Abstract

IMPORTANCE

The hereditary progressive ataxias comprise genetic disorders that affect the cerebellum and its connections. Even though these diseases historically have been among the first familial disorders of the nervous system to have been recognized, progress in the field has been challenging because of the large number of ataxic genetic syndromes, many of which overlap in their clinical features.

OBSERVATIONS

We have taken a historical approach to demonstrate how our knowledge of the genetic basis of ataxic disorders has come about by novel techniques in gene sequencing and bioinformatics. Furthermore, we show that the genes implicated in ataxia, although seemingly unrelated, appear to encode for proteins that interact with each other in connected functional modules.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

It has taken approximately 150 years for neurologists to comprehensively unravel the genetic diversity of ataxias. There has been an explosion in our understanding of their molecular basis with the arrival of next-generation sequencing and computer-driven bioinformatics; this in turn has made hereditary ataxias an especially well-developed model group of diseases for gaining insights at a systems level into genes and cellular pathways that result in neurodegeneration.

The Hereditary Ataxias: A Historical Perspective

By the mid-19th century, physiologists working with experimental animals had demonstrated that lesions of the cerebellum cause motor incoordination.1 Practicing physicians, however, were slow to link clumsiness in their patients to cerebellar dysfunction, largely because incoordination can also result from a lack of position sense (proprioception). The term ataxia was first used by the French neurologist Guillaume-Benjamin Duchenne2 in 1858 to describe progressive sensory tabetic incoordination that affects the dorsal column. In 1899, the well-known Polish neurologist Joseph Babinski3 described the clinical features and signs of cerebellar ataxia.

Considering this delay, it is remarkable that familial ataxias were recognized almost at the same time as the earliest descriptions of cerebellar ataxia. The German neurologist Nikolaus Friedreich4 was the first to describe patients with a familial ataxia that now bears his name (1863). However, whether the ataxias he described were simply variants of acquired ataxias, most notably tabes dorsalis, was subject to debate at that time because tertiary syphilis was endemic. However, because more patients with hereditary ataxia were observed, the existence of Friedreich hereditary ataxia became firmly established. With this debate settled, another arose as to whether familial ataxias other than Friedreich ataxia existed. This idea was initially raised by the Parisian neurologist Pierre Marie,5 who compiled in 1893 a list of hereditary ataxias that differed from Friedreich ataxia in their later age of onset, abnormalities of eye movements, and brisk tendon reflexes. Around this time, the conceptual advances in genetics along with the rediscovery of the mendelian theory of inheritance made it clear that Friedreich had described the first recessive ataxia, whereas Marie had reported the first autosomal dominant ataxias.

Further progress followed, particularly with respect to identifying novel recessive ataxias, because many of these diseases have associated clinical features that make them relatively easy to diagnose and differentiate. Key examples include Wilson disease,6 ataxia telangiectasia,7 ataxia with vitamin E deficiency,8 and storage/metabolic disorders (including Niemann-Pick disease,9 metachromatic leukodystrophy,10 and cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis11). The autosomal dominant ataxias, on the other hand, were more problematic to characterize owing to their large phenotypic overlap. Initial classifications were attempted based on postmortem histopathologic criteria.12,13 However, these attempts did not help the practicing neurologist seeing the patient in the clinic. In the 1980s, the British neurologist Anita Harding proposed a clinical classification for autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxias by dividing them into 3 classes based on bedside examination results, specifically, whether the patient displayed a pure ataxic syndrome or additional neurologic features such as retinopathy or ophthalmoplegia, or extrapyramidal features.14 The real breakthrough came from further conceptual advances pointing to different genetic causes, specifically stemming from the concept of genetic linkage that demonstrated several loci responsible for ataxia. The first spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA1) locus was mapped to chromosome 6, benefiting from linkage to the HLA antigen complex.15 Other ataxias were assigned to genomic loci using new molecular tools to map the genome. Initially these tools included restriction fragment length polymorphisms,16 followed by simple sequence length polymorphisms, sequence-tagged sites, and single-nucleotide polymorphisms.17–19 At present, 43 numbered SCA types are based on the temporal order of establishing linkage, with variable prevalence of these subtypes in different populations.20 This classification scheme has largely replaced the Harding classification, and the final diagnosis is now a genetic test that can be performed using DNA extracted from blood.

