Abstract

There is strong evidence of a positive association between corporal punishment and negative child outcomes, but previous studies have suggested that the manner in which parents implement corporal punishment moderates the effects of its use. This study investigated whether severity and justness in the use of corporal punishment moderate the associations between frequency of corporal punishment and child externalizing and internalizing behaviors. This question was examined using a multicultural sample from eight countries and two waves of data collected one year apart. Interviews were conducted with 998 children aged 7-10 years, and their mothers and fathers, from China, Colombia, Italy, Jordan, Kenya, Philippines, Thailand, and the United States. Mothers and fathers responded to questions on the frequency, severity, and justness of their use of corporal punishment; they also reported on the externalizing and internalizing behavior of their child. Children reported on their aggression. Multigroup path models revealed that across cultural groups, and as reported by mothers and fathers, there is a positive relation between the frequency of corporal punishment and externalizing child behaviors. Mother-reported severity and father-reported justness were associated with child-reported aggression. Neither severity nor justness moderated the relation between frequency of corporal punishment and child problem behavior. The null result suggests that more use of corporal punishment is harmful to children regardless of how it is implemented, but requires further substantiation as the study is unable to definitively conclude that there is no true interaction effect.

Keywords: corporal punishment, multicultural, moderation, severity of punishment, consistency of punishment, justness of punishment, externalizing problems, internalizing problems

Studies have proliferated on whether and how parents' use of corporal punishment affects children's development. Yet key questions remain unresolved, and the discourse continues on whether a universal ban on corporal punishment is justified (Gershoff & Bitensky, 2007; Larzelere & Baumrind, 2010). This study determines whether factors in the disciplinary context, namely severity and justness, moderate associations between frequency of corporal punishment use and internalizing and externalizing child behaviors, as reported by mothers and fathers in 8 countries. Investigating interactions among these different dimensions of corporal punishment contributes to our understanding of how punishment is administered moderates its impact. Some researchers have argued that it is the manner of administering parental corporal punishment that spells the difference in consequences for children (e.g. Baumrind, 1997; Baumrind, Larzelere, & Owens, 2010). These particular moderators of corporal punishment have been rarely examined within a single culture, much less with a multicultural sample.

Corporal punishment is here defined as “the use of physical force with the intention of causing a child to experience pain, but not injury, for the purpose of correction or control of the child's behavior” (Straus & Stewart, 1999, p.57). Compelling evidence has accumulated that corporal punishment is directly associated with negative outcomes in children, even as it may increase children's short-term compliance. In their meta-analytic reviews, Gershoff (2002a) and Ferguson (2013) reported small to moderate associations between more corporal punishment and higher externalizing and internalizing behaviors, lower quality relationships, and poorer mental health in childhood and adulthood. Such associations between corporal punishment, negative child behaviors, and poor psychological adjustment are evident across cultural and ethnic groups (e.g., Gershoff et al., 2012; Lansford et al., 2005; McLoyd & Smith, 2002), in cross-lagged, transactional analyses within-time and across age in childhood (e.g., Berlin et al., 2009; Choe, Olson, & Sameroff, 2013; Maguire-Jack, Gromoske, & Berger, 2012), and through to early adolescence (MacKenzie, Nicklas, Brooks-Gunn, & Waldfogel, 2015). Gershoff and Grogan-Kaylor (2016) report in a recent meta-analysis that the associations between spanking and detrimental child and adult outcomes were robust across variations in measures, raters, time periods, and countries, and in both cross-sectional and longitudinal designs.

Severity of Corporal Punishment as Moderator

Certain factors have been found to moderate the relations between corporal punishment and child outcomes, such as maternal support and warmth (McLoyd & Smith, 2002; German, Gonzalez, McClain, Dumka, & Millsap, 2013), and perceptions of normativeness of corporal punishment (Lansford et al., 2005). Corporal punishment is implemented in different ways in different families, and factors relevant to the implementation of the disciplinary act itself may also play a role in influencing the effects of corporal punishment. Deater-Deckard and Dodge (1997) proposed that the relation between parental physical punishment and child externalizing behaviors is nonlinear; that is, that the degree of this association varies according to the severity of the punishment, such that harsh forms of punishment are much more strongly associated with child aggression than milder forms. Even within the range of disciplinary experiences considered normal or non-abusive, variations in parents' punishment may result in non-trivial variations in child outcomes (Baumrind, 1997).

Yet the question of how corporal punishment is administered is rarely asked relative to frequency, and frequency and severity are often conflated in measures of corporal punishment. In Gershoff's (2002a) meta-analytic review, she noted that 69% of the studies measured frequency of corporal punishment, only 9% measured severity, and 5% asked about both frequency and severity. For spanking, only 8 out of the 111 effects that were analyzed in Gershoff and Grogan-Kaylor's (2016) meta-analysis defined it in terms of both frequency and severity.

In several studies, Straus and colleagues' definition of severity, or some variation thereof, is used: “severe” behaviors are those that carry higher risk of injury and are less widely accepted, such as slapped on face or head, pinched, and hit with belt or hard object; “mild” or less severe were spanking on bottom with hand and slapping on hand, arm, or leg (Straus & Stewart, 1999). The frequencies of use of these forms of corporal punishment (that vary in severity) are then treated as main or predictor variables of child outcomes, with mixed results. Spanking or slapping with the hand or an object (i.e., mild or less severe) has been found to be a modest to moderately strong predictor of externalizing behaviors (Choe, Olson, & Sameroff, 2013; Berlin et al., 2009; Gershoff, 2002a; McLoyd & Smith, 2002), but neither detrimental nor beneficial effects of such mild or “ordinary” punishment have been found in other studies (Baumrind, Larzelere, & Owens, 2010). Lapre and Marsee (2016) report that severe corporal punishment, which they defined as hitting/slapping/hitting with an object, was related to aggression among Caucasian and African American adolescents, whereas mild punishment (spanking) was not for either group. Among 10-year-old Chinese children, both mild and severe corporal punishment was associated with subsequent increases in internalizing problems for girls; for boys, only severe punishment predicted increases in internalizing problems (Xing & Wang, 2013). Comparing the effects from within-subjects studies that report data for both spanking and abusive physical punishment, both were found to have statistically significant and detrimental consequences for children, albeit physical abuse had a larger mean effect size (Gershoff & Grogan-Kaylor, 2016).

In the aforementioned studies, more severity is clearly deleterious, and even less severe or mild corporal punishment is, at best, without effect. But categorizing punishment behaviors as more or less severe and testing them as predictors, or conflating severity with frequency, do not directly address whether severity functions to moderate the effects of corporal punishment, as suggested by Deater-Deckard and Dodge (1997). In light of the complex findings from previous studies, it is imperative to disentangle frequency and severity of punishment. Thus, another way of investigating the question is to examine whether severity interacts with frequency in predicting child outcomes. That is, would the severity of corporal punishment exacerbate the relation between frequency of corporal punishment and negative child adjustment? Such an analysis could show whether corporal punishment administered often, but in a manner that is mild or “not hard,” is relatively better or worse for children's adjustment than corporal punishment that is infrequent, but severe.

Justness of Corporal Punishment as Moderator

Apart from severity, this study considers justness as another potential moderator in the association between frequency of corporal punishment and child behavior outcomes. Justness or fairness is implied in what has been argued as “prudent” discipline (Baumrind, 1997) and instrumental discipline (Gershoff, 2002a). Prudent and instrumental discipline are described as planned, controlled, and part of the parents' usual disciplinary repertoire; imprudent discipline is arbitrary and results from impulse or outbursts of negative emotions.

