Abstract

Immunodysregulation, Polyendocrinopathy, Enteropathy, X-linked (IPEX) syndrome is a rare, X-linked recessive disease that affects regulatory T cells (Tregs) resulting in diarrhea, enteropathy, eczema, and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. IPEX syndrome is caused by pathogenic alterations in FOXP3 located at Xp11.23. FOXP3 encodes a transcription factor that interacts with several partners, including NFAT and NF-κB, and is necessary for the proper cellular differentiation of Tregs. Although variable, the vast majority of IPEX syndrome patients have onset of disease during infancy with severe enteropathy. Only five families with prenatal presentation of IPEX syndrome have been reported. Here, we present two additional prenatal onset cases with novel inherited frameshift pathogenic variants in FOXP3 that generate premature stop codons. Ultrasound findings in the first patient identified echogenic bowel, echogenic debris, scalp edema, and hydrops. In the second patient, ultrasound findings included polyhydramnios with echogenic debris, prominent fluid-filled loops of bowel, and echogenic bowel. These cases further broaden the phenotypic spectrum of IPEX syndrome by describing previously unappreciated prenatal ultrasound findings associated with the disease.

INTRODUCTION

Immunodysregulation, Polyendocrinopathy, Enteropathy, X-linked (IPEX) syndrome is a rare, X linked recessive disease of autoimmunity due to the lack of development of T regulatory (Treg) cells that are critical to the development of self-tolerance [Powell et al., 1982; Verbsky and Chatila, 2013;]( OMIM #304790). The phenotype includes diarrhea, enteropathy, eczema, and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, typically presenting in the first year of life [Barzaghi et al., 2012)]. The skin findings in IPEX syndrome include atopic dermatitis and psoriasiform lesions. Frequently, elevated levels of IgE can be associated with skin desquamation over the limbs [Halabi-Tawil et al., 2009]. The limited number of reports of IPEX syndrome indicates that the disease is rare, and there is no estimated rate of incidence. Infants with IPEX syndrome lack CD4+/CD25+ Treg cells in the blood and tissues and female carriers display a skewed X inactivation in CD4+/CD25+ cells [Tommasini et al., 2002; Di Nunzio et al., 2009].

IPEX syndrome is caused by pathogenic alterations in FOXP3, which encodes a transcription factor expressed in Tregs and is involved in the regulation of over 800 targets [Katoh et al., 2011]. Through partnership with a large repertoire of transcription factors including NFAT and NF-κB, FOXP3 drives the development of Tregs by upregulating cell surface proteins CD25, CTLA-4, CD103, and GITR while simultaneously downregulating the autoimmune cytokines IL-2, IFN-γ, and IL-4 [Fontenot et al., 2003; Hori et al., 2003; Khattri et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2006; Bettelli et al., 2005; Ramsdell and Ziegler, 2014]. Patients with pathogenic alterations in FOXP3 fail to generate Tregs, and due to the Tregs’ central role in self-tolerance, this results in severe autoimmunity [Bettelli et al., 2005].

IPEX syndrome is a rare disorder reported in over 150 individuals, with 50 pathogenic alterations in FOXP3 and no clear genotype-phenotype correlation [d’Hennezel et al., 2012]. Although heterogeneous, the majority of IPEX syndrome patients have onset of disease in infancy [d’Hennezel et al., 2012; Barzaghi et al., 2012; Baris et al., 2014]. Recently, five families were described with fetuses with IPEX syndrome; prenatal clinical findings included hydrops, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), and prematurity [Reichert et al., 2015; Xavier-da-Silva et al., 2015; Rae et al., 2015; Vasiljevic et al., 2015]. Here, we present two novel inherited frameshift mutations in FOXP3 that introduce premature stop codons and cause fetal forms of IPEX syndrome. Both affected male fetuses presented with in utero desquamation of the skin and prominent echogenic loops of bowel detected by ultrasound. These cases broaden the disease spectrum of IPEX syndrome in the prenatal setting, with important implications for early detection.

