Abstract

Streptococcus suis is one of the most important post-weaning porcine bacterial pathogens worldwide. The serotypes 2 and 9 are often considered the most virulent and prevalent serotypes involved in swine infections, especially in Europe. However, knowledge of the bacterial factors involved in the first steps of the pathogenesis of the infection remains scarce. In several pathogenic streptococci, expression of multimodal adhesion proteins known as antigen I/II (AgI/II) have been linked with persistence in the upper respiratory tract and the oral cavity, as well as with bacterial dissemination. Herein, we report expression of these immunostimulatory factors by S. suis serotype 2 and 9 strains and that AgI/II-encoding genes are carried by integrative and conjugative elements. Using mutagenesis and different in vitro assays, we demonstrate that the contribution of AgI/II to the virulence of the serotype 2 strain used herein appears to be modest. In contrast, data demonstrate that the serotype 9 AgI/II participates in self-aggregation, induces salivary glycoprotein 340-related aggregation, contributes to biofilm formation and increased strain resistance to low pH, as well as in bacterial adhesion to extracellular matrix proteins and epithelial cells. Moreover, the use of a porcine infection model revealed that AgI/II contributes to colonization of the upper respiratory tract of pigs. Taken together, these findings suggest that surface exposed AgI/II likely play a key role in the first steps of the pathogenesis of the S. suis serotype 9 infection.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13567-017-0443-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Introduction

Streptococcus suis is one of the most important post-weaning bacterial pathogens of pigs and a major economic problem for the porcine industry [1]. Septicemia with sudden death, meningitis, arthritis, and endocarditis are the most frequent clinical signs caused by S. suis in pigs [2]. S. suis is also a zoonotic agent responsible for numerous human cases of meningitis, septicemia, and streptococcal toxic shock-like syndrome [2]. In Western countries, human S. suis infections mostly occur in individuals directly or indirectly linked with the porcine industry. In contrast, the general population is at risk of S. suis disease in certain Asian countries where this pathogen has been shown to be an important cause of adult meningitis [3]. Serotype 2 is, globally, considered the most virulent serotype and the one most frequently isolated from both porcine and human infections [4]. The use of multilocus sequence typing has revealed that serotype 2 strains belonging to certain sequence types (STs) are more virulent than others. ST1 strains (virulent) predominate in most Eurasian countries, whereas ST25 and ST28 strains (intermediate and low virulence, respectively) are mainly present in North America [4]. Meanwhile, highly virulent ST7 strains, responsible for at least two important human outbreaks in China, have only been reported in that country [5]. The serotype 9 has recently emerged in certain European countries, such as Spain, the Netherlands, and Germany [4]. Yet, very few studies have addressed the presence of virulence factors in this serotype, and putative virulence factors described for serotype 2 strains may not always be present in serotype 9 strains [6]. Moreover, the first S. suis serotype 9 human case of infection was reported in 2015 [7].

The early steps of the pathogenesis of the S. suis infection are not well understood [1, 8]. Currently, the most accepted hypothesis is that virulent strains reach the bloodstream after breaching the mucosal epithelium of either the upper respiratory or the gastrointestinal tracts of pigs [1]. Similarly, infection of humans occurs via skin wounds or at the intestinal interface following ingestion of raw or undercooked infected meat [1]. However, the precise mechanisms and virulence factors involved remain unknown. Of note, the upper respiratory tract of pigs, particularly the tonsils and nasal cavities, are important reservoirs of S. suis [1]. Furthermore, S. suis has also been shown to be present in nearly half of the submaxillary lymph node samples of clinically healthy pigs [9]. Bacterial loads in saliva swab and tonsillar brush samples are similar, indicating that S. suis is indeed a natural inhabitant of the oral cavity [10].

Antigens I/II (AgI/II) have been extensively described in oral as well as in invasive pathogenic streptococci, including Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus gordonii, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Streptococcus agalactiae [11]. AgI/II are immunostimulatory components and multimodal adhesion proteins implicated in host upper respiratory tract and oral cavity persistence and dissemination [11]. Affinity of AgI/II-like proteins for binding salivary glycoproteins, especially the glycoprotein (gp) 340 (also called DMBT1 protein) is a common feature of this protein family [12]. Large quantities of gp340 are present in the saliva of mammals in either a surface-immobilized form or fluid phase form. It is also present at all mucosal surfaces, including the nasal and intestinal cavities [13, 14]. Interestingly, it has been shown that S. suis is able to adhere to gp340 and that this protein aggregates certain strains of S. suis [15]. However, the strains tested did not express AgI/II when using a heterologous monospecific antibody [15].

In this study, using in silico analyses, genes with homology to those coding for AgI/II were identified in S. suis serotype 2 and 9 strains. Using isogenic mutants deficient for the expression and production of AgI/II in both serotype 2 (S2ΔagI/II) and serotype 9 (S9ΔagI/II), the role of this protein in different aspects of the pathogenesis of the infection caused by S. suis was evaluated. We report for the first time that these proteins play a limited or important role in the pathogenesis of the infection caused by S. suis serotype 2 and 9, respectively.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. The virulent serotype 2 ST7 strain SC84, responsible for the 2005 human outbreak in China [5], and the serotype 9 strain 1135776 (isolated from a diseased pig in Canada) were used herein as models to study the role of Ag I/II in the pathogenesis of the infection caused by S. suis. Twenty-five additional S. suis serotype 9 strains recovered from diseased pigs were also used to evaluate the prevalence of agI/II genes by PCR (Additional file 1). Seventeen of these strains originated from Canada, 3 from Brazil, 1 from Denmark (reference strain), and 4 from Germany. A strain isolated from a human case of infection was also included [7]. The S. mutans strain Ingbritt was used as a tool for collection of porcine salivary agglutinins (pSAGs) whereas the Escherichia coli TOP10 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), MC1061 [16], and BL21(DE3) (Invitrogen) strains were used for DNA manipulations and/or AgI/II protein production. The different Streptococcus and E. coli strains were grown at 37 °C in Todd Hewitt (THB) under static conditions or in Luria-Bertani broth (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) with shaking, respectively. Antibiotics (Sigma-Aldrich, St-Louis, MO, USA), where needed, were used at the following concentrations for S. suis and E. coli: spectinomycin at 500 and 50 µg/mL and erythromycin at 5 and 200 µg/mL, respectively. Ampicillin was also used at a concentration of 50 µg/mL for E. coli.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in the study

| Strain or plasmid | Characteristics | References |

|---|---|---|

| Streptococcus suis | ||

| SC84 | Serotype 2 strain isolated from a patient with streptococcal toxic shock-like syndrome in China | [47] |

| 1135776 | Serotype 9 strain isolated from pig following sudden death in Canada | This study |

| S2ΔagI/II | SC84-derived strain carrying an in-frame deletion of the agI/II gene | This study |

| S9ΔagI/II | 1135776-derived strain carrying an in-frame deletion of the agI/II gene | This study |

| S2CΔagI/II | SC84-derived strain carrying pOri23-S2agI/II | This study |

| S9CΔagI/II | 1135776-derived strain carrying pOri23-S9agI/II | This study |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| TOP10 | Host for pCR2.1 and pSET4s derivatives | Invitrogen |

| MC1061 | Host for pOri23 derivatives | [16] |

| BL21(DE3) | Host for pET151 derivatives | Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pET151 | Apr, pBR322 ori, T7 promotor | Invitrogen |

| pCR2.1 | Apr, Kmr, pUC ori, lacZΔM15 | Invitrogen |

| pSET4s | Spcr, pUC ori, thermosensitive pG+host3 ori, lacZΔM15 | [37] |

| pOri23 | Ermr, ColE1 ori, P23 | [28] |

| pET151–S2agI/II | pET151 carrying the S2 agI/II gene | This study |

| pSET4s–S2agI/II | pSET4s carrying regions upstream and downstream of the S2 agI/II gene | This study |

| pSET4s–S9agI/II | pSET4s carrying regions upstream and downstream of the S9 agI/II gene | This study |

| pOri23spc–S2agI/II | pOri23 carrying the S2 agI/II gene as well as its promotor and terminator | This study |

| pOri23spc–S9agI/II | pOri23 carrying the S9 agI/II gene as well as its promotor and terminator | This study |

Bioinformatics analyses

In silico analyses of AgI/II-coding DNA sequences (CDS) in S. suis genomes were performed using BLASTN (expected threshold < 10−3) as previously described [17]. The S. suis nucleotide collection nr/nt database available in GenBank (taxid 1307) was queried for S. suis genomes. Alongside, a bank of S. suis serotype 2 North American ST25 and ST28 strains isolated from diseased pigs whose genomes were previously published [18, 19] were also queried. Moreover, BLASTN was used to detect homologies with genes coding for AgI/II or orthologues that have already been described in other bacterial species: S. mutans SpaP (accession number NC_004350.2), S. gordonii SspA and SspB (accession number CP000725.1), S. pyogenes (accession number NC_007296.1), S. agalactiae (accession number AAJP01000002.1), and Enterococcus faecalis (accession number AY855841.2). Examination of CDS carriage by putative integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs) was conducted using the ICEberg database [20], followed by BLASTN using the S. suis serotype 2 SC84 (accession number GCA_000026725.1) and serotype 9 D12 (accession number GCA_000231905.1) genomes as queries. Protein domains were analyzed using the NCBI conserved domain database with the help of the BatchCD tool [21]. Cell wall anchored domains were predicted using CW-PRED [22], while transmembrane domains and signal peptide cleavage sites were detected using the TMHMM [23] and the SignalP [24] tools, respectively. The Expasy bioinformatics resource portal was used to determine the theoretical protein molecular weight [25].

