Abstract

We previously reported that hsa-miR-520d-5p is functionally involved in the induction of the epithelial–mesenchymal transition and stemness-mediated processes in normal cells and cancer cells, respectively. On the basis of the synergistic effect of p53 upregulation and demethylation induced by 520d-5p, the current study investigated the effect of this miRNA on apoptotic induction by ultraviolet B (UVB) light in normal human dermal fibroblast (NHDF) cells. 520d-5p was lentivirally transfected into NHDF cells either before or after a lethal dose of UVB irradiation (302 nm) to assess its preventive or therapeutic effects, respectively. The methylation level, gene expression, production of type I collagen and cell cycle distribution were estimated in UV-irradiated cells. NHDF cells transfected with 520d-5p prior to UVB irradiation had apoptotic characteristics, and the transfection exerted no preventive effects. However, transfection with 520d-5p into NHDF cells after UVB exposure resulted in the induction of reprogramming in damaged fibroblasts, the survival of CD105-positive cells, an extended cell lifespan and prevention of cellular damage or malfunction; these outcomes were similar to the effects observed in 520d-5p-transfected NHDF cells (520d/NHDF). The gene expression of c-Abl (Abelson murine leukemia viral oncogene homolog 1), ATR (ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein), and BRCA1 (breast cancer susceptibility gene I) in transfectants was transcriptionally upregulated in order. These mechanistic findings indicate that ATR-dependent DNA damage repair was activated under this stressor. In conclusion, 520d-5p exerted a therapeutic effect on cells damaged by UVB and restored them to a normal senescent state following functional restoration via survival of CD105-positive cells through c-Abl-ATR-BRCA1 pathway activation, p53 upregulation, and demethylation.

Introduction

The effects of ultraviolet (UV) irradiation on human skin at the molecular and physiological level have been previously examined. UV irradiation induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis by generating reactive oxygen species that can lead to oxidative base damage, such as 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine and thymine glycol in DNA, causing single- or double-strand breaks.1,2 If not repaired in a timely manner, these UV-induced photolesions can cause severe structural distortions in DNA and affect important cellular processes, including DNA replication and transcription.3

miRNAs have been shown to regulate many biological processes such as embryonic development, cell differentiation, apoptosis, proliferation, pluripotency and biogenesis, and they are involved in a wide range of human diseases, including cancer.4,5 miRNAs protect the skin from damage due to brief UV irradiation and regulate miRNA function within miRNA networks.6 Well-known interactions between UV and miRNA function include the following: miR16 is involved in response to DNA damage;7 miR-155 and miR-101 are involved in the response to photoaging;8,9 miR-22, miR-125b and miR-19 are involved in cell survival;10–12 miR-25, miR-145 and miR-434-5p are involved in pigmentation;13–15 and miR-21, miR-17-5p, miR-106a, miR-155 and miR-206 are involved in photocarcinogenesis.16–20 Despite the rapidly growing interest in miRNAs, little is known regarding their precise mechanisms in regulating the response of normal human skin exposed to UV irradiation. Furthermore, the precise damage as a result of either lethal UV irradiation or subsequent gene silencing in normal cells remains unknown except in keratinocytes and murine fibroblasts.7,21,22

We have reported that the human miRNA hsa-miR-520d-5p has the potential to convert undifferentiated or even well-differentiated cancer cells to benign or normal states in vivo via stemness-mediated processes23 and to revert human fibroblasts to mesenchymal stem cells.24 Because 520d-5p extends the lifespan of fibroblasts with this reprogramming mechanism and has never induced tumors in vivo, we presumed that this small molecule has anti-aging or aging-resistant effects against UV damage. In this limited scope, we focused on the gene expression in a small-cell population in response to lethal UVB irradiation and attempted to identify the role of hsa-miR-520d-5p in human fibroblasts, including the potential to salvage the damage caused by UVB. In addition, in this study, we attempted to determine the mechanism of cell survival in response to a lethal insult of UV radiation.

Results

Observation of 520d/NHDF cells (transfectants) after UVB irradiation

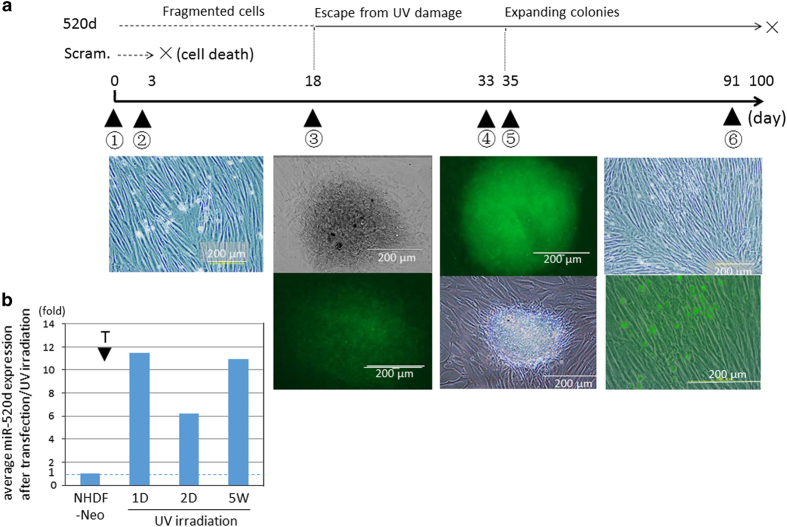

All of the cells (520d/NHDF) lentivirally transfected with 520d-5p before UVB irradiation exhibited cell death without a preventive effect. However, some of the transfectants that received the miRNA after UVB irradiation survived (Figure 1a), showing an increased lifespan, unlike the parental cells (NHDF) or the scramble/NHDF cells. Because stemness induction by 520d-5p after UV irradiation of NHDF cells was reproduced between 2 h and 3 days after each irradiation, 520d-5p expression in NHDF cells transfected after irradiation (irradiation/transfection: a therapeutic trial) was estimated and confirmed on the 1st, 2nd and 35th day after transfection (Figure 1b). We could not quantify expression in the NHDF cells irradiated after transfection (transfection/UVB irradiation: a preventative trial) due to severe cellular damage.

