Significance

Ribonucleases are molecular scissors that catalyze the cleavage of RNA phosphodiester bonds and play essential roles in RNA processing and maturation. Precursor ribosomal RNA (rRNA) must be processed by several ribonucleases, including the endonuclease Las1, in a carefully orchestrated manner to generate the mature ribosomal subunits. Las1 is essential for cell viability, and mutations in the mammalian gene have been linked with human disease, underscoring the importance of this enzyme. Here, we show that, on its own, Las1 has weak activity; however, when associated with its binding partner, the polynucleotide kinase Grc3, Las1 is programmed to efficiently cleave pre-rRNA at the C2 site. Together, Grc3 and Las1 assemble into a higher-order complex exquisitely primed for cleavage and phosphorylation of RNA.

Keywords: pre-rRNA processing, endoribonuclease, polynucleotide kinase, HEPN domain, Las1

Abstract

Las1 is a recently discovered endoribonuclease that collaborates with Grc3–Rat1–Rai1 to process precursor ribosomal RNA (rRNA), yet its mechanism of action remains unknown. Disruption of the mammalian Las1 gene has been linked to congenital lethal motor neuron disease and X-linked intellectual disability disorders, thus highlighting the necessity to understand Las1 regulation and function. Here, we report that the essential Las1 endoribonuclease requires its binding partner, the polynucleotide kinase Grc3, for specific C2 cleavage. Our results establish that Grc3 drives Las1 endoribonuclease cleavage to its targeted C2 site both in vitro and in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Moreover, we observed Las1-dependent activation of the Grc3 kinase activity exclusively toward single-stranded RNA. Together, Las1 and Grc3 assemble into a tetrameric complex that is required for competent rRNA processing. The tetrameric Grc3/Las1 cross talk draws unexpected parallels to endoribonucleases RNaseL and Ire1, and establishes Grc3/Las1 as a unique member of the RNaseL/Ire1 RNA splicing family. Together, our work provides mechanistic insight for the regulation of the Las1 endoribonuclease and identifies the tetrameric Grc3/Las1 complex as a unique example of a protein-guided programmable endoribonuclease.

Nucleases are found throughout all walks of life and are involved in numerous biological processes, including DNA replication and repair, RNA processing and maturation, and cell defense and death (1). Despite their long history, new nucleases continue to be discovered. For example, the discovery of the ability to program CRISPR-associated nucleases at specific sites by guide RNAs has led to an explosion in gene editing (2, 3). Another recently identified nuclease is the endoribonuclease Las1 (Las1L in mammals), which plays a vital role in eukaryotic ribosome assembly (4). Mutations in the LAS1L gene have been linked to a congenital motor neuron disease (5) and X-linked intellectual disability disorders (6), highlighting the need to further understand the activity of this essential enzyme.

Ribosome assembly begins within the nucleolus of the cell with the transcription of the pre-ribosomal RNA (rRNA) by RNA Pol I, which is transcribed as a long polycistronic precursor, known as the 35S pre-rRNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Sc) (7, 8). The 35S pre-rRNA includes the 18S, 5.8S, and 25S rRNA as well as two external sequences [5′- and 3′-external transcribed spacers (ETSs)] and two internal sequences [internal transcribed spacers (ITS1 and ITS2)]. Removal of these four spacer sequences is a complex process requiring numerous exonucleases and endonucleases (9). Cleavage within ITS1 separates the 40S and 60S maturation pathways, whereas the subsequent removal of the ITS2 is an important step in the 60S maturation pathway. The first step in the removal of ITS2 is the separation of the precursors of the 5.8S and 25S rRNA by cleavage at the C2 site, which lies along the tip of domain V of the ITS2 (9).

Las1 was recently identified as the long-sought-after endonuclease, which specifically cleaves at the C2 site and generates the 7S pre-rRNA with a terminating 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate and the 26S pre-rRNA with a hydroxyl group at the 5′-end (Fig. 1A) (4). Las1 contains an N-terminal α-helical higher eukaryotes and prokaryotes nucleotide-binding (HEPN) domain, found in various RNases, such as the CRISPR effector C2c2, and the IFN-induced RNaseL (10, 11). HEPN endonucleases contain a conserved RΦxxxH catalytic motif (where Φ is commonly N, D, or H, and x is any residue) that generates products with a terminal 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate (10). Although it is now established that Las1 is the C2 endoribonuclease, there are numerous outstanding questions about the role of this enzyme in ribosome assembly. Specifically, it remains unknown how this enzyme targets the C2 site, what regions of Las1 and the ITS2 are required for recognition of the C2 site, and how the activity of this enzyme is regulated.

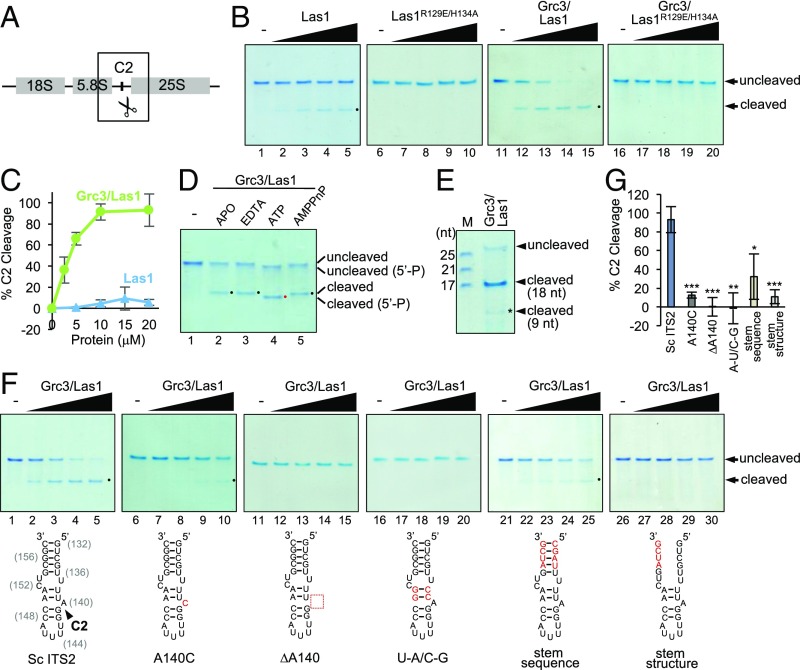

Fig. 1.

Grc3 drives Las1-mediated RNA cleavage. (A) Cartoon of the 35S pre-rRNA illustrating the location of the C2 cleavage site. (B) In vitro cleavage assays of Las1 variants (5–20 μM) and Grc3/Las1 variants (2.5–20 μM) incubated with ITS2 model RNA (10 μM) in storage buffer. The black dot marks the C2 cleavage product. (C) Quantification of RNA cleavage product generated from a concentration series of Las1 alone (blue) and Las1 bound by Grc3 (green). (D) Grc3/Las1 (10 μM) was mixed with 10 μM model ITS2 RNA in the absence and presence of excess nucleotides (1 mM) and EDTA (5 mM) where indicated. The black and red dots highlight the unphosphorylated and 5′-phosphorylated RNA cleavage product, respectively. (E) Grc3/Las1 (40 μM) was incubated with 10 μM ITS2 model RNA. An RNA ladder is shown to assess size of RNA cleavage products. The asterisk marks the 9-nt RNA product characterized by mass spectrometry analysis. (F) Grc3/Las1 (2.5–20 μM) was incubated with 10 μM modified ITS2 model RNAs illustrated below. A black arrowhead marks the C2 cleave site mapped by mass spectrometry analysis (Fig. S1). Modified nucleotides are colored in red. Numbers in brackets are the nucleotide residues from the Sc ITS2. (G) Quantification of RNA cleavage product generated from Grc3/Las1 (20 μM) incubated with modified RNA substrates. The mean and SD were calculated from three replicates. *P < 0.04, **P < 0.002, and ***P < 0.001 were calculated by two-tailed Student’s t tests.

Following cleavage at the C2 site by Las1, the 5′-OH of the 26S pre-rRNA is phosphorylated by the polynucleotide kinase Grc3 (Nol9 in mammals), which provides the signal for the exonuclease Rat1 and its cofactor Rai1 to remove the 5′-end of the 26S pre-rRNA and generate the 25S rRNA (4). Grc3 is closely related to Clp1, another eukaryotic 5′-polynucleotide kinase, which plays an important role in mRNA processing and tRNA splicing (12–14). Grc3 and Clp1 share a conserved polynucleotide kinase (PNK) domain, and although both have been shown to phosphorylate DNA and RNA in vitro, their in vivo substrates appear to be RNA (12, 15, 16). The conserved PNK domains of Grc3 and Clp1 are flanked by distinct N- and C-terminal domains (12); however, the function of these additional domains in Grc3 is unclear. Clp1 interacts with Pcf11, another protein involved in mRNA processing, through a well-conserved patch within its PNK domain (17). It has been proposed that Grc3 interacts with its binding partner Las1 through an analogous fashion to Clp1 and Pcf11; however, the molecular details of the Grc3/Las1 interaction are unknown (4).

Las1 and Grc3 have been shown to form a stable complex both on and off preribosome particles, and the complex is stable even under high-salt conditions (4, 18, 19). The Grc3/Las1 interaction is well conserved across eukaryotes, and the two proteins are dependent on one another for their stabilization (18, 20). Aside from stability, it is unknown why Grc3 and Las1 are so tightly associated, thus raising the question as to whether complex assembly is a requirement for enzymatic activity. To gain mechanistic insight into the endoribonuclease activity of Las1 and the polynucleotide kinase activity of Grc3, we reconstituted C2 cleavage in vitro and characterized the assembly of the Grc3/Las1 complex. These studies reveal functional cross talk between Las1 and Grc3; both enzymes are dependent on one another for higher-order assembly, nuclease and kinase enzymatic activities, recognition and cleavage of the C2 site, and efficient ribosome production.

Results

Grc3 Drives Las1 Cleavage to the C2 Site.

To investigate the role of Las1 in cleavage of the C2 site, we purified recombinant Sc Las1 (Fig. S1) and performed in vitro Las1 cleavage assays using a model RNA substrate of Sc ITS2 harboring the C2 site (9, 21). Las1 exhibited very weak cleavage activity that was not detectable under the experimental conditions examined with the endonuclease-deficient Las1R129E/H134A variant (Fig. 1B, lanes 1–5 versus 6–10; Fig. 1C). Interestingly, in the presence of Grc3, Las1 was programed to efficiently cleave RNA at a specific position (Fig. 1B, lanes 11–15; Fig. 1C). We observed a single prominent cleavage product, indicating that Grc3-directed Las1 cleavage occurs near the base of our ITS2 model substrate. This specific nuclease activity was attributed to Las1 because the observed cleavage product was absent with the endonuclease-deficient Grc3/Las1R129E/H134A variant (Fig. 1B, lanes 11–15 versus 16–20). Therefore, one role of Grc3 is to specifically direct Las1 to the C2 site for cleavage.

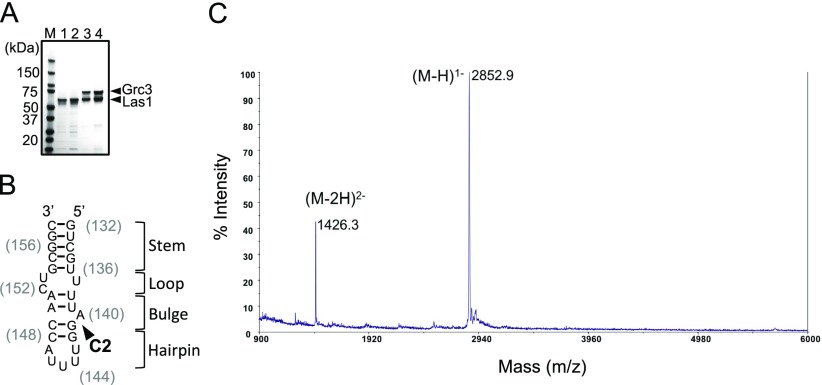

Fig. S1.

