Abstract

Purpose

A phase 2 protocol was designed and implemented to assess the toxicity and efficacy of hypofractionated image guided intensity modulated radiation therapy (IG-IMRT) combined with low-dose rate 103Pd prostate seed implant for treatment of localized intermediate- and high-risk adenocarcinoma of the prostate.

Methods and materials

This is a report of an interim analysis on 24 patients enrolled on an institutional review board–approved phase 2 single-institution study of patients with intermediate- and high-risk adenocarcinoma of the prostate. The median pretreatment prostate-specific antigen level was 8.15 ng/mL. The median Gleason score was 4 + 3 = 7 (range, 3 + 4 = 7 - 4 + 4 = 8), and the median T stage was T2a. Of the 24 patients, 4 (17%) were high-risk patients as defined by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network criteria, version 2016. The treatment consisted of 2465 cGy in 493 cGy/fraction of IG-IMRT to the prostate and seminal vesicles. This was followed by a 103Pd transperineal prostate implant boost (prescribed dose to 90% of the prostate volume of 100 Gy) using intraoperative planning. Five patients received neoadjuvant, concurrent, and adjuvant androgen deprivation therapy.

Results

The median follow-up was 18 months (range, 1-42 months). The median nadir prostate-specific antigen was 0.5 ng/mL and time to nadir was 16 months. There was 1 biochemical failure associated with distant metastatic disease without local failure. Toxicity (acute or late) higher than grade 3 was not observed. There was a single instance of late grade 3 genitourinary toxicity secondary to hematuria 2 years and 7 months after radiation treatment. There were no other grade 3 gastrointestinal or genitourinary toxicities.

Conclusions

Early results on the toxicity and efficacy of the combination of hypofractionated IG-IMRT and low-dose-rate brachytherapy boost are favorable. Longer follow-up is needed to confirm safety and effectiveness.

Introduction

Conventional treatment options for patients with localized intermediate- to high-risk adenocarcinoma of the prostate include radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy (EBRT), interstitial brachytherapy with or without EBRT, and expectant management.1 Patients with higher risk disease may be treated with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) in the neoadjuvant, concurrent, and oftentimes adjuvant setting.

Dose escalation with radiation therapy has been associated with improved biochemical outcomes.2, 3, 4, 5 The concern with dose escalation is the potential for increased normal tissue toxicities. EBRT using image guided intensity modulated radiation therapy (IG-IMRT) in combination with prostate seed implant boost has been used in the setting of dose escalation while attempting to minimize normal tissue toxicity.6 Low-dose-rate (LDR) prostate seed implant allows for a conformal dose delivery over several months. EBRT with IG-IMRT provides dose to the prostate capsule, seminal vesicles with a margin of 5 to 8 mm, an area at risk for disease spread that is not routinely covered by brachytherapy alone.6

The typical dose of radiation therapy delivered in combination with seed implant is 4500 cGy of IMRT in 25 fractions. This regimen is generally well-tolerated and effective, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines also recommends this treatment option for intermediate- and high-risk cancers.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 However, a drawback for patients is the 5-week duration of IMRT, which is time-consuming, relatively expensive, and can be logistically prohibitive for some patients.

Because of advances in imaging and IMRT technology, improved treatment precision is possible, allowing for safe delivery of hypofractionated doses of radiation therapy. Several studies have demonstrated that the alpha-beta ratio for prostate cancer may be as low as 1 to 3 Gy, reflecting the slow proliferation rate of prostate cancer.7, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 In addition, the alpha-beta ratio does not alter significantly with the diagnostic risk level.23 It is proposed that, because the alpha-beta ratio of prostate cancer appears to be similar to or lower than the surrounding normal tissues, there may be an increased therapeutic ratio with higher doses per fraction.24 Current radiation therapy treatment regimens using moderately hypofractionated radiation therapy for prostate cancer in randomized trials typically deliver IMRT in 240 to 400 cGy/fraction over 4 to 6 weeks.25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 These moderately hypofractionated regimens have been reported to have similar toxicity and effectiveness compared with conventional IMRT (180-200 cGy/fraction).17 More recently, studies have assessed “extreme” hypofractionation (500-725 cGy/fraction) using stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for ≤5 days of treatment. Single institution series have showed similar efficacy and safety when compared with conventional treatment.32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37 In addition, a pooled analysis of prospective phase 2 clinical trials showed the 5-year biochemical relapse free survival rate of 95%, 84%, and 81% for low-, intermediate-, and high-risk patients, respectively.38 A systematic review of SBRT reported that this technique is more cost-effective compared with conventionally fractionated IMRT.39 At this time, the NCCN guidelines recommend that hypofractionation using SBRT be considered a cautious alternative in clinics with the technology, physics, and clinical expertise.17