CLINICAL REPORT

Patient 1

The mother was a 31-year-old gravida 3, para 1, abortus 1 female referred to Maternal-Fetal Medicine (MFM) at 19 and 6/7 weeks gestation for evaluation of echogenic bowel found on a standard obstetrical ultrasound at her primary obstetrician’s office. A detailed anatomy scan at the MFM office revealed no findings of echogenic bowel, no other abnormalities, and normal biometric parameters. A follow up targeted scan at 23 weeks gestation, revealed mildly prominent bowel loops and skin projections on the face, shoulders, arms and neck, as demonstrated on 3D rendering (Figure 1A). Premature rupture of membranes and vaginal bleeding occurred at 25 weeks gestation. A targeted ultrasound revealed low amniotic fluid with echogenic debris, scalp edema, and echogenic debris in the stomach. At 27 weeks gestation, ongoing sloughing and thickening of the skin was noted (Figure 1 B). Additionally, mild ascites and pleural effusions were identified by targeted ultrasound. The prenatal genetics team at the Greenwood Genetic Center was consulted, and the diagnoses of epidermolysis bullosa and ichthyosis were considered based on the ultrasound findings of echogenic amniotic fluid and fetal skin desquamation. Soon after, the fetus was noted to be hydropic on ultrasound, and the patient delivered via repeat low transverse cesarean section at 27 weeks 2 days. Apgar scores were 2 at one minute and 1 at five minutes. At birth, the skin was partially sloughed with underlying erythema, but the remaining epidermis appeared to be tight and shiny. Resuscitation was attempted but intubation was not successful. The infant died after one hour.

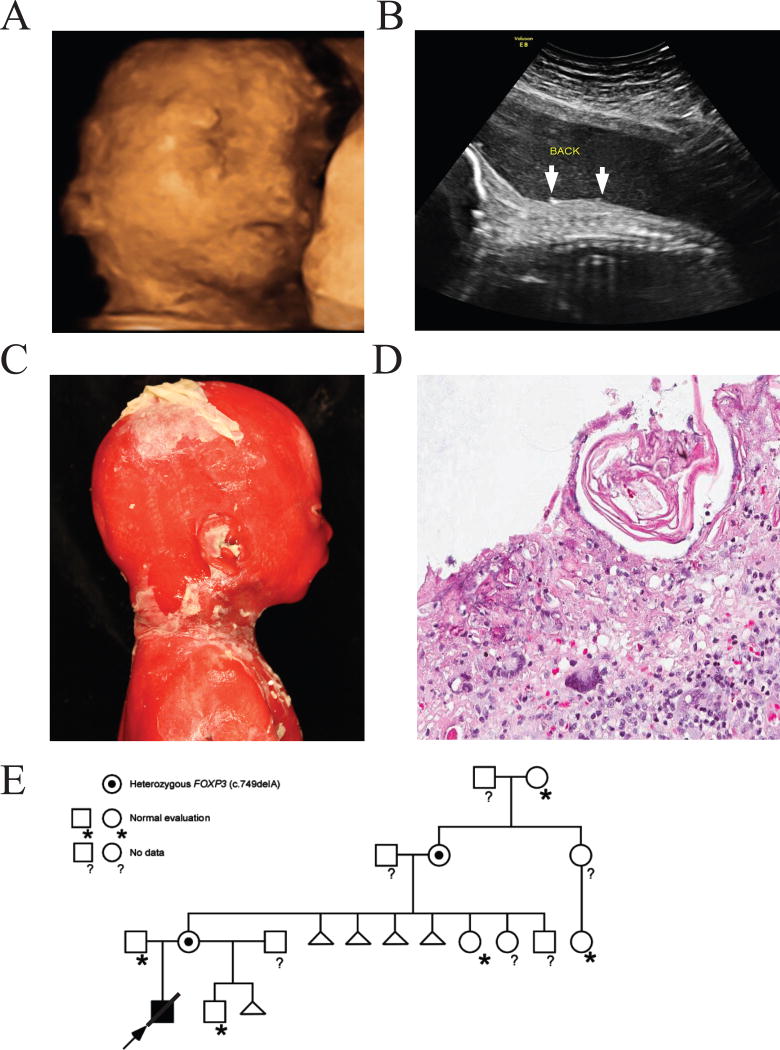

Figure 1.

