Abstract

Introduction

Protease activity plays a key role in a wide variety of biological processes including gene expression, protein turnover and development. Misregulation of these proteins has been associated with many cancer types such as prostate, breast, and skin cancer. Thus, the identification of protease substrates will provide key information to understand proteolysis-related pathologies.

Areas covered

Proteomics-based methods to investigate proteolysis activity, focusing on substrate identification, protease specificity and their applications in systems biology are reviewed. Their quantification strategies, challenges and pitfalls are underlined and the biological implications of protease malfunction are highlighted.

Expert commentary

Dysregulated protease activity is a hallmark for some disease pathologies such as cancer. Current biochemical approaches are low throughput and some are limited by the amount of sample required to obtain reliable results. Mass spectrometry (MS) based proteomics provides a suitable platform to investigate protease activity, providing information about substrate specificity and mapping cleavage sites.

Keywords: Proteolysis, substrate recognition, protease activity, Mass Spectrometry, Liquid Chromatography, isotope labeling, protease

1. Introduction

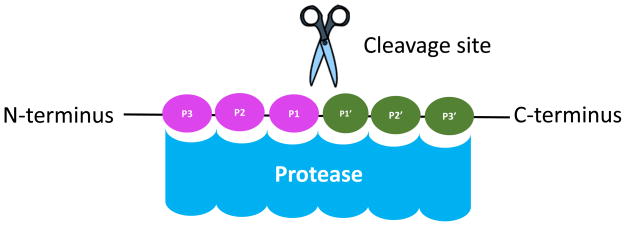

Proteases represent around 1.3% of the human proteome [1], and they are known to play an essential role in biological processes such as cell cycle regulation, inflammation, apoptosis, embryonic development, cell migration and others [2]. One of the better-understood processes mediated by proteases is protein degradation. In this context, proteases regulate protein turnover rates thus preserving cellular homeostasis [3]. In controlled proteolysis, part of the protein is cleaved but one or both resulting pieces remain stable. In general, proteolytic cleavage depends on substrate recognition by the protease in its binding cleft [4]. Given this principle, Berger and Schechter introduced a nomenclature system where the substrate residues around the protease-binding pocket are denoted as P4-P3-P2-P1↓P1′-P2′-P3′-P4′. The arrow indicates that the cleavage occurs between residues P1 and P1′ (Figure 1). In this context, P1 will be situated at the C-terminus of the new peptide while P1′ will be the newly generated N-terminus, called the neo-N terminus (Figure 1) [5, 6]. Proteases are grouped into five different families according to their catalysis mechanism. Aspartic and metalloproteases attack substrate peptide bond using water molecules as a nucleophile. By contrast, threonine, cysteine, and serine proteases catalyze peptide cleavage using an amino acid in the binding pocket (either Thr, Cys, or Ser) as a nucleophile [2] For a more in-depth description of protease families, please refer to [7]. Although this process is highly regulated, aberrant protease activity is a hallmark for several diseases including neurodegeneration, autoimmune disorders, and cancer [2, 8]. Serine proteases for example, are overexpressed in certain types of colorectal cancer. [9] Additionally, Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which are known to regulate important processes like bone development and wound healing [10] have also been associated with cancer progression [11].

Figure 1.

Protease nomenclature system. The protease cleavage site occurs between amino acid p1 and p1′. The new N terminus will be located at p1′, which is also known as the neo terminus [5].

For decades researchers have been focusing on how to identify new protease substrates along with their respective catalysis rates. Enzymology, inhibitor-based assays, and structural biology have provided crucial information on substrate recognition, but these techniques cannot elucidate the biological functions of proteolysis activity, protease expression levels, or the levels of substrate before and after stimulation [12]. Additionally, new approaches are needed in order to identify novel protease substrates and quantify proteolysis events in vivo. Over the last 20 years, mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics has emerged as a suitable technique not only to identify protease activity in vivo, but also to quantify proteolytic peptides. Compared to traditional enzymology approaches, MS-based proteomics provides multiple advantages such as high throughput and sensitivity. Contrary to other methods, MS allows for the identification of multiple cleavage sites in a single experiment. The powerful resolution of this technique also allows the researcher to map peptide cleavage sites upon external stimuli with high confidence and perform accurate quantification of protease activity in a single experiment [13]. MS-based proteomics, which requires as little as femtomolar amounts of sample, also reduces the sample requirement compared to traditional methods such as inhibitor-based assays and structural studies, which require milligrams of input material in order to obtain reliable data. It can be very difficult to obtain this higher quantity of material, especially when working with tissues, primary cell lines, or patient samples [14]. The versatility of MS-based experiments provides a suitable platform to address different questions in one experiment, ranging from targeted approaches, where researchers track a given peptide under different conditions, to discovery-driven techniques for protease identification and quantification. Given the importance of proteases in systems biology and its role in regulation of homeostasis, it is not surprising that scientists have been developing new methods for identification of proteases in mammalian models using MS-based proteomics [15]. Here we review MS-based methods used to identify proteases and their substrates, as well as their application in biological research.

2. Protease activity in health and diseases

The biological implications of protease activity and how they regulate different biological processes have been extensively reviewed elsewhere [16–19]. Protease activity plays an important role in many cellular processes including autophagy, muscle growth, development, and protein turnover [20–22]. Furthermore, it has been shown that intramembrane proteolysis is a regulated mechanism to transmit signals across different cellular compartments. This mechanism has been shown to be conserved from bacteria to humans [23,24]. Intramembrane proteolysis has also been reported to regulate host-pathogen interactions during viral infection [25].

Protease malfunction on the other hand, is highly correlated with cancer progression and other cellular pathologies (Table 1) [18]. In 1946, Albert Fischer suggested that extracellular matrix degradation in cancer cells was a result of proteolytic activity [26]. Subsequently, several studies have revealed specific functions of proteases in several diseases including cancer. For example, intracellular proteases such as caspases are known to regulate apoptosis, and dysregulation of caspases is a well-established hallmark of cancer [18, 27]. Besides cancer, abnormal proteolysis has also been implicated in neuropathies such as Alzheimer’s [28], and Huntington diseases [29]. The role of proteases in these diseases has made them an attractive target for drug development [30]. Together, these studies demonstrate the diverse and critical functions carried out by proteases throughout the cell.

Table 1.