Identification of RNA product using mass spectrometry. (A) SDS/PAGE analysis of recombinant Sc Las1 (lane 1), Las1R129E/H134A (lane 2), Grc3/Las1 (lane 3), and Grc3/Las1R129E/H134A (lane 4). (B) Cartoon schematic of the Sc ITS2 RNA mimic used for C2-cleavage assays. (C) The smaller RNA fragment generated following Grc3/Las1 cleavage of our ITS2 RNA mimic was analyzed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. We identified ions of m/z 2852.9 and 1426.3, indicative of singly and doubly charged 5′-GUCGUUUUA-3′ of our ITS2 RNA substrate harboring a 5′-OH and 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate.

Specificity of the C2 Site.

After identifying the requirement for both Las1 and Grc3, we sought to probe other requirements for specificity of the C2 site. HEPN-containing endoribonucleases are metal-independent enzymes (10) and the efficiency of Grc3/Las1 cleavage of our ITS2 model RNA was unaltered in the presence of excess EDTA (Fig. 1D, lane 3). Following C2 cleavage, Las1 generates a 5′-OH terminus that is targeted by Grc3 polynucleotide kinase activity (4). When we repeat our nuclease assay in the presence of ATP, we observe a shift in the cleaved RNA product indicative of 5′-phosphorylation (Fig. 1D, lane 4). Correspondingly, this shift was absent in the presence of the nonhydrolyzable analog AMPPnP (Fig. 1D, lane 5). Interestingly, Grc3 also phosphorylates the 5′-OH of our intact C2 RNA mimic (Fig. 1D, upper band in lane 4) suggesting that, although there is specificity for nuclease activity, Grc3 nonspecifically phosphorylates the 5′-OH of RNA under the experimental conditions examined.

To unambiguously identify the C2 cleavage site within our model RNA substrate, we mapped the Grc3/Las1-mediated cleavage product. In the presence of Grc3, Las1 cleaved following residue 9 of our C2 mimic, as we observed a band of 18 nt in length and a corresponding smaller faint band (Fig. 1E). MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry of the cleavage reaction gave rise to ions at m/z 2853 and m/z 1426 that correspond in mass to the singly and doubly charged forms of the first 9 nt of our ITS2 substrate (5′-GUCGUUUUA-3′) with a terminal 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate (Fig. S1). This cleavage position corresponds to the bulge arising from a single unpaired adenine residue (Sc ITS2 A140) within the tip of domain V of the ITS2 (Fig. 1F) (22). These results are in agreement with previous studies on the 5′- to 3′-exonuclease Rat1, which suggested that the C2 cleavage event occurs between Sc ITS2 A140 and G141 (23, 24).

To probe the importance of the ITS2 sequence and RNA secondary structure for Grc3/Las1 substrate recognition, we compared cleavage efficiency against modified substrates. The two tandem G–C base pairs adjacent to the cleavage site were previously shown to be essential for ITS2 processing in vivo (21, 22); therefore, we focused on modifying other residues surrounding the cleavage site. Replacing the bulged adenine residue (A140) with a cytosine residue led to a significant reduction in cleavage (Fig. 1F, lanes 6–10; Fig. 1G), whereas removal of the bulged adenine residue completely abrogated C2 cleavage (Fig. 1F, lanes 11–15; Fig. 1G). Replacement of the tandem A–U base pairs with G–C base pairs also abrograted C2 cleavage (Fig. 1F, lanes 16–20; Fig. 1G). Moreover scrambling the RNA sequence of the ITS2 stem led to a reduction in Grc3/Las1 endoribonuclease activity, whereas disruption of the base pairs within the stem completely abrogated C2 cleavage (Fig. 1F, lanes 21–25 and 26–30; Fig. 1G), indicating that the stem secondary structure, and to a lesser extent the stem sequence, is required for Grc3/Las1-directed cleavage. This marks the strict necessity of the ITS2 RNA stem structure, sequence, and bulge for C2 recognition by the Grc3/Las1 complex.

Grc3/Las1 Form a Superdimer.

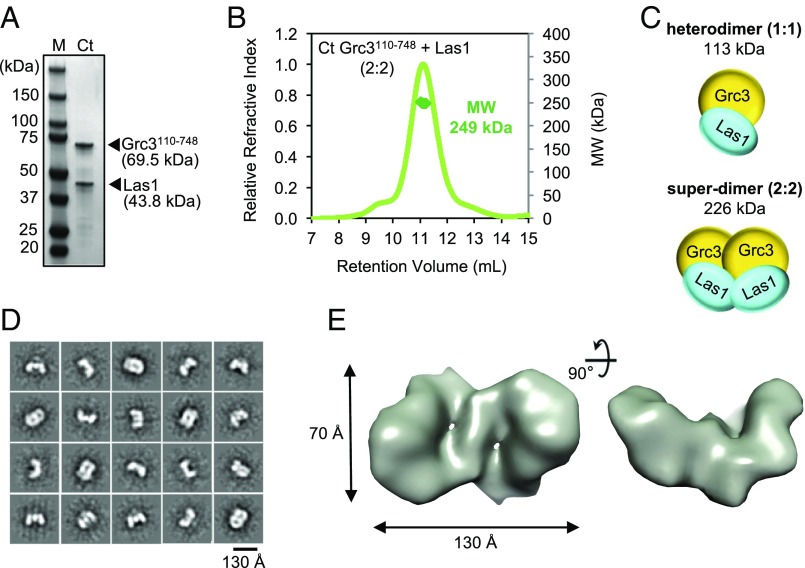

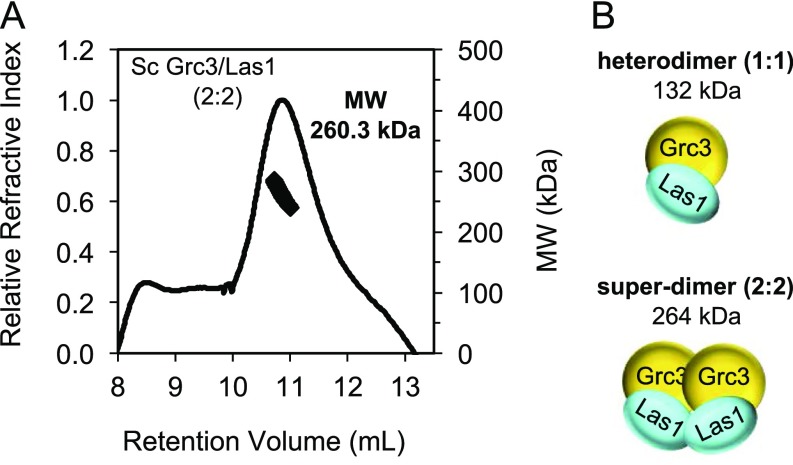

Despite the prominent role for Grc3 in regulating Las1 endoribonuclease function, little is known about the molecular organization of the Grc3/Las1 complex. For structural analyses, we purified recombinant Chaetomium thermophilum (Ct) Grc3110-748/Las1 lacking the Grc3 protease-labile N terminus, which we found is dispensable in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 2A and Fig. S2). To determine the molecular mass and stoichiometry of the Ct Grc3110-748/Las1 complex, we performed size exclusion chromatography coupled to multiangle light scattering (SEC-MALS) to reveal a molecular weight of 249 kDa (Fig. 2B), corresponding well with an arrangement of two Grc3/Las1 dimers (226 kDa) and excluding the possibility of another type of stoichiometry. We refer to this higher-order assembly as the Grc3/Las1 superdimer (Fig. 2C). We also determined that Sc Grc3/Las1 assembles into a tetramer, suggesting that this higher-order assembly is conserved across species (Fig. S3).

Fig. 2.

Grc3/Las1 form a superdimer. (A) SDS/PAGE analysis of the recombinant Chaetomium thermophilum (Ct) Grc3110-748/Las1 complex. (B) SEC-MALS of the Ct Grc3110-748/Las1 complex. (C) Cartoon schematic illustrating the molecular weight of the Ct Grc3110-748/Las1 complex with 1:1 versus 2:2 stoichiometry. The superdimer refers to the association of two heterodimers. (D) Single-particle analysis of negatively stained Ct Grc3110-748/Las1 complex. Selected reference-free class averages. (E) Orthogonal views of the 3D projection map of Ct Grc3110-748/Las1 generated by imposing C2 symmetry.

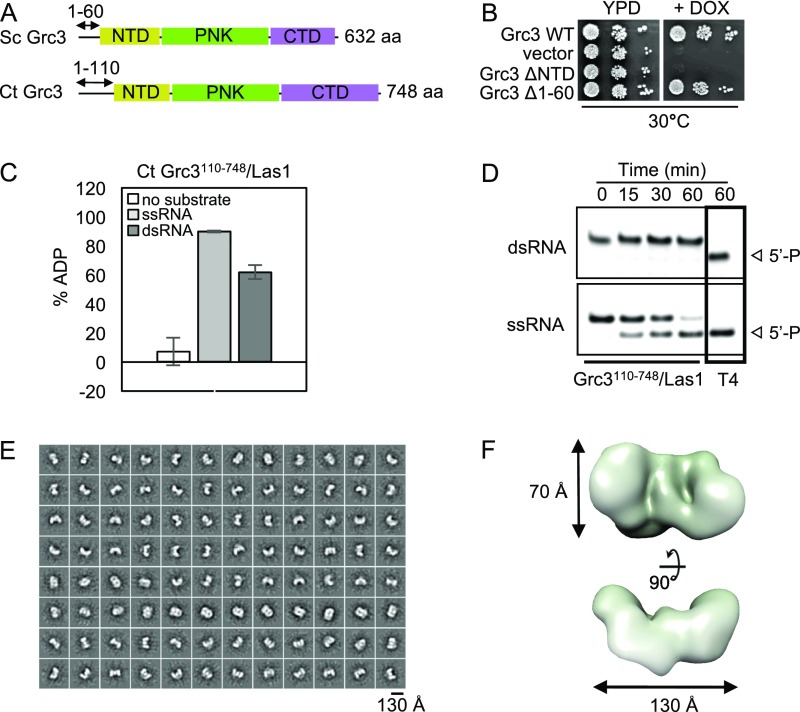

Fig. S2.

The N terminus of Grc3 is dispensable for function and higher-order assembly. (A) Cartoon diagram of the domain organization of S. cerevisiae (Sc) and Chaetomium thermophilum (Ct) Grc3 where the N-terminal domain (NTD), polynucleotide kinase domain (PNK), and C-terminal domain (CTD) are shown in yellow, green, and purple, respectively. Numbers above the diagram are the residues encompassing the labile N terminus. (B) Yeast growth assay of Sc Grc3 N-terminal mutants. TetO7-Grc3 transformants were plated on YPD plates in the absence and presence of 20 μg/mL doxycycline (DOX) and incubated at 30 °C for 3 d. Removal of the N-terminal domain (ΔNTD) caused a growth defect, whereas removing the first 60 residues (Δ1–60) had no effect on growth. (C) ATPase activity of C. thermophilum (Ct) Grc3110-748/Las1 (0.5 μM) in the absence and presence of either a 21-nt single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) or double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) (4 μM). Error bars represent the SD of three replicates. (D) Phosphorylation assay of Ct Grc3110-748/Las1 (2 μM) with a 21-nt ssRNA or dsRNA substrate (15 μM) over a time course at 37 °C. Positive control reactions included 10 units of T4 polynucleotide kinase (T4). (E) Negative-stain electron microscopy of Ct Grc3110-748/Las1 complex. Reference-free 2D class averages. (F) A low-resolution (∼20-Å) map reconstructed without imposing symmetry revealed a curved pretzel-like particle with approximate dimensions of 130 × 70 × 22 Å.

