Abstract

A major difference between two currently licensed anthrax vaccines is presence (United Kingdom Anthrax Vaccine Precipitated, AVP) or absence (United States Anthrax Vaccine Adsorbed, AVA) of quantifiable amounts of the Lethal Toxin (LT) component Lethal Factor (LF). The primary immunogen in both vaccine formulations is Protective Antigen (PA), and LT-neutralizing antibodies directed to PA are an accepted correlate of vaccine efficacy; however, vaccination studies in animal models have demonstrated that LF antibodies can be protective. In this report we compared humoral immune responses in cohorts of AVP (n=39) and AVA recipients (n=78) matched 1:2 for number of vaccinations and time post-vaccination, and evaluated whether the LF response contributes to LT neutralization in human recipients of AVP. PA response rates (≥95%) and PA IgG concentrations were similar in both groups; however, AVP recipients exhibited higher LT neutralization ED50 values (AVP: 1464.0 ± 214.7, AVA: 544.9 ± 83.2, p<0.0001) and had higher rates of LF IgG positivity (95%) compared to matched AVA vaccinees (1%). Multiple regression analysis revealed that LF IgG makes an independent and additive contribution to the LT neutralization response in the AVP group. Affinity purified LF antibodies from two independent AVP recipients neutralized LT and bound to LF Domain 1, confirming contribution of LF antibodies to LT neutralization. This study documents the benefit of including an LF component to PA-based anthrax vaccines.

Keywords: Bacillus anthracis, anthrax, Anthrax Vaccine Adsorbed, Anthrax Vaccine Precipitated, Lethal Factor, Protective Antigen, Lethal Toxin, neutralization

Introduction

Bacillus anthracis is a Gram positive, spore-forming rod that is the causative agent of anthrax. B. anthracis has two major, plasmid-encoded virulence factors, a poly-D-glutamic acid capsule and a secreted tripartite toxin [1]. The tripartite toxin is made up of Protective Antigen (PA), Lethal Factor (LF) and Edema Factor (EF) [2]. PA is an 83kD protein that acts as the common binding component for LF and EF. PA binds to one of the two major anthrax toxin receptors and forms a pore, allowing LF and EF access to the cytosol, where they exert their activities [3]. LF is a 90kD Zn2+-dependent metalloprotease that cleaves MAPKKs, while EF is an 89kD calmodulin-dependent adenylate cyclase that converts ATP to cAMP [4, 5]. PA and LF together make Lethal Toxin (LT), while PA and EF make Edema Toxin (ET) [2, 6]. These toxins act to impair the host immunity [7] and have further systemic effects [8].

B. anthracis has been used as a weapon of bioterrorism. Since the intentional release of B. anthracis spores through the United States (US) postal system in 2001 [9], interest in understanding the immune response to anthrax vaccination has renewed. In the US, the currently licensed vaccine is Anthrax Vaccine Adsorbed (AVA), which is produced from a cell-free filtrate of a toxigenic, acapsulate bovine isolate (V770-NP1-R), containing an unquantified amount of PA and small or negligible amounts of LF and EF [10, 11]. In the United Kingdom (UK), the licensed vaccine is Anthrax Vaccine Precipitated (AVP), which is produced from a cell-free filtrate of a toxigenic, acapsulate strain (Sterne 34F2) and contains roughly 7.9 μg/mL PA and 1.9 μg/mL LF [12]. The current AVA vaccination course consists of 5 intramuscular doses, administered at 0, 1, 6, 12 and 18 months, with subsequent annual boosters [10]. AVP vaccination consists of 4 intramuscular doses, administered at 0, 3, 6 and 32 weeks, with an annual booster [13]. Other distinctions between the vaccines include adsorption to aluminum hydroxide gel (AVA, 0.6 mg Al/dose) versus precipitation with aluminum potassium sulfate (AVP, 0.4 mg Al/dose) and use of different preservatives [14, 15]. These vaccines are thought to protect by eliciting LT-neutralizing PA antibodies [16]. Consequently, recombinant PA alone has been developed as a next generation vaccine and has demonstrated safety and immunogenicity in humans [17–20]. Studies in animal models have demonstrated that LF without PA can provide protection. Immunization with LF alone protected mice from LT challenge [21], and immunization of mice with spores producing bacilli making LF but not PA provided equivalent protection against Sterne spore challenge as compared to immunization with spores producing only PA [22]. These results suggest that the added presence of LF in the AVP vaccine may contribute to toxin neutralization in human vaccinees.

Herein, we compared humoral responses to the AVP and AVA vaccines and tested the hypothesis that human LF antibodies elicited by anthrax vaccination can contribute to LT neutralization. We observed that AVP vaccination induced higher LT neutralization, higher prevalence and titer of LF antibodies, but similar levels of PA antibodies compared to AVA vaccinees matched for number of vaccinations and time post-vaccination. PA and LF IgG independently contributed to in vitro LT neutralization in these samples. Moreover, LF antibodies purified from the plasma of AVP vaccinees neutralized LT and recognized LF Domain 1. These data show that AVP vaccination elicits LF-specific antibodies that contribute to LT neutralization, demonstrating the benefit of including an LF component in PA-containing human vaccine formulations.