Summary of protease-related diseases

| Cysteine Cathepsin proteases | Breast cancer Colorectal cancer Lung cancer Ovarian cancer Mouth cancer |

[31–33] |

| Matrix metalloproteinases | Cardiovascular diseases Arteritis Multiple sclerosis Glomerular disease |

[34–36] |

| Kallikreinserine proteases | Prostate cancer Skin inflammation Diabetic macular edema |

[37–39] |

| GPI-anchored serine proteases (Testisin and prostasin) | Breast cancer Ovarian cancer |

[40–41] |

Protease activity has been also shown to have a role in gene regulation and epigenetics. The core histones comprise several proteins including H3, H4, H2B, and H2A. Within the nucleosome, each histone has extended N-terminal tails that are heavily and dynamically posttranslationally modified [42]. Many posttranslational modifications (PTMs) on histone tails such as acetylation and methylation have been well characterized and are involved in gene regulation.

However, histone PTMs are not limited to the addition of functional chemical groups; they can also be enzymatically cleaved to alter their function. Although chromatin proteases were first discovered in 1970 [43], it was not until the 90s when this process was described in a more biological context. The first evidence of chromatin proteases was reported by Lin et al. who found that the proteolytic removal of amino termini of the core histones is required for macronuclei development in Tetrahymena [44]. Histone proteolysis has been also reported in higher organisms such as sea urchin, mouse, chicken, and human [45]. In 2008, Duncan and colleagues reported for the first time that the lysosomal protease Cathepsin L cleaves histone H3 during mouse stem cell differentiation [46]. Later in 2014, another group found that cleaved histone H3 drives cellular senescence [47]. Additionally, histone H2A has been also shown to be cleaved in chronic lymphocyte leukemia[48]. These reports represent the first to demonstrate that controlled proteolysis may be involved in gene transcription and epigenetic regulation by altering histone modification profiles.

3. Characterization of novel substrates using terminomics approaches

Mass spectrometry-based approaches enable full characterization of protease activity. The rapid evolution of the proteomics field has opened different venues to investigate proteolytic activity, active site specificity, and novel substrate characterization [49]. Terminomics–based methods rely on positive or negative selection of newly exposed free amine groups derived from a proteolytic event [50].

One such terminomics approach is the subtilagase method, developed by Mahrus and colleagues in 2008. This approach uses an engineered subtiligase enzyme, a variant of the bacterial serine protease subtilisin to selectively label the newly generated N-terminus of a proteolytic peptide (called the neo-N-terminus). The subtiligase enzyme ligates a synthetic peptide to α-amines located at the N-terminus through an ester linkage. This method is able to differentiate protein N-termini from these neo-N-termini because most proteins (around 90%) are N-terminally acetylated, which blocks the subtiligase enzyme from ligating the peptide to the amino group [51,52]. The synthetic peptide contains a TEV protease recognition site and biotin. The resulting labeled peptides can therefore be enriched with streptavidin and eluted after TEV protease cleavage. TEV cleavages leaves Ser-Tyr amino acids ligated to the neo-N-terminus cleavage site, which allows for identification of the modified peptides by LC-MS/MS followed by label-free quantification. Using this method, Mahrus and colleagues were able to identify more than 8000 proteolytic peptides, including 1700 caspase-derived peptides in both healthy and apoptotic cells [53]. Additionally, this method has been successfully used to characterize proteolytic peptides present in human blood. In this study, researchers were able to find more than 700 unique peptides as result of endo and exopeptidase activity. These peptides were quantified using isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification (iTRAQ) [54]. These experiments illustrate that the subtilagase approach is an unbiased and highly reproducible approach that can identify large amount of peptides from complex samples. One of the drawbacks of this approach, however, is that labeling with the synthetic peptide may not be complete. This limitation can be overcome by using large amount of starting material.

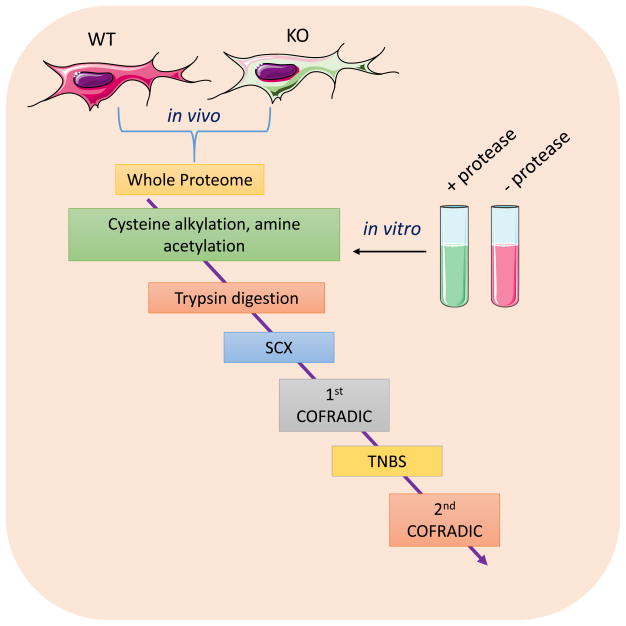

Alternatively, other terminomics methods have focused on negative selection of neo-N-terminal peptides by filtering out tryptic peptides from peptides derived from the protease of interest. One example is Combined Fractionation Diagonal Chromatography (COFRADIC) (Figure 2). COFRADIC was originally developed in 2003, but since then, several adaptations have been developed.

Figure 2.

Diagram of Terminal Amine Isotopic Labeling of Substrate (TAILS) workflow. In general, after the sample is exposed to the protease, primary amines are chemically protected. After trypsin digestion, a new unlabeled N-terminus is generated, facilitating their binding to the polyglycerol matrix. These peptides are captured after ultracentrifugation [24].

