Abstract

Experimental research on alcohol-related aggression has focused largely upon male participants, providing only a limited understanding of the proximal effects of acute alcohol use on aggression among females extrapolated from the male literature. The current meta-analysis was undertaken to summarize the effects of alcohol, compared to placebo or no alcohol, on female aggression as observed across experimental investigations. Method. A review of the literature yielded 11 articles and 12 effect sizes for further analysis. Results. The overall effect size of alcohol on female aggression was small and reached statistical significance (d = .17, p = .02, 95% CI = .03–.30). Discussion. Meta-analytic examination of the experimental literature indicated that alcohol is a significant factor in female aggression. The overall alcohol-aggression effect was smaller than has been observed among male samples. Additional research is required to evaluate the influence of other factors on alcohol-related aggressive responding among female participants.

Keywords: Alcohol, aggression, female participants, meta-analysis, experimental research

Human aggressive behavior has been broadly defined as verbal or physical actions carried out with the intent or desire to inflict harm upon another person (Anderson & Bushman, 2002). Aggressive impulses or urges to aggress are so common that they are considered to be a normative part of the human experience (Finkel & Eckhardt, 2013). Acting on aggressive impulses, particularly when such actions result in physical harm to another, however, is far less common and may constitute pathological behavior when chronic or severe (e.g., Hoppenbrouwers et al., 2013). Alcohol has demonstrated the potential to override inhibitory processes and contribute to an increased risk of aggressive behavioral responding among male samples (e.g., Ito et al., 1996). The effects of alcohol on female aggression, however, are poorly understood (Parker & Auerhahn, 1998). The omission of females from the alcohol-related aggression literature is particularly concerning given the proliferation of evidence indicating that females are responsible for perpetrating a non-trivial portion of violent offenses, including stalking (Harmon, Rosner, & Owens, 1998), intimate partner violence (Desmarais et al., 2012), sexual assault (Fisher & Pina, 2013), robbery (Rennison & Melde, 2014), and homicide (Campbell et al., 2007). The current review aims to consolidate the existing experimental research that has examined the proximal effects of acute alcohol use on female aggression.

Alcohol use is thought to override inhibitory processes and thus act as a behavioral disinhibitor, increasing the risk of aggression as a consequence of alcohol’s proximal psychopharmacological properties (e.g., Giancola et. al., 2010). Alcohol exerts global effects on the brain, which include disruption of higher order cognitive information processing and executive functioning at moderate doses (e.g., Giancola, 2000). Affected cognitive abilities include abstract reasoning skills, goal-oriented planning, and self-monitoring, all of which impair optimal social information processing and result in selective attention to only the most salient environmental cues (Steele & Josephs, 1990). Therefore, once instigated by aggressive prompts (e.g, perceiving an insult or challenge), individuals may be more likely to attend to such information at the expense of less salient cues or distal consequences that may promote nonaggressive responding (e.g., the consequences of reciprocal aggression, pain, jail, or relationship dissolution) (Taylor & Leonard, 1983; Steele & Josephs, 1990).

Prior research has established a small-to-medium sized effect of alcohol on aggressive behavior among males (e.g., d = .54; Lipsey, Wilson, Cohen, & Derzon, 1997). The effect of alcohol on male aggression has been detected using distal, self-report data of problematic alcohol use (e.g., d = .47; Foran & O’Leary, 2008). In addition, a recent meta-analytic review of experimental literature on male-to-female aggression found a consistent effect of administered alcohol across various forms of aggressive behavior, including sexual aggression (d = .32), intimate partner aggression (d = .45), and non-sexual aggression toward female strangers (d = .46; Crane, Godleski, Przybyla, Schlauch, & Testa, 2016). Further, the association between alcohol and male aggressive behavior appears to be cross-cultural with significant effects across geographical regions and ethnic groups (e.g., Caetano, Schafer, & Cunradi, 2001).

The literature on aggressive behavior and alcohol use among females appears far less complete. Early meta-analytic reviews of the experimental literature have reported small effects of alcohol on aggression among females in comparison to their male counterparts. For example, Ito and colleagues (1996) reported that the effect size for alcohol on aggression was larger among studies involving only male participants (k = 46, d = .49) compared to studies involving only females or both genders (k = 4, d = .27). Similarly, Bushman (1997) concluded that alcohol seemed to exert greater effects on male (k = 59, d =.50) than female (k = 6, d = .13) aggression. Neither review found that the alcohol-aggression effect reached statistical significance among females, and both reviews concluded that analyses likely had insufficient power to detect significant effects due to limited data on female samples. More recently, Foran and O’Leary (2008) examined the results of eight studies to report a small effect size (d = .28) shared by self-reported distal alcohol use and retrospective reports of physical aggression among females. This effect reached significance but excluded experimental studies and, thus, did not assess the relationship between acute alcohol use and aggression. The authors again advised caution in interpreting the results due to the sparsity of research.

