Abstract

Internal bases in mRNA can be subjected to modifications that influence the fate of mRNA in cells. One of the most prevalent modified bases is found at the 5′ end of mRNA, at the first encoded nucleotide adjacent to the 7-methylguanosine cap. Here we show that this nucleotide, N6,2′-O-dimethyladenosine (m6Am), is a reversible modification that influences cellular mRNA fate. Using a transcriptome-wide map of m6Am we find that m6Am-initiated transcripts are markedly more stable than mRNAs that begin with other nucleotides. We show that the enhanced stability of m6Am-initiated transcripts is due to resistance to the mRNA-decapping enzyme DCP2. Moreover, we find that m6Am is selectively demethylated by fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO). FTO preferentially demethylates m6Am rather than N6-methyladenosine (m6A), and reduces the stability of m6Am mRNAs. Together, these findings show that the methylation status of m6Am in the 5′ cap is a dynamic and reversible epitranscriptomic modification that determines mRNA stability.

An emerging concept in gene expression regulation is that a diverse set of modified nucleotides is found internally within mRNA, and these modifications constitute an epitranscriptomic code. The initial concept of the epitranscriptome was introduced with the transcriptome-wide mapping of N6-methyladenosine (m6A), which revealed that m6A is found in at least a fourth of all mRNAs, typically near stop codons1,2. Notably, adenosine methylation to form m6A may be reversible. FTO and AlkB family member 5 (ALKBH5) both show demethylation activity towards RNA containing m6A (refs 3,4). Thus, the epitran-scriptome may be highly dynamic and subject to reversible base modifications that influence mRNA function.

In addition to internal base modifications, the 5′ end of mRNAs contains methyl modifications that are thought to be constitutive. mRNA biogenesis involves the addition of an N7-methylguanosine (m7G) cap with a triphosphate linker to the 5′ end of mRNAs. mRNAs are also methylated at the 2′-hydroxyl position of the ribose sugar of the first, and sometimes the second, nucleotide adjacent to the m7G cap5,6. These modifications recruit translation initiation factors to mRNA and allow the cell to discriminate host from viral mRNA7.

Although the extended 5′ cap structure contains these fixed methyl modifications, early studies by Moss and colleagues showed that one additional methyl modification can be detected in up to 30% of mRNA caps8. If the first nucleotide following the m7G cap is 2′-O-methyladenosine (Am), it can be further methylated at the N6-position by an unidentified nucleocytoplasmic methyltransferase9 to form N6,2′-O-dimethyladenosine (m6Am) (Fig. 1a)8. Since 2′-O-methylation is essentially always detected at the first nucleotide, mRNAs can have either Am or m6Am as the first nucleotide, but not A or m6A (ref. 10). The function of m6Am is unknown.

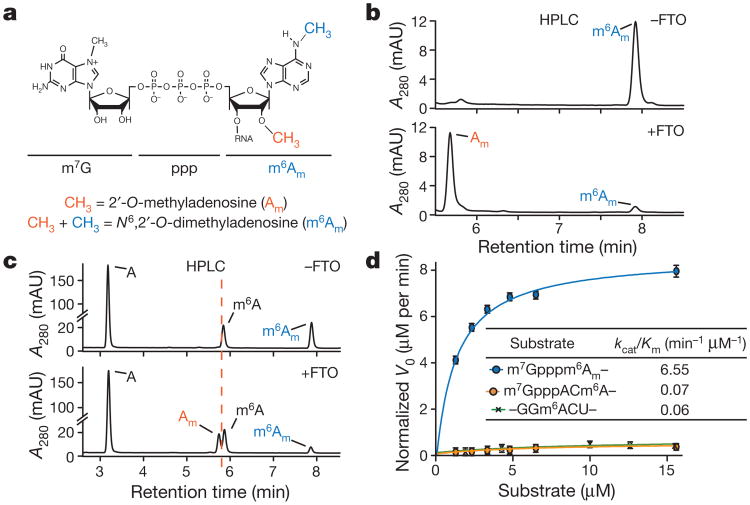

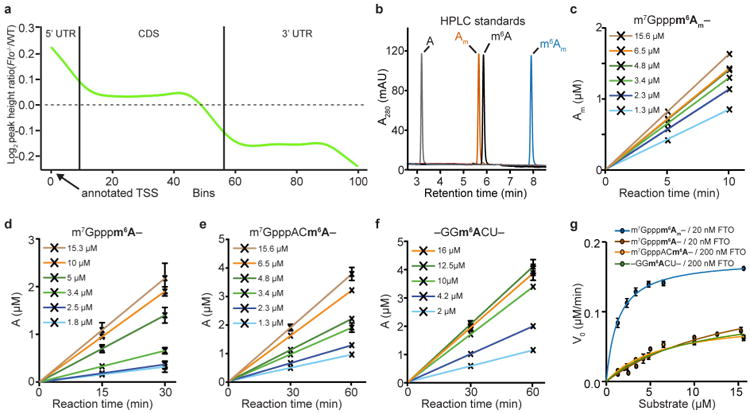

Figure 1. FTO prefers m6Am to m6A as a substrate.

a , Modifications of the extended mRNA cap. The first nucleotide (here shown as adenosine) adjacent to the m7G and the 5′-to-5′ triphosphate (ppp) linker is subjected to 2′-O-methylation (orange) on the ribose, forming cap1. Cap1 can be further 2′-O-methylated at the second nucleotide to form cap2 (not depicted). 2′-O-methyladenosine (Am) can be further converted to cap1m by N6-methylation (blue), which results in N6,2′-O-dimethyladenosine (m6Am). b, FTO efficiently converts m6Am to Am. A synthetic oligonucleotide with a 5′-m7Gpppm6Am (2 μM) was incubated with FTO (100 nM FTO, 1 h), which readily converted m6Am to Am (representative high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) track of n = 3 biological replicates). mAU, milli absorbance units. c, FTO preferentially demethylates m6Am compared to m6A. An oligonucleotide with a 5′-m7Gpppm6Am cap was mixed in an equimolar ratio with an oligonucleotide containing internal m6A. FTO (100 nM, 1 h) almost completely converted m6Am to Am. Demethylation of m6A was not detectable (representative HPLC track of n = 3 biological replicates). d, Michaelis-Menten kinetics of FTO for m6Am and m6A. Owing to the increased activity of FTO with m6Am compared to m6A, enzyme concentration was tenfold lower for m6Am (20 nM FTO for m6Am, 200 nM FTO for m6A). The data was normalized to enzyme concentration (m7Gpppm6Am (blue), m7GpppACm6A (orange), internal m6A (green); n = 3 biological replicates; mean ± s.e.m; V0 = initial reaction velocity).

Here we show that the extended mRNA cap carries dynamic and reversible epitranscriptomic information. We find that m6Am in its physiological context adjacent to the m7G cap can be readily converted to Am by FTO in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, we demonstrate that m6Am, and not m6A, is the preferred cellular substrate for FTO. Using our transcriptome-wide map of m6Am, we find that m6Am transcripts are markedly more stable than mRNAs beginning with Am or other nucleotides. Manipulation of m6Am levels by FTO depletion or FTO overexpression results in selective control of the abundance of m6Am-containing mRNAs in cells. We find that m6Am transcript stability is in part due to resistance to the mRNA-decapping enzyme DCP2. The significance of m6Am-mediated mRNA stabilization can be seen by examining DCP2-dependent mRNA degradation processes in cells, such as the pattern of mRNA degradation induced by microRNAs. These findings show that the cap-associated modified nucleotide m6Am is a dynamic and reversible epitranscrip-tomic modification that confers stability to mRNA in mammalian cells.

FTO targets methyladenine at transcription start sites

FTO exhibits demethylation activity towards m6A in assays performed in vitro4. However, we previously observed that most m6A residues are unaffected in FTO-deficient mice11. Only a few m6A residues showed increased abundance based on our transcriptome-wide mapping using antibodies directed against N6-methyladenine (6mA)11. To understand this selectivity, we asked if FTO demethylates m6A residues based on their position within mRNAs. We measured the change in m6A stoichiometry for each m6A peak mapped in the Fto-knockout relative to the wild-type transcriptome. We used a previously described stoichiometry measurement in which the number of m6A-containing RNA fragments at each peak is normalized to transcript abundance1. Notably, the m6A stoichiometry in the Fto-knockout transcriptome was increased for m6A residues closer to the 5′ end of the transcript (Extended Data Fig. 1a).

We recently showed that the antibodies used in these early m6A mapping studies bind both m6A and m6Am (ref. 12). These two nucleotides are found in mRNA and both contain the 6mA base8. As a result, early transcriptome-wide mapping studies of m6A also contain misannotated peaks that are instead derived from m6Am (ref. 12).

The distribution of FTO-regulated peaks in the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) is reminiscent of transcription start sites in mRNA (Extended Data Fig. 1a), which are often marked by m6Am (ref. 12). Our recent single-nucleotide-resolution map of m6Am showed that m6Am and transcription start sites overlap in mRNA12. This pattern of transcription start sites occurs because many mRNAs can be initiated at multiple positions downstream of the annotated start site. Thus, we hypothesized that the FTO-regulated peaks reflect m6Am rather than m6A.

FTO demethylates m6Am in an m7G cap-dependent manner

To determine whether FTO can target m6Am we measured FTO-mediated demethylation of a 21-nucleotide-long RNA with a 5′ m7G cap followed by m6Am. FTO treatment readily converted m6Am to Am, indicating demethylation at the N6-position (Fig. 1b, Extended Data Fig. 1b). Next, we added FTO (100 nM) to an equimolar mixture of the m6Am RNA and an RNA containing m6A in its physiological consensus. FTO demethylated nearly all m6Am in 60 minutes, while m6A demethylation was not readily detected (Fig. 1c).

Demethylation of m6A was only readily detected using higher concentrations of FTO (200 nM), consistent with previous reports which used a 5:1 ratio of substrate and enzyme4. However, demethylation of m6Am was achieved with substantially less FTO (20 nM) (Fig. 1d, Extended Data Figs 1c-g). The reported kcat of FTO towards m6A is relatively low compared to related dioxygenases (Extended Data Table 1). However, the kcat for FTO towards m6Am is at least 20 times higher and the catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) of FTO is approximately 100-fold higher towards m6Am than m6A (Fig. 1d, Extended Data Table 1).

The activity of FTO towards m6Am was dependent on specific structural elements of the extended m7G cap. FTO-mediated demethylation of m6Am was impaired when m7G was substituted for G, and further reduction was seen when m7G was removed altogether (Extended Data Fig. 2a, b). Demethylation was further reduced when the triphosphate was shortened to a monophosphate. Notably, the 2′-O-methyl substi-tuent, which distinguishes m6Am from m6A, was also important for the demethylation activity of FTO. By contrast, FTO-mediated demethylation of m6A was poor in diverse sequence contexts (Extended Data Fig. 2a, b).

Mass spectrometry confirmed FTO-mediated demethylation of m6Am to Am (Extended Data Fig. 2c, d). However, in addition to Am, N6-hydroxymethyl,2′-O-methyladenosine (hm6Am) was also detected. Previous analysis of FTO activity towards m6A showed that FTO-mediated demethylation occurs via a hydroxymethylated intermediate13. Therefore, FTO-mediated demethylation of m6Am may create additional cap diversity comprising oxidized 5′ caps.

