Abstract

Background

Most studies of the effects of parental religiousness on parenting and child development focus on a particular religion or cultural group, which limits generalizations that can be made about the effects of parental religiousness on family life.

Methods

We assessed associations among parental religiousness, parenting, and childrens adjustment in a 3-year longitudinal investigation of 1198 families from 9 countries. We included 4 religions (Catholicism, Protestantism, Buddhism, Islam) plus unaffiliated parents, 2 positive (efficacy and warmth) and 2 negative (control and rejection) parenting practices, and 2 positive (social competence and school performance) and 2 negative (internalizing and externalizing) child outcomes. Parents and children were informants.

Results

Parents greater religiousness had both positive and negative associations with parenting and child adjustment. Greater parent religiousness when children were 8 was associated with higher parental efficacy at 9 and, in turn, childrens better social competence and school performance and fewer child internalizing and externalizing problems at 10. However, greater parent religiousness at 8 was also associated with more parental control at 9, which in turn was associated with more child internalizing and externalizing problems at 10. Parental warmth and rejection had inconsistent relations with parental religiousness and child outcomes depending on the informant. With a few exceptions, similar patterns of results held for all 4 religions and the unaffiliated, 9 sites, mothers and fathers, girls and boys, and controlling for demographic covariates.

Conclusions

Parents and children agree that parental religiousness is associated with more controlling parenting and, in turn, increased child problem behaviors. However, children see religiousness as related to parental rejection, whereas parents see religiousness as related to parental efficacy and warmth, which have different associations with child functioning. Studying both parent and child views of religiousness and parenting are important to understand effects of parental religiousness on parents and children.

Keywords: Religiousness, parenting, child adjustmen, reporter, religion

… religion and freedom have been causes for the most noble actions and the most evil actions…

– Attributed to Lord Acton (1834–1902)

Introduction

Religion, religiousness, and family life are tightly braided. This study examines the nature of their weave. Although it does not submit to easy definition, a religion is generally thought of as an organized socio-cultural-historical system of beliefs that relate people to an order of existence and often to a supreme being. Religion is ‘the search [discovery, conservation, and transformation; Pargament, 2007] for significance that occurs within the context of established institutions that are designed to facilitate spirituality’ (Pargament, Mahoney, Exline, Jones, & Shafranske, 2013, p. 15). Religion and religious institutions assert norms about the ‘destinations and pathways’ that adherents should follow to fulfill sacred ideals about all aspects of life that submit divine character and significance (Mahoney, Pargament, & Hernandez, 2013; Pargament & Mahoney, 2005) and so extend to family relationships. Religion is content, religiousness is a measure of a persons adherence and involvement with a religion. Religiousness also overlaps but differs from spirituality (Mahoney, 2013; Pargament et al., 2013): Religiousness refers to the extent an individual has a relation with a particular belief system (and is measured by, e.g., subjective feelings of importance or objective attendance at religious services), whereas spirituality refers to individualized, experiential positive values such as connectedness, meaning, self-actualization, and authenticity that define the personal quest for understanding answers to ultimate questions about life (and is measured by, e.g., perceptions of transcendence). Religiousness and spirituality alike are multidimensional constructs, composed of feelings and thoughts, actions and relationships (Pargament et al., 2013).

Worldwide, 86% of people claim to identify with a particular religion, and 59% of the worlds population self-identifies as religious (WIN-Gallup International, 2012). Religious writings, the common source of religions, give rise to norms, beliefs, and values about, as well as prescriptions and proscriptions for, living (Browning, Green, & Witte, 2006; Parrinder, 1996). Religion, religiousness, and spirituality are demonstrably powerful forces for most of the worlds population and are associated with everyday family functioning, childrearing, and child adjustment (Beit-Hallachmi, 1984; Holden & Vittrup, 2010; Pargament, Exline, & Jones, 2013). In light of their global pervasiveness in contemporary life, it is perplexing and dismaying that religion, religiousness, and spirituality are largely neglected in developmental science as contexts of development. Moreover, the extant literaure has been dominated by U.S. samples and skewed by Western assumptions (King & Boyatzis, 2015; Pargament et al., 2013). For example, traditional religious doctrines idealize U.S. American, middle-class, married heterosexuals rearing biological children as ‘the good family’ (Edgell, 2005).

For all these reasons, the present study of associations of parental religiousness with parenting and child adjustment takes a longitudinal, multi-religion, and cross-national approach. This study focuses principally on parental religiousness and religion (contra religious content and spirituality) and the roles of parental religiousness in positive and negative parenting and child adjustment. To gain broad purchase on religiousness and parenting, the study includes mothers and fathers from 4 religions as well as non-adherents and from 9 countries. The psychology of religion (and spirituality) has also tended to focus on positive and negative roles that faith plays in the health and well-being of individuals, rather than relationships (Hood, Hill, & Spilka, 2009; Koenig, McCullough, & Larson, 2001; Paloutzian & Park, 2005). This study focuses on parent and child together.

Parental religiousness, parenting, and child adjustment

Parents who are more religious are more likely to manifest their religious values and beliefs through everyday interactions with others, including their children. An emerging research literature demonstrates that religiousness does not have monolithic effects, however. ‘The psychology of religion and spirituality makes very clear that these phenomena are multivalent; they can be helpful, but they also can be harmful’ (Pargament et al., 2013, p. 7). That is, each process can express itself in constructive and destructive ways. On the one hand, greater religious attendance and overall salience of religion tends to be tied to the formation of traditional family bonds and the maintenance of traditional or nontraditional family ties, and higher religious attendance and importance of religion stabilize marriage (Mahoney, 2010; Mahoney, Pargament, Swank, & Tarakeshwar, 2001). Frequency of worship attendance by mothers and fathers (separately and together) is associated with positive and adaptive parenting, favorable attitudes toward parenting, expressed warmth, and positive relationships with children (Bartkowski, Xu, & Levin, 2008; DeMaris, Mahoney, & Pargament, 2011; Dollahite, 1998; Duriez, Soenens, Neyrinck, & Vansteenkiste, 2009; Hill, Burdette, Regnerus, & Angel, 2008; King & Furrow, 2004; Park & Bonner, 2008; Pearce & Axinn, 1998). A meta-analysis (of largely U.S. and exclusively Western samples) revealed that religiousness relates to crucial positive manifestations in parenting, including authoritativeness, with subsequent benefits for children (Mahoney, Pargament, Tarakeshwar, & Swank, 2008; see also Snider, Clements, & Vazsonyi, 2004). Religious beliefs and practices (in the United States) have largely positive implications for health and well-being (Koenig, King, & Carson 2012), and more broadly religious groups sponsor movements for peace, reconciliation, and social justice (Silberman, Higgins, & Dweck, 2005) and religion is strongly associated with virtues (gratitude, forginess, altruism; Carlisle & Tsang, 2013; Saroglou, 2013). Together, these findings point to potential profits of parent religiousness for different types of favorable outcomes in parenting and child adjustment.

