Abstract

In neurology practices, the patient's caregiver is often overlooked, but it is essential to understand the importance of the caregiver in the management of a chronic neurological condition. Caring for a loved one with a chronic condition can often be profoundly fulfilling, as many times individuals move closer together when challenges arise; however it can also become overwhelming, physically and emotionally challenging, and isolating. At times, it can be thought of as a burden. Caregivers must learn to take care of themselves physically and emotionally. The multidisciplinary care model used in the treatment of chronic medical conditions is important not only for the patient or care recipient, but also for the caregiver. This care model allows for several practitioners to interact with the caregiver to assess and determine the optional interventions. The purpose of this article is to review common caregiver challenges and to determine how, as providers, we can address and help caregivers more effectively care for themselves while maintaining their responsibility to the patient or care recipient.

Keywords: caregiver, multidisciplinary team communication, loved one, chronic disease

Introduction

Chronic neurological conditions such as multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer's, Huntington's disease, stroke, Parkinson's disease, etc., have courses and durations that are unpredictable. As the diseases progress, the often-numerous and variable symptoms physically, emotionally and cognitively can create a need for family members or others to provide care. This responsibility often falls on the well partner/spouse or child. The long course and duration of many of the chronic neurological diseases frequently requires family members to play multiple roles, that of caregiver and of assuming the financial and household responsibilities. In some patients, the disease does not shorten lifespan, it complicates it, and so a caregiver's role can encompass many decades. Caregiving can be deeply satisfying as partners and family members can be drawn closer together. However, as the demands increase physically, emotionally and cognitively for the care recipient, often less time is available to be devoted to the caregiver's own needs, the children's needs, the home care or a career. Thus, caregivers often feel a significant demand and burden to their own endurance and coping mechanisms. Caregivers commonly report a plethora of their own physical and psychological symptoms. The purpose of this article is to review common caregiver challenges and to determine how, as providers, we can address and help caregivers more effectively care for themselves while maintaining their responsibility to the patient or care recipient.

Caregivers

A caregiver is an individual who helps with physical and psychological care for a person in need.1 As is the case for most caregivers, they are often family members, and they are usually unpaid. Caregivers can be called upon to provide a wide variety of assistance with activities of daily living, including bathing, toileting, dressing, transferring, cooking, eating, medications and managing the home. Demographically, 66 percent of family caregivers are women, and remarkably, 65 percent of care recipients are women. In addition, the typical caregiver spends approximately 20 hours per week in caregiving duties.2, 3

Caregiving for a loved one with a chronic condition can be profoundly fulfilling, as individuals often move closer together when challenges arise. However, caregiving can also be daunting, emotionally and physically challenging, and isolating. At times caregiving results in caregiver burden, which Buhse 2008 defines as “a multidimensional response to physical, psychological, emotional, social and financial stressors associated with the caregiving experience”.4 The challenges of caregiving are widespread and encompass much more than the care of the recipient, as will be noted below.

Impact on the caregiver

Individuals and families living with chronic neurological conditions are dealing with the kinds of care needs that they had not anticipated managing for years or decades into the future. While family members anticipate a time when they will care for a parent or spouse, few anticipate managing this reality at the point in which it occurs, be that while developing as an individual, raising a family or preparing for retirement. It is rare that there are friends or role models who can help guide someone who takes on caregiving responsibilities through the emotional, physical, psychological and financial challenges they are facing. Individuals and families have likely given some thought to how they will adjust their lifestyle, along with their siblings and friends as they age, but they have to manage these life style changes now. It can be a very lonely and frightening feeling.

Impact on social relationships

One of the most common consequences that caregivers describe is a sense of imbalance in the relationship with the family member who is receiving care. The substance and content of that connection, whether it is that between life partners or an adult-child and an elderly parent, shifts away from the relationship and becomes more focused on the tasks of caregiving and managing decreasing resources of time, energy and finances that so often accompany chronic illness. This sense of loss can be especially profound when the care partner experiences significant cognitive impairment. Relationships with other family members and close friends may be neglected as increasing energy is directed to care provision. Some spouse caregivers have described the loss of a social life as their “couple” friends are uncomfortable inviting them individually to dinner or a movie because their care partner is too tired or disabled to participate. As the caregiver has increasing responsibilities at home, he or she may maintain other roles such as an employee or a member of a religious congregation, and that person may have to forgo to the social aspects that can be a significant component of those relationships. Caregivers sometimes describe themselves as the forgotten member of the relationship as family, friends and acquaintances ask about the well-being of their partner but not how they themselves are doing.