Parents' discipline strategies influence the extent of children's awareness, acceptance, and eventual internalization of parental messages (Grusec & Goodnow, 1994; McCabe, Mechammil, Yeh, & Zerr, 2016). In particular, parental responses to child transgressions that are commensurate, appropriate, and relevant to the misdeed are considered by children as just or fair, and are therefore more likely to be accepted (Grusec & Goodnow, 1994). By contrast, children may respond in anger, defiance, or fear, and increase their aversive behaviors, if they view their parents' demands as unreasonable (Baumrind, 1997; Baumrind, Larzelere, & Owens, 2010; Gershoff, 2002a; Patterson, 2002). Moreover, Rohner and colleagues report that perceived justness of physical punishment was associated with perceived caregiver acceptance-rejection, which in turn predicted the psychological adjustment of African American and European American youth (Rohner, Bourque, & Elordi, 1996).

The interaction between justness and frequency of corporal punishment has yet to be directly examined. A study that approximates these constructs and relations is Straus and Mouradian's (1998), which tested the interaction of frequency of corporal punishment and mothers' impulsivity when implementing it. Impulsive punishment was described as that carried out without control or forethought and driven by strong negative emotions (i.e. anger). The highest levels of antisocial behavior were found for children whose parents used corporal punishment out of anger for at least half the times they applied it, which suggests that volatile and disproportionate punishment may compound the negative effects of corporal punishment.

The Current Study

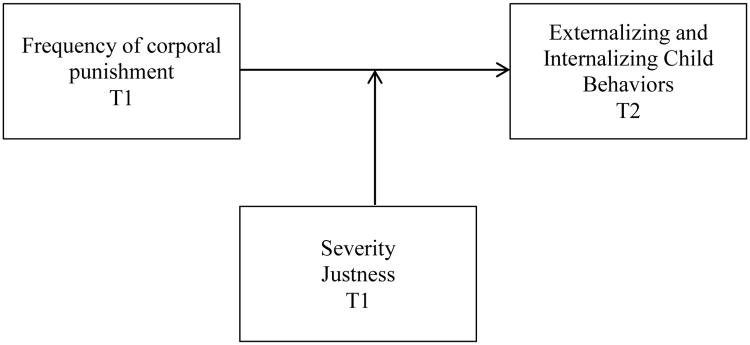

Previous research has shown consistent negative associations between the use of corporal punishment and children's adjustment, and this study expects to find the same main effects of frequency of corporal punishment on children's externalizing and internalizing behaviors. Further, this study investigates whether severity and justness interact with frequency of use of corporal punishment in predicting children's internalizing and externalizing problems (Figure 1). Higher severity may function to exacerbate negative outcomes, consistent with the proposition that the magnitude of the effects of corporal punishment depend on the severity of the discipline (Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997). Previous studies have generally borne this out, but using analyses that examined the main effects of discipline behaviors categorized by severity, rather than the interaction of severity and frequency.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized conceptual framework of the main effect of frequency of corporal punishment and the moderating effects of severity and justness (all measured at Time 1), on externalizing and internalizing child behaviors (at Time 2)

For justness, it is predicted that higher levels would buffer the association between corporal punishment and children's negative outcomes. Fair as opposed to unreasonable discipline may moderate the negative effects of corporal punishment as it is more likely to be accepted by children and facilitate transmission of the parental message (Baumrind, 1997; Grusec & Goodnow, 1994).

These questions are addressed using data from the Parenting Across Cultures study, which is composed of a multicultural sample of mothers, fathers, and children from 12 cultural groups in 9 countries: Jinan and Shanghai in China, Colombia, Rome and Naples in Italy, Jordan, Kenya, the Philippines, Sweden, Thailand, and the United States. This sample of countries varies on several key characteristics, such as human development indicators (i.e. the countries rank from 8th to 145th out of 188 countries on the Human Development Index; United Nations Development Programme, 2015), predominant ethnicity and religion, and parenting belief systems. This study thus presents an important opportunity to clarify culture-specific vis-a-vis generalizable factors in the associations between parent corporal punishment and child development.

Method

Participants

Data from the Parenting Across Cultures study were utilized for these analyses. The sample was limited to families with at least one parent who reported ever using corporal punishment in Time 1. A total of 886 mothers (Time 1 age M = 36.32, SD = 6.16), 668 fathers (Time 1 age M = 39.47, SD = 6.29), and 998 children (Time 1 age M = 8.29, SD = .62, 49.2% girls) were drawn from from 8 countries (child sample sizes reported by country): China (n = 185); Colombia (n = 79); Italy (n = 149); Jordan (n = 89); Kenya (n = 95); Philippines (n = 100); Thailand (n = 104); and United States (n = 197). Data from Sweden were collected but were excluded from this analysis as virtually no parents reported using corporal punishment, which has been outlawed in Sweden since 1979. The majority (85%) of parents were married, and 96% were the target child's biological parents; the other respondents were grandparents, stepparents, and other adult caregivers.

The sample of families in each site approximated the socioeconomic distribution in the population, and included families that belonged to the majority ethnic group in each country (except for Kenya, where the Luo ethnic group is the third largest; and the United States, where European American, African American, and Latin American families were included). The samples are not presumed to be representative of the country. Letters were sent to the families in each site through schools that served socioeconomically diverse populations of children. Parents who indicated their interest in participating were then contacted by trained researchers who provided more information about the project. Interviews were scheduled and informed consent was obtained from parents who volunteered to participate in the study. Children likewise signified their willingness to participate via assent forms.

Mothers, fathers, and children were interviewed annually beginning when children were approximately 8 years old. The present analyses used mother- and father-reported data on corporal punishment (frequency, severity, and justness) at Time 1; and mother- and father-reported externalizing and internalizing behaviors, and child-reported aggression, one year later at Time 2. Ninety-four percent of the sample who reported ever using corporal punishment in Time 1 provided data in Time 2.

Procedures and Measures

Measures were administered in the predominant language in each site. Forward- and back-translations were conducted by bilingual researchers, and meetings were convened to discuss and resolve ambiguities in the linguistic or semantic content of the items.

Interviews were conducted in homes, schools, or other locations convenient to the family. Parents were given the choice to answer the measures independently in writing, or to have the measures administered via oral interview. In the case of the latter, visual aids of the response scales facilitated parents' responding. All child measures were administered via oral interview. The child, mother, and father were interviewed separately by trained researchers; each interview lasted about 1.5 to 2 hours. Children received small tokens for their participation, and parents received modest financial compensation. The procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board in each site.

Frequency of corporal punishment

Information about physical punishment was gathered using the parent-reported Physical Punishment Questionnaire (PPQ) designed by Rohner and Khaleque (2005). Frequency of punishment is measured by a single item describing how often the parent physically punished the child, where 1 = 1-2 times ever, 2 = less than once a month, 3 = once a month, 4 = once a week, or 5 = almost every day.

Severity and justness of corporal punishment

The severity of the punishment is captured by a 4-point PPQ item measuring the overall severity of physical punishment (1 = not hard at all, 2 = not very hard, 3 = a little hard, or 4 = very hard). Two PPQ items measure parent's belief about the fairness of their punishment (from 1 = very unfair to 4 = very fair) and whether the punishment was deserved (1 = almost never to 4 = almost always). These two items were averaged to measure parent's belief about the justness of their use of physical punishment with higher values indicating greater justness.

Parent-reported child internalizing and externalizing behavior

Parent-reported child problem behavior was captured by Achenbach's Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL). Mothers and fathers indicated the extent to which their child exhibited a particular behavior or emotion in the previous 6 months, using the scale not true (coded 0), somewhat or sometimes true (coded 1), or very often or often true (coded 2). The CBCL externalizing behavior scale includes 33 items capturing aggressive and delinquent behaviors (e.g., My child gets in many fights). The CBCL internalizing behavior scale includes 31 items capturing child withdrawal, anxiety/depression, and somatic problems (e.g., My child is too fearful or anxious). The externalizing and internalizing scales are created by summing across items.

