Abstract

Objectives

Obesity prevalence among people living with HIV (HIV+) is rising. HIV and obesity are pro-inflammatory states, but their combined effect on inflammation (measured by interleukin 6, IL-6), altered coagulation (D-dimer), and monocyte activation (soluble CD14, sCD14) is unknown. We hypothesized inflammation increases when obesity and HIV infection co-occur.

Methods

The VACS survey cohort is a prospective, observational, longitudinal study of predominantly male, HIV+ veterans and veterans uninfected with HIV; a subset provided blood samples. Inclusion criteria for this analysis were: body mass index (BMI) ≥ 18.5 kg/m2 and with biomarker measurements. Dependent variables were IL-6, sCD14, and D-dimer quartiles. Obesity/HIV status was the primary predictor. Unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models were constructed.

Results

Data were analyzed for 1477 HIV+ and 823 uninfected participants. Unadjusted median IL-6 levels were significantly higher and sCD14 levels were significantly lower in obese/HIV+ when compared with non-obese/uninfected people (p-value <0.01 for both). In adjusted analyses, the odds ratio (OR) for increased IL-6 in obese/HIV+ was 1.76 (95%CI: 1.18, 2.47) when compared with non-obese/uninfected, and obesity/HIV+ remained associated with lower odds of elevated sCD14. We did not detect a synergistic association of co-occurring HIV and obesity on IL-6 or sCD14 elevation. D-dimer levels did not differ significantly between BMI/HIV status groups.

Conclusion

HIV-obesity comorbidity is associated with elevated IL-6, decreases in sCD14 and no significant difference in D-dimer. These findings are clinically significant as previous studies show these biomarkers are associated with mortality. Future studies should assess whether other biomarkers show similar trends and potential mechanisms for the unanticipated sCD14 and D-dimer findings.

Introduction

Obesity is a leading health threat in the United States,1,2,3 and is more common in minorities and those with lower socioeconomic status (SES).4-9 These same individuals are also most severely impacted by the HIV epidemic.10,11 Since potent antiretroviral therapy (ART) became widely available, weight loss previously associated with untreated HIV infection has been supplanted by weight gain. Consequently, obesity is increasingly common in people living with HIV infection.12-17

Both obesity and HIV infection independently increase risk for cardiovascular disease.18-22 A hypothesized mechanism for the increased cardiovascular risk, common to both, is immune system alteration.23-29 While obesity has well-established associations with traditional risk factors for CVD including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes, both HIV and obesity are associated with immune system alterations that may independently impact risk.23-28 While both HIV and obesity are associated with altered immunity, their combined effect on inflammation, altered coagulation, and monocyte activation is unclear.

We hypothesized that the combination of obesity and HIV infection (obesity/HIV) is associated with increased inflammation when compared to either condition alone or the absence of both conditions. In a subset of participants from the Veterans Aging Cohort Study (VACS) survey cohort, we examined the relationship between obesity/HIV and biomarkers of inflammation (interleukin-6), altered coagulation (D-dimer) and monocyte activation (soluble CD14, sCD14). These three biomarkers were chosen because they represent different inflammatory pathways, and are altered in the context of HIV and obesity.23,30-33

Methods

Study design and setting

This is a cross sectional analysis of data from the VACS. The VACS survey cohort is a prospectively enrolled observational longitudinal study of veterans living with HIV (HIV+) and veterans who are uninfected with HIV (uninfected) matched (1:1) on age, sex, race-ethnicity, and geographic location.34 In 2005-2007, a subset of this cohort (1,525 HIV+ and 843 uninfected) participants consented to provide blood samples as previously described.27 Those with body mass index (BMI) ≥ 18.5 kg/m2 (i.e., not underweight) and with available measurements of IL-6, sCD14, or D-dimer were eligible for inclusion in the present analyses.

Dependent and independent variables

IL-6, sCD14 and D-dimer were the dependent variables. They were analyzed as continuous variables for descriptive analyses and categorized into quartiles for regression analyses, as the relationship between BMI and all three biomarkers was nonlinear (Appendix Figure). IL-6 and D-dimer were log transformed to better approximate the normal distribution. Specimens used to measure these biomarkers were collected using serum separator and EDTA blood collection tubes and shipped to a central repository at the Massachusetts Veterans Epidemiology Research and Information Center in Boston, Massachusetts. Measurements of these biomarkers are further described in prior work.27

To construct the independent variable, we classified obesity (BMI)≥30 kg/m2) by HIV status to create four mutually exclusive categories. We chose obesity as a threshold because overweight status (BMI≥25kg/m2 and <30kg/m2) may not be associated with adverse outcomes in the general population or among people living with HIV.3,15,18 Underweight (BMI <18.5kg/m2) were excluded due to small number in the cohort (n=48). People with BMI 18.5-30 kg/m2 who were HIV uninfected (non-obese/HIV) were defined as the referent group.

Covariates

Covariates were assessed closest to the time of blood specimen collection for IL-6, sCD14 and D-dimer measurement. Sociodemographic data included age, gender, and race-ethnicity. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) was defined using previously validated diagnostic or procedural codes for myocardial infarction, unstable angina, congestive heart failure, coronary revascularization, or ischemic stroke.35,36 Hypertension was defined as receipt of anti-hypertensive therapy prescription or blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg based on the average of the last three outpatient measurements as previously described.21,37,38 Diabetes was defined using a validated algorithm that includes glucose measurements, use of insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents, and/or ICD-9 codes.39 Smoking was self-reported using a standardized survey.40 Total cholesterol measurements were dichotomized at 200 mg/dL, low density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol at 160 mg/dL, high density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol at 40 mg/dL and triglycerides at 200 mg/dL.21,41 HMG CoA reductase inhibitor (statin) prescriptions were assessed using data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse.

