Abstract

Purpose

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare and often aggressive skin cancer. Typically, surgery is the primary treatment. Postoperative radiation therapy (PORT) is often recommended to improve local control. It is unclear whether PORT is indicated in patients with favorable Stage IA head and neck (HN) MCC.

Methods and materials

We conducted a retrospective analysis of 46 low-risk HN MCC cases treated between 2006 and 2015. Inclusion criteria were defined as a primary tumor size of ≤ 2 cm, negative pathological margins, negative sentinel lymph node biopsy, and no immunosuppression. Local recurrence (LR) was defined as tumor recurrence within 2 cm of the primary surgical bed and estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method.

Results

Omission of PORT was offered to all 46 patients, of which 23 patients received PORT and 23 did not. No patient received adjuvant chemotherapy. There were no significant differences in surgical margins, tumor size, depth, lympho-vascular invasion status, or demographics between the two patient groups. Median follow-up for all patients was 3.7 years. Six of the 23 patients who did not receive PORT developed an LR. Compared to the group that received PORT, there was a significantly higher risk of LR in the group treated without PORT (26% vs. 0%, P = .02). Median time to LR was 11 months. All local failures were effectively salvaged. There was no difference in MCC-specific and overall survival between the 2 groups.

Conclusions

For patients with HN MCC, omission of PORT was associated with a significantly higher risk of local recurrence even among those patients with the lowest-risk tumors (i.e., Stage IA without immune suppression). Thus, it is important to weigh the benefits of PORT against the side effect profile on a case-specific basis for each patient.

Summary.

This is a retrospective analysis of a relatively homogenous cohort of 46 patients with low risk Stage IA Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck region. Following surgery, 23 patients received post operative radiotherapy (PORT), while 23 had surgery only. PORT was associated with a significantly lower risk of local recurrence.

Introduction

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a potentially aggressive cancer of the skin, and its incidence is increasing.1, 2 The most common location of a primary MCC is the head and neck (HN) region, and approximately 50% of patients present with Stage I disease.3 Standard of care includes a wide local excision with clear margins and a sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) for pathologic evaluation of the first echelon lymph nodes. Postoperative radiation therapy (PORT) is often added to MCC treatment to minimize local recurrences.

Several single institutional studies have reported excellent outcomes with surgery alone for patients with early stage disease.4, 5, 6 However, these studies included MCC from varied anatomical sites and are not HN-specific. The HN region has unique anatomical constraints that preclude wide resection margins and has been recognized to have an increased risk of local failure.5, 7 Despite this concern, the role of PORT for treatment of patients with favorable Stage IA HN MCC has not yet been evaluated.

The majority of studies that report on the benefit of PORT in patients with MCC are limited by small numbers and/or heterogeneous inclusion criteria.8, 9, 10 Furthermore, although nodal staging has been shown to have prognostic value,11 pathological staging with SLNB was not incorporated in most of the PORT studies, including the few published HN-specific studies.12, 13 In addition, morbidity that is related to treatment with radiation therapy (RT) is generally worse for the HN region compared with the limbs or trunk.14 Because MCC primarily occurs in the elderly population,15 providers and patients often try to avoid the morbidity of RT.16 Hence, we sought to clarify the role of PORT in patients with favorable Stage IA HN MCC.

