Abstract

AIM

To explore the possibility of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (hUCMSCs), human umbilical vein endothelial cells (hUVECs), human dental pulp stem cells (hDPSCs) and human periodontal ligament stem cells (hPDLSCs) serving as feeder cells in co-culture systems for the cultivation of limbal stem cells.

METHODS

Different feeder layers were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/F12 and were treated with mitomycin C. Rabbits limbal stem cells (LSCs) were co-cultured on hUCMSCs, hUVECs, hDPSCs, hPDLSCs and NIH-3T3, and then comparative analysis were made between each group to see their respective colony-forming efficiency (CFE) assay and immunofluorescence (IPO13,CK3/12).

RESULTS

The efficiency of the four type cells in supporting the LSCs morphology and its cellular differentiation was similar to that of NIH-3T3 fibroblasts as demonstrated by the immunostaining properties analysis, with each group exhibiting a similar strong expression pattern of IPO13, but lacking CK3 and CK12 expression in terms of immunostaining. But hUCMSCs, hDPSCs and hPDLSCs feeder layers were superior in promoting colony formation potential of cells when compared to hUVECs and feeder-cell-free culture.

CONCLUSION

hUCMSCs, hDPSCs and hPDLSCs can be a suitable alternative to conventional mouse NIH-3T3 feeder cells, so that risk of zoonotic infection can be diminished.

Keywords: limbal stem cells, feeder layers, umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells, umbilical vein endothelial cells, dental pulp stem cells, periodontal ligament stem cells

INTRODUCTION

Limbal stem cells (LSCs) are of great significance as a regenerative source of corneal epithelial cells in maintaining of corneal transparency and repairing damaged corneal surface[1]–[2]. Damage to the limbal area by chemical burns, autoimmune diseases, infections or hereditary conditions may cause limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD), which may further result in poor corneal epithelialization, corneal neovascularization, persistent epithelial defects, corneal conjunctivalization, corneal scarring and so on. In turn, these problems may lead to blepharospasm, photophobia, pain, redness, tearing, decreased vision and even corneal blindness[3]–[5]. LSCD affects millions of people worldwide[6]. The number of corneal LSCs determines the success of tissue engineering cornea transplantion. Using mouse embryonic 3T3 feeder layer can greatly increase the number of stem cells and it's useful in supporting of the tagert cells[7]. However, the mouse feeder cells contains N-glycolylneuraminic acid and nonhuman sialic acid (Neu5Gc), an immune response could be induced when we use the cells for transplantion, since most people have Neu5Gc circulating antibodies[8]–[9]. In this study, in order to overcome the potential risks of possible immunological rejection caused by using such cells in clinical xenotransplantation, we used different human-derived feeder layers for the ex vivo expansion of LSCs and cultivated LSCs in a coculture system using human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (hUCMSCs), human umbilical vein endothelial cells (hUVECs), human dental pulp stem cells (hDPSCs), human periodontal ligament stem cells (hPDLSCs) and NIH-3T3 fibroblasts. Then their ability of expanding limbal cells and maintaining undifferentiated state were compared to evaluate whether these four cells can be used as feeder cells that could avoid zoonotic hazards.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Fetal bovine serum (FBS), Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/F12 were purchased from Hyclone (Logan, UT, USA); Minimum Essential α-Minimum (α-MEM), M199 Medium, penicillin, streptomycin and trypsin-EDTA were purchased from Invitrogen-Gibco (Grand Island, NY, USA); 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was purchased from Roche Life Science (Indianapolis, IN, USA); Mitomycin C and dispase were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Corp (St. Louis, MO, USA); The secondary antibodies were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, UK), anti-CD31, CD45 and CD90 antibodies were purchased from BD Pharmingen (1:1000; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA), respectively. The NIH-3T3 fibroblast used in the study were contributed by the Laboratory of Ophthalmology, Third Military Medical University of University. All the experimental animals were treated in accordance with the principle listed in ARVO Statement and with the approval of the Xinjiang Medical University Ethics Committee, and the experimental platform was provided by Xinjiang Medical University Institute of Clinical Medicine.