Outpouching of skin detected by prenatal ultrasound in patient 1. A) 3D image of the face of the fetus at 23 weeks gestation. Several outpouches are identified. B) 2D sagittal image of the fetus at 26 weeks gestation. Skin peeling is identified by arrows. C) Infant pathology images show that the skin was partially sloughed with underlying erythema but the remaining epidermis appeared to be tight and shiny. D) Skin biopsy specimen (hematoxylin-eosin, 50X magnification). The epidermis is mostly absent or necrotic. The milia are represented by the pink cells, and a mixed inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis is present, including a few inflammatory giant cells. E) The pathogenic alteration in FOXP3 (c.749delA) was present in the proband in the hemizygous state. Targeted analysis of family members revealed that this alteration was maternally inherited and appears de novo in the maternal grandmother.

On postmortem examination, the 27-week male infant weighed 904 g (60th centile), crown-rump length was 22.9 cm (25th centile), and crown-heel length was 33.4 cm (40th centile). There was extensive desquamation of skin over the entire body leaving erythematous and pale areas of residual skin (Figure 1C). Exfoliative erythroderma involved most of the skin surface. No intact bullae were present. The palpebral fissures appeared small, and hypertelorism was noted. Clinodactyly of the fifth finger was present. The upper gastrointestinal system and trachea contained debris, but were patent. No meconium was present. The heart, liver, spleen, and kidneys were enlarged (1.5, 2.5, 6.3, and 2.1 times expected weights, respectively), likely secondary to edema. External morphologic and radiographic measurements were consistent with the gestational age.

Histological examination of the skin showed epidermal necrosis, milia and dermal infiltration of lymphocytes, histiocytes, eosinophils, and multinucleated giant cells (Figure 1D).

The family history included a healthy maternal half-brother, and a pregnancy loss with a different maternal partner. The maternal grandmother had a history of 4 pregnancy losses, two occurred in the second trimester (Figure 1 E). The two second trimester losses were both males, but no anomalies were noted, and no specific etiology for the recurrent losses was identified.

Patient 2

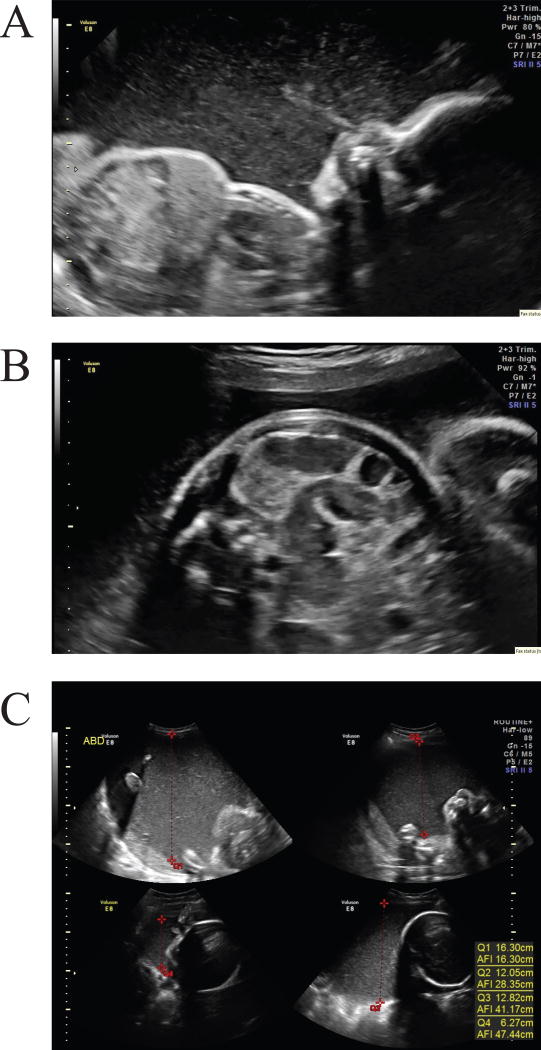

The mother was a 20-year-old gravida 1, para 0 female who presented late to prenatal care at 26 weeks gestation. Detailed anatomic obstetrical ultrasound was notable for echogenic amniotic fluid with particulate appearance and sediment layering, as well as echogenic debris in the stomach (Figure 2A-2C). Subsequent targeted scans showed prominent fluid filled loops of bowel without distention (Figure 2B). Polyhydramnios, initially detected during targeted scan at 29 weeks gestation, worsened as the pregnancy progressed (Figure 2C), and the mother ultimately presented to the hospital with contractions at 34 weeks. Amnioreduction (for Amniotic Fluid Index >40 cm and maternal comfort) was performed, yielding cloudy dark yellow amniotic fluid with significant particulate matter. Fetal lung maturity was predicted by lamellar body count, therefore labor was augmented.