The current review

With the effects of acute alcohol use associated with aggressive behavior, research that assesses the proximal effects of alcohol is expected to yield the greatest insight into the alcohol-aggression relationship among females. Further, experimental investigations offer greater opportunity to assess the proposed causal relationship between alcohol use and female aggression (Exum, 2006). Previous reviews on alcohol use and female aggression have relied upon a sparse set of research articles and have either intentionally excluded or utilized insufficient experimental data upon which to draw conclusions about the effect of acute alcohol use on female aggression. We sought to quantify this relationship by synthesizing the relevant body of published, experimental research. Consistent with theory and previous reviews, we hypothesized that a small but significant effect of alcohol on female aggression would emerge.

Method

Sample

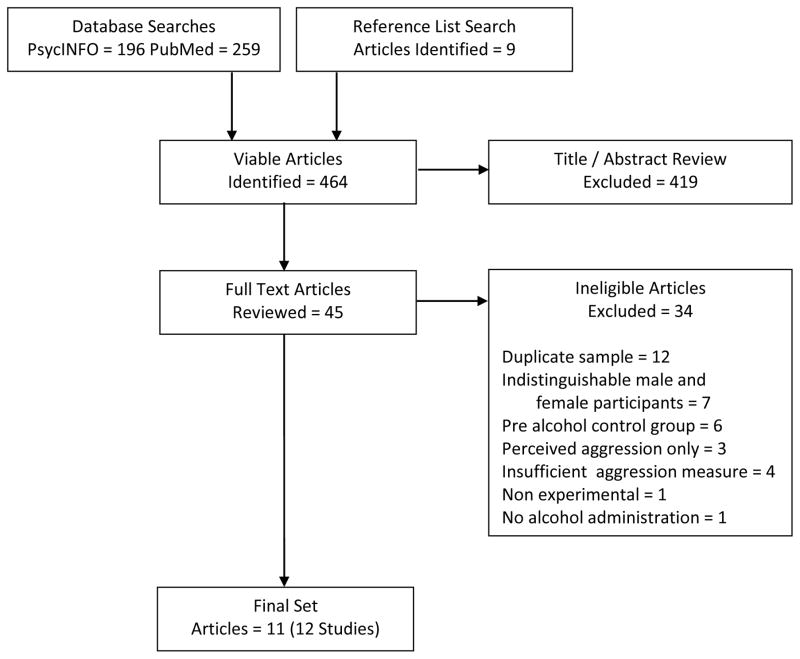

To identify studies examining the effects of acute alcohol use on female aggression, we searched PsycINFO and PubMed for reports containing any combination of keywords within the domains of alcohol (i.e., alcohol, drinking, ethanol, ETOH, Intoxication, intoxicated), experimental design (i.e., placebo, laboratory, experiment, alcohol administration, alcohol content), aggressive behavior (i.e., aggression, aggressive, violence, violent), and female gender (females, female, women, wife, wives, girlfriend, girlfriends). Additional filters were imposed to limit search results to dissertations or articles published in a peer reviewed journal that had been written in or translated to the English language and involved human subjects. The literature search was conducted in March of 2015 and imposed no earliest cutoff date. Reference list and review paper searches resulted in the detection of nine additional studies. A review of titles and abstracts narrowed prospective articles from an initial 464 to a set of 45. Full review resulted in a final sample of 11 articles and 12 effects (see Figure 1). The current manuscript was not eligible for human subjects ethics review due to the nature of the publicly available composite data utilized for the meta-analytic review.

Figure 1.

The selection and review process that resulted in 14 articles (15 studies) for inclusion in the current meta-analysis.

Procedure

Eligibility

To meet inclusion criteria, articles needed to describe a) an original experimental investigation involving active alcohol and control conditions,1 b) contain an identifiable female sample or subsample, and c) report quantifiable measures of aggression with sufficient data to estimate an effect size for the relationship between alcohol use and aggression.2 All articles were presented in English. The earliest published study was retained when we suspected that multiple studies utilized the same dataset. Nine articles were drawn from substance abuse journals, four from violence journals, and no dissertations met criteria.

