Abstract

Although advances in medical care have significantly improved sepsis survival, sepsis remains the leading cause of death in the ICU. This is likely due to a lack of complete understanding of the pathophysiologic mechanisms that lead to dysfunctional immunity. Neutrophil derived microparticles (NDMPs) have been shown to be the predominant microparticle present at infectious and inflamed foci in human models, however their effect on the immune response to inflammation and infection is sepsis has not been fully elucidated. As NDMPs may be a potential diagnostic and therapeutic target, we sought to determine the impact NDMPs on the immune response to a murine polymicrobial sepsis. We found that peritoneal neutrophil numbers, bacterial loads, and NDMPs were increased in our abdominal sepsis model. When NDMPs were injected into septic mice, we observed increased bacterial load, decreased neutrophil recruitment, increased expression of IL-10 and worsened mortality. Furthermore, the NDMPs express phosphatidylserine and are ingested by F4/80 macrophages via a Tim-4 and MFG-E8 dependent mechanism. Finally, upon treatment, NDMPs decrease macrophage activation, increase IL-10 release and decrease macrophage numbers. Altogether, these data suggest that NDMPs enhance immune dysfunction in sepsis by blunting the function of neutrophils and macrophages, two key cell populations involved in the early immune response to infection.

Keywords: Microparticles, sepsis, bacterial load, innate immunology

INTRODUCTION

Sepsis is defined by the clinical signs of a systemic inflammatory response in the setting of infection (1), however by this characterization, sepsis encompasses a spectrum of illness that ranges from minor signs and symptoms to organ dysfunction and shock (2). This definition of sepsis may be too broad and as it includes a heterogeneous group of patients who do not necessarily have the same disorder (1). Development of new therapies for sepsis has been difficult and over 25 trials of new sepsis treatments have failed (3, 4). This failure is partially due gaps in understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms driving sepsis (3), which in turn lead to stagnation in the development of novel and effective therapies (5). Despite efforts aimed at understanding the mechanisms underlying sepsis, as well as attempts to impact in the inflammatory cascade, mortality rates of this syndrome remain unacceptably high, ranging between 35–50% (6–8). This problem emphasizes the continued need for experimental and clinical research directed to understanding the pathophysiology of sepsis (9).

Sepsis-induced physiologic derangements are due largely to the presence, absence and extent of the host response to invading microorganisms rather than the direct effects of the microorganism itself (5). Immune system imbalance or paralysis can develop if the host response is marked by a dysregulation of pro- and counter-inflammatory mechanisms. One potential mediator in the pathophysiology of sepsis is the microparticle (MP). Microparticles are small, intact vesicles ranging from 0.1–1.0 μm that arise by blebbing off the cellular membrane during cell activation or apoptosis (10). This occurs in variety of cell types, including lymphocytes, myeloid cells, platelets and endothelial cells (10–12). Elevated MP populations are observed in inflammatory states in vivo (13), and MPs have been shown to have a both pro- and counter-inflammatory bioactive effects on the surrounding cellular milieu (13–15).

Microparticles act as bioactive effectors in a number of ways. They can exert biological effects to host cells by stimulating extra-cellular receptors of the target cell, or by transferring their contents, including proteins, lipids, mRNA, or microRNA, to the target cell (16). Additionally, circulating MPs can act upon extracellular proteins to enhance biological processes (17). Furthermore, phosphatidylserine (PS) expression observed on MPs (18) can serve as a signal for ingestion by surround phagocytes (19). Furthermore, uptake of MPs by phagocytes has been shown to change the lipid profile and inflammatory of state of ingesting cells (20).

While platelet derived microparticles are the most abundant and most well researched MP population (21), neutrophil-derived microparticles (NDMPs) are the predominant MP population generated at infected and inflamed foci in critically ill patients during sepsis (22). This is somewhat intuitive as neutrophils are an essential part of the innate immune system and act as first-responders by migrating to the origin of inflammation. Neutrophil-derived MPs are released from neutrophils as a result of a number of stimuli including bacteria (23, 24), endotoxin (25, 26), TNF-α (27–30), complement (31–33), platelet activating factor (26), and IL-8 (34), all of which are present in sepsis. Additionally, as neutrophils are recruited to the site of infection, are activated and undergo apoptosis 1–2 days after arrival, they are likely releasing MPs making an abdominal septic model an ideal setting for the study of effects of NDMPs.

Therefore, in the current study, we sought to determine the impact of NDMPs on the host immune response in the setting of sepsis. We hypothesized that increased NDMPs would be seen at the site of infection and their presence would impact the immune response to infection in a murine model of sepsis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

C57BL/6J male, wild-type (WT) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). For studies, 7-week-old male mice were obtained and allowed to acclimate for 1–2 weeks. The mice were housed in standard environmental conditions and were fed a commercial pellet diet and water ad libitum, per University of Cincinnati Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC # 08-09-19-10) guidelines.

Cecal ligation and puncture

Male mice between 8–9 weeks of age (22–26 g) were used in all experiments. Cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) operations were performed as previously described (35). Briefly, CLPs were performed between 7 a.m. and 10 a.m. EST after mice were anesthetized to effect by 2.5% isoflurane oxygen via chamber/facemask. Skin was shaved and disinfected with betadine solution. After 1 cm laparotomy, the latter 50% of the cecum was ligated with a 3-0 silk suture and punctured on the anti-mesenteric side with a 22-gauge needle. Bowel contents were then expressed via the puncture site to ensure full thickness perforation. Bowel continuity was not obstructed during the procedure. The cecum was replaced into the abdomen and the midline incision closed in two-layers with 4-0 silk suture. Animals were resuscitated with 1 mL of sterile saline and allowed to recover on a heating blanket for 60 minutes.

Peritoneal lavage

Peritoneal fluid was collected via standard peritoneal lavage techniques (36). Briefly, mice were sacrificed and immediately underwent aseptic preparation of the abdomen. Sterile saline (10 mL) was injected into the peritoneal cavity, allowed to percolate and the peritoneal fluid then aspirated.

Thioglycolate Adminstration and NDMP isolation

Mice underwent intra-peritoneal (IP) injections of 1 mL 3% thioglycolate (TGA) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) as previously described (37). Peritoneal lavage was performed 24 h after injection. Neutrophil derived microparticles were collected by peritoneal lavage. The lavage fluid underwent centrifugation at 450 x g for 10 minutes, supernatant of this sample underwent centrifugation at 10,000 x g for 10 minutes, followed by supernatant centrifugation at 25,000 x g for 30 minutes at 23°C to pellet the MPs. The final MP pellet was suspended in normal saline.

Flow cytometry

Single cell suspensions were prepared from peritoneal lavage samples or in vitro cell preparations. Cell counts were determined using a Coulter AcT 10 cell counter (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). Cells were suspended in FACS buffer (PBS with 1% bovine albumin and 0.1% azide) and nonspecific binding to cells was prevented by adding 5% rat serum (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and 1ul/sample of Fc Block (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA). These cells were stained with the following antibodies: Rat Anti-mouse Ly6G (BD Bioscience, Clone: 1A8, San Jose, CA), F4/80 (BD Bioscience), and FITC Annexin V (BD Bioscience). Neutrophils were characterized by expression of Ly6G, and peritoneal macrophages by expression of F4/80. FACS analsysis was conducted and analyzed using expression was determined using an Attune Acoustic Focusing Cytometer (Attune, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY).