Figure 2.

Prenatal ultrasounds reveal desquamation in patient 2. A) A sagittal profile view of the fetus at 32 weeks. Dense echogenic amniotic fluid is identified. A hyperechoic jet of particulate material is pushed from the fetal nose with fetal breathing motion. B) A transverse view of the fetal abdomen at 32 weeks demonstrates prominent loops of bowel with echogenic debris in the lumen. On real-time images, peristalsis with transit of particulate material within the bowel was observed. C) Fluid index measurement at 34 weeks shows the volume and hyperechoic nature of the amniotic fluid. This fetus had marked polyhydramnios in the third trimester.

The infant was born at 35 weeks gestation. His birth weight (1.74 kg) was at the 11th percentile for his gestational age. Apgar scores were 5 at one minute, 6 at five minutes, and 7 at ten minutes. He required positive pressure ventilation and supplemental oxygen for approximately one minute for apnea. During neonatal resuscitation, 20–30 mL of yellowish-greenish thick liquid poured out from his anus, and 10–15 mL of thick yellow secretions were withdrawn from his stomach. Debris that resembled skin was found in the stool and in his mouth. He was otherwise stable and was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit. His skin was pale, grey, and dry with mild desquamation and ecchymoses on the lower limbs. Dermatology determined that his hyperpigmentation was consistent with dermal melanosis and recommended moisturizers for mild skin desquamation.

After birth, he had frequent loose, green and mucousy stools, up to seven or eight times a day, while on maternal breast milk. At one week, his weight had decreased 18% from birth weight. Enteral feeds were discontinued and total parenteral nutrition was started. He then became hyperglycemic requiring insulin. Hyperglycemia persisted despite a low glucose infusion rate. He was eventually diagnosed with neonatal autoimmune diabetes mellitus. His kidneys were noted to be small on ultrasound, but renal function was normal. Immunoglobulin analysis revealed markedly elevated IgE (2710 IU/mL; reference <13 IU/mL) and normal levels of IgA (33 mg/dL, reference 7–37 mg/dL). Given the constellation of diarrhea (enteropathy), failure to thrive, diabetes mellitus, and prenatal skin sloughing, and elevations in IgE, the diagnosis of IPEX syndrome was considered.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical Assessment/ Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained if indicated, in accordance with Institutional Review Board policies in place for the Greenwood Genetic Center and Duke University School of Medicine.

Patient 1

DNA Preparation

Standard laboratory methods were used for DNA preparation. Karyotype, chromosomal microarray, whole exome sequencing, and Sanger sequencing were performed by the Cytogenetic and Molecular Diagnostic Laboratories at the Greenwood Genetic Center.

Karyotype and SNP microarray

Standard laboratory methods were used for karyotype and chromosomal microarray analyses (Cytoscan HD®, Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) performed on cord blood.

Whole Exome Sequencing and analysis

DNA libraries were prepared from 3 µg of genomic DNA isolated from the patient and parental samples, using the Agilent SureSelectXT Human All Exon v5 capture kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Sequences were processed using NextGENe software (SoftGenetics, LLC, State College, PA) and .vcf files were uploaded to BENCH lab NGS (Cartagenia, Leuven, Belgium) for filtering and subsequent analysis of variants of interest as previously described [Lindy et al., 2014]. Benign variants were separated using the dbSNP, 1000 Genomes, and ESP6500 databases with an allele frequency cut off of 0.033. A phenotype filter was applied using the HPO phenotype term, “Generalized Abnormality of the Skin”, which resulted in 56 variants including one in FOXP3 which was the gene of most interest. Sanger sequencing of exon 8 of FOXP3 (NM_014009.3) was performed under standard PCR conditions to confirm the NGS findings.

Patient 2

DNA sequencing

Next generation sequencing of FOXP3 was performed commercially by the University of Chicago Genetic Services Laboratory, using Agilent SureSelect system for DNA capture and Illumina technology for sequencing. Pathogenic variants identified were confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

FOXP3 flow cytometry

Intracellular FOXP3 flow cytometry was performed commercially by the Diagnostic Immunology lab at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, using PCH101 antibody which reacts with the amino terminus of FOXP3. The assay uses flow cytometry on peripheral blood to quantify FOXP3 levels in CD4 positive T cells that are CD25 bright and CD127 negative.