FTO controls the balance between m6Am and Am in vivo

We next asked whether FTO demethylates m6Am in cellular mRNA. To quantify the ratio of m6Am to Am in mRNA, we used thin-layer chromatography (TLC)14. The m7G cap was enzymatically removed from mRNA and the exposed 5′ nucleotide was radiolabeled with [γ-32P]-ATP. Two-dimensional TLC of the nucleotide hydrolysate reveals the identity of the 5′ nucleotide (Extended Data Fig. 3a)14. Treatment of cellular mRNA with recombinant FTO resulted in an approximately 80% reduction of the m6Am:Am ratio (Fig. 2a). Notably, the same mRNA samples did not show decreased m6A upon FTO treatment (Extended Data Fig. 3b). These results suggest that FTO does not efficiently demethylate m6A in mRNA.

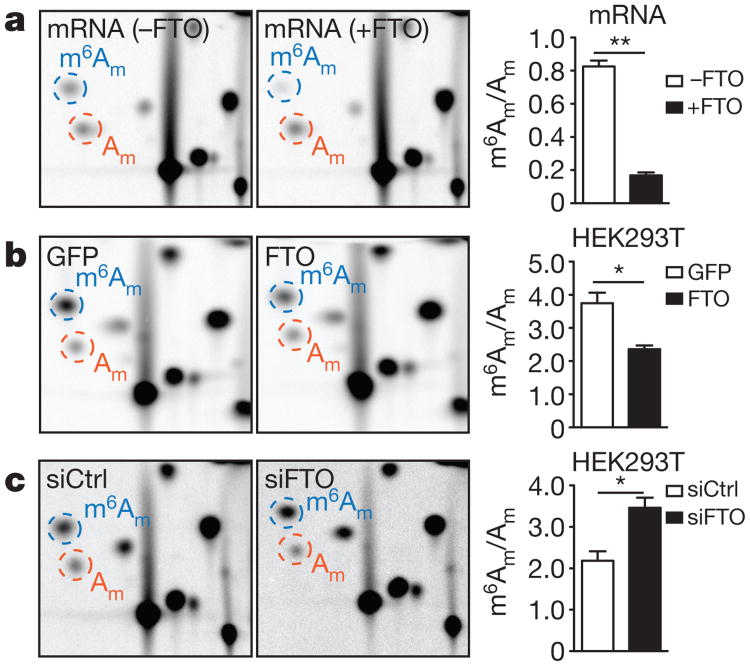

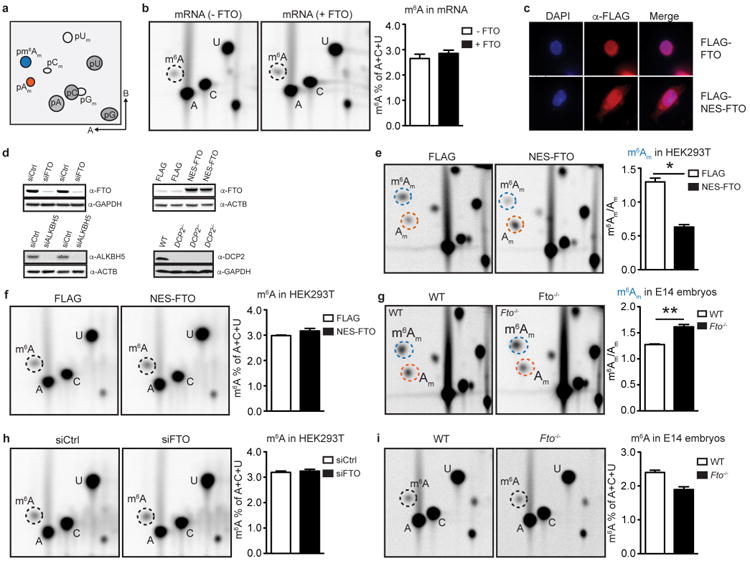

Figure 2. m6Am is the preferred substrate of FTO in vivo.

a, FTO readily demethylates m6Am in mRNA. Relative abundance of modified adenosines in mRNA caps derived from mRNA treated with FTO (1 μM, 1 h; representative images shown; n = 3 biological replicates; mean ± s.e.m.; unpaired Student's t-test, **P≤; 0.001). b, FTO expression decreases m6Am in HEK293T cells. Relative abundance of modified adenosines in mRNA caps of HEK293T cells expressing GFP (Flag-GFP) or wild-type FTO (Flag-FTO) (representative images shown; n = 3 biological replicates; mean ± s.e.m.; unpaired Student's t-test, *P ≤ 0.05). c, FTO knockdown increases m6Am in HEK293T cells. Relative abundance of modified adenosines in mRNA caps of HEK293T cells transfected with scrambled siRNA (siCtrl) or siRNA directed against FTO (siFTO) (representative images shown; n = 3 biological replicates; mean ± s.e.m.; unpaired Student's t-test, *P≤ 0.05).

To determine whether FTO demethylates m6Am in cells, we transfected HEK293T cells with Flag-FTO. This resulted in a significantly reduced m6Am:Am ratio relative to control cells (Fig. 2b). Although FTO is primarily nuclear, hypothalamic neurons exhibit cytosolic FTO after food deprivation15. Since there is no reported approach to efficiently induce cytosolic localization of FTO in cultured cells, we expressed FTO containing a nuclear-export signal (NES–FTO) in HEK293T cells (Extended Data Fig. 3c, d). This resulted in a more pronounced drop in the m6Am:Am ratio than wild-type FTO expression (Extended Data Fig. 3e). At this expression level, NES–FTO did not reduce m6A levels (Extended Data Fig. 3f). Thus, FTO demethylates m6Am in cells and cytosolic translocation of FTO may further enhance the demethylation of cytoplasmic m6Am mRNAs.

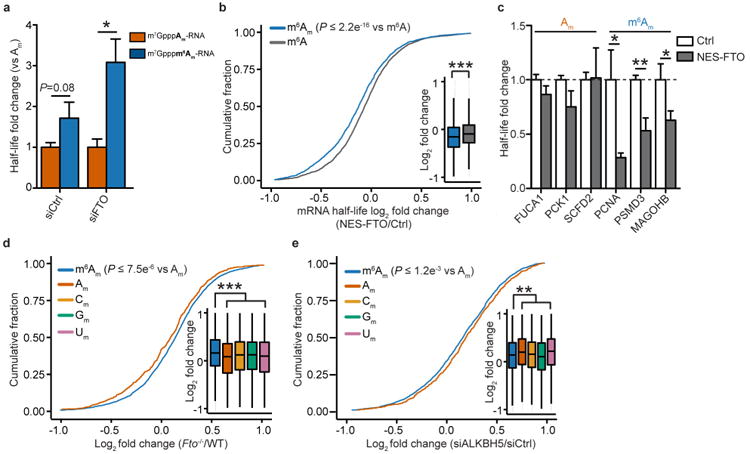

FTO knockdown further increased the already high14 m6Am:Am ratio in cells (Fig. 2c). Similarly, the m6Am:Am ratio was increased in Fto-knockout mouse embryos compared to wild type (Extended Data Fig. 3g). No increase in m6A levels was detectable in FTO-knockdown cells or Fto-knockout mouse embryos (Extended Data Figs 3h, i). By contrast, ALKBH5 knockdown increased m6A levels without increasing m6Am levels and ALKBH5 expression selectively demethylated m6A but not m6Am (Extended Data Figs 4a–d). These results suggest that FTO targets m6Am whereas ALKBH5 targets m6A in vivo.

m6Am mRNAs exhibit increased half-life in cells

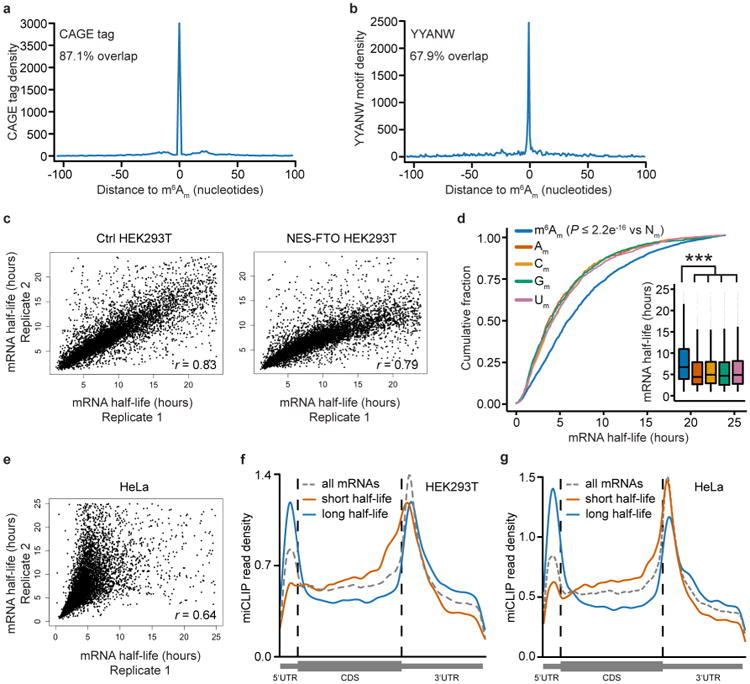

To determine whether m6Am confers unique effects on mRNA, we first classified cellular mRNAs based on whether they begin with m6Am, Am, 2′-O-methylcytidine (Cm), 2′-O-methylguanosine (Gm) or 2′-O-methyluridine (Um). mRNAs beginning with m6Am were identified by miCLIP12 (Supplementary Table 1). miCLIP-mapped m6Am residues were validated based on their overlap with transcription start sites and their preferential localization in a sequence context matching the core initiator motif16 (Extended Data Fig. 5a, b, Supplementary Table 1). mRNAs that did not contain m6Am were considered to begin with Am, Cm, Gm or Um based on the annotated starting nucleotide (Supplementary Table 2).

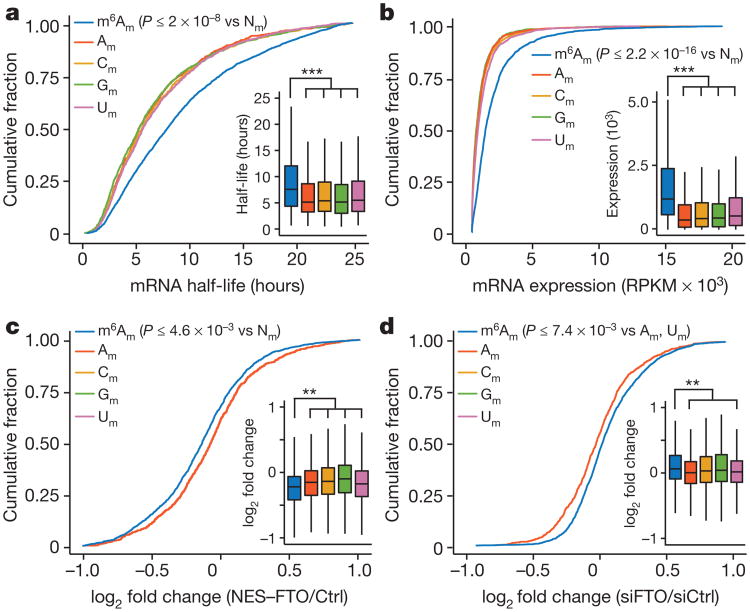

We next asked whether mRNA stability is linked to the identity of the first nucleotide. mRNAs beginning with Am, Cm, Gm and Um exhibited a very similar distribution of half-lives, with an average of around 6 h in HEK293T cells (Fig. 3a). However, mRNAs that begin with an m6Am were markedly more stable, with an average increase in half-life of approximately 2.5 h (Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 5c–e, Supplementary Table 3). A link between m6Am and mRNA stability is also seen when examining the distribution of m6A and m6Am miCLIP reads in long-lived and short-lived mRNAs (Extended Data Fig. 5f, g).