In addition to these progressive ataxic syndromes, some ataxias occur episodically and are therefore called episodic ataxias (EAs). These ataxias are also inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. Patients with EAs experience recurrent episodes of poor coordination and balance, coupled with progressive interattack weakness, dystonia, and ataxia. First described by VanDyke and colleagues21 in 1975, the known EA subtypes have been numbered, like the SCAs, from EA1 through EA7.22 The same numbered nomenclature has more recently been adapted for the autosomal recessive ataxias in the genetic era.

In addition to the autosomal disorders, a few ataxias are X-linked and a few are mitochondrially inherited. The most common X-linked ataxia is the fragile X–associated tremor ataxia syndrome.23,24 Mitochondrial ataxias include the syndrome of neuropathy, ataxia, and retinitis pigmentosa25 and others. A comprehensive list of all known hereditary ataxias is reported in eTable1 in the Supplement, and more information can be found on the web portal of the Neuromuscular Disease Center at Washington University, St Louis (http://neuromuscular.wustl.edu/ataxia/aindex.html). However, these classifications do not include several genetic diseases (dominant or recessive) in which ataxia is a prominent accompanying feature to other neurological symptoms.

From Genetic Loci to Genes: The Impact of Advances in DNA Sequencing and Bioinformatics

Until recently, the identification of the specific genetic mutation was a slow and laborious process. It required time-consuming methods that involved sequencing candidate genes in the area of linkage or screening large genomic libraries and looking for partially overlapping DNA segments to “walk” along the chromosome until the mutation was found, a procedure termed positional cloning. This process clearly benefited from newer techniques in compilation of genomic libraries and automation of dideoxy sequencing techniques that was first used by Sanger et al26 in 1977.

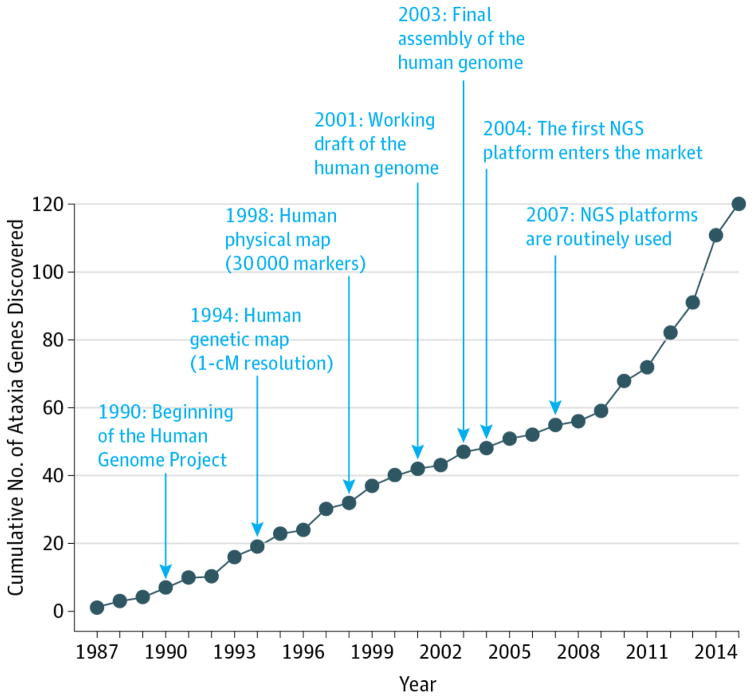

Major advances in sequencing came about with newer technologies inspired by the Human Genome Project (1998). The principle conceptual advance was that computers could be used to reconstruct a full genome after it was sequenced in randomly fragmented bits, taking advantage of their partial overlap (shotgun sequencing). This concept was later adapted to newer sequencing chemistries with the capability to generate millions of short reads in a single run. This way a whole genome could be sequenced in parallel and then reconstructed in silico.27 This approach, now termed next-generation sequencing (NGS), has made positional cloning virtually unnecessary. Indeed, the entire genome from a single affected individual can simply be interrogated and the culprit gene can be identified through comparison with unaffected control individuals. Since NGS technologies entered the market for the first time in 2007, they have gradually replaced Sanger-derived methods and changed the way we identify genes underlying genetic syndromes. Next-generation sequencing has resulted in a dramatic increase in our knowledge of new ataxic genes; the effect of this technology on ataxia genetics has exceeded the contribution of any other milestone discovery in molecular biology (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Technologies and the Discovery Rate for Ataxia Genes.

