Abstract

Microcrystalline uniformly 13C,15N-enriched yeast triosephosphate isomerase (TIM) is sequentially assigned by high-resolution solid-state NMR (SSNMR). Assignments are based on intraresidue and interresidue correlations, using dipolar polarization transfer methods, and guided by solution NMR assignments of the same protein. We obtained information on most of the active-site residues involved in chemistry, including some that were not reported in a previous solution NMR study, such as the side-chain carbons of His95. Chemical shift differences comparing the microcrystalline environment to the aqueous environment appear to be mainly due to crystal packing interactions. Site-specific perturbations of the enzyme's chemical shifts upon ligand binding are studied by SSNMR for the first time. These changes monitor proteinwide conformational adjustment upon ligand binding, including many of the sites probed by solution NMR and X-ray studies. Changes in Gln119, Ala163, and Gly210 were observed in our SSNMR studies, but were not reported in solution NMR studies (chicken or yeast). These studies identify a number of new sites with particularly clear markers for ligand binding, paving the way for future studies of triosephosphate isomerase dynamics and mechanism.

Keywords: triosephosphate isomerase, solid-state NMR, sequential assignment, crystal packing, conformational change

Introduction

Triosephosphate isomerase (TIM) catalyzes the central reaction in the glycolytic pathway—the reversible interconversion of dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate—while suppressing the production of methyl glyoxal by phosphate elimination side reaction.1 Studies of the mechanism support the existence of a chemical intermediate, the enediol(ate) of DHAP. As a catalyst, TIM has often been said to have achieved evolutionary perfection, and it has been extensively characterized with numerous structural,2 mechanistic,3 and kinetic4–6 studies.

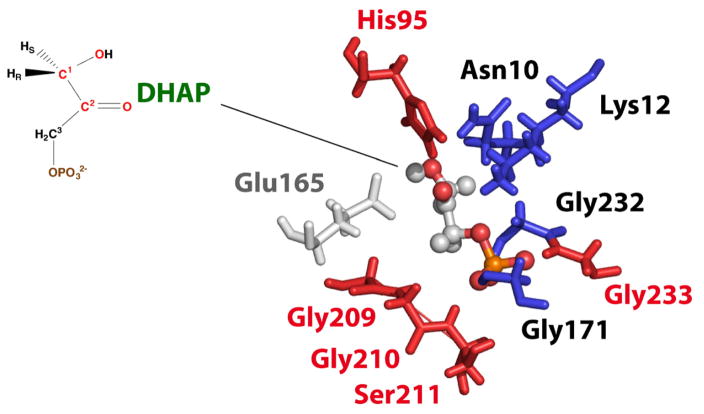

A dramatic conformational change in TIM induces proton redistribution in the enzyme's active site. The ligand-induced structural change was first observed in chicken TIM;4 subsequently, key players involved in catalysis were extensively explored by X-ray crystallography5–8 and site-specific mutations.5–9 In high-resolution crystal structures of unligated TIM, loop 6 was observed in the so-called open form;10,11 when the protein is ligated either by the substrate or by substrate analogues, loop 6 is usually closed12 (although some exceptions have been found13–16). Comparison of the open and closed conformations of chicken, yeast, and trypanosomal TIM structures indicates that the various open forms are identical with each other, and that the closed forms of yeast and trypanosomal TIMs are essentially indistinguishable from each other.17 Closure of loop 6 on the active site organizes the side chains of Asn10, Lys12, His95, Ser96, Glu97, Glu165, and Ser211, and the backbones of Gly232, Gly233, and Gly171 to interact with and surround the substrate, thus accelerating the reaction by 10 orders of magnitude. Simultaneously, its closed conformation protects the substrate from contact with bulk water, thereby presumably preventing the deleterious elimination of phosphate from the intermediate.5

High-resolution NMR is a very sensitive tool used for detecting conformational dynamics at the atomic level. Isotropic chemical shift is sensitive to local structure, especially torsional states of the chain and side chains, and also to electrostatics, solvent exposure, and ligand binding. Previous solution NMR studies have reported most backbone and side-chain assignments for unligated and D-glycerol 3-phosphate (D-G3P) (or 2-phosphoglycolate)-ligated yeast18 and chicken19 TIMs. In yeast TIM, G3P-induced chemical shift perturbations were observed for Asn10, His95, Ser100, Glu129-Glu133, Val167-Ala186, Asn213, and Leu230-Leu126 residues that either are near the ligand or have direct contact with the ligand, with some key residues, including Glu165, Gly210, Ser211, and Ala212, missing from the data set. 2-Phosphoglycolate binding to chicken TIM also shows significant chemical shift perturbations on the residues that are close to the ligand or interact with the ligand. These chemical shift perturbations offered an opportunity for studying the dynamics of binding and conformational exchange in a site-specific fashion.

Solid-state NMR (SSNMR) is a powerful tool that complements other biophysical methods in studying the structure, mechanism, and dynamics of bio-molecules. Because of the ability to vary temperature, the Michaelis complex can be stabilized for SSNMR studies, allowing access to issues of great chemical interest. Also, because of the ability to vary the temperature broadly, SSNMR methods might have access to key catalytic sites, including ones that are invisible in solution NMR studies due to extensive line broadening from chemical exchange. The microcrystalline samples employed in SSNMR are very similar to the crystals used in X-ray crystallography, allowing for direct comparisons between the X-ray structure and the SSNMR data. For all these reasons, SSNMR spectroscopy has the potential to reveal novel mechanistic aspects.

To date, SSNMR studies of TIM have offered a limited view of the active site because they required site-specific isotopic enrichment of the unique sites. For example, to probe loop dynamics, we used isotopic enrichment of a unique tryptophan residue in a fully active mutant of the enzyme, namely, Trp168.20 SSNMR studies of many of the key active-site catalytic players have been limited by our inability to carry out site-specific enrichment. For a more complete access to dynamic and chemical information, the more direct approach is to assign the signals for an extensively or uniformly isotopically enriched sample. Assignments by SSNMR have been greatly facilitated by the development of magic-angle spinning21 and sequential assignment protocols;22,23 for proteins as large as TIM, however, chemical shift assignments are still, by no means, routine. In this report, we present site-specific SSNMR sequential assignments of uniformly 13C,15N-enriched microcrystalline yeast TIM, as guided by the published solution NMR assignment.18 We compare chemical shifts in solution versus chemical shifts in microcrystalline form. Subsequently, the substrate analogue D-G3P was cocrystallized with the enzyme, and chemical shift perturbations were detected. These observations provide a number of markers for further site-specific dynamic studies and active-site chemical players, and thereby open the possibility of unveiling the TIM catalytic mechanism.

Results and Discussion

Sequential assignment strategy and chemical shift assignments

Yeast TIM, a 247-residue protein with a molecular mass of 26 kDa, is one of the largest systems studied by SSNMR. Most resonances for backbone N, Cα, and CO, and for side-chain Cβ have been assigned by solution NMR (BioMagResBank 7216),18 which were used to help identify SSNMR assignments. Backbone and side-chain sequential SSNMR assignments (see Supplementary Table 1) were based on five spectra: two-dimensional (2D) homonuclear 13C–13C spectrum,24 2D heteronuclear NCA and NCO spectra,25,26 and three-dimensional (3D) NCACX and NCOCX spectra combining the two experiments for the purpose of sequential assignment, as we have done previously.22 NCACX, NCOCX, NCA, and NCO spectra contained backbone correlations. The NCACX, NCOCX, and 13C–13C spectra were used for side-chain assignments (for details on pulse sequences, see Materials and Methods).