Figure 1.

(a) Overview of protocol and outcomes in this study using normal human dermal fibroblast (NHDF) cells transfected with hsa-miR-520d-5p. ① UV (302 nm) irradiation (17 min by 0.5 J cm−2; 4 min is lethal to NHDF cells). ② Lentiviral transfection by 520d-5p 3 days after UVB irradiation. Both the scramble/NHDF and NHDF cells did not survive, and clonal expansion could not be observed later. ③ Approximately 2 weeks later, we observed the emergence of several spheroid colonies with weak green fluorscent protein (GFP) expression (average 10 colonies per 10 cm2 dish). At this time, we transferred the colonies to six-well plates for further culture. ④ More than a month after transfection, each spheroid colony generated fibroblast-like cells. GFP expression was strongly observed in the spheroid colonies and weakly observed in the fibroblast-like cells. ⑤ After trypsinization for passaging, numerous spheroid cells with strong GFP expression emerged. ⑥ Cells exhibited senescence an average of 75 days after irradiation, after which they died. The left-most column is the phenotype of the NHDF cells before both irradiation and transfection. The second column from the left (>2 weeks) is the phenotype (top) of a surviving colony and its GFP expression (bottom). The second column from the right (more than a month) shows representative spheroid colonies with strong GFP expression (top) and an instance in which fibroblast-like cells were produced from a colony (bottom). The right-most column shows that fibroblast-like cells grew until ~80 days post-transfection (top), with GFP-expressing small round cells scattered between the fibroblast-like cells. Scram., transfection with scramble sequence; 520d, transfection with hsa-miR-520d-5p. (b) Confirmation of hsa-miR-520d-5p expression in NHDF cells. Hsa-miR-520d-5p expression was maintained in NHDF cells received transfection after UV irradiation. Average relative hsa-miR-520d-5p levels in NHDF cells transfected after UVB irradiation are shown, with the parental NHDF cells standardized as 1. T and arrowhead, the transfection by hsa-miR-520d-5p. NHDF cells were used as a control. 520d-5p was not detected the third day after irradiation. Thirty-five days later, transfected cells had 10-fold higher GFP expression compared with the baseline expression in NHDF cells.

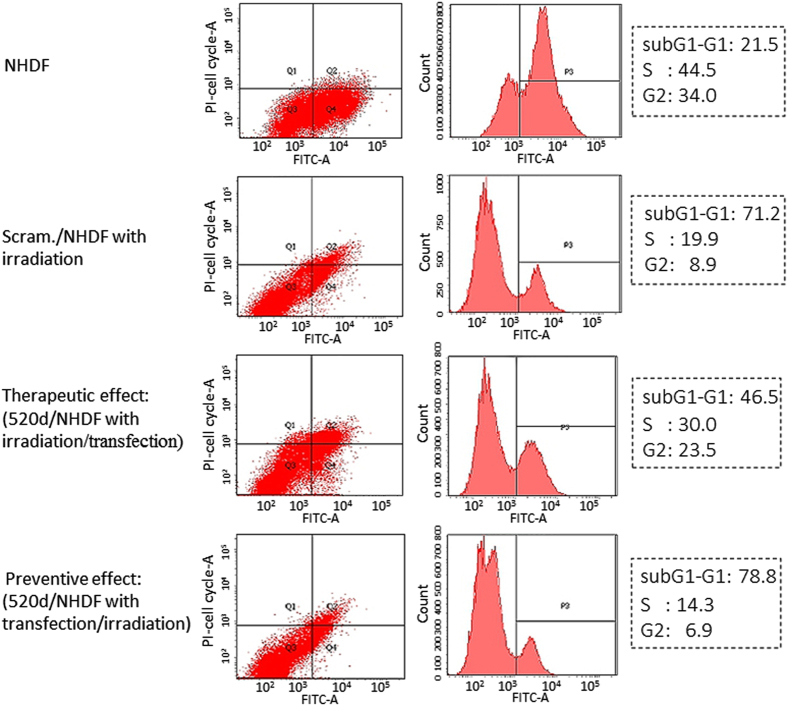

Estimation of transfectant survival using flow cytometry

To evaluate the apoptotic cells after UVB irradiation, we performed flow cytometry on the fourth day after irradiation (the second day after transfection) using annexin-V. Only the 520d/NHDF cells transfected post-irradiation exhibited a reduced apoptotic effect, with 1.5-fold more cells advancing to S phase (Figure 2; third row from top) compared with the scramble/NHDF cells (Figure 2; second row from top) and 520d-5p/NHDF cells transfected pre-irradiation (Figure 2; bottom).

Figure 2.

Flow cytometry reveals that hsa-miR-520d-5p exerts a therapeutic effect. NHDF cells transfected with 520d prior to UVB irradiation could not overcome the severe damage induced by UVB irradiation (bottom), a response similar to that of the scramble/NHDF cells (second row from the top). However, some populations of the NHDF cells transfected with 520d after irradiation were rescued from the lethal stimulation. The top panel shows the DNA content of the NHDF cells. The percentage of cells of each phase of the cell cycle among the four groups is shown and indicated by a dotted square in the right panel.

