Abstract

Given the necessity to better understand the process patients need to go through in order to seek treatment via medical marijuana, this study investigates this process to better understand this phenomenon. Specifically, Compassion Care Foundation (CCF) and Stockton University worked together to identify a solution to this problem. Specifically, 240 new patients at CCF were asked to complete a 1-page survey regarding various aspects associated with their experience prior to their use of medicinal marijuana—diagnosis, what prompted them to seek treatment, level of satisfaction with specific stages in the process, total length of time the process took, and patient’s level of pain. Results reveal numerous patient diagnoses for which medical marijuana is being prescribed; the top 4 most common are intractable skeletal spasticity, chronic and severe pain, multiple sclerosis, and inflammatory bowel disease. Next, results indicate a little over half of the patients were first prompted to seek alternative treatment from their physicians, while the remaining patients indicated that other sources such as written information along with friends, relatives, media, and the Internet persuaded them to seek treatment. These data indicate that a variety of sources play a role in prompting patients to seek alternative treatment and is a critical first step in this process. Additional results posit that once patients began the process of qualifying to receive medical marijuana as treatment, the process seemed more positive even though it takes patients on average almost 6 months to obtain their first treatment after they started the process. Finally, results indicate that patients are reporting a moderately high level of pain prior to treatment. Implication of these results highlights several important elements in the patients’ initial steps toward seeking medical marijuana, along with the quality and quantity of the process patients must engage in prior to obtaining treatment. In addition, identifying patients’ level of pain and better understanding the possible therapeutic value of medical marijuana are essential to patients and health practitioners.

Keywords: patients perspective, medical marijuana, cannabis, policies and procedures, community engagement project

Introduction

Based on new laws, there are 23 states and the District of Columbia that are legally able to prescribe the use of medical marijuana. However, given the relative novelty of this practice coupled with the federal illegal classification of cannabis, the use of it for medicinal purposes is anything but straightforward (1). As more and more states pass laws legalizing the use of marijuana for medicinal purposes and as research highlights its therapeutic values (2 -11), so too will patient demand. However, currently little is known about the process that patients experience prior to obtaining the use of medical marijuana.

The US Drug Enforcement Administration lists marijuana and its cannabinoids as schedule 1 controlled substances. This means that they cannot legally be prescribed under federal law due to (a) high potential for abuse, (b) no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States, and (c) lack of accepted safety for use under medical supervision (2). Despite this however, some physicians and the general public alike are in broad agreement that Cannabis sativa shows promise in combating diverse medical illnesses (1). Given the federal law, physicians could wind up in jail for writing a prescription for medical marijuana, and thus, many states have passed laws allowing the use for medicinal purposes. In those states, health-care practitioners provide an “authorization” for that use and, based on previous court action, are considered by federal courts to be protected physician–patient communication (12). However, even though by law health-care practitioners are able to prescribe medical marijuana, it is not clear what patients must go through in order to be eligible to receive it and specifically how long this process takes.

Medical Marijuana and Patients’ Process

Senate Bill 119, approved in January 2010, protects “patients who use marijuana to alleviate suffering from debilitating medical conditions, as well as their physicians, primary caregivers, and those who are authorized to produce marijuana for medical purposes” from “arrest, prosecution, property forfeiture, and criminal and other penalties.” It also provides for the development and implementation for alternative treatment centers (ATCs); specifically, the creation of at least 2 each in the northern, central, and southern regions of the state. (13) Physicians determine how much marijuana a patient needs and gives written instructions to be presented to an ATC. The maximum amount for a 30-day period is 2 ounces. The approved conditions for the use of medical marijuana are as follows—seizure disorder, including epilepsy, intractable skeletal muscular spasticity, glaucoma; severe or chronic pain, severe nausea or vomiting, cachexia, or wasting syndrome resulting from HIV/AIDS or cancer; amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Lou Gehrig disease), multiple sclerosis, terminal cancer, muscular dystrophy, or inflammatory bowel disease, including Crohn disease; and terminal illness, if the physician has determined a prognosis of less than 12 months of life or any other medical condition or its treatment that is approved by the Department of Health and Senior Services.