Methods

hUCMSCs, hUVECs culture and identification

A total of 10 healthy human umbilical cords were collected from healthy mothers at the No.474 Hospital of Chinese PLA following their informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee, No.474 Hospital of Chinese PLA in China. And all tissues were tested for HIV and hepatitis Isolation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) from cord tissue. Approximately 5-cm long pieces of human umbilical cords were collected and cut into smaller pieces and washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Then they were put into dishes containing an appropriate volume of collagenase type I that allowed the Wharton's jelly to come into contact with the enzymes. The dishes were then incubated in water bath at 37°C for 40min to allow loosening and separation of the Wharton's jelly. The hUCMSCs were cultured for expansion in DMEM/F12, containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (pen/strep), at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. When the MSCs at P3-P5 to appraise the multipotent differentiation capacity, the cells were treated with adipogenic supplements medium (1 mmol/L dexamethasone, 10 µg/mL insulin, 1 mmol/L 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine, 50 µmol/L indomethacin) and osteogenic induction medium (0.1 mmol/L dexamethasone, 10 mmol/L β-glycerophosphate, 0.05 mmol/L ascorbic acid) for 10 to 21d as described previously[10]. After the differentiation process was completed, cells were dyed with Oil-red O for adipocytes and Alizarin red for osteoblasts. A part of MSCs were incubated with FITC-conjugated mouse anti-human antibodies for CD45 and CD90 (1:1000; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA) for 10min at room temperature. The umbilical veins were carefully excised with 0.1% collagenase treatment and were cultured in endothelial cell growth media (M199) at 37°C for 0.5h as previously described[11]. Replace M199 medium into DMEM/F12 medium step by step after subculturing. The purity of extracted HUVECs was identified by flow cytometric analysis to compare the expression of the endothelial marker CD31.

hPDLSCs, hDPSCs culture and identification

Periodontal ligament and dental pulp tissues were obtained from 12 to 24-year old patients undergoing impacted mandibular third molar extraction of Stomatology Department of No.474 Hospital of Chinese PLA. Donors signed an informed consent according to the Ethics Committee of our Institution. The periodontal ligament and attached gingival tissue were scraped from the root surface of healthy extracted impacted tooth and extraction of the pulp from tooth that both were sterilised with PBS. The tissue was chopped with a ophthalmic scissors into small sections, and the suspension was incubated in α-MEM containing 10% FBS and 1% antibiotics at 37°C in incubator for 3-5d. When the cells stretched out from the tissue sections were re-plated, the media started to replace every 3d until the cells had grown to the appropriate confluency. Then replace α-MEM medium into DMEM/F12 medium step by step. hPDLSCs and hDPSCs identification were the same as the description of hUCMSCs identification above.

Feeder Cell Preparation

Cultivation of hUCMSCs, hUVECs, hDPSCs, hPDLSCs and NIH-3T3 were maintained in DMEM/F12 with 10% FBS eventually. To determine the minimum effective concentration of mitomycin C (Sigma) for the three cells, treated with 0, 1, 2, 4, 6 and 8 µg/mL of mitomycin C and plated in 96-well plates. Use MTT assay to test the cellular proliferation activity of growth arrested feeder cells then to confirm the minimum concentration of inhibition of cell proliferation. When the cells of P3 at 80% confluence, all the types of cells were treated with the minimal effective concentrations of mitomycin C for 2.5h at incubator to arrest cell growth. After incubation, the cells were washed with PBS twice for 3min each, the cells were then disassociated with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA and replated at a count of 5×104 cells seeded per well in 6-well plates and incubated at 37°C overnight[6].

