Abstract

Objective

To analyze the incidence and outcomes of unsuspected indeterminate but likely unimportant extracolonic findings (C-RADS category E3) at screening CT colonography (CTC).

Methods

Over 99 months (April 2004 through June 2012), 7952 consecutive asymptomatic adults (3675 men and 4277 women; mean [±SD] age 56.7 ± 7.3 years) underwent first-time screening CTC. Findings prospectively categorized as C-RADS E3 (indeterminate but unlikely important) were retrospectively reviewed, including follow-up (range, 2–10 years) and ultimate clinical outcome.

Results

Unsuspected C-RADS category E3 extracolonic findings were detected in 9.1% (725/7,952) of asymptomatic adults; 25 patients had multiple findings for a total of 751 E3 findings. Commonly involved organ systems included gynecologic (24.4%, 183/751), genitourinary (20.9%, 157/751), lung (20.6%, 155/751), and gastrointestinal (16.1%, 121/751). Consideration for further imaging, if clinically warranted, was suggested in 83.8% (608/725). 65 patients were lost to follow-up. Conditions requiring treatment or surveillance were ultimately diagnosed in 8.3% (55/660), including 8 malignant neoplasms. In the remaining 605 patients, 25 (4.1%) underwent invasive biopsy or surgery to prove benignity (including 18 complex adnexal masses), and 278 (46.0%) received additional imaging follow-up.

Conclusions

Indeterminate but likely unimportant extracolonic findings (C-RADS category E3) occur in less than 10% of asymptomatic adults at screening CTC. Over 90% of these findings ultimately prove to be clinically insignificant, with fewer than 5% requiring an invasive procedure to prove benign disease, the majority of which (>70%) were complex adnexal lesions in women.

Introduction

As a colorectal cancer screening modality, CT Colonography (CTC) has clearly demonstrated high diagnostic performance,[1, 2] reproducibility,[3] cost-effectiveness,[4, 5] and patient acceptance.[6] However, the potential burden related to extracolonic findings detected at screening CT Colonography (CTC) continues to be actively debated in regards to widespread implementation of CTC for colorectal cancer screening.[7] Multiple prior studies have analyzed extracolonic findings at CTC, including estimations of significant and potentially significant findings,[8, 9] and demonstration that the vast majority can be confirmed as clinically insignificant, despite the use of low dose technique and avoidance of intravenous contrast.[9] Nonetheless, the perceived lack of understanding of the ramifications of these extracolonic findings has been cited as a reason for exclusion of CTC from some U.S. national colorectal cancer screening guidelines.[10] In an effort to address this perceived deficiency in the literature, our research group recently published findings from a large, single-center clinical screening program detailing the incidence and outcomes of concerning or potentially important extracolonic findings,[11] which are classified as C-RADS category E4 according to the definitions established by the Working Group for Virtual Colonoscopy in 2005.[12] We found that C-RADS category E4 extracolonic findings were uncommon at screening CTC (2.5% of patients), but that nearly 70% of these findings represented clinically significant diagnoses, including a large number of frank or potential malignancies, with very few patients undergoing unnecessary further workup.

In comparison to C-RADS category E4 findings, C-RADS E3 extracolonic findings represent a more indeterminate category, which are likely unimportant but often incompletely characterized. A thorough understanding of the frequency, nature, and implications of these indeterminate extracolonic findings is vital to our assessment of CTC as a colorectal screening tool. As such, this manuscript represents a logical extension of our prior work and aims to address perceived deficiencies in the literature by expanding our understanding of indeterminate C-RADS E3 extracolonic findings at screening CTC. Herein we present the first comprehensive analysis of this group of indeterminate extracolonic findings from a clinical screening practice. Our objective is to analyze the incidence and clinical outcomes of unsuspected indeterminate but likely unimportant (C-RADS E3) extracolonic findings in a clinical CTC screening population.

Methods

This study was HIPAA-compliant and approved by our institutional review board. The requirement for signed informed consent was waived.