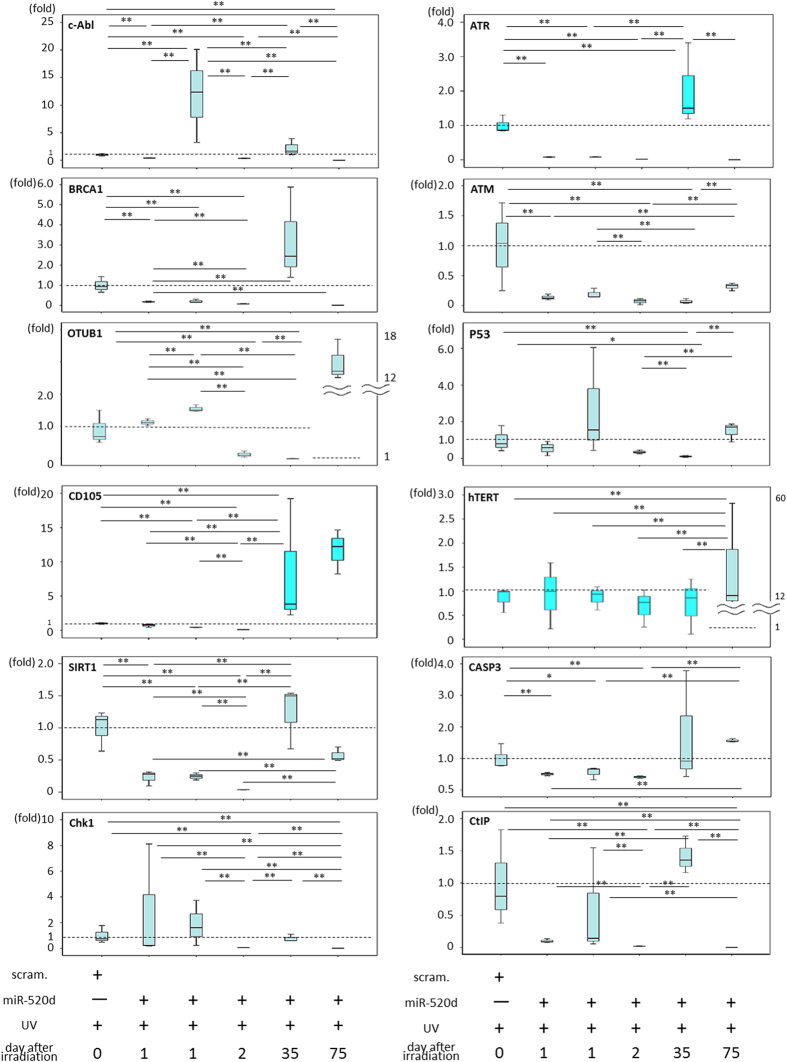

Transcriptional expression analysis in transfectants

Next, we examined gene expression in 520d/NHDF cells as previously reported.24 Although CAS3 was significantly downregulated (P<0.01 by Mann–Whitney U-test; n=4, data not shown), p53 was transiently upregulated, but its expression gradually decreased during the observation period. However, human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) expression was not affected by the transfection. CD105 expression was observed in cells a month after transfection and continued until cell death. Unexpectedly, ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) was significantly downregulated throughout the course after irradiation (P<0.01 by Mann–Whitney U-test; n=4; Figure 3; see Supplementary Figure 1 for the detail statistical analyses).

Figure 3.

The mRNA expression levels of SIRT1, hTERT, CD105, ATM, ATR, BRCA1, Chk1, OTUB1, p53, CASP3, CtIP, Rad50, Rad51, Rad52, c-Abl, and FANCD2 in NHDF cells, scramble/NHDF cells or 520d-5p/NHDF cells. The expression of twelve representative genes is shown. Transfection by 520d-5p after irradiation induced the downregulation of SIRT1, CD105, ATM and CASP3; however, CD105 was upregulated in viable cells a month after transfection. p53 tended to be transiently upregulated but decreased during senescence. hTERT levels were not affected by 520d-5p. OTUB1, Chk1, c-Abl and p53 maintained or upregulated the expression levels initially after transfection by 520d-5p, followed by ATR, BRCA1, CD105, SIRT1 and hTERT upregulation. hTERT, human telomerase reverse transcriptase.

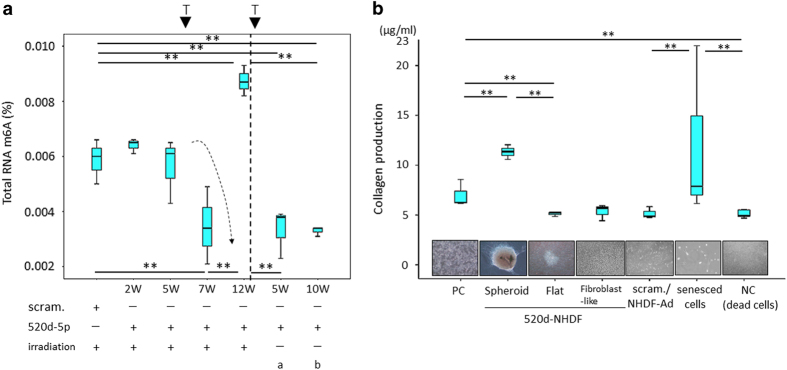

Estimation of RNA methylation level in transfectants

Because RNA levels have been shown to be more reliable to estimate epigenetic changes in a hepatoma cell line (HLF) than DNA levels,24 we examined RNA methylation levels using NHDF cells in this study. The demethylation process was confirmed using total RNA m6A (%) in 520d/NHDF cells and NHDF cells subjected to irradiation/transfection. In the control NHDF cells, demethylation occurred at 5 weeks, and the methylation process was elevated during senescence. UVB irradiation and the subsequent transfection by 520d-5p induced significantly lower levels of RNA methylation (P<0.01 by Mann–Whitney U-test; n=4) similar to those observed in the 520d/NHDF cells (Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