The current study is designed to evaluate the tolerability and efficacy of a 5-day course of image-guided IMRT with a dose biologically equivalent to 4500 cGy in 25 fractions, followed by a Pd-103 implant. To our knowledge this is the first study adding LDR prostate seed implant boost to hypofractionated IMRT to improve the radiobiologic therapeutic ratio while maintaining reasonable patient convenience and reducing cost.

Methods and materials

Patient selection

The eligibility criteria for the study included patients at least 18 years of age with a Zubrod Performance Scale 0 to 1 and locally confined adenocarcinoma of the prostate with the following characteristics: clinical stages T1c-T2b (American Joint Committee on Cancer, 6th Edition); prostate-specific antigen (PSA) <10 combined Gleason score ≥7; PSA >10 combined Gleason score ≥6; maximum PSA ≤20. In addition, the patients had to have no significant obstructive symptoms (goal American Urological Association [AUA] scores ≤15), a pre-implant prostate volume of ≤60 mL by transrectal ultrasound, and no prior transurethral resection of the prostate. A signed study-specific informed consent form was required before study entry.

Evaluation

Each patient was evaluated at the multidisciplinary Allegheny General Hospital Prostate Center by a urologist and a radiation oncologist. An AUA Symptom Index form, a Sexual Health Inventory for Men (SHIM) potency index, and a questionnaire for rectal symptoms and urinary continence was completed by each patient before treatment. The initial evaluation consisted of a history and physical examination, digital rectal examination, and a PSA level. A prostate biopsy was obtained, and the pathology was reviewed by an Allegheny General Hospital pathologist.

ADT

The addition of ADT was left to the treating physician's discretion. The patients receiving ADT were started at least 2 months before initiation of radiation treatment and had it continue for a minimum of 4 months. ADT consisted of a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist and/or an antiandrogen approved for the treatment of adenocarcinoma of the prostate.

Treatment details

Treatment consisted of IG-IMRT to a dose of 2465 cGy in 5 daily fractions at 493 cGy/fraction, which was followed in 2 to 4 weeks by a permanent Pd-103 seed implant. Details of the dose calculation are provided in the Discussion section. The patients underwent a computed tomography (CT) simulation (3-mm cuts) with an immobilization device for their lower extremities for treatment planning. They had a full bladder and empty rectum for CT simulation and daily treatments. The clinical target volume included the prostate and the seminal vesicles. A planning target volume was created by adding a 5-mm margin in all directions. Acceptable plans included at least 98% of the planning target volume covered by the prescription dose and no hot spot exceeding 5% of the prescribed dose. Most IMRT plans were designed with 5 in-plane beams and 18-MV radiographs using the Elekta/Xio V 5.1 planning system (Elekta AB, Stockholm, Sweden). The beams were placed in a star-shaped pattern, with an anteroposterior field, 2 anterior oblique fields, and 2 posterior oblique fields. The IMRT plans are multileaf collimator-based, with a step-and-shoot method. The organs-at-risk dose constraints were the maximum femoral head dose limited to less than the prescribed dose, rectum V24 <10 mL, and bladder V20 <30%. Image guidance was performed daily with megavoltage cone beam CT. Within 2 to 4 weeks after completion of EBRT, all patients underwent transperineal prostate seed implantation under spinal or general anesthesia. Real-time intraoperative computer-assisted planning with transrectal ultrasound guidance was used. Pd-103 seeds were used for all patients. The goal was to deliver a D90 (dose to 90% of the prostate volume) of 100 Gy ± 20%. The rectal dose was limited to <0.5 mL of the rectum receiving a prescription dose. Maximum urethral dose was limited to <150% of the prescription dose. One month after the procedure, all patients underwent a noncontrast CT for postoperative dosimetry and assessment of the implant quality.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was grade 2 or higher acute and late genitourinary (GU) and gastrointestinal (GI) toxicities as well as the time to late grade 3 or higher adverse events. The secondary endpoints evaluated were biochemical failure, freedom from failure, local and regional recurrence, distant metastasis, rate of salvage ADT, prostate cancer-specific mortality, and overall survival. Biochemical failure was based on the Phoenix definition of nadir plus 2 ng/mL, without backdating.40