Fig. S3.

S. cerevisiae (Sc) Grc3/Las1 forms a superdimer. (A) SEC-MALS of full-length Sc Grc3/Las1 at 20 μM in storage buffer. Measured molecular weight was 260.3 kDa. (B) Cartoon schematic illustrating the full-length Sc Grc3/Las1 complex at 1:1 and 2:2 stoichiometry. Expected molecular weights are indicated below each schematic. The observed molecular weight corresponds to a Grc3/Las1 stoichiometry of 2:2.

To further test the superdimer hypothesis, we performed single-particle analysis on negative-stain electron microscope images of the Ct Grc3110-748/Las1 complex. Reference-free classification confirmed the presence of distinct twofold symmetric views of the complex (Fig. 2D). A low-resolution (∼20-Å) map reconstructed without imposing symmetry (Fig. S2) and with C2 symmetry revealed a curved pretzel-like particle with approximate dimensions of 130 × 70 × 22 Å (Fig. 2E). Overall, the structure includes sufficient density to accommodate two copies of Grc3 and Las1. Grc3 is ∼200 residues larger than the related polynucleotide kinase Clp1, and there is no structure with significant homology to the coiled-coil region of Las1, making it impossible to unambiguously position Grc3 and Las1 within the map at this resolution; however, these data provide structural insight into the organization of the Grc3/Las1 superdimer.

Las1 Endoribonuclease Domain Drives Higher-Order Assembly.

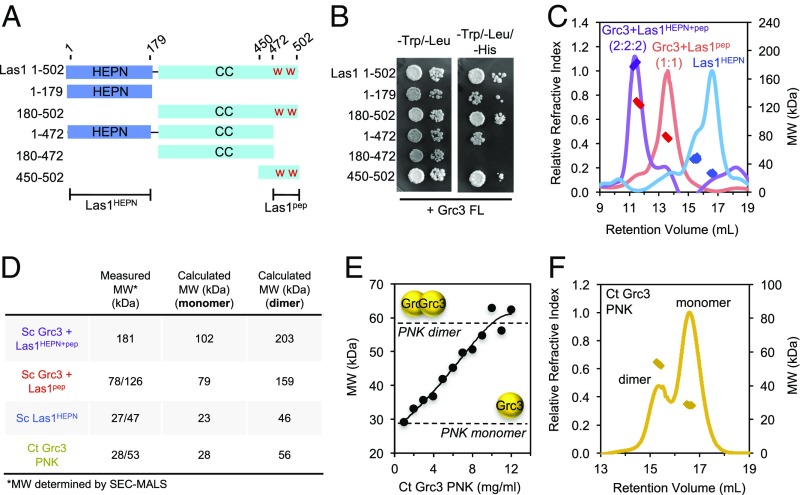

To probe the structural organization of the Grc3/Las1 superdimer, we performed yeast two-hybrid experiments. Las1 is a multidomain enzyme with an N-terminal HEPN domain (residues 1–179; Las1HEPN) and a C-terminal coiled-coil domain (residues 180–502; Las1CC) with unknown function (Fig. 3A). As shown previously, the Las1 C terminus (residues 450–502) encoding two conserved tryptophan residues (W488 and W494) retained the ability to bind Grc3 (Fig. 3B) (4). Unexpectedly, truncation of the Las1 C terminus (residues 1–472) did not abrogate Grc3 binding, suggesting a second Grc3-binding site within Las1. We determined that the Las1 HEPN domain also maintained Grc3 binding (Fig. 3B). Taken together, Las1 forms a stable complex with Grc3 through two discontinuous sites comprising Las1HEPN and the Las1 C terminus.

Fig. 3.

Las1 HEPN domain drives higher-order assembly. (A) Cartoon diagram of full-length and truncated Sc Las1 used for yeast two-hybrid. The Las1 HEPN and coiled-coil (CC) domains are shown in blue and cyan, respectively. The “W” (red) indicates the two tryptophan residues that have been proposed to be important for binding Grc3. (B) Yeast two-hybrid analysis using full-length Grc3 as bait and Las1 and assorted truncations as prey. Bait and prey transformants were mated and then plated on SD/−Trp/−Leu and SD/−Trp/−Leu/−His plates at 30 °C for 3 d. Growth on the SD/−Trp/−Leu/−His plates indicates an interaction. (C) SEC-MALS of Sc Grc3/Las1HEPN+pep (purple), Grc3/Las1pep (red), and Las1HEPN (blue). (D) SEC-MALS–derived and calculated molecular weights for Sc Grc3/Las1HEPN+pep, Sc Grc3/Las1pep, Sc Las1HEPN, and Ct Grc3 PNK. (E) Molecular weight of Ct Grc3 PNK domain in solution determined by SAXS. The molecular weight of the PNK domain increases from a monomer to a dimer with increasing protein concentration. The dotted lines mark the theoretical mass of the PNK monomer and dimer. (F) SEC-MALS of Ct Grc3 PNK domain.

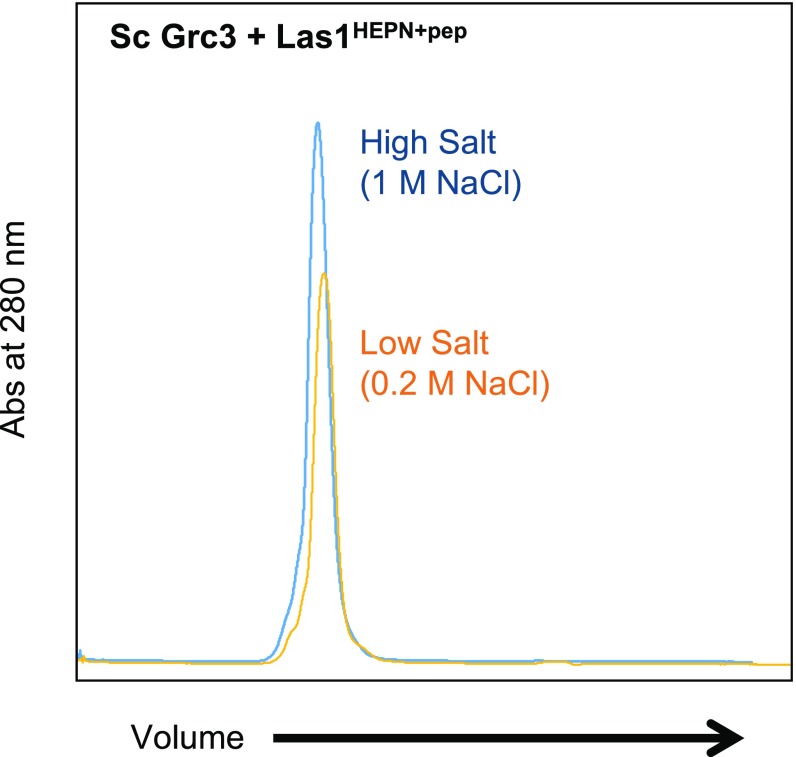

To shed light onto the driving force of Grc3/Las1 assembly, we coexpressed the minimal Las1 C-terminal sequence necessary for Grc3-binding and stability (Las1 residues 469–502; Las1pep) with full-length Sc Grc3 in the presence and absence of the Sc Las1HEPN domain. The Las1 HEPN domain stably associates with Sc Grc3/Las1pep even under high-salt conditions (Fig. S4). We purified both the Sc Grc3/Las1HEPN+pep and Grc3/Las1pep complexes by affinity chromatography followed by gel filtration and assessed their molecular mass by SEC-MALS (Fig. 3C). We found that the Las1 HEPN domain is required for higher-order assembly, whereas the C-terminal coiled-coil domain (residues 180–468) is dispensable. We also purified Las1HEPN in the absence of Grc3 and observed two distinct peaks by SEC-MALS corresponding to the Las1HEPN monomer–dimer equilibrium (Fig. 3 C and D). Collectively, these data suggest that the propensity for Las1 HEPN dimerization is one of the key factors favoring formation of the Grc3/Las1 superdimer.

Fig. S4.

The HEPN domain stably associates with Grc3/Las1pep. The S. cerevisiae (Sc) Las1 HEPN domain was coexpressed with Grc3/Las1pep and resolved over a Superdex-200 10/300 GL gel filtration column using storage buffer at low salt (0.2 M NaCl; orange) and high salt (1 M NaCl; blue). The Las1 HEPN domain remains bound to the Grc3/Las1pep complex in low- and high-salt conditions.

We also observed a reproducible shoulder for the Grc3/Las1pep complex (Fig. 3 C and D), suggesting that Grc3/Las1pep has a weak propensity to associate in the absence of the HEPN domain. To identify the Grc3 region(s) responsible for oligomerization, we expressed and purified the N-terminal domain, central PNK domain, and C-terminal domain from Sc and Ct Grc3; however, only Ct Grc3 PNK yielded stable protein. We measured the molecular weight of Grc3 PNK in solution over a concentration series (1–12 mg/mL) by small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS). From a low to high protein concentration, the measured molecular weight ranged from the size of a PNK monomer (28 kDa) to that of a dimer (56 kDa) (Fig. 3E). Consistent with this notion, we observed both monomeric and dimeric Ct Grc3 PNK in solution by SEC-MALS (Fig. 3 D and F). Therefore, the Las1 HEPN domain drives higher-order assembly through homodimerization, whereas the Grc3 PNK domain participates in further stabilizing the superdimer interface.