The graph shows the cumulative number of genes involved in ataxia syndromes that have been identified every year. Milestones in genome research and nucleic acid sequencing are highlighted. Since the introduction of NGS in 2004, the number of genetically characterized ataxias has exponentially grown every year. Before NGS, 27 genes had been identified for autosomal dominant ataxias, 35 genes for recessive ataxias, 4 genes for X-linked ataxias, and 3 genes for mitochondrial ataxias. Since then, NGS has led to the identification of 13 autosomal dominant ataxias, 36 recessive ataxias, and 2 X-linked ataxias.

Three main NGS-based applications currently exist:

Whole-genome sequencing allows detection of possible disease-causing variants along the entire genome, including those variants with regulatory functions located within intergenic and intronic regions. In addition to single-nucleotide variants, whole-genome sequencing also can characterize structural variants such as copy number variations and complex chromosomal rearrangements. Conversely, whole-genome sequencing is the most expensive application.

Whole-exome sequencing can detect disease-causing variants only in the protein-coding regions (1%–2% of the genome) but reaches higher coverage at lower sequencing costs, resulting in superior pick-up performances for rare variants.

Gene-panel sequencing is the most cost-effective application because it targets a roster of selected genes but requires prior knowledge (for instance deriving from preclinical studies) to include the right genes in the panel.

Based on sequence analysis and subsequent studies in cell and model organisms (mainly Drosophila and mice), a few general principles about their molecular basis can now be outlined:

Several of the ataxic syndromes are caused by repeat expansions. The most common expansions are trinucleotide repeats (CAG, CGG, GAA, and CTG), but pentanucleotide or hexanucleotide repeats have been described as well.14,28–30 They can occur in the coding and noncoding regions of the genome. Many translated repeats encode for glutamine residues; thus, culprit proteins generally contain expanded polyglutamine stretches that dramatically alter protein function. However, in some cases, non-canonical translation takes place where multiple toxic products are generated.31,32 With regard to noncoding repeats, several molecular mechanisms have been proposed to explain how these affect gene function. They include heterochromatin induction at the genetic locus33 and pathogenic RNA or protein species production.34

Repeat expansions can be structurally unstable, resulting in longer repeats through generations. Such a phenomenon is termed genetic anticipation and is usually associated with a more severe clinical phenotype in the offspring.35

Mutations in the same gene can produce different diseases, a phenomenon known as genetic pleiotropy. For instance, mutations in the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 1 (ITPR1 [NCBI Entrez Gene 3708]) gene cause SCA15 and SCA29, whereas mutations in the calcium voltage-gated channel subunit α1 A (CACNA1A [NCBI Entrez Gene 773]) gene cause SCA6 and EA2.36–40 Pleiotropy is even extended beyond ataxias because senataxin (SETX [NCBI Entrez Gene 23064]), the causative gene for ataxia with oculomotor apraxia type 2, is also involved in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.41

In general, the recessive ataxias are caused by loss of function of mutated genes, whereas the dominant ataxias are caused by a combination of gain and/or loss of function.

Next-generation sequencing technologies, despite their advantages, are still not perfect in terms of their ability to sequence the genome. Not all the regions of the genome are read with the same coverage as specific genomic portions, such as GC-rich sequences, which can be refractory to polymerase chain reaction amplification. Second, not all the sequenced regions can be mapped with the same accuracy. Indeed, low-complexity sequences (eg, repetitive regions) are difficult to align to the reference genome because the maximum read length of the most common NGS platforms is shorter than the repeated DNA units. Last, NGS data analysis and interpretation can be cumbersome. In fact, typically when the genome of any individual is sequenced, one finds approximately 150 to 500 private mutations (such as nonsynonymous, truncating, or splicing variants).42 Although they affect protein function, these variants— named variants of uncertain significance—are not correlated with any clinical phenotype, further complicating the identification of the real causative mutations. A combination of in silico screenings on large databases of controls and additional sequencing of unaffected parents and/or siblings is necessary to discern whether they are truly causative.43,44 However, the final assessment of the pathogenicity of variants of uncertain significance typically requires wet laboratory follow-up with experiments in cells or model organisms.

