Abstract

Several studies have advanced the idea that the etiology of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) could be microbial in origin. In the present study, we tested the possibility that polymicrobial infections exist in tissue from the entorhinal cortex/hippocampus region of patients with AD using immunohistochemistry (confocal laser scanning microscopy) and highly sensitive (nested) PCR. We found no evidence for expression of early (ICP0) or late (ICP5) proteins of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) in brain sections. A polyclonal antibody against Borrelia detected structures that appeared not related to spirochetes, but rather to fungi. These structures were not found with a monoclonal antibody. Also, Borrelia DNA was undetectable by nested PCR in the ten patients analyzed. By contrast, two independent Chlamydophila antibodies revealed several structures that resembled fungal cells and hyphae, and prokaryotic cells, but most probably were unrelated to Chlamydophila spp. Finally, several structures that could belong to fungi or prokaryotes were detected using peptidoglycan and Clostridium antibodies, and PCR analysis revealed the presence of several bacteria in frozen brain tissue from AD patients. Thus, our results show that polymicrobial infections consisting of fungi and bacteria can be revealed in brain tissue from AD patients.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the leading cause of dementia in the elderly, is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by progressive dementia, neuroinflammation and neuronal death1, 2. An important challenge for the field is to uncover the precise etiology of AD to prevent the disease from occurring and/or to implement appropriate therapies. According to the “amyloid cascade hypothesis”, the extracellular accumulation of amyloid peptide (Aβ) triggers tau phosphorylation and cell death3–5. A number of laboratories have questioned the role of amyloid deposition in AD neuropathogenesis and have investigated the potential role for pathogens6–9. The finding that Aβ has antimicrobial activity has provided evidence to suggest that microbial infections induce the formation of Aβ-containing senile plaques10. Aβ peptide is known to participate in innate immune response and protects animals from fungal and bacterial infections11.

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) infection has been considered in the etiology of AD7, 12–14. Indeed, it was postulated more than thirty years ago that latent HSV-1 in the trigeminal ganglia could travel to different brain regions to induce AD15. Accordingly, HSV-1 DNA has been detected in brain samples from AD patients by PCR in different central nervous system (CNS) regions, including the frontal lobe, the temporal lobe and the hippocampus16–19. Interestingly, HSV-1 DNA in brains of elderly normal as well as AD patients, may not preclude a role for the virus in the disease, instead the presence of this viral DNA in the brains of apolipoprotein E4 carriers is associated with AD20–22. However, this correlation between HSV-1 positivity and AD has not been observed in other studies23, 24. Several hallmarks of the neuropathology of AD have been reproduced in culture cells. Thus, infection of neuronal cells by HSV-1 induces the synthesis and processing of β-amyloid, oxidative stress and synaptic dysfunction25–29. The suggestion that some bacteria, such as Chlamydophila pneumoniae, are involved in AD pathology has also been made30. Bacterial DNA has been identified by PCR in AD brain samples and bacterial morphology has been substantiated by electron microscopy and immunohistochemistry31, 32. Nonetheless, other research groups have been unable to demonstrate this infection in AD brains33, 34. The isolation of spirochetes from AD brains has been reported, leading to the suggestion that AD may in fact constitute a spirochetosis35, 36. Certainly, spirochetes were evidenced in AD brains using a variety of techniques, including PCR, immunohistochemistry, electron microscopy, in situ hybridization and culture of the bacteria8. Moreover, induction of β-amyloid takes place in culture neuronal cells incubated with spirochetes or lipopolysaccharide and in mice infected with C. pneumoniae 37, 38. In addition, other pathogens such as Cytomegalovirus and Helicobacter have been considered as the causative agent of AD7. Finally, the possibility that a protozoan such as Toxoplasma gondii is involved in AD has been posited39, but not experimentally supported40, 41.

Our group has provided extensive evidence for fungal infection in patients with AD42–46. Proteomic analyses identified proteins from a range of fungi in AD brain and DNA amplification rendered a number of fungal species present in this tissue43. Furthermore, visualization of fungal cells and hyphae using immunohistochemistry with specific antifungal antibodies clearly point to fungal infection in different regions of the CNS45, 46. In the present work, we tested whether other pathogens could be detected together with fungal structures using similar techniques, i.e. immunohistochemistry and PCR with the same AD samples.

Results

Analysis of the specificity of the different antibodies

We tested several commercial antibodies against HSV-1 and a range of bacteria. In addition, we used in-house-generated polyclonal rabbit antibodies against C. albicans and rat polyclonal antibodies against T. viride 45, 47. We first assayed their specificity and sensitivity using immunohistochemistry. Two mouse monoclonal antibodies, which recognized HSV-1 ICP0 (early viral protein) and ICP5 (late viral protein), were tested in HeLa cells infected with HSV-1 (5 pfu/cell). A second rabbit polyclonal antibody against the human initiation factor of translation eIF4GI was also used. Mock- or HSV-1-infected HeLa cells were processed at different times after infection. Supplementary Figure 1 shows that the monoclonal antibody against ICP0 (green) specifically immunolabeled infected cells, whereas eIF4GI imunoreactivity was found in the cytoplasm (red) and DAPI stained the nuclei (blue). ICP0 immunoreactivity was found inside the nucleus at 3 hours post infection (hpi). However, at later times (6 hpi) immunoreactivity was also located in the cytoplasm, in good agreement with the observations reported for this viral protein44. Immunostaining for ICP5 was positive at later times of infection (18 hpi), but not at earlier times (3 hpi). No HSV-1 immunostaining was observed in mock-infected cells.

Two Borrelia antibodies were tested against a commercial Euroimmun kit containing B. burgdorferi. One was a rabbit polyclonal antibody that, according to the manufacture, recognizes several proteins by western blotting, whereas the other was a mouse monoclonal antibody selective for a Borrelia protein of 28 kDa. Both antibodies immunoreacted with Borrelia, whereas antibodies to Chlamydophila and C. albicans did not recognize B. burgdorferi. Some immunostaining was also apparent with the T. viride antibody (Supplementary Figure 2, panel A).

Two antibodies were tested against a Euroimmun kit containing C. pneumonie. One was a rabbit polyclonal antibody against the major outer membrane porin protein of C. pneumoniae and the other was a mouse monoclonal antibody against C. trachomatis that recognized lipopolysaccharide. Only the rabbit polyclonal antibody recognized C. pneumoniae, whereas the mouse monoclonal antibody did not immunoreact with these samples (Supplementary Figure 2, panel B). Curiously, the rabbit polyclonal antibody against Borrelia also immunoreacted with C. pneumoniae and some immunostaining was apparent with the C. albicans antibody.

To further test the specificity of the in-house antibodies, we evaluated their reactivity against a Euroimmun kit containing five species of Candida: C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, and C. krusei. Supplementary Figure 3 shows that the C. albicans antibody recognized all five Candida species. The rat polyclonal antibody against T. viride recognized, with less intensity, C. albicans, C. glabrata and C. tropicalis, but not C. parapsilosis or C. krusei. Moreover, the Borrelia polyclonal antibodies immunoreacted robustly with C. glabrata and C. tropicalis and also to some extent with C. krusei and C. parapsilosis, but not with C. albicans (Supplementary Figure 4). Furthermore, the rabbit polyclonal antibody against C. pneumoniae immunoreacted with all five Candida species tested, whereas the mouse monoclonal antibodies specific for Borrelia or C. pneumoniae did not react with any of the Candida species analyzed.

Two additional antibodies against bacteria were tested. One was a rabbit polyclonal antibody against C. perfringens that, according to the manufacturer, can also immunoreact with other bacteria. The other was a mouse monoclonal against peptidoglycan, the major component of the cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria. The immunoreactivity of these two antibodies against Borrelia, C. pneumoniae and several Candida spp is shown in Supplementary Figure 5. Notably, the C. perfringens antibody immunoreacted with Borrelia and also with C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis and C. krusei, while the anti-peptidoglycan antibody recognized C. pneumoniae, C. parapsilosis and C. tropicalis (very poorly). In conclusion, some commercial anti-bacteria antibodies can recognize not only prokaryotic cells, but also some fungal species. It is therefore important to determine their specificity.