(a) RNA methylation levels in 520d-5p/NHDF cells. The total RNA m6A (%) in the 520d-5p/NHDF cells was measured and estimated compared with that in scramble/NHDF cells. Cells that escaped damage by UVB irradiation were significantly demethylated a month post-transfection. Senescent 520d-5p-transfected NHDF cells exhibited significantly elevated methylation levels. NHDF cells showed similar RNA methylation levels compared with UV-irradiated NHDF cells (therapeutic trial) at seven weeks post-transfection. Scram., scramble/NHDF; 520d-5p, 520d-5p/NHDF; irradiation, UVB irradiation. **P<0.01; T, transfection of hsa-miR-520d-5p; a and b show the RNA methylation levels of NHDF cells without irradiation. a: routine medium, b: medium maintaining undifferentiated status (ReproStem; ReproCELL, Yokohama, Japan). The dotted arrow shows the demethylation process in UV-irradiated NHDF cells after the transfection of 520d-5p. (b) Collagen production in NHDF cells after UVB irradiation (therapeutic trial). The ability to produce collagen in NHDF cells after UVB irradiation was examined. Spheroid cell populations that escaped UVB damage maintained a significantly high level of collagen production. However, flat aggregated cells and the fibroblast-like cell populations observed after the spheroid cells had a reduced ability similar to that in either the scramble/NHDF cells or apoptotic cells (negative control, NC). Senesced cells tended to have upregulated collagen production. PC, NHDF cells; Spheroid, 520d-5p/NHDF (33 W); flat, cells that morphed from spheroid to flat. **P<0.01.

Estimation of functional restoration in transfectants

Collagen production from either control NHDF cells or NHDF cells treated with irradiation/transfection was evaluated. Compared with the NHDF cells, the cells transfected after irradiation had a lower level of collagen production except for the first spheroid populations, which showed significantly higher levels (P<0.01 by Mann–Whitney U-test; n=4). A subset of the senescent population retained higher levels of collagen production (Figure 4b). CD105 expression in the irradiated 520d/NHDF cells was confirmed up to 75 days after transfection (Figure 5a).

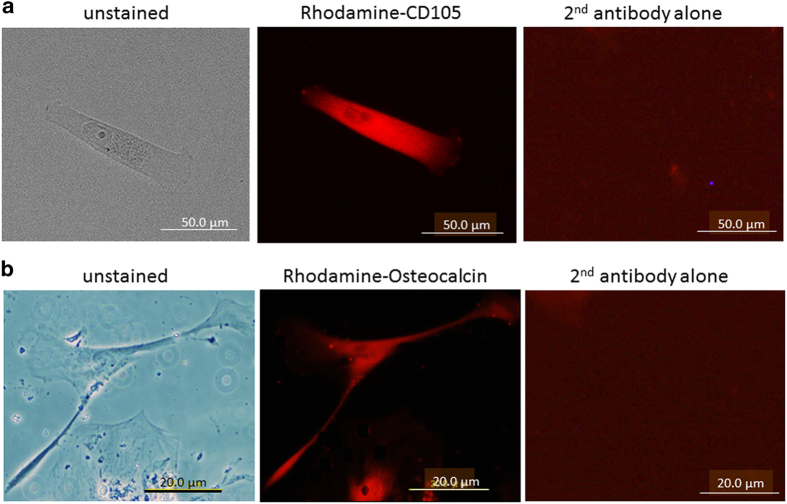

Figure 5.

Gene expression and differentiation induction in senesced cells. (a) CD105 expression in 520d-5p/NHDF cells subjected to irradiation was confirmed 75 days after transfection of 520d-5p using immunocytochemistry (ICC; top). 520d-5p/NHDF cells just prior to apoptosis (77 days post-transfection) underwent differentiation induced by differentiation agents to confirm by ICC whether they had mesenchymal stem cell-like properties. Representative images show that CD105 was expressed during the senesced state although irradiated NHDF expressed CD105 strongly in proliferative status. (b) Osteocalcin was expressed in irradiated NHDF cells after differentiation induction, but the expression of FABP and aggrecan was not observed (bottom). Left, unstained; middle, rhodamine-conjugated antibody; right, second antibody alone.

Estimation of differentiation potency in transfectants

Subsequently, we examined whether adipogenic, osteogenic, or chondrogenic differentiation was induced by differentiating agents in these senesced 520d/NHDF cells treated with irradiation (77 days after transfection). Ninety-one days after transfection (2 weeks after the stimulus for each differentiation), osteocalcin expression was induced, but neither FABP nor aggrecan were expressed (Figure 5b).

Insight into the mechanism of cell survival

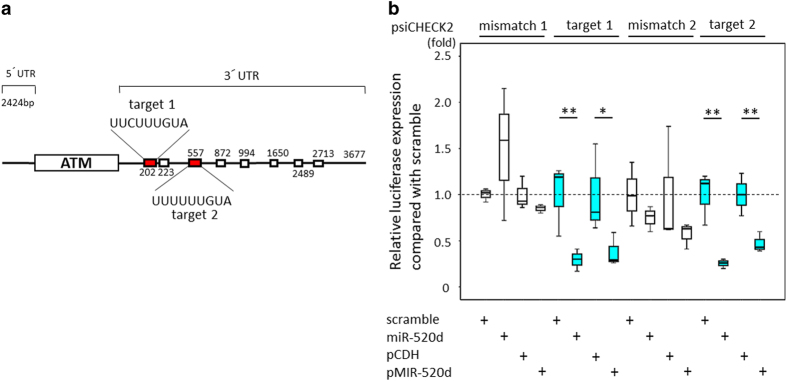

A luciferase reporter assay revealed that one of the candidate targets of hsa-miR-520d-5p is ATM, and three algorithms predict that eight binding sites in the 3ʹ-UTR are targeted sites of 520d-5p (Figure 6a). Two of the eight target sites were confirmed as binding sites using hsa-miR-520d-5p and pMIRNA1/520d-5p (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

(a) A luciferase reporter expression assay was performed to examine whether hsa-miR-520d-5p targets ATM. Out of the more than nine predicted binding sites in the 3ʹ-UTRs of ATM, two core sequences (5ʹ-UUCUUUGUA-3ʹ and 5ʹ-UUUUUUGUA-3ʹ in the 3ʹ-UTR of ATM) were chosen to test for hsa-miR-520d-5p binding. These sites were predicted based on the two databases described above. (b) A luciferase reporter expression assay revealed that hsa-miR-520d-5p bound to the 3ʹ-UTR of ATM, resulting in a reduction of luciferase expression. In contrast, a mismatch of hsa-miR-520d-5p (standardization control) and a scramble group did not significantly bind to the 3ʹ-UTR sites.