Using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) and alcohol abuse/dependence ICD-9 codes we categorized alcohol use as: 1) no current drinking, 2) low risk current drinking (AUDIT-C <4) 3) at-risk or heavy drinking (AUDIT-C≥4), and 4) alcohol abuse or dependence diagnosis.42 History of cocaine use was defined by self report. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection status was based on a positive HCV antibody test or at least one inpatient and/or two outpatient ICD-9 codes.43 Advanced liver fibrosis was estimated as a FIB-4 score >3.25 using participant age, platelet count, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels.44,45 Anemia was defined as hemoglobin <12g/dL. Chronic kidney disease (CKD stage 3-5) was defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of <60 mL/min/1.73m2.46 Any history of cancer up to time of biomarker assessment was determined using VA Central Cancer Registry data.47 For HIV infected participants, we also assessed HIV-1 RNA level, dichotomized at 500 copies/mL as in prior VACS studies,21,38 CD4+ T-cell (CD4) count dichotomized at 500 cells/mm3, and antiretroviral therapy regimen: nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI) plus protease inhibitors (PI), NRTI plus non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), other, no antiretroviral therapy (ART).21

Statistical analysis

We compared continuous variables (Kruskall-Wallis rank test) and categorical variables (chi-squared test) by BMI categories overall and stratified by HIV status. We assessed correlations of obesity/HIV status with IL-6, sCD14, and D-dimer. We then constructed logistic regression models to estimate the association between obesity/HIV comorbidity and elevated (highest quartile vs lower three quartiles) IL-6, sCD14, or D-dimer. Logistic regression analyses were first adjusted for age and race-ethnicity and subsequently adjusted for diabetes, CVD, hepatitis C virus infection, FIB-4>3.25, eGFR<60, smoking, hypertension, HDL- and, LDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, statin prescription, cocaine use, and alcohol use. Adjustment covariates were selected based on prior work suggesting an association with BMI, and IL-6, sCD14 or D-dimer, but adjustment for gender was not possible because of the small number of obese HIV+ women in the cohort.27 Odds ratios for the different categories of the BMI/HIV status variable were compared using Wald tests with a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. We conducted three sensitivity analyses: 1) models subcategorizing HIV+ by HIV-1 RNA <500 copies/ml versus ≥500 copies/mL to determine the impact that uncontrolled HIV viremia may have on the association between the inflammatory parameters and BMI status; 2) models excluding those with hepatitis C infection due to its known association with increases in inflammatory biomarkers,48 and 3) models excluding those with prevalent diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer, all comorbidities likely to confound the relationship between obesity/HIV comorbidity and IL-6, sCD14 or D-dimer.

Results

Study population

Of participants included in this cohort, 1477 HIV+ and 823 uninfected participants met inclusion criteria for this analysis. Of the 68 who were excluded most (70%) were for being underweight BMI (<18.5kg/m2). Of 2,300 participants overall, 95% were men; 68% were African American, 37% normal weight, 36% overweight, and 27% obese (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the cohort overall and by four obesity/HIV status categories: non-obese HIV-uninfected (uninfected); non-obese, living with HIV (HIV+); obese/uninfected; and obese/HIV+. Data are presented as n and then percent of column in parentheses unless otherwise indicated.

| Non-obese | Obese | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uninfected | HIV+ | Uninfected | HIV+ | ||

|

| |||||

| N (% of row) | 438 (19) | 1232 (54) | 385 (17) | 245 (11) | 2300 |

|

| |||||

| Median age (mean, SD) years | 53 (54, 9) | 52 (52, 8) | 53 (54, 10) | 51 (51, 8) | 53 (53, 9) |

|

| |||||

| Men | 399 (91) | 1202 (98) | 345 (90) | 236 (96) | 2182 (95) |

|

| |||||

| Race-Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 85 (19) | 244 (20) | 88 (23) | 37 (15) | 454 (20) |

| African American | 309 (71) | 836 (68) | 241 (63) | 179 (73) | 1565 (68) |

| Hispanic | 32 (7) | 104 (8) | 34 (9) | 19 (8) | 189 (8) |

| Other | 12 (3) | 48 (4) | 22 (6) | 10 (4) | 92 (4) |

|

| |||||

| LDL ≥160 mg/dL | 28 (6) | 60 (5) | 29 (8) | 13 (5) | 130 (6) |

|

| |||||

| HDL <40 mg/dL | 111 (25) | 511 (41) | 165 (43) | 128 (52) | 915 (40) |

|

| |||||

| Triglycerides ≥200 mg/dL | 47 (11) | 327 (27) | 88 (23) | 78 (32) | 540 (23) |

|

| |||||

| Total cholesterol ≥200 mg/dL | 113 (26) | 319 (26) | 100 (26) | 80 (33) | 612 (27) |

|

| |||||

| Statin | 156 (36) | 356 (29) | 202 (52) | 99 (40) | 813 (35) |

|

| |||||

| FIB-4 Index >3.25 | 21 (5) | 109 (9) | 11 (3) | 16 (7) | 157 (7) |

|

| |||||

| eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 30 (7) | 91 (7) | 47 (12) | 21 (8) | 188 (8) |

