Abstract

Introduction

Parent/caregivers' inability to recognize the importance of baby teeth has been associated with inadequate self-management of children's oral health (i.e. lower likelihood of preventive dental visits) which may result in dental caries and the need for more expensive caries-related restorative treatment under general anesthesia. Health behavior theories aid researchers in understanding the impact and effectiveness of interventions on changing health behaviors and health outcomes. One example is the Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation (CSM) which focuses on understanding an individual's illness perception (i.e. illness and treatment representations), and subsequently has been used to develop behavioral interventions to change inaccurate perceptions and describe the processes involved in behavior change.

Methods

We present two examples of randomized clinical trials that are currently testing oral health behavioral interventions to change parental illness perception and increase dental utilization for young children disproportionately impacted by dental caries in elementary schools and pediatric primary care settings. Additionally, we compared empiric data regarding parent/caregiver perception of the chronic nature of dental caries (captured by the illness perception questionnaire revised for dental: IPQ-RD constructs: identity, consequences, control, timeline, illness coherence, emotional representations) between parent/caregivers who did and did not believe baby teeth were important.

Results

Caregivers who believed that baby teeth don't matter had significantly (P<0.05) less accurate perception in the majority of the IPQ-RD constructs (except timeline construct) compared to caregivers who believed baby teeth do matter.

Conclusion

These findings support our CSM-based behavioral interventions to modify caregiver caries perception, and improve dental utilization for young children.

Keywords: dental caries, children, parents, illness perception, dental care, baby teeth

1. Introduction

Despite recent declining trends in dental caries (tooth decay, cavities) in the primary teeth (baby teeth) of young children, the disease still affects 37% of two to eight year olds [1]. Dental caries is disproportionately borne by Hispanic (46%) and non-Hispanic Black (44%) compared to non-Hispanic White (31%) children aged 2 to 8 years [1]. Unlike other medical illnesses, childhood dental caries is entirely preventable with adequate self-management strategies by parent/caregivers that include regular preventive dental care and appropriate oral hygiene habits [2]. Among Medicaid-enrolled children 1 to 20 years of age, approximately $450 million in additional expenditures in surgical care was spent on preventable dental conditions mostly due to early childhood caries (ECC) [3].

A widely held belief by parents/caregivers is that dental caries is an acute disease to be responded to only when there is pain or visible cavities [4]. However, untreated caries in baby teeth are a strong predictor of future caries in permanent teeth indicating the chronic nature of the disease [5]. Previous literature has also indicated that failure to recognize the importance of baby teeth among caregivers is associated with adverse health habits and outcomes for their children such as less frequent tooth brushing and a lower likelihood of having preventive dental visits [6]; increased likelihood of ECC [7]; and having caries-related restorative treatment under general anesthesia [8]. More recently, we found that only 19% of parent/caregivers sought follow-up dental care for their children after being given a restorative referral during a dental screening in elementary schools [9].

To address the issues specified above, in this paper, we will first describe the Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation (CSM) theoretical approach for modifying parents' perception of children's dental caries. Second, we present two examples of ongoing randomized clinical trials that are testing oral health behavioral interventions to modify parent/caregiver illness perception of children's dental caries. Both clinical trials focus on the chronic nature of the disease and the importance of baby teeth using the CSM framework. Through modifying parent/caregivers' representations of their child's dental disease we hope to align parental perception of the importance of primary dentition and their care.

2. CSM Theoretical Framework for Changing Perception of Dental Caries

One approach used in self-management of chronic medical conditions is the Common Sense Model of Self-Regulation (CSM) [10]. The CSM is a multi-level framework which describes the process of an individual's efforts to alter health behavior, i.e. their self-regulatory behavior [10]. Self-regulation is often linked to social cognitive constructs such as self-efficacy [11], perceived control [12], attitudes and beliefs [13], and behavioral intention [13]. However, there are conceptual differences between self-regulation and other social cognitive constructs. While social cognitive constructs are significantly associated with actual behavior, only self-regulation includes a combination of motivating variables (e.g. attitudes, intentions) and action variables (e.g. plans, efficacy), both of which are required to change behavior [14].