Methods and materials

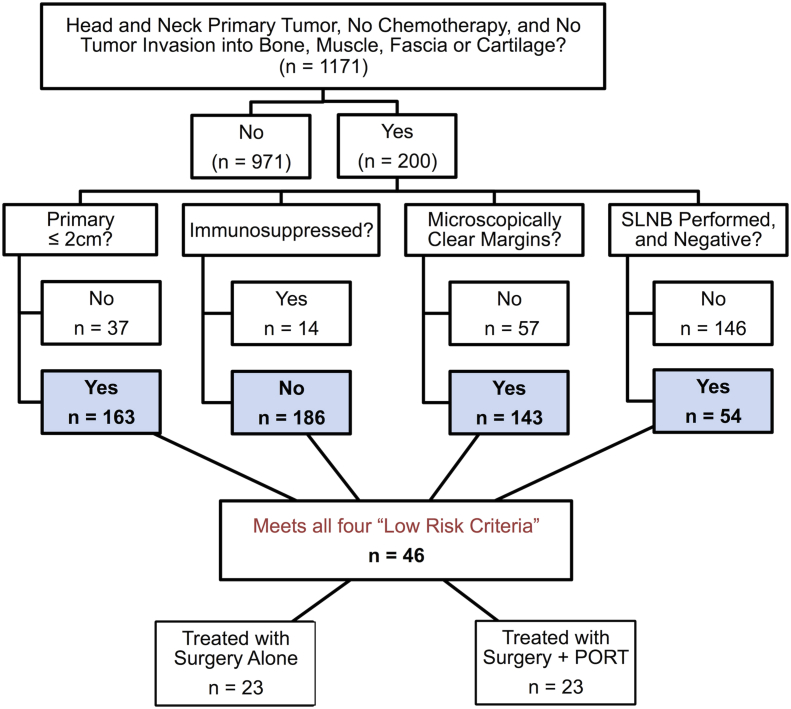

We performed an institutional review board–approved retrospective analysis of 46 patients with low-risk Stage IA HN MCC from our repository of 1171 patients who were enrolled between 2006 and 2015 (Fig 1). The Seattle repository is a longitudinal prospective database that tracks the status of participants annually through physician notes, radiologic imaging, and communication with patients. Patients who do not respond to requests for annual updates or for whom physician notes and/or other records cannot be obtained are considered lost to follow-up and censored as of the date of last communication or death.

Figure 1.

Identification of 46 patients with low-risk Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck.

Inclusion criteria

Patients were considered low risk if they met all of the following criteria: 1) a primary tumor ≤2.0 cm in diameter, 2) microscopically negative margins on the surgical excision (i.e., no ink at the margin), 3) SLNB was performed and was negative, and 4) absence of chronic immunosuppression. Patients who fulfilled all these criteria were offered a choice of surveillance versus PORT.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded from the study if 1) data were unavailable on their initial treatment or outcomes, 2) MCC treatment at initial presentation included chemotherapy, or 3) the primary tumor had invaded bone, muscle, fascia, or cartilage.

Endpoints and statistical analyses

Endpoints included local recurrence (LR), overall survival (OS), and MCC-specific death (MCCSD). For all endpoints, the date of diagnosis (biopsy) was considered time point zero. A recurrence within 2 cm of the primary tumor's surgical bed was considered a local recurrence.17 Additionally, only first events were considered for the analysis. We extracted prognostic variables that could influence local control and/or survival, such as sex, race, age, primary tumor size, anatomic subsite, lymphovascular invasion (LVI), surgical margin status, and depth of invasion (Breslow thickness). A Fisher's exact two-sided test was used to compare the patient and tumor characteristics. The nonparametric Mood's median test was used to compare median depth of invasion. Late radiation toxicity, which occurred beyond 3 months from completion of treatment, was retrospectively scored using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events Version 4.18 Significant toxicity was defined as Grade >2 in toxicity.

LR and OS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method with 95% confidence intervals and estimated with the exact binomial test. Patients were censored if they either died or were lost to follow-up. Because no LR occurred in the surgery + PORT group, log-rank statistics, hazard ratios, and multivariate analyses could not be performed for this group. The cumulative incidence of MCCSD was estimated using death from non-MCC causes as a competing risk. All analyses were performed using STATA version 11.1 (College Station, TX). A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient and tumor characteristics

Patient and tumor characteristics are summarized in Table 1. A total of 46 patients with HN primaries met all low risk criteria. There were 23 female and 23 male patients in the study. In keeping with the natural history of MCC, the patients were mostly Caucasian (91%). The median age at the time of diagnosis was 66.5 years (range, 31-85 years). There were no significant differences between patients in the surgery alone and surgery + PORT treatment groups in terms of sex, age at the time of diagnosis, primary tumor size, or anatomic location on the HN. LVI also did not vary significantly between the 2 groups (P = .20; Supplementary Table 1a). Overall, patients in the surgery + PORT group had a greater median tumor depth compared with patients in the surgery alone group, but the difference was not significant (5.00 mm vs 2.90 mm, P = .65; Supplementary Figure 1).

Table 1.

Patient and tumor characteristics at presentation of patients with low-risk Stage IA HN MCC

| Characteristic | % Within Group∗ |

P† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery % (n = 23) | Surgery + PORT % (n = 23) | ||

