Abstract

Our study examined factors influencing the effectiveness of a parent-based HIV prevention intervention implemented in Cape Town, South Africa. Caregiver-youth dyads (N = 99) were randomized into intervention or control conditions and assessed longitudinally. The intervention improved a parenting skill associated with youth sexual risk, parent–child communication about sex and HIV. Analyses revealed that over time, intervention participants (female caregivers) who experienced recent intimate partner violence (IPV) or unsafe neighborhoods discussed fewer sex topics with their adolescent children than caregivers in safer neighborhoods or who did not report IPV. Participants with low or moderate decision-making power in their intimate relationships discussed more topics over time only if they received the intervention. The effectiveness of our intervention was challenged by female caregivers’ experience with IPV and unsafe neighborhoods, highlighting the importance of safety-related contextual factors when implementing behavioral interventions for women and young people in high-risk environments. Moderation effects did not occur for youth-reported communication outcomes. Implications for cross-cultural adaptations of parent-based HIV prevention interventions are discussed.

Keywords: HIV, violence, parenting, neighborhood, South Africa

Despite recent incidence stabilization, HIV continues to be a major concern in South Africa (Shisana et al., 2009). In 2010, approximately 5.24 million people or 10.5% of the population were living with the virus (Statistic South Africa, 2011). Across gender and age, black South Africans bear the largest burden of the illness (Rehle et al., 2007). Prevalence is alarmingly high among youth, particularly young women (Shisana et al., 2009).

Recent HIV prevention efforts have targeted young people via parent- or family-based interventions. Although those implemented in the region show promise in reducing risk (e.g., Bell et al., 2008), less attention is paid to contextual factors which may undermine their effectiveness—namely, issues related to safety and gender dynamics. The current study therefore examines three potential moderators of the effectiveness of a parent-based HIV prevention intervention (Imbadu Ekhaya) conducted in Cape Town. We know female caregivers receiving this intervention increased the number of sex-related topics they discussed with their youth, postintervention, compared with controls (Armistead et al., 2014). Discussions between caregivers and their children about sex and sexual risks is a strong family predictor of behavioral HIV risk reduction for youth and is the primary focus of our intervention and current study. We now consider the role of three safety-related moderators to intervention effectiveness: caregivers’ degree of sexual decision-making power in their intimate relationships, experience with past-year intimate partner violence (IPV), and perceptions of neighborhood safety. Results will inform the development and delivery of future parent-based HIV prevention interventions and will shed light on social and family dynamics in one South African community.

Families are an appropriate target for youth HIV prevention (Donenberg, Paikoff, & Pequegnat, 2006). Parent–child communication about sex is often a primary target of intervention. Different aspects of this type of communication are important for youth risk reduction, including repetition of discussions (Martino, Elliott, Corona, Kanouse, & Schuster, 2008), number of topics discussed (Dutra, Miller, & Forehand, 1999; Hutchinson, Jemmott, Jemmott, Braverman, & Fong, 2003; Kapungu et al., 2010; Martino et al., 2008) and depth of conversations (Hutchinson & Montgomery, 2007). For example, Kapungu et al. (2010) found a negative association between number of sexual risk topics discussed by teens and their mothers and the likelihood of youth reporting having unprotected sex in the past 90 days. Family-based interventions are growing in number, and developers have become attuned to families’ ethnic and cultural differences (e.g., Lescano, Brown, Raffaelli, & Lima, 2009). To our knowledge, only three such interventions have been empirically tested in South Africa: the current intervention, CHAMP-SA (Bell et al., 2008), and Let’s Talk! (Bogart et al., 2013).

Despite the emphasis on a program’s cultural relevancy, research conducted in the U.S. or South Africa typically has not examined whether and how contextual influences moderate outcomes. Interventions may be most effective for families with health or family problems (e.g., maternal depression; Gardner, Hutchings, Bywater, & Whitaker, 2010), probably because these families have greater needs for intervention and more room for growth. However, meta-analytic reviews of parent training programs identify economic disadvantage as a barrier to intervention effectiveness (Lundahl, Risser, & Lovejoy, 2006). Inadequate financial resources and concomitant unsafe living conditions produce tremendous caregiver stress. These immediate needs can easily override the need to learn and practice new parenting skills.

We considered two theories when hypothesizing how contextual influences may hinder Imbadu Ekhaya. First, the theory of gender and power (Connell, 1987) posits that social and structural factors—such as gender-based violence—create power imbalances between men and women. These imbalances underlie women’s increased vulnerability to HIV infection (Wingood & DiClemente, 2000). Consistent with the theory, South African women who have experienced intimate partner violence (IPV) and have low power in their relationships also have high rates of HIV seropositivity (Dunkle et al., 2004). Indeed, issues of gender-based violence and other forms of gender inequality were repeatedly raised during our formative work in the region, and empirical studies support the concern; for example, 66% of black South African adolescent girls report having been forced to have sex (Jewkes, Vundule, Maforah, & Jordaan, 2001). Further, women from communities in which these reports are generated indicate a significant degree of exposure to neighborhood stressors, including witnessing or experiencing traumatic events (Dinan, McCall, & Gibson, 2004). Living in a neighborhood with conditions like these also increases one’s risk for HIV infection (Kalichman et al., 2006), presumably more so for women given the structural inequalities that exist across gender.

The same influences that put women at risk for HIV are likely to put their children at risk either directly or through disruptions in family functioning. When the theory of gender and power is extended to a parent-based intervention, an ecological theory like the model of family stress (Conger et al., 2002) is useful in explaining how contextual stressors experienced by South African caregivers can affect parenting and reduce the impact of our intervention. For example, when caregivers live in a neighborhood they perceived as unsafe, they can experience psychological distress, which in turn negatively affects parenting (Kotchick, Dorsey, & Heller, 2005). Similarly, IPV constrains a healthy family life, and children of mothers who are abused have high rates of internalizing and externalizing problems (McFarlane, Groff, O’Brien, & Watson, 2003). Exposure to environments characterized by a high incidence of violence and gender oppression also instills in South African boys and girls culturally specific, victim-blaming beliefs (e.g., patriarchal notions of masculinity; Petersen, Bhana, & McKay, 2005), a factor which likely complicates how they talk to their mothers about sensitive topics like sex. We assume that South African caregivers with these stressors face challenges in parenting, and specifically with respect to protecting their children from HIV.