Child-reported aggression

Children responded to the Behavior Frequency Scale (BFS), which consists of items compiled from Farrell et al. (1992), Crick and Bigbee (1998), and Orpinas and Frankowski (2001). Children were asked how often in the last 30 days they engaged in a series of aggressive behaviors, using a scale ranging from 0 (never) to 5 (20 or more times). Three mean scales were created from the BFS items. The non-physical aggression scale included 6 items (e.g., teased someone to make them angry); the physical aggression scale contained 10 items (e.g., shoved and pushed another kid); the relational aggression scale included 6 items (e.g., spread a false rumor about someone). Table 1 provides the scale means, standard deviations, and Cronbach's coefficient alphas (when appropriate) within each country.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics by Cultural Group: Mean, (Standard Deviation), Sample Size, and [Cronbach's coefficient alpha].

| Frequency of Corporal Punishment Time 1 (a) | Severity of Corporal Punishment Time 1 (b) | Justness of Corporal Punishment Time 1 (c) | CBCL Externalizing Time 2 (d) | CBCL Internalizing Time 2 (e) | Child-Reported BFS (f) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Physical | Physical | Relational | |||||||||||

| Aggression | Aggression | Aggression | |||||||||||

| Father | Mother | Father | Mother | Father | Mother | Father | Mother | Father | Mother | Time 2 | Time 2 | Time 2 | |

| China | 1.641 (0.887) n=156 [0.678] | 1.697 (0.927) n=165 [0.756] | 1.942 (0.747) n=156 | 1.898 (0.727) n=166 | 2.34 (0.682) n=156 [0.678] | 2.5 (0.741) n=166 [0.756] | 8.275 (5.446) n=142 [0.841] | 8.526 (5.533) n=154 [0.844] | 6.648 (5.671) n=142 [0.849] | 6.734 (5.443) n=154 [0.833] | 0.066 (0.156) n=185 [0.508] | 0.049 (0.101) n=185 [0.458] | 0.123 (0.208) n=185 [0.38] |

| Colombia | 1.881 (0.93) n=59 [0.714] | 2.408 (1.085) n=76 [0.563] | 3.593 (0.722) n=59 | 3.5 (0.739) n=76 | 2.881 (1.023) n=59 [0.714] | 2.658 (0.884) n=76 [0.563] | 11.389 (7.011) n=54 [0.824] | 13.366 (8.543) n=71 [0.875] | 12.389 (8.586) n=54 [0.885] | 15.085 (9.763) n=71 [0.904] | 0.652 (0.804) n=79 [0.834] | 0.294 (0.397) n=79 [0.717] | 0.341 (0.486) n=79 [0.704] |

| Italy | 2 (1.107) n=99 [0.592] | 2.095 (1.162) n=137 [0.516] | 3.465 (0.747) n=99 | 3.464 (0.812) n=138 | 2.232 (0.754) n=99 [0.592] | 2.221 (0.733) n=138 [0.516] | 11.598 (6.347) n=87 [0.836] | 12.16 (7.025) n=131 [0.845] | 9.149 (7.123) n=87 [0.882] | 11.588 (8.486) n=131 [0.89] | 0.506 (0.579) n=149 [0.677] | 0.207 (0.284) n=149 [0.62] | 0.35 (0.494) n=149 [0.664] |

| Jordan | 2.338 (0.982) n=77 [0.565] | 2.25 (1.013) n=80 [0.467] | 1.896 (0.836) n=77 | 1.8 (0.802) n=80 | 2.721 (0.7) n=77 [0.565] | 2.656 (0.668) n=80 [0.467] | 11.844 (6.928) n=77 [0.848] | 13.813 (8.135) n=80 [0.885] | 9.779 (5.913) n=77 [0.809] | 10.888 (5.829) n=80 [0.796] | 0.352 (0.513) n=89 [0.773] | 0.54 (0.681) n=89 [0.837] | 0.329 (0.453) n=89 [0.664] |

| Kenya | 2.404 (1.039) n=99 [0.517] | 3.061 (0.818) n=99 [0.477] | 2.879 (0.732) n=99 | 2.859 (0.904) n=99 | 3.515 (0.679) n=99 [0.517] | 3.591 (0.595) n=99 [0.477] | 10.067 (6.592) n=90 [0.807] | 8.053 (5.878) n=94 [0.807] | 7.367 (5.261) n=90 [0.759] | 7.362 (5.537) n=94 [0.794] | 0.688 (0.738) n=95 [0.867] | 0.398 (0.355) n=95 [0.737] | 0.753 (0.915) n=95 [0.897] |

| Philippines | 1.293 (0.908) n=78 [0.747] | 2.293 (1.1) n=99 [0.727] | 1.795 (0.858) n=78 | 2.01 (0.914) n=98 | 2.577 (0.898) n=78 [0.747] | 2.576 (0.797) n=99 [0.727] | 12.631 (7.713) n=65 [0.896] | 12.944 (7.893) n=90 [0.891] | 9.831 (6.194) n=65 [0.855] | 11.067 (6.596) n=90 [0.836] | 0.35 (0.634) n=100 [0.815] | 0.274 (0.506) n=100 [0.867] | 0.375 (0.595) n=100 [0.714] |

| Thailand | 2.125 (1.096) n=56 [0.679] | 2.043 (0.994) n=94 [0.468] | 1.804 (0.724) n=56 | 1.596 (0.693) n=94 | 3.054 (0.802) n=56 [0.679] | 2.963 (0.723) n=94 [0.468] | 11 (5.892) n=51 [0.835] | 10.33 (6.967) n=91 [0.888] | 8.961 (5.542) n=51 [0.806] | 10.582 (6.799) n=91 [0.871] | 0.236 (0.417) n=104 [0.748] | 0.151 (0.261) n=104 [0.653] | 0.346 (0.551) n=104 [0.823] |

| US | 1.778 (0.818) n=90 [0.646] | 1.89 (0.801) n=200 [0.631] | 2.211 (0.942) n=90 | 2.15 (0.996) n=200 | 3.344 (0.788) n=90 [0.646] | 3.307 (0.799) n=199 [0.631] | 7.908 (6.329) n=76 [0.875] | 9.166 (8.083) n=181 [0.903] | 7.316 (6.317) n=76 [0.884] | 7.475 (6.615) n=181 [0.869] | 0.21 (0.389) n=197 [0.743] | 0.133 (0.239) n=197 [0.692] | 0.123 (0.248) n=197 [0.587] |

Note.

Frequency of punishment ranges from 1 to 5, where 1 = 1-2 times ever, 2 = less than once a month, 3 = once a month, 4 = once a week, or 5 = almost every day.

Severity of punishment ranges from 1 to 4, where 1 = not hard at all, 2 = not very hard, 3 = a little hard, and 4 = very hard.

Justness of punishment ranges from 1 to 4 with higher values indicating greater justness.

Externalizing problem behavior ranges from 0 to 66 with higher scores indicating more problem behaviors.

Internalizing problem behavior ranges from 0 to 62 with higher scores indicating more problem behaviors.

Analytic Approach

The relation between parent-reported frequency of corporal punishment (Time 1) and each scale capturing problematic child behavior (parent-reported and child-reported at Time 2) was estimated using a multigroup path model with freely estimated country intercepts and residual variances to account for differences in the 8 country groups. The model also controlled for the main effects of the two moderators (severity and justness of the corporal punishment) as well as child gender, child age, years of formal education of the more educated parent, and family income. These relations were fixed across countries. All scales were grand mean-centered. To account for missing data, the models were estimated using full-information maximum likelihood (FIML). Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square tests were used to assess whether the model fit improved when each relation is allowed to vary by site (Satorra, 2000). When fit improved, a series of pairwise tests was conducted to compare the differences in the relation between all groups. Holm's (1997) correction was used to adjust for multiple post-hoc comparisons. A second model was estimated which included interactions to assess whether the severity and justness of the corporal punishment moderates the relation between the frequency of corporal punishment and problematic child behavior. Again, Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square tests determined whether the model fit improved when the interaction terms varied by site. When fit improved, pairwise tests were conducted to compare the differences in the interaction terms between all groups, correcting for multiple comparisons.