|

| |||||

| Hemoglobin <12 g/dL | 32 (7) | 149 (12) | 26 (7) | 22 (9) | 229 (10) |

|

| |||||

| Alcohol use | |||||

| Not current | 149 (34) | 417 (34) | 158 (41) | 97 (40) | 821 (36) |

| Low risk | 65 (15) | 278 (23) | 78 (20) | 61 (25) | 482 (21) |

| At risk/heavy or binge | 52 (12) | 186 (15) | 64 (17) | 40 (16) | 342 (15) |

| Abuse/dependence | 172 (39) | 346 (28) | 85 (22) | 47 (19) | 650 (28) |

|

| |||||

| Smoking | |||||

| Non-smoker | 89 (20) | 278 (23) | 104 (27) | 82 (33) | 553 (24) |

| Current smoker | 239 (55) | 645 (52) | 148 (38) | 83 (34) | 1115 (48) |

| Past smoker | 109 (25) | 308 (25) | 132 (34) | 80 (33) | 629 (27) |

|

| |||||

| Cocaine | 194 (44) | 453 (37) | 115 (30) | 81 (33) | 843 (37) |

|

| |||||

| Hepatitis C | 154 (35) | 590 (48) | 101 (26) | 98 (40) | 943 (41) |

|

| |||||

| HTN | 341 (78) | 864 (70) | 343 (89) | 202 (82) | 1750 (76) |

|

| |||||

| CVD | 99 (23) | 218 (18) | 129 (34) | 49 (20) | 495 (22) |

|

| |||||

| Diabetes | 95 (22) | 207 (17) | 152 (39) | 93 (38) | 547 (24) |

|

| |||||

| Non AIDS-Defining Cancer | 28 (6) | 58 (5) | 28 (7) | 12 (5) | 12 (5) |

|

| |||||

| AIDS-Defining Cancer | 2 (0.5) | 19 (2) | 0 (0) | 5 (2) | 26 (1) |

|

| |||||

| HIV-1 RNA (HIV+ only) | |||||

| VL≥500 copies/mL | 0 | 413 (34) | 0 | 83 (34) | 496 (22) |

|

| |||||

| CD4+ Cell Count (HIV+ only) | |||||

| CD4<500 cells/mm3 | 0 | 816 (66) | 0 | 139 (57) | 955 (42) |

Abbreviations: SD: standard deviation; LDL: low density lipoprotein; HDL: high density lipoprotein; statin: HMG-Co-A reductase inhibitor; FIB-4: Fibrosis-4 Index; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; HTN: blood pressure>=140/90 or receiving antihypertensive medications; CVD: cardiovascular disease.

All variables had complete data except the following: LDL-cholesterol was available for 2232 participants; HDL for 2240; triglycerides for 2266; total cholesterol for 2279; FIB-4 for 2267; albumin for 2290; eGFR for 2297; alcohol use for 2212; smoking for 2297; HIV-1 RNA for 1476; and CD4 count for 1476 participants.

Compared with non-obese participants, obese participants had higher prevalence of diabetes, statin prescription, and hypertension, and lower prevalence of alcohol use disorder and current smoking, regardless of HIV status (p<0.05, Table 1). Obese/HIV+ participants had the highest prevalence of HDL<40 mg/dL, and triglycerides ≥200 mg/dL (p<0.05, Table 1).

HIV+ participants were less likely to be obese (39%) compared with uninfected (61%, p<0.001), and were younger (mean 52 years, SD 8 years) than uninfected (54 years, SD 9 years, p<0.001). Of the HIV+ participants, 43% had HIV-1 RNA<500 copies/mL, and 23% had CD4+ cell counts >500 cells/mm3 at baseline.

Analysis of inflammatory biomarkers by obesity/HIV status

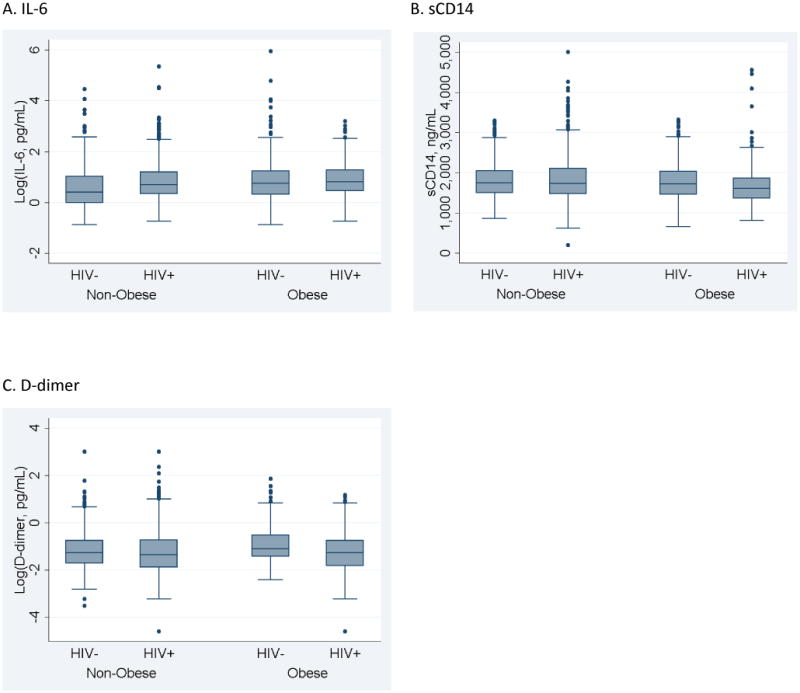

Median IL-6 levels were significantly higher in obese/HIV+ people (2.26 pg/mL; interquartile range [IQR] 1.55, 3.60) when compared with non-obese/uninfected (1.51 pg/mL; IQR 0.99, 2.79; p-value <0.01; Figure 1). In unadjusted logistic regression analyses, the odds of elevated IL-6 (i.e., being in the highest quartile) were significantly greater in all three comparator groups (non-obese/HIV+, obese/uninfected, and obese/HIV+) when compared with the referent (non-obese/HIV-; Table 2). These associations persisted after adjustment for potential confounders: compared with non-obese/HIV-, there were 31% increased odds of elevated IL-6 with HIV infection (non-obese), 64% increased odds with obesity (no HIV), and 79% increased odds with both obesity and HIV (Table 2). Overall, adjusted differences in IL-6 elevation between other pairs of categories (i.e., non-obese/HIV+ vs. obese/HIV+; or non-obese/HIV+ vs. obese/uninfected; or obese/uninfected vs. obese HIV+) were not statistically significant (omnibus p-value=0.11).

Table 2.

