Abstract

HIV prevention programs often focus on the physical social venues where men who have sex with men (MSM) frequent as sites where sex behaviors are assumed to be practiced and risk is conferred. But, how exactly these behaviors influence venue patronage is not well understood. In this study, we present a two-mode network analysis that determines the extent that three types of sex behaviors – condomless sex, sex-drug use, and group sex -- influence the patronage of different types of social venues among a population sample of young Black MSM (YBMSM) (N=623). A network analytic technique called exponential random graph modeling (ERGM) was used in a proof of concept analysis to verify how each sex behavior increases the likelihood of a venue patronage tie when estimated as either: (1) an attribute of an individual only and/or (2) a shared attribute between an individual and his peers. Findings reveal that sex behaviors, when modeled only as attributes possessed by focal individuals, were no more or less likely to affect choices to visit social venues. However, when the sex behaviors of peers were also taken into consideration, we learn that individuals were statistically more likely in all three behavioral conditions to go places that attracted other MSM who practiced the same behaviors. This demonstrates that social venues can function as intermediary contexts in which relationships can form between individuals that have greater risk potential given the venues attraction to people who share the same risk tendencies. As such, structuring interventions around these settings can be an effective way to capture the attention of YBMSM and engage them in HIV prevention.

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Although instances of new HIV infection are plateauing in the United States, new infections continue to rise within certain populations, for example young men who have sex with men (MSM) and in particular young black MSM (YBMSM) (CDC, 2016). Although, YBMSM make up less than 1% of the population, they constitute 25% of new infections with high prevalence in urban centers like Chicago (Schneider et al., 2013). At the same time, however, YBMSM tend to have fewer sex partners and engage in fewer HIV-related risk behaviors than their White MSM counterparts (Friedman, Cooper, & Osborne, 2009; Hallfors, Iritani, Miller, & Bauer, 2007). Taken together, these joint realities point to possible social and contextual factors at play in affecting rates of HIV in this population.

Traditionally, HIV prevention strategies have taken an individual-level approach, targeting personal behaviors -- like condomlesss sex or using drugs and alcohol during sex (i.e., sex-drug use) -- as primary factors associated with HIV susceptibility. Although this approach has made an undeniable impact on the spread of HIV more broadly, the disproportionate prevalence of HIV in vulnerable populations like YBMSM suggests the need for a wider net of prevention strategies.

In response to this need, scholars have cast their attention toward the social contexts (or networks) in which at-risk individuals are embedded to better understand pathways of transmission and to locate opportunities for intervention (Laumann, Ellingson, Mahay, Paik, & Youm, 2005; Schneider, 2013). To date, network studies that pertain to the transmission and prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) typically prioritize the sexual, social, or support ties that exist between individuals (Adimora, Schoenbach, & Doherty, 2006; Friedman & Aral, 2001; Latkin, Forman, Knowlton, & Sherman, 2003; Morris & Kretzschmar, 1995). Out of this research, we have learned about the structural and compositional features of interpersonal networks through which HIV risks are conferred, for example how the cohesion of an individual’s network (Potterat, Rothenberg, & Muth, 1999; Rothenberg, Baldwin, Trotter, & Muth, 2001), an individual’s position vis-à-vis other network members (Shah et al., 2014), and their exposure to other risky individuals (Morris, Goodreau, & Moody, 2007; Rice, 2010; Rice, Milburn, & Rotheram-Borus, 2007; Schneider et al., 2013) affects disease spread and risk susceptibility.

More recently, interest has emerged in the looser affiliations formed around broader socio-structural features of an individual’s environment, for example the social situations, places, and organizational structures around which individuals associate (Schneider, 2013), as ties that can confer HIV risks. Together, at-risk individuals and the spaces they occupy comprise the HIV “risk environment” (Rhodes, Singer, Bourgois, Friedman, & Strathdee, 2005). Expanding our lens to the level of “risk environment” demands a focus on the exogenous sources of risk (as opposed to just the cognitive or immediate interpersonal sources of risk). In so doing, it becomes possible to intervene at a more macro-level of social interaction and, consequently, impact greater portions of at-risk populations.

In this vein, social venues, the physical and virtual spaces where MSM go to meet and socialize with other MSM, are seen as potential “hotspots” for intervention (Elwood, Greene, & Carter, 2003; Grov, 2012; Grov, Parsons, & Bimbi, 2007) as they have been shown to be highly associated with the incidence of disease and related risk behaviors (Binson et al., 2001; Fujimoto, Williams, & Ross, 2013; Grov, Hirshfield, Remien, Humberstone, & Chiasson, 2013). This paper sets out to test a plausible theory behind this association – the theory of homophily.

Homophily occurs when individuals with similar traits share relationships (McPherson, Smith-Lovin, & Cook, 2001) and is generated from either a process of social selection (i.e., when individuals base relationships on their similarity in traits) or social influence (i.e., when an individual’s behavior is influenced by the behaviors of those with whom they have relations) (Robins, Pattison, Kalish, & Lusher, 2007). With respect to HIV transmission and prevention, scholars have investigated homophily for its effect on disease transmission and exposure to risk (Doherty, Schoenbach, & Adimora, 2009; Morris & Kretzschmar, 1995), as criteria for selecting popular opinion leaders for behavioral interventions (Kelly, 2004) and as a mechanism of multiplex tie formation in high-risk populations (Fujimoto, Wang, Ross, & Williams, 2015).

Only more recently has homophily been explored as a mechanism in the structuring of a socio-structural “risk environment” comprised of at-risk individuals and the social settings they frequent (Frost, 2007; Fujimoto et al., 2015; Fujimoto et al., 2013). In this scenario, homophily manifests as the passive clustering of individuals with the same sex behavior traits around the same venues. From a risk assessment and prevention perspective, when individuals with high-risk behaviors cluster together at venues, those venues are argued to be high-risk locations and, therefore, all patrons of these venues are at higher risk (Niekamp, Mercken, Hoebe, & Dukers-Muijrers, 2013). Thus, locations of passive behavioral clustering present important points for intervention.