In addition to stress, insecurity—including victimization, having low relationship power, and living in violent neighborhoods—can also lead to a perceived lack of control for women. Evidence-based interventions like ours aimed at improving parenting are typically driven by theoretical mechanisms that assume caregivers have some control over their own lives, control that can be strengthened through participation in the intervention. For example, the current adaptation drew in part from the Parents Matter! Program (PMP). PMP integrated several established models of behavioral change, including social learning theory, problem behavior theory, theory of reasoned action, and social–cognitive theory (Dittus, Miller, Kotchick, & Forehand, 2004). Caregivers are trained with the knowledge and skills believed to enhance their self-efficacy, in part, to communicate with their children about risk topics. However, caregivers exposed to unsafe environments, including violence at home and in the community, who feel powerless in their relationships, and who subsequently lack control and security in their lives, may be limited by how much they can benefit from the intervention.

As formative work indicated that these factors were prevalent in caregivers’ lives, to the extent possible, we tried to mitigate their influence via an adaptation process (Armistead et al., 2014). For example, we incorporated caregiver training components on the influence of gender roles in shaping caregiver-youth discussions about sex, addressed how caregivers’ experiences with sexual trauma can be a barrier to talking about sex, and elicited conversations about the ways in which urbanization and poverty affect parenting and youth sexual risk.

Current Study

To date, research into moderators of parent-based interventions has been conducted primarily in Western settings but not in South Africa. Furthermore, no studies have dealt with a specific and sensitive component of parenting such as caregiver-youth communication about sex, a topic that may have direct emotional relevance to female caregivers who have experienced sexual violence. To extend the literature and improve future interventions, we evaluate our intervention in the following ways. We ask, did our parent-based HIV prevention intervention improve breadth of caregiver–youth communication about sex equally for female caregivers who (a) have or have not experienced recent IPV, (b) perceive their neighborhoods to be relatively safe or unsafe, and lastly (c) have high or low decision-making power in their intimate relationships? Results will indicate the extent to which the intervention was effective for participants based on each potential moderator.

Method

Design and Procedure

Imbadu Ekhaya is a parent-based HIV prevention intervention which consisted of six 2.5 hr-long sessions conducted in either Xhosa or English with groups of female caregivers and their adolescent children (child included in Session 6 only). U.S. and South African researchers collaborated with partners at community-based agencies, as well as parents and youth from the target community, to adapt, implement, and evaluate the intervention. IRB approval was obtained through both universities. Trained project staff, two women fluent in both Xhosa and English, conducted baseline and follow-up assessments at sites within the Langa community, a predominantly black Cape Town township. At baseline assessments, informed consent was obtained from caregivers and assent from children in English or Xhosa based on participants’ preference. Measures were administered, also in English or Xhosa, through audio computer-assisted self-interview technology (ACASI) to increase participants’ privacy and comfort. Caregivers were compensated with a grocery store voucher worth 70 Rand (approximately $10 USD) for each assessment. Participants were randomized to either the intervention or a waitlist control group. Waitlist participants did not receive information about the intervention other than what was included in the consent process and were offered to receive the intervention at the end of the study. Outcomes were measured at postintervention (within 1 month of the final intervention session) and at 6-month follow-up. Data were collected from 2010 to 2011.

The intervention was implemented at community sites in Langa and co-led by two female facilitators employed by the Cape Town Child Welfare Society (CTCWS) with previous experience in implementing parenting interventions. Fluent in Xhosa and English, facilitators were trained over a 5-day period by U.S. and South African researchers to administer the intervention in both languages. A review of intervention content, modeling, and role-plays were used in the training. A supervisor at CTWCS provided weekly supervision. A fidelity analysis showed the intervention was delivered as intended 89% of the time, and participants rated the facilitators as highly prepared and the sessions as rarely counterproductive (Armistead et al., 2014). This likely contributed to good retention, as results from our main outcome study demonstrated that participants on average attended most sessions (M = 4.50 sessions; SD = 1.90).

Intervention content consisted of information about child development and general parenting practices (i.e., parent–child relationship quality, parental monitoring, and parental involvement), adolescent sexual behavior and parent–child communication about sex, and specific contextual topics such as gender norms/roles, HIV and trauma in families, and transactional sex. The manualized intervention was delivered through didactic presentations, small group discussions, homework, role-play, modeling, and practicing of skills. See Armistead et al. (2014) for more information about intervention content and delivery.

Participants

Baseline data were collected from a sample of N = 99 Black South African female caregivers (M age = 42.7 years, SD = 12.0) living in Langa. Langa is the oldest black community in Cape Town, with a population of approximately 50,000 people and is home to both government-established housing and an informal settlement of shacks known as “Joe Slovo.” Caregivers included biological mothers of the youth (70%), grandmothers (16%), aunts (6%), and great-grandmothers (2%), with one cousin and one foster mother. Approximately half of the youth (53%) were female. Ethnic identifications of the caregiver-youth dyads included Xhosa (84%), Zulu (11%), Sotho (3%), and other (2%). Approximately 78% of caregivers were born in the Western Cape, whereas 21.4% were born in the Eastern Cape. One participant was born outside of South Africa. Approximately 42% of caregivers had never married. Roughly 60% of caregivers and 30% of youth completed the assessment in Xhosa, and the rest chose English.

Of the 99 assessed, 57 were randomized to the intervention group and 42 to the control group. Using an intent-to-treat approach, all participants were contacted to complete follow-up assessments. Rate of postintervention follow-up was 89% (N = 88) and 85% at 6-month follow-up (N = 84). The most common reason for attrition was participants were unable to be contacted by project staff. Results of two logistic regressions predicting participation at each follow-up revealed that attrition was not dependent upon any variable included in our analysis.

South African staff went door-to-door to recruit eligible caregiver-youth dyads from Langa. Eligible caregivers had to live in Langa for at least 1 year and have a child in the household between the ages of 10- to 14-years-old with whom they spent most nights of each week. Caregivers included biological parents and other adults who were legally responsible for and provided primary care and supervision of the youth. If more than one child in the household was eligible, the child with the birthday closest to the informational meeting used for recruitment was selected to participate. During the informational session project staff reviewed details about the study and scheduled baseline assessment appointments. Of the 106 who attended an informational session, four were ineligible and three withdrew after consent, citing the length of the baseline assessment as problematic. Only female caregivers were recruited, as women are typically the primary caregivers of South African youth, and formative work revealed a desire among participants to have single gender groups.