On the other hand, parental religiousness is not always conducive to thriving and can cause harm to individuals (abuse, violence; Fallot & Blanch, 2013; Jones, 2013) as it can cause individuals to do harm (discrimination, prejudice; Doehring, 2013). Parental religiousness has been hypothesized to engender less flexible caregiving because fixed factors, such as religious dogma, rather than variable factors, such as a childs needs or the situation, would help to determine parenting. Higher religious attendance and more literal Bible interpretation, for example, are associated with higher parenting stress and risk of child abuse (Rodriguez & Henderson, 2010; Weyand, OLaughlin, & Bennett, 2013). As many religions require beliefs and traditions that, from a scientific view, are illogical or unreasonable, greater religiousness may also undermine rational parenting and so child adjustment (Bottoms, Shaver, Goodman, & Qin, 1995; Templeton & Eccles, 2006). More broadly, some religious factions are known to promote intergroup conflict and even terrorism and genocide (Waller, 2013)

In the same way that religiousness has complex and nuanced relations with parenting, it is associated in complicated and subtle ways with diverse child outcomes (Koenig et al., 2001; Pargament, 1997). Some studies report positive effects of parental religiousness on children, but others find negative effects (for a review see Holden & Williamson, 2014). For example, parental religiousness is associated with higher levels of desirable outcomes in children (self-control, social skills) and lower levels of undesirable outcomes (internalizing and externalizing problems), as rated by parents and teachers (Bartkowski et al., 2008; DeMaris et al., 2011; Dollahite, 1998; King & Furrow, 2004; McCullough & Willoughby, 2009; Smith & Denton, 2005). However, adolescence is a time of identity struggles (King, Ramos, & Clardy, 2013), and discrepancy in parent-adolescent religiousness is associated with adolescent behavior problems (Kim-Spoon, Longo, & McCollough, 2012) and poorer parent-child relationship quality (Stokes & Regnerus, 2009).

Existing research therefore demonstrates benefits of parental religiousness as well as detriments. Religiousness appears to embody both the ‘noble’ and the ‘evil,’ the paradox that Lord Acton observed. History records that religiousness promotes love, transcendence, and connectedness but also inspires intolerance, animosity, and violence (Oser, Scarlett, & Bucher, 2006). Religiousness is therefore as much a force for peace and understanding as for conflict and prejudice on the world stage, and this duality appears to play out on the family stage. Together, the good and bad underscore the potency of parental religiousness for children, parents, and society. Marks (2004) interviewed Christian, Jewish, Mormon, and Muslim parents of children ages 5 to 13 years. Parents reported that their religiousness promoted family connectedness and closeness but also constituted a source of conflict within the family and with the larger community. A comprehensive understanding of parental religiousness, parenting practices, and child adjustment therefore requires appreciation of the positive as well as the negative effects of parental religiousness in the family. On this account, we studied parental religiousness and its connections to 2 positive and 2 negative aspects of parenting and to 2 positive and 2 negative outcomes in children.

In the same global poll that counted nearly 60% of the world population as religious, nearly 40% claimed to be unaffiliated. Religious affiliated and unaffiliated parents may hold different caregiving values, allocate time and effort in caregiving differently, and involve their children in social networks associated with different (religious vs. nonreligious) communities; not unexpectedly, some developmental trajectories are thought to differ for children from religious and nonreligious homes (Evans, 2000; Streib & Klein, 2013; Wilcox, 2002). Compared with children reared in nonreligious households, children in religious homes have been reported to be better adjusted socially and emotionally, have higher self-esteem and social responsibility, and show lower levels of internalizing and externalizing behavior problems (Bartkowski et al., 2008; Brody, Stoneman, & Flor, 1996; Gunnoe, Hetherington, & Reiss, 1999; King & Furrow, 2004; Regnerus & Elder, 2003). However, recent research has suggested that children from nonreligious households may hold more prosocial and egalitarian views than children from religious households (Decety et al., 2015; Hall, Matz, & Wood, 2010). For these reasons, we included unaffiliated as well as religion-affiliated parents in this investigation.

The present study

This omnibus study analyzes parental religiousness in longitudinal relation to multiple child- and parent-reported positive and negative parent practices and subsequent positive and negative child adjustment outcomes. The data derive from multiple informants from multiple religions in multiple global regions. The dearth of longitudinal research in this field has precluded stronger inferences about the long-term effects of parental religiousness on parenting and child adjustment. We also considered some key moderators of associations among parental religiousness, parenting, and child adjustment. Gender is one. Smith and Denton (2005) reported that, compared to adolescent boys, adolescent girls aged 13–17 years were more likely to attend religious services, see religion as shaping their daily lives, have made a personal commitment to God, be involved in religious youth groups, and pray when alone. Generally, higher proportions of females than males report that religion is very important in their lives (Child Trends, 2013). Therefore, we conducted separate comparative analyses for mothers and fathers as well as for girls and boys. Reporter is another potential moderator, as childrens and parents reports may have different relations to parent religiousness and child adjustment (King & Boyatzis, 2015), and so we assessed child and parent reports of parenting in separate models. Finally, research has rarely studied whether religiousness has unique associations with parenting and child adjustment after accounting for common-cause third variables. We therefore took parental education, age, and social desirability of responding into statistical account.

These considerations together guided four main hypotheses. Because parental religiousness can shape parenting decisions, we expected that (1) greater parental religiousness would lead to greater parental efficacy that would lead to greater child social competence and school performance and lesser internalizing and externalizing child problems. Because the major religions we studied recommend appropriate care and rearing of children, we expected that (2) greater parental religiousness would lead to greater parental warmth that would lead to greater child social competence and school performance and less internalizing and externalizing child problems. Because the major religions we studied generally prescribe obedience and control for children, we expected that (3) greater parental religiousness would also lead to greater parental control that would lead to more internalizing and externalizing problems and lower social competence and school performance in children. Although parental control can have both positive and negative effects on children (Van Der Bruggen, Stams, & Bögels, 2008), we hypothesized that higher parental control would be associated with worse outcomes in this study because behavioral control is perceived negatively by children (Kakihara & Tilton-Weaver, 2009). (4) We had no particular hypotheses about the link between parental religiousness and parental rejection. Although high parental religiousness may lead to less rejection of children for the same reasons we hypothesized a positive link between parental religiousness and warmth, some children may perceive parents with high levels of religiousness as more rejecting if, for example, the parents concern for his or her religious beliefs supersedes concern for the child. Finally, based on the very limited evidence about moderators of these relations, we expected that (5) the links found between parental religiousness, parenting, and child adjustment would be largely invariant across religious groups, sites, parent gender, and child gender.

Method

Sample

Altogether, 1198 families (1198 children, 1198 mothers, and 1075 fathers; N=3471) from 9 countries provided data over 3 years. Families were drawn from Jinan, China (ns=118 mothers and 118 fathers), Medellín, Colombia (ns=102 mothers and 99 fathers), Naples and Rome, Italy (ns=196 mothers and 182 fathers), Zarqa, Jordan (ns=111 mothers and 108 fathers), Kisumu, Kenya (ns=98 mothers and 98 fathers), Manila, the Philippines (ns=101 mothers and 88 fathers), Trollhättan/Vänersborg, Sweden (ns=96 mothers and 81 fathers), Chiang Mai, Thailand (ns=116 mothers and 105 fathers), and Durham, North Carolina, United States (ns=260 mothers and 196 fathers). Children (50.6% female) averaged 8.25 years (SD=.63) in wave 1, 9.31 years (SD=.73) in wave 2, and 10.34 years (SD=.71) in wave 3 of the study. Late childhood is a critical phase of development for academic achievement, social competence, and behavioral adjustment, and so we studied parental religiousness in connection with positive and negative developmental outcomes as children moved through middle childhood. Mothers averaged 37.01 years (SD=6.42) and fathers 40.17 years of age (SD=6.67) in wave 1. Mothers had completed 12.49 years (SD=4.12) and fathers 12.67 years of education (SD=4.13) on average. Mothers reported that 81.53% were married, 9.36% were unmarried and cohabitating, and 9.11% were unpartnered. Furthermore, 31% of children lived in households with three or more adults (e.g., non-nuclear families). Mothers or fathers identified their family as Catholic (37.98%), Protestant (24.37%), Buddhist (10.85%), Muslim (9.68%), and of no religious affiliation (17.11%).