Association between obesity/HIV comorbidity and elevated biomarkers of inflammation, monocyte activation and altered coagulation. Differences significant at p<0.05 are in bold.

| Logistic regression model | Obesity/HIV status | Elevated biomarker (i.e. highest quartile) Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | sCD14 | D-dimer | |||||

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Unadjusted | Non-obese, uninfected | 1 (ref) | 0.03 | 1 (ref) | <0.01 | 1 (ref) | 0.03 |

| Non-obese, HIV+ | 1.32 (1.01-1.73) | 1.15 (0.90-1.49) | 1.04 (0.81-1.35) | ||||

| Obese, uninfected | 1.54 (1.11-2.13) | 0.92 (0.66-1.27) | 1.48 (1.09-2.03) | ||||

| Obese, HIV+ | 1.59 (1.10-2.29) | 0.58 (0.38-0.87) | 0.99 (0.68-1.44) | ||||

| Age, race-ethnicity adjusted | Non-obese, uninfected | 1 (ref) | 0.02 | 1 (ref) | <0.01 | 1 (ref) | 0.04 |

| Non-obese, HIV+ | 1.39 (1.06-1.82) | 1.19 (0.92-1.53) | 1.12 (0.86-1.45) | ||||

| Obese, uninfected | 1.55 (1.11-2.15) | 0.91 (0.65-1.26) | 1.54 (1.12-2.11) | ||||

| Obese, HIV+ | 1.71 (1.18-2.47) | 0.61 (0.40-0.91) | 1.07 (0.73-1.56) | ||||

| Fully adjusted | Non-obese, uninfected | 1 (ref) | 0.02 | 1 (ref) | <0.01 | 1 (ref) | 0.10 |

| Non-obese, HIV+ | 1.30 (0.97-1.74) | 0.99 (0.75-1.30) | 1.02 (0.76-1.35) | ||||

| Obese, uninfected | 1.63 (1.14-2.32) | 0.77 (0.54-1.10) | 1.38 (0.99-1.94) | ||||

| Obese, HIV+ | 1.76 (1.18-2.63) | 0.44 (0.28-0.69) | 0.91 (0.60-1.36) | ||||

Fully adjusted models adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, LDL, HDL, statin use, FIB4, eGFR, alcohol use, smoking, cocaine use, HCV, HTN, CVD, diabetes

IL-6: n=2227; sCD14 N=2289; D-dimer N=2290

Soluble CD14 levels were significantly lower in obese/HIV+ compared with non-obese/uninfected (p<0.01, Figure 1). This finding was confirmed in unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models, where we observed significantly lower odds of elevated sCD14 in obese/HIV+ compared with non-obese/uninfected (both p<0.01; Table 2). Overall differences in sCD14 elevation between other pairs of categories were statistically significant (omnibus p-value<0.001). This was driven by differences in sCD14 elevation between non-obese/HIV+ vs. obese/HIV+ (Bonferroni p-value<0.001) and obese/uninfected vs. obese HIV+ (Bonferroni p-value=0.02). Median D-dimer did not differ significantly between BMI/HIV status groups (Figure 1). This result was reflected in fully adjusted models (Table 2).

Sensitivity analyses that further classified HIV status by HIV-1 RNA < or ≥500 copies/mL demonstrated results consistent with the primary analyses for IL-6 and sCD14 (Table 3). IL-6 and sCD14 levels in non-obese/HIV+ with HIV-1 RNA <500 copies/mL did not differ from those for non-obese /uninfected people, though sample sizes in the subgroups were small (see Table 3 footnote). Non-obese/HIV+ people with HIV-1 RNA ≥500 copies/mL had elevated D-dimer relative to non-obese/uninfected people (OR = 1.79; 95% CI=1.28-2.49; Table 3). The same was true for obese/HIV+ people with HIV-1 RNA ≥500 copies/mL though this association did not reach statistical significance (OR: 1.32; 95%CI=0.76-2.31); Table 3). Two additional sensitivity analyses excluding those with HCV and those with prevalent diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer yielded results that were directionally consistent with the primary analyses (Appendix).

Table 3.

Association between obesity/HIV (sub-classified by HIV-1 RNA status) comorbidity and elevated biomarkers of inflammation, monocyte activation and altered coagulation. Differences significant at p<0.05 are in bold.

| Logistic regression model | Obesity/HIV status | HIV-1 RNA (copies/mL) | Elevated biomarker (i.e highest quartile) Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | sCD14 | D-dimer | ||||||

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |||

| Unadjusted | Non-obese, uninfected | -- | 1 (ref) | <0.01 | 1 (ref) | <0.01 | 1 (ref) | <0.01 |

| Obese, uninfected | -- | 1.54 (1.11-2.13) | 0.92 (0.66-1.27) | 1.48 (1.09-2.03) | ||||

| Non-obese, HIV+ | <500 | 1.06 (0.79-1.42) | 1.07 (0.81-1.40) | 0.74 (0.56-0.99) | ||||

| ≥500 | 1.92 (1.40-2.63) | 1.33 (0.98-1.81) | 1.80 (1.33-2.43) | |||||

| Obese, HIV+ | <500 | 1.67 (1.10-2.53) | 0.63 (0.40-1.01) | 0.75 (0.47-1.19) | ||||

| ≥500 | 1.46 (0.85-2.51) | 0.48 (0.24-0.94) | 1.56 (0.93-2.61) | |||||

| Age, race-ethnicity adjusted | Non-obese, uninfected | -- | 1 (ref) | <0.01 | 1 (ref) | <0.01 | 1 (ref) | <0.01 |

| Obese, uninfected | -- | 1.55 (1.11-2.15) | 0.91 (0.65-1.26) | 1.54 (1.12-2.12) | ||||

| Non-obese, HIV+ | <500 | 1.09 (0.81-1.46) | 1.07 (0.82-1.41) | 0.77 (0.58-1.03) | ||||

| ≥500 | 2.16 (1.57-2.98) | 1.45 (1.07-1.98) | 2.06 (1.51-2.81) | |||||

| Obese, HIV+ | <500 | 1.78 (1.17-2.70) | 0.65 (0.41-1.05) | 0.81 (0.51-1.29) | ||||

