Abstract

Regulated exocytosis is subject to several modulatory steps that include phosphorylation events and transient protein–protein interactions. The estrogen receptor-binding fragment-associated gene9 (EBAG9) gene product was recently identified as a modulator of tumor-associated O-linked glycan expression in nonneuronal cells; however, this molecule is expressed physiologically in essentially all mammalian tissues. Particular interest has developed toward this molecule because in some human tumor entities high expression levels correlated with clinical prognosis. To gain insight into the cellular function of EBAG9, we scored for interaction partners by using the yeast two-hybrid system. Here, we demonstrate that EBAG9 interacts with Snapin, which is likely to be a modulator of Synaptotagmin-associated regulated exocytosis. Strengthening of this interaction inhibited regulated secretion of neuropeptide Y from PC12 cells, whereas evoked neurotransmitter release from hippocampal neurons remained unaltered. Mechanistically, EBAG9 decreased phosphorylation of Snapin; subsequently, association of Snapin with synaptosome-associated protein of 25 kDa (SNAP25) and SNAP23 was diminished. We suggest that the occurrence of SNAP23, Snapin, and EBAG9 also in nonneuronal cells might extend the modulatory role of EBAG9 to a broad range of secretory cells. The conjunction between EBAG9 and Snapin adds an additional layer of control on exocytosis processes; in addition, mechanistic evidence is provided that inhibition of phosphorylation has a regulatory function in exocytosis.

INTRODUCTION

The secretion of biomolecules in many types of eukaryotic cells is mediated through both the constitutive and regulated transport of vesicles (Burgess and Kelly, 1987). Whereas constitutive exocytosis involves a continuous flow and fusion of vesicles between cellular organelles and to the plasma membrane, regulated exocytosis is characterized by vesicle trafficking, followed by vesicle fusion with the target membrane only in the presence of elevated levels of cytoplasmic Ca2+ (Burgoyne and Morgan, 2003). The best studied variant of regulated exocytosis includes the synaptic transmission in neuronal and neuroendocrine cells, where upon arrival of Ca2+ trigger neurotransmitter release from preformed vesicles is effectuated (Chen et al., 1999; Jahn and Südhof, 1999; Rettig and Neher, 2002).

Consent has emerged that vesicle fusion with a target membrane is a stepwise process that involves several protein families, including soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptors (SNAREs), Rab proteins, and Sec1/Munc-18–related molecules (Jahn and Südhof, 1999). The synaptic vesicle cycle starts with the tethering and docking of vesicles in the active zones of the plasma membrane, followed by a priming step that includes the formation of a SNARE complex (Südhof, 1995; Fernandez-Chacon and Südhof, 1999). SNAREs are a superfamily of small and mostly membrane-anchored proteins that share a common motif of ∼60 amino acids. A functional neuronal SNARE complex in cells is formed between SNARE proteins residing in vesicle membranes, including vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP), and the plasma membrane with the t-SNARE proteins Syntaxin and synaptosome-associated protein of 25 kDa (SNAP25) (Söllner et al., 1993; Sutton et al., 1998).

The candidate Ca2+ sensor Synaptotagmin I is localized to synaptic vesicles and large dense-core vesicles (LDCVs) (Brose et al., 1992; Geppert et al., 1994). Synaptotagmin I acts at a postdocking step in exocytosis, including a maturation step of primed vesicles into the readily releasable pool (RRP) of vesicles (Voets et al., 2001), but also a final fusion-pore opening stage (Wang et al., 2001; Chapman, 2002). Recently, a novel SNAP25-interacting protein, Snapin, was identified. It was suggested that cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA)-mediated phosphorylation of Snapin enhanced binding to SNAP25. This interaction improved the binding affinity of Synaptotagmin I to SNAP25 and the SNARE complex in vitro. By using a phosphomimetic mutant of Snapin, not only an increase in size of the exocytotic burst but also an enhanced sustained component of exocytosis in chromaffin cells was seen (Ilardi et al., 1999; Chheda et al., 2001). In support of a more general role in intracellular membrane fusion events, additional Snapin-interacting proteins were identified that are not limited to neuronal transmitter release, among them novel subunits of the biogenesis of lysosome-related organelles complex-1 (BLOC-1) and adenylyl cyclase VI (Chou et al., 2004; Starcevic and Dell'Angelica, 2004).

In this study, we refer to our previous report on estrogen receptor-binding fragment-associated gene9 (EBAG9), also termed receptor-binding cancer antigen expressed on SiSo cells (RCAS1), which caused the occurrence of tumor-associated O-linked glycans on cell lines that are normally negative for these antigens. EBAG9 is an estrogen-inducible, ubiquitously expressed protein with close homologues in human and murine rodents that exhibits a Golgi-predominant localization in nonneuronal cells (Tsuchiya et al., 2001; Engelsberg et al., 2003). This raised the question of what function EBAG9 under physiological conditions has and whether this function relates to its proposed tumor association (Ikeda et al., 2000; Kubokawa et al., 2001; Suzuki et al., 2001; Tsuneizumi et al., 2001; Leelawat et al., 2003; Akahira et al., 2004). Using full-length EBAG9 as the bait to screen a human brain cDNA library, we identified Snapin as an interaction partner of EBAG9 and verified the relevance of this interaction in exocytosis assays. Overexpression of EBAG9 inhibited regulated secretion of neuropeptide Y (NPY) in intact PC12 cells, whereas constitutive secretion of α1-antitrypsin in HepG2 cells remained unaffected. In contrast, EBAG9 overexpression in hippocampal neurons did not alter synaptic transmission. Mechanistically, EBAG9 inhibited Snapin phosphorylation, which subsequently attenuated Snapin binding to SNAP25 and SNAP23. These data demonstrate that EBAG9 is a novel modulator of regulated exocytosis that acts upstream of Snapin and the SNARE complex.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture and Transfections

Human embryonic kidney (HEK)293 and HepG2 cells were cultured in DMEM medium (PAA Laboratories, Cölbe, Germany), supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany), 2 mM l-glutamine, and 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin. PC12 cells were grown with additional 10% horse serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). HEK293 cells were transfected by electroporation by using a Bio-Rad gene pulser. PC12 cells were transfected by using LipofectAMINE 2000 (Invitrogen).

Antibodies

A polyclonal rabbit anti-EBAG9 serum was described previously (Engelsberg et al., 2003). Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against Synaptophysin and VAMP2 were obtained from Synaptic Systems (Göttingen, Germany); mAbs against EEA1, GM130, and p115 were from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA); and anti-FLAG mAbs M2 and M5 were from Sigma Chemie (Deisenhofen, Germany). Biotinylated anti-green fluorescent protein (GFP) antibody was purchased from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA), goat anti-α1-antitrypsin antibody was from U.S. Biochemical (Cleveland, OH), and goat anti-glutathione S-transferase (GST) antibody was from Amersham Biosciences (Freiburg, Germany). A rabbit anti-GFP serum was used for immunoprecipitation (a kind gift of R. Schülein, Forschungsinstitut für Molekulare Pharmakologie, Berlin, Germany), and a rabbit anti-Snapin serum was kindly provided by R. Jahn (Max-Planck-Institut für Biophysikalische Chemie, Göttingen, Germany) (Vites et al., 2004).

Expression Plasmid Constructs

Deletion variants or site-directed mutants of EBAG9 (Engelsberg et al., 2003) and Snapin were constructed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) by using sequence specific primer pairs (see Supplementary Information S1). Full-length Snapin cDNA was isolated in a yeast two-hybrid screen from a human brain cDNA library (kindly provided by H.-J. Schäffer, Max-Delbrück-Center for Molecular Medicine, Berlin, Germany). GST-SNAP23 was generated by PCR by using SNAP23-pcB7 (Koticha et al., 1999) as template. All constructs were verified by cDNA sequencing.

Generation of Recombinant Fusion Proteins, In Vitro Transcription, and Translation

The expression of GST and His6-fusion proteins in Escherichia coli DH5α was done essentially as described previously (Smith and Johnson, 1988). Briefly, fusion protein constructs were cloned into pGEX-4T-1 (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) or pQE-32, respectively (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), followed by induction with 1 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside. Bacterial pellets were sonicated and lysed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)/0.5% Triton X-100 (TX-100). GST or polyhistidine-tagged fusion proteins were purified by binding to glutathione-Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences) beads or nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose (QIAGEN), respectively. Quantification of recovered fusion protein was done by Bradford protein assay and by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining. In vitro transcription and translation were performed in the presence of [35S]methionine/cysteine (Express protein labeling mix; PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Boston, MA), according to the manufacturer's instructions by using Promega Riboprobe kit (Promega, Madison, WI) and the Promega Flexi rabbit reticulocyte system.

