Abstract

Fibrosis-related events play a part in most blinding diseases worldwide. However, little is known about the mechanisms driving this complex multifactorial disease. Here we have carried out the first genome-wide RNA-Sequencing study in human conjunctival fibrosis. We isolated 10 primary fibrotic and 7 non-fibrotic conjunctival fibroblast cell lines from patients with and without previous glaucoma surgery, respectively. The patients were matched for ethnicity and age. We identified 246 genes that were differentially expressed by over two-fold and p < 0.05, of which 46 genes were upregulated and 200 genes were downregulated in the fibrotic cell lines compared to the non-fibrotic cell lines. We also carried out detailed gene ontology, KEGG, disease association, pathway commons, WikiPathways and protein network analyses, and identified distinct pathways linked to smooth muscle contraction, inflammatory cytokines, immune mediators, extracellular matrix proteins and oncogene expression. We further validated 11 genes that were highly upregulated or downregulated using real-time quantitative PCR and found a strong correlation between the RNA-Seq and qPCR results. Our study demonstrates that there is a distinct fibrosis gene signature in the conjunctiva after glaucoma surgery and provides new insights into the mechanistic pathways driving the complex fibrotic process in the eye and other tissues.

Introduction

Glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide and fibrosis is the critical determinant of the long-term surgical success after glaucoma surgery. Histopathologic findings of failed fibrotic capsules have indicated a key role of the fibroblast and the production of extracellular matrix components in the pathophysiology of fibrotic encapsulation in glaucoma surgery1. However, fibrosis is a complex multifactorial disease and little is known about the diverse molecular mechanisms and pathways underlying the fibrotic response. Identifying the dysregulated genes will be important in understanding the complex network of signalling pathways driving the fibrotic process and in finding potential novel therapeutic targets and biomarkers of disease severity and prognosis in fibrotic eye diseases.

It is well established that certain groups of patients, for example Afro-Caribbean people, scar worse than others2, 3. However, reliable biomarkers to stratify the risk of scarring and post-surgical fibrosis in the eye and other tissues are currently missing. Being able to predict a patient’s risk of scarring according to their genetic profile holds great potential to the development of a more personalised and stratified therapy in ocular fibrosis4. A major hurdle has been the lack of availability of human tissues for research and the small surgical specimen sizes yielding limited amounts and poor quality RNA. RNA-Sequencing (RNA-Seq) is a powerful and highly sensitive technology that allows the whole transcriptome to be studied compared to DNA microarrays and also requires smaller amounts of RNA5, 6.

In this study, we have carried out a genome-wide RNA-Seq analysis to compare the gene expression profiles of fibrotic and non-fibrotic human conjunctival fibroblast cell lines between patients with and without previous glaucoma surgery, respectively. We have also mapped the enrichment of differentially expressed genes to specific gene ontology and protein networks, and identified distinct changes in signalling pathways that could contribute to the fibrotic process and clinical phenotype.

Results

Patient Demographics

We performed RNA-Sequencing on 10 fibrotic fibroblast (FF3, FF10, FF13, FF14, FF15, FF16, FF17, FF18, FF20, FF21) and 7 non-fibrotic fibroblast (NF1, NF4, NF7, NF8, NF9, NF10, NF11) cell lines. The patients were matched for ethnicity and age. The majority of patients in both groups were white Caucasians: 7 white Caucasians (70%), 1 Asian, and 2 Afro-Caribbeans in the FF group; 6 white Caucasians (86%) and 1 Asian in the NF group (Table 1). There were also no statistically significant differences in age between the two groups with a mean age of 41.7 ± 17.1 years for FF patients and 52.0 ± 26.5 years for NF patients (p = 0.344).

Table 1.

Patient demographics for the FF and NF groups.

| Fibrotic (FF) | Non-Fibrotic (NF) | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 10 | 7 |

| Age, mean in years ± SD | 41.7 ± 17.1 | 52.0 ± 26.5 |

| Gender (M/F) | 5 M/5 F | 6 M/1 F |

| Ethnicity | 7 Caucasians | 6 Caucasians |

| 1 Asian | 1 Asian | |

| 2 Afro-Caribbeans | ||

| Type of glaucoma | 7 POAG | 3 POAG |

| 3 congenital | 3 secondary | |

| 1 congenital | ||

| Pre-operative intraocular pressures, mean in mmHg ± SD | 19.4 ± 13.0 | 27.0 ± 7.9 |

| Best-corrected visual acuity, mean in logMAR (range) | 0.7 (0 to 1) | 0.3 (0 to 0.6) |

| Cup-disc ratio, mean (range) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.0) | 0.8 (0.8 to 0.9) |

| Anti-glaucoma eye drops, mean (range) | 3.2 (0 to 5) | 3.9 (3 to 5) |

| Previous glaucoma surgeries, mean (range) | 1.7 (1 to 3) | 0 |

The FF patients had marked conjunctival fibrosis from previous glaucoma surgeries (mean = 1.7, range = 1 to 3). The mean central bleb area, maximal bleb area, bleb height, and bleb vascularity were 1.8 ± 1.0, 1.8 ± 1.0, 1.7 ± 0.8, and 3.7 ± 1.0, respectively. The FF group had worse best-corrected visual acuity with a mean logMAR vision of 0.7 compared to 0.3 for the NF group (p = 0.028). The FF patients also had a mean pre-operative intraocular pressure (IOP) of 19.4 ± 13.0 mmHg while the NF patients had a mean pre-operative IOP of 27.0 ± 7.9 mmHg (p = 0.191). All patients had advanced optic disc cupping with a mean cup-disc ratio of 0.9 and 0.8 in the FF and NF groups, respectively (p = 0.313).

RNA-Seq analysis identifies a distinct fibrosis gene signature in the conjunctiva

We extracted high quality RNA from all the fibroblast cell lines (RNA integrity number equivalent ≥9.8). Table 2 shows the total reads sequenced, the intragenic/exonic/intronic/intergenic rates, the number of genes detected, and the mean coverage in each sample. We identified a distinct fibrosis gene expression profile in the conjunctiva after glaucoma surgery (Fig. 1A). A total of 246 genes were differentially expressed in fibrotic fibroblast (FFs) cell lines compared to non-fibrotic fibroblast (NFs) cell lines with more than a two-fold change and which were statistically significant (p < 0.05; Table S1). Out of the 246 genes, 46 genes were upregulated and 200 genes were downregulated in FFs compared to NFs. The reason for the significantly larger number of downregulated compared to upregulated genes might be because many genes encoding the large family of extracellular matrix proteins, growth factors, signalling molecules, and tumour suppressor genes were significantly downregulated in FFs compared to NFs.

