Abstract

As unique biopolymers, proteins can be employed for therapeutic delivery. They bear important features such as bioavailability, biocompatibility, and biodegradability with low toxicity serving as a platform for delivery of various small molecule therapeutics, gene therapies, protein biologics and cells. Depending on size and characteristic of the therapeutic, a variety of natural and engineered proteins or peptides have been developed. This, coupled to recent advances in synthetic and chemical biology, has led to the creation of tailor-made protein materials for delivery. This review highlights strategies employing proteins to facilitate the delivery of therapeutic matter, addressing the challenges for small molecule, gene, protein and cell transport.

Keywords: drug delivery, gene therapy, cell therapy, structural proteins, protein engineering, biomaterials

1. Introduction

Research efforts toward the controlled administration of pharmaceuticals have evolved over the last half century. First realized in 1952 [1] Dexedrine® formulated in Spansule® (Smith, Kline & Fench Laboratories, now merged into GlaxoSmithKline) exhibited a gradual release [2]. This historical milestone aroused the significance of sustained release systems followed by the development of controllable drug delivery. In addition, the delocalized effects from free drug compounds that were systemically administrated by either enteral (digestive tract, i.e. orally) or parenteral (non-digestive tract, i.e. subcutaneously, intramuscularly or intravenously) routes greatly hindered therapeutic efficacy [3, 4].

Despite advancements in conventional polymeric and liposomal delivery agents including drug protection, site targeting, and toxicity reduction, these approaches are still plagued by issues of instability of drug storage and release [5]. These ever-present challenges motivate the development protein-based drug delivery vehicles. Compared to synthetic polymers, natural proteins possess inherent advantages – better bioavailability, biocompatibility, biodegradability with low toxicity – and have thus been the focus as a platform for delivery of various small molecule therapeutics, gene therapies, and protein biologics [6]. Protein-based delivery vehicles may provide a more efficacious approach to delivering therapeutics by virtue of the ability to refine the compositional sequence and structure of proteins [7–12].

In general, an optimal protein-based carrier would possess several qualities [13] among: 1) stability to adapt environmental factors such as temperature, pH, ionic strength, and the presence of proteases; 2) appropriate scale for administration routes; 3) reasonable complexity for modification; 4) interior and/or exterior to associate with therapeutics; 5) proper interaction to bind therapeutics; 6) capacity to release therapeutics in controlled manner; 7) specificity to target treated cells or tissues; 8) protection from therapeutic degradation; and 9) efficiency of cellular and/or nuclear internalization. Therefore, certain proteins may not be considered suitable as delivery systems. Enzymes, for example, are commonly structured with high level of complexity in order to generate a catalytic site specifically for the substrate, intermediate, product, byproduct, and any applicable cofactor; thus, they are limited in how they can be modified. Due to their sophisticated structure and function, enzymes are often delicate to produce and to preserve, restricting their capability to serve as a therapeutic delivery agent.

To expand the availability of protein-based carriers that meet the aforementioned criteria, recombinant proteins that are genetically designed, engineered and biosynthesized in a host organism are being developed for designated therapeutic payloads. With well-established databases and innovations in synthetic and chemical biology, custom-made protein engineered delivery systems are emerging. In addition, further modifications such as conjugation with chemicals, e.g. PEGylation and/or hybridization with inorganic materials [14] are positioning engineered proteins as more versatile and responsive by improving solubility, specificity, and traceability.

Herein, we review current strategies employing proteins to facilitate the delivery of therapeutic matter for small molecules, nucleic acids, protein therapeutics, and cells (Figure 1). As demonstrated, these classes of therapeutics span a variety of clinical applications, and are restricted in their efficacy and/or application due to challenges in delivery.

Figure 1.

Illustration of protein-based drug delivery systems and available therapeutic payloads: small molecule drugs, nucleic acids, proteins/peptides and cells.

2. Small Molecule Therapeutics

Small molecule chemistries have been employed to address most clinical indications [15]. Advancements in computational chemistry and high-throughput formulation have produced more efficacious compounds [16]. Despite these efforts however, several characteristic flaws, including low solubility and high toxicity, compromise the efficacy of many pharmaceutical compounds [4]. They are also relatively unstable and easily degraded in physiologic conditions. This is due in part to clearance facilitated by the reticuloendothelial system, renal clearance, and chemical/enzymatic deactivation [3, 4, 17–20]. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics continue to be a technical hurdle for many of these basic formulations (Figure 2). The physicochemical properties of small molecules may not yield ideal pharmacokinetic profiles. In addition, issues of solubility, non-specific degradation or binding, and unintended toxicity are barriers confronting the efficacy of a small molecule therapeutic. However, these shortcomings of physicochemical properties may be decoupled by way of a delivery vehicle of significantly different character, e.g. biomacromolecules.

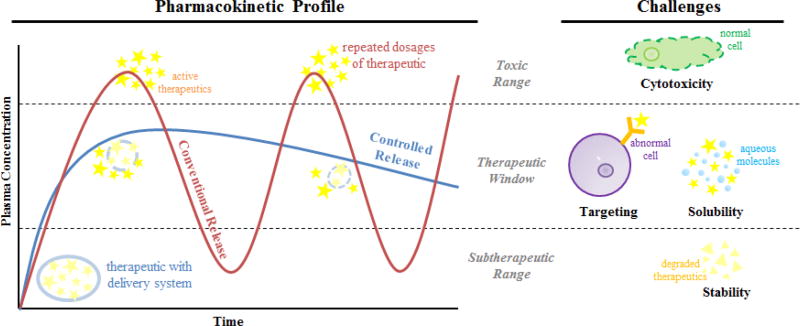

Figure 2.

Challenges associated with the delivery of small molecule therapeutics. The pharmacokinetic profile of a drug compound is reflective of its time-dependent distribution upon administration. Various delivery methods may tailor the distribution profile accordingly, modified significantly from conventional release profiles, by which challenges pertaining to unintended toxicity (top boundary) or sub-therapeutic efficacy (bottom boundary) may be overcome. In addition, challenges such as cytotoxicity, targeting, solubility and stability may also affect the pharmacokinetic profile.

This overarching challenge of multi-faceted clearance may be overcome with proteins, specific to certain indications. In oncology, for example, chemotherapeutic drugs have been drawing extensive attention to the field of drug delivery because the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect presented by the support of a delivery system lessens the damage and toxicity toward normal cells [21]. The EPR effect first reported in 1986 by Matsumura and Maeda is a unique phenomenon of tumors largely producing vascular permeability factors owing to its defective blood vessels to ensure tumor tissues are supplied with sufficient nutrients and oxygen for rapid growth [22]. This essentially facilitates transport dynamics of macromolecules and a concept of passive targeting [23] governed by the factors associated with tumor microvasculature and microenvironment such as size, shape and surface charge [24]. Therefore, in order to remain a therapeutic in the circulation for minimum 6 hours to accumulate in the neoplastic tissue [25], macromolecules often require an apparent molecular weight of >40~50 kDa [21, 25]. In addition, pore size cutoffs for tumor vasculature have been reported from studies to manifest within 400 to 600 nm diameters [26], with maximal absorption into tissues occurring with supramolecular assemblies with diameters of 100 nm [27]. Nevertheless, despite this strategy able to localize treatments to tumor site, the uptake by cancer cells may not be enhanced [23].

This concept of loading therapeutic payload onto macromolecules (e.g. proteins) that are more likely to distribute within tumorous tissue has earned the focus of protein engineers to optimize physicochemical properties of certain proteins to accommodate such action. Ensuring that the size of both the protein delivery vehicle and the protein-drug complex is critical to enabling leverage of the EPR effect [28]. Moreover, secondary concerns include the toxicity of the protein vehicle itself, toxicity of its byproducts stemming from enzymatic degradation, and the clearance kinetics of the protein-drug complex in competition with the kinetics of accumulation due to the EPR effect. Notable examples of small molecules benefiting from this modality are doxorubicin [27, 29–36], paclitaxel [37–41], methotrexate [42–45], and curcumin [46, 47]. In addition, the strategy of delivering prodrug forms of such molecules has been invoked in tandem with the application of protein-based delivery vehicles – a testament to the high degree of engineering demanded of the challenge of drug delivery [35, 48–50].

Even with the promises of nanomedicine highlighting EPR mediated effects, the results have not yet been successfully translated from small animal models to a clinical setting, leading to the discussions of assessing environmental differences between human and murine tumors [51]. Due to heterogeneity, human tumors may contain: 1) less fenestrations in endothelium [52]; 2) hypoxic areas inducing resistance to radiotherapy and cytotoxic agents [53, 54]; 3) higher pericyte coverage related to worse prognosis and more fibrotic interstitium [55, 56]; 4) basement membrane consisting of type IV collagen limiting penetration through capillary walls, e.g. extracellular matrix (ECM) [56–58]; 5) higher density of ECM elevating interstitial fluid pressure [52, 59, 60]. These phenomena essentially cause inefficient extravasation of nanomedicines from vessels. While the EPR effect remains debatable, studies demonstrating positive efficacy are worth further investigation of the contributive factors that suggest a basis for the design of next generation therapeutic delivery agents.