An interim analysis of outcomes was performed at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years after completion of treatment. Early stopping criteria were based on whether toxicities exceeded our historical standards; specifically, the results we obtained in the Allegheny General Hospital review of patients treated with 4500 cGy in 25 fractions of IG-IMRT followed by seed implant.6 To further assess acute toxicities, accession to the trial was held from the time the first 12 patients were accrued until they had been followed for a minimum of 3 months.

Toxicity

The toxicity evaluation was based on the National Cancer Institute's Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0. Late toxicity was defined as more than 360 days from the completion of radiation treatment. The patients were evaluated for toxicities weekly on treatment and then in scheduled follow-up as described later.

Follow-up

All patients were scheduled to be seen in follow-up 1 month after implant and then every 6 months for at least 10 years. At each follow up visit, the patients completed an AUA form, a SHIM potency index, and a questionnaire for rectal symptoms and urinary continence. A PSA and rectal examination were also performed.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS, version 22.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL).

Results

After informed consent and enrollment on the institutional review board–approved protocol, data were collected prospectively on 24 patients with adenocarcinoma of the prostate treated at Allegheny General Hospital between July 2011 and August 2015. The median age of the patients was 67 years (range, 53-75). The median pretreatment PSA level was 8.15 ng/mL (range, 4.2-20.9). The median Gleason score was 4 + 3 = 7 (range, 3 + 4 = 7 - 4 + 4 = 8). The Gleason score was 3 + 4 = 7 in 12 patients (50%), 4 + 3 = 7 in 10 patients (42%), and 4 + 4 = 8 in 2 patients (8%). The median T stage was T2a. The T stage was T1c in 12 patients (50%), T2a in 11 patients (46%), and T2b in 1 patient (4%). Of the 24 patients, 4 (17%) were high-risk patients as defined by the NCCN criteria, version 2016.17 The median pretreatment AUA score was 6.5, with a range of 1 to 20. The median pretreatment SHIM score was 15, with a range of 0 to 24, and was completed by 22 of the 24 patients. There were 5 (21%) patients who received ADT with radiation therapy. Table 1 demonstrates the patient characteristics. Three of the 4 high-risk patients received ADT therapy. Two intermediate-risk group patients were also started on ADT. Leuprolide through an intramuscular route was the ADT therapy in all patients. One high-risk patient received Leuprolide 30 mg, starting 4 months before radiation treatment; however, did not continue with the recommended adjuvant treatment secondary to cost. Another high-risk patient received Leuprolide 22.5 mg, starting 5 months before radiation treatment and continued it for an additional year. The last high-risk group patient received Leuprolide 22.5 mg starting about 2 months before radiation treatment and continues to receive the ADT, with the last dose scheduled so that he completes an additional year and 6 months of ADT. One of the intermediate-risk group patients received Leuprolide 30 mg starting 5 months before radiation treatment. Another intermediate-risk group patient received Leuprolide 22.5 mg, starting about 3 months before beginning radiation treatment and then refused additional adjuvant treatment.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (n = 24)

| Parameter | Median | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 67 | 53-75 |

| PSA (ng/ml) | 8.15 | 4.2-20.9 |

| Initial AUA score | 6.5 | 1-20 |

| Initial SHIM score | 15 | 0-24 |

| n | % | |

| Gleason score | ||

| 3 + 4 = 7 | 12 | 50 |

| 4 + 3 = 7 | 10 | 42 |

| 4 + 4 = 8 | 2 | 8 |

| T stage | ||

| T1c | 12 | 50 |

| T2a | 11 | 46 |

| T2b | 1 | 4 |

| NCCN risk group | ||

| Intermediate | 20 | 83 |

| High | 4 | 17 |

| Hormonal therapy | ||

| Yes | 5 | 21 |

| No | 19 | 79 |

AUA, American Urological Association; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; SHIM, Sexual Health Inventory for Men.

