Abstract

Peanut seeds are rich in arginine, an amino acid that has several positive effects on human health. Establishing the genetic variability of arginine content in peanut will be useful for breeding programs that have high arginine as one of their goals. The objective of this study was to evaluate the variation of arginine content, pods/plant, seeds/pod, seed weight, and yield in Valencia peanut germplasm. One hundred and thirty peanut genotypes were grown under field condition for two years. A randomized complete block design with three replications was used for this study. Arginine content was analyzed in peanut seeds at harvest using spectrophotometry. Yield and yield components were recorded for each genotype. Significant differences in arginine content and yield components were found in the tested Valencia peanut germplasm. Arginine content ranged from 8.68–23.35 μg/g seed. Kremena was the best overall genotype of high arginine content, number of pods/plant, 100 seed weight and pod yield.

Keywords: groundnut, Arachis hypogaea, amino acids, diversity, agronomic traits

Introduction

Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) is a legume crop grown mostly in the tropics and semi-arid tropics. The cultivated peanut is an allotetraploid species with a chromosome number of 2n = 40 (Seijo et al. 2007). Peanut seed is a rich source of protein, fatty acids, vitamins, fiber, and phytochemicals (Win et al. 2011). Arginine, an important amino acid with several health benefits, is found at higher concentrations in peanut seeds than in many other nut crops (Venkatachalam and Sathe 2006). Consumption of arginine at the level of 3–6 g/day has been found to improve the cardiovascular system, reduce intestinal permeability and activate the immune system (Field et al. 2000).

Defining the genetic variability in economically important traits is an important step in breeding programs. Information on the variation in arginine content in peanut germplasm is limited. To the best of our knowledge, only one paper, arginine content in 108 accessions of the core collection of peanut germplasm has been published. In this study, arginine contents in peanut seeds ranged from 15–43 μg/g fresh weight (Dean et al. 2009). Amino acid profiles were studied in 17 peanut genotypes and the arginine content ranged from 8.98–11.2 μg/g (Anderson et al. 1998).

Amino acids in cotyledons of peanut genotypes were higher in Virginia and Valencia types than in other market types, with the arginine content of Valencia types ranging from 11.98–13.01% of total amino acid (Hovis et al. 1982). The range of protein content in peanut gerplasm is also large, as seen in a 152 accession study of peanut genotypes in China, where total proteins ranged from 18.93% to 30.22% (Wang et al. 2011). From previous study, a large population which study about the variation of arginine content was reported only one (Dean et al. 2009). However, this study was not specific to the Valencia type of peanut. So the objective of the present study was to evaluate arginine content and yield components of a large, diverse group of Valencia peanut accessions for the purpose of identifying lines that would be useful in a breeding programs targeting high arginine content and pod yield.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials and experimental design

One hundred and twenty eight accessions from the peanut “core” collection for Valencia, one Spanish (KKU 40) and one Virginia (KKU 60) peanut genotype were used for this study. These accessions were maintained in the genebanks of New Mexico State University, US, the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid-Tropics (ICRISAT) and Khon Kaen University, Thailand. Two varieties (KS 1 and KS 2) from Thailand were also used as Valencia peanut checks. The experiment was conducted at the Field Crop Research Station, Khon Kean University, Thailand during February–June 2012 and repeated during February–June 2013. A randomized completed block design (RCBD) with three replications was used. Plot size was 2 × 5 m and the spacing between row and plant was 50 and 20 cm, respectively.

Crop management

The soil was plowed three times before planting. Sprinkler irrigation system was installed before planting. The seeds of each genotype were treated with Captan (3a, 4, 7, 7 a-tetrahydro-2-((trichloromethyl) thio)-1H-isoindole) at the rate of 5 g/kg seeds for controlling Aspergillus niger. At planting, three seeds per hill were sown and pre-emergent weed control herbicide (Alachor) was applied immediately after sowing. Rhizobium (mixture of strains THA 201 and THA 205; Department of Agriculture, Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, Bangkok, Thailand) was applied in a liquid mixture on the day after planting. Seedlings were thinned to one plant per hill at 14 days after planting (DAP). Fertilizer (0, 56.25, 37.5 kg/ha of N: P2O5: K2O, respectively) was applied 15 DAP. Gypsum (CaSO4) was applied at 312 kg/ha 40 DAP. Fields were scouted weekly for insects, weeds and diseases and treated as needed. Sprinkler irrigation was applied at two-day intervals to maintain soil moisture close to field capacity.