Chief among the protein-based delivery vehicles applied to small molecule therapeutics are human serum albumin [19, 34–36, 44, 45, 48–50, 61–69], coiled-coil proteins [70–74], various structural proteins (e.g. gelatin [9], silk [75] and elastin [76]), caged proteins [77]) and antibodies [78]. While this list is not exhaustively complete, this review aims to highlight advancements in the design and engineering of proteins at-large (Table 1). Three themes presented are: 1) the adaptation of observable capabilities of natural proteins to encapsulate small molecules in the case of human serum albumin and coiled-coils; 2) the repurposing of natural proteins’ function for the encapsulation of small molecules, in the case of structural proteins and caged proteins; 3) the exploitation of superior targeting abilities of specific proteins, or antibodies, and linking small molecules to them.

Table 1.

Sizes and applications of protein-based delivery vehicles for small molecule payloads.

| Vehiclea | Moleculeb | Approx. Diameter (nm) |

Cell Line/Model for Evaluation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSA | ||||

| HSA | DOX | < 200 | MCF-7 human breast cancer cells | [34] |

| MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells | ||||

| INNO-206 | n.d. | M3366 breast cancer xenografts | [66] | |

| A2780 ovarian cancer xenografts | ||||

| H209 small cell lung cancer xenografts | ||||

| MIA PaCa-2 human pancreatic cancer cells | ||||

| AsPC-1 human pancreatic cancer cells | ||||

| PTX | 130 | Patients with HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer | [41, 79] | |

| Patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer | ||||

| MTX | 90~150 | T47D human breast cancer cells | [80] | |

| cisplatin derivatives | n.d. | A549 non-small cell lung cancer cells | [81] | |

| A2780 ovarian cancer cells | ||||

| A2780CP70 cisplatin-resistant ovarian cancer cells | ||||

| Cu(L)(PRD) | n.d. | HepG2 human liver cancer cells | [82] | |

| HL-7702 human liver cells | ||||

| HINPs | DOX | 50 | 4T1 murine breast cancer cells | [65] |

| TRAIL/Tf | DOX | 220 | HCT116 human colon cancer cells | [36] |

| MCF-7/ADR DOX-resistant breast cancer cells | ||||

| Capan-1 human pancreatic cancer cells | ||||

| Coiled-Coils | ||||

| RHCC | cisplatin | n.d. | RPMI 8226/S human myeloma cells | [70, 83, 84] |

| 8226/dox40 human myeloma cells (resistant subline) | ||||

| MDA 231 human breast cancer cells | ||||

| H69AR human small lung cancer cells | ||||

| FaDu human squamous cell carcinoma cells | ||||

| ACHN human renal cancer cells | ||||

| A2780 human ovarian cancer cells | ||||

| A2780cis human ovarian cancer cells (resistant subline) | ||||

| NCI-H69 human small lung cancer cells | ||||

| H-TERT-RPEI human epithelial cells immortalized with hTERT | ||||

| Balb/c mice | ||||

| SCID mice | ||||

| Human glioblastoma cells | ||||

| COMPcc | Vit. A | n.d. | n/a | [71, 73] |

| Vit. D3 | n.d. | n/a | [71, 73] | |

| ATRA | n.d. | n/a | [73] | |

| fatty acids | n.d. | n/a | [72] | |

| CCM | n.d. | n/a | [71] | |

| Q | CCM | 1600 | n/a | [85] |

| Q+TFL | CCM | 42~1500 | n/a | [74] |

| Structural Proteins | ||||

| Gelatin | ||||

| Gelatin | DOX | 135 | SCC7 murine squamous cell carcinoma cells | [31] |

| PTX | 600~1000 | RT4 human bladder cancer cells | [37] | |

| MTX | 100~200 | n/a | [42] | |

| PEG-Gelatin | DOX | 250 | SCC7 murine squamous cell carcinoma cells | [31] |

| Gelatin-co-PLA-DPPE | DOX | 132~161 via double emulsion | A549 human lung cancer cells | [86] |

| 196~282 via nanoprecipitation | ||||

| AGIO@CaP | DOX | 120 | HeLa human cervical cancer cells | [33] |

| AuNPs@gelatin | DOX | ~ 65 | MCF-7 human breast cancer cells | [87] |

| ELP | ||||

| ELP | DOX | 20~40 | FaDu human squamous cell carcinoma cells | [30, 88] |

| 4T1-luciferase murine mammary cancer cells | ||||

| LL/2-Luc-M38 murine lung cancer cells | ||||

| FKBP-ELP | rapamycin | < 100 | Human breast cancel model | [89, 90] |

| Mouse model of Sjögren's syndrome | ||||

| EnC | CCM | 26~28 | n/a | [91] |

| CEn | CCM | 26~30 | n/a | [91] |

| E1C-GNP | CCM | 20~30 | MCF-7 human breast cancer cells | [92] |

| Silk | ||||

| SELPs | DOX | 250~300 | HeLa human cervical cancer cells | [93] |

| Silk/HER2-binding domain | DOX | 400 | SKOV3 human ovarian cancer cells | [94] |

| SKBR3 human breast cancer cells | ||||

| Thixotropic silk | DOX | ~ 20 | MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells | [95] |

| Female BALB/c nude mice | ||||

| Casein | ||||

| r-CM | DHA | 50~60 with calcium/phosphate | n/a | [96] |

| β-CN | CCM | n.d. | n/a | [46] |

| PTX | 30~40 | N-87 human gastric cancer cells | [97] | |

| PLGA-CN | PTX/EGCG | ~ 200 | PBMSs | [98] |

| RAW 264. Macrophages | ||||

| Adult Sprague-Dawley rats | ||||

| CDDP | cisplatin | ~ 250 | SH-SY5Y human derived neuroblastoma cells | [99] |

| Male ICR mice/H22 tumor cells | ||||

| Cage Proteins | ||||

| HspG41C | Mal-DOX | 12 | n/a | [100] |

| CPMV | DOX | 32 | HeLa human cervical cancer cells | [29] |

| Antibodies | ||||

| anti-CanAg | DM1 | n.d. | Patients with CanAg-expressing solid malignancies | [101–103] |

| COLO 205 human colon adenocarcinoma | ||||

| HL-60 human acute promyelocytic leukemia cells | ||||

| Namalwa human Burkitt’s lymphoma cells | ||||

| HT-29 human colon adenocarcinoma cells | ||||

| A375 human malignant melanoma cells | ||||

| HepG2 human hepatocellular carcinoma cells | ||||

| SNU-16 gastric carcinoma cells | ||||

| Female CB-17 mice/SCID | ||||

| Female CD-1 mice | ||||

| anti-CD56 | DM1 | n.d. | Patients with small cell lung carcinoma and other CD56+ solid tumors | [104] |

| anti-PSMA | DM1 | n.d. | Patients with prostate cancer | [105] |

| anti-CD44v6 | DM1 | n.d. | Patients with advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | [106] |

| anti-HER2 | DM1 | n.d. | Breast cancer | Kadcyla® |

| duocarmycin | n.d. | Human tumr cell lines (SK-BR-3, UACC-893, NCI-N87, SK-OV-3, MDA-MB-175-VII, ZR-75-1, NCI-H520, and SW-620) | [107] | |

| Breast cancer patient-derived xenograft models | ||||

| anti-CD33 | calicheamicin | n.d. | Acute myeloid leukemia | Mylotarg® |

| pyrrologenzodiaze pine | n.d. | Human acute myeloid leukemia cells | [108] | |

| Patients with acute myeloid leukemia | ||||

| anti-CD22 | calicheamicin | n.d. | Patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia | [109] |

| anti-CD19 | DM4 | n.d. | Patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia | [110] |

| anti-CD20 | yttrium-90 | n.d. | Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | [111] |

| anti-CEA | iodine-131 | Colorectal cancer | ||

| anti-Muc1 | Gastric cancer | |||

| anti-tenascin | Ovary cancer | |||

| Glioma cancer | ||||

Abbreviations: HSA: human serum albumin, HINP: HSA-coated iron oxide nanoparticle, TRAIL/Tf: tumor necrosis factor related apoptosis inducing ligand and transferrin, RHCC: right-handed coiled coil, COMPcc: coiled coil domain of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein, TFL: trifluoroleucine, PEG: polyethylene glycol, PLA: polylactic acid, DPPE: 1,2-(dipalmitoylsn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine), ELP: elastin-like peptide, FKBP: FK506 binding protein, GNP: gold nanoparticle, SELP: silk-elastin-like peptide, Her: human epidermal growth factor receptor, r-CM: re-formed casein micelle, β-CN: beta casein, PLGA-CN: poly-L-lactide-co-glycolic acid-casein, Hsp: heat shock protein, CPMV: cowpea mosaic virus, hTERT: telomerase reverse transcriptase in human, SCID: severe combined immunodeficiency.

Abbreviations: DOX: doxorubicin, INNO-206: (6-maleimidocaproyl)hydrazone, PTX: paclitaxel, MTX: methotrexate, Vit: vitamin, CCM: curcumin, DHA: docosahexaenoic acid, Mal-DOX: (6-maleimidocaproyl) hydrazine, EGCG: epigallocatechin gallate, DM1: mertansine/emtansine, DM4: ravtansine/soravtansine.