This method can be performed in vivo or in vitro. For the in vitro method, proteins are incubated with the protease of interest to generate proteolyzed peptides. A control sample is used where the protease is omitted. In the in vivo method, cells in which the protease of interest is knocked out are used as a control [55–57]. In the following step, cysteine residues are reduced and alkylated to block the formation of disulfide bridges, which complicate MS analysis. Subsequently, all primary amines are chemically protected via an N-acetylation reaction using N-hydroxysuccinimide. This step will acetylate all protein N-termini, neo-N-termini, as well as lysine side chains. The samples are then digested with trypsin. However, since lysine side chains were acetylated in the previous step, trypsin will only cleave after arginine residues. Strong Cation Exchange Chromatography (SCX) is then used to separate all internal peptides from peptides containing the protease cleavage site as well as N-terminal, neo-N-terminal, and C-terminal peptides. Internal peptides will have one additional charge compared to the other peptides because they contain an amino N-terminal group as well as a C-terminal arginine residue. Conversely, because the protein N-terminus and any neo-N-termini are acetylated, they will not contain a positive charge at the N-terminus but will carry a positive charge at the arginine at the C-terminus. C-terminal peptides and peptides containing a protease cleavage will not contain an arginine at the C-terminus and thus will only be charged at the N-terminal amino group. Therefore, internal peptides will bind more strongly to the SCX resin whereas peptides containing a protease cleavage site as well as N-terminal, neo-N-terminal, and C-terminal peptides will elute in the flow through. This flow through fraction contains the peptides of interest and is therefore used for the first round of reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC). Resulting fractions are treated with 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (TNBS), which will modify the amino group of the N-terminus of all C-terminal peptides and peptides containing a protease cleavage site. This modification greatly increases the hydrophobicity of the peptide, causing it to shift retention times on RP-HPLC. A second round of RP-HPLC is performed on these peptides to identify the peptides that display a shift in retention time, which indicate C-terminal peptides and peptides that contain the protease cleavage site. These peptides are then identified by LC-MS/MS. For quantification purposes, stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) is performed, peptide identification and quantification is done using the Mascot platform [58]. One of limitations of this method is the requirement of several chromatographic steps which results in sample loss. Additionally, peptides containing prolines or histines are lost during the SCX step unless they were previously derivatized. Despite its limitations, COFRADIC has been extensively applied to identify novel protease substrates. Some of these applications include identification of proteolytic peptides during Fas-induced apoptosis, Taxol-mediated cell death and proteolysis during acute myelogenous leukemia [56,57,59].

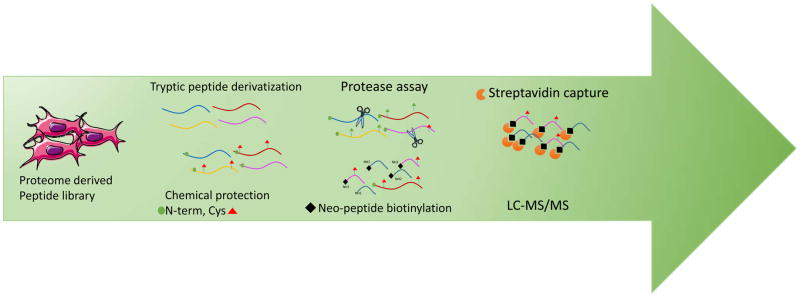

Another method, Terminal Amine Isotopic Labeling of Substrate (TAILS), can be used to enrich and identify protease cleavage sites (Figure 3). In this method, the sample is exposed to the protease of interest. Then, any primary amine groups are modified using isobaric labeling such as Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) or iTRAQ [60]. Alternatively, primary amines can also be modified via reductive dimethylation using heavy-labeled formaldehyde (D2C13). Typically, a control sample is made where the protease is excluded and light formaldehyde is used to derivatize primary amines. The control (light) and protease-treated (heavy) samples are then mixed in equal amounts and digested with trypsin, exposing new and unlabeled N-termini. Then, polyglycerol aldehyde polymer, which covalently binds primary amines, is added to the sample. Any tryptic peptides will bind to the polymer. Peptides generated from the protease, however, will not bind because their N-termini were blocked with the formaldehyde. Ultrafiltration is then used to filter out the peptides bound to the polymer, leaving only the peptide cleaved by the protease and any protein N-terminal peptides. LC-MS/MS is used to identify the peptides. Depending on the labeling method used, peptide can be quantify using iTRAQ [61] or TMT [62]. Any peptides that were discovered in the protease sample but not the control sample are considered substrates for the protease used in the experiment. One of the main advantages of this method is that it allows for localization of cleavage site(s). Additionally, it is suitable for in vivo studies and allows several different quantification methods to be used. Kleifeld and colleagues applied TAILS to investigate matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 cleavage sites in mouse fibroblasts. They were able to find over 280 cleavage sites for this protease. Moreover, they showed that MMP-11 protease, another metalloproteinase known to be dysregulated in breast cancer, cleaves apoptosis inducer gelactin-1 and endoplasmin, a protein known to promote tumorigenesis [63] thus showing the robustness of this method.

Figure 3.

Schematic workflow of Proteomics Identification of Protease Cleavage Sites (PICS). After trypsin digestion, amines are derivatized by reductive methylation and cysteines are blocked with iodoacetamide. The peptide library is then incubated with the protease. Neo peptides are biotinylated and recovered using streptavidin [64–65].

The Abbott group has applied the TAILS method to investigate a novel substrate of dipeptidyl peptidases 8 and 9 (DP8 and DP9), which are target proteases for type II diabetes treatment. Additionally, these proteases have been reported to be dysregulated in chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and testicular and ovarian carcinoma cell lines, highlighting the need to characterize cellular substrates of DP8 and DP9 [66]. This study identified several substrates for DP8 and DP9, including adenylate kinase 2, a key for cellular homeostasis, suggesting a novel role for DP8 and DP9 in energy metabolism [66]. Furthermore, others have used the TAILS approach to discover novel substrates of membrane–type 6 matrix metalloprotease (MT6-MMP) in neutrophils [67]. During inflammation, MT6-MMP and other metalloproteases are known to be secreted by neutrophils, but only seven of its downstream targets were known prior to this study.

After applying the TAILS workflow, Starr and colleagues reported over 70 new substrate of MTP6, revealing novel roles of MTP-6 during wound healing and inflammation [67].

4. Identifying novel substrates of membrane proteases using affinity methods

Affinity-based methods have been exploited to identify substrates of cell-surface proteases and intramembrane proteases. These proteases generally cleave proteins at the cell surface, releasing the cleaved peptide into the cellular media. Some of these methods have been recently reviewed by Müller and colleagues [68]. Cell-surface proteases have been shown to play a vital role in biological processes such as inflammation and cell migration [69]. Additionally, intramembrane proteases, have been associated with aging and Alzheimer’s diseases [70]. The biological role of these proteases and their implications in human diseases highlight the importance of substrate characterization.