| Sex | |||

| Male (n = 23) | 60.9 (14) | 39.1 (9) | 0.24 |

| Female (n = 23) | 39.1 (9) | 60.9 (14) | |

| Race | |||

| White (n = 42) | 91.3 (21) | 91.3 (21) | — |

| Data Unavailable (n = 4) | 8.7 (2) | 8.7 (2) | |

| Age at Diagnosis | |||

| > 65 years (n = 25) | 56.5 (13) | 52.2 (12) | 1.00 |

| ≤ 65 years (n = 21) | 43.5 (10) | 47.8 (11) | |

| Primary Tumor Size | |||

| 0-1 cm (n = 39) | 91.3 (21) | 78.3 (18) | 0.41 |

| > 1 cm (n = 7) | 8.7 (2) | 21.7 (5) | |

| Subsite of Primary Tumor | |||

| Cheek (n = 20) | 30.4 (7) | 56.5 (13) | 0.52 |

| Forehead (n = 7) | 21.7 (5) | 8.7 (2) | |

| Nose (n = 4) | 8.7 (2) | 8.7 (2) | |

| Ear (n = 4) | 13.0 (3) | 4.3 (1) | |

| Eyelid (n = 3) | 4.3 (1) | 8.7 (2) | |

| Neck (n = 2) | 4.3 (1) | 4.3 (1) | |

| Lip (n = 2) | 8.7 (2) | 0.0 (0) | |

| Scalp (n = 2) | 4.3 (1) | 4.3 (1) | |

| Chin (n = 1) | 0.0 (0) | 4.3 (1) | |

| Data Unavailable (n = 1) | 4.3 (1) | 0.0 (0) | |

HN MCC, Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck; PORT, postoperative radiation therapy.

Rounding applied.

P values per Fisher's exact test.

The median follow-up was 3.7 years for the entire population (range, 8.4 months to 13.4 years) with a median follow-up of 3.6 years and 5.3 years for the surgery alone and surgery + PORT groups, respectively.

Treatment characteristics

Twenty-three patients with a low-risk diagnosis were treated with PORT, and 23 patients did not receive PORT (n = 23 in both groups). Twelve of 23 patients who had surgery alone and 6 of 23 patients who had surgery + PORT were treated at our institution. None of the patients received adjuvant chemotherapy.

Surgery alone

The median tumor size was 0.8 cm (range, 0.3-1.8 cm). Nineteen of 23 patients (82.6%) had a wide excision. The intended surgical margin was ≥ 1 cm in 17 patients. Two patients underwent Mohs surgery. In the 2 patients with an unknown intended margin width, there was no residual tumor on final excision per the pathology report (Tables 2). Two patients had an unknown microscopic margin width; however, the margin status per final pathology report was confirmed as negative (Table 3).

Table 2.

Intended surgical margins∗

| No. of Patients |

||

|---|---|---|

| Surgery | Surgery + PORT | |

| ≤0.5 cm | 0 | 2 |

| 1 cm | 14 | 8 |

| 1.5 cm | 1 | 1 |

| ≥2 cm | 2 | 4 |

| Wide excision, not further specified | 2 | 6 |

| Not Applicable† | 2 | 1 |

| Unknown | 2 | 1 |

| Total | 23 | 23 |

PORT, postoperative radiation therapy.

Intended surgical margins = margins per operative report.

P = .32, P values per Fisher's exact test.

Table 3.

Microscopic margins per final pathology

| No. of Patients |

||

|---|---|---|

| Surgery | Surgery + PORT | |

| <0.1 cm | 1 | 0 |

| 0.1-0.4 cm | 6 | 4 |

| 0.5-0.99 cm | 1 | 0 |

| ≥1 cm | 2 | 2 |

| No residual tumor detected | 9 | 14 |

| Not applicable† | 2 | 1 |

| Unknown | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 23 | 23 |

PORT, postoperative radiation therapy.

Mohs surgery.

Surgery and PORT

The median tumor size was 0.8 cm (range, 0.1-2 cm). Twenty-one of 23 patients (91%) had a wide excision. An intended surgical margin of ≥ 1 cm was achieved in 13 patients (Tables 2). One patient underwent Mohs surgery. There was no residual tumor on the final excision in the only patient with an unknown intended margin width. For 2 patients with unknown microscopic margin width, the margin status was confirmed as negative by the final pathology report. There was no significant difference between the patients who were treated with and without PORT with regard to the intended surgical margins and the microscopic margins (P = .32 and P = .77, respectively).

PORT details

The use of PORT was primarily driven by patient preference. The primary tumor surgical bed with a minimum margin of 3 cm to 5 cm was irradiated to a median dose of 50 Gy (range, 16.2-66 Gy) using electrons and/or photons. Six patients (26.1%) also received PORT to the regional lymph node basin. No patient who received PORT experienced significant late toxicity.