Procedures

Parents provided informed consent, and the study was approved by IRBs at collaborating universities in each country. Families were recruited from schools that served socioeconomically diverse populations in each participating community. At age 8, parents reported on demographic information about the family, religiousness, and religious affiliation. At age 9, children completed questionnaires about their perceptions of their mothers and fathers parenting behavior, and parents completed questionnaires about their parenting behavior, parental efficacy, social desirability bias, and their childs social competence, school performance, and behavior problems. At age 10, parents completed questionnaires about their childs social competence, school performance, and behavior problems. Internal consistencies (α) of scales are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and internal consistencies of mother and father religiousness, parenting, and child adjustment scales

| Mothers | Fathers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| α | M | SD | α | M | SD | |

| Age 8 | ||||||

| Parental religiousness (1–5) | .83a | 3.84 | 1.37 | .83a | 3.84 | 1.37 |

| Age 9 | ||||||

| Child Report | ||||||

| Warmth (1–4) | .80 | 3.58 | .49 | .82 | 3.50 | .53 |

| Control (1–4) | .46 | 3.00 | .58 | .50 | 2.86 | .63 |

| Rejection (1–4) | .81 | 1.39 | .39 | .82 | 1.38 | .38 |

| Parent Report | ||||||

| Efficacy (1–5) | .73 | 4.00 | .65 | .76 | 3.91 | .67 |

| Warmth (1–4) | .78 | 3.67 | .41 | .79 | 3.54 | .48 |

| Control (1–4) | .52 | 2.96 | .57 | .50 | 2.87 | .56 |

| Rejection (1–4) | .80 | 1.34 | .32 | .81 | 1.35 | .32 |

| Social Competence (1–5) | .89 | 3.67 | .68 | .87 | 3.61 | .62 |

| School Performance (1–4) | .82 | 3.37 | .50 | .83 | 3.35 | .51 |

| Internalizing (0–62) | .87 | 9.04 | 7.26 | .86 | 8.10 | 6.43 |

| Externalizing (0–66) | .88 | 9.83 | 7.50 | .85 | 9.21 | 6.38 |

| Age 10 | ||||||

| Social Competence (1–5) | .89 | 3.70 | .69 | .90 | 3.65 | .67 |

| School Performance (1–4) | .82 | 3.36 | .50 | .84 | 3.38 | .51 |

| Internalizing (0–62) | .87 | 8.84 | 7.02 | .84 | 7.83 | 6.11 |

| Externalizing (0–66) | .88 | 9.30 | 7.23 | .86 | 8.80 | 6.62 |

Note. Numbers in parentheses are potential ranges for the scales.

Pearsons correlation between 2 items.

Measures

Family religion and parental religiousness

One parent in the family indicated the familys religious affiliation among the following categories: Catholic, Protestant, Jewish, Buddhist, Hindu, Muslim, and No religious affiliation. The same parent answered two religiousness questions on a scale from 1, not at all, to 5, very important/much: ‘How important would you say religion is in your life?’ and ‘How much would you say your religious beliefs influence your parenting?’ According to Mahoney (2013), upwards of 80% of quantitative studies on faith and family rely on one- or two-item measures of a parents religious affiliation, frequency of worship attendance, self-reported salience of religion in daily life, and the like (Mahoney et al., 2001). These two items were highly correlated, r(1172)=.83, p<.001, and so averaged to form a scale of parental religiousness. Additional information about parental religion and religiousness is available in Appendis S1, available online.

Parenting behavior

The child and parent versions of the Parental Acceptance-Rejection/Control Questionnaire-Short Form (PARQ/Control-SF; Rohner, 2005) were used to measure the reported frequency of mothers and fathers parenting behaviors. Children rated items for each parent, and parents self-rated their own behaviors on a (modified) scale: 1=never or almost never, 2=once a month, 3=once a week, or 4=every day. We used the 8-item warmth-affection scale, 5-item control scale, and 16-item rejection scale (computed as the average of 6 hostility-aggression, 4 rejection, and 6 neglect-indifference items). The control scale reflected behavioral control (rather than psychological control), and a high score indicated high control with little allowance for child autonomy (see Appendix S1). Two example items are ‘My mother lets me do anything I want to do.’ and ‘My mother sees to it that I know exactly what I may or may not do.’

Parental efficacy

Mothers and fathers self-reported their feelings of parental efficacy (Bandura, Barbaranelli, Caprara, & Pastorelli, 2001) on 4 items about how much they can do to affect their children at school, at home, and outside the home. Items like ‘How much can you do to get your children to do things you want at home?’ and ‘How much can you do to help your children to work hard at their school work?’ were rated on a 5-point scale from 1, Nothing, to 5, A great deal. Mother- and father-rated scales were each computed as the average of 4 items.

Child social competence

Mothers and fathers completed a 7-item social competence scale (Pettit, Harrist, Bates, & Dodge, 1991) indicating how socially skilled the child was in several kinds of interpersonal interactions (understanding others feelings, generating good solutions to interpersonal problems). Items were rated on a 5-point scale from 1=very poor to 5=very good. Mother- and father-rated scales were each computed as the average of the 7 items.

Child school performance

Mothers and fathers rated their childs school performance in reading, math, social studies, and science, four areas that are common to curricula in every country. The questions were adapted from the performance in academic subjects section of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991) that has demonstrated criterion validity. Parents rated whether children were 1=failing, 2=below average, 3=average, or 4=above average in each area. Mother- and father-rated scales were each computed as the average of the 4 items.

Child internalizing and externalizing behavior

Mothers and fathers completed problem items on the widely used and validated CBCL. We used raw scores of the mother- and father-rated 33-item externalizing scales (e.g., ‘My child gets in many fights.’) and 31-item internalizing scales (e.g., ‘My child is too fearful or anxious.’). Mothers and fathers indicated whether each behavior was 0=Not true, 1=somewhat or sometimes true, or 2=very true or often true.

Moderators/covariates

In addition to parent and child gender, we evaluated religious group (five categories) and data collection site (9 categories) as moderators. We also evaluated three covariates: parental education, age, and social desirability bias. People with less education tend to place more emphasis on teaching children religious faith than people with more education (Doherty, Funk, Kiley, & Weisel, 2014), and higher parental education is associated with better parenting and child adjustment (Smith, Perou, & Lesesne, 2002). A single respondent from the household (88.3% mothers) reported both mothers and fathers years of education. Because parent age is known to relate to their parenting and child adjustment (Bornstein & Putnick, 2007; Bornstein, Putnick, Suwalsky, & Gini, 2006), parental age in years was used as a covariate. As a control variable when evaluating parent-report measures, mothers and fathers completed the 13-item Social Desirability Scale-Short Form (SDS-SF; Reynolds, 1982) to assess social desirability bias. Statements such as ‘Im always willing to admit when I make a mistake.’ were rated as True or False. α of the SDS-SF is .76, and the correlation with the full-length SDS .93 (Reynolds, 1982). The SDS-SF has demonstrated concurrent cross-cultural validity (Bornstein et al., 2015).