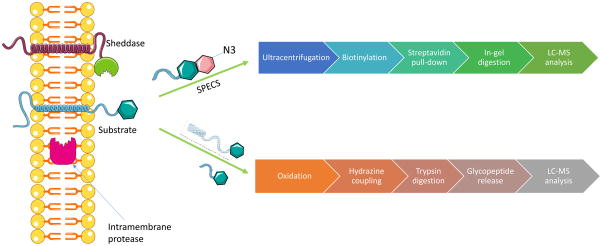

The identification of cell-surface proteases through the combination of metabolic labeling and mass spectrometry-based proteomics strategies has led to the characterization of protease substrates in vivo. A big caveat in the study of secreted proteins using MS is that these cleaved peptides have a much lower abundance compared to other serum proteins such as albumin present in the media. The Lichtenthaler group reduced the contamination of serum proteins by developing a method called secretome protein enrichment with click sugars (SPECS) [71]. In SPECS, glycoproteins are metabolically labeled with ManNAz (N-azidoacetyl-mannosamine-tetraacetylated), which after cellular uptake is converted to N-azidoacetyl-sialic acid, which is then fused to the N- and O-linked glycans. After 48 h of labeling, free ManNAZ is removed by ultracentrifugation while secreted proteins remain in the supernatant. In the next step of the workflow, the azide group on the labeled sugar is linked to a biotin moiety, which allows for streptavidin pull-down. Proteins are finally resolved by SDS-PAGE, subjected to in gel digestion and, LC-MS identification. Peptides are further identified and quantified using the label-free quantification platform of MaxQuant. To identify membrane protease substrates, a control sample where the cells are treated with an inhibitor specific to the protease of interest is added.

The SPECS method has been successfully employed to characterize substrates of the beta-secretase enzyme BACE 1, a drug target protease in Alzheimer’s disease [71]. Another application of this method includes the characterization of ADAM10 metalloproteinase in primary cortical neurons [72]. Although this approach does not provide information regarding the protease cleavage site, the study of in vivo membrane proteolysis is suitable. However, only membrane-bound proteases (sheddases) can be studied using SPECS.

Alternatively, substrates of BACE1 have also been identified from pancreatic cells using a glyco-enrichment approach [68.73]. In this method, the carbohydrates are oxidized to aldehydes that are then bound to a hydrazide resin. After unbound proteins are washed out, proteins are trypsin digested and glycopeptides are released using peptide-N-glycosidase F (PNGaseF) [74]. Resulting peptides are analyzed by LC-MS/MS and identified using PeptideProphet. Other variants of this approach have been reviewed elsewhere [10]. Similar to SPECS, glyco-enrichment does not map protease cleavage site, however. This method is also appropriate to investigate in vivo membrane proteolysis. Compared to SPECS, glycol-enrichment is not limited to sheddases protease research as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

COFRADIC approach. For in vivo studies, WT cells and cells where the protease is knocked out (KO) are analyzed. After the whole proteome is extracted, proteins are alkylated. All primary amine are acetylated prior to trypsin digestion. Neo-N-terminal peptides are further identified after multiple chromatographic steps.

5. Gel migration-based methods for substrate recognition

Gel migration-based techniques have been widely used in the field of controlled proteolysis, although gel-free methods have become more popular in recent years. Both one dimension and 2D gel-based methods have been exploited over the years. One-dimensional approaches involve protein separation based on molecular weight. After incubation or exposure with a protease, substrate proteins will have a different molecular weight which can be visualized after staining [15]. The cleaved product is further excised and analyzed by MS. When a second dimension is applied, proteins get separated not only based on their molecular weight but also based on their isoelectric point (pI). Similar to the one-dimensional technique, if a given protein is cleaved, it will present a different migration pattern. Downstream experiments also involve gel extraction and identification by MS. Although two-dimensional methods have been less exploited, in 2004, Bredemeyer and coworkers identified substrates of granzyme B during apoptosis using 2D electrophoresis followed by MS/MS [75]. More recently, Dinnes and coworkers, utilized 2D based strategy to identify novel cleavage sites of apolipoprotein, the major component HDL by Cathepsin B in human macrophages. One of the cleavage sites identified turned out to have a functional role as it was only present during differentiation from monocytes to macrophages [75]. In 2008, the Cravatt lab used a 1D gel migration technique called Protein Topography and Migration Analysis Platform (PROTOMAP,) to identify known caspase substrates during cellular apoptosis, and 100 new proteins that were cleaved during apoptosis [77].

6. Profiling specificity using peptide libraries

MEROPS [78] is a database founded in 1996 that contains information about known proteases as well as their substrates and inhibitors. The database is updated every year and contains several model organisms such as mouse, human, fruit fly, and yeast [79]. This wealth of information has pushed researchers to study novel substrates and protease kinetics in a more targeted fashion rather than pursuing large exploratory studies. Many of these studies include the use of peptide libraries, or collections of peptides defined by the scientist. These can range from synthetic peptides derived from a protein of interest or whole-cell proteome digests. These libraries then serve as the database during the data analysis step. Initial efforts to characterize protease kinetics using peptide libraries were mainly based on fluorescence reporters, where the peptides were chemically labeled with two fluorophore molecules and upon proteolytic cleavage, the emission spectra was measured [28, 29]. Some of the limitations of these techniques include low throughput and the fact that reporter groups can affect protease recognition sites. With the advances in the proteomics field and the development of high-resolution mass spectrometers, researchers have developed rapid and accurate methods to characterize protease kinetics using peptide libraries, overcoming the need of fluorescence labeling.

Multiplex substrate profiling by mass spectrometry (MSP-MS), developed in 2012 by the Craik group, presents a rapid and simple platform to study substrate specificity. In this method, a peptide library is designed containing 124 peptides with different chemical properties based on the nature of protease in question. The peptides contain 14 residues to ensure enough room for protease accessibility and substrate recognition. Prior to exposure to the protease, the peptides are characterized by LC-MS/MS. This chromatographic profile is then used to measure the relative abundance of each peptide. Here, the relative abundance of each peptide is calculated by peak integration using Xcalibur software. After protease exposure, the relative abundances of the peptides are measured again, and any substrate proteins are expected to decrease in abundance over time as they get cleaved. After the development of the method, the authors used it to study three biological problems; (1) They characterized peptidase activity of Cathepsin E, (2) they studied the cleavage efficiency of the apoptotic protease granzyme B, and, (3) showed that MSP-MP can be used in complex samples such as proteolytic secretions of Schistosoma, a flatworm parasite known to cause schistosomiasis. Although this method provides direct identification of cleavage sites, it is limited by the size of the library and is not applicable for in vivo studies [64].