DNA manipulations

Chromosomal S. suis DNA was prepared using standard methods [26] or InstaGene matrix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Plasmid DNA preparations and purification of PCR amplicons were performed using the QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit and the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), respectively, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Oligonucleotide primers (listed in Additional file 2) were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA, USA). Primers were designed from the available S. suis serotype 2 (strain SC84) and serotype 9 (strain D12) genomes. DNA ligations and transformation of competent E. coli were performed as previously described [27]. Sequencing reactions were carried out using an ABI 3730xl Automated DNA Sequencer and the ABI PRISM Dye Terminator Cycle Version 3.1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and analyses of sequences performed using the BioEdit© software and/or BLASTN.

Generation of the isogenic agI/II-deficient mutants and complemented strains

For precise in-frame deletions of the agI/II genes in the S. suis serotype 2 strain SC84 and serotype 9 strain 1135776, regions upstream and downstream of the genes were amplified and fused by overlap-extension PCR. The amplification products were subcloned into vector pCR2.1 (Invitrogen), excised using HindIII (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), and cloned into the thermosensitive gene replacement vector pSET4s as previously described [27]. The resulting serotype 2 and serotype 9 pSET4S-agI/II vectors were introduced into recipient serotype 2 and 9 strains, respectively. Allelic replacement and absence of AgI/II expression in resulting serotype 2 and serotype 9 agI/II-deficient mutants were confirmed by sequencing and Western blot, respectively.

The pOri23 plasmid [28], which carries a gene conferring resistance to erythromycin, was used for complementation assays. A DNA fragment composed of the full sequence of the agI/II genes, as well as their putative endogenous promotors and terminators was cloned into pOri23 using the EcoRI and PstI restriction enzymes (two constructs, one for the serotype 2 agI/II and another for the serotype 9 agI/II). Since the serotype 9 strain used is highly resistant to erythromycin (data not shown), and several reports have described increased resistance to this antimicrobial among serotype 2 strains [29, 30], a spectinomycin resistance cassette derived from pSET4s was introduced into the pOri23–S2agI/II and pOri23–S9agI/II plasmids. Following subcloning steps using E. coli MC1061, the generated pOri23spc–S2agI/II and pOri23spc–S9agI/II plasmids were then introduced into the S2ΔagI/II and S9ΔagI/II strains to generate the complemented S2CΔagI/II and S9CΔagI/II strains, respectively.

Cloning, expression, and purification of the His-tagged recombinant AgI/II protein and production of polyclonal mono-specific antibodies

A 4430 bp fragment of the serotype 2 agI/II gene, excluding the sequences coding for the cell wall anchorage and the LPXTG domains, was cloned into the pET151 expression vector (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Figure 1). Protein synthesis was induced using 0.5 mM of isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside and cells lysed using lysozyme (Sigma-Aldrich) and sonication. The resulting recombinant His-tagged AgI/II, henceforth rAgI/II, was purified by affinity chromatography using the His-Bind Resin Chromatography Kit (Novagen, Madison, WI, USA,) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Protein purity was evaluated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis following dialysis. Protein concentration was determined using the Pierce Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Rabbits were inoculated with the purified rAgI/II to produce a mono-specific polyclonal serum as previously described [31]. This serum was then used to verify presence of the protein in wild-type, isogenic agI/II-deficient mutants, and complemented strains by Western blot as previously described [32].

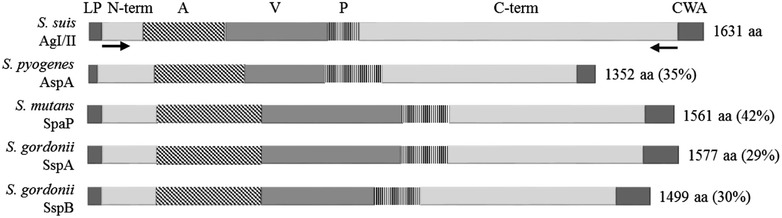

Figure 1.

Characteristics of AgI/II proteins present in different streptococci. The leader peptide signal (LP), N-terminal domain (N-term), alanine-rich region (A), variable region (V), proline-rich region (P), and C-terminal domain, and the cell wall anchorage domain (CWA) containing the LPXTG domain are illustrated for the S. suis AgI/II, S. pyogenes AspA, S. mutans SpaP, and S. gordonii SspA and SspB. Amino acid (aa) size and percentage of S. suis AgI/II protein identity are also indicated. Black arrows indicate the location of primers pET151_S2agI/IIΔCWA_F and pET151_S2agI/II _ΔLPXTG_R, which were used to produce the his-tagged recombinant AgI/II protein, rAgI/II.

Cell surface hydrophobicity

The relative surface hydrophobicity of the S. suis wild-type strains and agI/II-deficient mutants was determined by measuring their adsorption to n-hexadecane as previously described [33]. A serotype 2 non-encapsulated mutant strain showing a high percentage of hydrophobicity was used as a positive control [33].

In vitro pathogenesis assays

Self-aggregation and biofilm assays

For the self-aggregation assays, overnight cultures of S. suis were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.3, and re-suspended in THB to obtain an optical density (OD) at 600 nm of 0.05. Samples were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h under static conditions and self-aggregation quantified as previously described [34]. Biofilm formation capacity was determined as previously described [35] in the absence or presence of 2 mg/mL of porcine fibrinogen (Sigma-Aldrich).

S. suis aggregation to soluble porcine salivary agglutinins

Saliva was obtained from pigs as previously described [36] with a few modifications. Briefly, cotton ropes were suspended for 30 min to allow a total of 80 growing pigs from a high health status herd with no recent history of endemic S. suis disease to chew. No clinical signs of disease were present during collection. Whole saliva was decanted and impurities eliminated by centrifugation at 8000×g for 20 min at 4 °C. pSAGs were then purified from clarified saliva as previously described for human salivary agglutinins using S. mutans [37]. The pSAGs were dialyzed in PBS and the concentration determined using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit. Bacterial aggregation was quantified every 20 min for 1 h in the absence or presence of pSAGs [37].

Evaluation of S. suis adhesion to extracellular matrix proteins, porcine salivary agglutinins, and the gp340-derived SRCRP2 peptide by ELISA

Bacterial cultures were produced as previously described [38]. Formaldehyde-killed bacteria were washed using either PBS-T (PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20) for experiments involving extracellular matrix proteins (ECM), or TBS-T (10 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5 containing 0.1% Tween-20) supplemented with 1 mM CaCl2, for experiments involving pSAGs and the gp340-derived SRCRP2 peptide [39]. Maxisorp flat-bottom microtiter plates (NUNC, Rochester, NY, USA) were coated with 12.5 µg/mL of human plasma fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich), 15 µg/mL of human type I collagen (Corning, Corning, NY, USA), 1 mg/mL of porcine fibrinogen or 50 µg/mL of pSAGs, all diluted in carbonate coating buffer (0.1 M, pH 9.6), or with 200 µg/mL of the SRCRP2 peptide (Bio Basic Canada Inc., Markham, ON, Canada) diluted in water, overnight at 4 °C. After washing with PBS-T or TBS-T and blocking with non-fat dry milk, bacterial suspensions equivalent to 1 × 108 CFU/mL were added to the plates and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. Subsequent steps were undertaken as previously described [38] using serotype 2 or 9 specific rabbit antisera and the OD at 450 nm determined.

Acid stress killing assay

The ability of S. suis to withstand acid challenge was determined as previously described with some modifications [39]. Briefly, S. suis strains were grown in THB, washed twice with PBS, and adjusted to a concentration of 1 × 108 CFU/mL. Cells were then resuspended in 0.1 M glycine buffer adjusted to either pH 3.0 or 5.0 and incubated at 37 °C. Surviving bacteria were accurately determined using an Autoplate 4000 Spiral Plater (Spiral Biotech, Norwood, MA, USA).