Measures

To ensure cultural relevancy and sensitivity, we selected instruments that had been previously used with South African samples where possible. When established South African instruments were not available, U.S.-based measures were modified based on our cultural and ethnic knowledge of similar South African communities. South African-based researchers and staff reviewed each measure line by line and gave feedback that was incorporated into modified versions. Each measure was translated from English to Xhosa and back-translated into English.

Family resources

The Household Economic and Social Status Index (HESSI), developed in South Africa (Barbarin & Khomo, 1997), consisted of 17 items about material welfare (e.g., housing quality, food security) as an indicator of socioeconomic status. Thirteen of the 17 items required a yes (1) or no (0) response. The remaining items had ordinal response sets (e.g., “In what type of house do you and your child live”; scored 0–5). A scale score was creating by summing across all 17 items (potential range = 0 to 28). When necessary, items were reverse scored so that higher scores indicated higher family resources. The scale was dichotomized at the median, creating a low and high material resources group.

Perceived neighborhood safety

Caregivers’ perceptions of neighborhood safety were measured with a 9-item scale. Of the nine items, three were based on an index of community disorder (Cutrona, Russell, Hessling, Brown, & Murry, 2000): “children in your neighborhood have nowhere to play but the street,” “the equipment and buildings in the park or open area that is closest to where you live are well kept,” and “there are gangs in my neighborhood.” The remaining six items were created for this study based on our knowledge of Langa. These concerned the street committee and neighborhood watch organizations in respondents’ communities as well as respondents’ general perceptions of the safety of open areas during the day and at night. All items except for one were measured on a true/false scale. One item (“How safe do you feel your neighborhood is?”) was measured on a 3-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = not safe to 3 = very safe. We dichotomized this item by combining very safe with the midpoint (safe) in order to include it in the scale. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.71.

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV)

We measured recent IPV using six items drawn from the WHO Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence: Core Questionnaire (García Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise, & Watts, 2005). We assessed the breadth and prevalence (for past year and lifetime) of physical and sexual violence by any intimate partner. Sample items included, has a partner ever in the past year, “slapped you or thrown something at you that could hurt you,” or “physically forced you to have sexual intercourse when you did not want to?” For purposes of the current analyses, we focused on past year physical or sexual IPV and created a dichotomous variable (0 = no recent IPV; 1 = recent IPV).

Decision-making power

We measured relationship decision-making power using an 8-item subscale of the Sexual Relationship Power Scale (Pulerwitz, Gortmaker, & DeJong, 2000), previously used with a different sample of black South Africans (Ketchen, Armistead, & Cook, 2009). Only participants who were currently sexually involved with someone responded to questions on this measure; two participants did not respond, and thus analyses that included decision-making power as a variable were limited in sample size. Items had a three-category response-set to indicate which partner holds the power in the relationship. For the purposes of the current analyses, “your partner” was coded as 1, “both of you equally” as 2, and “you” as 3. Sample items include “Who usually has more say about when you talk about serious things,” and “Who usually has more say about whether you use condoms?” A mean response was created with a range of 1 to 3 for each participant, with a lower mean indicative of low decision-making power and a higher mean indicative of high decision-making power. Alpha equaled .78.

Caregiver-youth communication about topics related to sex

We measured caregiver-youth communication about sex topics by asking caregivers 18 items drawn from a previously used scale (Miller, Kotchick, Dorsey, Forehand, & Ham, 1998) related to communication about various topics related to sex, sexual development, and sexual risk factors, such as dating or going out with a boy/girl, puberty, menstruation, what sex is, HIV/AIDS, abstinence, STIs, rape, condoms, drug/alcohol use, and transactional sex. We treated caregiver–youth communication about sex topics as a count variable. Counts could range from 0 to 18, with higher scores indicating that caregiver and child talked about more sex topics. Communication was measured similarly among youth. However, because of South African IRB concerns, youth who did not answer “yes” to talking to their caregivers about sex at Time Points 1 and 2 were only given eight of the 18 total items. This drastically reduced sample size (e.g., 48% of youth participants responded to all 18 items at T1). To maximize sample size and increase consistency across assessments, only the eight items answered by all child participants at all time points were used for the analysis. These eight items asked whether caregivers talked to youth about alcohol and drug use, what sex is, dating, puberty, menstruation, HIV, and gender roles. Caregivers and youth were asked to report on number of topics discussed ever (T1), since the start of the intervention (T2), and since the end of the intervention (T3).

Data Analysis

A moderation analysis approach was taken using procedures developed for use in SPSS (Hayes & Matthes, 2009) through a series of hierarchical linear regressions. Moderating variables were neighborhood safety, IPV, and decision-making power measured at baseline, the independent variable was condition (i.e., intervention vs. control), and the outcome was caregiver–youth communication about sex (i.e., number of topics discussed) reported by either caregiver or youth. First, to determine baseline differences in communication (T1) by condition and by moderator, communication, in six separate regressions (one for each of the three moderators and both caregiver and youth report of communication), was regressed on condition, a given moderator, and a Moderator 3 Condition interaction term.

To address the primary study aims, three separate regressions were conducted, each including one moderator and its Moderator × Condition interaction term predicting our postintervention follow-up outcome of caregiver report of communication (T2), controlling for baseline communication. Three additional regressions, one for each moderator and Moderator × Condition interaction term, predicting caregiver report of communication at 6-month follow-up (T3), were then conducted, controlling for baseline levels of communication. Finally, all models were repeated using youth report of communication as the outcome. In all regressions, child gender and age were controlled for because research has demonstrated their association with parent–child communication about sex (Poulsen et al., 2010). Models also adjusted for family resources as socioeconomic status affects parent-based interventions (see Reyno & McGrath, 2006 for a meta-analysis). In Step 1, hierarchical analyses for every regression included baseline communication (except for baseline analyses), condition, one moderator, and demographic covariates. Step 2 added the Moderator × Condition interaction term. Effects on follow-up levels of communication are interpreted as residualized change scores.