Cultivation of Limbal Stem Cells

The limbal rims of New Zealand white rabbits weighing 1.5-2 kg were purchased from the Xinjiang Medical University Animal Center (Xinjiang, China). Superior limbal tissue was extensively washed with 1% pen/strep in PBS three times, then the limbal rims were exposed to 2.4 U/mL dispase II and incubated at 37°C thermostat water bath for 1.5h. Then the epithelial sheet was removed by scraping and was separated into single cells by 0.25% trypsin-0.02 % EDTA for 15min. Limbal cells were plated at 1×103 cells in cell culture dishes containing mitomycin C-treated hUCMSCs, hUVECs, hPDLSCs and NIH-3T3 feeder cells.

Colony Forming Efficiency

Compare colony forming ability of cultured LSCs with the four feeder layers. About 8d we could count the formed LSCs colonies, then the cultures were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15min and stained with 0.1% crystal violet-solution for 10min. Then colony formation was assessed under a dissecting microscope. We counted a group of more than 40 contiguous cells that was defined as a colony and the colony-forming efficiency (CFE) was calculated.

Immunocytochemistry

Limbal cells cultivated with the four feeders were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1h at room temperature before blocking and permeabilizing with 3% BSA in PBS with 1% Triton X-100. The specimens were incubated in mouse anti-karyopherin-13 (1:300, Santa Cruz, Biotechnology, CA, USA) and mouse anti-cytokeratin-3/12 (1:150, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) in 1% BSA overnight at 4°C. After being washed with PBS, cells were incubated with the fluorophore conjugated secondary antibodies (1:400, Alexa Fluor, 647) for 1h at room temperature and counterstained with DAPI contained in the mounting medium. All experiments were carried out in triplicate.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS 17.0. The quantification data were expressed as means± standard deviation (SD). Comparisons between the mean variables of multiple groups were performed using one-way ANOVAs and least significant difference test (LSD-test) was adopted further for comparisons between each dose group and the vehicle group. The P-value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Biological Characterization of hUCMSCs, hUVECs, hPDLSCs and hPDLSCs

The isolated hUCMSCs, hDPSCs and hPDLSCs demonstrated a fibroblast-like phenotype and hUVECs displayed a short-fibroblast-like morphology (Figure 1). After the cells were cultured in diffrerentitation mediums as described previously, we could observe adipogenic differentiation by Oil Red O-positive cells and osteogenic differentiation by Alizarin Red S-positive cells[12]–[16]. Flow cytometric analysis showed that hUCMSCs, hDPSCs and hPDLSCs had high expression levels of mesenchymal stem cell markers CD90 and low level expression for hematopoietic cells surface markers CD45 (Table 1). And high expression (94.3%) of specific endothelial marker CD31 was tested in hUVECs.

Figure 1. Morphology of hUCMSCs, hUVECs, hDPSCs and hPDLSCs.

A: P4 of hUCMSCs (×50); B: P2 of hUVECs (×100); C: P3 of hDPSCs (×100); D: P3 of hPDLSCs (×100).

Table 1. Flow cytometry showing the cells characteristics.

| Groups | Blank | CD45 | CD90 |

| hUCMSCs group | 0.6 | 0.2 | 88.2 |

| hDPSCs group | 0.2 | 0.4 | 89.0 |

| hPDLSCs group | 1.7 | 1.4 | 94.6 |

%

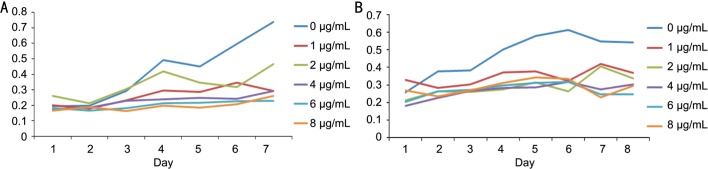

Optimum Concentration Mitomycin C Act on the Feeder Layers

The 4 µg/mL mitomycin C acting on different cells for 2.5h was the minimum concentration for inhibiting cell proliferation and keeping the optimum cell viability (Figure 2). All feeder cells were treated with 4 µg/mL mitomycin C in 10% FBS DMEM/F12 for 2.5h, rinsed with PBS, trypsinized and resuspended in the medium for later use.