Table 2.

The total reads sequenced, the intragenic/exonic/intronic/intergenic rates, and the number of genes detected in each sample are presented here.

| Sample | Total reads sequenced | Mapped | Mapped unique | Intragenic rate | Exonic rate | Intronic rate | Intergenic rate | Genes detected | Mean coverage-High | Mean coverage-Medium | Mean coverage-Low |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FF3 | 42023726 | 37592844 | 27995882 | 0.948 | 0.884 | 0.065 | 0.052 | 15674 | 376.99 | 16.37 | 3.82 |

| FF10 | 37112186 | 30779958 | 22735702 | 0.926 | 0.862 | 0.065 | 0.073 | 15421 | 371.14 | 12.91 | 3.24 |

| FF13 | 18788002 | 16758670 | 13529630 | 0.945 | 0.884 | 0.061 | 0.054 | 14611 | 212.97 | 7.47 | 1.73 |

| FF14 | 59651682 | 54662138 | 36210246 | 0.947 | 0.885 | 0.062 | 0.052 | 16031 | 532.51 | 22.87 | 5.98 |

| FF15 | 34965998 | 32923072 | 24999524 | 0.948 | 0.886 | 0.062 | 0.052 | 15355 | 366.59 | 14.58 | 3.41 |

| FF16 | 45049566 | 41338508 | 28216626 | 0.944 | 0.854 | 0.089 | 0.056 | 15742 | 395.65 | 15.88 | 3.93 |

| FF17 | 42367044 | 38687824 | 26996622 | 0.930 | 0.865 | 0.066 | 0.070 | 15508 | 408.80 | 16.06 | 4.01 |

| FF18 | 38247446 | 35096216 | 22061352 | 0.932 | 0.873 | 0.059 | 0.068 | 15612 | 340.66 | 12.77 | 3.01 |

| FF20 | 45156828 | 41265828 | 28362946 | 0.938 | 0.872 | 0.066 | 0.062 | 16034 | 399.06 | 16.36 | 3.98 |

| FF21 | 62590502 | 54318504 | 35711252 | 0.943 | 0.877 | 0.065 | 0.057 | 16030 | 506.28 | 21.60 | 5.31 |

| NF1 | 46016224 | 40107626 | 28253026 | 0.926 | 0.862 | 0.064 | 0.074 | 16032 | 395.65 | 16.10 | 4.07 |

| NF4 | 39105994 | 36621378 | 27604732 | 0.929 | 0.871 | 0.059 | 0.070 | 15517 | 386.04 | 14.99 | 3.64 |

| NF7 | 51543864 | 47002456 | 33462460 | 0.937 | 0.875 | 0.062 | 0.063 | 16027 | 444.52 | 19.48 | 4.56 |

| NF8 | 39174808 | 35558266 | 26244832 | 0.925 | 0.864 | 0.061 | 0.075 | 15803 | 381.37 | 14.67 | 3.54 |

| NF9 | 44996604 | 40845860 | 29106082 | 0.919 | 0.855 | 0.063 | 0.081 | 15878 | 383.28 | 16.38 | 3.86 |

| NF10 | 51037730 | 45634882 | 32393242 | 0.933 | 0.867 | 0.066 | 0.067 | 15735 | 466.67 | 18.78 | 4.39 |

| NF11 | 46797824 | 43182836 | 31797826 | 0.938 | 0.874 | 0.063 | 0.062 | 15951 | 426.46 | 18.68 | 4.24 |

High, medium, and low mean coverage calculations are based on the top 1000, middle 1000, and bottom 1000 expressed transcripts, respectively.

Figure 1.

(A) Heat map of differentially expressed genes between FFs and NFs. The 100 genes shown in the heat map were selected as being the most significant changes, i.e. sorted by p values with the smallest and most significant at the top. The genes were clustered using hierarchical average linkage clustering and euclidean distances using the R package for Nonnegative Matrix Factorization (NMF)75. (B) Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using DESeq2 on the regularised log transformed count data.

Principal component analysis revealed tight clustering of FFs whereas there was more variability in NFs (Fig. 1B). As ethnicity can affect the wound healing response after glaucoma surgery, we also performed an additional Caucasian FF-Caucasian NF comparison (Fig. 2). The majority of patients in our cohort were white Caucasians and we found a large overlap (175 out of the 246 genes) between the ‘all patients’ and ‘white Caucasians’ group comparisons (Table S2).

Figure 2.

Venn diagram listing shared and unique genes in the ‘all patients’ and ‘white Caucasians’ groups. Percentages of patients are shown in brackets.

Gene Ontology Analysis

We next carried out detailed GO (gene ontology) enrichment analysis of the 246 differentially expressed genes (Table S4). Figure S3 shows the directed acyclic graph (DAG) view of the GO analysis. Enriched ontology groups shown in red included regulation of smooth muscle contraction, proteinaceous extracellular matrix, regulation of secretion, the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade, and angiogenesis. For the biological process, smooth muscle contraction and muscle contraction were enriched ontology groups (Fig. 3A). The MYOCD gene encodes myocardin, a smooth muscle-specific transcriptional co-activator of serum response factor (SRF), and its expression was significantly upregulated in FFs compared to NFs (Table S1). The CHRM3 gene encodes a muscarinic acetylcholine receptor M3 that causes smooth muscle contraction and its expression was also significantly increased in FFs compared to NFs.

Figure 3.

Enriched gene ontology groups: (A) Biological process, (B) Cellular component, (C) Molecular function. The differentially expressed genes list was analysed using ClueGo in Cytoscape. Gene node shading indicates shared associations with each term.

For the cellular component, proteinaceous extracellular matrix and secretory granule were enriched ontology groups (Fig. 3B). Among the proteinaceous extracellular matrix, the COL6A6 gene and the P4HA3 gene that encodes prolyl 4-hydroxylase, a key enzyme in collagen synthesis, were significantly downregulated in FFs compared to NFs. The MMP-10, MMP-12 and MMP-24 genes encode matrix metalloproteinases and their expression were also significantly decreased in FFs compared to NFs. The FBLN1 gene encodes the extracellular matrix component, fibulin-1, and was significantly downregulated in FFs compared to NFs. For the regulation of secretion, the IL-6 gene was significantly upregulated whereas the IL-33 and CD34 genes were downregulated in FFs compared to NFs (Table S4).