Peptide libraries can also be generated from a cell lysate. In 2008, the Overall group was the first to demonstrate this with their method called Proteomic Identification of Protease Cleavage Sites (PICS) (Figure 5). PICS uses human proteome-derived libraries to identify primary protease cleavage sites [65]. The general workflow of this method includes trypsinization followed by two steps of chemical protection. In the first step, amine groups are protected using reductive dimethylation. Then, cysteine residues are blocked with iodoacetamide. The library is then purified and incubated with the protease of interest. The resulting neo-peptides are further biotinylated and recovered using streptavidin. Finally peptides are analyzed by LC-MS/MS. Three years later, the same group released an online platform for data analysis, WebPics [80].

Figure 5.

Comparison between SPECS and glyco-enrichment method. While SPECS is only applicable to the study of sheddase proteases, glycol-enrichment can also capture peptides derived from intramembrane protease activity.

In 2016, a variation of PICS was developed that circumvented the chemical protection steps and eliminated the need for enrichment. Developed by Martin L. Biniossek and colleagues, this method uses proteome-derived peptide libraries combined with quantitative proteomics strategies without the need for peptide synthesis. This approach focuses on comparing two peptide populations (protease treated and control) that have been chemically labeled after the reductive dimethylation step. Relative quantification and cleavage site identification is achieved by LC-MS/MS [81]. The workflow of this method starts by preparing the peptide library. Here, the authors used E.coli cell lysates digested with either trypsin, GluC, or LysC. The resulting peptides were purified using commercial kits. The library is incubated with the protease of interest for a given time, and the reaction is then quenched by heat inactivation. Resulting peptides are chemically labeled using D2C13O (heavy) whereas control peptides that were not exposed to the protease are labeled with H2CO (light). In the final step, both light and heavy peptides are mixed at equal amount and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. Peptides that have different abundances between the light and heavy labeled samples were those affected by the protease of interest. The authors provided several validation experiments to demonstrate the robustness of their technique. They started with two well-characterized proteases trypsin and human caspase-3 and their results correlated with previously reported data. They further applied this method to investigate the specificity of HERVK, a human-encoded retroviral protease and the chlamydial protease-like activity factor (CPAF) [80].

6. Analyzing in vivo proteolysis with Middle-down and Top-down proteomics

The typical proteomics workflow involves the analysis of tryptic peptides. This technique is better known as bottom-up proteomics [82]. One pitfall of bottom-up proteomics is that the co-occurance of two PTMs cannot be monitored if there is a tryptic digest site located between them. Alternatively, in middle-down proteomics, researchers analyze longer peptides (4–7kDa) that are generated after GluC or AspN digestion [83]. Middle-down proteomics has the advantage of retaining a higher degree of peptide connectivity, making it easier to study PTMs that are further apart in sequence. In the epigenetics field, for example, this method is widely used to investigate histone PTMs during cell development [15, 75 ]. Recently, this method has also been used to study histone proteolysis [84]. As previously discussed, histone proteolysis has been reported to influence gene expression during cell differentiation, and has also been observed in cancer cell lines [46, 85]. Thus, understanding histone proteolysis can elucidate the pathologies of some diseases such as cervical cancer where histone proteolysis has also been reported [84].

In addition to middle-down proteomics, proteolysis events can be studied using top-down MS, where the intact protein is analyzed using a high-resolution mass spectrometer. In this context, proteins are usually isolated by HPLC, Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) or Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography (HILIC) prior MS analysis [86]. Top-down MS retains complete connectivity of the protein, allowing the researcher to robustly monitor PTM content, mutations, spliced isoforms, and proteolytic events [87,88]. Recently, the Hunt lab reported cleaved isoforms of histone H2A and H2B in HeLa cells using top-down MS [89]. In this study, histone proteins were isolated using RP-HPLC prior to MS analysis. The researchers were able to obtain more than 90% sequence coverage. Additionally, they estimated the abundance of cleaved histone to be less than 1%, emphasizing the capability of this approach. Other groups have opted to combine middle-down and top-down approaches to investigate histone proteolysis. Tvardovskiy and colleagues, for example, reported proteolysis of histone H2B and H3 in human hepatocytes and carcinoma cell lines. This study did not only map cleaved residues, but also reported a negative interplay between some histone PTMs and histone proteolysis. The authors used label-free quantification proteome discoverer and the IsoScale software [83]. Although top-down and middle-down approaches do not provide information about the protease responsible for the cleavage, they do provide direct evidence of in vivo proteolysis, which is a limitation of many other methods previously described here.

7. Expert commentary

It is clear that the study of protease activity using mass spectrometry-based approaches has revealed critical information about substrate specificity, which is key for development of new drugs. Table 2 provides a summary of techniques covered in this article. While other biochemical approaches can address similar questions, they also have limitations. For instance, enzymology-based approaches require milligram amounts of purified protease in addition to a known substrate. Although this method provides important information about the catalysis rate of the protease, it is unable to map cleavage sites. MS-based proteomics has been shown to be a powerful method to investigate protease activity, providing confident results in a high-throughput manner. Using MS, researchers are able to map novel cleavage sites, obtain quantitative information that can be translated in catalysis rate, all in one experiment, reducing sample requirements and analysis time [90].

Table 2.

Summary of methods for substrate discovery using MS

By reducing the sample requirement compared to other methodology, MS approaches are often more desirable over traditional methods in the field. One of the biggest challenges in the field of MS is still the lack of in vivo validation, which is often done by immunoblotting. Many groups have been able to find novel substrates and profile protease specificity with the methods described here, but whether these proteolytic events occur in the cell or are possibly an artifact of sample preparation is still unclear. While top-down MS is mainly used to identify novel proteins [94], few attempts to study proteolysis events in vivo using top-down and middle-down proteomics have been done, especially in the epigenetics field [67]. These studies can identify a proteolytic event in vivo to the characterization of the protease responsible for that cleaved, this can be achieved combining different biochemical approaches.

8. Five-year view

The biological function of protease activity and its role in cellular pathologies have been well established. However, the mechanisms underlying these processes are still not well understood. With the implementation of the human proteome project, it is very likely that more disease-related proteases will be uncovered. It is very clear that understanding protease activity, discovering novel substrates, and investigating their mechanisms provides crucial information in order to develop novel drugs. With the increasing number of reports of new proteomics approaches along with new bioinformatics tools and new developments in instrumentation, it is very likely that in the coming years more methods will be developed. Protease researchers are moving toward gel-free approaches, mainly because of the lack of reproducibility and low throughout of gel-based methods. In the coming years, we expect the development of more unbiased approaches that can provide a wider picture of protease specificity in systems biology. Finally, we also anticipate the development of new methods that will allow to researchers to monitor proteolysis events in vivo.

Table 3.

