Significance

Plants often grow at high plant densities where they risk being shaded by surrounding plants. Neighbors are detected through changes in the composition of reflected light, and plants respond to such changes by growing their photosynthetic organs away from their competitors. This research shows that Arabidopsis plants first detect these light cues in the tips of their leaves and that this information then is transmitted through the mobile plant hormone auxin to the very base of the organ, where it induces an upward leaf movement response. 3D computational models show that this spatial separation in signal detection and response is adaptive for plant performance in dense stands.

Keywords: leaf movement, auxin, phytochrome, functional-structural plant model, shade avoidance

Abstract

Vegetation stands have a heterogeneous distribution of light quality, including the red/far-red light ratio (R/FR) that informs plants about proximity of neighbors. Adequate responses to changes in R/FR are important for competitive success. How the detection and response to R/FR are spatially linked and how this spatial coordination between detection and response affects plant performance remains unresolved. We show in Arabidopsis thaliana and Brassica nigra that localized FR enrichment at the lamina tip induces upward leaf movement (hyponasty) from the petiole base. Using a combination of organ-level transcriptome analysis, molecular reporters, and physiology, we show that PIF-dependent spatial auxin dynamics are key to this remote response to localized FR enrichment. Using computational 3D modeling, we show that remote signaling of R/FR for hyponasty has an adaptive advantage over local signaling in the petiole, because it optimizes the timing of leaf movement in response to neighbors and prevents hyponasty caused by self-shading.

Plant canopies have pronounced gradients of light intensity between the top and bottom because leaves shade one another (1). As a consequence of the clustering of leaves, light intensities also vary horizontally. Because light drives photosynthesis, this variable light intensity creates selection pressure for plants to position their leaves for optimal light capture. Leaves do not absorb all wavelengths of the incoming light equally, and therefore light quality also differs vertically and horizontally in canopies (1–3) and even across the surface of individual leaves (4). Leaves preferentially absorb red (R) (λ = 600–700 nm) and blue (B) (λ = 400–500 nm) light for photosynthesis while reflecting most of the far-red (FR) (λ= 700–800 nm) light. This preference leads to a relative enrichment of FR light (low R/FR) in the local vicinity of leaves, a signal of neighbor proximity (5).

Low R/FR is sensed by phytochrome photoreceptors, mainly phytochrome B (phyB), and induces upward leaf movement (hyponasty) through differential petiole growth and elongation of stems and petioles, thus bringing the leaves higher, toward the more illuminated parts of the canopy (6–8). Plants are modular organisms, and such shade-avoidance responses could thus be restricted to the specific modules that sense shade cues (9–11). Although spatial separation was shown recently for hypocotyl elongation in small Brassica rapa seedlings (12), only more established plants are large enough to experience light quality heterogeneity over the plant body. It is unknown whether responses to a low R/FR in relatively mature Arabidopsis plants act locally or integrate detection from different plant parts.

A low R/FR inactivates phytochromes, leading to the accumulation of active PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR (PIF) transcription factors, notably PIF4, PIF5, and PIF7, that trigger expression of growth-promoting genes (13), including auxin signaling and biosynthesis genes (14–17) such as YUCCAs that encode enzymes in tryptophan-dependent auxin synthesis downstream of TAA1 (TRYPTOPHAN AMINOTRANSFERASE OF ARABIDOPSIS 1) (18–20). Auxin biosynthesis in seedlings occurs mostly in the cotyledons, and polar auxin transport to the hypocotyl subsequently induces elongation in low R/FR (12). Within a leaf, polar auxin transport also spatially relays signals (21) and is required for low R/FR-induced petiole elongation (18) and thus for shade avoidance (22, 23).

We hypothesize that a spatial separation of R/FR detection and auxin-dependent growth response enables plants to deal with the spatially heterogenic light climate in dense stands where R/FR responses are functional. Here we show that leaf growth responses to FR enrichment occur exclusively within the FR-exposed leaf, but within the leaf there is spatial separation: hyponasty occurs exclusively in response to remote FR enrichment at the leaf tip, whereas petiole length responds to FR enrichment only when sensed at the petiole itself. Integrating transcriptomics, physiology, and genetics, we show that FR enrichment at the leaf tip induces hyponasty through auxin synthesis and transport in a PIF-dependent manner. Using a computational 3D plant model (24–26), we demonstrate why sensing R/FR at the lamina tip to control leaf angles is functionally superior to sensing it in the petiole.

Results

Site of R/FR Perception Determines Hyponasty vs. Petiole Elongation.

We exposed different leaf regions of Arabidopsis thaliana Col-0 to a FR irradiation spotlight 3.5 mm in diameter (Fig. S1A) and measured the effect on petiole angle and elongation. Supplemental FR light to the tip [white light (W)+FRtip] of the lamina induced hyponasty, whereas treatment of the petiole itself (W+FRpetiole) did not elicit any hyponasty (Fig. 1 A and B). W+FRtip triggered the strongest hyponastic response of all local supplemental FR treatments, similar to hyponasty in the whole-plant low R/FR (W+FRwhole) condition. Only the supplemental FR-treated leaf responded; no systemic response was observed with the local treatments (Fig. S1 B–E). In Brassica nigra we found similar responses; petiole hyponasty was induced in the W+FRtip condition, and petiole elongation was induced mainly by W+FRpetiole and only marginally (not significant) by W+FRtip (Fig. S2). Reciprocally, an R spotlight on one leaf of Arabidopsis plants under W+FRwhole conditions reduced leaf angle only in the R-treated leaf (Fig. 1C), corroborating the observation that the response is local to the treated leaf. Although W+FRpetiole induced no hyponasty, it induced maximal petiole elongation (similar to W+FRwhole and W+FRpetiole+tip), whereas W+FRtip did not elicit any petiole elongation (Fig. 1D). Plants treated with W+FRtip showed supplemental FR-induced growth only in the abaxial side of the most basal petiole section. The area contributing to hyponasty extends slightly beyond the area of the 3.5-mm spotlight on the tip, as was evidenced by moving the spotlight on the tip-most half of the lamina (Fig. S3 A and B). W+FRwhole treatment induced elongation throughout the petiole on both the abaxial and adaxial sides (Fig. S3C).

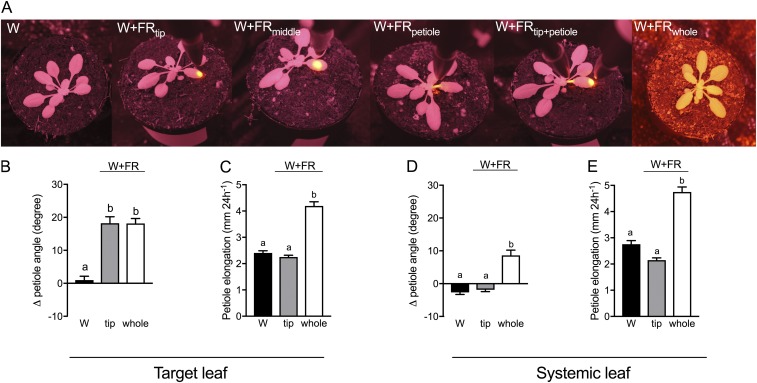

Fig. S1.

Supplemental FR treatment does not induce hyponasty or petiole elongation in systemic leaves. (A) IR photographs illustrating plants in the different light treatments: white light (W), white light with supplemental FR through a 3.5-mm spot (observed as bright yellow spot) on the lamina tip (W+FRtip), the middle of the lamina (W+FRmiddle), the petiole (W+FRpetiole), the lamina tip and petiole (W+FRtip+petiole), and whole-plant FR (W+FRwhole). (B and C) The differential petiole angle (B) and petiole elongation (C) of the target leaf in W, W+FRtip, and W+FRwhole conditions. (D and E) The differential petiole angle (D) and petiole elongation (E) of the systemic leaf under the same light conditions. Data represent the mean ± SE (n = 10). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, P < 0.05).