Neutrophil parent cell identification of microparticles was conducted using rat Anti-mouse Ly6 labeling. Microparticle populations were sized on forward- and side-scatter gates using 0.5-, 0.9-, and 3.0-μm latex calibration beads as previously described (38).

In vivo impact of NDMP on macrophages

Neutrophil-derived MPs (NDMPs) isolated after thioglycolate treatment were labeled with 5-(and-6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate (CFSE) (lnvitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as previously described (22). Briefly, an equal volume of 10 mM CFSE was diluted to 1 : 5,000 in PBS just before use. MPs and CFSE were mixed in a 1:1 volume ratio and incubated for 8 minutes at room temperature on a rocker. An equal volume of FBS was added and allowed to sit for 1 minute at room temperature. Next, an equal amount of sterile K5 media was added to the mixture and centrifuged at 25,000g for 30 minutes to pellet MPs, enumerated by flow cytometry, and diluted to 80,000 MP/μL with normal saline. For in vivo experiments, 80 × 106 CFSE-labeled MPs were injected intraperitoneally into mice.

In vitro impact of NDMP on macrophages

For in vitro experiments, 8 × 106 CFSE-labeled MPs were co-incubated with 1 × 106 myeloid cells at 37°C for 3 hours. For ingestion analysis, 0.4% Trypan Blue in a 1:1 ratio was used for extracellular fluorescence quenching. In order to determine the mechanism by which macrophages were ingesting the NDMPs, these experiments were conducted with the addition of 500 ng/mL mouse recombinant MFG-E8 (R&D, Minneapolis, MN), 10 μg/mL anti-MFG-E8 (clone: 2422, MBL International Corporation, Des Plaines, IL), or 10 μg/mL anti-Tim4 (clone: RMT4-54, BioLegend, San Diego, CA).

ELISA

For in vivo cytokine levels, peritoneal fluid was collected from mice by peritoneal lavage as described above. Cytokine levels of IL-6 and IL-10 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and keritonocyte-derived chemokine (KC) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), were analyzed by ELISA according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Cytometric bead array analysis

For in vitro cytokine levels, peritoneal lavage cells were collected from untouched mice. Cells were then co-incubated with vehicle or NDMPs for one hour at 37°C. IL-10 levels were measured using a Cytometric Bead Array analysis kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), similar to methods described by Cook et al (39).

Bacterial counts

Bacterial counts were performed on aseptically collected peritoneal lavage samples. Samples were serially diluted in sterile saline and cultured on tryptic soy agar pour plates (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Plates were then incubated at 37°C for 24 hours at which time colony counts were performed (40).

Statistical methods

Statistical comparisons were performed using Students t-test (two groups), ANOVA with Dunnett post-hoc test or Tukey post-hoc test (more than two groups), and Kaplan Meier LogRank (survival). Graphpad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) was used for all statistical analyses. The mean and standard error of the mean were calculated in experiments containing multiple data points. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

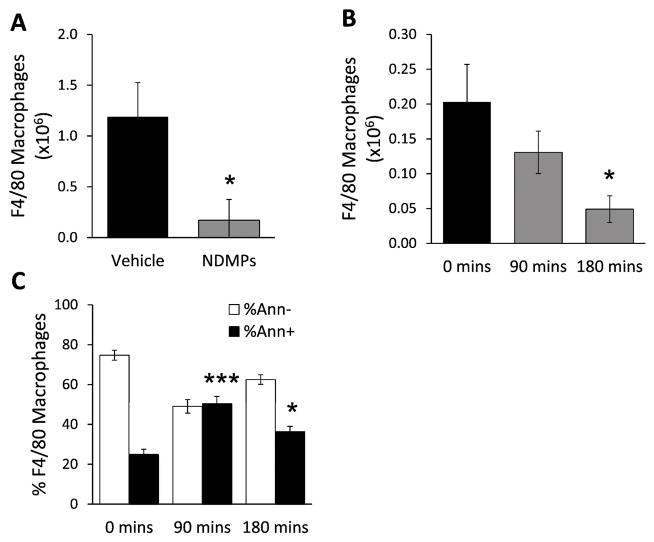

Intraperitoneal bacterial colonies, neutrophils and NDMPs are increased in sepsis

Previously, in patients with sepsis, NDMPs were shown to be the predominate microparticle generated at the infections focus (22). To evaluate if this was true in a murine model, intra-abdominal sepsis was induced via CLP and peritoneal lavage samples were collected at various time points following CLP. Lavage bacterial counts and neutrophil and NDMP populations were determined (n = 6 in each group). Bacterial counts were significantly increased as a function of time following CLP (Figure 1a). Intraperitoneal neutrophil numbers (Figure 1b) and NDMPs (Figure 1c) also increased as a function of time over a 24-hour period.

FIGURE 1. Bacterial load, peritoneal neutrophils, and NDMPs increase after CLP.

BL6 mice underwent CLP as described in the methods and were sacrificed at the indicated times. Peritoneal lavage was collected at time of death. Peritoneal (A) bacterial counts (B) neutrophils and (C) NDMPs were enumerated as described in the methods. Data is expressed as mean ± SEM. Sample size is 6 in each group. Significance was determined using ANOVA analysis and Dunnett post-hoc test. * p<0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p<0.001 compared to time = 0.

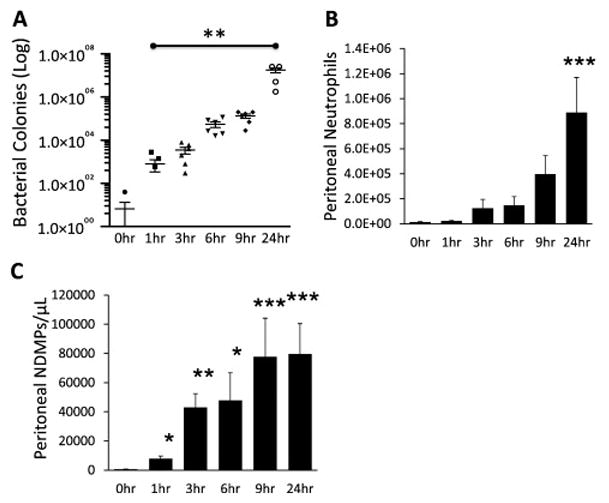

NDMPs increase mortality in septic mice

To investigate whether NDMPs could mitigate sepsis-induced mortality, NDMPs were isolated, combined and enumerated from septic donor mice (isolated 24 hours after CLP). Recipient mice received 108 NDMPs at the time of CLP with survival assessed over a 10-day period. Vehicle treated mice had a significantly higher survival (Figure 2). Altogether, NDMPs contributed to increased mortality.

FIGURE 2. NDMPs increase mortality in septic mice.

BL6 mice underwent CLP and injection with vehicle or NDMPs as described in the methods. Survival of vehicle injected and CLP-elicited NDMP injected CLP mice. Data is expressed as mean ± SEM. Sample size is 20 in each group. * p<0.05 compared to vehicle treated, Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used to determine difference in survival between groups.