We probed significant interaction terms that explained a significant amount of additional variance in postintervention and 6-month follow-up communication for conditional effects. In these analyses, a conditional effect was the effect of the intervention at levels of a given moderator. Moderators were probed at one standard deviation (SD) above, below and at the mean level of the moderator corresponding to high, low, and medium levels of the moderator, for decision-making power and neighborhood safety, and with IPV, for those participants who experienced IPV versus those who did not at baseline. Conditional effects showed whether levels of communication changed significantly over time depending on the level of the moderator.

Results

Descriptives and Bivariate Correlations

Descriptives and bivariate correlations are found in Table 1. Caregivers of older youth were less likely to report IPV and were more likely to report higher levels of baseline communication than caregivers of younger youth. Female youth indicated more communication at all time points relative to male youth. There were no significant associations between demographic variables and between predictor variables. Of the predictor variables, only neighborhood safety was associated with an outcome; it was positively associated with communication at T2. Participation in the intervention was not associated with any demographic or predictor variables at baseline, suggesting equivalency of groups. As expected from our prior study of intervention effect sizes (Armistead et al., 2014), participation in the intervention was positively and significantly associated with caregiver report of communication at T2 and T3. It was not, however, associated with youth report of communication. Communication at each time point reported by caregivers was intercorrelated, as was communication reported by youth. Communication reported at T1 by either informant did not correlate to communication at follow-up time points reported by the other. At T2 and T3, cross-informant correlations of communication were significant and positive.

Table 1.

Descriptives and Correlations Among Demographic, Predictor, and Outcome Variables

| Variable | n (% yes) or M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||||||||||||

| 1. Child age | 11.71 (1.39) | ||||||||||||

| 2. Female child | 52 (53%) | .08 | |||||||||||

| 3. Family resourcesa | 46 (47%) | .10 | .16 | ||||||||||

| Predictor | |||||||||||||

| 4. Intervention | 57 (58%) | .00 | .12 | .06 | |||||||||

| 5. Intimate partner violence (IPV) | 34 (34%) | −.22 | .05 | −.03 | .02 | ||||||||

| 6. Neighborhood safety | 5.09 (2.32) | .17 | −.07 | .08 | .16 | −.12 | |||||||

| 7. Decision-making power | 1.91 (.41) | −.03 | −.15 | .08 | .10 | .04 | .13 | ||||||

| 8. T1 communication (youth) | 4.67 (2.44) | .16 | .36 | .17 | −.07 | .04 | −.12 | −.19 | |||||

| 9. T1 communication (caregiver) | 8.17 (5.21) | .23 | .12 | .07 | −.04 | −.11 | .08 | −.12 | .18 | ||||

| Outcome | |||||||||||||

| 10. T2 communication (youth) | 5.75 (2.58) | .07 | .32 | .19 | .16 | .19 | −.01 | .05 | .48 | .08 | |||

| 11. T2 communication (caregiver) | 11.20 (5.23) | .15 | .01 | −.12 | .39 | −.09 | .22 | .07 | −.02 | .52 | .25 | ||

| 12. T3 communication (youth) | 5.36 (2.76) | .02 | .45 | .21 | −.01 | .16 | −.19 | −.08 | .54 | .08 | .68 | .16 | |

| 13. T3 communication (caregiver) | 11.58 (5.40) | .19 | −.04 | −.06 | .23 | −.18 | .09 | −.01 | .12 | .57 | .29 | .79 | .23 |

Note. Significant interactions (p < .05) are bolded. N = 99, 88, and 84 for T1, T2, and T3, respectively, for correlations with IPV and safety. N = 97, 86, and 82 for corresponding time points for correlations with decision-making power.

Percent with high family resources.

Item responses for the outcome variable are found in Table 2. As expected, intervention participants generally reported discussing topics at higher rates than control participants at later time points. Many participants reported talking to their youth about rape and sexual abuse, even more so than some topics related to sexual development. The high prevalence of sexual violence in their neighborhoods may compel caregivers to talk to their youth about such topics.

Table 2.

Percent of Caregivers and Youth Who Discussed a Sex or Sexual Risk Topic

| Topic | T1 | T2 | T3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | |

| Caregiver/youth report | ||||||

| Alcohol use | 77/60 | 71/60 | 88/84 | 70/70 | 94/78 | 85/75 |

| Drug use | 67/54 | 71/62 | 86/77 | 70/70 | 82/80 | 82/72 |

| Dating | 42/47 | 41/67 | 82/73 | 54/62 | 73/51 | 70/69 |

| Puberty | 33/75 | 41/64 | 82/82 | 54/70 | 69/71 | 52/75 |

| Menstruation | 42/58 | 52/67 | 58/77 | 54/70 | 59/61 | 61/67 |

| What sex is | 33/47 | 33/45 | 88/75 | 43/67 | 73/63 | 52/56 |

| Gender roles | 26/51 | 12/57 | 55/59 | 11/49 | 61/61 | 27/50 |

| HIV/AIDS | 74/60 | 71/64 | 88/84 | 65/67 | 77/74 | 70/69 |

| Caregiver onlya | ||||||

| STIs | 28 | 17 | 49 | 35 | 63 | 39 |

| Sexual reproduction | 18 | 29 | 47 | 35 | 49 | 36 |

| Abstinence | 40 | 50 | 71 | 49 | 71 | 67 |

| Peer pressure to have sex | 44 | 55 | 84 | 54 | 73 | 64 |

| Condoms | 44 | 52 | 82 | 51 | 78 | 55 |

| Birth control | 33 | 29 | 53 | 38 | 63 | 42 |

| Rape and sexual assault | 70 | 69 | 75 | 65 | 80 | 70 |

| Child sexual abuse | 67 | 71 | 86 | 67 | 80 | 73 |

| Sexual consent | 18 | 19 | 43 | 27 | 43 | 12 |

| Media messages about sex | 42 | 51 | 75 | 41 | 73 | 49 |

Due to IRB concerns at T1, youth were not asked about these topics.