Discussion

Although the transcriptional regulation and post-translational modification of proteins in response to UV irradiation has been well studied, the precise role of functional and regulatory molecules (including miRNAs) in the UV stress response of human fibroblasts has not been fully elucidated.25–27 In this report, we analyzed a portion of the interactive network of functional molecules in human fibroblasts after lethal UVB irradiation and focused on hsa-miR-520d-5p, which can convert a cancer cell to either a benign or normal state in vivo via p53 upregulation, and the demethylation process.23

In the current study, NHDF cells without any treatment and scramble-treated NHDF (scramble/NHDF) cells died 3 days after UVB irradiation via apoptosis and not senescence.28,29 However, hsa-miR-520d-5p induced DNA-damaged fibroblasts to survive with reproducibility. The cells (520d/NHDF) that survived exhibited a lifespan that was extended 2.5 times, expressed a mesenchymal cell marker (CD105), and even differentiated towards an osteoblast-like status. The 520d/NHDF cells, in which RNA demethylation was induced, regained its ability to produce collagen.

To cope with the detrimental effects of UV exposure, the cellular machinery is driven by mounting a rapid, inducible, and transient response termed the ‘UV stress response.’ The first genetic response is the DNA damage repair system. After UV-induced damage, the expression of genes involved in DNA repair was silenced universally;30 conversely, many miRNAs were upregulated by UVB (280–320 nm) irradiation.31,32 In this study, OTUB1 (OTU deubiquitinase, ubiquitin aldehyde binding 1) was expressed following UVB irradiation, causing p53 stabilization, which was not downregulated even by lethal UVB irradiation33 (Figure 3). It may be very important in the DNA repair process that ‘ubiquitination and p53 upregulation’ precedes ‘c-Abl-mediated ATR-BCRA1 upregulation’ in the DNA repair process. However, the details regarding these mechanisms remain unclear.

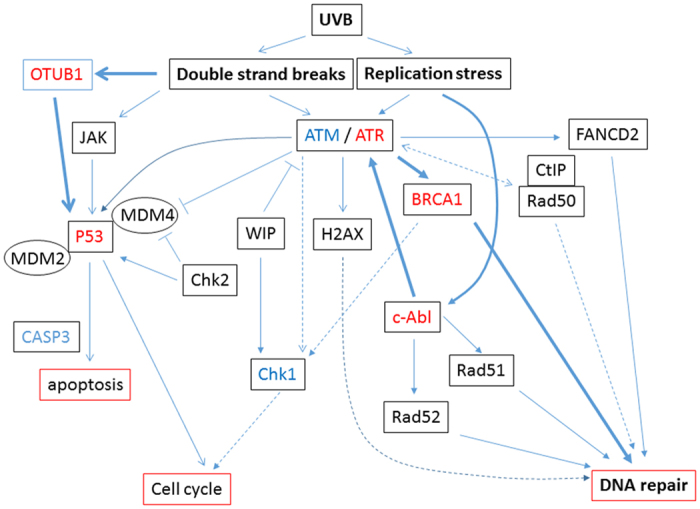

Therefore, we examined transcriptional gene expression changes in irradiated 520d/NHDF cells due to the insufficient quantity of cells to analyze DNA levels (including telomere length) or translational levels. As we previously reported, this miRNA induces the upregulation of p53 and reprogramming via demethylation,23,24 and we presumed that general induction of miRNA upregulation after UV irradiation, especially 520d-5p upregulation, may repair damage even on lethal DNA strand(s) breaks. In transfectants (520d/NHDF), hsa-miR-520d-5p was expressed 5- to 10-fold higher compared with the parental cells (NHDF). In the DNA repair process, initial genetic activation was observed regarding c-Abl and ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related serine/threonine kinase (ATR), which were subsequently upregulated by 520d-5p 35 days after transfection,7,34,35 followed by the activation of BRCA1 (breast cancer 1, early onset).36,37 Six types of DNA damage repair (DDR) mechanisms are known as a modular structure of non-canonical DDRs, and mechanical stress induces ATR activation as an effector.38 Because ATM was continuously suppressed by 520d-5p, alternative ATR activation might drive towards a mechanical stress-based DDR pathway.38 It is thought that these pathways repair damaged DNA in an ATR-dependent manner under these conditions (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

The schematic outline of pathways presumed to be involved in the UV stress response as determined by reverse-transcription PCR (RT-PCR) in this study. The broad arrow indicates the observed pathways functioning in this study. Other pathways did not appear to be implicated in the rescue of irradiated NHDF cells.

The 520d/NHDF cells that survived did so as a result of clonal expansion in the culture dish, and we examined whether they were regarded as normal cells without cancerous properties. These cells exhibited a prolonged but not infinite lifespan; they were positive for CD105 at the cell surface and in the cytoplasm; and they differentiated towards an osteoblastic lineage (Figure 5).24,39 Although the tumorigenicity of 520d/NHDF cells could not be examined due to senescence, we concluded that they escaped from the critical irradiation and senesced as normal cells because they did not exhibit immortalized properties.

UVB-induced DNA damage leads to the accumulation of mutations, predisposing people to carcinogenesis and premature aging. The genetic loss of nucleotide excision repair leads to severe disorders, including xeroderma pigmentosum, trichothiodystrophy and Cockayne syndrome, which are associated with a predisposition to skin cancer at a young age as well as developmental and neurological conditions.40,41 The regulation of nucleotide excision repair is an attractive avenue to either prevent or reverse these detrimental consequences.42 miRNAs may become a key to clarify the novel mechanism underlying the diseases because only a therapeutic effect was observed after inducing hsa-miR-520d-5p expression after DNA damage.

