Abstract

The skin cells continuously produce, through cellular respiration, metabolic processes or under external aggressions, highly reactive molecules oxidation products, generally called free radicals. These molecules are immediately neutralized by enzymatic and non-enzymatic systems in a physiological and dynamic balance. In situations where this balance is broken, various cellular structures, such as the cell membrane, nuclear or mitochondrial DNA may suffer structural modifications, triggering or worsening skin diseases. several substances with alleged antioxidant effects has been offered for topical or oral use, but little is known about their safety, possible associations and especially their mechanism of action. The management of topical and oral antioxidants can help dermatologist to intervene in the oxidative processes safely and effectively, since they know the mechanisms, limitations and potential risks of using these molecules as well as the potential benefits of available associations.

Keywords: Antioxidants, Carotenoids, Dermatitis, DNA damage, Free radicals, Polypodium, Skin aging

INTRODUCTION

Skin and mucous membranes have a contact and defense barrier role against chemical, physical and biological aggressions continuously.1

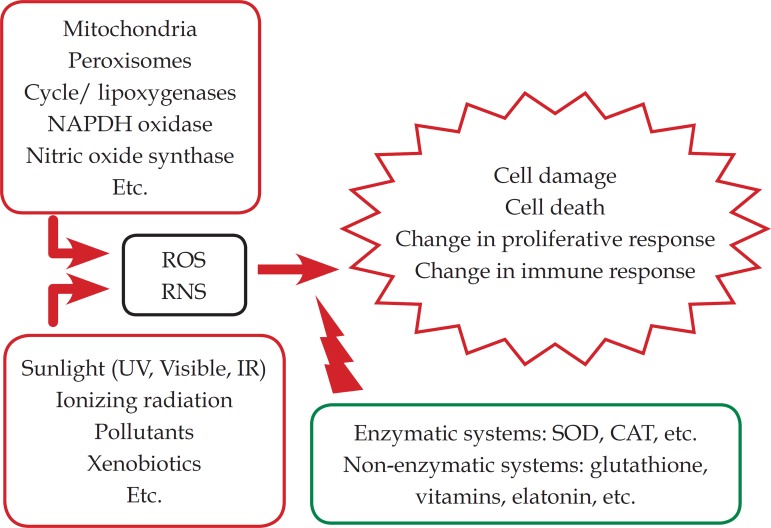

Maintenance of cellular integrity, as well as of all immune mechanisms, whether inborn (cutaneous lipids and plasma membranes, for example) or specific (cytokine synthesis, enzymes or cell proliferation), involves a series of chemical reactions that generate reactive oxygen species - highly reactive molecules that can rapidly alter molecules fundamental to cutaneous homeostasis, such as proteins, lipids, or DNA.2 Endogenous or exogenous antioxidant mechanisms act by neutralizing these reactive molecules. The imbalance of this neutralization has multiple consequences: free radicals are implicated in the etiopathogenesis of various dermatoses, as well as in the aging process and in the onset of cutaneous neoplasias.3

Proper use of antioxidants should be considered in these situations where evidences of their benefits have been accumulating in the last decades.

OXIDATIVE MECHANISMS AND SKIN PHYSIOLOGY

The main reactive oxygen species (ROS) are the hydroxyl radicals (HO•) and superoxide (O2•-), peroxyl and alkoxyl radicals (RO2• and RO•), the singlet oxygen (1O2)3-5, as well as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and organic peroxides (ROOH).4 In addition to direct damage to molecules such as lipids, amino acids and DNA, ROS can activate enzymatic and non-enzymatic cellular responses, with the potential to modify other processes that end up interfering with gene expression.5

Antioxidants are substances that combine to neutralize reactive oxygen species preventing oxidative damage to cells and tissues.6 The cutaneous antioxidant system consists of enzymatic and non-enzymatic substances. Among enzymatic antioxidants, glutathione peroxidase (GPx), catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) can be highlighted.7

Non-enzymatic or low molecular weight antioxidants also contribute to the maintenance of cellular redox balance. Here some hormones are grouped such as estradiol and, melatonin, as well as some vitamins, such as E and C.8

Figure 1 summarizes the main oxidative sources and their antioxidant systems; participating.9

Figure 1.

Diagram of the redox balance in the skin

THE PARADOX OF ANTIOXIDANTS EXCESS

Generation of ROS in physiological conditions, such as respiration or even physical exercise, is important in the maintenance of cellular functional integrity. These molecules generally induce intracellular enzymatic processes via transcription factors (FoxO) that induce the expression of antioxidant enzymes, such as SOD.9 Increased levels of FoxO reduce cell proliferation and induce apoptosis. These factors are involved in cell growth, proliferation, differentiation and longevity.10

Balance of antioxidant systems and the endogenous generation of ROS is dynamic and tenuous.

There is evidence that situations of mild stress, such as caloric restriction or physical activity, can modulate the aging process, since they increase mitochondrial activity, also increasing the generation of ROS - which would provoke an adaptive response, with improvement of defense mechanisms and consequent better response and resistance to stress.11

Although this question is not yet studied for skin physiology and pathology, it may be valid, especially for chronological aging in healthy individuals.