SNP microarray

Chromosomal microarray was performed commercially by Duke Clinical Cytogenetics laboratory using the Affymetrix Cytoscan HD® array, which consists of nearly 2.7 million genetic markers encompassing 743,304 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) probes as well as 1,953,246 nonpolymorphic copy number variation (CNV) probes.

RESULTS

Patient 1

Karyotype analysis (650–850 band level) and Affymetrix CytoScan HD® microarray (2.67 million probes) performed on cord blood were normal. Whole exome sequencing and trio analysis identified 56 variants in genes associated with abnormalities of the skin, and only one was X-linked. A hemizygous single nucleotide deletion in FOXP3 (c.749delA) was identified to be inherited maternally. This alteration in exon 8 is predicted to cause a shift in the reading frame (p. Lys250Argfs*4). This variant was not observed in the public SNP or mutation databases and was classified as likely pathogenic due to the generation of an aberrant protein and/or nonsense-mediated decay.

Additional family testing revealed that the maternal grandmother, who had four pregnancy losses of which at least two were male, is a carrier of the FOXP3 mutation, which is likely de novo in her (Figure 1E). The maternally related unaffected males did not carry the FOXP3 variant. Therefore, the inherited frameshift alteration in FOXP3 is believed to be causative of the prenatal presentation of IPEX in this patient. The family received genetic counseling for IPEX syndrome.

Patient 2

Karyotype performed from amniocytes and cord blood was normal male (46,XY). SNP microarray performed on cord blood showed an abnormal male result with duplication of at least 597kb of DNA from 16p11.2, which was maternally inherited. This duplication is unrelated to IPEX and confers a predisposition for developmental delay/autism [Rosenfeld et al., 2010]. Sequencing of FOXP3 identified a pathogenic hemizygous one base pair deletion in exon 7 (c.727delG), which results in a frameshift and generation of a premature stop codon (p.Glu243Serfs*11). Targeted analysis of the patient’s mother revealed that this alteration was inherited maternally. Maternal family history did not show a history of recurrent pregnancy loss. Paternal family history is not known, and additional family members were unavailable for testing. Flow cytometry on peripheral blood revealed decreased Treg cells (1.4% of CD4 cells (reference: 4.2–9.9%) or 13 cells/mcL (ref: 43–782) and reduced FOXP3 immuno-staining in these Treg cells (13% positive (ref: 55–81%) or 2 cells/mcL (ref: 28–507), confirming the diagnosis of IPEX syndrome.

The patient was started on tacrolimus, given the severity of his symptoms. His skin, initially leathery, became drier, consistent with eczema. He was started on methylprednisolone, given his persistent diarrhea and difficulty gaining weight. With the clinical and molecular diagnosis of IPEX syndrome, he underwent unrelated cord blood transplantation at age 3 months, and then again at 6 months due to engraftment failure of the first transplantation. Currently, the patient is clinically stable but requires a gastrostomy tube for feeding and pancrelipase for fat malabsorption. Additionally, he continues on insulin for diabetes. He was diagnosed with Hashimoto thyroiditis at age 15 months.

Given the 16p11.2 duplication found on microarray, his development was closely monitored. He had gross developmental delay and at age 2 years was unable to walk independently, and had no words. It is likely that his prolonged hospitalization also contributed to his delays. The family did not report a history of developmental delay, autism, or recurrent miscarriage. The family received genetic counseling for IPEX syndrome and the 16p11.2 duplication, including recurrence risks and phenotypic presentations.

DISCUSSION

FOXP3, in partnership with NFAT and NF-κB, controls the expression of over 800 genes [Katoh et al., 2011] and is necessary and sufficient for the development of Tregs [Hori et al., 2003]. The exact repertoire and timing of the genes expressed under the developmental control of FOXP3 are still being dissected. However, recent reports have shown that FOXP3 upregulates cell surface markers CD25, CTLA-4, CD103, and GITR while simultaneously downregulating the cytokines IL-2, IFN-γ, and IL-4 thereby preventing autoimmunity [Fontenot et al., 2003; Hori et al., 2003; Khattri et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2006; Bettelli et al., 2005]. Currently, treatment of IPEX includes bone hematopoetic stem cell transplantation or immune suppression with cyclosporin A or FK506.