Cellular Pathways and Protein Interaction Networks in Ataxias

In the years ahead, we will continue to increase our knowledge of the genetic causes of increasingly rare genetic ataxic syndromes, especially from more experimental work in model organisms. However, we have already reached a point where we can begin to ask some targeted questions that can be addressed by bioinformatics from our knowledge of the genes identified.

Do the Gene Products Define Specific Molecular Pathways?

To gain insight into possible common pathways affected by disease, we have performed a connotation analysis using the molecular function and biological process branches of gene ontology on all the known ataxia genes. We were able to identify a significant enrichment (Bonferroni-corrected P < .05) in genes related to gated ion channels and transmembrane transporters for dominant and X-linked ataxias. The recessive ataxias, on the other hand, are enriched for genes in lipid metabolism and DNA repair. Mitochondrial ataxia genes did not show any particular enrichment, most likely owing to the small sample size (the full gene ontology analysis is included in eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Do the Proteins Mutated in Ataxia Interact With Each Other?

The accumulation of data coming from large-scale proteomic screenings (yeast 2-hybrid coimmunoprecipitation) has recently allowed the creation of interaction networks that have been critical to understand protein functions at the global level.45 Following this systemic approach, Lim et al46 have shown that cerebellar ataxias not only share clinical and pathologic characteristics but also have proteins and pathways in common.