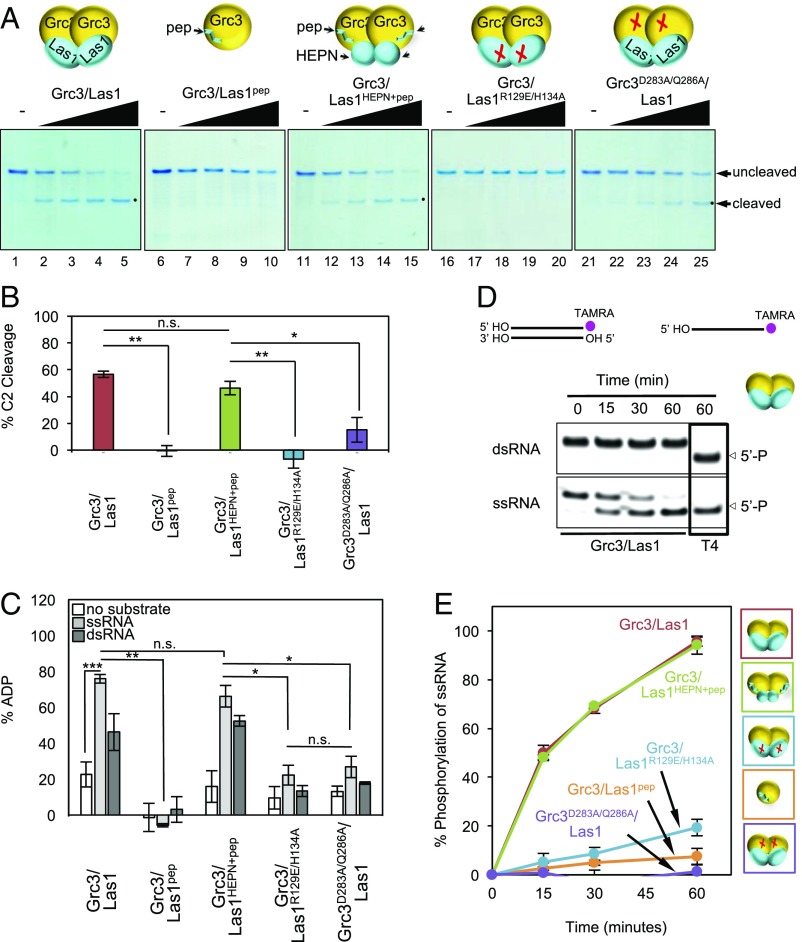

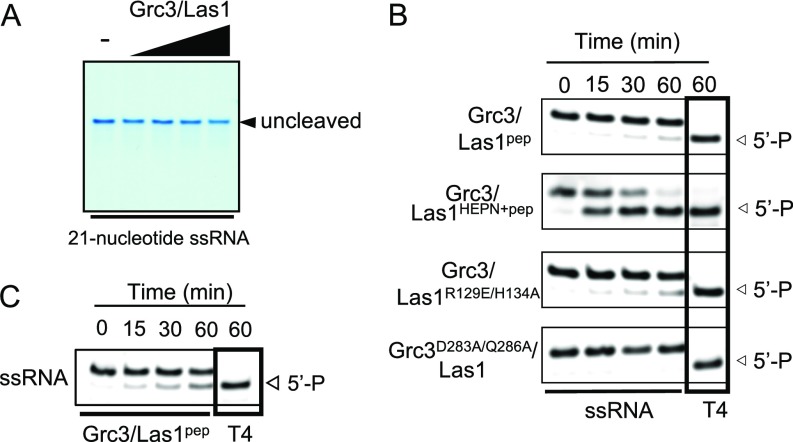

Higher-Order Assembly Facilitates Grc3/Las1 Cross Talk.

After determining that Grc3/Las1 assemble into a superdimer, we postulated that this higher-order assembly facilitates cross talk between the Las1 endoribonuclease and the Grc3 polynucleotide kinase. To assess the existence of functional interdependence, we performed in vitro endoribonuclease and kinase assays. The endoribonuclease activity of Grc3/Las1 is abolished when Las1 is restricted to its C-terminal Grc3-binding peptide (Grc3/Las1pep); however, this activity is rescued with the addition of the Las1 HEPN domain (Grc3/Las1HEPN+pep) (Fig. 4 A and B). Together, this reveals that the Las1 coiled-coil domain is dispensable for RNA cleavage in vitro. We interpret this to mean that Grc3 acts as a scaffold to help prime Las1HEPN for competent homodimerization and directs nuclease activity toward the C2 site. Furthermore, we also generated a kinase-deficient Grc3D283A/Q286A variant by mutating two residues within the Walker B motif, analogous to a kinase-deficient mutant of Clp1 (12). The kinase-deficient Grc3D283A/Q286A/Las1 superdimer had reduced endoribonuclease activity compared with wild-type Grc3/Las1 (Fig. 4 A and B). This implies that, beyond providing a scaffold, the Grc3 kinase actively relays a signal to Las1 that is necessary for efficient C2 cleavage.

Fig. 4.

Superdimer facilitates Grc3/Las1 cross talk. (A) Nuclease assay of Sc Grc3/Las1, Grc3/Las1pep, Grc3/Las1HEPN+pep, endonuclease-deficient Grc3/Las1R129E/H134A, and kinase-deficient Grc3D283A/Q286A/Las1 variants (2.5–20 μM) with model ITS2 RNA (10 μM). (B) Quantification of C2 RNA product generated from 10 μM Grc3/Las1 variants with model ITS2 RNA (10 μM). The mean and SD were calculated from three replicates. *P < 1 × 10−2; **P < 6 × 10−4; and n.s., not significant, were calculated by two-tailed Student’s t tests. (C) ATPase activity of Grc3/Las1 variants (0.5 μM) with 1 mM ATP in the absence and presence of single- or double-stranded 21-nt RNA substrate (4 μM). The mean percent ADP and SD was calculated from three replicates. *P < 3 × 10−3; **P < 2 × 10−7; ***P < 1 × 10−12; and n.s., not significant, were calculated from two-tailed Student’s t tests. (D) RNA phosphorylation activity of wild-type Grc3/Las1 (2 μM) with a labeled single-stranded (ss) or double-stranded (ds) 21-nt RNA substrate (15 μM). Positive controls include T4 polynucleotide kinase (T4). (E) Quantified phosphorylation activity of Grc3/Las1 variants (2 μM) with single-stranded 21-nt RNA. Mean and SD were calculated from three replicates.

This raised the question of whether Grc3/Las1 cross talk also influences 5′-phosphorylation following incision at the C2 site. Therefore, we carried out both ATP hydrolysis and phosphorylation assays with our Grc3/Las1 variants. We used a 21-nt RNA substrate for these assays that could not be cleaved by Las1 to avoid the potential for multiple phosphorylation events by Grc3 (Fig. S5A). We found that the ATPase activity of Grc3/Las1 is greatly stimulated in the presence of both single- and double-stranded RNA (Fig. 4C). However, in the presence of Las1, the Grc3 kinase exclusively phosphorylates single-strand RNA (Fig. 4D) and kinase activity was largely abolished when its Las1 binding partner was restricted to its C-terminal peptide (Grc3/Las1pep) (Fig. 4 C and E). We surmise this to be a functional consequence due to the loss of the superdimer as supplementing the reaction with the Las1 HEPN domain (Grc3/Las1HEPN+pep), which not only recovered higher-order assembly (Fig. 3C) but also rescued the ATPase and kinase activity by Grc3 (Fig. 4 C and E and Fig. S5B). These data suggest the possibility that Grc3 forms a composite kinase active site between two protomers or the superdimer imposes allosteric regulation, which is supported by detection of Grc3/Las1pep kinase activity of the monomeric complex at higher protein concentration (Fig. S5C). These results reveal that a Grc3 dimer is required to reconstitute a competent kinase, and thus, the Grc3/Las1HEPN+pep is the minimal functional unit for C2 cleavage and phosphorylation in vitro. However, this does not exclude the possibility that the Las1 C-terminal coiled-coil domain may play a role in binding other processing factors, such as the Rix1 complex (20).

Fig. S5.

Functional characterization of S. cerevisiae (Sc) Grc3/Las1 variants. (A) Sc Grc3/Las1 (5–40 μM) was incubated with a 21-nt ssRNA substrate (10 μM) in storage buffer for 1 h at 37 °C. Reactions were resolved on a 15% polyacrylamide (8 M urea) denaturing gel and stained with methylene blue. The 21-nt RNA substrate is refractory to Las1-directed cleavage and was used for ATPase and phosphorylation assays. (B) RNA phosphorylation activity of Grc3/Las1 variants (2 μM) with a labeled single-stranded (ss) or double-stranded (ds) 21-nt RNA substrate (15 μM). Positive controls include T4 polynucleotide kinase (T4). (C) Excess Sc Grc3/Las1pep (20 μM) was incubated with the 21-nt single-stranded RNA (15 μM) at 37 °C. RNA phosphorylation was observed at a high concentration of Sc Grc3/Las1pep.

To assess whether Grc3 requires endonuclease-active Las1, we measured the kinase activity of Grc3 in complex with the endoribonuclease-deficient Las1 variant (Grc3/Las1R129E/H134A). Intriguingly, Grc3 ATPase activity was no longer stimulated by RNA and showed a comparable reduction in 5′-phosphorylation activity as the kinase-deficient Grc3 variant (Grc3D283A/Q286A/Las1) (Fig. 4 C and E). Taken together, the presence of RNA transduces a signal from the Las1 endoribonuclease to Grc3, thereby stimulating its polynucleotide kinase activity. The Grc3/Las1 cross talk ensures high specificity and efficiency during pre-rRNA processing at the C2 site and is wholly dependent on the assembly of the superdimer.

Grc3 C Terminus Stabilizes Binding to the Las1 Endoribonuclease.

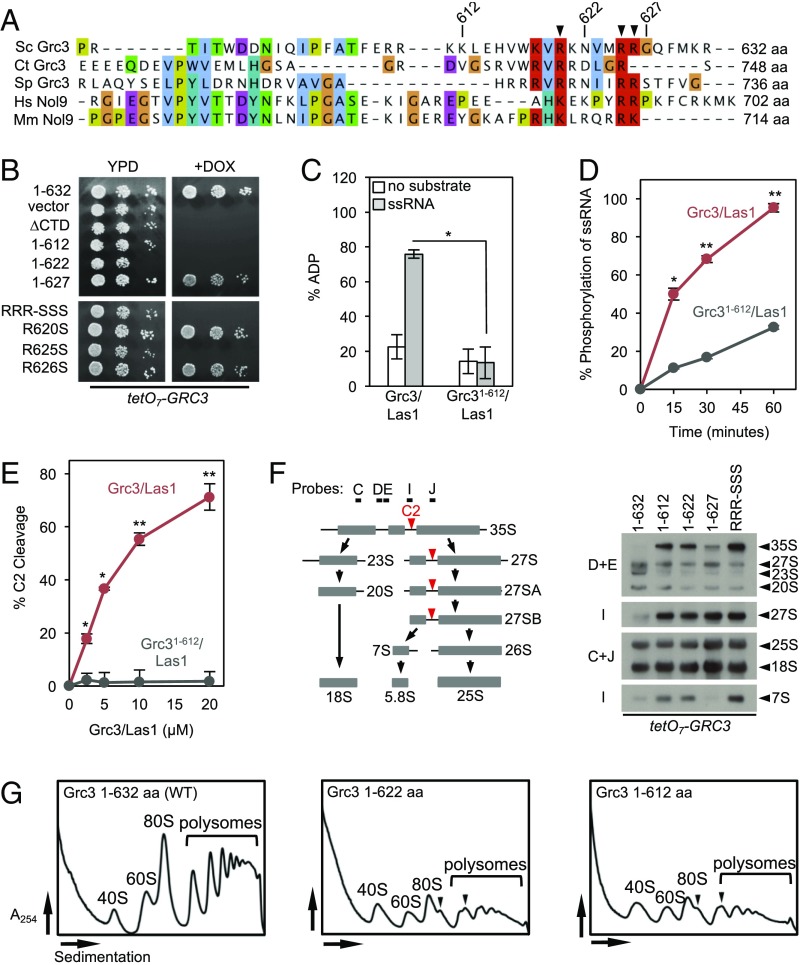

Aside from the PNK active site, we postulated that other regions of Grc3 may be important for facilitating Grc3/Las1 cross talk, and we observed that charged residues are enriched at the C terminus of Grc3 (Fig. 5A). To investigate the role of the basic residues within the C-terminal tail, we generated a series of Grc3 C-terminal variants and assessed their functional consequence in vivo. Removal of the last 5 residues (Grc31-627) had no effect on viability, whereas truncation of either the last 10 (Grc31-622) or 20 (Grc31-612) residues had a similar functional consequence to removing the entire C-terminal domain (Grc3ΔCTD) (Fig. 5B). Mutagenesis of three conserved C-terminal arginines (R620S, R625S, and R626S) identified R625 as a major player in maintaining cell viability (Fig. 5B). These Grc3 variants have a functional defect because there was no change in their expression levels in vivo (Fig. S6A) and the Grc3 C-terminal truncations could be stably expressed and purified for in vitro kinase assays. We measured ATP hydrolysis and 5′-phosphorylation activity of Grc31-612 in complex with Las1. Grc31-612/Las1 had a significant reduction in ATP hydrolysis and phosphorylation activity compared with wild-type Grc3/Las1 (Fig. 5 C and D and Fig. S6B). Likewise, Grc31-612/Las1 was completely deficient in C2 cleavage activity, reinforcing the importance of the Grc3 C terminus for pre-rRNA processing (Fig. 5E).