Results

Main Effects of Frequency, Severity, and Justness of Corporal Punishment on Child Externalizing and Internalizing Behaviors

Table 2 describes the main effects of Time 1 frequency, severity, and justness of corporal punishment on Time 2 problematic child behavior. The standardized estimates refer to the increase in the grand mean-centered outcome score in standard deviation units. The table also provides the Chi-square test results assessing whether model fit improves when the relations were allowed to vary by site.

Table 2. Main Effects of Frequency, Severity, and Justness When Relations are Fixed across Countries.

| Mother-Reported Punishment | Father-Reported Punishment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Std Est | SE | 95% CI | Variation by Country X2(7), (pval) | Std Est | SE | 95% CI | Variation by Country X2(7), (pval) | |

| Parent-report Externalizing | ||||||||

| Frequency of Corporal Punishment | 0.147* | 0.041 | [0.066, 0.227] | 13.133 (0.069) | 0.178* | 0.043 | [0.094, 0.261] | 7.377 (0.391) |

| Severity of Corporal Punishment | 0.073 | 0.043 | [-0.011, 0.158] | 6.103 (0.528) | 0.036 | 0.053 | [-0.068, 0.14] | 3.743 (0.809) |

| Justness of Corporal Punishment | -0.024 | 0.035 | [-0.093, 0.044] | 3.472 (0.838) | -0.009 | 0.044 | [-0.095, 0.078] | 6.427 (0.491) |

| Indicator for Male Child | 0.087 | 0.065 | [-0.04, 0.215] | -0.046 | 0.082 | [-0.207, 0.114] | ||

| Child's Age | -0.038 | 0.035 | [-0.106, 0.03] | -0.034 | 0.044 | [-0.121, 0.052] | ||

| Family Income | -0.162* | 0.041 | [-0.242, -0.082] | -0.135* | 0.054 | [-0.242, -0.029] | ||

| Years of Education for Most Educated Parent | 0.037 | 0.039 | [-0.039, 0.113] | 0.089 | 0.05 | [-0.01, 0.187] | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Parent-report Internalizing | ||||||||

| Frequency of Corporal Punishment | 0.055 | 0.037 | [-0.017, 0.127] | 10.633 (0.155) | 0.074 | 0.043 | [-0.011, 0.158] | 17.124 (0.017)+ |

| Severity of Corporal Punishment | 0.052 | 0.041 | [-0.028, 0.133] | 10.106 (0.183) | 0.078 | 0.054 | [-0.028, 0.183] | 9.034 (0.25) |

| Justness of Corporal Punishment | -0.052 | 0.034 | [-0.119, 0.015] | 4.279 (0.747) | -0.059 | 0.044 | [-0.145, 0.027] | 13.209 (0.067) |

| Indicator for Male Child | -0.041 | 0.061 | [-0.161, 0.079] | -0.126 | 0.075 | [-0.272, 0.02] | ||

| Child's Age | -0.005 | 0.035 | [-0.073, 0.063] | 0.002 | 0.038 | [-0.072, 0.076] | ||

| Family Income | -0.096* | 0.039 | [-0.173, -0.019] | -0.059 | 0.05 | [-0.158, 0.04] | ||

| Years of Education for Most Educated Parent | -0.045 | 0.036 | [-0.116, 0.027] | 0.062 | 0.043 | [-0.023, 0.146] | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Child-report Non-Physical Aggression | ||||||||

| Frequency of Corporal Punishment | 0.021 | 0.021 | [-0.02, 0.062] | 11.131 (0.133) | 0.016 | 0.023 | [-0.029, 0.062] | 8.806 (0.267) |

| Severity of Corporal Punishment | 0.065* | 0.02 | [0.025, 0.104] | 7.597 (0.369) | -0.047 | 0.026 | [-0.097, 0.003] | 12.794 (0.077) |

| Justness of Corporal Punishment | -0.021 | 0.025 | [-0.069, 0.028] | 11.894 (0.104) | 0.065* | 0.028 | [0.011, 0.119] | 1.617 (0.978) |

| Indicator for Male Child | 0.137 | 0.034 | [0.07, 0.204] | 0.2 | 0.041 | [0.119, 0.282] | ||

| Child's Age | -0.007 | 0.027 | [-0.06, 0.047] | -0.01 | 0.036 | [-0.08, 0.061] | ||

| Family Income | 0.022 | 0.017 | [-0.011, 0.056] | 0.008 | 0.021 | [-0.034, 0.05] | ||

| Years of Education for Most Educated Parent | -0.029 | 0.022 | [-0.072, 0.015] | -0.026 | 0.027 | [-0.078, 0.027] | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Child-report Physical Aggression | ||||||||

| Frequency of Corporal Punishment | 0.024 | 0.019 | [-0.013, 0.061] | 5.75 (0.569) | 0.01 | 0.022 | [-0.034, 0.053] | 10.132 (0.181) |

| Severity of Corporal Punishment | 0.057* | 0.02 | [0.018, 0.097] | 6.164 (0.521) | 0.019 | 0.027 | [-0.035, 0.072] | 7.629 (0.366) |

| Justness of Corporal Punishment | 0.021 | 0.02 | [-0.019, 0.06] | 21.844 (0.003)+ | 0.073* | 0.027 | [0.02, 0.125] | 7.32 (0.396) |

| Indicator for Male Child | 0.178* | 0.035 | [0.111, 0.246] | 0.214* | 0.041 | [0.134, 0.294] | ||

| Child's Age | -0.074* | 0.025 | [-0.124, -0.024] | -0.032 | 0.029 | [-0.09, 0.025] | ||

| Family Income | -0.006 | 0.017 | [-0.039, 0.027] | -0.009 | 0.021 | [-0.051, 0.033] | ||

| Years of Education for Most Educated Parent | -0.04* | 0.02 | [-0.079, -0.001] | -0.042 | 0.023 | [-0.088, 0.003] | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Child-report Relational Aggression | ||||||||

| Frequency of Corporal Punishment | 0.032 | 0.028 | [-0.023, 0.088] | -0.642 (0.999) | 0.048* | 0.024 | [0.001, 0.095] | 7.319 (0.396) |

| Severity of Corporal Punishment | 0.059* | 0.025 | [0.01, 0.108] | 6.358 (0.499) | -0.017 | 0.025 | [-0.065, 0.032] | 15.451 (0.031) (a) |

| Justness of Corporal Punishment | 0.016 | 0.023 | [-0.03, 0.061] | 3.197 (0.866) | 0.048 | 0.026 | [-0.003, 0.098] | 2.629 (0.917) |

| Indicator for Male Child | 0.093* | 0.04 | [0.015, 0.17] | 0.076 | 0.044 | [-0.011, 0.164] | ||

| Child's Age | -0.021 | 0.026 | [-0.072, 0.029] | -0.016 | 0.031 | [-0.076, 0.044] | ||

| Family Income | 0.002 | 0.022 | [-0.04, 0.044] | -0.016 | 0.024 | [-0.062, 0.03] | ||

| Years of Education for Most Educated Parent | -0.052* | 0.022 | [-0.096, -0.008] | -0.037 | 0.026 | [-0.089, 0.014] | ||

Note.

p < .05

None of the pairwise country comparisons were statistically significant.

China significantly different from Colombia.

Sample Sizes: Mother-reported Externalizing and Internalizing (n=870); Father-reported Externalizing and Internalizing (n=629); Mother's behavior on Child-reported outcomes (n=867); Father's behavior on Child-reported outcomes (n=654).

Frequency of use of corporal punishment

Mothers' and fathers' reports of more frequent corporal punishment were related to more subsequent parent-reported child externalizing behavior, but not internalizing behavior. While the fixed relation between father-reported frequency of punishment and internalizing behavior was not statistically significant, there was evidence that the relation varies by country (χ2(7) = 17.12, p = 0.017); however, none of the 28 pairwise country comparisons were statistically significant. The relations between frequency of corporal punishment and child-reported outcomes were not statistically significant with one exception: fathers' reports of frequency of corporal punishment was positively and significantly related to child-reported relational aggression.