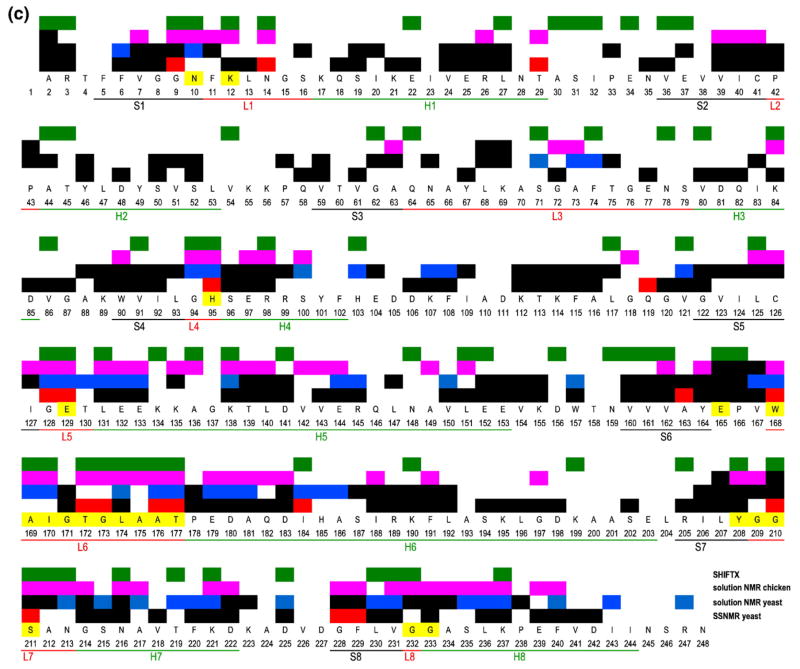

Our sequential assignment strategy was similar to our previously published protocols for “backbone walks.” 22,23,27 In addition, solution assignments were displayed with the program CARA (Computer-Aided Resonance Assignment),28 which allowed convenient comparisons of resonance correlations for SSNMR and solution NMR, and thereby gave us leading hypotheses for assignments in many cases. For regions with clear solid solution perturbations or that are highly congested, a spectra combination of 2D and 3D SSNMR data was used. For example, for the resonances in Thr60, correlations of Cα Cβ , Cα Cγ2, Cβ Cγ2, CαCO, and Cβ CO in 13C–13C 2D; NCα Cβ and NCα CO in NCACX 3D; and Thr60N-Val59CO-Val59Cα, Val61N-Thr60CO-Thr60Cα, and Val61N-Thr60CO-Thr60Cβ in NCOCX 3D were all found and used to make the resonance assignments of the backbone and side-chain atoms of Thr60. Consequently, a number of new resonance assignments not reported by solution NMR were discovered. Figure 1 summarizes these new resonance assignments in the solid state, as well as all the interresidue and intraresidue correlations found. In the 2D homonuclear and heteronuclear spectra, the average linewidth of resonance peaks is 0.3 ppm in the carbon dimension and 0.5 ppm in the nitrogen dimension.

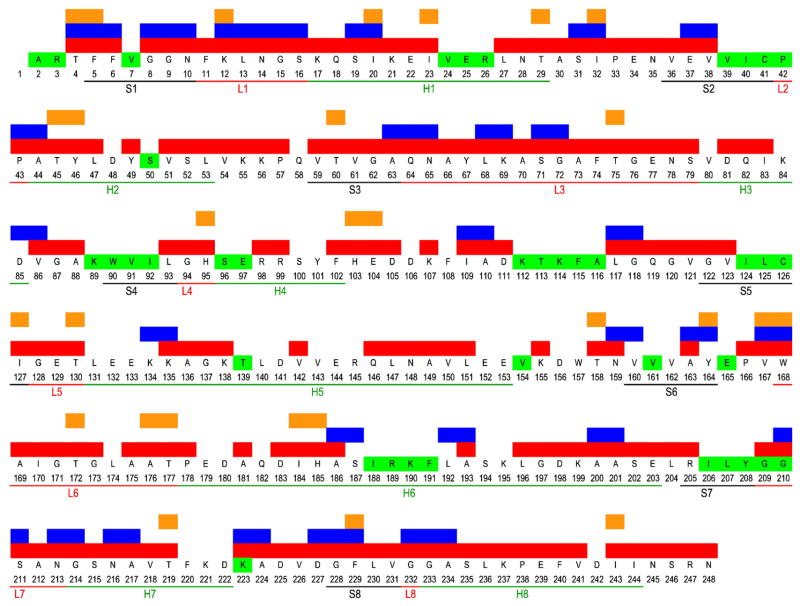

Fig. 1.

Interresidue and intraresidue correlations employed in SSNMR assignments. Residues in red have intraresidue correlations available; residues in blue have interresidue correlations available; residues in orange have intraresidue or interresidue correlations independent of solution NMR available; residues in green are the ones unassigned in solution NMR.

Comparison of solid-state and solution NMR assignments

There has been great interest29–31 in studying the differences and similarities of chemical shifts between the solution state and the crystalline state. Cole and Torchia were the first to report a close agreement in nitrogen chemical shifts between solution-state staphylococcal nuclease and crystalline staphylococcal nuclease.31 In another study, Detken et al. reported a remarkable agreement in backbone and aliphatic side-chain assignments for a 10-residue molecule, antamanide.30 The first nearly fully assigned protein by SSNMR, the SH3 domain of α-spectrin,32 exhibited isotropic chemical shifts from solution NMR and SSNMR that were in overall agreement, with the exception of a few sites.33 Spectra of the Bacillus subtilis protein Crh in solution34 and in solid state35 exhibited large chemical shift differences that were attributed to the dimerization of Crh.35 Ubiqutin was also assigned by solution NMR36 and SSNMR.22,23 The two samples differed in pH and buffer conditions, and residues with the greatest chemical shift deviations were generally polar or solvent exposed. Crystal packing interactions are also thought to affect chemical shifts.22,23 Franks et al. assigned GB1 by SSNMR,29 and crystal packing interactions were proposed to influence rotameric states and intermolecular interactions between β 2 and β 3 strands, accounting for chemical shift differences with the solution state. Most reports to date show general agreement between solution state and solid state, where perturbations are generally attributed to differences in sample preparation, solvent exposure, or crystal packing interactions.