For the molecular function, growth factor binding and insulin-like growth factor binding were enriched ontology groups (Fig. 3C). The FGFR3 gene encodes the fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 and was significantly downregulated in FFs compared to NFs. The IGFBP5 gene encodes insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 5 and its expression was also significantly decreased in FFs compared to NFs. The WISP2 (CCN5) gene is a new transcriptional regulator of the TGFβ signaling pathway and its expression was significantly downregulated in FFs compared to NFs. The NOV (CCN3) gene is a negative regulator of CTGF (CCN2) and its expression was also significantly decreased in FFs compared to NFs.

KEGG, Disease association, Pathway commons, WikiPathways Analyses

We also performed detailed KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes), disease association, pathway commons, and WikiPathways analyses of the 246 differentially expressed genes (Tables S5 to S8). There were many similarities between the GO analysis and the other enrichment analyses. In the KEGG pathway (ECM-receptor interaction and metabolic pathways), the COL6A6, COMP and P4HA3 genes were significantly downregulated in FFs compared to NFs (Table S5). In the KEGG pathway (MAPK signalling pathway), the RELB gene was also significantly upregulated whereas the FGFR3 and DUSP5 genes were downregulated in FFs compared to NFs.

In the disease association analysis (inflammation), the IL-6 gene expression was significantly increased whereas the IL-33 gene expression was decreased in FFs compared to NFs (Table S6). In the disease association analysis (neoplasms, cancer or viral infections, breast neoplasms, neuroblastoma), the LMO3, MYB and BIRC3 oncogenes were also significantly upregulated whereas the WISP2, IGFBP5 and RASSF2 tumour suppressor genes were significantly downregulated in FFs compared to NFs.

In addition, in the pathway commons analysis (IGF1 pathway, thrombin/protease-activated receptor pathway, signalling events), the MYOCD gene was significantly upregulated in FFs compared to NFs (Table S7). In the pathway commons analysis (IGF1 pathway, IFN-gamma pathway, IL3-mediated signalling events), the IL-6, RELB and PPP1R13L gene expression was also significantly increased whereas the DUSP5 and FGFR3 gene expression was decreased in FFs compared to NFs.

In the WikiPathways analysis (matrix metalloproteinases), the MMP-10, MMP-12 and MMP-24 genes were significantly downregulated in FFs compared to NFs (Table S8). In the WikiPathways analysis (myometrial relaxation and contraction pathways), the IL-6 gene expression was also significantly increased whereas the IGFBP5 gene expression was decreased in FFs compared to NFs.

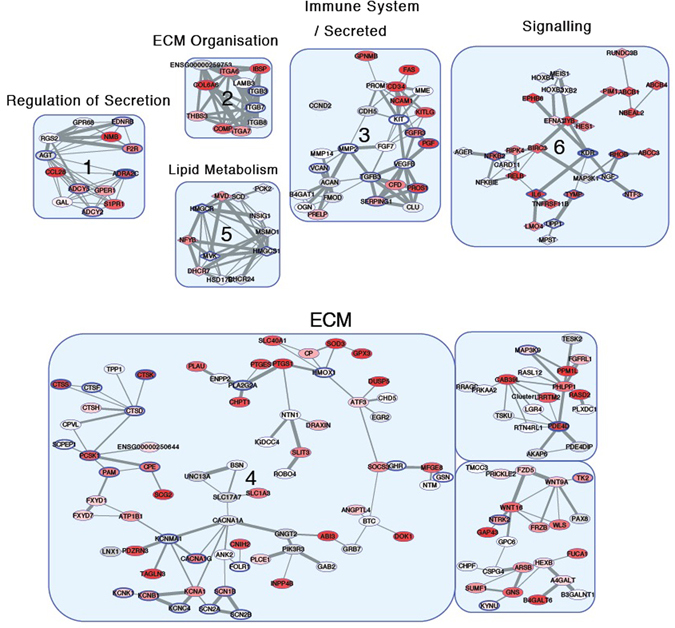

Protein Network Analysis

We further implemented a novel network analysis method utilising the STRING v10 network data to identify clusters of genes showing similar significant sets of gene associations and similar patterns of differential expression (Table S9). This strategy allows us to leverage the large amount of information held in the STRING database to further characterise the RNA-Seq data by looking for shared neighbourhoods in the STRING network that show similar differential expression. Since this network-based method does not use discrete groups (pathway groupings)‚ as applied to the standard enrichment approach, it can provide a complimentary and more global view on the gene expression changes.

Like the GO analysis, extracellular organisation and components were also enriched in clusters 2 and 4 of the network clustering analysis (Fig. 4). The COL6A6, COMP, PRG4, FBLN1 and P4HA3 genes were significantly downregulated in FFs compared to NFs (Table S9). Several matrix metalloproteinases genes (MMP-2, MMP-10, MMP-14, MMP-15, MMP-24) were also downregulated in FFs compared to NFs. In addition, inflammatory cytokines and immune mediators were enriched in clusters 3 and 6 of the network clustering analysis. The IL-6, RELB, PPP1R13L and NFKB2 genes were significantly upregulated in FFs compared to NFs (Table S9). Conversely, the IL-33 and CD34 gene expression were significantly decreased in FFs compared to NFs. In cluster 4, the DUSP5 gene negatively regulates members of the MAPK family that are associated with cellular proliferation and differentiation and its expression was significantly decreased in FFs compared to NFs.

Figure 4.

High-level modules were identified by a network clustering algorithm (see methods) using the STRING network data. Redness-fill of a node corresponds to the adjusted p value from the RNA-Seq analysis (redder nodes have lower p values). Diamonds correspond to upregulated genes whilst ellipses correspond to downregulated genes in FFs compared to NFs. The thickness of the node boundary corresponds to the number of drugs available to bind the protein. The GO term most strongly associated with the cluster is shown in the label. ECM = Extracellular matrix.

