Abstract

The cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) is an essential regulator of lipid and glucose metabolism that plays a critical role in energy homeostasis. The impact of diet on PKA signaling has not been defined, although perturbations in individual PKA subunits are associated with changes in adiposity, physical activity, and energy intake in mice and humans. We hypothesized that a high fat diet (HFD) would elicit peripheral and central alterations in the PKA system that would differ depending on length of exposure to HFD; these differences could protect against or promote diet-induced obesity (DIO).

12-week old C57Bl/6J mice were randomly assigned to a regular diet or HFD and weighed weekly throughout the feeding studies (4 days, 14 weeks; respectively), and at sacrifice. PKA activity and subunit expression were measured in liver, gonadal adipose tissue (AT), and brain.

Acute HFD-feeding suppressed basal hepatic PKA activity. In contrast, hepatic and hypothalamic PKA activities were significantly increased after chronic HFD-feeding. Changes in AT were more subtle, and overall, altered PKA regulation in response to chronic HFD exposure was more profound in female mice.

The suppression of hepatic PKA activity after 4 day HFD-feeding was indicative of a protective peripheral effect against obesity in the context of overnutrition. In response to chronic HFD-feeding, and with the development of DIO, dysregulated hepatic and hypothalamic PKA signaling was a signature of obesity that is likely to promote further metabolic dysfunction in mice.

Keywords: PKA, diet-induced obesity, liver, hypothalamus, adipose tissue

Introduction

High worldwide obesity rates have resulted from the combined effects of environmental and lifestyle factors including food composition and availability, portion sizes, work and commuting habits and lagging physical activity levels (Hruby and Hu 2015). The well-documented physiologic effects associated with excess adiposity include dysregulation of glucose and lipid metabolism, and altered endocrine and neuroendocrine profiles that can interfere with regulatory feedback mechanisms. Central to these negative physiologic changes is the cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) pathway, an essential regulator of glucose and lipid metabolism that mediates the effects of catecholamines and other hormones such as insulin and glucagon.

The PKA holoenzyme is a tetramer consisting of 2 regulatory and 2 catalytic subunits. Four regulatory (RIα, RIβ, RIIα, RIIβ) and 2 catalytic (Cα, Cβ) subunit isoforms are present in human and mice that are expressed in a tissue-specific manner and have differing affinities for cAMP; α subunits are ubiquitously expressed, while β subunits have a more restrictive expression pattern. Regulatory subunit RIα is the primary regulator of PKA in most tissues; it can compensate for disruptions in other regulatory subunits by decreasing protein turnover rate (Amieux, et al. 1997; Amieux and McKnight 2002; Cazabat, et al. 2014). Because of its high affinity for cAMP, increased RIα can thus lead to increased basal PKA activity. While various cellular stimuli can affect PKA RNA levels, regulation of PKA expression is ultimately thought to be controlled at the protein level.

Direct regulation of PKA signaling by nutrients or chronic overnutrition has not been thoroughly explored. Expression of PKA RIIβ and PKA activity were decreased in visceral AT from otherwise healthy obese individuals compared to lean individuals (Mantovani, et al. 2009). Individuals that harbor mutations and other defects in PKA signaling molecules develop corticotropin-independent Cushing Syndrome (CS). For example, mutations of the PRKAR1A gene (that codes for RIα subunit) cause primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease (PPNAD) (Horvath, et al. 2010; Kirschner, et al. 2000) and mutations of GNAS1 (that codes for the stimulatory subunit alpha or GSα) cause primary bimorphic adrenocortical disease (Carney, et al. 2011) in the context of McCune Albright syndrome. GNAS1 mutations are also infrequently found in primary macronodular adrenocortical hyperplasia (Hsiao, et al. 2009). Visceral AT from patients with these forms of CS (Horvath et al. 2010; Kirschner et al. 2000) exhibited alterations in PKA expression, that were associated with varying degrees of obesity (London, et al. 2014b). In different settings, the other subunits may also compensate for RIα haploinsufficiency (Greene, et al. 2008; Nesterova, et al. 2008).

Dysregulated PKA activity in mouse models of PKA deficiency is associated with changes in adiposity, energy balance, and response to obesogenic diet. The most extensively studied model is the diet-induced obesity (DIO)-resistant PKA RIIβ KO mouse that has elevated energy expenditure and basal lipolysis (Cummings, et al. 1996; Planas, et al. 1999), improved insulin (Schreyer, et al. 2001) and leptin (Yang and McKnight 2015) sensitivities and altered locomotor activity that is sex-specific (Nolan, et al. 2004). The PKA Cβ KO mouse is DIO-resistant and females display drastically reduced fat mass compared to their male counterparts, yet is phenotypically distinct from the RIIβ KO mouse (Enns, et al. 2009). We recently identified DIO-resistance in the RIIα KO mouse and reported a more pronounced phenotype among females (London, et al. 2014a). Interestingly, metabolic phenotypes vary considerably among RIIα KO, RIIβ KO and Cβ KO genotypes confirming specific roles and interactions for the PKA subunits in different tissues. For example, RIIβ KO and Cβ KO mice are mildly hyperphagic, unlike RIIα KO mice (Cummings et al. 1996; Enns et al. 2009; London et al. 2014a). Metabolic phenotypes of RIIβ KO and Cβ KO mice differ between sexes, and in RIIα KO mice, the observed metabolic and behavioral phenotype is more evident in female compared to male suggesting the involvement of sex hormones and/or other sex-specific factors with respect to PKA regulation of energy metabolism and homeostasis.

To test the hypothesis that chronic high fat diet (HFD) exposure would lead to dysregulation of peripheral and central PKA signaling, we gave wild-type C57Bl/6J mice ad libitum access to HFD or control (regular) diet (CD). We focused on liver and adipose tissue for our peripheral investigations because of their acute and longer-term regulatory roles in glucose and lipid metabolism and homeostasis. Further, potential feedback mechanisms linking hepatic- and adipose tissue-derived factors to CNS, and particularly hypothalamus, in the control of energy intake and appetite linked peripheral and central regulation for our purposes. As expected, long-term HFD caused increased body weight, fat mass and glucose intolerance compared to weight-matched littermates fed a CD. We found that acute HFD access led to suppressed hepatic PKA activity which is metabolically protective (London et al. 2014a). Conversely, chronic HFD access and subsequent DIO caused increased PKA activity in liver and hypothalamus that likely potentiate the deleterious physiologic effects of excess adiposity, contribute to glucose intolerance, and act as a committed step to promote development of obesity, an observation not previously made. These data suggest that there are specific interactions between diet and the PKA system even in wild-type, normal mice.