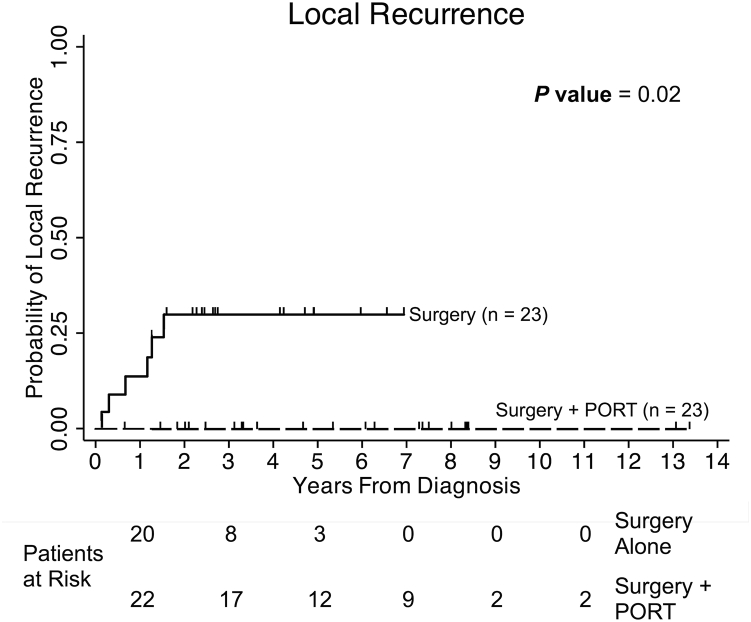

Recurrence and survival

Patients who did not receive PORT had a significantly greater risk of developing an LR (5-year LR 26.3% vs. 0%, P = .02; Fig 2). LR occurred in patients with primary tumor sites on the cheek (3), forehead (2), and ear (1). An LR was observed in 5 of 6 patients who initially had a wide excision with a surgical margin of at least 1 cm, and the remaining patient underwent Mohs surgery. By pathology, 2 patients had a margin width between 1 mm and 4 mm, 3 patients had no residual tumor detected after the final excision, and 1 patient underwent Mohs surgery. A subset analysis that excluded the 4 patients with unknown margin width (Table 3) showed that the addition of PORT significantly improved local control (Supplementary Table 2, n = 42, P = .021). Although the exact margin width was unknown for these 4 patients, the margin status per the final pathology report was confirmed as negative.

Figure 2.

Probability of local recurrence is illustrated for 46 patients who were treated with surgery with or without PORT. Six patients recurred locally in the surgery-alone group, and none recurred locally among the patients treated with surgery + PORT group. The Kaplan-Meier 5-year estimate for local recurrence was 26.3% in the group of patients who were treated with surgery alone. There was a significant difference in local recurrence between patients who did and did not receive postoperative radiation therapy (P = .02).

Among the patients who developed an LR, the primary tumor measured 5 mm or smaller in 5 patients and 8 mm in 1 patient. All 6 patients with LR had known LVI status (Supplementary Table 1b). Five of 6 patients (83%) had LVI absent, and 1 patient had LVI present. LVI status did not significantly affect LR status (P = .65). Similarly, the Breslow thickness status also appeared to be worse in tumors that were treated with PORT (Supplementary Figure 1). The median time to LR was 11 months.

All 6 patients who experienced an LR were salvaged with radiotherapy. One patient also underwent surgery in addition to RT. Chemotherapy was not administered for LR. Salvage treatment was successful in achieving an ultimate local control of 100% in all cases. Among the patients with LR, 1 died as a result of MCC and 1 died of non-MCC causes. The patient who died due to MCC experienced both regional and distant failure after LR (Table 4).

Table 4.

Patient characteristics and associated outcomes of patients with low-risk Stage IA MCC who experienced any type of recurrence

| Pt | Age at Dx | Sex | Primary Subsite | Primary Size (cm) | Tumor Depth of Primary Tumor (mm) | LVI? | Initial Treatment | LR | Non-LR∗ | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1¦ | 84 | M | Cheek | 0.4 | 0.80 | Absent | Surgery | Yes | Yes†,‡ | Dead§ |

| 2 | 76 | M | Forehead | 0.5 | 1.05 | Absent | Surgery | Yes | No | Dead |

| 3 | 59 | F | Forehead | 0.5 | 2.10 | Absent | Surgery | Yes | No | Alive |

| 4 | 58 | M | Cheek | 0.5 | 4.00 | Absent | Surgery | Yes | No | Alive |

| 5 | 80 | M | Ear | 0.8 | Unknown | Present | Surgery | Yes | No | Alive |

| 6 | 67 | M | Cheek | 0.5 | Unknown | Absent | Surgery | Yes | No | Alive |

| 7¶ | 71 | F | Lip | 0.8 | 1.00 | Absent | Surgery | No | Yes† | Alive |

| 8# | 57 | F | Cheek | 0.7 | Unknown | Unknown | Surgery | No | Yes† | Alive |

| 9 | 82 | M | Ear | 0.1 | Unknown | Unknown | Surgery + PORT | No | Yes‡ | Dead§ |

| 10 | 73 | M | Forehead | 1 | 1.40 | Absent | Surgery + PORT | No | Yes‡ | Alive |

| 11 | 49 | M | Cheek | 1 | Unknown | Absent | Surgery + PORT | No | Yes† | Alive |