In cluster 6 of the network clustering analysis, the MYOCD and CHRM3 genes were also significantly upregulated in FFs compared to NFs (Table S9). In clusters 3 and 4, the FGFR3 and IGFBP5 genes were downregulated in FFs compared to NFs. Moreover, we found several genes associated with cancer to be differentially expressed in FFs compared to NFs. In cluster 6, the LMO3, MYB, and BIRC3 oncogenes were significantly upregulated in FFs compared to NFs. The WISP2, IGFBP5 and RASSF2 genes are tumour suppressor genes and were also significantly downregulated in FFs compared to NFs in cluster 4 of the network clustering analysis.

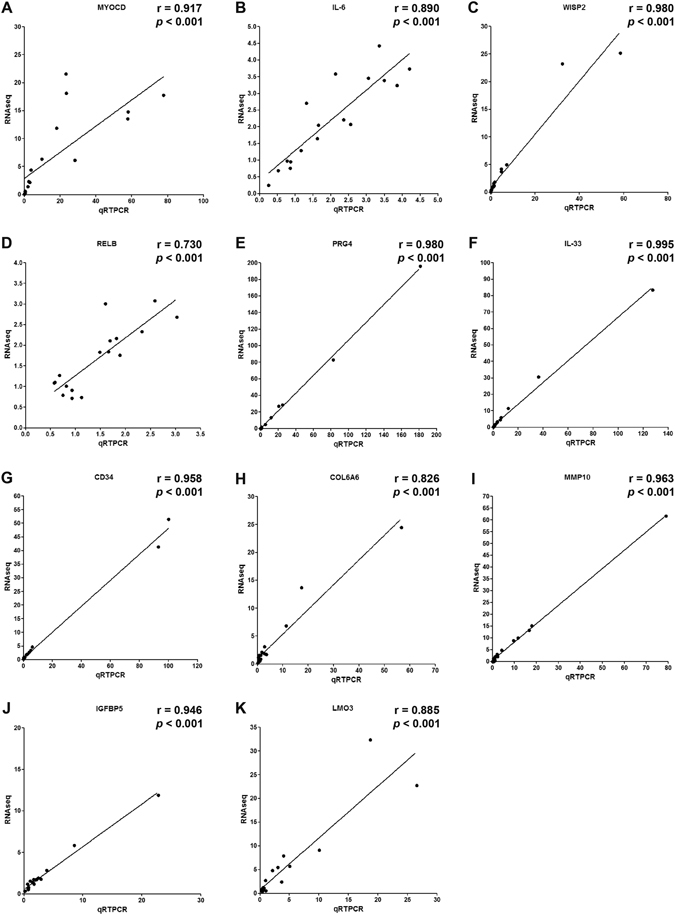

Validation by Real-time quantitative PCR

We further validated 11 selected genes that were highly upregulated or downregulated in the RNA-Seq analysis using real-time qPCR (Table 3). For the upregulated genes, the MYOCD, LMO3, IL-6 and RELB gene expression were significantly increased in the RNA-Seq and RT-qPCR results. For the downregulated genes, the PRG4, CD34, IL-33, MMP-10, WISP2, COL6A6 and IGFBP5 gene expression were significantly decreased in the RNA-Seq and RT-qPCR results.

Table 3.

Validation of highly upregulated or downregulated genes using real-time quantitative PCR.

| Gene | RT-qPCR | RNA-Seq | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fold change (FF vs NF) | p value | Fold change (FF vs NF) | p value | |

| MYOCD | +30.22** | 0.005 | +11.45** | 0.006 |

| LMO3 | +7.11* | 0.046 | +9.13** | 0.003 |

| IL-6 | +2.70** | 0.001 | +3.04*** | 0.0003 |

| RELB | +1.74* | 0.017 | +2.14** | 0.001 |

| PRG4 | −47.62* | 0.023 | −49.61*** | 0.0006 |

| CD34 | −28.57* | 0.033 | −14.75** | 0.003 |

| IL-33 | −27.78* | 0.043 | −19.90*** | 0.0005 |

| MMP-10 | −20.06* | 0.018 | −16.54*** | 0.0003 |

| WISP2 | −15.15* | 0.027 | −8.78** | 0.009 |

| COL6A6 | −13.39* | 0.033 | −7.41*** | 0.0008 |

| IGFBP5 | −6.29* | 0.022 | −3.94** | 0.002 |

All mRNA values were normalised relative to that of GAPDH and triplicate experiments were performed for each gene. Statistically significant differences were expressed as *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

We also studied the correlation between the RNA-Seq and RT-qPCR analyses and found a strong correlation between the two sets of results. The Spearman correlation coefficient (r) was 0.917 (p < 0.001) for the MYOCD gene, 0.890 (p < 0.001) for the IL-6 gene, 0.980 (p < 0.001) for the WISP2 gene, 0.730 (p < 0.001) for the RELB gene, 0.980 (p < 0.001) for the PRG4 gene, 0.995 (p < 0.001) for the IL-33 gene, 0.958 (p < 0.001) for the CD34 gene, 0.826 (p < 0.001) for the COL6A6 gene, 0.963 (p < 0.001) for the MMP-10 gene, 0.946 (p < 0.001) for the IGFBP5 gene, and 0.885 (p < 0.001) for the LMO3 gene (Fig. 5A to K).

Figure 5.

The Spearman’s correlation r and corresponding p values of the RNA-Seq and RT-qPCR results were performed using the mean values obtained from all samples normalised to either NFs or FFs: (A) MYOCD, (B) IL-6, (C) WISP2, (D) RELB, (E) PRG4, (F) IL-33, (G) CD34, (H) COL6A6, (I) MMP-10, (J) IGFBP5, (K) LMO3 genes.

Discussion

Here we present the first genome-wide RNA-Sequencing study in human conjunctival fibrosis. We have studied the differentially expressed genes between fibrotic and non-fibrotic primary human conjunctival fibroblast cell lines from patients with and without previous glaucoma surgery, respectively. Previous microarray studies in the rabbit7 and rat8 eyes have reported 315 and 923 significantly altered genes after glaucoma filtration surgery, respectively. There has only been one human study of seven capsules of failed glaucoma valves using the RT² Profiler PCR Array, and the authors have found that 39 of the 84 tested genes had more than two-fold differential gene expression in three or more of the Tenon’s capsules9. Common genes between the three studies and our study include extracellular matrix components and matrix metalloproteinases.