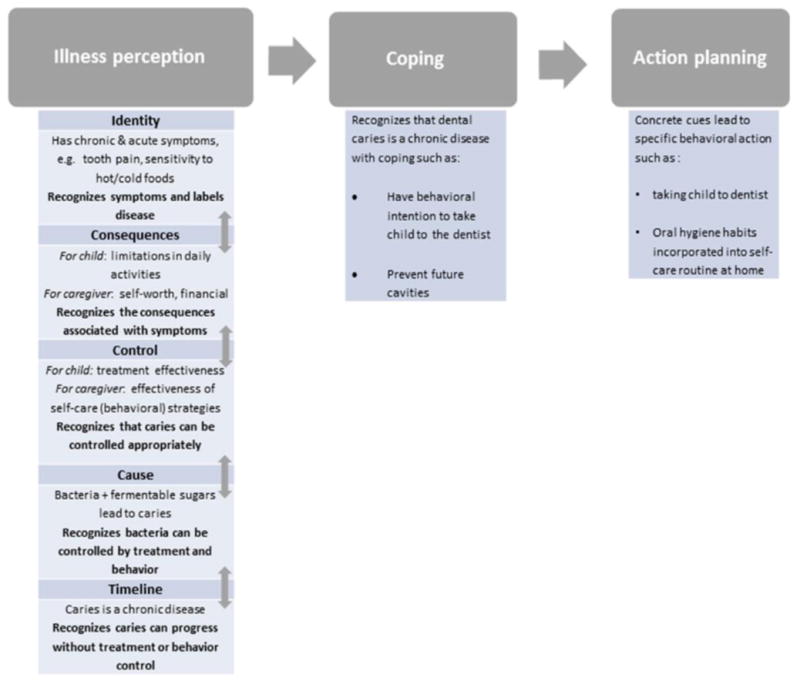

The CSM framework outlines the process of how an individual's illness perception (i.e. cognitive and emotional representations of their illness) influences their coping and action planning to manage their disease. Simply put, the framework can be used to examine the congruence between an individual's representations of their illness (and actions taken to manage that illness) and representations of the treatment and/or health behaviors as necessities. Illness (or symptom management) representations can be defined as the perception of illness vs. no illness or the association of being sick with being symptomatic [14]. The latter is particularly true in the case of dental caries in children, as the disease is often recognized only if symptomatic pain is present. Treatment and health behavior representations can be described as the perception that treatment is necessary and/or effective, i.e. the outcome of the treatment matches the individual's subjective and objective indicators [15]. Incongruence between an individual's perception, regarding either the treatment or their health/illness, can potentially lead to a lack of adherence to the prescribed treatment or behavior change [15]. Five key constructs guiding the illness representation/perception are: Identity, the patient/caregiver labeling of disease and its symptoms; Cause, the individual's perception of the underlying cause of their illness; Cons equence, the belief about the impact of the illness physically and socially; Timeline, the personal beliefs about the illness being acute, chronic, or cyclical in nature; and Cure or controllability, the belief whether the illness can be cured or kept under control by the individual or others. The revised Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ-R) [16] developed from the original IPQ [17] has been used to identify the five dimensions of illness representation together with additional dimensions such as illnes s c oherence, whether the individual has a clear understanding of the illness, and emotional representations, the individual's emotional response to the illness. Figure 1 illustrates the use of the CSM theoretical framework for childhood dental caries. The framework indicates that caregivers with an accurate perception can clearly relate the five CSM constructs to each other and link to symptoms (e.g. the child has no tooth pain, but parent understands that bacteria causes caries, and that there are serious consequences for child and self, which can be controlled through treatment or self-care strategies, so that caries does not progress to the permanent teeth). With such a chronic, organized representation of the illness, caregivers develop coping skills (i.e. intention to take the child to the dentist) with a subsequent concrete action plan (i.e. regular dental visits) for their child's illness.

Figure 1. Theoretical Framework for Dental Caries Using the Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation.

Much of the research using the CSM has described patients' representation of illnesses and treatments and appraisal of somatic changes on care-seeking behaviors among chronic illness patients, while few studies have used the CSM to influence the self-regulatory process of chronic disease management [18]. The CSM provides an approach that can be used to develop behavioral interventions that describe not only the effectiveness of treatments but also the mechanisms for change, or processes that play a role in changing behavior [14]. Further, this framework provides an opportunity to replace an individual's acute, symptom-focused illness model with a chronic, asymptomatic model [14,17]. The incorporation of a feedback loop combines top-down and bottom-up processes in which top-down mechanisms guide specific behavioral actions and bottom-up effects are the change in illness and treatment representations due to long-term self-management [18]. Thus, the CSM provides a framework for the development of theory-based behavior change interventions that lead to the effective translation of intentions and motivation into actual behavior [19]. The CSM has been used to develop interventions for diabetes [18], asthma [18], and attendance for cardiac rehabilitation [20]. For example, a CSM theory-based letter and information leaflet have been successfully shown to improve cardiac rehabilitation attendance [20].