Yield and yield components

At harvest time, total pods of each genotype were harvested from a 2 × 5 m2, and air-dried until reaching 8% moisture content and total pod yield was recorded. Twenty plants were randomly selected and the number of pods per plant, the number of seeds per pod and 100 seed weight of each genotype were recorded.

Arginine content analysis

Seeds from each plot were sub-divided to get 150 g. The 150 g samples of seeds were ground in a blender and a 10 g sub-sample was further ground using a mortar and a pestle. The sub-samples were then extracted using 30 ml of distilled water and filtered through No. 1 Wattman papers. To 5 ml of each sample, 6 M NaCl was added and heated at 90 ± 2°C for 90 minutes for protein precipitation. After heating, the samples were centrifuged for 10 minutes at 5,000 rpm and a 1 ml supernatant was transferred to a microtube and set aside at 4°C until analysis. Free arginine content was then analyzed using the Sakaguchi reaction as follows: to the sub samples, 0.1% α-naphthol (1 ml), 10% KOH (1 ml), 5% urea (1 ml) and 0.4% K-hypobromite (2 ml) were added (Basha et al. 1976), the reactions were incubated at room temperature for 20 min and then measured for absorbance at 520 nm using a spectrophotometer.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed as a randomized complete block design using Statistix 8 (Statistix8 2003). The correlations between arginine content and yield and yield components were also analyzed using Statistix 8. A data matrix of the 130 accessions was constructed using the mean of yield and yield component characters and arginine content. The cluster analysis based on Ward’s method and squared Euclidian distance was performed and the dendrogram was constructed. All calculations were performed in SAS 6.12 software (SAS 2001).

Results

Combined analysis of variance

The year was significantly different (P ≤ 0.05) for number of pods per plant and pod yield, whereas genotypes were significantly different for all traits (Table 1). The interactions between year and genotype were significant for most traits except for number of pods per plant.

Table 1.

Mean squares from combined analysis of arginine content (Arg; μg/g), number of pods per plant (P/plant), number of seeds per pod (S/pod), 100 seed weight (100 SW; g) and pod yield (g/plant) of 130 peanut accessions across two years (2012 and 2013)

| Source | df | Arg | P/plant | S/pod | 100 SW | Pod yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year (Y) | 1 | 0.2 ns | 36550.2** | 0.9 ns | 17782.8 ns | 42763.9** |

| Y*REP | 4 | 32.3 | 216.0 | 0.1 | 53 | 101.1 |

| Genotype (G) | 129 | 50.4** | 114.9** | 0.6** | 140.2** | 51.2** |

| Y*G | 129 | 25.1** | 43.6ns | 0.1** | 28.9** | 37.3** |

| Error | 516 | 3.8 | 36.1 | 0.1 | 17.0 | 20.8 |

| Total | 779 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| CV (%) | 12.0 | 25.8 | 12.7 | 10.4 | 25.1 | |

ns = not significant;

P ≤ 0.05,

P ≤ 0.01.

Arginine, yield and yield components

The peanut genotypes with highest and lowest arginine content and agronomic traits are shown in Table 2. Arginine contents ranged from 9.35–25.90 μg/g seed in 2012 and 7.44–25.02 μg/g seed in 2013. The top five accessions for arginine content in 2012 were New BG, S3881, S3653, Kremena and PI 536307 with arginine contents being 25.90, 25.69, 23.10, 22.68 and 22.47 μg/g, respectively, whereas the five highest accessions in 2013 were DC 2120 (S3873), Kremena, ICG 5475, PI 493405 and PI 493630 with arginine contents being 25.02, 24.02, 23.17, 22.86 and 22.60 μg/g, respectively.

Table 2.