Increased peritoneal bacterial counts and counter-inflammatory mediators are seen with NDMP treatment of septic mice

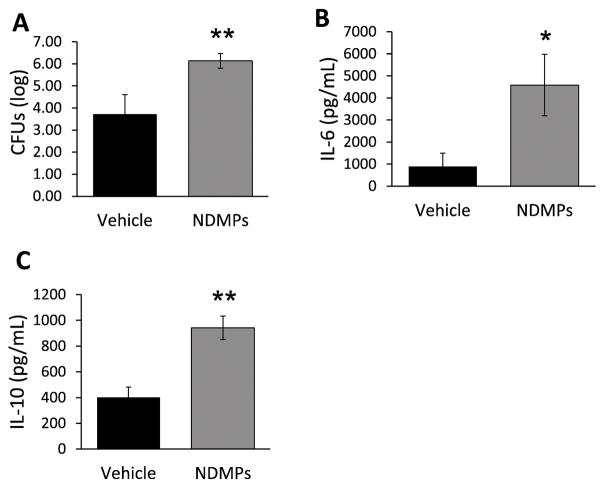

To determine the underpinnings of the increased mortality in the NDMP treated septic mice, we evaluated intraperitoneal bacterial loads, and IL-6 and IL-10 levels 24 hours after CLP in vehicle vs. NDMP-treated mice. The peritoneal bacterial loads were increased by two orders of magnitude in the NDMP treated mice compared with vehicle (Figure 3a). Systemic bacterial loads were also greater in the NDMP treated mice (data not shown). Peritoneal IL-6 levels were measured at 6 hours as they are known to correlate with severity of sepsis (41), and as shown in Figure 3b, levels of IL-6 were significantly higher in NDMP treated mice. Conversely, peritoneal IL-10 levels, a known counter-inflammatory cytokine (42), were also increased 24 hours after CLP in NDMP treated mice (Figure 3c). Taken together, these data suggest that NDMPs influenced the host response with increased counter-inflammatory cytokine accumulation and bacterial load.

FIGURE 3. NDMPs decrease bacterial clearance and increase secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines.

BL6 mice underwent CLP and injection with vehicle or TGA-elicited NDMPs and were sacrificed at 24 hours and peritoneal lavage was performed. Peritoneal (A) CFUs, (B) IL-6 levels and (C) IL-10 levels (pg/mL) were determined as described in the methods. Data is expressed as mean ± SEM. Sample size is 11 in each group. Significance was determined using student t-test. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 compared to vehicle.

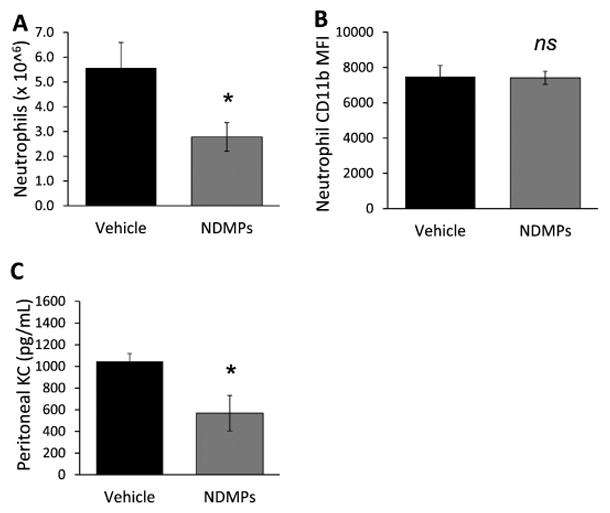

NDMPs decrease neutrophil recruitment in septic mice

To evaluate the effect of NDMPs on neutrophils and macrophages in septic mice, WT mice underwent CLP and were injected with vehicle or NDMPs. We observed at 24 hours, peritoneal neutrophil numbers were significantly lower with NDMP treatment vs. control (Figure 4a). To evaluate if in addition to neutrophil numbers, neutrophil function was diminished, we compared expression of the activation marker CD11b on neutrophils 24 hour after CLP in vehicle and NDMP-treated mice. As shown in Figure 4b, and no significant difference in CD11b expression was seen. To determine whether this effect was due to diminished neutrophil chemotactic levels, intraperitoneal KC levels were evaluated at 4 hours following CLP with vehicle or NDMP treatment. KC levels were significantly lower with NDMP treatment after CLP (Figure 4c). Thus, although NDMPs diminish neutrophil recruitment via decreased chemotactic signaling, they do not appear to alter neutrophil activation.

FIGURE 4. NDMPs decrease neutrophil recruitment but do not diminish neutrophil activation in septic mice after CLP.

Mice were subjected to CLP and treatment with vehicle or NDMPs and peritoneal lavage performed. Enumeration of peritoneal (A) neutrophils populations and (B) neutrophil CD11b mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was determined 24 hours after CLP as described in the methods. (C) Peritoneal KC levels (pg/mL) were determined 4 hours after CLP. Data is expressed as mean ± SEM. Sample size is 6–7 in each group. Significance was determined using student t-test. * p < 0.05 compared to vehicle. ns = not significant