APPROACH

In this paper, we conceptualize the HIV “risk environment” as an emergent network of relationships between YBMSM and the social venues they patronize and, in turn, seek to establish whether homophilous tendencies (i.e., the tendency to go where others with the same sexual preferences also go) structure these patterns of venue patronage among YBMSM. Traditional statistical methods like regression analysis assume independence in observations; meaning that what one observes about an individual, like their sexual orientation, is assumed to occur independently from what one observes about another’s sexual orientation. That said, network (or relational) data structures violate this assumption because the presence of some ties in a network affects the probability that other ties may be observed (Koskinen & Daraganova, 2013). For example, an individual’s decision to patronize a particular venue may depend on the other types of venues they frequent or the other types of people that patronize the venue.

Although there are a host of descriptive analytic techniques that have been developed to help characterize network data, these approaches are limited in a few ways that are relevant to the goals of this study. First, most descriptive network methods are designed for one-mode networks, which allow for only one type of actor. The network presented here, however, is comprised of two types of actors – YBMSM and social venues – making it a two-mode (or bipartite) network. Although we could transform the two-mode network into a one-mode network defined on YBMSM and the ties of joint venue affiliation among them, doing so would diminish the richness of the two-mode structure of the data featured here (Contractor, Wasserman, & Faust, 2006).

Second, exploratory and descriptive network analytic techniques are designed to provide a “snapshot” of a network (Keegan, Gergle, & Contractor, 2012), essentially characterizing what the network looks like as a static, already emerged social structure. In contrast, we aim to explain how the patronage network emerges. As such, an inferential method of analysis is needed that focuses on the specific dynamics that increase the likelihood that patronage ties will be formed in the first place. And finally, descriptive or exploratory analytic techniques tend to underscore the purely structural, self-organizing mechanisms of network emergence (e.g., when people tend to become friends with the friends of their friends) whilst unable to account for how attributes of network actors also motivate the formation of ties in the network (Contractor et al., 2006).

For these reasons, we turn to a class of statistical models for social networks called exponential random graph models (ERGMs) (Robins & Pattison, 2005; Robins et al., 2007; Wasserman & Pattison, 1996; Wasserman & Robins, 2005). ERGMs model network structure by accounting for the presence or absence of ties in the network as a function of local configurations (or patterns) of ties called parameters. These configurations can emerge from the connections actors make in response to other ties in their social environment (e.g., when popular venues continue to attract more YBMSM patrons) or in response to properties that exist outside the network like the attributes of other YBMSM (e.g., when HIV positive individuals prefer partnering with other HIV positive individuals).

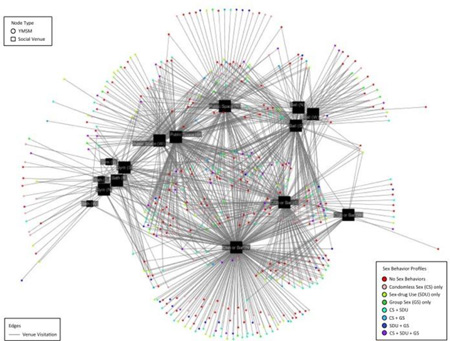

In this paper, we apply ERGMs to identify social processes at play in the emergence of a two-mode bipartite network. Bipartite networks consist of two sets of nodes or network actors (e.g., YBMSM and social venues), with ties defined only between members of each set (e.g., YBMSM-to-venue patronage) but not within the two sets of nodes (Wang, 2013). Selecting which patterns of interaction to include as parameters in an ERGM should be grounded in which distinct theories of social interaction one wants to test. Here we aim to verify whether homophilous tendencies among YBMSM motivate their venue patronage. Thus, we include parameters in the model that represent this phenomenon at a local level in the network while also testing the more socially naïve hypothesis that YBMSM who engage in risky sex behaviors are simply more likely to visit social venues than YBMSM who do not. As such, two general types of network configurations are considered in our model and are visualized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Local network configurations among YBMSM individuals A and B and social venue C of (a) individual venue choice conditioned by sex behavior and (b) venue popularity conditioned by sex behavior homophily: Chicago, IL; June 2013-July 2014.

In statistical terms, the effect of each parameter is estimated by determining the prevalence of the modeled configurations in the observed network and then assessing their statistical likelihood above what would occur by chance alone (Wasserman & Faust, 1994). A parameter estimate that is positive and significant indicates that ties are more likely to occur within the configuration tested. Conversely, parameter estimates that are negative and significant suggest that ties are less likely to occur within the configuration tested. ERGMs are deemed acceptable when the parameters converge, which occurs when the t-ratios for each parameter reaches <0.10. Details about the specification, estimation, and simulation of ERGMs are beyond the scope of this paper but can be found in (Lusher, Koskinen, and Robins, 2013). The models presented were implemented using MPNet, a network estimation program designed for one-mode, two-mode, and multiplex network data (Wang, Robins, & Pattison, 2006; Wang, Robins, Pattison, & Koskinen, 2014).

METHODS

Sampling and Recruitment

The data used in this study were collected from June 2013 to July 2014 as part of the initial wave of the uConnect study, a network cohort study of YBMSM living in Chicago (Khanna et al., 2016). Participants were recruited using a variant of classic link-tracing widely used in public health studies (Goel & Salganik, 2010) called Respondent Driven Sampling (RDS) (Heckathorn, 1997). To construct the sample of 623 YBMSM, we began by purposively selecting a diverse set of YBMSM to serve as seeds. In total, 62 seeds were identified from a range of social spaces that YBMSM occupy, including community social spaces and organizations, LGBT centers, HIV clinics, and online venues. Seeds were eligible to be interviewed if they: 1) self-identified as African American or Black, 2) were born male, 3) were between 16 and 29 years of age (inclusive), 4) reported oral or anal sex with a male within the past 24 months, and 5) were willing and able to provide informed consent at the time of the interview. Each enrolled seed was given instructions for recruiting other eligible YBMSM (up to a total of 6). Each subsequent wave of participants was instructed to do the same. Waves of referrals continued until the target sample size was reached (Khanna et al., 2016).