Methods

Mice and diets

Twelve-week old male and female C57Bl/6J littermates were maintained on a regular diet (control diet [CD]) from weaning at approximately 21 days. At 11 to 12 weeks of age, mice were randomly assigned to either the CD or HFD group and provided ad libitum access to water and their respective diet for 14 weeks (n=7–9/group per sex) or 4 days (n=6–8/group). Same-sex mice were group housed within treatment group 2–4 mice per cage and maintained on a 12h light:dark cycle at 22–23°C. Mice were originally obtained from Jackson Labs and were then inbred and maintained at the NIH 10A animal facility for more than 5 years prior to these studies.

The CD, NIH-31 Open Formula (Harlan Teklad, Indianapolis IN), has an energy density of 3.0 kcal/g with 24%, 14% and 62% of the total energy derived from protein, fat and carbohydrate. The HFD used was high fat soft pellet chow (F3282; Bio-Serv, Frenchtown NJ) that has an energy density of 5.5kcal/g; 21%, 36% and 36% of energy was derived from protein, fat and carbohydrate.

Weight gain, adiposity and glucose tolerance

Mice were weighed at baseline and then weekly at 0900h during the experimental period and at time of sacrifice. Body composition was measured at the conclusion of the 14 week study by EchoMRI-100H body composition analyzer for mice (EchoMRI, Houston TX). Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test was performed at week 14 of the long-term diet study. Mice were overnight fasted (16h) prior to IP glucose injection (2g/kg) (Sigma Aldrich; St Louis, MO). Blood glucose was measured in 3μL of tail blood at baseline, 15, 30, 60 and 120 minutes with a Contour glucometer and test strips (Bayer Healthcare LLC; Tarrytown, NY).

Tissue and serum collection

Mice were killed by slow replacement of air with CO2 followed by cervical dislocation and exsanguination. Dissected tissues were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored (−80°C). Tissues aliquoted for gene expression studies were first preserved in RNAlater (Qiagen, Waltham MA). For immunofluorescence experiments, mice were killed and immediately perfused with ice cold 4% PFA. Whole brains were extracted, post-fixed for 24 hours in 4% PFA and then transferred to 70% ethanol prior to paraffin embedding.

Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR assay

Total RNA was extracted using RNEasy Mini and Lipid Mini kits (Qiagen) for liver and AT, respectively, and included on-column DNase digestion with DNase I (Invitrogen, Grand Island NY). cDNA was synthesized from 250 ng (AT) and 500 ng (liver) total RNA with SuperScript III First Strand Synthesis Supermix for qRT-PCR (Invitrogen). Relative mRNA expression was quantified by qRT-PCR (ViAA7; Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad CA) by calculating the delta CT and determining fold-change as the 2-ΔΔCT value (Livak and Schmittgen 2001). Previously tested and optimized qPCR primers were used (Suppl Table 1). Actb1 was the housekeeper gene for liver and the averaged value for Actb1, Rplp0, B2m and Hprt was used for AT. PCR products run on 2% agarose gels confirmed the presence of a single band at the expected amplicon size as an additional quality control check subsequent to melt curve analysis.

Western blot

AT, liver and brain tissues were homogenized in ice-cold TPER lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham MA) with 1:100 protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (EMD Biosciences, La Jolla CA) using a BulletBlender and RNase-free beads (Next Advance, Averill Park NY). Total protein was quantified by BCA assay (Pierce, Rockford IL). Western blots were performed by loading 15–30μg total protein per well (depending on tissue type) and probing with commercially available antibodies (Suppl Table 2). Membranes were visualized on a ChemiDoc imaging system and densitometry analysis was performed to determine relative expression (ImageLab 4.0, BioRad; Hercules CA).

Immunohistochemistry

Slides prepared from 20μm thick coronal brain sections were probed with phosphorylated CREB (pCREB) (s133) (Cell Signaling, Danvers MA) and then Alexa Fluor 594 secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotech, Dallas TX), and counterstained with Dapi nuclear stain (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham MA). Microphotographs of hypothalamus were taken using uniform exposure settings for all sections with an Axioplan microscope and analyzed using Zen2012 software (Zeiss, Germany).

PKA activity

Liver, AT and brain samples were homogenized with a Bullet Blender Tissue Homogenizer and lysis beads (Next Advance, Averill Park NY) in ice-cold buffer (10mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1mM EDTA, 1 mM dithriothreitol, and protease inhibitor cocktail I (EMD Biosciences, La Jolla, CA). Hypothalamus was dissected from whole brain under a dissecting microscope (Nikon SMZ 1500, Japan). Cell lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 x g and 4°C for 10m. Total protein concentrations were determined by BCA assay (Pierce, Rockford IL). PKA enzymatic activity was measured using a previously described method that employs P32-labeled ATP and kemptide substrate with or without added cAMP (5μM) (Nesterova, et al. 1996). Calculated PKA/kinase activities were normalized to total protein concentration.

Statistical Analysis

Data were described using simple descriptive statistics, which are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM); relative changes are described as percent of each respective comparison. All data distributions were assessed for approximate normality with the Shapiro Wilk test. Continuous data (mRNA and protein expression, PKA activity, BW, IPGTT) were compared between two independent groups using t-tests. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc.; Cary, NC) and graphed with GraphPad Prism 7 (La Jolla, CA).

All mouse procedures were approved by and conducted in accordance with the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Results

Chronic HFD-feeding produced expected increases in body weight, fat mass and blood glucose levels in mice

Chronic HFD-feeding significantly increased weight gain in mice (Suppl Figs 1A, 1B). Female and male mice weighed 65% and 53% more after 14wk ad lib HFD access compared to CD-fed mice, respectively. HFD access for 4 days did not cause significant weight gain in female or male mice. 14wk HFD-feeding caused more than 4-fold and 3-fold increases in total fat mass in female and male mice, respectively (Suppl Figs 1C, 1D).

After 14 weeks of HFD access, non-fasted blood glucose was higher in male and female mice (p<0.05) compared to CD-fed littermates (data not shown). Glucose tolerance, tested after 14 week HFD-feeding was significantly impaired in both sexes (Suppl Figs 2A, 2B).

Hepatic PKA activity and expression are differentially regulated by acute and chronic HFD-feeding

We first examined the effects of chronic HFD-feeding on the regulation of PKA enzymatic activity and subunit expression and observed a more profound effect in female mice (see Suppl Figure 3 for male mouse data). We therefore carried out the subsequent analyses in tissues from female mice.