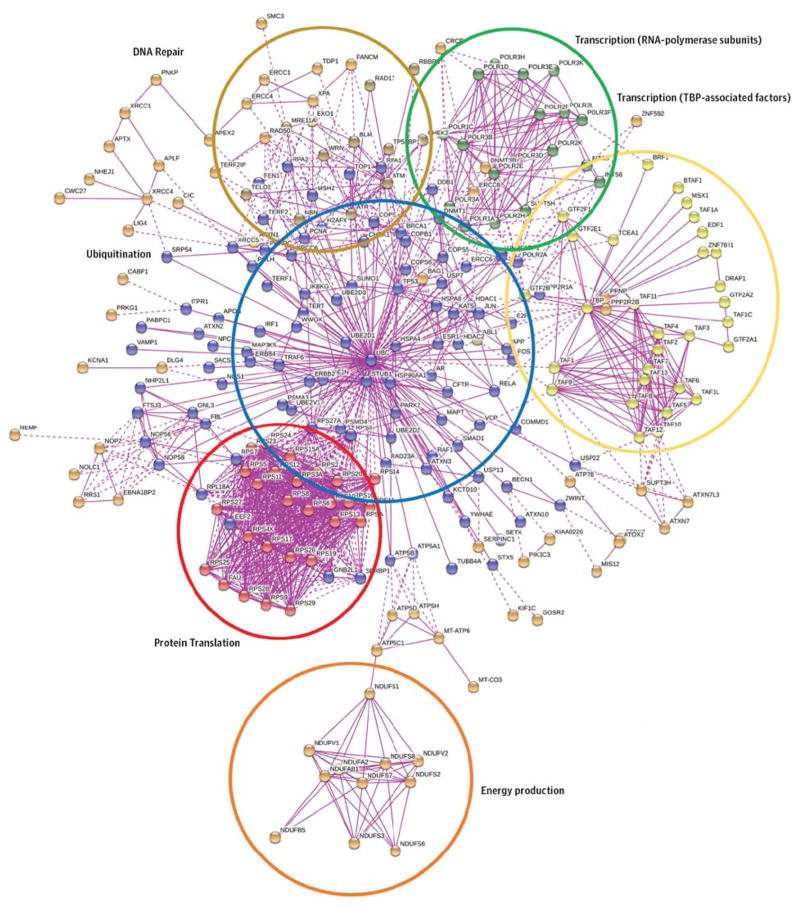

Here we have extended these initial studies that were conducted on 23 inherited ataxias to all the genetically characterized ataxia syndromes. Instead of using just the yeast 2-hybrid system, we opted for a pure in silico approach based on the STRING prediction server—a resource that quantitatively integrates interaction data (physical or functional) for almost 10 million proteins from more than 2000 organisms.47 We built the local protein interaction networks using ataxia genes as seeds, and we could identify 6 main clusters associated to specific cellular functions (Figure 2 and eTable 3 in the Supplement). The first cluster (in blue) is centered on ubiquitin, suggesting the involvement of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in ataxia pathogenesis. Defects in protein degradation are shared by a large group of neuropathologic conditions that are characterized by aggregates of abnormally folded proteins in affected cells.48 These aggregation-prone proteins escape the quality control of the ubiquitin-proteasome system and accumulate within the cytosolic or the nuclear compartments, eventually disrupting cellular homeostasis.

Figure 2. Protein Interaction Network for Human Ataxia Genes.

The STRING prediction server (version 9.1) was used to generate the protein network using all the known genes involved in human ataxia syndromes as seeds. The maximum number of predicted neighbors was set to 1000; experiment was selected as search criteria (to include only the experimentally validated physical interactions), and the maximum stringency was chosen (highest confidence score = 0.900). The following 6 subnetworks can be appreciated, each highlighting a specific cellular process: protein translation (red), ubiquitination (blue), transcription regulation (yellow and green), DNA repair (brown), and energy production (orange). TBP indicates TATA-binding protein. A complete list of protein names and symbols is given in eTable 3 in the Supplement. SCA41 and SCA43 were not included because they were published after the manuscript was accepted.

The second cluster (in red) is enriched in ribosomal proteins, whereas the third (in yellow) and the fourth (in green) clusters involve TATA-binding protein–associated factors and RNA-polymerase subunits, respectively. All of them pinpoint regulation of gene expression as another commonly affected cellular process of disease. Notably, a growing body of experimental evidence has recently pointed out transcriptional dysregulation as an important contributing factor to several neurodegenerative disorders such as Huntington and Alzheimer diseases.49,50

The fifth cluster (in brown) is enriched in enzymes involved in DNA repair and maintenance. Defects in these pathways are commonly associated with aging. Moreover, aging itself is a risk factor for several neurodegenerative diseases.51 Indeed, postmitotic neurons are particularly vulnerable to certain types of DNA damage, and the age-dependent decline in DNA repair mechanism efficiency leads to their accumulation within the neuronal genome, contributing to neurodegeneration.52

The last cluster (in orange) is composed of several subunits of the enzyme complexes in the electron transport chain located in the inner mitochondrial membrane. Thus, the failure in cellular energy production could also be a cause of an ataxic phenotype. In fact, an insufficient production of adenosine triphosphate may impair neuronal functions, such as synaptic transmission, and eventually trigger active forms of cell death. This process could be driven by direct dysfunctions in the respiratory chain—as suggested by our protein networks—or by defective mitochondrial dynamics, as demonstrated in the case of Alzheimer, Parkinson, and Huntington diseases.53–55

In subgroup analyses, dominant ataxias contributed the subnetworks related to protein translation, protein degradation, and TATA-binding protein–associated factors. Recessive ataxias instead contributed the subnetworks associated to RNA-polymerase complex, protein degradation, DNA repair, and energy production. Mitochondrially inherited and X-linked ataxias failed to produce any significant network, possibly owing to the small sample size and the stringent threshold criteria adopted.

Are the Ataxia Interactors Associated With Other Diseases?

To check whether any novel binding partners in the ataxia network are associated with other human disorders, we searched each protein in the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database. Remarkably, 67 of 226 proteins are associated with 1 or more human diseases (eTable 4 in the Supplement). The most represented are hematologic syndromes (causing anemia) and different types of cancer, followed by several neurologic disorders. Within the last group, amyloid-β precursor protein and microtubule-associated protein tau are part of the network—the former involved in familial Alzheimer disease and the latter in frontotemporal dementia, Pick disease, and progressive supranuclear palsy. We also identified in the network the androgen receptor that causes spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy, another polyglutamine disease.