3. Materials and Methods

In this section, we describe the development of the illness perception questionnaire revised for dental (IPQ-RD) and the two ongoing clinical trials using the CSM theoretical framework to test behavioral interventions. Further, we provide preliminary data from one of the trials that supports the use of the CSM framework.

3.1 Development of the Illness Perception Questionnaire Revised for Dental (IPQ-RD)

Our research team modified the IPQ-R for use in parent/caregivers of children with dental caries (IPQ-RD) and psychometrically tested the instrument showing excellent validity and reliability [21]. The IPQ-RD is comprised of 33 items and ten CSM constructs: identity, consequences (child, caregiver), control (child, caregiver), timeline (cyclical, chronic), illness coherence, cause, and emotional representations.

For our CSM-based interventions, the measurement of illness perception via the IPQ-RD enables an investigation of possible mediation through this intermediary outcome. Partitioning the IPQ-RD responses into its conceptual components, representing a set of potential mediators, further allows a determination of the particular dimensions of illness perception through which the intervention affects dental outcomes. Behavioral intention is also measured which provides a possible ‘second stage’ mediator linking illness perception to dental care utilization. We previously developed newer statistical methods that are being used in these two trials to overcome some of the challenges of such mediation analyses, allowing, for example, multiple stages of mediators [22], different types (i.e. continuous, discrete, and zero-inflated) of mediators/outcomes [23,24], and sensitivity analyses that examine the impact of departures from the important ‘sequential ignorability’ (roughly, ‘no unmeasured confounders’) assumption needed for causally-interpretable mediation effect estimates [25]. Besides shedding light on mechanisms and validating or refuting underlying behavioral theory, we expect that the determination of important mediating variables through such causal mediation analysis can inform the development of more effective and streamlined future behavioral interventions.

3.2 Example 1: Development of the Family Access to a Dentist Study (FADS)

The FADS study, funded by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR: U01 DE024167-01), aims to improve the outcome of the dental referral process (i.e. increase dental utilization) for children identified with dental disease during a school screening. The rationale is that only 19% of caregivers in a low-income community sought follow-up care for their child after receiving a standard referral letter (commonly used by other U.S. schools) identifying dental caries in their child [9]. The goal of the FADS randomized clinical trial is to test a new referral letter and dental information guide (DIG), compared to a standard letter, to improve caregivers' illness perception of their child's dental caries and increase utilization for children (5 to 10 years old) with caries-related restorative needs. The new referral letter and DIG was developed using constructs from the CSM framework (i.e. cognitive representations: identity, consequences, cause, control, timeline, illness coherence; and emotional representations) in order to deliver relevant information to move the caregiver from an “acute” to a “chronic” model of understanding the child's cavities. A secondary study aim is to assess the extent to which the effect of the new vs. standard intervention on dental utilization is mediated through changes in illness perception (as measured by the IPQ-RD) and behavioral intention. We hypothesized that child dental care utilization will increase among caregivers who receive the CSM-based interventions (i.e. the new referral letter and DIG) versus the standard referral letter. Our secondary hypothesis was that the increase in child dental care utilization would be through the primary mediating effect of changes in caregiver illness representation/perception by influencing behavioral intention, after controlling for relevant child and caregiver socio-demographic characteristics. The design and details of this study has been previously reported [26].

All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center in Cleveland, Ohio. Informed consent was obtained from all parent participants and assent from children seven years and older. This study has been registered with clinical trials.gov (NCT02395120).

While the FADS study is currently ongoing in several school districts in Ohio and Washington, we conducted preliminary analyses using baseline data which support the main focus of this paper – the importance of improving caregivers' perception of baby teeth.