| ≥500 | 1.65 (0.96-2.86) | 0.53 (0.27-1.04) | 1.75 (1.04-2.96) | |||||

| Fully adjusted | Non-obese, uninfected | -- | 1 (ref) | <0.01 | 1 (ref) | <0.01 | 1 (ref) | <0.01 |

| Obese, uninfected | -- | 1.60 (1.13-2.28) | 0.77 (0.54-1.09) | 1.36 (0.97-1.90) | ||||

| Non-obese, HIV+ | <500 | 1.05 (0.76-1.44) | 0.90 (0.67-1.21) | 0.73 (0.53-1.00) | ||||

| ≥500 | 1.88 (1.33-2.66) | 1.17 (0.84-1.64) | 1.79 (1.28-2.49) | |||||

| Obese, HIV+ | <500 | 1.89 (1.21-2.96) | 0.48 (0.29-0.80) | 0.72 (0.44-1.17) | ||||

| ≥500 | 1.56 (0.86-2.82) | 0.38 (0.19-0.78) | 1.32 (0.76-2.31) | |||||

Fully adjusted models adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, LDL, HDL, statin use, FIB4, eGFR, alcohol use, smoking, cocaine use, HCV, HTN, CVD, diabetes

Sample size within obesity/HIV/HIV-1 RNA (above or below 500 copies/mL) strata: Non-obese HIV uninfected (438), obese HIV uninfected (385), non-obese HIV+ <500 (819), non-obese HIV+ ≥500 (413), obese HIV+ <500 (161), obese HIV+ ≥500 (83)

Discussion

In this cross sectional examination of inflammatory biomarkers in HIV+ and uninfected participants, we found that obesity/HIV comorbidity is associated with elevated IL-6 and decreased sCD14, particularly in the setting of uncontrolled viral replication. Obese/HIV+ participants, when compared with non-obese/uninfected participants, had statistically significant elevations in IL-6, a biomarker of inflammation, and decreases in sCD14, a biomarker of monocyte activation. We did not detect a significant association of obesity/HIV status and D-dimer, a biomarker of altered coagulation.

To our knowledge, this is the largest study comparing IL-6, sCD14, and D-dimer by BMI and HIV status in a cohort including HIV+ and uninfected participants. A recent investigation compared 35 HIV+ with 30 matched, uninfected, obese participants, and found that IL-6 did not significantly differ according to HIV status. They also found sCD14 was increased in obese/HIV+ when compared to obese/uninfected, the opposite of the association seen in our study. The characteristics of this smaller cohort differed from those in our cohort in terms of age and gender distributions, and D-dimer levels were not measured.30

Multiple prior studies investigated the association between these biomarkers and obesity in HIV+ participants without comparison to an uninfected population. IL-6 did not have a consistent association with adipose tissue mass in HIV+ participants in one investigation,49 while in a other reports IL-6 was associated with increases in BMI, particularly for HIV+ men.31,50 sCD14 was found to increase with weight gain in virologically suppressed, predominately normal weight HIV+ participants between 0 and 48 weeks after antiretroviral initiation across nine countries.29 In the Strategies for Management of Antiretroviral Therapy (SMART) Study, investigators did not detect an association between obesity and D-dimer in HIV+,32 similar to our findings. Likewise, D-dimer was not associated with obesity in a cohort of uninfected participants.33 These studies, which did not compare HIV+ with uninfected participants in the same cohort, have limited ability to comment on the differential impact of obesity on these biomarkers in those living with HIV versus without HIV infection.

Interleukin 6

We found that obesity and HIV infection contributed to elevations in IL-6, an inflammatory cytokine strongly associated with morbidity and mortality in HIV+ cohorts.51-55 Median IL-6 levels were significantly higher in obese/HIV+, when compared with non-obese/uninfected, but there was no statistical difference between IL-6 levels in obese/HIV+ and those with either condition alone (non-obese/HIV+ or obese/uninfected, Figure). Thus, we did not find evidence for a synergistic effect of HIV/obesity comorbidity on IL-6 elevations.

Obesity without HIV and HIV viremia without obesity were each associated with IL-6 elevation, and obese/uninfected individuals were more likely to have elevated IL-6 levels than non-obese uninfected in all three logistic regression models. Interestingly, non-obese/HIV+ individuals with HIV-1 RNA <500 copies/mL had similar IL-6 levels to non-obese/uninfected (Table 3), implying that controlled HIV disease alone, without obesity, is not associated with significant elevations in IL-6 in this cohort. While obese/HIV+ participants with HIV-1 RNA ≥500 copies/mL had a higher prevalence of elevated IL-6 than non-obese/uninfected, this association did not reach statistical significance. The anticipated elevation of IL-6 derived from uncontrolled viral replication may have been present, but the small sample size of only 83 obese/HIV+ participants with HIV-1 RNA ≥500 copies/mL may have limited our ability to detect an association.

The source of IL-6 in obesity/HIV comorbidity may be an important consideration in defining the implications of and future hypotheses generated from our findings. IL-6 can be derived from activated macrophages in tissues, such as blood vessels, or it can be produced by adipocytes, where levels increase in association with adipocyte diameter.56-58 In obesity, IL-6 is predominately adipose-tissue derived, which may differ from chronic HIV infection, where it is likely induced by immune cell activation. Whether 1) adipocyte derived IL-6 has more local effects on tissues while IL-6 production from immune cell activation has more systemic effects and 2) whether the distribution of local versus systemic effects has impact on morbidity or mortality are important questions for future research.

