Abstract

Cognitive function is impaired in patients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, even in their prodromal stages. Specifically, the assessment of cognitive abilities related to daily-living functioning, or functional capacity, is important to predict long-term outcome. In this study, we sought to determine the validity of the Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale (SCoRS) Japanese version, an interview-based measure of cognition relevant to functional capacity (i.e. co-primary measure). For this purpose, we examined the relationship of SCoRS scores with performance on the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS) Japanese version, a standard neuropsychological test battery, and the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS), an interview-based social function scale.

Subjects for this study (n = 294) included 38 patients with first episode schizophrenia (FES), 135 with chronic schizophrenia (CS), 102 with at-risk mental state (ARMS) and 19 with other psychiatric disorders with psychosis. SCoRS scores showed a significant relationship with SOFAS scores for the entire subjects. Also, performance on the BACS was significantly correlated with SCoRS scores. These associations were also noted within each diagnosis (FES, CS, ARMS).

These results indicate the utility of SCoRS as a measure of functional capacity that is associated both with cognitive function and real-world functional outcome in subjects with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders.

Abbreviations: SCoRS, Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale; BACS, Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia; JART, Japanese Adult Reading Test; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; ARMS, at risk mental state; CAARMS, Comprehensive Assessment of at risk mental state; SOFAS, Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale

Keywords: SCoRS, Schizophrenia, At risk mental state, Cognition, Co-primary measure, BACS, SOFAS

1. Introduction

Cognitive function is impaired in most patients with schizophrenia; multiple cognitive domains are affected, for example, verbal learning memory, attention, working memory, executive functions, motor speed. (Heinrichs and Zakzanis, 1998, Saykin et al., 1991). The magnitude of cognitive impairment is suggested to predict daily living abilities and real world functioning to a greater extent than do positive symptoms (Green et al., 2000). Therefore, it is desirable to use valid and feasible measures of cognition and daily living skills to facilitate the development of novel therapies and improve the quality of clinical practice.

Performance-based measures are traditionally used to assess cognitive impairments in schizophrenia (Chapman and Chapman, 1973). For example, the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS) (Keefe et al., 2004) and the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB) (Marder and Fenton, 2004, Nuechterlein et al., 2004) represent such measures. On the other hand, it is suggested that clinicians may not be able to sufficiently evaluate changes of daily living capacity by performance-based measures alone (Buchanan et al., 2005). This argument may be related to several reasons, including poor observance by agitated subjects of procedures for completing cognitive tasks, practice effect, and so on. Interview-based assessments, on the other hand, may be devoid of these disadvantages associated with performance-based measures.

The Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale (SCoRS) was one of the assessment tools recommended by the MATRICS initiative to evaluate functional capacity of patients. Several studies report the validity and reliability of SCoRS in other countries (Chia et al., 2010, Green et al., 2011, Harvey et al., 2011, Kaneda et al., 2011, Keefe et al., 2015, Keefe et al., 2006, Vita et al., 2013). The SCoRS was developed to measure cognitive functions through questions about cognitions related to daily life events (Keefe et al., 2006). It consists of 20 items, for example, “Remembering names of people you know or meet?”, “Handling changes in your daily routine?”, “Concentrating well enough to read a newspaper or a book?”. Each item is rated on a scale ranging from 1 to 4 with higher scores reflecting a greater degree of impairment. Every item is given anchor points based on the degree of their daily problems.

In spite of previous studies reporting its utility as a functional capacity measure, discussed above, there is little information on whether the SCoRS would provide a valid assessment tool also in subjects with first or recent onset schizophrenia, or prodromal state of the illness. In view of the need for early intervention into cognitive deficits of schizophrenia, we considered it is important to determine whether the SCoRS would elicit sufficient validity in patients with various stages of the illness.

Therefore, the purposes of this paper were; (1) to examine the structure of the SCoRS, (2) to determine its relationships with cognitive function, as measured by neuropsychological assessment, and social function (interview-based), and (3) to determine if such associations depend on the stage of schizophrenia.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

We collected the data from 3 hospitals (275 from Toyama University Hospital, 17 from Tokyo University Hospital and 2 from Kamiichi General Hospital) from 2007 to 2016. Participants were in- or outpatients who had psychotic symptoms. Diagnoses were made according to ICD-10 by well experienced psychiatrists. Most of them (N = 173) met the criteria of schizophrenia (F20). First episode schizophrenia (FES, n = 38, male/female = 20/18; mean [SD] age = 26.4 [8.2] years) was defined if duration of illness was < 1 year. The rest of patients with duration of illness ≥ 1 year was categorized as chronic schizophrenia (CS, n = 135, male/female = 77/58; mean [SD] age = 31.1 [8.5] years).