Coding

All studies were coded at least once and seven studies (58.3%) were double coded by the first and second author using a structured codebook. Each study was evaluated for data pertaining to the sample, alcohol paradigms, as well as aggression outcomes of interest. Coders discussed and resolved all disputed codes prior to analyses.

Aggression

Eligible studies assessed an array of aggressive behaviors. Six studies used a variant of the Taylor Aggression Paradigm (TAP; Taylor, 1967), a competitive reaction time task in which a participant administers shocks to a fictitious opponent. Two studies appearing in the same article made us of a negative evaluative feedback paradigm (Rohsenow & Bachorowski, 1984). The remaining studies used a teacher/learner method (Gustafson, 1991), the conflict resolution paradigm in which romantic partners discuss an issue upon which they disagree (Testa, Crane, Quigley, Levitt, & Leonard, 2014), a first-person video vignette in which participants were asked to provide likely behavioral responses to provocation (Ogle & Miller, 2004), and the Articulated Thoughts in Simulated Situations paradigm (ATSS; Davison, Robins, & Johnson, 1983) in which participants verbally respond to ambiguous audio interactions between a simulated romantic partner and various other individuals (Eckhardt & Crane, 2008).

Data Analysis

Cohen’s d effect sizes were calculated using means and standard deviations (k = 8), t values (k = 2), and F values (k = 1) described within eligible articles. One study provided an effect size statistic in the form of Cohen’s d. Two articles reported nonsignificant effects without providing an exact t-statistic or p-value. Following prior convention, these p-values were set at .50 to approximate study effects and allow for inclusion in the current meta-analysis (Amato & Keith, 1991; Stith, Smith, Penn, Ward, & Tritt, 2004). The formulae to calculate effect sizes using these data were provided by Hedges and Olkin (1985) and are embedded in the online practical meta-analysis effect size calculator (a companion to Lipsey & Wilson, 2001) that was used in the current analyses. Studies with large, positive d values found that participants who received alcohol were more aggressive than participants who received no alcohol. Studies with large, negative d values found that participants who received no alcohol were more aggressive than participants who had received alcohol. Five studies used randomization procedures but failed to report specific subgroup sizes. Equivalent group sizes were estimated.

Data describing multiple alcohol groups or control groups were pooled accordingly to yield a single composite effect size for each study. Because no differences were detected between no-alcohol and placebo control groups in prior reviews examining aggression (e.g., Ito, Miller, Pollock, 1996) and particularly female aggression (Testa et al., 2006), these comparison groups were combined in the current analyses. Similarly, effect sizes were averaged within studies that presented multiple measures of aggression. In order to attribute greater weight to studies with large samples in the calculation of the overall effect of acute alcohol use on female aggression, effect sizes were weighted by the inverse of their variance (Hedges & Olkin, 1985).

Results

Sample description

Eleven articles yielded 12 effect sizes representing a total of 994 participants. Articles were published in peer reviewed journals between 1984 and 2015 with sample sizes ranging from 32 to 265 participants. Half of the studies (50.0%) specified a sample composed predominantly of Caucasians in the United States with no predominant ethnicity specified in the other investigations. The average participant age ranged from 22 to 32 across studies. The specified target alcohol dose ranged from a BAC of 0.08 to 0.10. With the exception of two investigations in which the target of aggression was an actual (Testa et al., 2014) or simulated (Eckhardt & Crane, 2008) romantic partner, participants were unfamiliar with the target.

Overall effect size

The overall effect size of d = .17 (p = .02, 95% CI = .03–.30) was detected using a random effects analysis of the 12 observed effect sizes (Table 1). The positive effect was small in magnitude and the confidence interval did not contain zero, indicating that the aggression exhibited by female participants who received alcohol was significantly greater than the aggression exhibited by control participants. A failsafe N helps account for the limitation of publication bias and revealed that 6 additional studies with null results would be needed to reduce the current effect size to the .10 level and that 192 would be required to reduce the effect size to .01 (Orwin, 1983; Rosenthal, 1991).

Table 1.