NDMPs are ingested by F4/80 macrophages

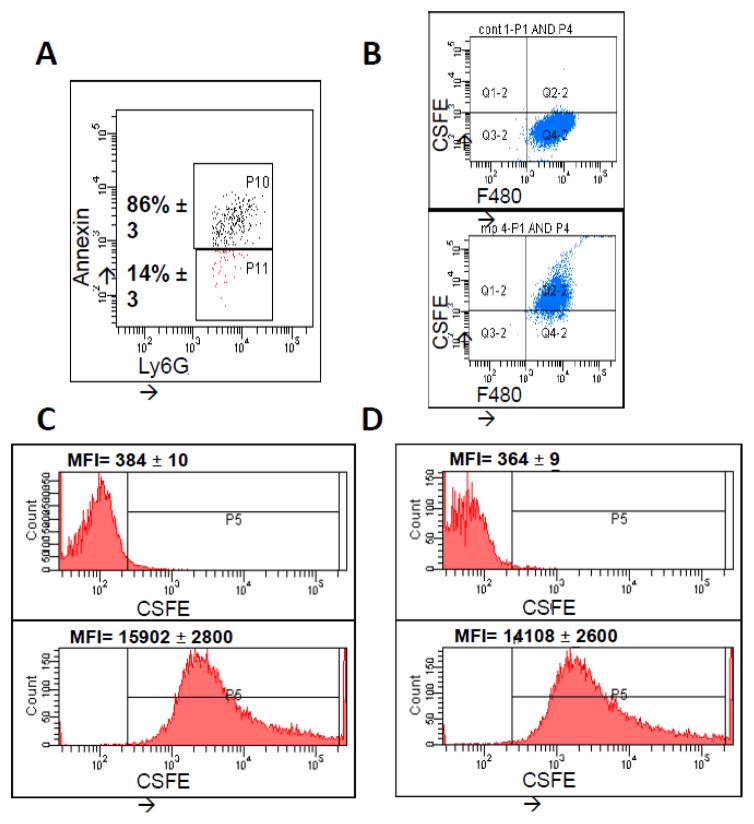

Phosphatidylserine expression serves as signal for apoptosis (43), as well as a signal for uptake by surrounding macrophages (19). As various MP populations have been described as expressing PS (18, 44, 45), we next sought to determine whether NDMPs also expressed PS in our model. Isolated Ly6G+ NDMPs were co-labeled with Annexin V. Figure 5a is representative of PS expression of TGA-elicited NDMPs, and demonstrates that ~86% of NDMPs are PS positive. We next evaluated NDMP uptake by phagocytes. Figure 5b is a representative flow diagram demonstrating association of peritoneal F4/80 macrophages with CSFE-labeled NDMPs in vivo. Peritoneal fluid was collected from naive mice 1 hour after injection with non-CSFE-labeled (Figure 5b, top) and CSFE-labeled (Figure 5b, bottom) NDMPs. To differentiate between NDMP association and NDMP phagocytosis, trypan blue was used to quench extracellular fluorescence (Figure 5c, 5d). Non-CSFE-labeled NDMPs (Figure 5c,d, top) and CSFE-labeled NDMPs (Figure 5c,d, bottom) were co-incubated non-trypan blue-labeled (Figure 5c) and trypan-blue labeled (Figure 5d) peritoneal myeloid cells from naive mice for 1 hour. Treatment with CSFE-labeled NDMPs of quenched, trypan blue-labeled myeloid cells demonstrates persistent CSFE uptake, indicating NDMP endocytosis (46). Taken together, these data demonstrate that the majority of NDMPs express PS, which likely serves as an uptake signal to surrounding phagocytes, specifically F4/80 macrophages.

FIGURE 5. NDMPs are ingested by F4/80 macrophages.

Mice were injected with TGA and peritoneal lavage performed 24 hours following injection. (A) Representative flow cytometry analysis of peritoneal NDMPs. Mice were then injected with non-CSFE labeled and CSFE labeled TGA-elicited NDMPs and peritoneal lavage samples collected one hour after injection. Representative flow cytometric analysis of (B) F4/80 macrophage uptake of NDMPs, non-CSFE labeled NDMPs (top) and CSFE labeled TGA-elicited NDMPs (bottom) and (C) mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of non-trypan blue labeled peritoneal myeloid cells incubated 1 hour with unlabeled NDMPs (top) and CSFE labeled NDMPs (bottom). This was then repeated with and without trypan blue quenched macrophages as described in the methods. (D) MFI of trypan blue quenched peritoneal myeloid cells incubated 1 hour with unlabeled NDMPs (top) and CSFE labeled NDMPs (bottom), demonstrating NDMP-Myeloid cell association. Sample size is 4 in each group. MFI expressed as mean ± SEM.

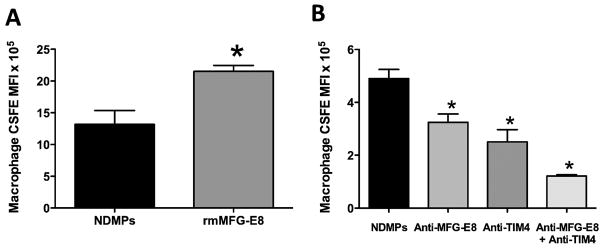

Macrophage phagocytosis of NDMPs is via a MFG-E8 and TIM4 dependent mechanism

Previous research has demonstrated that macrophages can engulf PS-expressing cells through a milk fat globule epidermal growth factor VIII (MFG-E8) and T cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain-containing molecule 4 (Tim4) mechanism (47, 48). We therefore hypothesized that macrophages engulf NDMPs through a similar mechanism. In order to investigate this, we isolated naïve F4/80 cells and incubated them with CSFE labeled NDMPs in the presence of recombinant MFG-E8 (rmMFG-E8), anti-MFG-E8, anti-Tim4 and a combination of anti-MFG-E8 and anti-Tim4. In our gain of function experiment with the addition of rmMFG-E8, we saw a significant increase in macrophage CSFE expression and therefore increased NDMP phagocytosis compared to incubation with NDMPs alone (Figure 6a). Figure 6b depicts the results of our loss of function experiments with the addition of MFG-E8 and Tim4 blocking agents. Blockade of MFG-E8 led to a 33% decrease, blockade of Tim4 to a 50% decrease and blockade of both MFG-E8 and Tim4 to a 75% decrease in macrophage CSFE expression compared to incubation with NDMPs alone. This suggests that the phagocytosis of NDMPs is via a MFG-E8 and Tim4 dependent mechanism, similar to that seen with apoptotic cells by Toda et al (47).

FIGURE 6. Phagocytosis of NDMPs by macrophages is via a MFG-E8 and Tim4 dependent mechanism.

F4/80 macrophages were incubated for three hours with CSFE labeled NDMPs and vehicle or (A) 500 ng/mL rmMFG-E8 or (B) 10 μg/mL anti-MFG-E8, 10 μg/mL anti-Tim4 or anti-MFG-E8 and anti-Tim4 and CSFE expression determined. and Data is expressed as mean ± SEM. Sample size is 3 or 4 for each group and representative of 2 experiments with similar trends. Significance was determined using student t-test (A) and ANOVA analysis with Dunnett post-hoc test (B). * p < 0.05 compared to NDMPs + vehicle.

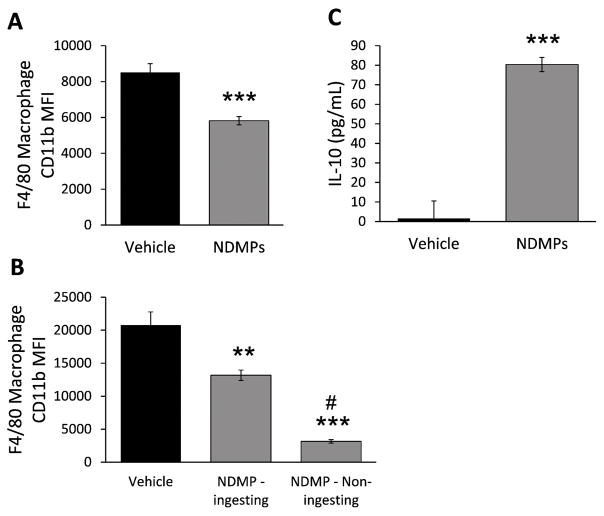

NDMPs decrease macrophage activation and increase secretion of IL-10

To determine the effects of NDMP phagocytosis on macrophages, we evaluated expression of CD11b on peritoneal resident F4/80 macrophages 24 hour after CLP in vehicle and NDMP treated mice. Figure 7a demonstrates a significant decrease in peritoneal macrophage activation, as determined by CD11b expression, in NDMP treated mice. To confirm that NDMPs were blocking macrophage activation, peritoneal myeloid cells from naive mice were incubated with CSFE-labeled NDMPs for one hour. Expression of CD11b on F4/80 macrophages was compared between cells that ingested NDMPs (expressed CSFE) and cells that did not ingest NDMPs (no CSFE expression). F4/80 macrophages that ingested NDMPs had significantly less activation than vehicle treated cells, confirming our in vivo results. Additionally, bystander F4/80 macrophages, those that did not ingest NDMPs, had a further reduction in cellular activation compared to vehicle and NDMP-ingesting cells (Figure 7b). Next, cytometric bead array analysis was used to determine the effect NDMPs of IL-10 cytokine levels in vitro. Figure 7c demonstrates that after 1 hour, peritoneal myeloid cells from naive mice co-incubated with NDMPs produce significantly higher levels of IL-10 compared to vehicle treated mice. This finding is consistent with the effects of NDMPs seen at 24 hours in vivo (Figure 2d). Thus, NDMPs worsen immune suppression by decreasing macrophage activation and increasing secretion of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10.