We found that the MYOCD gene was significantly upregulated in FFs compared to NFs. Myocardin is a critical cofactor of serum response factor (SRF) in the transcriptional program regulating smooth muscle cell differentiation10, and can activate smooth muscle gene expression in a variety of non-muscle cell types via its association with SRF11. Myofibroblasts are contractile smooth muscle-like cells that control tissue repair and remodelling, and persistent myofibroblast activation is associated with pathological fibrosis and scarring12–14. Alpha smooth muscle actin (αSMA) is also a classical smooth muscle target gene of MYOCD and SRF15, 16, and αSMA expression upregulates fibroblast contractile activity17. SRF is a master regulator of cytoskeletal gene expression18, 19, and the Myocardin-related transcription factor/Serum response factor (MRTF/SRF) pathway has been linked to ocular20–22, vascular23, skin24, and lung fibrosis25.

Fetal skin wound healing is scarless and fundamentally different from adult wound healing26–29. Scarless fetal wound healing is characterised by decreased levels of potent inflammatory cytokines such as IL-630, and the IL-6 gene was significantly upregulated in FFs compared to NFs. Scarless fetal wound healing is also associated with high levels of hyaluronic acid27, 28 that increases the expression of proteoglycan 4 (PRG4)31. Similarly, our results show that the PRG4 gene was significantly upregulated in NFs compared to FFs. IL-6 controls the effector characteristics of various T cell subsets including Th17 cells, Th22 cells32, and also plays an important role in trachomatous conjunctival fibrosis33, pulmonary fibrosis34, peritoneal fibrosis35, renal interstitial fibrosis36, and cancer-associated fibroblasts37. Conversely, the IL-33 gene was significantly downregulated in FFs compared to NFs. IL-33 has a protective effect and reduces cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis after experimental myocardial infarction through ST2 signalling38.

Furthermore, we found that the RELB and PPP1R13L genes were significantly upregulated in FFs compared to NFs. The RELB gene is part of the NFkB family, which is a master regulator of inflammation and cell death in fibrosis39. The PPP1R13L gene encodes a RELA-associated inhibitor that decreases p53/TP53 function and therefore suppresses the subsequent activation of apoptosis40. The DUSP5 gene was also significantly downregulated in FFs, and methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2) increases the proliferation of cardiac fibroblasts and fibrosis by downregulating DUSP541. In addition, we found that the CD34 gene was significantly upregulated in NFs compared to FFs and human peripheral blood CD34+ cell transplantation can halt liver fibrosis and promote hepatic regeneration in chronic liver injury42.

In terms of growth factor binding, the IGFBP5 and FGFR3 genes were significantly downregulated in FFs compared to NFs. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 5 (IGFBP5) reduces liver fibrosis in chronic cholangiopathy43. The fibroblast growth factor 9 (FGF9) and 18 (FGF18) also inhibit myofibroblast differentiation in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and their biological effects are partially driven by FGFR344. The CCN family of genes also represents matricellular proteins that modify signalling of other molecules, specifically those associated with the extracellular matrix. The NOV (CCN3) and WISP2 (CCN5) genes were both significantly downregulated in FFs compared to NFs. NOV (CCN3) is a negative regulator of CTGF (CCN2) and a new endogenous inhibitor of the fibrotic pathway in an in vitro model of renal disease45. WISP2 (CCN5) is also a novel transcriptional regulator of the TGFβ signalling pathway46 and inhibits cardiac fibrosis47 as well as cell proliferation and motility in smooth muscle cells48, 49.

In addition, several extracellular matrix components were differentially expressed in FFs compared to NFs. The PRG4 and FBLN1 genes encode proteoglycan 4 and fibulin-1, respectively, and were significantly downregulated in FFs and in palmar fascia fibroblasts from patients with Dupuytren’s contracture50. Recombinant human PRG4 has anti-fibrotic effects and also decreases αSMA expression in lens epithelial cells activated with TGFβ251. Scarless fetal wound healing is characterised by rapid and highly organised collagen deposition27–29 and we found a significant upregulation of the COL6A6 gene in NFs. The MMP-10, MMP-12 and MMP-24 genes were also significantly downregulated in FFs. The decrease in the MMP-10 gene could be explained by the fact that the IL-6 gene was significantly upregulated in FFs and IL-6 decreases MMP-10 gene expression via the JAK2/STAT3 pathway52.

Fibrosis and cancer also share many cellular and molecular pathophysiological mechanisms, namely genetic and epigenetic changes, matrix contraction and remodelling, altered regulation of apoptosis, inflammation, and angiogenesis. It could in fact be argued that fibrosis and cancer represent a spectrum of the same disease and that fibrotic tissues have an increased risk of becoming cancerous compared to non-fibrotic tissues. Several oncogenes (LMO3, MYB, BIRC3) were significantly upregulated in FFs compared to NFs. The LMO3 gene is a neuroblastoma-associated oncogene53 that encodes a LIM-domain-only protein involved in self-renewal, cell cycle regulation, and metastasis54. The MYB oncogene also plays a key role in cell proliferation and differentiation55 in leukaemia56, breast cancer57, and colon cancer58. The BIRC3 gene is an inhibitor of apoptosis protein leading to apoptosis evasion59 and a predictor of aggressiveness and therapeutic resistance in glioblastoma59. Moreover, we found a significant downregulation of several tumour suppressor genes (IGFBP5, WISP2, RASSF2) in FFs compared to NFs. The IGFBP5 gene is a tumour suppressor gene in melanoma and osteosarcoma60. WISP2 is a negative regulator of growth, migration, invasion, and a tumour suppressor in colorectal61, gastric62 and breast cancers63. The RASSF2 gene is also a tumour suppressor gene in colorectal cancer64 and oral squamous cell carcinoma65.

We are setting up a fibrosis biobank of conjunctival tissues and fibroblast cell lines and we aim to validate our results in larger longitudinal studies in the future. A limitation of our study is that most of the patients in the fibrotic and non-fibrotic groups were on several anti-glaucoma eye drops and the effects of these medications on the gene expression profile remain largely unknown. This might in fact account for the degree of variability in gene expression noted among the NF cell lines. There were also both primary open angle and congenital glaucoma patients in the FF and NF groups, a lower number of females in the NF group, and the expression data were derived from primary fibroblast cell lines instead of the original conjunctival tissues. It is well established that Afro-Caribbean patients scar worse than white Caucasian patients. The majority of patients in our cohort were however white Caucasians and we found a large overlap of genes between the ‘all patients’ and ‘white Caucasians’ group comparisons.