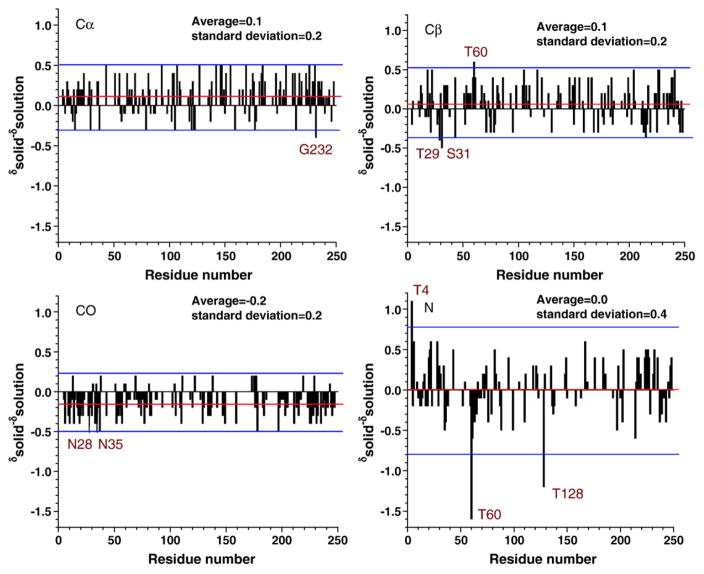

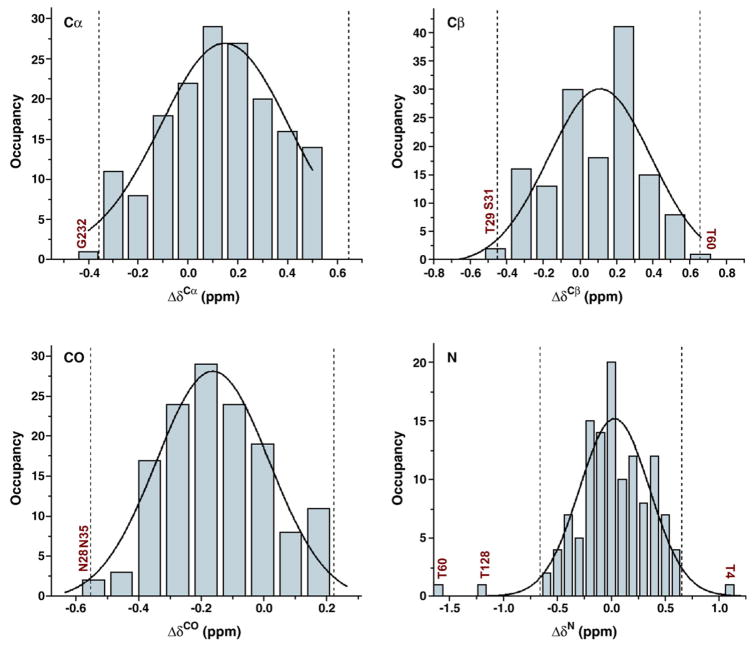

Figure 2 plots the crystal-versus-solution differences in chemical shifts for TIM, which are defined as . The mean of the chemical shift differences is near zero, and the RMSD is about 0.5 ppm, demonstrating a very good overall agreement between solution-state and solid-state shifts. Outliers were identified by constructing histograms of chemical shift differences for Cα, Cβ , CO, and N (Fig. 3). The histograms contain 166 resonances for Cα, 144 resonances for Cβ , 137 resonances for CO, and 123 resonances for N. Histograms were fitted with Gaussian curves, and outliers were defined as residues that were outside ±1.96σ from the mean (i.e., outside of the 95% confidence interval). All outliers are listed in Table 1.

Fig. 2.

Chemical shift differences comparing chemical shifts for yeast TIM in solution versus chemical shifts for yeast TIM in the microcrystalline solid state. The mean difference (average of solid-solution) and the standard deviation in this difference (σ) are given for each atom type: 0.1±0.2 ppm for Cα, 0.1±0.2 ppm for Cβ , −0.2±0.2 ppm for CO, and 0.0 ±0.4 ppm for N. In general, a close agreement between solution NMR and SSNMR assignments was observed. A handful of sites with chemical shift perturbations at least 1.96σ away from the mean (red lines) are defined by the blue lines: Gly232 for Cα; Thr29, Ser31, and Thr60 for Cβ ; Asn28 and Asn35 for CO; and Thr4, Thr60, and Thr128 for N.

Fig. 3.

Histograms are presented for chemical shift differences in the solid-state and solution NMR assignments for Cα, Cβ , CO, and N. They contain 166 observations for Cα, 144 observations for Cβ , 137 observations for CO, and 123 observations for N. Continuous lines are the best-fitting Gaussian curves. Best-fit values of expected value and standard deviation were found to be 0.15±0.02 and 0.26±0.07 for Cα, 0.11±0.05 and 0.28±0.07 for Cβ , −0.16±0.02 and 0.18±0.03 for CO, and 0.03±0.03 and 0.33±0.03 for N. Broken lines indicate sites 1.96σaway from the mean. Together with Fig. 2, the histograms show an overall agreement between solution NMR and SSNMR assignments, and point out the outliers: Gly232 for Cα; Thr29, Ser31, and Thr60 for Cβ ; Asn28 and Asn35 for CO; and Thr4, Thr60, and Thr128 for N.

Table 1.

Residues that have chemical shift perturbations between solid-state and solution NMR assignments

| Residue | Thr4 | Asn28 | Thr29 | Ser31 | Asn35 | Thr60 | Gly128 | Gly232 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2° structure | Sheet 1 | Loop after helix 1 | Loop after helix 1 | Loop after helix 1 | Loop after helix 1 | Sheet 3 | Loop 5 | Loop 8 |

| ΔΔγ(ppm)a | 1.1 (N) | −0.5 (CO) | −0.4 (Cβ ) | −0.5 (Cβ ) | −0.5 (CO) | 0.6 (Cβ ); −1.6 (N) | −1.2 (N) | −0.4 (Cα) |

The chemical shift difference is calculated relative to the mean in the Gaussian curves.

Any difference could be due to the solvent conditions, in that the conditions are somewhat different. In this regard, we were confident that the enzyme we studied here was fully competent under the experimental conditions, both in solution (the mother liquor) and in the crystalline (or precipitated) form. Prior solution NMR studies were carried out at pH 5.9 in a sodium acetate buffer,18 whereas the SSNMR samples studied here were prepared at pH 6.8 in a Tris buffer [with polyethylene glycol (PEG) precipitation]. The difference in pH could produce changes in local charge distributions, consistent with the fact that TIM has a slightly different activity between these two pH values.37 Furthermore, polar surface residues may form intermolecular contacts not observed in monodispersed TIM in solution, leading to chemical shift changes in these residues.

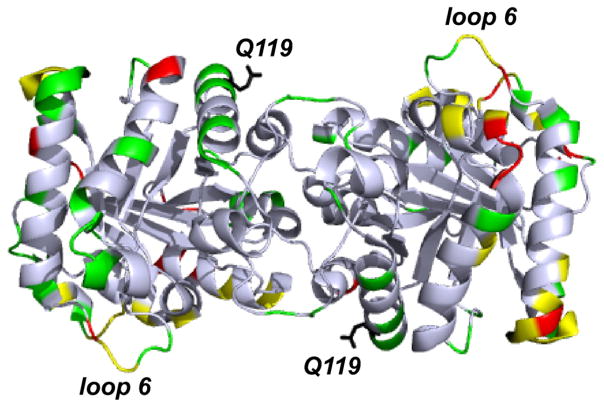

Chemical shift differences comparing solution state and solid state could also be due to crystal contacts. Based on the Protein Data Bank (PDB) structure for the wild-type yeast TIM (PDB ID 1I4538), the crystal packing structure was mapped with the program O.39 We chose the 1I45 structure because it matches the crystallization conditions used in this work.38 The crystal contacts were calculated with ACCEPT-NMR (Automated Crystal Contact Extrapolation/Prediction Toolkit for NMR).40 They were defined as all residues with at least one atom within 5 Å of an atom of a residue in an adjacent molecule in the crystal (see Supplementary Table 3). Indeed, many of the perturbed chemical shifts are at or near crystal contacts. Among the residues that have chemical shift perturbations between solution NMR and SSNMR assignments (Fig. 4), Thr4 in the N-terminus, Asn28, Thr29, Ser31, and Asn35 in the small loop after helix 1 are all involved in direct crystal contacts for chain B in the microcrystalline condition. Thr60 is located in a small β-strand (sheet 3) in the core of the bundle, with its side-chain exposed to the solvent. Although it does not have direct crystal contacts with other subunits, neighboring residues Lys55 and Lys56 are involved in crystal contacts.

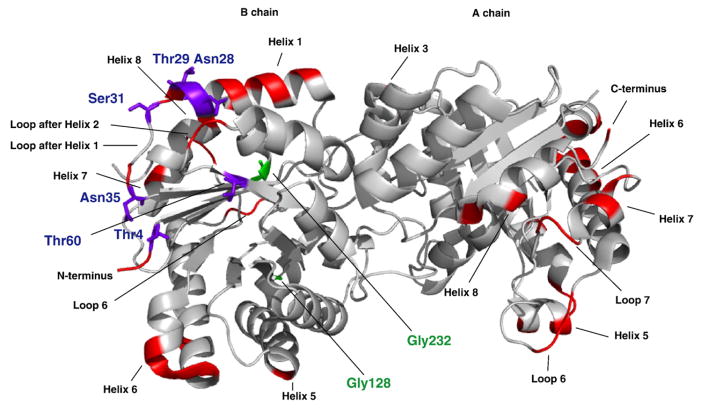

Fig. 4.

The relation between crystal packing and chemical shift perturbations between solution NMR and SSNMR assignments. The residues that have crystal contacts (red) are mapped onto a dimer of yeast TIM (PDB ID 1I451). The ones that have chemical shift perturbations and are also on or near crystal contacts (Thr4, Asn28, Thr29, Ser31, Asn35, and Thr60) are labeled in purple; the ones that have chemical shift perturbations but are not in crystal contacts (Gly128 and Gly232) are labeled in green. Most perturbed residues (six of eight) are on or near crystal contacts.