Methods

Collection of human blood samples

Individuals were enrolled with informed consent and had been immunized with licensed AVP (n=39) or AVA (n=78). Existing plasma samples from non-vaccinated individuals (n=100) were used as controls to establish thresholds of positivity in ELISA assays. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, and Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. Consent was obtained from staff at Public Health England, United Kingdom. Sera or plasma isolated from AVP or AVA recipients were stored at ≤−20°C until further use.

PA, LF and LF Domain ELISAs

ELISAs were performed as described [23]. Briefly, 96-well plates were coated with 1 μg/well of recombinant PA, LF (List Biologicals, Campbell, CA), or LF domains (see below). Plates were blocked, followed by a 2 h incubation with serum or plasma at room temperature (RT). Alkaline phosphatase-labeled anti-human IgG was used for detection, and optical density (OD410/490) was measured. LF endpoint titer was defined as the last 10-fold dilution giving an OD greater than the average OD plus 2SD above values of 100 unvaccinated controls. PA IgG concentration was calculated using a standard curve of reference serum AVR801 (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA) containing antibodies to PA, serially diluting two-fold at a starting concentration of 109.4 μg/mL [24].

Production of LF domains

LF domain expression was accomplished by cloning cDNAs encoding LF 1 (aa 1-262), LF2a/3 (aa263-386), LF2b (aa 387-550) and LF4 (aa551-776) into pET expression vectors. LF1 was cloned into pET28a using the HindIII reverse site without a stop codon reverse primer to produce 6xhis tags at both the N- and C-termini, which was required for effective purification. LF2a/3, LF2b and LF4 were cloned into pET15b to produce standard N-terminally linked 6-His-containing proteins. LF1 was soluble in PBS and purified by standard Ni2+ affinity chromatography. LF2a/3, 2b and 4, were solubilized in 6M urea, and purified by Ni2+ affinity chromatography with a 20 mM imidazole wash step, and dialyzed into PBS containing 6M urea and 0.05% lauryldimethylamine oxide, followed by stepwise dialysis until the urea concentration was reduced to zero.

J774a.1 LT neutralization assay

This assay was performed as described [12], with minor modifications. Briefly, plasma serial dilutions were pre-incubated with 25 ng PA and 5 ng LF for 30 min at 37°C then added to J774a.1 cells (plated the previous day at 90,000 cells per well in 96-well plates) for 3 h. Next, 50 μL of 1.5 mg/mL MTT was added, and the plates were incubated for 1 h. The OD was measured, and ED50 values were calculated by four-parameter logistic regression [25].

Purification of LF specific IgG

Recombinant LF and PA were produced as previously described [26, 27] and individually bound to cyanogen bromide-preactivated Sepharose 4B following the manufacturer’s protocol (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). To purify LF-specific antibodies, serum samples were passed over the LF column 3 times. On each passage, samples were eluted with 3M NaSCN, buffer exchanged into PBS and concentrated to starting plasma or serum volume (1 mL) using EMD Millipore Amicon™ Ultracel 30,000 NMWL Centrifugal Filter Units (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA). These antibodies were then passed over a PA column once, and the unbound antibodies (affinity purified LF antibodies) were concentrated to 1 mL.

Statistical analyses

AVP-vaccinated individuals (n=39) were matched 1:2 with AVA-vaccinated individuals (n=78) by number of vaccinations, time post-vaccination within 0.3 years, and age where known (Table 1). Between-group comparisons of medians were assessed by Mann-Whitney U test. In all comparisons, mean ± SEM is reported. Between-group proportions were compared by Fisher’s exact test, and associations were reported as odds ratios (OR). Univariate correlations of log-transformed data were analyzed by linear regression.

Table 1.

Vaccination history of AVP and AVA recipients

| AVP (n = 39) | Matched AVA (n = 78) | |

|---|---|---|

| Agea: | ||

| Average (SD) | 33.2 (12.1) | 30.6 (8.9) |

| IQR | 24–42.5 | 23–37 |

| Range | 19–64 | 19–61 |

| Number of Vaccinations: | ||

| Average (SEM) | 5.4 (0.39) | 5.4 (0.28) |

| Median | 4 | 4 |

| Range | 2–11 | 2–11 |

| Years post-Vaccination: | ||

| Average (SEM) | 0.097 (0.031) | 0.151 (0.021) |

| Median | 0.04 | 0.10 |

| Range | 0.02–1.0 | 0.01–0.98 |

Age was known for 26 of 39 AVP samples and was matched 1:2 in 52 AVA samples. Race was known for only 10 of 39 AVP samples and thus was not considered as a covariate.