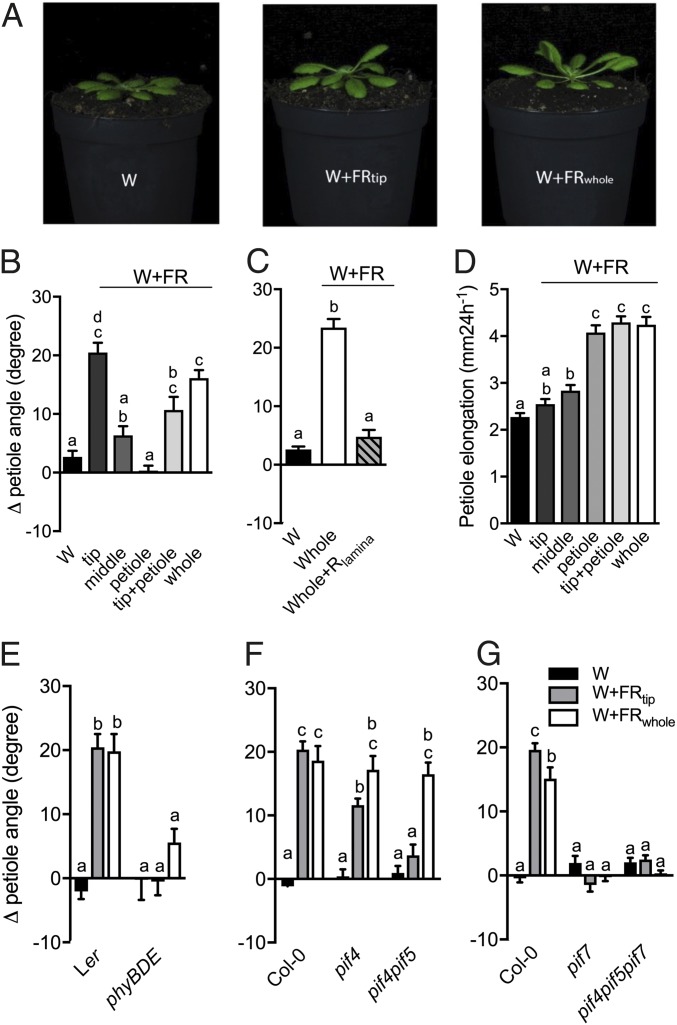

Fig. 1.

Local FR treatment can induce different shade-avoidance responses in a PIF-dependent manner. (A) Representative photographs of Col-0 plants treated with white light (W), white light with supplemented FR light to the lamina tip (W+FRtip), or white light with supplemented FR to the whole plant (W+FRwhole). (B) Differential petiole angle for plants exposed to 24-h white light control conditions (W) and to supplemented FR light to the lamina tip (tip), the middle of the lamina (middle), the entire petiole (petiole), the lamina tip plus the petiole (tip+petiole), and the whole plant (whole). (C) Differential petiole angles after 24-h exposure to W, W+FRwhole, and W+FRwhole with supplemented R light at the lamina (W+FRwhole+Rlamina). (D) Petiole elongation response to 24-h exposure to the light treatments in B. (E–G) Differential petiole angle of Ler and phyBphyDphyE (E), Col-0, pif4, and pif4pif5 (F), and Col-0, pif7, and pif4pif5pif7 (G) after 24 h of growth in white light (W) or in white light with supplemented FR to the lamina tip (W+FRtip) or to the whole plant (W+FRwhole). Data represent mean ± SE; n = 10 in B, C, F, and G; n = 18 or 19 in E and F. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (one-way ANOVA in B–D and two-way ANOVA in E–G with Tukey’s post hoc test; P < 0.05).

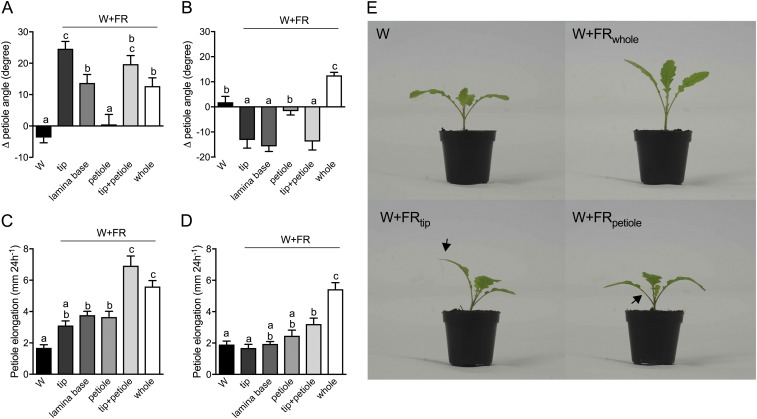

Fig. S2.

Tissue-specific FR perception in B. nigra induces hyponastic and elongation responses. B. nigra seedlings were grown in a 16/8-h light/dark cycle with 110–150 μmol⋅m−2⋅s−1 PAR, R/FR 2.3, 20 °C and 70% relative humidity. The petiole angle and petiole elongation of the first two leaves of 14-d-old Brassica seedlings were measured during 24 h of exposure to different light treatments (cotyledons were removed 2 d before the treatment). Plants were grown in white light (W) or one leaf (referred to as the “target leaf”) was treated with supplemental FR light applied to the lamina tip (tip), lamina base, petiole, lamina tip plus petiole (tip+petiole), or whole plant (whole). (A–D) Data show the change in the petiole angle of the target leaf (A) and systemic leaf (B) and the petiole elongation of the target leaf (C) and the systemic leaf (D). Data represent the mean ± SE (n = 10). Different letters represent statistically significant differences (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test; P < 0.05). (E) Representative photographs of the B. nigra plants in white light (W), in white light with supplemental FR for the whole plant (W+FRwhole), and in white light with supplemental FR light at the lamina tip (W+FRtip) or at the petiole (W+FRpetiole) of the left leaf. Black arrows indicate the area (lamina tip and petiole, respectively) treated with supplemental FR.

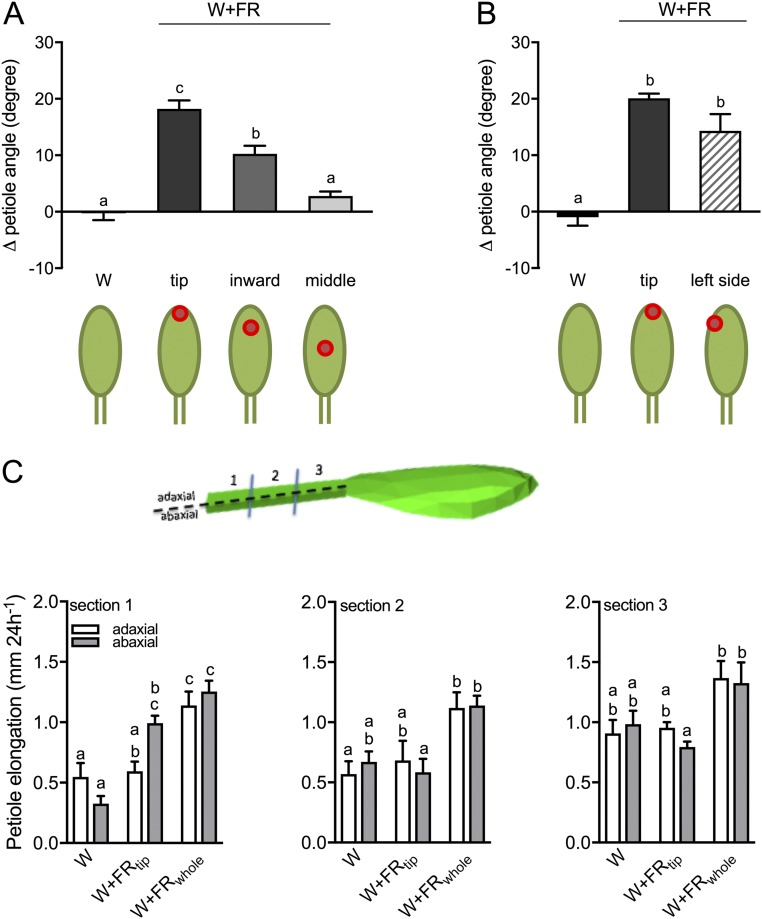

Fig. S3.

FR perception in the lamina tip induces the maximal hyponastic response through differential cell growth in the abaxial side of the petiole base. (A and B) The differential petiole angle of Col-0 WT plants in white light (W) (A and B) and in white light with supplemental FR at different spots on the lamina tip, including the very tip (tip) (A and B), between the lamina tip and the middle of the lamina (inward) (A), in the middle of the lamina (middle) (A), and on the left side of the lamina tip (B). Cartoons bellow the graphs illustrate the areas irradiated; supplemental FR light is indicated as a red spot. (C) Elongation of the adaxial (white bars) and abaxial (gray bars) side in three sections of the petiole (see leaf drawing) in the W, W+FRtip, and W+FRwhole conditions. Data represent mean ± SE; n = 14 in A and n = 7 in B and C. Different letters represent statistically significant differences (one-way ANOVA in A and B or two-way ANOVA in C with Tukey’s post hoc test; P < 0.05).

FR Enrichment of Lamina Tip-Induced Hyponasty Relies on PIFs.

The hyponastic response to W+FRtip was absent in the phyBphyDphyE triple mutant, confirming that the response is a phytochrome response (Fig. 1E). We therefore studied the involvement of the key PIFs that regulate established shade-avoidance responses. Although the pif4 mutant showed only a very mild reduction of the response to W+FRtip, the pif4pif5 double-knockout mutant showed no response at all. Interestingly, both the pif4 and pif4pif5 mutants responded normally to W+FRwhole (Fig. 1F), whereas pif7 and pif4pif5pif7 showed a severe reduction of hyponasty under both W+FRtip and W+FRwhole conditions (Fig. 1G). These data indicate that PIF4, PIF5, and PIF7 contribute to supplemental FR-induced hyponasty.