FIGURE 7. NDMPs decrease macrophage activation and increase expression of IL-10.

Mice were subjected to CLP with vehicle or NDMP injection and peritoneal lavage cells collected 24 hours after CLP and (A) CD11b MFI on F4/80 macrophages determined. Peritoneal myeloid cells from untouched mice were then co-incubated with vehicle or TGA-elicited NDMPs for 3 hours with (B) CD11b MFI on F4/80 macrophages determined on CSFE expressing (representing NDMP uptake) and non-CSFE expressing (representing non-ingesting) cells and (C) IL-10 cytokine levels determined. Data is expressed as mean ± SEM. Samples size is 4–7 per group. Significance was determined using student t-test (*** p < 0.001, compared to vehicle) for A and C. Significance was determined using ANOVA with Tukey post-test ** p < 0.01 compared to vehicle, *** p < 0.001 compared to vehicle, # p < 0.001 compared to NDMP - ingesting cells for B.

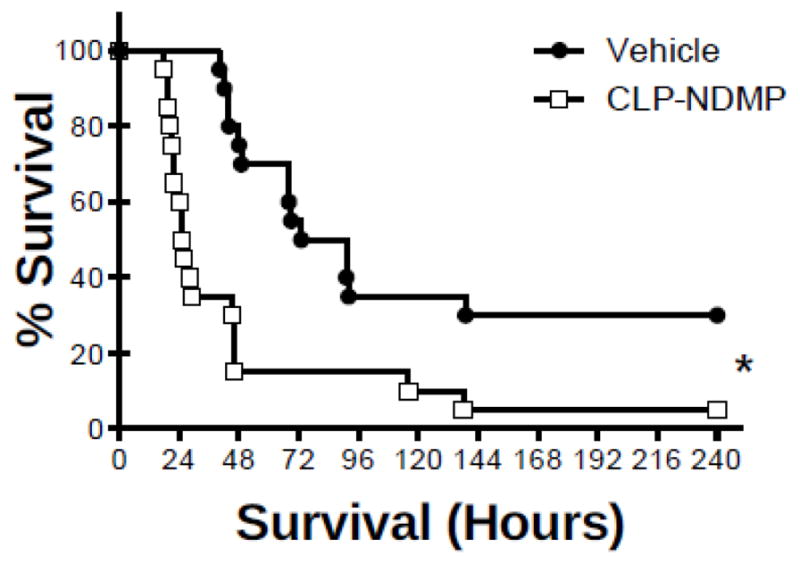

NDMPs treatment reduces macrophage numbers and increases Annexin V expression

In addition to decreased macrophage activation one hour after NDMP treatment, we also observed a trend of decreased peritoneal F4/80 macrophage numbers. To more fully investigate this, peritoneal F4/80 cell numbers were evaluated by flow cytometry three hours from septic mice treated with either vehicle or NDMPs. Septic mice treated with NDMPs were found to have a significantly lower number of F4/80 cells compared to vehicle (Figure 8a). To determine whether NDMPs were impacting this alteration in peritoneal macrophage populations in vitro, peritoneal cells were isolated and co-incubated with NDMPs or vehicle (normal saline). Subsequently, F4/80 macrophages numbers were determined after 0, 90 and 180 minutes. The data demonstrate that F4/80 cell numbers were decreased temporally, and at 180 minutes were significantly reduced (Figure 8b). Next, PS expression was evaluated on peritoneal-isolated F4/80 macrophages treated with either vehicle or NDMPs. After 1.5 and 3 hours, PS expression on macrophages was significantly increased (Figure 8c). Thus, NDMP treatment decreased macrophage cell numbers and increased Annexin V expression.

FIGURE 8. NDMP treatment reduces macrophage numbers and increase Annexin V expression.

BL6 mice underwent CLP and injection with vehicle or TGA-elicited NDMPs and were sacrificed at 3 hours, and peritoneal (A) F4/80 cells enumerated. (B–C) Untouched BL6 mice were injected with TGA-elicited NDMPs and sacrificed at 0, 90, and 180 minutes and peritoneal lavage was performed. Enumeration of (B) F4/80 macrophages and (C) percentage of peritoneal F4/80 macrophages expressing Annexin V was determined. Data is expressed as mean ± SEM. Sample size is 4–5 per group and representative of 2 independent experiments. Significance was determined using (A, D) student t-test or (B–C) ANOVA analysis and Dunnett post-hoc test. * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001 compared to time 0 or vehicle.

Discussion

This study demonstrates NDMPs can influence the host response to sepsis. We first observed that NDMPs increase during the first 24 hours of sepsis. To determine the potential impact, we determined that mice given NDMPs exogenously at the time of CLP-surgery had increased mortality. Furthermore, NDMP administration was associated with increased bacterial loads and IL-10 levels. Complementary to this, the NDMP treated mice also manifested decreased neutrophil chemotactic levels and numbers potentially leading to reduced bacterial clearance. We further observed that NDMPs are ingested by resident macrophages through a MFG-E8 and TIM-4 dependent mechanism. Subsequent to NDMP exposure, macrophages also demonstrate both a decrease in cellular activation and numbers. In summary, these findings demonstrate that NDMPs enhance the counter-inflammatory response, impair the ability to clear infection in sepsis, and contribute to sepsis mortality.

Overall, our finding of an NDMP-dependent impairment of the immune response is consistent with the emerging body of literature regarding the immunosuppression and immunoparalysis observed during sepsis (49). Inflammatory cytokine secretion is decreased and expansion of suppressor cell populations is increased in patients who die with sepsis (50). Additionally, autopsy findings in approximately 80% patients that died from septic shock demonstrated continuous septic foci at the time of death, despite more than one week of appropriate therapy (51). Using an air pouch model for in vivo neutrophil migration, it was observed that NDMPs contain a relatively high amount anti-inflammatory protein annexin 1which acts to diminished neutrophil recruitment (52). In other studies, NDMPs have also been shown to influence macrophages by decreasing production of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α, while increasing production of counter-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β1 (31, 53). NDMPs have also been shown to decrease IFN-γ and TNF-α production while enhancing TGF-β1 in natural killer (NK) cells (54). The presence of NDMPs in areas inflammatory foci in humans (22) and in our murine model, in conjunction with the decreased bacterial clearance seen in NDMP treated mice in this study, points to a mechanism that could potentially contribute to persistent infection in sepsis non-survivors.