As of April 23, 2014, there were ATCs with permits to operate in all 3 regions of the state as designated by the medical marijuana program—north, central, and south. Compassionate Care Foundation (CCF; note 1) is one of these ATCs located in the southern region of New Jersey. Compassionate Care Foundation by law is only required to assess patient level of pain every 90 days, but given their commitment to this process and their patients, CCF wanted to identify the process that patients had to go through prior to treatment. The ability of Compassionate Care Foundation to gather such data would hopefully shed light on this new endeavor in order to not only better understand the process but also provide solid data to legislators to help shape the policies and procedures regarding the availability and dissemination of medical marijuana. In light of this situation, CCF decided to reach out to Stockton University hoping to partner in this problem-solving solution.

The goal of this partnership was to better understand the process that patients experienced in order to be eligible to receive medical marijuana. Specifically, to understand the following about patients seeking the use of medical marijuana (a) patient diagnosis, (b) what prompted patients to seek treatment, (c) patients’ level of satisfaction with specific stages in the process, which entails locating certified physician, referrals, making appointments; navigating Web sites that includes payment, getting approval, communications with the state, contact an ATC, and overall satisfaction with the process, (d) total length of time of this process, and (e) patient’s level of pain. Compassionate Care Foundation’s vision is that a better understanding of patients’ experience will provide valuable information that can help shape future policies and procedures for patients’ use of medical marijuana. Therefore, the following research questions (RQs) were posed:

RQ1: For what diagnosis are people using medical marijuana?

RQ2: How did patients begin the process to seek medical marijuana?

RQ3: a. What did patients experience during the process?

b. How long did the process take?

c. How satisfied were patients with the overall experience?

RQ4: What was patient’s base level of pain?

Methodology

The Public Health Program at Stockton University, located in Galloway, New Jersey, partnered with CCF in order to ascertain the process that patients experienced prior to receiving treatment—the use of medical marijuana, at CCF. In order to accomplish this, a 6-month-long study was conducted to explore various aspects associated with what patients experienced prior to receiving their first treatment at CCF.

Variables

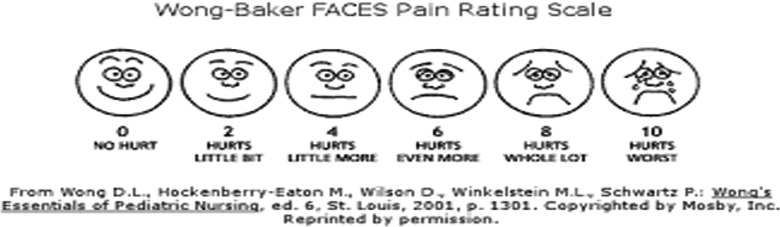

Compassion Care Foundation reached out to Stockton’s Public Health Program to assist with constructing an instrument that would identify specific variables associated with patients’ process prior to their first treatment of medical marijuana at CCF (14). This level of research is not yet required by law but illustrates CCF’s dedication to understanding this process to help guide future policies and procedures. Specifically, this preliminary study was designed to discover initial behavior that patients engaged in to start the process. This was measured nominally by asking patients to indicate what first prompted them to seek alternative treatment, whether they did their own research and if so, where did they obtain their information. Next, patients were asked to report their specific experience with different stages of getting approved to use medical marijuana, overall experience, length of time the process took, and baseline pain of patients prior to their first treatment at CCF. In order to measure the 9 variables associated with the process, along with overall satisfaction, a 10-point systematic differential scale (negative to positive) was developed, 1 question per variable due to patient time restraints (see Appendix A for the entire 1-page survey). In addition, time of process was operationalized by months, and baseline pain was operationalized by a pictorial version of the pain scale (Wong-Baker Face pain rating scale; this scale was chosen by CCF administration).

Procedures

Data were collected for 8 months between the months of June 2014 and January 2015 and were completely voluntary (informed consent was also provided). Any patient seeking treatment for the first time at CCF during these months was asked to fill out the above 1-page survey.

Sample

By the end of the 8 months, paper surveys were filled out by N = 240 total new patients: 32.4% female, 50.7% male, and 17% missing for gender. The age of the patients ranged from 9 to 84 years, with a mean of 49.3 and standard deviation of 13.6.