Impact on physical and psychological health

The physical well-being of caregivers is often compromised because caregiving often involves some level of physical effort. This need for hands-on helping may be episodic as during an MS exacerbation that may occur once every year or two, or it may be ongoing and increasingly complex. Few caregivers have had the benefit of any formal training in safely executing the physically stressful activities such as assisting with transfers or helping their care partner dress or get up from the floor after a fall. Caregivers can easily injure themselves during the simplest of caregiving tasks but don't have time to seek medical care for the injury or a substitute caregiver to give them time to recuperate. Caregivers often neglect their own routine health care needs, including health maintenance and treatment for their own health conditions such as high blood pressure or anxiety disorder. They often attribute this limited self-care to a sense that there isn't enough time to make these appointments, or they are so tired of attending appointments with their care partner that they have medical visit fatigue. If managing their own physical and psychological medical conditions is a low priority for caregivers, they are even less likely to participate in wellness activities that can be so important for themselves and those for whom they care.

Impact on finances

The cost of managing chronic neurological disease is well documented and astronomical, with a total annual cost per year in the U.S. of $100 billion to care for people with dementia, $23 billion for persons with Parkinson's Disease and $450 million for persons with MS. It is estimated that up to 40 percent of that cost for each disease is attributable to the uncompensated care provided by family caregivers.5, 6 While these aggregated dollar figures are huge, they do not convey the cost to individual families when the caregiver is also the primary wage earner, often working at relatively low-paying job that is needed to allow flexibility for caregiving. This can make a family's financial situation even more complicated because such jobs do not provide health insurance for the caregiver or other family members. Often the needs caused by the chronic illness assume financial priority in a family and that may influence decisions about if the family goes to the same out-of-state amusement park where “everyone else” is going, if or where a child will go to college, what needed house repairs are completed, or how long an old, no-longer-dependable car is the family's primary vehicle. These are hard decisions to make in most families but are especially difficult for families living with chronic illness who have to budget for every resource in their lives.

Emotional impact

Addressing the emotional reaction to being a family caregiver is the most daunting of these topics to address. As has been discussed, caregiving can be a remarkably emotionally rewarding experience, especially when the caregiver and his or her chronically ill family member can manage the illness in the context of their fuller, richer lives and when they can do that in partnership. As the balance tips away from that partnership toward the caregiver sensing that he or she is going it alone, that caregiver will inevitably feel difficult and unwelcome negative emotions. These negative emotions may be short-lived and overcome, especially when that caregiver is able to rally internal and external resources to generate positive coping strategies. But as caregivers find themselves in a very real and unavoidable way with fewer opportunities or strategies to regain positive emotional energy, negative emotions understandably emerge. These emotions for caretakers can range from anger (at their partner, the illness, their god), to a depression and regret at their own weakness, to a deep sadness about the loss of the life they had hoped and planned for as an individual and a couple or family. Often grief is the root negative emotion that caregivers experience. Grief is a normal and healthy emotion, and it might be over the loss that the caregiver has experienced at the loss of the care partner to the chronic illness, especially as that partner loses cognitive functioning or the ability to control his or her bladder or bowels. Grief that results from a loss that is final, such as the death of a loved one, is a healthy and normal process that is often eased by the rituals and active support that come with such events. The grief that accompanies ongoing caregiving does not come with that same sort of closure and is often ongoing, which can lead to a cascade of negative emotions and behaviors that, in extreme circumstances, can result in suicide or abusive behaviors. It is part of our job as health care providers to prepare the caregivers and our patients for these potential emotions and reactions, and help them to build a network of resources that can provide an essential element of support.

Needs of the Caregiver

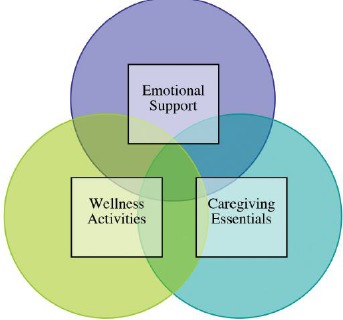

Significant and healthy human relationships are successful only when they are reciprocal and mutual. The care recipient may need a great deal of assistance, but the needs of the caregiver must also be met in order for the relationship to remain healthy. Although several directions could be taken regarding the importance of self-care, this section will address what one might consider the trifecta of self-care (Figure 1).7

Figure 1.