Moderation Analysis With Caregiver Report of Communication

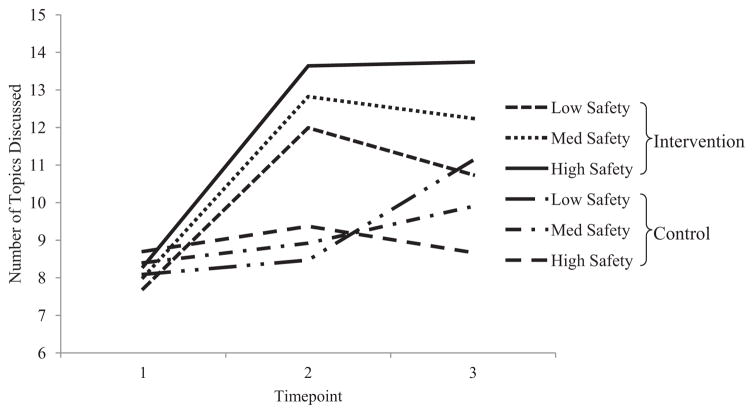

Our three initial regressions predicting baseline communication yielded no significant main or interaction effects (see Table 3), thus as expected due to randomization, no significant differences between communication in the intervention arm versus control arm were found at baseline. These results also suggest that neighborhood safety, IPV, and decision-making power were not differentially associated with communication at baseline by study arm. When included in the multivariate model, youth age was no longer associated with baseline communication. Figures 1, 2, and 3 show the predictive values of communication by level of the moderator at baseline (T1) based on the conditional slope of baseline communication regressed on condition (intervention vs. control) at levels of each moderator.

Table 3.

Results of Linear Regressions Predicting Communication About Sex (Caregiver Report)

| T1 | T2 | T3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| B | 95% CI | B | 95% CI | B | 95% CI | |

| Intimate partner violence (IPV) | ||||||

| Baseline communication | 0.52*** | [0.36, 0.69] | 0.58 | [−3.21, 14.20] | ||

| Youth age | 0.77 | [−0.00, 1.54] | 0.10 | [−0.55, 0.75] | −0.01 | [−0.75, 0.73] |

| Female | 1.01 | [−1.15, 3.17] | 0.43 | [−1.37, 2.22] | −0.05 | [−1.99, 1.89] |

| Family resources | 0.33 | [−1.80, 2.47] | −1.49 | [−3.24, 0.26] | −0.72 | [−2.64, 1.21] |

| Intervention | −0.25 | [−2.89, 2.38] | 5.02** | [2.90, 7.14] | 3.94** | [1.52, 6.35] |

| IPV | −0.80 | [−4.16, 2.74] | 1.34 | [−1.58, 4.26] | 1.47 | [−1.80, 4.75] |

| Intervention * IPV | −0.08 | [−4.61, 4.45] | −2.93 | [−6.70, 0.84] | −4.27* | [−8.40, 30.14] |

| Model R2 | .06 | .46** | .43** | |||

| ΔR2 due to interaction | .00 | .02 | .03* | |||

| Neighborhood safety (Safety) | ||||||

| Baseline communication | 0.52** | [0.35, 0.68] | 0.58*** | [0.39, 0.76] | ||

| Youth age | 0.79* | [0.02, 1.55] | 0.08 | [−0.56, 0.73] | 0.09 | [−0.63, 0.81] |

| Female | 1.00 | [−1.13, 3.13] | 0.29 | [−1.49, 2.07] | −0.17 | [−2.09, 1.75] |

| Family resources | 0.30 | [−1.87, 2.48] | −1.49 | [−3.28, .31] | −1.28 | [−3.27, 0.71] |

| Intervention | −0.38 | [−5.62, 4.86] | 3.08 | [−1.16, 7.31] | −3.44 | [−8.08, 1.19] |

| Safety | 0.13 | [−0.49, 0.75] | 0.19 | [−0.31, .69] | −0.53 | [−1.08, 0.03] |

| Intervention * Safety | 0.00 | [−0.94, 0.94] | 0.16 | [−0.60, .93] | 1.17** | [0.31, 2.02] |

| Model R2 | .07 | .46** | .44** | |||

| ΔR2 due to interaction | .00 | .00 | .06** | |||

| Decision-making power (DM) | ||||||

| Baseline communication | 0.54** | [0.38, 0.70] | 0.59** | [0.40, 0.79] | ||

| Youth age | 0.87* | [0.10, 1.64] | −0.03 | [−0.67, 0.61] | 0.00 | [−0.76, 0.77] |

| Female | 0.87 | [−1.32, 3.05] | 0.12 | [−1.65, 1.89] | −0.74 | [−2.76, 1.28] |

| Family resources | 0.63 | [−1.53, 2.79] | −1.01 | [−2.74, 0.73] | −0.15 | [−2.16, 1.87] |

| Intervention | 1.13 | [−9.60, 11.86] | 14.62** | [6.18, 23.08] | 11.07* | [1.30, 20.84] |

| DM | −0.95 | [−5.22, 3.33] | 5.18** | [1.78, 8.58] | 3.27 | [−0.59, 7.14] |

| Intervention * DM | −0.63 | [−6.18, 4.92] | −5.57* | [−9.91, −1.24] | −4.62+ | [−9.63, 0.40] |

| Model R2 | .09 | .51** | .41** | |||

| ΔR2 due to interaction | .00 | .04* | .03* | |||

Note. Regression coefficients are unstandardized. N = 99, 88, and 84 for T1, T 2, and T3, respectively, for IPV and safety. N = 97, 86, and 82 for corresponding time points for DM.

p = .07.

p = .05.

p = .01.

Figure 1.

Moderation of the intervention by decision-making (DM) power.

Figure 2.

Moderation of the intervention by neighborhood safety.

Figure 3.

Moderation of the intervention by intimate partner violence (IPV).

The first step of the remaining regressions predicting communication at T2 and T3 to examine moderator effects yielded significant main effects for the intervention (p < .05) prior to the addition of an interaction term. That is, consistent with previous analyses (i.e., Armistead et al., 2014), the intervention significantly increased caregiver report of communication at T2 and T3 for participants in the intervention group compared to the control group.

Our second set of regressions predicting caregiver report of postintervention (T2) levels of communication produced one significant intervention × moderator interaction, the model including decision-making power (see Table 2). Data points for T2 in Figure 1 display predicted values of communication based conditional effects of communication on intervention at levels of decision-making power. Results indicated no significant differences between predicted levels of communication for intervention versus control participants with high decision-making power (2.34). Participants with low (1.50) and medium levels (1.92) of decision-making power in the intervention had significantly higher levels of predicted communication than those with similar levels of decision-making power in the control condition (ps < .001).