Parent/caregivers were asked to complete a baseline IPQ-RD and a caregiver questionnaire. The IPQ-RD measured caregivers' cognitive representations with the following constructs (and items): identity (5 sub-items), consequences-child (7 items), consequences-caregiver (5 items), control-child (4 items), control-caregiver (4 items), timeline-chronic (2 items), timeline-cyclical (2 items), and illness coherence (2 items); emotional representations was assessed with 4 items. The IPQ-RD is described in more detail elsewhere [21]. The caregiver questionnaire included questions on caregivers' socio-demographic characteristics, oral health beliefs, behavioral intention, self-efficacy, literacy, caregiver dental history, dental anxiety and fear, perceived stress, child's dental access and disposition. We considered caregivers' responses to the following statement “Cavities in baby teeth don't matter since they fall out anyway” with a five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” and then further collapsed participants into those who believed baby teeth don't matter (“strongly agree”, “agree”, and “neutral”) and those who believed baby teeth do matter (“disagree”, “strongly disagree”). We then looked at the differences between these two groups of caregivers as follows: presence of cavities in children were assessed by dentists using the International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS); caregiver questionnaire responses for child's dental access (“Has your child ever been seen by a dentist”), behavioral intention (“I want to take my child to the dentist”, “I plan to take my child to the dentist”); and caregiver IPQ-RD survey for accurate responses in overall IPQ-RD and each of the IPQ-RD constructs.

Statistical analysis included chi-square tests for child and behavioral intention variables. The mean proportion of accurate responses for overall IPQ-RD and each of the individual IPQ-RD constructs was compared between the two groups using the Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney test. These findings are reported in the proceeding Results section.

3.3 Example 2: Development of the Pediatricians Against Cavities in Children's Teeth (PACT) study

3.3.1. Study design

The PACT study is one of nine consortium grants funded by the NIDCR in 2015 (UH2 DE025487-01) to reduce oral health disparities in children. This five-year multi-level cluster randomized clinical trial aims to improve dental care access and reduce cavities among Medicaid-enrolled children 3 to 6 year old attending well-child visits. The rationale for this study is that 74% of Medicaid-enrolled young children received well-child visits [27] while only 24% received a preventive dental visit [28] despite anticipatory guidance for dental visits starting from age 1 [2]. Our premise is that oral health facts delivered by pediatric primary care providers where the messenger may be key to changing parental perceptions to seek dental care is likely to be persuasive, as suggested by a vaccine promotion messaging study [29]. In the PACT study, we take a different approach to changing parental perception. The multi-level interventions are at the provider (pediatricians, nurse practitioner) and practice levels and subsequently the provider delivers the oral health facts to the parent. The PACT study is organized in two phases: pilot (UH2 phase) and the main study (UH3 phase). This hybrid effectiveness-implementation study is in its initial stages of pilot testing the educational curriculum for providers and testing the procedures in two practices. The main clinical trial in 18 practices will start in September 2017.

The overall primary objective of the study is to test provider- (behavioral) and practice- (implementation) level interventions in primary care settings to increase dental utilization among 3-6 year-old Medicaid-enrolled children attending well-child visits (WCV). We hypothesize that parent/caregivers receiving consistent reinforcing oral health facts from primary care providers (i.e. pediatricians and nurse practitioners) will have increased dental utilization for their child compared to those parents not received these oral health facts in primary care settings.

All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center in Cleveland, Ohio. Informed consent will be obtained from all participants.

3.3.2. Summary of the intervention

The main PACT study is a 3-arm cluster randomized clinical trial involving 18 primary-care practices. Arm 1 (6 practices) will receive both the provider + practice level interventions, Arm 2 (6 practices) will receive only the provider level intervention, Arm 3 (control: 6 practices) will follow the usual care for oral health assessment recommended by American Association of Pediatrics (AAP) guidelines.

The provider-level intervention is CSM-based education and skills training for pediatricians and nurse practitioners to communicate core oral health facts to parents/caregivers and provide them with a prescription to take their child to the dentist together with a list of Medicaid-accepting dentists in the area. The CSM framework is used at the provider level to impart key oral health facts to parents/caregivers with the goal of improving their cognitive and emotional representations of dental caries for a clear understanding of the chronic disease process of caries. The core oral health facts include the following: (1) importance of baby teeth; (2) chronic nature of dental caries, i.e. bacteria in baby teeth can attack newly erupting permanent teeth and cause cavities; (3) encourage annual dental visits by providing adequate self-management strategies for parent/caregivers, e.g. giving them a prescription to go to the dentist along with a list of dentists who will accept Medicaid in the area.