Transcriptome Analysis at the Suborgan Level Identifies Auxin Signatures.

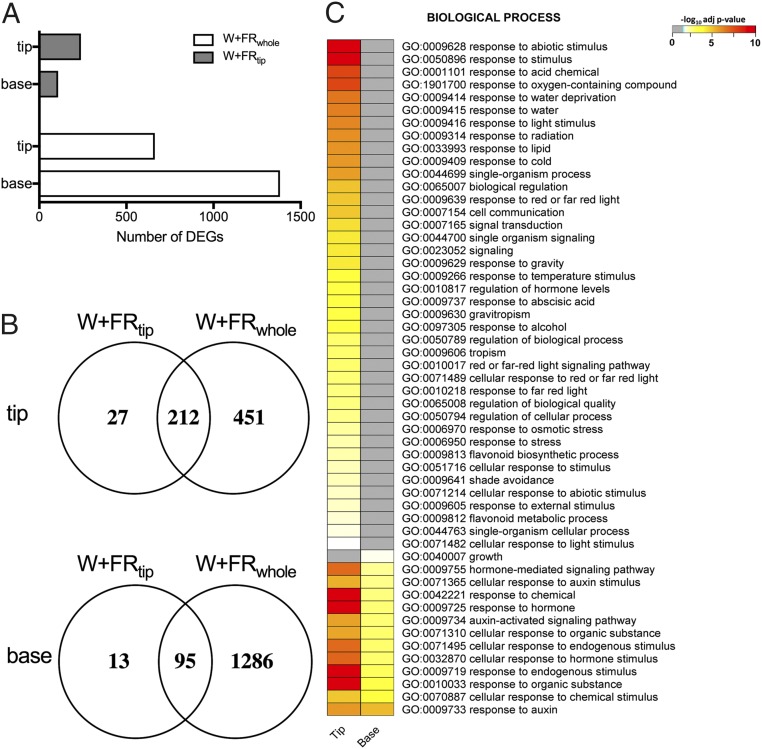

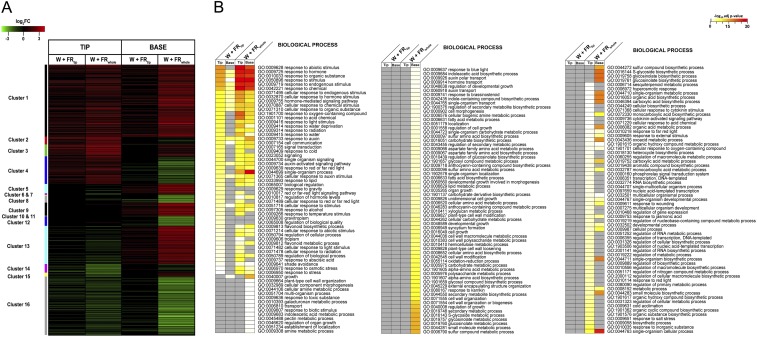

A transcriptome analysis on the lamina tip and petiole base revealed more differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with W+FRwhole than with W+FRtip treatment in both tissues and more DEGs in the lamina tip than in the petiole base under W+FRtip treatment (Fig. 2A and Dataset S1). Most DEGs in the W+FRtip condition were also expressed in the respective tissues under the W+FRwhole condition (Fig. 2B and Fig. S4A) but with higher log2 fold changes (log2FCs). Gene Ontology (GO) analysis for the genes common to the two tissues revealed high representation of auxin-related processes (Fig. 2C and Fig. S4B), and this finding was confirmed by hormonometer (27) analysis (Fig. S5A). Indeed, many DEGs in our transcriptome data were previously shown to be auxin regulated (Fig. S5 B–D lists common and treatment-specific genes) (28). PIF7 transcript levels were higher in the lamina tip than in the petiole base, whereas PIF4 and PIF5 are expressed equally in the two areas (Fig. S5E).

Fig. 2.

Comparative analysis of W+FRtip- and W+FRwhole-induced transcriptome responses in the lamina tip and the petiole base. (A) Number of DEGs in the lamina tip and the petiole base. (B) Venn diagrams illustrate the DEGs common to the two FR treatments in the lamina tip and the petiole base. (C) GO enrichment analysis for the genes common to the W+FRtip and W+FRwhole conditions for each of the two tissues.

Fig. S4.

Transcriptome analysis of the lamina tip and petiole base in the W+FRtip and W+FRwhole conditions. (A) DEGs in the lamina tip and petiole base in response to W+FRtip and W+FRwhole light treatment (adjusted P value ≤ 0.01 and log2FC >1 or <1), clustered based on fold change and direction (up/down) of regulation. (B) GO enrichment analysis for the lamina tip and petiole based on W+FRtip and W+FRwhole conditions. The yellow–red color scale denotes the significance of the GO terms; gray indicates the GO term is not significantly enriched in that specific treatment × tissue combination.

Fig. S5.

Hormone-associated transcript patterns in the microarray data of the petiole base and lamina tip under W+FRtip and W+FRwhole treatments. (A) Hormonometer analysis of the lamina tip and petiole base transcriptome (27). (B) Heatmap representation of the expression levels of DEGs that are associated with auxin and are shared (common) in the two tissue types W+FRtip and W+FRwhole conditions. (C and D) Heatmaps showing differentially expressed auxin-related genes in the lamina tip (C) and petiole base (D) that are exclusive to either the W+FRtip or the W+FRwhole condition. The heatmaps in B, C, and D are based on IAA-induced transcripts in ref. 28. (E) The intensity of PIF4, PIF5, and PIF7 in the microarray data of the lamina tip and petiole base in W light. ns, not significant. Data are means ± SE, n = 3. ns, no significant difference. **P < 0.01, paired Student's t test.

Auxin Regulates PIF-Dependent Hyponasty Induced by Supplemental FR.

