Abstract

There is often a reciprocal relationship between bone marrow adipocytes and osteoblasts, suggesting that marrow adipose tissue (MAT) antagonizes osteoblast differentiation. MAT is increased in rodents during spaceflight but a causal relationship between MAT and bone loss remains unclear. In the present study, we evaluated the effects of a 14-day spaceflight on bone mass, bone resorption, bone formation, and MAT in lumbar vertebrae of ovariectomized (OVX) rats. Twelve-week-old OVX Fischer 344 rats were randomly assigned to a ground control or flight group. Following flight, histological sections of the second lumbar vertebrae (n=11/group) were stained using a technique that allowed simultaneous quantification of cells and preflight fluorochrome label. Compared with ground controls, rats flown in space had 32% lower cancellous bone area and 306% higher MAT. The increased adiposity was due to an increase in adipocyte number (224%) and size (26%). Mineral apposition rate and osteoblast turnover were unchanged during spaceflight. In contrast, resorption of a preflight fluorochrome and osteoclast-lined bone perimeter were increased (16% and 229%, respectively). The present findings indicate that cancellous bone loss in rat lumbar vertebrae during spaceflight is accompanied by increased bone resorption and MAT but no change in bone formation. These findings do not support the hypothesis that increased MAT during spaceflight reduces osteoblast activity or lifespan. However, in the context of ovarian hormone deficiency, bone formation during spaceflight was insufficient to balance increased resorption, indicating defective coupling. The results are therefore consistent with the hypothesis that during spaceflight mesenchymal stem cells are diverted to adipocytes at the expense of forming osteoblasts.

Introduction

The adult skeleton undergoes continuous bone remodeling, a sequential process that involves bone resorption followed by bone formation. Bone mineral density (BMD), a commonly used index of bone mass in adults, is maintained over time when bone formation is efficiently coupled to the prevailing rate of bone resorption. Bone loss occurs when there is an imbalance between bone formation and bone resorption where resorption predominates. Bone loss is a common occurrence among astronauts during long-duration spaceflight. The reduction of BMD is generally associated with an increase in biochemical markers of bone resorption with no change in biochemical markers in bone formation.1–3 These findings suggest that spaceflight results in a defect in the coupling of bone formation to bone resorption.4 The precise mechanism for this is unknown.

Bone marrow adipose tissue (MAT) has generated considerable recent interest as a putative negative regulator of bone formation.5 Fat accumulates in bone marrow during prolonged bed rest,6 a ground-based human model for spaceflight. Although fat accumulation in bone marrow has not been verified in astronauts, an increase in MAT has been observed in rodents following spaceflight.7,8 Adipocytes and osteoblasts are derived from mesenchymal stromal cells. Based primarily on cell culture studies, some investigators have concluded that increased adipocyte differentiation inevitably occurs at the expense of osteoblast differentiation.9–11 If correct, then the increase in bone marrow adiposity during spaceflight may reflect a shift in the differentiation program of stromal cells from osteoblasts to adipocytes. This may prevent normal coupling of bone formation to the prevailing level of bone resorption and thus have a causative role in the negative bone remodeling balance. The anticipated consequence of this mechanism is reduced generation of osteoblasts.

There is an alternative, non-mutually exclusive mechanism by which increased MAT can negatively influence bone metabolism. More than 50 adipocyte-derived adipokines, growth factors, and proinflammatory cytokines have been identified, including interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β). IL-1β inhibits bone formation and stimulates bone resorption,12 and mRNA levels for IL-1β were shown to be increased in tibia in rats flown aboard STS-62 (ref. 13). Thus, factors produced in bone marrow during spaceflight could reduce bone formation by (1) slowing the rate of osteoblast appearance onto bone surfaces, (2) increasing the rate of osteoblast disappearance from bone surfaces, or (3) inhibiting osteoblast activity.

One or both mechanisms could perpetuate a cycle where increasing MAT would lead to progressive bone loss during prolonged spaceflight. The present study, using archived vertebrae from rats flown on STS-62, utilized a novel approach to challenge these mechanisms by evaluating the association between bone resorption, MAT accumulation, and osteoblast kinetics in sexually mature ovariectomized (OVX) rats subjected to a 14-day spaceflight.