Thus, the results suggest that hsa-miR-520d-5p acts as a UVB protective agent with a therapeutic effect on fibroblasts by driving the ATR-dependent DNA repair system (non-canonical pathway) and maintaining p53 transcriptional stability via deubiquitination (an inhibition of DNA double-strand break (DBS)-induced chromatin ubiquitination), resulting in the reversion of UVB-irradiated cells to a mesenchymal status.43 Applications of this discovery in the anti-aging domain can be expected, including aftercare upon outdoor work or direct exposure to sunlight. This ribonucleic acid may be a highly useful molecule with therapeutic potential against fibroblast-related diseases or damage.

Materials and methods

Cells

To determine the in vitro effects of hsa-miR-520d-5p on UV-irradiated fibroblasts and to explore its protective application for anti-aging therapy, we used three cell lines and a lentiviral vector. NHDF cells were provided by TAKARA BIO (Tokyo, Japan). To examine the effect of hsa-miR-520d-5p on normal cells in vitro, we used NHDF cells cultured in fibroblast basal medium (FBM)-2 using the fibroblast growth medium chemically defined (FGM-CD) Bullet Kit (TAKARA BIO). In addition, the human mesangial cell line 293FT (Invitrogen Japan K.K., Tokyo, Japan) was used to produce the hsa-miR-520d-expressing lentivirus. The 293FT cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (WAKO, Tokyo, Japan) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 0.1 mmol/l minimum essential medium (MEM) non-essential amino acids, 2 mmol/l l-glutamine, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin.

Lentiviral vector constructs

To examine the effects of hsa-miR-520d-5p overexpression on normal cells, we transfected pMIRNA1-miR-520d-5p/green fluorescent protein (GFP; 20 μg; System Biosciences, Mountain View, CA, USA), pMIRNA-scramble/GFP or the mock vector pCDH/lenti/GFP (20 μg) into 293FT cells. To harvest viral particles, the cells were centrifuged at 170,000×g (120 min, 4 °C). The viral pellets were collected, and the viral copy numbers were measured using a Lenti-XTM quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR) titration kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). For NHDF-Ad infection, 1.0×107 copies of the lentivirus were used per 10 cm culture dish. The sequences for hsa-miR-520d-5p and the scrambled sequence were 5′- CUACAAAGGGAAGCCCUUUC-3′ and 5′-GAGUCCGCCTCUATAGACAA-3′, respectively.

Ultraviolet irradiation

Complete NHDF cell death was achieved by UVB treatment (302 nm) for 17 min (0.51 J/cm2) using the UV cross linker CL-1000 (Cosmo Bio, Tokyo, Japan). The irradiated cells were cultured in 10 cm2 dishes, and apoptotic induction and cellular survival until senescence were observed. Cells were irradiated with UVB 5 days after the 520d-5p transfection to investigate the preventive potential; the therapeutic potential was investigated by 520d-5p transfection between 2 h and 2 days after UVB irradiation.

Hsa-miR-520d-5p expression in NHDF cells or transfectants

The miRNA fraction was extracted from cultured cells using the mirVana miRNA Isolation Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). Mature miRNA (hsa-miR-520d-5p: 25 ng/μl) was quantified with the Mir-XTM miRNA qRT-PCR SYBR Green kit (TAKARA BIO) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Fluorescence detection in cells

To estimate the efficacy of infection by the hsa-miR-520d-5p-expressing lentiviral vector, GFP expression was detected with an OLYMPUS IX71 microscope using a TH4-100 power supply (Tokyo, Japan).

Gene expression analysis by RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cultured cells with the mirVana miRNA Isolation Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). The gels were run under the same experimental conditions. The PCR and data collection analyses were performed with a BioFlux LineGene (Toyobo, Nagoya, Japan). To analyze the RT-PCR results, all of the data except those for hTERT were normalized to the β-actin internal control. hTERT expression was estimated by the copy number, and the U6 small nuclear RNA was used as an internal control. The total RNA (25 ng/μl) was reverse transcribed and amplified using the KAPA SYBR FAST One-Step qRT-PCR kit (NIPPON Genetics, Tokyo, Japan). RNA quantification was confirmed by high reproducibility sequencing. The primer sequences used for either mRNA or miRNA quantification are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry

The cells were categorized into four groups. NHDF cells and the scramble-transfectants that received 17 min UVB irradiation were used as controls. To examine the therapeutic effect, hsa-miR-520d-5p was lentivirally transfected into NHDF cells two days after a 17 min exposure to UVB. Four days after UVB irradiation, the DNA content in each mitotic phase was estimated by flow cytometry. To examine the preventive effect, hsa-miR-520d-5p was lentivirally transfected into NHDF cells 5 days prior to the 17 min exposure to UVB irradiation. Two days after UVB irradiation, the cells were examined via flow cytometry. Cell cycle analysis was conducted to confirm the DNA content in the 520d/NHDF cells. After pretreating each cell group with propidium iodide and using the Annexin V-biotin apoptosis detection kit (eBioscience; San Diego, CA, USA), the DNA content was analyzed with a flow cytometer (Epics Altra; Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). Approximately 20,000 cells were assessed 3 days after transfection of one of the pMIRNA1-miR-520d-5p/GFP clones using EXPO32 ADC Analysis software. For cell cycle analysis, a single-cell suspension was washed once with cold PBS. The cell pellet was disrupted by shaking the tube gently and was fixed with 3.7% formalin in ddH2O added dropwise. The cells were then incubated at least overnight at 20 °C. After fixation, the cells were washed twice with cold PBS to remove the ethanol, resuspended at 1×106 cells per ml in PBS containing 100 U/ml RNase A and incubated for 50 min at 37 °C.

Measurement of total RNA N6-methyladenosine (m6A) percentage

N6-methyladenosine levels were measured in NHDF cells, scramble/NHDF cells and 520d/NHDF cells (200 ng of RNA from each) using the EpiQuik m6A RNA Methylation Quantification kit (Colorimetric) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (EPIGENTEK, Farmingdale, NY, USA).