Soluble CD14

We observed lower sCD14 levels in obese/HIV+ participants compared to non-obese/HIV+ participants, which is in line with results from some prior studies.45,47,58 Other studies have focused on the association between HIV status and sCD14 elevation in normal weight participants, and found increase sCD14 in HIV+ participants.59-61 A possible explanation for these discordant findings is that hepatic steatosis in obesity leads to lower sCD14 levels because of decreases in hepatocyte-derived sCD14.62 When HIV and obesity co-occur, sCD14 levels may be influenced by multiple factors including monocyte activation within adipose tissue, other co-occurring inflammatory conditions (e.g. diabetes, hepatitis C), and the presence of hepatic steatosis.63,64 The etiology of the unanticipated findings that sCD14 decreases in the setting of obesity/HIV comorbidity deserve further exploration, and other biomarkers of monocyte activation, such as soluble CD163 or macrophage inflammatory protein-1α, should be examined to determine whether they follow a similar trend.45 Other illustrative liines of research would repeat the present study accounting for differences in hepatic steatosis between groups.

D-Dimer

In fully adjusted models, obesity/HIV comorbidity was not associated with D-dimer except when HIV status was stratified by viral suppression (i.e., HIV-1 RNA less or greater than 500 copies/mL). Unsuppressed HIV viremia was associated with increased D-dimer though this was only statistically significant among non-obese people. The positive association between obesity and D-dimer among HIV uninfected people did not reach statistical significance. Overall we did not detect a synergistic effect of obesity/HIV comorbidity on D-dimer elevations.

There are limitations to this analysis. This is an observational, cross-sectional study, preventing us from examining trends over time in inflammatory parameters. It would be useful to examine trends in relation to the duration of virologic suppression or in the setting of weight change or aging. BMI is used as a measure of adiposity rather than a measurement of waist circumference or visceral adipose tissue, known to be more strongly correlated with cardiovascular outcomes. The population is overwhelmingly male and older, limiting generalizability to women and younger HIV+ people. The individual biomarkers measured may not capture the full complexity of the immune processes they represent, though all three are well-studied in both HIV+ and uninfected cohorts. Data on diet and physical activity, which can confound associations of obesity with inflammatory biomarkers, were not included in this analysis. As with any observational study, there is the possibility of unmeasured confounding from drug use, multiple comorbidities, or other factors.

In summary, obesity/HIV comorbidity is associated with elevated IL-6 and decreased sCD14. However, we did not detect a synergistic effect of obesity/HIV comorbidity on IL-6, sCD14 or D-dimer. This may suggest overlap in the mechanisms by which obesity and HIV contribute to alterations in these biomarkers and the immune processes they represent. The clinical implications of these findings deserve further exploration, as the impact of obesity on morbidity and mortality in HIV+ individuals remains unclear. Recent studies from the North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design suggest that weight gain and obesity are associated with improved CD4+ cell recovery and decreased incidence of non-communicable diseases.65,66 However, data from the Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs cohort study show that short term weight gain after ART initiation, particularly in those with a normal baseline BMI, was associated with increased risk of incident CVD and diabetes.67

Despite uncertainty surrounding the impact of rising BMI in this population, the difference in median IL-6 levels between obese/HIV+ and non-obese/uninfected participants our analysis is similar to or greater than differences associated with increased mortality risk in other prospective studies.53,54 As obesity prevalence among people living with HIV rises,17 further investigation into the long-term implications of this weight gain is needed. Future prospective studies should assess whether intentional weight loss or similar interventions affect inflammatory processes similarly in HIV infected and uninfected people.68-70

Supplementary Material

Figure.

Boxplots depicting median, interquartile ranges, and outliers for each biomarker by obesity/HIV status. A statistically significant difference exists between the non-obese/HIV- and obese/HIV+ groups for log IL-6 (p<0.01) and sCD14 (p<0.01). No significant difference was seen between obesity/HIV status groups for log D-dimer.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health K23AI081538 [BST]

American Heart Association, National Center Mentored Clinical and Population Research Award 14CRP20150023 [BST]

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and National Heart Lung and Blood Institute at the National Institutes of Health R01HC095136-04 and 5R01HC095126-04 [MSF]

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism U10 AA 13566 [Veterans Aging Cohort Study]

Footnotes

Meetings at which the data were presented: Presented at: 2016 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Poster Presentation. Boston, MA Feb 22-25, 2016. Taylor BS, So-Armah K, Tate JP, Marconi VC, Bedimo R, Butt AA, Gibert C, Goetz M, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Freiberg MS. “HIV & Obesity Synergistically Increase Interleukin 6 but not Soluble CD14 or D-dimer.”

Contributor Information

Barbara S. Taylor, Medical Service/Infectious Diseases, South Texas Veterans Health Care System, San Antonio, TX; Department of Medicine, UT Health San Antonio, San Antonio, TX

Kaku So-Armah, Department of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA

Janet P. Tate, Section of General Internal Medicine, VA Connecticut Healthcare System, West Haven, CT; Department of Internal Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT

Vincent C. Marconi, Medical Service, VA Medical Center, Atlanta, GA; Medical Service, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA

John Koethe, Departments of Medicine and Biostatistics, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN

Roger Bedimo, Infectious Disease Section, Department of Medicine, VA North Texas Health Care System, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX

Adeel Ajwad Butt, Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion, VA Pittsburg Healthcare System, Pittsburgh, PA; Hamad Healthcare Quality Institute, Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha, Qatar; Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, Doha, Qatar and New York, NY

Cynthia L. Gibert, Medical Service/Infectious Diseases, VA Medical Center, Washington, D.C.; Department of Medicine, George Washington University Medical Center, Washington, D.C.

Matthew Goetz, Department of Medicine, VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Los Angeles, CA; David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA

Maria C. Rodriguez-Barradas, Infectious Diseases Section, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, Houston, TX; Infectious Diseases Section, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Julie A. Womack, VA Connecticut Healthcare System, West Haven, CT.