Therefore, the ingestion or application of antioxidant molecules is indicated in situations in which there is an inability to neutralize, both by the ROS excess and by the decline of endogenous systems, as occurs in aging and in some diseases.

However, not all molecules of antioxidant potential, from the physiological point of view, act linearly in cutaneous oxidative stress; an important example of this is the oral use of beta-carotene.

A randomized, controlled trial to determine whether the impact of the use of beta-carotene supplementation, associated or not to sunscreens, could delay the signs of photoaging was developed between 1992 and 1996; no significant effect of 30 mg daily supplementation of beta-carotene was identified.12 Likewise, another carotenoid, lycopene, does not present a photoprotective effect when ingested orally, both in natura and in supplementation.13

However, there is evidence that these molecules can also lead to deleterious effects when used indiscriminately. The risk of hypervitaminosis in older patients, in whom renal excretory function is reduced, is an example.14

Most emblematic, however, is the issue of vitamin E: tocopherol and its esters are some of the most documented antioxidants and they are commonly used for their proven action on induced ultraviolet damage. Its indiscriminate use, however, can inhibit glutathione-S-transferase, responsible for the removal of cytotoxic compounds related to tumorigenesis in the skin.15,16

Resveratrol itself, with its recognized antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities, has conflicting data regarding its doses: recent data demonstrate its bioactivity in nanometric doses when derived from phytochemicals in food - and this demonstrates how it can be difficult to evaluate the synergy, or even antagonism, of the association between dietary components.17

The administration of antioxidants in smaller doses, but in combination, has been asserting as the safest alternative for its use. Vitamin E acts in synergy with vitamin C, which regenerates the radical tocopheryl, a product of alpha-tocopherol oxidation.18

Supplementation with beta-carotene, this time associated with lycopene and a probiotic, promoted the prevention of polymorphic light eruption in a study also randomized.19 Similarly, another randomized study, conducted with an association of vitamins A, C, E, selenium, pomegranate extract, quercetin, green tea, coenzyme q10 and carotenoids, such as lutein, lycopene and zeaxanthin, led to an improvement in the erythematous dose and absorption levels of free radicals after 4 weeks of use.20

These findings suggest that the use of combinations of multiple antioxidant molecules allows not only to amplify the antioxidant action in several sites but also to obtain an amplified action, comparable to a monotherapy in high doses. For this reason, each association should be ideally evaluated for its clinical effects.21

MAIN INDICATIONS IN DERMATOLOGY

Photodamage

Currently, there is enough evidence to assert that all solar spectrum favors the generation of free radicals; this generation possibly favors, to a greater or lesser extent, photoaging, photoimuniosuppression and photocarcinogenesis.22

Ultraviolet (UV) radiation, in its UVB range (290-320 nm), is responsible for the immediate damages of solar radiation, acting mainly on keratinocytes; UVA band (320-400 nm), which induces cellular changes, particularly compromises melanocytes and fibroblasts.

In addition to consuming antioxidant systems, UV damage leads to inflammation, and neutrophil infiltrate activates NAD(P)H oxidase, generating ROS that alter the production of keratinocytic cytokines.23,24

Use of antioxidants in the prevention and repair of ultraviolet photodamage is widely studied, being the most known and used indication. Association of antioxidant molecules, from vitamins to phytoextracts, in photoprotectors and moisturizers with appeal against aging, is frequent.25-27

A study with the objective of proving the efficacy of an association of antioxidants with trace elements and glycosaminoglycans in a randomized control study showed clinical improvement of signs of photoaging after 3 months of use.28

Oral use of antioxidants does not dispense the use of sunscreens and is therefore a second line of protection against UV photodamage even when they reduce the appearance of solar erythema, such as Polypodium leucotomos.29

Antioxidant action of this phytoextract not only occurs by the neutralizing effect of ROS, blocking lipid peroxidation, but also by activating natural antioxidant systems.

Although the indication of Polypodium leucotomos in our scenario is for polymorphic light eruption, there is consistent evidence of its use in other dermatoses as well as in photoaging.30

The combination of oral antioxidants at physiological doses recommended daily intake (RDI) is also able to increase minimum erythemal dose levels (MED). 31

Regarding visible light (400-720 nm), it produces about 50% of the total oxidative stress caused by sunlight. Reactive species such as O2- * and * * OH CHR are generated by visible light.32

Although there is evidence of cutaneous carotene depletion induced by visible light, use of topical or oral antioxidants, to reduce free radicals generated by this range, has not yet been elucidated.33

Lutein, a carotenoid already used in ophthalmology in the treatment of macular degeneration, has been associated with a protective effect of oxidative damage from sunlight, particularly by visible light, by absorbing blue light.34

A double blind, placebo-controlled study compared the efficacy of oral supplementation with topical application of lutein combined with zeaxanthin to five parameters: epidermal lipids, hydration, photoprotective activity, skin elasticity and lipid peroxidation under UV radiation. After 12 weeks, both treatments improved these measures, and oral administration was superior, but the combination (oral and topical) provided the greatest protection.35