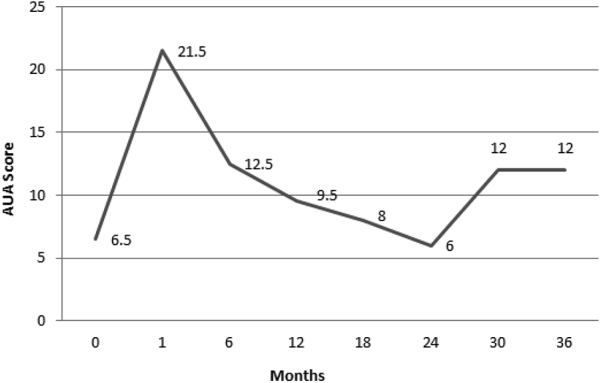

All patients completed the treatment, consisting of daily IG-IMRT to the prostate and seminal vesicles to a dose of 2465 cGy in 5 fractions, followed by a Pd-103 prostate seed implant. The median prostate seed implant D90 dose was 106.9 Gy. The median follow-up was 18 months (range, 1-42 months). The median nadir PSA was 0.5 ng/mL, with a range of 0.006 to 5.83 ng/mL. The time to PSA nadir was 16 months. At the time of analysis, the overall survival was 100%. There was 1 biochemical failure associated with distant metastatic disease without local failure in an intermediate-risk patient, for a biochemical recurrence-free survival of 96%. The median AUA scores obtained at the follow-up examinations are shown in Fig 1.

Figure 1.

The American Urological Association (AUA) scores obtained at the follow-up examination after prostate seed implant, with the pretreatment AUA scores signified by time 0.

There were no grade 3 or higher acute GI or GU toxicities or grade 3 or higher late GI toxicities. There was 1 grade 3 late GU toxicity secondary to hematuria. He was an intermediate-risk group patient receiving ADT and had a palladium seed implant dose of 119.7 Gy. He developed gross hematuria with clots 2 years and 7 months after radiation treatment. He underwent a cystoscopy and fulguration of 2 hemorrhagic spots in the prostatic urethra. His hematuria resolved shortly after this procedure. The total acute and late GI and GU toxicities classified by Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0, categories are summarized in Table 2, and are based on the documented medical record, AUA form, and the rectal and continence questionnaire.

Table 2.

Grade 2 and Grade 3 GI and GU toxicity classified by CTCAE 4.0 categories

| Toxicity | Acute (<12 months) |

Late (≥12 months) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 3 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 2 | |

| GI | ||||

| Proctitis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Anal hemorrhage | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Anal fistula | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| GU | ||||

| Urinary urgency | 3 | 1 | ||

| Urinary frequency | 14 | 11 | ||

| Hematuria | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Urinary retention | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Urinary obstruction | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 0 | 18 | 1 | 14 |

CTCAE4.0, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0; GI, gastrointestinal; GU, genitourinary.

Given limited patients with a pretreatment SHIM score ≥12 (representing a SHIM score reflecting mild to moderate erectile dysfunction) and who did not receive ADT, analysis on maintaining erectile function could not be performed.

Discussion

This publication describes the early results of the first clinical trial assessing the toxicity and efficacy of hypofractionated IMRT, 2465 cGy in 5 fractions, followed by low-dose rate prostate seed implant in patients with intermediate- and high-risk adenocarcinoma of the prostate.

The radiobiologic rationale

In radiation therapy, the alpha-beta (α/ß) ratio is a measure of the fractionation sensitivity of a particular cell type. Several studies have demonstrated that the α/ß ratio for prostate cancer is likely low, between 1 and 3 Gy, in contrast to most tumors.7, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 As a result, hypofractionated regimens may result in improved differential cell killing between the cancer and surrounding normal tissues.