2.1. Human Serum Albumin

Human serum albumin (HSA) has been well studied and reviewed for its characteristics and potential applications in the clinical setting [61, 62]. HSA is perhaps the most widely known soluble protein to have an implication and application in the field of drug delivery. Most abundant in human blood plasma (approximately 35~50 g/L) [50], HSA is highly bioavailable, biocompatible, non-toxic and exhibits low immunogenicity [112]. HSA possesses a high content of cysteine with 17 disulfide bridges [113], which provides stability enabling it to endure pH ranging from 4 to 9, withstand heat up to 60 °C for 10 hours [50], and survive modifications involving harsh conditions. The disulfide bridges crosslink three homologous domains I, II, and III within HSA [50, 114]. Each of these domains has a pair of subdomains, A and B, where IIA and IIIA are recognized as two major binding sites known as Sudlow’s sites [115] to accommodate a variety of hydrophobic molecules [116]. While the Sudlow classification does not satisfy HSA binding for all ligands, a recent study has identified the subdomain IB as a third binding region primarily for the bilirubin photoisomer, hemin, a sulphonamide derivative, and fusidic acid [117]. By virtue of these physicochemical properties, HSA has been first studied as an endogenous binding protein and for its marked effects on the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of small molecule therapeutics [19, 63, 64], and has obtained a more prominent spotlight as a drug delivery vehicle.

The anticancer agent, doxorubicin (DOX), has been employed as a candidate for drug payload given its broad cytotoxic effects upon systemic administration [118, 119]. It has been reported toxic to several organs such as heart, brain, liver, and kidney in healthy conditions, as well as cause severe multidirectional side effects [118]. In order to lower its toxicity under treatment, DOX has been marketed as a therapeutic agent by several enterprises mainly with liposomal systems [20]. In addition to liposomes, HSA has been extensively employed as a drug carrier for DOX. The interaction of HSA binding to DOX has been elucidated by docking studies that indicate the stabilization is contributed by several hydrophilic and hydrophobic residues involving a hydrogen bonding network among Leu115, His146, Arg186, and Lys190 [120]. DOX-loaded HSA nanoparticles (HSA + DOX NPs) fabricated via ethanol precipitation with the size of 183.86 ± 8.19 nm has displayed a promising treatment for metastasized and chemoresistant breast cancer [34]. Anoikis-resistant breast cancer cells, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231, able to migrate to other tissues for reattachment and further growth, have been investigated for treatment with HSA + DOX NPs [34]. Bypassing the efflux system pumped by ATP-binding cassettes, the HSA + DOX NPs exhibits higher cytotoxicity to MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 than free DOX molecules by 20% and 10%, respectively [34].

Chen et al. previously modified Fe3O4 iron oxide nanoparticles with dopamine to provide partial hydrophilicity, thus better enabling binding of DOX and HSA along the surface boundary of the nanoparticles (D-HINPs, DOX-loaded HSA-coated iron oxide nanoparticles), forming complexes with hydrodynamic sizes of 50.8 ± 5.2 nm. The performance of D-HINPs in a therapeutic study on a 4T1 murine breast cancer xenograft model was comparable to Doxil® (Johnson & Johnson, NJ, USA), a liposome-formulated DOX, and was significantly improved than free DOX [65]. Furthermore, the D-HINPs provided multiple advantages such as sustained release, DOX translocation through the cell membrane, and tumor targeting.

HSA has been modified with tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) and transferrin (Tf) on the surface prior to binding to DOX, generating ~ 220 nm nanoparticles [36]. TRAIL has been considered as an anti-cancer treatment [121] for its activation of apoptosis pathways via caspase-dependent signal transductions [122], whereas transferrin is a ligand for tumor targeting with the up-regulation of its receptors highly expressed in cancer cells [123, 124]. The TRAIL/Tf/DOX modified HSA demonstrated effective cytotoxic and apoptotic effects on HCT 116, MCF-7, and CAPAN-1 cell lines, suggesting its potential of promiscuous treatments to different tumors in various organs [36].

In addition to DOX, HSA is able to bind its prodrugs (6-maleimidocaproyl)hydrazone (INNO-206, DOXO-EMCH), which exhibits better efficacy than DOX in numerous cancer models [35, 48, 49, 66, 67]. In a recent study of human pancreatic cancer cells, MIA PaCa-2, treated with the combinations of DOX and HSA-DOXO-EMCH, a 1:5 ratio of DOX to HSA-DOXO-EMCH has shown the highest synergistic profile in the cytotoxicity assay when DOX is introduced 6 hours prior to the addition of HSA-DOXO-EMCH [49].

Many of these studies have been encouraged by Abraxane® (Celgene, NJ, USA), an HSA-formulated paclitaxel approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that is effective as cancer therapy and proven to improve pharmacokinetics than free paclitaxel [40, 41]. Methotrexate, a folic acid derivative that is commonly used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis as well as a lesser employed chemotherapeutic, has been conjugated with HSA (MTX-HSA); they have exhibited promising efficacy in various animals [50, 68] and undergone phase I/II clinical studies for further investigation [44, 45, 69].

The examples of utilizing the non-covalent chemistry of HSA, its protein-protein and protein-small molecule interactions in vivo, continue to grow and incrementally evolve with the exploration of the physicochemical characteristics of each new invention. As HSA is known to be responsible for maintaining colloid osmotic pressure via binding ligands [125], such function could prevent therapeutics from releasing. In addition, while high content of HSA naturally exists in blood, released payload could be competitively re-bound to local HSA in advance of traveling to specific tissues. These biological mechanisms are expected to be emphasized and investigated to improve the design and formulation of HSA-based delivery systems. By increasing capacity, affinity, and specificity between the drugs and a certain subdomain of HSA that is generally occupied with natural ligands like fatty acid, for instance, the efficiency of transporting the drugs could be more successful. As an example, a series of derivatives from the platinum-based drug, cisplatin, has been developed with various lengths of aliphatic tails to mimic the amphiphilic structure of fatty acids, which could facilitate non-covalent interactions with HSA [81]. These analogs of cis, cis, trans-[Pt(NH3)2Cl2(O2CCH2CH2CH2COOH)(OCONHR)], where R is a linear alkyl group modulates the cytotoxicity of cisplatin by three orders of magnitude and exhibit a 9 ~ 70 fold higher anticancer activity in vitro than cisplatin alone in lung and ovarian cancer cell lines [81]. When R = C16 – the largest alkyl group in the study – the compound shows and increased half-life of 6.8 hours compared to about 20 minutes for cisplatin when formulated with HSA [81]. In another study, the IIA subdomain of HSA has been modified to bind a copper compound derived from 2-amino-5-chlorophenol 2-hydroxybenzaldehyde Schiff base containing the leaving group pyridine, dubbed Cu(L)(PRD) [82]. Complexed with HSA via replacing the histidine at position 242 in the IIA cavity with the leaving group, Cu(L)(PRD) performs better targeting and anticancer activity to the HepG2 human liver cancer cell line with 1.4-fold improvement. Overall, the primary hurdles addressed by HSA as a delivery vehicle are the needs for improved efficacy and targeting [44, 45, 69, 123, 124].

2.2. Coiled-coils

Coiled-coil proteins are an additional class of soluble proteins that have gained significant promise as a drug delivery vehicle [12, 126]; they encompass higher order oligomers – tetramers or pentamers – of alpha-helical proteins. Several coiled-coil proteins, particularly the right-handed coiled-coil (RHCC) and the cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMPcc), define an enlarged hydrophobic core over more common coiled-coils [126]. The prominent hypothesis among developers of this protein as a delivery agent is that the enlarged hydrophobic core can non-covalently encapsulate therapeutic payloads composed of small molecules.

RHCC (GSIINETADDIVYRLTVIIDDRYESLKNLITLRADRLEMIINDNVSTILASI) comprises, in part, the tetrabrachion complex that constitutes the surface layer of the cell envelope of the archaebacterium Staphylothermus marinus and is composed of a four-stranded α-helical domain oriented parallel in a right-handed fashion [70, 83]. The tetrameric form of the protein, which has a molecular weight of 22.8 kDa, defines a hydrophobic pore that is 7.2 nm in length and 2.5 nm in diameter [83]. This pore is capable of non-covalently binding small molecules such as water and heavy metals, but also the platinum-containing chemotherapeutic cis-diammine-dichloroplatinum (II) (cisplatin) as has been demonstrated by Eriksson et al [70]. This group has shown that the IC50 of cisplatin, when delivered via an RHCC complex, is significantly reduced for particular cell lines – i.e. 8226/d0x40, RPMI 8226/S, and MDA 231 cells [70]. In a most recent study of RHCC associating with platinum (IV) based cisplatin, the chemotherapeutic efficacy and selectivity toward human glioblastoma cells was improved by lowering the concentration of platinum (IV) prodrug 20-fold than platinum (IV) alone [84].

Alternatively, the initial structural and functional examinations of the coiled-coil domain of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein by Guo et al. [73] prompted the development of recombinant COMPcc (MRGSH6GSGDLAPQMLRELQETNAALQDVRELLRQQVKEITFLKNTVMESDASGKLN) by Montclare et al. [71] toward a platform drug delivery vehicle, wherein a cysteine has been mutated to a serine to create a dynamically oligomeric species incapable of forming permanent cross-links. A non-collagenous extracellular matrix glycoprotein, COMPcc possesses an oligomerization domain at N-terminus capable of self-assembling into a coiled-coil homopentamer [73]. The hydrophobic core of COMPcc has been reported to accommodate several hydrophobic molecules desirable for some physiological functions or therapies such as fatty acids [72], curcumin (CCM) [71], 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (Vit. D), all-trans retinol (Vit. A) and its derivative, all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) [73]. In more recent studies, COMPcc has been internally divided into 2 domains from Gln54 and swapped to create the construct Q [85]. The Gln54 residues among the pentamer form an intricate network of hydrogen bonds and separate the hydrophobic core of the wild-type into two cavities [126]; therefore, Q is anticipated to enlarge the accommodation for a ligand. In the presence of CCM, interestingly, Q assembles into micrometer [85].