Diagnosis of at risk mental state (ARMS) was based on the Comprehensive Assessment of at risk mental state (CAARMS) by a method as we conducted in past studies (Higuchi et al., 2014, Higuchi et al., 2013) (n = 102, male/female = 64/38; mean [SD] age = 19.4 [3.9] years). Others (OTHERS, n = 19, male/female = 11/8; mean [SD] age = 26.1 [10.3] years) consisted of; schizotypal disorder (F21, n = 3), delusional disorder (F22, n = 2), acute and transient psychotic disorder (F23, n = 4), neurosis (F4, n = 9), and pervasive developmental disorders (F8, n = 1). None had a lifetime history of serious head trauma, neurological illness, serious medical or surgical illness, substance abuse and intellectual impairment (IQ < 70). IQ was estimated by using the Japanese Adult Reading Test (JART) (Matsuoka et al., 2006).

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethical committee on each institute. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. If they were < 20 years old, informed consent was also obtained from their family.

2.2. Clinical and neuropsychological assessments

The SCoRS was performed according to the procedure by Keefe et al., 2006. It consists of 20 questionnaires, and each item is rated on a scale ranging from 1 to 4 with higher scores reflecting a greater degree of impairment. Two sources of information were used: an interview with a patient (SCoRS for patient) and an interview with caregiver(s) (SCoRS for caregiver). Caregivers included family members (mother 74.4%, father 10.9%, parents 3.1%, partner 6.2%, grandparents 2.3% and sibling 2.3%) or medical staff (0.8%). Raters (interviewers) generated a “Global Rating Score” reflecting overall impairment by incorporating all information, including ratings obtained from the patient and caregiver. The Global Rating Score was scored from 1 to 10, with higher ratings indicating severe impairment.

Neuropsychological performance, measured by the Japanese version of the BACS (Kaneda et al., 2007), was evaluated by experienced psychiatrists or psychologists. It uses the following assessments in the respective targeted domains: list learning (verbal memory), digit sequencing task (working memory), token motor task (motor function), category fluency and letter fluency (verbal fluency), symbol coding (attention and processing speed), and the Tower of London test (executive function) (Keefe et al., 2004). Composite scores were calculated based on the average z-score of each item (Kaneda et al., 2013).

Severity of psychotic symptoms was determined by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (Kay et al., 1987). We also used the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) (Goldman et al., 1992). It is a rating scale used to subjectively assess the social and occupational functioning due to medical conditions. This scale was first presented by Goldman et al. (1992) in the paper ‘Revising Axis V for DSM-IV: A review of measures of social functioning’ and later included in the DSM-IV, section ‘Criteria Sets and Axes Provided for Further Study’. The scale is based on a continuum of functioning, ranging from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better functioning (Samara et al., 2014). Because the start of ratings with the SOFAS was delayed, there are less data from this scale compared with those from the rest of clinical measures.

Raters (psychiatrist, psychologist) were not informed of subjects' profiles and diagnosis.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20 (SPSS Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Group differences for demographic variables, SCoRS, SOFAS and BACS were examined using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Difference between male and female were calculated by Fisher's exact test. Correlational analysis was performed by Pearson's rank correlation test. We also conducted factor analysis to examine the factor structure of obtained data. Cronbach's alpha was used to indicate reliability. Significance was considered when the p-value was < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of patients

Demographic data of patients are shown on Table 1. Sex ratio did not differ significantly among groups. ARMS patients were younger than other groups. ARMS and OTHERS groups received less dose antipsychotic drugs compared to schizophrenia patients. Schizophrenia patients received larger dose antipsychotics than did ARMS and OTHERS groups. JART scores for FES group were slightly lower than those for other groups. Severity of psychotic symptoms, as measured by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), did not significantly differ between 4 groups.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data.