Results

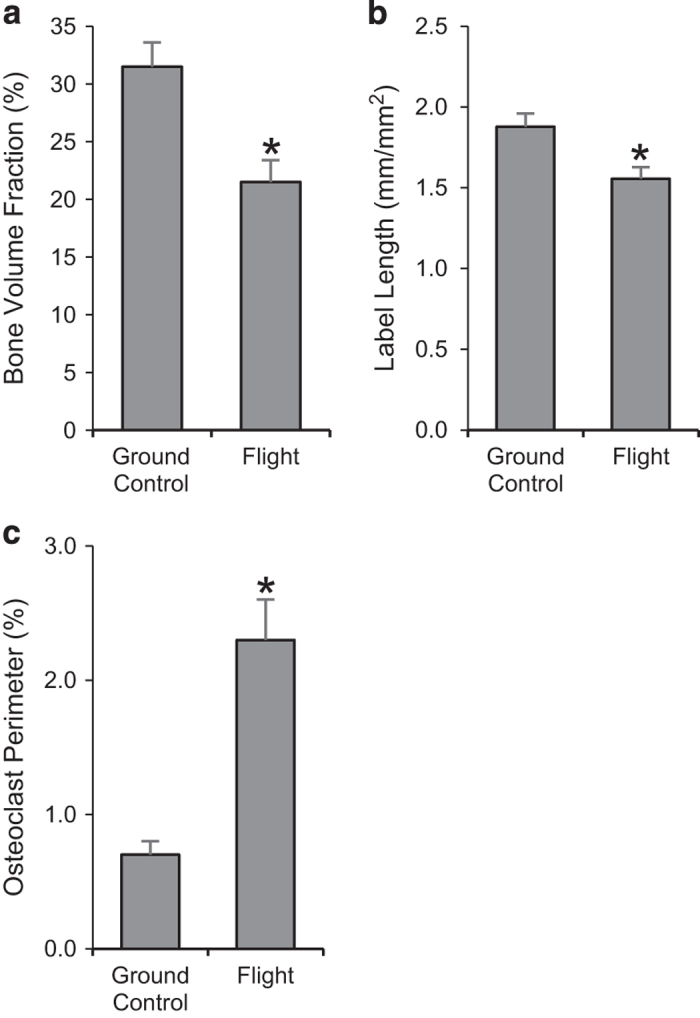

Bone resorption increased during spaceflight

Compared with ground controls, flight animals had 32% lower cancellous bone area fraction (Figure 1a), 16% lower fluorochrome label length (indicative of greater resorption of preflight label; Figure 1b), and 229% greater osteoclast perimeter (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Effects of spaceflight on cancellous bone area fraction (a) and indices of bone resorption including fluorochrome label length/tissue area (b) and osteoclast perimeter (c). Data are mean±s.e., n=11 per group. *Different from ground control, P<0.05.