Patient Population

Between April 2004 and June 2012, 7952 consecutive asymptomatic adult patients (mean age 56.7 ± 7.3 years, 3675 men and 4277 women) underwent first-time CT colonography for colorectal cancer screening at our academic center. As noted, a separate sub-cohort of this screening population was previously reported on by Pooler, et al (C-RADS category E4 extracolonic findings).[11] Exclusion criteria again included a history of colorectal cancer, known inflammatory bowel disease, known polyposis syndromes, and a history of colorectal surgery. All examinations were prospectively interpreted by a board-certified radiologist practicing within our abdominal imaging section. In addition to colorectal findings–which are beyond the scope of this manuscript–extracolonic findings were recorded and patients were prospectively assigned a C-RADS extracolonic categorization based on the most significant finding (Table 1).[12] For the purposes of this study, it is important to note that extracolonic findings were only deemed “indeterminate” if they were unknown at the time of screening CTC; thus the E3 findings in this study were all unsuspected prior to screening CTC.

Table 1.

C-RADS Extracolonic Finding Categories, adapted from Zalis, et al, 2005[12]

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| E0 | Limited Exam. Compromised by artifact; evaluation of extracolonic soft tissues is severely limited. |

| E1 | Normal Exam or Anatomic Variant. No extracolonic abnormalities visible. |

| E2 | Clinically Unimportant Finding. No work-up indicated (e.g. simple liver or kidney cysts, cholelithiasis without cholecystitis, vertebral hemangioma). |

| E3 | Likely Unimportant Finding, Incompletely Characterized. Subject to local practice and patient preference, work-up may be indicated (e.g. minimally complex kidney cyst) |

| E4 | Potentially Important Finding. Communicate to referring physician as per accepted practice guidelines. (e.g. solid renal mass, lymphadenopathy, aortic aneurysm) |

CTC Protocol and Technique

The CTC technique used in our screening program has been previously described.[13] In summary, patients underwent bowel preparation beginning one day prior to CTC using a cathartic osmotic cleansing agent. Prior to 2008, sodium phosphate was used for the majority of cases but was discontinued in 2008 due to the reported risk for acute phosphate nephropathy; thereafter, magnesium citrate was used. Oral contrast material tagging of residual fluid and fecal material was achieved with 2.1% w/v barium and diatrizoate (Gastrografin). Colonic insufflation was achieved and maintained during the examination using automated continuous carbon dioxide delivered via rectal catheter. Patients were routinely scanned in both supine and prone positions, with additional decubitus positioning only as needed. Images were acquired with 8-to-64-section multi-detector CT scanners using 1.25-mm collimation, 1-mm reconstruction interval, 120 kVp, and either a fixed tube current-time product of 50–75 mAs or tube-current modulation (range, 30–300 mA). No IV contrast was administered. To evaluate for extracolonic findings, supine CT acquisitions were routinely reviewed in the transverse (axial) plane as 5-mm slices reconstructed at 3 mm intervals; thin (1.25 mm) slices, prone series, and reconstructions in other planes were used as needed on a case-by-case basis. Extracolonic evaluation is performed using standard soft-copy cine review on PACS, using any available prior imaging for comparison as needed. For colorectal assessment, images were interpreted on a standalone work station (V3D Colon, Viatronix Inc, Stony Brook, NY) using three-dimensional reconstructions for primary polyp detection, as well as two-dimensional cross-sectional images for secondary polyp detection and confirmation.[14]

Follow-up and Data Analysis

Electronic medical record review was initiated at a minimum of two years after the latest exams (November 2014) for all patients prospectively assigned a C-RADS extracolonic categorization of E3 in order to determine additional clinical and imaging follow-up, as well as to assess for any interventions and eventual outcome. Inpatient and outpatient provider notes, imaging studies, and pathology reports were included in the review. Patients who received primary care outside of our health care network were considered lost to follow-up, unless records were available for review. Data analysis was principally performed by the primary author (blinded). Student’s t-test and Fisher’s exact test were used to test for differences in continuous and categorical variables, respectively.