The practice level intervention is enhancements to the EMR system to document oral health encounters, and practice facilitators to conduct audits and deliver rapid-cycle feedback to providers. Intervention at this level will promote the adoption of systematic oral health documentation in the EMR and provider follow-up with parent/caregivers at subsequent well-child visits regarding whether they took their child to the dentist. These will also be part of quality improvement initiatives. Similar to the FADS study, we will use mediation analysis (as described previously) using the IPQ-RD and self-efficacy to investigate the mechanism through which the CSM-based behavioral intervention affects dental care utilization.

3.3.3. Randomization

We will use cluster randomization with practices as the clusters. Practices will be: 1) assigned a score based on the matching variables (% Medicaid-enrolled patients, ratio of patients to provider, and county: Cuyahoga vs. other), 2) ordered, and then 3) grouped based on their score. A lower score will indicate characteristics expected to be associated with lower dental usage. Each group of matched practices will be randomly assigned to 1 of 3 arms.

3.3.4. Pilot phase

The pilot phase is currently being conducted to assess the feasibility of and refine the provider- and practice-level interventions. These assessments are focused on logistical issues related to recruitment at the primary care practices, and refinement of study materials/questionnaires and the provider oral health curriculum (i.e. didactic education and skills training).

4. Results

Both the FADS and the PACT study utilize the CSM framework to change dental caries perception of parent/caregivers of young children, in particular to understand the importance of baby teeth. While the FADS study is in the second year of recruitment and data collection, we report below the baseline data from the first year of recruitment and data collection. The PACT study is in an initial pilot phase.

4.1 FADS study

The sample included a total of 911 caregivers of K-4th grade children in Ohio and Washington (mean age: 33.5 ±8.0 years; 56% African-American, 29% Caucasian, 15% other; 14% Hispanic; 36% married; 47% ≤ high school) who were recruited during the 2015-2016 school year. Of the 911 caregivers, 851 caregivers remained in the study (60 dropped out or children transferred out of school); and out of the 851 caregivers remaining, a total of 736 (86%) completed the baseline IPQ-RD.

Preliminary results (Table 1) indicated that a total of 140 caregivers believed baby teeth don't matter (19%) and 594 believed they do matter (81%). Caregivers who believed that baby teeth don't matter had significantly (P<0.05) greater mean proportion of children with cavities, lower proportion whose child had ever been to a dentist, lower behavioral intention to take the child to the dentist, and less accurate perception in overall IPQ-RD and most of the IPQ-RD constructs (all except timeline-chronic and timeline-cyclical) compared to caregivers who believed baby teeth do matter.

Table 1. Child outcomes, behavioral intention, and illness perception between caregivers who believed baby teeth don't and do matter in Ohio and Washington: 2015.

| Baby teeth don't matter (N = 140) |

Baby teeth do matter (N = 594) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Child Outcomes | % (N) | % (N) | P value |

|

| |||

| Dental caries | |||

| Present | 60.0 (84) | 46.6 (277) | <0.001* |

| Not present | 40.0 (56) | 53.4 (317) | |

| Seen by a dentist | |||

| Yes | 89.1 (122) | 93.9 (554) | 0.045* |

| No | 10.9 (15) | 6.1 (36) | |

|

| |||

| Caregiver Behavioral Intention | |||

|

| |||

| Want to take my child to the dentist | |||

| Yes | 80.6 (112) | 89.5 (529) | 0.004* |

| No | 19.4 (27) | 10.5 (62) | |

| Plan to take my child to the dentist | |||

| Yes | 82.7 (115) | 91.5 (540) | 0.002* |

| No | 17.3 (24) | 8.5 (50) | |

|

| |||

| Caregiver Illness Perception (IPQ-RD) | Mean Proportion of accurate responses ± SD | Mean Proportion of accurate responses ± SD | P value |

