Abstract

The REDE model is a conceptual framework for teaching relationship-centered healthcare communication. Based on the premise that genuine relationships are a vital therapeutic agent, use of the framework has the potential to positively influence both patient and provider. The REDE model applies effective communication skills to optimize personal connections in three primary phases of Relationship: Establishment, Development and Engagement (REDE). This paper describes the REDE model and its application to a typical provider-patient interaction.

Introduction

Effective communication is the foundation for any relationship in healthcare, and our ability to consistently deliver high-quality care requires that this relationship be strong and meaningful. A significant tradition of work on the therapeutic alliance, patient-centeredness and relationship-centered care has long recognized the healing potential of the healthcare relationship.1 In our experience teaching relationship-centered communication to thousands of seasoned clinicians, we nonetheless recognized that many providers did not intuitively view forming relationships with patients as their role, nor did they perceive benefits of this mode of communication. In addition, in a world intensely focusing on patient experience, providers often feel left out. Subsequently, building upon the previous theoretical and empirical work, we constructed a model that put the concept of relationships in healthcare at the forefront. To further reinforce the concept, we directly correlated phases of the healthcare relationship to phases of the medical interview and communication skills therein. Emphasizing the premise that genuine relationships are a vital therapeutic agent,2, 3 use of this framework has the potential to positively influence both patient and provider.