Results

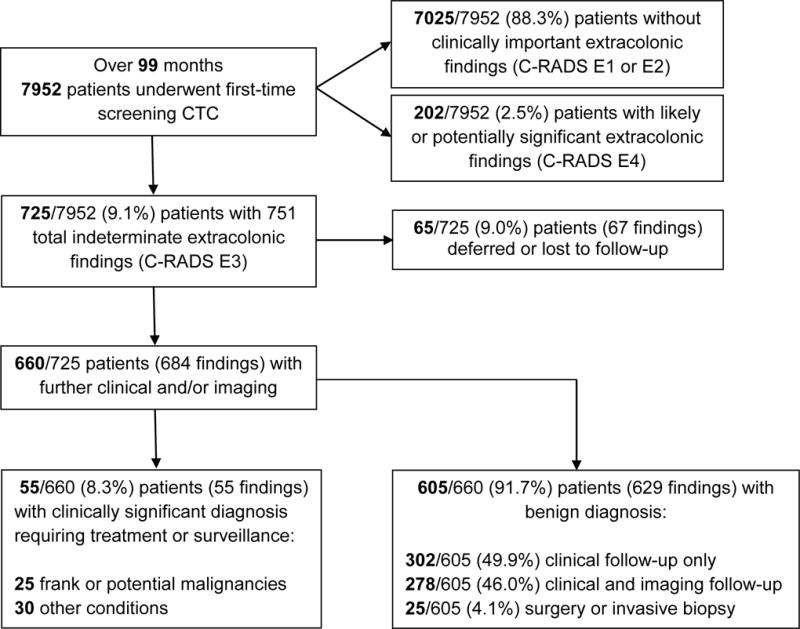

Of 7952 consecutive asymptomatic adults undergoing first-time colorectal cancer screening with CT colonography, 9.1% (725/7952) had unsuspected extracolonic findings categorized as indeterminate but likely unimportant (C-RADS extracolonic category E3) (Fig. 1). These patients were a mean [±SD] of 57.2 ± 7.7 years of age, which is not significantly different than the overall cohort (p=0.079), and included 266 men and 459 women, making this group 63.3% female, which is statistically significantly greater than the overall cohort, which was 53.8% female (p<0.0001).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study cohort

Among these 725 patients, there were a total of 751 indeterminate (C-RADS category E3) extracolonic findings, which are summarized in Table 2. Commonly involved organ systems included gynecologic (24.7%, 183/751); genitourinary (20.9%, 157/751); lung (20.6%, 155/751); gastrointestinal, including liver, biliary, pancreas, and intestinal (16.1%, 121/751), adrenal (4.0%, 27/751), lymphadenopathy (2.0%, 15/751), cardiac (1.4%, 11/751), bone (1.4%, 11/751), and spleen (1.3%, 10/751). In total, 25/725 (3.4%) patients had multiple E3 findings. Further imaging, if clinically appropriate, was suggested for in 83.8% (608/725) of patients. In total, 9.0% (65/725) of patients deferred follow-up, were followed outside our medical system, or were lost to follow-up.

Table 2.