Of the 62 seeds recruited, 37 were productive (i.e., successfully recruited at least one additional individual) yielding referral chains with a maximum length of 13 and a median length of 3. Among all respondents, the distribution of the number of successful referrals was 0 (6.4%), 1 (44.3%), 2 (24.4%), 3 (15.1%), 4 (5.9%), 5 (2.5%) and 6 (1.4%) (Schneider et al., in press). Both seeds and sprouts were offered $60 for their participation in the study at each study visit and an additional $20 for each recruit who participated.

Data Collection

As a result of the recruitment procedures, we interviewed a sample of 623 YBMSM. Participants underwent a face-to-face staff-administered personal interview, which obtained socio-demographic, sexual health, and sex behavior data as well as information about their social and sexual networks. Given the time-consuming and demanding nature of eliciting network characteristics from respondents, a staff-administered questionnaire was deemed an appropriate mode of data collection. Interviewers not only motivate respondents to complete the survey, but they can also answer questions and provide procedural explanations when needed (Matzat & Snijders, 2010; Tourangeau, Rips, & Rasinski, 2000).

Information about participants’ patronage of social venues was collected by asking respondents about their patronage of certain types of physical venues to meet and socialize with other MSM. The different types of venues included both sex-on-premise venues (e.g., bathhouses) as well as their more social counterparts (e.g., bars and clubs). We included both types of venues because, at their core, all social venues form settings where MSM gather and socialize and, potentially, meet new partners (Frost, 2007; Fujimoto et al., 2015). As such, they create reliable social contexts where the likelihood of being exposed to certain types of people with particular risk proclivities increases and where future partnerships may be forged (Grov, 2012; Raymond, Bingham, & McFarland, 2008). The final roster of venue types included: clubs & bars, gyms, public spaces, bathhouses or adult bookstores, and ballroom events (see Arnold & Bailey, 2009 for a description of the ballroom community). As such, the raw data collected from participants represent their tastes in venue-types not in specific venues.

To measure venue patronage, respondents indicated on a 9-point categorical scale how often during the past 12 months they had visited each type of social venue. Response categories included: “never”, “less than once a year”, “once a year”, “a couple of times a year”, “once a month”, “once every two weeks”, “once a week”, “several times a week”, and “every day”. Using “once a year” as the cutoff, we created a dummy variable to represent whether or not a respondent visited each type of venue at least once in the past 12 months.

Finally, respondents that had visited a venue-type at least once in the past 12 months were also prompted to delineate the regions of the city – South Side, North Side, and West Side – they travel to in order to attend the type of venue in question. This finer granularity resulted in 15 geographically specified venue-types. The decision to distinguish between venue-types in different regions of the city and, therefore, to treat them as distinct nodes in the two-mode network was based on prior knowledge of the demographic and socio-economic differences between these regions that we believe affect the expressions of LGBT culture within them. The North Side is a densely populated region of the city where a primarily White middle to upper-middle class “gay enclave” exists. Generally recognized as the cultural center of the LGBT population in the city, this community area contains a majority of the city’s gay establishments (e.g., bars, nightclubs, bathhouses) as well as its LGBT cultural and advocacy centers. The South Side, on the other hand, is a historical majority Black community with significant socio-economic disparities among its residents. Although the South Side is home to a sizeable population of Black gay and bisexual men and transgender women, it hosts fewer and less geographically concentrated gay establishments and is not recognized by outsiders as being a “gay enclave.” Finally, the city’s West Side is an ethnically diverse area consisting largely of working class and lower-income Black and Latino residents. The West Side also does not have an established gay community and has even fewer gay establishments than the South Side. The make-up of these specific regions have many similarities with communities in other domestic HIV epicenters in the United States.

YBMSM Attribute Construction

We include three sex-related behaviors in the analysis to determine their impact on venue patronage. These include condomless sex, sex-drug use, and group sex (Schneider et al., 2013). Condomless sex was measured on the basis of frequency of condom use with named anal sex partners in the past 6 months. If the respondent indicated not always using condoms with any of their partners, he/she was coded as having had condomless sex. Similarly, respondents were asked about their use of drugs to enhance their sexual experience or make sex easier to get (Schneider et al., 2013). Respondents who indicated having done so with at least one partner were coded as having used sex-drugs. Group sex is a self-reported measure of whether or not a respondent indicated having engaged in sex with two or more partners at the same time at least once in the past 12 months (Schneider et al., 2013).

We also included measures of HIV status and age as controls in the analysis. A dummy variable representing an individual’s self-reported HIV positive status was included to account for the possibility that being sero-positive might affect an individual’s interest in patronizing social venues. Further, to account for restricted access to some venues based on legal drinking age, we included another dummy variable that represented being at least 21 years of age.

RESULTS

Individual and Network Descriptives

Descriptive statistics for the study sample of YBMSM (N=623) are summarized in Table 1. A majority of respondents were 21 years of age or older (73%) and about a quarter (24%) self-reported being HIV positive. With their sex partners during the past 6 months, respondents reported engaging in condomless sex (46%) and sex-drug use (40%). Far fewer self-reported participation in group sex (21%) during the past 12 months. With respect to their venue patronage in the past 12 months, a majority of respondents (61%) reported going to clubs & bars and nearly half (46%) reported going to public spaces. Meanwhile, about a quarter or less reported attending ballroom events (26%), gyms (11%) or bathhouses & adult bookstores (9%). Of those who visited physical venues, more than half spent time on the North (60%) and South Sides (56%), while fewer than a quarter (17%) visited venues on the West Side. Among the five types of physical social venues, clubs & bars and bathhouses & adult bookstores were most patronized on the North Side, while public spaces, ballroom events, and gyms were most patronized on the South Side.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of a population-based sample of young Black men who have sex with men (YBMSM): Chicago, IL; June 2013-July 2014

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Controls | |

| Age (21 and over) | 455 (73) |

| HIV Positive (self-reported) | 150 (24) |

| Sex Behaviors | |

| Condomless Sex (in the past 6 months) | 287 (46) |

| Sex-drug Use (in the past 6 months) | 252 (40) |

| Group Sex (in the past 12 months) | 128 (21) |

| Venue Types Visited (at least once in the past 12 months) | |

| Clubs & Bars | 378 (61) |

| Public Spaces | 286 (46) |

| Ballroom Events | 165 (26) |

| Gyms | 69 (11) |

| Bathhouses or Adult Bookstores | 59 (9) |

| Venue Regions Visited (at least once in the past 12 months) | |

| North Side | 374 (60) |

| South Side | 346 (56) |

| West Side | 104 (17) |

We also note that nearly one-third of respondents (29%) indicated abstaining from physical social venues all together in the past 12 months. From analysis not featured in this study, we know that 115 of these individuals relied exclusively on the Internet to seek partners, a type of venue that we chose to exclude from this study about YBMSM’s patronage of physical social venues. This leaves 63 respondents who appear to have spent no time in the last 12 months in physical or virtual social venues to meet other MSM.