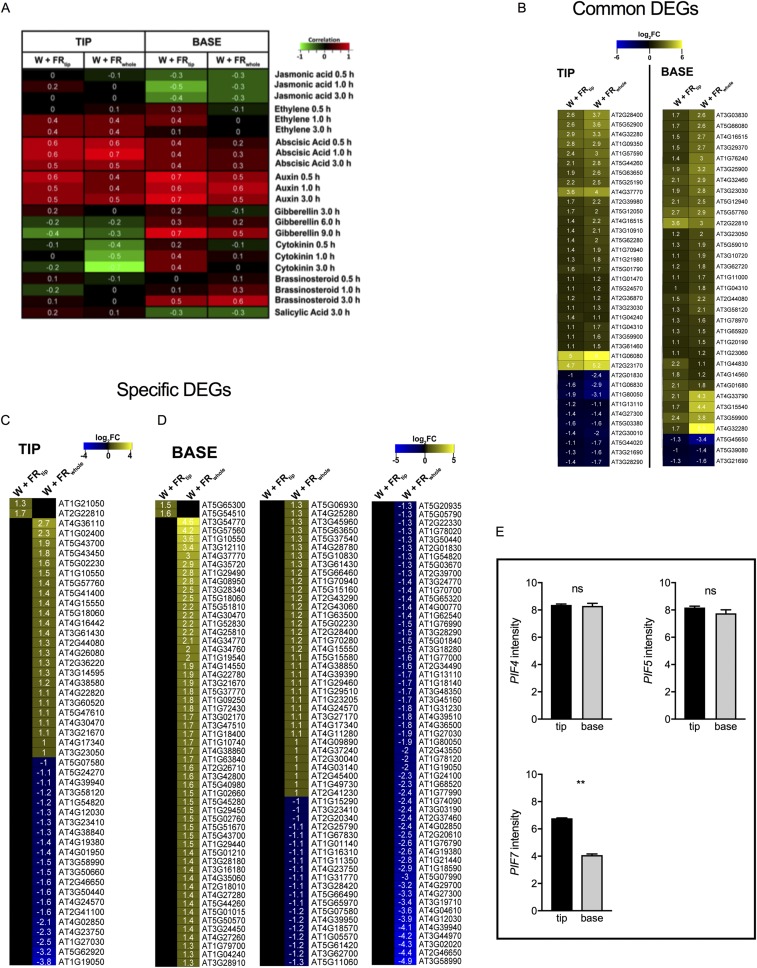

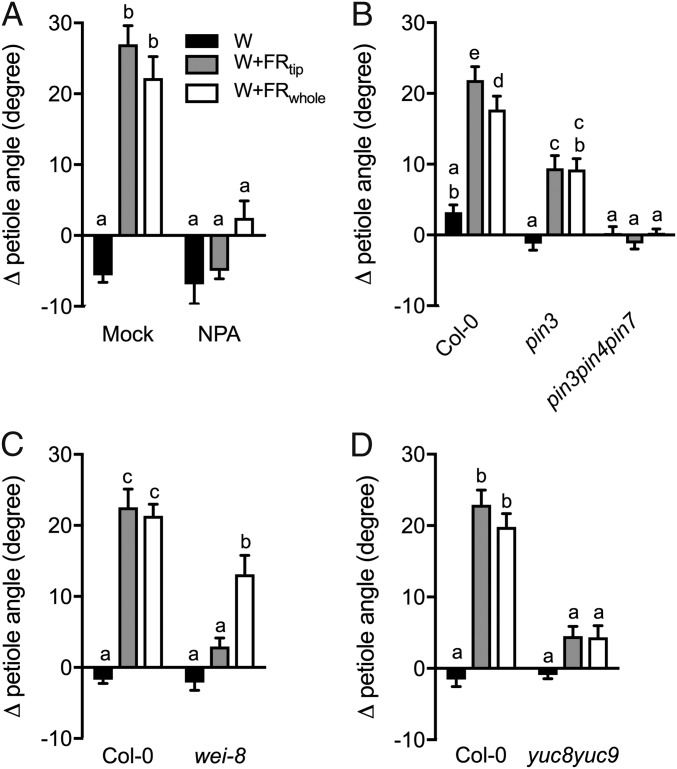

Given the clear transcriptome auxin signatures, we investigated whether auxin regulates FR-induced hyponasty. Localized application of the auxin transport inhibitor 1-naphtylphthalamic acid (NPA) to the lamina tip fully abolished hyponasty in both supplemental FR treatments, confirming that auxin from the lamina tip is required for hyponasty (Fig. 3A and Fig. S6A). Consistently, the auxin efflux mutant pin3 showed a reduced response, and the pin3pin4pin7 triple mutant completely lost responsiveness to FR enrichment (Fig. 3B). The auxin biosynthesis mutant wei8 (which is deficient in WEI8/TAA1/SAV3) had no response to W+FRtip but retained some responsiveness to W+FRwhole (Fig. 3C). The yuc8 and yuc9 auxin biosynthesis mutants had marginally reduced or not reduced hyponastic responses to supplemental FR (Fig. S6B), but the yuc8yuc9 double-knockout mutant lacked any hyponastic response to either of the supplemental FR treatments (Fig. 3D). Importantly, expression of YUC8 and YUC9 in Col-0 plants was induced in the lamina tip but not in the petiole base upon W+FRtip, and this induction was PIF7 dependent. These YUC genes were also induced in the petiole base under W+FRwhole exposure; this induction was PIF7 dependent for YUC9 but not for YUC8 (Fig. 4 A and B). PIN3 transcripts also were induced by both W+FRtip and W+FRwhole in the tip and by W+FRwhole in the base in a mostly PIF7-dependent manner (Fig. 4C), whereas an independent shade marker, PIL1, was less strongly PIF7 dependent (Fig. 4D). Collectively, these data suggest that the function of PIF7 may be to induce auxin biosynthesis and transport in the lamina tip in W+FRtip conditions.

Fig. 3.

Auxin biosynthesis and transport are required for hyponasty. (A) Differential petiole angles in response to different light conditions with exogenous application of one droplet of 50-μM NPA or a mock solution to the lamina tip. (B–D) Differential petiole angles of auxin transport mutants (pin3 and pin3pin4pin7) (B) and biosynthesis mutants (wei-8 in C and yuc8yuc9 in D) in three different light conditions. Data were collected after 24 h of exposure to W, W+FRtip, or W+FRwhole conditions. Data represent mean ± SE; n = 7–10. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test; P < 0.05).

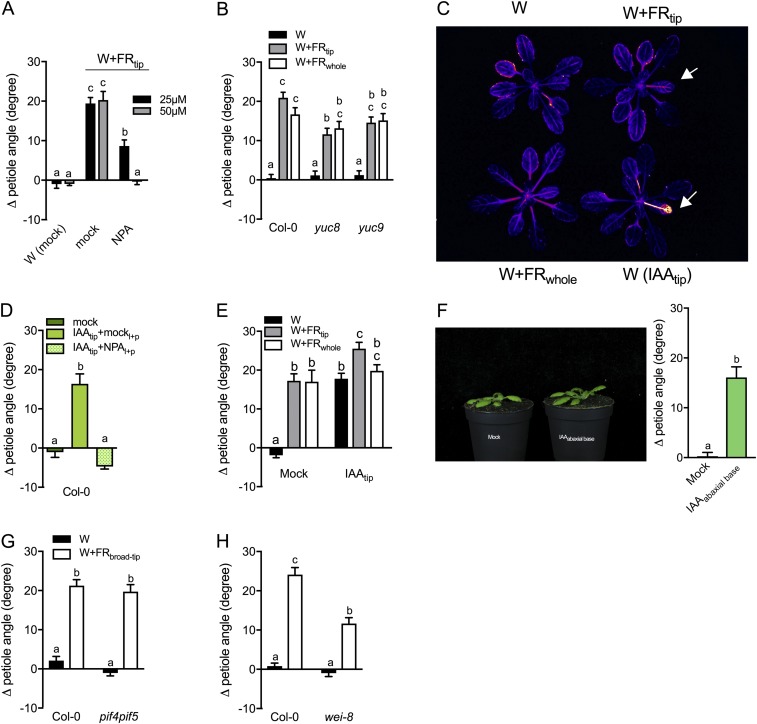

Fig. S6.

The importance of auxin in the induction of hyponasty. (A) Differential petiole angle response after exogenous application of different NPA concentrations to the lamina tip under W and W+FRtip conditions. (B) Differential petiole angle of auxin biosynthesis gene mutants (yuc8 and yuc9) under W, W+FRtip, and W+FRwhole conditions. (C) Luciferase luminescence of the auxin reporter line DR5:LUC on the adaxial side under W (Upper Left), W+FRtip (Upper Right), W+FRwhole (Lower Left), and W with exogenous application of 30 μM IAA to the lamina tip [W (IAAtip)] (Lower Right). White arrows indicate the treated leaf. (D) Differential petiole angle of Col-0 WT plants upon the application of IAA (30 μM) at the lamina tip in the presence (IAAtip + NPAl+p) or in the absence (IAAtip + mockl+p) of 50 μM of NPA in the petiole–lamina junction in W light. (E) Differential petiole angle of Col-0 WT plants under W, W+FRtip, and W+FRwhole conditions after the application of 30 μM IAA or mock to the lamina tip. (F) Hyponastic response in Col-0 WT plants to the application of exogenous auxin to the abaxial side of the petiole base in W light (IAAabaxial base) versus mock control. (G and H) Differential petiole angle of pif4pif5 (G) and wei8-1 (H) mutants under W light (black bars) and supplemental FR light (white bars) in a broad (7.5-mm) spot (rather than the regular 3.5-mm spot) on the lamina tip (W+FRbroad tip). Data represent the mean ± SE; n = 6 in A; n = 10 in B–E; n = 18 in F; and n = 14 in G and H. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (one-way ANOVA in D or two-way ANOVA in A, B, E, G, and H) with Tukey’s post hoc test or with a paired Student’s t test in F; P < 0.05.

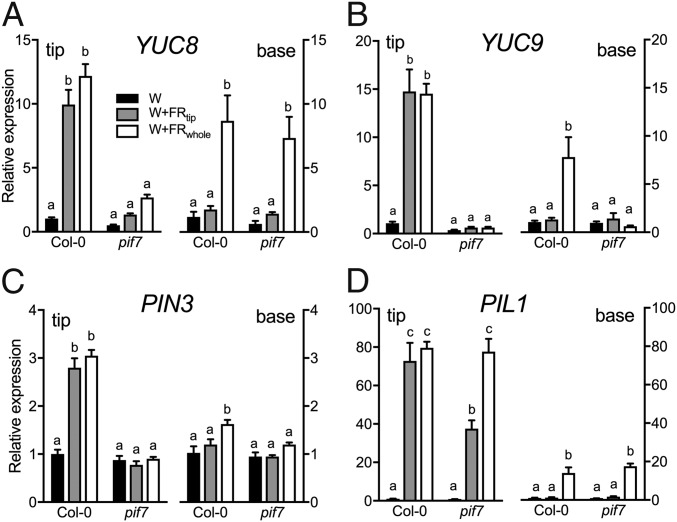

Fig. 4.