|

| |||

| Overall IPQ-RD (35 items) | 45 ± 23.5 | 54.9 ± 19.5 | <0.001* |

| Identity (5 items) | 61.7 ± 41.3 | 83.8 ± 29.1 | <0.001* |

| Consequences – child (7 items) | 24 ± 31 | 32.9 ± 35.5 | 0.008* |

| Consequences – caregiver (5 items) | 19.1 ± 29.2 | 27.5 ± 32.5 | 0.004* |

| Control – child (4 items) | 64.3 ± 35.6 | 73.2 ± 31.2 | 0.012* |

| Control – caregiver (4 items) | 76.9 ± 34.9 | 85.5 ± 26.9 | 0.013* |

| Timeline – chronic (2 items) | 34.5 ± 41 | 37.3 ± 40.8 | 0.436 |

| Timeline – cyclical (2 items) | 39.4 ± 43.3 | 44.3 ± 43.2 | 0.234 |

| Illness coherence (2 items) | 67.4 ± 43.7 | 77.8 ± 37.4 | 0.012* |

| Emotional representations (4 items) | 38.5 ± 36.7 | 45.5 ± 33.6 | 0.02* |

p<0.05

5. Discussion

The preliminary results from the FADS study, although a cross-sectional analysis, lend support to our CSM theoretical framework (Figure 1) highlighting that an inaccurate perception of dental caries among caregivers can lead to poorer coping (i.e. lower behavioral intention to take their child to the dentist) and action planning (i.e. lower proportion whose child had ever been to the dentist). Further, our findings substantiate the importance of using the CSM framework to change perception using a theory-based behavioral intervention. In the medical literature, behavioral interventions developed to change illness perception have been instrumental in increasing cardiac rehabilitation rates [30] and medication adherence for type 2 diabetes [31]. The preliminary results from the FADS study also strengthen our hypothesis regarding the role of caregiver illness perception and behavioral intention as mediators in the relationship between the CSM-based interventions and child dental care utilization and provide evidence to expect the same associations in the PACT study.

In particular, the FADS study data indicates that caregivers' belief about baby teeth was significantly associated with most IPQ-RD constructs, caregivers' behavioral intentions, and child outcomes (presence of dental caries and ever been seen by a dentist). Compared to caregivers who believe that baby teeth matter (i.e. accurate perception), a greater mean proportion of caregivers who did not recognize that baby teeth matter (i.e. inaccurate perception) had children who had never been seen by a dentist (10.9% vs. 6.1%) and with dental caries (60% vs. 46.6%). These findings lend support to previous research demonstrating the association between caregivers' inaccurate perceptions about primary teeth and their child's poor oral health outcomes (e.g. lower likelihood of preventive dental visits [6] and greater likelihood of ECC [7]). There was a significant association between caregivers' accurate perception about the importance of baby teeth and an accurate illness perception of dental caries based on the IPQ-RD constructs. A higher mean proportion of caregivers with an accurate perception about baby teeth had accurate perceptions about the: consequences of dental caries on their child's overall health (i.e. consequences-child) and their own controllability of their child's caries (i.e. control-caregiver). These results bolster findings from prior studies, most of which had relatively small sample sizes and were conducted using qualitative methods, e.g. semi-structured interviews [8] or focus groups [6,32].

The timeline IPQ-RD construct was the only non-significant variable: there was a similarly low proportion (i.e. <40%) of caregivers with an accurate perception of the timeline of dental caries in both groups (i.e. those who believed and did not believe baby teeth matter). These results indicate that both groups of parents had inaccurate perceptions about the acute, chronic, and predictable nature of dental caries. Our findings are congruent with both a previous case-control study that did not find either of the timeline-constructs (using the IPQ-RD) to be a significant predictor of ECC [33] and with the lay public's long-standing belief that baby teeth are unimportant because they fall out. The lack of a significant association between caregivers' perceptions further confirms the notion that caregivers do not believe baby teeth are important because they do not understand the disease process of dental caries (i.e. the progression of caries from primary to permanent teeth). Thus, our CSM-based interventions for parents/caregivers and providers have implications for both the FADS and PACT studies in changing this common misconception about baby teeth.

Our expectation that the PACT study will be effective in changing caregivers' illness perceptions is also based on previous research examining physician-patient communication and interaction. Our intervention incorporates elements of interventions that focus on patient education and physician communication skills with the goal of changing caregiver illness perception and helping caregivers develop action plans to increase their child's dental utilization. By seeking to first understand their patient's perceptions of dental caries, pediatricians can better provide information about prevention or self-management of dental caries that is tailored to each caregiver (and their child, i.e. the patient) while developing an action plan with the caregiver. Interventions to improve health-related outcomes have highlighted physicians' roles in helping patients to develop accurate illness perceptions, increase behavioral intention [29], and develop concrete action plans [34], which will result in improved treatment adherence of chronic illnesses [35] such as asthma [36], hypertension [37], cardiac rehabilitation [30,38] and rehabilitation for chronic back pain [39]. Furthermore, who delivers the message as well as the information presented in the message impact its effectiveness, as has been demonstrated in the cases of hypertensive patients' views on antihypertensive drugs [40] and parents' intent to vaccinate their child against measles-mumps-rubella [29], respectively.