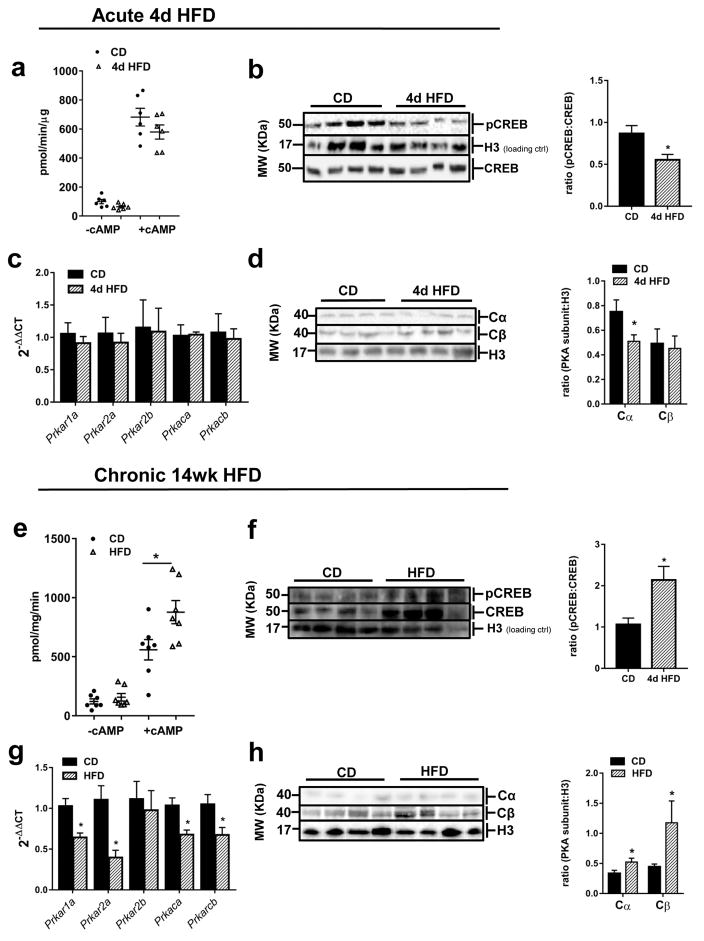

Acute (4 day) access to HFD tended to cause a decrease in basal hepatic PKA activity (Fig 1A) (p=0.06), and significantly decreased hepatic phosphorylated cAMP-response element binding protein (pCREB) (S133) levels (Fig 1B) (p<0.03). In liver, acute HFD-feeding did not alter the regulation of PKA subunits at the mRNA level (Fig 1C), but protein expression of the major PKA catalytic subunit, Cα, was decreased (Fig 1D) (p<0.05).

Figure 1.

Hepatic PKA enzymatic activity is differentially regulated by acute and chronic HFD intake and overall dysregulation of PKA system is observed after chronic HFD intake in mice. (a) Basal and cAMP-stimulated (5 μM cAMP) PKA activities after 4d CD- or HFD-feeding, n=6–8/group. (b) Representative western blot and quantification of pCREB in liver nuclear fraction after 4d CD- or HFD-feeding; ratio of pCREB to CREB was first normalized to the loading control, H3; membrane image was cut and rejoined to remove the central lane with molecular weight ladder. (c) Hepatic mRNA expression of PKA subunits after 4d CD or HFD exposure, n=6–8/group. (d) Representative western blot and quantification of PKA catalytic subunits α and β in liver after 4d CD- or HFD-feeding, n=6–8/group. (e) Basal and cAMP-stimulated (5 μM cAMP) PKA activities after 14 wk CD- HFD-feeding (n=6–8/group). (f) Representative western blot and quantification of pCREB in liver nuclear fraction after 14 week HFD-feeding; membrane image was cut and rejoined to remove a single poorly resolved lane. (g) mRNA expression of PKA subunits in liver from mice after 14 week CD- or HFD-feeding, n=6–8/group. (h) Representative western blot and quantification of PKA catalytic subunits α and β in liver after 14 wk CD- or HFD-feeding, n=6/group. All values are mean ±SEM; *, p < 0.05. Western blot and PKA activity experiments were repeated two to three times each. Abbreviations: pCREB, phospho-cAMP response element binding protein (S133); CREB, cAMP response element binding protein; H3, histone 3 protein; Cα, PKA catalytic subunit α protein; Cβ, PKA catalytic subunit β protein.

Chronic (14wk) HFD-feeding caused a significant increase in cAMP-stimulated hepatic PKA activity (p<0.02) (Fig 1E). Phosphorylated CREB levels were higher in liver of mice after chronic HFD-feeding (Fig 1F) (p<0.03), and overall CREB expression appeared to be upregulated by chronic HFD. Chronic HFD-feeding led to the overall downregulation of PKA subunit mRNA (1G). mRNA levels of Prkar1a, Prkar2a, Prkaca and Prkacb were suppressed by 36% (p<0.003), 60% (p<0.003), 32% (p<0.006) and 32% (p<0.03) compared to levels of the control group (Fig 1G). In line with the observed increase in hepatic PKA enzymatic activity, PKA catalytic subunits Cα and Cβ protein expression was increased in HFD-fed mice (Fig 1H) (p<0.05). The discrepancy between RNA and protein was not surprising as PKA subunit expression has been shown to be regulated primarily by changes in protein stability (McKnight, et al. 1998).

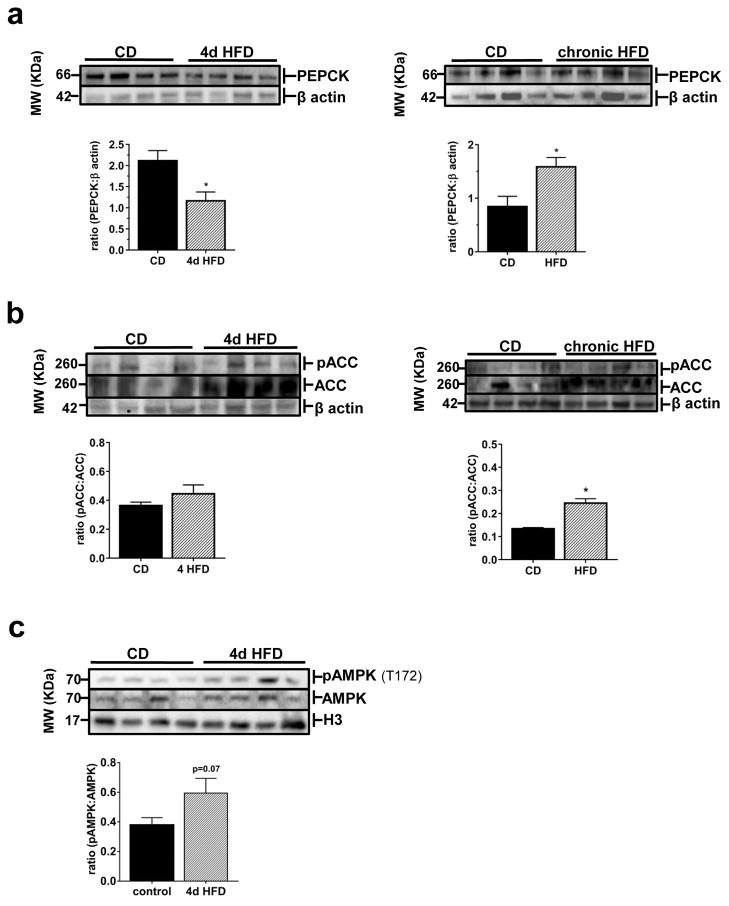

To confirm the downstream effects of the changes observed in hepatic PKA activity we examined expression and phosphorylation status of downstream PKA targets with important roles in regulating energy homeostasis. After 4d HFD-feeding, expression of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) was lower than that of CD-fed mice, while chronic HFD exposure caused increased PEPCK expression (Fig 2A). After acute 4d HFD, phosphorylated acetyl co-A carboxylase (pACC) levels didn’t differ from control levels, but total ACC expression tended to be higher in the 4d HFD mice (Fig 2B). pACC was significantly higher after chronic HFD-feeding (Fig 2B); total ACC levels also appeared to be increased. In an attempt to understand the mechanism behind decreased basal hepatic PKA activity and concurrent enhancement of ACC, we examined levels of phosphorylated AMPK at tyrosine 172 (T-172) levels after 4d HFD (Fig 2C). pAMPK (T-172) levels tended to be increased after acute exposure to HFD but were not significantly higher (Fig 2C).