Figure 3. The presence of m6Am is associated with increased mRNA half-life.

a , mRNA stability is determined by the first encoded nucleotide in HEK293T cells. Cumulative distribution plot of the half-life for mRNAs that start with m6Am, Am, Cm, Gm and Um (n = 2,515 (m6Am); 762 (Am); 1,442 (Cm); 1,119 (Gm); 1,486 (Um); data represent the average from two independent datasets; each box shows the first quartile, median, and third quartile; whiskers represent 1.5 × interquartile ranges; one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test, ***P ≤ 2 × 10−8 versus m6Am; Nm = Am, Cm, Gm or Um). b, mRNA expression level is influenced by the modification state of the first encoded nucleotide in HEK293T cells. Cumulative distribution plot of the expression for mRNAs that start with m6Am, Am, Cm, Gm and Um (n = 2,536 (m6Am); 1,063 (Am); 2,098 (Cm); 1,577 (Gm); 2,071 (Um); data represent the average from two independent datasets; each box shows the first quartile, median, and third quartile; whiskers represent 1.5 × interquartile ranges; one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test, ***P ≤ 2.2 × 10−16 versus m6Am). c, FTO expression leads to a global decrease of m6Am mRNA half-life in HEK293T cells. Changes in half-life of mRNAs containing either m6Am or Am in cells transfected with either Flag vector (Ctrl) or FTO with an N-terminal nuclear export signal (NES-FTO) (n = 2,049 (m6Am); 951 (Am); 1,442 (Cm); 1,119 (Gm); 1,486 (Um); data represent the average from two independent datasets; each box shows the first quartile, median, and third quartile; whiskers represent 1.5 × interquartile ranges; one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test, **P ≤ 4.6 × 10−3 versus m6Am). d, FTO knockdown leads to a global increase of m6Am mRNAs in HEK293T cells. Expression of mRNAs containing either m6Am or Am upon FTO knockdown (n = 3,410 (m6Am); 1,355 (Am); 2,636 (Cm); 1,994 (Gm); 2,558 (Um); data represent the average from two independent mRNA expression datasets; each box shows the first quartile, median, and third quartile; whiskers represent 1.5 × interquartile ranges; one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test **P ≤ 7.4 × −3 m6Am versus Am and Um).

We reasoned that if m6Am stabilizes mRNA, then this would lead to increased m6Am mRNA levels. Indeed, m6Am mRNAs exhibit higher transcript levels than mRNAs that begin with Am, Cm, Gm or Um (Fig. 3b). Although the increased expression levels could be influenced by transcription rates, the half-life data suggests that increased mRNA stability contributes to the increased abundance of m6Am mRNAs. Taken together, these data indicate that the first nucleotide is an important determinant of mRNA stability and abundance.

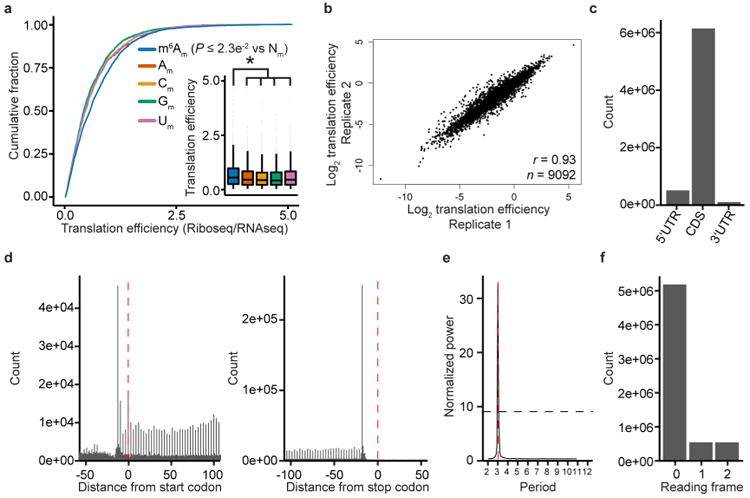

Additionally, m6Am mRNAs may increase translation efficiency (Extended Data Figs 6a-f). This is in line with a previous study that observed increased translation efficiency of mRNAs containing methylated adenine at the transcription start site17.

Alterations in m6Am levels control mRNA stability

To test directly whether m6Am can confer stability to mRNA, we synthe sized polyadenylated mRNAs starting with either m7GpppAm or m7Gpppm6Am in vitro. Electroporation of these mRNAs into HEK293T cells showed that the m6Am mRNA was more stable than the Am-initiated mRNA (Extended Data Fig. 7a).

Next, we selectively reduced cellular m6Am levels by expressing NES–FTO and monitored mRNA half-life. At the level of transfection used, changes in m6A were not detectable, but m6Am levels were significantly reduced (Extended Data Fig. 3c–f). Analysis of transcriptome-wide fold-changes in mRNA half-lives showed that NES–FTO expression causes a significant decrease in m6Am mRNA half-life compared to mRNAs initiated with Am (Fig. 3c). m6A-containing mRNAs were unaffected (Extended Data Fig. 7b). The effect of NES–FTO on m6Am mRNAs was also seen when monitoring the stability of individual transcripts using BrU pulse–chase labelling (Extended Data Fig. 7c). These results suggest that demethy-lation of m6Am reduces the stability of mRNAs that begin with this nucleotide.

Although m6Am levels are typically high in most cell types8,14, we further increased m6Am levels by FTO knockdown and measured mRNA levels using RNA-seq. Notably, mRNAs that start with m6Am showed higher abundance after FTO knockdown compared to Am-initiated mRNAs (Fig. 3d). This effect was also seen in Fto-knockout mouse liver compared to wild type (Extended Data Fig. 7d). Notably, ALKBH5 knockdown did not affect m6Am mRNAs (Extended Data Fig. 7e). We therefore conclude that increasing m6Am levels enhances the stability of these mRNAs.

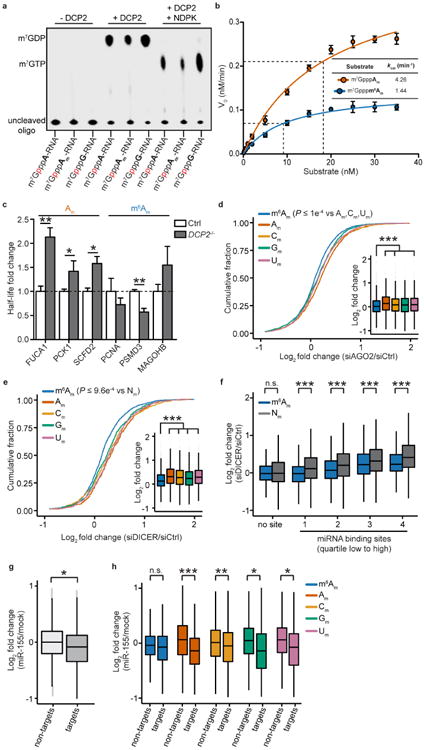

m6Am confers reduced susceptibility to decapping

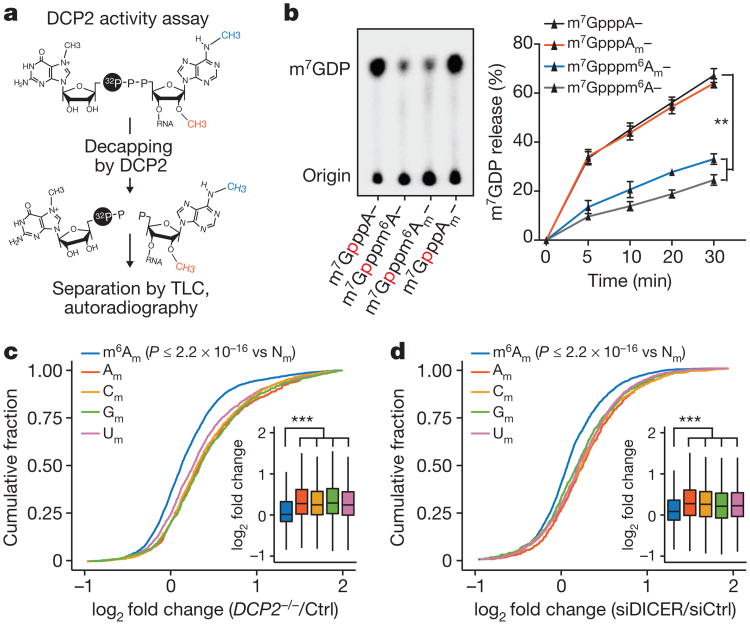

Since mRNA degradation often involves decapping, we considered the possibility that m6Am affects this process. Studies of the mRNA-decap-ping enzyme DCP218 have previously used RNAs with an m7G cap, but did not examine the effect of the methylation state of the subsequent nucleotide. We generated m7G-capped RNAs (m7GpppRNA) with a 32P-labelled γ-phosphate proximal to the m7G. DCP2-mediated decapping releases radiolabelled m7GDP, which was detected by TLC (Fig. 4a, Extended Data Fig. 8a). RNAs containing an m7G cap followed by an unmodified adenosine or Am showed equivalent efficiencies of decapping, indicating that the 2′-O-methyl modification does not affect DCP2-mediated decapping (Fig. 4b). However, RNAs with m7G followed by m6Am or m6A showed significantly reduced decapping (Fig. 4b, Extended Data Fig. 8b).

Figure 4. m6Am mRNAs are resistant to DCP2-mediated decapping.

a, Schematic representation of the DCP2 in vitro decapping assay. The 5′ end of oligonucleotides containing the indicated form of adenosine (A, Am, m6A or m6Am) was enzymatically capped with [α-32P]-m7GTP. DCP2 causes the release of [α-32P]-m7GDP, which is detected by TLC. b, N6-methylation of the cap-adjacent adenosine inhibits mRNA decapping in vitro. The presence of a 2′-O-methyl did not affect DCP2 activity relative to adenosine. However, addition of an N6-methyl group decreased decapping efficiency (n = 3 biological replicates; mean ± s.e.m.; two-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test, **P≤ 0.01). c, DCP2 deficiency primarily increases expression of non-m6Am mRNAs in the HEK293T cell transcriptome. Cumulative distribution plot of the expression of mRNAs that start with m6Am, Am, Cm, Gm and Um (n = 3,287 (m6Am); 2,350 (Am); 3,963 (Cm); 3,540 (Gm); 3,496 (Um); data represent the average from two independent datasets; each box shows the first quartile, median, and third quartile; whiskers represent 1.5 × interquartile ranges; one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test, **P ≤ 2.2 × 10−16 versus m6Am). d, m6Am reduces mRNA susceptibility to microRNA-mediated degradation. Cumulative distribution plot of the expression of mRNAs that start with m6Am, Am, Cm, Gm or Um (n = 2,090 (m6Am); 623 (Am); 1,109 (Cm); 852 (Gm); 1,322 (Um); data represent the average from two independent datasets; each box shows the first quartile, median, and third quartile; whiskers represent 1.5 × interquartile ranges; one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test, **P≤2.2 × 10−16 versus m6Am).