More recently, studies have shown that thermogenic infrared radiation is also capable of generating free radicals in human skin; its ambiguous effect, since it is also used therapeutically, depends on two distinct mechanisms: the NF-kB signaling pathway is responsible for the therapeutic effects, whereas the AP-1 pathway is responsible for the pathological effects.29 AP-1 is responsible for the production of metalloproteinases that promote collagen breakage, clinically inducing wrinkles.36,37

The ability of infrared radiation to deeply penetrate favors the generation of free radicals, as it can cause mutation in mitochondrial DNA.38

Some studies have been conducted with the objective of investigating which antioxidants would be the most adequate for inhibiting the effect of this radiation, using combinations of topical use of known molecules; a topical combination of vitamins C, E, ubiquinone and grape extract showed positive results in a comparative study.39

Aging

Concomitant with solar radiation and other environmental factors responsible for oxidative phenomena, skin aging, as well as of all organs, is accompanied by the decline of the endogenous antioxidant mechanisms.

Clinically, the findings of photoaging are the predominant, and it is difficult - and often unnecessary in practice - to distinguish the impact of exogenous factors on the chronological process, but it is known that the main finding of intrinsic aging is cutaneous atrophy, by the reduction of epidermis, but, mainly, by the decrease in the collagen content and other dermal elements.40

In the intrinsic aging process, progressive damage to mitochondrial DNA occurs, with increased ROS production, which causes cell aging and impairs protein proliferation.41

The theory of aging from free radicals was developed in the 1950s; later, it was observed that the cellular organelle responsible for the cellular metabolism, the mitochondria, was the main generator of free radicals due to the cellular respiration that occurs in it.42

In its reduced form, ubiquinol (coenzyme Q10) prevents this oxidative activity and also regenerates alpha-tocopherol. Coenzyme Q10 is the only soluble lipid antioxidant that animal cells can synthesize and for which there is an appropriate enzymatic mechanism to regenerate it - which also declines over time.43 Finally, coenzyme Q10 has been shown to influence (by mechanism of gene induction) the synthesis of key cutaneous proteins and to inhibit the expression of some metalloproteinases, such as collagenase, by preserving the collagen content of the skin.44

In skin aging, there is a progressive accumulation of proteins, DNA and modified lipids, reinforcing the association between ROS and intrinsic aging.45

Among the multiple antioxidant mechanisms, SOD plays a central role in the variety of reactive molecules it neutralizes. Although there is still no direct correlation, animal models suggest that the lack of SOD leads to degenerative changes with reduced collagen. Possibly, vitamin C would have a positive impact on SOD reduction states preventing atrophy due to collagen degradation.46

The most physiological protective effect against oxidative stress seems to be the support to the endogenous system, using antioxidants normally present in the skin. This strategy, however, should not be confused with the permanent use of high non-physiological doses of isolated antioxidants, nor considered as a substitute for adequate food.47

Melasma

Induced UV melanogenesis that occurs in melasma is amplified by increasing the oxidation of dopaquinone; antioxidants such as vitamin C, which reduce dopaquinone (DOPA), prevent the formation of free radicals.48

The induced UV inflammatory process also favors the increase of melanogenesis.49

A clinical A clinical trial to study the endogenous the endogenous antioxidant systems in patients with melasma demonstrating a significant consumption of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase. This result demonstrates the rupture of the redox equilibrium.50

Oxidation is a process that may favor melasma, but the exclusive use of antioxidants in its treatment does not seem to have a relevant effect. Antioxidant molecules employed that have proven utility also have whitening action by inhibition of tyrosinase (for example, ascorbic acid and ellagic acid) or anti-inflammatory (for example, pycnogenol).51-53

Non-melanoma skin cancer

Generation of UV induced free radicals in the skin develops oxidative stress when it exceeds the ability of natural defense: the only skin protection systems are antioxidant enzymes and melanin, the first line of defense against DNA damage.54

DNA absorbs ultraviolet light, whose energy can break its molecular bonds; most of these breaks are repaired by enzymes present in the nucleus itself, however the remaining damages generate mutations that lead to neoplasia.55

The two main actions of defenses that antioxidants can provide are in relation to preventing the formation of free radicals or neutralizing the radicals already generated.56

Epidermal antioxidant capacity is much higher than the dermal: catalase, glutathione peroxidase and glutathione reductase systems were higher in the epidermis than in the dermis - both the lipophilic antioxidants (tocopherol, ubiquinol 9, etc.) and the hydrophilic ones (ascorbic acid and glutathione). The stratum corneum contains both hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidants. Vitamins C and E, as well as glutathione (GSH) and uric acid, were found. Surprisingly, they are not evenly distributed, but in gradient form, with lower concentrations in the outer layers and higher concentrations toward the deeper layers of the stratum corneum.57

It is also confirmed that the acute exposure of human skin to solar radiation leading to oxidation can be prevented by previous treatments with antioxidants, reducing the risk of carcinogenesis.58

In contrast, there is evidence that treatment with topical antioxidants after UV damage can interfere with the cell cycle or apoptosis of damaged cells, not bringing benefit or even potentiating the damage.59

Therefore, endogenous photoprotection with antioxidants is complementary to photoprotection with sunscreens, and is currently the most adequate form of photocarcinogenesis prevention, in addition to, of course, the photoprotection behavior (seeking shadows, avoiding hours of greater sunshine, etc.).60

Psoriasis

There are consistent systemic signs of oxidative stress in patients with active psoriasis: plasma levels of malonyldialdehyde (MDA) are significantly elevated, suggesting the depletion of natural enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant systems and consequently the prevalence of peroxidation processes in cell membranes and plasma lipid processes of circulating cells.61 Similarly, SOD is reduced in erythrocytes of psoriatic patients.62

The inflammatory process itself in the lesion areas induces the formation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species.63

On the other hand, classic treatments such as phototherapy or methotrexate are also capable of generating ROS and RNS.