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations

Table 1 displays descriptive statistics separately for mothers and fathers. Parents reported moderately high levels of parental religiousness, on average, but parental religiousness spanned the full possible range of the scale. Both children and parents rated parental warmth high, rejection low, and control moderate. Parental efficacy was rated as moderately high. Child adjustment varied widely. Correlations among mother and among father scales as well as correlations between matching mother and father scales appear in Table S1.

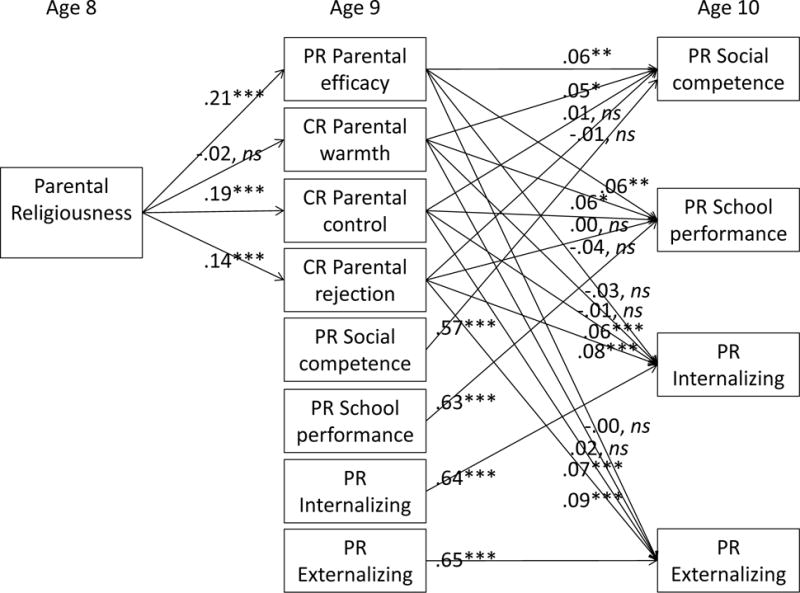

Parental religiousness, child-reported parenting, and change in child adjustment

We fit a developmental path analysis model with relations from age-8 parental religiousness to age-9 child-reported parenting (efficacy, warmth, control, and rejection) and from age-9 parenting to age-10 child adjustment (social competence, school performance, internalizing, and externalizing), controlling for stability in child adjustment from ages 9 to 10. All measures were allowed to covary within waves. The a priori model (Figure 1) fit the data, Satorra-Bentler (S-B) χ2(16)=139.32, p<.001, CFI=.98, RMSEA=.058, 90%CI=.050–.067, SRMR=.03. Greater parental religiousness at age 8 was associated with higher parent-reported parental efficacy at age 9, which was in turn associated with increases in child social competence and school performance from age 9 to age 10. Greater parental religiousness at age 8 was also associated with higher child-reported parental control and rejection at age 9, which were, in turn, related to increases in child internalizing and externalizing from age 9 to age 10. All effect sizes were small.

Figure 1.

Final model of relations of parental religiousness with child report of perceived parenting and parent report of child adjustment across 9 countries, controlling for stability in child adjustment and within-wave relations between parenting and child adjustment (not shown).

Note. CR=Child report. PR=parent report. Standardized coefficients are presented. For ease of interpretation, within-wave covariances are not depicted on the Figure. Covariances among age 9 variables ranged from |r|=.03 to .53, ps=.18 to <.001, and among age 10 variables from |r|=.08 to .53, ps = .002 to <.001.

* p<.05. ** p<.01. *** p<.001.

The indirect effects (computed as the product of path coefficients; Muthén, 2011) of parental religiousness to child social competence and school performance through parental efficacy were positive and significant but small, β=.01, 95% CI=.005–.02, p=.005, and β=.01, 95% CI=.005–.02, p=.007, respectively. The total standardized indirect effects of parental religiousness on child internalizing and externalizing (through rejection and control) were β=.02, 95% CI=.01–.03, p=.002, and .02, 95% CI=.01–.03, p<.001, respectively.

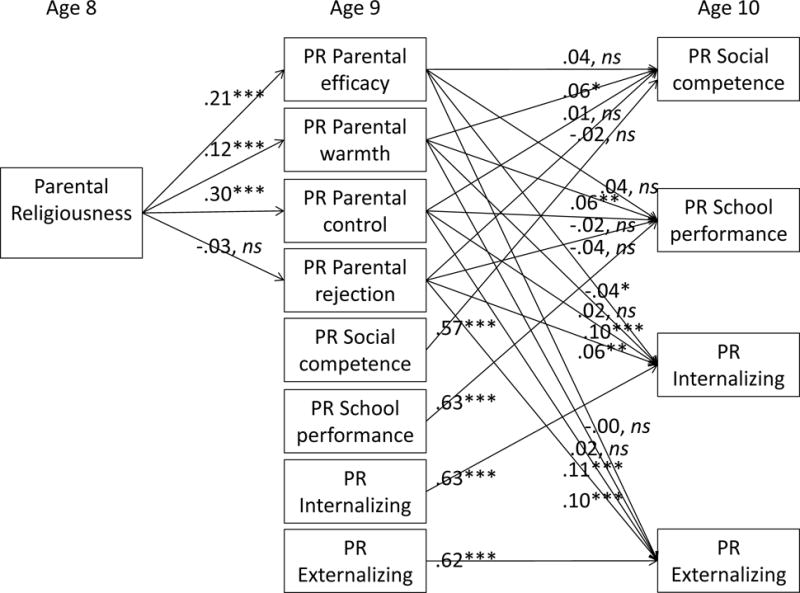

Parental religiousness, parent-reported parenting, and child adjustment

We fit the same a priori developmental model for the parent-reported parenting scales. This model fit the data, S-B χ2(16)=125.63, p<.001, CFI=.98, RMSEA=.056, 90%CI=.047–.065, SRMR=.03. Greater parental religiousness at age 8 was associated with higher parent-reported parental efficacy and warmth at age 9, and parental warmth (but not efficacy) was, in turn, related to increased child social competence and school performance from ages 9 to 10. Higher parent-reported parental efficacy (but not warmth) was also associated with decreased child internalizing problems from ages 9 to 10. Greater parental religiousness at age 8 was associated with higher parent-reported parental control at age 9, which was, in turn, related to increased child internalizing and externalizing from ages 9 to 10. All effect sizes were small.

The indirect effects of parent religiousness on child social competence and school performance through parental warmth were significant but small, β=.01, 95% CI= .001–.013, p=.037, and β=.01, 95% CI= .002–.013, p=.020. The standardized indirect effects of parent religiousness on child internalizing and externalizing (through parental control) were both, β=.03, 95% CI=.02–.04, p<.001.

Covariate controlled models of parental religiousness with parenting and child adjustment

To determine whether the relations in Figures 1 and 2 are accounted for by age 8 parental education, age, and social desirability bias, we residualized all observed variables in the model for significant associations with parental education and age, we residualized parent-report variables for significant associations with social desirability, and we re-calculated the final models. Both covariate controlled models had adequate fit to the data. All significant structural paths depicted in Figures 1 and 2 remained significant in the covariate-controlled models.

Figure 2.

Final model of relations of parental religiousness with parent report of perceived parenting and parent report of child adjustment across 9 countries, controlling for stability in child adjustment and within-wave relations between parenting and child adjustment (not shown).