Yeast Two-Hybrid Screen

A full-length human EBAG9 cDNA was inserted in-frame into pGBKT7 bait vector (BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) containing the GAL4 DNA-binding domain (BD). Expression was confirmed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. Yeast cells (AH109) were sequentially transformed with pGBKT7-EBAG9 bait vector and a human brain cDNA library in the GAL4 activation domain (AD) containing vector pACT2 (BD Biosciences Clontech) according to the protocols described for the MATCHMAKER GAL4 two-hybrid system 3 (BD Biosciences Clontech). Transformants were selected on plates lacking tryptophan, leucine, histidine, and adenine and supplemented with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-α-d-galactopyranoside (Glycosynth). Prey plasmids from Ade+, His+, Mel1+ clones were rescued and confirmed by retransformation into fresh yeast cells with the pGBKT7-EBAG9 bait or various control baits. β-Galactosidase (lacZ) activity was quantified by liquid culture assay by using standard protocols. The prey plasmids were subjected to DNA sequencing and analyzed by BLAST search.

In Vitro Binding Assays

In vitro-translated 35S-labeled EBAG9 was incubated with 3 μg of the indicated GST fusion protein immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose in NP-40 binding buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 1.5 μg/ml aprotinin). After incubation for 3 h at 4°C, beads were washed extensively in binding buffer, and bound protein was released by boiling in Laemmli reducing sample buffer. An aliquot of the sample was analyzed by 12.5% SDS-PAGE and bound 35S-labeled EBAG9 was visualized by autoradiography. The remaining sample was separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue to control equal load of various GST fusion proteins. Usually, this binding assay was done under saturating conditions.

In a competitive binding assay, 10 μg of immobilized GST-SNAP25 or GST-mSNAP23 was incubated with a constant amount of in vitro-translated 35S-labeled Snapin and increasing amounts of 35S-labeled EBAG9. Beads were washed extensively with 50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, and 0.5% TX-100, and bound protein was analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

For pulldown assays, transiently transfected HEK293 cells were lysed in binding buffer (25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 140 mM KCl, 20 mM NaCl, and 0.5% CHAPS). Three hundred micrograms of cell lysate was incubated with 4.5 μg of the indicated GST fusion protein immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads in binding buffer (0.3% CHAPS). Beads were washed in binding buffer, resuspended in sample buffer, and separated using SDS-PAGE. Bound EBAG9-GFP was visualized with biotinylated anti-GFP antibody. For binding assays with Snapin-GFP, transfected HEK293 cells were lysed in binding buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, and 0.5% TX-100). Cell lysates were incubated with the indicated GST fusion proteins in binding buffer containing 0.1% TX-100. Beads were processed as described above.

Coimmunoprecipitation, Gel Electrophoresis, and Immunoblotting

Cell extracts were prepared from cotransfected HEK293 cells by using TX-100 containing lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, and 0.5% TX-100). Solubilized proteins were incubated with 5 μg of anti-FLAG mAb M5 or rabbit anti-GFP serum and protein A-Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences) in binding buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 0.1% bovine serum albumin, and 0.1% TX-100). Beads were washed three times with binding buffer and bound proteins were separated on a 12.5% SDS-PAGE, followed by transfer to nitrocellulose membranes. Blots were further processed as described above, by using primary antibodies as detailed in the figure legends (Rehm and Ploegh, 1997).

The ratio between total recombinant Snapin-GFP and FLAG-tagged EBAG9 in cell lysates in relation to their amount found in a complex with their respective binding partner was assessed by densitometric scanning of bands obtained from immunoblotting by using identical antibodies. Usually, 1/40 volume of the cell lysate was used to assess total cellular content of the fusion proteins.

Laser Scanning Microscopy

HEK293 cells were cotransfected with Snapin-GFP and pcDNA-EBAG9 and grown on coated coverslips for 36 h, essentially as described previously (Engelsberg et al., 2003). Bound antibodies were detected with a biotinylated secondary antibody (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL) and streptavidin-conjugated Alexa Fluor 568 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Confocal images were acquired with a confocal laser scanning microscope LSM510 (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Fluorescence signals were detected using the following configurations: GFP λexc = 488 nm, BP λem = 500–530 nm, Alexa Fluor 568 λexc = 543 nm, and LP λem = 560 nm). Acquisition was performed using a multi track to prevent bleed-through. All images were processed using LSM Examiner or LSM Browser software.

For confocal microscopic analysis of PC12 cells, cells were grown on collagen-coated coverslips. Where indicated, PC12 cells were stimulated for 3 d with nerve growth factor (β-NGF, 150 ng/ml; Sigma Chemie). Zeiss LSM510 software was used for quantification of fluorescence intensities along representative lines through intracellular regions and through neurite extensions.

Gel Filtration and Subcellular Fractionation

PC12 cells were solubilized in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5% CHAPS, and protease inhibitors), and precleared cell lysate was applied to a Superdex 200 16/60 column (Amersham Biosciences), preequilibrated with elution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, and 0.2% CHAPS) at a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min. Fractions (1.5 ml) were precipitated with trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and analyzed by immunoblotting. For the assessment of void volume (V0), the column was calibrated with blue dextran (2000 kDa) and for the determination of molecular weight the protein standards ferritin (440 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa), ovalbumin (43 kDa), and ribonuclease A (14 kDa) were used.

For subcellular fractionation experiments, PC12 cells were stimulated for 3 d with β-NGF (150 ng/ml), and cell homogenization and fractionation on a discontinuous sucrose gradient was performed exactly as described (Rehm and Ploegh, 1997). Briefly, a postnuclear supernatant was adjusted to 40% (wt/vol) sucrose in a buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, and layered on a 50% sucrose solution. Subsequently, a discontinuous sucrose gradient consisting of 35, 25, 15, and 0% (wt/vol) was poured on top of the 40% sucrose fraction. The gradient was centrifuged for 16 h at 170,000 × g (SW41 rotor). Fractions were harvested (0.75 ml) from the top and analyzed by immunoblotting.

Generation of Adenovirus Vectors and Transduction of Cell Lines

EBAG9 was subcloned in the expression cassette of pQBI-AdCMV5-GFP (Qbiogene, Illkirch, France), followed by homologous recombination with a viral backbone vector in HEK293A cells. Ad-EBAG9-GFP and Ad-GFP were expanded, purified, and titered as described previously (Cichon et al., 1999).

Generation of Semliki Forest Virus

Wild-type EBAG9 was cloned into the Semliki Forest Virus expression vector (based on pSFV1; Invitrogen) containing the respective EBAG9 cDNA sequence fused to enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) (Ashery et al., 1999).

NPY Release Assay

NPY-T7-GST secretion assay in PC12 cells was essentially performed as described previously (Fukuda, 2003). Briefly, PC12 cells (6-cm dish) were cotransfected with pShooter-NPY-T7-GST and EBAG9-GFP, EBAG9-GFP C12/14/27S or GFP (mock). Three days after transfection, cells were stimulated with either high KCl buffer (56 mM KCl, 95 mM NaCl, 2.2 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 5.6 mM glucose, and 15 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) or low KCl buffer (5.6 mM KCl, 145 mM NaCl, 2.2 mM CaCl2, 5.6 mM glucose, 0.5 mM MgCl2, and 15 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) for 10 min at 37°C. Released NPY-T7-GST was recovered by incubation with glutathione-Sepharose beads. After extensively washing with NP-40 lysis buffer (0.5% NP-40, 50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, and 5 mM MgCl2) proteins bound to the beads were analyzed by 12.5% SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with anti-GST antibody. The intensity of the immunoreactive bands on x-ray film was quantified by computer analysis (Tina 2.0; Raytest, Pittsburgh, PA).

Metabolic Labeling and α1-Antitrypsin Secretion

HepG2 cells were infected with Ad-EBAG9-GFP or Ad-GFP at the multiplicity of infection (MOI) indicated in the figure legend. Cells were starved, metabolically labeled with 250 μCi of [35S]methionine/cysteine for 10 min, and chased essentially as described previously (Rehm and Ploegh, 1997). After the chase, cells were washed in PBS and lysed in NP-40 buffer (see above). α1-Antitrypsin was immunoprecipitated from precleared cell lysates and from culture supernatant with anti-α1-antitrypsin antibody immobilized on protein A-Sepharose. Bound protein was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Protein levels were quantified by densitometric scanning.

For palmitoylation, HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with EBAG9-GFP, GFP, or EBAG9-mutants. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were incubated in serum-free medium for 16 h, followed by labeling with [3H]palmitic acid (400 μCi/ml) for 4 h. GFP or GFP-tagged proteins were recovered from NP-40 lysates with anti-GFP serum. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed on SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions. Gels were fixed with 10% methanol/10% acetic acid for 90 min before autoradiography. In some experiments, [3H]palmitate-labeled immunoprecipitates were split, and aliquots were run on separate lanes on SDS-PAGE. After fixation, gels were cut and identical immunoprecipitates were subjected to either 1 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, or 1 M hydroxylamine-HCl, pH 7.4, treatment before autoradiography.