Extracolonic Findings

| Extracolonic Finding | N |

|---|---|

| Adnexal/Uterine Mass | 179 |

| Lung Nodule | 136 |

| Kidney Mass | 130 |

| Liver Mass | 75 |

| Adrenal Mass | 27 |

| Other Genitourinary | 23 |

| Pancreas | 19 |

| Other Lung | 19 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 15 |

| Bone | 11 |

| Cardiac | 11 |

| Biliary | 10 |

| Spleen | 10 |

| Other Liver | 10 |

| Vascular | 9 |

| Gastrointestinal | 7 |

| Other Gynecologic | 4 |

| Urolithiasis | 4 |

| Breast | 1 |

| Other | 51 |

| Total | 751 |

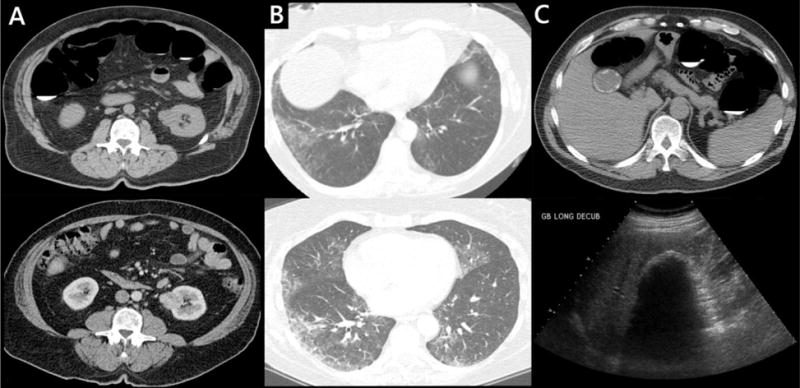

Of the remaining 660 patients, 8.3% (55/660) were found to have clinically significant pathology (Fig. 2); these findings are detailed in Table 3. No patient had more than one clinically significant diagnosis. Significant unsuspected malignancies were seen in 1.2% (8/660), including renal cell carcinoma (N=3), lymphoma (N=3), ovarian adenocarcinoma (N=1), and metastatic breast cancer (N=1). Benign or borderline neoplasms were diagnosed in 2.6% (17/660) patients, and included ovarian dermoid (N=7), ovarian mucinous cystadenoma (N=3), pancreatic mucinous cystadenoma (N=1), benign gastrointestinal stromal tumor (N=1), ovarian borderline serous tumor (N=1), renal oncocytoma (N=1), ovarian Brenner tumor (N=1), peripheral nerve sheath tumor (N=1), and pancreatic intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (N=1). Other previously undiagnosed clinically significant conditions were detected in 4.5% (30/660) of patients and included endometriosis (N=9), complicated urolithiasis (N=4), porcelain gallbladder (N=3), inflammatory bowel disease (N=2), asbestos-related pleural plaques (N=2), pneumonia (N=2), and obstructing ureterocele (N=2).

Figure 2. Unsuspected significant extracolonic findings at screening CT colonography.

A: 64-year-old man. Indeterminate renal mass (top) which enhances at follow-up contrast-enhanced CT (bottom). Later proven to be renal cell carcinoma at biopsy. B: 61-year-old nonsmoking woman. Incompletely evaluated groundglass opacity at the lung bases at CTC (top), more thoroughly evaluated at dedicated chest CT(bottom) and consistent with nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP). C: 52-year-old man. Porcelain gallbladder seen at CTC (top) and confirmed at follow-up ultrasound (bottom). The patient subsequently underwent cholecystectomy.

Table 3.