To facilitate comparison between the conventional and hypofractionated schedule for the external beam radiation, biologically effective doses (BED) were calculated and the isoeffect model using the linear quadratic equation was applied. The total dose and dose per fraction in the hypofractionated schedule was calculated to give an equivalent prostate dose to 4500 cGy in 25 fractions (conventional schedule). We assumed the α/ß ratio for prostate cancer was 2 Gy and calculated the BED2Gy for the conventional schedule as 85.5 Gy2.41 Continuing the model, we determined the hypofractionation total dose equivalent to 85.5 Gy2 was 24.65 Gy2 with a fraction size of 4.93 Gy per fraction. The total BED from the combination of the prostate seed implant (Pd-103 prescribed dose 100 Gy to the D90, BED 112 Gy2)41, 42 and the hypofractionated schedule (BED 85.5Gy2) is 197.5 Gy2. In addition, the maximum biologically effective doses that could be received by the bladder and rectum in the conventional and hypofractionated schedules were also calculated. Some literature suggests the α/ß ratio for late-effect damage to the normal organs at risk (bladder and rectum) is 3 Gy, whereas others suggest 5.8 Gy and 3.9 Gy for bladder and rectal tissue, respectively.31, 43, 44 An α/ß ratio of 10 Gy was used for acute tissue response. Computations given in Table 3 were derived for each α/ß value for comparison. As demonstrated in Table 3, the BED of the hypofractionated schedule to the bladder and rectum is less than that received under the conventional schedule. In summary, we calculated a total dose using a hypofractionated external radiation schedule that delivers 2465 cGy in 5 days, which should result in similar prostatic cancer responses as a conventional schedule of 4500 cGy delivered over 25 days without compromising acute or late normal tissue reactions.

Table 3.

Schedule for equivalent effects as 4500cGy in 25 days at 1.8Gy/fx

| Tissue | BEDconv | Total dosehypofx | Dose/fx (Gy/fx) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prostate tumor (α/ß = 2.0 Gy) | 8544cGy2 |

2465cGy |

4.93 |

|

| BEDcGy-conv |

BEDcGy-hypofx |

Conventional |

Hypofx |

|

| Acute-effect tissue at risk | ||||

| Bladder (α/ß = 10 Gy) | 5310 | 3682 | 1.8 | 4.93 |

| Rectum (α/ß = 10 Gy) | 5310 | 3682 | 1.8 | 4.93 |

| Late-effect tissue at risk | ||||

| Bladder (α/ß = 3.0 Gy) | 7200 | 6530 | 1.8 | 4.93 |

| Bladder (α/ß = 5.8 Gy) | 5890 | 4562 | ||

| Rectum (α/ß = 3.0 Gy) | 7200 | 6530 | 1.8 | 4.93 |

| Rectum (α/ß = 3.9 Gy) | 6577 | 5583 | ||

BED, biologically effective dose; BEDconv, conventional schedule BED; BEDcGy-conv, BED of the conventional schedule; BEDcGy-hypofx, BED of the hypofractionated schedule; Fx, fraction; hypofx, hypofractionated; total dosehypofx, total dose of hypofractionated schedule.

Dose escalation

In our study, we speculated that dose escalation to a BED of 197.5 Gy2 with the combined LDR prostate seed implant and the hypofractionated EBRT may improve freedom from biochemical failure because randomized trials suggested that dose escalation is associated with improved biochemical outcomes.2, 3, 4, 5 In a retrospective review, Stock et al found a significant improvement in 10-year freedom from biochemical failure of 87% with BED >150 Gy2 compared with 78% with BED ≤150 Gy2 in patients receiving ADT. They also reported that with a BED >200 Gy2, hormonal therapy provided no increased benefit, though in the highest risk patients, hormone therapy may still provide a systemic advantage.45 Despite the dose responsiveness of prostate cancer, dose escalation must be weighed against the potential of increased toxicity.