The REDE Model

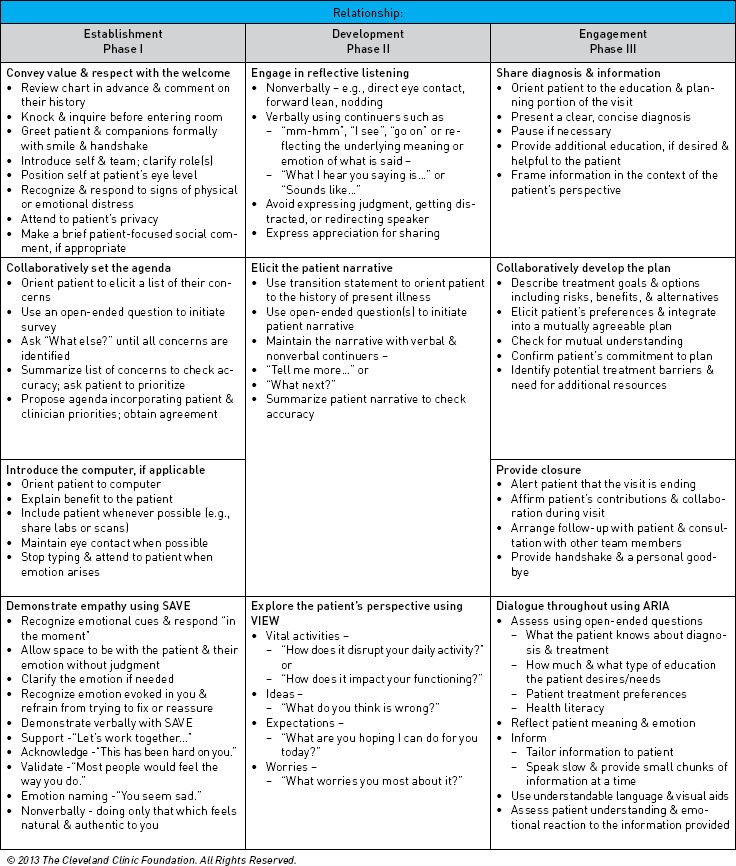

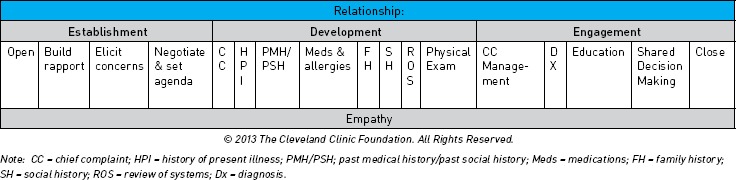

The REDE model of healthcare communication is a conceptual framework for teaching and evaluating relationship-centered communication. REDE harnesses the power of relationships by organizing the rich database of empirically validated communication skills into three primary phases of Relationship: Establishment, Development and Engagement (see Figure 1).4, 5, 6 Many models of healthcare communication exist.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 In our experience, several considerations led to the design of REDE, its resonance with advanced clinicians and implications for teaching. First, REDE is informative and also transformative because it challenges users of the model to explore their own assumptions and beliefs about patients and their role as providers. Second, we recognized that seasoned clinicians have performed countless interviews and often developed an unconscious competence in communication. Our teaching of REDE appreciates the skills clinicians already have, intentionally models relationship-centered communication in our facilitation method and encourages reflective competence by providing a common language that allows providers to reflect and refine their own skills. Third, the REDE model characterizes communication skills as tools in a toolbox, to be applied as needed. For the healing power of a relationship to be optimized, the skills must be presented in a manner that is genuine and authentic. If every provider was encouraged to recite the same lines of welcome, patients would perceive them as rote and impersonal. At the same time, we acknowledge that in early stages of learning, most newly introduced behaviors can feel scripted or unnatural until they become automated from repetition and practice. For ease of recall and utility, REDE also includes a mnemonic for each relationship phase that further supports the principles of relationship-centered care, as we have found, not unexpectedly, that learners codify information differently, and some appreciate explicit verbiage. Fourth, the REDE model can be generalized to a variety of settings. Because adult learning theory has shown that anchoring new information in what is already known facilitates learning,15 REDE skills can easily be woven into the traditional medical interview (See Figure 2) in both outpatient and inpatient settings and used across settings in a variety of conversations.

Figure 1:

The REDE Model Skills Checklist

Figure 2.

The REDE Model and the Traditional Medical Interview

Phase 1: Establish the relationship

Creating a safe and supportive atmosphere is essential for making a personal connection, fostering trust and collaboration. The emotion bank account is a concept originally proposed by psychologist and author John Gottman, Ph.D. It refers to a mental system for tracking the frequency with which we emotionally connect with other people.16 Each time an emotional connection is made, it is equivalent to making a deposit in the emotion account with that person. Building up the emotion account is important to sustain a personal connection. This way, when a withdrawal inevitably occurs, such as when a patient is forced to wait to see a provider, the emotion account does not automatically go into the red.

Convey value and respect with the welcome. In doing so, we are essentially building the emotion bank account with our patients and families. Given that people form first impressions very quickly and patients are discussing emotional and value-laden topics, how we set the stage for conversation matters, even it feels irrelevant to the clinical problem(s) at hand.17, 18, 19, 20 The skills outlined in Phase 1 are intended to create a climate conducive to the development of trust by demonstrating that the provider is receptive and interested in the person first, patient second.

Collaboratively set the agenda. Many providers fear this practice will sacrifice time necessary for assessing or treating the primary concern. However, research has shown that sharing in agenda setting not only facilitates partnership but also improves visit efficiency, diagnostic accuracy and patient satisfaction.21 Sharing in the agenda setting helps minimize our tendency to presume what a patient's concerns are and in what order of priority.

Introduce the computer. The electronic health record is a reality for most healthcare providers. How we introduce and utilize the computer should be explained as a means of enhancing patient care rather than detracting from it.

Demonstrate empathy. Empathy is the ability to imagine oneself in another's place and to understand that person's thoughts and feelings. In his book, “Empathy and the Practice of Medicine,” Howard M. Spiro, M.D., described empathy as “I and you becomes I am you or I might be you (p. 9).”22 Substantial research has examined the importance of empathy. Human beings are hard-wired to be empathic toward one another.23 Unfortunately, we also know that, without intervention, empathy declines through medical training, over time in practice and with task pressure.24, 25, 26 Our experience is that most providers care about their patients, but not all recognize emotional cues or respond to them. Making verbal statements of empathy has been shown to reduce the length of both an outpatient surgery and primary care visit.27 In REDE, every opportunity to convey empathy is encouraged, and the mnemonic SAVE is introduced for outlining different types of empathic statements a provider can use.