Phosphorylation Experiments

Snapin-GFP was cotransfected with an equal amount of pcDNA-EBAG9 or empty vector (mock). Cells were starved for 1 h in phosphate-free DMEM (MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA), followed by metabolic labeling with 500 μCi of [32P]orthophosphoric acid (MP Biomedicals) for 1 h in phosphate-free DMEM. Cells were then stimulated with 30 ng/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), 40 μM forskolin, or remained unstimulated for 10 min at 37°C. Phosphorylated cells were washed and lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 0.25% deoxycholate, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, and protease inhibitors) for 1 h at 4°C. Snapin was immunoprecipitated with rabbit anti-GFP serum, immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and Snapin was visualized by autoradiography. Snapin phosphorylation levels were quantified and normalized for Snapin protein loads, as assessed by immunoblotting. In vitro phosphorylation experiments were performed essentially as described previously (Chheda et al., 2001), by using 1 U/μl catalytic subunit PKA (Promega) or casein kinase II (CKII) (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences). Phosphorylation levels were quantified by phosphorscreen and normalized to equimolar protein amounts, as determined by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining.

Electrophysiological Analysis of Cultured Hippocampal Neurons

Microisland cultures of mouse hippocampal neurons were prepared from NMRI mice and maintained as described previously (Reim et al., 2001). Neurons were grown in a chemically defined medium (NBA+B27; Invitrogen) and infected with Semliki Forest Virus after 10–14 d in vitro. For each experiment, approximately equal numbers of infected and uninfected control cells from the same preparation were measured in parallel and blindly 8–10 h after infection. Recording conditions (21°C), data acquisition, and analysis were performed as described previously (Rosenmund and Stevens, 1996; Reim et al., 2001).

RESULTS

EBAG9 Recruits the SNARE-associated Protein Snapin

To assess the physiological role of the EBAG9-encoded gene product, we scored for intracellular interaction partners by using a yeast two-hybrid screen. Full-length human EBAG9 was used as a bait for screening of a human brain cDNA library. Approximately 106 independent clones were screened for activation of the reporter genes Ade, His, and Mel1/lacZ, and nine interacting clones were readily obtained. Strongest induction of the β-galactosidase reporter was observed for two clones, both contained full-length cDNAs encoding Snapin (Figure 1A). Specificity of the EBAG9–Snapin association was shown by transformations of control bait and prey plasmids (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Yeast two-hybrid studies of EBAG9 interacting clones. (A) Screening of a human brain cDNA library allowed the identification of nine EBAG9-interacting clones. Clones 7 and 6B showed strongest lacZ reporter activation and encoded full-length Snapin. The positive control is represented by a clone consisting of BD-p53 and AD-SV40 T-antigen. The combination BD-EBAG9 and AD-SV40 T-antigen provided the negative control (0%). β-Galactosidase activity is expressed as percentage of the positive control. Data represent the mean values ± SD of three independent transformants. (B) Specificity of EBAG9–Snapin association. Yeast cells were cotransformed with the indicated GAL4 DNA BD and GAL4 AD plasmids. The unrelated bait BD-Lamin C represented an additional negative control. Colonies were screened for interaction by their ability to grow in the absence of histidine and adenine and by α-galactosidase activity (Mel1). -, no interaction; +++, strong interaction.

To confirm a selective interaction between EBAG9 and Snapin, in vitro binding assays using recombinant fusion proteins were performed. Because GST-EBAG9 is synthesized at extremely low rate in bacteria and is not soluble in aqueous solutions (Engelsberg et al., 2003), EBAG9 was translated in vitro and incubated with GST-Snapin. Whereas 35S-labeled EBAG9 associated with GST-Snapin exclusively, the GST-tagged SNARE proteins SNAP25, VAMP2, and GST alone failed to recover EBAG9 in this in vitro pulldown assay (Figure 2A). In vitro-translated major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I heavy chain HLA-A3 failed to interact with GST-Snapin, which argued against a nonspecific adsorption of Snapin (Supplementary Information S2).

Figure 2.

EBAG9 interacts with Snapin in vitro and in vivo. (A) GST-Snapin, GST-SNAP25, GST-VAMP2, or GST (3 μg each) immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads were incubated with in vitro-translated 35S-labeled EBAG9. Bound proteins were analyzed by 12.5% SDS-PAGE and autoradiography (top). An aliquot was separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue to control equal load of various GST fusion proteins (bottom, Input GST). To score for the amount of in vitro-translated EBAG9 (Input EBAG9), one-quarter of the translation mix was resolved by SDS-PAGE (top). (B) HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with Snapin-GFP, solubilized in TX-100–containing lysis buffer, and cell lysate was then incubated with immobilized GST-fusion proteins, as indicated. Bound proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. Immunodetection of Snapin-GFP (IB) was done with biotinylated anti-GFP antibody (top). After stripping, the same membranes were probed with anti-GST antibody to confirm comparable loading of GST-fusion proteins (bottom). (C) HEK293 cells were transfected with Snapin-GFP, N-FLAG-EBAG9, or both. Cells were lysed in TX-100–containing lysis buffer and immunoprecipitations (IPs) were carried out with anti-FLAG mAb M5. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with biotinylated anti-GFP antibody (top). An aliquot (1/40) of the cell lysate was assessed for the expression of recombinant EBAG9 (middle), by using a polyclonal anti-EBAG9 serum for IB. Bottom, the amount of Snapin-GFP in the starting material was determined using an anti-GFP antibody. (D) Cell lysates of HEK293 cells transfected with EBAG9-C-FLAG, Snapin-GFP or both were processed as shown in C and immunoprecipitated with rabbit anti-GFP serum. Coimmunoprecipitated EBAG9-C-FLAG was detected in IB with anti-FLAG mAb M2 (top). Snapin-GFP was detected with biotinylated anti-GFP antibody (bottom, Input Snapin); the middle panel shows EBAG9-C-FLAG expressed in cell lysates. (E) Size exclusion chromatography. PC12 cells were lysed in CHAPS-containing lysis buffer, followed by separation on a Superdex 200 gel filtration column as described under Materials and Methods. Fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting for EBAG9 and Snapin. The positions of molecular weight standards and Vo are indicated.

EBAG9 Binds to Snapin In Vivo

The interaction between EBAG9 and Snapin was further confirmed by association of in vitro-translated EBAG9 with GST-Snapin and by coimmunoprecipitation assays from transfected HEK293 cells. Although various epitope-tagged Snapin eukaryotic expression plasmids were generated, only a polyclonal anti-GFP antibody was suitable to immunoprecipitate GFP-tagged Snapin. A specific binding of properly folded Snapin to the GST-fusion proteins SNAP25 and SNAP23 was revealed (Figure 2B). The ubiquitously expressed SNAP25 homologue SNAP29 failed to interact with Snapin-GFP.

Coimmunoprecipitation of Snapin-GFP and N-FLAG-EBAG9 in cotransfected HEK293 cells was seen by using the anti-FLAG antibody M5 (Figure 2C). Reciprocal coimmunoprecipitation yielded the same results (Figure 2D). Bound Snapin accounted for 4% of recombinant Snapin expressed in the starting material, as determined by densitometric scanning of bands obtained in total lysate and after coimmunoprecipitation. Conversely, the determination of recombinant FLAG-tagged EBAG9 associated with Snapin yielded an amount of ∼12% related to the total cell lysate. These rates could reflect transient interactions and relate to the number of fully assembled SNARE complexes in neuronal cells, which is in the range of 4–5% (Matveeva et al., 2003).

To further support our observation that EBAG9 and Snapin proteins are associated in vivo, we subjected a PC12 cell extract to size exclusion chromatography on a Sephadex 200 column. The majority of both EBAG9 and Snapin eluted at a molecular weight larger than 440 kDa with a significant cofractionation in fractions 9–15 (Figure 2E). This fractionation profile of Snapin is consistent with a recent publication showing the cofractionation of Snapin with the BLOC-1 in fractions corresponding to 600 kDa (Starcevic and Dell'Angelica, 2004). Only a minor proportion of Snapin (fraction 43) and EBAG9 (fractions 33–35) eluted at positions corresponding to the expected monomers. In addition, we observed the occurrence of Snapin also in fractions 27–29 (molecular weight range 66–98 kDa) where EBAG9 was essentially absent. This points to the potential presence of other association partners; alternatively, multimeric Snapin complexes might occur.