Relative expression of three auxin-related genes and a shade-avoidance marker in two tissues. Relative expression of the auxin biosynthesis genes YUC8 (A) and YUC9 (B), the auxin efflux carrier PIN3 (C), and the shade-avoidance marker PIL1 (D) in the lamina tip and petiole base tissue of Col-0 WT and pif7 mutant plants after 5 h in W, W+FRtip, or W+FRwhole conditions. Data represent the mean ± SE; n = 4. Different letters indicate organ-specific statistically significant differences (two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test; P < 0.05).

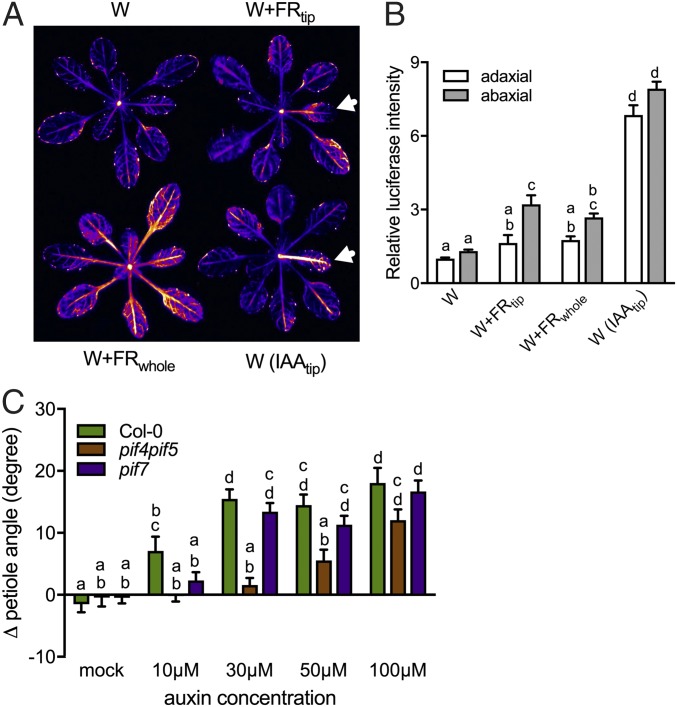

We visualized auxin activity with the DR5:LUC auxin reporter and observed clear luciferase induction in the abaxial but not the adaxial side of petiole after 7 h in W+FRtip (Fig. 5 A and B). Luciferase activity was increased almost everywhere in W+FRwhole-exposed rosettes and was much stronger on the abaxial side than on the adaxial side (Fig. 5A and Fig. S6C). Exogenous application of a small (5-μL) droplet of 30 μM indole 3-acetic acid (IAA) at the lamina tip resulted in massive LUC reporter induction (Fig. 5 A and B and Fig. S6C) and also induced pronounced hyponasty (Fig. 5C and Fig. S6 D and E). IAA-induced hyponasty was abolished when NPA was applied to the lamina–petiole junction (Fig. S6D), confirming that IAA must be transported from the lamina to the petiole base to induce hyponasty there. Consistently, applying IAA directly to the abaxial side of the petiole base to bypass this pathway readily induced hyponasty (Fig. S6F). If the pif7 mutant lacks a W+FRtip-induced hyponasty because of its failure to induce YUCCAs, it should be able to respond to exogenous IAA treatment of the lamina tip. Indeed, pif7 responds to IAA, although slightly less than in WT plants at low concentrations (Fig. 5C; maximal at 30 μM IAA). Interestingly, the pif4pif5 mutant displayed considerably reduced responsiveness to exogenous IAA, requiring at least 100 μM exogenous IAA for maximal hyponasty (Fig. 5C). In the W+FRwhole condition, a larger section of leaf tip tissue than in the W+FRtip condition is triggered by FR to produce IAA, likely increasing auxin levels. Indeed, illuminating a leaf tip area slightly larger than the 3.5-mm spotlight triggered hyponasty in the pif4pif5 mutant (Fig. S6G), as did very high concentrations of IAA (Fig. 5C). Illuminating a slightly larger leaf tip area with supplemental FR also restored some hyponasty in the auxin-underproducing wei8-1 mutant, similar to that seen in W+FRwhole conditions (Fig. S6H).

Fig. 5.

Supplemental FR and localized IAA control auxin dynamics for leaf hyponasty. (A) Luciferase luminescence of the DR5:LUC auxin reporter on the abaxial side in W (Upper Left), W+FRtip (Upper Right), W+FRwhole (Lower Left), and W with the exogenous application of one droplet of 30-μΜ IAA in the lamina tip [W(IAAtip), Lower Right]. White arrows indicate the treated leaf in localized treatments. (B) Quantification of relative luciferase intensity on the adaxial (white bars) and abaxial (gray bars) side of the petiole after exposure to W, W+FRtip, W+FRwhole, or W(IAAtip). Intensity values were expressed relative to those measured for the adaxial sides of control W petioles. (C) Differential petiole angle of Col-0 WT and the pif4pif5 and pif7 mutants 23 h after exogenous application of different IAA concentrations in the lamina tip. Data represent mean ± SE; n = 5 in B; n = 14 in C. Different letters indicate significant differences (two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test; P < 0.05).

Using R/FR Sensing in the Lamina Tip for Hyponasty Is Adaptive.

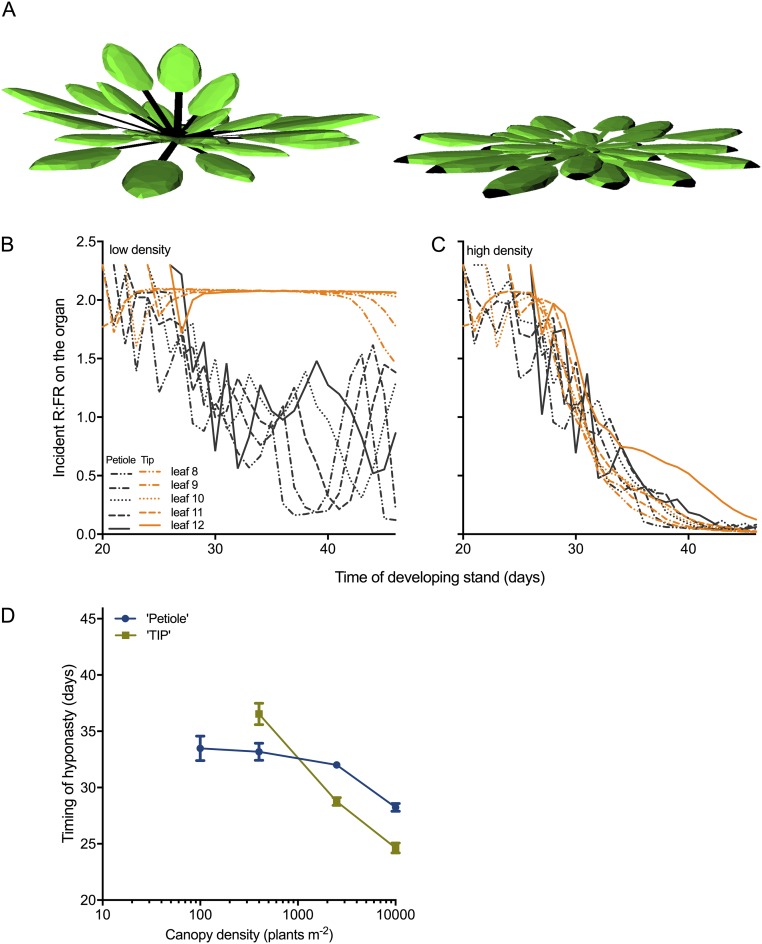

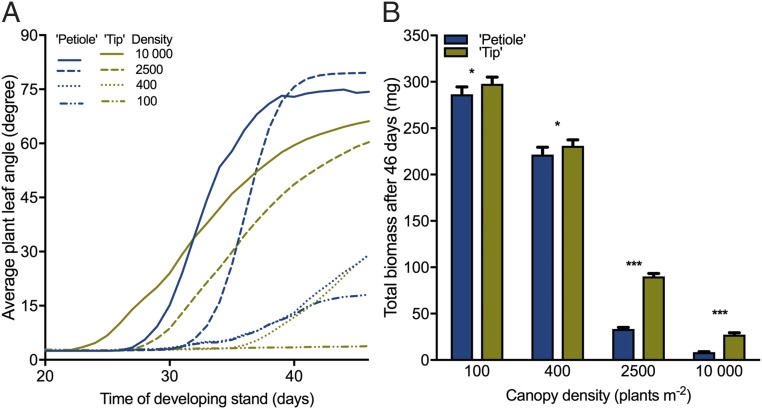

Using our recently validated functional–structural plant (FSP) model of Arabidopsis rosettes, we determined the dynamics and consequences of incident R/FR on the petiole and lamina tip (Fig. S7A) in plants growing in low and high density. At low density without competition, our simulations show a decreasing R/FR around the petioles, because of self-shading by newly developed leaves, whereas the R/FR at the tip remained constant (Fig. S7B). Simulations at high density showed that neighboring plants caused a strong decrease in the R/FR at the lamina tip (Fig. S7C). Next, we simulated plant growth in 50–50% checkerboard designs of mixtures of plants sensing R/FR at the lamina tip (“Tip plants”) and plants sensing R/FR at the petiole (“Petiole plants”) at different canopy densities. Plants approach their neighbors later at low density than at high density, and consequently hyponasty is induced later at low density than at high density when R/FR is sensed at the tip (Fig. 6 A and Fig. S7D). However, when sensing R/FR at the petiole, plants induced hyponasty even without interaction with neighbors at low density (100 plants/m2) and had a delayed response to neighbors at high density (2,500 and 10,000 plants/m2) (Fig. 6A). Raising leaves too early reduces light interception, and raising them too late results in neighbor shade. This neighbor shade directly determines light absorption, which drives carbon accumulation through photosynthesis. Accordingly, when competing with each other, virtual Petiole plants accumulate less biomass than Tip plants (Fig. 6B), thus showing the adaptive significance of using R/FR input from the lamina tip for hyponasty.