Note. CR=Child report. PR=parent report. Standardized coefficients are presented. For ease of interpretation, within-wave covariances are not depicted on the Figure. Covariances among age 9 variables ranged from |r|=.02 to .54, ps=.29 to <.001, and among age 10 variables from |r|=.08 to .53, ps = .002 to <.001.

* p<.05. ** p<.01. *** p<.001.

Multiple-group models of parental religiousness with parenting and child adjustment by religious group, site, parent gender, and child gender

It could be that a single religion, site, or group accounts for the findings in the models above. By testing multiple-groups models, we show whether the effects are broadly generalizable or circumscribed to a subset of groups. Multiple-group models were tested across the 5 religious groups, 9 sites, mothers and fathers, and child genders to determine whether the models fit for each group. With the exception of a few structural paths in each model (1–5% of paths), the final models in Figures 1 and 2 fit for families across 5 religious groups: Catholic (n=870), Protestant (n=535), Buddhist (n=249), Muslim (n=229), and no religious affiliation (n=390). With the exception of a few paths in each model, the final models in Figures 1 and 2 fit for parents across the 9 sites: China (n=236), Colombia (n=201), Italy (n=355), Jordan (n=219), Kenya (n=195), Philippines (n=181), Sweden (n=167), Thailand (n=209), and the United States (n=433). Looking across multiple-group models, one path emerged as consistently different – the path between parental religiousness and parental efficacy seemed to be carried by Italian Catholics as it was positive and significant only for Catholics in religious group models and only for Italians in site models. The final models in Figures 1 and 2 fit equally well for mothers (n=1198) and fathers (n=1075) and for girls (n=1147) and boys (n=1126). (Model details, fit statistics, and minor exceptions appear in Appendix S1.)

Discussion

We focused on parental religiousness and its associations with parenting and child adjustment. As researchers in the psychology of religion seldom employ developmental approaches, we utilized a longitudinal design to model temporal pathways from parent religiousness to parenting and child adjustment. By including 4 religions and unaffiliated parents in this ominubus 9-site 3-wave longitudinal multi-reporter research design with 2 positive and 2 negative domains each of parenting and of child adjustment, we reached for a broader understanding of the constructive and destructive roles of religiousness in parenting as well as childrens adjustment. Parents religiousness proved to have associations with positive (efficacy and warmth) and negative (control and rejection) parenting practices and through them associations with positive (social competence and school performance) and negative (internalizing and externalizing) child adjustment. With these several pathways identified, society, religious institutions and leaders, and parents can be vigilant to the differential effects of parental religiousness and labor to promote positive (e.g., by emphasizing efficacy and warmth), and inhibit negative (e.g., by minimizing maladaptive control and rejection), associations of parental religiousness with parenting and with child adjustment.

Our findings of positive and negative associations of parents religiousness with parenting and child adjustment are consistent with past piecemeal studies showing the ‘multivalent’ nature of parental religiousness. In accord with our first hypothesis, greater parental religiousness at age 8 was associated with higher parental efficacy at age 9 and in turn increases in childrens social competence and school performance at age 10. In partial accord with our second hypothesis, greater parental religiousness at age 8 was associated with higher parent-reported parental warmth at age 9, and parent-reported warmth was associated with increased child social competence and school performance (but not fewer internalizing and externalizing problems) at age 10. Parents report that their religiousness and self-rated warmth are associated, but their children do not. What may explain these positive patterns of association? Parental religiousness is associated with more effective parenting, communication, closeness, warmth, support, and monitoring and less authoritarian parenting (Snider, Clements, & Vazsonyi, 2004; Wilcox, 1998). More religious parents may also enjoy stronger and broader parenting supports, and attending worship services regularly might provide stability and community for children. Parental religiousness may emphasize the family, promote moral values, or teach self-regulation (Hood, Spilka, Hunsberger, & Gorsuch, 1996; Mahoney et al., 2008; McCullough & Willoughby, 2009). For example, ‘sanctification,’ viewing God in relationships with other family members, is nondenominational, and sanctification in parenting may be a way religion is embedded in everyday interactions between parents and children (Mahoney et al., 1999). Sanctification is associated with constructive discipline practices and diminished conflict with children (Mahoney et al., 1999; Volling, Mahoney, & Rauer, 2009).

However, in accord with our third hypothesis, parents greater religiousness at age 8 was also associated with more child- and parent-reported parental control at age 9, which in turn was associated with increased child internalizing and externalizing problems at age 10. Although we had no specific a priori hypotheses about parental rejection, parental religiousness was associated with child- (but not parent-) reported parental rejection, which in turn was associated with increases in child internalizing and externalizing problems at age 10. What may explain these negative patterns of association? Religious adherents with stronger affiliations are more likely to prioritize obedience and being well mannered and somewhat less likely to value tolerance, and stronger parental religiousness is related to lower convergence between mothers beliefs about an ideal mother and the profile of the prototypically sensitive mother (Emmen, Malda, Mesman, Ekmekci, & van IJzendoorn, 2012). Parental religiousness can be a source of conflict in the home, and it can undermine child development by increasing childrens stress and anxiety. If parental religiousness is a source of family struggle (Exline, 2013), it may erode self-esteem and generate depression (Dein, 2013). It is possible that more fervent parental religiousness comes across as controlling to older children and emerging adolescents who are forming individualized identities and belief systems. Parental behavioral control is sometimes linked to more positive child outcomes (e.g., Barber, Olson, & Shagle, 1994), but in this study the control scale represented strong behavioral control with little opportunity for autonomy, which older children likely find restrictive. When adolescents report being less religious than their parents, they manifest more behavior problems (Kim-Spoon et al., 2012). We hasten to add here that higher scores on the internalizing and externalizing scales we used should not (necessarily) be interpreted to mean that higher parental religiousness translates into clinically significant levels of emotional or behavioral problems in children. The mean scores on the two CBCL subscales fall below cut points of clinical significance.

With respect to our last hypothesis, we explored whether religious group (qua content), site, parent gender, and child gender moderate relations of parental religiousness on parenting and child adjustment. Similar patterns of results held for all 4 religions and the unaffiliated, all 9 sites, mothers and fathers, girls and boys, and controlling for multiple covariates. These broadly generalizable findings strongly suggest that parental religiousness (and not any religious affiliation in particular) is driving the results. That said, a few religion-specific and site-specific effects arose (see Appendix S1). Notably, the link between parental religiousness and parental efficacy was significant only for Italians (relative to other sites) and Catholics (relative to other religions). Hence, among Italian Catholics, having a strong religious influence may make parents feel more efficacious because religion provides guiding principles about caregiving.