Active-site residues detected by SSNMR, not by solution NMR

The three residues Lys12, His95, and Glu165 are near the active site and are known to be critical for the chemistry of proton transfer in the substrate (Fig. 5).10,41 Remarkably, two of these residues, Lys12 and His95, have been observed and assigned in our SSNMR spectra. The anionic phosphate moiety of the substrate is stabilized by hydrogen bonds to Gly209, Gly210, Ser211, Gly171, Gly232, and Gly233. These are all identified in our studies; this is noteworthy since residues Gly209, Gly210, and Gly233 are absent from the solution assignments.

Fig. 5.

The active site of TIM bound with the substrate (PDB ID 1NEY2). Residues labeled in red are the ones observed in SSNMR but not in solution NMR; residues labeled in blue are the ones observed in both; residues labeled in gray are not observed in either.

Although our study reports many new resonance assignments, some residues are absent—most notably Glu165, which is of particular interest for studying the mechanism and is missing in both the solution data set and the solid-state data set. This residue is responsible for the initiation and presumably also the termination of TIM catalysis, and it is involved in one of the postulated proton transfer pathways mentioned before.42 Either the Glu165 cross-peaks are occluded by other peaks with similar chemical shifts or the peak intensities are attenuated by motion. Multidimensional spectra at higher resolution, selective labeling schemes, lower temperature studies, or a tighter inhibitor are the different avenues being pursued to further characterize this important site.

Conformational changes in ligand binding as detected by SSNMR

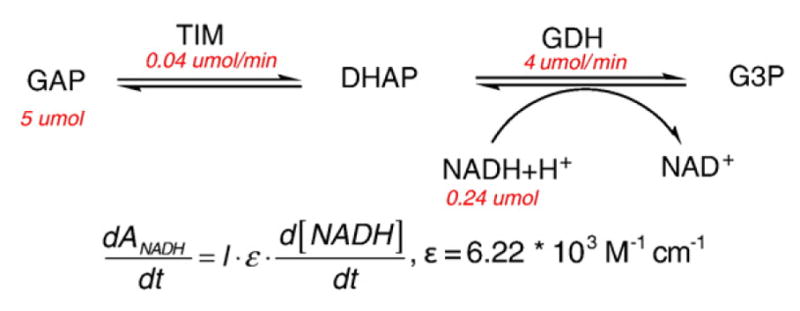

The study of TIM with the native substrate is complicated by the rapid elimination of phosphate, which produces a highly reactive methylglyoxal byproduct at temperatures above 0 °C.43 Therefore, we have characterized the binding of a substrate analogue D-G3P, which has a structure and a binding affinity similar to those of the native substrate DHAP: The steady-state parameters for baker's yeast TIM expressed in Escherichia coli at 30 °C are Ki =1.4±0.3 mM for D-G3P and Km =1.4± 0.1 mM for the substrate.44 The TIM–G3P complex is also much more stable than the TIM–DHAP complex at temperatures above 0 °C.

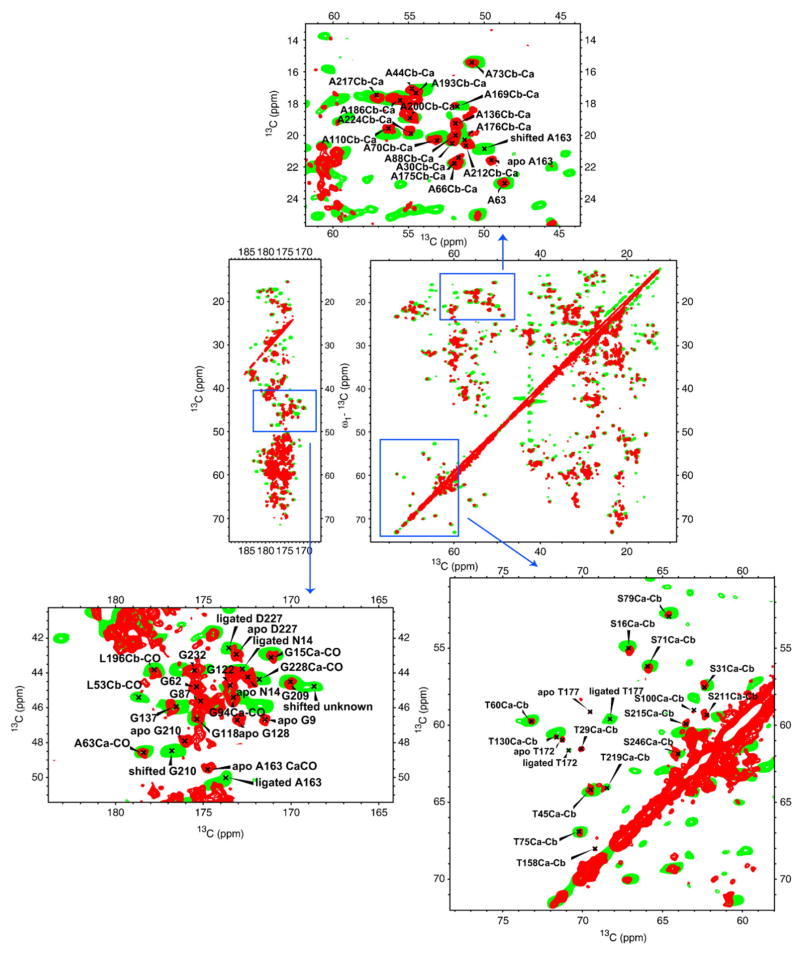

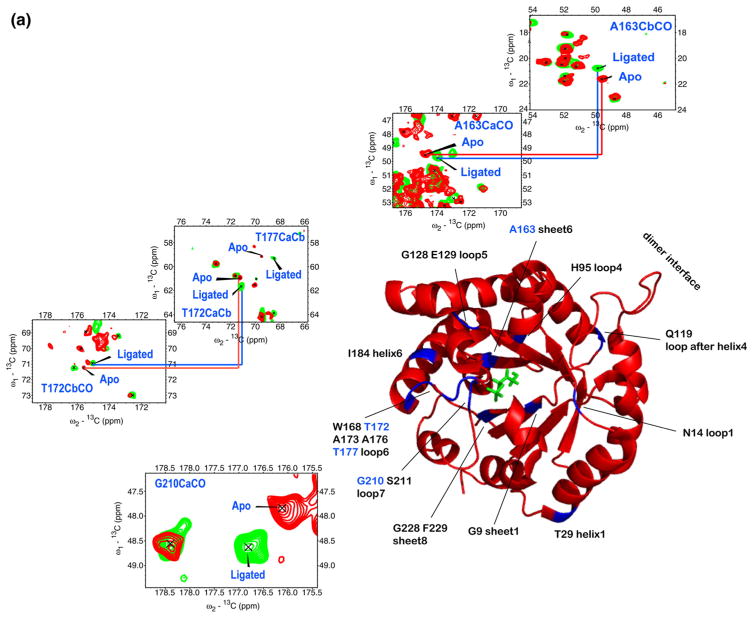

Partial assignment of NMR signals for the G3P-ligated crystalline enzyme was achieved with homonuclear 13C–13C 2D spectra and heteronuclear 15N–13CA,15N–13CO 2D spectra (see Supplementary Table 2). Figure 6 shows an overlay of the homonuclear 13C–13C 2D spectra of apo TIM and ligated TIM. The differences in chemical shifts between the bound form and the free form are plotted in histograms for Cα, Cβ , CO, and N, and were fitted using a Gaussian function. We defined outliers as all residues that lay outside of the 95% confidence interval (±1.96σ) from the mean. All residues that are involved in chemical shift perturbations upon binding are mapped in Fig. 7a. They include Gly9, Asn14, Thr29, His95, Gln119, Gly128, Glu129, Ala163, Trp168, Thr172, Gly173, Ala176, Thr177, Ile184, Gly210, Ser211, Gly228, and Phe229. Figure 7b shows the residues with chemical shift perturbations by solution NMR.18 Consistent with solution NMR data, our assignments show that the residues closest to the ligand have large chemical shift changes upon ligand binding.18,19 Their roles are discussed in more detail below.

Fig. 6.

The overlay of the 13C–13C 2D spectra of apo TIM (red) and D-G3P ligated TIM (green). Insets: Carbon correlations for the Thr Cβ –Cα, Gly Cα–CO, and Ala Cβ –Cα regions. The spectrum of apo TIM was acquired on a Bruker Avance DRX-750 spectrometer; the spectrum of D-G3P-bound TIM was acquired on a Varian Infinity 600-MHz spectrometer.