| All subject | ARMS | First episode schizophrenia | Chronic schizophrenia | Other psychiatric illness | ANOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 294) | (n = 102) | (n = 38) | (n = 135) | (n = 19) | ||

| Gender (male/female) | 172/122 | 64/38 | 20/18 | 77/58 | 11/8 | χ2 = 1.22, p = 0.74 |

| Age (years old) | 26.1(9.0) | 19.4(3.9) | 26.4(8.2) | 31.1(8.5) | 26.1(10.3) | F(3, 293) = 54.7, p < 0.001** |

| Duration of illness (years) | 5.2(5.6) | – | 0.3(0.3) | 7.0(5.7) | – | – |

| Antipsychotics dose (mg/day, risperidone equivalent) | 2.8(4.0) | 0.5(1.2) | 3.4(3.3) | 4.6(4.7) | 0.6(1.1) | F(3, 293) = 29.3, p < 0.001** |

| JART | 99.9(9.7) | 99.2(9.2) | 96.3(10.3) | 101.5(9.6) | 99.1(9.1) | F(3, 266) = 3.14, p = 0.026* |

| PANSS total score | 58.2(24.1) | 56.6(22.7) | 63.5(22.9) | 58.9(24.4) | 51.7(29.0) | F(3, 270) = 0.39, p = 0.76 |

| PANSS positive scale | 12.4(6.1) | 11.1(5.0) | 14.0(6.0) | 13.0(6.5) | 11.8(7.6) | F(3, 270) = 1.63, p = 0.18 |

| PANSS negative scale | 16.2(7.8) | 16.3(7.7) | 17.2(7.7) | 16.4(7.6) | 13.0(7.9) | F(3, 270) = 0.28, p = 0.83 |

ARMS; at-risk mental state, JART; Japanese Adult Reading Test, PANSS; Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

Average (SD), *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

3.2. Factor analysis

According to Keefe et al. (2015), we performed factor analysis to investigate the construction of the SCoRS Japanese version. Exploratory factor analysis of our dataset (N = 294) indicated that a single factor was the best structure, consistent with Keefe et al. (2015) using the original English version. Cronbach's alpha in this study was 0.917.

3.3. SCoRS

SCoRS Global Rating scores (range 1–10) are shown on Table 2. They greatly varied according to diagnosis. Scores of chronic schizophrenia patients were higher than those of other diagnosis groups, suggesting worse daily functioning. Ratings for ARMS and OTHERS groups were not so high unlike those for patients with schizophrenia.

Table 2.

Comparisons of SCoRS, BACS and SOFAS data.

| All subjects | ARMS | First episode schizophrenia | Chronic schizophrenia | Other psychiatric illnesses | ANOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCoRS Global Rating Score | 4.00(1.92) | 3.66(1.90) | 3.81(1.8) | 4.38(1.93) | 3.45(1.58) | F(3, 293) = 4.82, p = 0.003** |

| SOFAS | 52.6(13.1) | 53.3(8.6) | 44.4(11.7) | 54.9(14.4) | 42.5(16.8) | F(3, 117) = 2.05, p = 0.11 |

| BACS composite score (z-score) | − 0.90(0.99) | − 0.48(0.94) | − 1.41(0.79) | − 1.10(0.97) | − 0.68(0.81) | F(3, 293) = 13.36, p < 0.001** |

ARMS; at risk mental state, SCoRS; Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale, SOFAS; Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale, BACS; Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia.