Immunocytochemistry

Because we could not obtain a sufficient number of cells for western blotting, immunohistochemical studies were performed with antibodies to detect a multilineage-differentiating stress enduring (muse) cell marker (anti-CD105) (Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA, USA), markers of differentiation (anti-osteocalcin, anti-aggrecan, or anti-fatty-acid-binding protein (FABP) antibodies) and mesenchymal stem cell markers according to the manufacturer’s instructions (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). NHDF cells were infected with lentiviral particles that contained hsa-miR-520d-5p, and the transfectants were harvested and transferred either to a new culture dish for microscopic examination or onto a slide chamber for immunostaining.

Type I collagen quantification

To examine the ability of fibroblasts or 520d-transfected fibroblasts to produce type I collagen, 200 μl of supernatant was collected from cultures comprising 1×106 cells in 25 cm2 dishes, and the quantity of collagen produced by the 520d/NHDF cells was measured using the Human Collagen Type I ELISA kit (ACEL, Sagamihara, Japan).

Differentiation of 520d-NHDF cells by differentiation-inducing agents

Following treatment with differentiation agents, the induction of osteogenic, chondrogenic and adipogenic differentiation in the 520d/NHDF cells was examined using the Mesenchymal Stem Cell Identification kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Prediction of ATM as target genes of hsa-miR-520d-5p

The potential target genes for hsa-miR-520d-5p (MIMAT0002855: 5ʹ-CUACAAAGGGAAGCCCUUUC-3ʹ) were predicted using three databases (RNA22-HAS: http://cm.jefferson.edu/rna22v1.0, DIANA-microT: http://www.hsls.pitt.edu/obrc/index.php?page=URL1253808676, and microRNA.org: http://www.microrna.org/microrna/home.do). To investigate the binding of hsa-miR-520d-5p to the 3ʹ-UTR of ATM, sequences (or mismatch sequences) that corresponded with predictive hsa-miR-520d-5p binding sites were ligated into the multiple cloning site (MCS) (PmeI and XhoI) of the psiCHECK-2 plasmid (Promega KK, Tokyo, Japan). The signals were detected using the LightSwitch Luciferase Assay Reagent (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Synthesized hsa-miR-520d-5p (KOKEN, Tokyo, Japan) or the control vector pMIRNA1/GFP (System Biosciences, Mountain View, CA, USA) were co-transfected into NHDF cells together with each prepared luciferase expression vector. Synthesized hsa-miR-520d-3p (MBL, Nagoya, Japan) and pLKO.1 (Addgene, Cambridge, MA, USA) with mismatch sequences were used as controls. Forty-eight hours after transfection, luciferin expression (RLU) was measured with an Infinite F500 microplate reader (TECAN, Mannedorf, Switzerland). The RLU (Renilla) was standardized to a control reading (n=3). The following six pairs of sequences were inserted into psiCHECK-2: ATM-3ʹ-UTR sense 1, 5′-TCGAGCAATGTGTGTTCTTTGTATTT-3′; antisense 1, 5′-AAATACAAAGAACACACATTGC-3′; ATM-3ʹ-UTR sense 2, 5′-TCGAATTTTTTTTATTTTTTGTAGTTT-3′; ATM-3ʹ-UTR antisense 2, 5′-AAACTACAAAAAATAAAAAAAA-3′; ATM-3ʹ-UTR mismatch sense 1, 5′-TCGAGCAATGTGTGAACTTTGTATTT-3′; mismatch antisense 1, 5′-AAACTACAAAAAATAAAAAAAA-3′; ATM-3ʹ-UTR mismatch sense 2, 5′-TCGAATTTTTTTTATAATTTGTAGTTT-3′; and mismatch antisense 2, 5′-AAACTACAAAAAATAAAAAAAA-3′.

Statistical analysis

The Mann–Whitney U-test, t-test or one-way analysis of variance were used for comparisons between the control cells, the mock-treated cells and the hsa-miR-520d-5p-transfected cells results with one observed variable. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant (*P<0.05, **P<0.01). In the box plots, the top and bottom of each box represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively, providing the interquartile range. The line through the box indicates the median, and the error bars indicate the 5th and 95th percentiles.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Research for Promoting Technological Seeds B (development type), the Takeda Science Foundation, the Princess Takamatsu Cancer Research Fund (11–24313), the Adaptable and Seamless Technology Transfer Program through Target-driven R&D (Exploratory Research) of the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) and the JSPS KAKENHI Grant (Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Exploratory Research) Number 23659285.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information accompanies the paper on the npj Aging and Mechanisms of Disease website (http://www.nature.com/npjamd)