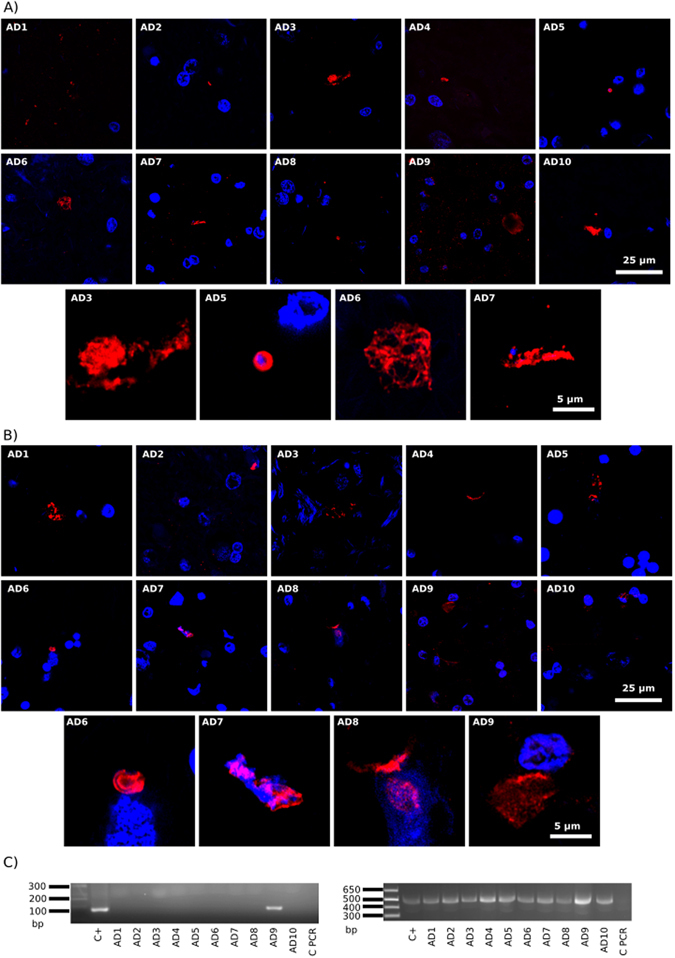

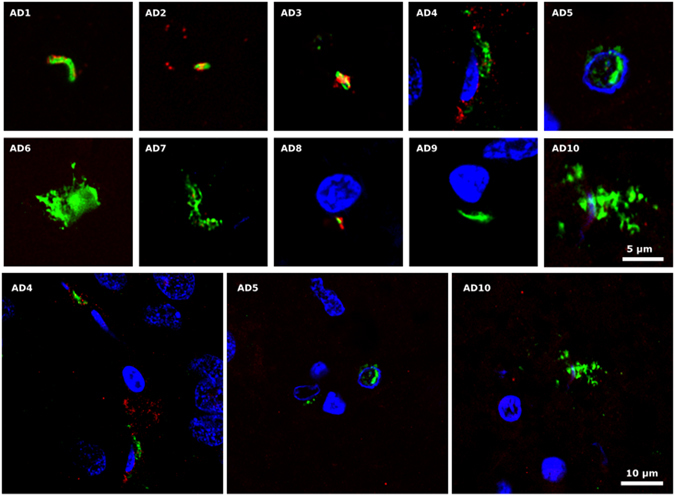

Testing HSV-1 proteins and DNA in brain tissue

Our initial goal was to examine the entorhinal cortex/hippocampus (ERH) region from ten patients with AD to test the possibility that HSV-1 reactivation occurred. Tissue sections of ERH were immunostained with antibodies against ICP0 or ICP5, and also an antibody against C. albicans. Immunohistochemistry of brain sections failed to detect the HSV-1 early (ICP0) or late (ICP5) proteins (Fig. 1A,B; green), whereas the C. albicans antibody immunostained the typical yeast-like and hyphal morphologies previously described by us (Fig. 1A,B; red). These findings suggest that herpetic reactivation did not occur in the brain of the AD patients tested. Of note, it is well established that the ERH region is usually the first and more affected brain region in AD48.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemistry of HSV-1 proteins in brain sections from ten AD patients and PCR analysis of HSV-1 DNA. Entorhinal cortex/hipoccampus (ERH) sections from ten AD patients. Panel A: samples were immunostained with mouse monoclonal antibody (1:50) against HSV ICP0 (green), and rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:100) against C. albicans (red). The different patients are numbered from AD1 to AD10 and one field is shown for each patient. In addition, four selected sections are shown at higher magnification below the ten AD patients. Panel B: samples were immunostained with mouse monoclonal antibody (1:50) against HSV-1 ICP5 (green) and rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:100) against C. albicans (red). DAPI staining of nuclei appears in blue. Scale bar as shown in the figure. Panel C: PCR analysis of HSV-1 and β-globin DNA in frozen brain tissue from ten AD patients. Left panel: Nested PCR analysis of ten ERH samples using primers that amplify HSV-1 glycoprotein D gene. The primers employed were HSV-1 FE (forward external) and HSV-1 RE (reverse external) for the first PCR and primers HSV-1 FI (forward internal) and HSV-1 RI (reverse internal) for the second PCR. As positive control, DNA from HSV-1-infected HeLa cells was used. Right panel: PCR analysis using β-globin oligonucleotide primers. As positive control, DNA extracted from HeLa cells was used. Control PCR: PCR without DNA. DNA markers are indicated on the left.

A complementary approach to assess the existence of HSV-1 in AD brains is by nested PCR of DNA extracted from frozen ERH tissue. Thus, DNA was extracted from frozen samples of the ten AD patients and nested PCR was performed on the HSV gene glycoprotein D18. As a control, DNA extracted from infected HeLa cells was also used as a template. Supplementary Figure 6 shows the HSV-1 DNA fragments amplified by each set of primers, by individual or by nested PCR. Also shown are the amplified bacterial DNA fragments generated from the corresponding primers (see below). Results showed that only one of the ten patients examined was positive for an amplified HSV-1 DNA fragment (Fig. 1C left panel, patient AD9). As a control for DNA in the samples, we used primers to amplify the human β-globin, which was present in all samples (Fig. 1C, right panel). Sequencing of the glycoprotein D fragment confirmed that it belonged to HSV-1 (98% identity). This finding is consistent with results indicating that herpes DNA is present in a low proportion of brain samples23, 24 As we examined only a small region of the brain, it is possible that the frequency of HSV-1 DNA occurrence would increase if more regions of CNS were examined. In previous works, HSV-1 DNA has been examined in different CNS regions including the frontal and temporal lobes and the size of patients examined was higher12, 13, 49. However, the appearance of HSV-1 DNA does not indicate viral reactivation because this technique does not distinguish between viral latency and productive infection.

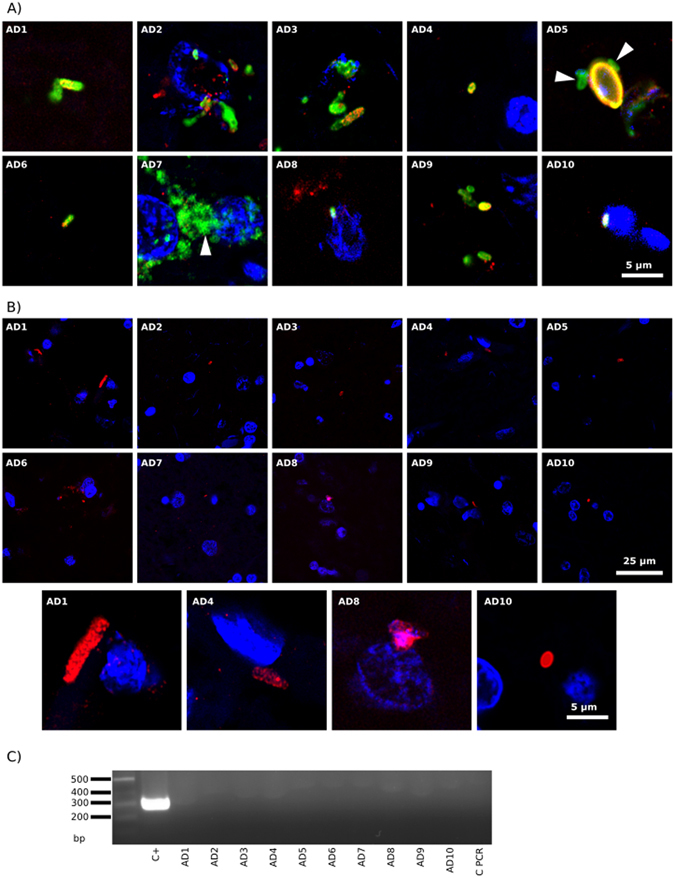

Testing Borrelia macromolecules in brain tissue

To assess the possibility that spirochaetosis can be observed in AD brains, the two antibodies against B. burgdorferi were tested in brain tissue. ERH sections from the ten AD patients were incubated with rabbit polyclonal or mouse monoclonal B. burgdorferi antibodies. A second (antifungal) antibody was also employed; in the case of the Borrelia polyclonal antibody, the antifungal antibody was a rat polyclonal antibody against T. viride, whereas the mouse monoclonal antibody was tested in combination with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against C. albicans.