Means for arginine content (Arg; μg/g seed), number of pods per plant (P/plant), number of seeds per pod (S/pod), 100 seed weight (100 SW; g) and pod yield (g/plant) of the ten highest and lowest genotypes based on arginine content in 2012 and 2013. Values with different letters within the same column in each group (high and low arginine groups) are significantly different at P ≤ 0.05 by DMRT

| Entry | Accession | 2012 | Entry | Accession | 2013 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

| Arg | Pods/plant | Seeds/pod | 100 SW | Yield | Arg | Pods/plant | Seeds/pod | 100 SW | Yield | ||||

| Ten highest varities for arginine content | |||||||||||||

| 82 | New BG | 25.90 | 33.41 B | 2.18 BC | 45.30 CD | 24.78 | 78 | DC2120 (S3873) | 25.02 | 13.66 AB | 2.35 ABC | 38.60 BC | 14.10 AB |

| 83 | S 3881 | 25.69 | 25.80 BC | 2.06 C | 53.08 BC | 19.13 | 85 | Kremena | 24.02 | 17.20 AB | 1.90 C | 47.36A | 15.43 A |

| 80 | S-3653 | 23.10 | 27.80 BC | 2.56 AB | 45.53 CD | 25.31 | 103 | ICG 5475 | 23.17 | 20.26 AB | 2.11 BC | 32.05 C | 7.24 CD |

| 85 | Kremena | 22.68 | 45.46 A | 1.98 C | 57.05 ABC | 28.95 | 52 | PI493405 | 22.86 | 14.80 AB | 2.33 ABC | 32.95 C | 6.97 CD |

| 18 | PI536307 | 22.47 | 23.40 BC | 2.95 A | 52.58 BC | 24.62 | 69 | PI493630 | 22.60 | 12.86 B | 2.15 BC | 33.87 C | 8.84 BCD |

| 9 | PI493381 | 22.46 | 25.93BC | 2.93 A | 47.28 CD | 25.63 | 3 | PI475921 | 22.35 | 12.86 B | 1.95 C | 36.86 BC | 5.00 D |

| 105 | ICG 6022 | 22.28 | 19.26 C | 3.00 A | 63.66 AB | 29.96 | 105 | ICG 6022 | 22.24 | 11.13 B | 2.73 A | 44.60 AB | 11.94 ABC |

| 63 | PI493565 | 22.07 | 28.26 BC | 2.80 A | 35.81 D | 20.26 | 45 | PI493325 | 22.07 | 22.86 A | 2.45 ABC | 35.36 C | 8.87 BCD |

| 129 | KKU 60 | 21.84 | 31.26 B | 1.80 C | 65.81 A | 33.76 | 44 | PI468208 | 21.78 | 23.06 A | 2.10 BC | 38.26 BC | 15.10 AB |

| 53 | PI493415 | 21.71 | 26.06 BC | 2.63 AB | 54.99 AB | 22.18 | 4 | PI475925 | 21.65 | 12.86 B | 2.55 AB | 34.71 C | 10.41 ABCD |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Ten lowest varieties for arginine content | |||||||||||||

| 47 | PI493340 | 10.70 | 27.53 | 2.60 B | 41.83 A | 27.33 | 106 | ICG 6201 | 10.93 | 13.80 | 2.85 A | 34.61 AB | 7.50 |

| 41 | PI576604 | 10.61 | 22.20 | 1.80 C | 44.03 A | 27.86 | 35 | PI493518 | 10.66 | 15.46 | 2.70 AB | 32.37 AB | 10.84 |

| 2 | PI475913 | 10.26 | 40.93 | 3.20 A | 32.48 B | 25.57 | 109 | ICG 7181 | 10.59 | 12.13 | 2.70 AB | 38.69 A | 9.31 |

| 106 | ICG 6201 | 10.23 | 23.73 | 2.60 B | 43.37 A | 25.62 | 114 | ICG 10474 | 10.48 | 16.20 | 2.83 A | 39.08 A | 10.73 |

| 119 | ICG 13856 | 10.14 | 34.00 | 2.40 B | 41.62 A | 27.34 | 72 | PI493688 | 10.45 | 17.86 | 2.41 AB | 28.64 B | 7.38 |