Based on father-reported data, a one standard deviation increase in grand mean-centered frequency of punishment was associated with a 0.178 standard deviation increase in grand mean-centered externalizing behavior scores (SE = 0.043, p = 0.000). Similarly, mother-reported data show that a one standard deviation increase in grand mean-centered frequency of punishment was associated with a 0.147 standard deviation increase in grand mean-centered externalizing behavior (SE = 0.041, p = 0.000). For child-reported relational aggression, based on father-reported data, a one standard deviation increase in grand mean-centered frequency of punishment was associated with a 0.048 standard deviation increase in grand mean-centered internalizing problem behavior score (SE = 0.024, p = 0.05). These relations did not vary by country.

Severity of corporal punishment

The severity of mothers' corporal punishment was not related to mothers' reports of externalizing or internalizing behavior. However, mothers' reports of more severe corporal punishment were associated with more child-reported aggression, whether non-physical, physical, or relational. A one standard deviation increase in grand mean-centered severity of punishment was associated with a 0.065 standard deviation increase in grand mean-centered non-physical aggression (SE = 0.02, p = 0.001); a one standard deviation increase in grand mean-centered severity of punishment was associated with a 0.057 standard deviation increase in grand mean-centered physical aggression (SE = 0.020, p = 0.005); and a one standard deviation increase in grand mean-centered severity of punishment was associated with a 0.059 standard deviation increase in grand mean-centered relational aggression (SE = 0.025, p = 0.018). Model fit did not improve when these relations are allowed to vary by county.

None of the fixed relations between fathers' report of the severity and problem behavior were statistically significant. However, for relational aggression, model fit improved when the relation varied by site (χ2(7) = 15.45, p = 0.031). A series of 28 pairwise tests comparing the relation between country sites was conducted, correcting for multiple post-hoc comparisons. The relation between father-reported severity of corporal punishment and relational aggression in China was statistically different from that in Colombia. The relation was negative and significant for China (β = -0.100, SE = 0.147, p = 0.035), whereas it was positive and significant in Colombia (β = 0.302, SE = 0.107, p = 0.005).

Justness of corporal punishment

None of the relations between justness and parent-reported problem behaviors were significant. By contrast, the relation between father-reported justness and both child-reported non-physical and physical aggression were significant: a one standard deviation increase in grand mean-centered justness of punishment was associated with a 0.065 standard deviation increase in grand mean-centered non-physical aggression (SE = 0.028, p = 0.019); a one standard deviation increase in grand mean-centered justness of punishment was associated with a 0.073 standard deviation increase in grand mean-centered physical aggression (SE = 0.027, p = 0.007). These relations did not vary by country.

None of the fixed relations between mother-reported justness of punishment and child-reported aggression were statistically significant. There was evidence that the relation between justness and physical aggression varies by country (χ2(7) = 21.84, p = 0.003); however, none of the 28 pairwise country comparisons were statistically significant.

In sum, there was strong evidence of a positive relation between parent-reported frequency of corporal punishment and parent-reported externalizing problems in children across all sites. There was also evidence of significant positive relations between mother-reported severity of punishment and child-reported aggression (non-physical, physical, and relational). Finally, there was evidence of a significant positive relation between father-reported justness and child-reported physical and non-physical aggression.

Moderation by Severity and Justness of Corporal Punishment

Two-way interactions between frequency and both the severity and justness of corporal punishment were added to the models. Table 3 provides the moderation results when all relations are held constant across sites, as well as the Chi-square test results assessing model fit when the moderation terms were allowed to vary by site.

Table 3. Models of Interactions between Frequency and Severity, and Frequency and Justness.

| Mother-Reported Punishment | Father-Reported Punishment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Std Est | SE | 95% CI | Variation by Country X2(7), (pval) | Std Est | SE | 95% CI | Variation by Country X2(7), (pval) | |

| Parent-report Externalizing (CBCL) | ||||||||

| Frequency of Corporal Punishment | 0.153* | 0.042 | [0.072, 0.235] | 0.18* | 0.043 | [0.094, 0.265] | ||

| Severity of Corporal Punishment | 0.07 | 0.045 | [-0.017, 0.158] | 0.048 | 0.056 | [-0.061, 0.158] | ||

| Justness of Corporal Punishment | -0.016 | 0.037 | [-0.089, 0.057] | -0.009 | 0.045 | [-0.098, 0.08] | ||

| Frequency* Severity | -0.005 | 0.037 | [-0.079, 0.068] | 7.264 (0.402) | 0.064 | 0.047 | [-0.028, 0.157] | 5.742 (0.57) |

| Frequency* Justness | 0.037 | 0.036 | [-0.034, 0.108] | 10.451 (0.164) | 0.049 | 0.046 | [-0.041, 0.138] | 16.668 (0.02) (a) |

| Severity* Justness | -0.007 | 0.033 | [-0.071, 0.057] | -0.005 | 0.036 | [-0.075, 0.065] | ||

| Indicator for Male Child | 0.09 | 0.065 | [-0.038, 0.218] | -0.059 | 0.082 | [-0.219, 0.101] | ||

| Child's Age | -0.041 | 0.035 | [-0.109, 0.028] | -0.03 | 0.045 | [-0.118, 0.059] | ||

| Family Income | -0.161* | 0.041 | [-0.241, -0.08] | -0.135* | 0.054 | [-0.241, -0.03] | ||

| Years of Education for Most Educated Parent | 0.04 | 0.038 | [-0.035, 0.115] | 0.095 | 0.05 | [-0.002, 0.192] | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Parent-report Internalizing (CBCL) | ||||||||

| Frequency of Corporal Punishment | 0.051 | 0.037 | [-0.021, 0.123] | 0.073 | 0.043 | [-0.011, 0.158] | ||

| Severity of Corporal Punishment | 0.043 | 0.042 | [-0.039, 0.124] | 0.073 | 0.055 | [-0.034, 0.181] | ||

| Justness of Corporal Punishment | -0.044 | 0.037 | [-0.117, 0.028] | -0.054 | 0.045 | [-0.141, 0.033] | ||

| Frequency* Severity | -0.026 | 0.035 | [-0.094, 0.043] | 1.522 (0.982) | -0.005 | 0.045 | [-0.093, 0.084] | 3.386 (0.847) |

| Frequency* Justness | -0.011 | 0.034 | [-0.079, 0.056] | 19.242 (0.007)+ | 0.034 | 0.037 | [-0.038, 0.106] | 15.395 (0.031) (b) |

| Severity* Justness | 0.05 | 0.032 | [-0.012, 0.112] | 0.022 | 0.036 | [-0.048, 0.092] | ||

| Indicator for Male Child | -0.042 | 0.061 | [-0.162, 0.078] | -0.127 | 0.075 | [-0.274, 0.019] | ||

| Child's Age | -0.009 | 0.035 | [-0.077, 0.059] | 0.002 | 0.038 | [-0.073, 0.077] | ||

| Family Income | -0.094* | 0.039 | [-0.171, -0.017] | -0.06 | 0.05 | [-0.158, 0.038] | ||

| Years of Education for Most Educated Parent | -0.047 | 0.037 | [-0.119, 0.025] | 0.066 | 0.043 | [-0.019, 0.15] | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Child-report Non-Physical Aggression (BFS) | ||||||||

| Frequency of Corporal Punishment | 0.042 | 0.024 | [-0.005, 0.09] | 0.026 | 0.026 | [-0.025, 0.077] | ||

| Severity of Corporal Punishment | 0.077* | 0.025 | [0.027, 0.126] | -0.033 | 0.026 | [-0.085, 0.019] | ||

| Justness of Corporal Punishment | 0.004 | 0.029 | [-0.052, 0.06] | 0.093* | 0.029 | [0.036, 0.15] | ||