Results

In order to answer the above RQs, basic descriptive and frequency statistics were computed on SPSS. The following are the results:

RQ1: For what diagnosis are people using medical marijuana?

| Rank | Diagnosis | n | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Intractable skeletal spasticity | 72 | 30% |

| 2nd | Chronic/severe pain | 62 | 26% |

| 3rd | Multiple sclerosis | 41 | 17% |

| 4th | Inflammatory bowel disease | 24 | 10% |

| 5th | Seizure disorder | 14 | |

| 6th | Terminal illness/cancer | 12 | 5% |

| 7th | Glaucoma | 10 | 4% |

| 8th | Muscular dystrophy | 4 | 0.016% |

| 9th | Lateral sclerosis | 3 | 0.012% |

| Cancer (specific types) | 3 | 0.012% | |

| Crohn disease | 3 | 0.012% | |

| 10th | Nausea | 2 | Less than 1% |

| 11th | Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy | 2 | Less than 1% |

| 12th | Depression/anxiety/bipolar | 1 | Less than 1% |

| Epilepsy | 1 | Less than 1% | |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | 1 | Less than 1% | |

| Langerhans cell histiocytosis | 1 | Less than 1% |

RQ2: How did patients begin the process to seek medical marijuana?

| What prompted patients to seek treatment | Total number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Their physician | 132 | 55 |

| Written information | 37 | 15 |

| Friend | 31 | 13 |

| Media | 25 | 10 |

| Relative | 21 | 8 |

| Website | 8 | 3 |

| Support group | 3 | 1 |

| Conducted their own research on alternative treatments | 187 | 78 |

| Used the Internet to conduct research | 104 | 43 |

| Sought information from a physician | 15 | 6 |

RQ3: a. What did patients experience during the process?

| Steps in the process | Range | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Locating a certified Myeloma physician | 1-10 | 8.37 | 2.46 |

| Setting up an appointment | 1-10 | 8.60 | 2.32 |

| Getting a referral number | 1-10 | 8.4 | 2.46 |

| Communication from state | 1-10 | 8.02 | 2.65 |

| Wait time to get approval | 1-10 | 7.70 | 2.74 |

| Navigating the website | 1-10 | 7.90 | 2.47 |

| Providing documents via website | 1-10 | 7.67 | 2.84 |

| Payment online | 1-10 | 8.43 | 2.50 |

| Contacting an ATC | 1-10 | 9.20 | 1.62 |

b. How long did the process take?

| Range | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| 1-36 months | 5.8 months | 6.87 months |

c. How satisfied were patients with the overall experience?

| Range | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| 1-10 | 8.75 | 1.91 |

RQ4: What was patient’s level of pain?

| Range | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| 0-10 | 7.57 | 2.14 |

Discussion

Given the necessity to better understand the process patients need to go through in order to seek treatment via medical marijuana, this study investigates this with hopes to paint a clearer picture of this process. Specifically, these findings shed light on various aspects associated with patients’ experience prior to their use of medicinal marijuana. First, results reveal numerous patient diagnoses that medical marijuana is being prescribed. The top 4 most common are intractable skeletal spasticity, chronic and severe pain, multiple sclerosis, and inflammatory bowel disease. Next, results of basic descriptive statistics indicate the majority of patients (a little over half) were first prompted to seek alternative treatment from their physicians. However, it is important to understand that physicians will not be prescribing marijuana for patients; rather, they will be certifying that a patient has a “debilitating medical condition” eligible for medical marijuana according to state regulations. Also, physicians are not required to certify any patient, and some may decline to do so, given the federal ban or limited clinical evidence (15).

While the remaining patients indicated that other sources such as written information along with friends, relatives, media, and the Internet persuaded them to seek treatment. These data indicate that a variety sources play a role in prompting patients to seek alternative treatment and is a critical first step in this process. Continued research on the therapeutic value of medical marijuana will provide physicians and patients with accurate and updated information.