Cell adhesion and invasion assays

The newborn porcine tracheal epithelial cell line (NPTr) was cultured until confluent as previously described [40]. Cells were infected with S. suis as previously described with minor modifications [41]. Briefly, PBS-washed NPTr cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and infected with S. suis at a multiplicity of infection of 10. After 2 h of incubation, wells were washed with PBS to remove non-associated bacteria. For adhesion assays, cells were lysed with 1 mL of cold water, while the invasion assay was performed using the antibiotic protection method as previously described [40], and associated or intracellular bacteria enumerated as described above.

Intranasal colonization in a porcine model of infection

All experiments involving animals were conducted in accordance with the guidelines and policies of the Canadian Council on Animal Care and the principles set forth in the Guide for the Care and the Use of Laboratory Animals by the Animal Welfare Committee of the University of Montreal, which approved the protocols and procedures used herein (permit number RECH-1570). Four-week old pigs (providing from the same high health status herd mentioned above) were used. The 10 pigs were randomly separated into two rooms upon arrival and their nasal cavities, saliva, and tonsils swabbed to confirm absence of serotype 9. The S. suis serotype 9 wild-type strain 1135776 and agI/II-deficient mutant were cultured as previously described [42] to obtain a final concentration of 2 × 109 CFU/mL. Intranasal infections were carried out as previously described with some modifications [43]. Pigs were inoculated with 1 mL of 2% acetic acid per nostril 1 h prior to infection with 1 mL per nostril of either the wild-type or the S9ΔagI/II mutant strain.

Nasal cavities were swabbed using sterile cotton-tipped applicators. Swabs were placed in sterile tubes containing PBS supplemented with 0.1% bovine serum albumin and immediately cultured. Serial dilutions of swab samples (100–10−6) were plated on Colombia agar supplemented with 5% defibrinated sheep blood (Cedarlane, Burlington, ON, Canada), Streptococcus selective reagent SR0126 (Oxoid, Hampshire, UK), and selected antibiotics to which the serotype 9 strain is resistant at the concentrations used (50 μg/mL spectinomycin, 5 μg/mL erythromycin, 0.2 μg/mL penicillin G, and 1 μg/mL tetracycline). After incubation for 24 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2, plates containing 30–300 colonies were selected. Suspected alpha-hemolytic colonies were enumerated and 10 S. suis-like colonies per plate were sub-cultured and tested by coagglutination assay using anti-S. suis serotype 9 rabbit serum as previously described [44]. Three weeks post-infection, pigs were euthanized and tonsils recovered. Tonsil samples were processed as previously described [45] and S. suis serotype 9 carriage evaluated as described above.

Statistical analyses

At least three independent biological replicates were performed for each experiment and results expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Raw data were analyzed using the non-parametric statistical Mann–Whitney test. Statistical differences are defined as being greater than p < 0.05.

Results

Prevalence and molecular characteristics of the S. suis AgI/II

Bioinformatics analyses using the S. suis (taxid 1307) genome database available in GenBank revealed the presence of genes coding for AgI/II-like proteins in the genomes of serotype 2 strains, including the ST7 strain SC84, ST1 strain BM407, ST25 strain 89–1591, and in a bank of North American S. suis serotype 2 ST25 and ST28 strain genomes [18, 19]. However, they were absent from the genome of the reference ST1 strain P1/7. The gene was also present in the genome of the serotype 9 strain D12. Given the low number of published S. suis serotype 9 genomes, PCR analyses were undertaken using field strains, which confirmed the presence of the gene in the 25 strains tested (Additional file 1), including strains from Canada, Germany, and Brazil, as well as in the S. suis serotype 9 reference strain from Denmark and a human isolate from Thailand. S. suis serotype 2 and 9 genes coding for AgI/II share approximately 95% of nucleotide identity. In addition, the promotors share 92% of nucleotide identity with the −35 and −10 boxes and the ribosome binding site for agI/II genes being present in all available genomes. Moreover, the terminators of agI/II genes are conserved in all strains (100% of nucleotide identity). The percentage of identity between the AgI/II proteins of serotypes 2 and 9 is 95%, being both highly similar. Alignment of the amino acid sequence of both proteins is presented in Additional file 3. Bioinformatics analyses revealed that the S. suis AgI/II has a theoretical molecular weight of 180 kDa, which is slightly larger than that of other described AgI/II, probably due to the SspB-like isopeptide-forming domain being repeated thrice in the C-terminal part of the S. suis AgI/II (Figure 1) [11]. The S. suis AgI/II shares between 29 and 42% of protein sequence identity with other streptococcal AgI/II, such as AspA (S. pyogenes), SpaP (S. mutans), SspA (S. gordonii), and SspB (S. gordonii) (Figure 1). Alongside, the S. suis AgI/II also shares 32% of protein identity with the aggregation substance PrgB (also called Asc10) of E. faecalis [46]. The S. suis AgI/II has similar characteristic domains to those described in oral streptococci (Figure 1) [11].

Further bioinformatics investigations, including the use of the ICEberg database, revealed that the gene encoding for the AgI/II protein in the serotype 2 strain SC84 is carried by the 89 K ICE (89 Kbp) [47], while that of the serotype 2 ST1 strain BM407 is carried by two putative ICEs annotated as ICESsu(BM407)1 and ICESsu(BM407)2) (75 and 80 Kbp, respectively). Moreover, the gene coding for AgI/II in the serotype 9 strain D12 is also carried by an element sharing 95% of nucleotide identity with the whole sequence of ICESsu(BM407)1. Altogether, these analyses suggest that the S. suis AgI/II are mainly carried by ICEs.

Confirmation of AgI/II-deficient mutants in both S. suis serotypes 2 and 9

Production of AgI/II by the serotype 2 and 9 strains SC84 and 1135776, respectively, was confirmed by immunoblotting using mono-specific antisera produced with the recombinant protein, rAgI/II (Figure 2). The proteins had a molecular weight of approximately 180 kDa, as predicted by bioinformatics analyses. Deletion of the agI/II gene resulted in absence of detectable signal while complementation of the mutant strains restored detection with a band at the expected molecular weight (Figure 2). Growth of the S2ΔagI/II and S9ΔagI/II mutants as well as that of the complemented strains was similar to their respective wild-type strains (data not shown).

Figure 2.

The AgI/II protein is expressed in the S. suis serotype 2 and 9 wild-type strains but is absent in S2Δ agI/II and S9Δ agI/II mutant strains. Western blot using cell wall extracts from S. suis serotype 2 (wells 1–3) and serotype 9 (wells 4–6): serotype 2 wild-type strain SC84 (well 1) and serotype 9 wild-type strain 1135776 (well 4); mutant strains S2ΔagI/II (well 2) and S9ΔagI/II (well 5); and complemented strains S2CΔagI/II (well 3) and S9CΔagI/II (well 6). Expected bands at approximately 180 kDa, shown by the black arrow, were observed for the serotype 2 and 9 wild-type and complemented strains, similar to that obtained with the purified AgI/II protein, rAgI/II (well 7), used as a positive control. MW: molecular weight marker.

It was previously described that AgI/II positively impacts surface hydrophobicity of oral streptococci. However, we did not observe significant differences in hydrophobicity between the S. suis serotype 2 or 9 wild-type strains and their AgI/II-deficient mutants (S2ΔagI/II and S9ΔagI/II) (Additional file 4). Interestingly, the serotype 2 wild-type strain was significantly more hydrophobic than that of serotype 9 (p < 0.05).

In vitro pathogenesis assays

Serotype-dependent role of the S. suis AgI/II in self-aggregation and biofilm formation

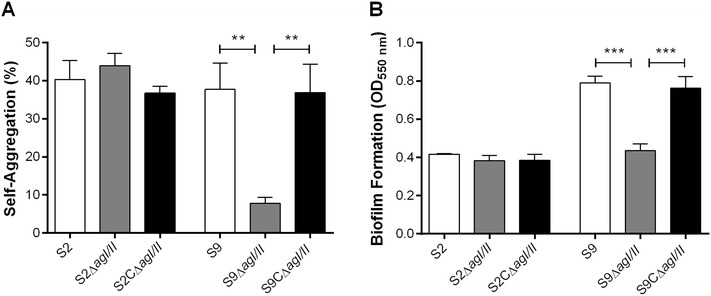

S. suis serotype 2 self-aggregation was not modified by the absence of AgI/II (Figure 3A). However, deletion of AgI/II significantly reduced self-aggregation of S. suis serotype 9 by 80% (p < 0.01) (Figure 3A). On the other hand, self-aggregation was completely restored when using the complemented S9CΔagI/II strain (Figure 3A). Thus, the serotype 9 AgI/II, but not that of serotype 2, is involved in bacterial self-aggregation.