Conclusions

The last few years have seen a clear acceleration in our knowledge of ataxic syndromes, principally driven by our advances in genetic tools and computing power. In 2012, as many as 40% of clinically defined ataxia subtypes were estimated to be still genetically uncharacterized.56 Since then, more than 20 novel ataxia genes have been characterized, and we are now identifying rarer genetic syndromes. Following this trend, future NGS will reasonably become more of a diagnostic tool based on a well-defined panel of genes. The implications and pitfalls of NGS-based diagnostics in routine clinical practice have been recently reviewed elsewhere.57 Once all the ataxia genes are characterized, the next big challenge will be to identify the possible disease modifiers of clinical phenotypes and responsiveness to treatments. Genome-wide association studies ideally should be used to discover all the genetic interactions underlying a particular ataxia phenotype. However, considering that the statistical power of a genome-wide association study depends on the sample size of available cases and controls, multicentric and collaborative studies will be essential to collect an adequate number of patients for these relatively rare disorders.

The volume of data generated by NGS also represents an important resource to gain insight into the molecular basis of neurodegeneration. In this review, with ataxias used as a paradigm, we have shown that almost half of the known ataxia genes that are apparently unrelated belong instead to a large protein interaction network. This evidence has allowed the definition of common cellular processes possibly affected by disease and novel interacting genes that might act as disease modifiers or be involved in those ataxia syndromes still uncharacterized. A functional follow-up in model organisms will help to elucidate the possible role of the most promising candidate genes. More recently, the use of human induced pluripotent cells to generate neurons in a dish is allowing exciting mechanistic studies relevant to the human situation, especially as we move into translational studies geared toward personalized medicine. Cell- and model organism–based studies will also have a broader impact because they are likely to shed insight into the pathophysiologic features of sporadic and acquired ataxias and even other neurodegenerative diseases, given that pathogenic pathways are beginning to overlap. In a way, advances in ataxia research over the years demonstrate vividly that humans are the ultimate model organism for studying human disease from bedside to bench and back again. Just as molecular biology has dominated the world scientific scene in the past 150 years, we anticipate that newer technologies such as genome editing and connectomics will gain center stage for understanding pathophysiologic features and illuminating avenues for therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by grants 1R01 NS062051 and 1R01NS082351 from the National Institutes of Health (Opal Laboratory).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr. Opal reports receiving compensation for medicolegal and ad hoc consulting and royalty payments from UpToDate. No other disclosures were reported.

Author Contributions: Drs Didonna and Opal had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Opal.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Both authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Both authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Both authors.

Obtaining funding: Opal.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Opal.

Study supervision: Opal.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- 1.Yildirim FB, Sarikcioglu L. Marie Jean Pierre Flourens (1794 1867): an extraordinary scientist of his time. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(8):852. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.118380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barboi AC. Cerebellar ataxia. Arch Neurol. 2000;57(10):1525–1527. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.10.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Babinski J. De l’asynergie cérébelleuse. Rev Neurol. 1899;7:806–816. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedreich N. On degenerative atrophy of the spinal dorsal columns [in German] Virchows Arch Pathol Anat Physiol Klin Med. 1863;26:391–419. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marie P. Sur l’heredo-ataxie cerebelleuse: clinique des maladies nerveuses. Semaine Med. 1893;3:444–447. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kinnier Wilson SA. Progressive lenticular degeneration: a familial nervous disease associated with cirrhosis of the liver. Brain. 1912;34(1):295–507. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Syllaba L, Henner K. Contribution a l’independence de l’athetose double idiopathique et congenitale: atteinte familiale, syndrome dystrophique, signe de reseau vasculaire conjonctival, integrite psychique. Rev Neurol. 1926;1:541–562. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harding AE, Matthews S, Jones S, Ellis CJ, Booth IW, Muller DP. Spinocerebellar degeneration associated with a selective defect of vitamin E absorption. N Engl J Med. 1985;313(1):32–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198507043130107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siemerling E, Creutzfeldt HD. Bronzekrankheit und sklerosierende Enzephalomyelitis. Arch Psychiatry. 1923;68:217–244. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Polten A, Fluharty AL, Fluharty CB, Kappler J, von Figura K, Gieselmann V. Molecular basis of different forms of metachromatic leukodystrophy. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(1):18–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101033240104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Bogaert L, Scherer HJ, Froehlich A, Epstein E. Une deuxieme observation de cholesterinose tendineuse symetrique avec symptomes cerebraux. Ann Med. 1937;42:69–101. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenfield JG. The Spinocerebellar Degenerations. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whyte JM. Four cases of Friedreich’s ataxia with a critical digest of recent literature on the subject. Brain. 1898;21:72–137. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Opal P, Zoghbi HY. The spinocerebellar ataxias. [Accessed June 2016];UpToDate website. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/the-spinocerebellar-ataxias. Updated January 7, 2016.