| 98 | ICG 2738 | 10.01 | 34.86 | 2.50 B | 40.01 A | 26.04 | 57 | PI493458 | 10.23 | 11.40 | 2.83 A | 28.54 B | 6.86 |

| 60 | PI493484 | 9.91 | 28.66 | 2.50 B | 42.53 A | 26.03 | 62 | PI493523 | 10.02 | 16.20 | 2.56 AB | 29.65 B | 8.88 |

| 76 | PI494019 | 9.87 | 31.93 | 2.50 B | 45.89 A | 27.72 | 73 | PI493810 | 9.64 | 17.60 | 2.16 B | 30.54B | 11.74 |

| 26 | PI338337 | 9.85 | 34.33 | 2.70 B | 44.71 A | 24.63 | 55 | PI493446 | 8.51 | 18.33 | 2.45 AB | 38.91 A | 11.60 |

| 55 | PI493446 | 9.35 | 30.46 | 2.20 BC | 43.35 A | 24.81 | 60 | PI493484 | 7.44 | 17.60 | 2.90 A | 34.07 AB | 11.99 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Min | 9.35 | 15 | 1.78 | 32.48 | 11.71 | 7.44 | 6.40 | 1.20 | 24.47 | 5.00 | |||

| Max | 25.90 | 51.13 | 3.23 | 65.80 | 37.74 | 25.02 | 30.26 | 3.45 | 52.16 | 19.26 | |||

| Mean | 16.13 | 30.17 | 2.51 | 44.51 | 25.57 | 16.10 | 16.15 | 2.58 | 34.96 | 10.77 | |||

Numbers of pods per plant ranged from 15.0–51.13 pods/plant in 2012 and 6.4–30.26 in 2013, whereas the numbers of seeds per pod ranged from 1.78–3.23 to 1.20–3.45 seeds/pod in 2012 and 2013, respectively. One hundred seed weight ranged from 32.48–65.80 g in the first year and 24.47–52.16 g in the second year and pod yield (g/plant) ranged from 11.71–37.74 and 5.00–19.26 in the first and second year, respectively.

Correlation between arginine content and agronomic traits

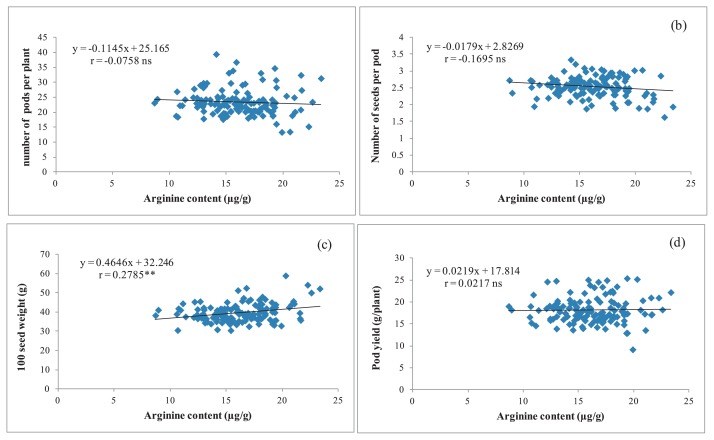

In this study, the arginine content was not correlated with any trait except 100 seed weight; however the correlation coefficient was low (r = 0.2758) (Fig. 1). This indicated that a breeding program to develop a peanut line with a high arginine content and high pod yield is possible because the arginine content did not depend on the yield.

Fig. 1.

Relationship between arginine content and number of pods per plant (a), number of seeds per pod (b), 100 seeds weight (c) and pod yield (g/plant) (d) of 130 peanut accessions across two years. ns,** = not significant and significant at ** P ≤ 0.01, respectively