Quantification strategy and peptide identification platform

| Method | Quantification strategy | Peptide ID platform |

|---|---|---|

| Subtiligase | Label freeiTRAQ |

Protein Prospector V.5.2.2 |

| COFRADIC | SILAC | Mascot |

| TAILS | ITRAQ TMT |

Mascot X!Tandem Proteome discover |

| SPECS | Label free | Maxquant |

| Glyco-enrichment | Label free | PeptideProphet |

Key issues.

Proteases are widely expressed in eukaryotic cells. They play an essential role in cell cycle regulation, gene expression, inflammation, apoptosis, embryonic development, cell migration and other processes.

Dysregulated proteolysis is an underlying contribution to many diseases such as Alzheimer’s and cancer in addition to autoimmune disorders.

The growing evidence of protease-related diseases highlight the need to develop better tools in order to understand molecular mechanisms of protease activity.

Mass spectrometry (MS) based-proteomics is a suitable technique that allows accurate identification and quantification of protease activity.

The rapid growth in the proteomics field has led to the development of powerful instrumentation that overcomes the sample limitation problem.

Substrate identification can be achieved using different proteomics approaches including gel-based and gel-free methods.

Protease specificity as well as protease kinetic profiles can be studied utilizing peptide library-based approaches.

Acknowledgments

9. Funding

We gratefully acknowledge funding from NIH grants GM110174, GM110174-S1 CA196539 and the Chemical Biology Interface training grant.

Footnotes

10. Declaration of interest

The authors do not have other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers.