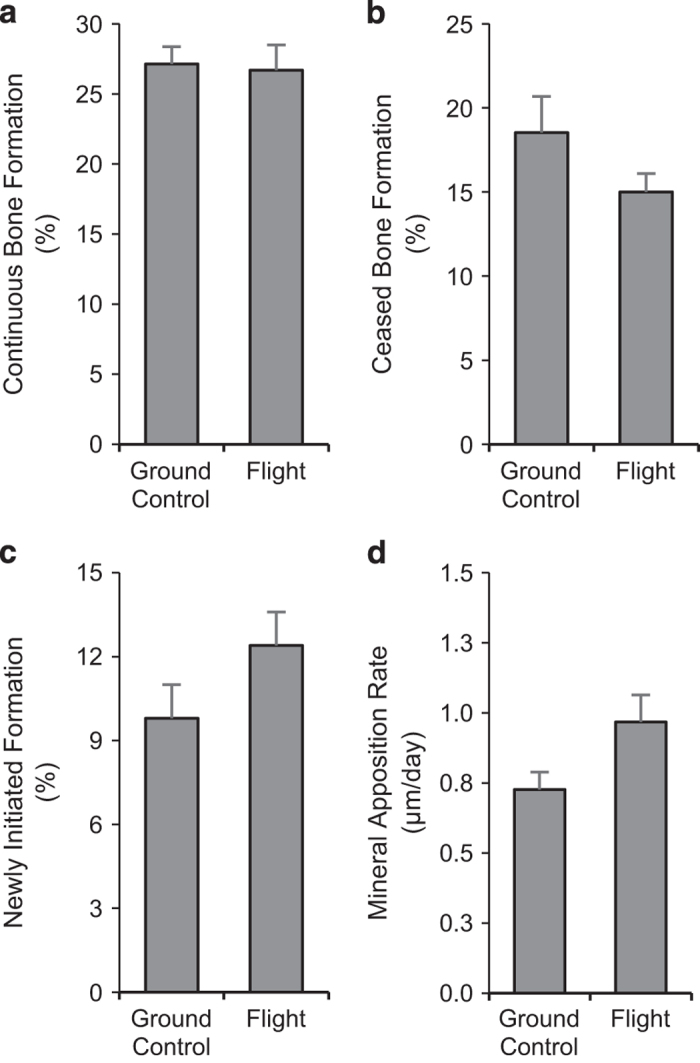

Indices of osteoblast kinetics were not altered during spaceflight

Significant differences between ground control and flight animals were not detected for continuous bone formation (fluorochrome label with adjacent osteoblasts; Figure 2a), ceased bone formation (fluorochrome label with no adjacent osteoblasts; Figure 2b), newly initiated bone formation (osteoblasts with no adjacent fluorochrome label; Figure 2c), or mineral apposition rate (Figure 2d).

Figure 2.

Effects of spaceflight on indices of bone formation including continuous bone formation (a), ceased bone formation (b), newly initiated formation (c), and mineral apposition rate (d). Data are mean±s.e., n=11 per group.

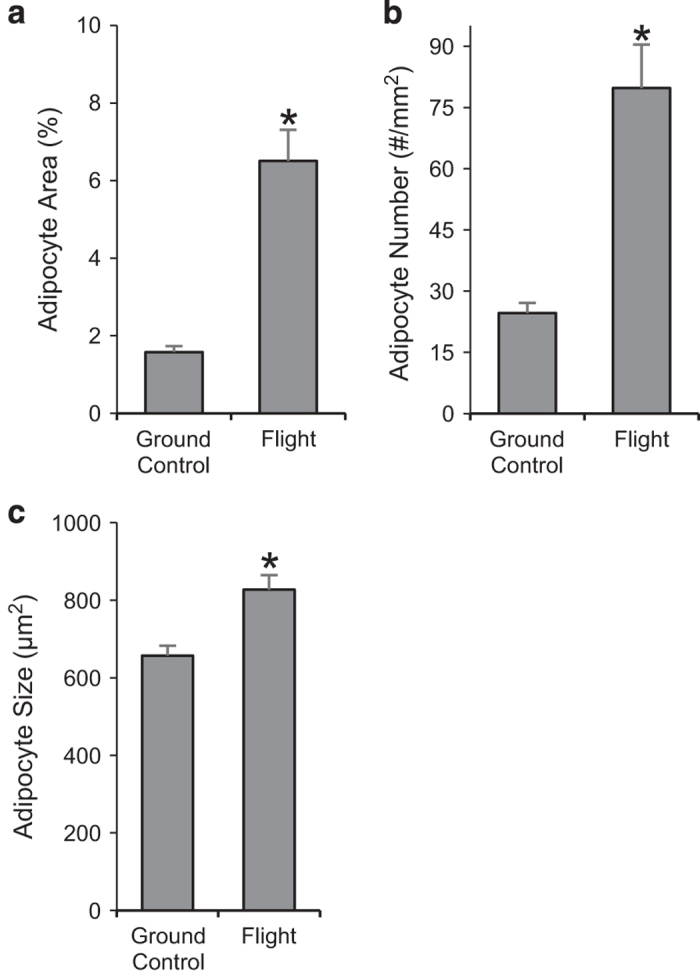

Bone marrow adiposity increased during spaceflight

Percent total tissue area occupied by adipocytes was 306% greater in the flight animals compared with ground controls (Figure 3a). The increase in MAT was associated with increases in adipocyte number (224%; Figure 3b) as well as adipocyte size (26%; Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

Effects of spaceflight on marrow adipose tissue (MAT) area (a), adipocyte number (b) and adipocyte size (c). Data are mean±s.e., n=11 per group. *Different from ground control, P<0.05.

Discussion

Fourteen days of spaceflight resulted in reduced cancellous bone in the lumbar vertebrae of OVX rats. The bone loss was associated with increased osteoclast-lined bone perimeter and decreased preflight fluorochrome label length. In addition, spaceflight resulted in increased vertebral MAT due to increased adipocyte number and adipocyte size. In contrast, spaceflight had no effect on indices of osteoblast differentiation, turnover, or activity.