Figure 3.

The S. suis serotype 9 (S9) AgI/II, but not that of the serotype 2 (S2), is implicated in bacterial self-aggregation and biofilm formation. The role of the S. suis AgI/II was evaluated with regards to cell-to-cell aggregation in fluid phase (A) and biofilm formation capacity in the presence of porcine fibrinogen (B) after 24 h of incubation at 37 °C. Data represent the mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments. **(p < 0.01) and ***(p < 0.001) indicate a significant difference between the S. suis S9 wild-type or complemented strain (S9CΔagI/II) and agI/II-deficient mutant (S9ΔagI/II).

The role of AgI/II in biofilm formation was evaluated for both serotype 2 and 9 in the presence of porcine fibrinogen. The capacity of the serotype 2 strain to form biofilm was relatively low, and no difference was observed in the absence of AgI/II (Figure 3B). On the other hand, the serotype 9 wild-type strain showed a significantly greater capacity to form biofilm than the wild-type serotype 2 strain in the presence of porcine fibrinogen (p < 0.01). Furthermore, the serotype 9 AgI/II was significantly involved in this bacterial function (p < 0.001) (Figure 3B). The capacity to form biofilm was restored in the complemented S9CΔagI/II strain (Figure 3B). Minimal biofilm formation was observed in the absence of porcine fibrinogen for both the serotype 2 and 9 strains (Additional file 5). Consequently, the serotype 9 AgI/II, but not that of serotype 2, plays an important role in the capacity to form biofilm.

The S. suis AgI/II increases both porcine salivary agglutinin induced-aggregation and adhesion to salivary agglutinins

Salivary agglutinins are major receptors of streptococcal AgI/II [12]. Thus, we investigated the interactions of the S. suis serotype 2 and 9 AgI/II with fluid phase (miming the conditions in saliva) and surface-immobilized (miming mucosa such as in the oral cavity) pSAGs. pSAGs collected from pig saliva was obtained at a concentration of 50 μg/mL, which is similar to that usually obtained for human salivary agglutinins [37].

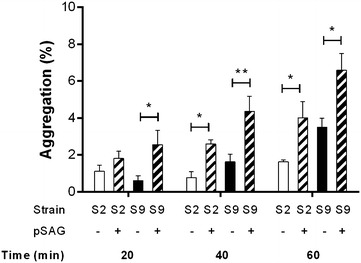

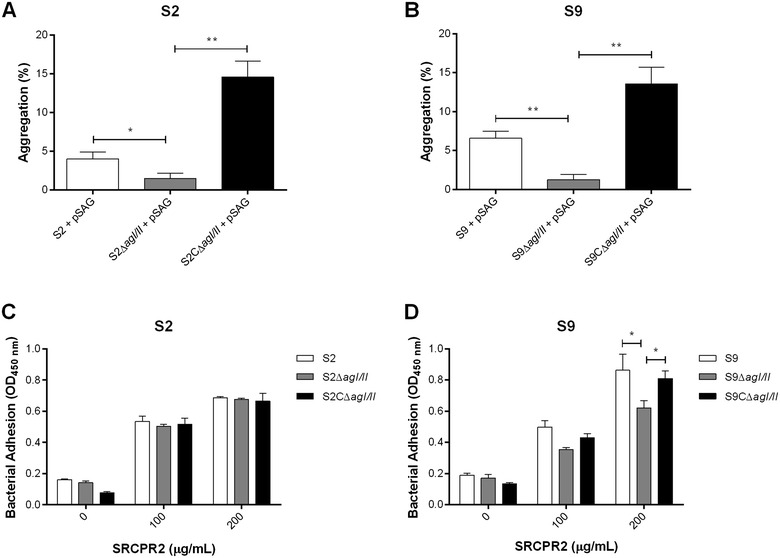

Results showed a significantly more rapid and greater aggregation of both S. suis serotype 2 or serotype 9 strains in the presence of pSAGs (p < 0.05) (Figure 4). Moreover, this fluid phase pSAG-induced aggregation significantly increased with time (p < 0.05) (Figure 4). However, the pSAG-mediated aggregation induced by the serotype 9 strain was significantly higher than that induced by the serotype 2 strain, but only after 60 min of incubation (p < 0.05) (Figure 4). AgI/II-deficiency significantly reduced fluid phase pSAG-induced aggregation for both serotypes (p < 0.05) (Figures 5A and B), and complementation of AgI/II-deficient mutants restored fluid phase pSAG-induced aggregation (p < 0.01) (Figures 5A and B).

Figure 4.

Porcine salivary agglutinins (pSAGs) aggregate S. suis serotype 2 (S2) and serotype 9 (S9). Evaluation of the fluid phase aggregation of the wild-type S. suis S2 and S9 strains in the absence (−) or presence (+) of pSAGs. Aggregation in the absence of pSAGs reflects self-aggregation only. Data represent the mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments. *(p < 0.05) and **(p < 0.01) indicate a significant difference of S. suis S2 or S9 aggregation in the absence and presence of pSAGs.

Figure 5.

The S. suis serotype 2 (S2) and serotype 9 (S9) AgI/II are involved in adhesion to fluid phase porcine salivary agglutinins (pSAGs), but only for S9 with surface-immobilized pSAGs. Evaluation of the fluid phase aggregation of S2 (A) and S9 (B) strains to pSAGs or to surface-immobilized gp340-derived peptide SRCRP2 by S2 (C) and S9 (D), the latter being measured by ELISA. Data represent the mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments. *(p < 0.05) and **(p < 0.01) indicate a significant difference between the S. suis S2 or S9 wild-type or complemented strain (S2CΔagI/II or S9CΔagI/II) and the agI/II-deficient mutants (S2ΔagI/II or S9ΔagI/II).

The adhesion of S. suis to surface-immobilized pSAGs was then evaluated using ELISA. Since background obtained with crude pSAGs was very elevated (data not shown), the gp340-derived peptide SRCRP2, described as the major binding sequence for AgI/II [37], was used. Results showed that deletion of the S. suis serotype 2 agI/II had no effect on adhesion to SRCRP2 (Figure 5C), while that of serotype 9 significantly reduced adhesion to SRCRP2 (p < 0.05), but only at a concentration of 200 μg/mL (Figure 5D). As expected, complementation of the S. suis serotype 9 AgI/II-deficient mutant restored adhesion to SRCRP2 (Figure 5D).

Taken together, these results demonstrate that AgI/II promotes pSAG-induced aggregation when in fluid phase for both serotypes, and adhesion to the gp340-derived peptide SRCRP2 at a high concentration for serotype 9 only.

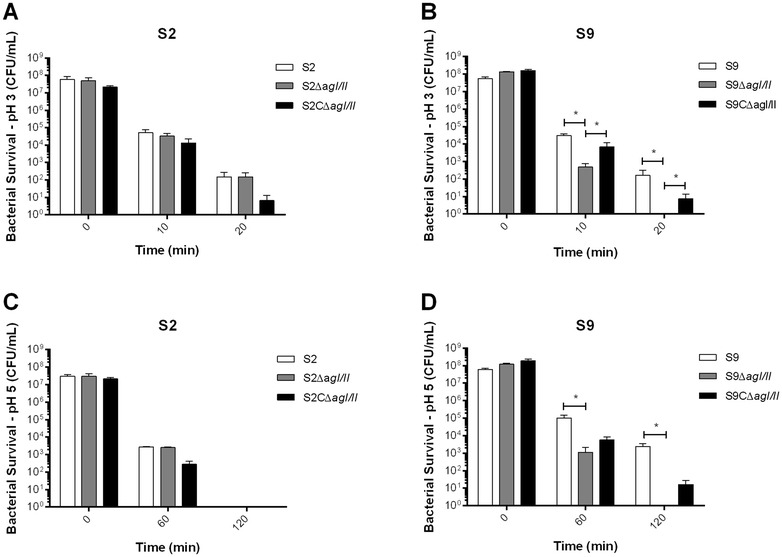

The S. suis AgI/II confers protection to acid stress

Once swallowed, S. suis will reach the stomach, in which it must overcome hostile environmental conditions such as low pH. We thus investigated the role of AgI/II and aggregation in resistance to low pH. Acid stress killing assays revealed that the S. suis serotype 2 AgI/II was not involved in acid resistance at pH 3 (Figure 6A) nor at pH 5 (Figure 6C). On the other hand, results showed that the S9ΔagI/II mutant strain survived significantly less than its wild-type strain (p < 0.05) at both pH 3 (Figure 6B) and pH 5 (Figure 6D). Thus, AgI/II confers partial protection to S. suis serotype 9, but not to serotype 2, against acidic environments.

Figure 6.