Limitations point to future directions

Overall, greater parental religiousness appears to promote parental efficacy and warmth (as perceived by the parent) that then facilitate two highly valued child outcomes. At the same time, greater parental religiousness appears to augment parental control and rejection (as perceived by the child) that increases parents reports of childrens problem behaviors. Religiousness is a bivocal factor in parenting and child adjustment. As religiousness is multidimensional (Pargament et al., 2013), future research might be designed to uncover which constituents of parental religiousness are associated with which aspects of parenting and child adjustment (Bornstein, 2105b). What does parental religiousness convey, what are the ‘active ingredients’ in religiousness vis-à-vis parenting and child adjustment, are they the same, etc.? Mahoneys (2013) conceptual framework of ‘relational spirituality’ spells out three possible tiers of mechanisms (relationship with God, family relationship, relationship with religious community). Other limitations point to additional research questions. Too frequently studies of religion and religiousness overlook personal meanings (Mahoney, 2010; Mahoney et al., 1999; Volling et al., 2009). In ongoing research with these samples, we are further exploring the impact of the childs own emerging religiousness as well as how parental religiousness interacts with child religiousness. It is debatable whether the slightly higher internalizing symptoms reported by parents here constitute altogether ‘negative’ outcomes. It could be that more religious parents instill negative feelings (e.g., anxiety, guilt) or rebelliousness toward authority figures. Future research should investigate direct and mediated pathways of influence between parental involvement in religious communities and specific spiritual mechanisms that may help or harm family relationships. For example, spirituality could help parents balance warmth versus control, firmness versus flexibility, in family interactions.

Many studies of religiousness (like ours) rely on self-reports. Future work could employ supplementary measures, such as direct observations of parents and children engaging in shared religious practices or when debating religious issues. Furthermore, the internal consistency of the control scales was modest in this study. Although there was adequate evidence of convergent validity, as indicated by relations of parental control with parental religiousness and child functioning, scales with more items and/or stronger reliability might further stabilize future findings. It has been observed that ‘religion and culture … combine together to make the person that you really are’ (McEvoy et al., 2005, p. 146). Culture and religion are intertwined (Lowenthal, 2013; Sander, 1996), as religions and religious practices reflect myriad geographical, historical, national, and ethnic influences and are thus deeply cultural in nature, so separating the respective influences of religion and culture is challenging (Fitzgerald, 2000; Masuzawa, 2005; Mattis, Ahluwalia, Cowie, & Kirkland-Harris, 2006; Prentiss, 2003). Given that religions have been a central part of cultures for millennia, religious ideologies are blended with culture. We did not and could not separate them here. Longitudinal data approach causal analysis because they have a clear temporal order—a necessary, although not sufficient, precondition for identifying causality. Longitudinal data are much more powerful in testing developmental theories than, say, cross-sectional data, but are not definitive. Here, we also relied on a blunt (2-item) measure of religiousness; more attention to measurement will advance this field (Hill & Edwards, 2013).

Many parents report that they view parenting as a sacred calling (Mahoney et al., 2013), and sanctification may contextualize parental religiousness and so moderate it. Sactification is broadly conceptualized as ‘perceiving an aspect of life as having divine significance and meaning’ (Mahoney et al., 2013; Pargament & Mahoney, 2005). Greater sanctification of parenting is related to greater use of positive strategies by mothers and fathers (e.g., praise, induction) to elicit young childrens moral conduct (Volling et al., 2009). Viewing family relationships as sanctified might help to maintain the quality of family life, but greater sanctification of parenting may translate differently depending on how people construe spiritually responsible parental goals and methods. Thus, greater sanctification of parenting is associated with more positive interactions and with spanking children in mothers who interpret the Bible literally, but greater sanctification is associated more positive interactions and with less spanking in mothers who hold more liberal views of the Bible (Murray-Swank, Mahoney, & Pargament, 2006).

The nuanced and seeming internal contradictions of patterns of results of this study are frankly challenging but are not new. On an affirmative view, parental religiousness has clear relations to positive parenting and positive child adjustment, just as more frequent religious attendance and awarding importance to spirituality correlates with diminished risk of child maltreatment (Carothers, Borkowski, Lefever, & Whitman, 2005). On a dispiriting view, parental religiousness has equally clear relations to negative parenting and poorer child adjustment: Spiritual mechanisms can justify harsh parenting. Like an Escher drawing, the two hands together contest any simple reading of the roles of parental religiousness in the family. Can the same thing be good and bad both? Yes. Religion like other BIG things in life (the atom, the gene, the internet) can be forces for both good and bad, and the fact that they are should not deter us from reaching for a deeper understanding of them; rather we should embrace the tension they present, plumb its depths, and act to maximize the good and minimize the bad.

Conclusions

Up to now, the rapidly developing discipline of parenting research has focused on a selected array of determinants of parenting, prominently personality, child effects, and context, to the near exclusion of significant others, such as religion. More recent treatments have included religion, religiousness, and spirituality (Bornstein, 2016), but these forces remain understudied determinants of parenting. A developmental science that neglects the religious and spiritual dimensions of human existence is an underdeveloped science. Examining the roles of these socially significant constructs linked to parenting will be critical for understanding how parental religiousness alone and additively shapes parenting and has consequences for child well-being.

Religiousness is a foremost aspect of the everyday lives of billions of parents and youth around the world. Beside purportedly helping to cope with problems of human life that are significant, persistent, and intolerable, and questions that are unknowable and unanswerable, religion, religiousness, and spirituality dictate core values regarding family life, and so aspects of all three constitute formative influences in parenting and child adjustment (Bengston, 2013; Gaunt, 2008; Mahoney, 2005; Mahoney et al., 2008; Wilcox, 2002). Simple conclusions about how religion, religiousness, and spirituality shape parenting, and whether they are good or bad for children and adolescents, are inapt. In contrast, it is sensible to ask: Which dimensions of each are related to which parent practices and which child outcomes when and in which populations (Bornstein, 2015)? Research into their roles in parenting and child adjustment is just entering its formative stages, and despite their pervasiveness, religious institutions are still largely ‘unexamined crucibles’ in parenting and childrens lives (Roehlkepartain & Patel, 2006). Developmental science needs to continue to learn how they are expressed in the family and how they contribute in good ways and bad to parenting and child development.

Supplementary Material

Appendix S1: Additional information.

Table S1: Correlations among mother and father scales.

Key points.

Parental religiousness has effects on the way parents perceive and rear children and, in turn, how children develop and experience the world.

This study explored links between parental religiousness, parenting, and child adjustment in a large sample from four religious groups and the unaffiliated in 9 sites worldwide.

Parental religiousness had both positive and negative associations with parenting and child adjustment, and these effects were largely consistent across mothers and fathers, girls and boys, child- and parent-reported parenting, 4 religions and the unaffiliated, 9 sites, and controlling for multiple covariates.

With these several pathways identified, religious institutions and leaders and parents may labor to promote positive, and inhibit negative, associations of religiousness with parenting and child adjustment.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [grant RO1-HD054805] and the Fogarty International Center [grant RO3-TW008141] and was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NICHD. This manuscript was prepared, in part, during a Marbach Residence Program funded by the Jacobs Foundation.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Conflicts of interest statement: The authorsd have declared that they have no competing or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Achenbach TM. Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL 14–18, YSR, and TRF Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, Barbaranelli C, Caprara GV, Pastorelli C. Self-efficacy beliefs as shapers of childrens aspirations and career trajectories. Child Development. 2001;72:187–206. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Olsen JE, Shagle SC. Associations between parental psychological and behavioral control and youth internalized and externalized behaviors. Child Development. 1994;65:1120–1136. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartkowski JP, Xu X, Levin ML. Religion and child development: Evidence from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study. Social Science Research. 2008;37:18–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2007.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beit-Hallachmi B. Psychology and religion. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Psychology and its allied disciplines Vol 1 The humanities. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1984. pp. 241–282. [Google Scholar]