Lumbar vertebrae were not available from animals killed on the day of launch. As baseline bone measurements were not obtained, it is possible that the lower cancellous bone in the flight animals was due to reduced accrual of cancellous bone during flight. However, this possibility is remote as it is well established that cancellous bone does not increase following OVX in 3-month-old rats.14 Therefore, the lower cancellous bone in the flight rats likely represents bone loss over and above that due to OVX. This conclusion is further supported by the previously documented reduction in cancellous bone in tibia in the same animals where baseline bones were available for analysis.15

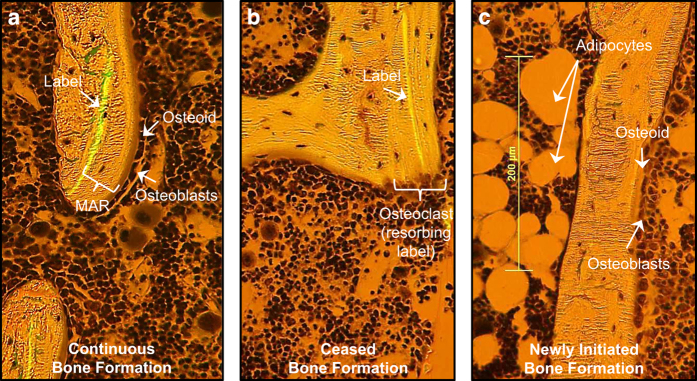

On the basis of the increase in osteoclast perimeter and reduced length of the preflight fluorochrome label, the cancellous bone loss during spaceflight occurred as a consequence of increased bone resorption. OVX rats experience greatly elevated cancellous bone turnover and fluorochrome label resorption as clearly illustrated by the presence of osteoclasts adjacent to the preflight label (Figure 4). Increased resorption of a preflight fluorochrome label during spaceflight was previously reported in tibia in same animals.15 Furthermore, Vico et al.16 reported increased osteoclast numbers in pregnant rats following a 5-day spaceflight. We are unaware of other studies investigating the effects of spaceflight on bone metabolism in female rats.

The effects of spaceflight on MAT have not been studied in detail. Spaceflight was reported to increase MAT in growing male rats but adipocyte number and size were not determined in these studies.7,8,17 In the present study, the increase in MAT was primarily due to an increase in number of adipocytes. We interpret this as evidence that spaceflight results in increased differentiation of progenitor cells to adipocytes. There was, however, an increase in size that contributed to the overall increase in adiposity. This may be relevant because increased adipocyte size is associated with adipocyte dysfunction.18

Spaceflight had no effect on mineral apposition rate, suggesting that the activity of osteoblasts present on bone surfaces at launch was not altered. Spaceflight had no effect on bone perimeter with osteoblasts adjacent to fluorochrome label, suggesting that the interval during which osteoblasts deposit matrix onto bone surfaces was not altered. Last, spaceflight did not alter the extent of bone perimeter lined by osteoblasts with no adjacent label. We interpret this as evidence that spaceflight did not alter the rate of appearance of new osteoblasts onto bone surface. These results are consistent with and extend those of Cavolina et al., where no changes in osteoblast perimeter, bone formation or expression of genes related to osteoblast function were observed following spaceflight.15 In addition, spaceflight increased interferon gamma (IFNγ) expression in tibia in these animals.12 IFNγ is produced by mesenchymal cells as well as innate and adaptive cells in the immune system and has been reported to increase bone formation and inhibit fat infiltration into bone marrow in OVX mice.19 Taken together, these findings indicate that MAT influx during spaceflight does not reduce osteoblast differentiation, activity or lifespan. Potentially, this is due to counter regulatory increases in cytokines that oppose adipogenesis and promote osteoblastogenesis.

OVX typically results in increased turnover of cancellous bone. OVX-induced bone loss is limited to skeletal sites, such as the proximal tibial metaphysis and lumbar vertebra, where the increase in bone formation is inadequate to compensate for the increase in bone resorption.20,21 In contrast, spaceflight resulted in an increase in bone resorption with no increase in bone formation in lumbar vertebra and in proximal tibia metaphysis.15 These findings support the possibility that lineage redirection of stromal cells to adipocytes during spaceflight contributes to defective coupling of bone formation to increased bone resorption.