Figure 2.

Phosphorylation and expression of downstream PKA targets in liver are impacted by altered PKA activity resulting from acute and chronic HFD feeding in mice. (a) Representative western blots and quantification of PEPCK in liver of mice after 4d or 14 wk access to CD or HFD. (b) Representative western blots and quantification of pACC and ACC in liver of mice after 4d or 14 wk access to CD or HFD; membrane image was cut and rejoined to remove a single poorly resolved lane. (c) Representative western blots and quantification of pAMPK (T-172) in liver of mice after 4d CD or HFD-feeding. All values are mean ±SEM;*, p < 0.05. Western blot experiments were each repeated three or more times from a pool of 6–8 samples/group.

Chronic HFD-feeding increases hypothalamic PKA activity and alters cAMP signaling in response to fasted and fed states

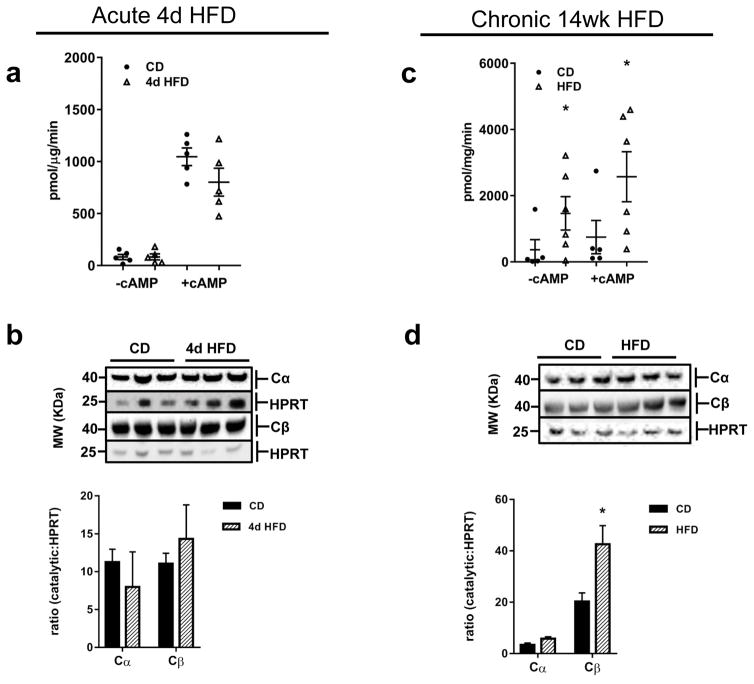

Acute HFD exposure did not affect basal or cAMP-induced PKA activities in hypothalamus (Fig 3A), nor did it impact protein expression of either PKA catalytic subunit α or β (Fig 3B). Conversely, chronic HFD-feeding increased basal and total hypothalamic PKA activities of approximately 20-fold and 4-fold, respectively, compared to levels in control-fed mice (Fig 3C). Hypothalamic expression of the predominant neuronal PKA catalytic subunit, Cβ was increased after chronic HFD and levels of Cα protein also tended to be higher in HFD-fed mice (Fig 3D). Fed-state PKA enzymatic activity was also assayed in hippocampus and striatum after long-term HFD exposure, but no differences were observed in mice (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Hypothalamic PKA activity is increased in response to chronic HFD and unchanged after acute HFD access in mice. (a) Basal and cAMP-stimulated (5 μM cAMP) PKA activities after acute 4d CD- or HFD-feeding, n=5–7/group. (b) Representative western blots and quantification of PKA Cα and Cβ in hypothalamus of mice after 4d CD- or HFD-feeding. (c) Basal and cAMP-stimulated (5 μM cAMP) PKA activities after acute 4d CD- or HFD-feeding, n=5–7/group. (d) Representative western blots and quantification of PKA Cα and Cβ in hypothalamus of mice after 14 wk CD- or HFD-feeding. Experiments repeated in two cohorts of mice. All values are mean ±SEM; *, p < 0.05.

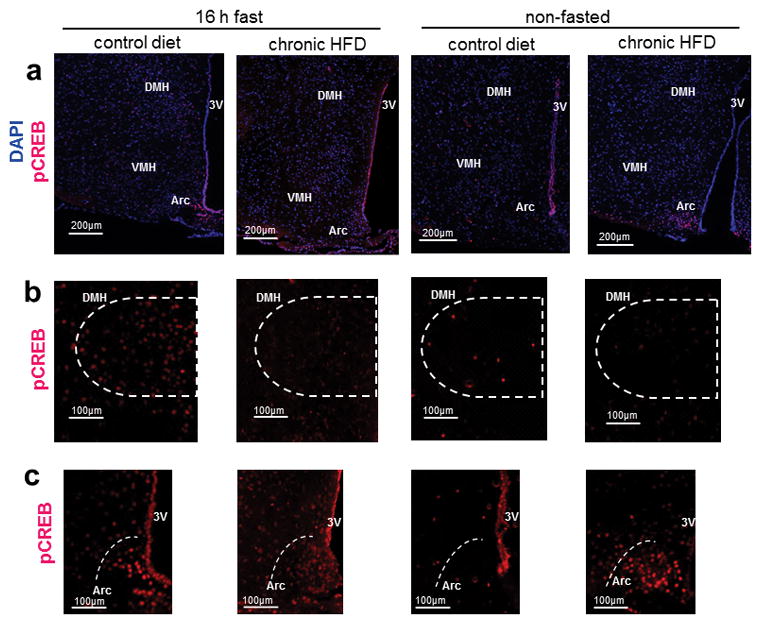

To better understand the changes in PKA signaling that accompany chronic HFD-feeding we investigated CREB phosphorylation in arcuate nucleus (Arc), dorsomedial hypothalamus (DMH) and ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) in both fed and overnight fasted mice (Figs 4A–C). After 16h overnight fast, both CD- and HFD-fed mice displayed intense staining for pCREB in Arc (Fig 4A, 4C, left panels). DMH was also positive for pCREB, but staining intensity was greater in CD-fed mice (Fig 4B, left panels). Staining for pCREB in VMH was more diffuse than in the other nuclei examined and didn’t seem to differ among treatment groups (Fig 4A). After chronic HFD access, fed-state mice exhibited intense pCREB staining in Arc similar to what was observed in fasted mice, whereas non-fasted control mice did not (Figs 4A, 4C).