Average (SD), *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

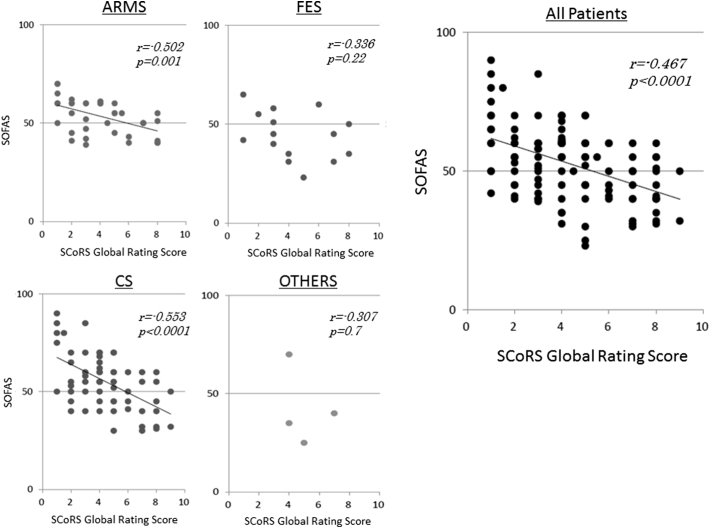

3.4. Relationship between SCoRS and SOFAS scores

We could obtain SOFAS data from 39 ARMS, 15 FES, 60 CS and 4 OTHERS patients. There was no significant difference in SOFAS scores between four groups. The relationships between ratings on the SOFAS and SCoRS are shown on Fig. 1. ARMS and CS groups, as well as entire patients, showed significant correlations between the two measures.

Fig. 1.

Scatterplots and least squares regression lines depicting the relationship between SCoRS Global Rating Score (interviewer) and SOFAS score. ARMS; at-risk mental state, FES; first episode schizophrenia, CS; chronic schizophrenia, OTHERS; other psychiatric disorders with psychosis.

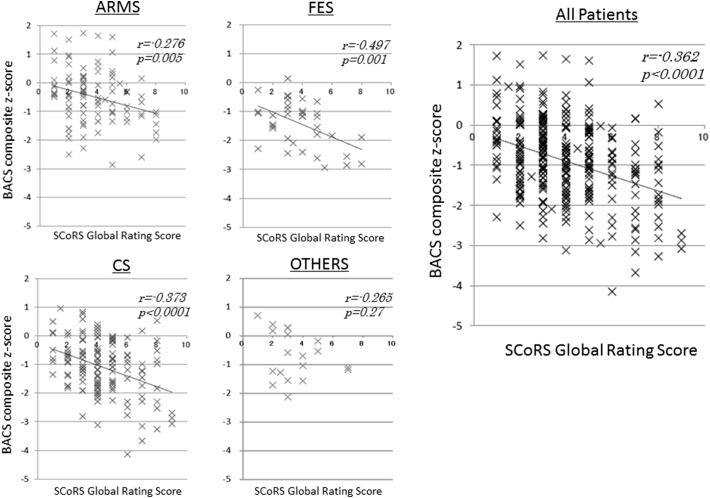

3.5. Relationship between SCoRS and BACS

Composite z-scores of the BACS are shown on Table 2. They remarkably varied according to diagnosis. Thus, patients with FES showed the worst z-score (− 1.41), while performances by ARMS and OTHERS groups were less affected.

We also examined the correlations of SCoRS Global Rating scores with BACS composite z-scores. As shown in Fig. 2, they were significantly correlated across diagnoses.

Fig. 2.

Scatterplots and least squares regression lines depicting the relationship between SCoRS Global Rating Score (interviewer) and BACS composite z-score. ARMS; at-risk mental state, FES; first episode schizophrenia, CS; chronic schizophrenia, OTHERS; other psychiatric disorders with psychosis.

4. Discussion

The SCoRS was developed to measure current cognitive status and changes related to daily activity skills in patients with schizophrenia. The large number of subjects (n = 294), recruited from three institutions, indicates reliability of this study. Specifically, we included subjects with ARMS for evaluation, in addition to patients with established schizophrenia. Results from exploratory factor analysis suggest that a single factor was the best structure the SCoRS Japanese version, consistent with the case for the English version (Keefe et al., 2015). Cronbach's alpha in this study is equivalent to that for the English version (Keefe et al., 2015).

We found validity of the SCoRS as a measure of cognition linked to daily activity skills. To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the relationship between cognition close to real-world activities and social function in subjects with ARMS, FES, and CS, both separately and collectively.

It is important to determine appropriate tools for evaluating functional outcome for each of the clinical stages of psychosis. The positive correlation between scores on the SOFAS and SCoRS in ARMS subjects indicates the validity of the latter scale in evaluating functional status in people vulnerable to developing psychiatric conditions. The lack of such relationship in patients with FES or OTHERS may be due to the small sample numbers for which SOFAS data were available. Another reason for the absence of significant correlation in OTHERS group may be the heterogeneity of subjects. In fact, this group consisted of several psychotic conditions, e.g. delusional disorder, acute and transient psychotic disorders, and so on. Further study is warranted to see the validity of SCoRS in individual schizophrenia-spectrum disorders.