FOXP3 is composed of four domains: repression, zinc finger, leucine zipper, and FKH domains. The FKH domain is required for proper nuclear localization [Lopes et al., 2006] and interfaces with the NFAT and NF-κB transcription factors [Bettelli et al., 2005; Lopes et al., 2006]. Truncation of the FKH domain causes cytoplasmic localization of FOXP3 and reduced transcriptional activity [Lopes et al., 2006]. The majority of disease-causing alterations occur in the FKH domain, highlighting the importance of intracellular localization [Lopes et al., 2006; Verbsky and Chatila, 2013]. Phenotypic severity of IPEX syndrome has been hypothesized to correlate with the extent of residual protein function [Barzaghi et al., 2012], and typically point mutations or small in-frame deletions that do not alter functional protein domains are associated with less severe phenotypes [d’Hennezel et al., 2012]. However, functional studies of disease-causing alterations are required to fully define a genotype-phenotype correlation. The first patient described herein has an inherited frameshift alteration introducing a premature stop codon in exon 8, and the second patient has a frameshift alteration resulting in a stop codon in exon 7. Both variants are located in the leucine zipper domain upstream of the FKH domain, and their protein products are predicted to be missing the FKH domain, given the premature stop codons. However, further functional analyses are required to determine if the transcripts are degraded by the nonsense mediated decay machinery. Flow cytometry results in patient 2 showed decreased numbers of Treg cells, and decreased FOXP3 immuno-staining in these cells is consistent with a loss of functional FOXP3. The majority of previously reported pathogenic mutations have been missense, not causing frameshift or a truncated protein product. In reviewing the prior reports with prenatal presentations of IPEX (Table I), we note that the majority of these mutations disrupt the FKH domain [Xavier-da-Silva et al., 2015; Vasiljevic et al., 2015] or abolish its expression [Rae et al., 2015; Reichert et al., 2015]. In light of our findings and in line with these prior reports, disruption or absence of the FKH domain could explain the early onset of IPEX symptoms, given the importance of this domain for the function of FOXP3.

Table I.

Summary of prenatal ultrasound manifestations of IPEX syndrome in 7 families

| Source | Pathogenic alteration |

Skin desquamation |

Echogenic bowel |

Hydrops | IUGR | Fetal akinesia |

Family history of pregnancy losses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This study | c.749delA p.Glu243Serfs*11 | + | + | + | - | - | + |

| This study | c.727delG p.Lys250Argfs*4 | + | + | - | - | - | - |

| Vasiljevic et al. 2016 | c.1033C>T p.Leu345Phe | - | + | + | + | - | + |

| Xavier-da-Silva et al. 2015 | c.319_32delTC p.Ser107Asnfs*204 | - | - | + | - | - | + |

| Xavier-da-Silva et al. 2015 | c.1189C>T p.R397W | - | - | + | + | - | + |

| Reichert et al. 2015 | c.1009C>T p.R337X | - | - | + | - | - | + |

| Rae et al. 2015 | c.1009C>T p.R337X | - | - | + | - | + | + |

Most cases of IPEX are identified in infancy due to severe enteropathy presenting as intractable diarrhea requiring intravenous fluid replacement. Many of these infants have dermatitis, usually described as eczema. Recent reports described the prenatal presentations of IPEX with prematurity, IUGR, hydrops, and akinesia [Reichert et al., 2015; Xavier-da-Silva et al., 2015; Rae et al., 2015; Vasiljevic et al., 2015]. This report further expands the prenatal phenotype to include generalized exfoliative dermatitis in late second trimester and prominent bowel (Table I).