- 1.van den Berg BHJ, Tholey A. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics strategies for protease cleavage site identification. Proteomics. 2012 Feb;12(4–5):516–529. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Puente XS, Sánchez LM, Overall CM, et al. Human and mouse proteases: a comparative genomic approach. Nat Rev Genet. 2003 Jul;4(7):544–558. doi: 10.1038/nrg1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turk B. Targeting proteases: successes, failures and future prospects. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006 Sep;5(9):785–799. doi: 10.1038/nrd2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turk BE, Huang LL, Piro ET, et al. Determination of protease cleavage site motifs using mixture-based oriented peptide libraries. Nat Biotechnol. 2001 Jul;19(7):661–667. doi: 10.1038/90273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger A, Schechter I. Mapping the active site of papain with the aid of peptide substrates and inhibitors. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1970 Feb;257(813):249–264. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1970.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Impens F, Colaert N, Helsens K, et al. MS-driven protease substrate degradomics. Proteomics. 2010 Mar;10(6):1284–1296. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bond JS, Butler E. Intracellular Proteases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56(1):333–364. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.002001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biniossek ML, Niemer M, Masksimchuk K, et al. Identification of protease specificity by combining proteome-derived peptide libraries and quantitative proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2016 Jul;15(7):2515–2524. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O115.056671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu X, Quan B, Tian Z, et al. Elevated expression of KLK8 predicts poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;88:595–602. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.01.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Löffek S, Schilling O, Franzke C-W. Biological role of matrix metalloproteinases: a critical balance. Eur Respir J. 2011 Jul;38(1):191–208. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00146510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gialeli C, Theocharis AD, Karamanos NK. Roles of matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression and their pharmacological targeting. Febs J. 2011 Jan;278(1):16–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doucet A, Overall CM. Protease proteomics: revealing protease in vivo functions using systems biology approaches. Mol Aspects Med. 2008 Oct;29(5):339–358. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aebersold R, Mann M. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nature. 2003 Mar;422(6928):198–207. doi: 10.1038/nature01511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gillette MA, Carr SA. Quantitative analysis of peptides and proteins in biomedicine by targeted mass spectrometry. Nat Methods. 2013 Jan;10(1):28–34. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klingler D, Hardt M. Profiling protease activities by dynamic proteomics workflows. Proteomics. 2012 Feb;12(4–5):587–596. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neurath H, Walsh KA. Role of proteolytic enzymes in biological regulation (a review) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976 Nov;73( 11):3825–3832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.11.3825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vanaman TC, Bradshaw RA. Proteases in cellular regulation minireview series. J Biol Chem. 1999 Jul;274(29):20047–20047. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18•.López-Otín C, Matrisian LM. Emerging roles of proteases in tumour suppression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007 Oct;7(10):800–808. doi: 10.1038/nrc2228. Discusses the importance of protease activity in cancer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rakash S. Role of proteases in cancer: A review. Research Gate. 2012 Oct;7(4):90–101. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaminskyy V, Zhivotovsky B. Proteases in autophagy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012 Jan;1824(1):44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bell RAV, Al-Khalaf M, Megeney LA. The beneficial role of proteolysis in skeletal muscle growth and stress adaptation. Skelet Muscle. 2016;6:16. doi: 10.1186/s13395-016-0086-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22••.López-Otín C, Bond JS. Proteases: multifunctional enzymes in life and disease. J Biol Chem. 2008 Nov;283(45):30433–30437. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800035200. Discusses the biological role of proteases and how they are related to diseases. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown MS, Ye J, Rawson RB, et al. Regulated intramembrane proteolysis: a control mechanism conserved from bacteria to humans. Cell. 2000 Feb;100(4):391–398. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80675-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rawson RB. Regulated intramembrane proteolysis: from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus. Essays Biochem. 2002;38:155–168. doi: 10.1042/bse0380155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye J. Roles of regulated intramembrane proteolysis in virus infection and antiviral immunity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013 Dec;1828( 12):2926–2932. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fischer A. Mechanism of the proteolytic activity of malignant tissue cells. Nature. 1946 Apr;157:442. doi: 10.1038/157442c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Egeblad M, Werb Z. New functions for the matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002 Mar;2(3):161–174. doi: 10.1038/nrc745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Strooper B. Proteases and proteolysis in Alzheimer disease: a multifactorial view on the disease process. Physiol Rev. 2010 Apr;90( 2):465–494. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00023.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wellington CL, Ellerby LM, Leavitt BR, et al. Huntingtin proteolysis in Huntington disease. Clin Neurosci Res. 2003 Sep;3(3):129–139. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verhelst SHL. Intramembrane proteases as drug targets. Febs J. 2016 Nov; doi: 10.1111/febs.13979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olson OC, Joyce JA. Cysteine cathepsin proteases: regulators of cancer progression and therapeutic response. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015 Dec;15(12):712–729. doi: 10.1038/nrc4027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gong F, Peng X, Luo C, et al. Cathepsin B as a potential prognostic and therapeutic marker for human lung squamous cell carcinoma. Mol Cancer. 2013;12:125. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang W-E, Ho C-C, Yang S-F, et al. Cathepsin B expression and the correlation with clinical aspects of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Plos One. 2016 Mar;11(3):e0152165. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malemud CJ. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in health and disease: an overview. Front Biosci J Virtual Libr. 2006 May;11:1696–1701. doi: 10.2741/1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu J, Van Den Steen PE, Sang Q-XA, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors as therapy for inflammatory and vascular diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007 Jun;6(6):480–498. doi: 10.1038/nrd2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lenz O, Elliot SJ, Stetler-Stevenson WG. Matrix metalloproteinases in renal development and disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000 Mar;11( 3):574–581. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V113574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clements JA, Willemsen NM, Myers SA, et al. The tissue kallikrein family of serine proteases: functional roles in human disease and potential as clinical biomarkers. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2004 Jan;41( 3):265–312. doi: 10.1080/10408360490471931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamasaki K, Di Nardo A, Bardan A, et al. Increased serine protease activity and cathelicidin promotes skin inflammation in rosacea. Nat Med. 2007 Aug;13(8):975–980. doi: 10.1038/nm1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feener EP. Plasma kallikrein and diabetic macular edema. Curr Diab Rep. 2010 Aug;10(4):270–275. doi: 10.1007/s11892-010-0127-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen L-M, Chai KX. Prostasin serine protease inhibits breast cancer invasiveness and is transcriptionally regulated by promoter DNA methylation. Int J Cancer. 2002 Jan;97(3):323–329. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mok SC, Chao J, Skates S, et al. Prostasin, a potential serum marker for ovarian cancer: identification through microarray technology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001 Oct;93(19):1458–1464. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.19.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strahl BD, Allis CD. The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature. 2000 Jan;403(6765):41–45. doi: 10.1038/47412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Azad GK, Tomar RS. Proteolytic clipping of histone tails: the emerging role of histone proteases in regulation of various biological processes. Mol Biol Rep. 2014 Jan;41(5):2717–2730. doi: 10.1007/s11033-014-3181-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin R, Cook RG, Allis CD. Proteolytic removal of core histone amino termini and dephosphorylation of histone H1 correlate with the formation of condensed chromatin and transcriptional silencing during Tetrahymena macronuclear development. Genes Dev. 1991 Sep;5(9):1601–1610. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.9.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dhaenens M, Glibert P, Meert P, et al. Histone proteolysis: A proposal for categorization into ‘clipping’ and ‘degradation,’. BioEssays. 2015 Jan;37(1):70–79. doi: 10.1002/bies.201400118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duncan EM, Muratore-Schroeder TL, Cook RG, et al. Cathepsin L proteolytically processes histone H3 during mouse embryonic stem cell differentiation. Cell. 2008 Oct;135(2):284–294. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duarte LF, Young ARJ, Wang Z, et al. Histone H3.3 and its proteolytically processed form drive a cellular senescence programme. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5210. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Glibert P, Vossaert L, Van Steendam K, et al. Quantitative proteomics to characterize specific histone H2A proteolysis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and the myeloid THP-1 cell line. Int J Mol Sci. 2014 May;15(6):9407–9421. doi: 10.3390/ijms15069407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schlage P, auf dem Keller U. Proteomic approaches to uncover MMP function. Matrix Biol. 2015 May;44–46:232–238. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50••.Rogers LD, Overall CM. Proteolytic post-translational modification of proteins: proteomic tools and methodology. Mol Cell Proteomics MCP. 2013 Dec;12(12):3532–3542. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.031310. Describes MS-based approaches to study proteolysis, including quantification and data analysis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mahrus S, Trinidad JC, Barkan DT, et al. Global sequencing of proteolytic cleavage sites in apoptosis by specific labeling of protein N termini. Cell. 2008 Sep;134(5):866–876. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Drazic A, Myklebust LM, Ree R, et al. The world of protein acetylation. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA Proteins Proteomics. 2016 Oct;1864( 10):1372–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wiita AP, Seaman JE, Wells JA. Global analysis of cellular proteolysis by selective enzymatic labeling of protein N-termini. MethodsEnzymol. 2014;544:327–358. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-417158-9.00013-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wildes D, Wells JA. Sampling the N-terminal proteome of human blood. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010 Mar;107(10):4561–4566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914495107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gevaert K, Impens F, Van Damme P, et al. Applications of diagonal chromatography for proteome-wide characterization of protein modifications and activity-based analyses. Febs J. 2007 Dec;274( 24):6277–6289. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Damme P, van Damme J, Demol H, et al. A review of COFRADIC techniques targeting protein N-terminal acetylation. BMC Proc. 2009 Aug;3(Suppl 6):S6. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-3-S6-S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Staes A, Impens F, van Damme P, et al. Selecting protein N-terminal peptides by combined fractional diagonal chromatography. Nat Protoc. 2011 Jul;6(8):1130–1141. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Plasman K, Demol H, Bird PI, et al. Substrate specificities of the granzyme tryptases A and K. J Proteome Res. 2014 Dec;13( 12):6067–6077. doi: 10.1021/pr500968d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Caboche S, Audebert C, Hot D. High-throughput sequencing, a versatileweapon to support genome-based diagnosis in infectious diseases: applications to clinical bacteriology. Pathogens. 2014 Apr;3(2):258–279. doi: 10.3390/pathogens3020258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Prudova A, auf dem Keller U, Butler GS, et al. Multiplex N-terminome analysis of MMP-2 and MMP-9 substrate degradomes by iTRAQ-TAILS quantitative proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics MCP. 2010 May;9(5):894–911. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M000050-MCP201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Prudova A, Gocheva V, auf dem Keller U, et al. TAILS N-terminomics and proteomics show protein degradation dominates over proteolytic processing by cathepsins in pancreatic tumors. Cell Rep. 2016 Aug;16(6):1762–1773. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.06.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Klein T, Fung S, Renner F, et al. The paracaspase MALT1 cleaves HOIL1 reducing linear ubiquitination by LUBAC to dampen lymphocyte NF-κB signalling. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8777. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kleifeld O, Alain D, auf dem Keller U, et al. Isotopic labeling of terminal amines in complex samples identifies protein N-termini and protease cleavage products. Nat Biotechnol. 2010 Mar;28( 3):281–288. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.O’Donoghue AJ, Eroy-Reveles AA, Knudsen GM, et al. Global identification of peptidase specificity by multiplex substrate profiling. Nat Methods. 2012 Nov;9(11):1095–1100. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schilling O, Overall CM. Proteome-derived, database-searchable peptide libraries for identifying protease cleavage sites. Nat Biotechnol. 2008 Jun;26(6):685–694. doi: 10.1038/nbt1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wilson CH, Dono I, Alain D, et al. Identifying natural substrates for dipeptidyl peptidases 8 and 9 using Terminal Amine Isotopic Labeling of Substrates (TAILS) reveals in vivo roles in cellular homeostasis and energy metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2013 May;288( 20):13936–13949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.445841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Starr AE, Bellac CL, Dufour A, et al. Biochemical characterization and n-terminomics analysis of leukolysin, the membrane-type 6 Matrix Metalloprotease (MMP25) CHEMOKINE AND VIMENTIN CLEAVAGES ENHANCE CELL MIGRATION AND MACROPHAGE PHAGOCYTIC ACTIVITIES. J Biol Chem. 2012 Apr;287(16):13382–13395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.314179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Müller SA, Scilabra SD, Lichtenthaler SF. Proteomic substrate identification for membrane proteases in the brain. Front Mol Neurosci. 2016;9 doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2016.00096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cai Z, Anling Z, Swati C, et al. Activation of cell-surface proteases promotes necroptosis, inflammation and cell migration. Cell Res. 2016 Aug;26(8):886–900. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang JY, Bruno AM, Patel CA, et al. Human membrane metalloendopeptidase-like protein degrades both beta-amyloid 42 and beta-amyloid 40. Neuroscience. 2008 Jul;155(1):258–262. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kuhn P-H, Koroniak K, Hogl S, et al. Secretome protein enrichment identifies physiological BACE1 protease substrates in neurons. Embo J. 2012 Jun;31(14):3157–3168. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kuhn P-H, Colombo AV, Schusser B, et al. Systematic substrate identification indicates a central role for the metalloprotease ADAM10 in axon targeting and synapse function. Elife. 2016;5:e12748. doi: 10.7554/eLife.12748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stützer I, Selevsek N, Esterházy D, et al. Systematic proteomic analysis identifies β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 2 and 1 (BACE2 and BACE1) substrates in pancreatic β-cells. J Biol Chem. 2013 Apr;288(15):10536–10547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.444703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang H, Li X, Martin DB, et al. Identification and quantification of N-linked glycoproteins using hydrazide chemistry, stable isotope labeling and mass spectrometry. Nat Biotechnol. 2003 Jun;21( 6):660–666. doi: 10.1038/nbt827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bredemeyer AJ, Lewis RM, Malone JP, et al. A proteomic approach for the discovery of protease substrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Aug;101(32):11785–11790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402353101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dinnes DLM, White MY, Kockx M, et al. Human macrophage Cathepsin B-mediated C-terminal cleavage of apolipoprotein A-I at Ser228 severely impairs antiatherogenic capacity. Faseb J. 2016;12:4239–4255. doi: 10.1096/fj.201600508R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dix MM, Simon GM, Cravatt BF. Global mapping of the topography and magnitude of proteolytic events in apoptosis. Cell. 2008 Aug;134(4):679–691. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. [Accessed 24 Mar 2017];MEROPS - the Peptidase Database. [Online]. Available: http://merops.sanger.ac.uk/