Toxicity

At a median follow-up of 18 months, only preliminary observations can be made. In regards to the GU toxicity, mild-to-moderate urinary toxicity is seen in most patients after a prostate seed implant and urinary discomfort typically lasts several months.46, 47 This same pattern was observed in our cohort of patients with the majority experiencing grade 2 GU toxicity requiring alpha-blockers to help alleviate their urinary symptoms. The increase in urinary symptoms is demonstrated in Fig 1 where the AUA score peaks at 1 month after prostate brachytherapy. Our acute and late grade 3 GU toxicity is comparable to the toxicity of conventional fractionated EBRT treatment combined with a prostate seed implant boost, with studies reporting acute and late grade ≥3 GU toxicities ranging between 1.1% and 12% and 0.8% and 12%, respectively.6, 8, 13, 15, 16, 19, 20, 21 Our study had similar findings to these studies as our cohort had no acute grade 3 GU toxicity and a late grade 3 GU toxicity incidence of 4.2%.

With the use of hypofractionation, there is a concern for an increased late toxicity to the rectum, urethra, and bladder neck. This is particularly important given that the rectum is the major dose-limiting organ in the treatment of prostate cancer. As discussed previously, the α/ß ratio for the late rectal toxicity may be greater than the 1 to 3 Gy α/ß ratio associated with prostate cancer. If this is indeed the case, then hypofractionation should allow for an increased tumor effect without an associated increase in late toxicity. Our study to date shows promising results with no acute or late grade 3 GI toxicities. In addition, our toxicity profile is similar when compared with the conventional fractionated EBRT treatment and LDR brachytherapy boost, with series reporting no acute GI toxicities and late GI toxicities ranging between 0% and 3%.6, 8, 14, 15, 16, 19, 20, 21 For comparison, Valakh et al reported no acute GI toxicity and 3% incidence of late GI toxicity.6 Granted, our follow-up is still early, and as such, longer follow-up will be needed to confirm the previous findings.

PSA response and biochemical control

With a median follow-up of 18 months, the results for PSA response and biochemical control appear consistent with results seen with standard treatment. There was 1 biochemical failure associated with distant metastatic disease without local failure. In addition, studies have demonstrated that the nPSA12 (nadir PSA level achieved during the first year after completing radiation treatment) is an early predictor of biochemical failure, distant metastasis, and mortality.48, 49 In the publication by Ray et al, an nPSA12 of ≤2.0 ng/mL had an 8-year PSA-disease free survival, distant metastasis-free survival, and overall survival rate of 55%, 95%, and 73%, respectively, compared with 40%, 88%, and 69% for patients with a nPSA12 of >2.0 ng/mL.49 We found that 90% of patients with at least a year follow-up of PSA levels had a nPSA12 of ≤2.0 ng/mL.

Conclusion

The early results of our safety and toxicity protocol consisting of hypofractionated IG-IMRT with an LDR brachytherapy boost, show this combination to appear to be, in terms of short-term morbidity, both safe and effective. The rates of GI and GU toxicities are comparable to reported toxicities of conventional IG-IMRT with a LDR brachytherapy boost. In addition, the early biochemical control and PSA response is consistent with standard treatments; however, the results should be interpreted cautiously given the short-term follow-up. This shortened treatment schedule can help improve access to health care and reduce cost of therapy. Longer follow-up is needed to confirm the long-term safety and efficacy of this approach.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None.