Patients also indicate whether they engaged in any research on their own prior to seeking treatment. A little over three-quarters of the sample indicate doing their own research on seeking alternative treatments. Further investigation revealed that almost half of participants conducted this research via the Internet, while only a small percentage did so by obtaining information from their physician. Mostly likely, given the format of this question (open ended), half of the participants left this question blank. This is consistent with past research that states that physicians are no longer autonomous when it comes to patients’ health. As stated by Ludwig and Burke (16) article entitled Physician–Patient Relationship:

The historical model for the physician–patient relationship involved patient dependence on the physician’s professional authority. Believing that the patient would benefit from the physician’s actions, a paternalistic model of care developed. Patient’s preferences were generally not elicited, and were over-ridden if they conflicted with the physician’s convictions about appropriate care. However, during the second half of the twentieth century, the physician–patient relationship has evolved towards shared decision making. This model respects the patient as an autonomous agent with a right to hold views, to make choices, and to take actions based on personal values and beliefs. Patients are acknowledged to be entitled to weigh the benefits and risks of alternative treatments, including the alternative of no treatment, and to select the alternative that best promotes their own values.

Thus, as evaluating the details of one’s medical history and current condition is his/her doctor’s job, the more informed a patient is about their own health, the more empowered and confident they will feel about effectively managing their illness or injury.

Further implication of these results highlights 2 important elements in the patients’ initial steps toward seeking medical marijuana. First, the patients will look toward physicians to provide them with information regarding the use of medical marijuana. However, many physicians may still be on the fence and searching for information themselves. As Thorson, president-elect for Nelson (17) states:

Some health care providers are sitting out completely while others are ready to start certifying patients, most are waiting to decide whether they’ll play a role, hoping for answers to concerns that range from dosing and side effects to the risk of losing out on funding by violating federal law, which still bans dispensing marijuana. There are a lot of unanswered questions here and it will be a work in progress. We just have to realize that.

Thus, the role that physicians play in this process is still developing. One thing for sure is that many patients will look toward them for knowledge and guidance.

As a result of this guidance, the second implication for the physician–patient communication is critical. Specifically, physicians may have to take the lead on the initial dialogue regarding medical marijuana. Marijuana is a controversial substance that has been painted in an intensely negative light by decades of moral condemnation, punitive legislation, and fear-mongering media coverage and public service announcements. For many patients, particularly those among the older generations, asking their doctor about medical marijuana may not be as easy as inquiring about the benefits of “normal” medications produced by pharmaceutical manufacturers. For example, best-selling, name-brand prescription drugs are not scheduled substances—they simply don’t invoke the same attitudes and anxieties (18). Thus, given that patients may be uncomfortable initially broaching the subject, physicians may need to take the lead in this communication. However, patients still need to play an active role, especially if their physician is less supportive about this possible option. Ultimately, patients need to keep in mind that their health and well-being is also in their control. Thus, if physicians are not supportive or judgmental about patients’ questions regarding medical marijuana, those patients have a right to be proactive and ask questions/seek medical advice on this line of treatment. Patient must take an active role in their own health care, seeking a variety of sources to help make better informed decisions about their care. Again, continued research on medical marijuana will positively contribute to this stage of the process for both physicians and patients.

Once patients began the process of qualifying to receive medical marijuana as treatment, the process seemed more positive than not. Specifically, patients reported between 70% and 80% positive experience with regard to locating a certified MM physician, getting a referral, and setting up an appointment. Similarly, patients report favorable experience with communication with the state, wait time, and the website—which included navigating the site, providing documents, and payment. Finally, patients’ easiest step in the process was contacting an ATC. Thus, these individual variables are consistent with patients’ high overall satisfaction with the experience. Finally, results indicate that on average it takes patients almost 6 months to obtain their first treatment after they started the process. In light of these findings, the length of time patients reported for the overall process seems even more interesting. Although almost 6 months seems rather lengthy to obtain treatment, patients are reporting an overall high satisfaction and ease with going through the process. Thus, these results may suggest that while patients are able to navigate through the steps, maybe the time required to go through each of these steps needs to be revisited. This is where future policies and procedures could revisit each level to ascertain whether the process could be more efficient in terms of the length of time. Results of the last RQ indicate patients report on average a moderately high level of baseline pain prior to seeking treatment via medical marijuana. This coincides with the second highest patient diagnosis of chronic/severe pain and past research that suggests that medical marijuana may be an effective option for not only pain relief but also for other physical and mental health problems, especially given the epidemic of addiction and overdose deaths from prescription opioids (19). Cannabis and its active ingredients are a much safer therapeutic option and effective for many forms of chronic pain and other conditions but have no overdose levels. Thus, these results appear consistent with current literature and indicate many chronic pain patients could be treated with cannabis alone or with lower doses of opioids (19,20). Identifying patients’ level of pain and better understanding the possible therapeutic value of medical marijuana are essential to patients and health practitioners.