Figure 4.

Phosphorylation of CREB (S133) varies in Arc, VMH and DMH in fasted vs. fed states and is dysregulated after chronic HFD-feeding in mice. (a) Representative immunofluorescent staining for pCREB (S133) (Alexa fluor 594), counterstained with DAPI in hypothalamus of 16h-fasted and non-fasted mice that were chronically exposed to either HFD or CD; scale bars = 200 μm. (b) Representative immunofluorescent staining for pCREB (S133) (Alexa fluor 594) in DMH; scale bars = 100 μm. (c) Representative immunofluorescent staining for pCREB in Arc (S133) (Alexa fluor 594); scale bars = 100 μm. Immunofluorescence experiments were repeated in 3 cohorts of mice totaling 4–6 mice per treatment group. Abbreviations: Arc: arcuate nucleus, VMH: ventromedial hypothalamus, DMH: dorsomedial hypothalamus.

Chronic HFD-feeding alters PKA subunit expression in AT, yet produces only subtle changes in PKA activity

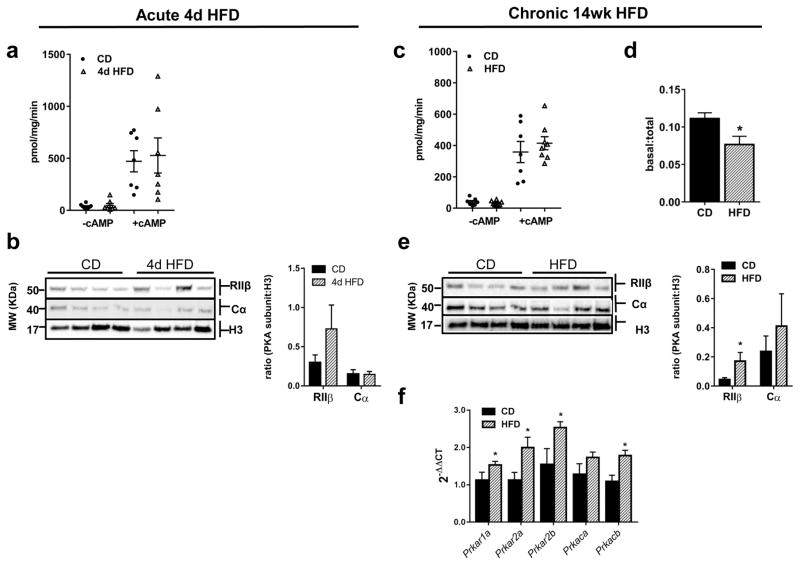

Acute exposure to HFD did not elicit significant changes in regulation of the PKA pathway in AT as evidenced by the lack of difference in basal and cAMP-induced PKA activities between CD and HFD fed mice (Fig 5A). Protein expression of PKA Cα was unchanged and while RIIβ tended to be higher they were not significantly increased after acute HFD exposure (Fig 5B).

Figure 5.

Chronic HFD-feeding impacts PKA expression in gonadal AT while PKA signaling is only modestly altered. (a) Basal and cAMP-stimulated (5 μM cAMP) PKA activities after acute 4d CD- or HFD-feeding, n=6–8/group. (b) Representative western blots and quantification of PKA Cα and RIIβ in gonadal AT of mice after 4d CD- or HFD-feeding, n=6–8/group. (c) Basal and cAMP-stimulated (5 μM cAMP) PKA activities after chronic 14wk CD- or HFD-feeding and ratio of basal to cAMP-stimulated PKA activities, n=6–8/group. (d) Representative western blots and quantification of PKA Cα and RIIβ in AT of mice after 14wk CD- or HFD-feeding, n=6–8/group. (e) mRNA expression of PKA subunits in AT after 14 week HFD-feeding (n=8/group). All values are mean ±SEM; *, p < 0.05. PKA enzymatic activity assays were repeated twice and western blots repeated three or more times.

While chronic HFD exposure did not initiate significant changes in either basal or cAMP-induced PKA activities in AT (Fig 5C), the ratio of basal to total PKA activity was decreased in HFD-fed mice (Fig 5D, p<0.03). In AT, RIIβ protein was significantly higher after chronic HFD, and while Cα protein tended to be higher the difference was not significant (Fig 5E). Despite the lack of profound changes in PKA activity after chronic HFD, mRNA expression levels of all the PKA subunits except Cα were significantly increased in AT compared to CD-fed mice suggesting alterations in regulation of the PKA system (Fig 5F).

Discussion

Chronic intake of a high fat, high calorie diet has been well documented for its ability to induce weight gain and metabolic dysfunction in humans and animals alike. Inter-individual variability in the susceptibility or resistance to DIO, however, is not well understood. Genetic background and environment are contributors, but gaining a clearer picture of the physiological underpinnings of this variability could help develop viable treatment plans to combat the obesity epidemic. For this reason we sought to explore how chronic exposure to an obesogenic diet impacts one of the primary signaling pathways that regulates energy metabolism, the PKA pathway. In order to model the most common form of human obesity, non-monogenic obesity caused by chronic consumption of a Western diet we used a wild-type mouse model of DIO and examined regulation of the PKA system at two distinct time points.

Nutrient sensing in liver regulates peripheral and central energy homeostasis by maintaining appropriate responses in glucose and lipid metabolisms during both fed and fasted states. In recent decades, what has been termed a “Western diet” has proven capable of upsetting normal hepatic function thus leading to dysregulated energy metabolism. High fat diets irrespective of fatty acid composition can cause increased fat storage in liver, elevated circulating triglycerides (de Meijer, et al. 2010) and decreased insulin sensitivity (Samuel, et al. 2004). Diets high in sucrose and fructose, prevalent in contemporary society, can acutely increase circulating triglycerides in rats (London and Castonguay 2011) and humans (Cybulska and Naruszewicz 1982). High intake of fructose-containing sweeteners can also increase hepatic triglyceride levels (Lowndes, et al. 2014) and decrease insulin sensitivity (Beck-Nielsen, et al. 1980) in human subjects. These examples demonstrate how diet composition impacts key signaling pathways both acutely and chronically and can lead to metabolic dysregulation, yet the point at which this dysregulation becomes increasingly difficult to reverse is unclear.