Figure 2. MTT assay test the influence of different concentration of mitomycin C for the cell proliferation rates.

A: Influence on the hUCMSCs; B: Influence on the hPDLSCs.

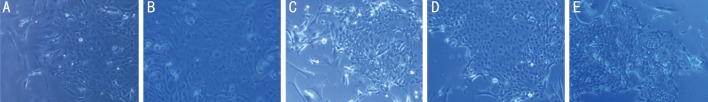

Ligament Stem Cell Proliferation in Different Cultures

Limbal cells grew as colonies with distinct boundaries for 8d, and the cells have a regular cuboidal shape similarity for all types of feeder cells. All the colonies could maintain small, compact and uniform cell morphology particularly from PDLSCs, which was most similar to that of 3T3 feeder layer. In this context all the feeder layers had a similar growth pattern of limbal cells that could support ex vivo culture of them as well as 3T3 feeder layer (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Morphology and growth profile of freshly collected LSCs (P0).

The LSCs cultivated with hUCMSCs (A), hUVECs (B), hDPSCs (C), hPDLSCs (D) and NIH-3T3 (E) on day 8 (×100).

Colony-forming Efficiency

This detection aimed to compare the capacity of the three types of cells with 3T3 cells as feeder layer to aid colony formation. Based simply upon the number of discrete islands, the hPDLSCs feeder cells displayed the best CFE with an average of 4.90%±0.96%, higher than other groups of clone formation rates. Overall difference between the four groups was statistically significant (F=18.293, P<0.01). Compared hUCMSCs, hDPSCs, hPDLSCs group respectively with NIH-3T3 group, their CFE had no significant difference statistically (t=1.09, 1.16, 0.45, P>0.05). The CFE of the hUVECs groups were lower than that of cells grown on 3T3 feeder (t=3.09, P<0.01). The four feeder layer were different with no feerder cells (t=6.31, 4.31, 6.24, 7.16, P<0.01) (Table 2).

Table 2. No. of LSCs colony forming efficiency of different feeder layers.

| Groups | CFE (%) |

| A hUCMSCs group | 4.10±0.56 |

| B hUVECs group | 3.37±0.50 |

| C hDPSCs group | 4.07±0.65 |

| D hPDLSCs group | 4.90±0.96 |

| E NIH-3T3 group | 4.67±0.76 |

| F No feeder group | 0.83±0.35 |

F=15.08 (F-test for the single-factor ANOVA), P<0.01.