The S. suis serotype 9 (S9) AgI/II, but not that of serotype 2 (S2), is involved in protection against acid stress. Effect of acid stress on S. suis S2 and S9 viability, determined at pH 3 (A, B) and pH 5 (C, D). Data represent the mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments. *(p < 0.05) indicates a significant difference between the S. suis S9 wild-type or complemented strain (S9CΔagI/II) and agI/II-deficient mutant (S9ΔagI/II).

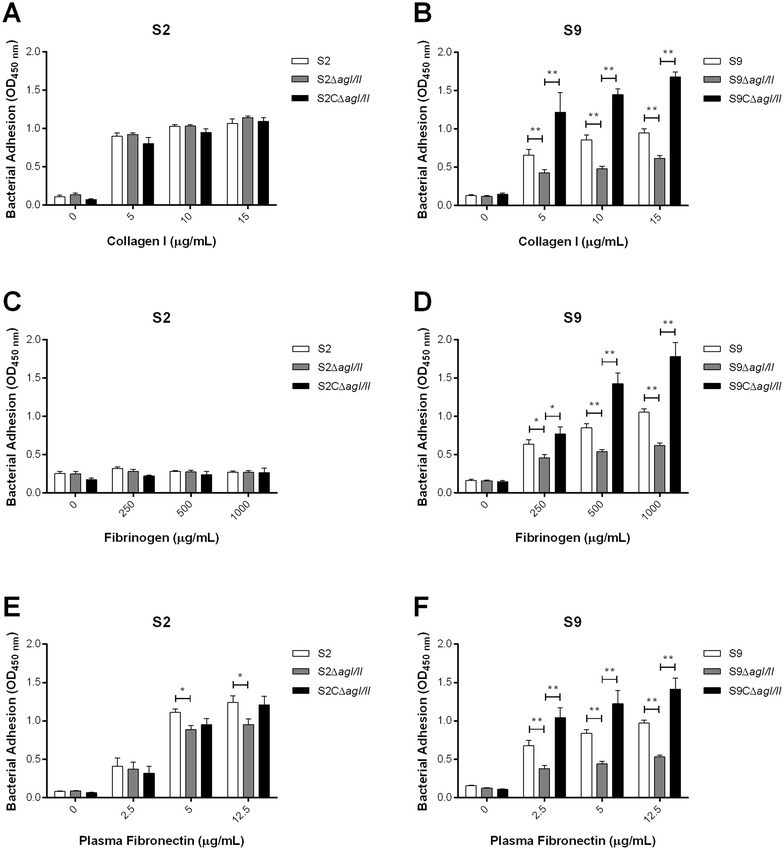

The S. suis serotype 9 AgI/II contributes to adhesion to extracellular matrix proteins and to porcine epithelial cells

AgI/II was previously described in other streptococci as binding ECM proteins and contributing to adhesion to and invasion of epithelial cells. Our results showed that while the serotype 2 AgI/II was not involved in adhesion to collagen I, that of the serotype 9 played a significant role (p < 0.01) (Figures 7A and B). In accordance, complementation of the S9ΔagI/II mutant restored the wild-type phenotype (Figure 7B). Moreover, as previously described with other serotype 2 strains [38], the serotype 2 wild-type strain used in this study (SC84) did not bind porcine fibrinogen (Figure 7C). On the other hand, the serotype 9 wild-type strain did bind to porcine fibrinogen, with absence of AgI/II significantly reducing this ability (p < 0.05) (Figure 7D). Once again, complementation of the S9ΔagI/II mutant strain restored this adhesion capacity (Figure 7D). Finally, the deletion of the S. suis serotype 9 agI/II gene and, to a lesser extent, that of the serotype 2, significantly decreased adhesion to plasma fibronectin (p < 0.05) (Figures 7E and F). Consequently, these results demonstrate the importance of AgI/II as a multimodal adhesin for S. suis serotype 9 while only playing a minor role for serotype 2.

Figure 7.

The S. suis serotype 9 (S9) AgI/II and, to a lesser extent, that of serotype 2 (S2), are bacterial adhesins for extracellular matrix proteins. Adhesion of the S. suis S2 and S9 strains to different concentrations of collagen I (A, B), fibrinogen (C, D), and plasma fibronectin (E, F) as evaluated by ELISA. Data represent the mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments. *(p < 0.05) and **(p < 0.01) indicate a significant difference between the wild-type or complemented strain (CΔagI/II) and the agI/II-deficient mutant (ΔagI/II).

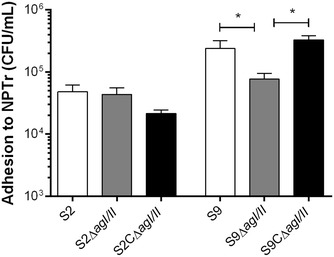

The role of AgI/II in adhesion to and invasion of porcine tracheal epithelial cells was subsequently investigated. Interestingly, the serotype 9 wild-type strain adhered significantly more to epithelial cells than did the serotype 2 (p < 0.05) (Figure 8). Adhesion assays revealed a significant decrease in adhesion to epithelial cells in the absence of AgI/II for the serotype 9 (p < 0.05), equivalent to 30% of wild-type strain adhesion, with complementation restoring adhesion (Figure 8). On the other hand, no differences were observed between the S. suis serotype 2 wild-type strain and its AgI/II-deficient mutant (Figure 8). Low levels of epithelial cell invasion were observed for both serotypes, with no role of AgI/II being evident (data not shown). Taken together, these results reveal that AgI/II is implicated in adhesion to host proteins and epithelial cells for serotype 9 and, to a lesser extent, for serotype 2.

Figure 8.

The S. suis serotype 9 (S9) AgI/II, but not that of the serotype 2 (S2), is involved in adhesion to porcine tracheal epithelial cells. Adhesion of the S. suis S2 and S9 strains to NPTr cells after 2 h of incubation with a multiplicity of infection of 10. Data represent the mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments. *(p < 0.05) indicates a significant difference between the S. suis S9 wild-type or complemented strain (S9CΔagI/II) and the agI/II-deficient mutant (S9ΔagI/II).

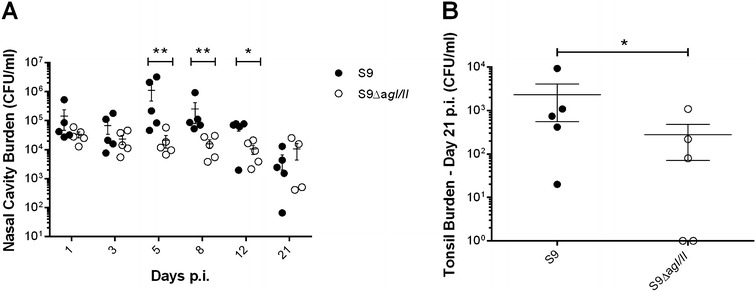

Role of AgI/II in colonization of the oral and nasal cavities of pigs

Given that in vitro results demonstrated an important role of AgI/II for S. suis serotype 9, we next evaluated the contribution of this protein in colonization using a porcine infection model. Animals were divided into two groups and infected with either the serotype 9 wild-type strain or the AgI/II-deficient mutant by intranasal inoculation. Evaluation of serotype 9 colonization revealed that the number of wild-type strain recovered from the nasal cavities significantly increased over time until day 12 post-infection (p.i.) (p < 0.05), whereas the number of S9ΔagI/II remained stable throughout the experiment (Figure 9A). Moreover, AgI/II-deficient mutants were recovered in significantly lower numbers from the nasal cavities of pigs on days 5, 8, and 12 p.i. (p < 0.05) (Figure 9A). Although the number of serotype 9 wild-type strain and AgI/II-deficient mutant in the nasal cavities of pigs was similar 21 days p.i. (Figure 9A), AgI/II-deficiency resulted in significantly reduced colonization of tonsils (p < 0.05) (Figure 9B). Together, these results strongly suggest that the serotype 9 AgI/II contributes to colonization of the porcine respiratory tract.

Figure 9.

The S. suis serotype 9 (S9) AgI/II is implicated in colonization of the porcine respiratory tract. An intranasal porcine model of infection was used to determine the implication of the S. suis S9 AgI/II in colonization of the nasal cavity (A) and tonsils 21 days post-infection (B). Data represent the mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments. *(p < 0.05) and **(p < 0.01) indicate a significant difference between presence of the S. suis S9 wild-type strain and the agI/II-deficient mutant (S9ΔagI/II).