- 79•.Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ, Finn R. Twenty years of the MEROPS database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016 Jan;44(D1):D343–D350. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1118. Describes the evolution of MEROPS database in the last years. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80••.Schilling O, auf dem Keller U, Overall CM. Factor Xa subsite mapping by proteome-derived peptide libraries improved using WebPICS, a resource for proteomic identification of cleavage sites. Biol Chem. 2011 Nov;392(11):1031–1037. doi: 10.1515/BC.2011.158. Describes the development of proteome-derived peptide libraries to analyze protease activity. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Martinelli P, Rugarli EI. Emerging roles of mitochondrial proteases in neurodegeneration. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA Bioenerg. 2010 Jan;1797(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Karch KR, Denizio JE, Black BE, et al. Identification and interrogation of combinatorial histone modifications. Front Genet. 2013;4:264. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sidoli S, Scwämmle V, Ruminowicz C, et al. Middle-down hybrid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry workflow for characterization of combinatorial post-translational modifications in histones. Proteomics. 2014 Oct;14(19):2200–2211. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201400084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tvardovskiy A, Wrzesinski K, Sidoli S, et al. Top-down and middle-down protein analysis reveals that intact and clipped human histones differ in post-translational modification patterns. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2015 Dec;14(12):3142–3153. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M115.048975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sandoval-Basilio J, Serafín-Higuera N, Reyes-Hernandez OD, et al. Low proteolytic clipping of histone H3 in cervical cancer. J Cancer. 2016 Aug;7(13):1856–1860. doi: 10.7150/jca.15605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Garcia BA. What does the future hold for top down mass spectrometry? J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2010 Feb;21(2):193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang H, Ge Y. Comprehensive analysis of protein modifications by top-down mass spectrometry. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2011 Dec;4( 6):711–711. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.957829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Siuti N, Kelleher NL. Decoding protein modifications using top-down mass spectrometry. Nat Methods. 2007 Oct;4(10):817–821. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Anderson LC, Karch KR, Ugrin SA, et al. Analyses of histone proteoforms using front-end electron transfer dissociation-enabled orbitrap instruments. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2016:3. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O115.053843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90•.Norris AJ, Whitelegge JP, Faull KF, et al. Analysis of enzyme kinetics using electrospray ionization mass spectrometry and multiple reaction monitoring: fucosyltransferase V. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2001 Apr;40(13):3774–3779. doi: 10.1021/bi010029v. Describes different top-down MS approaches. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kleifeld O, Doucet A, Prudova A, et al. Identifying and quantifying proteolytic events and the natural N terminome by terminal amine isotopic labeling of substrates. Nat Protoc. 2011 Sep;6( 10):1578–1611. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kryza T, Silva ML, Loessner D, et al. The kallikrein-related peptidase family: dysregulation and functions during cancer progression. Biochimie. 2016;122:283–299. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fuhrman-Luck RA, Stansfield SH, Stephens CR, et al. Prostate cancer-associated kallikrein-related peptidase 4 activates Matrix Metalloproteinase-1 and Thrombospondin-1. J Proteome Res. 2016 Aug;15(8):2466–2478. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b01148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.McLafferty FW, Breuker K, Jin M, et al. Top-down MS, a powerful complement to the high capabilities of proteolysis proteomics. Febs J. 2007 Dec;274(24):6256–6268. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]