In order to be better stabilized, the Leu residues of Q were replaced with the non-natural amino acid trifluoroleucine (TFL) during biosynthesis to generate Q+TFL [74], which potentially possesses dual function of drug delivery and tissue engineering. Upon the fluorination, the stability is further improved along with an enhancement of fiber assembly caused by highly helical structure, increasing its binding with CCM.

Coiled-coil proteins hold promise for small molecule encapsulation, particularly for applications that cannot rely on cleavage of the active drug compound from the carrier. Rather, coiled-coils are very much amenable to non-covalent applications for binding hydrophobic small molecules. The evaluation of binding constants and in vivo stability of the oligomeric species still remains as a foundational study for any particular application of this construct toward small molecule therapeutic delivery.

2.3. Structural Proteins

Bulk phase-forming proteins, many of which are endogenous structural proteins, have been investigated as drug delivery vehicles and are reported for the delivery of DOX such as gelatin [9], elastin-like peptide (ELP) [76], casein [32], silk [75], and caged proteins including small heat shock proteins and viral capsids [77]. A primary value is the extent to which the biocompatibility of protein-based drug delivery vehicles may be tuned and engineered [10, 13].

2.3a. Gelatin

Gelatin, which broadly refers to denatured forms of collagen, can be used as stabilizers in therapeutic formulations [127]. The efficacy of gelatin is highly dependent on processing methods to convert specific types of collagen into gelatin of consistent physicochemical properties (e.g. isoelectric points, gelling properties, polypeptide fragment size distributions) [128]. Its derivation from collagen allows it to be not only highly biocompatible and biodegradable but also readily available. As a denatured derivative obtained by acid and alkaline processing, gelatin causes lower antigenicity, which allows it to be considered as a superior GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) material by the FDA and widely applied for pharmaceutical and cosmetic purposes [9, 129]. Gelatin has been thoroughly reviewed for its therapeutic value in different treatments [9] including topical ophthalmic use [130], recurrent airway obstruction [131, 132], and acute monocytic leukemia [133]. Gelatin is able to associate with a variety of miscellaneous drugs against HIV [134], malaria [135], tubercula [136], fungi [137, 138], bacteria [137, 139], and general inflammation [140, 141].

DOX has been conjugated with gelatin (GD) or polyethylene glycol modified gelatin (PGD) [31]. Nanoparticles of 135 nm and 250 nm have been synthesized for the evaluation of anti-tumor and anti-metastatic effects [31]. Briefly, the synthesis involves coupling Type-B gelatin with acetaldehyde to block free amine groups and prevent inter- and intra-molecular cross-linking during the conjugation step with DOX. DOX in triethylamine (TEA) is then added to conjugate to carboxyl groups along the polypeptide backbone. Both GD and PGD decreases cytotoxicity relative to free DOX, while tumor growth is inhibited by 38% and 82%, respectively, compared to 62% for free DOX [31]. This study suggests a more promising DOX treatment of cancer with enhanced efficacy in the presence of its delivery vehicle based on gelatin.

In a recent study, an amphiphilic copolymer, gelatin-co-PLA-DPPE, constructed with gelatin, polylactide and 1,2-(dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine) (DPPE) has been developed and incorporated with DOX via emulsion or precipitation (Figure 3) [86]. These DOX-loaded nanoparticles exhibit comparable anti-tumor activity in vitro and in vivo, and can be controlled by the mass ratio of DPPE to the precursor for size and by pH for releasing [86].

Figure 3.

Proposed mechanisms of DOX encapsulation into gelatin-co-PLA-DPPE nanoparticles by an (a) emulsion and (b) evaporation method [86]. (a) Sonication of the copolymer dissolved in dichloromethane in the presence of DOX (aq) (1) is followed by another round of sonication to form water-organic-water emulsions (2), the organic phase of which is evaporated (3). (b) Copolymer in acetone is injected into an aqueous solution of DOX (1), which leads to nanoprecipitation upon solvent evaporation (2). Abbrev: PLA: poly(lactide); DPPE: 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine.

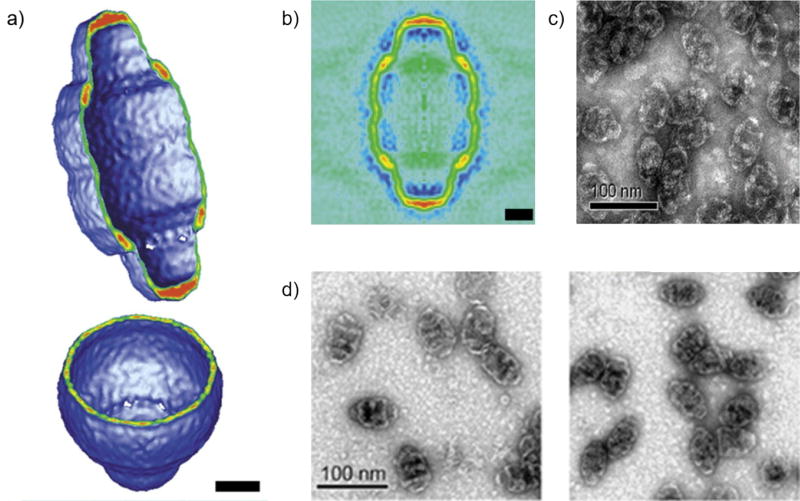

DOX has been decorated on the surface of gelatin-iron oxide nanoparticles (AGIO) in a calcium phosphate (CaP) cluster (AGIO@CaP) [33]. The AGIO core is initiated from a self-assembly induced by the aggregation of magnetic nanocrystallites, yielded from the interaction between the hydrophobic phase of amphiphilic gelatin and the adsorbed oleic acid modifying the nanocrystallites; the CaP shell is later formed by the electrostatic interaction between calcium ions and the carboxyl groups of the amphiphilic gelatin residues (Figure 4). The core-shell AGIO@CaP is designed and characterized as a multifunctional system offering an imaging modality and controllable release of DOX via pH reduction upon the cellular internalization by HeLa cells [33]. A reduced pH (5 – 6.5) is characteristic of the extracellular environment of tumorous tissue.

Figure 4.

(a) Scheme of AGIO, and TEM images of (b) AGIO@CaP, (c) AGIO@CaP-Dox of the first 30-second reaction, and (d) AGIO@CaP-DOX after 1-hour reaction [33].

The feasibility of modifications on gelatin prompted the development of controllable and/or multifunctional materials. Astilean et al. recently presented a nanochemotherapeutic system of gold nanoparticles coated with DOX-bound gelatin (AuNPs@gelatin) that was responsive to pH and temperature [87]. The design highlighted the functionality of imaging by combining fluorescence imaging techniques with confocal Raman microscopy, which efficiently monitored intracellular release and progressive accumulation of DOX [87]. In particular, the study utilized fluorescence lifetime imaging to confirm that the cytotoxic mechanism was induced by DOX-DNA interaction [87]. Despite that the complex did not necessarily show improvement in anticancer activity compared to free DOX in MCF-7 cells [87], such a strategy should be encouraged and further developed to gain insight into the mechanisms of delivery systems.

Similar to albumin, gelatin has also been investigated for delivery of paclitaxel [39] and methotrexate [43]. Gelatin nanoparticles encapsulating paclitaxel have been formulated to overcome the issue of drug dilution by urine during the treatment of intravesical bladder cancer [38]. The nanoparticles are prepared by first forming gelatin aggregates from solution in the presence of soluble paclitaxel using sodium sulfate. This is followed by dissolution of the aggregates and a glutaraldehyde-catalyzed cross-linking step [37].

Efficacy of these nanoparticles to yield appreciable concentrations of paclitaxel in the bladder has been proven in an in vivo study in canines, which indicates that nanoparticle-assisted delivery results in bladder concentrations of paclitaxel of 80% and 260% of the concentrations associated with water/ethanol and cremophor/ehtanol solvent formulations, respectively [37]. Methotrexate can also be readily entrapped in emulsions of gelatin to form nanoparticles of 100–200 nm in diameter, which may be further stabilized by cross-linking with glutaraldehyde, and behave as depots for sustained loading and release [42]. Cascone et al. have demonstrated a methotrexate release from gelatin nanoparticles over the course of 80+ hours determined by side diffusion chamber studies [42].

Benefited significantly from its GRAS status, gelatin protein has been implemented in a variety of ways to enhance the efficacy and bioavailability of small molecule therapeutics [31, 33, 37, 42, 86]. Much of the innovation coming forth pertains to the method of forming nano- or microparticles from gelatin, whilst encapsulating a small molecule. Some of these methods invoke chemical means to conjugate therapeutic moieties [31] or tailor the drug molecules to improve association with the carriers [142], while others rely on physical means to non-covalently form a bulk matter around therapeutic payload [86]. These examples demonstrate the versatility of this material as the foundation for a platform.