- 15.Jackson JF, Currier RD, Terasaki PI, Morton NE. Spinocerebellar ataxia and HLA linkage: risk prediction by HLA typing. N Engl J Med. 1977;296(20):1138–1141. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197705192962003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Botstein D, White RL, Skolnick M, Davis RW. Construction of a genetic linkage map in man using restriction fragment length polymorphisms. Am J Hum Genet. 1980;32(3):314–331. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hearne CM, Ghosh S, Todd JA. Microsatellites for linkage analysis of genetic traits. Trends Genet. 1992;8(8):288–294. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(92)90256-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olson M, Hood L, Cantor C, Botstein D. A common language for physical mapping of the human genome. Science. 1989;245(4925):1434–1435. doi: 10.1126/science.2781285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang DG, Fan JB, Siao CJ, et al. Large-scale identification, mapping, and genotyping of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the human genome. Science. 1998;280(5366):1077–1082. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5366.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schöls L, Bauer P, Schmidt T, Schulte T, Riess O. Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxias: clinical features, genetics, and pathogenesis. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3(5):291–304. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00737-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.VanDyke DH, Griggs RC, Murphy MJ, Goldstein MN. Hereditary myokymia and periodic ataxia. J Neurol Sci. 1975;25(1):109–118. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(75)90191-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jen JC, Graves TD, Hess EJ, Hanna MG, Griggs RC, Baloh RW CINCH investigators. Primary episodic ataxias: diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 10):2484–2493. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall DA, Jacquemont S. Epidemiology of FXTAS. In: Tassone F, Berry-Kravis E, editors. The Fragile X Associated Tremor/Ataxia Syndrome. New York, NY: Springer; 2010. pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bacalman S, Farzin F, Bourgeois JA, et al. Psychiatric phenotype of the fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS) in males: newly described fronto-subcortical dementia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(1):87–94. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thorburn DR, Rahman S. Mitochondrial DNA-associated Leigh syndrome and NARP. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al., editors. Gene Reviews. Seattle: University of Washington; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson AR. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 1977;74(12):5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Metzker ML. Sequencing technologies: the next generation. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11(1):31–46. doi: 10.1038/nrg2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Opal P, Zoghbi HY. Hereditary ataxias. In: Rimoin DL, Pyeritz RE, Korf B, editors. Emery and Rimoin’s Principles and Practice of Medical Genetics. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2013. pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Opal P, Zoghbi HY. Overview of the hereditary ataxias. [Accessed June 2016];UpToDate website. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-the-hereditary-ataxias. Updated March 9, 2015.