Multiple linear regression of log-transformed data was used to assess the contribution of PA and LF antibodies to in vitro LT neutralization, as well as influence of vaccination history and demographic factors on antibody responses and LT neutralization. Initial models included interaction term(s). Non-significant interaction term(s) were dropped from the final models. Partial correlation of determination was used to quantify the contribution of terms to the models. Multi-collinearity was assessed by variance inflation factor. Multiple regression analyses were performed in R 3.2.3; all other statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0.

Results

AVP elicits LF antibodies while both AVP and AVA elicit PA antibodies in most vaccinated individuals

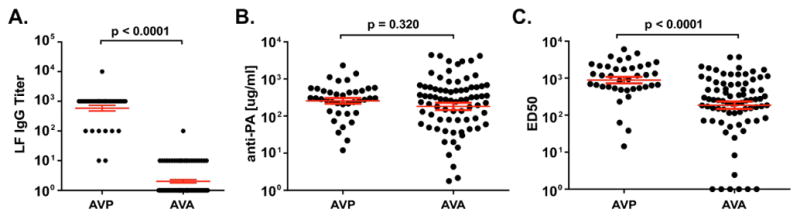

Serum samples from AVP recipients (n=39) matched 1:2 with plasma samples from AVA recipients (n=78) for number of vaccinations, time post-vaccination and age where known (Table 1), were tested for PA and LF antibodies. The overall median number of vaccinations in both groups was 4 (range 2–11). Samples from AVP recipients (37/39, 94.9%) were significantly more likely than matched AVA recipients (1/78, 1.3%) to contain anti-LF IgG at end titer ≥ 100 (p<0.0001, odds ratio (OR) 1425), in keeping with the known presence of quantifiable LF in the AVP preparation. Moreover, the average LF IgG titer differed substantially between the AVP (1042 ± 243.3) and AVA groups (4.8±1.3, p<0.0001; Fig. 1A). However, both groups produced similar concentrations of PA IgG after vaccination (AVP: 412.5 ± 69.6 μg/ml, AVA: 613.1 ± 112.7 μg/ml, p=0.320, Fig. 1B). Samples were also examined for their LT neutralization capacity using an in vitro neutralization assay. AVP recipient samples had significantly higher average LT neutralization ED50 values than samples from matched AVA recipients (AVP: 1464 ± 214.7, AVA: 544.9 ± 83.2, p<0.0001, Fig. 1C). Thus, AVP vaccination elicits higher levels of toxin neutralization, more prevalent and higher LF IgG responses, but similar levels of PA IgG compared to AVA vaccination.

Fig. 1. AVP vaccinees produce robust IgG responses to Lethal Factor and have higher levels of Lethal Toxin neutralization compared to matched AVA vaccinees.

A) End-point titers of serum IgG to recombinant Lethal Factor (LF) from AVP (n=39) compared to matched AVA (n=78) vaccinees. Two AVA data points are below the axis and not shown. B) Levels of serum IgG to recombinant Protective Antigen (PA) in the same samples shown in A) and C). C) 50% effective dilution (ED50) values for serum neutralization of Lethal Toxin determined in a J774A.1 macrophage-based Lethal Toxin neutralization assay. Samples are the same as those shown in A) and B). Red lines show mean ± SEM for all panels. p-values determined by unmatched t-tests.

PA IgG concentration and LF IgG titer are independently and additively associated with in vitro LT neutralization

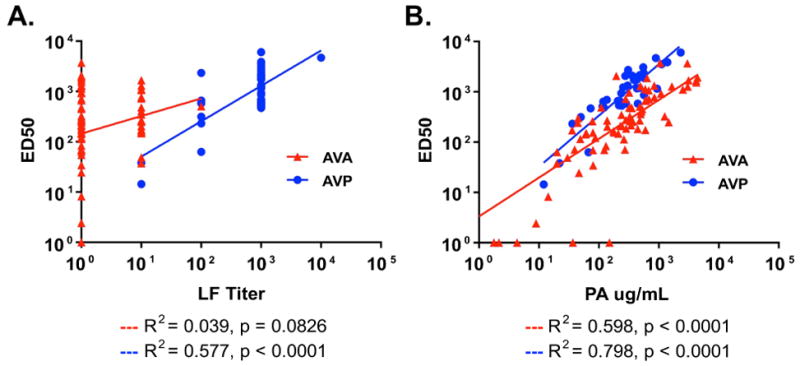

In univariate analyses, LF IgG titer correlated with in vitro LT neutralization only in the AVP cohort (R2=0.577, p<0.0001; Fig. 2A), while PA IgG concentration was associated with in vitro LT neutralization in both AVA (R2=0.598, p<0.0001) and AVP (R2=0.798, p<0.0001; Fig. 2B) cohorts. To determine the relative contribution of PA and LF antibodies to LT neutralization in the AVP group, multiple regression analyses were performed. The initial model detected no evidence of statistical interaction (synergy) between PA IgG concentration and LF IgG titer (p=0.180). A final regression model was constructed without interaction terms (Table 2). This model was unaffected by collinearity (variance inflation factor = 1.9), indicating that LF IgG titer predicts in vitro LT neutralization significantly and independently of PA IgG concentration.