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ravanat, J. L., Douki, T. & Cadet, J. Direct and indirect effects of UV radiation on DNA and its components. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 63, 88–102 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikehata, H. & Ono, T. The mechanisms of UV mutagenesis. J. Radiat. Res. 52, 115–125 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rastogi, R. P., Richa, Kumar, A., Tyagi, M. B. & Sinha, R. P. Molecular mechanisms of ultraviolet radiation-induced DNA damage and repair. J. Nucleic Acids 2010, 592980 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lee, D. & Shin, C. MicroRNA-target interactions: new insights from genome-wide approaches. Ann. N. Y. Acad Sci. 1271, 118–128 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer, C., Claus, R. & Plass, C. Genome-wide epigenetic regulation of miRNAs in cancer. Cancer Res. 73, 473–477 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly, C. M., Uprety, R., Hemphill, J. & Deiters, A. Spatiotemporal control of microRNA function using light-activated antagomirs. Mol. Biosyst. 8, 2987–2993 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pothof, J. et al. MicroRNA-mediated gene silencing modulates the UV-induced DNA-damage response. EMBO J. 28, 2090–2099 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song, J. et al. MiR-155 negatively regulates c-Jun expression at the post-transcriptional level in human dermal fibroblasts in vitro: implications in UVA irradiation-induced photoaging. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 29, 331–340 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greussing, R. et al. Identification of microRNA-mRNA functional interactions in UVB-induced senescence of human diploid fibroblasts. BMC Genomics 4, 224 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, G., Shi, Y. & Wu, Z. H. MicroRNA-22 promotes cell survival upon UV radiation by repressing PTEN. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 417, 546–551 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, G., Niu, J., Shi, Y., Ouyang, H. & Wu, Z. H. NF-κB-dependent microRNA-125b up-regulation promotes cell survival by targeting p38α upon ultraviolet radiation. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 33036–33047 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olive, V. et al. miR-19 is a key oncogenic component of mir-17-92. Genes Dev. 23, 2839–2849 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z. et al. MicroRNA-25 functions in regulation of pigmentation by targeting the transcription factor MITF in Alpaca (Lama pacos) skin melanocytes. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 38, 200–209 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dynoodt, P. 1 et al. Identification of miR-145 as a key regulator of the pigmentary process. J. Invest. Dermatol. 133, 201–209 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D. T. S., Chen, J. S., Chang, D. C. & Lin, S. L. Mir-434-5p mediates skin whitening and lightening. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 1, 19–35 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu, H. et al. Oxidative stress upregulates PDCD4 expression in patients with gastric cancer via miR-21. Curr. Pharm. Des. 20, 1917–1923 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara, H. et al. Apoptosis induction by antisense oligonucleotides against miR-17-5p and miR-20a in lung cancers overexpressing miR-17-92. Oncogene 26, 6099–6105 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landais, S., Landry, S., Legault, P. & Rassart, E. Oncogenic potential of the miR-106-363 cluster and its implication in human T-cell leukemia. Cancer Res. 67, 5699–5707 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gironella, M. et al. Tumor protein 53-induced nuclear protein 1 expression is repressed by miR-155, and its restoration inhibits pancreatic tumor development. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 16170–16175 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alteri, A. et al. Cyclin D1 is a major target of miR-206 in cell differentiation and transformation. Cell Cycle 12, 3781–3790 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B. R. et al. Characterization of the miRNA profile in UVB-irradiated normal human keratinocytes. Exp. Dermatol. 21, 317–319 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L. et al. Differential expression profiles of microRNAs in NIH3T3 cells in response to UVB irradiation. Photochem. Photobiol. 85, 765–773 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuno, S., Wang, X., Shomori, K., Hasegawa, J. & Miura, N. Hsa-miR-520d induces hepatoma cells to form normal liver tissues via a stemness-mediated process. Sci. Rep. 4, 3852 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Ishihara, Y. et al. Hsa-miR-520d converts fibroblasts into CD105+ populations. Drug R D 14, 253–264 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang, G., Li, G., Wang, Y., Lei, W. & Xiao, Z. Aberrant miRNA expression response to UV irradiation in human liver cancer cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 9, 904–910 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert, K. J., Cook, A. L. & Snow, E. T. SIRT1 inhibition restores apoptotic sensitivity in p53-mutated human keratinocytes. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 277, 288–297 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, G. T. et al. Arctiin induces an UVB protective effect in human dermal fibroblast cells through microRNA expression changes. Int. J. Mol. Med. 33, 640–648 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley, C. B., Vaziri, H., Counter, C. M. & Allsopp, R. C. The telomere hypothesis of cellular aging. Exp. Gerontol. 27, 375–382 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allsopp, R. C. et al. Telomere length predicts replicative capacity of human fibroblasts. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 89, 10114–10118 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed, D. N., Khan, M. I., Shabbir, M. & Mukhtar, H. MicroRNAs in skin response to UV radiation. Curr. Drug Targets 14, 1128–1134 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer, A. et al. UVA and UVB irradiation differentially regulate microRNA expression in human primary keratinocytes. PLoS ONE 8, e83392 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, W. et al. miR-1246 releases RTKN2-dependent resistance to UVB-induced apoptosis in HaCaT cells. Mol. Cell Biochem. 394, 299–306 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.-X. & Dai, M.-S. Deubiquitinating enzyme regulation of the p53 pathway: A lesson from Otub1. World J. Biol. Chem. 5, 75–84 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett, S. G., Wolf Horrell, E. M., Boulanger, M. C. & D'Orazio, J. A. Defining the contribution of MC1R physiological ligands to ATR phosphorylation at Ser435, a predictor of DNA repair in melanocytes. J. Invest. Dermatol. 135, 3086–3095 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foote, K. M., Lau, A. & M Nissink, J. W. Drugging ATR: progress in the development of specific inhibitors for the treatment of cancer. Future Med. Chem. 7, 873–891 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, X. et al. miR-638 mediated regulation of BRCA1 affects DNA repair and sensitivity to UV and cisplatin in triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 16, 435 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonatto, M. et al. DNA damage-activated ABL-MyoD signaling contributes to DNA repair in skeletal myoblasts. Cell Death Differ. 20, 1664–1674 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, R. C. & Misteli, T. Not all DDRs are created equal: non canonical DNA damage responses. Cell 27, 944–947 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiy, F. A. et al. Improvement of in vitro osteogenic potential through differentiation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human exfoliated dental tissue towards mesenchymal-like stem cells. Stem Cells Int. 2015, 249098 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriwaki, S. Hereditary disorders with defective repair of UV-induced DNA damage. Jpn Clin. Med. 4, 29–35 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer, A. et al. Functional and molecular genetic analyses of nine newly identified XPD-deficient patients reveal a novel mutation resulting in TTD as well as in XP/CS complex phenotypes. Exp. Dermatol. 22, 486–489 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah, P. & He, Y. Y. Molecular regulation of UV-induced DNA repair. Photochem. Photobiol. 91, 254–264 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakada, S. et al. Non-canonical inhibition of DNA damage-dependent ubiquitination by OTUB1. Nature 466, 941–946 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.