However, the eventual use of antioxidants should aim to recover the redox balance, leading to an anti-inflammatory effect, possibly by the activation of antiproliferative and proapoptotic pathways, both in the local and in the inflammatory cells.9

Alopecia

The possible benefit of the use of antioxidants in telogen effluvium will be according to the underlying cause, especially when linked to systemic inflammatory processes, but there is no direct evidence of any oxidative mechanism directly linked to this tricose.

In alopecia areata, there is evidence of increased plasma SOD activity and in the affected tissue, however the studies are still controversial.64

Other dermatoses

Many inflammation conditions demonstrate redox imbalance and significant consumption of their antioxidant systems in local cells, such as atopic dermatitis or burned skin, as well as in the scarring process, in which the excess of ROS hinders dermal and epidermal repair, especially in the moment of acute inflammation.65

Observational studies of melanoma patients demonstrate a correlation between the lower incidence of the disease and the daily consumption of carotenoid and vitamin C-rich tea and vegetables, as well as the high consumption (at least three portions/week) of dark green vegetables rich in lutein; however, there is no elucidation whether the antitumor mechanism involved would be antioxidant.66

Polypodium leucotomos extract has demonstrated a complementary effect on the limitation of melanoma cell growth, but the impact of the antioxidant mechanism on this effect is unclear.67 There is also evidence of oxidative stress in dermatoses such as vitiligo, lichen planus, acne vulgaris, seborrheic dermatitis and pemphigus foliaceus, but there are no clinical studies demonstrating the impact of the use of antioxidants in the control of these diseases, both oral and topically.68-72

PRACTICAL ASPECTS ON THE USE OF ANTIOXIDANTS

Use of oral or topical antioxidants in the treatment of dermatoses basically seeks to neutralize excess free radicals, reducing or preventing the attack on cellular structures. As the preservation or reestablishment of the redox balance is the goal in these situations, the use of antioxidants should always be in line with treatments or other preventive measures, as in the case of photoprotection.73

In this context, the use of concentrations close to the physiological ones is preferential, since they adjust more easily to the cellular physiology, in addition to reducing risks of toxicity or even of drug interaction with any drugs that the patient uses. Effects of antioxidants can vary considerably depending on the concentrations.74

It is important to note that the use of oral or topical antioxidants does not replace a diet with fruit and vegetable consumption, in which the combination of the active elements expands its effects, and does not involve any risk. Lycopene, for example, readily found in tomato paste, ingested on the order of 55 g/day for 12 weeks, led to a significant reduction of MMP-1 expression in a randomized controlled study.75

Rich and varied diet should be encouraged in normal individuals; however, groups such as patients after bariatric surgery, elderly, and people with dietary restrictions may have vitamin deficiencies, in which reposition in physiological doses would be indicated.

Use of antioxidants in long-term pharmacological concentrations should only be considered in situations where there is a diagnosed need under strict medical supervision.76,77

Association of antioxidants with complementary mechanisms allows a broader neutralizing action, with adequate safety of use during the period of oxidative stress - which can be from a simple sun exposure to extensive and acute phase dermatosis.78,79

Use of supplements without indication, or ingested in high doses, or even for a prolonged time can, in thesis, cause adverse events precisely in the physiological antioxidative balance. Hence the importance of medical monitoring.11

It is important to highlight that, among the exogenous antioxidants available on the market, the scientific evidence regarding the actual effect on skin cell lines is varied.

Likewise, the proposed associations may have varied responses according to the concentrations and molecules involved. The evaluation of clinical response should be made in order to better understand the effects in relation to the proposed indication.

Another important point is that the in vitro effect does not necessarily correspond to the clinical effect, influenced by route of administration, level of concentration in administration and target cell, level of degradation etc. Chart 1 lists the major antioxidants with action on the skin by oral or topical administration and their mechanisms of action.

Chart 1.