Cluster analysis

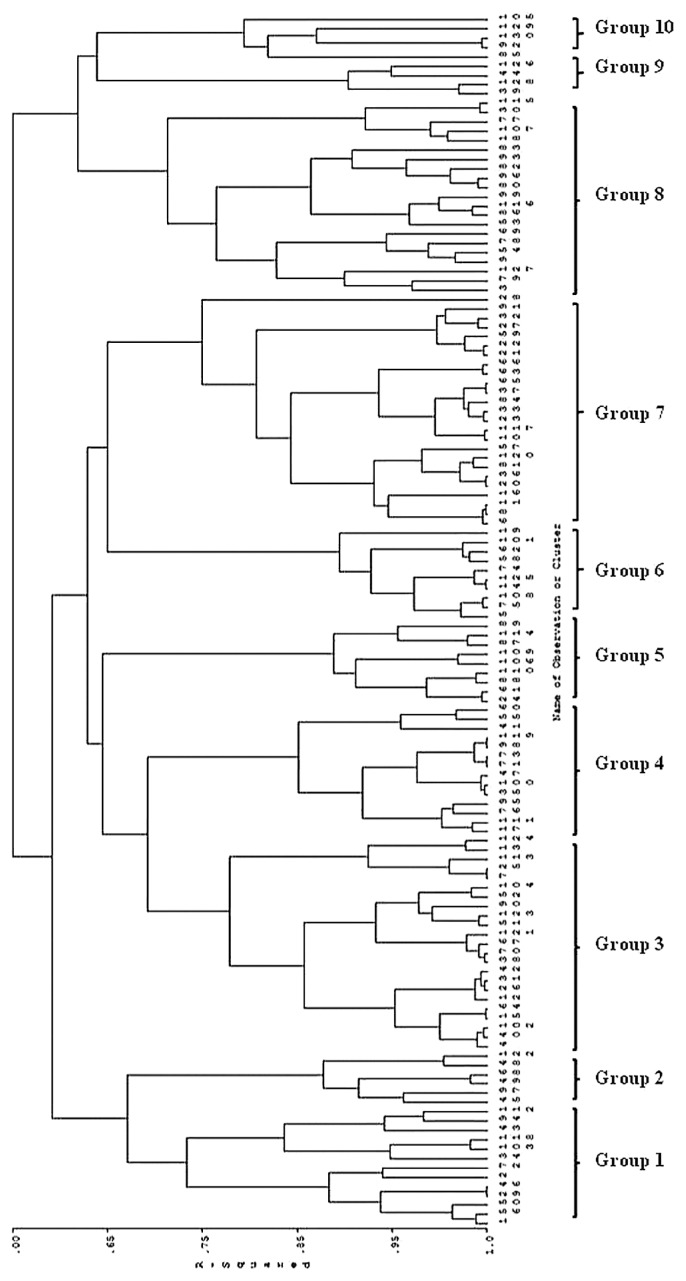

One hundred and thirty peanut accessions were grouped into 10 clusters (R2 = 0.70) (Fig. 2) based on arginine content, number of pods per plant, number of seeds per pod, 100-seed weight and pod yield. The clusters should aid plant breeders in the development of new peanut lines with multiple desirable, yet unrelated, traits such as arginine content and yield.

Fig. 2.

Dendrogram from cluster analysis of 130 peanut genotypes based on arginine content, number of pods per plant, number of seeds per pod, 100 seed weight and pod yield across two years.

Cluster one included 13 accessions originating from Bolivia, Argentina, Costa Rica, Kenya, Zimbabwe and USA. This cluster represented moderate arginine content (15.66 μg/g), high number of pods per plant (29 pods/plant), moderate number of seeds per pod (2.52 seeds/pod), low 100 seed weight (35.86 g) and moderate pod yield (18.95 g/plant). Cluster two consisted of 6 accessions originating from Argentina and Zaire and this cluster represented moderate arginine content (15.66 μg/g), high number of pods per plant (35 pods/plant), low number of seeds per pod (2.17 seeds/pod), low 100 seed weight (34.83 g) and moderate for pod yield (17.74 g/plant). Cluster three consisted of 23 accessions originating from Bolivia, Peru, Argentina, Venezuela, Zimbabwe, New Mexico State, Brazil, Zaire, Cameroon, Srilanka, Africa and one unknown accession. This cluster represented moderate arginine content, moderate number of pods per plant, moderate 100 seed weight and moderate pod yield, and high number of seeds per pod. Cluster four consisted of 14 accessions originating from Uruguay, Bolivia, Argentina, Benin, USA, Uganda and India. This cluster was characterized by low arginine content (12.51 μg/g), high number of pods per plant, high number of seeds per pod, high 100 seed weight and moderate pod yield.