Fig. 2. Correlation of Lethal Factor (LF) and Protective Antigen (PA) IgG levels with Lethal Toxin (LT) neutralization values in AVA and AVP vaccines.

A) Linear regression showing correlation between serum LF titer and LT neutralization ED50 values in AVP but not matched AVA samples. B) Linear regression showing correlation between serum PA IgG levels and LT neutralization ED50 values in both AVP and matched AVA sample groups.

Table 2.

Multiple linear regression of LT neutralization

| R2 | Coefficient (CI)a | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AVP | |||

| Log10(PA IgG μg/mL) | 0.612 | 0.805 (0.588, 1.021) | <0.0001 |

| Log10(LF Titer) | 0.188 | 0.251 (0.075, 0.427) | 0.007 |

| Matched AVA | |||

| Log10(PA IgG μg/mL) | 0.586 | 0.761 (0.614, 0.908) | <0.0001 |

| Log10(LF Titer) | 0.011 | 0.121 (−0.139, 0.381) | 0.356 |

CI=confidence interval

Gender modulates humoral responses to AVP and AVA

To explore the influence of age and gender on humoral responses to anthrax vaccination, a cohort of 26 AVP samples for which these variables were fully known and their matched AVA samples (n=52) were evaluated by multiple regression analysis. Though matching ensured no differences in age between subgroups (AVP mean±SD: 33.2 ± 12.1, AVA: 31.3 ± 8.9), the AVA group contained more male vaccinees (AVP: 50% male, AVA: 82.7% male, OR 4.78, p=0.006). Potential interaction between PA and LF was eliminated from an initial model using an approach of backwards stepwise regression (not shown). In the AVP group, PA IgG concentration positively associated with LT neutralization ED50 (coefficient 0.897, 95% CI=0.597–1.197) in both males and females, whereas LF IgG titer positively associated with LT neutralization ED50 only in females (coefficient 0.297, 95% CI=0.063–0.531, p=0.016; Suppl. Table 1). In the AVA population, LF titer had no association with ED50, as expected. However, PA IgG concentration positively associated with ED50 only in males (coefficient 1.011, 95% CI= 0.769–1.252, p<0.0001). Increased ED50 values occurred in males of the AVA cohort (p=0.009, Mann-Whitney U test, Suppl. Figure 1). Thus, gender effects on humoral immunity to AVP and AVA vaccination are detected.

Purified LF specific antibodies neutralize LT in vitro

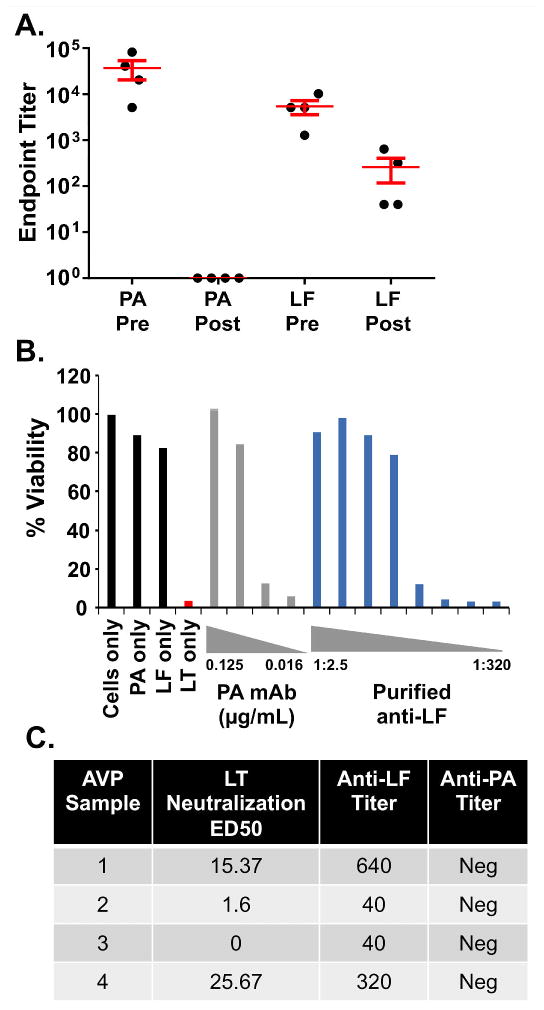

To confirm the LT-neutralizing capacity of LF antibodies in AVP recipients, LF antibodies were purified from AVP serum samples by affinity purification, and their LT neutralization capacity determined. Samples were first subjected to positive selection on an LF affinity column followed by negative selection on a PA affinity column. This approach resulted in pure samples of LF-specific antibodies without contaminating PA antibodies (Fig. 3A). Purified LF antibodies from two of the four samples with LF IgG titers of at least 1:320 neutralized LT in a dose-dependent manner (Fig 3B and C). The remaining two samples with LF IgG titers of only 1:40 failed to neutralize LT, possibly as a result of low antibody concentration. These data directly show that human LF IgG raised by AVP vaccination neutralizes LT.