Main molecules with antioxidant action, both topical and oral, of prescription in Dermatology

| Molecule | Mechanism of antioxidant action |

|---|---|

| Vitamin E | Neutralization of singlet oxygen in the cell membrane; involvement with membrane stabilization, preventing lipid peroxidation - oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids, such as arachidonic acid from membrane phospholipids, which may lead to rupture of the cell membrane80,81 |

| Vitamin C | Extensive removal of free radicals and repair of oxidized vitamin E bound to the cell membrane82 |

| Polypodium leucotomos | Inhibition of UV induced ROS generation, including superoxide anion30,83 |

| Lycopene | Carotenoid of greater biological action in the neutralization of singlet oxygen84 |

| Lutein | Carotenoid that protects the fibroblasts from UVA-induced oxidative action, also preventing the decrease of the antioxidant enzymes catalase and superoxide dismutase (SOD)85,86 |

| Resveratrol | Inhibition of UV-induced oxidative and mutagenic action to DNA87,88 |

| Epigallocatechin gallate (green tea) | Flavonoid with broad scavenging action of free radicals, inhibiting the production of ROS and lipid peroxidation products, in addition to protecting the endogenous antioxidative systems89,90 |

| Lipoic acid | Repair of endogenous antioxidant systems, free radical neutralizer91 |

| Delphinidin | Inhibition of lipid peroxidation and formation of 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG), marker of oxidative stress to DNA and carcinogenesis92 |

| Coenzyme Q10 | Reduction of the production of free radicals and regeneration of vitamin E; reduction of keratinocyte DNA damage and UVA-induced metalloproteinase production in the fibroblasts; reduction of mitochondrial oxidative damage43,93 |

* Information on the mechanism of action is restricted only to the antioxidant effect, although many of the cited molecules have other effects described.

CONCLUSION

The skin is the site of multiple oxidative reactions, neutralized by exogenous or endogenous enzymatic and non-enzymatic systems, in a complex but efficient, equilibrium. Interaction with the environment (characteristic of the integumentary system), as well as the peculiarities of its cells, especially epidermal cells (of great metabolic and proliferative activity), is largely responsible for this generation of reactive species. Any change in this balance may induce or aggravate dermatoses and the use of antioxidants may be of great value, if they are administered, orally and/or topically, rationally. Each molecule with antioxidant action has actions in certain sites and, therefore, the association of these molecules, in smaller doses, seems to be more efficient. In addition, associations allow administering concentrations closer to the physiological ones, which reduces toxicological risks and even of aggravation of imbalance of the antioxidant systems.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None

Study conducted at private clinic - São Paulo (SP), Brazil.