Fig. 7.

All residues involved in chemical shift perturbation upon ligand binding of G3P detected by (a) SSNMR and (b) solution NMR. (a) SSNMR markers that are well resolved and in contact with substrate include Ala163, Thr172, Thr177, and Gly210. They are labeled in blue, and the insets are their corresponding peaks in the overlay CC spectra of apo TIM (red) and D-G3P bound TIM (green). (b) The residues from solution NMR are the ones with backbone nitrogen shifted no less than 0.5 ppm upon binding of G3P.3 The schematic structure of the TIM monomer is the yeast TIM complexed with the substrate DHAP (PDB ID 1NEY1). (c) Residues involved in conformational change detected by SSNMR in yeast TIM (red), by solution NMR in yeast TIM3 (blue), and by solution NMR in chicken TIM4 (pink), and predicted by SHIFTX5 (green; PDB IDs 1I45 and 1NEY), mapped onto the primary sequence of yeast TIM. The residues that are not observed in both apo and ligated TIMs by NMR are coded in black. The active-site residues observed by X-ray are coded in yellow. The chicken TIM primary sequence is slightly different from that of the yeast TIM; therefore, mapping is based on their correlation.6 Most (15 of 18) shifts in SSNMR data are near or at substrate contacts (yellow). The rest (Thr29, Gln119, and Ile184) curiously are all on or near the regions where solution NMR also shows shifts.

The chemical reaction is initiated by abstraction of the pro-R proton from C1 of DHAP by Glu165, the catalytic base.45 In the crystal structures, the conformational change upon ligand binding reorients the backbone and side-chain torsion angles of Glu165 from (φ=− 110.3, ψ=112.5, χ1 = −75.5) to (φ=−129.2, ψ=99.7, χ1 = −47.4), shifting the side chain by 2–3 Å. In this process, Glu165 rotates to mediate proton transfer between C1 and C2 carbons of the ligand. We were unable to confidently identify the catalytic base Glu165 in either the ligated state or the unligated state of the enzyme, which was also the case for prior solution NMR studies. Previously, 14 of the 17 total glutamates were partially assigned (N, CO, Cα, and Cβ ) in solution, and we report here the backbone assignment of eight (residues 22, 34, 37, 77, 104, 129, 203, and 239). The missing assignments of the Cγ and Cδ atoms of four residues (residues 34, 239, 104, and 203) were assigned in the solid state. Although shifts are observed with peaks in the Cγ–Cδ region of our 13C–13C 2D spectra, their site-specific assignment will require spectra with better resolution and signal-to-noise ratio.

The electrophilic side-chain of neutral His95 polarizes the carbonyl group (O2) of the substrate46,47 and thereby is a crucial residue for facilitating the reaction. His95 is positioned to interact with the O1 and O2 groups, and thereby to stabilize the transition state and the intermediate.48 The protonation states of His95 and the pathways of proton transfer remain topics of debate in the literature, and direct NMR measurements will be useful in settling these issues. The backbone of His95 was detected and assigned in the solution NMR studies; in addition, we have detected Cδ2, adjacent to Nε2,48,49 for which we observed a change in chemical shift upon substrate binding. In one model, His95 donates a proton from Nε2 to the substrate O2 atom to form an enediol(ate) intermediate and subsequently abstracts a second proton from the substrate O1 atom.50–54 In another model, Glu165 is responsible for shuttling this proton.42,51,52 In a third model, a direct internal proton transfer from O1 to O2 forms the intermediate.45,50,53 Mutations of His95 to Gln or Asn reduced kcat/Km (DHAP as substrate) to 0.006 and 0.003, respectively, compared to the wild type.46 Lodi and Knowles reported 13Cγ chemical shift changes in His95, His103, and His185 under different pH and binding conditions, using solution NMR and chemical titrations.48 Both His95 and His185 had unchanged chemical shifts over the range from pH 4.3 to pH 9.5. His95 had different Cγ shifts, depending on the ligand, and the Cγ resonance of His185 consistently shifted in the same direction. The His103 Cγ resonance shifted downfield with an increase in pH, but it remained unperturbed upon ligand binding. All three of these histidine atoms were identified in this work, and their Cβ and Cγ resonances remained unchanged upon ligand binding (discussed in a later section). The fact that the solution NMR study reports a change in the His185 Cγ resonance—and we do not—could be due to a different choice of ligand, but is a point that requires further investigation. On the other hand, in our data, the Cδ2 resonance of His95 moves downfield, from115.8 ppm (apo) to 117.4 ppm (bound), upon ligand binding. This change in chemical shift at Cδ2, next to the Nε2 donor nitrogen, is unambiguous evidence that His95 is an electrophile in this context. This assignment can be used to further investigate the catalytic mechanism of TIM with the native substrate.

A number of other active-site residues would be expected to shift upon binding, including those that are indirect reporters on the motions of Glu165, the (spectroscopically elusive) catalytic base. The side-chain carboxylate moves from an aqueous environment to a hydrophobic environment enclosed by residues Ala163, Ile170, Gly209, and Leu230. The distance between the Ala163 Cβ atom and the Glu165 carboxylate carbon decreases from 6.2 Å in the unbound state to 5 Å in the bound state. The observed shift in Ala163 Cβ (−0.8 ppm) in this work reports the approach of the negatively charged catalytic base (–COO−). Ala163 shows changes in its Cα, Cβ , CO, and N chemical shifts, which disappear upon binding in the yeast solution NMR study. The chicken solution NMR study only reports the Cβ and N shifts, which both remain unchanged upon binding. Ala163 is located outside of the active-site pocket, and it does not form direct hydrogen bonds to the substrate. In both the unbound structure (1I4511) and the substrate-bound structure (1NEY12), Ala163 is in close contact with residues in sheet 6 (residues 161, 162, 164, and 165): it is flanked by sheet 5 (residues 124–127) on one side and by Leu130 and Leu207 on the other side.

In addition, a number of ligands for the phosphate “anchor” the substrate and were also observed to shift, as expected, upon ligand binding. The amide nitrogen of Gly233 is directly hydrogen bonded to the phosphate oxygens in the substrate. Ser211, whose backbone binds the phosphate oxygen of the substrate, is not assigned in the solution studies, but is observed here. The amide nitrogens of Gly232 and Gly233 are directly hydrogen bonded to the phosphate oxygens in the substrate. We have assigned the Cα and CO atoms of Gly232 in both ligated and unligated TIMs, and a change in chemical shift was observed for both atoms. The Cα–CO cross-peak (for Gly233) appears in a congested region of the spectrum; therefore, we leave our observation of the shift in Gly232 out of the current discussion. Gly210, located in the YGGS motif in loop 7 (Tyr208-Gly209-Gly210-Ser211), is another active player in the restructuring loop 7 and in its interactions with loop 6 during binding. Binding induces a rotation of 90° for the peptide plane between Gly209 and Gly210, and a rotation of almost 180° for the peptide plane between Gly210 and Ser211.15 A hydrogen bond between the Gly210 amide proton and the Tyr208 hydroxyl group forms upon binding of G3P15 (in yellow in Fig. 7c). In the ligated enzyme, Gly210 reorients to form a hydrogen bond with a water molecule, which in turn forms a hydrogen bond to the phosphate oxygen of the substrate. In this study, we observed changes in the isotropic shift not seen previously in solution NMR. Solution NMR studies did not identify the peaks associated with this residue, possibly because they were broadened by chemical exchange. SHIFTX (Fig. 7c) predicts a chemical shift perturbation for this residue upon ligand binding.