Significant Unsuspected Extracolonic Findings

| Malignant Tumors | N | |

|---|---|---|

| Renal Cell Carcinoma | 3 | |

| Lymphoma | 3 | |

| Ovarian Adenocarcinoma | 1 | |

| Metastatic Cancer, Breast | 1 | |

| Other Tumors | ||

| Dermoid | 7 | |

| Mucinous Cystadenoma | 4 | |

| Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor | 1 | |

| Ovarian Borderline Serous Tumor | 1 | |

| Renal Oncocytoma | 1 | |

| Ovarian Brenner Tumor | 1 | |

| Nerve Sheath Tumor | 1 | |

| Pancreatic IPMN | 1 | |

| Other | ||

| Endometriosis | 9 | |

| Complicated Urolithiasis | 4 | |

| Porcelain Gallbladder | 3 | |

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease | 2 | |

| Asbestos-related Pleural Plaques | 2 | |

| Pneumonia | 2 | |

| Obstructing Ureterocele | 2 | |

| Aspiration | 1 | |

| Choledocholithiasis | 1 | |

| Renal Atrophy | 1 | |

| Lymphangioleiomyomatosis | 1 | |

| Nonspecific Interstitial Pneumonia | 1 | |

| Portal Vein Thrombosis | 1 | |

| Total | 55 | |

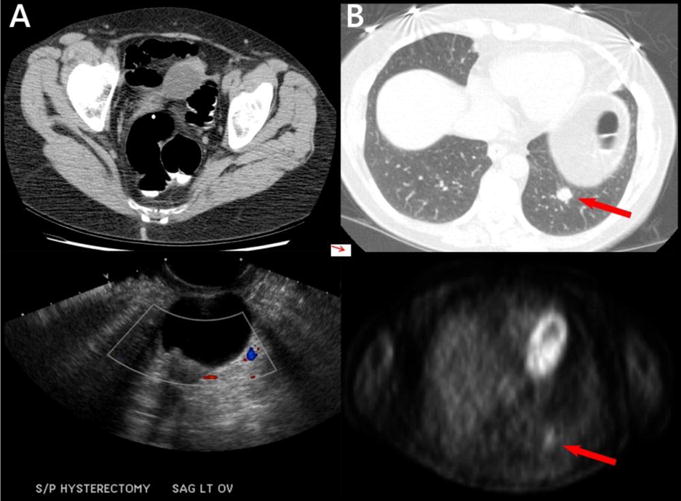

In total, 91.7% (605/660) of patients had a total of 629 findings that ultimately proved to be clinically unimportant. Of these, 95.9% (580/605) of patients underwent either clinical follow-up only (49.9%, 302/605) or clinical follow-up with additional imaging (46.0%, 278/605), whereas 4.1% (25/605) of C-RADS category E3 patients (0.3% of the total screening population, 25/7952) underwent surgery or invasive biopsy to prove benign disease (Fig. 3). The majority (72.0%, 18/25) of these were for complex but ultimately benign adnexal masses, such as serous cystadenoma and other benign variants. Other benign diagnoses included endometrial polyp (N=2), lung granuloma (N=2), complicated-appearing adrenal cyst (N=1), benign prostatic hypertrophy (N=1), and a focus of non-specific intraperitoneal inflammation (N=1).

Figure 3. Extracolonic findings resulting in surgery or biopsy to prove benign disease.

A: 58-year-old woman. An indeterminate left adnexal lesion (top) demonstrates mural nodularity at follow-up ultrasound (bottom) and was found to be a serous cystadenofibroma at pathology after surgical resection. B: 69-year-old nonsmoking woman. A relatively rounded lung nodule seen at CTC (red arrow, top) was metabolically active at PET (red arrow, bottom) and underwent percutaneous biopsy, revealing a benign granuloma.

Discussion

Extracolonic findings remain among the most controversial topics with regard to widespread implementation of CT colonography for colorectal cancer screening.[15] In fact, extracolonic findings were specifically cited by the US Preventative Services Task Force as an area needed study while issuing preliminary colorectal cancer screening recommendations.[10] With the publication of this manuscript, we complete our analysis of an asymptomatic CTC screening cohort comprising 7952 individuals, which began with our prior evaluation of potentially significant extracolonic findings (a cohort of 202 patients with C-RADS category E4 findings)[11] and concludes with the current analysis of indeterminate but likely unimportant extracolonic findings (a cohort of 725 patients with C-RADS category E3 findings). When discussing the E3 cohort, it is important to take the results of the previously evaluated E4 cohort into consideration, as these two groups represent the sum total of patients with potentially worrisome or indeterminate extracolonic findings—especially when trying to convey metrics such as overall rates of malignancy or the percentage of patients undergoing an invasive procedure to prove a benign diagnosis.

Prior studies have reported approximately 85% of asymptomatic adult patients undergoing screening CTC have either no extracolonic findings, or extracolonic findings that are clearly clinically unimportant (C-RADS extracolonic categories E1 and E2).[16, 17] The present study essentially confirms this previous figure, as 927/7952 patients (11.7%) of our total population had either C-RADS category E3 (N=202) or E4 (N=725) findings, leaving the remaining 7025/7952 patients (88.3%) without clinically relevant extracolonic findings (C-RADS category E1 or E2). Despite persistent concern for a large number of follow-up imaging studies, the actual work up rate for all reported extracolonic findings has consistently been less than 10% in large CTC series.[18–22] Our current study supports these conclusions, and suggests that in practice the rate of further imaging workup for incidentally detected extracolonic findings ultimately diagnosed as benign is 4.0% (320/7952 total; 278 from the E3 cohort and 42 from the E4 cohort).