Cross-tabulations of the sex behaviors of YBMSM and the types and geographic regions of their venue selections are shown in Table 2. Individuals who engage in condomless sex, sex-drug use, and group sex tend to follow the same general pattern of patronage as was shown in Table 1 when YBMSM were not stratified by sex behaviors. Namely, clubs & bars are the most popular venues, followed by public spaces and ballroom events. However, when sex behaviors are accounted for, we see that YBMSM who take sexual risks tend to attend bathhouses & adult bookstores more than gyms.

Table 2.

Cross-tabulation analysis of YBMSM sex behaviors and venue types and regions: Chicago, IL; June 2013–July 2014

| YBMSM Sex Behaviors | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Venue Characteristics | Condomless sex | Sex-drug use | Group sex |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Venue Types | |||

| Clubs & Bars | 180 (63) | 172 (68) | 83 (65) |

| Public Spaces | 131 (46) | 131 (52) | 59 (46) |

| Ballroom Events | 77 (27) | 73 (29) | 35 (27) |

| Gyms | 24 (8) | 34 (14) | 15 (12) |

| Bathhouses & Adult Bookstores | 25 (9) | 37 (15) | 28 (22) |

| Venue Regions | |||

| North Side | 182 (63) | 174 (69) | 83 (65) |

| South Side | 154 (54) | 161 (64) | 79 (62) |

| West Side | 44 (15) | 51 (20) | 18 (14) |

| Total N | 287 | 252 | 128 |

Note: Aggregated percentages exceed 100 percent because individuals can patronize more than one type of venue and more than one venue region.

Similarly, with respect to the regions YBMSM patronize, cross-tabulations show the same basic pattern of patronage as were shown when sex behaviors were not factored in – individuals who engaged in condomless sex, sex-drug use, and/or group sex, seemed to favor North Side venues, followed by South Side venues. West Side venues were visited the least. Taken together, the similarity between the distributions of venue patronage featured in Tables 1 and 2 suggest no obvious pattern of association between sex behaviors and venue type and geographic regions of choice.