The implication that SCoRS effectively evaluates functional outcome is consistent with previous studies (Chia et al., 2010, Keefe et al., 2006, Vita et al., 2013) using the Global Assessment Functioning (GAF) (Lehman, 1983), WHO-quality of life scale (The WHOQOL group, 1998), Health and the Nation Outcome Scale (HoNOS) (Wing et al., 1998), Independent Living Skills Inventory (ILSI) (Menditto et al., 1999), and University of California Performance-based Skills Assessment (UPSA) (Patterson et al., 2001) as a comparative measure. Results of the current study add to the concept that the SCoRS provides a valid measure of functional outcome in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, including high-risk states.

We observed a strong correlation between SCoRS Global Rating Score (interview-based measure) and BACS composite score (performance-based measure) for the entire patients, as well as patients with schizophrenia (both FES and CS) and subjects with ARMS. These results suggest the SCoRS is able to predict cognitive performance in schizophrenia-spectrum patients across stages. Previous studies report performance on the BACS (Chia et al., 2010, Kaneda et al., 2011, Keefe et al., 2006) or Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB) (Keefe et al., 2015) was significantly correlated with ratings with the SCoRS. Specifically, Vita et al. (2013) found correlations between the interview's Global Rating Score on the SCoRS vs. processing speed, working memory and executive function (Vita et al., 2013). Overall, the results obtained in this study add to the concept that data from interview-based measures of cognition well reflect cognitive impairment as assessed by their performance-based counterparts.

Some issues related to the results of the SCoRS and BACS are worth mentioning. First, as shown in Table 2, FES patients performed worse on the BACS than did ARMS subjects. On the other hand, the difference in the ratings on the SCoRS between the two groups was not significant. It might reflect the way that the two groups express concerns about their cognitive problems, although ratings on the SCoRS rely mainly on objective assessment by raters. Second, there were slight differences in BACS and SCoRS scores between FES and CS in an opposite way, both of which did not reach significant level. The reason why the discrepancy occurred is not clear, but may be related to the natures of cognitive functions measured by BACS and SCoRS. It is possible that CS patients generally received pharmacological and psychosocial treatments for a long time, which may be particularly advantageous to performance on the BACS.

The limitations of this study include the relatively small number of patients for whom SOFAS data were available. Also, more definite conclusions could have been obtained with a larger number of FES and OTHERS subjects.

In conclusion, the results of this study indicate strong correlations between SCoRS ratings vs. SOFAS and BACS scores. These observations suggest the ability of the SCoRS to measure cognition associated with daily living skills in various stages of schizophrenia and related disorders.

Role of funding source

Study sponsors played no role in study design; data collection, analysis, or interpretation; manuscript preparation of decision to submit the paper for publication.

Contributors

Drs. Higuchi and Sumiyoshi conceptualized and designed the study. Drs. Sumiyoshi, organized the collaborative team of institutions. Dr. Higuchi conducted the analysis, interpreted the data and prepare the initial draft. Dr. Sumiyoshi revised the draft critically for important intellectual contents. Drs. Suzuki, Kasai, Seo, Suga and Takahashi assisted with data collection. Drs. Seo, Nishiyama and Komori executed psychological tests. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (No. 16K10205, 26461739, 26461761, P16H06395, 16H06399 and 16K21720) from the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science, and Intramural Research Grant (27-1) for Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders of NCNP. This study was also supported in part by the Brain Mapping by Integrated Neurotechnologies for Disease Studies (Brain/MINDS) from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, AMED (16dm0207004h0003). We would to thank Akihito Okabe (Kamiichi General Hospital) for recruitment of patients. Special thanks to Yumiko Nishikawa, Daiki Sasabayashi and Mihoko Nakamura (Department of Neuropsychiatry, University of Toyama) for their assistant for evaluation of symptoms. Also, appreciation should be given to Youichiro Takayanagi for invaluable advice about statistical methods and cooperation about recruitment of patients.