Fig. 5.

The C terminus of Grc3 is critical for Grc3/Las1 function. (A) Multiple sequence alignment of the C terminus of Grc3/Nol9 from different homologs of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Sc), Chaetomium thermophilum (Ct), Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Sp), Homo sapiens (Hs), and Mus musculus (Mm). The alignment was done in Tcoffee and colored with Jalview. The well-conserved arginine and lysine residues are highlighted in red. Arginines targeted for mutagenesis are marked by an arrowhead. (B) Yeast growth assay of Grc3 C-terminal mutants. TetO7-Grc3 transformants were plated on YPD plates in the absence and presence of 20 μg/mL doxycycline and incubated at 30 °C for 3 d. (C) ATPase assay of Grc3/Las1 variants (0.5 μM) with 1 mM ATP in the absence and presence of a 21-nt single-stranded RNA substrate (4 μM). Percent ADP and SD were derived from three replicates. *P < 5 × 10−3 was calculated by a two-tailed Student’s t test. (D) RNA phosphorylation activity of Grc3 variants (2 μM) bound by equimolar Las1 with a labeled single-stranded RNA substrate (15 μM). *P < 2 × 10−3; **P < 4 × 10−5, calculated by a two-tailed Student’s t test. (E) Nuclease assay of model ITS2 RNA (10 μM) with Sc Las1 (2.5–20 μM) associated with full-length equimolar Grc3 and Grc31-612. The mean and SD of C2 RNA product was calculated from three replicates. *P < 2 × 10−4; **P < 8 × 10−5 was determined by two-tailed Student’s t test. (F) Northern blot analysis of tetO7-Grc3 strains transformed with plasmids encoding Grc3 C-terminal mutants. The position of the Northern blot probes and the C2 cleavage site (red arrow) is shown on the cartoon schematic of the Sc pre-rRNA processing pathway. (G) Polysome profile analysis of wild-type and C-terminal–truncated Grc3 (residues 1–622 and 1–612). The black arrowheads mark ribosome halfmers.

Fig. S6.

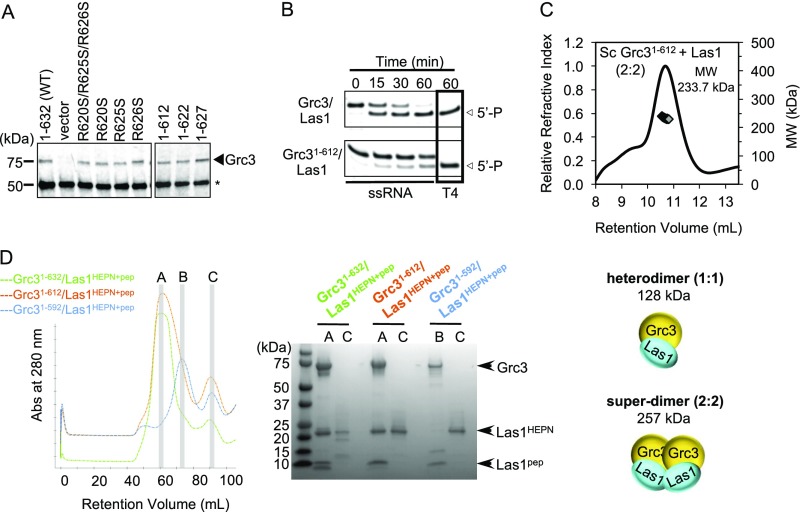

The Grc3 C terminus is critical for coordinating Las1HEPN binding. (A) Immunoblot analysis from the soluble fraction of tetO7-Grc3 transformants. Grc3 point mutants (R620S/R625S/R626S; R620S; R625S; R626S) and Grc3 C-terminal truncations (residues 1–612; 1–622; 1–627) had comparable expression to wild-type Grc3 (1–632 aa). The empty YCplac111 vector was used as a negative control. The asterisk marks a nonspecific band. (B) RNA phosphorylation activity of Grc3/Las1 variants (2 μM) with a labeled single-stranded 21-nt RNA substrate (15 μM). Positive controls include T4 polynucleotide kinase (T4). (C) SEC-MALS of the C-terminal–truncated S. cerevisiae (Sc) Grc3 (residues 1–612) bound to Las1. The measured molecular weight was 233.7 kDa. Cartoon schematic illustrating the Grc31-612/Las1 complex with 1:1 versus 2:2 stoichiometry. Expected molecular weights are indicated below each schematic. The observed mass corresponds to a Grc31-612/Las1 complex at 2:2 stoichiometry. (D) Size exclusion chromatography profiles (Left) of full-length Grc3 bound to Las1HEPN+pep (green) and C-terminal truncations of Grc3 (Grc31-612 in orange; Grc31-592 in blue) in the presence of Las1HEPN+pep. Fractions from the apex of peaks A, B, and C were resolved on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel (Right). Full-length Grc3 can retain Las1HEPN+pep, whereas the moderate C-terminal–truncated Grc31-612 has reduced affinity for Las1HEPN when resolved over a gel filtration column. The severe Grc31-592 C-terminal truncation is unable to retain Las1HEPN.

We speculated that the C terminus was necessary for proper assembly of the Grc3/Las1 superdimer, so we performed SEC-MALS to assess the stoichiometry of the Grc3 C-terminal truncation in complex with Las1. Unexpectedly, the Grc31-612/Las1 variant had a calculated molecular mass of 234 kDa, corresponding well to the superdimer (257 kDa), indicating that the C terminus is not required for higher-order assembly in vitro (Fig. S6C). We further truncated the C terminus of Grc31-592 and found that Las1HEPN could not be retained throughout the purification and the complex dissociates on a size exclusion column (Fig. S6D). Together, these data suggest that the C terminus of Grc3 is involved with proper organization of the Las1 HEPN domains within the Grc3/Las1 complex.

To ascertain the functional consequence of disrupting the C terminus of Grc3 in vivo, we monitored pre-rRNA processing by Northern blot analysis. Interestingly, both truncations and point mutations at the C terminus led to an accumulation of the 35S, 27S, and 7S precursor rRNA (Fig. 5F). The accumulation of 27S pre-rRNA underscores the importance of the Grc3 C terminus for C2 cleavage, whereas the abundance of the 7S confirmed previous findings suggesting a processing role for Las1 at the 3′-end of the 7S pre-rRNA (25). We also measured synthesis of ribosome particles by polysome profile analyses. Truncation of the C terminus of Grc3 resulted in a reduction in 60S particles and the formation of halfmers, indicative of a defect in formation of the 60S ribosomal particle (Fig. 5G). These data emphasize the essential role of the superdimer in mediating cross talk between Las1 and Grc3 during ribosome assembly.

Discussion

Recognition of the C2 Endonuclease Site.

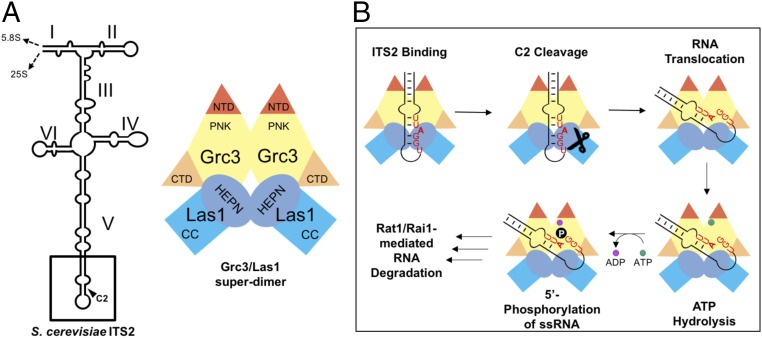

Our results provide the molecular details for understanding how the Grc3/Las1 superdimer recognizes the C2 site. The ITS2 is predicted to fold into six helical domains in either a ring or hairpin conformation (9), and the C2 cleavage site is found within the short conserved region that lies at the tip of domain V (Fig. 6A). We unambiguously mapped the cleavage site to an unpaired adenine (residue 140 of yeast ITS2) that lies immediately 5′ to the well-conserved tandem G–C base pairs previously shown to be critical for C2 cleavage (21, 22). This bulge may act as a marker for the C2 site because the presence of a bulge appears to be a universal feature of the ITS2 whereas the nature of the unpaired nucleotide is variable (26, 27). Our study suggests that the superdimer is the key factor for recognizing the RNA stem structure and surrounding RNA sequence. Consequently, Grc3 is critical in organizing a competent Grc3/Las1/ITS2 complex that promotes sequence and structure-specific Las1 cleavage at the C2 site.

Fig. 6.

Model of Grc3/Las1-directed C2 cleavage and phosphorylation. (A) Cartoon model of Sc ITS2, which was adapted from ref. 9. (B) Grc3/Las1 assembles into a constitutive superdimer, which is competent for C2 cleavage. Grc3/Las1 recognizes the sequence and secondary structure found at the tip of domain V and directs Las1 cleavage at the C2 site generating the 26S pre-rRNA with a 5′-OH. A conformational change repositions the 5′-OH into the Grc3 active site, thus stimulating Grc3 ATP hydrolysis and subsequent transfer of the γ-phosphate onto the 5′-end. This 5′-phosphate is the signal for Rat1-Rai1–mediated ITS2 degradation.

Model of C2 Cleavage by Grc3/Las1 Superdimer.

Based on our results, we propose the following model for Grc3/Las1-directed C2 cleavage and phosphorylation (Fig. 6B). Grc3 and Las1 form a constitutive superdimer composed of a dimer of Grc3/Las1. The Las1 HEPN endonuclease domain drives higher-order assembly; however, the PNK domain of Grc3 also participates in dimerization. Recognition of the C2 site requires formation of the superdimer as Las1 alone displays inefficient RNase activity. Several other HEPN endonucleases, including Ire1, RNaseL, C2c2, and Csm6, also require dimerization of their HEPN domains for function, suggesting that dimerization of the HEPN domain may be a common requirement for endonuclease activity (11, 28–31).

Following C2 cleavage, the 5′-OH at the end of the 26S pre-rRNA is phosphorylated by Grc3. We suggest that a conformational change within the superdimer repositions the cleaved RNA into the kinase-active site. Grc3 polynucleotide kinase activity is also dependent on formation of the superdimer, as Grc3 is inactive in the absence of the Las1 HEPN domain. The requirement for dimerization of the PNK domain of Grc3 for kinase activity suggests a similar mechanism to protein kinases such as the eIF2α kinase family, which rely on dimerization-induced allostery (32). Intriguingly, we also found that there is functional cross talk between Las1 and Grc3. The endonuclease-deficient Las1 mutant is deficient in polynucleotide kinase activity, suggesting that activation of Grc3 kinase activity requires an active Las1 endonuclease domain. Cross talk between an endonuclease and a polynucleotide kinase has also been observed between the mammalian tRNA splicing endonuclease complex (TSEN) and the Clp1 polynucleotide kinase. Clp1 is required for the integrity and nuclease activity of the TSEN complex; however, in contrast to Grc3, kinase activity of Clp1 is not dependent on the TSEN complex (13, 14, 33). Another example of molecular cross talk has been observed in mammalian polynucleotide kinase phosphatase, where mutations that ablate phosphatase activity also block kinase activity, ensuring that 5′-phosphorylation of damaged DNA does not occur before removal of 3′-adducts (34–36).