2.3b. Elastin-like Peptides

The exploration of the physicochemical properties of elastin, a fibrous protein composing the large arterial vasculature and other elastic tissues of vertebrates, and of the polypeptide motif that underpins its structure has been pursued since the work of Dan Urry in the 1970’s [143]. Elastin-like peptides (ELPs), artificial polypeptides abiding to the prototypical motif characteristic of elastin proteins, have been engineered as drug carriers [144]. ELPs are short repeating peptide motifs commonly of (VPGXG)n where X represents any guest amino acid except for proline [145]. The stimulus-responsive lower critical solution temperature (LCST) of ELPs makes them a unique biomaterial that can be controlled by temperature [145], which contributes to hyperthermia-targeted anti-tumor drugs and other applications in joint degeneration [146, 147] and neuroinflammation [47, 148]. Thus ELPs readily benefit as a delivery vehicle from the application of local hyperthermia to sites or regions of tissue delivery. ELPs further benefit from the EPR effect by virtue of their thermally actuated coacervation that is triggered in part by intermolecular interactions that follow an increase in structural order.

Chilkoti et al. provides an example of implementing ELPs as a small molecule delivery vehicle by conjugating particularly tunable sequences of the protein, synthesized with recombinant methods, to DOX through an acid-labile hydrazine bond that enables drug release in the acidic environment of lysosomes upon cellular uptake [30]. More specifically, ELP (VGK8G-(VPGXG)150, X=[V5A2G3] or VGK8G-(VPGXG)160, X=[V1A8G7]; X as Val, Ala, and Gly in ratio of 5:2:3 or 1:8:7, respectively) is reacted with succinimidyl-4-(N-maleimidomethyl)cyclohexane-1-carboxylate (SMCC). Following a separation step, the functionalized ELP is then reacted with doxorubicin-hydrazone and completed with a reduction of the terminal disulfide using tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine [30]. While the cytotoxicity of the conjugated DOX toward FaDu cells has been determined equivalent to that of the free DOX control, the results suggest that the intracellular localization of the therapeutic differed significantly; the free DOX localizes predominantly in the nucleus of cells while the conjugated form disperses uniformly throughout the cytoplasm with limited nuclear accumulation [30]. This precedent demonstrates the subtle differences in mechanisms of action amongst therapeutics and their delivery vehicle complexes, which highlights the notion that these mechanisms may be critical in the design of current and future delivery platforms.

Recent studies with the immunosuppressant rapamycin (Rap) have demonstrated that a serine-based ELP flanked by an isoleucine-based block and the FK506 binding protein (the Rap receptor) increases drug loading to 75% with sustained release improvement from 2 hours to nearly 60 hours [89, 90]. Validated with in vivo treatment, ELP-delivered Rap drastically reduces tumor growth in a human breast cancer model [90] and suppresses lymphocytic infiltration in the lacrimal gland as well as downregulates cathepsin S level in a mouse model of Sjögren's syndrome [89].

Recombinantly assembled and fluorescein-labeled ELP has been designed to coacervate out of solution 3–5 °C above physiologic temperature (37 °C) in a nude mouse model [149]. Image analysis of the fluorescence within the tumor vasculature after exposure to elevated temperatures demonstrates a significant increase and accumulation of ELP in the vascular compartment upon heating [149].

More recently the Montclare group has focused on the evolution of both coiled-coil- and ELP-based delivery strategies by interrogating a hybrid construct approach [91, 150]. The fusion with ELP repeats allow a COMPcc-based diblock and triblock copolymer to be thermoresponsive with transition temperatures ranging from 27.0 °C to 59.0 °C and particle diameters between 20 and 30 nm [91, 150]. These properties allow these block copolymers to be potentially amenable to hyperthermia applications and leverage the EPR effect due to the proximity of the transition temperature to physiologic conditions and the < 200 nm particle size [27]. Interestingly, the exchange of the orientation between COMPcc and ELP domain created different mechanical behaviors [91, 150]. The library of COMPcc leading at the N-terminus in the diblock polymers exhibited viscous character at room temperature, which was applicable for drug delivery and indeed examined by the binding with CCM [91]. The binding affinity (i.e. dissociation constant, Kd) of CCM to COMPcc domain varied from 4.7 µM to 17.0 µM, indicating that more work is still necessary to achieve competitive affinities to withstand in vivo non-specific competition for binding [19, 63, 151].

Among the diblock copolymers developed by Montclare et al., E1C and CE1, which exhibit optimal thermostability, have been employed to template gold nanoparticles (GNPs), generating protein polymer•GNP nanocomposites that improve the binding and delivery of CCM [92]. The hexahistidine tag engineered at the N-termini of both constructs allows templated-synthesis of GNPs upon reduction with the size of 3.5 ± 0.9 nm. These nanocomposites exhibit approximately 7.5-fold increase in CCM loading and greater than twice higher effective delivery to MCF-7 human breast cancer cells relative to the protein polymers in the absence of GNPs. In addition, the nanocomposites exhibit sustained release and less than 30% CCM is observed in 8.25 hours, whereas the non-templated protein polymers have released approximately 80% in the same time scale. This study has elevated the potential of hybrid biomaterials for binding capacity, targeted delivery and controlled release.

The trend amongst these examples of ELPs suggests that its primary usage is as a hyperthermic actuator for supramolecular assembly of proteins, leveraging the EPR effect for oncological applications [30, 149]. However, the block copolymers represent slightly innovative approach in blending the non-covalent binding capabilities of the coiled-coil proteins with the thermoactuated assembly of ELPs [91, 150]. For both methods however, the tuning and robustness of the thermoresponsive behavior of the whole drug-protein complex as well as the binding affinities and release dynamics are still yet to be optimized as robust and practical.

2.3c. Silk

Similar to elastin-like peptides, silk-like peptides are characterized by their signature repetition motif – i.e. (GAGAGS)n – that significantly promotes the bulk crystalline β-sheet structure of this class of proteins [11]. These sequences can be periodically interrupted with insertions of ELPs to impart a more amorphous and soluble property to the protein. These hybrid silk-elastin like peptides (SELP) can be tuned to form higher order structures such as porous films as well as thermoresponsive hydrogels [152].

Kaplan et al. developed SELP-based nanoparticles ((GAGAGS)m(GXGVP)n, n/m=8, 4, 2), with various ratios of silk to elastin blocks, to encapsulate DOX with a 6.5% loading capacity [93]. These delivery complexes are readily taken up by cells through endocytosis and exhibit therapeutic value by virtue of the DOX component alone; the delivery vehicle itself is not cytotoxic [93]. While the elastin block grants thermoresponsiveness, it is strictly incorporated to elicit the construction of a micellar-like encapsulation structure [93]. It in this manner, this application of ELP, when fused to another structural protein (i.e. silk) is for the purpose of directing a particular supramolecular architecture. Micelles, in this case, are optimal as energetically stable structures capable of encapsulating collections of small molecules within the adjustable boundaries of a defined morphology [153]. The Kaplan group has recently developed silk hydrogels with thixotropic properties to control gelation kinetics; the DOX-loaded hydrogel is injectable and recovers into a solid state quickly upon injection, exhibiting a sustained release over 8 weeks and improved anticancer activity in a breast cancer model [95].

Alternatively, Dams-Kozlowska et al. have developed functionalized silk spheres loaded with DOX [94]. The sequence of the silk (MAS(GRGGLGGQGAGAAAAAGGAGQGGYGGLGSQGTS)15) is recombinantly preceded by a HER2-recognition peptide sequence (MYWGDSHWLQYWYE or LTVSPWY), enabling targeted drug delivery and focused release of DOX [94]. These constructs bind more efficiently to cells that are overexpressing HER2 than those in the absence. Fusions with the HER2-recognition sequence located on the C-terminus do not exhibit the same affinity for HER2-positive cells [94]. The intracellular release of DOX from the nanoparticle is actuated by pH drop in lysosomes; this drop in pH activates acidic lysosomal proteases, which are speculated to degrade the delivery vehicle [94]. The solubility of DOX also increases in solubility at lower pH, concurrently promoting the release and dissolution of DOX in the cytosol.

These two prime examples of silk-like peptide engineering indicate the importance of sequence in designing and engineering the functionality of protein-based delivery vehicles. Leveraging the degradative forces of the cell and electrostatic shifts upon pH change are both methods of tuning the performance and efficacy of these delivery methods.

2.3d. Casein

Casein is the most abundant protein-based component that composes milk and defines a family of four related phosphoproteins, αS1, αS2, β, and κ [154, 155]. They are globular proteins of mixed secondary structure, but unlike most globular proteins, have a distinct supramolecular structure in the form of micelles [155]. This is in part due to the hydrophobic domains of the protein that lead to the formation of submicelles. However, it has been surmised that the frequent prolyl residues impart an architectural stiffness that yields an open structure with a rapidly fluctuating secondary structure [155]. The frequency of interspersed anionic clusters of phosphoseryl residues, within which calcium ions bind, is directly proportional to the solubility of the proteins [156–158]. These submicelles further internetwork via binding to colloidal calcium phosphate, which yields a microparticle network of casein macromolecules, varying in diameter from 20 nm to 300 nm [159]. Its porous, flexible, and macroscopic structure allows casein to form the basis for an encapsulation and delivery vehicle for several classes of small molecule.

Casein has been used to encapsulate, and thereby increase the solubility of hydrophobic small molecules such as vitamin D2 and curcumin [46, 96]. Livney et al. have made loaded casein microparticles with omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids as well as vitamin D2 by mixing solutions of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) or vitamin D2 (in ethanol) with a casein solution; the mixture is then stimulated to form micellar nanoparticles with sizes of 50–60 nm by the addition of calcium and phosphate [96].