In addition, there are a number of broader reporters of the well-studied conformational exchange of the active-site loops. Upon ligand binding, loop 6 clamps down over the active site, and loop 5 tilts slightly in response to the change in the hydrogen bond partner in loop 6. There is also a dramatic movement of loop 7, helping to position Glu165 into the active site. Hydrogen bonds between the C-terminus of loop 6 and the YGGS motif in loop 7, Gly173-Ser211, and Ala176-Tyr208 are loosened to initiate the loop opening. Ser211 positions its backbone amide to bind the phosphate oxygens of the ligand. In the unligated enzyme, the amide nitrogen of Gly210 points towards the aromatic ring of Tyr208.15 Ala163 in sheet 6, Ile184 in helix 6, Asn14 in loop 1, Thr29 in helix 1, Gly9 in sheet 1, and Gln119 in the loop after helix 4 all exhibit corresponding structural adjustments with the conformational change. Figure 7c shows additional residues involved in conformational changes, as observed by SSNMR (yeast TIM), solution NMR (yeast TIM), solution NMR (chicken TIM), and X-ray crystallography (yeast TIM), and as predicted by SHIFTX.55 Several residues show changes upon binding in these SSNMR studies that were not observed by the other methods. For example, Gln119 has a 0.6-ppm shift in Cβ resonance upon ligand binding, and it remains unchanged in the chicken TIM solution NMR data.

The resonance peaks that are shifted in the 13C–13C 2D spectra upon binding are potentially markers for future dynamic or titration studies. Good markers should be well resolved and sharp in both ligated and unligated forms. The cross-peaks for Ala163 Cβ –Cα, Gly210 Cα–CO, Thr172 Cβ –Cα, and Thr177 Cβ –Cα stand out as candidates. Furthermore, assigned residues with no isotropic shift change, but with a change in orientation (such as Ala169), are good candidates as probes for dynamics by SSNMR.

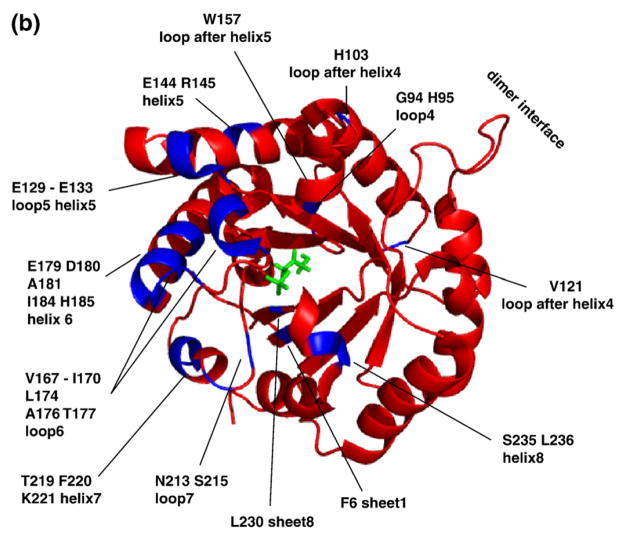

Crystal packing in the Michaelis complex

The residues involved in crystal contacts for the substrate-bound structure were calculated with ACCEPT-NMR (Supplementary Table 4). Our sample was prepared by cocrystallization and under conditions nearly identical with those used for the preparation of the 1NEY12 crystal; therefore, we assume that the crystal lattice and packing in our sample will be similar.

Figure 8 illustrates a comparison of crystal packing patterns between apo enzymes and ligated enzymes. The residues involved in crystal packing are mostly the same between the two samples, although more crystal packing interactions are observed for the ligated structure. Both subunits of loop 6 participate in packing interactions for the ligated and unligated proteins; the hydrogen bonding partners, however, are different for this loop in both forms. The open and closed states of loop 6 are stabilized by crystal packing interactions in both structures. From all of the changes in chemical shift observed upon ligand binding, only one appears to be associated with reorganization of the crystal packing. The loop after helix 4, with residues His103, Lys107, Lys114, and Gly118, gets involved in crystal packing interactions only after the ligand has been bound. Furthermore, although Gln119 (the direct neighbor of Gly118 on that loop) does not have a direct crystal contact, the packing force applied on its neighbor might affect its secondary structures, making this loop slightly distorted. This crystal packing distortion can result in a change in local environment, and it may only happen in the crystalline samples, explaining why Gln119 was observed to have isotropic shifts in our SSNMR studies, but not in solution.

Fig. 8.

Residues involved in crystal packing color-coded onto the apo TIM structure 1I45.1 The ones in red are for the apo enzyme, those in green are for the substrate-bound enzyme, and those in yellow are for both. Clearly, the ligated version has significantly more contacts. Among them, Q119 (in black) exhibits a shift that might be a marker for recrystallization. As mentioned in Fig. 7, it is also in a region where solution NMR shows a shift.

Conclusions

We have presented the 15N and 13C chemical shift assignments for microcrystalline TIM by SSNMR. We observe an overall agreement with prior solution assignments. Most active-site residues are assigned in this work, including a few that were not observed by solution NMR. Of particular interest, the His95 side-chain (Cδ1) assignment will be invaluable in ascertaining the role of His95 in proton transfer.

Some of the observed chemical shift perturbations, as compared to the solution NMR assignments, are related to crystal packing interactions. There are 42 residues that are within 5 Å of an adjacent molecule in the lattice, of which 5 residues show shifts above the cutoff of 0.4 ppm for Cα and Cβ , the cutoff of 0.5 ppm for CO, and the cutoff of 1.1 ppm for N. If we decrease this cutoff to 4 Å, 3 residues would show shifts out of 29 residues that are involved in crystal contacts; if the cutoff is set to 3 Å, 1 residue (Thr29) would show shifts out of 1 residue (Thr29) that is involved in crystal contacts. Of the eight shifts that are above the cutoff of 0.4 ppm for Cα and Cβ , the cutoff of 0.5 ppm for CO, and the cutoff of 1.1 ppm for N, six are on or near crystal contacts (cutoff, 5 Å). Therefore, large changes in chemical shift might be useful in locating crystal contact sites, although sites involved in crystal contacts may not, conversely, have particularly large chemical shifts.

For the first time, we report site-specific SSNMR chemical shift perturbations upon ligand binding. The chemical shift perturbations between ligated TIM and unligated TIM show conformational changes throughout the protein. Upon binding, we found 17 residues with large changes in chemical shift. Of these, 5 residues (His95, Thr172, Gly173, Gly210, and Ser211) are in direct contact with the ligand, 14 residues (Gly9, Asn14, Thr29, His95, Gly128, Glu129, Thr172, Gly173, Ala176, Thr177, Ile184, Ser211, Gly228, and Fhe229) have structural changes observed by either X-ray or solution NMR studies, and 2 residues (Thr29 and Thr172) are located at crystal packing sites that have changed. There are also residues that are in ligand contact but remain unshifted upon binding, such as Ala169. Future structural and dynamic work should be enabled by our discovery herein of the many active-site residues with well-resolved markers for binding, including His95, Ala163, Thr172, Thr177, and Gly210.

Materials and Methods

Materials

All reagents used were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, with the exception of glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, which was purchased from Roche Diagnostics Corporation (Germany). Isotopically enriched chemicals, including D-glucose (U-13C6; 99%; CIL no. CLM-1396), ammonium chloride (15N; 99%; CIL no. NLM-467), and 1,3-13C glycerol, were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories.

Expression and purification of yeast wild-type TIM

Uniformly 13C,15N-enriched wild-type recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae TIM was prepared by overexpression in E. coli and purified, as described elsewhere.56

SSNMR samples

For the apo TIM sample, the enzyme was concentrated to 200 mg/ml in 50 mM Tris–HCl, 50 mM NaCl, and 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (pH 6.8) at 4 °C and 40% (wt/vol) PEG (average molecular weight, 4000). The buffer was gently added to the protein solution in a sealed pipet tip to reach a final concentration of 15%, and the solution was stored overnight at 4 °C to form crystals. At lower ionic strengths [25 mM Tris–HCl, 25 mM NaCl, and 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (pH 6.8), at 4 °C], amorphous precipitation occurs.

For the ligated samples, the ligand was added in a 5:1 ligand/enzyme ratio. Ligand saturation was monitored by measuring inhibition of enzyme activity. The ligand and the precipitant were dissolved in 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 6.8) at 4 °C to minimize ionic strength. Addition of the magnesium salt of the ligand did not change the solution pH. After an hour of incubation at 4 °C, 40% (wt/vol) PEG 4000 was added to reach the final concentration of 15%. After an overnight incubation at 4 °C, crystals were visible. A typical 4-mm SSNMR Varian rotor contained 20 mg of hydrated microcrystalline protein, approximately 35 μl of the sample.