Description of studies (N = 12) included in the current meta-analytic review

| Authors, Publication Year | Sample Size | Aggression Measure | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eckhardt & Crane, 2008 | 33 | Articulated Thoughts | .234 |

| Giancola et al., 2002 | 46 | Taylor Aggression Paradigm | .413 |

| Giancola et al., 2009 | 265 | Taylor Aggression Paradigm | .249 |

| Giancola & Parrott, 2008 | 165 | Taylor Aggression Paradigm | .109 |

| Giancola & Zeichner, 1995 | 64 | Taylor Aggression Paradigm | .553 |

| Gustafson, 1991 | 45 | Teacher-Learner | −.088 |

| Hoaken et al., 2003 | 32 | Taylor Aggression Paradigm | .400 |

| Hoaken & Pihl, 2000 | 60 | Taylor Aggression Paradigm | .178 |

| Ogle & Miller, 2004 | 41 | Video Vignette | −.177 |

| Rohsenow & Bachorowski, 1984 (Study 1) | 48 | Negative Feedback Evaluation | .620 |

| Rohsenow & Bachorowski, 1984 (Study 2) | 45 | Negative Feedback Evaluation | −.206 |

| Testa et al., 2014 | 150 | Conflict Resolution | −.090 |

|

| |||

| TOTAL | 994 | d = .166 (p = .02, 95% CI = .03 – .30) | |

An analysis of homogeneity detected no significant variability in the magnitude of observed effect sizes, which ranged from −0.21 to 0.62 (Q(11) = 12.25, p = .35). Removal of the strongest negative effect and the strongest positive effect changed neither the direction nor the significance of the overall effect (d = .16, k = 10, p = .02, 95% CI = .03 – .29). The heterogeneity of observed effect sizes across the limited number of studies identified in the literature warranted no further examination of moderators that may differentiate between small and large magnitude effects.

Discussion

The current analysis of the experimental literature revealed a significant, small effect size for the relationship between acute alcohol use and aggression, such that female participants who consumed alcohol exhibited greater aggression in response to a subsequent aggression paradigm than female participants who did not drink alcohol. We found homogeneous effects across 12 studies and 994 participants. Because current studies all used experimental designs, the overall test statistic allows us to conclude that alcohol use is a significant factor in acts of female aggression under controlled conditions. Thus, results provide support for our hypothesis.

In comparing the current results to previous findings, it should be noted that the observed effect size of experimentally administered alcohol on female aggression is weaker than indicated by distal associations (Foran & O’Leary, 2008). Survey research typically assesses the relationship between problematic drinking and aggression, two associated types of externalizing behavior. Experimental research, in response to potential ethical concerns, often recruits healthy, social drinkers without significant alcohol use problems. Indeed, none of the studies identified for inclusion in the current review recruited heavy, problematic, or clinically significant drinking samples. Thus, it is likely that the administration of moderate doses of alcohol to healthy, generally nonviolent participants may be insufficient to elicit aggression in most cases. Alcohol may serve as a contributing cause to a subset of participants with high dispositional aggressive tendencies (Finkel & Eckhardt, 2013); however we were unable to test this hypothesis with our limited data.

Based upon the results of prior meta-analyses, the effect of experimentally administered alcohol on female aggression also seems to be smaller than has been observed among their male counterparts (e.g., Crane et al., 2016). This is not entirely surprising given that both gender-inclusive survey (e.g., Foran & O’Leary, 2008) and experimental (e.g., Bond & Lader, 1986; Giancola & Zeichner, 1995; Hoaken & Pihl, 2000) research provide support for stronger effects of alcohol on male than female samples. Again, the stronger effects of alcohol may be capitalizing on the interaction between alcohol’s disinhibiting properties and greater dispositional aggressive tendencies among males (e.g., Anderson & Bushman, 2002). Further research is required to determine whether the overall effect of alcohol on aggression is statistically stronger among male compared to female participants.

As with previous reviews of the literature pertaining to alcohol-induced aggression among females, the most problematic limitation of the current review was the sparsity of eligible research. Limited research makes it difficult to detect heterogeneity among effect sizes and also presents a barrier to conducting and drawing meaningful conclusions from analyses meant to enhance our understanding of the individual and situational characteristics that increase the risk of aggression among females who have consumed alcohol. Nearly ten years ago, Exum (2006) observed that only six studies had evaluated the proximal effects of alcohol on female aggression as of 1997, prompting him to call for additional research into the phenomenon. Only 12 studies were detected for inclusion in the current meta-analytic review, conducted eighteen years later. With a publication rate of fewer than one investigation every two years and noting that it is only through further research that we can begin to comprehensively understand the effects of alcohol on female aggression, we echo the call from Exum (2006) for enhanced activity in this area. Ultimately, future research may aid in the development of prevention efforts to mitigate the risks posed by alcohol-involved female aggression, including the risk of victimization to the female aggressor, particularly in instances of intimate partner violence where female alcohol use and reciprocal aggression increase the likelihood and severity of injury (Crane et al, 2014; Stith et al., 2004).