Mariana Gerschenson, Cell and Molecular Biology Department, John A. Burns School of Medicine, University of Hawaii- Manoa, Honolulu, HI

Vincent Lo Re, III, Philadelphia VA Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA; Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, VA

David Rimland, Medical Service, VA Medical Center, Atlanta, GA; Medical Service, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA

Michael T. Yin, Division of Infectious Diseases, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY

David Leaf, Infectious Diseases Section, VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Los Angeles, CA; Department of Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA

Russell P. Tracy, Departments of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine and Biochemistry, College of Medicine, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT

Amy Justice, Section of General Internal Medicine, VA Connecticut Healthcare System, West Haven, CT; Department of Internal Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT

Matthew S. Freiberg, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN; Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center, VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Nashville, TN

References

- 1.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flegal KM, Graubard BI, Williamson DF, Gail MH. Cause-specific excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity. JAMA. 2007;298(17):2028–2037. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.17.2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flegal KM, Kit BK, Orpana H, Graubard BI. Association of all-cause mortality with overweight and obesity using standard body mass index categories: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2013;309(1):71–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.113905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of Obesity in the United States, 2009–2010. National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief No 82, ed Vol January: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Beydoun MA. The obesity epidemic in the United States--gender, age, socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and geographic characteristics: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29:6–28. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Vital signs: state-specific obesity prevalence among adults --- United States, 2009. MMWR - Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 2010;59(30):951–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robert SA, Reither EN. A multilevel analysis of race, community disadvantage, and body mass index among adults in the US. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(12):2421–2434. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Q, Wang Y. Trends in the association between obesity and socioeconomic status in U.S. adults: 1971 to 2000. Obes Res. 2004;12(10):1622–1632. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Q, Wang Y. Socioeconomic inequality of obesity in the United States: do gender, age, and ethnicity matter? Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(6):1171–1180. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, et al. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006-2009. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(8):e17502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300(5):520–529. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tate T, Willig AL, Willig JH, et al. HIV infection and obesity: where did all the wasting go? Antivir Ther. 2012;17(7) doi: 10.3851/IMP2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crum-Cianflone N, Roediger MP, Eberly L, et al. Increasing rates of obesity among HIV-infected persons during the HIV epidemic. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(4):e10106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amorosa V, Synnestvedt M, Gross R, et al. A tale of 2 epidemics: the intersection between obesity and HIV infection in Philadelphia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39(5):557–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koethe JR, Jenkins CA, Shepherd BE, Stinnette SE, Sterling TR. An optimal body mass index range associated with improved immune reconstitution among HIV-infected adults initiating antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(9):952–960. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor BS, Liang Y, Garduno LS, et al. High risk of obesity and weight gain for HIV-infected uninsured minorities. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65(2):e33–40. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koethe JR, Jenkins CA, Lau B, et al. Rising Obesity Prevalence and Weight Gain Among Adults Starting Antiretroviral Therapy in the United States and Canada. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2016;32(1):50–58. doi: 10.1089/aid.2015.0147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGee DL, Diverse Populations Collaboration Body mass index and mortality: a meta-analysis based on person-level data from twenty-six observational studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2005;15(2):87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnlov J, Ingelsson E, Sundstrom J, Lind L. Impact of body mass index and the metabolic syndrome on the risk of cardiovascular disease and death in middle-aged men. Circulation. 2010;121(2):230–236. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.887521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lavie CJ, McAuley PA, Church TS, Milani RV, Blair SN. Obesity and cardiovascular diseases: implications regarding fitness, fatness, and severity in the obesity paradox. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(14):1345–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freiberg MS, Chang CC, Kuller LH, et al. HIV infection and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):614–622. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paisible AL, Chang CC, So-Armah KA, et al. HIV infection, cardiovascular disease risk factor profile, and risk for acute myocardial infarction. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68(2):209–216. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Yannakoulia M, Chrysohoou C, Stefanadis C. The implication of obesity and central fat on markers of chronic inflammation: The ATTICA study. Atherosclerosis. 2005;183(2):308–315. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444(7121):860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature05485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amirayan-Chevillard N, Tissot-Dupont H, Capo C, et al. Impact of highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) on cytokine production and monocyte subsets in HIV-infected patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;120(1):107–112. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01201.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neuhaus J, Jacobs DR, Jr, Baker JV, et al. Markers of inflammation, coagulation, and renal function are elevated in adults with HIV infection. J Infect Dis. 2010;201(12):1788–1795. doi: 10.1086/652749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Armah KA, McGinnis K, Baker J, et al. HIV status, burden of comorbid disease, and biomarkers of inflammation, altered coagulation, and monocyte activation. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(1):126–136. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Triant VA, Meigs JB, Grinspoon SK. Association of C-reactive protein and HIV infection with acute myocardial infarction. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51(3):268–273. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a9992c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mave V, Erlandson KM, Gupte N, et al. Inflammation and Change in Body Weight With Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation in a Multinational Cohort of HIV-Infected Adults. J Infect Dis. 2016;214(1):65–72. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koethe JR, Grome H, Jenkins CA, Kalams SA, Sterling TR. The metabolic and cardiovascular consequences of obesity in persons with HIV on long-term antiretroviral therapy. Aids. 2016;30(1):83–91. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borges AH, O'Connor JL, Phillips AN, et al. Factors Associated With Plasma IL-6 Levels During HIV Infection. J Infect Dis. 2015;212(4):585–595. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borges AH, O'Connor JL, Phillips AN, et al. Factors associated with D-dimer levels in HIV-infected individuals. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e90978. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orenes-Pinero E, Pineda J, Roldan V, et al. Effects of Body Mass Index on the Lipid Profile and Biomarkers of Inflammation and a Fibrinolytic and Prothrombotic State. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2015;22(6):610–617. doi: 10.5551/jat.26161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Justice AC, Dombrowski E, Conigliaro J, et al. Veterans Aging Cohort Study (VACS): Overview and description. Med Care. 2006;44(8 Suppl 2):S13–24. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000223741.02074.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ives DG, Fitzpatrick AL, Bild DE, et al. Surveillance and ascertainment of cardiovascular events. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5(4):278–285. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)00093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Every NR, Fihn SD, Sales AE, Keane A, Ritchie JR. Quality Enhancement Research Initiative in ischemic heart disease: a quality initiative from the Department of Veterans Affairs. QUERI IHD Executive Committee. Med Care. 2000;38(6 Suppl 1):I49–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Armah KA, Chang CC, Baker JV, et al. Prehypertension, hypertension, and the risk of acute myocardial infarction in HIV-infected and -uninfected veterans. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(1):121–129. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Butt AA, McGinnis K, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, et al. HIV infection and the risk of diabetes mellitus. Aids. 2009;23(10):1227–1234. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832bd7af. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McGinnis KA, Brandt CA, Skanderson M, et al. Validating smoking data from the Veteran's Affairs Health Factors dataset, an electronic data source. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2011;13(12):1233–1239. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Expert Panel on Detection E, Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in A. Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285(19):2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Archives of internal medicine. 1998;158(16):1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Butt AA, Xiaoqiang W, Budoff M, Leaf D, Kuller LH, Justice AC. Hepatitis C virus infection and the risk of coronary disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(2):225–232. doi: 10.1086/599371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N, et al. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2006;43(6):1317–1325. doi: 10.1002/hep.21178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Loko MA, Castera L, Dabis F, et al. Validation and comparison of simple noninvasive indexes for predicting liver fibrosis in HIV-HCV-coinfected patients: ANRS CO3 Aquitaine cohort. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2008;103(8):1973–1980. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(2 Suppl 1):S1–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park LS, Tate JP, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, et al. Cancer Incidence in HIV-Infected Versus Uninfected Veterans: Comparison of Cancer Registry and ICD-9 Code Diagnoses. J AIDS Clin Res. 2014;5(7):1000318. doi: 10.4172/2155-6113.1000318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Armah KA, Quinn EK, Cheng DM, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C, and inflammatory biomarkers in individuals with alcohol problems: a cross-sectional study. BMC infectious diseases. 2013;13:399. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koethe JR, Dee K, Bian A, et al. Circulating interleukin-6, soluble CD14, and other inflammation biomarker levels differ between obese and nonobese HIV-infected adults on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013;29(7):1019–1025. doi: 10.1089/aid.2013.0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Conley LJ, Bush TJ, Rupert AW, et al. Obesity is associated with greater inflammation and monocyte activation among HIV-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy. Aids. 2015;29(16):2201–2207. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kuller LH, Tracy R, Belloso W, et al. Inflammatory and coagulation biomarkers and mortality in patients with HIV infection. PLoS medicine. 2008;5(10):e203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Duprez DA, Neuhaus J, Kuller LH, et al. Inflammation, coagulation and cardiovascular disease in HIV-infected individuals. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e44454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nordell AD, McKenna M, Borges AH, et al. Severity of cardiovascular disease outcomes among patients with HIV is related to markers of inflammation and coagulation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(3):e000844. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.000844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McDonald B, Moyo S, Gabaitiri L, et al. Persistently elevated serum interleukin-6 predicts mortality among adults receiving combination antiretroviral therapy in Botswana: results from a clinical trial. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013;29(7):993–999. doi: 10.1089/aid.2012.0309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Deeks SG, Tracy R, Douek DC. Systemic effects of inflammation on health during chronic HIV infection. Immunity. 2013;39(4):633–645. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tanaka T, Kishimoto T. The biology and medical implications of interleukin-6. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2(4):288–294. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Skurk T, Alberti-Huber C, Herder C, Hauner H. Relationship between adipocyte size and adipokine expression and secretion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(3):1023–1033. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jernas M, Palming J, Sjoholm K, et al. Separation of human adipocytes by size: hypertrophic fat cells display distinct gene expression. FASEB J. 2006;20(9):1540–1542. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5678fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cassol E, Malfeld S, Mahasha P, et al. Persistent microbial translocation and immune activation in HIV-1-infected South Africans receiving combination antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2010;202(5):723–733. doi: 10.1086/655229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lien E, Aukrust P, Sundan A, Muller F, Froland SS, Espevik T. Elevated levels of serum-soluble CD14 in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection: correlation to disease progression and clinical events. Blood. 1998;92(6):2084–2092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wallet MA, Rodriguez CA, Yin L, et al. Microbial translocation induces persistent macrophage activation unrelated to HIV-1 levels or T-cell activation following therapy. Aids. 2010;24(9):1281–1290. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328339e228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.du Plessis J, Korf H, van Pelt J, et al. Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines but Not Endotoxin-Related Parameters Associate with Disease Severity in Patients with NAFLD. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0166048. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Quon BS, Ngan DA, Wilcox PG, Man SF, Sin DD. Plasma sCD14 as a biomarker to predict pulmonary exacerbations in cystic fibrosis. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e89341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bas S, Gauthier BR, Spenato U, Stingelin S, Gabay C. CD14 is an acute-phase protein. J Immunol. 2004;172(7):4470–4479. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Koethe JR, Jenkins CA, Lau B, et al. Body mass index and early CD4 T-cell recovery among adults initiating antiretroviral therapy in North America, 1998-2010. HIV Med. 2015;16(9):572–577. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koethe JR, Jenkins CA, Lau B, et al. Higher Time-Updated Body Mass Index: Association With Improved CD4+ Cell Recovery on HIV Treatment. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(2):197–204. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Achhra AC, Mocroft A, Reiss P, et al. Short-term weight gain after antiretroviral therapy initiation and subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: the D:A:D study. HIV Med. 2016;17(4):255–268. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fitch K, Abbara S, Lee H, et al. Effects of lifestyle modification and metformin on atherosclerotic indices among HIV-infected patients with the metabolic syndrome. Aids. 2012;26(5):587–597. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834f33cc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lindegaard B, Hansen T, Hvid T, et al. The effect of strength and endurance training on insulin sensitivity and fat distribution in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with lipodystrophy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(10):3860–3869. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Troseid M, Ditlevsen S, Hvid T, et al. Reduced trunk fat and triglycerides after strength training are associated with reduced LPS levels in HIV-infected individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66(2):e52–54. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.