Identification of the Binding Domains Relevant for EBAG9–Snapin Association

To map the binding regions relevant for EBAG9–Snapin Interaction, binding assays of EBAG9-GFP with GST-Snapin or truncated fusion proteins were performed. Analysis of the human Snapin-cDNA sequence applying the Coils program algorithm (Lupas et al., 1991) predicted two helical regions (H1, aa 37–65 and H2, aa 83–126). The C-terminal coiled-coil domain (H2) was characterized as a binding domain for SNAP25 and SNAP23 (Ilardi et al., 1999; Buxton et al., 2003). In contrast, the N-terminal hydrophobic domain (HD; aa 1–20) was suggested to be involved in membrane association of Snapin (Ilardi et al., 1999). Two GST-Snapin deletion mutants, Δ1–20 and Δ83–136, were analyzed for their binding to full-length EBAG9-GFP. The predicted N-terminal α-helix domain (H1) of Snapin was sufficient to confer binding to EBAG9, whereas a deletion of the predicted hydrophobic domain (Δ1–20) or the deletion of the C-terminal coiled-coil domain (Δ83–136) was dispensable for the observed association (Figure 3A). This observation argued against an aspecific interaction due to clustered basic residues in the C terminus of Snapin.

Figure 3.

Mapping of the interaction sites between EBAG9 and Snapin. (A) Snapin associates with EBAG9 via its predicted N-terminal coiled-coil domain. Lysates of EBAG9-GFP–transfected HEK293 cells were incubated with the indicated GST-Snapin deletion mutants or the Snapin S50D mutant. Complexes were washed in CHAPS-containing lysis buffer and bound EBAG9-GFP was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting (IB) by using biotinylated anti-GFP antibody (top). Blots were stripped and reprobed with anti-GST antibody to ensure equivalent loading of GST proteins (bottom). Input EBAG9-GFP, 1/40 volume of the reaction mixture used for each pulldown. On the right, a schematic representation of GST-Snapin and its deletion mutants. The GST tag, the predicted HD and two predicted coiled-coil domains (H1 and H2). (B) EBAG9 binds to Snapin via its predicted TM region. EBAG9 mutants were expressed and analyzed as shown in A. The putative transmembrane domain alone (EBAG9 Δ30–213-GFP) was sufficient to associate with Snapin wt or Snapin aa 21–82, exhibiting the H1 domain. Middle, an aliquot (1/40 volume) of the cell lysates was assessed by IB for the expression of equal amounts of EBAG9-GFP–truncated variants. Bottom, input GST-Snapin fusion protein. On the right, a schematic representation of EBAG9-GFP and its deletion mutants. TM, the predicted transmembrane region (aa 8–27); CC, coiled-coil domain (aa 179–206).

To define the region of EBAG9 involved in binding Snapin, binding analysis of EBAG9-GFP wild-type (wt) and truncated fusion proteins with GST-Snapin were performed. Full-length EBAG9 and all other mutants exhibited similar binding efficiency, whereas the N-terminal truncated variant, EBAG9-GFP Δ1–27, with a deletion of the putative transmembrane (TM) and intraluminal extreme N terminus, was essentially negative. A deletion mutant that exhibited the predicted transmembrane and intraluminal short N terminus only, EBAG9-GFP Δ30–213, was sufficient to confer binding to a GST-Snapin fragment containing the first coiled-coil domain (aa 21–82) (Figure 3B).

These data suggested that the association between EBAG9 and Snapin was mediated by the N-terminal domain of EBAG9 and the N-terminal coiled-coil domain (H1) of Snapin.

Membrane Association and Posttranslational Modifications of EBAG9 and Snapin

Our previous study did not rule out the possibility that the predicted TM-domain (aa 8–27), which contains three cysteine residues, was palmitoylated and thus provides a lipid anchor for a peripheral membrane association of EBAG9 (Engelsberg et al., 2003). To revisit this observation, the subcellular localization of the EBAG9 cysteine mutant C12/14/27S was analyzed. The mutant exhibited a dispersed cytoplasmic staining pattern; in contrast, EBAG9 wt localized to the Golgi region (Figure 4A). Palmitoylation of EBAG9 was assessed in [3H]palmitic acid labeled and transiently transfected HEK293 cells. EBAG9 was immunoprecipitated from detergent lysates, and a specific band for wt EBAG9, but not for the cysteine mutant or the truncated mutant (Δ1–27) lacking the palmitoylation acceptor sites on SDS-PAGE was obtained (Figure 4B). As expected for a thioester linkage, the palmitate label was removed by treatment with neutral hydroxylamine (Figure 4C). The cytoplasmic staining pattern of the mutant implies that the subcellular localization of EBAG9 is dependent on the palmitoylation anchor, which would allow greater accessibility for the interaction with Snapin.

Figure 4.

Palmitoylation contributes to membrane association of EBAG9. (A) HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with wt EBAG9-GFP (right) or with a cysteine deficient mutant (C12/14/17S) (left) and were analyzed by confocal microscopy. Bar, 20 μm. (B) HEK293 cells were transfected with EBAG9-GFP, EBAG9 C12/14/27S-GFP, or EBAG9 Δ1–27-GFP, followed by metabolic labeling with [3H]palmitic acid for 4 h. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-GFP serum (IP) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography (top). An aliquot (1/5) of the immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted (IB) with biotinylated anti-GFP antibody. (C) Aliquots of identical [3H]palmitate-labeled EBAG9-GFP immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and treated separately overnight with 1 M Tris or 1 M hydroxylamine before autoradiography.

To explore membrane association and co- or posttranslational modifications, Snapin was translated in vitro in reticulocyte lysate. The cotranslational addition of microsomes did not result in a size shift in SDS-PAGE (Figure 5A). Therefore, a potential N-glycosylation site (N110) was not used. To probe for a posttranslational membrane association of Snapin, in vitro translation of Snapin was stopped by the inclusion of cycloheximide, and microsomes were added. Microsomal membrane-bound Snapin was analyzed by SDS-PAGE, demonstrating a posttranslational association of Snapin, possibly recruited through protein–protein interactions (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Intracellular distribution of Snapin-GFP. (A) Snapin mRNA was in vitro translated in the presence of [35S]methionine/cysteine with (+) or without microsomes (-). Translation was stopped by addition of sample buffer and boiling. Total loads were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. (B) Snapin associates with microsomal membranes co- or posttranslationally. Microsomes were added to the in vitro translation reaction either at the beginning of translation (-) or after induction of translation arrest by inclusion of cycloheximide (+) (10 μg/ml). Microsomes were pelleted, washed twice with PBS, and analyzed as described in text. (C) HEK293 cells were cotransfected with Snapin-GFP (left, green) and pcDNA-EBAG9. Cells were stained with anti-EBAG9 polyclonal serum (middle). Secondary goat anti-rabbit antibody and streptavidin-conjugated Alexa Fluor 568 were used to detect staining of the primary polyclonal antibody (red). Images were analyzed by confocal microscopy; merged images are shown on the right (yellow). Bar, 10 μm.

Snapin localizes to the cytosol of nonneuronal cells, but it also was found on perinuclear membranes and at the plasma membrane itself (Buxton et al., 2003). When HEK293 cells were cotransfected with Snapin-GFP and pcDNA-EBAG9, Snapin was found in the cytosol (green), but perinuclear staining was obtained as well (Figure 5C). In this region, signals for EBAG9 and Snapin were overlapping (merge, yellow), indicating an association of both molecules at the Golgi complex.

Subcellular Localization of EBAG9 in Neuroendocrine Cells

Snapin is a SNARE-associated protein involved in regulated secretion; therefore, we explored the intracellular distribution of EBAG9 in PC12 cells that are equipped with an abundant regulated exocytosis machinery. In undifferentiated PC12 (-NGF) cells, EBAG9-GFP was predominantly localized to the perinuclear region (Figure 6A). In contrast, in NGF-stimulated PC12 cells (+NGF) EBAG9-GFP revealed an additional punctate staining pattern, with enrichments in the neurite extensions and at the cell periphery.

Figure 6.

NGF-dependent subcellular redistribution of EBAG9 in PC12 cells. (A) PC12 cells were transiently transfected with EBAG9-GFP and cultured in the absence (-) or presence (+)of NGF for 72 h. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and then stained with an anti-Synaptophysin or VAMP2 antibody. Subcellular distribution of EBAG9-GFP (green) and Synaptophysin or VAMP2 (red) (B) was analyzed by confocal microscopy. Merged images are shown on the right. EBAG9-GFP redistributed from perinuclear regions to vesicular structures and to neurite extensions after NGF treatment. A partial colocalization of EBAG9-GFP with the secretory vesicle markers Synaptophysin and VAMP2 in neurites of differentiated PC12 cells was obtained (merge, yellow). Bar, 10 μm. (C) Magnification of overlaid EBAG9-GFP and VAMP2 in neurite extension and intracellular region. The fluorescence intensities measured along a line show amounts of EBAG9-GFP and VAMP2. The fluorescence intensities were plotted as number of pixels (y-axis) relative to their position along the region (x-axis).

Neurite extensions in PC12 cells are enriched for LDCV and synaptic-like vesicles (Chilcote et al., 1995). The identity of EBAG9-positive vesicular structures in NGF-stimulated PC12 cells was explored by double immunofluorescence staining with the secretory vesicle marker molecules Synaptophysin (Figure 6A) and VAMP2 (Figure 6B). Comparison of EBAG9-GFP with Synaptophysin or VAMP2 revealed a significant overlap in neurite extensions of differentiated PC12 cells (+NGF) (merge, yellow), whereas in undifferentiated cells (-NGF) the staining pattern is clearly separate (shown for Synaptophysin). Analysis of fluorescence intensities along a line in two representative areas showed a high degree of overlap, indicating sites with high concentrations of EBAG9 and VAMP2 (Figure 6C).