Our third set of regressions predicting caregiver report of 6-month follow-up (T3) levels of communication produced two significant Intervention × Moderator interactions and one which trended toward significance (i.e., decision-making power as moderator; p = .07; Table 2). Data points for T3 in Figure 2 are the predicted values of the conditional effect of communication on intervention at levels of neighborhood safety. Results indicated no significant differences between predicted levels of communication for intervention versus control participants living in neighborhoods with low safety. Participants in the intervention with medium (4.96) and high levels (7.31) of neighborhood safety had significantly higher predicted levels of communication than those with similar levels of neighborhood safety in the control condition (ps < .05). Data points for T3 in Figure 3 are the predicted values of the conditional effect of communication on intervention for those who have and have not experienced past year IPV. Results indicated no significant differences between predicted levels of communication for intervention versus control participants who have experienced IPV. For those who have not experienced IPV, intervention participants had higher predicted values of communication than control participants (p < .01).

In summary, at T2, only decision-making power moderated the intervention. Intervention participants had the highest levels of predicted communication regardless of decision-making power, whereas control participants with high decision-making power also seemed to have similar levels of communication as intervention participants. Those control group participants with low and medium levels of decision-making power had lower levels of communication than their intervention group counterparts. This suggests that without the intervention, it is possible that participants with low and medium (particularly low) decision-making power would not have improved on the communication outcome. It also suggests that even without the intervention, participants with high decision-making power might talk about more topics related to sex with only the prompts provided through the baseline assessment. By 6-month follow-up, intervention participants with high and medium levels of neighborhood safety and those who did not experience IPV had higher levels of predicted communication than participants with low levels of neighborhood safety and those who did experience IPV.

Moderation Analysis With Youth Reported Communication

Initial baseline regressions predicting communication revealed a significant interaction when safety was used as a moderator and not when decision-making power and IPV were used as moderators. This suggests that at baseline, youth report of communication was not equally distributed between conditions by level of caregiver report of safety. Further regressions predicting communication at T2 and T3 yielded no significant main effects of the intervention, nor interaction effects (not tabled); thus, conditional effects were not probed. The effect of the intervention on levels of youth-reported communication was not therefore dependent upon caregivers’ reports of IPV, decision-making power, or neighborhood safety.

Discussion

Implemented in Cape Town, our intervention was developed in response to the alarmingly high rates of HIV infection among young black South Africans. Like similar interventions in the region, it was effective. However, the current study demonstrates how some participants benefited more than others. In a setting where gender and violence intersect to create oppressive, dangerous conditions for women, the strength of our intervention was challenged by female caregivers’ experience with recent IPV and unsafe neighborhoods. For these caregivers, caregiver–youth communication about sex did not maintain its increase in breadth postintervention by 6-month follow-up, as it did for caregivers who have not experienced recent IPV or who lived in what they perceived to be relatively safe neighborhoods.

Regardless of level of neighborhood safety, caregivers receiving the intervention reported a greater amount of communication at T2 than those in the control. However, these gains in communication were lost by 6-month follow-up when caregivers indicated living in unsafe neighborhoods. There are three possible explanations for this finding. First, caregivers may be constrained in their ability to retain the skills and self-efficacy gained from the intervention when stressful community environments deplete coping resources. Second, because parenting style is often shaped by perceptions of neighborhood quality, particularly for caregivers residing in the most dangerous environments, the decision to discontinue discussions related to sex with their child may be protective. In the U.S., Mexican American parents living in high-crime, low-income neighborhoods have been found to use more restrictive and control-oriented parenting styles to keep their children safe (Cruz-Santiago & Ramírez-Garca, 2011). For caregivers who believe talking to their child about sex implies permission to have sex (a common concern), not discussing additional topics related to sex is a form of parental control, an adaptive response to their dangerous living environment. Third, caregivers living in unsafe neighborhoods may prioritize talking to their children about more pressing safety-related concerns once initial conversations about sex take place. Future interventions should acknowledge and respond to caregivers’ legitimate fears related to unsafe neighborhoods.

One in three caregivers in our study reported being physically or sexually abused by their partner in the past year, compared with 14% of U.S. women (Schafer, Caetano, & Clark, 1998). Caregivers’ concern around IPV is reflected in the relatively high percentage who report talking to their children about rape and sexual assault. Qualitative studies of caregivers in the region suggest that a history of structural violence experienced by black South Africans is related indirectly to adolescent problem behavior (Ramphele, 1999). Specifically, men raised in violent circumstances may turn violent toward women, who in turn feel disempowered and ineffective in their role as a caregiver, which increases children’s behavioral risks. In addition, stigma associated with being victimized can lead to silence among South African women (Fox et al., 2007), and ongoing communication about sex with their children may trigger memories of violence and thus be traumatizing. Family-based interventions will benefit from creating a safe place for women to talk about sexual violence. Strategies that promote social capital are shown to be effective in reducing IPV and HIV risk among South Africans (Pronyk et al., 2006).

Gender dynamics played a role in determining our intervention’s outcome of communication. The absence of fathers in many South African families due in part to the legacy of apartheid, including forced migration, has given rise to households headed by women (Lee, 2009). In contrast, gender norms in South Africa dictate that men typically retain decision-making power with their intimate partners. Research from South Africa (Pettifor, Macphail, Anderson, & Maman, 2012), suggests attitudes toward gender norms are changing. Over time, we found that participants with high, compared with low or medium, decision-making power talked about more topics related to sex with their children regardless of receiving the intervention. The confidence and control these women feel in their relationships may drive their ability to talk to their children about sensitive topics like sex. Conversely, without this confidence, it appears this ability is constrained; indeed, we found a decline in the number of topics discussed between caregiver and youth at follow-up for caregivers with low decision-making power who did not receive the intervention. If decision-making power is absent in one domain of life, it might be absent in others. Improvements in our main communication outcome were found for women with low decision-making power who received the intervention.