Phase 2: Develop the relationship

Genuine curiosity and interest are the necessary first steps in relationship building. However, once a safe and supportive environment has been created, the relationship needs to evolve and grow. Getting to know who the patient is as a person and understanding that person's symptoms in a biopsychosocial context is the next step. Developing the relationship also requires continued deposits into the emotion bank account and, thus, ongoing use of empathy.

Listen reflectively. Shown to enhance the therapeutic nature of a relationship, increase openness and the disclosure of feelings and improve information recall,28, 29, 30 reflective listening is vital for developing the relationship. Yet listening in such a way as to understand and acknowledge what is being said can be a deceptively complex and challenging skill.

Elicit the patient narrative. Obtaining the history of present illness (HPI) can quickly become a series of closed-ended questions that are of most interest to the provider.31, 32 However, the goal of this skill is to better understand the patient's perspective on his or her symptoms. This has been proven more efficient and effective than a provider-centered data gathering approach.33

Elicit the patient's perspective. Explanatory models are values, beliefs and experiences that shape a person.34 Being curious to explore and open to learn are key to knowing the person, their illness that is a social response to disease and the disease itself. The REDE model suggests a simple mnemonic VIEW to explore the patient's perspective.

Phase 3: Engage the relationship

The last step in relationship building aligns with the education and treatment portion of a patient encounter. Relationship engagement enhances health outcomes by improving patient comprehension and recall,35, 36 capacity to give informed consent,37 patient self-efficacy,38, 39, 40 treatment adherence and self-management of chronic illness.41, 42, 43

Share diagnosis and information. Telling a patient the medical facts and what he or she needs to know is not sufficient for effective care. We must also be sure the patient understands the information. Framing information in the context of the patient's perspective and engaging in dialogue that allows the patient to register new information and ask clarifying questions facilitates patient understanding.44, 45, 46, 47

Collaboratively develop a plan. Relationship engagement is designed to support patient understanding, decision making and consideration of potential treatment barriers. Treatment adherence and behavior change are more likely when the patient is an integral part of the planning process and agrees with the recommendations.48

Provide closure. Ending a visit can easily be taken for granted. However, reviewing the time spent and demonstrating respect and appreciation for the patient provides closure and engenders continued partnership.

Dialogue throughout. Patients are unable to comprehend and accurately recall a considerable amount of information presented during a typical medical visit.49, 50 Dialogue, as opposed to monologue, keeps the patient involved in the learning process51 and, more important, reflects the importance of the patient's role as head of his or her treatment team. In REDE, the sequence for engaging in this dialogue throughout the education and treatment portion of a patient visit is summarized by the mnemonic ARIA.

Summary

Effective communication is necessary to deliver safe, high-quality medical care. At the core of effective communication is the ability to develop meaningful relationships with patients. The REDE model builds on a significant research base including placebo, therapeutic alliance, communication skills and patient-centeredness that recognizes the healing potential of the healthcare relationship for not only patients but also providers. The REDE model helps frame the specific communication strategies that optimize their effect(s) on processes, outcomes of care and the patient-provider relationship itself. The REDE model also encapsulates evidence-based communication practices and our experience with seasoned clinicians, mostly staff physicians, within a large hospital system. It is hoped that such systemwide efforts will result in improved experience of care and self-efficacy for patients, and increased confidence, emotional connectedness and resiliency for providers. Future research will examine the generalizability of the REDE model for different contexts and provider types, as well as its potential to impact patient and provider outcomes.

References

- 1.Beach Mary Catherine Inui Thomas, and the Relationship-centered Care Research Network, “Relationship-Centered Care: A Constructive Reframing,” J Gen Intern Med 21 (2006): S3–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norcross John C.. Psychotherapy Relationships that Work [electronic resource]: Evidence-Based Responsiveness (2001), http://0-ebooks.ohiolink.edu.library.ccf.org/xtf-ebc/view?docId=tei/ox/9780199737208/9780199737208.xml&query=&brand=default. Accessed August 12, 2013.