References

- 1.National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference on the Management of Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer. Bethesda, MD, June 15-17, 1987. NCI Monogr. 1988;(7):1–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuban D.A., Tucker S.L., Dong L. Long-term results of the M. D. Anderson randomized dose-escalation trial for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peeters S.T., Heemsbergen W.D., Koper P.C. Dose-response in radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer: Results of the Dutch multicenter randomized phase III trial comparing 68 Gy of radiotherapy with 78 Gy. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1990–1996. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pollack A., Zagars G.K., Starkschall G. Prostate cancer radiation dose response: Results of the M. D. Anderson phase III randomized trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53:1097–1105. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02829-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zietman A.L., DeSilvio M.L., Slater J.D. Comparison of conventional-dose vs high-dose conformal radiation therapy in clinically localized adenocarcinoma of the prostate: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294:1233–1239. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.10.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valakh V., Kirichenko A., Miller R., Sunder T., Miller L., Fuhrer R. Combination of IG-IMRT and permanent source prostate brachytherapy in patients with organ-confined prostate cancer: GU and GI toxicity and effect on erectile function. Brachytherapy. 2011;10:195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain M., Stock R.G., Stone N.N. Brachytherapy versus brachytherapy plus external beam radiation for prostate cancer: A comparison of urinary symptoms and quality of life. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;57:S392–S393. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hurwitz M.D., Halabi S., Archer L. Combination external beam radiation and brachytherapy boost with androgen deprivation for treatment of intermediate-risk prostate cancer: Long-term results of CALGB 99809. Cancer. 2011;117:5579–5588. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarosdy M.F. Urinary and rectal complications of contemporary permanent transperineal brachytherapy for prostate carcinoma with or without external beam radiation therapy. Cancer. 2004;101:754–760. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Talcott J.A., Clark J.A., Stark P.C., Mitchell S.P. Long-term treatment related complications of brachytherapy for early prostate cancer: A survey of patients previously treated. J Urol. 2001;166:494–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang S.K., Chou R.H., Dodge R.K. Gastrointestinal toxicity of transperineal interstitial prostate brachytherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53:99–103. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)02811-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albert M., Tempany C.M., Schultz D. Late genitourinary and gastrointestinal toxicity after magnetic resonance image-guided prostate brachytherapy with or without neoadjuvant external beam radiation therapy. Cancer. 2003;98:949–954. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gelblum D.Y., Potters L., Ashley R., Waldbaum R., Wang X.H., Leibel S. Urinary morbidity following ultrasound-guided transperineal prostate seed implantation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;45:59–67. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00176-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gelblum D.Y., Potters L. Rectal complications associated with transperineal interstitial brachytherapy for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;48:119–124. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00632-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawton C.A., Yan Y., Lee W.R. Long-term results of an RTOG Phase II trial (00-19) of external-beam radiation therapy combined with permanent source brachytherapy for intermediate-risk clinically localized adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:e795–e801. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spratt D.E., Zumsteg Z.S., Ghadjar P. Comparison of high-dose (86.4 Gy) IMRT vs combined brachytherapy plus IMRT for intermediate-risk prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2014;114:360–367. doi: 10.1111/bju.12514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohler J.L., Armstrong A.J., Bahnson R.R. Prostate cancer, version 1.2016. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14:19–30. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brenner D.J., Hall E.J. Fractionation and protraction for radiotherapy of prostate carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;43:1095–1101. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00438-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghaly M., Wallner K., Merrick G. The effect of supplemental beam radiation on prostate brachytherapy-related morbidity: Morbidity outcomes from two prospective randomized multicenter trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55:1288–1293. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)04527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh A.M., Gagnon G., Collins B. Combined external beam radiotherapy and Pd-103 brachytherapy boost improves biochemical failure free survival in patients with clinically localized prostate cancer: Results of a matched pair analysis. Prostate. 2005;62:54–60. doi: 10.1002/pros.20118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zelefsky M.J., Nedelka M.A., Arican Z.L. Combined brachytherapy with external beam radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer: Reduced morbidity with an intraoperative brachytherapy planning technique and supplemental intensity-modulated radiation therapy. Brachytherapy. 2008;7:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vogelius I.R., Bentzen S.M. Meta-analysis of the alpha/beta ratio for prostate cancer in the presence of an overall time factor: Bad news, good news, or no news? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fowler J.F., Toma-Dasu I., Dasu A. Is the alpha/beta ratio for prostate tumours really low and does it vary with the level of risk at diagnosis? Anticancer Res. 2013;33:1009–1011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pollack A., Hanlon A.L., Horwitz E.M. Dosimetry and preliminary acute toxicity in the first 100 men treated for prostate cancer on a randomized hypofractionation dose escalation trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:518–526. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.07.970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ritter M. Rationale, conduct, and outcome using hypofractionated radiotherapy in prostate cancer. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2008;18:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macias V., Biete A. Hypofractionated radiotherapy for localised prostate cancer. Review of clinical trials. Clin Transl Oncol. 2009;11:437–445. doi: 10.1007/s12094-009-0382-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Junius S., Haustermans K., Bussels B. Hypofractionated intensity modulated irradiation for localized prostate cancer, results from a phase I/II feasibility study. Radiat Oncol. 2007;2:29. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-2-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kupelian P.A., Thakkar V.V., Khuntia D., Reddy C.A., Klein E.A., Mahadevan A. Hypofractionated intensity-modulated radiotherapy (70 Gy at 2.5 Gy per fraction) for localized prostate cancer: Long-term outcomes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:1463–1468. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arcangeli S., Strigari L., Gomellini S. Updated results and patterns of failure in a randomized hypofractionation trial for high-risk prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84:1172–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pollack A., Walker G., Horwitz E.M. Randomized trial of hypofractionated external-beam radiotherapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3860–3868. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee W.R., Dignam J.J., Amin M. NRG Oncology RTOG 0415: A randomized phase 3 noninferiority study comparing 2 fractionation schedules in patients with low-risk prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;94:3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buyyounouski M.K., Price R.A., Jr., Harris E.E. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for primary management of early-stage, low- to intermediate-risk prostate cancer: Report of the American Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology Emerging Technology Committee. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:1297–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.09.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freeman D.E., King C.R. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for low-risk prostate cancer: Five-year outcomes. Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:3. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-6-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang J.K., Cho C.K., Choi C.W. Image-guided stereotactic body radiation therapy for localized prostate cancer. Tumori. 2011;97:43–48. doi: 10.1177/030089161109700109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Madsen B.L., Hsi R.A., Pham H.T., Fowler J.F., Esagui L., Corman J. Stereotactic hypofractionated accurate radiotherapy of the prostate (SHARP), 33.5 Gy in five fractions for localized disease: First clinical trial results. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67:1099–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen L.N., Suy S., Uhm S. Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for clinically localized prostate cancer: The Georgetown University experience. Radiat Oncol. 2013;8:58. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-8-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Katz A.J., Santoro M., Diblasio F., Ashley R. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer: Disease control and quality of life at 6 years. Radiat Oncol. 2013;8:118. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-8-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.King C.R., Freeman D., Kaplan I. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer: Pooled analysis from a multi-institutional consortium of prospective phase II trials. Radiother Oncol. 2013;109:217–221. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tan T.J., Siva S., Foroudi F., Gill S. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for primary prostate cancer: A systematic review. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2014;58:601–611. doi: 10.1111/1754-9485.12213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roach M., 3rd, Hanks G., Thames H., Jr. Defining biochemical failure following radiotherapy with or without hormonal therapy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: Recommendations of the RTOG-ASTRO Phoenix Consensus Conference. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:965–974. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stock R.G., Stone N.N., Cesaretti J.A., Rosenstein B.S. Biologically effective dose values for prostate brachytherapy: Effects on PSA failure and posttreatment biopsy results. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:527–533. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.07.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheu R., Hua A., Svoboda A., Cesaretti J., Stock R., Lo Y. Comparison of biological effective dose between protons and seed implant plus IMRT for prostate treatment. Med Phys. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bentzen S.M., Ritter M.A. The alpha/beta ratio for prostate cancer: What is it, really? Radiother Oncol. 2005;76:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deore S.M., Shrivastava S.K., Supe S.J., Viswanathan P.S., Dinshaw K.A. Alpha/beta value and importance of dose per fraction for the late rectal and recto-sigmoid complications. Strahlenther Onkol. 1993;169:521–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stock R.G., Buckstein M., Liu J.T., Stone N.N. The relative importance of hormonal therapy and biological effective dose in optimizing prostate brachytherapy treatment outcomes. BJU Int. 2013;112:E44–E450. doi: 10.1111/bju.12166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Myers M.A., Hagan M.P., Todor D. Phase I/II trial of single-fraction high-dose-rate brachytherapy-boosted hypofractionated intensity-modulated radiation therapy for localized adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Brachytherapy. 2012;11:292–298. doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morton G. The best method for dose escalation: Prostate brachytherapy. Can Urol Assoc J. 2012;6:196–198. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.12121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alcantara P., Hanlon A., Buyyounouski M.K., Horwitz E.M., Pollack A. Prostate-specific antigen nadir within 12 months of prostate cancer radiotherapy predicts metastasis and death. Cancer. 2007;109:41–47. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ray M.E., Levy L.B., Horwitz E.M. Nadir prostate-specific antigen within 12 months after radiotherapy predicts biochemical and distant failure. Urology. 2006;68:1257–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.08.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]