| Frequency* Severity | 0.035 | 0.025 | [-0.015, 0.085] | 3.55 (0.83) | -0.005 | 0.031 | [-0.065, 0.055] | 6.157 (0.522) |

| Frequency* Justness | 0.054 | 0.031 | [-0.006, 0.115] | 12.107 (0.097) | 0.025 | 0.028 | [-0.031, 0.08] | 7.9 (0.341) |

| Severity* Justness | 0.002 | 0.019 | [-0.036, 0.039] | 0.051 | 0.028 | [-0.003, 0.105] | ||

| Indicator for Male Child | 0.133* | 0.034 | [0.066, 0.2] | 0.203* | 0.041 | [0.122, 0.283] | ||

| Child's Age | -0.006 | 0.027 | [-0.059, 0.048] | -0.001 | 0.037 | [-0.073, 0.071] | ||

| Family Income | 0.024 | 0.018 | [-0.011, 0.059] | 0.009 | 0.02 | [-0.031, 0.049] | ||

| Years of Education for Most Educated Parent | -0.023 | 0.022 | [-0.067, 0.02] | -0.023 | 0.026 | [-0.074, 0.029] | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Child-report Physical Aggression (BFS) | ||||||||

| Frequency of Corporal Punishment | 0.04 | 0.022 | [-0.003, 0.082] | 0.012 | 0.026 | [-0.039, 0.064] | ||

| Severity of Corporal Punishment | 0.072* | 0.023 | [0.028, 0.116] | 0.024 | 0.029 | [-0.033, 0.081] | ||

| Justness of Corporal Punishment | 0.047 | 0.025 | [-0.001, 0.096] | 0.084* | 0.029 | [0.028, 0.14] | ||

| Frequency* Severity | 0.033 | 0.021 | [-0.008, 0.074] | 5.515 (0.597) | -0.004 | 0.03 | [-0.063, 0.054] | 11.808 (0.107) |

| Frequency* Justness | 0.036 | 0.024 | [-0.011, 0.083] | 9.772 (0.202) | 0.012 | 0.027 | [-0.041, 0.065] | 6.708 (0.46) |

| Severity* Justness | 0.037* | 0.017 | [0.003, 0.071] | 0.03 | 0.024 | [-0.017, 0.078] | ||

| Indicator for Male Child | 0.176* | 0.035 | [0.108, 0.244] | 0.215* | 0.04 | [0.136, 0.293] | ||

| Child's Age | -0.076* | 0.026 | [-0.126, -0.026] | -0.029 | 0.029 | [-0.086, 0.028] | ||

| Family Income | -0.004 | 0.017 | [-0.038, 0.029] | -0.008 | 0.021 | [-0.05, 0.033] | ||

| Years of Education for Most Educated Parent | -0.034 | 0.019 | [-0.072, 0.004] | -0.041 | 0.023 | [-0.085, 0.004] | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Child-report Relational Aggression (BFS) | ||||||||

| Frequency of Corporal Punishment | 0.037 | 0.029 | [-0.02, 0.093] | 0.054* | 0.026 | [0.004, 0.105] | ||

| Severity of Corporal Punishment | 0.066* | 0.03 | [0.007, 0.125] | -0.012 | 0.026 | [-0.063, 0.039] | ||

| Justness of Corporal Punishment | 0.023 | 0.028 | [-0.032, 0.079] | 0.057* | 0.028 | [0.003, 0.112] | ||

| Frequency* Severity | 0.02 | 0.028 | [-0.036, 0.075] | 4.291 (0.746) | 0.018 | 0.03 | [-0.04, 0.077] | 6.911 (0.438) |

| Frequency* Justness | 0.019 | 0.028 | [-0.035, 0.074] | 10.589 (0.158) | 0.031 | 0.029 | [-0.027, 0.088] | 15.283 (0.033) + |

| Severity* Justness | 0.001 | 0.024 | [-0.047, 0.048] | 0.023 | 0.022 | [-0.02, 0.065] | ||

| Indicator for Male Child | 0.093* | 0.04 | [0.015, 0.171] | 0.072 | 0.044 | [-0.013, 0.158] | ||

| Child's Age | -0.021 | 0.026 | [-0.071, 0.03] | -0.014 | 0.03 | [-0.073, 0.045] | ||

| Family Income | 0.003 | 0.022 | [-0.039, 0.045] | -0.015 | 0.023 | [-0.061, 0.031] | ||

| Years of Education for Most Educated Parent | -0.05* | 0.022 | [-0.094, -0.007] | -0.034 | 0.026 | [-0.085, 0.016] | ||

Note.

p < .05

None of the pairwise culture comparisons were statistically significant.

Kenya significantly different from Thailand.

China significantly different from US.

Sample Sizes: Mother-reported Externalizing and Internalizing (n=870); Father-reported Externalizing and Internalizing (n=629); Mother's behavior on Child-reported outcomes (n=867); Father's behavior on Child-reported outcomes (n=654);

There were no statistically significant interactions between frequency and severity of punishment for any child behavior problem outcomes (parent- or child-reported). In addition, there were no statistically significant fixed interactions between frequency and justness of punishment; however, there was evidence that some of these interactions varied by site. Moderation by justness varied by country for mother-reported internalizing behavior (χ2(7) = 19.24, p = 0.007); however, none of the pairwise country comparisons were statistically significant. Model fit improved for 3 outcomes when moderation of father-reported behavior was allowed to vary by country. For father-reported externalizing problems (χ2(7) = 16.67, p = 0.02), the pairwise tests revealed that moderation by justness in Kenya was statistically different from that in Thailand. The moderation was negative and significant for Kenya (β = -0.185, SE = 0.086, p = 0.030), whereas it was positive and significant in Thailand (β = 0.327, SE = 0.084, p = 0.000). For internalizing problems (χ2(7) = 15.40, p = 0.031), the pairwise tests revealed that moderation by justness in China was statistically different from that in the US. The moderation was negative and but not significant for China (β = -0.192, SE = 0.116, p = 0.100), whereas it was positive and significant in the US (β = 0.389, SE = 0.131, p = 0.003). While fit improved for child-reported relational aggression when moderation by justmess was allowed to vary by site (χ2(7) = 15.28, p = 0.033), none of the pairwise country comparisons were statistically significant.

Overall, we did not find consistent evidence across reporters and sites that parent-reported severity or justness moderated the relation between frequency of corporal punishment and negative child behaviors. It is challenging to find significant moderating effects in non-experimental research as they tend to be small in effect size (Whisman & McClelland, 2005). Moreover, the degree to which the values within the 95% confidence intervals are grouped closely around the null determines how strongly we can conclude that the true population effect is close to the null value of zero (Hoenig & Heisey, 2001; O'Keefe, 2007). Our obtained CI ranges for both the interaction between frequency and severity as well as that between frequency and justness (Table 3) are relatively large, suggesting that, while a null interaction cannot be ruled out, we also are unable to conclude that there is no true interaction effect.

Discussion

The results show evidence of positive associations between the frequency of corporal punishment and parent-reported child externalizing behaviors in the subsequent year; there were no significant associations for internalizing behaviors. For child-reported outcomes, fathers' frequency of use of corporal punishment is positively associated with relational aggression. With respect to the hypothesized moderators of these associations, we did not find that the severity by which parents implement punishment functions to exacerbate, buffer, or otherwise change the relation between more frequent corporal punishment and problem behaviors. Likewise, there were no fixed interaction effects by justness, albeit there were some variations by country for father-reported justness and internalizing and externalizing child behaviors. The general null findings for moderation are thought-provoking, given the ongoing discourse on the nuances and variations in the effect of corporal punishment across situational, relational, and cultural contexts. The results seem to imply that frequent corporal punishment made “prudent” by low severity and high fairness (Baumrind, 1997), will not necessarily evince less negative (or more positive) child adjustment.