Fig. 3. Purified Lethal Factor (LF) antibodies from AVP serum samples neutralize Lethal Toxin (LT).

A) End-point IgG titers of reactivity to Protective Antigen (PA) or LF in samples of purified LF antibodies from four independent AVP vaccinees before (pre) and after (post) purification. Post-purification samples were brought to the starting pre-purification volumes. B) Example of results showing the capacity of affinity purified LF antibodies from AVP Sample 4 to neutralize LT-mediated killing of the J774a macrophage cell line (blue bars). A neutralizing PA- specific human monoclonal antibody is included as a positive control (gray bars). Black and red bars are from the control conditions indicated. C) Post-purification LT ED50, LF titer and PA titer of all four affinity purified LF antibody samples from four independent AVP vaccinees. Two samples with LF titers of at least 1:320 neutralized LT in vitro.

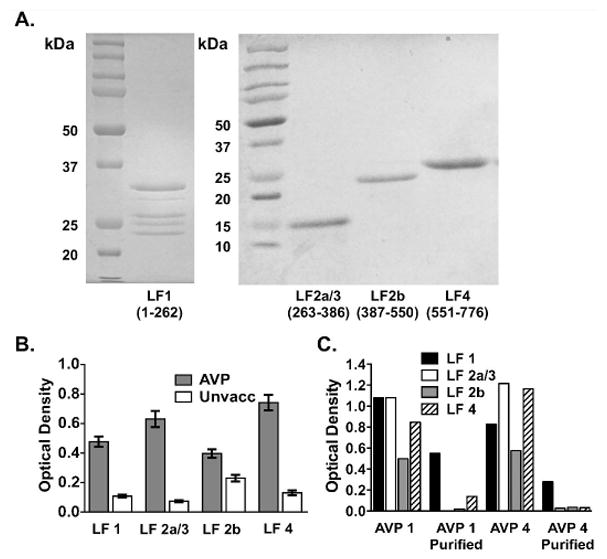

Purified LF antibodies primarily bind LF Domain 1

The purified human LT-neutralizing LF antibodies were examined to determine whether their neutralizing specificity could be assigned to a particular domain. Although the starting whole serum samples of all four subjects exhibited IgG binding to multiple LF domains (Fig. 4A, B), the purified LF antibodies with neutralizing activity from AVP subjects 1 and 4 showed specificity for only the PA-binding Domain 1 of LF (Fig. 4C). Thus, although the affinity purification strategy resulted in unintended selective loss of LF antibodies specific for Domains 2a/3, 2b and 4, the results nevertheless show that purified LF antibodies with LT neutralization activity bind to LF Domain 1.

Fig. 4. Purified Lethal Factor (LF) antibodies with Lethal Toxin (LT)-neutralizing activity bind to LF domain 4.

A) LF domain preparations separated by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and stained with Coomassie blue. B) Average binding of serum IgG from 39 AVP and 39 unvaccinated individuals to each LF domain by ELISA. Error bars are SEM. C) Reactivity to the LF domains before and after LF purification for AVP samples 1 and 4 by ELISA. Optical density thresholds for positivity to each domain as determined by the mean + 2 SD above the mean of values from 54 unvaccinated controls for LF1, LF2a/3, LF 2b and LF4 were 0.228, 0.150, 0.534 and 0.299, respectively.

Discussion

Currently licensed anthrax vaccines suffer from the necessity for multiple initial injections and yearly boosters [13, 28]. Moreover, while 95% of AVA recipients make an anti-PA IgG response, the quality of this response is highly variable. For example, 7.5% of AVA recipients with anti-PA IgG titers ≥ 1:1000 had LT neutralization activity that was indistinguishable from unvaccinated controls [29]. Initiatives to develop less reactogenic and more effective anthrax vaccines resulted in development of recombinant PA [17–20] and consideration of additional vaccine targets including LF [30].

Studies suggest that anthrax vaccination protects by eliciting LT-neutralizing PA antibodies [16]. Although no direct human correlate of protection exists, studies in Rhesus macaques showed that LT neutralization ED50 values of 338 and 367 were associated with 80 and 88% probability of survival, respectively, in animals that had received two intramuscular injections [31, 32]. While PA antibodies are viewed as the primary source of protection, several animal studies have shown that inclusion of LF and/or EF in a PA-based vaccine results in increased levels of protection [21, 22, 33]. Turnbull demonstrated that more guinea pigs immunized with AVP were protected from challenge with the fully virulent Ames strain compared to guinea pigs immunized with AVA [34]. However, no studies in humans have established whether LF or EF contribute to LT neutralization or protection following vaccination.