mean±SD

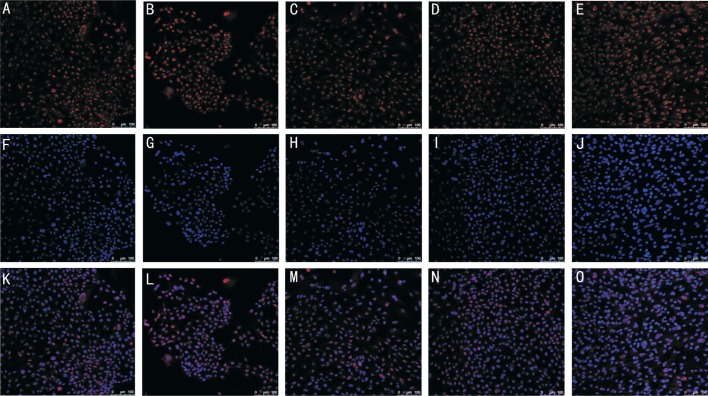

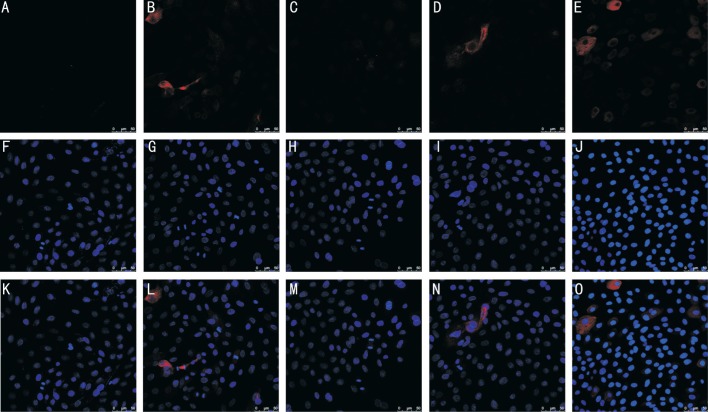

Expression of Putative Stem Cell Markers in the Clones of Limbal Cells

The remarkable phenotype was consisted of small and compact cells with high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio and showed positive expression for IPO13 (Figure 4) and negative expression for CK3/12 (Figure 5), all of which accorded with a more immature progenitor phenotype.

Figure 4. Cellular localization of LSC markers by fluorescent immunostaining.

LSCs on three types of feeder layer were subjected to immunostaining against IPO13 (A-E). DAPI depicts cell nuclei (F-J). Merged images were shown in (K-O). A, F, K: LSCs on hUCMSCs; B, G, L: LSCs on hUVECs; C, H, M: LSCs on hDPSCs; D, I, N: LSCs on hPDLSCs; E, J, O: LSCs on 3T3 fibroblasts.

Figure 5. Cellular localization of LSC markers by fluorescent immunostaining.

LSCs on three types of feeder layer were subjected to immunostaining against CK3/12 (A-E). DAPI depicts cell nuclei (F-J). Merged images are shown in (K-O). A, F, K: LSCs on hUCMSCs; B, G, L: LSCs on hUVECs; C, H, M: LSCs on hDPSCs; D, I, N: LSCs on hPDLSCs; E, J, O: LSCs on 3T3 fibroblasts.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the four kinds of feeder layers we used have the following significant advantages. Firstly, the selected four types of cells were derived from abandoned organization that they enjoyed absolute advantage in source. hDPSCs and hPDLSCs hold excellent promise as sources of adult stem cells potential for utilization in regenerative medicine[17]–[18], and they even can be derived from patients themselves. So we take for that they may become the better potential breeding source layer. Secondly, the immunogenicity of the hUCMSCs and hUVECs is very weak. Recent animal experiments have shown that our body doesn't reject hUCMSCs[19]. Thirdly, compared with bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells[20] and skin fibroblasts[21]–[22], the obtain of umbilical cord and teeth does not impose certain degree of damage to the organizational structure of the human body.

By far, there wasn't any research that has involved so many cells to see their comparative effectiveness with 3T3 feeder layer. In this study, hPDLSCs had a powerful ability of inducing osteoblastic differentiation and cell proliferation activity, the clone groups of LSCs formed were closer to 3T3 feeder layer than others. hPDLSCs had similar characteristics with MSCs that both could express CD73, CD90, CD105 without expressing hematopoietic cells surface markers of CD14, CD20, CD34 and CD4[15],[23], and both could be differentiated into fat, osteogenesis and chondrocytes in vitro[24]–[25]. Therefore, we conclude that the efficient cell activity is a prerequisite for the cell to be a high quality feeder layer.

Although many alternative techniques have been proposed such as amniotic membranes scaffolds and feeder-free explant cultures and recent 2D and 3D[26]–[27], using feeder layers are still considered to be the best method. Chen et al[28] found that hUVEC coculture with hUCMSCs, hiPSC-MSCs, hESC-MSCs and human bone mesenchymal stem cells (hBMSCs) in calcium phophate cement scaffold could achieve excellent osteogenic and angiogenic capability in vivo as a result of their ability to preserve some critical properties of LSCs such as cell growth viability and stemness phenotype[29]. Various alternative methods to culture LSCs are being explored currently. Ang et al[30] showed that mucin-expressing cord lining epithelial cells could substitute for 3T3 fibroblasts as feeder layer to culture LSCs. In addition, Scafetta et al[31] showed that human Tenon's fibroblasts could replace both 3T3 and human dermal fibroblasts (DF), potentially providing a appropriate microenvironment for LSCs culture. There are other feeder layers such as human limbal mesenchymal cells, hBMSCs, human DF and no feeder cells, but currently there is still no clinical trials employing human feeder layers for LSCs expansion.