The ecological validity of aggression paradigms has been questioned with assertions that behavioral response options offered under laboratory conditions do not adequately approximate those available in the real world (Tedeschi & Quigley, 1996). Further, the knowledge that one is being observed in the laboratory may prompt self-reflection on potential aggressive behavior, a situational inhibiting factor that could artificially help override the urge to aggress (e.g., Ito et al., 1996). While the current results allow us to conclude that alcohol is a significant factor in female aggression under controlled conditions, we cannot conclude that this effect generalizes to the aggression beyond the laboratory. Promising methods of naturalistic observation include daily diary and ecological momentary assessment (Moore, Elkins, McNulty, Kivisto, & Handsel, 2011; Testa & Derrick, 2014).

In conclusion, the current results implicate acute alcohol use as a contributing factor in female aggression. In comparison to previous reviews on alcohol-related aggression, the effects of alcohol appear to be diminished among female relative to male perpetrators. Additional laboratory and in vivo research is needed to elucidate the circumstances under which alcohol may contribute to the greatest harm. With the overwhelming majority of relevant, empirically supported treatments developed for and normed upon males, an understanding of gender-specific risk factors has vast clinical implications for generating treatments that may more effectively target the female client. Such implications include insight into risk reduction efforts and the promotion of targeted skills for female substance abuse treatment seekers who suffer from interpersonal problems and aggressive tendencies.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided, in part, by a grant from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (K23 AA021786; PI: Schlauch).

Footnotes

We identified two studies that were inappropriate for inclusion in the current analysis because they utilized a pre-posttest design in which assessments taken from participants during sober laboratory sessions served as controls for assessments taken from the same participants during intoxicated sessions. Effect sizes could not be calculated for either study without knowing the correlation between the two assessment periods. Dougherty, Chereck, and Bennett (1996) used a point subtraction paradigm to determine that a small sample of females (N=10) exhibited greater aggressive responding following high doses of alcohol. Jacob, Leonard, and Haber (2001) recruited 100 heavy drinking males and their partners to engage in a conflict resolution paradigm, reporting that wives responded more negatively toward husbands with high antisocial features during a drinking session rather than a sober session.

Three studies evaluated female perception of aggressive behavior perpetrated by males (Davis et al., 2006; Loiselle & Fuqua, 2007; Pumphrey-Gordon & Gross 2007). These measures were presented in the third person and reflect attitudes toward the aggressive behavior of others as a consistent facet of aggression. First and third person vignettes are a common methodology for studying male-to-female sexual aggression. The three studies that were identified for potential inclusion in the current review required female participants to comment on aggressive behaviors enacted by male characters. As this outcome represents perception of aggression rather than aggressive behavior itself, these studies were not included in the current analyses. Davis and colleagues (2006) concluded that females who had consumed alcohol were less likely to report male sexual aggression as rape than controls (d = .46), Loiselle and Fuqua (2007) found that alcohol assignment extended response latency among females assessing when a male character’s sexual aggression should stop (d = 1.40), and Pumphrey-Gordon and Gross (2007) reported that alcohol assignment reduced response latency among females assessing when a male character’s sexual advances had progressed too far (d = −.12).

Findings of the review from which the current data were drawn have appeared in: Crane, C., Licata, M., & Schlauch, R. (2016, July). The effects of alcohol on female responding during laboratory aggression paradigms. The annual meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism, New Orleans, LA.

Contributor Information

Cory A. Crane, Rochester Institute of Technology, Department of Biomedical Sciences, 180 Lomb Memorial Dr, Rochester, NY 14623.

MacKenzie L. Licata, Rochester Institute of Technology, Department of Biomedical Sciences, 180 Lomb Memorial Dr, Rochester, NY 14623

Robert C. Schlauch, University of South Florida, Department of Psychology, 4202 East Fowler Ave, Tampa, FL 33620

Maria Testa, Research Institute on Addictions, University at Buffalo, 1021 Main St., Buffalo, NY 14203.