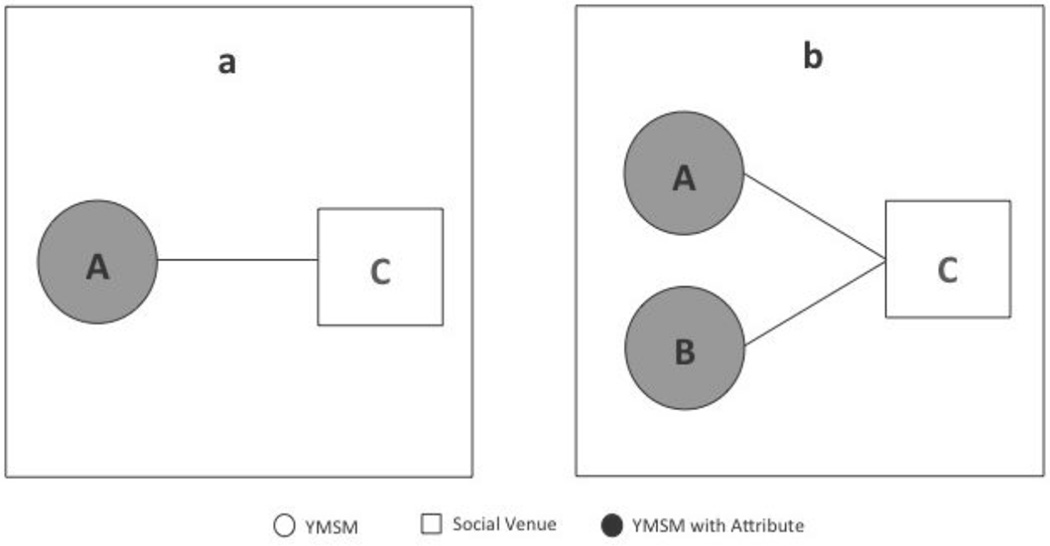

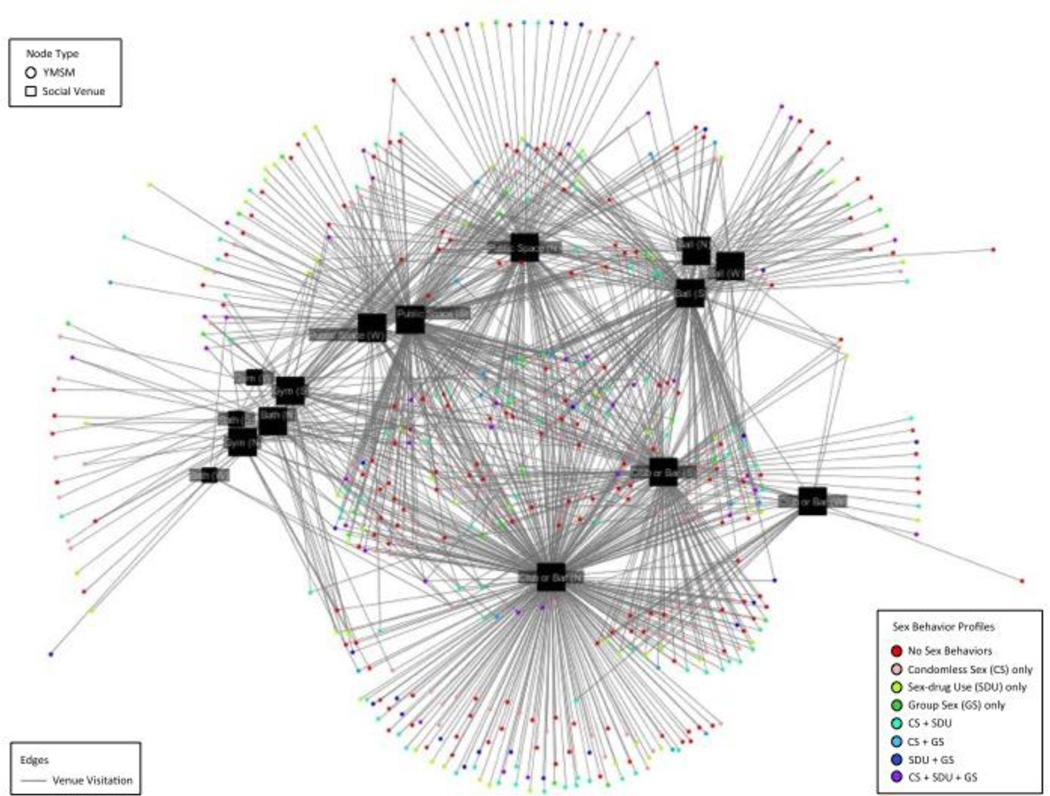

The final venue patronage network consists of 623 YBMSM and 15 geographically-specified venue types. Figure 2 illustrates the two-mode venue patronage network. On average, YBMSM patronized 1.95 different types of venues in the past 12 months, corresponding to a network density of 13%. The relatively low density of the patronage network suggests that most YBMSM have distinct preferences for which type of venue they attend and/or the neighborhoods in which they attend it. Because sex behaviors are not mutually exclusive categories, YBMSM nodes are differentiated on the basis of which combination of behaviors they engage in (i.e., their sex behavior profiles). The lack of any noticeable clustering on any of the sex behavior profiles around particular venue types reinforces our interpretation of the cross-tabulation analysis featured in Table 2.

Figure 2.

The two-mode venue patronage network among 623 young Black men who have sex with men in relation to sex behavior profile: Chicago, IL; June 2013-July 2014

Caption: The two-mode venue patronage network depicts YBMSM as circles (N=623) and venues as squares (N=15). Venues are sized by degree (i.e., number of YBMSM patrons) and YBMSM are colored by the different combination of sex behaviors they engage in. A line between an individual and a venue represents a patronage relationship. In total, there are 1,216 patronage ties out of a possible 9,345.

Bipartite Exponential Random Graph Model (ERGM)

Results of the bipartite ERGM analysis are shown in Table 3. Reported in this table are parameter estimates, standard errors, and convergence statistics (or t-ratios). The ML estimate for a parameter reveals the direction of its propensity to exist in the network above what would be expected by chance alone. Thus, a negative estimate is taken to mean that a parameter is less likely to occur while a positive estimate indicates a greater likelihood of occurrence. Significant parameter estimates are marked with stars. Significance is achieved when the absolute value of the ML estimate is greater than twice the magnitude of the standard error (Shumate & Palazzolo, 2010). Also associated with each parameter is a convergence statistic (or t-ratio). When the value of this statistic is below .10 it is taken to mean that the parameter has converged and is a good fit in the model of interest.

Table 3.

Exponential random graph model (ERGM) for the two-mode venue patronage network: Chicago, IL; June 2013–July 2014

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | ML Est. |

Std. Error |

t-ratio | ML Est. |

Std. Error |

t-ratio |

| Purely structural effects | ||||||

| Edge | −1.95 | 0.04 | 0.04* | −2.08 | 0.07 | −0.07 |

| YBMSM attributes | ||||||

| Age (21 and over) | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.01* | 0.06 | 0.07 | −0.05 |

| HIV positive | −0.13 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.08 | −0.03 |

| Condomless Sex | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.01 | −0.43 | 0.07 | −0.09* |

| Sex-drug Use | −0.04 | 0.15 | 0.01 | −0.48 | 0.08 | −0.03* |

| Group Sex | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.06 | −0.20 | 0.10 | −0.05 |

| Condomless Sex (homophily) | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.04* | |||

| Sex-drug Use (homophily) | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02* | |||

| Group Sex (homophily) | 0.02 | 0.00 | −0.04* | |||

In Model 1, we model the ties of patronage between YBMSM and venues as decisions conditioned on an individual’s sex behaviors but which are made independently of other YBMSMs’ venue patronage. This enables us to see whether, absent of any knowledge of what other YBMSM are doing, YBMSM who engage in particular sex behaviors are simply more likely to frequent venues than YBMSM who do not. In that age and HIV status may restrict an individual’s ability or proclivity to go to social venues, we control for these potential confounders in the model.

The negative estimate for the edges parameter reflects the likelihood of a network tie appearing entirely by chance. One can think of this as the “intercept term,” reflecting the density of the network if no other effects were present. Results show that the edge parameter is negative and significant, indicating that there is a smaller chance than expected that individuals will patronize a social venue. This reinforces what is already known about the low density of the observed network. Regarding the effects of risk behaviors on individual venue choice, results show that neither (1) having condomless sex, (2) using sex-drugs, or (3) engaging in group sex is any more or less likely to motivate venue patronage, even after accounting for the positive and significant effect of being at least 21 years of age.

In Model 2 we introduce three additional parameters that represent each behavior’s impact on the types of venues that individuals patronize when operationalized as a homophily mechanism, whereby individuals with the same risk tendencies cluster around the same places. Results show that individuals that have condomless sex, use sex-drugs, and/or participate in group sex have tendencies to go places where other MSM that engage in the same types of sexual behavior also go. This provides support for the idea that the places where YBMSM go to meet other men may enable the formation of social relationships that have high risk potential. The caveat is that the magnitudes of the effects are small.

However, in adding the homophily parameters to the model, the significant effect of age disappears and the individual-level effects of condomless sex and sex-drug use that we estimated in Model 1 are now negatively significant. We interpret this to mean that individuals who engage in condomless sex and sex-drug use are actually less likely to indicate going to venues than those who do not take those risks. But when they do visit these places, they tend to go where other MSM who engage in the same risks also go. This lends support for what others have found with respect to the passive clustering of risk behaviors and infection around social settings (Friedman, Cooper, & Osborne, 2009; Fujimoto et al., 2013).