Discussion

AgI/II proteins have been extensively described in oral pathogenic streptococci as multimodal adhesion proteins and immunostimulatory components implicated in host upper respiratory tract and oral cavity persistence and dissemination [11]. In addition, it has been shown that AgI/II proteins potentially play multiple roles in Streptococcus adherence, colonization, and microbial community development [11]. These proteins have also been described in pyogenic streptococci, such as S. pyogenes and S. agalactiae, but they have never been identified in Streptococcus pneumoniae [11]. An initial goal of this study was to determine whether S. suis possesses these putative virulence factors. We showed that most of the S. suis serotype 2 available genomes, including from different STs, possess genes encoding AgI/II. Interestingly, the gene was absent from the ST1 strain P1/7, which is commonly used as a reference for investigation of virulence [6]. We also identified AgI/II-encoding genes in the genome of the Chinese serotype 9 strain D12, in the serotype 9 reference strain 22083, as well as in a collection of 25 serotype 9 field strains (added herein given the limited number of serotype 9 genomes available), alongside a human isolate, tested by PCR.

It is widely recognized that mobile genetic elements such as insertion sequences, transposons, bacteriophages, plasmids, and genomic islands are key drivers of genomic evolution and bacterial adaptation. Among them, ICEs are chromosomal genetic elements that play an important role in horizontal gene transfer [48]. In both S. pyogenes and S. agalactiae, AgI/II are encoded by genes carried by ICEs, which can spread not only to other S. pyogenes and S. agalactiae strains, but also to other streptococci [49, 50]. Meanwhile, different ICEs have been described in S. suis [51], of which the 89 K ICE carried by the S. suis serotype 2 strain SC84 has been suggested to be responsible, at least in part, for the higher virulence of this strain [52]. Interestingly, results obtained in this study showed that the S. suis agI/II genes are mainly carried by ICEs. As such, it may be suggested that acquisition of AgI/II by S. suis occurred via horizontal transfer following acquisition of ICEs.

Persistence of S. suis in the oral cavity may contribute to the pathogenesis of the infection. Our data showed that AgI/II plays an important role in self-aggregation for S. suis serotype 9. This role was even more important in the presence of salivary glycoproteins, such as gp340. It has been previously shown that human salivary gp340 was able to aggregate an untypeable, a serotype 1, and a serotype 2 S. suis strain [15]. However, these strains were negative for the expression of AgI/II as evaluated by immunoblot using a polyclonal antibody raised against the S. mutans proteins [15]. In the present study, we showed that purified soluble pSAGs increase the ability of S. suis to aggregate and that AgI/II played an important role in such interactions for serotype 9 and, to a lesser extent, serotype 2. Fluid phase and surface-immobilized gp340 expose different binding properties and, consequently, differentially recognize adhesive phenotypes of diverse bacterial species. Herein, we showed that AgI/II also played a role in the S. suis serotype 9 adhesion to the surface-immobilized gp340-derived peptide SRCRP2. Similarly, the AgI/II from S. suis serotype 9 also played an important role in biofilm formation.

The relationship between the saliva-dependent aggregation, attachment to salivary glycoproteins, and biofilm formation in the oral cavity and pathogenesis of the infection caused by pathogenic streptococci is not very clear. On the one hand, aggregation (clumping) may presumably allow “bacterial clearance” from the oral cavity via swallowing [53]. It is usually accepted that the main route of infection for pigs is through the respiratory tract. However, more recently, the oral route (as clearly described in humans) has also been suggested as a portal of entry in pigs [54]. Although a recent report showed that disease could not be induced in an experimental infection by the oral route in post-weaned animals [55], a role of early colonization of the intestine of pre-weaned piglets followed by direct invasion through intestinal epithelial cells in animals under post-weaned stress could not be completely ruled out [1]. In the present study, an increased susceptibility to low pH (usually found in the stomach) was observed for S. suis serotype 9 in the absence of the agI/II gene. As such, it may be hypothesized that AgI/II induces bacterial self-mediated and salivary agglutinin-mediated aggregation and biofilm formation for serotype 9, which would increase, at certain moments, the swallowing of large amounts of bacteria. AgI/II would subsequently increase bacterial protection against the low pH of the stomach, thus allowing colonization of the intestine. However, this hypothesis remains to be confirmed.

It has been proposed that adhesion to epithelial cells is one of the most important initial steps of the pathogenesis of the infection caused by S. suis [1]. Similarly to other pathogens, S. suis is also able to bind ECM components, which have been suggested to be implicated as cell receptors [1]. At least 28 different S. suis components have been described to be involved in such interactions so far [1, 6]. In the present study, it was clearly shown that the AgI/II plays an important role in the adhesion of S. suis serotype 9 to collagen I, fibrinogen, and fibronectin. In the case of serotype 2, this protein plays a minimal role in adhesion to fibronectin and none to collagen I. As previously described, the serotype 2 strain was unable to bind fibrinogen [38]. The lack of binding to the latter may also explain differences observed in biofilm formation (in the presence of this protein) between serotype 2 and serotype 9 strains and the important role played by the serotype 9 AgI/II.

The implication of AgI/II in the adhesion to epithelial cells was further evaluated using porcine tracheal epithelial cells as a model [40]. Firstly, it was interesting to note that the serotype 9 wild-type strain presented higher adhesion levels than the serotype 2 strain, a fact that has been previously reported with other porcine cells [54]. A role was attributed to AgI/II in the adhesion of serotype 9 since a significant reduction of adhesion to these cells was observed using the S9ΔagI/II mutant. This reduction of adhesion could be explained by a reduction in the interactions with ECM components (as described above) or through a direct effect of the AgI/II as an adhesin. In fact, this protein has been described to be directly involved in epithelial cell adhesion and invasion by S. gordonii through β1 integrin recognition [56]. Using a different mechanism, this protein was also involved in adhesion/invasion of S. pyogenes to these cells [56].

Previous studies showed that the S. pyogenes AgI/II is implicated in upper respiratory tract colonization [57]. Since results showed that AgI/II plays important roles in vitro for serotype 9, its implication in colonization of the upper respiratory tract was investigated in pigs. As previously described, pigs infected by the serotype 9 wild-type strain and its isogenic S9ΔagI/II mutant via the intranasal route did not develop clinical signs of infection [43]. However, a slight, yet significantly lower colonization of the upper respiratory tract by the mutant strain, and, subsequently at the tonsillar level, was observed, suggesting that this protein may collaborate in bacterial colonization during the first steps of the infection. However, additional studies should be carried out to confirm this hypothesis.

In conclusion, the presence of AgI/II is herein reported for the first time in S. suis. This protein appears to play important or limited roles during the first steps of the pathogenesis of the infection caused by serotypes 9 and 2, respectively. Since the gene and protein sequences are highly similar between both serotypes, the observed differences are more difficult to explain than anticipated, and several hypotheses may be proposed. Firstly, a particular motif specific to the gene coding for the serotype 9 AgI/II might be responsible for the phenotypic differences highlighted in this study. Secondly, the S. suis serotype 2 and 9 agI/II genes are both carried by ICEs, which vary, creating differing genetic contexts and, consequently, differential gene regulation. Thirdly, critical S. suis virulence factors still remain poorly known [6]; the lack of a dominant role of the serotype 2 AgI/II observed herein might also be due to compensation by other virulence factors that result in bacterial redundancy [6]. Further studies are presently underway to explore these avenues. Overall, AgI/II may contribute to the colonization of the upper respiratory tract of pigs and could represent important surface bacterial components implicated in the first steps of the pathogenesis of the infection caused by S. suis.

Additional files

Additional file 1. List of S. suis serotype 9 strains used in this study and their characteristics.

Additional file 2. List of primers used in this study. Restriction sites are underlined and in bold.

Additional file 3. S. suis serotype 2 (S2) and serotype 9 (S9) AgI/II amino acid sequence alignment. Alignment was performed using Vector NTI 11.5. Conserved amino acids appear in light gray and identical amino acids in dark gray.

Additional file 4. Percent hydrophobicity of the S. suis serotype 2 (S2) and serotype 9 (S9) wild-type and agI/II -deficient mutant strains. Hydrophobicity was determined using n-hexadecane and the non-encapsulated S. suis serotype 2 strain, S2ΔcpsF, included as a positive control. Data represent the mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments.

Additional file 5. Biofilm formation by the S. suis serotype 2 (S2) and serotype 9 (S9) wild-type and agI/II -deficient mutant strains in the absence of porcine fibrinogen. Biofilm formation capacity was quantified after 24 h of incubation at 37 °C in the absence of porcine fibrinogen. Data represent the mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Conception of the work: SC, JPA, NF, DG, MG; laboratory techniques: SC, JPA, AD, DR, SL; acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data: SC, JPA, AD, NF, DG, MG; preparation of the manuscript: SC, JPA, MG. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Prof. Jianguo Xu (Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing, China), Prof. Christoph Baums (Leipzig University, Germany), and Dr. Anusak Kerdsin (Lampang Province, Thailand) for providing certain of the S. suis strains used in this study. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Paula J. Crowley (University of Florida, USA) for providing the human gp340 used herein as a control for pSAG, as well as Dr. Marisa Haenni and Dr. Pierre Châtre (Anses, France) for providing the pOri23 plasmid. The authors would also like to thank Annabelle Mathieu-Denoncourt, Léa Martelet, and Corinne Letendre for technical support.