Most significantly, the encapsulation of DHA by casein with high affinity (Kb = 8.38 × 106 M−1) reduces the oxidation and photo-oxidation of DHA and vitamin D2, respectively [96]. In a similar application, Moosavi-Movahedi et al. have employed casein to encapsulate CCM by dissolving and mixing both in organic solvent and subsequently resuspending in phosphate buffer [46]. In this case, casein exhibits an increased solubility of CCM by 2500 fold and the IC50 of CCM against K-562 cells decreases from 26.5 to 17.7 µmol/L [46]. It should be noted that in both cases, casein has shown to improve the chemical stability of compounds by virtue of non-covalent encapsulation and local environment provided by the comprising submicelles.

An example of an oncological application of casein is the entrapment and distribution of paclitaxel using casein nanoparticles on N-87 human gastric carcinoma cells, performed by Livney et. al [97]. With an entrapment efficiency of nearly 100%, paclitaxel is able to maintain its cytotoxic efficacy (IC50 = 32.5 nM) despite simulated digestion with pepsin [97]. Interestingly, the delivery complexes do not demonstrate cytotoxic effects prior to simulated digestion, highlighting an opportunity to leverage the enteral administration hurdles to the benefit of controlling release and/or triggering efficacy. In more recent studies, Menon et al. have hybridized casein with poly-L-lactide-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) to a nanocarrier of ~ 200 nm in diameter and showed a sustained and sequential release of dually loaded paclitaxel and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), demonstrating prolonged circulation of the nanoparticles [98]; Jiang et al. have engineered casein with poly(acrylic acid) that exhibits superior capability of internalization, targeting, and anticancer activity by inhibiting tumor growth 1.5-fold better than free cisplatin [99]. These modifications with biocompatible polymers have revealed the potential of casein to efficiently deliver therapeutics particularly hydrophobic molecules.

2.3e. Cage Proteins

Cage proteins refers to a class of natural proteins that adopt caged architectures that are defined by three surfaces (interior, exterior, and subunit interfaces) onto which chemical modifications and thereby functional modulation can be accomplished [100]. Cage proteins encompass a plethora of proteins, varying in origin, size (10–50 nm), molecular structure, and supramolecular structure, including viral capsids such as cowpea mosaic virus, heat shock protein, and ferritin [160].

Evans et al. have developed a delivery vehicle from Cowpea mosaic virus (CPMV), which is an icosahedral virus that is approximately 30 nm in diameter and is comprised of 60 copies each of two different coat proteins that form the asymmetric unit [29, 161, 162]. This notable example involves the covalent modification of CPMV with DOX via two ligation strategies: 1) a stable amide bond and 2) a labile disulfide bridge [163]. Conjugation with a stable amide bond induces time-delayed, but enhanced toxicity to HeLa cells compared to free drug [163]. The theory for the enhanced toxicity when delivered by way of CPMV assigns the mode of intracellular uptake, i.e. endocytosis, to the more even distribution and thus potency of the drug as compared to the diffusion and diluted diffusion of DOX to the nucleus [163]. Furthermore, it is considered that this mechanism of alternative uptake as well as enhanced potency may provide a means to overcome the efflux of therapeutic agents upon the adoption of drug-resistance [29].

Heat shock proteins (Hsp), a type of cage protein, exists in the cytosol as a chaperone and structural stabilizer to other intracellular proteins, particularly enacted during times of elevated cellular temperature or chemical/physical stress [164]. Douglas et al. have attached organic ligands to the exterior and interior surfaces of the small heat shock protein from the hyperthermophilic archeaon, Methanococcus jannaschii, for the purposes of cell targeting and therapeutic delivery [165]. This particular cage protein assembles from 24 identical subunits. RGD4-C peptide has been genetically incorporated into an Hsp variant (HspG41C) to enable αVβ3 and αVβ5 integrin targeting capabilities and displayed, enlarging the structure of the protein from 12 nm to 15 nm in diameter.

These variants successfully interact with C32 melanoma cells by virtue of the RGD moiety presentation [165]. Chemical linkages to an anti-CD4-antibody have been employed on the surface of HspG41C-RGD4-C labeled with fluorescein, leading to the successful targeting of CD4+ lymphocytes, assessed via FACS analysis [165]. Earlier the same group has successfully linked a derivative of DOX – (6-maleimidocaproyl) hydrazine – to the interior surface of the HspG41C protein cage via coupling of the maleimide and thiol moieties [100]. This hydrazone linkage is capable of releasing the active DOX molecule upon hydrolysis under the acid conditions, particularly within intracellular lysosomes. Approximately 50% of the DOX is released from such nanoparticles within 1.5, 3.9, and 5.1 hours at pH 4.0, 4.5, and 5.0, respectively [100].

Ferritin, a major iron storage protein found in living organisms, forms a 24 subunit cage-like particle with a diameter of 10 nm [13]. Xie et al. provide an example of how this protein can be loaded with a small molecule therapeutic [29]. By using a helper agent metal ion, Cu(II), they can increase the loading rate of DOX into ferritin nanoparticles from 14% to 73% wt/wt [29]. In addition, they covalently and post-translationally conjugated targeting and labeling moieties to the external surface of the nanocage by forming bonds with surface lysines [29, 166].

These examples of cage proteins demonstrate the viability of these nanoparticles to facilitate the encapsulation and triggered release of small molecule therapeutics to the cytosol in order to be effective. There is additional versatility in this platform due to the exterior surface area that can be mutated and/or functionalized with potentially little impact to the overall structure of the cage and the efficacy of encapsulation. In addition, precedence has been established for the PEG-ylation of cage proteins, specifically ferritin [167], suggesting that the hydrodynamic diameter and biocompatibility/availability of the delivery vehicle may also be modulated to a great extent.

2.4. Antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have been exploited as superior agents for drug delivery owing to their specificity and affinity to a variety of targets [78]. Maytansines and their derivatives, maytansinoids have been recognized as tumor-activated prodrug therapy by binding to tubulin and thus preventing microtubule assembly in tumor cells at the mitotic state [168]. Mertansine/emtansine (DM1) have been conjugated to several humanized mAbs against CanAg (discontinued) [101–103], CD56 [104, 169], PSMA (discontinued) [105], CD44v6 [106], and HER2 (Kadcyla®, Genetech). With different linker, ravtansine/soravtansine (DM4) is coupled with anti-CD19 to treat for relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) [110, 170].

The FDA-approved gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg®, Pfizer/Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories) is an antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) using anti-CD33 to carry the cytotoxic antibiotic calicheamicin [171, 172]. Chalicheamicin has been conjugated to anti-CD22 for the treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and ALL [109]. Other DNA damaging agents including duocarmycin and pyrrolobenzodiazepine are responsible for DNA minor groove alkylation and crosslinking, respectively [107, 108]. In recent studies, trastuzumab coupled with duocarmycin surpasses the efficacy of Kadcyla® in an in vitro treatment of patient-derived xenograft models, exhibiting potential against multi-drug resistance (MDR) [107]. The pyrrologenzodiazepine dimer conjugated with anti-CD33 demonstrates improved potency in comparison to Mylotarg® in vitro and in vivo in MDR models of acute myeloid leukemia [108]. Other therapeutics such as antifolates, vinca alkaloids, and DOX [173, 174] have been reported but with lack of potency in clinical trials [175]. Alternatively, not classified as canonical ADCs, radionuclides including yttrium-90 and iodine-131 have been conjugated to mAbs targeting CD20, CEA, Muc1, and tenascin [111] to exhibit cytotoxicity toward rapidly growing tumor cells for cancer therapy [176] and in vivo imaging [177].

The production of mAbs can be delicate and costly. However, current successes have been encouraging further expansion of antibody-directed delivery systems covering not only small molecules but also biological therapeutics such as genes and proteins [78].

3. Gene Therapeutics

Gene therapy encompasses the successful introduction of genetic material (nucleic acid-based therapeutics) including plasmid DNA (pDNA), gene-encoding DNA, antisense RNA, siRNA, and microRNA into malfunctioning cells for the non-transient, corrective up-regulation or down-regulation of endogenous proteins [7, 178]. While highly promising as a treatment for genetic disorders, including adenosine deaminase deficiency, inherited retinal dystrophy, and transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis, the critical action of translocating therapeutic nucleic acids to plagued cells remains a prominent challenge [179, 180].

Gene therapy has been a focus for therapeutic development since the 1980’s, with the breakthrough studies and trial to treat severe combined immunodeficiency secondary to adenosine deaminase (ADA-SCID) deficiency [179]. In these studies, retroviral cDNA delivery vectors have been used to transduce T-lymphocytes, which set the precedent effort for developing viral vectors as a leading therapeutic delivery modality [179]. Viral vectors remain the prominent (> 66%) yet declining method for therapeutic gene delivery amongst reported clinical trials worldwide. However, efforts toward the development of non-viral vectors have increased since the 2000’s through the present in order to address the realized safety issues with viral vector systems [7]. These non-traditional methods include amphiphilic lipid-based encapsulation (e.g. DOTAP, DOPE, DOTMA, DC-cholesterol, and Na-cholate) and cationic polymer complexation methods (e.g. polyethyleneimine, chitosan, poly(N-(2-hydroxypropyl) methylacrylamide)) [181–183]. Naked DNA has also been utilized as a delivery modality in clinical trials, relying on hydrostatic pressure gradients as a means to promote delivery to the intracellular compartment [7, 178]. Regardless of the methods, however, the primary challenge with respect to gene therapy is that of delivery, specifically pertaining to the local administration of the therapeutic complex, its cellular uptake, and the intracellular delivery hurdles necessary for efficacious transduction [7, 178] (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Challenges associated with delivering therapeutic nucleic acids. Nucleic acids can be applied to gene delivery (pDNA), anti-sense, siRNA, and mRNA [7, 178]. Commensurate with the chemical properties of nucleic acids are the challenges of enzyme degradation, renal excretion, immunogenicity, and non-specific interactions with serum proteins, all of which hinder the efficacy of the gene therapy. The successful path of delivery is defined first by vascular transport to the targeted body of tissue. Extravasation through the blood vessels occurs, allowing therapeutic molecules to be internalized by cells from the extracellular matrix. The internalization will most often encapsulate the cargo within an endosome. This endosome gradually converts to a lysosome or facilitates nuclear localization specifically for pDNA (denoted as *).