While the two Borrelia antibodies immunoreacted robustly with B. burgdorferi in our initial specificity testing (Supplementary Figure 2, panel A), the characteristic morphology of spirochetes was not found after extensive analysis of ERH brain sections (Fig. 2A, green). However, the Borrelia polyclonal antibody immunoreacted with a variety of structures, some of which were yeast-like and contained nuclei (DAPI-positive). Some of these structures also immunoreacted with the T. viride antifungal antibody (red), whereas other smaller structures did not immunoreact and, in principle, could be prokaryotic in origin (see arrows in Fig. 2A, panels AD5 and AD7). It seems clear that the Borrelia polyclonal antibody recognizes fungal, and perhaps prokaryotic structures that are not related morphologically to spirochetes. These structures were not detected when the monoclonal B. burgdorferi was used (Fig. 2B). In fact, the monoclonal did not immunoreact with any cell in the brain sections, despite the fact that it recognized B. burgdorferi in our initial specificity testing (Supplementary Figure 2). By contrast, the C. albicans rabbit polyclonal antibody immunoreacted with a variety of rounded and hyphal structures (Fig. 2B, red), as we have recently described45–47.

Figure 2.

Detection of Borrelia proteins and DNA in ERH samples from ten AD patients. PCR assay of B. burgdorferi DNA. Panel A: ERH sections were immunostained with rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:50) against B. burgdorferi (green) and rat polyclonal antibody (1:20) against T. viride (red). Panel B: ERH sections were immunostained with mouse monoclonal antibody (1:10) against B. burgdorferi (green) and rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:100 dilution) against C. albicans (red). DAPI staining of nuclei appears in blue. Scale bar as shown in the figure. Panel C: PCR analysis of Borrelia DNA in frozen brain tissue from ten AD patients. Nested PCR analysis of ten ERH samples using Borr primers to amplify flagellin gene. The primers employed were Borr FE–Borr RE for the first PCR and primers Borr FI–Borr RI for the second PCR. As positive control, DNA extracted from B. burgdorferi was used. Control PCR: PCR without DNA. DNA markers are indicated on the left.

To further assess the possibility of spirochetosis, we performed nested PCR on extracted DNA using primers for Borrelia spp flagellin gene. As expected, the corresponding DNA fragments were detected after amplification of a control sample, however, no product was obtained from the DNA extracts from the ten patients (Fig. 2C), further supporting the view that spirochetosis is not evident in these patients.

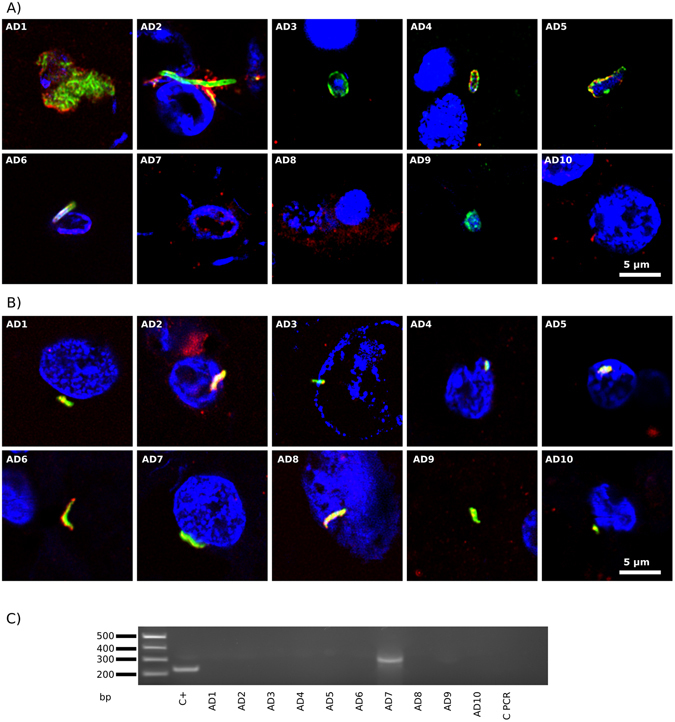

Testing Chlamydophila macromolecules in brain tissue

We have also explored the potential infection of AD brain by C. pneumoniae using immunohistochemistry and PCR. Two commercial C. pneumoniae antibodies were tested. The polyclonal antibody cross-reacted with five yeast species in preliminary tests (Supplementary Figure 4). Consistent with this, we found yeast-like and hyphal structures in ERH sections from several AD brains (Fig. 3A, green). Some of these structures were also labeled with the T. viride antibody (red), suggesting a fungal origin. A different picture emerged using the mouse monoclonal antibody against lipopolysaccharide. In this case, several prokaryotic-like forms were detected intranuclearly or close to the nucleus (green) (Fig. 3B, all panels except AD6 and AD9), suggesting that they represent intracellular bodies, although they do not resemble the elementary or reticulate bodies of C. pneumoniae. Nevertheless, staining with an antibody against C. albicans revealed that these structures were also immunopositive (red), at least in part. Thus, the two C. pneumoniae antibodies failed to categorically detect the presence of C. pneumoniae, but a variety of different forms were immunopositive, some of which clearly represented fungal structures and others possibly prokaryotic cells.

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemistry and PCR analysis to detect C. pneumoniae proteins and DNA in ERH samples from AD patients. Panel A: ERH sections were immunostained with rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:20) against C. pneumoniae (green) and rat polyclonal antibody (1:20) against T. viride (red). Panel B: samples were immunostained with mouse monoclonal antibody (1:10) against C. pneumoniae (green) and rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:100) against C. albicans (red). DAPI staining of nuclei appears in blue. Scale bar as shown in the figure. Panel C: PCR analysis of C. pneumoniae DNA in frozen brain tissue from ten AD patients. PCR analysis of ten ERH samples using primers Clam to amplify MOMP gene. The primers employed were Clam FE–Clam RE for the first PCR and primers Clam FI–Clam RI for the second PCR assay. As positive control, DNA extracted from C. pneumoniae was used. Control PCR: PCR without DNA. DNA markers are indicated on the left.

As before, we performed nested PCR on extracted DNA using specific primers that amplified sequences in the MOMP gene of C. pneumoniae. A DNA fragment slightly higher in size to the predicted amplification product was detected in only one out of ten patients (Fig. 3C, patient AD7). Sequentiation of this fragment revealed that it was of human origin.