Mounting evidence shows that inhibition of hepatic PKA activity or its downstream targets is therapeutically beneficial in the treatment of type II diabetes-related hyperglycemia and complications related to hyperglycemia. It was recently shown that the mechanism by which biguanides, the most commonly prescribed class of T2DM drugs attenuate hepatic glucose output is by the reduction of hepatic cAMP and the subsequent decreases in PKA activation and phosphorylation of downstream targets (Miller, et al. 2013). We reported decreased hepatic PKA activity in the PKA RIIαKO mouse that conferred protection from diet-induced fatty liver and glucose intolerance (London et al. 2014a). Furthermore, hyperglycemic and hyperglucagonemic db/db mice in the fasted state had enhanced hepatic phosphorylation of CREB and IRE1α, a PKA phosphorylation target identified as a downstream regulator of glucose metabolism (Mao, et al. 2011). Cumulatively, these data support the therapeutic usefulness of inhibiting cAMP/PKA signaling at various points in the pathway.

Here we provide direct evidence that altered PKA expression in DIO and hepatic PKA hyperactivity is a characteristic of dietary obesity that may be part of a “committed step” that can be difficult to reverse in DIO. Chronic HFD-feeding causes increased hepatic protein expression of both PKA catalytic subunits, Cα and Cβ. This increase in catalytic subunit expression explains our finding of elevated cAMP-stimulated PKA activity and supports the observed tendency toward increased basal PKA activity.

The increased expression of PKA catalytic subunit protein was likely due to increased protein stability. This observation could explain the concurrent downregulation of the PKA subunits at the transcriptional level that are part of a feedback loop, and further exemplify the dysregulation of hepatic PKA in DIO. Changes in hepatic CREB phosphorylation mimicked the decrease and increase in PKA activity in acute and chronic HFD exposure, respectively, and suggest differential gene regulation by CREB in response to these two conditions.

The metabolic effects of altered hepatic PKA regulation after both acute and chronic HFD were investigated by examining downstream PKA targets, PEPCK, ACC and AMPK (Fig 2). PEPCK, the rate-limiting step in gluconeogenesis has been shown to be increased in obesity in mice (Triscari, et al. 1979) and humans alike (Oberkofler, et al. 2010). We replicate the previously described phenomenon of elevated PEPCK in obesity and show that it is associated with increased hepative PKA activity. Additionally, we show that acute HFD exposure leads to decreased PEPCK expression in mice that is associated with decreased basal hepatic PKA activity and appears to be metabolically protective in this early stage of caloric excess. The regulatory effects on ACC and pACC were less clear. While pACC is increased in DIO as expected (Fig 2B), the lack of change pACC after acute HFD-exposure may suggest that the tendency toward decreased basal PKA activity in liver was able to attenuate phosphorylation of ACC. However, when we quantified total ACC levels in the same mice, they tended to be higher. We examined AMPK levels since pAMPK is also a regulator of ACC (Witters, et al. 1991) and phosphorylation threonine 172 exerts an inhibitory effect on PKA, an effect that was observed after metformin administration (Aw, et al. 2014). Similarly pAMPK (T-172) levels tended to be but weren’t significantly higher in 4d HFD-fed mice (Fig 2c). This seemingly protective response in the face of short-term excess nutrition is likely part of a previously reported compensatory response that can counter the initial increased flux through intermediary metabolic pathways in favor of energy balance. In adult non-diabetic men energy expenditure and carbohydrate oxidation increased in response to acute hypercaloric Western diet (Larson, et al. 1995), and similarly in mice, energy expenditure increased initially upon initiation of HFD feeding but this effect was absent by the end of week one (So, et al. 2011). Whether the dysregulation we observed is directly induced by chronic HFD-feeding or is secondary to hepatic inflammation and increased adiposity is unclear.

The central defects we observed in PKA signaling appear to be secondary to increased adiposity and altered peripheral inputs since acute HFD-feeding did not elicit changes. Both basal and cAMP-stimulated PKA activity increased in hypothalamus as a result of chronic HFD-feeding, but hippocampus and striatum were not significantly affected. Visualizing hypothalamic CREB phosphorylation in fasted and fed mice highlighted how chronic HFD can impact PKA signaling in distinct nuclei (Fig 4).

In Arc, fasting induced CREB phosphorylation among CD and HFD-fed mice, although staining for pCREB appeared denser in the HFD-fed mice (Fig 4C). Interestingly, pCREB staining was barely detectable in Arc of non-fasted control mice. Interestingly, staining for pCREB in Arc of non-fasted HFD-fed mice that mimicked what was seen in fasted mice (Fig 4C). We hypothesize that chronic hyperleptinemia, hyperinsulinemia, and perhaps changes in other hormones characteristic of DIO, contribute to the increased basal and cAMP-induced hypothalamic PKA signaling and are involved in deregulation of the PKA system in hypothalamus. Yang and McKnight reported that decreased PKA signaling in Arc and decreased hypothalamic CREB phosphorylation was associated with leptin hypersensitivity in Prkar2b KO mice (Yang and McKnight 2015). This altered PKA signaling was linked to decreased energy intake and weight gain in fasted Prkar2b KO mice that were administered leptin. Our data add to this by confirming enhanced staining for phospho-CREB (S133) in Arc in the fasted state and also in Arc of non-fasted DIO mice, a pattern not observed in non-fasted lean mice. We postulate that CREB activation in Arc in fed DIO mice could play a role in the dysregulation of hypothalamic satiety signaling and the decreased inhibition in the presence of palatable food.

Altered CREB phosphorylation was observed in other hypothalamic nuclei implicated in regulation of hunger, satiety and feeding behavior. pCREB staining was noticeably present in VMH of fasted CD-fed mice and present to a lesser extent in fed CD mice, yet pCREB staining intensity in VMH was similar in HFD-fed mice regardless of their feeding status (Fig 4A). In DMH of CD-fed mice, staining for pCREB was more intense in fasted compared to fed mice, and pCREB staining was notably less intense in DIO mice (Fig 4B). DMH involvement in food-entrainment and reported increases in DMH activation at mealtime are involved in anticipatory behaviors including bouts of physical activity (Gooley, et al. 2006). The clear differences in hypothalamic CREB activation among CD- and HFD-fed mice identified nuclei where PKA-mediated dysregulation can impact circuits controlling energy intake behaviors.

While there were clear changes in liver and hypothalamus of mice with established DIO, differences in AT were more subtle. In obese human subjects decreased expression of the PKA RIIβ as well as RIα and RIIα was observed in obese compared to lean subjects (Mantovani et al. 2009). However, deficiency of RIIβ in mice enhanced basal AT PKA activity and lipolysis, and decreased fat mass (Cummings et al. 1996). While enhanced basal lipolysis and altered PKA regulation in AT are characteristics of RIIβKO mice, the changes observed in AT alone do not confer the lean phenotype. RIIαKO mice also resist DIO independent of changes in AT (London et al. 2014a). The lack of altered regulation of PKA activity in AT of DIO mice provides additional evidence that dysregulation of PKA activity in AT may not be a primary component of PKA’s role in obesity. We initially expected to find decreased basal and perhaps cAMP-stimulated PKA activity that could promote increased fat mass in DIO mice. Despite increased RIIβ and the tendency toward increased Cα protein in DIO mice, neither basal nor total PKA activities differed significantly from lean mice. We did, however, find that the ratio of basal to total PKA activity in DIO mice was reduced suggesting a change in the overall profile of PKA activity in DIO. This is in agreement with the idea that decreased basal PKA activity in AT contributes to increased lipid storage and total adiposity.