- Bengston V. Families and faith: How religion is passed down across generations. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH. Unpublished manuscript. NICHD; 2015. The Specificity principle in parenting and child development. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH. Determinants of parenting. In: Cicchetti D, editor. Developmental Psychopathology : Genes and Environment. 3rd. Vol. 4. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2016. pp. 180–270. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Putnick DL. Chronological age, cognitions, and practices in European American mothers: A multivariate study of parenting. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:850–864. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Putnick DL, Suwalsky JTD, Gini M. Maternal chronological age, prenatal and perinatal history, social support, and parenting of infants. Child Development. 2006;77:875–892. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00908.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottoms BL, Shaver PR, Goodman GS, Qin J. In the name of God: A profile of religion-related child abuse. Journal of Social Issues. 1995;51:85–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1995.tb01325.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Stoneman Z, Flor D. Parental religiosity, family processes, and youth competence in rural, two-parent African American families. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:696–706. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.32.4.696. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Browning DS, Green MC, Witte J, editors. Sex, marriage, and family in world religions. New York: Columbia University; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Carlisle RD, Tsang J-A. The virtues: Gratitude and forgiveness. In: Pargament KI, Exline JJ, Jones JW, editors. APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (Vol 1): Context, theory, and research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. pp. 423–437. [Google Scholar]

- Carothers SS, Borkowski JG, Lefever JB, Whitman TL. Religiosity and the socioemotional adjustment of adolescent mothers and their children. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:263–275. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Child Trends. Religiosity among youth. 2013 May; Retrieved from http://www.childtrends.org/?indicators=religiosity-among-youth.

- Decety J, Cowell JM, Lee K, Mahasneh R, Malcolm-Smith S, Selcuk B, Zhou X. The negative association between religiousness and childrens altruism across the world. Current Biology. 2015;25:2951–2955. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dein S. Religion, spirituality, depression, and anxiety: Theory, research, and practice. In: Pargament KI, Mahoney A, Shafranske EP, editors. APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (Vol 2): An applied psychology of religion and spirituality. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. pp. 241–255. [Google Scholar]

- DeMaris A, Mahoney A, Pargament KI. Doing the scut work of infant care: Does religiousness encourage father involvement? Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011;73:354–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00811.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doehring C. An applied integrative approach to exploring how religion and spirituality contribute or counteract prejudice and discrimination. In: Pargament KI, Mahoney A, Shafranske EP, editors. APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (Vol 2): An applied psychology of religion and spirituality. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. pp. 389–403. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty C, Funk C, Kiley J, Weisel R. Teaching the children: Sharp ideological differences, some common ground. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.people-press.org/2014/09/18/teaching-the-children-sharp-ideological-differences-some-common-ground/

- Dollahite DC. Fathering, faith, and spirituality. Journal of Mens Studies. 1998;7:3–15. doi: 10.3149/jms.0701.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duriez B, Soenens B, Neyrinck B, Vansteenkiste M. Is religiosity related to better parenting? Disentangling religiosity from religious cognitive style. Journal of Family Issues. 2009;30:1287–1307. doi: 10.1177/0192513X09334168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edgell P. Religion and family in a changing society. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Emmen RA, Malda M, Mesman J, Ekmekci H, van IJzendoorn MH. Sensitive parenting as a cross-cultural ideal: Sensitivity beliefs of Dutch, Moroccan, and Turkish mothers in the Netherlands. Attachment & Human Development. 2012;14:601–619. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2012.727258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans EM. Beyond scopes: Why creationism is here to stay. In: Rosengren KS, Johnson CN, Harris PL, editors. Imagining the impossible: Magical, scientific, and religious thinking in children. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 305–333. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Exline JJ, Pargament KI, Exline JJ, Jones JW, editors. APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (Vol 1): Context, theory, and research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. Religious and spiritual struggles; pp. 459–475. [Google Scholar]

- Fallot RD, Blanch AK. Religious and spiritual dimensions of traumatic violence. In: Pargament KI, Mahoney A, Shafranske EP, editors. APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (Vol 2): An applied psychology of religion and spirituality. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. pp. 371–387. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald T. The ideology of religious studies. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gaunt R. Maternal gatekeeping: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of Family Issues. 2008;29:373–395. doi: 10.1177/0192513X07307851. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnoe ML, Hetherington EM, Reiss D. Parental religiosity, parenting style, and adolescent social responsibility. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1999;19:199–225. doi: 10.1177/0272431699019002004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall DL, Matz DC, Wood W. Why dont we practice what we preach? A meta-analytic review of religious racism. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2010;14:126–139. doi: 10.1177/1088868309352179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill PC, Edwards E. Measurement in the psychology of religiousness and spirituality: Existing measures and new frontiers. In: Pargament KI, Exline JJ, Jones JW, editors. APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (Vol 1): Context, theory, and research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. pp. 51–77. [Google Scholar]

- Hill TD, Burdette AM, Regnerus M, Angel RJ. Religious involvement and attitudes toward parenting among low-income urban women. Journal of Family Issues. 2008;29:882–900. doi: 10.1177/0192513X07311949. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holden GW, Vittrup B. Religion. In: Bornstein MH, editor. The handbook of cultural developmental science Part 1 Domains of development across cultures. New York: Psychology Press; 2010. pp. 279–295. [Google Scholar]

- Holden GW, Williamson PA. Religion and child well-being. In: Ben-Arieh A, Casas F, Frones I, Korbin JE, editors. Handbook of child well-being: Theories, methods, and policies in global context. New York: Springer; 2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hood RW, Jr, Hill PC, Spilka B. The psychology of religion: An empirical approach. 4th. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hood RW, Spilka B, Hunsberger B, Gorsuch R. The psychology of religion. 2nd. New York: Guilford Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Jones JW. The psychology of contemporary religious violence: A multidimensional approach. In: Pargament KI, Mahoney A, Shafranske EP, editors. APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (Vol 2): An applied psychology of religion and spirituality. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. pp. 355–370. [Google Scholar]