To score for colocalization with organelle-specific markers in NGF-treated PC12 cells, a subcellular fractionation was performed (Figure 7, A and B). Postnuclear supernatant prepared from PC12 cells was fractionated by equilibrium centrifugation on a discontinuous sucrose gradient. Gradient fractions were analyzed for marker proteins by immunoblotting.

Figure 7.

EBAG9 cofractionates with secretory vesicle markers. (A) Postnuclear supernatant (PNS) of NGF-induced PC12 cells was separated by a discontinuous sucrose density gradient, and fractions were taken from the top. Protein was precipitated with TCA and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting by using the antibodies indicated. Fraction 1, top. (B) Protein marker distribution was quantified by densitometric scanning and expressed as percentage of the total amount present in the PNS.

We observed significant overlap of EBAG9 with the secretory vesicle marker proteins VAMP2 and Synaptophysin in the lower buoyant density region of the gradient, but also a significant cofractionation with the Golgi marker proteins p115 and GM130.

We conclude that EBAG9 is subject to a dynamic redistribution in differentiated neuroendocrine cells, as supported by a flexible lipid membrane anchor (see above).

EBAG9 Inhibits Regulated Exocytosis

Subcellular localization in NGF-stimulated PC12 cells and association with the SNARE-associated molecule Snapin suggested a modulatory role for EBAG9 in regulated exocytosis. By using an established neurosecretion assay in transiently transfected PC12 cells, transient overexpression of EBAG9 resulted in a statistically significant decrease (mean 46%, p = 0.00025) in high K+-induced NPY-GST release (Figure 8A, left), but it had no effect on low K+-dependent secretion (Figure 8A, right). The cysteine-deficient mutant of EBAG9 (EBAG9 C/S, also referred to as C12/14/27S) failed to inhibit NPY secretion, indicating that only a membrane-bound form of the molecule is active in regulated exocytosis. In addition, the coexpression of Snapin was able to rescue the inhibition of evoked norepinephrine release from intact PC12 cells upon EBAG9 overexpression (Supplementary Information S3), suggesting that EBAG9 specifically targets Snapin. This observation indicated that EBAG9 controls regulated LDCV exocytosis.

Figure 8.

Membrane-bound EBAG9 inhibits regulated exocytosis in PC12 cells, whereas constitutive secretion is unaffected. (A) PC12 cells were cotransfected with NPY-GST and EBAG9-GFP, GFP (mock) or EBAG9 C12/14/27S (C/S). NPY-GST secretion was stimulated by a 10-min incubation with high KCl solution (56 mM) or low KCl solution (5.6 mM). Released NPY-GST was captured with glutathione-Sepharose beads, and protein bound was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. Results are expressed as percentage of NPY-GST secretion, compared with total cellular NPY-GST. Bars, means ± SD of three independent experiments. **p = 0.00025, Student's unpaired t test. (B) HepG2 cells were infected with Ad-EBAG9-GFP or Ad-GFP (mock) as a control at MOIs between 5 and 20 for 2 h. After 36 h, cells were labeled with [35S]methionine/cysteine for 10 min, followed by a chase in complete medium. After the indicated periods of chase, α1-antitrypsin was immunoprecipitated and analyzed as detailed in Materials and Methods. α1-Antitrypsin secreted is expressed as percentage of total content. Data are means ± SD of a single representative experiment performed in duplicate. Experiments were performed three times.

Because EBAG9 and its interaction partner Snapin are expressed ubiquitously also in nonneuronal cells, we also addressed the influence of EBAG9 on constitutive exocytosis. When HepG2 cells were infected with adenovirus encoding EBAG9 or with a control virus, no differences in absolute amounts or in the kinetics of α1-antitrypsin secretion were seen (Figure 8B). To further exclude an aspecific effect of EBAG9 overexpression on the secretory pathway, we explored the effects of EBAG9 on the endoplasmic reticulum–Golgi transport of MHC class I molecules and on the trafficking of cathepsin D from the Golgi complex to the lysosomal compartment (Supplementary Information S4 and S5). In conclusion, we observed no difference in maturation kinetics of MHC class I molecules or cathepsin D.

Overexpression of EBAG9 Does Not Alter

Neurotransmitter Release in Hippocampal Neurons

The characteristics of synaptic transmission can be reliably studied in primary cultures. The culture system of choice is the autaptic microdot culture in which individual neurons are plated on small astrocyte feeder islands and generate recurrent or autaptic synapses with themselves. This culture system has been used successfully in the analysis of a number of mouse deletion mutants lacking essential presynaptic proteins, e.g., Synaptotagmin I and Complexin (Geppert et al., 1994; Reim et al., 2001).

Standard patch-clamp recordings from single isolated neurons were used to assess possible defects of presynaptic properties by using a Semliki Forest Virus construct (Ashery et al., 1999) encoding for EBAG9-GFP. Synaptic responses were evoked by brief somatic depolarization (2-ms depolarization from -70 mV holding potential to 0 mV) 8–10 h postinfection and measured as peak inward currents a few milliseconds after action potential induction (Figure 9A). We concentrated our analysis on excitatory glutamatergic neurons, because they are much more abundant than inhibitory GABAergic cells in autaptic cultures. Excitatory postsynaptic current (EPSC) amplitudes recorded from neurons overexpressing EBAG9 were similar to eGFP expressing cells (3.0 ± 0.37 nA for control and 3.40 ± 0.65 nA for EBAG9-overexpressing neurons; p = 0.52)

Figure 9.

Basal parameters of synaptic transmission, synaptic amplitudes, and readily releasable vesicle pools. (A) Bar diagram summarizing average synaptic EPSC amplitudes for EBAG9-GFP (+EBAG9) and eGFP (+eGFP)-overexpressing neurons. Data are presented ± SEM. Values of n indicate total number of cells. (B) Bar diagram showing the average size of the charge induced by application of 500 mM sucrose during 4 s corresponding to the RRP. Data and groups are represented as described above. (C) Average EPSC amplitude normalized to the first response during application of 50 stimuli at 10 Hz. Data and groups are represented as described above.

Sizes of RRP were quantified by measuring the responses of mutant cells and their appropriate controls to application of 500 mM hypertonic sucrose solution for 4 s. Typically, this treatment induces release of the RRP, which in turn leads to a transient inward current followed by a steady current component (Rosenmund and Stevens, 1996) (Figure 9B). The transient part consists of a burst-like release of vesicles resulting from the forced fusion of all fusion competent, primed vesicles. The total number of vesicles in the RRP of a cell can therefore be quantified by integrating the total charge of the transient current component after application of hypertonic solution, divided by the charge of the average miniature EPSC (mEPSC). As shown in Figure 8B, the postsynaptic currents measured during application of hypertonic sucrose were not significantly different between control cells (0.56 ± 0.25 nC) and EBAG9-overexpressing neurons (0.49 ± 0.08 nC; p = 0.36).

When tested at higher stimulation rates, EPSCs from EBAG9-overexpressing cells and control cells showed similar degrees of depression (Figure 9C). We conclude that the effects seen for the EBAG9–Snapin interaction depend on the regulated exocytosis system, as explored in hippocampal neurons or in PC12 cells, respectively.

EBAG9 Inhibits the Basal Phosphorylation of Snapin

Snapin has been suggested to be a substrate for the cAMP-dependent PKA, leading to enhanced association with SNAP25 and increased exocytosis (Chheda et al., 2001).

Based on our mapping of the interaction domain important for EBAG9 binding, which includes the N-terminal region of Snapin (aa 21–82) and the H1 domain (aa 37–65) residing therein, we hypothesized that the phosphorylation of Snapin at residue S50 might be influenced by the association with EBAG9.

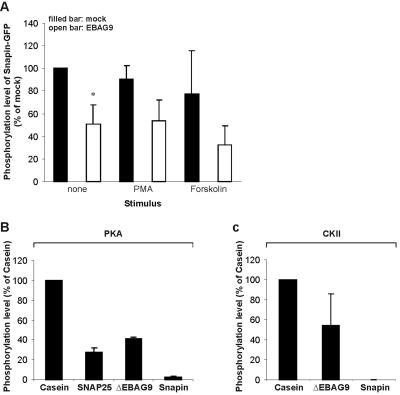

HEK293 cells were cotransfected with Snapin-GFP and EBAG9, followed by metabolic labeling with 32Pi and stimulation with the protein kinase C (PKC) inductor PMA or the PKA inductor forskolin, respectively. Snapin-GFP received a high basal level of phosphorylation in mock (empty vector)-transfected cells, whereas the cotransfection of EBAG9 decreased the basal phosphorylation of Snapin-GFP significantly (mean 50%, p = 0.016). Unexpectedly, PKA stimulation with forskolin failed to increase the basal phosphorylation of Snapin (Figure 10A). In our hands, phosphorylation of recombinantly expressed histidine-tagged Snapin by PKA was even less efficient than those obtained for other substrates, including SNAP25 and Casein (Figure 10B). Analysis of the amino acid sequence of Snapin for potential kinase consensus sites revealed that position S50 can be targeted by PKA, but this site also was identified as a potential target motif for CKII. In an in vitro phosphorylation assay, CKII-dependent phosphorylation of Snapin was not seen. We note that the truncated GST-EBAG9 mutant Δ1–30 was phosphorylated in abundance by recombinant PKA and CKII (Figure 10C).