Functional Requirement for a Constitutive Grc3/Las1 Superdimer.

The demanding rate of ribosome production during a generation of yeast requires a highly active RNA Pol I with transcription rates of pre-rRNA at 40–60 nt/s (37, 38). To support this high production, pre-rRNA processing enzymes must be precisely and efficiently activated. An obligate Grc3/Las1 superdimer would aid in productive ITS2 processing by facilitating a quick response to the presence of 27S pre-rRNA. Although our work provides the basis for understanding cleavage and phosphorylation of the C2 site, there are many remaining questions about ITS2 processing. One of the major outstanding questions is when is the C2 site accessible for cleavage by the Grc3/Las1 superdimer. Several remodeling events have been suggested to be required to trigger C2 cleavage, including removal of early assembly factors and assembly of the peptidyl transferase center and polypeptide exit tunnel (recently reviewed in ref. 39). It is unclear how Grc3/Las1 function in concert with other ribosome assembly factors that have been shown to interact with Grc3 and Las1 including the Rix1 complex, Rat1, and Rai1 (4, 20). It also remains unknown how the 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate is removed from the 7S-pre-RNA following Las1 cleavage (4).

Grc3/Las1 Is a Unique Member of the Ire1/RNaseL Family.

Our results reveal many unexpected similarities between Grc3/Las1 and two other eukaryotic HEPN endoribonucleases, Ire1 and RNaseL. Ire1 is an ancient protein kinase–endoribonuclease conserved among eukaryotes that is activated during endoplasmic reticulum stress (28, 40). Meanwhile, RNaseL is a conserved pseudokinase–endoribonuclease that plays an essential role during the antiviral response (29, 30, 41). Both Ire1 and RNaseL form the Ire1/RNaseL family due to their similar mechanism in RNA cleavage and the combination of kinase and HEPN/kinase extension nuclease (KEN) domains (28). Ire1, RNaseL, and Grc3/Las1 share parallels that are paramount for productive endoribonuclease activity. All three endoribonucleases encode the conserved RΦxxxH motif linked to their RNA cleavage activity (10). Furthermore, they are functionally linked to a kinase domain that is critical for organizing a register of the HEPN/KEN homodimer productive in RNA cleavage activity. A unique feature of these endoribonucleases is the dependence of higher-order assembly to support functionality. In all three cases, assembly is supported by both the endoribonuclease and kinase domains. However, unlike Ire1 and RNaseL, which dimerize in the presence of a stress signal, Grc3/Las1 is a constitutive superdimer. This marks an important difference that has strong implications for its regulation. Consistent with this notion, Grc3 and Las1 are encoded on two distinct polypeptides, whereas Ire1 and RNaseL are a single polypeptide chain. Because Grc3 and Las1 are intimately dependent on the other for their stability (18), this provides an alternative mechanism for controlling the activity of Grc3/Las1. Taken together, Grc3/Las1 marks a unique subclass to Ire1/RNaseL endoribonucleases that support a similar mode of RNA cleavage, but is regulated through a signal-independent mechanism.

In conclusion, the evolutionarily conserved Grc3/Las1 complex is finely tuned to initiate ITS2 processing by coupling cleavage and phosphorylation to prime the 26S pre-rRNA for subsequent processing by Rat1/Rai1. The Grc3/Las1 superdimer is programmed for site-specific cleavage of the C2 site, representing a unique example of a “programmable endonuclease.” The Grc3/Las1 superdimer may prove useful as yet another tool in the arsenal of sequence-specific RNA endonucleases such as the CRISPR effectors. However, in contrast to the CRISPR RNA-guided endonucleases, the Grc3/Las1 complex is guided by protein–RNA interactions and could potentially be used to target RNAs for degradation by 5′- to 3′-exonucleases. Finally, as mutations in Las1L have been linked with neurological dysfunction, these studies lay the groundwork for understanding the functional significance of Las1 in vivo.

Methods

Detailed methods are available in SI Methods.

Protein Expression and Purification.

Grc3 and Las1 were coexpressed in Escherichia coli LOBSTR cells and purified by Talon affinity resin (Clontech) followed by size exclusion chromatography. All Grc3/Las1 variants used for SEC-MALS, enzymatic assays, and negative-stain electron microscopy are listed in Table S1.

Table S1.

Plasmids generated for bacterial expression

| Plasmid | Organism | GRC3 | LAS1 | Vector |

| pMP 001 | Sc Grc3/Las1 | 1–632 aa | 1–502 aa | pST39 |

| pMP 296 | Sc Grc3/Las1R129E/H134A | 1–632 aa | 1–502 aa (R129E/H134A) | pST39 |

| pMP 328 | Sc Grc31-612/Las1R129E/H134A | 1–612 aa | 1–502 aa (R129E/H134A) | pST39 |

| pMP 335 | Sc Grc3D283A/Q286A/Las1 | 1–632 aa (D283A/Q286A) | 1–502 aa | pST39 |

| pMP 290 | Sc Grc31-612/Las1 | 1–612 aa | 1–502 aa | pST39 |

| pMP 072 | Sc Grc3/Las1pep | 1–632 aa | 469–502 aa | pST39 |

| pMP 301 | Sc Grc3/Las1HEPN+pep | 1–632 aa | Strep-HEPN: 1–179 aa + His-peptide: 469–502 aa | pST39 |

| pMP 308 | Sc Grc31-612/Las1HEPN+pep | 1–612 aa | Strep-HEPN: 1–179 aa + His-peptide: 469–502 aa | pST39 |

| pMP 322 | Sc Grc31-592/Las1HEPN+pep | 1–592 aa | Strep-HEPN: 1–179 aa + His-peptide: 469–502 aa | pST39 |

| pMP 287 | Ct Grc3110-748/Las1 | 110–748 aa | 1–363 aa | pST39 |

| pMP 270 | Ct Grc3 PNK | 229–486 aa | N/A | pHMBP |

Yeast Analyses.

Yeast two-hybrid experiments, growth assays, Northern blots, and polysome profile assays were all carried out as described previously (18), and detailed methods are provided in SI Methods. Plasmids generated for yeast analyses are listed in Table S2, and all yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table S3. Probes used for Northern blots are listed in Table S4.

Table S2.

Yeast plasmids generated for this study

| Plasmid | Experiment | myc-GRC3 | myc-LAS1 | Vector |

| pMP 234 | Growth assay | 1–632 aa | N/A | YCplac111 |

| pMP 235 | Growth assay | 1–462 aa | N/A | YCplac111 |

| pMP 245 | Growth assay | 1–612 aa | N/A | YCplac111 |

| pMP 268 | Growth assay | 1–622 aa | N/A | YCplac111 |

| pMP 269 | Growth assay | 1–627 aa | N/A | YCplac111 |

| pMP 274 | Growth assay | R620S/R625S/R626S | N/A | YCplac111 |

| pMP 291 | Growth assay | R620S | N/A | YCplac111 |

| pMP 295 | Growth assay | R625S | N/A | YCplac111 |

| pMP 293 | Growth assay | R626S | N/A | YCplac111 |

| pMP 213 | Y2H (bait) | 1–632 aa | N/A | pGBKT7 |

| pMP 209 | Y2H (prey) | N/A | 1–502 aa | pGADT7 |

| pMP 229 | Y2H (prey) | N/A | 1–179 aa | pGADT7 |

| pMP 243 | Y2H (prey) | N/A | 180–502 aa | pGADT7 |

| pMP 230 | Y2H (prey) | N/A | 1–472 aa | pGADT7 |

| pMP 231 | Y2H (prey) | N/A | 180–472 aa | pGADT7 |

| pMP 208 | Y2H (prey) | N/A | 450–502 aa | pGADT7 |

Table S3.

Yeast strains used and constructed in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

| tetO7-Grc3 | URA::CMV-tTA Grc3::kanR-tetO7-TATA MATa his3-1 leu2-0 met15-0 | Tet-Promoter Hughes Collection (GE Dharmacon) |

| tetO7-Grc3 +pMP234 | URA::CMV-tTA Grc3::kanR-tetO7-TATA MATa his3-1 leu2-0 met15-0; pMP234 (Myc-Grc3) | This study |

| tetO7-Grc3+ pMP235 | URA::CMV-tTA Grc3::kanR-tetO7-TATA MATa his3-1 leu2-0 met15-0; pMP235 (Myc-Grc3, 1–432) | This study |

| tetO7-Grc3+ pMP245 | URA::CMV-tTA Grc3::kanR-tetO7-TATA MATa his3-1 leu2-0 met15-0; pMP245 (Myc-Grc3, 1–612) | This study |

| tetO7-Grc3 + pMP268 | URA::CMV-tTA Grc3::kanR-tetO7-TATA MATa his3-1 leu2-0 met15-0; pMP268 (Myc-Grc3, 1–622) | This study |

| tetO7-Grc3 + pMP269 | URA::CMV-tTA Grc3::kanR-tetO7-TATA MATa his3-1 leu2-0 met15-0; pMP269 (Myc-Grc3, 1–627) | This study |

| tetO7-Grc3 + pMP274 | URA::CMV-tTA Grc3::kanR-tetO7-TATA MATa his3-1 leu2-0 met15-0; pMP274 (Myc-Grc3, R620S/R625S/R626S) | This study |

| tetO7-Grc3 + pMP291 | URA::CMV-tTA Grc3::kanR-tetO7-TATA MATa his3-1 leu2-0 met15-0; pMP291 (Myc-Grc3, R620S) | This study |

| tetO7-Grc3 + pMP295 | URA::CMV-tTA Grc3::kanR-tetO7-TATA MATa his3-1 leu2-0 met15-0; pMP295 (Myc-Grc3, R625S) | This study |

| tetO7-Grc3 + pMP293 | URA::CMV-tTA Grc3::kanR-tetO7-TATA MATa his3-1 leu2-0 met15-0; pMP293 (Myc-Grc3, R626S) | This study |

Table S4.

DIG probes for Northern blots

| Probe | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Ref. |

| C | CAGAAGGAAAGGCCCCGTTGGAAATCCAGTACACGAAAAAATCGGACCGG/3Dig_N/ | 18 |

| D | GAAAGAAACTTCACAGCCTAGCAAGACCGCGCACTTAAGCGCAGGCCCGG/3Dig_N/ | 18 |

| E | TACCTCTGGGCCCCGATTGCTCGAATGCCCAAAGAAAAAGTTGCAAAGAT/3Dig_N/ | 18 |

| I | TCCAATGAAAAGGCCAGCAATTTCAAGTTAACTCCAAAGAGTATCACTCA/3Dig_N/ | 18 |

| J | TTCCCAAACAACTCGACTCTTCGAAGGCACTTTACAAAGAACCGCACTCC/3Dig_N/ | 18 |

Nuclease and Phosphorylation Assays.

RNA cleavage products were resolved on 15% polyacrylamide (8 M urea) gels in 1× Tris–borate–EDTA buffer. ATP hydrolysis was measured using a Kinase Glo Kit (Promega), and RNA phosphorylation was resolved on a 15% polyacrylamide (8 M urea) gel in 0.5× Tris–borate–EDTA buffer using a labeled RNA substrate.