The former steps analyzed a select set of local-level processes that structure patterns of venue patronage among YBMSM. The final step is to determine whether the specified model is a good representation of how the observed network could have been formed (Robins & Lusher, 2013). To this end, we performed a goodness-of-fit test by simulating a sample of 10,000 networks based on the estimated ERGM and comparing how well the model captures key features of the observed network. Given that we chose to focus only on attribute specific parameters, it is unsurprising that our model did not adequately capture the self-organizing network features. We address this as a limitation in the Discussion.

DISCUSSION

This study sought to clarify the relationship between HIV-related risk behaviors and social venue patronage, by imagining venue patronage as a network composed of two types of actors -- YBMSM and social venues -- with the ties between these two sets of actors representing patronage relationships. Using a stochastic network modeling technique designed for two-mode network structures called Exponential Random Graph Models (ERGM) (Wasserman & Pattison, 1996), we aimed to determine whether and how sex behaviors of YBMSM – i.e., condomless sex, sex-drug use, and group sex – motivate their patronage patterns. We do so by testing the homophily hypothesis -- that YBMSM are more likely to gravitate toward the types of venues where other YBMSM with similar behavioral preferences also go – while also accounting for a more naïve hypothesis that YBMSM who engage in risky behaviours are more inclined to patronize venues, irrespective of who else goes there.

We found that the relationship between sex behaviors and venue visitation depends on the type of local configuration into which the behavioral attributes are parameterized. When risk behaviors were modeled only as a feature of an independent tie between an individual and a venue, patronage was no more or less observed in people who engaged in risky behaviors than in those who do not. In other words, having a risky sex behavior profile did not per se make an individual more likely to frequent venues. However, when we model the same behaviors as patterns of homophily, we learned that individuals who engaged in these behaviors were significantly more likely to gravitate toward the places where other patrons who engage in the same behaviors also went, albeit the magnitudes of these effects were small. Further, when homophilous processes were accounted for, we saw that the simpler parameters representing patronage of venues irrespective of the patronage choices of other people in the network were actually less likely to be observed in those who engaged in risky sex behaviors than in those who did not.

Taken together, findings from Model 2 present an empirical conundrum to unpack. Why are the men that practice potentially risky sexual behaviors less likely to patronize social venues, but when they do patronize these places, they tend to go where others like them also gravitate? As noted previously, we excluded website patronage from the analysis as it was our intent to focus on physical social venues as opposed to virtual ones. However, data analysis not shown here reveals significant associations between the use of online platforms to meet other MSM and all three of the sex behaviors in question. Whereas, among physical venues, the only significant relationships are between sex-drug use and the patronage of clubs & bars, public spaces and bathhouses & bookstores. Thus, absent of any knowledge about where others in their network go to meet other men, it would appear as though individuals who engage in HIV-related sex behaviors are more drawn to online venues like social networking sites, where they can search more selectively and anonymously (Rice et al., 2012).

That said, the act of logging into a social networking site like Grindr is not a social one in that an individual’s time spent on such a site typically occurs in isolation. This is in contrast to the more social act of going to physical venues like clubs & bars, whereby individuals attend these places with their peers. If we assume that homophily in sex behaviors is also likely to occur among friend groups, then this may explain our findings with respect to homophilous clustering. When those who engage in sexual risk behaviors do go to physical venues, they may be doing so with friends who also engage in the same behaviors. Although it is beyond the scope of this paper to explore this possibility, future research should explore the interplay between the overlapping friendship networks and venue affiliation networks among YBMSM.

While it remains to be seen from the analysis whether or not physical venues actually broker potentially risky sexual partnerships, our findings have practical implications for HIV prevention research and outreach. The idea that social venues ought to be considered conduits for education and prevention emerged in the 1980s during the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Of particular concern was the role that bathhouses played in promoting or enabling risky sexual behaviors. While forced closure was the point of early conversation in public health circles, it soon became apparent that collaboration might be a more effective strategy. Collaborating not only gave public heath practitioners the opportunity to reach at-risk patrons (Woods & Binson, 2003), it also gave bathhouse management the opportunity to remain in business while also taking measures to protect the health and wellbeing of their clients (Woods, Binson, Mayne, Gore, & Rebchook, 2000). We reiterate this realization and emphasize that social venues can function as important bottlenecks of risky sexual partnerships before they have the chance to develop. And, by interviewing at-risk individuals about the venues they patronize, venues that are not already engaged in prevention messaging and education can be identified and reached out to for partnership opportunities.

Additionally, the fact that there is a significant trend for individuals to patronize places where individuals with the same risk proclivities also go presents an opportunity to leverage those patterns of venue affiliation for tailored message diffusion and outreach approaches. Different sex behaviors warrant different prevention messages. However, capturing the attention of the appropriate audience for those tailored messages can be difficult. For this reason, social venues become a useful channel of communication with immense potential to reach a sizeable yet specific audience with prevention messages, as has been shown within the Chicago house/ballroom community with respect to raising awareness about Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) (Khanna et al., 2016). Venues also tend to facilitate the formation of weak ties among patrons, which makes them well suited for diffusing novel forms of information to wider audiences (Fujimoto et al., 2015). Thus, the combination of weak ties and patrons with common sex behavior profiles enables venues to be effective and efficient channels in the diffusion of behavior-specific prevention messages.

Our study has several limitations that warrant mention. With respect to data collection, we measured venue patronage using a response set comprised of broad categories of geographically designated venue types (i.e., South Side clubs & bars) as opposed to specific venues that could be coded post hoc for these broader characteristics. The decision to solicit data on venue-types as opposed to particular venues was two-fold. First, in an interviewer-administered survey, it is easier to elicit responses to a shorter roster of venue-types than an extensive list of specific venues that would require more precise recall from respondents. Second, constructing a complete sample of specific social venues that span the different venue types that we were interested in was too great a task for the scope of the study. However, it is possible that we captured an affiliation network that is too broad to be considered a first-order risk network for the individuals in our sample. We also note that the social presence of an interviewer during data collection may have led respondents to underreport stigmatized behaviors like sex behaviors (Catania, Gibson, Chitwood, & Coates, 1990), although some work has found no differences in reporting behavior between interviewer- and self-administered modes (Kalichman, Kelly, & Stevenson, 1997).