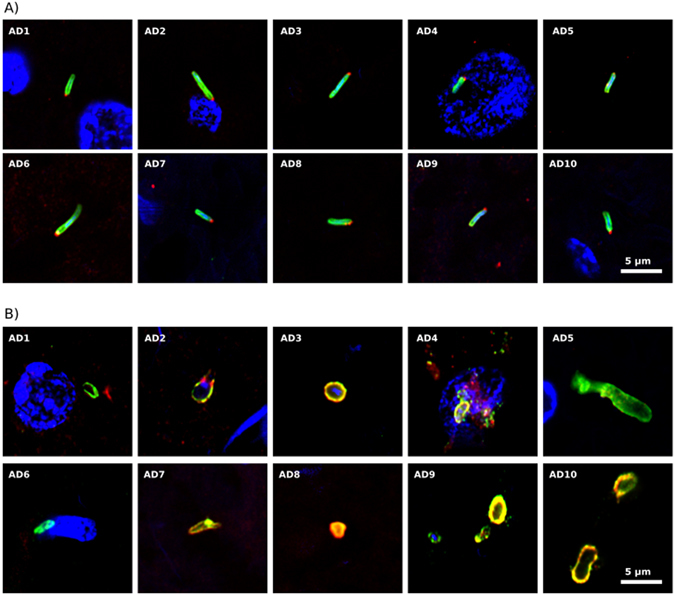

Searching for other bacteria in AD brains

We observed that double staining ERH sections with a rabbit polyclonal C. pneumoniae antibody and a rat polyclonal T. viride antibody revealed a prokaryotic-like structure of 3–5 μm (Fig. 4A). These cells were clearly stained with the C. pneumoniae antibody (green), and curiously the T. viride antibody labeled a red dot on one “pole” of the cell, perhaps due to polar flagella. This staining pattern and morphology was found in ERH sections from all ten AD patients examined (Fig. 4A). We attempted to confirm this staining with a commercial rabbit polyclonal antibody against Clostridium, which can also immunoreact with other bacteria. This antibody was also combined with the rat polyclonal antibody against T. viride. Once again, we found a variety of structures in each ERH section from the ten AD patients examined (Fig. 4B). Some of these structures could be fungal since the Clostridium antibody also immunoreacts with yeast cells (Supplementary Figure 5). However, we did not observe the morphology seen in Fig. 4A. In one ERH sample, a number of cytoplasmic green or red dots were observed, but each dot was only labeled with one antibody (see Fig. 4B, panel AD4). In other instances, hyphal structures (panel AD5) or yeast-like cells positive for DAPI (panels AD2, AD3 and AD9) were also seen.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry of bacterial and fungal proteins in ERH sections from AD patients. Panel A: samples were immunostained with rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:20) against C. pneumoniae (green) and rat polyclonal antibody (1:20) against T. viride (red). Panel B: samples were immunostained with rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:20) against C. perfringens (green) and rat polyclonal antibody (1:20) against T. viride (red). DAPI staining of nuclei appears in blue. Scale bar as shown in the figure.

We further explored the possibility of bacterial infection in ERH sections using double staining with a mouse monoclonal antibody against peptidoglycan (green) and the C. albicans rabbit polyclonal antibody (red). Several structures were also detected with this combination, but it was unclear if they belonged to fungal or prokaryotic cells (Fig. 5). Curiously, a number of dots appeared close to the nucleus in patient AD4, while two cells, perhaps bacteria, were observed inside a nucleus in patient AD5. In summary, the use of different antibodies reveals a variety of structures that, in some cases, could be prokaryotic in origin, but in the majority of occasions they resemble fungi.

Figure 5.

Peptidoglycan in ERH sections from AD patients. ERH samples were processed as described in Materials and Methods. Samples were first immunostained with mouse monoclonal antibody (1:20 dilution) against peptidoglycan (green) and afterwards with rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:50 dilution) against C. albicans (red). DAPI staining of nuclei appears in blue. Scale bar as shown in the figure.

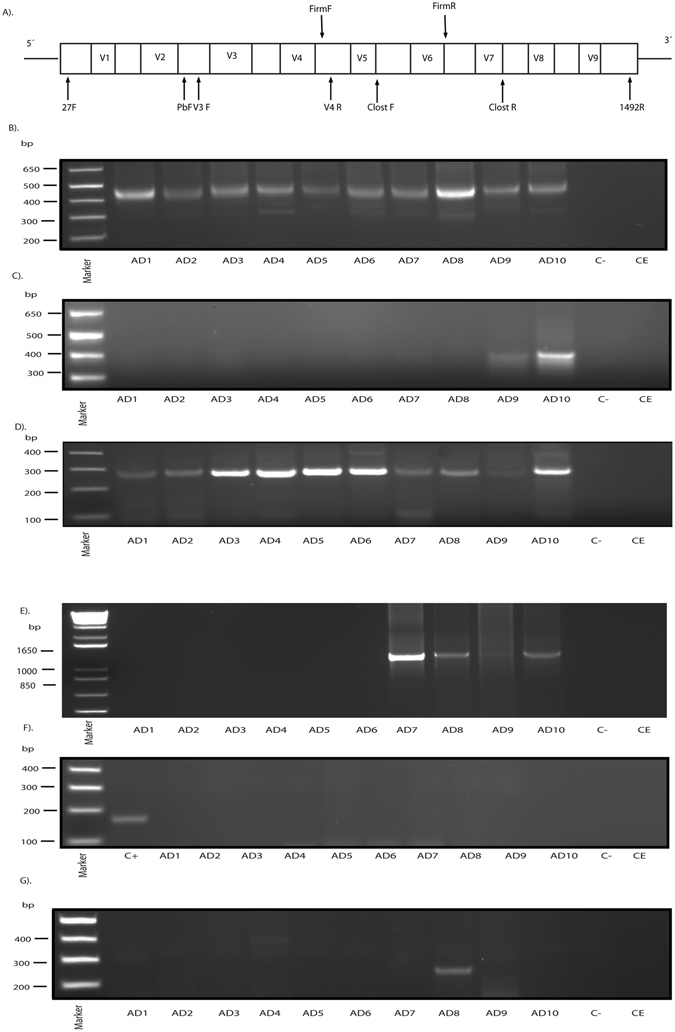

PCR assays to detect microbial DNA in brain tissue from AD

We next sought to identify the potential bacteria in ERH samples from AD patients by PCR. To this end, a battery of primers were designed and tested against DNA from the ten AD patients (see Supplementary Table II). Initially, we used nested PCR with universal primers that amplify a sequence internal to the16S rRNA gene (see scheme Fig. 6A). Several DNA fragments were amplified (Fig. 6B). Sequencing analysis revealed that some of them were human in origin, whereas a 400 bp fragment, which was amplified in all ten patients, corresponded to different bacteria that depended on the patient (Supplementary Table III). For clarity we only report the bacterial species with the highest identity. The bacterial species found corresponded to the following: Burkholderia spp (AD1, AD5, AD8, AD9 and AD10) with an identity of 89–98%, uncultured Sphingomonas (AD2) with an identity of 85%, Brevibacillus spp (AD3) with an identity of 85%, and Xanthomonadaceae bacterium (AD6 and AD7) with an identity of 90% and 87%, respectively. It should be noted that the Burkholderia genus has been derived from the Pseudomonas genus. Also, nested PCR was performed with primers designed to amplify species of the Phylum Firmicutes. One DNA fragment of about 300 bp was amplified from DNA of AD9 and AD10 (Fig. 6C). After sequencing, the fragments corresponded to Staphylococcus epidermidis (94%) and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (99%), respectively. A direct PCR assay was also carried out using primers to amplify a DNA region inside the Clostridium 16 S rRNA gene. Notably, a clear DNA fragment of about 300 bp was amplified in all ten AD patients (Fig. 6D). After sequencing, this DNA fragment corresponded to Burkholderia spp in all patients except AD1, AD7 and AD9. An additional nested PCR was performed using primers designed to amplify Bacillus spp, generating a DNA fragment of about 1100 bp in AD7, AD8 and AD10 (Fig. 6E). Sequencing of this fragment identified uncultured Streptococcus in AD7 and AD8 with an identity of 97 and 92%, respectively, and Staphyloccocus epidermidis in AD10 with an identity of 94%. Recently, it has been reported that E. coli can be detected in brain tissue from AD patients50. To test this possibility, we performed PCR using the primers described by these authors to amplify a region in the gadB gene of E. coli. Figure 6F shows that whereas the PCR was positive with a control sample of E. coli DNA, no fragment was amplified in the ten AD DNA samples. Finally, the possibility that the protozoan T. gondii could be involved in the etiology of AD has been considered39. However, seroprevalence of antibodies against this protozoan is similar in controls and AD patients40, 41. Therefore, we used nested PCR using primers to amplify the SAG2 locus50. A DNA fragment of about 280 bp was found only in AD8 (Fig. 6G), and sequencing revealed it to be human.

Figure 6.