DM, distant metastatic; Dx, diagnosis; F, female; LVI, lymphovascular invasion; LR, local recurrence; M, male; MCC, Merkel cell carcinoma; PORT, postoperative radiation therapy; Pt, patient; RR, regional recurrence.

Non-local recurrence is defined as lymph node RR† or DM recurrence‡.

Death due to MCC.

First recurrence was local. The RR and DM occurred at 244 and 260 days from the LR, respectively.

RR occurred in neck level I, 3.45 years after diagnosis.

RR was discovered during first week of PORT.

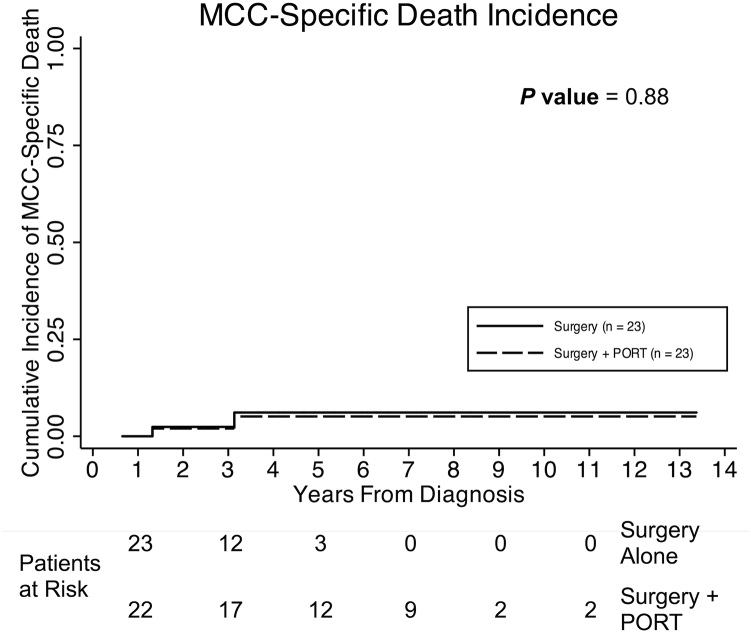

Five other patients developed a nonlocal recurrence. Three of these patients experienced a regional recurrence (RR) and 2 developed a distant metastasis as a first event. None of these patients developed a subsequent LR. RR was noted in 1 patient who was treated with surgery alone and 1 patient who underwent surgery and received PORT. One patient developed an RR that was discovered during the first week of PORT. There were no deaths among the patients who had an RR. The 2 patients who experienced a distant metastasis were initially treated with surgery and PORT, and 1 died as a result of MCC. There was no difference between the groups treated with and without PORT in terms of MCCSD (P = .88; Fig 3) or OS (P = 1.00; Supplementary Figure 2).

Figure 3.

Cumulative incidence of Merkel cell carcinoma-specific death (MCCSD) is illustrated for 46 patients with low-risk disease. Death as a result of non-MCC causes was used as a competing risk. One patient in each group died as a result of MCC. There was no significant difference in MCCSD between patients who did and did not receive postoperative radiation therapy (P = .88).

Three patients were lost to follow-up, including 2 in the PORT group (at 5 years and 6 years) and 1 in the surgery-without-PORT group (2 years after initial diagnosis). There were no LRs among these patients during the time they were followed.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to describe the risk of LR and the role of PORT in a homogenous cohort of patients with low-risk Stage IA HN MCC. Despite favorable features that include nonimmunosuppressed patients, primary tumor ≤2 cm, clear surgical margins, and negative SLNB, LR was 26% among patients who were treated with surgery alone. In comparison, there were no LRs in the patients who were treated with surgery and PORT.