Other studies have found that forms of corporal punishment that were considered more severe or harsh (e.g. slapping or hitting with an object) were related to worse behavioral and emotional consequences in children (Lansford et al., 2012; Lapre & Marsee, 2016; Xing & Wang, 2013). Justness or reasonableness of punishment has also been found to be associated with psychological adjustment and antisocial behaviors (Rohner, Bourque, & Elordi, 1996; Straus & Mouradian, 1998). However, these studies have approached the question differently by combining these aspects of corporal punishment and/or using them as main predictors. The present analyses considered frequency, severity, and justness as separate variables, and investigated their interactions directly. This allowed us to determine whether frequency of corporal punishment manifests differential patterns or strengths of association with child adjustment as a function of how the punishment is implemented, i.e. the severity and justness. This study did not find such interaction effects.

To our knowledge, no other studies have investigated the interactions of different dimensions in the use of corporal punishment. The initial results reported here should therefore be validated in future research, more so because it is challenging to test interactions in non-experimental studies (McClelland & Judd, 1993). Issues of statistical power and the restricted range in the distributions of the interacting variables are plausible reasons for the null interaction results (Whisman & McClelland, 2005). The many countries involved in the international sample is clearly a strong point, but the necessary bias-corrections for the large number of multigroup and pairwise comparisons may have also rendered the analyses very conservative in detecting effects.

We also found that, consistent with the previously discussed studies, severity and justness evinced direct associations with child outcomes. Severity of mother-reported punishment was positively associated with child-reported aggression (whether non-physical, physical, or relational). Direct associations were also found between justness in fathers' use of punishment and child-reported physical and non-physical aggression, but in the opposite direction than is expected from the literature. The more that fathers reported their corporal punishment to be fair and deserved, the higher the aggressive behaviors reported by children.

It is unclear why the significant punishment correlates differ for the parent-reported and child-reported outcomes; i.e. frequency in the former and severity and justness in the latter. Discrepancies in parent and child reports is a recurrent issue in assessments of parent and child behaviors (Schneider, MacKenzie, Waldfogel, & Brooks-Gunn, 2015; De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005). Severity and justness of punishment may be more salient to children as these aspects have implications for their sense of security and autonomy (Grusec & Goodnow, 1994), and are more readily interpreted as reflecting parental rejection and hostility (Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997). As mothers in this sample more frequently implemented corporal punishment compared to the fathers (Lansford et al., 2010), the severity of mothers' punishment may be a particularly strong predictor of children's aggression. By contrast, it is the fathers' reports of justness in their use of punishment that is associated with children's aggression. This may be due to the father being conventionally considered as the ultimate arbiter or authority in the home, which may include decisions with respect to discipline (e.g., Chang, 2011). Future work can investigate how aspects of discipline (frequency, severity, justness; but also consistency, type of discipline, etc.) are associated with differential meanings and child outcomes as a function of parent gender.

Notwithstanding the different results for parent- and child-reported outcomes, it is evident that parental corporal punishment, whether measured in terms of frequency, severity, or justness, is associated with more child externalizing behaviors. Results with respect to frequency and severity in use of corporal punishment are consistent with the robust evidence linking parents' use of physical punishment and negative outcomes in children (Gershoff, 2002a; Gershoff & Grogan-Kaylor, 2016). Corporal punishment is linked to ineffective socialization efforts of parents and weakens internalization of parental values (Choe, Olson, & Sameroff, 2013; Gershoff, 2013; Grusec & Goodnow, 1994). Physical forms of discipline model aggression as an appropriate response to conflict or aversive behaviors, thereby increasing the likelihood that children will employ similarly aggressive strategies in other contexts (Simons & Wurtele, 2010). The experience of physical pain and the ensuing emotional arousal in children interfere with processing messages that parents mean to convey; moreover, it induces fear and threat that precipitate avoidance responses, if not hostility towards the parent (Grusec & Goodnow, 1994; Vittrup & Holden, 2010).

For justness, fathers' reports of fairness and deservedness in their use of corporal punishment is positively associated with children's reports of their aggressive behaviors. This is counter to what is expected and may reflect self-serving bias on the part of parents who may construct beliefs in order to justify their behaviors, which may include harsh or frequent punishment (Grusec, Rudy, & Martini, 1997). Children's perceptions of the justness or fairness of their parents' discipline, rather than parents' perceptions, may be more pertinent predictors of children's behaviors (Gershoff, 2002a; Grusec & Goodnow, 1994).

It is notable that, with few exceptions, the aforementioned relations were demonstrated across the 8 country groups, suggesting that the generally detrimental consequences of corporal punishment for children apply across diverse cultural contexts. It was only in the moderating effect of father-reported justness on the relation between frequency of punishment and externalizing and internalizing outcomes that some differences reliably emerged. For externalizing behaviors, the interaction was negative in the Kenyan group, whereas it was positive for the Thailand group; for internalizing behaviors, the interaction was negative but non-significant for the China group but positive for the US respondents. However, these differences were few in comparison with the number of between-country comparisons made. Future work should validate emergent group-specific differences with larger and more representative samples.

Limitations

A main limitation of the study is that a single instrument measured frequency, severity, and justness of corporal punishment as self-reported by mothers and fathers. Moreover, items asked about physical punishment in general, and the construct was not defined except via the examples “spank, slap, or pinch” in the instructions. This is a fairly common problem that has plagued the corporal punishment literature, in that informants are left to subjectively define what constitutes “punishment,” as well as subjectively assess severity or harshness (Gershoff, 2002a). Parents may vary in their judgments of what qualifies as physical punishment, or what constitutes “very hard” physical punishment. Multiple sources of corporal punishment data, such as child reports and the reports of other caregivers or family members can correct self-report bias and shared source variance.

The analyses used reports of children's internalizing and externalizing behaviors that were collected one year after the corporal punishment data, providing some support to the temporal inference that the child behaviors followed parental punishment. However, the data were correlational and causal interpretations cannot be assumed. Despite the robust evidence supporting parent-to-child effects in studies of corporal punishment, the parent-child relationship is transactional and child behavior problems have also been shown to elicit parental punishment (e.g., Berlin et al., 2009; Choe, Olson, & Sameroff, 2013; Maguire-Jack, Gromoske, & Berger, 2012).

Conclusions

This study mainly sought to address the question of whether severity and justness in the use of corporal punishment moderates the association between frequency of punishment and child externalizing and internalizing behaviors. Across groups from 8 countries, and as reported by mothers and fathers, there was no firm evidence that severity and justness interacted with frequency to buffer, exacerbate, or modify the general result that higher frequency of corporal punishment is associated with higher externalizing behaviors. However, mother-reported severity and father-reported justness of corporal punishment, rather than frequency, were significantly related to child-reported aggression.

Whether the manner by which parents implement corporal punishment can moderate the effects of its use is an important question that remains to be settled. Further research is necessary to validate the absence of moderating effects in this study, given the challenges inherent in testing interactions in non-experimental designs. Still, the findings are suggestive and consequential, especially given the diverse international sample of children, mothers, and fathers. Across cultural groups, more use of corporal punishment is associated with more externalizing child behaviors, and neither severity nor justness moderated these associations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research has been funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant RO1-HD054805 and Fogarty International Center grant RO3-TW008141. This research also was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH/NICHD. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or NICHD.

Contributor Information

Liane Peña Alampay, Ateneo de Manila University, Philippines.

Jennifer Godwin, Center for Child and Family Policy, Duke University, USA.

Jennifer E. Lansford, Center for Child and Family Policy, Duke University, USA

Anna Silvia Bombi, Universita di Roma La Sapienza, Italy.

Marc H. Bornstein, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, MD, USA

Lei Chang, University of Macau, China.

Kirby Deater-Deckard, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, USA.

Laura Di Giunta, Universita di Roma La Sapienza, Italy.

Kenneth A. Dodge, Center for Child and Family Policy, Duke University, USA

Patrick S. Malone, Center for Child and Family Policy, Duke University, USA

Paul Oburu, Maseno University, Kenya.