Despite following a careful adaptation process of an evidence-based intervention, the long-term effectiveness of our intervention was limited for some participants. The strong support for this type of HIV prevention effort in the U.S. (see Sutton, Lasswell, Lanier, & Miller, 2014 for a review) should be reconsidered in light of our findings—a comprehensive analysis of moderation effects that goes beyond the influence of demographic characteristics may yield differential outcomes for certain groups of participants. A basic approach to combat contextual barriers could be the addition of “booster sessions,” a common technique that typically involves the addition of one or more extra sessions several months following the intervention that consist of reinforcing skill acquisition. Instead of targeting all participants, those known to be experiencing IPV, for example, could be given specific IPV prevention strategies at a booster session. Adaptations in high-risk communities or for high-risk families could also require more aggressive ways of intervening. In South Africa, group-based, time-limited behavioral interventions should be one of many approaches to prevent HIV. Multilevel strategies that involve institutions and entire communities, in addition to the family and individual, are arguably the most effective (Coates, Richter, & Caceres, 2008). Further, norms theorized to underlie women’s HIV risk in South Africa (e.g., hegemonic masculinity; Jewkes & Morrell, 2010) should be evaluated in terms of their impact on parenting and children’s HIV risk.

It is worth noting that similar moderation effects were not seen for youth-reported communication. Due to gating of items, youth reported on only eight communication topics, which could have limited how much change could occur from baseline to follow-up assessments for youth, relative to caregivers. Related to this claim, caregivers were assessed regarding a broad range of topics, and youth did not report on the particular topics that were more sensitive (e.g., transactional sex), and therefore perhaps more susceptible to moderator effects considered here. It is also possible that communication outcomes were influenced by the intervention only when reported by caregivers because caregivers were the informants of the moderators.

Limitations are noted. Measures underwent a careful selection and modification process in order to maximize their cultural sensitivity; nonetheless, perhaps they did not capture the complete experience of caregivers. In addition, the current study only examined one outcome, caregiver–youth communication about sex topics. How other outcomes, such as parent–child relationship quality and child behavior, are influenced by moderators, remains to be tested. Further, though number of sex-related topics discussed is an important predictor of youth behavioral HIV risk (Hutchinson et al., 2003; Kapungu et al., 2010), other aspects of sex communication (e.g., depth and frequency of discussions) should be explored as moderated outcomes. In addition, this study was conducted with black, primarily Xhosa-identified South Africans; outcomes may differ for other ethnic and linguistic groups. Also, our outcome was assessed only up until six months postintervention. Communication and the influence of the moderators on communication could change over a longer time period. Moreover, longitudinal analyses had a relatively small sample size for detecting interaction effects. Smaller but significant differences may have been detected if sample size was increased. Finally, the nonequivalence of groups is observed. If groups were more equivalent (e.g., using an attentional control), group differences may have been smaller and therefore less likely to result in significant intervention effects, and perhaps moderation effects as well. For example, control participants who did experience IPV may have reported a number of topics discussed similar to intervention participants with no IPV.

Movement toward an increasingly ecological approach to HIV prevention in South Africa demands a priori and post hoc analyses of the influence of relevant contextual factors on the efficacy of behavioral interventions. Gender and relationship dynamics, neighborhood and social contexts, and exposure to violence of all forms deserve attention when adapting evidence-based interventions to new settings. Our study demonstrated empirically the effect of some of these influences. Researchers should next examine the influence of other known contextual stressors. For instance, many South African families are affected by maternal HIV infection (Palin et al., 2009) and feel the continued effects of racial segregation and discrimination postapartheid (Williams et al., 2008). Furthermore, we need new and innovative ways of addressing these concerns through time-limited behavioral interventions, while retaining intervention fidelity.

Contributor Information

Nicholas Tarantino, Georgia State University.

Nada Goodrum, Georgia State University.

Lisa P. Armistead, Georgia State University

Sarah L. Cook, Georgia State University

Donald Skinner, Stellenbosch University.

Yoesrie Toefy, Stellenbosch University.

References

- Armistead L, Cook S, Skinner D, Toefy Y, Anthony ER, Zimmerman L, Chow L. Preliminary results from a family-based HIV prevention intervention for South African youth. Health Psychology. 2014;33:668–676. doi: 10.1037/hea0000067. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/hea0000067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbarin OA, Khomo N. Indicators of economic status and social capital in South African townships: What do they reveal about the material and social conditions in families of poor children? Childhood: A Global Journal of Child Research. 1997;4:193–222. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0907568297004002005. [Google Scholar]

- Bell CC, Bhana A, Petersen I, McKay MM, Gibbons R, Bannon W, Amatya A. Building protective factors to offset sexually risky behaviors among black youths: A randomized control trial. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2008;100:936–944. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31408-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart LM, Skinner D, Thurston IB, Toefy Y, Klein DJ, Hu CH, Schuster MA. Let’s talk! A South African worksite-based HIV prevention parenting program. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;53:602–608. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.01.014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates TJ, Richter L, Caceres C. Behavioural strategies to reduce HIV transmission: How to make them work better. Lancet. 2008;372:669–684. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60886-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60886-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun Y, Simons RL, Mcloyd VC, Brody GH. Economic pressure in African American Families: A replication and extension of the Family Stress Model. 2002;38:179–193. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037//0012-1649.38.2.179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW. Gender and power: Society, the person and sexual politics. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Santiago M, Ramírez García JI. “Hay que ponerse en los zapatos del joven”: Adaptive parenting of adolescent children among Mexican-American parents residing in a dangerous neighborhood. Family Process. 2011;50:92–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01348.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Russell DW, Hessling RM, Brown PA, Murry V. Direct and moderating effects of community context on the psychological well-being of African American women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:1088–1101. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.6.1088. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.6.1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinan BA, McCall GJ, Gibson D. Community violence and PTSD in selected South African townships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19:727–742. doi: 10.1177/0886260504263869. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0886260504263869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittus P, Miller KS, Kotchick BA, Forehand R. Why parents matter!: The conceptual basis for a community-based HIV prevention program for the parents of African American youth. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2004;13:5–20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:JCFS.0000010487.46007.08. [Google Scholar]

- Donenberg GR, Paikoff R, Pequegnat W. Introduction to the special section on families, youth, and HIV: Family-based intervention studies. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2006;31:869–873. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj102. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsj102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Brown HC, Gray GE, McIntryre JA, Harlow SD. Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of HIV infection in women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. Lancet. 2004;363:1415–1421. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16098-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutra R, Miller KS, Forehand R. The process and content of sexual communication with adolescents in two-parent families: Associations with sexual risk-taking behavior. AIDS and Behavior. 1999;3:59–66. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1025419519668. [Google Scholar]