The mechanism behind this challenge of delivery hinges upon two cellular barriers. The electrostatic repulsion of the negative charges associated with the chemical backbones of nucleic acids and the lipid bilayer membrane of cells, specifically located on the phosphate groups along the length of nucleic acids and the head of the lipid molecules causing uptake of free nucleic acids to be infinitesimally miniscule under normal conditions [7]. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of nucleic acid delivery complexes necessitates a mechanism for escape from the intracellular endosome, which may be followed by a necessary step of nuclear import in the case of pDNA [7]. Formulations efforts to address these challenges may conflict with the toxicity of the delivery complex. In the case of cationic polymeric species, the ratio of charge between the cationic polymer and anionic nucleic acid has been shown to directly influence uptake and inversely induce cytotoxicity [184].

For the reasons highlighted previously, proteins can be an attractive delivery modality for this class of therapeutic. The refined control of sequence, and thus spatially structured charge distribution, provides a distinct advantage for larger proteins compared to other delivery modalities. Even smaller peptides, such as the class of cell penetrating peptides, while relatively unstructured, have yielded efficacious results in animal models [185, 186]. The hybrid of these approaches encompasses unstructured, structural proteins that are decorated with densely charged sites for complex formation [187–189]. These attributes result in a wide collection of protein-based delivery solutions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sizes and applications of protein-based delivery vehicles for nucleic acid payloads.

| Vehiclea | Nucleic Acid |

Cell/Modelb | Approx. Diameter (nm) |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supercharged Proteins | ||||

| scGFP | siRNA | HeLa human cervical cancer cells | 1700 | [188] |

| IMCD rat inner medullary collecting duct cells | ||||

| 3T3-L1 mouse embryonic fibroblasts | ||||

| PC12 rat phenochromocytoma cells | ||||

| Jurkat T cells | ||||

| E. coli tRNA | n/a | n.d. | [187] | |

| Salmon sperm DNA | n/a | n.d. | [187] | |

| CSP | pDNA | MC3T3-E1 mouse osteoblastic cells | 200~400 | [189] |

| Histones | ||||

| H2A | pDNA | COS-7 monkey kidney fibroblast-like cells | n.d. | [190] |

| H3 | pDNA | Chinese hamster ovary cells | <200 | [191] |

| NIH/3T3 mouse embryonic fibroblast cells | ||||

| Albumins | ||||

| CBSA | siRNA | A549 human lung carcinoma cells | ~ 255 | [192] |

| B16 murine melanoma cells | ||||

| HepG2 liver hepatocellular carcinoma cells | ||||

| B16 melanoma lung metastasis model in C57BL/6 mice | ||||

| RGD-HSA Tat-HSA | pDNA | HEK293T cells hMSCs | < 200 | [193] |

| Structural Proteins | ||||

| NiMOS | siRNA | Colitis-induced Balb/c mice | 280 | [194] |

| Silk | pDNA | 293FT human embryonic kidney cells | 380 | [195] |

| SELPs | pDNA | HeLa human cervical cancer cells | n.d. | [196] |

| FaDu human squamous cell carcinoma cells | ||||

| MDA-MB-435 human breast cancer cells | ||||

| IBNs (ELP) | pDNA | MCF-7 human breast cancer cells | 30~120 | [197] |

| ELR (ELP) | pDNA | C6 rat glioma cells | 150~180 | [198] |

| hFTH | Poly-siRNA | RFP-B16F10 cells | ~ 53 | [199] |

| Apo-huFH Apo-huFL | siRNA | Caco-2 human colon adenocarcinoma cells | n.d. | [200] |

| HepG2 human liver carcinoma cells hMSCs | ||||

| T-cells stimulated from PBMCs | ||||

Abbreviations: scGFP: super charged green fluorescent protein, CSP: positively charged COMPcc, CBSA: cationic bovine serum albumin, HAS: human serum albumin, NiMOS: nanoparticles-in-microsphere oral system, SELP: silk-elastin-like peptide, IBN: intelligent biosynthetic nanobiomaterial, ELR: elastin-like recombinamer, ELP: elastin-like peptide, mTat: modified trans-activator of transcription, hFTH: heavy chain of human ferritin, Apo-huFH: heavy chain of human apoferritin, Apo-huLH: light chain of human apoferritin.

Abbreviations: hMSCs: human mesenchymal stem cells, PBMCs: peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

3.1. Supercharged Proteins

The concept of recruiting the additional charge of particular amino acids into the sequence of a larger scaffold with existing structure and/or function has evolved in the last decade with the notion of supercharging well-structured proteins [187–189, 201, 202]. The predecessor to this work is the supercharged variant of green fluorescent protein (scGFP)[187, 188]. The recombinantly designed variant is decorated with point mutations of Lys and Arg along the surface-exposed area of the GFP beta barrel, resulting in a +36 theoretical net charge [188]. The additional surface charge distribution enables the construct to condense siRNA onto the globular surface of the protein, but also enables the intracellular transport of the delivery complex by way of binding to sulfated cell surface peptidoglycans. The scGFP demonstrates 100-fold greater gene internalization, as assessed by flow cytometry studies of Cy3-siRNA transfected HeLa cells [188].

More recently, a positively charged COMPcc (CSP) has been engineered and developed with cationic lipid formulation FuGENE® HD (FG) (Promega, WI, USA) as lipoproteoplexes for gene delivery [189]. CSP has been replaced with arginine at eight solvent exposed residues and thus carries a net positive charge, enabling it to robustly interact with the cell membrane. With the optimized ratio of CSP, pDNA and FG, the transfection efficiency to MC3T3-E1 mouse osteoblastic cells is increased by six fold over controls in the absence of CSP.

Supercharged proteins offer a simple and elegant strategy for imparting intracellular transport to a protein. In a certain case, the protein itself may be the cargo, e.g. scGFP [187, 188]. However, the prospect of co-transporting therapeutic cargo allows a supercharged construct to exist as a platform technology designed either to facilitate the transport of nucleic acids. Still, much work remains to assess the universal applicability of this strategy and whether off-effects potentially exist (e.g. the facilitated intracellular uptake of potentially cytotoxic compounds/macromolecules).

3.2. Histones

Several protein engineering groups have developed histone-inspired proteins for nucleic acid delivery [190, 191]. Histones are nuclear proteins responsible for the structuring of DNA into nucleosomes. The core subunit families of histones – H2A, H2B, H3, H4 – obey a three alpha-helix motif, separated by two loops [203]. They all exist as homodimers in the nucleus, which then compose larger hetero-octamers of each of the distinct four homodimers. This octameric structure displays the necessary surface charge to condense dsDNA [203]. Several groups have borrowed the structural features of histones to controllably complex synthetic nucleic acids [190, 191]. In the early 2000’s, Balicki et al. have identified a 37-aa N-terminal region of H2A that demonstrates active gene transfer and nuclear import of pDNA [190]. They reason that the successful delivery of DNA is facilitated by the condensation of pDNA onto H2A and nuclear localization signals in H2A that drive nuclear import. The former hypothesis has been tested by alterations to the helical structure of H2A, which negates its transport capability. Similarly, Sullivan et al. have investigated the capabilities of H3 tail peptides in the presence and absence of polyethylenimine, a cationic polymer transfection reagent [191]. The H3 tail peptides complexes with DNA and polyethylenimine promotes higher gene transfection than either alone, suggesting that histone-based peptides not only enhance the rate of gene expression, but also improve the efficiency of gene transfer via altered subcellular trafficking / improved nuclear delivery [191].

Histones are evolved to efficiently and robustly condense nucleic acid [204]. Hence, the advancement and engineering of histones for nucleic acid delivery is an ideal example of borrowing from nature’s toolbox the very function intended for a simple peptide and reapplying it outside its endogenous setting. Its most promising advantage over other strategies for nucleic acid delivery relies on the dynamics and mechanisms of subcellular trafficking and nuclear importation.

3.3. Albumins

Albumin possesses an isoelectric point around pH 5 and remains negatively charged in physiological conditions [205], which leads to inefficiency in gene delivery. Unmodified albumin mostly fails to bind nucleic acid materials and to penetrate cell and nuclear membranes [206]. Cationization of albumins is a common strategy to improve the transfection; however, the efficiency may still be limited [193]. In a study using cationic bovine serum albumin (CBSA) as the gene carrier, B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl2) specific siRNA exhibits decent antitumor activity in a B16 lung metastasis model when delivered by CBSA [192]. The expression level of Bcl2 is reduced by 50% when treated with CBSA binding siRNA. In addition, the complex enhances apoptosis twice as well as inhibits proliferation by an additional 20%. In spite of the improvement, CBSA overall exhibits similar efficiency to the commercial Lipofectamine 2000, which might not necessarily exploit the advantage of protein-based vectors [192].