No specific marker for the LSCs has been found yet. But IPO13, newest member of importin-β family is believed to be the putative one. IPO13 is uniquely expressed by human limbal basal epithelial cells and plays an important role in maintaining the phenotype, high proliferative potential and diminishing differentiation of corneal epithelial progenitor cells[32]. Limbal and cornea tissues revealed that CK3 was not expressed in basal limbal epithelial cells while it could be strongly expressed in the whole corneal epithelium and suprabasal limbal epithelial cells[33]. The co-cultured LSCs were turned out to be able to express the putative stem cell marker of IPO13 but did not express the differentiation related markers of CK3/CK12. In order to make sure that the sells we cultured were LSCs, we also observed the cell morphology[34]–[38]. Our research showed that the efficiency of the four types cells in supporting the cellular differentiation of LSCs was similar to that of NIH-3T3 fibroblasts through immunostaining properties analysis. It also showed that hUCMSCs, hDPSCs and hPDLSCs feeder layers were superior in promoting colony formation potential of cells compared with hUVECs and feeder-free culture. And the colonies on the three types of feeder layers especially LSCs clone colonies formed by PDLSCs share the similar characteristic with that of 3T3, this is, maintaining small, compact and uniform cell morphology. Moreover, for the adults, PDLSCs is undoubtedly the better choice when using autologous cells for tranplant because it's difficult for us to preserve our own hUCMSCs and hUVECs.

In summary, the study showed that the three feeder cells of hUCMSCs, hDPSCs and PDLSCs could substitute for 3T3 fibroblasts to be feeder layer for LSCs culturing. And it is worth mentioning that, in perspective of the ability of LSCs amplication, PDLSCs could be the idealest substitutes for feeder layer among the three to reduce the potential risk of xenogenic contamination.

Acknowledgments

Foundation: Supported by the Project Plan of Science and Technology Assistance in Xinjiang Autonomous Region (No.201491171).