We identified sex-specific differences with regard to PKA regulation of energy balance in DIO that is seen in mice with PKA deficiencies that exhibit various sexual dimorphisms in metabolic phenotypes (Cummings et al. 1996; Enns et al. 2009; London et al. 2014a). Changes in PKA expression were more pronounced in female compared to male mice. The 3 times greater prevalence of CS in females lends further support for sex-specific metabolic regulation by PKA as CS is associated with defects in a number of molecules integral to the PKA pathway (Carney, et al. 2015). Sexual dimorphism in AT function and distribution has been documented; for a thorough overview of the literature see the review by Palmer and Clegg (Palmer and Clegg 2015). Our data in a mouse model implicate PKA regulation in the development of DIO that is present in both sexes, but more distinct in females.

In summary, there is differential regulation of the PKA signaling pathway in response to acute and chronic consumption of an obesogenic diet in a mouse model of DIO. Acute intake of excess calories from a high sugar, high fat diet produced an initial protective effect on hepatic PKA regulation by compensated for excess substrate. In the case of chronic HFD intake the PKA system became dysregulated both centrally and peripherally. It is, however, not possible to delineate whether the PKA signaling pathway is regulated directly by changes in flux of intermediary metabolism substrates, adipokines or inflammatory response. Further study of PKA dysregulation over time during HFD access, may aid in establishing a tipping point in the development of DIO with respect to the PKA system.

Supplementary Material

Quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR primers were designed and optimized to quantify relative mRNA expression of genes of interest in tissues from WT mice.

Primary and secondary antibodies used for western blotting and immunofluorescent staining in mouse liver, AT, and brain samples.

(a) Growth curves for C57Bl/6J female and (b) male mice during 14wk ad libitum feeding with either normal low fat (control diet, CD) or high fat diet (HFD); absolute lean mass and absolute fat mass of (c) female and (d) male mice fed either CD or HFD was determined by Echo MRI at week 14. Body weight was measured weekly at 0900h. All values are mean ± SEM; *, p <0.05.

DIO female and male mice have impaired glucose tolerance after chronic (14wk) HFD-feeding. Values are mean ± SEM; *, p < 0.05.