Furthermore, the overall rate of patients undergoing an invasive procedure such as surgery or biopsy to ultimately prove benign disease is low. From our total screening population, 25 patients from the E3 cohort and 11 from the E4 cohort underwent surgery or biopsy for benign disease, for an overall rate of 36/7952 or 0.45%. Of note, 21/36 (58%) of all extracolonic findings leading to surgery or biopsy for an ultimately benign condition were due to complicated-appearing adnexal masses; such incidental adnexal findings have long been a dilemma for both radiologists and obstetrician-gynecologists.[23–25] Despite follow-up ultrasound (and in some cases MR), the decision was ultimately made to remove these complicated-appearing lesions for both diagnosis and definitive management. The prevalence of indeterminate adnexal masses is largely responsible for the increased number of women observed in the E3 cohort, and comprised over 70% of invasive procedures for benign disease within our C-RADS E3 cohort.

In addition to acceptably low rates of “unnecessary” workup, our studies demonstrate substantial benefit from CTC in the form of incidentally detected malignancies and other clinically significant conditions—in addition to the recognized colorectal cancer prevention and screening benefit. When the 25 frank or potential malignancies and 30 other clinically significant conditions from the E3 cohort are combined with the 42 frank or potential malignancies, 46 abdominal aortic (AAA) or other significant vascular aneurysms, and 57 other clinically significant conditions from the E4 cohort, the result is an overall rate of diagnosis of 200/7952 or 2.5% previously unsuspected clinically significant diagnoses. These conditions include a number of typically indolent malignancies, such as renal cell carcinoma and lymphoma, which may benefit from detection and treatment in earlier disease stages. [18] Furthermore, downstream benefits of detection and treatment of vascular aneurysms—principally AAA—before symptomatic presentation are considerable. In addition to reduced morbidity and mortality, modeling studies suggest that the benefit of this single incidental diagnosis balanced against the generated costs of work-up of all incidental findings at CTC screening makes CTC cost effective compared to optical colonoscopy.[18, 21]

We acknowledge some limitations. Our data were gathered at a single large academic medical center and rates of extracolonic findings as well as specific diseases may not generalize to dissimilar populations. Our screening CTC examinations are performed with low dose technique[13] and without intravenous contrast; centers with differing protocols may observe different results. Given the clinical nature of our practice, we are dependent upon primary care physician referral for our screening CTC patients, which may result in selection bias. Additionally, we are also reliant upon the same primary care physicians as well as consulting specialists for decisions regarding additional follow-up of patients, which may introduce inconsistency. Such limitations, however, are inevitable in any referral-based screening program, and we feel are mitigated by our large patient population.

In conclusion, unsuspected indeterminate but likely unimportant extracolonic findings (C-RADS category E3) at screening CTC are found in less than 10% of patients, of which 90% will ultimately prove to be benign and unimportant. When taken into consideration with previously published results from a C-RADS category E4 cohort, clinically significant conditions—including a number of malignancies—requiring treatment or surveillance are detected in approximately 4% of asymptomatic screening CTC patients. Furthermore, in practice approximately 4% of patients undergo further imaging work-up to prove benign disease, and only fewer than 1% of patients undergo invasive biopsy or surgery to ultimately prove benign disease, with a majority of these due to complicated-appearing adnexal masses in women.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (Grant 1R01CA144835-01).

Dr. Pickhardt is co-founder of VirtuoCTC, and shareholder in SHINE and Cellectar Biosciences. Dr. Kim is co-founder of VirtuoCTC, a consultant for Viatronix, and on the medical advisory board for Digital Artforms. Dr. Pooler has no relevant disclosures. This study has been approved by our institutional review board.