Another finding in our study is decreased macrophages activation after the ingestion of NDMPs. Further, the macrophages that do not ingest NDMPs are even less activated. However, there is not a complete consensus of the impact of MP ingestion in the literature. Marques-da-Silva et al demonstrated increased expression of CD11b after macrophage ingestion of apoptotic bodies (55). While not in a sepsis model, Chen et al demonstrated similar findings with an increase in CD11b expression in dendritic cells after ingestion of apoptotic astrocytes (56). Previously, we demonstrated that NDMPs isolated from human bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples, incubated with THP-1 monocytes slightly increased expression of HLA-DR, CD80, and CD86 in ingesting cells, while cells that did not ingest NDMPs showed decreased expression of these activation markers (22). Conversely, Dalli et al demonstrated uptake by of apoptotic neutrophils and NDMPs by macrophages resulted in an increase in macrophage expression of pro-resolving mediators (20). Additionally, NDMPs have been observed to reduce macrophage phagocytosis and to stimulate T-cell proliferation (53). In line with this, neutrophil exudates have potent anti-inflammatory actions and can regulate the specific microRNA expression involved in inflammatory resolution (57). Our finding, that cells which did not ingest NDMPs were less activated, is in line with Gasser et al, in which they demonstrated that macrophages did not require ingestion of NDMPs to produce an anti-inflammatory response (31). We speculate a potential explanation of these findings is that uptake of NDMPs initially activates macrophages, however, macrophages then begin secreting high levels of pro-resolving mediators. Alternatively, the differences in MP lipid, protein, and RNA content may drive differing macrophage responses. Of note, in our studies, MP-ingested macrophage mediators can then work in both a paracrine and an autocrine manner to alter macrophage activation.

We postulate that PS expression on NDMPs plays a key role in its immune response mediation. Under resting conditions, PS is almost exclusively located in the inner monolayer of the membrane (58). As a cell undergoes apoptosis, PS exposure increases on the outer membrane of the cell, signaling removal of apoptotic bodies by phagocytic cells (59). Phosphatidylserine expression on apoptotic cells, while pro-coagulant (60), can also induce an anti-inflammatory response in phagocytes (61). Furthermore, exposure of PS on the surface of NDMPs was found to independently contribute to early phase anti-inflammatory effects on macrophages (31). Similarly, the anti-inflammatory effects of NDMPs observed on NK cells by Pliyev et al, was attenuated by blockade of phosphatidylserine exposure on NDMPs (54). These data together suggest that PS plays an important role in NDMP up-take by cells and their impact on phagocytes.

Fluidity of the plasma membrane is partly modulated by the ratio of certain membrane lipids, and our finding of high relative ceramide concentration in NDMPs is consistent with emerging literature (62). Interestingly, MP uptake has been shown to cause a perturbation of the endocytosing macrophage lipid membrane homeostasis (63). Coinciding with membrane alteration, MPs have been also shown to induce cellular apoptosis in a dose dependent manner (15, 64). Huber et al demonstrated that treatment of macrophages with an acid sphingomyelinase inhibitor that reduces ceramide production, led to decreased MP-induced apoptosis in phagocytes (64). Similarly, exosomes enriched in ceramide are found to induce apoptosis in ingesting cells via a ceramide dependent mechanism (65). We postulate that the increased apoptosis in macrophages in our study may be due to high ceramide levels the NDMP populations. Altogether, we speculated that apoptotic neutrophils release ceramide-rich that are then ingested by macrophages. We postulated that at this point, either macrophages underwent cell death and/or migrated to lymphoid tissue. To discriminate between these two possibilities, we analyzed blood, spleen, and mesenteric lymph node for CFSE-MP fluorescing macrophages by flow cytometry. However, we were unable to detect these (data not shown). Further, to prevent macrophage migration, peritoneal cells were isolated and co-incubated with NDMPs or vehicle (normal saline) in vitro. The data demonstrate that F4/80 cell numbers were significantly reduced. Next, we observed PS expression on these cells. Thus, NDMP treatment decreased macrophage cell numbers and increased Annexin V expression, potentially through a ceramide-dependent manner.

Sepsis is more lethal in elderly patients with age being an independent mortality predictor (66, 67). However, in the current study, we used 8–9 week old mice. It would be of interest to similarly enumerate NDMPs from elderly septic mice. Future studies could also include whether NDMPs from old mice are ingested by macrophages in a similar Tim-4/MFG-E8 dependent manner. Finally, a comparison of proteins, RNA and lipids between NDMPs from young and older septic mice may yield notable differences.

A potential limitation to this study is the choice of controls for the NDMP treated mice. We used the NDMP vehicle, normal saline, as the control. However, as already stated, NDMPs are made up of a huge number of biologically active molecules. In more ideal future experiments, the impact of a single biological molecule within the extracellular vesicle will be tested during sepsis. An example of this type of study would be the injection of extracellular vesicles isolated from either WT or miR-223-deficient mice into septic mice. With this technique, the authors were able to precisely determine how extracellular vesicle miR-223 impact the host response to sepsis (68). Here, had they been available and viable, the ideal control would have been NDMPs isolated from PS-deficient mice.

Highlights.

We found that peritoneal neutrophil numbers, bacterial loads, and NDMPs were increased in our abdominal sepsis model.

When NDMPs were injected into septic mice, we observed increased bacterial load, decreased neutrophil recruitment, increased expression of IL-10 and worsened mortality.

The NDMPs express phosphatidylserine and are ingested by F4/80 macrophages via a Tim-4 and MFG-E8 dependent mechanism.

Incubation with NDMPs can decrease macrophage activation, increase IL-10 release and decrease macrophage numbers.