Caroline J. Easton, Rochester Institute of Technology, Department of Biomedical Sciences, 180 Lomb Memorial Dr, Rochester, NY 14623

References

- Amato PR, Keith B. Parental divorce and adult well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1991;53:43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CA, Bushman BJ. Human aggression. Psychology. 2002;53:27–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond A, Lader M. The relationship between induced behavioural aggression and mood after the consumption of two doses of alcohol. British Journal of Addiction. 1986;81:65–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1986.tb00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushman BJ. Effects of alcohol on human aggression: Validity of proposed explanations. In: Galanter M, editor. Recent developments in alcoholism. Vol. 13. New York: Plenum; 1997. pp. 227–243. Alcohol and violence. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Schafer J, Cunradi CB. Alcohol-related intimate partner violence among white, black, and Hispanic couples in the United States. Alcohol Research and Health. 2001;25:58–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC, Glass N, Sharps PW, Laughon K, Bloom T. Intimate partner homicide review and implications of research and policy. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2007;8:246–269. doi: 10.1177/1524838007303505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane CA, Godleski SA, Przybyla SM, Schlauch RC, Testa M. The Proximal Effects of Acute Alcohol Consumption on Male-to-Female Aggression A Meta-Analytic Review of the Experimental Literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2016;17:520–531. doi: 10.1177/1524838015584374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane CA, Hawes SW, Mandel DL, Easton CJ. The occurrence of female-to-male partner violence among male intimate partner violence offenders mandated to treatment: a brief research report. Violence and Victims. 2014;29:940–951. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-12-00136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC, Norris J, George WH, Martell J, Heiman JR. Rape-myth congruent beliefs in women resulting from exposure to violent pornography: Effects of alcohol and sexual arousal. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:1208–1223. doi: 10.1177/0886260506290428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison GC, Robins C, Johnson MK. Articulated thoughts during simulated situations: A paradigm for studying cognition in emotion and behavior. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1983;7:17–39. [Google Scholar]

- Desmarais SL, Reeves KA, Nicholls TL, Telford RP, Fiebert MS. Prevalence of physical violence in intimate relationships, Part 2: Rates of male and female perpetration. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:170–198. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty DM, Cherek DR, Bennett RH. The effects of alcohol on the aggressive responding of women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1996;57:178–186. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Eckhardt CI, Crane C. Effects of alcohol intoxication and aggressivity on aggressive verbalizations during anger arousal. Aggressive Behavior. 2008;34:428–436. doi: 10.1002/ab.20249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exum ML. Alcohol and aggression: An integration of findings from experimental studies. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2006;34:131–145. [Google Scholar]

- Finkel EJ, Eckhardt CI. Intimate partner violence. In: Simpson JA, Campbell L, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Close Relationships. New York: Oxford University Press; 2013. pp. 452–474. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher NL, Pina A. An overview of the literature on female-perpetrated adult male sexual victimization. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2013;18:54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, O’Leary KD. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1222–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR. Executive functioning: a conceptual framework for alcohol-related aggression. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2000;8:576–597. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.4.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Giancola PR, Helton EL, Osborne AB, Terry MK, Fuss AM, Westerfield JA. The effects of alcohol and provocation on aggressive behavior in men and women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:64–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Josephs RA, Parrott DJ, Duke AA. Alcohol myopia revisited clarifying aggression and other acts of disinhibition through a distorted lens. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2010;5:265–278. doi: 10.1177/1745691610369467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Giancola PR, Levinson CA, Corman MD, Godlaski AJ, Morris DH, Phillips JP, Holt JCD. Men and women, alcohol and aggression. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;17:154–164. doi: 10.1037/a0016385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Giancola PR, Parrott DJ. Further evidence for the validity of the Taylor Aggression Paradigm. Aggressive Behavior. 2008;34:214–229. doi: 10.1002/ab.20235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Giancola PR, Zeichner A. An investigation of gender differences in alcohol-related aggression. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1995;56:573–579. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Gustafson R. Aggressive and nonaggressive behavior as a function of alcohol intoxication and frustration in women. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1991;15:886–892. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1991.tb00620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon RB, Rosner R, Owens H. Sex and violence in a forensic population of obsessional harassers. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. 1998;4:236–249. [Google Scholar]