References

- 1.Kim DH, Pickhardt PJ, Taylor AJ, et al. CT colonography versus colonoscopy for the detection of advanced neoplasia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357:1403–1412. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pickhardt PJ, Choi JR, Hwang I, et al. Computed tomographic virtual colonoscopy to screen for colorectal neoplasia in asymptomatic adults. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349:2191–2200. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pooler BD, Kim DH, Hassan C, Rinaldi A, Burnside ES, Pickhardt PJ. Variation in Diagnostic Performance among Radiologists at Screening CT Colonography. Radiology. 2013;268:127–134. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13121246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pickhardt PJ, Hassan C, Laghi A, Zullo A, Kim DH, Morini S. Cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening with computed tomography colonography - The impact of not reporting diminutive lesions. Cancer. 2007;109:2213–2221. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knudsen AB, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Rutter CM, et al. Cost-Effectiveness of Computed Tomographic Colonography Screening for Colorectal Cancer in the Medicare Population. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2010;102:1238–1252. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pooler BD, Baumel MJ, Cash BD, et al. Screening CT Colonography: Multicenter Survey of Patient Experience, Preference, and Potential Impact on Adherence. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2012;198:1361–1366. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plumb AA, Boone D, Fitzke H, et al. Detection of Extracolonic Pathologic Findings with CT Colonography: A Discrete Choice Experiment of Perceived Benefits versus Harms. Radiology. 2014;273:144–152. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14131678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sutherland T, Coyle E, Lui B, Lee WK. Extracolonic findings at CT colonography: A review of 258 consecutive cases. Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Oncology. 2011;55:149–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-9485.2011.02244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pickhardt PJ, Taylor AJ. Extracolonic findings identified in asymptomatic adults at screening CT colonography. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2006;186:718–728. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Draft Recommendation Statement: Colorectal Cancer: Screening. US Preventive Services Task Force. 2015 Oct; http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/draft-recommendation-statement38/colorectal-cancer-screening2.

- 11.Pooler BD, Kim DH, Pickhardt PJ. Potentially Important Extracolonic Findings at Screening CT Colonography: Incidence and Outcomes Data From a Clinical Screening Program. Feb. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016;206(2):313–318. doi: 10.2214/AJR.15.15193. E-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zalis ME, Barish MA, Choi JR, et al. CT colonography reporting and data system: A consensus proposal. Radiology. 2005;236:3–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2361041926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pickhardt PJ. Screening CT colonography: How I do it. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2007;189:290–298. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pickhardt PJ, Lee AD, Taylor AJ, et al. Primary 2D versus primary 3D polyp detection at screening CT Colonography. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2007;189:1451–1456. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pedersen BG, Rosenkilde M, Christiansen TEM, Laurberg S. Extracolonic findings at computed tomography colonography are a challenge. Gut. 2003;52:1744–1747. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.12.1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pooler BD, Kim DH, Lam VP, Burnside ES, Pickhardt PJ. CT Colonography Reporting and Data System (C-RADS): Benchmark Values From a Clinical Screening Program. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2014;202:1232–1237. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Veerappan GR, Ally MR, Choi JHR, Pak JS, Maydonovitch C, Wong RKH. Extracolonic Findings on CT Colonography Increases Yield of Colorectal Cancer Screening. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2010;195:677–686. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hassan C, Pickhardt P, Laghi A, et al. Computed tomographic colonography to screen for colorectal cancer, extracolonic cancer, and aortic aneurysm. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008;168:696–705. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.7.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Macari M, Nevsky G, Bonavita J, Kim DC, Megibow AJ, Babb JS. CT Colonography in Senior versus Nonsenior Patients: Extracolonic Findings, Recommendations for Additional Imaging, and Polyp Prevalence. Radiology. 2011;259:767–774. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11102144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pickhardt PJ, Hanson ME, Vanness DJ, et al. Unsuspected extracolonic findings at screening CT colonography: clinical and economic impact. Radiology. 2008;249:151–159. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2491072148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pickhardt PJ, Hassan C, Laghi A, Kim DH. CT Colonography to Screen for Colorectal Cancer and Aortic Aneurysm in the Medicare Population: Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2009;192:1332–1340. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.2646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zalis ME, Blake MA, Cai WL, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Laxative-Free Computed Tomographic Colonography for Detection of Adenomatous Polyps in Asymptomatic Adults A Prospective Evaluation. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2012;156:692–U671. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-10-201205150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoover K, Jenkins TR. Evaluation and management of adnexal mass in pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2011;205:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slanetz PJ, Hahn PF, Hall DA, Mueller PR. The frequency and significance of adnexal lesions incidentally revealed by CT. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1997;168:647–650. doi: 10.2214/ajr.168.3.9057508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pickhardt PJ, Hanson ME. Incidental adnexal masses detected at low-dose unenhanced CT in asymptomatic women age 50 and older: implications for clinical management and ovarian cancer screening. Radiology. 2010;257:144–150. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]