Introduction

As any person intersects with the current healthcare delivery system — in clinics, emergency departments or hospitals — care providers ask a series of questions to identify patients (name, age, date of birth) and take scientific measurements (height, weight, temperature, blood pressure, heart rate, etc.). These are necessary pieces of information to identify, understand and begin to create an individualized plan of care for the patient who is seeking healthcare services. The unique aspects of patients as individuals are often not discussed, however, such as the patients' preferences, culture and values and their expectations of the care experience. This creates significant gaps in the care interaction and in the care being provided. In this thought piece, we present a perspective on bridging these gaps by using patient narratives to provide more personalized care and create better care experiences.

Evidence-based practice

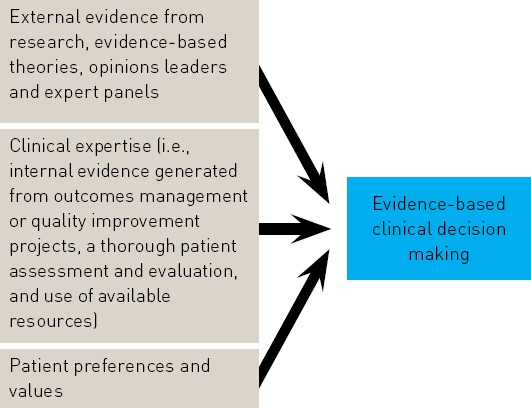

Healthcare organizations across the globe are working to implement an evidence-based practice culture. It has been widely recognized that evidence-based practice is instrumental in delivering the highest quality of healthcare and ensuring the best possible outcomes for patients.1 The U.S Department of Health & Human Services Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality defines evidence-based practice as “applying the best available research results (evidence) when making decisions about healthcare. Healthcare professionals who utilize evidence-based practice use research evidence along with clinical expertise and patient preferences.”2 Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt use the following figure (figure 1.1: The Components of EBP) to show how “EBP takes into consideration a synthesis of evidence from multiple studies and combines it with the expertise of the practitioner as well as patient preferences and values.” (p. 4). Figure 1.1: The components of EBP

This shows us that providing the highest quality of care and achieving the best possible outcomes for patients require healthcare providers to inquire about the patients' individual preferences, values and concerns. This valuable information should be included into an evidence-based approach to decision making about the care provided to the patient as an individual. Within our current healthcare delivery system, this information is often overlooked, not recorded within the electronic health record, and most alarmingly, not even discussed with the patient.

We have the technology

We are in an age where technology is sophisticated enough to help us achieve better quality and safety outcomes in healthcare. The technological infrastructure within the healthcare setting allows clinicians to enter patient data at the point of care and allows interprofessional team members to access the data when caring for the same patient in various settings throughout the delivery system. Electronic health records allow patients to access their records remotely via the Internet. These technologies also enable online communication with providers for patients to ask questions or get updates on test results. While we currently have the capability to record patients' first-hand accounts, this rich source of information is often excluded not only from the patients' electronic health record, and consequently from the delivery of care, but also from the evaluation of care experiences.

The MyStory© project is an illustration of the existing technological capability to support the use of patient narratives in the delivery of care. This project was funded on an Always Event™ grant by the Picker Institute in 2011. The MyStory© tool was initially developed with and for the pediatric patient population and was later expanded to include the adult population. This tool was used as a method to capture the individual story of each patient in responses to questions about the patient's values, preferences and expressed needs, such as, “What is your normal routine for sleep, meals and activities?” or “What comforts or calms you?” This tool made it possible to document this information within the electronic health record. All healthcare team members could then view this valuable information and use it to involve the patients in care decisions and care planning. The use of this tool allowed the care to be personalized to each individual patient and positively impacted patient satisfaction scores for the pediatric population. (Please refer to3 for more details and the impact of the MyStory© project.)

The perspective we present here is that a similar narrative approach should be used to gain analytical insights into patient experiences and improve satisfaction survey data. The narrative approach in the area of patient experience should concentrate on collecting short, first-hand narratives of specific incidents in the patients' care experiences. Patient narratives contain valuable information about the patient experience that numerical ratings from standard patient satisfaction surveys do not capture. A recent review of Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey responses from 589 patients at two hospitals showed that rating scales do not completely assess people's care experiences. While relatively few people give negative ratings, they can be more dissatisfied than their responses to survey questions indicate.4 The information about why an individual had a negative experience is in the patient's story and is not reflected in Likert scale-type responses to questions in standard satisfaction surveys.

Thought leaders in the field of patient experience acknowledge the importance of getting the patient's perspective to truly improve the patient experience.5 If a patient answered the HCAHPS question, “How often did nurses listen carefully to you?” by marking two responses, the system would recognize it as a “no response.” What if those two responses indicated “Day — Never, Night — Always”? This discarded response would contain very valuable information. When patient stories are collected and analyzed properly to provide the necessary context for quantitative data, they can reveal such subtle yet significant differences between a positive and a negative experience. Analytical capability to process both qualitative and quantitative data rigorously and at large scales is critical for identifying significant trends in patient experience to take focused action for improvement.