With respect to data analysis, our intention was to demonstrate how ERGMs could be used to clarify the nature of the relationship between sex behaviors and venue patronage when venue patronage itself is conceived as a network of ties between YBMSM and social venues, as opposed to an independent individual-level outcome. That said, it only captures a partial representation of possible network mechanisms that may undergird the emergence of a two-mode venue patronage network. To paint a more complete picture of the internal and external factors that drive patterns of venue affiliation among YBMSM, a more robust ERGM could include more complex structural parameters as well as additional attributes of both YBMSM and venues. Relatedly, due to a limitation of 2-mode ERGMs, we cannot include as covariates any co-evolving relationships among YBMSM (e.g., sex partnerships and friendships). Thus, it is a common challenge to verify whether behavioral homophily is a network mechanism in its own right or whether it is a confounder for some other type of ongoing relationship. Recent developments in multiplex modeling techniques (Wang, Robins, Pattison, & Lazega, 2013) offer the opportunity to explore this in the future.

Finally, regarding the interpretation of our results, our data are cross-sectional and not longitudinal, which means that inferences about cause and effect cannot be made. Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that sex behaviors are the adopted outcomes of venue patronage and not the antecedents.

Despite these limitations, our findings provide an account of sexual risk behaviors as underlying mechanisms in the structuring of a socio-structural risk environment and social venues as the intermediary physical settings where relationships between YBMSM can be formed and where patterns of risk emerge. As such, structuring interventions around these settings can be an effective way to capture the attention of YBMSM and engage them in HIV prevention. However, social venues can play a variety of roles in prevention interventions, including being the targets of social and behavioral intervention, the channels through which prevention messages are diffused, or the beacons of change itself. Thus, knowing how best to incorporate venues into preventive outreach requires a deeper understanding of their relationship to the sexual risks that their patrons take and the role that they play in enabling or constraining the activation of those risks.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ishida Robinson, Eve Zurawski, Billy Davis and Michelle Taylor for their invaluable support. We also thank study participants for contributing to the network cohort study.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This study was funded by the NIH (R01DA033875 and R01MH100021). The authors have no conflict of interest. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Doherty IA. HIV and African Americans in the southern United States: sexual networks and social context. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2006;33(7):S39–S45. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000228298.07826.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold E, Bailey MM. Constructing home and family: how the ballroom community supports African American GLBTQ youth in the face of HIV/AIDS. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2009;21(2-3):171–188. doi: 10.1080/10538720902772006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binson D, Woods WJ, Pollack L, Paul J, Stall R, Catania JA. Differential HIV risk in bathhouses and public cruising areas. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(9):1482–1486. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.9.1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania JA, Gibson DR, Chitwood DD, Coates TJ. Methodological problems in AIDS behavioral research: influences on measurement error and participation bias in studies of sexual behavior. Psychological bulletin. 1990;108(3):339. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. CDC Fact Sheet: New HIV Infections in the United States. 2016 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/new-hiv-infections-508.pdf.

- Contractor NS, Wasserman S, Faust K. Testing multitheoretical, multilevel hypotheses about organizational networks: An analytic framework and empirical example. Academy of Management Review. 2006;31(3):681–703. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty IA, Schoenbach VJ, Adimora AA. Sexual mixing patterns and heterosexual HIV transmission among African Americans in the southeastern United States. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2009;52(1):114. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ab5e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwood WN, Greene K, Carter KK. Gentlemen don’t speak: Communication norms and condom use in bathhouses. Journal of Applied Communication Research. 2003;31(4):277–297. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman S, Aral S. Social networks, risk-potential networks, health, and disease. Journal of Urban Health. 2001;78(3):411–418. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman S, Cooper HL, Osborne AH. Structural and social contexts of HIV risk Among African Americans. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(6):1002–1008. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.140327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost SDW. Using sexual affiliation networks to describe the sexual structure of a population. Sexually transmitted infections. 2007;83(suppl 1) doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.023580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto K, Wang P, Ross MW, Williams ML. Venue-mediated weak ties in multiplex HIV transmission risk networks among drug-using male sex workers and associates. Journal Information. 2015;105(6) doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto K, Williams ML, Ross MW. Venue-based affiliation networks and HIV risk-taking behavior among male sex workers. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2013;40(6):453. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31829186e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel S, Salganik MJ. Assessing respondent-driven sampling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(15):6743–6747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000261107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grov C. HIV risk and substance use in men who have sex with men surveyed in bathhouses, bars/clubs, and on Craigslist. org: Venue of recruitment matters. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16(4):807–817. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9999-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grov C, Hirshfield S, Remien RH, Humberstone M, Chiasson MA. Exploring the venue’s role in risky sexual behavior among gay and bisexual men: an event-level analysis from a national online survey in the US. Archives of sexual behavior. 2013;42(2):291–302. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9854-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grov C, Parsons JT, Bimbi DS. Sexual risk behavior and venues for meeting sex partners: an intercept survey of gay and bisexual men in LA and NYC. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11(6):915–926. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9199-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallfors DD, Iritani BJ, Miller WC, Bauer DJ. Sexual and drug behavior patterns and HIV and STD racial disparities: the need for new directions. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(1):125–132. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.075747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD. Respondent-Driven Sampling: A New Approach to the Study of Hidden Populations. Social Problems. 1997;44(2):174. [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Kelly JA, Stevenson LY. Priming effects of HIV risk assessments on related perceptions and behavior: An experimental field study. AIDS and Behavior. 1997;1(1):3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Keegan B, Gergle D, Contractor N. Do editors or articles drive collaboration?: multilevel statistical network analysis of wikipedia coauthorship. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA. Popular opinion leaders and HIV prevention peer education: resolving discrepant findings, and implications for the development of effective community programmes. AIDS care. 2004;16(2):139–150. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001640986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna AS, Michaels S, Skaathun B, Morgan E, Green K, Young L, Schneider JA. Preexposure Prophylaxis Awareness and Use in a Population-Based Sample of Young Black Men Who Have Sex With Men. JAMA internal medicine. 2016;176(1):136–138. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.6536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskinen J, Daraganova G. Dependence graphs and sufficient statistics. In: Lusher D, Koskinen J, Robins G, editors. Exponential Random Graph Models for Social Networks. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2013. pp. 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Latkin CA, Forman V, Knowlton A, Sherman S. Norms, social networks, and HIV-related risk behaviors among urban disadvantaged drug users. Social science & medicine. 2003;56(3):465–476. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, Ellingson S, Mahay J, Paik A, Youm Y. The sexual organization of the city. University of Chicago Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Matzat U, Snijders C. Does the online collection of ego-centered network data reduce data quality? An experimental comparison. Social Networks. 2010;32(2):105–111. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Cook JM. Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual review of sociology. 2001:415–444. [Google Scholar]