- 3.Suchman Anthony L. and Matthews Dale A., “What Makes the Patient-Doctor Relationship Therapeutic? Exploring the Connexional Dimension of Medical Care,” Ann Intern Med 108 (1988): 125–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Street Richard L. Makoul Gregory Arora Neeraj K., and Epstein Ronald M., “How Does Communication Heal? Pathways Linking Clinician-Patient Communication to Health Outcomes,” Patient Educ Couns 74 (2009): 295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Safran Dana Gelb Taira Deborah A. Rogers William H. Kosinski Mark Ware John E., and Tarlov Alvin R., “Linking Primary Care Performance to Outcomes of Care,” J Fam Pract 47 (1998): 213–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ong L. M. L. DeHaes J. C. J. M. Hoos A. M. Lammes F. B.. Doctor-Patient Communication: A Review of the Literature,” Soc Sci Med 40 (1995): 903–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaughn F Keller V and Carroll J. Gregory, “A New Model for Physician-Patient Communication,” Patient Educ Couns 45 (1994): 23–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurtz Suzanne Silverman Jonathan, and Draper Juliet, Teaching and Learning Communication Skills in Medicine (2nd ed), (Abingdon Oxon, UK: Radcliffe Medical Press, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Makoul Gregory, “The SEGUE Framework for Teaching and Assessing Communication Skills.” Patient Educ and Couns 45 (2001): 23–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frankel Richard M. and Stein Terry, “Getting the Most out of the Clinical Encounter: The Four Habits Model,” Perm J 3 (1999): 79–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith Robert C., Patient Centered Interviewing: An Evidence Based Method (2nd ed), (Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cole Steven A. and Bird Julian, The Medical Interview: The Three Function Approach (2nded), (St. Louis: Missouri: Mosby Inc, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gregory Makoul and Bayer-Fetzer Conference on Physician-Patient Communication in Medical Education, “Essential Elements of Communication in Medical Encounters: The Kalamazoo Consensus Statement,” Acad Med 76 (2001): 390–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Effective Patient-Physician Communication, Committee Opinion No. 587, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Obstet Gynecol 123 (214): 389–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ivie Stanley D., “Ausubel's Learning Theory: An Approach to Teaching Higher Order Thinking Skills,” High Sch J. 82 (1988): 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gottman John and Silver Nan, The Seven Principles for Making Marriage Work, (New York: Three Rivers Press, 1999). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bar Moshe Neta Maital, and Linz Heather, “Very First Impressions,” Emotion 6 (2006): 269–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chaplin William F. Phillips Jeffrey B. Brown Jonathan D. Clanton Nancy R., and Stein Jennifer L., “Handshaking, Gender, Personality, and First Impressions,” J Pers Soc Psychol 79 (2000): 110–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Platt Frederic W. Gaspar David L. Coulehan John L. Fox Lucy Adler Andrew J. Weston Wayne W. Smith Richard C., and Stewart Moira, ““Tell Me About Yourself”: The Patient-Centered Interview,” Ann Intern Med 134 (2001): 1079–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barsky Arthur J., “Hidden Reasons Some Patients Visit Doctors,” Ann Intern Med 94 (1981): 492–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Makoul, “SEGUE Framework,” 23–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spiro Howard McCrea Curnen Mary G. Peschel Enid, and St. James Deborah, Empathy and the Practice of Medicine: Beyond Pills and the Scalpel, (Binghamton, NY: Vail-Ballou Press, 1993). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keysers Christian, The Empathic Brain: How the Discovery of Mirror Neurons Changes Our Understanding of Human Nature, Lexington, KY: Social Brain Press, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hojat Mohammadreza Vergare Michael J. Maxwell Kaye Brainard George Herrine Steven K. Isenberg Gerald A. Veloski Jon, and Gonnella Joseph S., “The Devil is in the Third Year: A Longitudinal Study of Erosion of Empathy in Medical School,” Acad Med 84 (2009): 1182–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cole and Bird, The Medical Interview. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spiro et al. , Empathy. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levinson Wendy Gorawara-Bhat Rita, and Lamb Jennifer, “A Study of Patient Clues and Physician Responses in Primary Care and Surgical Settings,” J Amer Med Assoc 284 no. 8 (2000): 1021–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coulehan John L. Platt Frederic W. Egener Barry Frankel Richard Lin Chen-Tan Lown Beth, and Salazar William H., ““Let Me See if I Have this Right…”: Words that Help Build Empathy,” Ann Intern Med 135 (2001): 221–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rautalinko Erik Lisper Hans-Olof, and Ekehammar Bo, “Reflective Listening in Counseling: Effects of Training Time and Evaluator Social Skills,” Am J Psychother 61 (2007): 191–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tallman Karen Janisse Tom Frankel Richard M. Sung Sue Hee Krupat Edward, and Hsu John T., “Communication Practices of Physicians with High Patient-Satisfaction Ratings,” Perm J 11 (2007): 19–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beckman Howard B. and Frankel Richard M., “The Effect of Physician Behavior on the Collection of Data,” Ann Intern Med 101 (1984): 692–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marvel Kim M. Epstein Ronald M. Flowers Kristine, and Beckman Howard B., “Soliciting the Patient's Agenda Have We Improved?” J Amer Med Assoc 281 (1999): 283–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weston Wayne W. Brown Judith Belle, and Stewart Moira A., “Patient-Centred Interviewing Part I: Understanding Patients' Experiences,” Can Fam Physician 35 (1989): 147–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carrillo Emilio J. Green Alexander R., and Betancourt Joseph R., “Cross-Cultural Primary Care: A Patient-Based Approach,” Ann Intern Med 130 (1999): 829–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ong et al. , “Doctor-Patient Communication,” 903–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heisler Michele Bouknight Reynard R. Hayward Rodney A. Smith Dylan, and Kerr Eve A., “The Relative Importance of Physician Communication, Participatory Decision Making, and Patient Understanding in Diabetes Self-Management,” J Gen Intern Med 17 (2002): 243–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schenker Yael Fernandez Alicia Sudore Rebecca, and Schillinger Dean, “Interventions to Improve Patient Comprehension in Informed Consent for Medical Procedures: A Systematic Review,” Med Decis Making 31 (2011): 151–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Street et al. , “How does Communication Heal,” 295–301. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heisler et al. , “The Relative Importance of Physician Communication,” 243–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schenker et al. , “Interventions to Improve Patient Comprehension,” 151–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heisler et al. , “The Relative Importance of Physician Communication,” 243–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roter Debra L. Stewart Moira Putnam Samuel M. Lipkin Mack Jr. Stiles William Inui Thomas S., “Communication Patterns of Primary Care Physicians,” J Amer Med Assoc 277 (1997): 350–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stewart Moira Brown Judith Belle Donner Allan McWhinney Ian R. Oates Julian Weston Wayne W., and Jordan John, “The Impact of Patient-Centered Care on Outcomes,” J Fam Pract 49 (2000): 796–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ong et al. , “Doctor-Patient Communication,” 903–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heisler et al. , “The Relative Importance of Physician Communication,” 243–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schenker et al. , “Interventions to Improve Patient Comprehension,” 151–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schillinger Dean Piette John Wang Kevin Grumbach Frances Wilson Clifford Daher Carolyn Leong-Grotz Krishelle Castro Cesar, and Bindman Andrew B., “Closing the Loop: Physician Communication with Diabetic Patients who have Low Health Literacy,” Arch Intern Med 163 (2003): 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mast Marianne Schmid, “Dominance and Gender in the Physician-Patient Interaction,” J Men's Health Gender 1(2004): 354–8. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ong et al. , “Doctor-Patient Communication,” 903–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heisler et al. , “The Relative Importance of Physician Communication,” 243–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schenker et al. , “Interventions to Improve Patient Comprehension,” 151–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]