Echogenic bowel is a relatively nonspecific finding, identified in up to 1.8% of routine second trimester ultrasound exams. Differential diagnosis considered with fetal echogenic bowel is very broad, including intra-amniotic bleeding, fetal cystic fibrosis, fetal aneuploidy (e.g. trisomy 21, 13, 18), congenital infection (e.g. infections due to cytomegalovirus, other viruses, or toxoplasmosis), and primary gastrointestinal pathology (e.g. obstruction, atresia, perforation). Fetal skin desquamation may be suspected based on a constellation of findings, many of which become evident later in gestation than a typical anatomic survey. While rare, the main fetal desquamating disorders for which antenatal ultrasound evidence has been reported are epidermolysis bullosa, ichthyotic disorders, and IPEX. Associated sonographic signs of these diseases that do not necessarily relate to the skin, but have been reported in IPEX, epidermolysis bullosa, and/or ichthyosis include polyhydramnios, dilated or echogenic bowel (with or without pyloric atresia), abnormal extremities (including arthrogryposis), akinesia, fetal growth restriction, and separation of the chorionic and amniotic membranes. The difficulty of antenatal diagnosis of genodermatoses is that the diagnostic criteria for individual diseases are not well characterized from the standpoint of sonographic findings. Each of the above listed sonographic findings generates a broad differential, so clinicians must keep a high index of suspicion for fetal desquamation disorders as nonspecific evidence accumulates in any individual case. In view of this, suggestive intrauterine findings noted on ultrasound may warrant consideration of IPEX syndrome on the differential diagnosis, and testing if appropriate. About 90% of patients with IPEX syndrome do not have clinical features at birth, although there may be a family history of multiple spontaneous abortions [Reichert et al., 2015; Barzaghi et al., 2012].

Previous studies of the skin lesions in patients with IPEX syndrome show a graft-vs-host disease-like pattern with immune cell infiltration and other findings including dermatitis, bullae, urticaria, and alopecia universalis [Wildin et al., 2002; Halabi-Tawil et al., 2009; Nieves et al., 2004; Patey-Mariaud de Serre et al., 2009]. Thus, the histologic skin findings in this infant with a perinatal lethal form of IPEX syndrome are consistent with its postnatal presentation. The two patients in this report, as well as recent reports of prenatal findings of IPEX syndrome, suggest that the cascade of autoimmune destruction may originate in utero, even though the immune system is not fully developed. Tregs have traditionally been thought to be important in peripheral tolerance, requiring self or non-self antigens for the development of autoimmunity [Ramsdell and Ziegler, 2014]. The role of Treg cells in fetal tolerance is an emerging concept as maternal Tregs play a critical role in fetal implantation and maternal tolerance during pregnancy [La Rocca et al., 2014]. Furthermore, fetal Treg cells develop at the end of the first trimester and continue to expand their role in fetal self- tolerance through the second and third trimester [Mold and McCune, 2012]. The onset of symptoms in the fetus point to the role thymus-derived Tregs may perform in early central tolerance, as recently proposed [Ramsdell and Ziegler, 2014] . Alternatively, FOXP3 may have roles that have yet to be elucidated in other fetal cell types (besides lymphocytes) mediating organ damage.