We next asked whether m6Am impairs decapping in cells. We reasoned that DCP2 deficiency would lead to increased Am, Cm, Gm and Um mRNA levels relative to m6Am mRNAs. Transcriptome-wide analysis showed increased levels of mRNAs that start with Am, Cm, Gm or Um in DCP2-deficient HEK293T cells compared to controls (Fig. 4c). m6Am mRNAs were less affected, indicating that they are less susceptible to DCP2-dependent degradation (Fig. 4c). As an additional control, we monitored the stability of individual mRNAs using BrU pulse–chase labelling. Notably, Am mRNAs showed stabilization upon DCP2 depletion, while m6Am mRNAs were not significantly stabilized (Extended Data Fig. 8c). These results suggest that m6Am confers resistance to DCP2, resulting in increased mRNA stability.

m6Am impairs microRNA-mediated mRNA degradation

One unresolved question in microRNA-mediated degradation is why some mRNAs are efficiently degraded by microRNAs while others show less robust degradation19. MicroRNA-mediated mRNA degradation involves decapping20. We therefore asked whether microRNA-mediated degradation could be influenced by the presence of m6Am.

To test this, we examined gene expression data sets of HEK293 cells deficient in DICER and AGO221. In both cases, microRNA-mediated mRNA degradation is impaired, resulting in increased levels of microRNA-targeted mRNAs. If m6Am mRNAs were less susceptible to microRNA-mediated degradation, they would exhibit less-pronounced upregulation upon loss of DICER or AGO2. Indeed, mRNAs starting with Am, Cm, Gm or Um exhibited a significantly higher increase in expression than m6Am mRNAs (Fig. 4d, Extended Data Fig. 8d-f). Thus, m6Am mRNAs are less susceptible to microRNA-mediated degradation.

Next, we asked whether m6Am mRNAs show reduced susceptibility to microRNA-mediated mRNA degradation upon introduction of a single microRNA. We therefore analysed gene expression data sets from miR-155-transfected HeLa cells22 and mRNAs with predicted miR-155-binding sites. This analysis revealed that m6Am mRNAs were significantly more resistant to miR-155-mediated mRNA degradation compared to other mRNAs (Extended Data Figs 8g, h). These data suggest that m6Am reduces the susceptibility of mRNAs to endogenous decay pathways such as microRNA-mediated mRNA degradation.

Discussion

Here we identify m6Am as a dynamic and reversible epitranscriptomic mark. In contrast to the concept that epitranscriptomic modifications are found internally in mRNA, we find that the 5′ cap harbours epitranscriptomic information that determines the fate of mRNA. The presence of m6Am in the extended cap confers increased mRNA stability, while Am is associated with baseline stability. m6Am has long been known to be a pervasive modification in a large fraction of mRNA caps in the transcriptome8, making it the second most prevalent modified nucleotide in cellular mRNA. Dynamic control of m6Am can therefore influence a large portion of the transcriptome.

The concept of reversible base modifications is appealing since it raises the possibility that the fate of an mRNA can be determined by switching a modification on and off. Our data show that FTO is an m6Am ‘eraser’ and forms Am in cells. FTO resides in the nucleus, where it probably demethylates nuclear RNA and newly synthesized mRNAs. Demethylation of cytoplasmic m6Am mRNAs may be induced by stimuli that induce cytosolic translocation of FTO.

The specificity of FTO towards m6Am in cells is supported by the finding that depletion of FTO increases m6Am mRNA levels relative to Am mRNAs, while m6A-containing mRNAs are largely unaffected. Although FTO prefers m6Am, high levels of FTO overexpression cause small but measurable reductions in m6A levels in specific mRNAs23. Additionally, an earlier study reported small increases in total m6A levels in cell lines following FTO knockdown4. m6A measurement in FTO-depleted cells is complicated by the fact that FTO depletion causes increases in m6Am mRNA expression levels, which can lead to indirect changes in m6A levels. Higher mRNA expression also results in increased m6A peak calling owing to the stochastic nature of detecting m6A modifications in low-abundance mRNAs24.

Prior to our recent development of single-nucleotide-resolution m6A and m6Am mapping techniques12, m6A mapping inadvertently included m6Am sites that were misannotated as m6A. These older techniques should more accurately be designated as 6mA mapping (that is, the methylated base) to reflect their inability to distinguish m6Am and m6A. Similarly, m6A immunoblot and m6A-IP qRT-PCR cannot distinguish between m6A and m6Am. We find that the upregulated peaks in the Fto-knockout transcriptome11, which are enriched in the 5′ UTR, probably reflect FTO-regulated m6Am sites. A similar increase in 5′ UTR peaks was reported in a m6A mapping study of Fto-deficient mouse fibroblasts25. The 5′ UTR enrichment of these peaks suggests that these residues may also reflect m6Am.

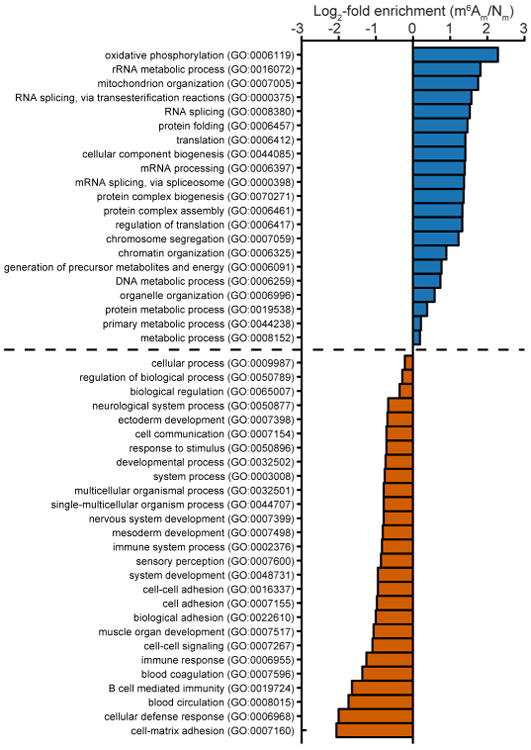

Previous studies on FTO should be reconsidered in light of its preferential activity towards m6Am. FTO has been linked to altered splicing of mRNAs, which may indicate a role for m6Am in this process26. FTO knockdown increases the translation of HSPA1A23,25. Although site-directed mutagenesis supports a role for 5′ UTR m6A in the translation of this mRNA25, m6Am also probably contributes to this effect owing to its sensitivity to FTO. FTO-deficient mice display diverse phenotypes ranging from growth retardation to metabolic changes and abnormalities in brain reward pathways11,27. Humans with FTO loss-of-function mutations exhibit growth retardation and malformations28. Since m6Am mRNAs are enriched in functional categories linked to RNA splicing, translation and metabolism (Extended Data Fig. 9), alterations in these pathways may contribute to the physiological effects of FTO deficiency.

DCP2 is a ‘reader’ of the mRNA cap modification state, thereby contributing to the stability of m6Am mRNAs. m6Am impairs mRNA decapping, rendering m6Am mRNAs less susceptible to microRNA-mediated mRNA degradation. Therefore, m6Am probably contributes to the poorly understood variability in mRNA responses to microRNAs seen in cells29.

The effects of m6Am contrast with those of m6A. While m6Am exhibits a stabilizing effect, m6A is associated with enhanced mRNA degradation (ref. 30). However, both m6Am and m6A residues in the 5′ UTR are linked to increased translation23, suggesting that these different methylated forms of adenosine in the 5′ UTR enhance translation initiation. Thus, the location of the modified nucleotide and the specific combination of methyl groups on adenosine residues encode distinct functional consequences on the mRNA.

Online Content

Methods, along with any additional Extended Data display items and Source Data, are available in the online version of the paper; references unique to these sections appear only in the online paper.

Methods

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. The experiments were not randomized and the investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Synthesis and characterization of synthetic oligonucleotides

The sequences of all the oligonucleotides used in this study are shown in Supplementary Table 4. The oligonucleotide containing an internal N6-methyladenosine (m6A) in a DRACH context was synthesized by TriLink BioTechnologies.

All other synthetic RNA oligonucleotides were chemically assembled on an ABI 394 DNA synthesizer (Applied Biosystems) from commercially available long-chain alkylamine controlled-pore glass (LCAA-CPG) solid support with a pore size of 1,000 Å derivatized through the succinyl linker with 5′-O-dimethoxytrityl-2′-O-Ac-uridine (Link Technologies). All RNA sequences were prepared using phosphoramidite chemistry at 1 μmol scale in Twist oligonucleotide synthesis columns (Glen Research) from commercially available 2′-O-pivaloyloxymethyl amidites (5′-O-DMTr-2′-O-PivOM-[U, CAc, APac or GPac]-3′-O-(O-cyanoethyl-N,N-diisopropylphosphoramidite)31 (Chemgenes). The 5′ terminal adenosine can be unmodified A, or methylated in 2′-OH (Am), or in N6 position (m6A) or in both positions (m6Am). The 5′-O-DMTr-2′-O-Me-APac-3′-O-(O-cyanoethyl-N,N-diisopropylphosphoramidite) (Chemgenes) was used to introduce Am at the 5′-end of RNA. For the production of m6A-RNAs or m6Am-RNAs, the preparation of m6A and m6Am phosphoramidite building blocks was performed by a selective one-step methylation of the commercially available 2′-O-PivOM-Pac-A-CE phosphoramidite or 2′-O-Me-Pac-A-CE phosphoramidite, respectively. All oligoribonucleotides were synthesized using standard protocols for solid-phase RNA synthesis with the PivOM methodology32.

After RNA assembly, the 5′-hydroxyl group of the 5′-terminal adenosine (A): A, Am, m6A or m6Am of RNA sequences, still anchored to solid support, was phosphorylated and the resulting H-phosphonate derivative was oxidized and activated into a phosphoroimidazolidate derivative to react with either pyrophosphate (for ppp(A)-RNA synthesis)33 or guanosine diphosphate (for Gppp(A)-RNA synthesis)34. To obtain the monophosphate of m6Am-RNA (pm6Am-RNA), the 5′-H-phosphonate RNA was treated with a mixture of N,O-bis-trimethylacetamide and triethylamine in acetonitrile, and then oxidized with a tert-butyl hydroperoxide solution35.

After deprotection and release from the solid support upon basic conditions (DBU then aqueous ammonia treatment for 4 h at 37 °C), all RNA sequences were purified by IEX-HPLC36, they were obtained with high purity (>95%) and they were unambiguously characterized by MALDI-TOF spectrometry (Supplementary Table 4).

N7 methylation of the purified Gppp(A)-RNAs to give m7Gppp(A)-RNAs was carried out quantitatively using human mRNA guanine-N7-methyltransferase and S-adenosylmethionine as previously described34.

Measurement of enzymatic properties of FTO in vitro

Demethylation measurements were performed essentially as described previously4, with the exception that all reactions were carried out at 37 °C. The demethylation activity assay was performed in 20-50 μl of reaction mixture containing the indicated quantities of synthetic RNA oligonucleotide or mRNA, the indicated quantities of FTO, 75 mM of (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2, 300 mM α-ketoglutarate, 2 mM sodium L-ascorbate, 150 mM KCl and 50 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.0. The reaction was incubated at 37 °C for the indicated times, quenched by the addition of 1 mM of EDTA followed by inactiva-tion of the enzymes for 5 min at 95 °C.