PCR analysis of different microorganisms in brain tissue from ten AD patients. Panel A: Schematic representation of bacterial 16 S rRNA gene with the different variable regions (V1–V9). Location of the primers employed for the different nested PCR carried out in this study: 27 F and 1492 R for the first PCR and the second PCR with the different sets of primers: V3F-V4R (universal primers), FirmF-FirmR (Firmicutes primers), Clost F-Clost R (Clostridium primers), P(b) F-1492R (Bacillus primers). F: forward; R: reverse. Panels B–E: Agarose gel electrophoresis of the DNA fragments amplified by nested PCR of DNA obtained from frozen ERH tissue from ten AD patients. Panel B: Amplification of bacterial DNA fragment using universal oligonucleotide primers by nested PCR. The primers employed were 27F-1492R for the first round PCR and V3-V4 for the second PCR. All samples generated a product of 400 bp. Panel C: Amplification of Firmicutes DNA fragments using specific primers by nested PCR. The primers employed were 27F-1492R for the first PCR and Firm F-Firm R for the second PCR. AD9 and AD10 show a product of about 400 bp. Panel D: Identification of Clostridium spp. DNA by direct PCR. The primers employed were Clost F-Clost R. All the patients show a product of 300 bp. Panel E: Nested PCR assay to amplify Bacillus spp. The primers employed were 27F-1492R for the first PCR and P(b) F-1492 R for the second PCR. AD7, AD8 and AD10 show a product of about 1100 bp. Panel F: Direct PCR analysis to amplify the gadB locus of E.coli. The primers employed were E.coli F and E.coli R. As positive control (C+), DNA was extracted from E.coli. Panel G: Nested PCR analysis to amplify SAG2 partial gene of T. gondii. The primers used were Toxop FE and Toxop RE in the first PCR and Toxop FI and Toxop RI for the second PCR. AD8 amplified a product of about 260 bp. Control -: PCR without DNA. CE: Control of DNA extraction without brain DNA. DNA markers are indicated on the left.

Analysis of HSV-1 and bacteria in brain samples from control subjects

We have carried out a parallel analysis on ERH sections using immunohistochemistry (eight control subjects) and PCR (seven control subjects). We first tested for the presence of HSV-1 ICP0 and ICP5 protein and C. albicans as described in Fig. 1. No HSV-1 proteins were found in the control subjects (Supplementary Figure 7A,B). Also, yeast-like cells immunolabeled with the C. albicans antibody were observed only very occasionally (Supplementary Figure 7A,B), indicating their rarity in control subjects. These findings are in good agreement with the results from our previous study comparing the burden of fungal infection in AD patients and controls47, 51. HSV-1 DNA (glycoprotein D) gene was positive in two out of seven controls (Supplementary Figure 7C).

Immunohistochemistry with Borrelia antibodies revealed a few yeast-like structures (green) in some ERH sections from controls with the rabbit polyclonal antibody (Supplementary Figure 8A). Some of these structures were also immunolabeled with the T. viride antibody (red), suggesting that they could represent fungal cells. In agreement with the results described in Fig. 2, no antigens were detected with the mouse monoclonal antibody against Borrelia (Supplementary Figure 8B). However, a few fungal-related structures were detected with the C. albicans antibody (red) in some controls, whereas others were totally devoid of immunoreactivity (Supplementary Figure 8B). Finally, spirochaetal DNA was not found in any of the seven controls (Supplementary Figure 8C).

Several interesting findings were noted when using two C. pneumoniae antibodies. First, the rabbit polyclonal antibody stained a few yeast-like and hyphal structures (green) that in some instances were also immunostained with the T. viride antibody (red) (Supplementary Figure 9A). These fungal structures were rare and in some of them, such as in C1, C4, C5 and C8, the nucleus was evident by DAPI staining. A similar finding was observed when the mouse monoclonal antibody was tested in combination with the rabbit polyclonal C. albicans antibody (Supplementary Figure 9B). Rounded yeast cells and hyphae could be detected with the C. pneumoniae antibody, although they were much less abundant than those observed in AD patients (Fig. 3). The presence of C. pneumoniae DNA was analyzed by nested PCR and only in one case (C1) could a faint band be seen (Supplementary Figure 9C), which corresponded to C. pneumoniae by sequencing.

Clostridium and peptidoglycan antibodies were tested on control brains following a protocol similar to that described in Figs 4B and 5. Very few structures were immunolabeled with these antibodies in five controls (green), whereas no immunolabeling appeared in the remaining controls (Supplementary Figure 10). For the most part, we found no immunopositive cells with the T. viride and C. albicans antibodies (red) (Supplementary Figure 10). The five positive samples for the Clostridium antibody were C1, C4, C5, C6 and C7 (amplified C1, C4, C5 and C7). Control C7 was positive for the T. viride antibody, but only one structure was found in this section. The peptidoglycan antibody revealed a few structures in controls C2, C4, C6, C7 and C8 (amplified C2, C6, C7 and C8). C7 was also positive with the C. albicans antibody. Altogether, these observations indicate that some of these commercial antibodies raised against bacteria can reveal prokaryotic-like cells and also may cross-react with structures that resemble fungi. Moreover, the burden of these structures in controls is much lower than in AD patients.

Finally, PCR analysis was carried out with DNA extracted from the seven control ERH samples. The universal primers to amplify a region of the 16 S rRNA gene of bacteria generated a robust 400 bp fragment in all seven controls tested (Supplementary Figure 11A). Indeed, the presence of bacteria was confirmed after sequencing of this fragment (Supplementary Table III). Thus, in all controls, except in C7, Burkholderia spp was detected, while Clostridium spp was found in C7. This finding was not unexpected because bacterial DNA is found in brains from control subjects52. Using primers designed to amplify Firmicutes DNA, one fragment of about 400 bp was observed in C8 (Supplementary Figure 11B), although the low amount of the product ruled out a sequencing analysis. A direct PCR assay similar to that described in Fig. 6D was done using primers for Clostridium spp. In this case, no DNA fragments were found in the seven control samples (Supplementary Figure 11C). Following an assay to detect Bacillus DNA, we found six out of seven control subjects with a fragment of about 1100 bp (Supplementary Figure 11D). Only in one case (C7) this DNA fragment was successfully sequenced, revealing Streptococcus spp (97%). Finally, no protozoal DNA was detected in the seven control ERH samples after using primers to amplify T. gondii SAG2 using nested PCR (Supplementary Figure 11E). All the results obtained both by immunohistochemistry and by PCR are summarized in Supplementary Table IV.

Discussion

The suspicion that the etiology of AD is microbial in origin has been advanced by some groups7, 9. The main challenge with these types of studies is to first provide compelling evidence for the existence of infection in brain tissue of AD patients and then to prove that, when detected, the infection contributes to the etiology of AD, rather than a risk factor or a consequence of neurodegeneration. Regarding the first point, we have extensively analyzed potential microbial infection in AD. Accordingly, fungal macromolecules including polysaccharides, proteins and DNA can be found in peripheral blood, cerebrospinal fluid and brain tissue of AD patients53, 54, indicative of disseminated fungal infection. Moreover, fungal yeast-like cells and hyphae can be visualized by immunohistochemistry using specific antibodies45, 46. Several fungal species in brain tissue of AD patients have been identified9, 46. Although these species vary between patients, those belonging to the genera Alternaria, Botrytis, Candida, Cladosporium, Cryptococcus, Fusarium, Malasezzia and Penicillium are particularly prevalent9.

The present study shows that an evaluation of the immunoreactivity of antibodies employed to assess microbial infection is important. Some commercially available rabbit polyclonal bacterial antibodies crossreact with fungi and vice versa, and thus it is important to use an array of different antibodies. Because of this, we have tested in previous studies a variety of polyclonal antibodies raised against different fungal species, including C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. famata, C. parapsilosis, Phoma betae, Penicillium notatum, Syncephalastrum racemosum and T. viride 45, 46, 51. We have also used rabbit polyclonal antibodies against specific fungal components, such as chitin, enolase and β-tubulin, to detect fungal structures in AD brain sections47. In our opinion, the use of a single antibody against a given bacterium may lead to misleading observations.