References

- Baris S, Schulze I, Ozen A, Aydiner EK, Altuncu E, Karasu GT, Ozturk N, Lorenz M, Schwarz K, Vraetz T, Ehl S, Barlan IB. Clinical heterogeneity of immunodysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked: pulmonary involvement as a non-classical disease manifestation. J. Clin. Immunol. 2014;34:601–606. doi: 10.1007/s10875-014-0059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzaghi F, Passerini L, Bacchetta R. Immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, x-linked syndrome: a paradigm of immunodeficiency with autoimmunity. Front. Immunol. 2012;3:211. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettelli E, Dastrange M, Oukka M. Foxp3 interacts with nuclear factor of activated T cells and NF-kappa B to repress cytokine gene expression and effector functions of T helper cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:5138–5143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501675102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Nunzio S, Cecconi M, Passerini L, McMurchy AN, Baron U, Turbachova I, Vignola S, Valencic E, Tommasini A, Junker A, Cazzola G, Olek S, Levings MK, Perroni L, Roncarolo MG, Bacchetta R. Wild-type FOXP3 is selectively active in CD4+CD25(hi) regulatory T cells of healthy female carriers of different FOXP3 mutations. Blood. 2009;114:4138–4141. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-214593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4:330–336. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halabi-Tawil M, Ruemmele FM, Fraitag S, Rieux-Laucat F, Neven B, Brousse N, De Prost Y, Fischer A, Goulet O, Bodemer C. Cutaneous manifestations of immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked (IPEX) syndrome. Br. J. Dermatol. 2009;160:645–651. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Hennezel E, Bin Dhuban K, Torgerson T, Piccirillo CA, Piccirillo C. The immunogenetics of immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X linked (IPEX) syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 2012;49:291–302. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-100759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299:1057–1061. doi: 10.1126/science.1079490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh H, Qin ZS, Liu R, Wang L, Li W, Li X, Wu L, Du Z, Lyons R, Liu C-G, Liu X, Dou Y, Zheng P, Liu Y. FOXP3 orchestrates H4K16 acetylation and H3K4 trimethylation for activation of multiple genes by recruiting MOF and causing displacement of PLU-1. Mol. Cell. 2011;44:770–784. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khattri R, Cox T, Yasayko S-A, Ramsdell F. An essential role for Scurfin in CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4:337–342. doi: 10.1038/ni909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rocca C, Carbone F, Longobardi S, Matarese G. The immunology of pregnancy: regulatory T cells control maternal immune tolerance toward the fetus. Immunol. Lett. 2014;162:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindy AS, Bupp CP, McGee SJ, Steed E, Stevenson RE, Basehore MJ, Friez MJ. Truncating mutations in LRP4 lead to a prenatal lethal form of Cenani-Lenz syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2014;164A:2391–2397. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes JE, Torgerson TR, Schubert LA, Anover SD, Ocheltree EL, Ochs HD, Ziegler SF. Analysis of FOXP3 reveals multiple domains required for its function as a transcriptional repressor. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950. 2006;177:3133–3142. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.3133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mold JE, McCune JM. Immunological tolerance during fetal development: from mouse to man. Adv. Immunol. 2012;115:73–111. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394299-9.00003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieves DS, Phipps RP, Pollock SJ, Ochs HD, Zhu Q, Scott GA, Ryan CK, Kobayashi I, Rossi TM, Goldsmith LA. Dermatologic and immunologic findings in the immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome. Arch. Dermatol. 2004;140:466–472. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.4.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patey-Mariaud de Serre N, Canioni D, Ganousse S, Rieux-Laucat F, Goulet O, Ruemmele F, Brousse N. Digestive histopathological presentation of IPEX syndrome. Mod. Pathol. Off. J. U. S. Can. Acad. Pathol. Inc. 2009;22:95–102. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell BR, Buist NR, Stenzel P. An X-linked syndrome of diarrhea, polyendocrinopathy, and fatal infection in infancy. J. Pediatr. 1982;100:731–737. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(82)80573-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rae W, Gao Y, Bunyan D, Holden S, Gilmour K, Patel S, Wellesley D, Williams A. A novel FOXP3 mutation causing fetal akinesia and recurrent male miscarriages. Clin. Immunol. Orlando Fla. 2015;161:284–285. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsdell F, Ziegler SF. FOXP3 and scurfy: how it all began. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014;14:343–349. doi: 10.1038/nri3650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichert SL, McKay EM, Moldenhauer JS. Identification of a novel nonsense mutation in the FOXP3 gene in a fetus with hydrops-Expanding the phenotype of IPEX syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2015 doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld JA, Coppinger J, Bejjani BA, Girirajan S, Eichler EE, Shaffer LG, Ballif BC. Speech delays and behavioral problems are the predominant features in individuals with developmental delays and 16p11.2 microdeletions and microduplications. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2010;2:26–38. doi: 10.1007/s11689-009-9037-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tommasini A, Ferrari S, Moratto D, Badolato R, Boniotto M, Pirulli D, Notarangelo LD, Andolina M. X-chromosome inactivation analysis in a female carrier of FOXP3 mutation. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2002;130:127–130. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01940.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasiljevic A, Poreau B, Bouvier R, Lachaux A, Arnoult C, Fauré J, Cordier MP, Ray PF. Immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome and recurrent intrauterine fetal death. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2015;385:2120. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60773-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbsky JW, Chatila TA. Immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked (IPEX) and IPEX-related disorders: an evolving web of heritable autoimmune diseases. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2013;25:708–714. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildin RS, Smyk-Pearson S, Filipovich AH. Clinical and molecular features of the immunodysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X linked (IPEX) syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 2002;39:537–545. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.8.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Borde M, Heissmeyer V, Feuerer M, Lapan AD, Stroud JC, Bates DL, Guo L, Han A, Ziegler SF, Mathis D, Benoist C, Chen L, Rao A. FOXP3 controls regulatory T cell function through cooperation with NFAT. Cell. 2006;126:375–387. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xavier-da-Silva MM, Moreira-Filho CA, Suzuki E, Patricio F, Coutinho A, Carneiro-Sampaio M. Fetal-onset IPEX: report of two families and review of literature. Clin. Immunol. Orlando Fla. 2015;156:131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]