References

- Buchanan R.W., Davis M., Goff D. A summary of the FDA-NIMH-MATRICS workshop on clinical trial design for neurocognitive drugs for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2005;31:5–19. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman L.J., Chapman J.P. Problems in the measurement of cognitive deficit. Psychol. Bull. 1973;79:380–385. doi: 10.1037/h0034541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia M.Y., Chan W.Y., Chua K.Y. The Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale: validation of an interview-based assessment of cognitive functioning in Asian patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178:33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman H.H., Skodol A.E., Lave T.R. Revising axis V for DSM-IV: a review of measures of social functioning. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1992;149:1148–1156. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.9.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M.F., Kern R.S., Braff D.L., Mintz J. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the “right stuff”? Schizophr. Bull. 2000;26:119–136. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M.F., Schooler N.R., Kern R.S. Evaluation of functionally meaningful measures for clinical trials of cognition enhancement in schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2011;168:400–407. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10030414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey P.D., Ogasa M., Cucchiaro J., Loebel A., Keefe R.S. Performance and interview-based assessments of cognitive change in a randomized, double-blind comparison of lurasidone vs. ziprasidone. Schizophr. Res. 2011;127:188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs R.W., Zakzanis K.K. Neurocognitive deficit in schizophrenia: a quantitative review of the evidence. Neuropsychology. 1998;12:426–445. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.12.3.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi Y., Sumiyoshi T., Seo T. Mismatch negativity and cognitive performance for the prediction of psychosis in subjects with at-risk mental state. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi Y., Seo T., Miyanishi T. Mismatch negativity and p3a/reorienting complex in subjects with schizophrenia or at-risk mental state. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2014;8:172. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneda Y., Sumiyoshi T., Keefe R. Brief assessment of cognition in schizophrenia: validation of the Japanese version. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2007;61:602–609. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneda Y., Ueoka Y., Sumiyoshi T. Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale Japanese version (SCoRS-J) as a co-primary measure assessing cognitive function in schizophrenia. Nihon Shinkei Seishin Yakurigaku Zasshi. 2011;31:259–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneda Y., Sumiyoshi T., Nakagome K. Evaluation of cognitive functions in a normal population in Japan using the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia Japanese version (BACS-J) Seishin Igaku. 2013;55(2):167–175. [Google Scholar]

- Kay S.R., Fiszbein A., Opler L.A. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 1987;13:261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe R.S., Goldberg T.E., Harvey P.D. The Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia: reliability, sensitivity, and comparison with a standard neurocognitive battery. Schizophr. Res. 2004;68:283–297. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe R.S., Poe M., Walker T.M., Kang J.W., Harvey P.D. The Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale: an interview-based assessment and its relationship to cognition, real-world functioning, and functional capacity. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2006;163:426–432. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe R.S., Davis V.G., Spagnola N.B. Reliability, validity and treatment sensitivity of the Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;25:176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman A.F. The effects of psychiatric symptoms on quality of life assessments among the chronic mentally ill. Eval Program Plann. 1983;6:143–151. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(83)90028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder S.R., Fenton W. Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia: NIMH MATRICS initiative to support the development of agents for improving cognition in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2004;72:5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka K., Uno M., Kasai K., Koyama K., Kim Y. Estimation of premorbid IQ in individuals with Alzheimer's disease using Japanese ideographic script (Kanji) compound words: Japanese version of National Adult Reading Test. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2006;60:332–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2006.01510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menditto A.A., Wallace C.J., Liberman R.P. Functional assessment of independent living skills. Psychiatr Rehabilitation Skills. 1999;3:200–219. [Google Scholar]

- Nuechterlein K.H., Barch D.M., Gold J.M. Identification of separable cognitive factors in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2004;72:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson T.L., Goldman S., McKibbin C.L., Hughs T., Jeste D.V. UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment: development of a new measure of everyday functioning for severely mentally ill adults. Schizophr. Bull. 2001;27:235–245. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samara M.T., Engel R.R., Millier A. Equipercentile linking of scales measuring functioning and symptoms: examining the GAF, SOFAS, CGI-S, and PANSS. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24:1767–1772. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saykin A.J., Gur R.C., Gur R.E. Neuropsychological function in schizophrenia. Selective impairment in memory and learning. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1991;48:618–624. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810310036007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The WHOQOL Group Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28:551–558. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vita A., Deste G., Barlati S. Interview-based assessment of cognition in schizophrenia: applicability of the Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale (SCoRS) in different phases of illness and settings of care. Schizophr. Res. 2013;146:217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing J.K., Beevor A.S., Curtis R.H. Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS). Research and development. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1998;172:11–18. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]