Activity assays

Activity assays were performed as previously reported (Fig. 9).56

Fig. 9.

Activity assay of TIM in the direction of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate to DHAP.

SSNMR spectroscopy experimental conditions

Resonance assignments were determined from data collected on either a Bruker Avance DRX-750 spectrometer or a Bruker Avance DRX-900 spectrometer (New York Structural Biology Center). Conformational change experiments were acquired on a Varian Infinity 600-MHz spectrometer.

Two-dimensional 13C–13C homonuclear correlation spectra were acquired using DARR (Dipolar-Assisted Rotational Resonance) mixing.24 Two-dimensional 15N–13C heteronuclear NCA and NCO spectra were acquired by selective double cross-polarization.25,26 Three-dimensional NCACX and NCOCX spectra were acquired using these two transfer methods sequentially: double cross-polarization–DARR.22

Data were processed and analyzed with NMRPipe57 and SPARKY.58 Spectra were processed with linear prediction,59–62 and baselines were corrected using a polynomial function.63 Apodization was achieved using either a cosine squared function,64 a Gaussian function,65 or a mixed Lorentzian–Gaussian function.

Referencing of the 13C Larmor frequency relative to 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonic acid was achieved using an external standard: the 13C adamantane methylene peak at 40.26 ppm.66 The nitrogen dimension was calibrated by indirect referencing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ivan Sergeyev for his program ACCEPT-NMR (http://mcdermott.chem/software/) used for crystal contact calculations. We thank previous and current McDermott group members for technical assistance. A.E.M. is a member of the New York Structural Biology Center. The New York Structural Biology Center is a STAR center supported by the New York State Office of Science, Technology, and Academic Research. This work was supported by funds from the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations used

- TIM

triosephosphate isomerase

- SSNMR

solid-state NMR

- DHAP

dihydroxyacetone phosphate

- G3P

DL-glycerol 3-phosphate

- D-G3P

D-glycerol 3-phosphate

- 2D

two-dimensional

- 3D

three-dimensional

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2009.10.043

References

- 1.Rieder SV, Rose IA. Mechanism of the triosephosphate isomerase reaction. J Biol Chem. 1959;234:1007–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kursula I, Salin M, Sun J, Norledge BV, Haapalainen AM, Sampson NS, Wierenga RK. Understanding protein lids: structural analysis of active hinge mutants in triosephosphate isomerase. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2004;17:375–382. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzh048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris TK. The mechanistic ventures of triosephosphate isomerase. IUBMB Life. 2008;60:195–198. doi: 10.1002/iub.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alber T, Banner DW, Bloomer AC, Petsko GA, Phillips D, Rivers PS, Wilson IA. On the 3-dimensional structure and catalytic mechanism of triose phosphate isomerase. Philos Trans R Soc London Ser B. 1981;293:159–171. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1981.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pompliano DL, Peyman A, Knowles JR. Stabilization of a reaction intermediate as a catalytic device—definition of the functional-role of the flexible loop in triosephosphate isomerase. Biochemistry. 1990;29:3186–3194. doi: 10.1021/bi00465a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blacklow SC, Knowles JR. How can a catalytic lesion be offset—the energetics of 2 pseudorevertant triosephosphate isomerases. Biochemistry. 1990;29:4099–4108. doi: 10.1021/bi00469a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nickbarg EB, Davenport RC, Petsko GA, Knowles JR. Triosephosphate isomerase—removal of a putatively electrophilic histidine residue results in a subtle change in catalytic mechanism. Biochemistry. 1988;27:5948–5960. doi: 10.1021/bi00416a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Straus D, Raines R, Kawashima E, Knowles JR, Gilbert W. Active-site of triosephosphate isomerase—in vitro mutagenesis and characterization of an altered enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:2272–2276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.8.2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petsko GA, Davenport RC, Frankel D, Raibhandary UL. Probing the catalytic mechanism of yeast triose phosphate isomerase by site-specific mutagenesis. Biochem Soc Trans. 1984;12:229–232. doi: 10.1042/bst0120229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lolis E, Petsko GA. Crystallographic analysis of the complex between triosephosphate isomerase and 2-phosphoglycolate at 2.5-A resolution—implications for catalysis. Biochemistry. 1990;29:6619–6625. doi: 10.1021/bi00480a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lolis E, Alber T, Davenport RC, Rose D, Hartman FC, Petsko GA. Structure of yeast triosephosphate isomerase at 1.9-A resolution. Biochemistry. 1990;29:6609–6618. doi: 10.1021/bi00480a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jogl G, Rozovsky S, McDermott AE, Tong L. Optimal alignment for enzymatic proton transfer: structure of the Michaelis complex of triosephosphate isomerase at 1.2-angstrom resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:50–55. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0233793100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parthasarathy S, Ravindra G, Balaram H, Balaram P, Murthy MRN. Structure of the Plasmodium falciparum triosephosphate isomerase—phosphoglycolate complex in two crystal forms: characterization of catalytic loop open and closed conformations in the ligand-bound state. Biochemistry. 2002;41:13178–13188. doi: 10.1021/bi025783a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verlinde CLMJ, Witmans CJ, Pijning T, Kalk KH, Hol WGJ, Callens M, Opperdoes FR. Structure of the complex between trypanosomal triosephosphate isomerase and N-hydroxy-4-phosphono-butanamide—binding at the active-site despite an open flexible loop conformation. Protein Sci. 1992;1:1578–1584. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wierenga RK, Noble MEM, Vriend G, Nauche S, Hol WGJ. Refined 1.83-A structure of trypanosomal triosephosphate isomerase crystallized in the presence of 2.4 M-ammonium sulfate—a comparison with the structure of the trypanosomal triosephosphate isomerase–glycerol-3-phosphate complex. J Mol Biol. 1991;220:995–1015. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90368-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noble MEM, Wierenga RK, Lambeir AM, Opperdoes FR, Thunnissen AMWH, Kalk KH, et al. The adaptability of the active-site of trypanosomal triosephosphate isomerase as observed in the crystal-structures of 3 different complexes. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 1991;10:50–69. doi: 10.1002/prot.340100106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wierenga RK, Noble MEM, Davenport RC. Comparison of the refined crystal-structures of liganded and unliganded chicken, yeast and trypanosomal triosephosphate isomerase. J Mol Biol. 1992;224:1115–1126. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90473-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massi F, Wang CY, Palmer AG. Solution NMR and computer simulation studies of active site loop motion in triosephosphate isomerase. Biochemistry. 2006;45:10787–10794. doi: 10.1021/bi060764c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kempf JG, Jung JY, Ragain C, Sampson NS, Loria JP. Dynamic requirements for a functional protein hinge. J Mol Biol. 2007;368:131–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rozovsky S, McDermott A. Substrate product equilibrium on a reversible enzyme, triosephosphate isomerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;104:2080–2085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608876104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andrew ER, Bradbury A, Eades RG. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectra from a crystal rotated at high speed. Nature. 1958;182:1659. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Igumenova TI, Wand AJ, McDermott AE. Assignment of the backbone resonances for microcrystalline ubiquitin. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5323–5331. doi: 10.1021/ja030546w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Igumenova TI, McDermott AE, Zilm KW, Martin RW, Paulson EK, Wand AJ. Assignments of carbon NMR resonances for microcrystalline ubiquitin. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:6720–6727. doi: 10.1021/ja030547o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takegoshi K, Nakamura S, Terao T. C-13–H-1 dipolar-assisted rotational resonance in magic-angle spinning NMR. Chem Phys Lett. 2001;344:631–637. doi: 10.1063/1.2364503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaefer J, Mckay RA, Stejskal EO. Double-cross-polarization NMR of solids. J Magn Reson. 1979;34:443–447. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baldus M, Geurts DG, Meier BH. Broadband dipolar recoupling in rotating solids: a numerical comparison of some pulse schemes. Solid State Nucl Magn Reson. 1998;11:157–168. doi: 10.1016/s0926-2040(98)00036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varga K, Tian L, McDermott AE. Solid-state NMR study and assignments of the KcsA potassium ion channel of S. lividans. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1774:1604–1613. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keller R. The Computer Aided Resonance Assignment Tutorial. Cantina Verlag; Goldau: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Franks WT, Zhou DH, Wylie BJ, Money BG, Graesser DT, Frericks HL, et al. Magic-angle spinning solid-state NMR spectroscopy of the beta 1 immunoglobulin binding domain of protein G (GB1): N-15 and C-13 chemical shift assignments and conformational analysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:12291–12305. doi: 10.1021/ja044497e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Detken A, Hardy EH, Ernst M, Kainosho M, Kawakami T, Aimoto S, Meier BH. Methods for sequential resonance assignment in solid, uniformly C-13, N-15 labelled peptides: quantification and application to antamanide. J Biomol NMR. 2001;20:203–221. doi: 10.1023/a:1011212100630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cole HBR, Torchia DA. An NMR-study of the backbone dynamics of staphylococcal nuclease in the crystalline state. Chem Phys. 1991;158:271–281. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pauli J, van Rossum B, Forster H, de Groot HJM, Oschkinat H. Sample optimization and identification of signal patterns of amino acid side chains in 2D RFDR spectra of the alpha-spectrin SH3 domain. J Magn Reson. 2000;143:411–416. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2000.2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luca S, Filippov DV, van Boom JH, Oschkinat H, de Groot HJM, Baldus M. Secondary chemical shifts in immobilized peptides and proteins: a qualitative basis for structure refinement under magic angle spinning. J Biomol NMR. 2001;20:325–331. doi: 10.1023/a:1011278317489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Favier A, Brutscher B, Blackledge M, Galinier A, Deutscher J, Penin F, Marion D. Solution structure and dynamics of Crh, the Bacillus subtilis catabolite repression HPr. J Mol Biol. 2002;317:131–144. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2002.5397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bockmann A, Lange A, Galinier A, Luca S, Giraud N, Juy M, et al. Solid state NMR sequential resonance assignments and conformational analysis of the 2×10.4 kDa dimeric form of the Bacillus subtilis protein Crh. J Biomol NMR. 2003;27:323–339. doi: 10.1023/a:1025820611009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wand AJ, Urbauer JL, McEvoy RP, Bieber RJ. Internal dynamics of human ubiquitin revealed by C-13-relaxation studies of randomly fractionally labeled protein. Biochemistry. 1996;35:6116–6125. doi: 10.1021/bi9530144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Plaut B, Knowles JR. pH-dependence of triose phosphate isomerase reaction. Biochem J. 1972;129:311. doi: 10.1042/bj1290311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rozovsky S, Jogl G, Tong L, McDermott AE. Solution-state NMR investigations of triose-phosphate isomerase active site loop motion: ligand release in relation to active site loop dynamics. J Mol Biol. 2001;310:271–280. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M. Improved methods for building protein models in electron-density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr Sect A. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sergeyev IV. ACCEPT-NMR: Automated Crystal Contact Extrapolation/Prediction Toolkit for NMR. 2009 http://mcdermott.chem/software/