Figure 10.

EBAG9 inhibits phosphorylation of Snapin. (A) HEK293 cells were transiently cotransfected with Snapin-GFP and pcDNA-EBAG9 or empty vector (mock). Cells were labeled with 32Pi and stimulated with 30 ng/ml PMA, 40 μM forskolin, or remained unstimulated (none) for 10 min at 37°C. Snapin-GFP was immunoprecipitated from a detergent lysate with rabbit anti-GFP serum. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Snapin-GFP phosphorylation was quantified using BAS 2000 image analyzer and expressed as percentage of 32Pi incorporation, compared with unstimulated, mock-transfected cells (100%). Snapin-GFP phosphorylation levels were normalized to protein loads as assessed by immunoblotting (our unpublished data). Note that neither PMA nor forskolin is able to enhance phosphorylation of Snapin-GFP, compared with unstimulated cells. Data represent means ± SD of three independent experiments. *p = 0.0156, Student's unpaired t test. (B) Snapin is an inefficient substrate for recombinant PKA and for CKII (C). Casein and recombinant proteins GST-SNAP25 (SNAP25), GST-EBAG9 Δ1–30 (ΔEBAG9) and His6-Snapin (Snapin) (2 μg each) were tested for their ability to receive phosphorylation by 1 U/μl PKA or 1 U/μl CKII in vitro. Enzymes were preincubated for 10 min at 30°C with 80 μM ATP in 25 μl of kinase buffer. Then, 2 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP was added to the proteins, and reactions were continued for 30 min at 30°C. Reaction products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Phosphorylation levels (Casein, 100%) were quantified by phosphorscreen and normalized to equimolar protein amounts, as determined by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining. Data represent the mean values ± SD of three independent experiments.

In conclusion, in the presence of EBAG9 in vivo phosphorylation of Snapin is strongly reduced.

EBAG9 Inhibits Binding of Snapin to SNAP25 and SNAP23

To explore the functional consequences of Snapin association with EBAG9, a competition study was carried out using immobilized GST-SNAP25 and in vitro-translated Snapin. This system was supplemented with various amounts of in vitro-translated EBAG9. Increasing amounts of in vitro-translated EBAG9 gradually impeded association of Snapin and SNAP25, with a saturation obtained at 25 μl of EBAG9 (Figure 11A). Based on the methionine and cysteine content (Snapin, 3; EBAG9, 7) and relative intensity of both molecules analyzed by densitometric scanning of direct loads (Huppa and Ploegh, 1997), a 1:1 stoichiometry was suggested for both molecules.

Figure 11.

EBAG9 prevents association of Snapin with SNAP25 and SNAP23. (A) A constant amount of immobilized GST-SNAP25 (10 μg) was incubated with a constant amount of in vitro-translated 35S-labeled Snapin. Increasing amounts of 35S-labeled EBAG9, as obtained from in vitro translation, were added. Samples were washed extensively and bound Snapin was detected by autoradiography. The amount of Snapin bound to GST-SNAP25 was quantified and expressed in percentage of Snapin bound to SNAP25 without inclusion of EBAG9 (control, 100%). Mock control, reticulocyte lysate that lacks EBAG9. (B) Likewise, inhibition of Snapin binding to GST-SNAP23 (10 μg) was determined in the presence of EBAG9. Data are representative of four independent experiments in A and B.

In a similar experimental approach, EBAG9 inhibited binding of Snapin to SNAP23 (Figure 11B). The modulatory capacity of EBAG9 in the Snapin–SNAP23 interaction strongly suggests a more general role for EBAG9 in membrane fusion events in nonneuronal cells as well.

DISCUSSION

The results presented here are of interest for several aspects of cell biology. First, the identification of Snapin as an interaction partner of EBAG9 allowed us to assess the physiological function of EBAG9 as a highly conserved and ubiquitously expressed protein in mammalian cells. Second, this characterization might point to a putative link between high level expression of EBAG9 in some tumors, exocytosis, and the occurrence of tumor-associated O-linked glycans (Tsuneizumi et al., 2001; Engelsberg et al., 2003; Akahira et al., 2004). Few examples of plasma membrane glycoproteins and glycolipids were reported where the Ca2+ trigger in regulated exocytosis also was crucial for the levels of plasma membrane receptors and transporters, among them the glucose transporter. Surface deposition is regulated in response to insulin and is mediated by regulated exocytosis (Whitehead et al., 2001). We envisage that EBAG9-mediated modulation of the secretory pathway might favor the deposition of those truncated, normally cryptic glycans at the cell surface. Other examples that link exocytosis and tumor development include the EWS-WT1 gene-fusion product in desmoplasmic small round cell tumors that gives rise to overexpression of the Munc13-1–related molecule BAIAP3. Based on this homology, BAIAP3 was suggested to play a regulatory role in exocytosis (Palmer et al., 2002).

Snapin itself is implicated in synaptic transmission because it binds to SNAP25, mediated through its C-terminal domain (aa 79–136) (Ilardi et al., 1999). Although initially considered as a brain specific, synaptic vesicle localized SNARE complex-associated molecule, it has turned out that Snapin also is expressed in nonneuronal cells. Accordingly, Snapin also can form a ternary complex with the nonneuronal isoform of SNAP25, SNAP23 (Buxton et al., 2003). Because we observed a posttranslational membrane association in microsomal membranes and a predominant cytoplasmic staining pattern together with a punctate staining in the perinuclear region of HEK293 cells, we suggest that Snapin is implicated in vesicle trafficking pathways that are separate from the specialized forms observed at neuronal synapses. In support of this conclusion, inhibition of Snapin binding to the nonneuronal SNAP25 homologue SNAP23 in the presence of EBAG9 suggests a more general role of EBAG9 and Snapin in membrane fusion events in other cell types. In addition, the identification of other Snapin-interacting proteins expanded the role of Snapin to the biogenesis of lysosome-related organelles and to the cycling and subcellular localization of adenylyl cyclase VI through interactions with the SNARE complex, respectively (Chou et al., 2004; Starcevic and Dell'Angelica, 2004).

The association of EBAG9 with Snapin prompted us to explore a potential modulatory role of EBAG9 in regulated exocytosis. The overexpression of membrane-associated EBAG9 in PC12 cells effectuated a significant reduction in neuropeptide Y and catecholamine release. A modulatory impact on regulated exocytosis, but not on constitutive secretion, was suggested by the inability of EBAG9 to alter α1-antitrypsin release from HepG2 cells. These assays supported our notion that the effects of EBAG9 overexpression on regulated secretion were specific but not due to a severe structural or functional disturbance of the secretory pathway.

The phosphomimetic Snapin mutant S50D increased the initial exocytotic burst phase, suggesting that Snapin phosphorylation positively regulates LDCVs (Chheda et al., 2001). In contrast, the sustained component of LDCV exocytosis was increased by both mutants, S50D and an S50A variant, the latter mimics an unphosphorylated state. It was inferred that Snapin might act additionally as a priming factor in the presynaptic vesicle cycle (Chheda et al., 2001). The reduction in release of the surrogate neurotransmitter NPY upon overexpression of the Snapin inhibitor EBAG9 is largely in agreement with the suggested function of Snapin in release from LDCVs. Our failure to observe an inhibitory effect on evoked neurotransmitter release or size of the RRP in hippocampal neurons might relate to the lack of concomitant overexpression of phosphorylated Snapin as downstream effector molecule for EBAG9 (Thakur et al., 2004). Second, several differences between the release machineries in chromaffin cells and neurons have been suggested. Chromaffin cells release catecholamines from LDCVs, whereas hippocampal neurons serve as a model system for release from small clear vesicles. More specifically, differences in pool sizes and kinetic properties have been recorded (Rettig and Neher, 2002). Whereas overexpression of priming factors in chromaffin cells causes large parallel alterations in pool sizes, those changes have not been observed in neurons (Betz et al., 2001).