Availability of data and materials

The data and materials not presented in this manuscript are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethics approval

All experiments involving animals were conducted in accordance with the guidelines and policies of the Canadian Council on Animal Care and the principles set forth in the Guide for the Care and the Use of Laboratory Animals by the Animal Welfare Committee of the University of Montreal, which approved the protocols and procedures used herein (Permit Number RECH-1570). A total of 10 pigs were used in this study.

Funding

This study was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) to MG (Grant #154280).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- AgI/II

antigen I/II

- BCA

bicinchoninic acid

- CDS

coding DNA sequence

- ECM

extracellular matrix protein

- gp340

glycoprotein 340

- ICE

integrative and conjugative element

- NPTr

newborn porcine tracheal epithelial cell

- OD

optical density

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- p.i.

post-infection

- pSAG

porcine salivary agglutinin

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- ST

sequence type

- THB

Todd Hewitt broth

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13567-017-0443-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Sarah Chuzeville and Jean-Philippe Auger contributed equally to this work

Contributor Information

Sarah Chuzeville, Email: sarah.chuzeville.sc@gmail.com.

Jean-Philippe Auger, Email: jean-philippe.auger.1@umontreal.ca.

Audrey Dumesnil, Email: audrey.dumesnil.1@umontreal.ca.

David Roy, Email: david.roy.6@umontreal.ca.

Sonia Lacouture, Email: sonia.lacouture@umontreal.ca.

Nahuel Fittipaldi, Email: nahuel.fittipaldi@oahpp.ca.

Daniel Grenier, Email: daniel.grenier@greb.ulaval.ca.

Marcelo Gottschalk, Email: marcelo.gottschalk@umontreal.ca.