The quantifiable presence of LF in the AVP formulation [12] and evidence of its relative paucity in AVA [23, 34] led us to compare humoral responses of the two vaccines in order to determine whether LF antibodies contribute to LT neutralization in AVP vaccinees. As expected, LF IgG (titer ≥100) was detected primarily in AVP recipients and rarely in AVA vaccinees, with response rates of 95% and 1%, respectively. This is the largest AVP cohort for which an LF IgG response rate based on ELISA titers has been published, although a study of 15 month post-vaccination samples from 41 Swedish volunteers who received the AVP formulation according to an atypical schedule of three doses at three week intervals showed a wide range of responses [35]. The LF response rate to AVA is in general agreement with our prior larger study of a real world military AVA cohort demonstrating an LF IgG response rate of 6.9% (n=1000) [23].

While many studies have examined human and animal responses to AVP and AVA separately [23, 29, 35–37], few studies have compared PA and LF antibody responses in human recipients of AVP and AVA [34, 38, 39]. These prior studies evaluated small numbers of vaccinees (ranging from 4–6 individuals per group [38] to 11–14 individuals per group [39]), did not match the groups for vaccination history, and did not establish whether LF contributes to LT neutralization in human vaccination. The size and design of our study permitted the use of multiple linear regression to investigate the contribution of the LF IgG response to LT neutralization in AVP recipients. Initial regression modeling revealed no statistical interaction between PA IgG concentration and LF IgG titer, indicating that contributions of these two factors to LT neutralization are additive rather than synergistic. This is in contrast to apparent synergistic activity between passively transferred PA and LF-specific monoclonal antibodies for protecting rats from LT challenge [40] or rabbits from B. anthracis challenge [41]. Importantly, the final multiple regression model indicated that LF IgG titer predicts in vitro LT neutralization significantly and independently of PA IgG concentration in AVP recipients. Equivalent PA responses in both vaccine groups support the concept that enhanced LT neutralization in the AVP group is attributable to the AVP-induced LF response; however, the contribution of adjuvant or other formulation differences to this result cannot be excluded.

The present study uncovered gender effects in response to both AVP and AVA. Male AVA vaccinees showed positive association between PA IgG concentration and LT neutralization and had higher ED50 values. In our study evaluating 1,465 AVA vaccinees [42], we observed that male AVA recipients had higher PA IgG concentrations than females, consistent with results herein. In contrast, PA IgG concentration positively associated with LT neutralization ED50 values in both male and female AVP recipients. Gender also affected LF IgG titers in AVP vaccinees; LF IgG titer positively associated with ED50 selectively in females, regardless of similar ED50 values in both AVP gender groups. A larger study will be required to fully reveal effects of gender on the humoral immune response to AVP.

Finally, we showed that purified LF antibodies with final LF titers ≥1:320 from two independent AVP vaccinees neutralized LT in a dose-dependent manner. Domain-specific ELISA assays demonstrated that these LT neutralizing antibodies bound to LF Domain 1. Along with previous work in which immunization with domain 1 of LF was able to protect mice from a lethal spore challenge [43], this finding supports the hypothesis that the inclusion of LF domain 1 in a PA-based anthrax vaccine, could increase the protective response [43]. The possibility that LT-neutralizing LF antibodies elicited by AVP are also directed to other LF domains is not excluded, however, since the LF affinity column used herein preferentially purified Domain 1-specific LF antibodies.

We conclude that while PA-specific antibodies are the primary contributor to LT neutralization following vaccination with AVP, LF-specific antibodies also contribute to LT neutralization in an independent and additive manner. Inclusion of an LF component in recombinant PA vaccine formulations can be expected to increase the breadth and magnitude of the LT neutralization response.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

AVP and matched AVA recipients make similar IgG responses to PA

AVP recipients have higher ED50 LT neutralization responses

LF IgG makes additive contribution to LT neutralization in AVP recipients

LF antibodies affinity purified from AVP recipients bind Domain 1 and neutralize LT

Gender influences humoral immunity to AVP and AVA

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Walter Reed Army Medical Center Vaccine Healthcare Centers Network/Allergy-Immunology Research Team, the regional Vaccine Healthcare Center Fort Bragg Research Team, all of the study participants, J. Donald Capra for scientific input, Timothy Gross for assistance with affinity columns, Hua Chen for statistical analysis, Wendy Picking for overseeing production of LF fragments, Krista Bean for subject matching, as well as Rebecca Sparks, Philip Cox, Zijian Pan, Lance Pate, Clayton Nelson, Linda Ash, Aaron Guthridge, Thanh Nguyen, Wendy Klein, and Timothy Gross for technical assistance. The authors also thank Rachel Smith for production of figures and Louise Williamson for clerical assistance. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) [grant numbers 2U19 AI062629, P30 GM103510, U54 GM104938 and T32 AI007633] and by the OMRF J. Donald and Patricia Capra Fellowship and the OMRF Lou C. Kerr Chair in Biomedical Research. The opinions and assertions contained herein are private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of Public Health England, the Department of Defense, Department of the Army, NIH, or other government agencies.