Because Synaptotagmin I affects exclusively the RRP (Geppert et al., 1994; Voets et al., 2001), the effects of EBAG9 in conjunction with Snapin are unlikely to rest solely on a reduced binding of Synaptotagmin I to the neuronal SNARE complex. Instead, Synaptotagmin III and VII were suggested to play a role during slow/sustained Ca2+ triggered exocytosis in PC12 cells, possibly modulated by Snapin and EBAG9 (Südhof, 2002; Sugita et al., 2002). The effects observed for EBAG9 and Snapin would be in agreement with a promiscuous role of Snapin where binding of other Synaptotagmin isoforms to the SNARE complex is controlled as well. In conclusion, we envisage that EBAG9 modulates priming of Synaptotagmin-associated SNARE complex assembly, as mediated through the linker protein Snapin.

Based on a failure to observe association of Snapin and SNAP25 in biochemical assays and on lack of effects seen for overexpression of a C-terminally truncated variant in neuronal transmission, a recent study suggested a reconsideration of the function of Snapin in neurotransmitter release (Vites et al., 2004). However, in comparison with previous reports (Ilardi et al., 1999; Chheda et al., 2001; Buxton et al., 2003) this novel study did not use the S50D mutant or injection of C-terminal peptides to explore changes in synaptic transmission and is therefore not directly comparable.

Phosphorylation as a regulatory mechanism acts at different stages of the vesicle cycle, but only a few substrates with physiological relevance were identified (Turner et al., 1999; Evans and Morgan, 2003). Our data on the EBAG9–Snapin interaction suggest that inhibition of Snapin phosphorylation might reduce the association of Snapin with SNAP25 and SNAP23, followed by a decrease in Synaptotagmin recruitment. When we revisited the phosphorylation reaction of Snapin, we failed to observe an enhancement by PMA or forskolin, which would be expected if PKA or PKC were involved. However, in contrast to a previous report, we did not use back-phosphorylation or the cAMP-analogue BIMP as an inductor of PKA in vivo (Chheda et al., 2001).

The intracellular redistribution of EBAG9 upon NGF-induced differentiation in PC12 cells showed a population of molecules that colocalized with the secretory vesicle markers synaptophysin and VAMP2 in neurites and in vesicular structures in the vicinity of the plasma membrane. A differentiation-dependent redistribution of vesicle markers also has been reported for Synaptotagmin IV (Fukuda et al., 2003) and hepatocyte growth factor-regulated kinase substrate (Kwong et al., 2000). We suggest that EBAG9 is subject to a dynamic redistribution in differentiated neuroendocrine cells, possibly facilitated by its palmitoylation anchor. Because sorting of proteins also is regulated at the level of protein phosphorylation (Kataoka et al., 2000; Krantz et al., 2000), and EBAG9 was shown to be a substrate for PKA and CKII in vitro, this effect could additionally account for the redistribution of EBAG9 in NGF-stimulated PC12 cells. Other phosphorylated SNARE family members that are essential for distinct steps in the regulation of exocytosis include VAMP, Syntaxin, SNAP25, and SNAP23, but also the SNARE regulatory molecules Rabphilin 3A and Synaptotagmin (Bennett et al., 1993; Fykse et al., 1995; Nielander et al., 1995; Cabaniols et al., 1999; Risinger and Bennett, 1999; Nagy et al., 2004).

In conclusion, the activity of EBAG9 in regulated exocytosis is mediated via its target molecule Snapin. This relationship adds not only an additional layer of control on the exocytotic machinery but also advances our mechanistic understanding of a process that requires a tight fine-tuning. In view of this more physiological role, a potential function of EBAG9 in dysregulation of exocytosis in tumor cells requires further studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs. Reinhard Jahn, Mitsunori Fukuda, Wolfhard Almers, and Zu-Hang Sheng for providing fusion protein constructs and to Dr. Christian Ried for help in gel filtration. We thank D. Reuter and Ina Herfort for expert technical assistance and the animal facilities of the Max-Planck-Institut für Biophysikalische Chemie. We are grateful to E. Neher for stimulating discussions and continuous support and to Sören Panse, Uta E. Höpken, and Kurt Bommert for critical evaluation of the manuscript. This work was supported by a grant from Deutsche Krebshilfe (to A. R.).

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E04-09-0817) on January 5, 2005.

Abbreviations used: EBAG9, estrogen receptor-binding fragment-associated gene9; LDCV, large dense-core vesicle; NPY, neuropeptide Y; PKA, protein kinase A; RRP, readily releasable pool of vesicles; SNAP25, synaptosome-associated protein of 25 kDa; VAMP, vesicle-associated membrane protein.

The online version of this article contains supplemental material at MBC Online (http://www.molbiolcell.org).