Fig. S7.

Tissue-specific incident R/FR and the timing of hyponasty in different plant densities simulated through FSP modeling. (A) Virtual representation of two simulated Arabidopsis plants growing at low density (100 plants/m2). Two plant types were simulated that used the R/FR at the petiole (Left) or at the lamina tip (Right) to induce hyponasty, as identified by black coloring of the organ part. The simulated plant that used the petiole R/FR as input for hyponasty shows that leaves become hyponastic through self-shading by younger leaves. (B and C) Incident R/FR at petiole (gray traces) and tip (orange traces) of leaves 8–12 during plant development at low density (B) or at high density (2,500 plants/m2) (C). In these simulations, plants did not become hyponastic. (D) Timing of hyponasty in relation to canopy density for two plant types that use the petiole (blue trace) or the lamina tip (yellow trace) as a R/FR-detection organ to induce hyponasty. Data represent the mean ± SD; n = 10.

Fig. 6.

Tissue-specific R/FR perception affects the performance of plants growing in stands with different densities, as found through FSP modeling. (A) Mean leaf angle for plant types using the petiole (blue traces) or the lamina tip (yellow traces) as the R/FR-detecting organ for inducing hyponasty in four stands with mixtures of the two plant types and with different plant densities. (B) Simulated total accumulated biomass per individual for both plant types after 46 d of growth in stands with mixtures of the two plant types and with four different densities. Data represent the mean ± SD; n = 10. Statistically significant differences are indicated as *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001, paired Student’s t test.

Discussion

An early plant response to FR light reflected by neighbors is upward leaf movement, hyponasty, followed by petiole elongation (8). Because in dense stands the distribution of light quality is heterogeneous even at the level of individual plants, we studied how localized FR exposures can elicit pronounced different shade-avoidance responses. Here we show how the site of FR light detection influences the adaptive value of the elicited responses and provide evidence that auxin spatially translates the neighbor-detection cue to a growth response.

Functionality of Localized R/FR Detection for Different Responses.

We found that petiole elongation is induced only when the low R/FR exposure occurs on the target petiole itself, whereas hyponasty is induced only if the low R/FR is sensed at the lamina tip of the same leaf (Fig. 1). FSP modeling of Arabidopsis rosettes showed that sensing R/FR at the lamina tip indeed is the most effective way to induce hyponasty in response to neighbor proximity (Fig. 6). The lamina tip is the first tissue to approach a neighbor and thus is the first to be exposed to neighbor-induced reductions in R/FR in stands of rosette-forming plants such as Arabidopsis. This rather robust system is found in short day-grown, relatively mature Arabidopsis plants (this study), in much younger and long day-grown Arabidopsis (29), and in another species, B. nigra (this study). The R/FR at the level of the petiole will also be reduced by self-shading, and using this signal to induce hyponasty would be maladaptive. Because a low R/FR at the petiole level does induce petiole elongation, such elongation may be an intrinsic aspect of regular petiole length growth in Arabidopsis, irrespective of neighbor proximity. A previous study (30) showed that FR treatment of the lamina can also induce petiole elongation by giving supplemental FR at the end of the photoperiod to the full lamina rather than only to the very tip of the lamina. Indeed, when we moved the FR spotlight on the lamina closer to the petiole, we observed a modest stimulation of petiole elongation (Fig. 1D).

Auxin and PIFs Control the Hyponastic Response to Localized FR Detection.

Low R/FR light inactivates phyB, allowing PIFs to accumulate and become active to control transcription of target genes including YUCs (13, 15, 31). Indeed, phyBphyDphyE, pif4pif5, and pif7 mutants displayed a severe reduction of hyponasty in the W+FRtip condition (Fig. 1 E–G). Interestingly, the pif4pif5 double mutant was fully responsive to W+FRwhole, whereas the pif7 mutant remained unresponsive, indicating a particularly important function for PIF7. Because hyponasty in the pif4pif5 mutant could be rescued only by very high exogenous IAA concentrations relative to Col-0 WT and pif7 plants (Fig. 5C), we conclude that PIF4 and PIF5 control auxin responsiveness (32, 33). The observations that pif7 (i) lacks any hyponastic response to W+FRwhole and W+FRtip (Fig. 1G), (ii) lacks YUC8 and YUC9 expression in the lamina tip (Fig. 4 A and B), and (iii) responds like the WT to exogenous IAA (Fig. 5C) suggest that PIF7 controls auxin production in the lamina tip (18) to regulate hyponasty. Indeed, PIF7 is also expressed more in the lamina tip than in the petiole base (Fig. S5E). In the absence of PIF7 there is insufficient lamina-derived IAA to drive auxin-mediated differential growth. Because we observed pronounced auxin gene-expression signatures (Fig. 2 and Fig. S5) and luminescence of the auxin-responsive DR5:LUC reporter (Fig. 5 A and B) in the petiole upon FR enrichment of the lamina tip, IAA newly synthesized at the lamina tip is probably transported to the petiole base. Indeed, polar auxin transport mutants showed a disturbed response, and local application of the polar auxin transport inhibitor NPA to the lamina tip marginalized the W+FRtip response (Fig. 3 A and B). Following this route of auxin transport from the leaf tip ultimately into the roots (34) also explains why the response is restricted to the leaf exposed to supplemental FR and does not occur in systemic leaves.

The question then remains how newly synthesized auxin from the leaf tip remotely induces a differential growth response between the abaxial and adaxial sides of the petiole base (Fig. S3C). The DR5:LUC data indicate a differential auxin response between these two sides (Fig. 5 vs. Fig. S6C), perhaps indicating an auxin concentration gradient that could drive the differential elongation growth in the abaxial and adaxial sides of the petiole base. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that differences in auxin sensitivity underlie the differential DR5:LUC signal and growth response.

We conclude that auxin relays photoreceptor information to growth regulation over the distance of the two extreme ends of the leaf. This mechanism allows plants to sense neighbor plants as early as possible by using their most remote parts, which are the first to interact with neighbors, and to react with the adaptive response of upward leaf movement.

Materials and Methods

Plant Growth and Measurements.

Genotypes used in this study were pif4-101 and pif4-101pif5-1 (14), pif7-1 (35), pif4-101pif5-1pif7-1 (18), wei8 (36), pin3-3 (37), pin3-3pin4pin7 (38), yuc8, yuc9, and yuc8yuc9 (39), and DR5:LUC (40) (all on the Col-0 background) and phyBphyDphyE (14) (on the Ler background). Seeds were sown on soil, stratified (3 d in the dark, 4 °C), and then transferred to growth rooms (9 h light, 130–135 μmol⋅m−2⋅s−1 PAR, R/FR 2.3, 20 °C, 70% relative humidity). After 11 d, seedlings were transplanted to 70-mL pots. The fifth-youngest leaf of 28-d-old plants was used for petiole angle and length experiments. Pictures were taken before (t = 0 h) and after (t = 24 h) treatment; angles were measured using ImageJ software (NIH). Petiole lengths were recorded with a digital caliper. All experiments started at 10:00 AM (zeitgeber time = 2 h).

Light Treatments.