- Hedges L, Olkin I. Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Academic Press; Orlando, FL: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- *.Hoaken PNS, Campbell T, Stewart SH, Pihl RO. Effects of alcohol on cardiovascular reactivity and the mediation of aggressive beahviour in adult men and women. Alcohol & Alcoholism. 2003;38:84–92. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agg022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Hoaken PN, Pihl RO. The effects of alcohol intoxication on aggressive responses in men and women. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2000;35:471–477. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/35.5.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppenbrouwers SS, De Jesus DR, Stirpe T, Fitzgerald PB, Voineskos AN, Schutter DJ, Daskalakis ZJ. Inhibitory deficits in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in psychopathic offenders. Cortex. 2013;49:1377–1385. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito TA, Miller N, Pollock VE. Alcohol and aggression: a meta-analysis on the moderating effects of inhibitory cues, triggering events, and self-focused attention. Psychological bulletin. 1996;120:60–82. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.120.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T, Leonard KE, Haber JR. Family interactions of alcoholics as related to alcoholism type and drinking condition. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25:835–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey M, Wilson D. Practical meta-analysis. Vol. 49. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW, Wilson BM, Cohen MA, Derzon JH. Is there a causal relationship between alcohol use and violence? In: Galanter M, editor. Recent developments in Alcoholism and Violence. Vol. 13. New York: Plenum Press; 1997. pp. 245–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loiselle M, Fuqua WR. Alcohol’s effects on women’s risk detection in a date-rape vignette. Journal of American College Health. 2007;55:261–266. doi: 10.3200/JACH.55.5.261-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore TM, Elkins SR, McNulty JK, Kivisto AJ, Handsel VA. Alcohol use and intimate partner violence perpetration among college students: Assessing the temporal association using electronic diary technology. Psychology of Violence. 2011;1:315–328. [Google Scholar]

- Nordmarker A, Norlander T, Archer T. The effects of alcohol intake and induced frustration upon art vandalism. Social Behavior and Personality. 2000;28:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Norlander T, Nordmarker A, Archer T. Effects of alcohol and frustration on experimental graffiti. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 1998;39:201–207. doi: 10.1111/1467-9450.00080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Ogle RL, Miller WR. The effects of alcohol intoxication and gender on the social information processing of hostile provocations involving male and female provocateurs. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:54–62. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orwin RG. A fail-safe N for effect size in meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Statistics. 1983:157–159. [Google Scholar]

- Parker RN, Auerhahn K. Alcohol, drugs, and violence. Annual Review of Sociology. 1998;24:291–311. [Google Scholar]

- Pumphrey-Gordon JE, Gross AM. Alcohol consumption and females’ recognition inresponse to date rape risk: The role of sex-related alcohol expectancies. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:475–485. [Google Scholar]

- Rennison CM, Melde C. Gender and robbery: A national test. Deviant Behavior. 2014;35:275–296. [Google Scholar]

- *.Rohsenow DJ, Bachorowski JA. Effects of alcohol and expectancies on verbal aggression in men and women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1984;93:418–432. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.93.4.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R. Meta-analytic procedures for social research. Vol. 6. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia: Its prized and dangerous effects. American Psychologist. 1990;45:921–933. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stith SM, Smith DB, Penn CE, Ward DB, Tritt D. Intimate partner physical abuse perpetration and victimization risk factors: A meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2004;10:65–98. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SP. Aggressive behavior and physiological arousal as a function of provocation and the tendency to inhibit aggression. Journal of Personality. 1967;35:297–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1967.tb01430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SP, Leonard KE. Alcohol and human physical aggression. Aggression: Theoretical and Empirical Reviews. 1983;2:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SP, Schmutte GT, Leonard KE, Cranston JW. The effects of alcohol and extreme provocation on the use of a highly noxious electric shock. Motivation and Emotion. 1979;3(1):73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi JT, Quigley BM. Limitations of laboratory paradigms for studying aggression. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 1996;1:163–177. [Google Scholar]

- *.Testa M, Crane CA, Quigley BM, Levitt A, Leonard KE. Effects of administered alcohol on intimate partner interactions in a conflict resolution paradigm. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75:249–258. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Fillmore MT, Norris J, Abbey A, Curtin JJ, Leonard KE, … VanZile-Tamsen C. Understanding alcohol expectancy effects: Revisiting the placebo condition. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30(2):339–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00039.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Derrick JL. A daily process examination of the temporal association between alcohol use and verbal and physical aggression in community couples. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28:127–138. doi: 10.1037/a0032988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]