Conflicts of Interest: Wang HX, None; Gao XW, None; Ren B, None; Cai Y, None; Li WJ, None; Yang YL, None; Li YJ, None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cauchi PA, Ang GS, Azuara-Blanco A, Burr JM. A systematic literature review of surgical interventions for limbal stem cell deficiency in humans. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146(2):251–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen YT, Li W, Hayashida Y, He H, Chen SY, Tseng DY, Kheirkhah A, Tseng SC. Human amniotic epithelial cells as novel feeder layers for promoting ex vivo expansion of limbal epithelial progenitor cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25(8):1995–2005. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sareen D, Saghizadeh M, Ornelas L, Winkler MA, Narwani K, Sahabian A, Funari VA, Tang J, Spurka L, Punj V, Maguen E, Rabinowitz YS, Svendsen CN, Ljubimov AV. Differentiation of human limbal-derived induced pluripotent stem cells into limbal-like epithelium. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2014;3(9):1002–1012. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2014-0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He H, Yiu SC. Stem cell-based therapy for treating limbal stem cells deficiency: a review of different strategies. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2014;28(3):188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan EH, Chen L, Rao JY, Yu F, Deng SX. Limbal basal cell density decreases in limbal stem cell deficiency. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160(4):678–684.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2015.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kolli S, Ahmad S, Lako M, Figueiredo F. Successful clinical implementation of corneal epithelial stem cell therapy for treatment of unilateral limbal stem cell deficiency. Stem Cells. 2010;28(3):597–610. doi: 10.1002/stem.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chugh RM, Chaturvedi M, Yerneni LK. Occurrence and control of sporadic proliferation in growth arrested Swiss 3T3 feeder cells. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e122056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin MJ, Muotri A, Gage F, Varki A. Human embryonic stem cells express an immunogenic nonhuman sialic acid. Nat Med. 2005;11(2):228–232. doi: 10.1038/nm1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tangvoranuntakul P, Gagneux P, Diaz S, Bardor M, Varki N, Varki A, Muchmore E. Human uptake and incorporation of an immunogenic nonhuman dietary sialic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(21):12045–12050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2131556100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kita K, Gauglitz GG, Phan TT, Herndon DN, Jeschke MG. Isolation and characterization of mesenchymal stem cells from the sub-amniotic human umbilical cord lining membrane. Stem Cells Dev. 2010;19(4):491–502. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen X, Chen B, Yang Y, Zhou Y, Liu F, Gai M, Chen Q, Ma Y. Isolation, culture and identification of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Xi Bao Yu Fen Zi Mian Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2016;32(3):328–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo ZY, Sun X, Xu XL, Zhao Q, Peng J, Wang Y. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells promote peripheral nerve repair via paracrine mechanisms. Neural Regen Res. 2015;10(4):651–658. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.155442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar A, Bhattacharyya S, Rattan V. Effect of uncontrolled freezing on biological characteristics of human dental pulp stem cells. Cell Tissue Bank. 2015;16(4):513–522. doi: 10.1007/s10561-015-9498-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kadekar D, Kale V, Limaye L. Differential ability of MSCs isolated from placenta and cord as feeders for supporting ex vivo expansion of umbilical cord blood derived CD34(+) cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6:201. doi: 10.1186/s13287-015-0194-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tran Hle B, Doan VN, Le HT, Ngo LT. Various methods for isolation of multipotent human periodontal ligament cells for regenerative medicine. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2014;50(7):597–602. doi: 10.1007/s11626-014-9748-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ji K, Liu Y, Lu W, Yang F, Yu J, Wang X, Ma Q, Yang Z, Wen L, Xuan K. Periodontal tissue engineering with stem cells from the periodontal ligament of human retained deciduous teeth. J Periodont Res. 2013;48(1):105–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2012.01509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan M, Yu Y, Zhang G, Tang C, Yu J. A journey from dental pulp stem cells to a bio-tooth. Stem Cell Rev. 2011;7(1):161–171. doi: 10.1007/s12015-010-9155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kadar K, Kiraly M, Porcsalmy B, Molnar B, Racz GZ, Blazsek J, Kallo K, Szabo EL, Gera I, Gerber G, Varga G. Differentiation potential of stem cells from human dental origin - promise for tissue engineering. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;60(Suppl 7):167–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liao W, Xie J, Zhong J, Liu Y, Du L, Zhou B, Xu J, Liu P, Yang S, Wang J, Han Z, Han ZC. Therapeutic effect of human umbilical cord multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells in a rat model of stroke. Transplantation. 2009;87(3):350–359. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318195742e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Markel TA, Crafts TD, Jensen AR, Hunsberger EB, Yoder MC. Human mesenchymal stromal cells decrease mortality after intestinal ischemia and reperfusion injury. J Surg Res. 2015;199(1):56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2015.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quan C, Cho MK, Shao Y, Mianecki LE, Liao E, Perry D, Quan T. Dermal fibroblast expression of stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) promotes epidermal keratinocyte proliferation in normal and diseased skin. Protein Cell. 2015;6(12):890–903. doi: 10.1007/s13238-015-0198-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oie Y, Hayashi R, Takagi R, Yamato M, Takayanagi H, Tano Y, Nishida K. A novel method of culturing human oral mucosal epithelial cell sheet using post-mitotic human dermal fibroblast feeder cells and modified keratinocyte culture medium for ocular surface reconstruction. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94(9):1244–1250. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.175042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodriguez-Lozano FJ, Garcia-Bernal D, Aznar-Cervantes S, Ros-Roca MA, Alguero MC, Atucha NM, Lozano-Garcia AA, Moraleda JM, Cenis JL. Effects of composite films of silk fibroin and graphene oxide on the proliferation, cell viability and mesenchymal phenotype of periodontal ligament stem cells. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2014;25(12):2731–2741. doi: 10.1007/s10856-014-5293-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujii S, Maeda H, Wada N, Tomokiyo A, Saito M, Akamine A. Investigating a clonal human periodontal ligament progenitor/stem cell line in vitro and in vivo. J Cell Physiol. 2008;215(3):743–749. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tomokiyo A, Maeda H, Fujii S, Wada N, Shima K, Akamine A. Development of a multipotent clonal human periodontal ligament cell line. Differentiation. 2008;76(4):337–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2007.00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Utheim TP, Lyberg T, Raeder S. The culture of limbal epithelial cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1014:103–129. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-432-6_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dziasko MA, Tuft SJ, Daniels JT. Limbal melanocytes support limbal epithelial stem cells in 2D and 3D microenvironments. Exp Eye Res. 2015;138:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2015.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen W, Liu X, Chen Q, Bao C, Zhao L, Zhu Z, Xu HH. Angiogenic and osteogenic regeneration in rats via calcium phosphate scaffold and endothelial cell coculture with hBMSCs, hUCMSCs, hiPSC-MSCs and hESC-MSCs. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Scafetta G, Siciliano C, Frati G, De Falco E. Culture of human limbal epithelial stem cells on tenon's fibroblast feeder-layers: a translational approach. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1283:187–198. doi: 10.1007/7651_2014_102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ang LP, Jain P, Phan TT, Reza HM. Human umbilical cord lining cells as novel feeder layer for ex vivo cultivation of limbal epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(8):4697–4704. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scafetta G, Tricoli E, Siciliano C, Napoletano C, Puca R, Vingolo EM, Cavallaro G, Polistena A, Frati G, De Falco E. Suitability of human Tenon's fibroblasts as feeder cells for culturing human limbal epithelial stem cells. Stem Cell Rev. 2013;9(6):847–857. doi: 10.1007/s12015-013-9451-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang H, Tao T, Tang J, Mao YH, Li W, Peng J, Tan G, Zhou YP, Zhong JX, Tseng SC, Kawakita T, Zhao YX, Liu ZG. Importin 13 serves as a potential marker for corneal epithelial progenitor cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27(10):2516–2526. doi: 10.1002/stem.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang X, Sun H, Li X, Yuan X, Zhang L, Zhao S. Utilization of human limbal mesenchymal cells as feeder layers for human limbal stem cells cultured on amniotic membrane. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2010;4(1):38–44. doi: 10.1002/term.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schlotzer-Schrehardt U, Kruse FE. Identification and characterization of limbal stem cells. Exp Eye Res. 2005;81(3):247–264. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolosin JM, Budak MT, Akinci MA. Ocular surface epithelial and stem cell development. Int J Dev Biol. 2004;48(8-9):981–991. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.041876jw. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arpitha P, Prajna NV, Srinivasan M, Muthukkaruppan V. High expression of p63 combined with a large N/C ratio defines a subset of human limbal epithelial cells: implications on epithelial stem cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(10):3631–3636. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ksander BR, Kolovou PE, Wilson BJ, Saab KR, Guo Q, Ma J, McGuire SP, Gregory MS, Vincent WJ, Perez VL, Cruz-Guilloty F, Kao WW, Call MK, Tucker BA, Zhan Q, Murphy GF, Lathrop KL, Alt C, Mortensen LJ, Lin CP, Zieske JD, Frank MH, Frank NY. ABCB5 is a limbal stem cell gene required for corneal development and repair. Nature. 2014;511(7509):353–357. doi: 10.1038/nature13426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grueterich M, Espana EM, Tseng SC. Ex vivo expansion of limbal epithelial stem cells: amniotic membrane serving as a stem cell niche. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48(6):631–646. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]