcare, Endoceutics, Glenmark, Merck (previously Schering Plough, Organon), Radius Health Inc., Shionogi Inc., and TherapeuticsMD; and has served as a consultant to Abbvie (previously Abbott Laboratories), Actavis (previously Allergan, Watson Pharmaceuticals, Warner Chilcott), Agile Therapeutics, Bayer Healthcare, Endoceutics, Exeltis (previously CHEMO), InnovaGyn, Merck (previously Schering Plough, Organon), Pfizer, Radius Health Inc., Sermonix Pharmaceuticals, Shionogi Inc., Teva Women's Healthcare, and TherapeuticsMD. Dr. Bernick is a board member and an employee of TherapeuticsMD with stock/stock options. Dr. Graham and Dr. Mirkin are employees of TherapeuticsMD with stock/stock options.

References

- 1.Mac Bride MB, Rhodes DJ, Shuster LT. Vulvovaginal atrophy. Mayo Clin Proc 2010;85:87–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Portman DJ, Gass ML. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: New terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2014;21:1063–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lev-Sagie A. Vulvar and vaginal atrophy: Physiology, clinical presentation, and treatment considerations. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2015;58:476–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Management of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy: 2013 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2013;20:888–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Constantine G, Simon JA, Pickar JH, et al. The REJOICE trial: A phase 3 randomized, controlled trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of a novel vaginal estradiol softgel capsule for symptomatic vulvar and vaginal atrophy (VVA). Menopause. 2016. [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Archer DF, Constantine GD, Simon J, et al. TX-004HR vaginal estradiol has negligible to very low systemic absorption of estradiol. Menopause. 2016. [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lukanova A, Lundin E, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, et al. Body mass index, circulating levels of sex-steroid hormones, IGF-I and IGF-binding protein-3: A cross-sectional study in healthy women. Eur J Endocrinol 2004;150:161–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Repše-Fokter A, Takač I, Fokter SK. Postmenopausal vaginal atrophy correlates with decreased estradiol and body mass index and does not depend on the time since menopause. Gynecol Endocrinol 2008;24:399–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang AJ, Moore EE, Boyko EJ, et al. Vaginal symptoms in postmenopausal women: Self-reported severity, natural history, and risk factors. Menopause 2010;17:121–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: Prevalence and predictors. JAMA 1999;281:537–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osborn M, Hawton K, Gath D. Sexual dysfunction among middle aged women in the community. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1988;296:959–962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bachmann GA, Leiblum SR, Grill J. Brief sexual inquiry in gynecologic practice. Obstet Gynecol 1989;73:425–427 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Najman J, Dunne M, Boyle F, Cook M, Purdie D. Sexual dysfunction in the Australian population. Aust Fam Physician 2003;32:951–954 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barlow DH, Samsioe G, van Geelen JM. A study of European womens' experience of the problems of urogenital ageing and its management. Maturitas 1997;27:239–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barlow DH, Cardozo LD, Francis RM, et al. Urogenital ageing and its effect on sexual health in older British women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1997;104:87–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Geelen JM, van de Weijer PH, Arnolds HT. Urogenital symptoms and resulting discomfort in non-institutionalized Dutch women aged 50–75 years. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2000;11:9–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pickar JH, Amadio JM, Bernick BA, Mirkin S. Pharmacokinetic studies of solubilized estradiol given vaginally in a novel softgel capsule. Climacteric 2016;19:181–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kingsberg S, Derogatis L, Simon JA, et al. TX-004HR improves sexual function as measured by the female sexual function index in postmenopausal women with vulvovaginal vulvar and vaginal atrophy: The REJOICE Trial. J Sex Med 2016;13:1930–1937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bergendal A, Kieler H, Sundstrom A, Hirschberg AL, Kocoska-Maras L. Risk of venous thromboembolism associated with local and systemic use of hormone therapy in peri- and postmenopausal women and in relation to type and route of administration. Menopause 2016;23:593–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simon J, Nachtigall L, Ulrich LG, Eugster-Hausmann M, Gut R. Endometrial safety of ultra-low-dose estradiol vaginal tablets. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:876–883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krause M, Wheeler TL, 2nd, Snyder TE, Richter HE. Local effects of vaginally administered estrogen therapy: A review. J Pelvic Med Surg 2009;15:105–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.