- Fox AM, Jackson SS, Hansen NB, Gasa N, Crewe M, Sikkema KJ. In their own voices: A qualitative study of women’s risk for intimate partner violence and HIV in South Africa. Violence Against Women. 2007;13:583–602. doi: 10.1177/1077801207299209. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077801207299209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García Moreno C, Jansen HAFM, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts C. WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women: Initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women’s responses. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner F, Hutchings J, Bywater T, Whitaker C. Who benefits and how does it work? Moderators and mediators of outcome in an effectiveness trial of a parenting intervention. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39:568–580. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2010.486315. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2010.486315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, Matthes J. Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behavior Research Methods. 2009;41:924–936. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.3.924. http://dx.doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.3.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson MK, Jemmott JB, III, Jemmott LS, Braverman P, Fong GT. The role of mother-daughter sexual risk communication in reducing sexual risk behaviors among urban adolescent females: A prospective study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33:98–107. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00183-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson MK, Montgomery AJ. Parent communication and sexual risk among African Americans. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2007;29:691–707. doi: 10.1177/0193945906297374. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0193945906297374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Morrell R. Gender and sexuality: Emerging perspectives from the heterosexual epidemic in South Africa and implications for HIV risk and prevention. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2010;13:6. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-13-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Vundule C, Maforah F, Jordaan E. Relationship dynamics and teenage pregnancy in South Africa. Social Science & Medicine. 2001;52:733–744. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00177-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kagee A, Toefy Y, Jooste S, Cain D, Cherry C. Associations of poverty, substance use, and HIV transmission risk behaviors in three South African communities. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62:1641–1649. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.021. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapungu CT, Baptiste D, Holmbeck G, McBride C, Robinson-Brown M, Sturdivant A, Paikoff R. Beyond the “birds and the bees”: Gender differences in sex-related communication among urban African-American adolescents. Family Process. 2010;49:251–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01321.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketchen B, Armistead L, Cook S. HIV infection, stressful life events, and intimate relationship power: The moderating role of community resources for black South African women. Women & Health. 2009;49:197–214. doi: 10.1080/03630240902963648. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03630240902963648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotchick BA, Dorsey S, Heller L. Predictors of parenting Among African American single mothers: Personal and contextual factors. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:448–460. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-2445.2005.00127.x. [Google Scholar]

- Lee R. African women and apartheid: Migration and settlement in urban South Africa. London, UK: Academic Studies; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lescano CM, Brown LK, Raffaelli M, Lima LA. Cultural factors and family-based HIV prevention intervention for Latino youth. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009;34:1041–1052. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn146. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsn146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl B, Risser HJ, Lovejoy MC. A meta-analysis of parent training: Moderators and follow-up effects. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26:86–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino SC, Elliott MN, Corona R, Kanouse DE, Schuster MA. Beyond the “big talk”: The roles of breadth and repetition in parent-adolescent communication about sexual topics. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e612–e618. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2156. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane JM, Groff JY, O’Brien JA, Watson K. Behaviors of children who are exposed and not exposed to intimate partner violence: An analysis of 330 black, white, and Hispanic children. Pediatrics. 2003;112:e202–e207. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.3.e202. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.112.3.e202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KS, Kotchick BA, Dorsey S, Forehand R, Ham AY. Family communication about sex: What are parents saying and are their adolescents listening? Family Planning Perspectives. 1998;30:218–222. 235. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2991607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palin FL, Armistead L, Clayton A, Ketchen B, Lindner G, Kokot-Louw P, Pauw A. Disclosure of maternal HIV-infection in South Africa: Description and relationship to child functioning. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13:1241–1252. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9447-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10461-008-9447-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen I, Bhana A, McKay M. Sexual violence and youth in South Africa: The need for community-based prevention interventions. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:1233–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.02.012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettifor A, Macphail C, Anderson AD, Maman S. “If I buy the Kellogg’s then he should [buy] the milk:” Young women’s perspectives on relationship dynamics, gender power and HIV risk in Johannesburg, South Africa. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2012;14:477–490. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.667575. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2012.667575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen MN, Miller KS, Lin C, Fasula A, Vandenhoudt H, Wyckoff SC, Forehand R. Factors associated with parent-child communication about HIV/AIDS in the United States and Kenya: A cross-cultural comparison. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14:1083–1094. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9612-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10461-009-9612-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronyk PM, Hargreaves JR, Kim JC, Morison LA, Phetla G, Watts C, Porter JD. Effect of a structural intervention for the prevention of intimate-partner violence and HIV in rural South Africa: A cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2006;368:1973–1983. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69744-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69744-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulerwitz J, Gortmaker SL, DeJong W. Measuring sexual relationship power in HIV/STD research. Sex Roles. 2000;42:637–660. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1007051506972. [Google Scholar]

- Ramphele M. Across boundaries: The journey of a South African woman leader. New York, NY: Feminist Press at the City University of New York; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rehle T, Shisana O, Pillay V, Zuma K, Puren A, Parker W. National HIV incidence measures—New insights into the South African epidemic. South African Medical Journal. 2007;97:194–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyno SM, McGrath PJ. Predictors of parent training efficacy for child externalizing behavior problems–a meta-analytic review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:99–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01544.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J, Caetano R, Clark CL. Rates of intimate partner violence in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:1702–1704. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.11.1702. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.88.11.1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC, Zuma K, Jooste S, Pillay-van-Wyk V the SABSSM III Implementation Team. South African national HIV prevalence, incidence, behaviour and communication survey 2008: A turning tide among teenagers? Cape Town, Africa: HSRC Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Statistic South Africa. Mid-year population estimates 2010. Pretoria, Africa: Statistics South Africa; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton MY, Lasswell SM, Lanier Y, Miller KS. Impact of parent-child communication interventions on sex behaviors and cognitive outcomes for black/African-American and Hispanic/Latino youth: A systematic review, 1988–2012. The Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;54:369–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.11.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Gonzalez HM, Williams S, Mohammed SA, Moomal H, Stein DJ. Perceived discrimination, race and health in South Africa. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67:441–452. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.021. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Application of the theory of gender and power to examine HIV-related exposures, risk factors, and effective interventions for women. Health Education & Behavior. 2000;27:539–565. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700502. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/109019810002700502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]