Conclusion

In this paper, we present an innovative approach to changing parental illness perception of dental caries using a CSM-based theoretical framework. We also provide data from one of our ongoing clinical trials indicating that changing parental perception is fundamentally important to view caries as a chronic disease rather than an acute symptomatic disease to improve dental outcomes. Further, we explain that our two clinical trials which test CSM-based behavioral interventions on different levels have the capability to reach a wider audience of parents, providers, and primary care practices to change perceptions about baby teeth and increase dental utilization for young low-income children, and subsequently increase oral health equity across all groups.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge all the collaborating dentists who were instrumental in giving input on the study: Peter Milgrom, DDS, Joana Cunha-Cruz, DDS, MPH, PhD, Gerald Ferretti, DDS, MS, MPH, and Masahiro Heima, DMD, PhD. The authors wish to thank all study staff, study dentist examiners, study participants, participating elementary schools, primary care practices, and pediatric providers. The authors also acknowledge Yiying, Liu, MPH for assistance with statistical analysis.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), specifically: the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research [grant numbers U01 DE024167-01, UH2 DE025487-01], and the Clinical and Translational Sciences Collaborative of Cleveland, funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the NIH [grant number UL1 TR000439]. The funders were not involved in any of the following activities: study design; data collection, analysis, and interpretation; writing of the report; and the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dye BA, Thornton-Evans G, Li X, Iafolla TJ. Dental caries and sealant prevalence in children and adolescents in the United States, 2011-2012. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2015. NCHS data brief, no 191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on periodicity of examination, preventive dental services, anticipatory guidance/counseling, and oral treatment for infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatr Dent. 2013;35(5):E148–E156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruen BK, Steinmetz E, Bysshe T, Glassman P, Ku L. Potentially preventable dental care in operating rooms for children enrolled in Medicaid. J Am Dent Assoc. 2016;147(9):702–708. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2016.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hooley M, Skouteris H, Boganin C, Satur J, Kilpatrick N. Parental influence and the development of dental caries in children aged 0-6 years: a systematic review of the literature. J Dent. 2012;40:873–885. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Motohashi M, Yamada H, Genkai F, Kato H, Imai T, Sato S, et al. Employing dmft score as a risk predictor for caries development in the permanent teeth in Japanese primary school girls. J Oral Sci. 2006;48(4):233–237. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.48.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riedy CA, Weinstein P, Milgrom P, Bruss M. An ethnographic study for understanding children's oral health in a multicultural community. Int Dent J. 2001;51:305–312. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-595x.2001.tb00843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schroth RJ, Brothwell DJ, Moffatt MEK. Caregiver knowledge and attitudes of preschool oral health and early childhood caries (ECC) Int J Circumpolar Health. 2007;66(2):153–167. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v66i2.18247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amin MS, Harrison RL. A conceptual model of parental behavior change following a child's dental general anesthesia procedure. Pediatr Dent. 2007;29(4):278–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nelson S, Mandelaris J, Ferretti G, Heima M, Spiekerman C, Milgrom P. School screening and parental reminders in increasing dental care for children in need: a retrospective cohort study. J Public Health Dent. 2012;72:45–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00282.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leventhal H, Brissette I, Leventhal EA. The common-sense model of self-regulation of health and illness. In: Cameron LD, Leventhal H, editors. The self-regulation of health and illness behavior. London: Routledge; 2003. pp. 42–65. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bandura A. Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychol Health. 1995;13:623–649. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ajzen I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2002;32:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Predicting and changing behavior: the reasoned action approach. New York: Psychology Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leventhal H, Weinman J, Leventhal EA, Phillips LA. Health psychology: the search for pathways between behavior and health. Ann Rev Psychol. 2008;59:477–505. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horne R. Treatment perceptions and self-regulation. In: Cameron LD, Leventhal H, editors. The self-regulation of health and illness behavior. London: Routledge; 2003. pp. 138–153. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moss-Morris R, Weinman J, Petrie KJ, Horne R, Cameron LD, Buick D. The Revised Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ-R) Psychol Health. 2002;17(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinman J, Petrie KJ, Moss-Morris R, Horne R. The Illness Perception Questionnaire: a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of illness. Psychol Health. 1996;11:431–445. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McAndrew LM, Musumeci-Szabo TJ, Mora PA, Vileikyte L, Burns D, Halm EA, et al. Using the common sense model to design interventions for the prevention and management of chronic illness threats: from description to process. Br J Health Psychol. 