(adapted from reference 7): The Trifecta of Caregivers Self-Care

A. Emotional support

Caring for someone with a chronic illness can lead to decreased quality of life, a decline in psychological health, increased stress, and depression and anxiety.4, 8–10 Research has clearly demonstrated the negative emotional consequences of caregiving, which can lead to dysfunctional coping skills, strained relationships, reduced life satisfaction, and emotional and physical illness.11–13 In addition, the stress of caregiving can precipitate psychological disorders such as anxiety and depression. It is not uncommon for caregivers to identify a need for treatment from a mental health provider, but few actually seek the needed help.14, 15 Recognizing the issue is important, but following through is vital. Failure to seek help has been identified as a factor in caregiver burnout and mental health disorders.

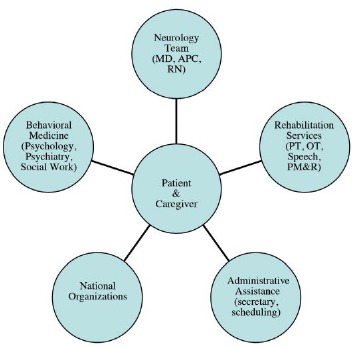

The most efficacious management of a chronic disease for both the care recipient and caregiver is from access to high-quality comprehensive care teams of skilled professionals that include attention to symptom management and quality of life (Figure 2).7 This level of care is not always available and requires a shift from the traditional medical model to a more functional model of care, incorporating the concerns of the patient or care recipient, family member and caregiver. Included in a successful multidisciplinary team for the management of chronic diseases are the physician, advanced practice clinicians, psychologist, psychiatrist, physical therapist, occupational therapist, social worker, nurses, speech therapy, national associations and administrative support (Figure 1).7 This model allows for several practitioners, organizations and even the administrative support to interact with, assess and determine what types of interventions to recommend for the caregiver. When this type of a team can be assembled, an optimal level of care for both the patient and his or her family of caretakers can be provided. If a member of the medical team becomes aware of a patient or family member's difficulty (emotionally or physically), or if there are unaddressed needs, coordination of care can begin to address these issues. For those who are unable to practice within a team setting, developing referral listings and partnering with local organizations with a common interest in chronic disease care are highly recommended.

Figure 2.

(adapted from reference 7): Patient and Caregiver Multidisciplinary Care Model

Oftentimes, referrals to mental health practitioners are in order for the caregiver. Mental health practitioners have specific interventions, with the aim of reducing caregiver burden and improving mental and physical health. Sharing emotions with others relieves stress and may offer a different perspective on problems. These are helpful steps to improve the emotional and physical health of caregivers. When referring to a mental health practitioner, it is important to pick a provider who has extensive experience in chronic disease management and who understands the complexities of how the chronic disease affects the entire family. Early recognition by a clinician or by the caregiver themselves is linked with successful outcomes.16 In addition to individual mental health services, there are national organizations and societies of specific diseases (e.g., The Alzheimer's Association, The Huntington's Disease Society of America, The National Multiple Sclerosis Association, etc.) that offer a variety of programs aimed at helping ease the emotional burden, such as support groups, psychoeducational programming, referrals to mental health providers and web chats.

B. Caregiving essentials

Caregivers often come into the role of caregiving as a necessity and have no previous knowledge of skill. They may take the learn-as-you-go approach, which can create more stress. In addition, oftentimes being the sole care provider comes with additional responsibilities, including, but not limited to, career, parenting and household chores. As highlighted above, the relaying of information and referral to services such as the national societies or associations can be helpful in providing caregivers with useful skills. Please be open to discussing and brainstorming ways to help ease these household task burdens (e.g., hired help, enlisting other family members or friends, etc.) for the caregiver.16, 17

C. Wellness activities

The behavioral medicine literature is full of studies that show the power of physical activity and wellness in self care. In general, research has demonstrated that engaging in exercise and physical activity significantly enhances both physiological and psychological health.18–21 The benefits of exercise and physical activity have been documented across a wide array of health areas, including chronic disease prevention and control, mental health and health related quality of life.18–21 Many caregivers neglect their own emotional, physical and spiritual needs. Wellness encompasses healthy all-around living. Some studies suggest eating a balanced diet, getting at least seven hours of restorative sleep, regular exercise (i.e., 30 minutes of aerobic exercise four or more days a week), caring for emotional health by way of a mental health provider, maintaining friendships and hobbies, and for those with a spiritual alignment, spending time on that.16, 17

Within the multidisciplinary team of medical professionals, each and every member should take a moment to assess and address caregiver needs. When assessing a caregiver, “10 Tips for Caregivers to Avoid Burnout” (Table 1)7 can be helpful.