Although it is clear that patients with high-risk MCC warrant treatment with PORT,19, 20 it has been debated whether PORT is required for low-risk patients.21 Most studies that showed a benefit with PORT included patients with higher-risk disease. In one of the largest studies of HN MCC, Bishop et al reported a local/regional control rate of 96% among 106 patients who were treated with either surgery + PORT or definitive RT (without a resection).12 Only 9 patients had Stage IA disease, and the study did not have a comparable cohort of patients who did not receive PORT. Strom et al reported on 113 patients with Stage I through Stage III HN MCC and found that PORT significantly improved local control (89.4% vs 68.1%, P = .005).22 Similarly, Lok et al described 48 patients with HN MCC, 12 of whom had Stage I disease.21 There were no recurrences within the radiation fields. Their study included 18 patients with Stage III and 17 patients with recurrent disease. Although they did not recommend PORT for patients with Stage IA MCC, it is difficult to draw a meaningful conclusion about the role of PORT in patients with Stage IA disease from this study.

Additionally, most studies included patients who did not have an SLNB evaluation.9, 12, 13, 23, 24, 25 The importance of SLNB in improving prognostic value and identifying a group of patients with low-risk MCC has been demonstrated. 11, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 Hence, the value of PORT in the setting of a negative SLNB has been questioned. In addition, most studies did not consider host immunosuppression, which is another important negative prognostic factor.31 In summary, there is no comparable data in the literature that has quantified the role of PORT in reducing the risk of LR for such a favorable low-risk group of patients.

In general, previous studies have not recommended PORT for patients with low-risk MCC.6, 21, 32 Fields et al reported excellent outcomes with surgery alone and selective use of RT for 364 patients with Stage I through Stage III MCC of all sites. The LR rate for patients with Stage IA MCC was 0%. Of 95 patients with Stage IA MCC, 13 (14%) received PORT. The criteria for PORT included high-risk features such as larger tumors, lymphovascular invasion, and positive surgical margins. Hence, this cohort differs from that in our study. In addition, the number of patients who had Stage IA HN cancer was not specified.6 Boyer et al reported on 45 patients with Stage I MCC who were treated with Mohs surgery.32 There was no significant difference in the LR among patients who underwent surgery compared with patients who were treated with surgery + PORT. Frohm et al reported only one true LR and 4 in-transit recurrences in a cohort of 105 patients with MCC who were treated without PORT to the primary site. Sixty-nine patients (65.7%) were diagnosed with Stage IA, and 44 (41.9%) had a primary HN tumor.33 However, a limitation of prior studies of patients with low-risk MCC is that they do not separately report on HN cases. Bajetta et al reported on 95 patients with early stage MCC that was managed with surgery alone. The 5-year LR rate in patients with HN MCC was 19%, versus 2% in MCC of the limbs and trunk (P = .007).5

It is important to consider patients with HN MCC separately because the anatomical, cosmetic, and functional challenges unique to this location could preclude wide surgical margins. In addition, the complex lymphatic drainage patterns in the HN could increase the risk of local/regional relapses after surgery alone.5, 34, 35, 36 Given these concerns, we hypothesized that even patients with low-risk Stage IA HN MCC may be at a greater risk of developing an LR if they are treated with surgery alone.

We found that PORT was associated with a significantly lower risk of LR (26% vs. 0%) within this low-risk population. However, all LRs were salvaged without any incidents of uncontrolled local disease. In addition, there was no difference in MCC-specific or overall survival between the 2 groups. Hence, a policy of offering surveillance versus PORT for this cohort of patients with low-risk disease did not compromise patient safety despite the greater number of LRs in the surgery-only arm. However, a recurrence is stressful and burdensome to many patients. In addition, the need for a stringent follow-up program for patients who opt for surveillance cannot be overemphasized. It should also be noted that most LRs (5 of 6) were managed at major academic centers. Successful salvage of an LR requires a timely and coordinated effort. This may not always be possible in centers with fewer resources and less expertise in the treatment of MCC.

The toxicity of PORT may be a concern for some. In this series, there was no recorded significant long-term toxicity. Similarly, Lok et al reported no significant late toxicity, and only 10% of patients had acute toxicity (temporary dermatitis).21 Bishop et al reported that 5 of 106 patients had significant late toxicity: 4 patients with ocular and 1 patient mandibular.12 All 5 of these patients received RT dose >56 Gy.

The present study analyzed a homogenous cohort of patients with low-risk Stage IA HN MCC in a relatively rare disease. None of the patients received chemotherapy, which is a treatment-related confounder. Furthermore, treatment was performed across multiple centers; hence, the results are more likely to be generalizable. Although the radiation treatment parameters may appear heterogeneous, this is due to the unique anatomic considerations of treating tumors in the HN region. For example, per National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, a 5-cm margin around the primary tumor surgical bed is attempted in all cases. However, for tumors that occur near the eyelids, the margin may be reduced to avoid unnecessary irradiation to the eye. Similarly, most patients did not receive elective nodal irradiation. About 26% did, and these were cases in which the first echelon draining lymph nodes were in close proximity to the primary tumor site. Incidental irradiation was thus delivered to the draining nodal region in the process of adding a 5-cm margin to the primary surgical bed. The relationship of tumors arising near the lateral cheek with the preauricular lymph nodes highlights this principle. In addition, this relative heterogeneity in the radiotherapy parameters did not appear to be detrimental as none of the patients in the PORT group developed a local failure. Finally, the median follow-up of 3.7 years is an adequate time interval for the detection of most recurrences in this disease.