2008;13(2):195–204. doi: 10.1348/135910708X295604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hagger MS. Self-regulation: an important construct in health psychology research and practice. Health Psychol Rev. 2010;4(2):57–65. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mosleh SM, Kiger A, Campbell N. Improving uptake of cardiac rehabilitation: using theoretical modelling to design an intervention. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2009;8:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nelson S, Slusar MB, Albert JM, Liu Y, Riedy CA. Psychometric properties of a caregiver illness perception measure for caries in children under 6 years old. J Psychosom Res. 2016;81:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Albert JM, Nelson S. Generalized causal mediation analysis. Biometrics. 2011;67:1028–1038. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2010.01547.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang W, Albert JM. Estimation of mediation effects for zero-inflated regression models. Stat Med. 2012;31:3118–3132. doi: 10.1002/sim.5380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang W, Nelson S, Albert JM. Estimation of causal mediation effects for a dichotomous outcome in multiple-mediator models using the mediation formula. Stat Med. 2013;32:4211–4228. doi: 10.1002/sim.5830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Albert JM, Wang W. Sensitivity analyses for parametric causal mediation effect estimation. Biostatistics. 2015;16:339–351. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxu048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nelson S, Riedy C, Albert JA, Lee W, Slusar MB, Curtan S, et al. Family Access to a Dentist Study (FADS): a multi-center randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;45:177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bouchery E. Utilization of well-child care among Medicaid-enrolled children. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2012. MAX Medicaid policy brief, no. 10. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bouchery E. Utilization of dental services among Medicaid-enrolled children. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2013;3(3):E1–E14. doi: 10.5600/mmrr.003.03.b04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nyhan B, Reifler J, Richey S, Freed GL. Effective messages in vaccine promotion: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2014;133(4):e835–e842. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mosleh SM, Bond CM, Lee AJ, Kiger A, Campbell NC. Effectiveness of theory-based invitations to improve attendance at cardiac rehabilitation: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014;13(3):201–10. doi: 10.1177/1474515113491348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davies MJ, Heller S, Skinner TC, Campbell MJ, Carey ME, Cradock S, Dallosso HM, Daly H, Doherty Y, Eaton S, Fox C, Oliver L, Rantell K, Rayman G, Khunti K. Effectiveness of the diabetes education and self-management for ongoing and newly diagnosed (DESMOND) programme for people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;336(7642):491–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39474.922025.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hilton IV, Stephen S, Barker JC, Weintraub JA. Cultural factors and children's oral health care: a qualitative study of carers of young children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35:429–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2006.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Slusar MB, Nelson S. Caregiver illness perception of their child's early childhood caries. Pediatr Dent. 2016;38(5):217–223. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Ridder DTD, Theunissen NCM, van Dulmen SM. Does training general practitioners to elicit patients' illness representations and action plans influence their communication as a whole? Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66:327–336. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leventhal H, Diefenbach M, Leventhal EA. Illness cognition: using common sense to understand treatment adherence and affect cognition interactions. Cognit Ther Res. 1992;16(2):143–163. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clark NM, Gong M, Schork MA, Kaciroti N, Evans D, Roloff D, Hurwitz M, Maiman LA, Mellins RB. Long-term effects of asthma education for physicians on patient satisfaction and use of health services. Eur Respir J. 2000;16:15–21. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.16a04.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Theunissen NCM, de Ridder DTD, Bensing JM, Rutten GEHM. Manipulation of patient-provider interaction: discussing illness representations or action plans concerning adherence. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;51:247–258. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petrie KJ, Cameron LD, Ellis CJ, Buick D, Weinman J. Changing illness perceptions after myocardial infarction: an early intervention randomized controlled trial. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:580–586. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200207000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glattacker M, Heyduck K, Meffert C. Illness beliefs, treatment beliefs and information needs as starting points for patient information—evaluation of an intervention for patients with chronic back pain. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86:378–389. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lisper L, Isacson D, Sjoden P, Bingefors K. Medicated hypertensive patients' views and experience of information and communication concerning antihypertensive drugs. Patient Educ Couns. 1997;32:147–155. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(97)00033-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]