Financial support: none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Contassot E, Beer HD, French LE. Interleukin-1, inflammasomes, autoinflammation and the skin. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:w13590–w13590. doi: 10.4414/smw.2012.13590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pelle E, Mammone T, Maes D, Frenkel K. Keratinocytes act as a source of reactive oxygen species by transferring hydrogen peroxide to melanocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:793–797. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryan AS, Goldsmith LA. Nutrition and the skin. Clin Dermatol. 1996;14:389–406. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(96)00068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Droge W. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:47–95. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forman HJ, Fukuto JM, Miller T, Zhang H, Rinna A, Levy S. The chemistry of cellsignaling by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species and 4-hydroxynonenal. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;477:183–195. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Preedy VR. Handbook of diet, nutrition and the skin. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kohen R, Fanberstein D, Tirosh O. Reducing equivalents in the aging process. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1997;24:103–123. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4943(96)00744-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kvam E, Dahle J. Pigmented melanocytes are protected against ultraviolet-A-induced membrane damage. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:564–569. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pastore S, Korkina L. Redox Imbalance in T Cell-Mediated Skin Diseases. Mediators Inflamm. 2010;2010:861949–861949. doi: 10.1155/2010/861949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang H, Tindall DJ. Dynamic FoxO transcription factors. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:2479–2487. doi: 10.1242/jcs.001222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ristow M, Schmeisser S. Extending life span by increasing oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:327–336. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughes MC, Williams GM, Baker P, Green AC. Sunscreen and prevention of skin aging: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:781–790. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-11-201306040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sokoloski L, Borges M, Bagatin E. Lycopene not in pill, nor in natura has photoprotective systemic effect. Arch Dermatol Res. 2015;307:545–549. doi: 10.1007/s00403-015-1578-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rutkowski M, Grzegorczyk K. Adverse effects of antioxidative vitamins. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2012;25:105–121. doi: 10.2478/S13382-012-0022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Haaften RI, Evelo CT, Penders J, Eijnwachter MP, Haenen GR, Bast A. Inhibition of human glutathione S-transferase P1-1 by tocopherols and alpha-tocopherol derivatives. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1548:23–28. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(01)00211-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchel RE, McCann R. Vitamin E is a complete tumor promoter in mouse skin. Carcinogenesis. 1993;14:659–662. doi: 10.1093/carcin/14.4.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chachay VS, Kirkpatrick CM, Hickman IJ, Ferguson M, Prins JB, Martin JH. Resveratrol--pills to replace a healthy diet? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;72:27–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03966.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keller KL, Fenske NA. Uses of vitamins A, C, and E and related compounds in dermatology: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:611–625. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marini A, Jaenicke T, Grether-Beck S, Le Floc'h C, Cheniti A, Piccardi N. Prevention of polymorphic light eruption by oral administration of a nutritional supplement containing lycopene, β-carotene, and Lactobacillus johnsonii: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded study. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2014;30:189–194. doi: 10.1111/phpp.12093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lima XT, Alora-Palli MB, Beck S, Kimball AB. A double-blinded, randomized,controlled trial to quantitate photoprotective effects of an antioxidante combination product. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:29–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Addor FAS, Camarano P, Agelune CP. Increase in the minimum erythema dose level based on the intake of a vitamin supplement containing antioxidants. Surg Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;5:212–215. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krutmann J, Grewe M. Involvement of cytokines, DNA damage, and reactive oxygen intermediates in ultraviolet radiation-induced modulation of intercelular adhesion molecule-1 expression. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;105:67S–70S. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12316095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oresajo C, Yatskayer M, Galdi A, Foltis P, Pillai S. Complementary effects of antioxidants and sunscreens in reducing UV-induced skin damage as demonstrated by skin biomarker expression. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2010;12:157–162. doi: 10.3109/14764171003674455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freitas JV, Praça FS, Bentley MV, Gaspar LR. Trans-resveratrol and beta-carotene from sunscreens penetrate viable skin layers and reduce cutaneous penetration of UV-filters. Int J Pharm. 2015;484:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.02.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burns EM, Tober KL, Riggenbach JA, Kusewitt DF, Young GS, Oberyszyn TM. Differential effects of topical vitamin E and C E Ferulic® treatments on ultraviolet light B-induced cutaneous tumor development in Skh-1 mice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63809. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poljsak B, Dahmane R, Godic A. Skin and antioxidants. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2013;15:107–113. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2012.758380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schroeder P, Krutmann J. What is needed for a sunscreen to provide complete protection. Skin Therapy Lett. 2010;15:4–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Udompataikul M, Sripiroj P, Palungwachira P. An oral nutraceutical containing antioxidants, minerals and glycosaminoglycans improves skin roughness and fine wrinkles. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2009;31:427–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2494.2009.00513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonzalez S, Gilaberte Y, Philips N, Juarranz A. Fernblock, a nutriceutical with photoprotective properties and potential preventive agent for skin photoaging and photoinduced skin cancers. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12:8466–8475. doi: 10.3390/ijms12128466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garcia F, Pivel JP, Guerrero A, Brieva A, Martinez-Alcazar MP, Caamano-Somoza M, et al. Phenolic components and antioxidant activity of Fernblock, an aqueous extract of the aerial parts of the fern Polypodium leucotomos. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 2006;28:157–160. doi: 10.1358/mf.2006.28.3.985227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zastrow L, Groth N, Klein F, Kockott D, Lademann J, Ferrero L. UV, visible and infrared light. Which wavelengths produce oxidative stress in human skin? Hautarzt. 