In the present study we looked for evidence of HSV-1 reactivation in brain tissue from AD patients. Our results indicate that this reactivation does not occur in the sections examined as no expression of ICP0 or ICP5 could be found in neurons or glial cells. However, we cannot disprove that reactivation of HSV-1 is taking place in other brain regions or in other sections of ERH. Our finding that HSV-1 DNA was amplified from only one AD patient agrees with recent results55, however, we have only examined a small portion of the brain and only in ten patients. Previous studies examining different brain regions in many AD patients found that the proportion of positive HSV-1 DNA was 100% in some instances12, 13. Notably, HSV-1 and some bacteria induce the synthesis of β-amyloid and the processed Aβ peptide in culture neuronal cells and in mouse brains. This is consistent with the idea that Aβ is part of the innate immune system against microbial infections that occur in AD brains10, 11. In this regard, spirochetes or C. pneumoniae have been considered as a possible cause of the AD7, 30, 56, 57.

Interestingly, a variety of bacteria have been identified in human tissue of several chronic systemic pathologies, including arthritis, atherosclerosis, biliary cirrhosis and aortic aneurysms58–62. To our knowledge, fungal infection has not been tested in these setting. Several bacterial species have also been found in normal brain52. In principle, it should be possible that the colonization of a given tissue, such as CNS, by fungi could facilitate other microbial infections. Along this line, we explored the possibility that other bacterial infections are present in AD brains. Analysis to identify bacterial DNA by PCR in AD brain tissue revealed infection by several bacterial species in all ten AD patients. One of the most prominent bacteria found was Burkholderia spp. However, we have been unable to demonstrate the presence of spirochetes or C. pneumoniae by immunohistochemistry and by PCR.

The molecular basis for this interkingdom communication that can exacerbate human disease and lead to higher mortality represents an emerging field and is the subject of intense research53, 59. Thus, over 20% of all candidemia cases also have bacterial co-infection, which worsens the prognosis of these patients63. In some instances, fungal and bacterial infections are synergistic, whereas in other cases they can be antagonistic. It is quite possible that the microbial metabolites excreted by one species are beneficial or detrimental for the other species64. This picture is even more complicated if we consider the host immune response65, 66. Correspondingly, some species or their metabolites can interfere with an adequate immune response, facilitating colonization by other species. In other instances, one infection can stimulate the immune system leading to a bystander effect that may block or decrease other potential infections. Our findings clearly point to the possibility that bacterial infection can coexist with fungi in AD brains. Therefore, the picture that emerges at present is that polymicrobial infections can be detected in AD brains. These results may be important to help ascertain the precise etiology of AD and may be crucial to develop an adequate therapy for these patients.

Materials and Methods

Description of patients and control subjects

We analyzed frozen and paraffin-fixed samples of tissue obtained from brain donors diagnosed with AD and control individuals. All cases were diagnosed according to current neuropathological consensus guidelines67. Details about the age and gender of each patient are listed in Supplementary Table I. All samples used were supplied by Banco de Tejidos, Fundación CIEN (Centro de Investigación de Enfermedades Neurológicas, Madrid. Spain). The study was approved by the ethics committee of Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. The transfer of samples was carried out according to national regulations concerning research on human biological samples. For all cases, written informed consent is available. All ethico-legal documents of the brain bank, including written informed consent, were approved by an ethics committee external to the bank. The donors were anonymous to the investigators who participated in the study. Brain samples were processed as described in detail before51.

Antibodies employed in this work

The following antibodies were purchased: mouse monoclonal antibody against HSV-1 ICP0, used at 1:50 dilution; mouse monoclonal antibody against HSV-1/2 ICP5 major capsid protein, used at 1:50 dilution (both from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); rabbit polyclonal antibody against Borrelia burgdorferi (Genetex, Irvine, CA), used at 1:50 dilution; mouse monoclonal antibody against Borrelia burgdorferi (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), used at 1:10 dilution; rabbit polyclonal antibody against C. pneumoniae, which immunoreacts with the major outer porin (Biorbyt, Cambridge, UK), used at 1:20 dilution; mouse monoclonal antibody against Chlamydia (Abcam), used at 1:10 dilution; rabbit polyclonal antibody against Clostridium perfringens type D (Bioss Antibodies, Woburn, MA), used at 1:20 dilution; mouse monoclonal antibody against peptidoglycan (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), used at 1:20 dilution.

Antibodies against C. albicans and Trichoderma viride were produced in our laboratory as described elsewhere46. Additionally, the rabbit polyclonal antibody anti-eIF4GI was produced in our laboratory as described68.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue sections from the CNS (5 μm) were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 24 h and embedded in paraffin following standard protocols. For immunohistochemical analysis, paraffin was removed and tissues were rehydrated and boiled for 2 min in citrate buffer and then incubated for 10 min with 50 mM ammonium chloride. Subsequently, tissue sections were incubated for 10 min with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS and for 20 min with 2% BSA in PBS. Sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with a primary antibody in PBS/BSA. Thereafter, sections were washed with PBS and further incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with the corresponding secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa 488 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Sections were then incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with a third antibody in PBS, washed with PBS, and further incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with the corresponding secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa 555 (Invitrogen). Subsequently, tissue sections were stained with DAPI (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) and samples were treated with autofluorescence eliminator reagent (Merck Millipore).

We also used the following kits: Anti-Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto IIFT (IgG), anti-Chlamydia pneumoniae MIF (IgG) and IIFT, Candida mosaic 1 (Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany). Briefly, the primary antibody was incubated for 30 min at room temperature and the secondary antibody conjugated (to Alexa 488) was incubated for 30 min.

All images were collected and analyzed with a LSM710 confocal laser scanning microscope combined with the upright microscope stand AxioImager.M2 (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) running Zeiss ZEN 2010 software. The spectral system employed was Quasar + 2 PMTs. Images were deconvoluted using Huygens software (4.2.2 p0) and visualized with ImageJ.

DNA Extraction from frozen CNS tissue

DNA was extracted from frozen tissue using the QIAmp Genomic DNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) as follows: 20 µl proteinase K (>600mAU/ml) and 180 µl of buffer ATL were added to 25 mg of brain tissue, followed by pulse-vortexing for 15 s. Digestion was carried out at 56 °C for 1–3 h with agitation. Subsequently, 200 µl of buffer AL was added to each sample followed by vortexing for 15 s and incubation at 70 °C for 10 min. A 200 µl volume of ethanol was then added to each sample followed by vortexing for 15 s. The mixture was applied to the QIAamp Mini spin column and centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 1 min. Then, 500 µl buffer AW was applied to the column followed by centrifugation at 8000 rpm for 1 min. After a final wash step with 500 µl of buffer AW2 (14000 rpm for 3 min), samples were collected in 40 µl distilled water and DNA was quantified in a NanoDrop® ND-1000 UV-Vis spectrophotometer. Negative controls included three samples of tri-distilled filtered water.

Oligonucleotide primers

We used several sets of primers to amplify genome regions of the different microorganisms listed in supplementary Table II. Primers for herpes simplex virus type I (HSV-1) have been described by Mori et al.18 and were used to amplify the glycoprotein D gene. The flagellin gene of Borrelia spp was amplified with the primers described by Hudman69. Primers used to amplify the MOMP gene of C. pneumoniae were as described by Sriram et al.70. The location of the primers used to amplify these genes is depicted in Supplementary Figure 6.

We used sets of primers located in distinctive conserved regions to amplify the 16 S rRNA gene (see Fig. 6A). Two sets of universal primers 27F-1492R and V3-V4 were used to amplify the conserved regions V1-V9 and V3-V4, respectively. Primers to amply the 16 S rRNA from several bacteria of the Firmicutes phylum (Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus epidermidis, S. aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, Lactobacillus casei, Streptococcus pyogenes, Clostridium perfringens and Bacillus cereus) were designed using the Genbank database and were aligned using ClustalW. Primers to amplify the 16 S rRNA from different Clostridium species (C. perfringens, C. tetani, C. septicum, C. sordellii, C. baratii, C. novyi, C. difficile and C. botulinum) were designed as above. Primers to amplify the 16 S rRNA coding region from Bacillus were as described by Lee et al.71. Primers used to amplify the glutamate decarboxylase (gadB) gene from Escherichia coli were as described50. Primers used to amplify the SAG2 locus of T. gondii have also been described40. All oligonucleotide primers were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO).