Cluster five consisted of 9 accessions originating from the Russian Federation, Argentina, New Mexico State, Peru, Cuba and India. This cluster represented low arginine content (12.78 μg/g), number of pods per plant and pod yield, whereas the number of seeds per pod and 100 seed weight were high. Cluster six consisted of 10 accessions originating from Brazil, Argentina, Bolivia and Sudan. This cluster represented moderate arginine content (15.04 μg/g), moderate number of pods per plant (23.27 pods/plant), high number of seeds per pod (2.66 seeds/pod), low 100 seed weight (34.28 g) and low pod yield (16.38 g/plant). Cluster seven consisted of 25 accessions originating from Brazil, Argentina, Peru, Uruguay, Uganda, Israel, New Mexico State, USA, Jamaica, Australia, Zimbabwe, India and Ecuador. This cluster represented moderate arginine content, low number of pods per plant, high number of seeds per pod, moderate 100 seed weight and low pod yield.

Cluster eight consisted of 21 accessions originating from Bolivia, New Mexico State, Thailand, Argentina, Congo, Korea, Indonesia, Brazil, Uruguay, Ecuador and unknown. This cluster represented high arginine content (18.58 μg/g), low number of pods per plant, moderate number of seeds per pod, high 100 seed weight (43.97 g) and moderate pod yield. Cluster nine consisted of four accessions originating from Ecuador, Bolivia and Thailand. This cluster represented moderate arginine content (15.24 μg/g), high number of pods per plant (28.97 pods/plant), low number of seeds per pod (2.28 seeds/pod), high 100 seed weight (43.99 g) and moderate for pod yield (24.52 g/plant). Cluster ten consisted of five accessions originating from New Mexico State, Mauritius, India and Thailand. This cluster represented high arginine content (19.75 μg/g), 100 seed weight (53.83 g), and pod yield (23.34 g/plant), whereas the number of pods per plant was moderate (23.67 pods/plant) and the number of seeds per pod was low (2.19 seeds/pod).

Discussion

In a peanut breeding program for high arginine, the diversity of the germplasm for arginine is important for improving this trait. In this study, arginine contents ranging from 8.68 μg/g (PI 493484) to 23.35 μg/g (Kremena) were observed in the Valencia peanut germplasm, core collection. In a previous study, arginine content in 17 peanut cultivars and breeding lines ranged from 8.98–11.20 μg/g (Andersen 1998). In another investigation, the range of arginine contents was between 15 μg/g and 43 μg/g (Dean et al. 2009). Arginine diversity in this study was consistent with those in previous studies. The larger number of peanut accessions in this study provides plant breeders with additional peanut germplasm information useful to breeding programs trying to advance multiple traits, such as arginine content and yield.

Arginine concentrations in other nut seeds such as almond, Brazil nut, cashew nut, hazelnut, macadamia nut, pecan, pine nut, pistachio, walnut and peanut (Virginia type) have been reported to average 10.09, 12.91, 9.84, 12.51, 12.53, 12.45, 15.41, 9.15, 13.80 and 11.04 g/100 g of protein, respectively (Venkatachalam and Sathe 2006). Moreover, Phaseolus, which is a legumes food, arginine content in wild type was 5.86, and in cultivated types including Potato, Siena and big Lima were 6.62, 6.38 and 6.13% of total amino acids (Baudoin and Maquet 1999).

From the results, the arginine content differed among years and changed with the order of varieties. Thus, the arginine content may be a quantitative trait that is controlled by several genes (Slocum 2005). However, some varieties, such as Kremena and ICG 6022, still have high arginine contents in both years and they had high potential for use as parental lines in high arginine content breeding programs.

In this study, arginine content in Valencia peanut was not correlated with the number of pods per plant, number of seeds per pod, 100 seed weight and pod yield. The results indicated that arginine and yield traits segregate independently. Therefore, breeding for both high arginine and high yield should be successful.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the diversity of arginine content and identify lines for use in breeding programs that would aid the development of cultivars superior in yield and arginine by grouping the peanut accessions into 10 clusters based on arginine content, number of pods per plant, number of seeds per pod, 100 seed weight and pod yield. Breeders should be able to study the heritability of these traits and develop superior cultivars for them. For example, cluster five accessions were characterized as having low arginine content (12.78 μg/g) and pod yield. Cluster ten accessions were characterized as having high arginine content (19.75 μg/g) and pod yield. Cluster ten included Kremena, ICG 297, KKU 40, KKU 60 and ICG 6022. Kremana and ICG 6022 should be particularly interesting for breeding programs because they have high arginine content (23.35 and 22.26 μg/g), large seeds (52.2 and 54.13 g/100 seed) and high yield (22.19 and 20.95 g/plant). The origins of peanut plants in each cluster were different. For example, cluster ten with a high arginine content in the seed originated from New Mexico State, Mauritius, India and Thailand. Cluster four and five with low arginine contents also differed in origin. The result indicated that high or low arginine content in peanut seed was not related to their origin.