2009;60:310–317. doi: 10.1007/s00105-008-1628-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vandersee S, Beyer M, Lademann J, Darvin ME. Blue-violet light irradiation dose dependently decreases carotenoids in human skin, which indicates the generation of free radicals. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2015;2015:579675–579675. doi: 10.1155/2015/579675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alaluf S, Heinrich U, Stahl W, Tronnier H, Wiseman S. Dietary carotenoids contribute to normal human skin color and UV photosensitivity. J Nutr. 2002;132:399–403. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palombo P, Fabrizi G, Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Fluhr J, Roberts R, et al. Beneficial long-term effects of combined oral/topical antioxidant treatment with the carotenoids lutein and zeaxanthin on human skin: a double-blind, placebo-control study. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;20:199–210. doi: 10.1159/000101807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Younis Mel-B, Hasaneen MN, Abdel-Aziz HM. An enhancing effect of visible light and UV radiation on phenolic compounds and various antioxidants in broad bean seedlings. Plant Signal Behav. 2010;5:1197–1203. doi: 10.4161/psb.5.10.11978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akhalaya MY, Maksimov GV, Rubin AB, Lademann J, Darvin ME. Molecular action mechanisms of solar infrared radiation and heat on human skin. Ageing Res Rev. 2014;16:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fisher GJ, Voorhees JJ. Molecular mechanisms of photoaging and its prevention by retinoic acid: ultravioleta irradiation induces MAP kinase signal transduction cascades that induce AP-1 regulated matrix metalloproteinases that degrade human skin in vitro. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1998;3:61–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schroeder P, Lademann J, Darvin ME, Stege H, Marks C, Bruhnke S. Infrared Radiation-inducedmatrix metalloproteinase in human skin: implications for protection. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:2491–2497. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grether-Beck S, Marini A, Jaenicke T, Krutmann J. Effective photoprotection of human skin against infrared A radiation by topically applied antioxidants: results from a vehicle controlled.double-blind.randomized study. Photochem Photobiol. 2015;91:248–250. doi: 10.1111/php.12375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Horta C, Muller H. Steiner D, Addor FAZ. Envelhecimento cutâneo. Rio de Janeiro: AC Farmacêutica; 2014. Histologia do envelhecimento do sistema tegumentar; pp. 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Naylor EC, Watson RE, Sherratt MJ. Molecular aspects of skin aging. Maturitas. 2011;69:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gadaleta MN, Cormio A, Pesce V, Lezza AM, Cantatore P. Aging and mithocondria. Biochimie. 1998;80:863–870. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(00)88881-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beyer RE. The participation of coenzyme Q in free radical production and antioxidation. Free Radic Biol Med. 1990;8:545–565. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(90)90154-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blisnakov EG. Aging, mitochondria, and coenzyme QlO: the neglected relationship. Biochimie. 1999;81:1131–1132. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(99)00348-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuro-o M, Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, Kawaguchi H, Suga T, Utsugi T, et al. Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature. 1997;390:45–51. doi: 10.1038/36285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shibuya S, Kinoshita K, Shimizu T. Protective effects of vitamin C derivatives on skin atrophy caused by Sod1 deficiency. In: Preedy VR, editor. Handbook of diet, nutrition and the skin. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schagen SK, Zampeli VA, Makrantonaki E, Zouboulis CC. Discovering the link between nutrition and skin aging. Dermatoendocrinol. 2012;4:298–307. doi: 10.4161/derm.22876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Picardo M, Carrera M. New and experimental treatments of cloasma and other hypermelanoses. Dermatol Clin. 2007;25:353–362. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2007.04.012. ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sarkar R, Arora P, Garg VK, Sonthalia S, Gokhale N. Melasma update. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:426–435. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.142484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seçkin HY, Kalkan G, Bas Y, Akbas A, Önder Y, Özyurt H, Sahin M. Oxidative stress status in patients with melasma. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2014;33:212–217. doi: 10.3109/15569527.2013.834496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Azulay MM, Lacerda CAM, Perez MA, Filgueira AL, Cuzzi T. Vitamina C. An Bras Dermatol. 2003;78:265–274. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoshimura M, Watanabe Y, Kasai K, Yamakoshi J, Koga T. Inhibitory effect of an ellagic acid-rich pomegranate extract on tyrosinase activity and ultraviolet-induced pigmentation. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2005;69:2368–2373. doi: 10.1271/bbb.69.2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ni Z, Mu Y, Gulati O. Treatment of melasma with Pycnogenol. Phytother Res. 2002;16:567–571. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fuchs J, Huflejt ME, Rothfuss LM, Wilson DS, Carcamo G, Packer L. Acute efects of near ultraviolet and visible light on the cutaneous antioxidant defense system Photochem. Photobiol. 1989;50:739–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1989.tb02904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Katiyar SK, Mukhtar H. Green tea polyphenol (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate treatment to mouse skin prevents UVB-induced iniltration of leukocytes, depletion of antigen-presenting cells, and oxidative stress. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69:719–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cheeseman KH, Slater TF. An introduction to free radical biochemistry. Br Med Bull. 1993;49:481–493. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weber SU, Thiele JJ, Cross CE, Packer L. Vitamin C, uric acid, and glutathione gradients in murine stratum corneum and their susceptibility to ozone exposure. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:1128–1132. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Godic A, Poljsak B, Adamic M, Dahmane R. The Role of Antioxidants in Skin Cancer:Prevention and Treatment. Hindawi Publishing Corporation. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2014:860479–860479. doi: 10.1155/2014/860479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gao P, Zhang H, Dinavahi R, Li F, Xiang Y, Raman V, et al. HIF-dependent antitumorigenic effect of antioxidants in vivo. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:230–238. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stahl W, Krutmann J. Systemic photoprotection through carotenoids. Hautarzt. 2006;57:281–285. doi: 10.1007/s00105-006-1095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vanizor Kural B, Orem A, Cimsit G, Yandi YE, Calapoglu M. Evaluation of the atherogenic tendency of lipids and lipoprotein content and their relationships with oxidant-antioxidant system in patients with psoriasis. Clin Chim Acta. 2003;328:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(02)00373-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yildirim M, Inaloz HS, Baysal V, Delibas N. The role of oxidants and antioxidants in psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:34–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2003.00641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ormerod AD, Weller R, Copeland P, Benjamin N, Ralston SH, Grabowksi P, et al. Detection of nitric oxide and nitric oxide synthases in psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 1998;290:3–8. doi: 10.1007/s004030050268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Motor S, Ozturk S, Ozcan O, Gurpinar AB, Can Y, Yuksel R, et al. Evaluation of total antioxidant status, total oxidant status and oxidative stress index in patients with alopecia areata. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:1089–1093. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wagener FA, Carels CE, Lundvig DM. Targeting the redox balance in inflammatory skin conditions. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:9126–9167. doi: 10.3390/ijms14059126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fortes C, Mastroeni S, Melchi F, Pilla MA, Antonelli G, Camaioni D, et al. A protective effect of the Mediterranean diet for cutaneous melanoma. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37:1018–1029. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Philips N, Dulaj L, Upadhya T. Cancer cell growth and extracellular matrix remodeling mechanism of ascorbate; beneficial modulation by P. leucotomos. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:3233–3238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Akoglu G, Emre S, Metin A, Akbas A, Yorulmaz A, Isikoglu S, et al. Evaluation of total oxidant and antioxidant status in localized and generalized vitiligo. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:701–706. doi: 10.1111/ced.12054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sapuntsova SG, Lebed'ko OA, Shchetkina MV, Fleyshman MY, Kozulin EA, Timoshin SS. Status of free-radical oxidation and proliferation processes in patients with atopic dermatitis and lichen planus. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2011;150:690–692. doi: 10.1007/s10517-011-1224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grange PA, Weill B, Dupin N, Batteux F. Does inflammatory acne result from imbalance in the keratinocyte innate immune response? Microbes Infect. 2010;12:1085–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Emre S, Metin A, Demirseren DD, Akoglu G, Oztekin A, Neselioglu S, et al. The association of oxidative stress and disease activity in seborrheic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2012;304:683–687. doi: 10.1007/s00403-012-1254-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yesilova Y, Ucmak D, Selek S, Dertlioglu SB, Sula B, Bozkus F, et al. Oxidative stress index may play a key role in patients with pemphigus vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:465–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Guaratini T, Medeiros M HG, Colepicolo P. Antioxidantes na manutenção do equilibrio redox cutâneo: uso e avaliação de sua eficácia. Quim. Nova. 2007;30:206–213. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sadowska-Bartosz I, Bartosz G. Effect of antioxidants supplementation on aging and longevity. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:404680–404680. doi: 10.1155/2014/404680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rizwan M, Rodriguez-Blanco I, Harbottle A, Birch-Machin MA, Watson RE, Rhodes LE. Tomato paste rich in lycopene protects against cutaneous photodamage in humans in vivo: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:154–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shao A, Hathcock JN. Risk assessment for the carotenoids lutein and lycopene. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2006;45:289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Martínez ME, Jacobs ET, Baron JA, Marshall JR, Byers T. Dietary supplements and cancer prevention: balancing potential benefits against proven harms. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:732–739. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Matsui MS, Hsia A, Miller JD, Hanneman K, Scull H, Cooper KD, et al. Non-sunscreen photoprotection: antioxidants add value to a sunscreen. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2009;14:56–59. doi: 10.1038/jidsymp.2009.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lademann J, Vergou T, Darvin ME, Patzelt A, Meinke MC, Voit C, et al. Influence of Topical, Systemic and Combined Application of Antioxidants on the Barrier Properties of the Human Skin. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2016;29:41–46. doi: 10.1159/000441953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Krol ES, Kramer-Stickland KA, Liebler DC. Photoprotective actions of topically applied vitamin E. Drug Metab Rev. 2000;32:413–420. doi: 10.1081/dmr-100102343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.L. Packer L, Valacchi G. Antioxidants and the response of skin to oxidative stress: vitamin E as a key indicator. Skin Pharmacol Appl Skin Physiol. 2002;15:282–290. doi: 10.1159/000064531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McArdle F, Rhodes LE, Parslew R, Jack CI, Friedmann PS, Jackson MJ. UVR-induced oxidative stress in human skin in vivo: effects of oral vitamin C supplementation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:1355–1362. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gombau L, García F, Lahoz A, Fabre M, Roda-Navarro P, Majano P, et al. Polypodium leucotomos extract: Antioxidant activity and disposition. Toxicol In Vitro. 2006;20:464–471. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ascenso A, Pedrosa T, Pinho S, Pinho F, de Oliveira JM, Cabral Marques H, et al. The Effect of Lycopene Preexposure on UV-B-Irradiated Human Keratinocytes. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:8214631–8214631. doi: 10.1155/2016/8214631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.O'Connor I, O'Brien N. Modulation of UVA light-induced oxidative stress by beta-carotene, lutein and astaxanthin in culturedfibroblasts. J Dermatol Sci. 1998;16:226–230. doi: 10.1016/s0923-1811(97)00058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Astner S, Wu A, Chen J, Philips N, Rius-Diaz F, Parrado C, et al. Dietary lutein/zeaxanthin partially reduces photoaging and photocarcinogenesis in chronically UVB-irradiated Skh-1 hairless mice. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;20:283–291. doi: 10.1159/000107576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ndiaye M, Philippe C, Mukhtar H, Ahmad N. The Grape Antioxidant Resveratrol for Skin Disorders: Promise,Prospects, and Challenges. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;508:164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chow HH, Garland LL, Hsu CH, Vining DR, Chew WM, Miller JA, et al. Resveratrol modulates drug- and carcinogen-metabolizing enzymes in a healthy volunteer study. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3:1168–1175. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Katiyar SK. Skin photoprotection by green tea: antioxidant and immunomodulatory efects. Curr Drug Targets Immune Endocr Metabol Disord. 2003;3:234–242. doi: 10.2174/1568008033340171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gensler HL, Timmermann BN, Valcic S, Wächter GA, Dorr R, Dvorakova K, et al. Prevention of photocarcinogenesis by topical administration of pure epigallocatechin gallate isolated from green tea. Nutr Cancer. 1996;26:325–335. doi: 10.1080/01635589609514488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Biewenga GP, Haenen GR, Bast A. The pharmacology of the antioxidant lipoic acid. Gen Pharmacol. 1997;29:315–331. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(96)00474-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Watson RR, Schönlau F. Nutraceutical and antioxidant effects of a delphinidin-rich maqui berry extract Delphinol®: a review. Minerva Cardioangiol. 2015;63:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Inui M, Ooe M, Fujii K, Matsunaka H, Yoshida M, Ichihashi M. Mechanisms of inhibitory efects of CoQ10 onUVB- induced wrinkle formation in vitro and in vivo. Biofactors. 2008;32:237–243. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520320128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]