Nested PCR

A number of measures were used to avoid PCR contamination including the use of separate rooms and glassware supplies for PCR set-up and products, aliquoted reagents, positive-displacement pipettes, aerosol-resistant tips and multiple negative controls. DNA samples obtained from frozen brain tissues were analyzed by nested PCR using several primer pairs.

To amplify the glycoprotein D gene of HSV-1, the first PCR was carried out with 4 μl of DNA incubated at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of 1 min at 94 °C, 1 min at 50 °C and 45 s at 72 °C. Primers used in the first PCR were forward HSV-1 external and reverse HSV-1 external. The second PCR was performed using 0.5 μl of the product obtained in the first PCR with forward and reverse HSV-1 internal primers, for 30 cycles 1 min at 94 °C, 1 min at 55 °C and 5 min at 72 °C.

The Borrelia spp flagellin gene was amplified with primers BorrFE-BorrRE and BorrFI-BorrRI. The first PCR was carried out with 4 μl of DNA incubated at 95 °C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of 45 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 55 °C and 45 s at 72 °C. The second PCR was performed using 0.5 μl of the product obtained in the first PCR assay with forward and reverse Borr internal primers using the same conditions as the first PCR.

To amplify the MOMP gene, the first PCR was carried out with 4 μl of DNA incubated at 95 °C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles of 1 min at 94 °C, 1 min at 56 °C and 45 s at 72 °C. Primers used in the first PCR were forward Clam external and reverse Clam external. The second PCR was performed using 0.5 μl of the product obtained in the first PCR with forward and reverse Clam internal primers for 35 cycles of 1 min at 94 °C, 1 min at 58 °C and 5 min at 72 °C.

The human β-globin gene served as a control for DNA extraction. Primers are listed in Supplementary Table II. PCR was carried out with 4 μl of DNA incubated at 95 °C for 10 min and amplified with 42 cycles of 45 s at 94 °C, 1 min at 60 °C and 45 s at 72 °C.

Different sets of primers were used to amplify the 16 S rRNA gene (see Fig. 6A and Supplementary Table II). We first amplified the region between V1-V9. The first PCR was carried out with 2 μl of DNA incubated at 95 °C for 5 min followed by 34 cycles of 1 min at 94 °C, 1 min at 51 °C and 3 min at 72 °C. Primers used in the first PCR were 27F-1492R. The second PCR was carried out using one of the following primer sets: V3-V4, Firmicutes, Clostridium and Bacillus. The second PCR was performed using 2 μl of the product obtained in the first PCR with forward V3 and reverse V4 internal primers for 35 cycles 1 min at 94 °C, 1 min at 55 °C and 3 min at 72 °C. Alternatively, the second PCR was performed as above using forward Firm and reverse Firm internal primers for 40 cycles 1 min at 94 °C, 1 min at 55 °C and 3 min at 72 °C. In another reaction, forward and reverse Clost primers were used using the conditions for Firm internal primers. Also, a second PCR was performed using 2 μl of the product obtained in the first PCR with forward pB and reverse 1492 internal primers as before. We performed a direct PCR to amplify the gadB locus of E. coli. PCR was carried out with 2 μl of DNA incubated at 94 °C for 5 min and amplified with 45 cycles of 45 s at 94 °C, 1 min at 57 °C and 45 s at 72 °C. Finally, nested PCR was performed for amplification of the SAG2 partial gene from T. gondii using 2 μl of DNA incubated at 94 °C for 5 min followed by 40 cycles of 45 s at 94 °C, 1 min at 59 °C and 45 s at 72 °C. The second PCR was identical to the first PCR except that the annealing temperature was 56 °C. Primers used in the first and second PCRs were forward Toxo and reverse Toxo external and forward Toxo and reverse Toxo internal, respectively. The theoretical size of the different amplicons and the primers used are listed in Supplementary Table II. Amplified DNA products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and stained with ethidium bromide. Some PCR products were sequenced by Macrogen (South Korea). The sequences obtained have been submitted to European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) with the following access number LT837521-LT837524 and LT835124-LT835152.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The financial support of Pharma Mar, S.A. is acknowledged. We also acknowledge an institutional grant to Centro de Biología Molecular “Severo Ochoa” from the Fundación Ramón Areces.

Author Contributions

D.P., R.A. and A.F. carried out the immunofluorescence and PCR experiments; A.R. prepared the samples from frozen CNS material and obtained the paraffin sections; D.P., R.A. and L.C. designed the experiments; L.C. designed the study and wrote the paper. D.P., R.A. and A.F. prepared the figures. All authors discussed the data obtained. All authors reviewed and provided comments upon preparation of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Diana Pisa and Ruth Alonso contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-05903-y

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Grammas P. Neurovascular dysfunction, inflammation and endothelial activation: implications for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:26. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krstic D, Knuesel I. Deciphering the mechanism underlying late-onset Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:25–34. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gotz J, Schild A, Hoerndli F, Pennanen L. Amyloid-induced neurofibrillary tangle formation in Alzheimer’s disease: insight from transgenic mouse and tissue-culture models. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2004;22:453–465. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hampel H, et al. Advances in the therapy of Alzheimer’s disease: targeting amyloid beta and tau and perspectives for the future. Expert Rev Neurother. 2015;15:83–105. doi: 10.1586/14737175.2015.995637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Brien RJ, Wong PC. Amyloid precursor protein processing and Alzheimer’s disease. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:185–204. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Chiara G, et al. Infectious agents and neurodegeneration. Mol Neurobiol. 2012;46:614–638. doi: 10.1007/s12035-012-8320-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris SA, Harris EA. Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 and Other Pathogens are Key Causative Factors in Sporadic Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;48:319–353. doi: 10.3233/JAD-142853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miklossy J. Emerging roles of pathogens in Alzheimer disease. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2011;13:e30. doi: 10.1017/S1462399411002006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alonso R, Pisa D, Aguado B, Carrasco L. Identification of fungal species in brain tissue from Alzheimer’s disease by next-generation sequencing. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;58:55–67. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soscia SJ, et al. The Alzheimer’s disease-associated amyloid beta-protein is an antimicrobial peptide. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9505. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar DK, et al. Amyloid-beta peptide protects against microbial infection in mouse and worm models of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:340ra372. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Itzhaki RF. Herpes simplex virus type 1 and Alzheimer’s disease: increasing evidence for a major role of the virus. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:202. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Itzhaki RF. Herpes and Alzheimer’s Disease: Subversion in the Central Nervous System and How It Might Be Halted. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;54:1273–1281. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olsen I, Singhrao SK. Can oral infection be a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease? J Oral Microbiol. 2015;7:29143. doi: 10.3402/jom.v7.29143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ball MJ. “Limbic predilection in Alzheimer dementia: is reactivated herpesvirus involved?”. Can J Neurol Sci. 1982;9:303–306. doi: 10.1017/S0317167100044115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jamieson GA, Maitland NJ, Itzhaki RF. Herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA sequences are present in aged normal and Alzheimer’s disease brain but absent in lymphocytes. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1992;15(Suppl 1):197–201. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4943(05)80019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jamieson GA, Maitland NJ, Wilcock GK, Craske J, Itzhaki RF. Latent herpes simplex virus type 1 in normal and Alzheimer’s disease brains. J Med Virol. 1991;33:224–227. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890330403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mori I, et al. Reactivation of HSV-1 in the brain of patients with familial Alzheimer’s disease. J Med Virol. 2004;73:605–611. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wozniak MA, Mee AP, Itzhaki RF. Herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA is located within Alzheimer’s disease amyloid plaques. J Pathol. 2009;217:131–138. doi: 10.1002/path.2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Itzhaki RF, et al. Herpes simplex virus type 1 in brain and risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 1997;349:241–244. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)10149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wozniak MA, Shipley SJ, Combrinck M, Wilcock GK, Itzhaki RF. Productive herpes simplex virus in brain of elderly normal subjects and Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Med Virol. 2005;75:300–306. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin WR, Shang D, Wilcock GK, Itzhaki RF. Alzheimer’s disease, herpes simplex virus type 1, cold sores and apolipoprotein E4. Biochem Soc Trans. 1995;23:594S. doi: 10.1042/bst023594s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hemling N, et al. Herpesviruses in brains in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:267–271. doi: 10.1002/ana.10662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marques AR, et al. Lack of association between HSV-1 DNA in the brain, Alzheimer’s disease and apolipoprotein E4. J Neurovirol. 2001;7:82–83. doi: 10.1080/135502801300069773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Civitelli L, et al. Herpes simplex virus type 1 infection in neurons leads to production and nuclear localization of APP intracellular domain (AICD): implications for Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. J Neurovirol. 2015;21:480–490. doi: 10.1007/s13365-015-0344-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Chiara G, et al. APP processing induced by herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) yields several APP fragments in human and rat neuronal cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13989. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piacentini R, et al. Herpes Simplex Virus type-1 infection induces synaptic dysfunction in cultured cortical neurons via GSK-3 activation and intraneuronal amyloid-beta protein accumulation. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15444. doi: 10.1038/srep15444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santana S, Sastre I, Recuero M, Bullido MJ, Aldudo J. Oxidative stress enhances neurodegeneration markers induced by herpes simplex virus type 1 infection in human neuroblastoma cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wozniak MA, Itzhaki RF, Shipley SJ, Dobson CB. Herpes simplex virus infection causes cellular beta-amyloid accumulation and secretase upregulation. Neurosci Lett. 2007;429:95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.09.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balin BJ, et al. Chlamydophila pneumoniae and the etiology of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;13:371–380. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2008-13403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balin BJ, et al. Identification and localization of Chlamydia pneumoniae in the Alzheimer’s brain. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1998;187:23–42. doi: 10.1007/s004300050071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerard HC, et al. Chlamydophila (Chlamydia) pneumoniae in the Alzheimer’s brain. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2006;48:355–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2006.00154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gieffers J, Reusche E, Solbach W, Maass M. Failure to detect Chlamydia pneumoniae in brain sections of Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:881–882. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.2.881-882.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ring RH, Lyons JM. Failure to detect Chlamydia pneumoniae in the late-onset Alzheimer’s brain. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2591–2594. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.7.2591-2594.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miklossy J. Alzheimer’s disease - a neurospirochetosis. Analysis of the evidence following Koch’s and Hill’s criteria. J Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:90. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miklossy J, Kasas S, Janzer RC, Ardizzoni F. & Van der Loos, H. Further ultrastructural evidence that spirochaetes may play a role in the aetiology of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroreport. 1994;5:1201–1204. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199406020-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Little CS, Hammond CJ, MacIntyre A, Balin BJ, Appelt DM. Chlamydia pneumoniae induces Alzheimer-like amyloid plaques in brains of BALB/c mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25:419–429. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(03)00127-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miklossy J, et al. Beta-amyloid deposition and Alzheimer’s type changes induced by Borrelia spirochetes. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:228–236. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kusbeci OY, Miman O, Yaman M, Aktepe OC, Yazar S. Could Toxoplasma gondii have any role in Alzheimer disease? Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2011;25:1–3. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181f73bc2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mahami-Oskouei M, et al. Toxoplasmosis and Alzheimer: can Toxoplasma gondii really be introduced as a risk factor in etiology of Alzheimer? Parasitol Res. 2016;115:3169–3174. doi: 10.1007/s00436-016-5075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perry CE, et al. Seroprevalence and Serointensity of Latent Toxoplasma gondii in a Sample of Elderly Adults With and Without Alzheimer Disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2016;30:123–126. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carrasco, L., Alonso, R., Pisa, D. & Rabano, A. Alzheimer’s disease and fungal infection., in Handbook of Infection and Alzheimer’s Disease, Vol. 5. (ed. Miklossy, J.) 281–294 (2017).