Concetta Pastorelli, Universita di Roma La Sapienza, Italy.

Ann T. Skinner, Center for Child and Family Policy, Duke University, USA

Emma Sorbring, University West, Trollhättan, Sweden.

Sombat Tapanya, Chiang Mai University, Thailand.

Liliana M. Uribe Tirado, Universidad San Buenaventura, Colombia

Arnaldo Zelli, University of Rome Foro Italico, Italy.

Suha Al-Hassan, Hashemite University, Jordan, and Emirates College for Advanced Education, UAE.

Dario Bacchini, Second University of Naples, Italy.

References

- Achenbach TM. Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL 14 – 18, YSR, and TRF profiles. Burlington: Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Necessary distinctions. Psychological Inquiry. 1997;8:176–182. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D, Larzelere RE, Owens EB. Effects of preschool parents' power assertive patterns and practices on adolescent development. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2010;10:157–201. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Ispa JM, Fine MA, Malone PS, Brooks-Gunn J, Brady-Smith C, et al. Bai Y. Correlates and consequences of spanking and verbal punishment for low-income White, African American, and Mexican American toddlers. Child Development. 2009;80(5):1403–1420. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01341.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Chen BB, Ji LQ. Parenting attributions and attitudes of mothers and fathers in China. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2011;11:102–115. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2011.585553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe DE, Olson SL, Sameroff AJ. The interplay of externalizing problems and physical and inductive discipline during childhood. Developmental Psychology. 2013;49(11):2029–2039. doi: 10.1037/a0032054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Bigbee MA. Relational and overt forms or peer victimization: A multiinformant approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:337–347. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA. Externalizing behavior problems and discipline revisited: Nonlinear effects and variation by culture, context, and gender. Psychological Inquiry. 1997;8(3):161–175. [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Kazdin AE. Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: A critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131(4):483–509. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Danish SJ, Howard CW. Relationship between drug use and other problem behaviors in urban adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:705–712. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.5.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson CJ. Spanking, corporal punishment, and negative long-term outcomes: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Clinical Psychology Review. 2013;33:196–208. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German M, Gonzalez NA, McClain DB, Dumka L, Millsap R. Maternal warmth moderates the link between harsh discipline and later externalizing behaviors for Mexican American adolescents. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2013;13(3):169–177. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2013.756353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET. Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin. 2002a;128(4):539–579. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET. Corporal punishment, physical abuse, and the burden of proof: Reply to Baumrind, Larzelere, and Cowan (2002), Holden (2002), and Parke (2002) Psychological Bulletin. 2002b;128(4):602–611. [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET. Spanking and child development: We know enough now to stop hitting our children. Child Development Perspectives. 2013;7(3):133–137. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET, Bitensky SH. The case against corporal punishment of children: Converging evidence from social science research and international human rights law and implications for U.S. public policy. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. 2007;13(4):231–272. [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET, Lansford JE, Sexton HR, Davis-Kean P, Sameroff A. Longitudinal links between spanking and children's externalizing behaviors in a national sample of White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian American families. Child Development. 2012;83(3):838–843. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET, Grogan-Kaylor A. Spanking and child outcomes: Old controversies and new meta-analyses. Journal of Family Psychology. 2016 doi: 10.1037/fam0000191. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/fam0000191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Grusec JE, Goodnow JJ. Impact of parental discipline methods on the child's internalization of values: A reconceptualization of current points of view. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30(1):4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Grusec J, Rudy D, Martini T. Parenting cognitions and child outcomes: An overview and implications for children's internalization of values. In: Grusec J, Kuczynski L, editors. Parenting and children's internalization of values: A handbook of contemporary theory. NY: Wiley; 1997. pp. 259–282. [Google Scholar]

- Hoenig JM, Heisey DM. The abuse of power: The pervasive fallacy of power calculations for data analysis. The American Statistician. 2001;55(1):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 1979;6(2):65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Chang L, Dodge KA, Malone PS, Oburu P, Palmerus K, et al. Quinn N. Physical discipline and children's adjustment: Cultural normativeness as a moderator. Child Development. 2005;76(6):1234–1246. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00847.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Alampay L, Bacchini D, Bombi AS, Bornstein MH, Chang L, et al. Zelli A. Corporal punishment of children in nine countries as a function of child gender and parent gender. International Journal of Pediatrics. 2010;2010:1–12. doi: 10.1155/2010/672780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Deater-Deckard K. Childrearing discipline and violence in developing countries. Child Development. 2012;83:62–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapré GE, Marsee MA. The role of race in the association between corporal punishment and externalizing problems: Does punishment severity matter? Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2016;25(2):432–441. [Google Scholar]

- Larzelere RE, Baumrind D. Are spanking injunctions scientifically supported? Law and Contemporary Problems. 2010;73(2):57–87. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie MJ, Nicklas E, Brooks-Gunn J, Waldfogel J. Spanking and children's externalizing behavior across the first decade of life: Evidence for transactional processes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2015;44(3):658–669. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0114-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire-Jack K, Gromoske AN, Berger LM. Spanking and child development during the first 5 years of life. Child Development. 2012;83(6):1960–1977. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01820.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe KM, Mechammil M, Yeh M, Zerr A. Self-reported parenting of clinic-referred and non-referred Mexican American mothers of young children. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2016;25(2):442–451. doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0238-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland GH, Judd CM. Statistical difficulties of detecting interactions and moderator effects. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114(2):376–390. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.2.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC, Smith J. Physical discipline and behavior problems in African American, European American and Latino children: Emotional support as a moderator. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2002;64:40–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00040.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O'Keefe DJ. Post hoc power, observed power, a priori power, retrospective power, prospective power, achieved power: Sorting out appropriate uses of statistical power analyses. Communication Methods and Measures. 2007;1(4):291–299. [Google Scholar]

- Orpinas P, Frankowski R. The aggression scale: A self-report measure of aggressive behavior for young adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2001;21:50–67. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Etiology and treatment of child and adolescent antisocial behavior. The Behavior Analyst Today. 2002;3(2):133–144. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0099971. [Google Scholar]

- Rohner RP, Bourque SL, Elordi CA. Children's perceptions of corporal punishment, caretaker acceptance, and psychological adjustment in a poor, biracial Southern community. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1996;58:842–852. [Google Scholar]

- Rohner RP, Khaleque A. Handbook for the study of parental acceptance and rejection. 4th. Storrs, CT: University of Connecticut; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A. Scaled and adjusted restricted tests in multi-sample analysis of moment structures. In: Heijmans RDH, Pollock DSG, Satorra A, editors. Innovations in multivariate statistical analysis A Festschrift for Heinz Neudecker. London: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2000. pp. 233–247. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider W, MacKenzie M, Waldfogel J, Brooks-Gunn J. Parent and child reporting of corporal punishment: New evidence from the fragile families and child wellbeing study. Child Indicators Research. 2015;8(2):347–358. doi: 10.1007/s12187-014-9258-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons DA, Wurtele SK. Relationships between parents' use of corporal punishment and their children's endorsement of spanking and hitting other children. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34:639–646. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Mouradian VE. Impulsive corporal punishment by mothers and antisocial behavior and impulsiveness of children. Behavioral Sciences and the Law. 1998;16:353–374. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0798(199822)16:3<353::aid-bsl313>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Stewart JH. Corporal punishment by American parents: National data on prevalence, chronicity, severity, and duration, in relation to child and family characteristics. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1999;2(2):55–70. doi: 10.1023/a:1021891529770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vittrup B, Holden GW. Children's assessments of corporal punishment and other disciplinary practices: The role of age, race, SES, and exposure to spanking. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2010;31:211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA, McClelland GH. Designing, testing, and interpreting interactions and moderator effects in family research. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19(1):111–120. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing X, Wang M. Sex differences in the reciprocal relationships between mild and severe corporal punishment and children's internalizing problem behavior in a Chinese sample. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2013;34:9–16. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2015 2015 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.