SI Methods

Cloning of Grc3 and Las1 Variants.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Sc) Grc3/Las1 (pMP 001) was generated by amplifying full-length Grc3 (residues 1–632) and Las1 (residues 1–502) from Sc genomic DNA. A 6× His tag-tobacco etch virus (TEV) recognition sequence was added upstream to Las1. Grc3 and His-TEV-Las1 were inserted into the bacterial coexpression pST39 vector (42) using KpnI/XhoI and EcoRI/StuI, respectively. All Grc3/Las1 variants (Table S1) were made by Q5 site-directed mutagenesis (NEB) using pMP 001 as a template. Full-length codon-optimized Chaetomium thermophilum (Ct) Grc3 (residues 1–748) and Las1 (residues 1–363) were obtained from GenScript. A 6× His-TEV sequence was added upstream to Ct Las1. The first 109 residues of Ct Grc3 were removed for expression purposes. Ct Grc3110-748/Las1 (pMP 287) was generated by inserting Grc3 (residues 110–748) and His-TEV-Las1 into pST39 between BamHI/NotI and KpnI/XhoI, respectively. Ct Grc3 PNK (pMP 270; residues 229–486) was amplified by PCR and inserted into pHMBP (43) at BamHI by In-Fusion (Clontech).

Plasmids used for yeast proliferation assays are listed in Table S2. N-terminal myc-tagged Grc3 (pMP 234) was amplified along with 300 nt of flanking endogenous DNA sequence and inserted between KpnI/SacI in YCplac111 (44). Variants were generated by Q5 site-directed mutagenesis (NEB) using pMP 234 as a template. Yeast two-hybrid vectors were acquired from Matchmaker Gold Yeast Two-Hybrid System (Clontech). Full-length Sc Grc3 was inserted into pGBKT7 between BamHI/EcoRI to generate the bait plasmid (pMP 213, residues 1–632). The prey plasmid was created similarly with Sc Las1 in pGADT7 (pMP 209, residues 1–502). Two-hybrid prey constructs expressing various Las1 truncations were generated similarly and listed in Table S2. All plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing (GeneWiz).

Yeast Two-Hybrid.

The bait plasmid (Table S2) was transformed into the Sc Y2HGold strain, whereas prey plasmids were transformed into the Sc Y187 strain (Clontech). Bait and prey strains were mated overnight at 30 °C. Mated cultures were grown on SD/−Leu/−Trp and SD/−Leu/−Trp/−His at 30 °C for 3–4 d. Control plasmids pGBKT7-53, pGADT7-T, and pGBKT7-Lam were used as positive and negative controls as per manufacturer’s instructions (Clontech).

Yeast Growth Conditions and Proliferation Assay.

The Sc strain with the endogenous GRC3 promoter exchanged for a tetracycline-titratable promoter (tetO7) was obtained from Open Biosystems (GE Dharmacon). Endogenous Grc3 expression was down-regulated in tetO7-GRC3 by the addition of 20 μg/mL doxycycline to YPD media. For cell proliferation assays, transformed tet strains were plated on YPD in the absence and presence of doxycycline and incubated at 30 °C for 3 d.

RNA Isolation and Northern Blot Analysis.

Tet strains (Table S3) were grown in the presence of doxycycline as described above, and RNA was isolated by phenol-chloroform extraction. RNA (3 μg) was resolved over a 1% formaldehyde agarose gel and transferred onto Hybond XL membrane (GE Healthcare). RNA blots were fixed and hybridized with DIG-conjugated DNA probes where the nucleotide sequences were described previously (18) (Table S4). Blots were visualized by immunological detection with anti-digoxigenin–AP (Sigma) as per manufacturer instructions.

Sucrose Gradient and Ribosome Profiling.

Cultures of tetO7-GRC3 (Table S3) were grown at 30 °C in the presence of 20 μg/mL doxycycline to OD ∼0.5. Cycloheximide (0.1 mg/mL) was added to the cultures and incubated for 5 min on ice before harvesting cells. Ribosome profiling was conducted as described previously with minor modifications (45). Briefly, cells were resuspended in extraction buffer [20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 60 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1% (vol/wt) Triton X-100, 0.1 mg/mL cycloheximide, 0.2 mg/mL heparin (ammonium salt)] and disrupted using glass beads for 5 min at 4 °C. Lysate was clarified at 8,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C and 0.8 mg of RNA was loaded onto a 7–47% sucrose gradient. Gradients were subjected to 260,110 × g for 2.5 h at 4 °C and immediately loaded onto a gradient fractionator (Brandel).

Protein Expression and Purification.

Grc3/Las1 variants were overproduced in E. coli LOBSTR cells (Kerafast) induced with 1 mM IPTG and incubated overnight at 18 °C. Cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol) and disrupted by sonication. Lysate was clarified at 26,916 × g for 50 min at 4 °C and applied to a gravity flow column loaded with TALON metal affinity resin (Clontech). Grc3/Las1 variants were eluted using 200 mM imidazole and resolved over a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex-200 Prep Grade (GE Healthcare) gel filtration column equilibrated with storage buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol). Sc Las1 and Sc Las1R129E/H134A were acquired from distinct peaks of excess Las1 following size exclusion chromatography of Sc Grc31-612/Las1 (pMP 290) and ScGrc31-612/Las1R129E/H134A (pMP 328), respectively. Sc Las1 and Sc Las1R129E/H134A were further purified using a His-Trap High Performance column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, and 5% glycerol. Sc Las1 variants were eluted with 200 mM imidazole and exchanged into storage buffer using a 10,000 NMWL centrifugal filter (Millipore). Pure His-MBP–tagged Ct Grc3 PNK was incubated with TEV protease (1:100) overnight at 4 °C. Reaction mixture was loaded onto a His-Trap High Performance (GE Healthcare) column equilibrated with 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, and 5% glycerol. Tagless Ct Grc3 PNK was eluted using 45 mM imidazole and resolved over a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex-75 Prep Grade (GE Healthcare) gel filtration column equilibrated with storage buffer.

SEC-MALS.

Sc Grc3/Las1 (20 μM), Sc Grc3/Las1HEPN+pep (20 μM), Sc Grc3/Las1pep (80 μM), Sc Las1HEPN (174 μM), Sc Grc31-612/Las1 (23 μM), Ct Grc3110-748/Las1 (80 μM), and tagless Ct Grc3 PNK (200 μM) were assessed by SEC-MALS using an AKTA FPLC system (GE Healthcare) coupled to the miniDawn TREOS and Optilab rEX detectors (Wyatt Technology). A Superdex-200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) was used for protein separation using storage buffer. All data were analyzed using the ASTRA 5.3.4 software (Wyatt Technology).

SAXS Data Collection and Processing.

Tagless Ct Grc3 PNK (229-486 aa) was resolved over a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex-75 prep grade (GE Healthcare) size exclusion chromatography column using storage buffer. Sample monodispersity was confirmed by dynamic light scattering (Wyatt Technology). Protein samples were spun at 3,200 × g for 10 min at 4 °C before recording solution scattering at the Advanced Light Source, SIBYLS beamline 12.3.1 at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (46). Thirty-three consecutive scans of 0.3 s were collected over a protein concentration series (1–12 mg/mL) at 10 °C. Radiation damage was monitored over time by comparing solution scattering of individual frames using the ATSAS 2.8.0 program suite (47). The reported molecular weights were calculated based on the volume of correlation (48).

In Vitro ATPase and Phosphorylation Assays.

ATP hydrolysis assays were performed with Grc3/Las1 variants (0.5 μM) in ATPase reaction buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM β-ME, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mg/mL BSA, 5% glycerol, 1 mM ATP) with and without a 21-nt RNA (5′-UUCGAAGUAUUCCGCGUACGU-3′) substrate (4 μM). Reaction mixtures were incubated for 60 min at 37 °C before adding two times Kinase-Glo reagent (Promega). Luminescence was measured on a Tecan using a 1-s integration time following a 10-min incubation at room temperature.

Gel-based phosphorylation assays were performed with 2 μM Grc3/Las1 variants and 15 μM fluorescently labeled RNA (5′-UUCGAAGUAUUCCGCGUACGU-TAMRA-3′) in kinase reaction buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 15 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM ATP). Positive control reaction mixtures contained 10 units of T4 polynucleotide kinase (NEB). Phosphorylation reactions were incubated for 15, 30, and 60 min at 37 °C and quenched by adding two times urea loading dye (20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 8 M urea, 0.05% bromophenol blue, 1 mM EDTA). Reaction mixtures were boiled and loaded onto a 15% polyacrylamide (8 M urea) gel in 0.5× Tris–borate–EDTA buffer. Gels were visualized on a Typhoon FLA 9500 (GE Healthcare). All phosphorylation reactions were done in triplicate, and representative gels are shown in the figures.

In Vitro Endonuclease Assay.

Las1 endoribonuclease activity was assessed using a 27-nt RNA hairpin substrate (10 μM) encoding the C2 cleavage site from the Sc ITS2 (5′-GUCGUUUUAGGUUUUACCAACUGCGGC-3′). Modified RNA substrates (i) A140C (5′-GUCGUUUUCGGUUUUACCAACUGCGGC-3′), (ii) ∆A140 (5′-GUCGUUUUGGUUUUACCAACUGCGGC-3′), (iii) U-A/C-G (5′-GUCGUUCCAGGUUUUACCGGCUGCGGC-3′), (iv) stem sequence (5′-CGAUUUUUAGGUUUUACCAACUGCGGC-3′), and (v) stem structure (5′-GUCGUUUUAGGUUUUAGGAACUCGCCG-3′) were used, where indicated. Las1 variants (2.5–40 μM) were incubated with RNA (10 μM) in the absence and presence of equimolar Grc3 in storage buffer for 60 min at 37 °C. Reactions containing Sc Las1 and Las1R129E/H134A variants alone were supplemented with excess EDTA (5 mM), whereas samples with Grc3/Las1 variants were incubated with excess nucleotide (1 mM) and EDTA (5 mM), where indicated. Two times urea loading dye was added to reaction mixtures, boiled, and resolved on 15% polyacrylamide (8 M urea) gels in 1× Tris–borate–EDTA buffer. Model RNA substrates were visualized by methylene blue. All endonuclease assays were done in triplicate, and representative gels are shown in the figures.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis of C2 Cleavage Product.

Grc3/Las1 (40 μM) was incubated with 10 μM C2 RNA ITS2 substrate for 1 h at 37 °C in storage buffer. Immediately following the incubation, the reaction was desalted with a C18 ZipTip (Millipore) by first wetting the tip with acetonitrile followed by equilibration with 10 MΩ water (Hydo). The sample was absorbed to the tip by pipetting up and down across the tip seven times, followed by washing seven times with 20 μL of 18 MΩ water. The sample was eluted with 4 μL of 30:70 (vol/vol) water:acetonitrile. A volume of 0.5 μL of the sample was spotted onto a stainless-steel MALDI target and mixed on-target with 0.5 μL of 8 mg/mL 2′,4′,6′-trihydroxyacetophenome monohydrate and 10 mg/mL diammonium citrate in 60:40 (vol/vol) water:acetonitrile and allowed to dry at room temperature. Data were acquired on an Applied Biosystems 4800 Plus MALDI TOF/TOF Analyzer in the linear and negative ion modes. The instrument was externally calibrated on the (M-H)1- ions (average mass) of Angiotensin II (m/z 1045.2), Angiotensin I (m/z 1395.5), ACTH 1–17 (m/z 2092.5), and ACTH 18–39 (m/z 2464.7).

Western Blot of Endogenous myc-Grc3 Variants.