- Morris M, Goodreau S, Moody J. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2007. Sexual networks, concurrency, and STD/HIV; pp. 109–126. [Google Scholar]

- Morris M, Kretzschmar M. Concurrent partnerships and transmission dynamics in networks. Social Networks. 1995;17(3):299–318. [Google Scholar]

- Niekamp A-M, Mercken LAG, Hoebe CJPA, Dukers-Muijrers NHTM. A sexual affiliation network of swingers, heterosexuals practicing risk behaviours that potentiate the spread of sexually transmitted infections: A two-mode approach. Social Networks. 2013;35(2):223–236. [Google Scholar]

- Potterat JJ, Rothenberg RB, Muth SQ. Network structural dynamics and infectious disease propagation. International journal of STD & AIDS. 1999;10(3):182–185. doi: 10.1258/0956462991913853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond HF, Bingham T, McFarland W. Locating unrecognized HIV infections among men who have sex with men: San Francisco and Los Angeles. AIDS Education & Prevention. 2008;20(5):408–419. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2008.20.5.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T, Singer M, Bourgois P, Friedman SR, Strathdee SA. The social structural production of HIV risk among injecting drug users. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(5):1026–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice E. The positive role of social networks and social networking technology in the condom-using behaviors of homeless young people. Public health reports. 2010:588–595. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice E, Holloway I, Winetrobe H, Rhoades H, Barman-Adhikari A, Gibbs J, Dunlap S. Sex risk among young men who have sex with men who use Grindr, a smartphone geosocial networking application. Journal of AIDS & clinical research, 2012. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Rice E, Milburn NG, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Pro-social and problematic social network influences on HIV/AIDS risk behaviours among newly homeless youth in Los Angeles. AIDS care. 2007;19(5):697–704. doi: 10.1080/09540120601087038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins G, Lusher D. Illustrations: simulation, estimation and goodness of fit. Exponential random graph models for social networks: Theory, methods and applications. 2013:167–186. [Google Scholar]

- Robins G, Pattison P. Interdependencies and social processes: Dependence graphs and generalized dependence structures. Models and methods in social network analysis. 2005;28:192. [Google Scholar]

- Robins G, Pattison P, Kalish Y, Lusher D. An introduction to exponential random graph (p*) models for social networks. Social Networks. 2007;29(2):173–191. [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberg R, Baldwin J, Trotter R, Muth S. The risk environment for HIV transmission: Results from the Atlanta and Flagstaff network studies. Journal of Urban Health. 2001;78(3):419–432. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider J. Sociostructural 2-mode network analysis: critical connections for HIV transmission elimination. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2013;40(6):459–461. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000430672.69321.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider J, Cornwell B, Jonas A, Behler R, Lancki N, Skaathun B, Laumann EO. Network dynamics and HIV risk and prevention in a population-based cohort of Young Black Men Who have Sex with Men. Network Science. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider J, Cornwell B, Ostrow D, Michaels S, Schumm P, Laumann EO, Friedman S. Network mixing and network influences most linked to HIV infection and risk behavior in the HIV epidemic among black men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(1):e28–e36. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah NS, Iveniuk J, Muth SQ, Michaels S, Jose J-A, Laumann EO, Schneider JA. Structural bridging network position is associated with HIV status in a younger Black men who have sex with men epidemic. AIDS and Behavior. 2014;18(2):335–345. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0677-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumate M, Palazzolo ET. Exponential random graph (p*) models as a method for social network analysis in communication research. Commun Methods Meas. 2010;4(4):341–371. [Google Scholar]

- Tourangeau R, Rips LJ, Rasinski K. The psychology of survey response. Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wang P. Exponential Random Graph Models for Social Networks: Theory, Method and Applications. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2013. ERGM extensions: Models for multiple networks and bipartite networks. [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Robins G, Pattison P. University of Melbourne. 2006. PNet: A program for the simulation and estimation of exponential random graph models. [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Robins G, Pattison P, Lazega E. Exponential random graph models for multilevel networks. Social Networks. 2013;35(1):96–115. [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Robins GL, Pattison PE, Koskinen JH. Melbourne School of Psychological Sciences. Australia: The University of Melbourne, Melbourne; 2014. MPNet: Program for the simulation and estimation of (p*) exponential random graph models for multilevel networks. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman S, Faust K. Social network analysis: Methods and applications. Vol. 8. Cambridge university press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman S, Pattison P. Logit models and logistic regressions for social networks: I. An introduction to Markov graphs andp. Psychometrika. 1996;61(3):401–425. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman S, Robins G. An introduction to random graphs, dependence graphs, and p*. Models and methods in social network analysis. 2005;27:148–161. [Google Scholar]

- Woods WJ, Binson D. Public health policy and gay bathhouses. Journal of homosexuality. 2003;44(3–4):1–21. doi: 10.1300/J082v44n03_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods WJ, Binson DK, Mayne TJ, Gore LR, Rebchook GM. HIV/sexually transmitted disease education and prevention in US bathhouse and sex club environments. AIDS. 2000;14(5):625–626. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200003310-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]