Sample preparation for HPLC analysis

After demethylation by FTO, oligonucleotides were decapped with 25 units of RppH (NEB) in ThermoPol buffer for 2 h at 37 °C. RNA was subsequently digested to single nucleotides with 180 units of S1 nuclease (Takara) for 1 h at 37 °C. 5′ phosphates were removed with 5 units of rSAP (NEB) for 1 h at 37 °C. Before loading the samples onto the HPLC column, proteins were removed by size-exclusion chromatography with a 10 kDa cut-off filter (VWR).

HPLC analysis of demethylation activity

The HPLC analysis of nucleosides was performed on an Agilent 1100 system (Agilent Technologies). Separation was performed on a Poroshell 120 EC-C18 column (4μm, 150 × 4.6 mm, Agilent Technologies) equipped with an EC-C18 Guard cartridge (Agilent Technologies) at 22 °C. The mobile phase consisted of buffer A (25 mM NaH2PO4) and buffer B (100% acetonitrile). Pump control and peak integration was achieved using the ChemStation software (Rev. A.10.02, build 1757, Agilent Technologies). Samples were analysed at 2 ml min−1 flow rate with the following buffer A/B gradient: 7.5 min 95%/5%, 0.5 min 90%/10%, 2 min 10%/90%, 1 min 95%/5%. Retention times of the individual nucleosides was determined with synthetic standards (3.2 min for adenosine (A), 5.8 min for 2′-O-methyladenosine (Am), 5.9 min for N6-methyladenosine (m6A), 7.9 min for N6,2′-O-dimethyladenosine (m6Am). Guanosine was used as an internal control. After normalization of each peak area to the area of the guanosine peak area, the relative and absolute amount of individual nucleotides in each sample was determined based on the sequence of the input oligonucleotide.

Sample preparation for mass spectrometry

m6Am demethylation intermediates were generated essentially as described previously13, with the difference that all reactions were carried out at 37 °C. Capped oligonucleotides were incubated with 100 nM FTO for 10 min at 37 °C followed by digestion with 2 units of P1 nuclease for an additional 15 min. Notably, P1 nuclease does not cleave the triphosphate linker of the cap and thus specifically releases the m7Gpppm6Am dinucleotide, while digesting the RNA backbone down to single nucleotides. To preserve the unstable demethylation intermediates13, the nucleotide mixture was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen until further analysis.

Detection of demethylation intermediates by mass spectrometry

FTO reaction products were extracted by cold 80% methanol:H2O at 1:20 volume ratio. After removal of precipitated protein, 4 μl of supernatant was injected into LC/MS for accurate mass measurement of demethylation intermediates. The LC/MS-MS system comprised an Agilent Model 1260 Bio-inert infinity liquid chromatography system coupled to an Agilent iFunnel 6550 quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer. Chromatography of the reaction products was performed using aqueous normal phase (ANP) gradient separation, on Cogent Diamond Hydride (ANP) column (2.1 × 150 mm, 3.5 μm particle size; Microsolv Technology Corp). A precolumn filter (0.5 μm, Microsolv) was placed in front of the ANP column, to prevent column clogging. Mobile phases consisted of: (A) 50% isopropanol, containing 0.025% acetic acid; and (B) 90% acetonitrile containing 5 mM ammonium acetate. To eliminate the interference of metal ions on the chromatographic peak integrity and electrospray ionization, EDTA was added to the mobile phase at a final concentration of 6 μM. The following gradient was applied: 0-1.0 min, 99% B; 1.0-15.0 min, to 20% B; 15.0–29.0 min, 0% B; 29.1-37 min, 99% B. To minimize potential salt and other contaminants in the ESI source, a time segment was set to direct the first 0.5 min of column elute to waste.

Negative ion mass spectra in both profile and centroid mode were acquired in 2 GHz (extended dynamic range) mode, scanned at 1 spectrum per second over a mass/charge range of 20–1,000 Daltons. The QTOF capillary voltage was set 3,500 V and the fragmentor was set to 140 V. The nebulizer pressure was 35 p.s.i. and the nitrogen drying gas was 200 °C, delivered at a flow rate of 14 l min−1. The sheath gas temperature was at 350 °C with sheath gas flow of 11 l min−1. Raw data was analysed with Agilent MassHunter Qualitative Analysis software (version B6.0). Profile data was used to provide measured mass.

Cell culture and animals

HEK 293T/17 (ATCC CRL-11268; passage number 3-10; no further verification of cell line identity was performed) cells were maintained in DMEM (11995-065, ThermoFisher Scientific) with 10% FBS and antibiotics (100 units ml−1 penicillin and 100μg ml−11 of streptomycin) under standard tissue culture conditions. Cells were split using TrypLE Express (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Mycoplasma contamination in cells were routinely tested by Hoechst staining. To obtain embryonic day (E) 14 Fto-knockout mouse embryos and livers, Fto-knockout mice were bred as previously described27. Only male animals were used in the current study. All experiments involving mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Weill Cornell Medical College.

Antibodies

Antibodies used for western blot analysis or immunostaining were as follows: rabbit anti-DDDDK/Flag (ab1162, Abcam), rabbit anti-FTO (ab124892, Abcam), rabbit anti-GAPDH (ab9485, Abcam), mouse anti-ALKBH5 (ab69325, Abcam), mouse (β-actin (A2228, Sigma) and goat anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 546 (A11035, ThermoFisher Scientific). For m6A individual-nucleotide-resolution cross-linking and immunoprecipitation (miCLIP), rabbit anti-m6A (ab151230, Abcam) was used. An in-house-generated rabbit anti-DCP2 serum was used for detection of DCP2.

Knockdown and overexpression studies in HEK293T cells

FTO and ALKBH5 knockdown experiments were carried out in HEK293T cells using either Pepmute transfection reagent (Signagen) or Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (ThermoFisher Scientific) with 20 nM dsiRNA duplex directed against FTO (HSC.RNAI. N001080432.12.1, Integrated DNA Technologies) or 50 nM Silencer Select siRNA duplex pool targeting ALKBH5 (s29686, s29687, s29688, ThermoFisher Scientific), respectively. Scrambled siRNA was used as non-targeting control.

FTO and ALKBH5 expression experiments were carried out in HEK293T cells using LipoD293 transfection reagent (Signagen) with Flag-tagged full length human wild-type FTO, human wild-type FTO containing a Flag tag and two nuclear export signals (NES) at the N terminus, GST-tagged ALKBH5 lacking 66 N-terminal amino acids, or respective control vectors.

Cells were maintained at 70-80% confluency and harvested 48-72 h after the transfection. Knockdown and overexpression were confirmed by western blot. Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (ThermoFisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. If indicated, two rounds of poly(A) mRNA enrichment from total RNA was carried out with oligo d(T)25 Magnetic Beads (NEB) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunostaining of HEK293T cells

HEK293T cells transfected with either Flag-tagged full-length human wild-type FTO or human wild-type FTO containing two nuclear export signals (NES) at the N terminus were grown on cover slips coated with poly-d-lysine, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PEM buffer (80 mM potassium PIPES, 5 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgCl2, pH 7.0) for 10 min and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PEM buffer for 30 min. After blocking with 1% BSA in TBS-T for 1 h, cells were incubated with anti-DDDDK/Flag antibody (1:1,000 dilution in 1% BSA TBS-T) for 2 h followed by incubation with a goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:1,000 dilution in 1% BSA TBS-T) for 1 h. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. All immunostaining steps were carried out at room temperature. Image acquisition was carried out on a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope (Nikon), using NIS-Elements AR software (Version 3.2).

Generation of DCP2 CRISPR knockout cells

DCP2-knockout cell lines were generated by CRISPR/Cas9 technology using two guide RNAs (gRNAs; 5′-UAUCAAAGACUAUAUUUGUA-3′ and 5′-AACCAGUUUCUUCAAAG ACC-3′) designed to target the DCP2 genomic region corresponding to its catalytic site. Double-stranded DNA oligonucleotides corresponding to the gRNAs were inserted into the pSpCas9n(BB)-2A-Puro vector (Addgene). Equal amounts of the two gRNA plasmids were mixed and transfected into HEK293T cells using FuGENE 6 (Promega). The transfected cells were then subject to puromycin selection for three days and viable cells were used for serial dilution to generate single-cell clones. The genomic modification was screened by PCR and sequencing. In DCP2-knockout line 1, the two alleles were disrupted to generate out-of-frame mutation after V145 and I153, respectively. Line 2 contained a 55 nt homozygous deletion that removed the splicing site between intron 4 and exon 5. Line 3 contained one allele with a 194 nt deletion that removed the splicing site between intron 4 and exon 5, and the other allele was disrupted to generate out-of-frame mutation after V145. Loss of DCP2 protein expression was confirmed by western blot with in-house-generated anti-DCP2 sera37.

Protein expression and purification

N-terminal HIS-tagged human FTO was generated by standard PCR-based cloning strategy and its identity was confirmed by sequencing FTO as described previously4, with minor modifications. FTO was overexpressed in E. coli BL21 Rosetta (DE3) using pET-28(+) (Novagen). Cells expressing FTO were induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl (3-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 16 h at 18 °C. Cells were collected, pelleted and then resuspended in buffer A (50 mM NaH2PO4 pH 7.2, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole-HCl pH 7.2, 5 mM (3-mercaptoethanol). The cells were lysed by sonication and then centrifuged at 10,000g for 20 min. The soluble proteins were purified using Talon Metal Affinity Resin (Contech) and eluted in buffer B (50 mM NaH2PO4 pH 7.2, 300 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole-HCl pH 7.2, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol). Further concentration and purification was performed using Amicon Ultra-4 spin columns (Merck-Millipore). Recombinant protein was stored in enzyme storage buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol) at -80 °C. All protein purification steps were performed at 4 °C.

Determination of relative m6Am, Am and m6A levels by thin layer chromatography

Levels of internal m6A in mRNA were determined by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) essentially as previously described4. In brief, poly(A) RNA (100 ng) was digested with 2 units of RNase T1 (ThermoFisher Scientific) for 2 h at 37 °C in the presence of RNasin RNase Inhibitor (Promega). T1 cuts after every guanosine and exposes the 5′-hydroxyl of the following nucleotide, which can be A, C, U or m6A. Thus, this method quantifies m6A in a GA sequence context. 5′ ends were subsequently labelled with 10 units of T4 PNK (NEB) and 0.4 mBq [γ-32P] ATP at 37 °C for 30 min followed by removal of the γ-phosphate of ATP by incubation with 10 units Apyrase (NEB) at 30 °C for 30 min. After phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation, RNA samples were resuspended in 10 μl of DEPC-H2O and digested to single nucleotides with 2 units of P1 nuclease (Sigma) for 3 h at 37 °C. 1 μl of the released 5′ monophosphates from this digest were then analysed by 2D TLC on glass-backed PEI-cellulose plates (MerckMillipore) as described previously14.