More recently, HSA has been functionalized by two ligand peptides, RGD and Tat to develop HSA nanoparticles for cell-specific transfection [193]. The reporter plasmid of green fluorescent protein, pEGFP-N1 has been loaded to HSA via a well-established desolvation method to form nanoparticles, which are further stabilized by cross-linking. Upon the stabilization, the functional peptides are coupled with the nanoparticles through a PEG-based linker to finalize the formulation. The results indicate that simply 20% stabilization of HSA nanoparticles has led to higher gene expression levels in human embryonic kidney cells HEK293T possibly due to better release of plasmid compared to the 100% cross-linked nanoparticles. Furthermore, surface modification with Tat is more effective than RGD functionalization. However, in the case of human mesenchymal stem cells hMSC, both RGD and Tat modified HSA nanoparticles shows effective cellular uptake, but no gene expression [193]. Although album is generally recognized as a major category to deliver therapeutics, its development of efficiently transfecting nucleic acids may not yet be as substantial as for other payloads.

3.4. Structural Proteins

Structural proteins such as gelatin [207], silk [208] and elastin [209] are biocompatible and readily modified. In order to carry negatively charged nucleic acids, structural proteins can be decorated with positively charged amino acids to better associate with such cargos. In addition to PEGylated [210] and PCL-entrapped [194] gelatins, we describe the strategy of fusing a cationic block or introducing lysine residues in silk- and/or elastin-like peptides for gene delivery [195–198, 211].

3.4a. Gelatin

Gelatin has also been applied as a delivery vehicle for gene therapy [9]. First developed by Amiji group, gelatin modified with PEG has been employed as an intracellular delivery system [210]. In their recent preliminary study, type B gelatin nanoparticles entrapping siRNA for TNF-α silencing has been encapsulated by poly epsilon-caprolactone (PCL) microspheres to generate the nanoparticles-in-microsphere oral system (NiMOS) [194]. The promising results of down-regulations of TNF-α and other proinflammatory cytokines suggests its potential treatment for inflammatory bowel disease by oral administration [194].

3.4b. Silk & Elastin-like Peptides

Spider silk consensus repeats (SGRGGLGGQGAGAAAAAGGAGQGGYGGLGSQGT) containing a polylysine sequence has been developed for the delivery of pDNA [195]. The pDNA electrostatically interacts with the 30 lysines of the silk-based block copolymer, which leads to the formation of ion complexes with the size of 380 nm [195]. Upon the immobilization of the complexes on silk films, the pDNA is successfully transfected into human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells without cytotoxicity observed [195].

Silk fused with an elastin-like domain (SELPs) has also been investigated for virus-based gene delivery [196]; Hatefi et al. have demonstrated the feasibility of SELP ([(GVGVP)4GKGVP(GVGVP)3(GAGAGS)4]12) hydrogels in intratumoral adenoviral delivery for cancer treatment [196]. In this case, a SELP is used as an encapsulation matrix that allows the metered and sustained release of adenoviral delivery vectors for intratumoral gene therapy. This innovation addresses the rapid clearance problem associated with viral vectors upon injection into a tumor site [211].

SELPs are demonstrated to be a versatile material for the application of nucleic acid delivery. It may be applied as a depot for sustained release from an amorphous mass (e.g. hydrogel) [196], or more precisely layered at a particular density for uniform delivery to cell populations [195]. The alternative of forming nanoparticle structures is also suitable for nucleic acid condensation and delivery applications [197]. More importantly, these efforts fundamentally differ in the delivery challenges that they are attempting to address with particular SELP-based designs – i.e. rapid clearance, uniform delivery, and targeting control, respectively.

Isolated elastin-like polypeptide (ELP) has been investigated as a gene delivery carrier [197]. The intelligent biosynthetic nanobiomaterials (IBNs) are constructed by an ELP containing oligolysines (VGK8G-(VPGXG)60, X=[V5A2G3]; X as Val, Ala, and Gly in a ratio of 5:2:3) for the electrostatic interaction with pDNA [197]. With the thermoresponsive property of ELP, IBN serves as a platform for thermosensitive gene transfection. More recently, Piña et al. have fabricated an elastin-like recombinamer (ELR) by fusing a cell-penetrating peptide (CPP; RQIKIWFQNRRMKWKK) to an ELP ([(VPGIG)2(VPGKG)(VPGIG)2]24) at the C-terminus and a fusogenic peptide (LAEL)3 at the N-terminus [198]. While the CPP improves cellular internalization, the LAEL domain stimulates endosomal escape by causing structural change from a random coil to α-helix when the pH drops from physiological conditions to 5.0, destabilizing the endosomal membrane [212] for exogenous pDNA expression. In these studies, ELPs present potential to advance transfection with other functional motifs in addition to the modification with silk. With the tunable characteristics due to alternative amino acids at the guest position, ELPs can be further optimized for the purpose of gene delivery.

3.4c. Ferritin and Apoferritin

Recognized as a superior architecture to accommodate small molecules [213], ferritin is also capable of assisting the transfection of nucleic acid based therapeutics [199, 200]. In an earlier approach, the heavy chain of human ferritin (hFTH) has been genetically engineered with cationic peptides derived from human protamine, an arginine-rich chromatin-compacting sperm component, to allow the self-assembly into nanoparticles bearing 24 hFTHs displaying positive charges on the surface to interact with siRNA [199, 200]. In addition, along with the cationic peptide, tumor cell penetrating and targeting peptides have been fused at the C-terminus to ensure delivery. Evaluated with the gene silencing of red fluorescent protein (RFP) expression in tumor cells RFP-B16F10, the assembled hFTH particles complexed with the polymerized siRNA causes approximately 60% reduction in RFP expression compared to untreated cells [199, 200]. While the siRNA delivery in this study has been successful, the cellular uptake could be principally triggered by additional peptides targeting and penetrating tumor cells.

By contrast, Knez et al. have utilized unmodified human apoferritin, which is the demineralized form of ferritin, to demonstrate direct encapsulation of various siRNA molecules [200]. Apoferritin comprises a cage-like structure formed by heavy chain (apo-huFH) and light chain (apo-huFL) of ferritins and bears a cavity with 8 nm in diameter naturally used for the storage of iron in form of ferrihydrite [214]. Demineralization of ferrihydrite allows the cavity to be loaded with a variety of therapeutic cargos, followed by natural cellular uptake via receptor-mediated endocytosis [215]. After 12-hour treatments to the human colon adenocarcinoma cell line Caco-2, 85% and 70% knockdown by the siRNA against insulin receptor is achieved when encapsulated by apo-huFH and apo-huFL, respectively, while the commercially available transfection agent Lipofectamine 3000 only provides 40% silencing [200]. Although the efficiency could be aided by the presence of serum, the encapsulation of nucleic acid materials may better prevent the degradation by hydrolases and thus enhance gene delivery.

4. Therapeutic Proteins & Peptides

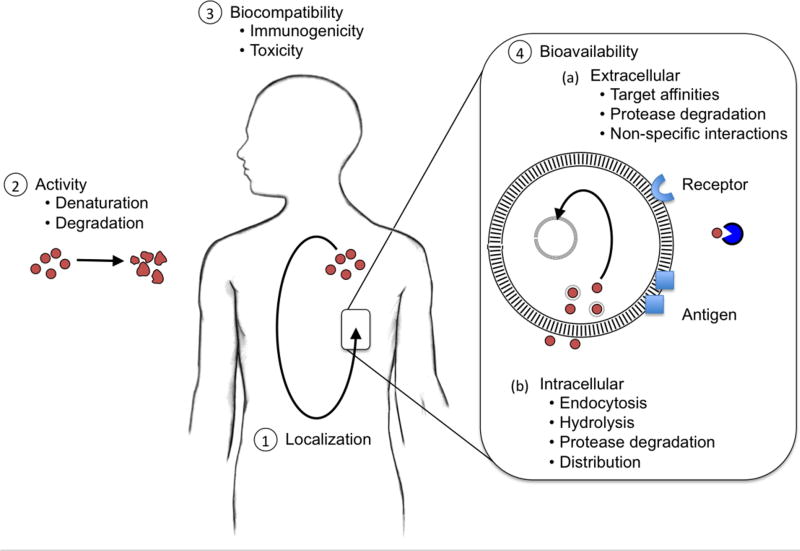

Therapeutic proteins and peptides (e.g. antibodies, and cytokines) fall to the mercy of the significant barriers posed by oral administration, and thus the promise of an orally available biologic remains elusive [216]. Protein- and peptide-based biologics are specifically susceptible to harsh conditions in the gastrointestinal tract (i.e. digestive acid and proteolytic enzymes) [216]. Electrostatic repulsions also play a role in limiting passage beyond the negatively charged mucous layer lining the epithelium of the digestive tract [217]. Thus, the prevalent hypothesis for the design and development of protein-based drug carriers is that they require parenteral administration. Therapeutic proteins and peptides including antibodies [218], cytokines [219], antimicrobial peptides [220], and hormones [221], still encounter challenges of localization, activity/stability, biocompatibility and bioavailability (pharmacokinetics and dynamics) (Figure 6) [17, 18, 222]. The challenges span multiple levels of scale, ranging from the paths for parenteral administration to the subcellular interactions with cell membranes and intracellular proteases [17, 18, 222].

Figure 6.