With this retrospective study, there could be inherent hidden and uncontrollable biases. Our sample size of 46 patients was relatively small, in accordance with the rarity of MCC. Further research is needed to better identify patients who have a greater risk of LR in this apparently low-risk group, which is possibly based on immunological and/or other molecular characteristics. In addition, MCC is a relatively radiosensitive cancer. After a median PORT dose of 50 Gy, there were no in-field relapses in this study. Other studies12, 21 also reported excellent disease control within the radiation fields. It would be interesting to prospectively study the utility of a lower dose of RT (eg, 8 Gy) delivered in a single fraction. This approach was effective in the control of metastatic MCC.37 A single fraction would be more convenient to patients compared with 5 to 6 weeks of treatment with PORT. Given the paucity of regional relapses in this cohort, it is possible that PORT fields that encompass only the primary surgical bed with a 3 to 5 cm margin (without elective nodal treatment) may be adequate for the majority of patients with Stage IA who are nonimmunosuppressed. These approaches could further reduce the risk of RT-related morbidity.

Conclusions

In this cohort, low-risk nonimmunosuppressed patients with Stage IA HN MCC had a 26% probability of LR if treated with surgery alone. The use of PORT was associated with a significantly lower risk of LRs in these patients. Although the local failures were effectively salvaged, the potential harm from a recurrence and the relatively favorable toxicity profile of PORT argue for its consideration even in patients with low-risk Stage IA HN MCC.

Footnotes

Sources of support: This work was supported by a Gift Fund (65-1064).

Conflicts of interest: None.

Supplementary material related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adro.2016.10.003.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Bichakjian C.K., Lowe L., Lao C.D. Merkel cell carcinoma: Critical review with guidelines for multidisciplinary management. Cancer. 2007;110:1–12. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hodgson N.C. Merkel cell carcinoma: Changing incidence trends. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:1–4. doi: 10.1002/jso.20167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasan S., Liu L., Triplet J., Li Z., Mansur D. The role of postoperative radiation and chemoradiation in merkel cell carcinoma: A systematic review of the literature. Front Oncol. 2013;3:276. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen P.J., Bowne W.B., Jaques D.P., Brennan M.F., Busam K., Coit D.G. Merkel cell carcinoma: Prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2300–2309. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bajetta E., Celio L., Platania M. Single-institution series of early-stage Merkel cell carcinoma: Long-term outcomes in 95 patients managed with surgery alone. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2985–2993. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0615-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fields R.C., Busam K.J., Chou J.F. Recurrence after complete resection and selective use of adjuvant therapy for stage I through III Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2012;118:3311–3320. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Connor W.J., Brodland D.G. Merkel cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:262–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1996.tb00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medina-Franco H., Urist M.M., Fiveash J., Heslin M.J., Bland K.I., Beenken S.W. Multimodality treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: case series and literature review of 1024 cases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:204–208. doi: 10.1007/s10434-001-0204-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veness M.J., Perera L., McCourt J. Merkel cell carcinoma: Improved outcome with adjuvant radiotherapy. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75:275–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2005.03353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gillenwater A.M., Hessel A.C., Morrison W.H. Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck: Effect of surgical excision and radiation on recurrence and survival. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:149–154. doi: 10.1001/archotol.127.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lemos B.D., Storer B.E., Iyer J.G. Pathologic nodal evaluation improves prognostic accuracy in Merkel cell carcinoma: Analysis of 5823 cases as the basis of the first consensus staging system. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:751–761. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.02.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bishop A.J., Garden A.S., Gunn G.B. Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck: Favorable outcomes with radiotherapy. Head Neck. 2016;38(suppl1):E452–E458. doi: 10.1002/hed.24017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark J.R., Veness M.J., Gilbert R., O'Brien C.J., Gullane P.J. Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck: is adjuvant radiotherapy necessary? Head Neck. 2007;29:249–257. doi: 10.1002/hed.20510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holliday E.B., Frank S.J. Proton radiation therapy for head and neck cancer: a review of the clinical experience to date. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;89:292–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albores-Saavedra J., Batich K., Chable-Montero F., Sagy N., Schwartz A.M., Henson D.E. Merkel cell carcinoma demographics, morphology, and survival based on 3870 cases: A population based study. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:20–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2009.01370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tarantola T.I., Vallow L.A., Halyard M.Y. Prognostic factors in Merkel cell carcinoma: analysis of 240 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:425–432. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edge S.B., American Joint Committee on Cancer, American Cancer Society . 7th ed. xix. Springer; New York: 2010. p. 718. (Melanoma of the skin. AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook: From the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual). [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.0. NCI, NIH, DHHS. May 29, 2009. NIH publication #09-7473.