As with most studies, there are several limitations to this study. This was a voluntary self-report survey, which lends to more predictive rather than causational relationships. In addition, given the voluntary nature of the study, not all patients participated. Also, variables were only measured quantitatively and with 1 item. These factors along with time constraints associated with administering the surveys certainly influence the quantity and quality of information obtained. Thus, results should be interpreted with such knowledge of methodology and sample construction. In addition, the sample consisted entirely of residents of New Jersey (mostly Central and Southern New Jersey) and may be a factor to consider with external validity/generalizability of results.

Therefore, the overall purpose of this study is to investigate the process in which patients experience in order to seek the use of medical marijuana as treatment to health-related conditions. Specifically, this community engagement project investigated patients’ process to seek and obtain the use of medical marijuana, along with patient diagnosis and baseline pain.

Results provide insight into many aspects associated with what prompted patients to seek the use of medical marijuana and how physicians, along with access to reliable and valid information, play an essential role in this process. In addition, patients indicate a high level of satisfaction with the various steps associated with getting approval for the use of medical marijuana, even in light of the average length of time the whole process takes.

Future efforts should focus on each of these steps to determine the efficiency of each phase as it relates to the process as a whole. Overall, patients’ knowledge about what they can expect to experience in each phase of this process provides insight to the types of tasks they will need to perform and how long each step may take. This can better prepare them for when they may want to begin this process, especially given that patients report a fairly high level of baseline pain prior to starting the use of medical marijuana as an alternative treatment. Also, understanding how each is connected may provide ways to reduce the amount of time the entire process takes. Despite its limitation, this partnership between CCF and Stockton University provides valuable knowledge regarding patients’ process toward seeking the use of medical marijuana as treatment with a key message:

Although patients are overall satisfied with the process, it may take up to 6 months, and since patients report experiencing moderately high levels of pain, starting the process as early as possible is advisable.

Understanding and sharing this information with the community will hopefully contribute to building and maintaining an effective and efficient process for physicians and patients to understand and access medical marijuana as an alternative treatment for health-related conditions.

Author Biography

Tara L Crowell received her PhD from University of Oklahoma in Health and Interpersonal Communication. She is an associate professor of Public Health at Stockton University where she teaches Statistics and Research Methods and Coordinates undergraduate internships.

Appendix A

This survey is to be filled out once by each patient

Please respond to the following questions prior to obtaining services at Compassionate Care.

1. What initially prompted you to seek alternative treatment for your condition? (circle all that apply) Physician Friend relative Written information media Web site Support group Other

-

2. Did you do any research on your own about alternative treatment? Yes No

If yes, where did you obtain your information?

3. Once you decided to start the process of alternative treatment, please rate the following steps in terms of your experience (1 = negative to 10 = positive)

| Locating a certified MM physician | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Setting up an appointment | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Getting a referral number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Communication from the state | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Wait-time to get approval | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Navigating the Web site | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Providing documents via website | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Payment online | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Contacting an ATC | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Overall experience | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

4. Approximately how long did it take you to received Alternate Treatment Care for your condition, from start to finish (once you decided to seek treatment until your first treatment):____________________

5. Please use the scale below and circle your level of baseline pain

Inter-office use only (to be filled out by Staff)

Note

CCF is a nonprofit corporation organized in the state of New Jersey to provide therapeutic relief by dispensing pharmaceutical-grade medical marijuana to patients with qualifying medical conditions. Founded in 2011, Compassionate Care is led by a board of directors whose members are medical professionals, former health department regulators, community leaders, and researchers. Compassion Care Foundation is committed to providing New Jersey patients with safe and affordable medical marijuana. Compassion Care Foundation has 2 charitable missions—the first is to provide high-quality medicine to patients in need and the second is to expand the understanding of the clinical effects of medical marijuana and how it should be used in the treatment of different diseases and conditions. The Foundation is committed to providing qualifying patients, their caregivers, and their health-care providers with current, scientifically accurate care and information about medical marijuana. Compassion Care Foundation serves residents of New Jersey through their office located in Egg Harbor Township.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article.