- 43.Alonso R, et al. Fungal infection in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;41:301–311. doi: 10.3233/JAD-132681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alonso R, Pisa D, Rabano A, Rodal I, Carrasco L. Cerebrospinal Fluid from Alzheimer’s Disease Patients Contains Fungal Proteins and DNA. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;47:873–876. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pisa D, Alonso R, Juarranz A, Rabano A, Carrasco L. Direct visualization of fungal infection in brains from patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;43:613–624. doi: 10.3233/JAD-141386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pisa D, Alonso R, Rabano A, Rodal I, Carrasco L. Different Brain Regions are Infected with Fungi in Alzheimer’s Disease. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15015. doi: 10.1038/srep15015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pisa D, Alonso R, Rabano A, Horst MN, Carrasco L. Fungal Enolase, beta-Tubulin, and Chitin Are Detected in Brain Tissue from Alzheimer’s Disease Patients. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1772. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Serrano-Pozo A, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Hyman BT. Neuropathological alterations in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2011;1:a006189. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Itzhaki, R. F., Dobson, C. B. & Wozniak, M. A. Herpes simplex virus type 1 and Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol55, 299–300; author reply 300–291 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Zhan X, et al. Gram-negative bacterial molecules associate with Alzheimer disease pathology. Neurology. 2016;87:2324–2332. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pisa D, Alonso R, Rabano A, Carrasco L. Corpora Amylacea of Brain Tissue from Neurodegenerative Diseases Are Stained with Specific Antifungal Antibodies. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:86. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Branton WG, et al. Brain microbial populations in HIV/AIDS: alpha-proteobacteria predominate independent of host immune status. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54673. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alonso R, et al. Evidence for fungal infection in cerebrospinal fluid and brain tissue from patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Int J Biol Sci. 2015;11:546–558. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.11084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alonso R, Pisa D, Rabano A, Carrasco L. Alzheimer’s disease and disseminated mycoses. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33:1125–1132. doi: 10.1007/s10096-013-2045-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Olsson J, et al. HSV presence in brains of individuals without dementia: the TASTY brain series. Dis Model Mech. 2016;9:1349–1355. doi: 10.1242/dmm.026674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miklossy J. Historic evidence to support a causal relationship between spirochetal infections and Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2015;7:46. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2015.00046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miklossy J. Bacterial Amyloid and DNA are Important Constituents of Senile Plaques: Further Evidence of the Spirochetal and Biofilm Nature of Senile Plaques. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;53:1459–1473. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koren O, et al. Human oral, gut, and plaque microbiota in patients with atherosclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4592–4598. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011383107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leech MT, Bartold PM. The association between rheumatoid arthritis and periodontitis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2015;29:189–201. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marques da Silva R, et al. Bacterial diversity in aortic aneurysms determined by 16S ribosomal RNA gene analysis. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:1055–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ott SJ, et al. Detection of diverse bacterial signatures in atherosclerotic lesions of patients with coronary heart disease. Circulation. 2006;113:929–937. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.579979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Padgett KA, et al. Phylogenetic and immunological definition of four lipoylated proteins from Novosphingobium aromaticivorans, implications for primary biliary cirrhosis. J Autoimmun. 2005;24:209–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Klotz SA, Chasin BS, Powell B, Gaur NK, Lipke PN. Polymicrobial bloodstream infections involving Candida species: analysis of patients and review of the literature. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;59:401–406. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dixon EF, Hall RA. Noisy neighbourhoods: quorum sensing in fungal-polymicrobial infections. Cell Microbiol. 2015;17:1431–1441. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ghosh S, et al. Candida albicans cell wall components and farnesol stimulate the expression of both inflammatory and regulatory cytokines in the murine RAW264.7 macrophage cell line. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2010;60:63–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Leonhardt I, et al. The fungal quorum-sensing molecule farnesol activates innate immune cells but suppresses cellular adaptive immunity. MBio. 2015;6:e00143. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00143-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Montine TJ, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0910-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Aldabe R, Feduchi E, Novoa I, Carrasco L. Efficient cleavage of p220 by poliovirus 2Apro expression in mammalian cells: effects on vaccinia virus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;215:928–936. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hudman DA, Sargentini NJ. Detection of Borrelia, Ehrlichia, and Rickettsia spp. in ticks in northeast Missouri. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2016;7:915–921. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sriram S, et al. Comparative study of the presence of Chlamydia pneumoniae in cerebrospinal fluid of Patients with clinically definite and monosymptomatic multiple sclerosis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2002;9:1332–1337. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.9.6.1332-1337.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lee JH, Kim TW, Lee H, Chang HC, Kim HY. Determination of microbial diversity in meju, fermented cooked soya beans, using nested PCR-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2010;51:388–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2010.02906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.