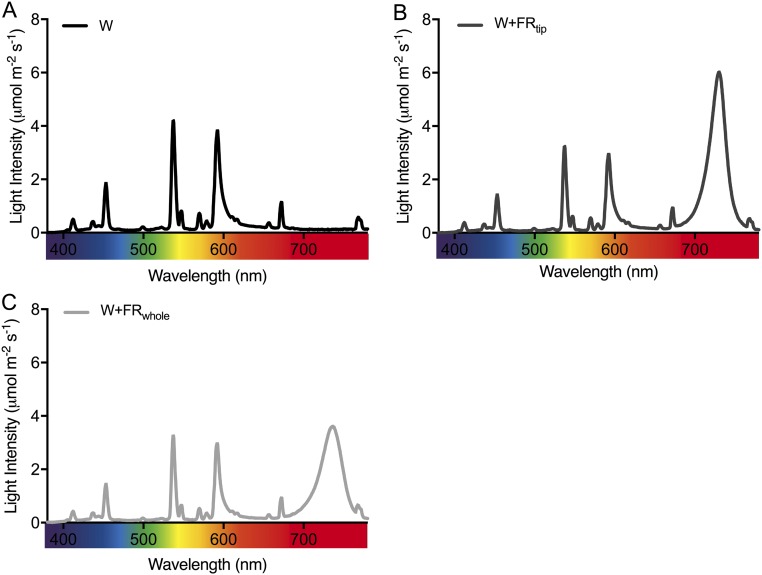

In addition to control W light from Philips HPI lamps (R/FR = 2.3), FR supplementation treatments were used: whole-plant FR enrichment (W+FRwhole) through FR LED (Philips Green-Power FR) supplementation of the W background (R/FR = 0.05) and localized FR enrichment by directing FR spotlights (Ø3.5 mm) to selective parts of the leaf using custom FR LEDs (724–732 nm; local R/FR = 0.05). PAR was constant at 125–135 μmol⋅m−2⋅s−1 for all treatments. Light spectra were recorded with Ocean Optics JAZ equipment (Fig. S8).

Fig. S8.

The spectral composition of light in the three major light conditions. (A) Control white light (W). (B) White light with a supplemental FR spotlight at the lamina tip (W+FRtip). (C) White light with supplemental FR at the whole-plant level (W+FRwhole).

Pharmacological Treatments.

Localized auxin was applied as 5-µL droplets of 30 μM IAA (Duchefa Biochemie), and polar auxin transport was inhibited with 4 or 5 µL of 50 μM NPA (Duchefa Biochemie). Solutions, including mock treatments, contained 0.1% Tween20 and 0.03% (for IAA) or 0.05% (for NPA) DMSO. When NPA was applied to the lamina–petiole junction, the solution was supplemented with 0.05% agar to stabilize the droplet. Solutions were applied right before commencing light treatments. IAA was applied to the abaxial side of the petiole via a small piece of filter paper containing auxin or mock solution stuck to the petiole base and rewetted frequently with the solutions.

RNA Isolation and Gene-Expression Quantification.

The lamina tip (top 2.5 mm) and petiole base (basal 1.5 mm) of the plant’s fifth-youngest leaf were harvested for RNA isolation after 5 h of light treatment (W, W+FRtip, or W+FRwhole). Lamina tips or petiole bases (10 for qRT-PCR or 15 for microarrays) were pooled as one biological replicate. RNA was isolated from three (transcriptomics) or four (qRT-PCR) independent biological replicates per treatment and tissue using the RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN). For qRT-PCR, cDNA was synthesized using random hexamer primers (Invitrogen). qRT-PCR was performed using Applied Biosystems ViiA 7 (Thermo Scientific) with SYBR Green Master Mix (Bio-Rad) with gene-specific primers. (Primers are listed in Table S1.) Relative transcript abundance was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method (41) normalized to PEX4 (AT5G25760) and RHIP1 (AT4G26410). For transcriptomics, samples were hybridized to Affymetrix 1.1 ST Arabidopsis arrays by AROS Applied Biotechnology; data have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession no. GSE98643). Data were processed in R software using Bioconductor packages “oligo” and “pd.aragene.1.1.st” for quality check and normalization, and “limma” for differential expression analysis. Genes with an adjusted P value ≤ 0.01 and log2FC > 1 or less than −1 were considered differentially expressed. GO analysis was done with AmiGO (amigo1.geneontology.org/cgi-bin/amigo/term_enrichment) (42). A hormonometer (hormonometer.weizmann.ac.il/) (27) was used to identify hormonal signatures in our transcriptomes.

Table S1.

Primer sequences (5′–3′) used for qRT-PCR

| Gene name | Primer | 5′–3′ sequence |

| AT1G04180 (YUC9) | Forward | AGTCCGGCGAGAAATTCAGA |

| AT1G04180 (YUC9) | Reverse | AACCGAGCTTCTAACGACCA |

| AT4G28720 (YUC8) | Forward | TGCGGTTGGGTTTACGAGGAAAG |

| AT4G28720 (YUC8) | Reverse | GCGTTTCGTGGGTTGTTTTG |

| AT1G70940 (PIN3) | Forward | CTTATTTGGGCTCTCGTCGC |

| AT1G70940 (PIN3) | Reverse | AACGTTGCCACTGAATTCCC |

| AT2G46970 (PIL1) | Forward | AGACCACCTACGATGTTGCC |

| AT2G46970 (PIL1) | Reverse | TAGCATTTGTGGTGGTGCAT |

| AT5G25760 (housekeeping gene PEX4) | Forward | TGCAACCTCCTCAAGTTCGA |

| AT5G25760 (housekeeping gene PEX4) | Reverse | TGAGTCGCAGTTAAGAGGACT |

| AT4G26410 (housekeeping gene RHIP1) | Forward | ATTGGTGTCGCTGCTAGTCT |

| AT4G26410 (housekeeping gene RHIP1) | Reverse | TAAAGCCGTCCTCTCAAGCA |

Luciferase Assay.

DR5:LUC plants were exposed to the light or hormone treatments for 7 h. Whole shoots or single leaves then were cut and evenly sprayed with 2 mM d-luciferin potassium salt (BioVision, Inc.) in 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100. Luciferase luminescence was imaged in a ChemiDoc imager (Bio-Rad) with a 40-min exposure time. The Fiji lookup table “Fire” was used to convert black and white images into color scales based on pixel intensity. Relative luciferase intensity in the petiole was analyzed by measuring the mean pixel intensity of the petiole in Icy software (v1.8.6.0; icy.bioimageanalysis.org) (43).

FSP Model.

A recently developed functional-structural plant model of Arabidopsis rosettes was used to study the relative functional impact on hyponasty induction of R/FR detection occurring at the lamina tip or petiole. Details of this model are described in SI Materials and Methods. Principles for plant structure, growth, and light interactions are based largely on models used in previous work (25, 26).

SI Materials and Methods

FSP Model.

A recently developed FSP model of Arabidopsis rosettes was used to simulate artificial Arabidopsis plant types, using the simulation platform GroIMP and its radiation model (https://sourceforge.net/projects/groimp/). The model is available upon request. Arabidopsis rosettes are represented by a collection of leaves (represented by a petiole and a lamina). Their appearance rate and shape were based on empirical data. We defined the lamina tip as representing 7% of total lamina area at the most distal part of the lamina (Fig. S7A). In our simulations, the light source PAR was 400–700 nm at an intensity of 220 μmol⋅m−2⋅s−1, with a R/FR ratio of 2.3. In each model time step, these light rays were reflected, transmitted, and absorbed by the petioles and laminas according to their wavelength-specific spectral properties. The PAR absorbed at each time step determined the amount of carbon fixation for growth, which consequently determined biomass accumulation (in milligrams) for each organ. The amount of biomass determined organ size, which in turn determined the reflection, transmission, and absorption of light by the simulated plants. Thus, the leaves grew individually in time in three dimensions based on leaf-level PAR absorption, photosynthesis, and between-organ carbon allocation principles [explained in more detail in ref. (25)]. Simulated plant growth depended on the level of competition for light that individual plants experienced from neighboring plants. Plant size and biomass therefore were an emergent property of the model. Hyponasty was calculated each time step by a unit–step response curve: When R/FR perception at the specific petiole or lamina tip was below a threshold of 0.5, the leaf angle increased with a fixed amount of 20°; otherwise the leaf angle was maintained. The angle of the leaf over time therefore was a function of the number of time steps in which this low R/FR perception occurred, with a maximum leaf angle of 80°. In our model hyponastic responses influenced light competition between individual plants based on two principles. First, elevated leaves (i.e., leaves that are not horizontal) intercept less light than horizontally positioned leaves when plants grow solitarily. Second, in the presence of neighboring plants horizontal leaves will intercept less light because of overlap with neighbor leaves. Thus the positioning of leaves in a horizontal or more vertical position determined the total light interception that drives biomass accumulation, and this positioning depended on the presence of neighbor plants.

Model Scenarios.