References

- 1.Segura M, Calzas C, Grenier D, Gottschalk M. Initial steps of the pathogenesis of the infection caused by Streptococcus suis: fighting against nonspecific defenses. FEBS Lett. 2016;590:3772–3799. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gottschalk M, Xu J, Calzas C, Segura M. Streptococcus suis: a new emerging or an old neglected zoonotic pathogen? Future Microbiol. 2010;5:371–391. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wertheim HF, Nghia HD, Taylor W, Schultsz C. Streptococcus suis: an emerging human pathogen. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:617–625. doi: 10.1086/596763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goyette-Desjardins G, Auger JP, Xu J, Segura M, Gottschalk M. Streptococcus suis, an important pig pathogen and emerging zoonotic agent-an update on the worldwide distribution based on serotyping and sequence typing. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2014;3:e45. doi: 10.1038/emi.2014.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ye C, Zhu X, Jing H, Du H, Segura M, Zheng H, Kan B, Wang L, Bai X, Zhou Y, Cui Z, Zhang S, Jin D, Sun N, Luo X, Zhang J, Gong Z, Wang X, Wang L, Sun H, Li Z, Sun Q, Liu H, Dong B, Ke C, Yuan H, Wang H, Tian K, Wang Y, Gottschalk M, Xu J. Streptococcus suis sequence type 7 outbreak, Sichuan, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1203–1208. doi: 10.3201/eid1708.060232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Segura M, Fittipaldi N, Calzas C, Gottschalk M. Critical Streptococcus suis virulence factors: are they all really critical? Trends Microbiol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerdsin A, Hatrongjit R, Gottschalk M, Takeuchi D, Hamada S, Akeda Y, Oishi K. Emergence of Streptococcus suis serotype 9 infection in humans. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fittipaldi N, Segura M, Grenier D, Gottschalk M. Virulence factors involved in the pathogenesis of the infection caused by the swine pathogen and zoonotic agent Streptococcus suis. Future Microbiol. 2012;7:259–279. doi: 10.2217/fmb.11.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tharavichitkul P, Wongsawan K, Takenami N, Pruksakorn S, Fongcom A, Gottschalk M, Khanthawa B, Supajatura V, Takai S. Correlation between PFGE groups and mrp/epf/sly genotypes of human Streptococcus suis serotype 2 in Northern Thailand. J Pathog. 2014;2014:350416. doi: 10.1155/2014/350416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dekker N, Bouma A, Daemen I, Klinkenberg D, van Leengoed L, Wagenaar JA, Stegeman A. Effect of spatial separation of pigs on spread of Streptococcus suis serotype 9. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61339. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brady LJ, Maddocks SE, Larson MR, Forsgren N, Persson K, Deivanayagam CC, Jenkinson HF. The changing faces of Streptococcus antigen I/II polypeptide family adhesins. Mol Microbiol. 2010;77:276–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07212.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jakubovics NS, Stromberg N, van Dolleweerd CJ, Kelly CG, Jenkinson HF. Differential binding specificities of oral streptococcal antigen I/II family adhesins for human or bacterial ligands. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:1591–1605. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madsen J, Mollenhauer J, Holmskov U. Review: Gp-340/DMBT1 in mucosal innate immunity. Innate Immun. 2010;16:160–167. doi: 10.1177/1753425910368447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaemmerer E, Schneider U, Klaus C, Plum P, Reinartz A, Adolf M, Renner M, Wolfs TG, Kramer BW, Wagner N, Mollenhauer J, Gassler N. Increased levels of deleted in malignant brain tumours 1 (DMBT1) in active bacteria-related appendicitis. Histopathology. 2012;60:561–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.04159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loimaranta V, Jakubovics NS, Hytönen J, Finne J, Jenkinson HF, Strömberg N. Fluid- or surface-phase human salivary scavenger protein gp340 exposes different bacterial recognition properties. Infect Immun. 2005;73:2245–2252. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.4.2245-2252.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casadaban MJ, Cohen SN. Analysis of gene control signals by DNA fusion and cloning in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1980;138:179–207. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(80)90283-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chuzeville S, Dramsi S, Madec JY, Haenni M, Payot S. Antigen I/II encoded by integrative and conjugative elements of Streptococcus agalactiae and role in biofilm formation. Microb Pathog. 2015;88:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2015.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Athey TB, Auger JP, Teatero S, Dumesnil A, Takamatsu D, Wasserscheid J, Dewar K, Gottschalk M, Fittipaldi N. Complex population structure and virulence differences among serotype 2 Streptococcus suis strains belonging to sequence type 28. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0137760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Athey TB, Teatero S, Takamatsu D, Wasserscheid J, Dewar K, Gottschalk M, Fittipaldi N. Population structure and antimicrobial resistance profiles of Streptococcus suis serotype 2 sequence type 25 strains. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0150908. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bi D, Xu Z, Harrison EM, Tai C, Wei Y, He X, Jia S, Deng Z, Rajakumar K, Ou HY. ICEberg: a web-based resource for integrative and conjugative elements found in bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D621–D626. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marchler-Bauer A, Derbyshire MK, Gonzales NR, Lu S, Chitsaz F, Geer LY, Geer RC, He J, Gwadz M, Hurwitz DI, Lanczycki CJ, Lu F, Marchler GH, Song JS, Thanki N, Wang Z, Yamashita RA, Zhang D, Zheng C, Bryant SH. CDD: NCBI’s conserved domain database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D222–D226. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fimereli DK, Tsirigos KD, Litou ZI, Liakopoulos TD, Bagos PG, Hamodrakas SJ. CW-PRED: a HMM-based method for the classification of cell wall-anchored proteins of Gram-positive bacteria. Artificial intelligence: theories and applications. Berlin: Springer; 2012. pp. 285–290. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat Methods. 2011;8:785–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Artimo P, Jonnalagedda M, Arnold K, Baratin D, Csardi G, de Castro E, Duvaud S, Flegel V, Fortier A, Gasteiger E, Grosdidier A, Hernandez C, Ioannidis V, Kuznetsov D, Liechti R, Moretti S, Mostaguir K, Redaschi N, Rossier G, Xenarios I, Stockinger H. ExPASy: SIB bioinformatics resource portal. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W597–W603. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson K. Preparation of genomic DNA from bacteria. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2001 doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb0204s56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takamatsu D, Osaki M, Sekizaki T. Thermosensitive suicide vectors for gene replacement in Streptococcus suis. Plasmid. 2001;46:140–148. doi: 10.1006/plas.2001.1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Que YA, Haefliger JA, Francioli P, Moreillon P. Expression of Staphylococcus aureus clumping factor A in Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris using a new shuttle vector. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3516–3522. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.6.3516-3522.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chu YW, Cheung TK, Chu MY, Tsang VY, Fung JT, Kam KM, Lo JY. Resistance to tetracycline, erythromycin and clindamycin in Streptococcus suis serotype 2 in Hong Kong. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;34:181–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ngo TH, Tran TB, Tran TT, Nguyen VD, Campbell J, Pham HA, Huynh HT, Nguyen VV, Bryant JE, Tran TH, Farrar J, Schultsz C. Slaughterhouse pigs are a major reservoir of Streptococcus suis serotype 2 capable of causing human infection in southern Vietnam. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17943. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Y, Martinez G, Gottschalk M, Lacouture S, Willson P, Dubreuil JD, Jacques M, Harel J. Identification of a surface protein of Streptococcus suis and evaluation of its immunogenic and protective capacity in pigs. Infect Immun. 2006;74:305–312. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.305-312.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maddocks SE, Wright CJ, Nobbs AH, Brittan JL, Franklin L, Stromberg N, Kadioglu A, Jepson MA, Jenkinson HF. Streptococcus pyogenes antigen I/II-family polypeptide AspA shows differential ligand-binding properties and mediates biofilm formation. Mol Microbiol. 2011;81:1034–1049. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07749.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roy D, Grenier D, Segura M, Mathieu-Denoncourt A, Gottschalk M. Recruitment of factor H to the Streptococcus suis cell surface is multifactorial. Pathogens. 2016;5:E47. doi: 10.3390/pathogens5030047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bordeleau E, Purcell EB, Lafontaine DA, Fortier LC, Tamayo R, Burrus V. Cyclic di-GMP riboswitch-regulated type IV pili contribute to aggregation of Clostridium difficile. J Bacteriol. 2015;197:819–832. doi: 10.1128/JB.02340-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonifait L, Grignon L, Grenier D. Fibrinogen induces biofilm formation by Streptococcus suis and enhances its antibiotic resistance. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:4969–4972. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00558-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cook NJ, Hayne SM, Rioja-Lang FC, Schaefer AL, Gonyou HW. The collection of multiple saliva samples from pigs and the effect on adrenocortical activity. Can J Anim Sci. 2013;93:329–333. doi: 10.4141/cjas2012-120. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brady LJ, Piacentini DA, Crowley PJ, Oyston PC, Bleiweis AS. Differentiation of salivary agglutinin-mediated adherence and aggregation of mutans streptococci by use of monoclonal antibodies against the major surface adhesin P1. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1008–1017. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.1008-1017.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Esgleas M, Lacouture S, Gottschalk M. Streptococcus suis serotype 2 binding to extracellular matrix proteins. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;244:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bikker FJ, Ligtenberg AJ, Nazmi K, Veerman EC, van’t Hof W, Bolscher JG, Poustka A, Nieuw Amerongen AV, Mollenhauer J. Identification of the bacteria-binding peptide domain on salivary agglutinin (gp-340/DMBT1), a member of the scavenger receptor cysteine-rich superfamily. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:32109–32115. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203788200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y, Gagnon CA, Savard C, Music N, Srednik M, Segura M, Lachance C, Bellehumeur C, Gottschalk M. Capsular sialic acid of Streptococcus suis serotype 2 binds to swine influenza virus and enhances bacterial interactions with virus-infected tracheal epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2013;81:4498–4508. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00818-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roy D, Fittipaldi N, Dumesnil A, Lacouture S, Gottschalk M. The protective protein Sao (surface antigen one) is not a critical virulence factor for Streptococcus suis serotype 2. Microb Pathog. 2014;67–68:31–35. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Auger JP, Fittipaldi N, Benoit-Biancamano MO, Segura M, Gottschalk M. Virulence studies of different sequence types and geographical origins of Streptococcus suis serotype 2 in a mouse model of infection. Pathogens. 2016;5:E48. doi: 10.3390/pathogens5030048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pallarés FJ, Halbur PG, Schmitt CS, Roth JA, Opriessnig T, Thomas PJ, Kinyon JM, Murphy D, Frank DE, Hoffman LJ. Comparison of experimental models for Streptococcus suis infection of conventional pigs. Can J Vet Res. 2003;67:225–228. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gottschalk M, Higgins R, Boudreau M. Use of polyvalent coagglutination reagents for serotyping of Streptococcus suis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2192–2194. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.8.2192-2194.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fittipaldi N, Broes A, Harel J, Kobisch M, Gottschalk M. Evaluation and field validation of PCR tests for detection of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae in subclinically infected pigs. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:5085–5093. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.11.5085-5093.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hedberg PJ, Leonard BA, Ruhfel RE, Dunny GM. Identification and characterization of the genes of Enterococcus faecalis plasmid pCF10 involved in replication and in negative control of pheromone-inducible conjugation. Plasmid. 1996;35:46–57. doi: 10.1006/plas.1996.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen C, Tang J, Dong W, Wang C, Feng Y, Wang J, Zheng F, Pan X, Liu D, Li M, Song Y, Zhu X, Sun H, Feng T, Guo Z, Ju A, Ge J, Dong Y, Sun W, Jiang Y, Wang J, Yan J, Yang H, Wang X, Gao GF, Yang R, Wang J, Yu J. A glimpse of streptococcal toxic shock syndrome from comparative genomics of Streptococcus suis 2 Chinese isolates. PLoS One. 2007;2:e315. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wozniak RA, Waldor MK. Integrative and conjugative elements: mosaic mobile genetic elements enabling dynamic lateral gene flow. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:552–563. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Puymège A, Bertin S, Chuzeville S, Guédon G, Payot S. Conjugative transfer and cis-mobilization of a genomic island by an integrative and conjugative element of Streptococcus agalactiae. J Bacteriol. 2013;195:1142–1151. doi: 10.1128/JB.02199-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sitkiewicz I, Green NM, Guo N, Mereghetti L, Musser JM. Lateral gene transfer of streptococcal ICE element RD2 (region of difference 2) encoding secreted proteins. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:65. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Palmieri C, Princivalli MS, Brenciani A, Varaldo PE, Facinelli B. Different genetic elements carrying the tet(W) gene in two human clinical isolates of Streptococcus suis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:631–636. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00965-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang A, Yang M, Hu P, Wu J, Chen B, Hua Y, Yu J, Chen H, Xiao J, Jin M. Comparative genomic analysis of Streptococcus suis reveals significant genomic diversity among different serotypes. BMC Genom. 2011;12:523. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scannapieco FA. Saliva-bacterium interactions in oral microbial ecology. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1994;5:203–248. doi: 10.1177/10454411940050030201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ferrando ML, de Greeff A, van Rooijen WJ, Stockhofe-Zurwieden N, Nielsen J, Wichgers Schreur PJ, Pannekoek Y, Heuvelink A, van der Ende A, Smith H, Schultsz C. Host-pathogen interaction at the intestinal mucosa correlates with zoonotic potential of Streptococcus suis. J Infect Dis. 2015;212:95–105. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Warneboldt F, Sander SJ, Beineke A, Valentin-Weigand P, Kamphues J, Baums CG. Clearance of Streptococcus suis in stomach contents of differently fed growing pigs. Pathogens. 2016;5:E56. doi: 10.3390/pathogens5030056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nobbs AH, Shearer BH, Drobni M, Jepson MA, Jenkinson HF. Adherence and internalization of Streptococcus gordonii by epithelial cells involves beta1 integrin recognition by SspA and SspB (antigen I/II family) polypeptides. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:65–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Franklin L, Nobbs AH, Bricio-Moreno L, Wright CJ, Maddocks SE, Sahota JS, Ralph J, O’Connor M, Jenkinson HF, Kadioglu A. The AgI/II family adhesin AspA is required for respiratory infection by Streptococcus pyogenes. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. List of S. suis serotype 9 strains used in this study and their characteristics.

Additional file 2. List of primers used in this study. Restriction sites are underlined and in bold.

Additional file 3. S. suis serotype 2 (S2) and serotype 9 (S9) AgI/II amino acid sequence alignment. Alignment was performed using Vector NTI 11.5. Conserved amino acids appear in light gray and identical amino acids in dark gray.

Additional file 4. Percent hydrophobicity of the S. suis serotype 2 (S2) and serotype 9 (S9) wild-type and agI/II -deficient mutant strains. Hydrophobicity was determined using n-hexadecane and the non-encapsulated S. suis serotype 2 strain, S2ΔcpsF, included as a positive control. Data represent the mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments.

Additional file 5. Biofilm formation by the S. suis serotype 2 (S2) and serotype 9 (S9) wild-type and agI/II -deficient mutant strains in the absence of porcine fibrinogen. Biofilm formation capacity was quantified after 24 h of incubation at 37 °C in the absence of porcine fibrinogen. Data represent the mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments.

Data Availability Statement

The data and materials not presented in this manuscript are available from the corresponding author upon request.