Local protocol development and management was supported by Walter Reed Army Medical Center Vaccine Healthcare Centers Network/Allergy-Immunology Department and Womack Army Medical Center, Fort Bragg Regional VHC. Human anti-AVA reference serum (AVR801, NR-719) was obtained through the NIH Biodefense and Emerging Infections Research Repository, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AVA, anthrax vaccine adsorbed; AVP, anthrax vaccine precipitated; LF, lethal factor; LT, lethal toxin; PA, Protective Antigen

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mock M, Fouet A. Anthrax. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:647–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stanley JL, Smith H. Purification of factor I and recognition of a third factor of the anthrax toxin. J Gen Microbiol. 1961;26:49–63. doi: 10.1099/00221287-26-1-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradley KA, Mogridge J, Mourez M, Collier RJ, Young JA. Identification of the cellular receptor for anthrax toxin. Nature. 2001;414:225–9. doi: 10.1038/n35101999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klimpel KR, Arora N, Leppla SH. Anthrax toxin lethal factor contains a zinc metalloprotease consensus sequence which is required for lethal toxin activity. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:1093–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leppla SH. Anthrax toxin edema factor: a bacterial adenylate cyclase that increases cyclic AMP concentrations of eukaryotic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:3162–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.10.3162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stanley JL, Sargeant K, Smith H. Purification of factors I and II of the anthrax toxin produced in vivo. J Gen Microbiol. 1960;22:206–18. doi: 10.1099/00221287-22-1-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tournier JN, Rossi Paccani S, Quesnel-Hellmann A, Baldari CT. Anthrax toxins: a weapon to systematically dismantle the host immune defenses. Mol Aspects Med. 2009;30:456–66. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu S, Moayeri M, Leppla SH. Anthrax lethal and edema toxins in anthrax pathogenesis. Trends Microbiol. 2014;22:317–25. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jernigan JA, Stephens DS, Ashford DA, Omenaca C, Topiel MS, Galbraith M, et al. Bioterrorism-related inhalational anthrax: the first 10 cases reported in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7:933–44. doi: 10.3201/eid0706.010604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright JG, Quinn CP, Shadomy S, Messonnier N. Use of anthrax vaccine in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2009. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leppla SH, Robbins JB, Schneerson R, Shiloach J. Development of an improved vaccine for anthrax. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:141–4. doi: 10.1172/JCI16204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charlton S, Herbert M, McGlashan J, King A, Jones P, West K, et al. A study of the physiology of Bacillus anthracis Sterne during manufacture of the UK acellular anthrax vaccine. J Appl Microbiol. 2007;103:1453–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hepburn MJ, Hugh Dyson E, Simpson AJ, Brenneman KE, Bailey N, Wilkinson L, et al. Immune response to two different dosing schedules of the anthrax vaccine precipitated (AVP) vaccine. Vaccine. 2007;25:6089–97. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biothrax. U.S. Food and Drug Administration; Aug 5, 2016. Fda.Gov. Product insert. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anthrax Vaccine (Alum precipitated sterile filtrate) Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency; Sep 23, 2016. Mhra.gov.uk. Product insert. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brachman PS, Gold H, Plotkin SA, Fekety FR, Werrin M, Ingraham NR. Field Evaluation of a Human Anthrax Vaccine. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1962;52:632–45. doi: 10.2105/ajph.52.4.632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorse GJ, Keitel W, Keyserling H, Taylor DN, Lock M, Alves K, et al. Immunogenicity and tolerance of ascending doses of a recombinant protective antigen (rPA102) anthrax vaccine: a randomized, double-blinded, controlled, multicenter trial. Vaccine. 2006;24:5950–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown BK, Cox J, Gillis A, VanCott TC, Marovich M, Milazzo M, et al. Phase I study of safety and immunogenicity of an Escherichia coli-derived recombinant protective antigen (rPA) vaccine to prevent anthrax in adults. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13849. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bellanti JA, Lin FY, Chu C, Shiloach J, Leppla SH, Benavides GA, et al. Phase 1 study of a recombinant mutant protective antigen of Bacillus anthracis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2012;19:140–5. doi: 10.1128/CVI.05556-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell JD, Clement KH, Wasserman SS, Donegan S, Chrisley L, Kotloff KL. Safety, reactogenicity and immunogenicity of a recombinant protective antigen anthrax vaccine given to healthy adults. Hum Vaccin. 2007;3:205–11. doi: 10.4161/hv.3.5.4459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Price BM, Liner AL, Park S, Leppla SH, Mateczun A, Galloway DR. Protection against anthrax lethal toxin challenge by genetic immunization with a plasmid encoding the lethal factor protein. Infection and immunity. 2001;69:4509–15. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.7.4509-4515.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pezard C, Weber M, Sirard JC, Berche P, Mock M. Protective immunity induced by Bacillus anthracis toxin-deficient strains. Infection and immunity. 1995;63:1369–72. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1369-1372.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crowe SR, Garman L, Engler RJ, Farris AD, Ballard JD, Harley JB, et al. Anthrax vaccination induced anti-lethal factor IgG: fine specificity and neutralizing capacity. Vaccine. 