The protocol to detect the m6Am:Am ratio was based on the protocol developed by Fray and colleagues14, with some modifications. Poly(A) RNA (1 μg) was used for the assay. Free 5′-OH ends were phosphorylated using 30 units of T4 polynucleotide kinase (PNK, NEB) and 1 mM ATP, according to the manufacturer's instructions. 5′ phosphorylated RNA fragments were digested with 2 units of Terminator 5′-Phosphate-Dependent Exonuclease (Epicentre). Capped RNAs are unaffected by this treatment. After phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation, RNA samples were resuspended in 10 μl of DEPC-H2O and 400 ng of the RNA was decapped with 25 units of RppH (NEB) for 3 h at 37 °C The 5′ phosphates of the exposed cap-adjacent nucleotide were removed by the addition of 5 units of rSAP (NEB) and further incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. Up to this point, all enzymatic reactions were performed in the presence of SUPERase In RNase Inhibitor (ThermoFisher Scientific). After phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation, RNA samples were resuspended in 10 μl of DEPC-H2O and 5′ ends were labelled using 30 units T4 PNK and 0.8 mBq [γ-32P] ATP at 37 °C for 30 min. PNK was heat inactivated at 65 °C for 20 min and the reaction was passed through a P-30 spin column (Bio-Rad) to remove unincorporated isotope. 10 μl of labelled RNA were then digested with 4 units of P1 nuclease (Sigma) for 3 h at 37 °C. 4 μl of the released 5′ monophosphates from this digest were then analysed by 2D TLC on glass-backed PEI-cellulose plates (MerckMillipore) as described previously14.

Signal acquisition was carried out using a storage phosphor screen (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) at 200 μm resolution and ImageQuantTL software (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Quantification was carried out with ImageJ (V2.0.0-rc-24/1.49 m). For m6Am experiments, the m6Am:Am ratio was calculated. The use of this ratio has been described previously14. We confirmed that this assay is linear by spotting twice the sample material and confirming that the signal intensity doubles for the unmodified nucleotides (A, C and U). Furthermore, exposure time of the TLC plates to the phosphor screen was chosen so that the signal was not saturated. For m6A quantification, m6A was calculated as a percentage of the total of the A, C and U spots, as described previously4. The use of relative ratios for each individual sample is important since it reduces the error derived from possible differences in loading. To minimize the effects of culturing conditions on the measured m6Am/Am ratios of each experimental group (for example, control versus knockdown), all replicates were processed in parallel to minimize any source of variability between samples being compared. Of note, the control conditions for siRNA transfection and plasmid transfection utilize different transfection reagents, which could affect baseline m6Am/Am ratios.

In vitro decapping assays

22-nucleotide-long RNA oligonucleotides that have an A, Am, m6A or m6Am at their 5′ end were enzymatically capped with the vaccinia capping enzyme with [α-32P]-N7-methylguanosine triphosphate (m7GTP) as previously described38. Decapping reactions were carried out according to ref. 38. In brief, 10 nM recombinant DCP2 protein was incubated with the indicated cap-labelled RNAs in decapping buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 0.5 mM MnCl2, 40 U ml−1 recombinant RNase inhibitor) and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Reactions were stopped with 25 mM EDTA at the indicated time points. The identity of decapping products of the indicated modified cap adenosines subjected to 20 nM recombinant human DCP2 protein at 37 °C for 30 min were confirmed to be m7GDP by treatment with 0.5 U nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDPK) at 37 °C for 30 min in the presence of 0.5 mM ATP. A cap labelled RNA with a guanosine as the first nucleotide generated as previously described38 was used as a positive control. Decapping products were resolved by PEI-cellulose TLC plates (Sigma-Aldrich) and developed in 0.45 M (NH4)2SO4 in a TLC chamber at room temperature. Reaction products were visualized and quantitated with a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager (Storm860) with ImageQuant-5 software.

Synthesis of mRNAs with specific forms of methylated caps

To generate mRNAs that begin with either m7GpppAm or m7Gpppm6Am, we used thermostable TGK polymerase39, which enables RNA synthesis with an RNA primer from a DNA template. The primers contained either m7GpppAm or m7Gpppm6Am as the extended cap. The use of TGK polymerase and specific methylated forms of the primer ensures that all synthesized mRNAs begin with the desired extended cap structure. The DNA template for RNA synthesis was prepared by PCR using the pNL1.1[Nluc] vector (Promega) as a template and Phusion High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix (NEB). Since the template needs to be single-stranded, we used a strategy of selectively degrading one of the strands of the PCR product. To achieve this, PCR was performed with a 5′-phosphorylated forward primer and a 5′-OH reverse primer. The undesired 5′-phosphorylated strand was digested with lambda exonuclease (Lucigen) (1 U per 1–2 μg double-stranded DNA) for 2 h at 37 °C. The digestion was stopped by phenol chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation of the single-strand template.

RNA forward synthesis was performed from either an m7GpppAm (20 nt) or an m7Gpppm6Am (20 nt) primer in a 50 μl reaction consisting of 1 × Thermopol buffer (NEB) supplemented with 3 mM MgSO4 and 2.5 mM NTP with a 1:1 primer/ template ratio at 100 pmol each and 150 nM TGK polymerase. The primer extension was performed at two cycles of 10 s at 94 °C, 1 min at 50 °C, and 1 h at 65 °C. After RNA synthesis, the template DNA strand was degraded using TURBO DNase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and the capped nLuc mRNAs were purified with an RNeasy column (Qiagen). An approximately 250 nt poly(A) tail was added with A-Plus Poly(A) Polymerase Tailing Kit (Cellscript). The polyadenylated mRNAs were purified with oligo d(T)25 Magnetic Beads (NEB) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Electroporation of mRNA

To deliver m7GpppAm-nLuc and m7Gpppm6Am-nLuc mRNAs into HEK293T cells, we used electroporation. HEK293T cells were trypsin-ized and resuspended in Ingenio Electroporation Solution (Mirus) at 5 × 106 cells ml−1. 100 μl of cell suspension was added to 2 μg of mRNA. Electroporation was carried out with Nucleofector II (Amaxa) using program Q-001. The cell suspension was immediately transferred to 37 °C pre-warmed growth medium supplemented with 5 mM CaCl2 and 200 U ml−1 micrococcal nuclease (Clontech). After a 15 min incubation period at 37 °C to remove any residual extracellular RNA, cells were transferred to 24-well plates at 1.25 × 105 and incubated until adherent. Cells were then either collected immediately or after 2 h of incubation for RNA extraction and quantification by qRT-PCR.

RNA half-life measurement after transcriptional inhibition

RNA half-lives after transcriptional inhibition were determined essentially as previously described40,41. In brief to achieve transcriptional inhibition for calculation of mRNA half-life, Flag- and NES-FTO-transfected HEK293T cells were either left untreated (that is, 0 h time point) or treated with actinomycin D (Sigma) for 6 h at a final concentration of 5 μg ml−1. Cells were then harvested for RNA isolation using TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The total RNA derived from Flag- and NES-FTO-transfected HEK293T cells, was spiked-in with ERCC RNA controls (Ambion) before the isolation of mRNA and RNA-seq (see below). Read count tables were generated using STAR aligner42. DESeq243 was used to calculate ERCC spike-in RNA size factors, which were then applied to normalize for library size changes in each replicate. As shown in Extended Data Fig. 6c, the half-lives derived from the transcriptional inhibition experiments showed high correlation between independent replicates.

RNA half-life measurements by 5-bromouridine (BrU) pulse-chase

RNA half-life measurements by BrU pulse-chase was carried out essentially as described previously44. Briefly, HEK293T cells were pulsed with 150 μM 5-bromouridine (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 24 h. Chase was initiated by changing to medium containing 1.5 mM uridine (Sigma) and cells were collected for RNA extraction after 6 and 16 h. BrU-pulsed cells without uridine-chase were used as basal (0 h) controls. Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturers instructions. Immunoprecipitation of BrU-labelled RNA from total RNA was carried out as previously described44. A BrU-labelled NanoLuc luciferase (nLuc) RNA was generated by in vitro transcription as previously described44 and used as a spike-in immunoprecipitation control at 10 pgp per 1 μg input RNA.

Quantitative real-time PCR

1–2 μg total RNA or 500 ng BrU-labelled RNA was reverse transcribed using the High Capacity cDNA Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cDNA was subjected to quantitative real-time PCR analysis with the TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using Taqman Gene Expression Assays (Thermo Fisher Scientific) on a ViiA 7 Realtime-PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The following predesigned Taqman Gene expression assays were used in the current study: FUCA1 (Hs00609173_m1), MAGOHB (Hs00970279_m1), PCNA (Hs00427214_g1), PCK1 (Hs01572978_g1), PSMD3 (Hs00160646_m1), SCFD2 (Hs00293797_m1).

ACTB (Hs01060665_g1) was used as a housekeeping gene to normalize the level of transfected nLuc mRNA. A custom probe and primer set was designed to detect nLuc cDNA (forward 5′-ATGTCGATCTTCAGCCCATTT-3′; reverse 5′-GGA GGTGTGTCCAGTTTGTT-3′; probe 5′-/56-FAM/ATCCAAAGGATTGTC CTGAGCGGT/3IABkFQ/-3′). Amplification of nLuc cDNA was linear over seven orders of magnitude. The 2−ΔΔCt method was used to calculate relative gene expression changes between time points and biological replicates.

m6A peak enrichment analyses

m6A peaks were based on our previous MeRIP-seq analysis of Fto-knockout midbrain tissue11. For analysis of m6A peak distribution, m6A peaks were individually binned based on their location within mRNA and mapped onto a virtual transcript in a metagene analysis to show their collective distribution within mRNA. Bin numbers were chosen such that each bin is on average 50 nucleotides long. Peak counts were smoothed using a spline function. We weighted each peak by a coefficient corresponding to the number of MeRIP-seq reads in the immunoprecipitated samples relative to the reads obtained before immunoprecipitation. This peak mass value represents the enrichment of methylated mRNA at individual m6A sites after immunoprecipitation and reflects the degree to which an mRNA is methylated at a particular m6A site. To generate the peak height ratio plot, we used ratios between Fto-knockout peak mass over wild-type peak mass. The same bin numbers and sizes were used for all analyses.

Mapping and validation of m6Am sites

To further increase the number of miCLIP-based detection of m6Am sites, we used the miCLIP pipeline12 with the following modifications. Raw miCLIP reads were trimmed of their 3′ adaptor and demultiplexed as previously described12. Then, PCR-duplicated reads of identical sequences were removed using the pyDuplicateRemover.py script of the pyCRAC tool suite (version 1.2.2.3). Unique reads were mapped with Bowtie (version 1.1.1) to hg19. Files of aligned reads were processed with samtools (version 1.2), bedtools (version 2.25.0), and custom bash commands to derive the 5′ ends of each aligned read. 5′-end coordinates of the reads were then combined into ‘piles’ at each single nucleotide throughout the genome using the tag2cluster.pl script of the CIMS software package45 (parameters: -v -s -maxgap “-1”). Piles were then filtered to contain at least five 5′ ends at a single nucleotide. Adjacent piles (zero nucleotides apart) were clustered together using a custom perl script. The resulting clusters were annotated with their transcript ID and transcript region (5′ UTR, CDS, or 3′ UTR) using a custom perl script and custom bash commands. After annotation, clusters were filtered for those found in the 5′ UTR of annotated mRNAs. To remove noise, clusters with a width of one nucleotide were removed using custom bash commands. Finally, custom bash commands were used to filter for clusters found only at the very beginning of 5′ UTRs.

To verify that these are indeed m6Am residues, we took advantage of fact that m6Am occurs only at transcription start sites (TSS). Thus, we compared the known TSS and transcription initiation sequences around each m6Am-containing region. To identify genome-wide positions of the TSS from published CAGE-seq datasets16 and genome-wide positions of the consensus initiator motif, YYANW (Y = C or T, N = A, C, G, or T, W = A or T)46, a custom perl script was used. The CAGE sites in this data set are combined from RLE (relative log expression)-normalized robust CAGE-seq analysis of multiple cell lines and tissues, and therefore provide high sensitivity for detecting transcription start sites.