Call to action and implications for practice

Patient narratives need to be part of the evidence base that healthcare providers use to achieve the best outcomes for quality, safety and patient experience. It is at this moment in time that healthcare organizations are called to action to employ their patient experience representatives, along with their patient advisers and patient advisory boards, to implement tools and methods that enable the analysis of narratives from patients and their families and create actionable knowledge for the improvement of the patient's care.

According to the Institute of Patient and Family-Centered Care, “Patient- and family-centered care is an approach to healthcare that shapes policies, programs, facility design and staff day-to-day interactions. It leads to better health outcomes and wiser allocation of resources, and greater patient and family satisfaction.”6

Patient- and family-centered care (PFCC) will be more effectively achieved and patient experience will be significantly improved by including patient narratives into the evidence base that informs the delivery of care. The most valuable patient experience initiative should focus on 1) hearing and understanding our patients' stories that reflect their needs and preferences and 2) holding this information as valid as the quantitative data we have on our patients — from lab test results to the scores from patient satisfaction surveys.

Patient experience initiatives focused on patient stories would require us to build scientific rigor into the analysis of narrative data that describe care experiences in the patient's own words. If caregivers need to better understand their patients' experiences by “paying attention to anecdotal comments and complaints,”7 these anecdotal comments and complaints should be collected and analyzed through procedures that are as scientifically rigorous as those in place for the collection and analysis of quantitative data.

Patient narratives provide more valuable insights into patient experience than check-box responses to standard questions on patient satisfaction surveys. People make sense of their experiences in narratives that they construct out of “what actually happened” from their perspective. Asking patients to share short narratives on specific incidents that take place during clinical encounters would provide a robust source of qualitative data. These data can then be analyzed to show the type, frequency or emotional content of incidents that correlate with particular scores on surveyed areas of patient experience. This mixed methods approach would allow hospital administrators and clinicians 1) to know “why” they are being rated with particular scores and understand the drivers behind patient experience and 2) to know “how” to design the most effective patient experience initiatives for improved outcomes.

Application of mixed methods analysis to understanding patient experience

The mixed methods approach to understanding and improving patient experience requires the concurrent triangulation of qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis.8 In this approach, equal emphasis is given to both sources of data, where one is used to offset the weaknesses and add to the strengths of the other. Qualitative patient feedback, preferably in narrative form, should be analyzed to show categorical representations for comparisons with quantitative data. Currently, about 20 percent of HCAHPS surveys collected contain at least one written comment, and 58.6 percent of those who write comments make more than one comment.9 When surveys are administered on the phone, patients might provide narrative context to the option they choose on a scale from “always” to “never” for a particular survey question. Currently, contextual information such as “my nurse never remembered my name” is not recorded for analysis and is reduced to a low ranking in nurse courtesy and respect. Even with limited attention to qualitative feedback, patients want to share their experiences in their own words. When patients are asked to tell their story, they will provide invaluable incident-based insights into their care experiences. The integration of narratives with survey results will allow care providers to dig deeper into and learn from their patients' experiences and will enrich the evidence base of clinical decision making for PFCC.

Conclusion

Within the healthcare delivery system, we have become quite proficient at collecting data from patients and families to inform their care. Most often, these data are objective and quantitative — heart rate, blood pressure, temperature, lab values, etc. In order to provide holistic care to patients and families, all members of the interprofessional healthcare team need to be proficient in collecting information about the whole person — on the patient's body, mind and social environment. Healthcare providers need the capability to collect and process subjective and narrative, yet no less important, data to ensure that the care plan developed with the patient meets the patient's identified needs. Also, healthcare executives, leaders and providers need to advocate for the use of research solutions that help capture and probe into the patient's perspective in his or her own words.

We must get to know our patients in order to provide the highest quality and safest care and improve their care experiences. We need to think beyond satisfaction surveys to systematically collect and analyze our patients' stories. We should work on what questions we need to ask and when we need to ask these questions of our patients' experiences so that we get real-time insights into the care we provide. Regulatory changes and financial pressures are aligning with the movement of patient-centered care. Now is the time to develop new methods of learning from the stories of our patients and their families and build a new relationship with them in order to improve their care.

References

- 1.Melnyk Bernadette M. and Fineout-Overholt Ellen, Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice (Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Glossary of terms, http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/index.cfm/glossary-ofterms/?pageaction=showterm&termid=24.

- 3.Picker Institute Always Events, Always Events Toolbox, http://alwaysevents.pickerinstitute.org/?p=1033.

- 4.Smith Robert and Hoppertz John W., “The Value of Patient Handwritten Comments on HCAHPS Surveys,” Journal of Healthcare Management 59/1 (2014), 31–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merlino James and Raman Ananth, “Understanding the drivers of the patient experience,” Harvard Business Review Blog Network, September 17, 2013, http://blogs.hbr.org/2013/09/understanding-the-drivers-of-the-patient-experience/

- 6.“What is patient-and family-centered healthcare?,” Institute for Patient-and Family-Centered Care; http://www.ipfcc.org/faq.html. [Google Scholar]

- 7.“Understanding the drivers of the patient experience,” ibid. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Creswell John W.. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2009). 3rd ed. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith Robert and Hoppertz John W., ibid. [Google Scholar]