- 41.Bash PA, Field MJ, Davenport RC, Petsko GA, Ringe D, Karplus M. Computer-simulation and analysis of the reaction pathway of triose-phosphate isomerase. Biochemistry. 1991;30:5826–5832. doi: 10.1021/bi00238a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guallar V, Jacobson M, McDermott A, Friesner RA. Computational modeling of the catalytic reaction in triosephosphate isomerase. J Mol Biol. 2004;337:227–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Degenhardt TP, Thorpe SR, Baynes JW. Chemical modification of proteins by methylglyoxal. Cell Mol Biol. 1998;44:1139–1145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nickbarg EB, Knowles JR. Triosephosphate isomerase—energetics of the reaction catalyzed by the yeast enzyme expressed in Escherichiacoli. Biochemistry. 1988;27:5939–5947. doi: 10.1021/bi00416a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alagona G, Ghio C, Kollman PA. Do Enzymes stabilize transition-states by electrostatic interactions or pK(a) balance—the case of triose phosphate isomerase (TIM) J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:9855–9862. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Komives EA, Chang LC, Lolis E, Tilton RF, Petsko GA, Knowles JR. Electrophilic catalysis in triosephosphate isomerase—the role of histidine-95. Biochemistry. 1991;30:3011–3019. doi: 10.1021/bi00226a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Belasco JG, Knowles JR. Direct observation of substrate distortion by triosephosphate isomerase using Fourier-transform infrared-spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1980;19:472–477. doi: 10.1021/bi00544a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lodi PJ, Knowles JR. Neutral imidazole is the electrophile in the reaction catalyzed by triosephosphate isomerase—structural origins and catalytic implications. Biochemistry. 1991;30:6948–6956. doi: 10.1021/bi00242a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lodi PJ, Chang LC, Knowles JR, Komives EA. Triosephosphate isomerase requires a positively charged active-site—the role of lysine-12. Biochemistry. 1994;33:2809–2814. doi: 10.1021/bi00176a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alagona G, Ghio C, Kollman PA. The intramolecular mechanism for the second proton transfer in triosephosphate isomerase (TIM): a QM/FE approach. J Comput Chem. 2003;24:46–56. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harris TK, Abeygunawardana C, Mildvan AS. NMR studies of the role of hydrogen bonding in the mechanism of triosephosphate isomerase. Biochemistry. 1997;36:14661–14675. doi: 10.1021/bi972039v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perakyla M, Pakkanen TA. Ab initio models for receptor–ligand interactions in proteins: 4. Model assembly study of the catalytic mechanism of triosephosphate isomerase. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 1996;25:225–236. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(199606)25:2<225::AID-PROT8>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fisher LM, Albery WJ, Knowles JR. Energetics of triosephosphate isomerase—nature of proton-transfer between catalytic base and solvent water. Biochemistry. 1976;15:5621–5626. doi: 10.1021/bi00670a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Albery WJ, Knowles JR. Free-energy profile for reaction catalyzed by triosephosphate isomerase. Biochemistry. 1976;15:5627–5631. doi: 10.1021/bi00670a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Neal S, Nip AM, Zhang HY, Wishart DS. Rapid and accurate calculation of protein H-1, C-13 and N-15 chemical shifts. J Biomol NMR. 2003;26:215–240. doi: 10.1023/a:1023812930288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rozovsky S, McDermott AE. The time scale of the catalytic loop motion in triosephosphate isomerase. J Mol Biol. 2001;310:259–270. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe—a multidimensional spectral processing system based on Unix pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goddard TD, Kneller DG. SPARKY 3. University of California; San Francisco: [Google Scholar]

- 59.Delsuc MA, Ni F, Levy GC. Improvement of linear prediction processing of NMR-spectra having very low signal-to-noise. J Magn Reson. 1987;73:548–552. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tang J, Norris JR. Two-dimensional Lpz spectral-analysis with improved resolution and sensitivity. J Magn Reson. 1986;69:180–186. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tang J, Lin CP, Bowman MK, Norris JR. An alternative to Fourier-transform spectral-analysis with improved resolution. J Magn Reson. 1985;62:167–171. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barkhuijsen H, Debeer R, Bovee WMMJ, Vanormondt D. Retrieval of frequencies, amplitudes, damping factors, and phases from time-domain signals using a linear least-squares procedure. J Magn Reson. 1985;61:465–481. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pearson GA. General baseline-recognition and baseline-flattening algorithm. J Magn Reson. 1977;27:265–272. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Demarco A, Wuthrich K. Digital filtering with a sinusoidal window function—alternative technique for resolution enhancement in FT NMR. J Magn Reson. 1976;24:201–204. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ferrige AG, Lindon JC. Resolution enhancement in FT NMR through use of a double exponential function. J Magn Reson. 1978;31:337–340. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wishart DS, Bigam CG, Yao J, Abildgaard F, Dyson HJ, Oldfield E, et al. H-1, C-13 and N-15 chemical-shift referencing in biomolecular NMR. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:135–140. doi: 10.1007/BF00211777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.