We then determined the distribution of TSS or the YYANW sequence around m6Am-containing regions. To do so, we used the ‘closest’ tool of the bedtools suite to determine distances between each m6Am-containing region and the nearest TSS or YYANW sequence. The following commands were used to find TSS or YYANW sequences nearest to the 5′-most nucleotide of each m6Am-containing region.

To measure the distance of TSS or YYANW sequences that overlap with m6Am-containing regions:

bedtools closest -a m6Am.reference.points.bed -b feature.locations.bed -s > m6Am.distance.overlap.bed

To measure the distance of TSS or YYANW sequences that do not overlap with m6Am-containing regions:

bedtools closest -a m6Am.reference.points.bed -b TSS.locations.bed -s -io > m6Am.feature.distance.bed

The total distributions of the distances of TSS or YYANW sequences to m6Am-containing regions (regardless of overlap) were then plotted as a histogram.

These results demonstrated that TSS and the YYANW core initiator sequence are highly clustered at m6Am-conaining regions. This suggests that the called m6Am-containing regions reflect true transcription initiation sites. All newly identified m6Am mRNAs are listed in Supplementary Table 1 together with CAGE and initiator overlap. Notably, m6Am sites are distinct from the recently described 5′ UTR m6A sites23 since they are found in a different sequence context and overlap with transcription start sites12. Furthermore, the previously described ex vivo m1A to m6A conversion is unlikely to generate artefacts during m6A mapping. m1A to m6A conversion requires extreme conditions47 that are not used in miCLIP or MeRIP-seq. Additionally, m6A peaks are not detected at the annotated m1A site in the 28S rRNA12, indicating that no detectable m1A to m6A conversion is occurring during miCLIP.

At present, it is not possible to determine the absolute stoichiometry of m6Am or Am at the first position of mRNA at a transcriptome-wide level. Conceivably, if the stoichiometry of m6Am is not 100% on a specific m6Am-classified mRNA, the effect of m6Am may be underestimated. For experiments using BrU pulse-chase labelling, we sought to examine mRNAs with high stoichiometry m6Am. As a surrogate for stoichiometry, we measured the miCLIP/RNA-seq ratio in a 20 nt window surrounding the 5′ m6Am region using bedtools coverage. For qRT-PCR analysis in the BrU pulse-chase experiments examining individual mRNA half-life changes upon NES-FTO expression, m6Am mRNAs with high miCLIP/RNA-seq ratio were chosen (Supplementary Table 5).

Classification of mRNAs based on the first nucleotide

In experiments where we compared m6Am-intiated mRNAs to Am-, Cm-, Gm- and Um-initiated mRNAs, we classified the mRNAs based on the nucleotide at the annotated TSS. Annotated TSS were extracted from the Ensembl BioMart database48. A complete list of transcripts with their respective annotated transcription start site is found in Supplementary Table 2.

Metagene analysis using miCLIP reads

For Extended Data Figs 6f g, we generated a high-coverage m6A individual-nucleotide-resolution cross-linking and immunoprecipitation (miCLIP) data set in HEK293T cells12. Metagenes were constructed for the miCLIP-identified unique 6mA reads using an in-house perl annotation pipeline and custom R scripts. Briefly, the 6mA reads were mapped to different RNA features (5′ UTR, CDS and 3′ UTR) of the human genome (hg19). Position of the reads was normalized to the median feature length of the RNAs to which the tag mapped. A frequency distribution plot was generated by counting number of reads in contiguous bins on a virtual mRNA transcript, whose feature lengths represent the median feature lengths of RNAs under analysis either of each individual sample or of the control sample. A kernel density (Gaussian) estimate was plotted.

RNA-seq analysis

To avoid potential clonal variation, 106 cells from each of the three DCP2 CRISPR lines were pooled together (referred to as DCP2-knockout cells), passaged once, and immediately used for RNA-seq. The DCP2 CRISPR line RNA samples were subject to depletion of ribosomal RNA using RiboMinus Eukaryote System v.2 (Life Technologies), followed by cDNA library preparation using the Illumina TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kit v.2. The sequencing (2 × 100-bp paired-end) was performed by RUCDR Infinite Biologics (Piscataway) using the Illumina Hiseq 2500 according to the manufacturer's protocol. Two independent biological replicates were sequenced for each condition. The RNA-seq library for miCLIP normalization (see ‘Mapping and validation of m6Am sites’) was prepared using a cloning strategy parallel to the one used in miCLIP12,49.

For all other RNA-seq analyses, total RNA was diluted to a concentration of 50 ng μl−1 and submitted to the Weill Cornell Medicine Epigenomics Core for isolation of mRNA and library preparation using the Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep Kit (RS-122-2101, Illumina). The libraries were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 instrument, in either single-read or paired-end mode, with 50-100 bases per read. At least two independent biological replicates were sequenced for each condition.

Gene expression was measured using STAR42 read counts (version 2.4.1; -quantMode TranscriptomeSAM GeneCounts), which were processed with either the DESeq2 pipeline43 (version 1.8.1) or the RSEM pipeline50 (version 1.2.25). Analysis and visualization of RNA-seq datasets was carried out with custom in-house-generated R scripts using RStudio (Version 0.99.489). Only transcripts with normalized read counts > 1 were included in the analyses.

Previously published RNA-seq datasets used in the current study were extracted from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, NCBI) and, if no processed data was available, the fastq files were reanalysed with the pipelines described above. mRNA half-life data was either calculated based on the decay rates derived from our own HEK293T cell data set or was extracted from previously published half-life data sets in HeLa cells40. Only mRNAs with a half-life between 0 h and 25 h were used in our analysis of mRNA half-life based on the identity of the first encoded nucleotide. For classification of short- and long-lived mRNAs, half-life values were divided into quartiles. mRNAs in the lowest quartile (0–3 h) were defined as short-lived, whereas mRNAs in the highest quartile (10–24 h) were defined as long-lived. The analysis of DICER- and AGO2-knockdown effects on m6Am mRNAs was performed using previously published datasets20. We used m6Am mapped in mouse liver12 in order to correspond with the mouse liver expression analysis in these datasets. When indicated, we limited the analysis to mRNAs with TargetScan-predicted microRNA-binding sites and a context score cut-off ≤ 0.1 (ref. 51). Non-target mRNAs in Extended Data Fig. 9f were filtered for mRNAs that contain 3′ UTR sizes ≤300 nt to reduce the likelihood of analysing mRNAs with alternative 3′ UTRs or alternative polyadenylation sites. The analysis of the effect of single microRNA transfection on m6Am mRNAs was performed using previously published datasets of miR-155 duplex transfected HeLa cells21. In these experiments, we limited the analysis to CLIP-supported microRNA-mRNAs interactions according to starBase v.2.052.

Ribosome profiling

To determine if m6Am is associated with changes in translation efficiency, we analysed a previously published ribosome profiling dataset53. Ribosome footprint reads and corresponding RNA-seq reads were processed essentially as described54. First, adaptors were trimmed using Flexbar v.2.5. For ribosome footprints, only reads from which the adaptor was trimmed were retained. Reads mapping to ribosomal RNAs were removed with bowtie v.1.1.2. Remaining reads were then aligned to the hg19 genome with STAR v.2.5.2a in a splicing-aware manner and using UCSC refSeq as a transcript model database (version from 2 June 2014 downloaded from Illumina iGenomes). Two mismatches were allowed and only unique alignments were reported. Aligned reads were then counted on transcript regions using custom R scripts considering only transcripts with annotated 5′ and 3′ UTRs. Translation efficiency was calculated as previously described21, with pre-filtering for transcripts that had at least ten counted reads.

Statistics and software

P values were calculated with a two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test or, for the comparison of more than two groups, with a one- or two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's or Tukey's post hoc test. Reproducibility of half-life and translation efficiency measurements was assessed by calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient between replicates. The influence of covariates on the effect of m6Am-containing mRNAs compared to non-m6Am mRNAs on mRNA half-life was studied by ANCOVA analysis using SPSS Statistics software (IBM, v.22). The covariates include the number of mRNA-destabilizing AU-rich, GU-rich and U-rich elements55, gene expression (log2[FPKM], FPKM > 1), translation efficiency (log2[TE], TE > 0), GC composition and length of 5′ and 3′ UTR, number of exons in 5′ and 3′ UTRs, number of conserved miRNA target sites (PCT > 0)56, minimum-free energy to length ratio57, and the number of G-quadruplexes in the 5′ UTR58,59. GC composition, UTR lengths, and the number of exons were calculated from refseq mRNA annotations (hg19) from the UCSC Genome browser. P values of 0.05 or less were considered significant. Initial reaction velocities for enzyme kinetics were analysed by nonlinear regression curve-fitting using Graphpad Prism software (version 5.0f) to obtain kcat, Km and Vmax. Gene Ontology (GO) functional annotation was performed using PANTHER Overrepresentation Test (release 20150430) and Bonferroni correction with a P value threshold of <0.01. Non-m6Am-containing mRNAs were used as the background gene list.

Code availability

The custom Perl and R scripts used in this study are available on request from the corresponding author (S.R.J.).

Data availability

Sequencing data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the GEO database under accession number GSE78040. A summary of all the data sets used in the current study can be found in Supplementary Table 6.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. m6A enrichment is increased within the 5′ UTR of Fto-knockout mice relative to wild-type mice and FTO prefers m6Am over m6A.

a, m6A peak mass was calculated for all peaks that were found in both Fto-knockout mice (Fto−/−) and wild-type (WT) mice. The ratio of each individual peak's mass relative to the average peak mass for each sample was then determined, providing a relative peak mass. The relative peak mass for Fto−/− mice was divided by the relative peak mass for wild-type mice for each m6A peak. A metagene analysis was performed to plot the distribution of these peak mass ratios (knockout/wild type) along the length of an mRNA. This analysis reveals that the changes in peak mass ratio for knockout mice relative to wild-type mice are increased in the 5′ UTR. These findings provided the first hint that FTO activity might be directed towards m6Am. The basis for the reduced peak mass ratio in the 3′ UTR is unclear. Because FTO is a demethylating enzyme, loss of FTO should increase nucleotide methylation. Thus, the reduced methylation of m6A residues in the 3′ UTR is likely to be an indirect effect of FTO deficiency. CDS, coding sequence; TSS, transcription start site. b, Representative HPLC chromatogram of synthetic standards that were used to determine retention times of adenosine (A), 2′-O-methyladenosin (Am), N6-methyladenosine (m6A), or N6,2′-O-dimethyladenosine (m6Am). mAU, milli absorbance units. c-f, Reaction curves for FTO with the different substrates that were used to calculate reaction velocity for Michaelis-Menten analysis. FTO concentrations that allowed initial velocity conditions were used for individual oligonucleotides (20 nM FTO for m7Gpppm6Am (c) and m7Gpppm6A (d); 200 nM FTO for m7Gpppm6A (e) and internal m6A (f) in a GGACU context; n = 3 biological replicates; mean ± s.e.m.). g, Michaelis-Menten plots of FTO for either m6Am or m6A. Michaelis-Menten curves of FTO reacting with m7Gpppm6Am (blue), m7Gpppm6A (brown), m7GpppACm6A (orange) or m6A in a GGACU context (green). Owing to the increased reaction speed of FTO with m6Am and m6A adjacent to the m7G compared to more distal m6A, the enzyme concentration was tenfold lower when we assessed reaction rates for m6Am (20 nM FTO for the m7Gpppm6Am and m7Gpppm6A oligonucleotide; 200 nM FTO for the m7Gpppm6A and for internal m6A in a GGACU context). Figure 1d shows a plot in which the data are normalized to enzyme concentration. However, here the plot shows data that were not normalized to enzyme concentration (n = 3 biological replicates; mean ± s.e.m.).