- 30.Opal P, Zoghbi HY. The hereditary ataxias. In: Asbury AK, McKhann GM, McDonald WI, Goadsby PJ, McArthur JC, editors. Diseases of the Nervous System. Vol. 2. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 1880–1895. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pearson CE. Repeat associated non-ATG translation initiation: one DNA, two transcripts, seven reading frames, potentially nine toxic entities! PLoS Genet. 2011;7(3):e1002018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cleary JD, Ranum LP. Repeat-associated non-ATG (RAN) translation in neurological disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22(R1):R45–R51. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sato N, Amino T, Kobayashi K, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 31 is associated with “inserted” penta-nucleotide repeats containing (TGGAA)n. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85(5):544–557. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kobayashi H, Abe K, Matsuura T, et al. Expansion of intronic GGCCTG hexanucleotide repeat in NOP56 causes SCA36, a type of spinocerebellar ataxia accompanied by motor neuron involvement. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89(1):121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koshy BT, Zoghbi HY. The CAG/polyglutamine tract diseases: gene products and molecular pathogenesis. Brain Pathol. 1997;7(3):927–942. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1997.tb00894.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van de Leemput J, Chandran J, Knight MA, et al. Deletion at ITPR1 underlies ataxia in mice and spinocerebellar ataxia 15 in humans. PLoS Genet. 2007;3(6):e108. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iwaki A, Kawano Y, Miura S, et al. Heterozygous deletion of ITPR1, but not SUMF1, in spinocerebellar ataxia type 16. J Med Genet. 2008;45(1):32–35. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.053942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang L, Chardon JW, Carter MT, et al. Missense mutations in ITPR1 cause autosomal dominant congenital nonprogressive spinocerebellar ataxia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:67. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-7-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhuchenko O, Bailey J, Bonnen P, et al. Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia (SCA6) associated with small polyglutamine expansions in the alpha 1A-voltage-dependent calcium channel. Nat Genet. 1997;15(1):62–69. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Riant F, Lescoat C, Vahedi K, et al. Identification of CACNA1A large deletions in four patients with episodic ataxia. Neurogenetics. 2010;11(1):101–106. doi: 10.1007/s10048-009-0208-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen YZ, Bennett CL, Huynh HM, et al. DNA/RNA helicase gene mutations in a form of juvenile amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS4) Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74(6):1128–1135. doi: 10.1086/421054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gilissen C, Hoischen A, Brunner HG, Veltman JA. Disease gene identification strategies for exome sequencing. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20(5):490–497. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7(4):248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xue Y, Chen Y, Ayub Q, et al. 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. Deleterious- and disease-allele prevalence in healthy individuals: insights from current predictions, mutation databases, and population-scale resequencing. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91(6):1022–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rolland T, Taşan M, Charloteaux B, et al. A proteome-scale map of the human interactome network. Cell. 2014;159(5):1212–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lim J, Hao T, Shaw C, et al. A protein-protein interaction network for human inherited ataxias and disorders of Purkinje cell degeneration. Cell. 2006;125(4):801–814. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Franceschini A, Szklarczyk D, Frankild S, et al. STRING v9.1: protein-protein interaction networks, with increased coverage and integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):D808–D815. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hipp MS, Park SH, Hartl FU. Proteostasis impairment in protein-misfolding and -aggregation diseases. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24(9):506–514. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cha JH. Transcriptional dysregulation in Huntington’s disease. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23(9):387–392. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01609-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Robakis NK. An Alzheimer’s disease hypothesis based on transcriptional dysregulation. Amyloid. 2003;10(2):80–85. doi: 10.3109/13506120309041729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jeppesen DK, Bohr VA, Stevnsner T. DNA repair deficiency in neurodegeneration. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;94(2):166–200. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Madabhushi R, Pan L, Tsai LH. DNA damage and its links to neurodegeneration. Neuron. 2014;83(2):266–282. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Poole AC, Thomas RE, Andrews LA, McBride HM, Whitworth AJ, Pallanck LJ. The PINK1/Parkin pathway regulates mitochondrial morphology. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2008;105(5):1638–1643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709336105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang X, Su B, Lee HG, et al. Impaired balance of mitochondrial fission and fusion in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2009;29(28):9090–9103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1357-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Song W, Chen J, Petrilli A, et al. Mutant huntingtin binds the mitochondrial fission GTPase dynamin-related protein-1 and increases its enzymatic activity. Nat Med. 2011;17(3):377–382. doi: 10.1038/nm.2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sailer A, Houlden H. Recent advances in the genetics of cerebellar ataxias. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2012;12(3):227–236. doi: 10.1007/s11910-012-0267-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fogel BL, Satya-Murti S, Cohen BH. Clinical exome sequencing in neurologic disease. Neurol Clin Pract. 2016;6(2):164–176. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.