NDMPs influence immune dysfunction in sepsis by blunting the function of neutrophils and macrophages, two key cell populations involved in the early immune response to infection.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The project described was supported by Award Number R01 GM100913 (CCC) and T32 GM08478 (BLJ, PSP, TCR) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ulloa L, Brunner M, Ramos L, Deitch EA. Scientific and clinical challenges in sepsis. Current pharmaceutical design. 2009;15:1918–1935. doi: 10.2174/138161209788453248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lever A, Mackenzie I. Sepsis: definition, epidemiology, and diagnosis. Bmj. 2007;335:879–883. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39346.495880.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hotchkiss RS, Coopersmith CM, McDunn JE, Ferguson TA. The sepsis seesaw: tilting toward immunosuppression. Nature medicine. 2009;15:496–497. doi: 10.1038/nm0509-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deans KJ, Haley M, Natanson C, Eichacker PQ, Minneci PC. Novel therapies for sepsis: a review. The Journal of trauma. 2005;58:867–874. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000158244.69179.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsuda A, Jacob A, Wu R, Aziz M, Yang WL, Matsutani T, Suzuki H, Furukawa K, Uchida E, Wang P. Novel therapeutic targets for sepsis: regulation of exaggerated inflammatory responses. Journal of Nippon Medical School = Nippon Ika Daigaku zasshi. 2012;79:4–18. doi: 10.1272/jnms.79.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antonopoulou A, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ. Immunomodulation in sepsis: state of the art and future perspective. Immunotherapy. 2011;3:117–128. doi: 10.2217/imt.10.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaya S. Adventure of recombinant human activated protein C in sepsis and new treatment hopes on the horizon. Recent patents on inflammation & allergy drug discovery. 2012;6:159–164. doi: 10.2174/187221312800166822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Opal SM. The evolution of the understanding of sepsis, infection, and the host response: a brief history. Critical care nursing clinics of North America. 2011;23:1–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stahl O, Loffler B, Haier J, Mardin WA, Mees ST. Mimicry of human sepsis in a rat model--prospects and limitations. The Journal of surgical research. 2013;179:e167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ardoin SP, Shanahan JC, Pisetsky DS. The role of microparticles in inflammation and thrombosis. Scandinavian journal of immunology. 2007;66:159–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2007.01984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hargett LA, Bauer NN. On the origin of microparticles: From “platelet dust” to mediators of intercellular communication. Pulmonary circulation. 2013;3:329–340. doi: 10.4103/2045-8932.114760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dengler V, Downey GP, Tuder RM, Eltzschig HK, Schmidt EP. Neutrophil intercellular communication in acute lung injury. Emerging roles of microparticles and gap junctions. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2013;49:1–5. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0472TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Distler JH, Pisetsky DS, Huber LC, Kalden JR, Gay S, Distler O. Microparticles as regulators of inflammation: novel players of cellular crosstalk in the rheumatic diseases. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2005;52:3337–3348. doi: 10.1002/art.21350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jodo S, Xiao S, Hohlbaum A, Strehlow D, Marshak-Rothstein A, Ju ST. Apoptosis-inducing membrane vesicles. A novel agent with unique properties. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:39938–39944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Distler JH, Huber LC, Hueber AJ, Reich CF, 3rd, Gay S, Distler O, Pisetsky DS. The release of microparticles by apoptotic cells and their effects on macrophages. Apoptosis : an international journal on programmed cell death. 2005;10:731–741. doi: 10.1007/s10495-005-2941-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valadi H, Ekstrom K, Bossios A, Sjostrand M, Lee JJ, Lotvall JO. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nature cell biology. 2007;9:654–659. doi: 10.1038/ncb1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geddings JE, Mackman N. Tumor-derived tissue factor-positive microparticles and venous thrombosis in cancer patients. Blood. 2013;122:1873–1880. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-460139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freyssinet JM, Toti F. Formation of procoagulant microparticles and properties. Thrombosis research. 2010;125(Suppl 1):S46–48. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Somersan S, Bhardwaj N. Tethering and tickling: a new role for the phosphatidylserine receptor. The Journal of cell biology. 2001;155:501–504. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200110066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalli J, Serhan CN. Specific lipid mediator signatures of human phagocytes: microparticles stimulate macrophage efferocytosis and pro-resolving mediators. Blood. 2012;120:e60–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-423525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lacroix R, Plawinski L, Robert S, Doeuvre L, Sabatier F, Martinez de Lizarrondo S, Mezzapesa A, Anfosso F, Leroyer AS, Poullin P, Jourde N, Njock MS, Boulanger CM, Angles-Cano E, Dignat-George F. Leukocyte- and endothelial-derived microparticles: a circulating source for fibrinolysis. Haematologica. 2012;97:1864–1872. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.066167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prakash PS, Caldwell CC, Lentsch AB, Pritts TA, Robinson BR. Human microparticles generated during sepsis in patients with critical illness are neutrophil-derived and modulate the immune response. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2012;73:401–406. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31825a776d. discussion 406–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Timar CI, Lorincz AM, Csepanyi-Komi R, Valyi-Nagy A, Nagy G, Buzas EI, Ivanyi Z, Kittel A, Powell DW, McLeish KR, Ligeti E. Antibacterial effect of microvesicles released from human neutrophilic granulocytes. Blood. 2013;121:510–518. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-431114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi J, Fujieda H, Kokubo Y, Wake K. Apoptosis of neutrophils and their elimination by Kupffer cells in rat liver. Hepatology. 1996;24:1256–1263. doi: 10.1053/jhep.1996.v24.pm0008903407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watanabe J, Marathe GK, Neilsen PO, Weyrich AS, Harrison KA, Murphy RC, Zimmerman GA, McIntyre TM. Endotoxins stimulate neutrophil adhesion followed by synthesis and release of platelet-activating factor in microparticles. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:33161–33168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305321200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pluskota E, Woody NM, Szpak D, Ballantyne CM, Soloviev DA, Simon DI, Plow EF. Expression, activation, and function of integrin alphaMbeta2 (Mac-1) on neutrophil-derived microparticles. Blood. 2008;112:2327–2335. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-127183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson BL, 3rd, Goetzman HS, Prakash PS, Caldwell CC. Mechanisms underlying mouse TNF-alpha stimulated neutrophil derived microparticle generation. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2013;437:591–596. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.06.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daniel L, Fakhouri F, Joly D, Mouthon L, Nusbaum P, Grunfeld JP, Schifferli J, Guillevin L, Lesavre P, Halbwachs-Mecarelli L. Increase of circulating neutrophil and platelet microparticles during acute vasculitis and hemodialysis. Kidney international. 2006;69:1416–1423. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hong Y, Eleftheriou D, Hussain AA, Price-Kuehne FE, Savage CO, Jayne D, Little MA, Salama AD, Klein NJ, Brogan PA. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies stimulate release of neutrophil microparticles. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2012;23:49–62. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011030298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nusbaum P, Laine C, Bouaouina M, Seveau S, Cramer EM, Masse JM, Lesavre P, Halbwachs-Mecarelli L. Distinct signaling pathways are involved in leukosialin (CD43) down-regulation, membrane blebbing, and phospholipid scrambling during neutrophil apoptosis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:5843–5853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413405200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gasser O, Schifferli JA. Activated polymorphonuclear neutrophils disseminate anti-inflammatory microparticles by ectocytosis. Blood. 2004;104:2543–2548. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgan BP, Dankert JR, Esser AF. Recovery of human neutrophils from complement attack: removal of the membrane attack complex by endocytosis and exocytosis. Journal of immunology. 1987;138:246–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campbell AK, Morgan BP. Monoclonal antibodies demonstrate protection of polymorphonuclear leukocytes against complement attack. Nature. 1985;317:164–166. doi: 10.1038/317164a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mesri M, Altieri DC. Leukocyte microparticles stimulate endothelial cell cytokine release and tissue factor induction in a JNK1 signaling pathway. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:23111–23118. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Unsinger J, McGlynn M, Kasten KR, Hoekzema AS, Watanabe E, Muenzer JT, McDonough JS, Tschoep J, Ferguson TA, McDunn JE, Morre M, Hildeman DA, Caldwell CC, Hotchkiss RS. IL-7 promotes T cell viability, trafficking, and functionality and improves survival in sepsis. Journal of immunology. 2010;184:3768–3779. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kasten KR, Muenzer JT, Caldwell CC. Neutrophils are significant producers of IL-10 during sepsis. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2010;393:28–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.01.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Midura EF, Prakash PS, Johnson BL, 3rd, Rice TC, Kunz N, Caldwell CC. Impact of caspase-8 and PKA in regulating neutrophil-derived microparticle generation. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2016;469:917–922. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robert S, Poncelet P, Lacroix R, Arnaud L, Giraudo L, Hauchard A, Sampol J, Dignat-George F. Standardization of platelet-derived microparticle counting using calibrated beads and a Cytomics FC500 routine flow cytometer: a first step towards multicenter studies? Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH. 2009;7:190–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cook EB, Stahl JL, Lowe L, Chen R, Morgan E, Wilson J, Varro R, Chan A, Graziano FM, Barney NP. Simultaneous measurement of six cytokines in a single sample of human tears using microparticle-based flow cytometry: allergics vs. non-allergics. Journal of immunological methods. 2001;254:109–118. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(01)00407-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kasten KR, Tschop J, Goetzman HS, England LG, Dattilo JR, Cave CM, Seitz AP, Hildeman DA, Caldwell CC. T-cell activation differentially mediates the host response to sepsis. Shock. 2010;34:377–383. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181dc0845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ebong S, Call D, Nemzek J, Bolgos G, Newcomb D, Remick D. Immunopathologic alterations in murine models of sepsis of increasing severity. Infection and immunity. 1999;67:6603–6610. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6603-6610.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scumpia PO, Moldawer LL. Biology of interleukin-10 and its regulatory roles in sepsis syndromes. Critical care medicine. 2005;33:S468–471. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000186268.53799.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Demchenko AP. The change of cellular membranes on apoptosis: fluorescence detection. Experimental oncology. 2012;34:263–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morel O, Morel N, Jesel L, Freyssinet JM, Toti F. Microparticles: a critical component in the nexus between inflammation, immunity, and thrombosis. Seminars in immunopathology. 2011;33:469–486. doi: 10.1007/s00281-010-0239-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martinez MC, Tesse A, Zobairi F, Andriantsitohaina R. Shed membrane microparticles from circulating and vascular cells in regulating vascular function. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2005;288:H1004–1009. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00842.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patino T, Soriano J, Barrios L, Ibanez E, Nogues C. Surface modification of microparticles causes differential uptake responses in normal and tumoral human breast epithelial cells. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11371. doi: 10.1038/srep11371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Toda S, Hanayama R, Nagata S. Two-step engulfment of apoptotic cells. Molecular and cellular biology. 2012;32:118–125. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05993-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aziz M, Jacob A, Matsuda A, Wang P. Review: milk fat globule-EGF factor 8 expression, function and plausible signal transduction in resolving inflammation. Apoptosis : an international journal on programmed cell death. 2011;16:1077–1086. doi: 10.1007/s10495-011-0630-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hutchins NA, Unsinger J, Hotchkiss RS, Ayala A. The new normal: immunomodulatory agents against sepsis immune suppression. Trends Mol Med. 2014;20:224–233. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boomer JS, To K, Chang KC, Takasu O, Osborne DF, Walton AH, Bricker TL, Jarman SD, 2nd, Kreisel D, Krupnick AS, Srivastava A, Swanson PE, Green JM, Hotchkiss RS. Immunosuppression in patients who die of sepsis and multiple organ failure. Jama. 2011;306:2594–2605. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Torgersen C, Moser P, Luckner G, Mayr V, Jochberger S, Hasibeder WR, Dunser MW. Macroscopic postmortem findings in 235 surgical intensive care patients with sepsis. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2009;108:1841–1847. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318195e11d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dalli J, Norling LV, Renshaw D, Cooper D, Leung KY, Perretti M. Annexin 1 mediates the rapid anti-inflammatory effects of neutrophil-derived microparticles. Blood. 2008;112:2512–2519. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-140533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eken C, Gasser O, Zenhaeusern G, Oehri I, Hess C, Schifferli JA. Polymorphonuclear neutrophil-derived ectosomes interfere with the maturation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Journal of immunology. 2008;180:817–824. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.2.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pliyev BK, Kalintseva MV, Abdulaeva SV, Yarygin KN, Savchenko VG. Neutrophil microparticles modulate cytokine production by natural killer cells. Cytokine. 2014;65:126–129. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marques-da-Silva C, Burnstock G, Ojcius DM, Coutinho-Silva R. Purinergic receptor agonists modulate phagocytosis and clearance of apoptotic cells in macrophages. Immunobiology. 2011;216:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen Z, Moyana T, Saxena A, Warrington R, Jia Z, Xiang J. Efficient antitumor immunity derived from maturation of dendritic cells that had phagocytosed apoptotic/necrotic tumor cells. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2001;93:539–548. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li Y, Dalli J, Chiang N, Baron RM, Quintana C, Serhan CN. Plasticity of leukocytic exudates in resolving acute inflammation is regulated by MicroRNA and proresolving mediators. Immunity. 2013;39:885–898. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morel O, Jesel L, Freyssinet JM, Toti F. Cellular mechanisms underlying the formation of circulating microparticles. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2011;31:15–26. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.200956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zwaal RF, Schroit AJ. Pathophysiologic implications of membrane phospholipid asymmetry in blood cells. Blood. 1997;89:1121–1132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zwaal RF, Comfurius P, Bevers EM. Scott syndrome, a bleeding disorder caused by defective scrambling of membrane phospholipids. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2004;1636:119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hoffmann PR, Kench JA, Vondracek A, Kruk E, Daleke DL, Jordan M, Marrack P, Henson PM, Fadok VA. Interaction between phosphatidylserine and the phosphatidylserine receptor inhibits immune responses in vivo. Journal of immunology. 2005;174:1393–1404. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Castro BM, Prieto M, Silva LC. Ceramide: a simple sphingolipid with unique biophysical properties. Progress in lipid research. 2014;54:53–67. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Surette ME, Fonteh AN, Bernatchez C, Chilton FH. Perturbations in the control of cellular arachidonic acid levels block cell growth and induce apoptosis in HL-60 cells. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:757–763. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.5.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Huber LC, Jungel A, Distler JH, Moritz F, Gay RE, Michel BA, Pisetsky DS, Gay S, Distler O. The role of membrane lipids in the induction of macrophage apoptosis by microparticles. Apoptosis : an international journal on programmed cell death. 2007;12:363–374. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-0622-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang G, Dinkins M, He Q, Zhu G, Poirier C, Campbell A, Mayer-Proschel M, Bieberich E. Astrocytes secrete exosomes enriched with proapoptotic ceramide and prostate apoptosis response 4 (PAR-4): potential mechanism of apoptosis induction in Alzheimer disease (AD) The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:21384–21395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.340513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martin GS, Mannino DM, Moss M. The effect of age on the development and outcome of adult sepsis. Critical care medicine. 2006;34:15–21. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000194535.82812.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Turnbull IR, Clark AT, Stromberg PE, Dixon DJ, Woolsey CA, Davis CG, Hotchkiss RS, Buchman TG, Coopersmith CM. Effects of aging on the immunopathologic response to sepsis. Critical care medicine. 2009;37:1018–1023. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181968f3a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang X, Gu H, Qin D, Yang L, Huang W, Essandoh K, Wang Y, Caldwell CC, Peng T, Zingarelli B, Fan GC. Exosomal miR-223 Contributes to Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Elicited Cardioprotection in Polymicrobial Sepsis. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13721. doi: 10.1038/srep13721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]