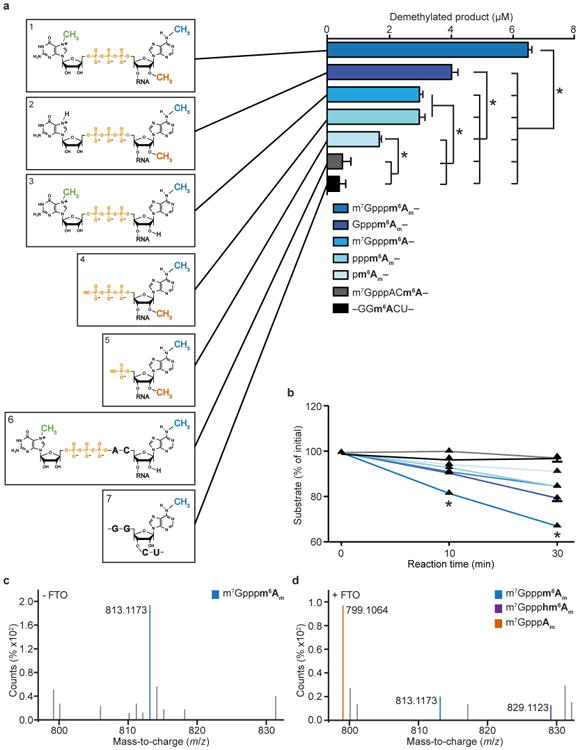

Extended Data Figure 2. FTO-mediated demethylation of m6Am depends on integral parts of the mRNA 5′ cap and accurate mass measurement of the oxidative demethylation of the extended m7Gpppm6Am-cap by FTO.

a, Structure-activity relationship of FTO and its substrate. ALKBH5 preferentially demethylates m6A in its physiological sequence context but FTO does not require a sequence context to demethylate m6A (refs 3,60). This lack of a sequence preference suggests that m6A is not a preferred substrate for FTO. We therefore asked whether FTO preferentially demethylates m6Am in its natural sequence context as the first nucleotide adjacent to the m7G cap. To determine the specific structural elements of the extended cap that are required for efficient N6-demethylation of m6Am, we synthesized oligonucleotides with different 5′ ends indicated in boxes 1-7. Shown is the amount of product (Am for substrates 1, 2, 4, 5; A for substrates 3, 6, 7) generated by FTO (200 nM) after 30 min when incubated with different oligonucleotides (20 μM) containing m6Am or N6-methyladenosine (m6A). The highest FTO demethylation activity on was on the full cap1m structure m7Gpppm6Am (1). Removal of the N7-methyl from the guanosine (2) reduced FTO activity by 30% (2), whereas removal of either the 2′-O-methyl from the adenosine (3) or the m7G (4) resulted in a 50% activity loss. FTO activity was further reduced by removal of m7Gpp (5). The lowest FTO demethylation activity was observed when using m6A as a substrate, either at the +3 position after the cap (6) or internally in a GGACU context (7). Thus, an adjacent m7G cap does not activate m6A as a substrate for FTO. These results indicate that FTO activity is dependent on the presence of a full cap structure, including the 2′-O-methyl at the +1 position, whereas m6A is a poor substrate for FTO (one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test; *P< 0.001; n = 3 biological replicates; mean ± s.e.m.). b, Structure-activity relationship of FTO and its substrate. Shown is the amount of substrate converted by FTO in a time-dependent manner at the same reaction conditions as in a (two-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test; *P < 0.001 versus all other structures; n = 3 biological replicates; mean ± s.e.m.). c, d, FTO demethylates m7Gpppm6Am at the N6-position through oxidization of m7Gpppm6Am to an N6-hydroxymethyl intermediate (m7Gppphm6Am). The final reaction product is m7GpppAm. Liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry analysis of m7Gpppm6Am RNA either left untreated (c; —FTO) or after incubation with 3 μM FTO for 10 min (d; +FTO). Shown are representative mass-to-charge (m/z) ratios of precursor ions. In the absence of FTO, the dinucleotide shows a measured m/z ratio of 813.1173, 0.98 p.p.m. mass accuracy from the exact m/z of 813.1165 (formula C23H33N10O17P3). Incubation with FTO generates m7Gppphm6Am, shown as a measured m/z of 829.1123, 1.01 p.p.m. mass accuracy from the exact m7Gppphm6Am m/z of 829.1114 (formula C23H33N10O18P3). The demethylated final product m7GpppAm and residual non-demethylated m7Gpppm6Am were also detected in the FTO reaction mixture, with m7GpppAm showing a measured m/z of 799.1064, 6.9 p.p.m. mass accuracy from the exact m/z of 799.1009 (formula C22H31N10O17P3).

Extended Data Figure 3. 6Am is the preferred substrate for FTO in vivo.

a, Modifications of the extended mRNA cap. The first nucleotide adjacent to the m7G and the 5′-to-5′-triphosphate (ppp) linker is subjected to 2′-O-methylation (orange) on the ribose, forming cap1. Cap1 can be further 2′-O-methylated at the second nucleotide to form cap2 (not depicted here). If cap1 contains a 2′-O-methyladenosine (Am), it can be further converted to cap1m by N6-methylation (blue), which results in N6,2′-O-dimethyladenosine (m6Am). b, Relative abundance of m6A in mRNA treated with recombinant FTO. Internal m6A residues that follow G in mRNA can be labelled and quantified in a 2D TLC method61. The relative abundance of m6A versus (A + C + U) in 400 ng mRNA that was either left untreated (—FTO) or incubated for 1 h with 1 μM bacterially expressed recombinant human FTO (+FTO) was determined by 2D TLC. We did not observe any decrease of m6A in FTO-treated mRNA, indicating that FTO does not efficiently demethylate m6A in its physiological context in mRNA in vitro (representative images shown; n = 3 biological replicates; mean ± s.e.m.). c, FTO with a nuclear export signal is localized in the cytoplasm. Immunofluorescence staining of DDDDK/Flag tag in HEK293T cells transfected with Flag-tagged wild type FTO (Flag-FTO) or Flag-tagged FTO with an N-terminal nuclear export signal (NES-FTO). FTO is primarily nuclear while NES-FTO is readily detected in the cytosol. DAPI was used to stain nuclei (representative images shown). d, Western blot analyses were performed to verify successful knockdown, overexpression and knockout. Top left, cell extracts from HEK293T cells with FTO knockdown were blotted with anti-FTO antibody. Knockdown efficiency was approximately 75%. The cell extracts were from the same samples used for RNA-seq analysis in Fig. 3d. GAPDH was used as loading control. Top right, western blot analysis of HEK293T expressing Flag vector (Ctrl) or FTO with an N-terminal nuclear export signal (NES-FTO) that were used for RNA-seq half-life analysis in Fig. 3c. An antibody directed against β-actin was used as a loading control. The lower band represents endogenous FTO, whereas the upper band represents exogenous NES-FTO, which showed approximately tenfold overexpression. Top left, cell extracts from ALKBH5-knockdown HEK293T cells with were blotted with anti-ALKBH5 antibody. Knockdown efficiency was approximately 90%. The cell extracts were from the same samples used for RNA-seq analysis in Extended Data Fig. 7e. β-Actin was used as loading control. Top right, western blot analysis of three different HEK293T clonal lines with CRISPR-mediated knockout of DCP2 that were used for RNA-seq analysis. GAPDH was used as a loading control. e, FTO expression decreases m6Am in HEK293T cells. The relative abundance of modified adenosines in mRNA caps of HEK293T expressing Flag vector (Ctrl) or Flag-tagged FTO with an N-terminal nuclear export signal (Flag-NES-FTO) was determined by 2D TLC. When determining the ratio of m6Am to Am, we observed a significant decrease of m6Am in Flag-NES-FTO-overexpressing cells, indicating that FTO can convert cytoplasmic m6Am to Am in vivo. Notably, the ratios of m6Am:Am that we observed upon FTO expression (both with and without the NES) may under-represent the true effect of FTO: Am mRNAs are generally less stable than m6Am mRNAs owing to their degradation in cells via DCP2-mediated pathways (see Figs 3 and 4). Thus the Am mRNAs generated by FTO-mediated demethylation of m6Am may not efficiently accumulate in cells compared to m6Am mRNAs (representative images shown; n = 3 biological replicates; mean ± s.e.m.; unpaired Student's t-test, *P ≤ 0.01). f, FTO expression does not affect m6A in HEK293T cells. The relative abundance of m6A versus (A + C + U) in mRNA of HEK293T expressing empty vector (Ctrl) or FTO with an N-terminal nuclear export signal (NES-FTO) was determined by 2D TLC. We did not observe any decrease of m6A upon NES-FTO expression, indicating that FTO does not readily influence levels of m6A in HEK293T cells at this level of expression. Notably, under these same expression conditions, m6Am is readily demethylated (see Extended Data Fig. 3e) (representative images shown; n = 3 biological replicates; mean ± s.e.m.). Control experiments measuring m6A and m6Am levels following ALKBH5-knockdown and expression in HEK293T cells are shown in Extended Data Fig. 4. g, FTO deficiency increases m6Am in vivo. Relative abundance of modified adenosines in mRNA caps of embryonic day (E) 14 wild-type (WT) littermate controls and Fto knockout (Fto–/–) mouse embryos (representative images shown; n = 3 biological replicates; mean ± s.e.m.; unpaired Student's t-test, **P≤ 0.01). h, FTO knockdown does not affect m6A in HEK293T cells. The relative abundance of m6A versus (A + C + U) in mRNA of HEK293T cells transfected with scrambled siRNA (siCtrl) or siRNA directed against FTO (siFTO) was determined by 2D TLC. We did not observe any increase of m6A upon FTO knockdown, indicating that FTO does not readily influence levels of m6A in vivo (representative images shown; n = 3 biological replicates; mean ± s.e.m.). i, Relative abundance of m6A in Fto-knockout mouse embryos. The relative abundance of m6A versus (A + C + U) in mRNA of embryonic day 14 wild-type littermate controls and Fto-knockout (Fto−/−) mouse embryos was determined by 2D TLC. We did not observe any increase of m6A in Fto-deficient embryos, indicating that FTO does not influence the levels of m6A in this embryonic stage (representative images shown; n = 3 biological replicates; mean ± s.e.m.).

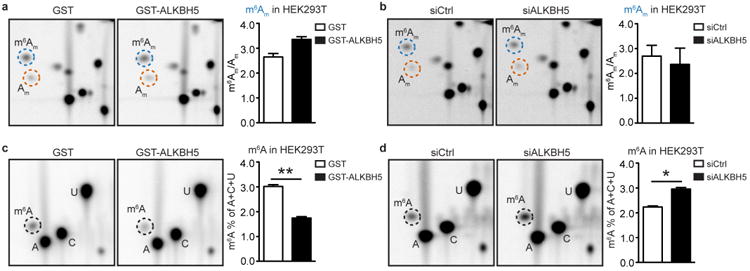

Extended Data Figure 4. ALKBH5 demethylates m6A but not m6Am in mRNA in HEK293T cells.