2011;29:3670–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quinn CP, Semenova VA, Elie CM, Romero-Steiner S, Greene C, Li H, et al. Specific, sensitive, and quantitative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for human immunoglobulin G antibodies to anthrax toxin protective antigen. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:1103–10. doi: 10.3201/eid0810.020380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li H, Soroka SD, Taylor TH, Jr, Stamey KL, Stinson KW, Freeman AE, et al. Standardized, mathematical model-based and validated in vitro analysis of anthrax lethal toxin neutralization. J Immunol Methods. 2008;333:89–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salles II, Voth DE, Ward SC, Averette KM, Tweten RK, Bradley KA, et al. Cytotoxic activity of Bacillus anthracis protective antigen observed in a macrophage cell line overexpressing ANTXR1. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:1272–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Voth DE, Hamm EE, Nguyen LG, Tucker AE, Salles II, Ortiz-Leduc W, et al. Bacillus anthracis oedema toxin as a cause of tissue necrosis and cell type-specific cytotoxicity. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:1139–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wright JG, Plikaytis BD, Rose CE, Parker SD, Babcock J, Keitel W, et al. Effect of reduced dose schedules and intramuscular injection of anthrax vaccine adsorbed on immunological response and safety profile: a randomized trial. Vaccine. 2014;32:1019–28. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crowe SR, Ash LL, Engler RJ, Ballard JD, Harley JB, Farris AD, et al. Select human anthrax protective antigen epitope-specific antibodies provide protection from lethal toxin challenge. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:251–60. doi: 10.1086/653495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Altmann DM. Host immunity to Bacillus anthracis lethal factor and other immunogens: implications for vaccine design. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2015;14:429–34. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2015.981533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quinn CP, Sabourin CL, Niemuth NA, Li H, Semenova VA, Rudge TL, et al. A three-dose intramuscular injection schedule of anthrax vaccine adsorbed generates sustained humoral and cellular immune responses to protective antigen and provides long-term protection against inhalation anthrax in rhesus macaques. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2012;19:1730–45. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00324-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ionin B, Hopkins RJ, Pleune B, Sivko GS, Reid FM, Clement KH, et al. Evaluation of immunogenicity and efficacy of anthrax vaccine adsorbed for postexposure prophylaxis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2013;20:1016–26. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00099-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gupta M, Alam S, Bhatnagar R. Catalytically inactive anthrax toxin(s) are potential prophylactic agents. Vaccine. 2007;25:8410–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turnbull PC, Broster MG, Carman JA, Manchee RJ, Melling J. Development of antibodies to protective antigen and lethal factor components of anthrax toxin in humans and guinea pigs and their relevance to protective immunity. Infect Immun. 1986;52:356–63. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.2.356-363.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baillie L, Townend T, Walker N, Eriksson U, Williamson D. Characterization of the human immune response to the UK anthrax vaccine. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2004;42:267–70. doi: 10.1016/j.femsim.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cybulski RJ, Jr, Sanz P, O’Brien AD. Anthrax vaccination strategies. Mol Aspects Med. 2009;30:490–502. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chitlaru T, Altboum Z, Reuveny S, Shafferman A. Progress and novel strategies in vaccine development and treatment of anthrax. Immunol Rev. 2011;239:221–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brenneman KE, Doganay M, Akmal A, Goldman S, Galloway DR, Mateczun AJ, et al. The early humoral immune response to Bacillus anthracis toxins in patients infected with cutaneous anthrax. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2011;62:164–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2011.00800.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laws TR, Kuchuloria T, Chitadze N, Little SF, Webster WM, Debes AK, et al. A Comparison of the Adaptive Immune Response between Recovered Anthrax Patients and Individuals Receiving Three Different Anthrax Vaccines. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0148713. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen Z, Moayeri M, Crown D, Emerson S, Gorshkova I, Schuck P, et al. Novel chimpanzee/human monoclonal antibodies that neutralize anthrax lethal factor, and evidence for possible synergy with anti-protective antigen antibody. Infection and immunity. 2009;77:3902–8. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00200-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Albrecht MT, Li H, Williamson ED, LeButt CS, Flick-Smith HC, Quinn CP, et al. Human monoclonal antibodies against anthrax lethal factor and protective antigen act independently to protect against Bacillus anthracis infection and enhance endogenous immunity to anthrax. Infection and immunity. 2007;75:5425–33. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00261-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garman L, Vineyard AJ, Crowe SR, Harley JB, Spooner CE, Collins LC, et al. Humoral responses to independent vaccinations are correlated in healthy boosted adults. Vaccine. 2014;32:5624–31. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baillie LW, Huwar TB, Moore S, Mellado-Sanchez G, Rodriguez L, Neeson BN, et al. An anthrax subunit vaccine candidate based on protective regions of Bacillus anthracis protective antigen and lethal factor. Vaccine. 2010;28:6740–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.07.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.