Sc tetO7-Grc3 transformants were grown as described in Yeast Growth Conditions and Proliferation Assay. Whole-cell extracts were obtained from a 50-mL culture at midlog phase resuspended in 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, and 1× protease inhibitor mixture (Roche). Cells were lysed with 1/2 vol of glass beads and disrupted for 10 min at 4 °C. Lysate was clarified at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The soluble fraction was incubated with anti–c-myc magnetic beads (Pierce) for 30 min at 4 °C, and resin was washed with wash buffer (125 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 750 mM NaCl, 0.25% Tween-20). Resin was loaded on a 4–15% polyacrylamide denaturing gel, and myc-Grc3 was visualized using an anti-myc antibody (Millipore).

Electron Microscopy and Image Processing.

Purified Ct Grc3110-748/Las1 was resolved over an analytical Superose 6 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) using storage buffer. Sample was diluted to a final concentration of 15 μg/mL and prepared for negative stain as described (49) using sample buffer instead of water for the washes. Negatively stained specimens were imaged in a Tecnai 12 electron microscope (FEI Company) equipped with a Lab6 electron source and operated at 120 kV. A total of 1,260 micrographs was automatically collected under low-dose conditions using EPU (FEI Company) at a nominal magnification of 67,000×. Underfocused images (1–3 μm) were recorded on a US4000 CCD camera (Gatan) with a pixel size at the specimen level of 1.77 Å. The contrast transfer function (CTF) of the images was determined using ctffind4 (50). A total of 26,641 putative particles were selected from a subset of 118 highest quality images determined by the following criteria: visual assessment (protein dispersion, quality of stain, and background), astigmatism based on a 50-nm cutoff for the difference in maximum and minimum defocus; and amplitude of signal and correlation with the expected CTF in the frequency range of 50–10 Å. All further processing was performed within the framework of EMAN 2.12 (51). Particles were extracted with a box size of 192 pixels, CTF corrected, and pooled in a set. Reference-free classification of down-sampled and low-pass–filtered (16-Å) images was used to eliminate “bad” particles and false positives resulted in a “cleaned” dataset of 16,442 molecular images. This set was subject to a second round of classification, and classes were selected and used to build an initial 3D reference map. This map was further refined against the cleaned dataset using the e2refine_easy.py routine in EMAN2.12. The 3D projection maps were rendered in Chimera (52).

Acknowledgments

We thank the scientific staff at the Structurally Integrated Biology for Life Sciences (SIBYLS) high-throughput SAXS Advanced Light Source (ALS) in Berkeley for technical support. We are grateful to Robert Dutcher for assistance with SEC-MALS analysis and Ms. Andrea Adams and Ms. Katina Johnson of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) Mass Spectrometry Research and Support Group for help with protein identification. We also thank Dr. R. Scott Williams, Dr. Thomas Kunkel, and Dr. Traci Hall for their critical reading of this manuscript. This work was supported by the NIH Intramural Research Program, NIEHS Grant ZIA ES103247 (to R.E.S.), and Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Grant 146626 (to M.C.P.). Use of the ALS was supported by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the US Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC02-05CH11231. Additional support for the SIBYLS SAXS beamline comes from NIH Project MINOS (R01GM105404) and High-End Instrumentation Grant S10OD01848.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The low-resolution negative-stain electron microscopy map reported in this paper has been deposited in the EMDataBank, www.emdatabank.org (accession no. EMD-8766).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1703133114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Yang W. Nucleases: Diversity of structure, function and mechanism. Q Rev Biophys. 2011;44:1–93. doi: 10.1017/S0033583510000181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hochstrasser ML, Doudna JA. Cutting it close: CRISPR-associated endoribonuclease structure and function. Trends Biochem Sci. 2015;40:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohanraju P, et al. Diverse evolutionary roots and mechanistic variations of the CRISPR-Cas systems. Science. 2016;353:aad5147. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gasse L, Flemming D, Hurt E. Coordinated ribosomal ITS2 RNA processing by the Las1 complex integrating endonuclease, polynucleotide kinase, and exonuclease activities. Mol Cell. 2015;60:808–815. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butterfield RJ, et al. Congenital lethal motor neuron disease with a novel defect in ribosome biogenesis. Neurology. 2014;82:1322–1330. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu H, et al. X-exome sequencing of 405 unresolved families identifies seven novel intellectual disability genes. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:133–148. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomson E, Ferreira-Cerca S, Hurt E. Eukaryotic ribosome biogenesis at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:4815–4821. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woolford JL, Jr, Baserga SJ. Ribosome biogenesis in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2013;195:643–681. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.153197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernández-Pevida A, Kressler D, de la Cruz J. Processing of preribosomal RNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2015;6:191–209. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anantharaman V, Makarova KS, Burroughs AM, Koonin EV, Aravind L. Comprehensive analysis of the HEPN superfamily: Identification of novel roles in intra-genomic conflicts, defense, pathogenesis and RNA processing. Biol Direct. 2013;8:15. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-8-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu L, et al. Two distant catalytic sites are responsible for C2c2 RNase activities. Cell. 2017;168:121–134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dikfidan A, et al. RNA specificity and regulation of catalysis in the eukaryotic polynucleotide kinase Clp1. Mol Cell. 2014;54:975–986. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karaca E, et al. Baylor Hopkins Center for Mendelian Genomics Human CLP1 mutations alter tRNA biogenesis, affecting both peripheral and central nervous system function. Cell. 2014;157:636–650. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schaffer AE, et al. CLP1 founder mutation links tRNA splicing and maturation to cerebellar development and neurodegeneration. Cell. 2014;157:651–663. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braglia P, Heindl K, Schleiffer A, Martinez J, Proudfoot NJ. Role of the RNA/DNA kinase Grc3 in transcription termination by RNA polymerase I. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:758–764. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heindl K, Martinez J. Nol9 is a novel polynucleotide 5′-kinase involved in ribosomal RNA processing. EMBO J. 2010;29:4161–4171. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noble CG, Beuth B, Taylor IA. Structure of a nucleotide-bound Clp1-Pcf11 polyadenylation factor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:87–99. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castle CD, et al. Las1 interacts with Grc3 polynucleotide kinase and is required for ribosome synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:1135–1150. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCann KL, Charette JM, Vincent NG, Baserga SJ. A protein interaction map of the LSU processome. Genes Dev. 2015;29:862–875. doi: 10.1101/gad.256370.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castle CD, Cassimere EK, Denicourt C. LAS1L interacts with the mammalian Rix1 complex to regulate ribosome biogenesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:716–728. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-06-0530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Nues RW, Venema J, Rientjes JM, Dirks-Mulder A, Raué HA. Processing of eukaryotic pre-rRNA: The role of the transcribed spacers. Biochem Cell Biol. 1995;73:789–801. doi: 10.1139/o95-087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Nues RW, et al. Evolutionarily conserved structural elements are critical for processing of internal transcribed spacer 2 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae precursor ribosomal RNA. J Mol Biol. 1995;250:24–36. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geerlings TH, Vos JC, Raué HA. The final step in the formation of 25S rRNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is performed by 5′→3′ exonucleases. RNA. 2000;6:1698–1703. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200001540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Granneman S, Petfalski E, Tollervey D. A cluster of ribosome synthesis factors regulate pre-rRNA folding and 5.8S rRNA maturation by the Rat1 exonuclease. EMBO J. 2011;30:4006–4019. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schillewaert S, Wacheul L, Lhomme F, Lafontaine DL. The evolutionarily conserved protein Las1 is required for pre-rRNA processing at both ends of ITS2. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:430–444. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06019-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Sande CA, et al. Functional analysis of internal transcribed spacer 2 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae ribosomal DNA. J Mol Biol. 1992;223:899–910. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90251-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joseph N, Krauskopf E, Vera MI, Michot B. Ribosomal internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) exhibits a common core of secondary structure in vertebrates and yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:4533–4540. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.23.4533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee KP, et al. Structure of the dual enzyme Ire1 reveals the basis for catalysis and regulation in nonconventional RNA splicing. Cell. 2008;132:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han Y, et al. Structure of human RNase L reveals the basis for regulated RNA decay in the IFN response. Science. 2014;343:1244–1248. doi: 10.1126/science.1249845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang H, et al. Dimeric structure of pseudokinase RNase L bound to 2-5A reveals a basis for interferon-induced antiviral activity. Mol Cell. 2014;53:221–234. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niewoehner O, Jinek M. Structural basis for the endoribonuclease activity of the type III-A CRISPR-associated protein Csm6. RNA. 2016;22:318–329. doi: 10.1261/rna.054098.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lavoie H, Li JJ, Thevakumaran N, Therrien M, Sicheri F. Dimerization-induced allostery in protein kinase regulation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2014;39:475–486. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weitzer S, Hanada T, Penninger JM, Martinez J. CLP1 as a novel player in linking tRNA splicing to neurodegenerative disorders. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2015;6:47–63. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bernstein NK, et al. The molecular architecture of the mammalian DNA repair enzyme, polynucleotide kinase. Mol Cell. 2005;17:657–670. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coquelle N, Havali-Shahriari Z, Bernstein N, Green R, Glover JN. Structural basis for the phosphatase activity of polynucleotide kinase/phosphatase on single- and double-stranded DNA substrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:21022–21027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112036108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schellenberg MJ, Williams RS. DNA end processing by polynucleotide kinase/phosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:20855–20856. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118214109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.French SL, Osheim YN, Cioci F, Nomura M, Beyer AL. In exponentially growing Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells, rRNA synthesis is determined by the summed RNA polymerase I loading rate rather than by the number of active genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:1558–1568. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.5.1558-1568.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kos M, Tollervey D. Yeast pre-rRNA processing and modification occur cotranscriptionally. Mol Cell. 2010;37:809–820. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Konikkat S, Woolford JL., Jr Principles of 60S ribosomal subunit assembly emerging from recent studies in yeast. Biochem J. 2017;474:195–214. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sidrauski C, Walter P. The transmembrane kinase Ire1p is a site-specific endonuclease that initiates mRNA splicing in the unfolded protein response. Cell. 1997;90:1031–1039. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80369-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou A, Hassel BA, Silverman RH. Expression cloning of 2-5A-dependent RNAase: A uniquely regulated mediator of interferon action. Cell. 1993;72:753–765. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90403-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tan S. A modular polycistronic expression system for overexpressing protein complexes in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr Purif. 2001;21:224–234. doi: 10.1006/prep.2000.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheffield P, Garrard S, Derewenda Z. Overcoming expression and purification problems of RhoGDI using a family of “parallel” expression vectors. Protein Expr Purif. 1999;15:34–39. doi: 10.1006/prep.1998.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gietz RD, Sugino A. New yeast-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized yeast genes lacking six-base pair restriction sites. Gene. 1988;74:527–534. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mašek T, Valášek L, Pospíšek M. Polysome analysis and RNA purification from sucrose gradients. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;703:293–309. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-248-9_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dyer KN, et al. High-throughput SAXS for the characterization of biomolecules in solution: A practical approach. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1091:245–258. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-691-7_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Petoukhov MV, et al. New developments in the ATSAS program package for small-angle scattering data analysis. J Appl Cryst. 2012;45:342–350. doi: 10.1107/S0021889812007662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rambo RP, Tainer JA. Accurate assessment of mass, models and resolution by small-angle scattering. Nature. 2013;496:477–481. doi: 10.1038/nature12070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Booth DS, Avila-Sakar A, Cheng Y. Visualizing proteins and macromolecular complexes by negative stain EM: From grid preparation to image acquisition. J Vis Exp. 2011;58:e3227. doi: 10.3791/3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rohou A, Grigorieff N. CTFFIND4: Fast and accurate defocus estimation from electron micrographs. J Struct Biol. 2015;192:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tang G, et al. EMAN2: An extensible image processing suite for electron microscopy. J Struct Biol. 2007;157:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]