References

- Akahira, J.-I., Aoki, M., Suzuki, T., Moriya, T., Niikura, H., Ito, K., Inoue, S., Okamura, K., Sasano, H., and Yaegashi, N. (2004). Expression of EBAG9/RCAS1 is associated with advanced disease in human epithelial ovarian cancer. Br. J. Cancer 90, 2197-2202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashery, U., Betz, A., Xu, T., Brose, N., and Rettig, J. (1999). An efficient method for infection of adrenal chromaffin cells using the Semliki Forest virus gene expression system. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 78, 525-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, M. K., Miller, K. G., and Scheller, R. H. (1993). Casein kinase II phosphorylates the synaptic vesicle protein p65. J. Neurosci. 13, 1701-1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz, A., Thakur, P., Junge, H. J., Ashery, U., Rhee, J.-S., Scheuss, V., Rosenmund, C., Rettig, J., and Brose, N. (2001). Functional interaction of the active zone proteins Munc13-1 and RIM1 in synaptic vesicle priming. Neuron 30, 183-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brose, N., Petrenko, A. G., Südhof, T. C., and Jahn, R. (1992). Synaptotagmin: a calcium sensor on the synaptic vesicle surface. Science 256, 1021-1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, T. L., and Kelly, R. B. (1987). Constitutive and regulated secretion of proteins. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 3, 243-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne, R. D., and Morgan, A. (2003). Secretory granule exocytosis. Physiol. Rev. 83, 581-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton, P., Zhang, X. M., Walsh, B., Sriratana, A., Schenberg, I., Manickam, E., and Rowe, T. (2003). Identification and characterization of Snapin as a ubiquitously expressed SNARE-binding protein that interacts with SNAP23 in non-neuronal cells. Biochem. J. 375, 433-440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabaniols, J. P., Ravichandran, V., and Roche, P. A. (1999). Phosphorylation of SNAP-23 by the novel kinase SNAK regulates t-SNARE complex assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 4033-4041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, E. R. (2002). Synaptotagmin: a Ca(2+) sensor that triggers exocytosis? Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 3, 498-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. A., Scales, S. J., Patel, S. M., Doung, Y. C., and Scheller, R. H. (1999). SNARE complex formation is triggered by Ca2+ and drives membrane fusion. Cell 97, 165-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chheda, M. G., Ashery, U., Thakur, P., Rettig, J., and Sheng, Z. H. (2001). Phosphorylation of Snapin by PKA modulates its interaction with the SNARE complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 331-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilcote, T. J., Galli, T., Mundigl, O., Edelmann, L., McPherson, P. S., Takei, K., and De Camilli, P. (1995). Cellubrevin and synaptobrevins: similar subcellular localization and biochemical properties in PC12 cells. J. Cell Biol. 129, 219-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou, J.-L., Huang, C.-L., Lai, H.-L., Hung, A. C., Chien, C.-L., Kao, Y.-Y., and Chern, Y. (2004). Regulation of type VI adenylyl cyclase by Snapin, a SNAP25-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 46271-46279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cichon, G., et al. (1999). Intravenous administration of recombinant adenoviruses causes thrombocytopenia, anemia and erythroblastosis in rabbits. J. Gene Med. 1, 360-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelsberg, A., Hermosilla, R., Karsten, U., Schülein, R., Dörken, B., and Rehm, A. (2003). The Golgi protein RCAS1 controls cell surface expression of tumor-associated O-linked glycan antigens. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 22998-23007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, G. J., and Morgan, A. (2003). Regulation of the exocytotic machinery by cAMP-dependent protein kinase: implications for presynaptic plasticity. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31, 824-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Chacon, R., and Südhof, T. C. (1999). Genetics of synaptic vesicle function: toward the complete functional anatomy of an organelle. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 61, 753-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda, M. (2003). Slp4-a/granuphilin-a inhibits dense-core vesicle exocytosis through interaction with the GDP-bound form of Rab27A in PC12 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 15390-15396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda, M., Kanno, E., Ogata, Y., Saegusa, C., Kim, T., Loh, Y. P., and Yamamoto, A. (2003). Nerve growth factor-dependent sorting of synaptotagmin IV protein to mature dense-core vesicles that undergo calcium-dependent exocytosis in PC12 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 3220-3226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fykse, E. M., Li, C., and Südhof, T. C. (1995). Phosphorylation of rabphilin-3A by Ca2+/calmodulin- and cAMP-dependent protein kinases in vitro. J. Neurosci. 15, 2385-2395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geppert, M., Goda, Y., Hammer, R. E., Li, C., Rosahl, T. W., Stevens, C. F., and Südhof, T. C. (1994). Synaptotagmin I: a major Ca2+ sensor for transmitter release at a central synapse. Cell 79, 717-727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gieselmann, V., Pohlmann, R., Hasilik, A., and Von-Figura, K. (1983). Biosynthesis and transport of cathepsin D in cultured human fibroblasts. J. Cell Biol. 97, 1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppa, J. B., and Ploegh, H. L. (1997). In vitro translation and assembly of a complete T cell receptor-CD3 complex. J. Exp. Med. 186, 393-403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda, K., Sato, M., Tsutsumi, O., Tsuchiya, F., Tsuneizumi, M., Emi, M., Imoto, I., Inazawa, J., Muramatsu, M., and Inoue, S. (2000). Promoter analysis and chromosomal mapping of human EBAG9 gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 273, 654-660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilardi, J. M., Mochida, S., and Sheng, Z. H. (1999). Snapin: a SNARE-associated protein implicated in synaptic transmission. Nat. Neurosci. 2, 119-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn, R., and Südhof, T. C. (1999). Membrane fusion and exocytosis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68, 863-911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka, M., Kuwahara, R., Iwasaki, S., Shoji-Kasai, Y., and Takahashi, M. (2000). Nerve growth factor-induced phosphorylation of SNAP-25 in PC12 cells: a possible involvement in the regulation of SNAP-25 localization. J. Neurochem. 74, 2058-2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koticha, D. K., Huddleston, S. J., Witkin, J. W., and Baldini, G. (1999). Role of the cysteine-rich domain of the t-SNARE component, SYNDET, in membrane binding and subcellular localization. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 9053-9060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krantz, D. E., Waites, C., Oorschot, V., Liu, Y., Wilson, R. I., Tan, P. K., Klumperman, J., and Edwards, R. H. (2000). A phosphorylation site regulates sorting of the vesicular acetylcholine transporter to dense core vesicles. J. Cell Biol. 149, 379-396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubokawa, M., Nakashima, M., Yao, T., Ito, K. I., Harada, N., Nawata, H., and Watanabe, T. (2001). Aberrant intracellular localization of RCAS1 is associated with tumor progression of gastric cancer. Int. J. Oncology 19, 695-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong, J., Roundabush, F. L., Hutton-Moore, P., Montague, M., Oldham, W., Li, Y., Chin, L. S., and Li, L. (2000). Hrs interacts with SNAP-25 and regulates Ca(2+)-dependent exocytosis. J. Cell Sci. 113, 2273-2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leelawat, K., Watanabe, T., Nakajima, M., Tujinda, S., Suthipintawong, C., and Leardkamolkarn, V. (2003). Upregulation of tumour associated antigen RCAS1 is implicated in high stages of colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Pathol. 56, 764-768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupas, A., Van-Dyke, M., and Stock, J. (1991). Predicting coiled coils from protein sequences. Science 252, 1162-1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matveeva, E. A., Whiteheart, S. W., and Slevin, J. T. (2003). Accumulation of 7S SNARE complexes in hippocampal synaptosomes from chronically kindled rats. J. Neurochem. 84, 621-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, G., Reim, K., Matti, U., Brose, N., Binz, T., Rettig, J., Neher, E., and Sorensen, J. B. (2004). Regulation of releasable vesicle pool sizes by protein kinase A-dependent phosphorylation of SNAP-25. Neuron 41, 417-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielander, H. B., Onofri, F., Valtorta, F., Schiavo, G., Montecucco, C., Greengard, P., and Benfenati, F. (1995). Phosphorylation of VAMP/synaptobrevin in synaptic vesicles by endogenous protein kinases. J. Neurochem. 65, 1712-1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, R. E., Lee, S. B., Wong, J. C., Reynolds, P. A., Zhang, H., Truong, V., Oliner, J. D., Gerald, W. L., and Haber, D. A. (2002). Induction of BAIAP3 by the EWS-WT1 chimeric fusion implicates regulated exocytosis in tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 2, 497-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm, A., and Ploegh, H. L. (1997). Assembly and intracellular targeting of the betagamma subunits of heterotrimeric G proteins. J. Cell Biol. 137, 305-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reim, K., Mansour, M., Varoqueaux, F., McMahon, H. T., Südhof, T. C., Brose, N., and Rosenmund, C. (2001). Complexins regulate a late step in Ca2+-dependent neurotransmitter release. Cell 104, 71-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettig, J., and Neher, E. (2002). Emerging roles of presynaptic proteins in Ca++-triggered exocytosis. Science 298, 781-785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risinger, C., and Bennett, M. K. (1999). Differential phosphorylation of syntaxin and synaptosome-associated protein of 25 kDa (SNAP-25) isoforms. J. Neurochem. 72, 614-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenmund, C., and Stevens, C. F. (1996). Definition of the readily releasable pool of vesicles at hippocampal synapses. Neuron 16, 1197-1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin, O.-H., Maximov, A., Lim, B. K., Rizo, J., and Südhof, T. C. (2004). Unexpected Ca2+-binding properties of synaptotagmin 9. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 2554-2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D. B., and Johnson, K. S. (1988). Single-step purification of polypeptides expressed in Escherichia coli as fusions with glutathione S-transferase. Gene 67, 31-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söllner, T., Whiteheart, S. W., Brunner, M., Erdjument-Bromage, H., Geromanos, S., Tempst, P., and Rothman, J. E. (1993). SNAP receptors implicated in vesicle targeting and fusion. Nature 362, 318-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starcevic, M., and Dell'Angelica, E. C. (2004). Identification of Snapin and three novel proteins (BLOS1, BLOS2, and BLOS3/reduced pigmentation) as subunits of biogenesis of lysosome-related organelles complex-1 (BLOC-1). J. Biol. Chem. 279, 28393-28401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Südhof, T. C. (1995). The synaptic vesicle cycle: a cascade of protein-protein interactions. Nature 375, 645-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Südhof, T. C. (2002). Synaptotagmins: why so many? J. Biol. Chem. 277, 7629-7632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugita, S., Shin, O. H., Han, W., Lao, Y., and Südhof, T. C. (2002). Synaptotagmins form a hierarchy of exocytotic Ca(2+) sensors with distinct Ca(2+) affinities. EMBO J. 21, 270-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, R. B., Fasshauer, D., Jahn, R., and Brunger, A. T. (1998). Crystal structure of a SNARE complex involved in synaptic exocytosis at 2.4 A resolution. Nature 395, 347-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, T., Inoue, S., Kawabata, W., Akahira, J., Moriya, T., Tsuchiya, F., Ogawa, S., Muramatsu, M., and Sasano, H. (2001). EBAG9/RCAS1 in human breast carcinoma: a possible factor in endocrine-immune interactions. Br. J. Cancer 85, 1731-1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, P., Stevens, D. R., Sheng, Z.-H., and Rettig, J. (2004). Effects of PKA-mediated phosphorylation of Snapin on synaptic transmission in cultured hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 24, 6476-6481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya, F., Ikeda, K., Tsutsumi, O., Hiroi, H., Momoeda, M., Taketani, Y., Muramatsu, M., and Inoue, S. (2001). Molecular cloning and characterization of mouse EBAG9, homolog of a human cancer associated surface antigen: expression and regulation by estrogen. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 284, 2-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuneizumi, M., Emi, M., Nagai, H., Harada, H., Sakamoto, G., Kasumi, F., Inoue, S., Kazui, T., and Nakamura, Y. (2001). Overrepresentation of the EBAG9 gene at 8q23 associated with early-stage breast cancers. Clin. Cancer Res. 7, 3526-3532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner, K. M., Burgoyne, R. D., and Morgan, A. (1999). Protein phosphorylation and the regulation of synaptic membrane traffic. Trends Neurosci. 22, 459-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vites, O., Rhee, J.-S., Schwarz, M., Rosenmund, C., and Jahn, R. (2004). Reinvestigation of the role of Snapin in neurotransmitter release. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 26251-26256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voets, T., Moser, T., Lund, P. E., Chow, R. H., Geppert, M., Südhof, T. C., and Neher, E. (2001). Intracellular calcium dependence of large dense-core vesicle exocytosis in the absence of synaptotagmin I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 11680-11685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. T., Grishanin, R., Earles, C. A., Chang, P. Y., Martin, T. F., Chapman, E. R., and Jackson, M. B. (2001). Synaptotagmin modulation of fusion pore kinetics in regulated exocytosis of dense-core vesicles. Science 294, 1111-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber, E., Jilling, T., and Kirk, K. (1996). Distinct functional properties of Rab3A and Rab3B in PC12 neuroendocrine cells. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 6963-6971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, J. P., Molero, J. C., Clark, S., Martin, S., Meneilly, G., and James, D. E. (2001). The role of Ca2+ in insulin-stimulated glucose transport in 3T3–L1 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 27816-27824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.