- 19.Meeuwissen J.A., Bourne R.G., Kearsley J.H. The importance of postoperative radiation therapy in the treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31:325–331. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)E0145-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morrison W.H., Peters L.J., Silva E.G., Wendt C.D., Ang K.K., Goepfert H. The essential role of radiation therapy in securing locoregional control of Merkel cell carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1990;19:583–591. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(90)90484-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lok B., Khan S., Mutter R. Selective radiotherapy for the treatment of head and neck Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2012;118:3937–3944. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strom T, Naghavi AO, Messina JL, et al. Improved local and regional control with radiotherapy for Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck [e-pub ahead of print]. Head Neckhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1002/hed.24527, accessed September 8, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Boyle F., Pendlebury S., Bell D. Further insights into the natural history and management of primary cutaneous neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31:315–323. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(93)E0110-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jabbour J., Cumming R., Scolyer R.A., Hruby G., Thompson J.F., Lee S. Merkel cell carcinoma: Assessing the effect of wide local excision, lymph node dissection, and radiotherapy on recurrence and survival in early-stage disease–results from a review of 82 consecutive cases diagnosed between 1992 and 2004. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1943–1952. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9327-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mojica P., Smith D., Ellenhorn J.D. Adjuvant radiation therapy is associated with improved survival in Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1043–1047. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grotz T.E., Joseph R.W., Pockaj B.A. Negative sentinel lymph node biopsy in Merkel cell carcinoma is associated with a low risk of same-nodal-basin recurrences. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:4060–4066. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4421-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gupta S.G., Wang L.C., Penas P.F., Gellenthin M., Lee S.J., Nghiem P. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for evaluation and treatment of patients with Merkel cell carcinoma: The Dana-Farber experience and meta-analysis of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:685–690. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.6.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fields R.C., Busam K.J., Chou J.F. Recurrence and survival in patients undergoing sentinel lymph node biopsy for merkel cell carcinoma: Analysis of 153 patients from a single institution. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:2529–2537. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1662-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maza S., Trefzer U., Hofmann M. Impact of sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with Merkel cell carcinoma: Results of a prospective study and review of the literature. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2006;33:433–440. doi: 10.1007/s00259-005-0014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kachare S.D., Wong J.H., Vohra N.A., Zervos E.E., Fitzgerald T.L. Sentinel lymph node biopsy is associated with improved survival in Merkel cell carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:1624–1630. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paulson K.G., Iyer J.G., Blom A. Systemic immune suppression predicts diminished Merkel cell carcinoma-specific survival independent of stage. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:642–646. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boyer J.D., Zitelli J.A., Brodland D.G., D'Angelo G. Local control of primary Merkel cell carcinoma: Review of 45 cases treated with Mohs micrographic surgery with and without adjuvant radiation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:885–892. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.125083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frohm M.L., Griffith K.A., Harms K.L. Recurrence and survival in patients with Merkel cell carcinoma undergoing surgery without adjuvant radiation therapy to the primary site. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1001–1007. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morand G.B., Madana J., Da Silva S.D., Hier M.P., Mlynarek A.M., Black M.J. Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck: Poorer prognosis than non-head and neck sites. J Laryngol Otol. 2016;130:393–397. doi: 10.1017/S0022215116000153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin D., Franc B.L., Kashani-Sabet M., Singer M.I. Lymphatic drainage patterns of head and neck cutaneous melanoma observed on lymphoscintigraphy and sentinel lymph node biopsy. Head Neck. 2006;28:249–255. doi: 10.1002/hed.20328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Bree R., Nieweg O.E. The history of sentinel node biopsy in head and neck cancer: From visualization of lymphatic vessels to sentinel nodes. Oral Oncol. 2015;51:819–823. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iyer J.G., Parvathaneni U., Gooley T. Single-fraction radiation therapy in patients with metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2015;4:1161–1170. doi: 10.1002/cam4.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.