In conclusion, we have identified a distinct fibrosis gene signature in the conjunctiva after glaucoma surgery. We have further mapped the differentially expressed genes to distinct pathways linked to smooth muscle contraction, inflammatory cytokines, immune mediators, extracellular matrix proteins, and oncogene expression. Several of the modules identified also contained potential drug targets that could be used to develop new anti-fibrotic treatments in the future. Fibrosis is a complex multifactorial disease and our genome-wide RNA-Seq study provides new insights into the mechanistic pathways driving the fibrotic process, as well as potential novel therapeutic targets and biomarkers of disease severity, in conjunctival fibrosis and other similar contractile scarring conditions in the eye and other tissues.

Methods

Patient Recruitment

We prospectively recruited glaucoma patients at the Moorfields Eye Hospital (London, UK) from September 2014 to September 2015, and collected conjunctival tissues at the time of glaucoma filtration surgery. All experimental protocols were approved by the London-Dulwich research ethics committee (REC reference 10/H0808/127) and the institutional approval committee at the University College London Institute of Ophthalmology. All the methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines. All patients also gave written informed consent and the study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The inclusion criteria were: age (over 18 year-old) and patients planned to have glaucoma tube surgery. The exclusion criteria were previous conjunctival surgery other than glaucoma surgery. Patients were divided into 2 groups: patients who had previous glaucoma surgery and patients with no previous glaucoma surgery.

Clinical Phenotype

We collected detailed clinical data on each patient, including age, ethnicity, gender, best-corrected visual acuity, intraocular pressures, cup-disc ratio, previous glaucoma surgeries, and anti-glaucoma medications. We also assessed each patient using the Moorfields bleb grading system. Central and maximal bleb areas and bleb height were graded on a scale of 1 to 5 (1 = 0%, 2 = 25%, 3 = 50%, 4 = 75%, 5 = 100%). Bleb vascularity was graded on a scale of 1 to 5 (1 = avascular, 2 = normal, 3 = mild hyperaemia, 4 = moderate hyperaemia, 5 = severe hyperaemia).

Fibroblast Cell Lines

We established fibrotic fibroblast (FF) and non-fibrotic fibroblast (NF) primary cell lines from conjunctival tissues collected from patients with previous glaucoma surgery and patients with no previous glaucoma surgery, respectively. The conjunctival tissues were mechanically dispersed and the tissue fragments were placed in tissue culture dishes with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Invitrogen), 10% fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine at 37 °C with 5% CO2 as previously described66. Following outgrowth from the explant, the fibroblasts were trypsinised and cultured routinely in the above medium. Fibroblast cell lines in early passages 1–2 were used in the experiments.

RNA Sequencing

The RNA was extracted from each fibroblast cell line using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA sequencing was performed at the UCL Genomics facility (London, UK) using TruSeq RNA Library Prep kit v2 (http://www.illumina.com/products/by-type/sequencing-kits/library-prep-kits/truseq-rna-v2.html). RNA quality was measured using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA) and each sample was graded using an RNA integrity number equivalent (RINe) between 1 and 10. We used 500 ng of total RNA as input, based on quantification by the Agilent TapeStation RNA assay. Libraries were multiplexed into a single pool and sequenced across all four lanes of an Illumina NextSeq 500. Paired-end sequences of 43 nucleotides were generated after adapter removal.

Differential Expression Analysis

The FASTQ files were assessed for quality control using FASTQC 0.11.2 (http://www.bioinformatics.bbsrc.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). Adapter sequences were removed using Trimgalore (0.43) (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore/). Paired-end sequence reads were aligned to the human GRCh38.p3 release 82 reference transcriptome and genome using STAR 2.4.2a67. Counts were summarised using HTSeq 0.6.168 after read duplicates were marked using Picard MarkDuplicates (http://www.broadinstitute.github.io/picard) and subsequently removed using Samtools69. Differential expression analysis was performed between FF and NF sample groups based on summarised read counts using the DESeq2 (1.12.3) package70. Prior to modelling with DESeq2, read counts from the sex chromosomes were removed. DESeq2 utilises a negative binomial generalised linear model and normalised sample size through the packages median-of-ratios method. Read counts were fit to a model where condition is the factor of interest: FF and NF levels. Resulting p values were adjusted for multiple testing, as part of the DESeq2 analysis, using Benjamini-Hochberg correction71. Genes with more than a 2-fold change in expression and an adjusted p value < 0.05 were denoted as differentially expressed.

Gene Ontology, KEGG, Disease association, Pathway commons, and WikiPathways Analyses

We used the list of differentially expressed genes to perform GO (gene ontology), KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes), disease association, pathway commons, and WikiPathways analyses using WebGestalt72 and ClueGo73 with Cytoscape74 for visualisation.

Protein Network Analysis

The set of genes that were differentially expressed (with an adjusted p value < 0.1) were used to build a sub-graph of the string network (https://string-db.org/). The sub-graph was converted into a weighted adjacency matrix, where the weights were derived from the STRING v10 confidence score (range 0 to 1000) of a functional association. Diagonal elements of the matrix, i.e. self-similarities, were set to a maximum confidence score of 1000. Functional association scores between proteins in the adjacency matrix were multiplied by -1 if the genes had opposite directions of expression fold change. A Euclidean distance matrix (between each column vector) was then generated between the columns of the adjacency matrix. A low value (distance) in the resulting distance matrix indicates that the two genes have similar interaction partners and direction of differential expression. We next applied agglomerative clustering to the distance matrix using the Ward metric. We assigned a high level function to each cluster by its most significant enrichment, using Fishers exact test enrichment (one of: extracellular matrix organisation, extracellular matrix, secreted, immune system process, signalling, immune response, response to stress, regulation of secretion by cell, immune system process, cell communication). The Function-Gene assignments were obtained from Ensembl-BioMart GO annotations, except for ‘secreted’ class, which was obtained from Ensembl-BioMart Signal-P predictions. Visual inspection suggested an appropriate number of clusters for further analysis as six, which gave a cophenetic distance of 0.69. The clusters were then imported into Cytoscape where the major connected components using the STRING interaction data from each cluster were displayed.