All Arabidopsis stands were constructed by placing plants in 4 × 4 grids at different interplant distances (1, 2, 5, and 10 cm), resulting in four canopy densities: 10,000, 2,500, 400, and 100 plants/m2. In stands with a low density (100 plants/m2), neighboring plants did not interact with each other, and no additional rows were simulated. Stands with a density of 400 or 2,500 plants/m2 were simulated with two extra plant rows, and stands with an extremely high density of 10,000 plants/m2 with were simulated with four extra plant rows to correct for possible border effects. Plant orientations (determined by the direction of the leaves) at their positions in the field were random, just as would be the case in experimental plots. In the first simulation scenario, two stands were simulated with a density of 100 and 2,500 plants/m2, respectively, representing low and high canopy density, with plants that did not use the incident R/FR for signaling and therefore did not become hyponastic. In the second simulation scenario, four competition stands with a mixture of Petiole and Tip plant types, which used the R/FR signal at the petiole and the R/FR signal at the lamina tip, respectively, to induce hyponasty, were simulated at the four densities. In these mixed stands, the two different plant types were placed in a 50–50% checkerboard design. Each replicate stand consisted of eight plants of each plant type (Petiole and Tip) that were averaged per plant type per stand. Model output was subsequently calculated as the mean of 10 replicated stands. Because PAR absorption and R/FR perception were the driving factors of plant growth and development, the plant leaf angle and biomass accumulation in different canopy densities were the emergent properties of the model.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jojanneke Voorhoeve for help with the B. nigra experiments; members of the Plant Ecophysiology group (Utrecht University) for help with tissue harvests for the gene-expression experiments; Christian Fankhauser, Ikram Blilou, and Stephan Pollmann for distributing seeds; and Scott Hayes for excellent feedback on a draft of this manuscript. This work was funded by Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research Vidi Grant 86512.003 (to R.P.) and Earth and Life Sciences Grant 821.01.014 (to N.P.R.A.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The microarray data reported in this paper have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GSE98643).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1702275114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Monsi M, Saeki T. On the factor light in plant communities and its importance for matter production. 1953. Ann Bot (Lond) 2005;95:549–567. doi: 10.1093/aob/mci052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boonman A, Prinsen E, Voesenek LACJ, Pons TL. Redundant roles of photoreceptors and cytokinins in regulating photosynthetic acclimation to canopy density. J Exp Bot. 2009;60:1179–1190. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crepy MA, Casal JJ. Photoreceptor-mediated kin recognition in plants. New Phytol. 2015;205:329–338. doi: 10.1111/nph.13040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chelle M, et al. Simulation of the three-dimensional distribution of the red:far-red ratio within crop canopies. New Phytol. 2007;176:223–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ballaré CL, Sanchez RA, Scopel AL, Casal JJ, Ghersa CM. Early detection of neighbour plants by phytochrome perception of spectral changes in reflected sunlight. Plant Cell Environ. 1987;10:551–557. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casal JJ. Photoreceptor signaling networks in plant responses to shade. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2013;64:403–427. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fraser DP, Hayes S, Franklin KA. Photoreceptor crosstalk in shade avoidance. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2016;33:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pierik R, de Wit M. Shade avoidance: Phytochrome signalling and other aboveground neighbour detection cues. J Exp Bot. 2014;65:2815–2824. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Kroon H, Huber H, Stuefer JF, van Groenendael JM. A modular concept of phenotypic plasticity in plants. New Phytol. 2005;166:73–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ballaré CL, Pierik R. The shade avoidance syndrome: Multiple signals and ecological outputs. Plant Cell Environ. 2017 doi: 10.1111/pce.12914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Izaguirre MM, Mazza CA, Astigueta MS, Ciarla AM, Ballaré CL. No time for candy: Passionfruit (Passiflora edulis) plants down-regulate damage-induced extra floral nectar production in response to light signals of competition. Oecologia. 2013;173:213–221. doi: 10.1007/s00442-013-2721-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Procko C, Crenshaw CM, Ljung K, Noel JP, Chory J. Cotyledon-generated auxin is required for shade-induced hypocotyl growth in Brassica rapa. Plant Physiol. 2014;165:1285–1301. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.241844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leivar P, Monte E. PIFs: Systems integrators in plant development. Plant Cell. 2014;26:56–78. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.120857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorrain S, Allen T, Duek PD, Whitelam GC, Fankhauser C. Phytochrome-mediated inhibition of shade avoidance involves degradation of growth-promoting bHLH transcription factors. Plant J. 2008;53:312–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li L, et al. Linking photoreceptor excitation to changes in plant architecture. Genes Dev. 2012;26:785–790. doi: 10.1101/gad.187849.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bou-Torrent J, et al. Plant proximity perception dynamically modulates hormone levels and sensitivity in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2014;65:2937–2947. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Wit M, et al. Integration of phytochrome and cryptochrome signals determines plant growth during competition for light. Curr Biol. 2016;26:3320–3326. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Wit M, Ljung K, Fankhauser C. Contrasting growth responses in lamina and petiole during neighbor detection depend on differential auxin responsiveness rather than different auxin levels. New Phytol. 2015;208:198–209. doi: 10.1111/nph.13449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nozue K, et al. Shade avoidance components and pathways in adult plants revealed by phenotypic profiling. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1004953. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Won C, et al. Conversion of tryptophan to indole-3-acetic acid by TRYPTOPHAN AMINOTRANSFERASES OF ARABIDOPSIS and YUCCAs in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:18518–18523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108436108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sequeira L, Steeves TA. Auxin inactivation and its relation to leaf drop caused by the fungus Omphalia flavida. Plant Phys. 1953;29:11–16. doi: 10.1104/pp.29.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pierik R, Djakovic-Petrovic T, Keuskamp DH, de Wit M, Voesenek LACJ. Auxin and ethylene regulate elongation responses to neighbor proximity signals independent of gibberellin and DELLA proteins in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2009;149:1701–1712. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.133496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keuskamp DH, Pollmann S, Voesenek LACJ, Peeters AJM, Pierik R. Auxin transport through PIN-FORMED 3 (PIN3) controls shade avoidance and fitness during competition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:22740–22744. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013457108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vos J, et al. Functional-structural plant modelling: A new versatile tool in crop science. J Exp Bot. 2010;61:2101–2115. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Evers JB, Bastiaans L. Quantifying the effect of crop spatial arrangement on weed suppression using functional-structural plant modelling. J Plant Res. 2016;129:339–351. doi: 10.1007/s10265-016-0807-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bongers FJ, Evers JB, Anten NPR, Pierik R. From shade avoidance responses to plant performance at vegetation level: Using virtual plant modelling as a tool. New Phytol. 2014;204:268–272. doi: 10.1111/nph.13041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Volodarsky D, Leviatan N, Otcheretianski A, Fluhr R. HORMONOMETER: A tool for discerning transcript signatures of hormone action in the Arabidopsis transcriptome. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:1796–1805. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.138289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nemhauser JL, Hong F, Chory J. Different plant hormones regulate similar processes through largely nonoverlapping transcriptional responses. Cell. 2006;126:467–475. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michaud O, Fiorucci AS, Xenarios I, Fankhauser C. Local auxin production underlies a spatially restricted neighbor-detection response in Arabidopsis. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:7444–7449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1702276114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kozuka T, et al. Involvement of auxin and brassinosteroid in the regulation of petiole elongation under the shade. Plant Physiol. 2010;153:1608–1618. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.156802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leivar P, Quail PH. PIFs: Pivotal components in a cellular signaling hub. Trends Plant Sci. 2011;16:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hersch M, et al. Light intensity modulates the regulatory network of the shade avoidance response in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:6515–6520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320355111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hornitschek P, et al. Phytochrome interacting factors 4 and 5 control seedling growth in changing light conditions by directly controlling auxin signaling. Plant J. 2012;71:699–711. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhalerao RP, et al. Shoot-derived auxin is essential for early lateral root emergence in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant J. 2002;29:325–332. doi: 10.1046/j.0960-7412.2001.01217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leivar P, et al. The Arabidopsis phytochrome-interacting factor PIF7, together with PIF3 and PIF4, regulates responses to prolonged red light by modulating phyB levels. Plant Cell. 2008;20:337–352. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.052142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stepanova AN, et al. TAA1-mediated auxin biosynthesis is essential for hormone crosstalk and plant development. Cell. 2008;133:177–191. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Friml J, et al. AtPIN4 mediates sink-driven auxin gradients and root patterning in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2002;108:661–673. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00656-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Willige BC, et al. D6PK AGCVIII kinases are required for auxin transport and phototropic hypocotyl bending in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2013;25:1674–1688. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.111484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen Q, et al. Auxin overproduction in shoots cannot rescue auxin deficiencies in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014;55:1072–1079. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moreno-Risueno MA, et al. Oscillating gene expression determines competence for periodic Arabidopsis root branching. Science. 2010;329:1306–1311. doi: 10.1126/science.1191937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boyle EI, et al. GO:TermFinder–open source software for accessing Gene Ontology information and finding significantly enriched Gene Ontology terms associated with a list of genes. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3710–3715. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Chaumont F, et al. Icy: An open bioimage informatics platform for extended reproducible research. Nat Methods. 2012;9:690–696. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.