- Kakihara F, Tilton-Weaver L. Adolescents interpretations of parental control: Differentiated by domain and types of control. Child Development. 2009;80:1722–1738. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Spoon J, Longo GS, McCullough ME. Adolescents who are less religious than their parents are at risk for externalizing and internalizing symptoms: The mediating role of parent-adolescent relationship quality. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012;26:636–641. doi: 10.1037/a0029176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King PE, Boyatzis CJ. Religious and spiritual development. In: Lamb ME, editor. Socioemotional processes: Volume 3 of the Handbook of child psychology and developmental science. 7th. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2015. pp. 975–1021. Editor-in-chief: R. M. Lerner. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King PE, Furrow JL. Religion as a resource for positive youth development: Religion, social capital, and moral outcomes. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:703–713. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.5.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King PE, Ramos JS, Clardy CE. Searching for the sacred: Religion, spirituality, and adolescent development. In: Pargament KI, Exline JJ, Jones JW, editors. APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (Vol 1): Context, theory, and research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. pp. 513–528. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, King D, Carson VB. Handbook of religion and health. 2nd. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, McCullough ME, Larson DB. Handbook of religion and health. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenthal KM. Religion, spirituality, and culture: Clarifying the direction of effects. In: Pargament KI, Exline JJ, Jones JW, editors. APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (Vol 1): Context, theory, and research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. pp. 239–255. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney A. Religion and conflict in marital and parent-child relationships. Journal of Social Issues. 2005;61:689–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00427.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney A. Religion in families, 1999–2009: A relational spirituality framework. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:805–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney A. The spirituality of us: Relational spirituality in the context of family relationships. In: Pargament KI, Exline JJ, Jones JW, editors. APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (Vol 1): Context, theory, and research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. pp. 365–389. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney A, Pargament KI, Hernandez KM. Heaven on earth: Beneficial effects of sanctification for individual and interpersonal well-being. In: Boniwell I, David SA, Ayers AC, editors. Oxford handbook of happiness. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney A, Pargament K, Jewell T, Swank AB, Scott E, Emery E, Rye M. Marriage and the spiritual realm: The role of proximal and distal religious constructs in marital functioning. Journal of Family Psychology. 1999;13:321–338. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.13.3.321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney A, Pargament KI, Swank A, Tarakeshwar N. Religion in the home in the 1980s and 90s: A meta-analytic review and conceptual analysis of religion, marriage, and parenting. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:559–596. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.15.4.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney A, Pargament K, Tarakeshwar N, Swank A. Religion in the home in the 1980s and 1990s: A meta-analytic review and conceptual analysis of links between religion, marriage, and parenting. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, S(1) 2008:63–101. doi: 10.1037/1941-1022.S.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks LD. Sacred practices in highly religious families: Christian, Jewish, Mormon, and Muslim perspectives. Family Process. 2004;43:217–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2004.04302007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuzawa T. The invention of world religions: Or, how European universalism was preserved in the language of pluralism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mattis JS, Ahluwalia MK, Cowie S-AE, Kirkland-Harris AM. Ethnicity, culture, and spiritual development. In: Roehlkepartain EC, King PE, Wagener L, Benson PL, editors. The handbook of spiritual development in childhood and adolescence. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2006. pp. 283–296. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Willoughby BL. Religion, self-regulation, and self-control: Associations, explanations, and implications. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:69–93. doi: 10.1037/a0014213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy M, Lee C, ONeill A, Groisman A, Roberts-Butelman K, Dinghra K, Porder K. Are there universal parenting concepts among culturally diverse families in an inner-city pediatric clinic? Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2005;19:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray-Swank A, Mahoney A, Pargament KI. Sanctification of parenting: Links to corporal punishment and parental warmth among biblically conservative and liberal mothers. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion. 2006;16:271–287. doi: 10.1207/s15327582ijpr1604_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B. Applications of causally defined direct and indirect effects in mediation analysis using SEM in Mplus. 2011 Available from https://www.statmodel.com/download/causalmediation.pdf.

- Oser FK, Scarlett WG, Bucher A. Religious and spiritual development throughout the lifespan. In: Lerner RM, editor. Theoretical models of human development Volume 1 of Handbook of child psychology. 6th. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2006. pp. 942–998. Editors-in-Chief: W. Damon & R. M. Lerner. [Google Scholar]

- Paloutzian RF, Park CL. Handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. The psychology of religion and coping: Theory, research, and practice. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. Spiritually integrated psychotherapy: Understanding and addressing the sacred. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Exline JJ, Jones JW, editors. APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Mahoney A. Sacred matters: Sanctification as a vital topic for the psychology of religion. The International Journal of the Psychology of Religion. 2005;15:179–198. doi: 10.1207/s15327582ijpr1503_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Mahoney A, Exline JJ, Jones JW, Shafranske EP, Pargament KI, Exline JJ, Jones JW, editors. APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (Vol 1): Context, theory, and research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Park HS, Bonner P. Family religious involvement, parenting practices and academic performance in adolescents. School Psychology International. 2008;29:348–362. doi: 10.1177/0143034308093677. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parrinder G. Sexual morality in the worlds religions. Oxford, England: Oneworld; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce LD, Axinn WG. The impact of family religious life on the quality of mother-child relations. American Sociological Review. 1998;63:810–828. doi: 10.2307/2657503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit GS, Harrist AW, Bates JE, Dodge KA. Family interaction, social cognition, and childrens subsequent relations with peers at kindergarten. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1991;8:383–402. doi: 10.1177/0265407591083005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prentiss CR. Religion and the creation of race and ethnicity. New York: NYU Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Regnerus MD, Elder GH. Staying on track in school: Religious influences in high-and low-risk settings. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2003;42:633–649. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-5906.2003.00208.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM. Development of reliable and valid short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1982;38:119–125. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198201)38:1<119::AID-JCLP2270380118>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez CM, Henderson RC. Who spares the rod? Religious orientation, social conformity, and child abuse potential. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roehlkepartain EC, Patel E. Congregations: Unexamined crucibles for spiritual development. In: Roehlkepartain EC, King PE, Wagener L, Benson PL, editors. The handbook of spiritual development in childhood and adolescence. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2006. pp. 324–336. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rohner RP. Parental Acceptance-Rejection/Control Questionnaire (PARQ/Control): Test manual. In: Rohner RP, Khaleque A, editors. Handbook for the study of parental acceptance and rejection. 4th. Storrs, CT: University of Connecticut; 2005. pp. 137–186. [Google Scholar]

- Sander A. Images of the child and childhood in religion. In: Hwang CP, Lamb ME, Sigel IE, editors. Images of childhood. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 14–26. [Google Scholar]

- Saroglou V. Religion, spirituality, and altruism. In: Pargament KI, Exline JJ, Jones JW, editors. APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (Vol 1): Context, theory, and research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. pp. 439–457. [Google Scholar]

- Silberman I, Higgins E, Dweck C. Religion and world change: Violence, terrorism versus peace. Journal of Social Issues. 2005;61:761–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00431.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, Denton ML. Soul searching: The religious and spiritual lives of American teenagers. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, Perou R, Lesesne C. Parent education. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting Vol 4 Applied parenting. 2nd. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 389–410. [Google Scholar]

- Snider JB, Clements A, Vazsonyi AT. Late adolescent perceptions of parent religiosity and parenting processes. Family Process. 2004;43:489–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2004.00036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streib H, Klein C. Atheists, agnostics, and apostates. In: Pargament KI, Exline JJ, Jones JW, editors. APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (Vol 1): Context, theory, and research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. pp. 713–728. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes CE, Regnerus MD. When faith divides family: Religious discord and adolescent reports of parent-child relations. Social Science Research. 2009;38:155–167. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Templeton JL, Eccles JS. The relation between spiritual development and identity processes. In: Roehlkepartain EC, King PE, Wagener L, Benson PL, editors. Handbook of spiritual development in childhood and adolescence. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Bruggen CO, Stams GJJ, Bögels SM. Research Review: The relation between child and parent anxiety and parental control: A meta‐analytic review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:1257–1269. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volling BL, Mahoney A, Rauer AJ. Sanctification of parenting, moral socialization, and young childrens conscience development. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2009;1:53–68. doi: 10.1037/a0014958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller JE. Religion and evil in the context of genocide. In: Pargament KI, Exline JJ, Jones JW, editors. APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (Vol 1): Context, theory, and research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. pp. 477–493. [Google Scholar]

- Weyand C, OLaughlin L, Bennett P. Dimensions of religiousness that influence parenting. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2013;5:182–191. doi: 10.1037/a0030627. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox WB. Conservative Protestant childrearing: Authoritarian or authoritative? American Sociological Review. 1998;63:796–809. doi: 10.2307/2657502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox WB. Religion, convention, and paternal involvement. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:780–792. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00780.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- WIN-Gallup International. Global index of religiosity and atheism [Press release] 2012 Retrieved from http://www.wingia.com/web/files/news/14/file/14.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1: Additional information.

Table S1: Correlations among mother and father scales.