Table 1.

(adapted from reference 7):

| 10 Important Tips for Caregivers to Avoid Burnout |

|

Summary and conclusions

It is our hope that this article has raised your awareness that living with a chronic illness is truly a family affair. We recommend that you consider that while our patients with chronic neurological diseases will be in our immediate care only a few times a year, they are in the constant care of their families throughout their lives. It is essential, therefore, that we include these family caregivers as members of our health care team and do our best to assure, even if we do not directly provided that care, that they receive the same mental and physical health care and access to wellness that we are responsible for providing to our patients.

Table 2.

(adapted from reference 7)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

References

- 1.Hileman J Lackey N Hassaneien R. Oncology Nursing Forum. 1992; 19: 771–777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Family Caregivers Association. Caregiving Statistics. Retrieved June 20, 2012, from: http://www.thefamilycaregiver.org/who_are_family_caregivers/care_giving_statstics.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pandya S. Caregiving in the United States. Retrieved June 20, 2012, from: http://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/il/fs111_caregiving.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buhse M. Assessment of caregiver burden in families of persons with multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing. 2008; 40(1):25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neurological Disorders: Public Health Challenges. Retrieved June 19, 2014. from: (http://www.who.int/mental_health/neurology/chapter_3_a_neuro_disorders_public_h_challenges.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parkinson's disease Foundation. Statistics on Parkinson's. Retrieved June 19, 2014, from: (http://www.pdf.org/en/parkinson_statistics). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sullivan AB. Caregiving in multiple sclerosis. In Rae-Grant A Fox R Bethoux F (Eds.), Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders: Clinical Guide to Diagnosis, Medical Management, and Rehabilitation. Demos publishing, 2013. New York, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patti F Amato MP Battaglia MA et al. Caregiver quality of life in multiple sclerosis: A multicentre Italian study. Multiple Sclerosis. 2007; 13:412–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Figved N Myhr K Larsen J et al. Caregiver Burden in multiple sclerosis: The impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms. J Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2007; 78:1097–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sherman TE Rapport IJ Hanks RA et al. Predictors of well-being among significant others of person with multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis. 2007; 13:238–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Brien MT. Multiple sclerosis: Stressors and coping strategies in spousal caregivers. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 1993; 10:123–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Brien RA Wineman NM Nealon NR. Correlates of the caregiving process in multiple sclerosis. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice. 1995; 9:323–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gulick EE. Coping among spouses or significant others of persons with multiple sclerosis. Nurs Res. 1995;44:220–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buchanan RJ Radin D Chakravorty B et al. Informal care giving to more disable people with multiple sclerosis. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2009; 31:1244–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buchanan RJ Radin D Huang C. Caregiver burden amount informal caregivers assisting people with multiple sclerosis. International Journal of MS Care. 2011; 13:76–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National MS Society. A guide for caregivers: Managing major changes. Retrieved June 10, 2012: http://www.nationalmssociety.org/search-results/index.aspx?q=caregiver+support&start=0&num=20. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holland NJ Schneider DM Rapp R Kalb RC. Meeting the needs of people with primary progressive multiple sclerosis, their families, and the healthcare community. International Journal of MS Care. 2011; 13:5–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sullivan AB Covington E Scheman J. Immediate benefits of a brief 10-minute exercise protocol in a chronic pain population: A pilot study. Pain Medicine. 2010; 11(4):524–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bouchard C Shephard RJ Stephens T. Physical activity, fitness, and health: International proceedings and consensus statement. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brownell KD O'Neil PM. Obesity. In Barlow DH, Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual (2nd Ed.) New York: Guilford: 318–361. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirkcaldy BD Shephard RJ Siefen RG. The relationship between physical activity and self-image and problem behaviour among adolescents. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2002; 37:544–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]