Real-Time quantitative PCR

RT-qPCR reactions were performed using a Platinum quantitative PCR master mix (ThermoFisher Scientific, Hemel Hempstead, UK) on a CFX Real-Time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, Hemel Hempstead, UK). The Taqman gene expression assays were: MYOCD (Hs00538071_m1), IL-6 (Hs00985639_m1), IL-33 (Hs00369211_m1), WISP2 (Hs00180242_m1), PRG4 (Hs00981633_m1), CD34 (Hs02576480_m1), RELB (Hs00232399_m1), IGFBP5 (Hs00181213_m1), MMP-10 (Hs00233987_m1), COL6A6 (Hs01029204_m1), LMO3 (Hs00998696_m1), and GAPDH (Hs02758991_g1) (ThermoFisher Scientific, Hemel Hempstead, UK). All mRNA values were normalised relative to that of GAPDH and triplicate experiments were performed for each gene. Statistical analysis was performed using the Student’s t-test to calculate statistically significant differences and individual p values. The validation of the RNA-Seq data with RT-qPCR was performed using the Spearman’s correlation of the mean values obtained from all samples normalised to either NF or FF samples. Statistically significant differences were expressed as *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

Our research is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, the Medical Research Council, Moorfields Eye Charity, RP Fighting Blindness, Sunrise K Foundation, and BBSRC.

Author Contributions

C.Y. recruited the patients, generated the fibroblast cell lines, performed the experiments, analysed the data, and wrote the manuscript. N.O., J.L., A.T. performed the experiments, analysed the data, and contributed to the manuscript. P.T.K., C.O., A.W., S.H. supervised the project, gave technical support, and edited the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-05780-5

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Addicks EM, Quigley HA, Green WR, Robin AL. Histologic characteristics of filtering blebs in glaucomatous eyes. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983;101:795–798. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1983.01040010795021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Broadway D, Grierson I, Hitchings R. Racial differences in the results of glaucoma filtration surgery: are racial differences in the conjunctival cell profile important? Br J Ophthalmol. 1994;78:466–475. doi: 10.1136/bjo.78.6.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown JJ, Ollier WE, Thomson W, Bayat A. Positive association of HLA-DRB1*15 with keloid disease in Caucasians. Int J Immunogenet. 2008;35:303–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313X.2008.00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu-Wai-Man C, Khaw PT. Personalised medicine in ocular fibrosis: myth or future biomarkers. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2016;5:390–402. doi: 10.1089/wound.2015.0677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat Methods. 2008;5:621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Z, Gerstein M, Snyder M. RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nrg2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Popp MP, et al. Development of a microarray chip for gene expression in rabbit ocular research. Mol Vis. 2007;13:164–173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esson DW, Popp MP, Liu L, Schultz GS, Sherwood MB. Microarray analysis of the failure of filtering blebs in a rat model of glaucoma filtering surgery. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:4450–4462. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahale A, et al. Altered expression of fibrosis genes in capsules of failed Ahmed glaucoma valve implants. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0122409. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du KL, et al. Myocardin is a critical serum response factor cofactor in the transcriptional program regulating smooth muscle cell differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:2425–2437. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.7.2425-2437.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Z, Wang DZ, Pipes GC, Olson EN. Myocardin is a master regulator of smooth muscle gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:7129–7134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232341100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wynn TA. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of fibrosis. J Pathol. 2008;214:199–210. doi: 10.1002/path.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hinz B. Formation and function of the myofibroblast during tissue repair. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:526–537. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eyden B. The myofibroblast: phenotypic characterization as a prerequisite to understanding its functions in translational medicine. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12:22–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00213.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li L, Liu Z, Mercer B, Overbeek P, Olson EN. Evidence for serum response factor-mediated regulatory networks governing SM22alpha transcription in smooth, skeletal, and cardiac muscle cells. Dev Biol. 1997;187:311–321. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim S, Ip HS, Lu MM, Clendenin C, Parmacek MS. A serum response factor-dependent transcriptional regulatory program identifies distinct smooth muscle cell sublineages. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2266–2278. doi: 10.1128/MCB.17.4.2266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hinz B, Celetta G, Tomasek JJ, Gabbiani G, Chaponnier C. α-smooth muscle actin expression upregulates fibroblast contractile activity. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:2730–2741. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.9.2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esnault C, et al. Rho–actin signaling to the MRTF coactivators dominates the immediate transcriptional response to serum in fibroblasts. Genes Dev. 2014;28:943–958. doi: 10.1101/gad.239327.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olson EN, Nordheim A. Linking actin dynamics and gene transcription to drive cellular motile functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:353–365. doi: 10.1038/nrm2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu-Wai-Man, C. et al. Local delivery of novel MRTF/SRF inhibitors prevents scar tissue formation in a preclinical model of fibrosis. Sci Rep. 7 518, doi:10.1038/s41598-41017-00212-w (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Yu-Wai-Man, C., Tagalakis, A. D., Manunta, M. D., Hart, S. L. & Khaw, P. T. Receptor-targeted liposome-peptide-siRNA nanoparticles represent an efficient delivery system for MRTF silencing in conjunctival fibrosis. Sci Rep. 6, 21881. doi:10.21038/srep21881 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Yu-Wai-Man C, Treisman RT, Bailly M, Khaw PT. The role of the MRTF-A/SRF pathway in Ocular fibrosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:4560–4567. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-14692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minami T, et al. Reciprocal expression of MRTF-A and myocardin is crucial for pathological vascular remodelling in mice. EMBO J. 2012;31:4428–4440. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haak AJ, et al. Targeting the myofibroblast genetic switch: inhibitors of MRTF/SRF-regulated gene transcription prevent fibrosis in a murine model of skin injury. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2014;349:480–486. doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.213520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sisson TH, et al. Inhibition of Myocardin-Related Transcription Factor/Serum Response Factor Signaling Decreases Lung Fibrosis and Promotes Mesenchymal Cell Apoptosis. Am J Pathol. 2015;185:969–986. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bleacher JC, Adolph VR, Dillon PW, Krummel TM. Fetal tissue repair and wound healing. Dermatol Clin. 1993;11:677–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lorenz HP, Adzick NS. Scarless skin wound repair in the fetus. West J Med. 1993;159:350–355. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mast BA, Diegelmann RF, Krummel TM, Cohen IK. Scarless wound healing in the mammalian fetus. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1992;174:441–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Namazi MR, Fallahzadeh MK, Schwartz RA. Strategies for prevention of scars: what can we learn from fetal skin? Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:85–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liechty KW, Adzick NS, Crombleholme TM. Diminished interleukin 6 (IL-6) production during scarless human fetal wound repair. Cytokine. 2000;12:671–676. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1999.0598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo H, et al. Up-regulation of proteoglycan 4 in temporomandibular osteoarthritic synovial cells by hyaluronic acid. J Oral Pathol Med. 2015;44:622–627. doi: 10.1111/jop.12273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stumhofer JS, et al. Interleukins 27 and 6 induce STAT3-mediated T cell production of interleukin 10. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:1363–1371. doi: 10.1038/ni1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kechagia, J. Z., Ezra, D. G., Burton, M. J. & Bailly, M. Fibroblasts profiling in scarring trachoma identifies IL-6 as a functional component of a fibroblast-macrophage pro-fibrotic and pro-inflammatory feedback loop. Sci Rep., Jun 20;26:28261. doi: 10.21038/srep28261. (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Le TT, et al. Blockade of IL-6 Trans signaling attenuates pulmonary fibrosis. J Immunol. 2014;193:3755–3768. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fielding CA, et al. Interleukin-6 signaling drives fibrosis in unresolved inflammation. Immunity. 2014;40:40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang J, et al. Effect of interleukin 6 deficiency on renal interstitial fibrosis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52415. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Erez N, Truitt M, Olson P, Arron ST, Hanahan D. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Are Activated in Incipient Neoplasia to Orchestrate Tumor-Promoting Inflammation in an NF-kappaB-Dependent Manner. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:135–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seki K, et al. Interleukin-33 prevents apoptosis and improves survival after experimental myocardial infarction through ST2 signaling. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2:684–691. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.873240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luedde T, Schwabe RF. NF-κB in the liver–linking injury, fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:108–118. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bergamaschi D, et al. iASPP oncoprotein is a key inhibitor of p53 conserved from worm to human. Nat Genet. 2003;33:162–167. doi: 10.1038/ng1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tao H, et al. MeCP2 regulation of cardiac fibroblast proliferation and fibrosis by down-regulation of DUSP5. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;82:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.10.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakamura T, et al. Human peripheral blood CD34-positive cells enhance therapeutic regeneration of chronically injured liver in nude rats. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:1538–1552. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sokolović A, et al. Overexpression of insulin like growth factor binding protein 5 reduces liver fibrosis in chronic cholangiopathy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822:996–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Joannes A, et al. FGF9 and FGF18 in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis promote survival and migration and inhibit myofibroblast differentiation of human lung fibroblasts in vitro. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2016;310:L615–629. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00185.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Riser BL, et al. CCN3 (NOV) is a negative regulator of CCN2 (CTGF) and a novel endogenous inhibitor of the fibrotic pathway in an in vitro model of renal disease. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:1725–1734. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sabbah M, et al. CCN5, a novel transcriptional repressor of the transforming growth factor β signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:1459–1469. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01316-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoon PO, et al. The opposing effects of CCN2 and CCN5 on the development of cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49:294–303. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lake AC, Bialik A, Walsh K, Castellot JJJ. CCN5 is a growth arrest-specific gene that regulates smooth muscle cell proliferation and motility. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:219–231. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63813-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mason HR, Lake AC, Wubben JE, Nowak RA, Castellot JJJ. The growth arrest-specific gene CCN5 is deficient in human leiomyomas and inhibits the proliferation and motility of cultured human uterine smooth muscle cells. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10:181–187. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Satish, L. et al. Identification of differentially expressed genes in fibroblasts derived from patients with Dupuytren’s Contracture. BMC Med Genomics1 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 51.Bowman, S. A., Regmi, S., Schmidt, T. A. & West-Mays, J. A. Effect of Proteoglycan 4 treatment on focal adhesions of lens epithelial cells during TGFβ-induced EMT. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci., ARVO meeting, Poster number 2019 (2016).