In conclusion, significant variation of arginine content was found within the Valencia germplasm core collection. Peanut genotypes Kremena and ICG 6022 had high arginine content, pod yield and a good agronomic trait. These two genotypes would be promising parents in breeding programs targeting improved arginine content and yield.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the jointed financial support of the Royal Golden Jubilee Ph.D. program and Khon Kaen University, the peanut and Jerusalem Artichoke Improvement for Functional Food Research Group, Khon Kaen University, The Higher Education Promotion and National Research University Project of Thailand of the Office of Higher Education Commission were also acknowledged for funding support through the Food and Functional Food Research Cluster of Khon Kaen University, Plant Breeding Research Center for Sustainable Agriculture, The Thailand Research Fund for providing financial supports to this research through the Senior Research Scholar Project of Professor Dr. Sanun Jogloy (Project no. RTA 5880003). Acknowledgment is extended to the Thailand Research Fund (TRF, Project no. IRG 5780003), Khon Kaen University (KKU) and the Faculty of Agriculture KKU for providing financial support for manuscript preparation activities.

Literature Cited

- Andersen, P.C. (1998) Fatty acid and amino acid profiles of selected peanut cultivars and breeding lines. J. Food Compost. Anal. 11: 100–111. [Google Scholar]

- Basha, S.M., Cherry, J.P. and Young, C.T. (1976) Change in free amino acids, carbohydrates, and protein of maturing seeds from various peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) cultivars. Cereal Chem. 53: 586–597. [Google Scholar]

- Baudoin, J.P. and Maquet, A. (1999) Improvement of protein and amino acid contents in seeds of food legumes. A case study in Phaseolus. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 3: 220–224. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, L.L., Hendrix, K.W., Holbrook, C.C. and Sanders, T.H. (2009) Content of some nutrients in the core of the core of the peanut germplasm collection. Peanut Sci. 36: 104–120. [Google Scholar]

- Field, C.J., Johnson, I. and Pratt, V.C. (2000) Glutamine and arginine: Immunonutrients for improved health. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 32: 77–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovis, A.R., Young, C.T. and Tai, P.Y.P. (1982) Variation in total amino acid percentage in different portions of peanut cotyledons. Peanut Sci. 9: 44–46. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute (2001) SAS/STAT user’s guide, 2nd edn SAS Institute Inc., Cary. [Google Scholar]

- Seijo, G., Lavia, G.I., Fernandez, A., Krapovickas, A., Ducasse, D.A., Bertioli, D.J. and Moscone, E.A. (2007) Genomic relationships between the cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea, Leguminosae) and its close relatives revealed by double GISH. Am. J. Bot. 94: 1963–1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slocum, R.D. (2005) Genes, enzymes and regulation of arginine biosynthesis in plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 43: 729–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistix8 (2003) Statistix8: analytical software user’s manual. Tallahassee, Florida. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatachalam, M. and Sathe, S.K. (2006) Chemical composition of selected edible nut seeds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 54: 4705–4714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.T., Tang, Y.Y., Wang, X.Z., Chen, D.X., Cui, F.G., Chi, Y.C., Zhang, J.C. and Yu, S.L. (2011) Evaluation of groundnut genotypes from China for quality traits. J. SAT Agr. Res. 9: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Win, M.M., Abdul-Hamid, A., Baharin, B.S., Anwar, F., Sabu, M.C. and Pak-Dek, M.S. (2011) Phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of peanut’s skin, hull, raw kernel and roasted kernel flour. Pak. J. Bot. 43: 1635–1642. [Google Scholar]