Effects of chronic 14wk HFD-feeding on PKA system regulation in liver and epididymal adipose tissue of male mice. (a) PKA activity with or without cAMP-stimulation (5μM) (n=7/group), (b) representative western blot and quantification of hepatic PKA catalytic subunit protein expression (n=5–7/group), and (c) hepatic mRNA expression of PKA subunits 14wk CD- or HFD-feeding in male mice (n=7/group). (d) Representative western blot and quantification of PKA subunit protein expression in gonadal adipose tissue (AT) (n=5–7/group), and (e) AT mRNA expression of PKA subunits in male mice after 14wk CD- or HFD-feeding (n=7/group); all values are mean ± SEM; *, p < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This work was supported by NICHD, NIH intramural research program project Z01-HD-000642-04 to Dr. C.A. Stratakis.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- Amieux PS, Cummings DE, Motamed K, Brandon EP, Wailes LA, Le K, Idzerda RL, McKnight GS. Compensatory regulation of RIalpha protein levels in protein kinase A mutant mice. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3993–3998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.3993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amieux PS, McKnight GS. The essential role of RI alpha in the maintenance of regulated PKA activity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;968:75–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aw DK, Sinha RA, Xie SY, Yen PM. Differential AMPK phosphorylation by glucagon and metformin regulates insulin signaling in human hepatic cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;447:569–573. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck-Nielsen H, Pedersen O, Lindskov HO. Impaired cellular insulin binding and insulin sensitivity induced by high-fructose feeding in normal subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1980;33:273–278. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/33.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney JA, Lyssikatos C, Lodish MB, Stratakis CA. Germline PRKACA amplification leads to Cushing syndrome caused by 3 adrenocortical pathologic phenotypes. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney JA, Young WF, Stratakis CA. Primary bimorphic adrenocortical disease: cause of hypercortisolism in McCune-Albright syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1311–1326. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31821ec4ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazabat L, Ragazzon B, Varin A, Potier-Cartereau M, Vandier C, Vezzosi D, Risk-Rabin M, Guellich A, Schittl J, Lechene P, et al. Inactivation of the Carney complex gene 1 (PRKAR1A) alters spatiotemporal regulation of cAMP and cAMP-dependent protein kinase: a study using genetically encoded FRET-based reporters. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:1163–1174. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings DE, Brandon EP, Planas JV, Motamed K, Idzerda RL, McKnight GS. Genetically lean mice result from targeted disruption of the RII beta subunit of protein kinase A. Nature. 1996;382:622–626. doi: 10.1038/382622a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cybulska B, Naruszewicz M. The effect of short-term and prolonged fructose intake on VLDL-TG and relative properties on apo CIII1 and apo CII in the VLDL fraction in type IV hyperlipoproteinaemia. Nahrung. 1982;26:253–261. doi: 10.1002/food.19820260306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Meijer VE, Le HD, Meisel JA, Akhavan Sharif MR, Pan A, Nose V, Puder M. Dietary fat intake promotes the development of hepatic steatosis independently from excess caloric consumption in a murine model. Metabolism. 2010;59:1092–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enns LC, Morton JF, Mangalindan RS, McKnight GS, Schwartz MW, Kaeberlein MR, Kennedy BK, Rabinovitch PS, Ladiges WC. Attenuation of age-related metabolic dysfunction in mice with a targeted disruption of the Cbeta subunit of protein kinase A. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:1221–1231. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooley JJ, Schomer A, Saper CB. The dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus is critical for the expression of food-entrainable circadian rhythms. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:398–407. doi: 10.1038/nn1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene EL, Horvath AD, Nesterova M, Giatzakis C, Bossis I, Stratakis CA. In vitro functional studies of naturally occurring pathogenic PRKAR1A mutations that are not subject to nonsense mRNA decay. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:633–639. doi: 10.1002/humu.20688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath A, Bertherat J, Groussin L, Guillaud-Bataille M, Tsang K, Cazabat L, Libe R, Remmers E, Rene-Corail F, Faucz FR, et al. Mutations and polymorphisms in the gene encoding regulatory subunit type 1-alpha of protein kinase A (PRKAR1A): an update. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:369–379. doi: 10.1002/humu.21178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruby A, Hu FB. The Epidemiology of Obesity: A Big Picture. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33:673–689. doi: 10.1007/s40273-014-0243-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao HP, Kirschner LS, Bourdeau I, Keil MF, Boikos SA, Verma S, Robinson-White AJ, Nesterova M, Lacroix A, Stratakis CA. Clinical and genetic heterogeneity, overlap with other tumor syndromes, and atypical glucocorticoid hormone secretion in adrenocorticotropin-independent macronodular adrenal hyperplasia compared with other adrenocortical tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:2930–2937. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner LS, Carney JA, Pack SD, Taymans SE, Giatzakis C, Cho YS, Cho-Chung YS, Stratakis CA. Mutations of the gene encoding the protein kinase A type I-alpha regulatory subunit in patients with the Carney complex. Nat Genet. 2000;26:89–92. doi: 10.1038/79238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson DE, Rising R, Ferraro RT, Ravussin E. Spontaneous overfeeding with a ‘cafeteria diet’ in men: effects on 24-hour energy expenditure and substrate oxidation. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1995;19:331–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London E, Castonguay TW. High fructose diets increase 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 in liver and visceral adipose in rats within 24-h exposure. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:925–932. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London E, Nesterova M, Sinaii N, Szarek E, Chanturiya T, Mastroyannis SA, Gavrilova O, Stratakis CA. Differentially regulated protein kinase A (PKA) activity in adipose tissue and liver is associated with resistance to diet-induced obesity and glucose intolerance in mice that lack PKA regulatory subunit type IIalpha. Endocrinology. 2014a;155:3397–3408. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London E, Rothenbuhler A, Lodish M, Gourgari E, Keil M, Lyssikatos C, de la Luz Sierra M, Patronas N, Nesterova M, Stratakis CA. Differences in adiposity in Cushing syndrome caused by PRKAR1A mutations: clues for the role of cyclic AMP signaling in obesity and diagnostic implications. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014b;99:E303–310. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowndes J, Sinnett S, Yu Z, Rippe J. The effects of fructose-containing sugars on weight, body composition and cardiometabolic risk factors when consumed at up to the 90th percentile population consumption level for fructose. Nutrients. 2014;6:3153–3168. doi: 10.3390/nu6083153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani G, Bondioni S, Alberti L, Gilardini L, Invitti C, Corbetta S, Zappa MA, Ferrero S, Lania AG, Bosari S, et al. Protein kinase A regulatory subunits in human adipose tissue: decreased R2B expression and activity in adipocytes from obese subjects. Diabetes. 2009;58:620–626. doi: 10.2337/db08-0585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao T, Shao M, Qiu Y, Huang J, Zhang Y, Song B, Wang Q, Jiang L, Liu Y, Han JD, et al. PKA phosphorylation couples hepatic inositol-requiring enzyme 1alpha to glucagon signaling in glucose metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:15852–15857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107394108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight GS, Cummings DE, Amieux PS, Sikorski MA, Brandon EP, Planas JV, Motamed K, Idzerda RL. Cyclic AMP, PKA, and the physiological regulation of adiposity. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1998;53:139–159. discussion 160–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RA, Chu Q, Xie J, Foretz M, Viollet B, Birnbaum MJ. Biguanides suppress hepatic glucagon signalling by decreasing production of cyclic AMP. Nature. 2013;494:256–260. doi: 10.1038/nature11808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesterova M, Bossis I, Wen F, Horvath A, Matyakhina L, Stratakis CA. An immortalized human cell line bearing a PRKAR1A-inactivating mutation: effects of overexpression of the wild-type Allele and other protein kinase A subunits. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:565–571. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesterova M, Yokozaki H, McDuffie E, Cho-Chung YS. Overexpression of RII beta regulatory subunit of protein kinase A in human colon carcinoma cell induces growth arrest and phenotypic changes that are abolished by site-directed mutation of RII beta. Eur J Biochem. 1996;235:486–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan MA, Sikorski MA, McKnight GS. The role of uncoupling protein 1 in the metabolism and adiposity of RII beta-protein kinase A-deficient mice. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:2302–2311. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberkofler H, Pfeifenberger A, Soyal S, Felder T, Hahne P, Miller K, Krempler F, Patsch W. Aberrant hepatic TRIB3 gene expression in insulin-resistant obese humans. Diabetologia. 2010;53:1971–1975. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1772-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer BF, Clegg DJ. The sexual dimorphism of obesity. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;402:113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2014.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planas JV, Cummings DE, Idzerda RL, McKnight GS. Mutation of the RIIbeta subunit of protein kinase A differentially affects lipolysis but not gene induction in white adipose tissue. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36281–36287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel VT, Liu ZX, Qu X, Elder BD, Bilz S, Befroy D, Romanelli AJ, Shulman GI. Mechanism of hepatic insulin resistance in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32345–32353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313478200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreyer SA, Cummings DE, McKnight GS, LeBoeuf RC. Mutation of the RIIbeta subunit of protein kinase A prevents diet-induced insulin resistance and dyslipidemia in mice. Diabetes. 2001;50:2555–2562. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.11.2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So M, Gaidhu MP, Maghdoori B, Ceddia RB. Analysis of time-dependent adaptations in whole-body energy balance in obesity induced by high-fat diet in rats. Lipids Health Dis. 2011;10:99. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-10-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triscari J, Stern JS, Johnson PR, Sullivan AC. Carbohydrate metabolism in lean and obese Zucker rats. Metabolism. 1979;28:183–189. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(79)90084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witters LA, Nordlund AC, Marshall L. Regulation of intracellular acetyl-CoA carboxylase by ATP depletors mimics the action of the 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;181:1486–1492. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)92107-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, McKnight GS. Hypothalamic PKA regulates leptin sensitivity and adiposity. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8237. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR primers were designed and optimized to quantify relative mRNA expression of genes of interest in tissues from WT mice.

Primary and secondary antibodies used for western blotting and immunofluorescent staining in mouse liver, AT, and brain samples.

(a) Growth curves for C57Bl/6J female and (b) male mice during 14wk ad libitum feeding with either normal low fat (control diet, CD) or high fat diet (HFD); absolute lean mass and absolute fat mass of (c) female and (d) male mice fed either CD or HFD was determined by Echo MRI at week 14. Body weight was measured weekly at 0900h. All values are mean ± SEM; *, p <0.05.

DIO female and male mice have impaired glucose tolerance after chronic (14wk) HFD-feeding. Values are mean ± SEM; *, p < 0.05.

Effects of chronic 14wk HFD-feeding on PKA system regulation in liver and epididymal adipose tissue of male mice. (a) PKA activity with or without cAMP-stimulation (5μM) (n=7/group), (b) representative western blot and quantification of hepatic PKA catalytic subunit protein expression (n=5–7/group), and (c) hepatic mRNA expression of PKA subunits 14wk CD- or HFD-feeding in male mice (n=7/group). (d) Representative western blot and quantification of PKA subunit protein expression in gonadal adipose tissue (AT) (n=5–7/group), and (e) AT mRNA expression of PKA subunits in male mice after 14wk CD- or HFD-feeding (n=7/group); all values are mean ± SEM; *, p < 0.05.