- 52.Zhang X, et al. IL-6 regulates MMP-10 expression via JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway in a human lung adenocarcinoma cell line. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:4497–4501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aoyama M, et al. LMO3 interacts with neuronal transcription factor, HEN2, and acts as an oncogene in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4587–4597. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matthews JM, Lester K, Joseph S, Curtis DJ. LIM-domain-only proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:111–122. doi: 10.1038/nrc3418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oh IH, Reddy EP. The myb gene family in cell growth, differentiation and apoptosis. Oncogene. 1999;18:3017–3033. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pelicci PG, Lanfrancone L, Brathwaite MD, Wolman SR, Dalla-Favera R. Amplification of the c-myb oncogene in a case of human acute myelogenous leukemia. Science. 1984;224:1117–1121. doi: 10.1126/science.6585957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Drabsch Y, et al. Mechanism of and requirement for estrogen-regulated MYB expression in estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:13762–13767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700104104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alitalo K, et al. Aberrant expression of an amplified c-myb oncogene in two cell lines from a colon carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:4534–4538. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.14.4534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang, D. et al. BIRC3 is a novel driver of therapeutic resistance in Glioblastoma. Sci Rep, Feb 18;16:21710. doi: 10.21038/srep21710 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Su Y, et al. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5 suppresses tumor growth and metastasis of human osteosarcoma. Oncogene. 2011;30:3907–3917. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Frewer KA, et al. A role for WISP2 in colorectal cancer cell invasion and motility. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2013;10:187–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ji J, et al. WISP-2 in human gastric cancer and its potential metastatic suppressor role in gastric cancer cells mediated by JNK and PLC-γ pathways. Br J Cancer. 2015;113:921–933. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Banerjee S, et al. WISP-2 gene in human breast cancer: estrogen and progesterone inducible expression and regulation of tumor cell proliferation. Neoplasia. 2003;5:63–73. doi: 10.1016/S1476-5586(03)80018-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Akino K, et al. The Ras effector RASSF2 is a novel tumor-suppressor gene in human colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:156–169. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Imai T, et al. Epigenetic inactivation of RASSF2 in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:958–966. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00769.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li H, Ezra DG, Burton MJ, Bailly M. Doxycycline prevents matrix remodeling and contraction by trichiasis-derived conjunctival fibroblasts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:4675–4682. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-11787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dobin A, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. HTSeq–a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:166–169. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li H, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang J, Duncan D, Shi Z, Zhang B. WEB-based GEne SeT AnaLysis Toolkit (WebGestalt): update 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:W77–83. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bindea G, et al. ClueGO: a Cytoscape plug-in to decipher functionally grouped gene ontology and pathway annotation networks. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1091–1093. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shannon P, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gaujoux R, Seoighe C. A flexible R package for nonnegative matrix factorization. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:367. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.