References

- 1. Bostwick MJ. Blurred boundaries: the therapeutics and politics of medical marijuana. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(2):172–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kramer J. Medical marijuana for cancer. CA Cancer Clin. 2015;65(2):109–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ellis RJ, Toperoff W, Vaida F, et al. Smokes medicinal cannabis for neuropathic pain in HIV: a randomized, crossover clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;34(3):672–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Abrams DI, Vizoso HP, Shade SB, Jay C, Kelly ME, Benowitz N. Vaporization as a smokeless cannabis delivery system: a pilot study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;82(5):572–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Izzo AA, Camilleri M. Emerging role of cannabinoids in gastrointestinal and liver diseases: basic and clinical aspects. Gut. 2008;57(8):1140–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marx J. Drug development: drugs inspired by a drug. Science. 2006;311(5759):322–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Roser P, Vollenweider FX, Kawohl W. Potential antipsychotic properties of central cannabinoid (CB1) receptor antagonists. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010;11(2 pt 2):208–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chang A, Shiling D, Stillman R, et al. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol as an antiemetic in cancer patients receiving high- dose methotrexate. a prospective, randomized evaluation. Ann Intern Med. 1979;91(6):819–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chang A, Shiling D, Stillman R, et al. A prospective evaluation of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol as an antiemetic in patients receiving adriamycin and cytoxan chemotherapy. Cancer. 1981;47(7):1746–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lane M, Smith FE, Sullivan RA, Plasse TF. Dronabinol and prochlorperazine alone and in combination as antiemetic agents for cancer chemotherapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 1990;13(6):480–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Musty RE, Rossi R. Effects of smoked cannabis and oral delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol on nausea and emesis after cancer chemotherapy: a review of state clinical trials. J Cannabis Therapeut. 2001;1(1):29–42. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aggarwal SK, Carter GT, Sullivan MD, ZumBrunnen C, Morrill R, Mayer JD. Medicinal use of cannabis in the United States: historical perspectives, current trends, and future directions. J Opioid Manag. 2009;105(1-2):1–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. State of New Jersey. 213th Legislature, Senate, No. 119. 2008. Web site ftp://www.njleg.state.nj.us/20082009/S0500/119_I1.HTM.

- 14. Wong DL, Hockenberry-Eaton M, Wilson D, Winkelstein ML, Schwartz P. Wong’s Essentials of Pediatric Nursing. 6th ed St. Louis: Mosby, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ehrlich A, Hill K. Physician’s Focus: is marijuana really medicine? 2014. Web site https://www.thereminder.com/features/healthfitness/physiciansfocusism/.

- 16. Ludwig M, Burke W. Physician-patient relationship. Ethics Med. 2014. Web site http://depts.washington.edu/bioethx/topics/physpt.html.

- 17. Nelson T. Why Medical Marijuana is off to a slow start in MN. MPR News 2015. Web site https://www.mprnews.org/story/2015/07/17/medical-marijuana-minnesota.

- 18. Tishler. How to talk to your doctor about Medical Marijuana. inhale MD 2014. Web site http://inhalemd.com/massachusetts-medical-cannabis-guide/how-to-talk-to-your-doctor-about-medical-marijuana/.

- 19. Carter GT, Javaher SP, Nguyen MV, Garret S, Carlini BH. Re-branding cannabis: the next generation of chronic pain medicine. Pain Manag. 2015;5(1):13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kral AH, Wenger L, Novak SP, et al. Is cannabis use associated with less opioid use among people who inject drugs? Psychiatr Res. 2015. Web site http://www.drugandalcoholdependence.com/article/S0376-8716(15)00250-1/abstract?cc=y=.