The effects of spaceflight on cancellous bone turnover may be influenced by endocrine status. Bone turnover in normal female rats has not been evaluated following spaceflight. However, OVX and ovary-intact rats have been evaluated following hindlimb unloading, a ground-based model that replicates some of the skeletal effects of spaceflight.22 Although hindlimb unloading resulted in bone loss in OVX as well as ovary-intact rats, the cellular mechanisms were not identical. Specifically, cancellous bone loss in OVX rats was predominantly due to increased bone resorption, whereas bone loss in ovary-intact rats was due to a combination of increased bone resorption and reduced bone formation.23,24 A reduction in estrogen signaling in the skeleton results in increased bone turnover and cancellous bone loss.25 Reproductive changes during or post flight have not been systematically studied in women, but in female adult mice spaceflight induced cessation of cycling, loss of corpora lutea, and reduced estrogen receptor mRNA levels in the uterus.26

Most spaceflight studies have been performed using growing male rats. Reduced bone formation from decreased osteoblast number and activity has been observed in these animals.8,27–29 Although no spaceflight experiments comparing gender have been conducted, direct comparison of the skeletal response of normal male and female rats approaching skeletal maturity (6 months old) to hindlimb unloading did not detect gender differences.23 Therefore, it seems more likely high cancellous bone turnover rate and/or change in endocrine status induced by OVX modifies how bone cells respond to microgravity. This is in agreement with previous studies reporting that estrogen regulates the rate of bone turnover independent of gravitational loading. The difference in response may be important because endocrine status could influence the efficacy of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions to prevent bone loss during long-duration spaceflight.21

In summary, we conclude that the increase in MAT during short-duration spaceflight does not impair osteoblast activity, reduce the interval osteoblasts are present on bone surfaces or decrease generation of new osteoblasts. These findings argue against the hypothesis that increased MAT produces factors that suppress bone formation. Although increased MAT did not impact osteoblast kinetics or bone formation, it is important to note that bone formation did not increase during spaceflight to compensate for the increase in bone resorption. This finding is consistent with the hypothesis that, in the context of ovarian hormone deficiency, osteoblast precursors are diverted to adipocytes instead of osteoblasts during spaceflight.

Materials and methods

Experimental design

The experimental protocol was approved by the NASA Animal Care and Use Committee, and animals were maintained in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Twelve-week-old female Fischer 344 rats (Taconic Farms, Germantown, NY, USA) were used in the study. The rats were OVX 14 days prior to launch and randomly assigned to one of two treatment groups (n=12 per group): (1) ground-based control (ground control) or (2) spaceflight (flight). The flight animals were flown on the Space Shuttle Columbia (STS-62) for 14 days. All animals were housed in animal enclosure modules (AEM) with 6 rats per AEM. The AEMs were maintained at 28 °C. Food (Teklad L356 food bars; Teklad, Madison, WI, USA) and water were provided ad libitum to all animals. Rats received one calcein injection (20 mg/kg, intraperitoneal) one day prior to launch to label mineralizing bone matrix. The rats were killed by decapitation on the day of landing and bones were collected and placed in 70% ethanol for analysis.

Histomorphometry

Second lumbar vertebrae from 11 rats per group were available for evaluation. The bones were prepared for histological analysis as described.30 In brief, specimens were dehydrated in increased concentrations of ethanol and embedded in a mixture of methyl methacrylate and 2-hydroxyethyl-methacrylate (in a 12.5:1 ratio). Five-micrometer-thin sections were then cut on a microtome (model 2065, Reichert-Jung, Heidelberg, Germany) and stained with toluidine blue (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO, USA). The staining technique allowed simultaneous quantification of cells and fluorochrome label.

The effects of spaceflight on bone resorption and osteoblast turnover (Figure 4) were evaluated using a novel approach. Specifically, the preflight fluorochrome label was used to identify bone perimeter undergoing mineralization in preflight animals experiencing normal weight bearing. Because preflight fluorochrome label perimeter is assumed to be similar in the rats randomly assigned to a group (ground control or flight), post-flight differences in label length represent intergroup differences in bone resorption during flight. In turn, the perimeter bounded by preflight label with adjacent osteoblasts represents continuous bone formation throughout the duration of flight (Figure 4a), whereas fluorochrome label with no adjacent osteoblasts reflects sites undergoing bone mineralization at the time of label administration but not subsequently (ceased bone formation; Figure 4b). In contrast, bone perimeter bounded by osteoblasts with no adjacent label represents sites where bone formation was newly initiated during flight (i.e., following administration of the preflight label; Figure 4c).

Figure 4.

Photomicrographs depicting continuous bone formation (fluorochrome label with adjacent osteoblasts) (a), ceased bone formation (fluorochrome label with no adjacent osteoblasts) (b), and newly initiated bone formation (osteoblasts with no adjacent fluorochrome label) (c). Also shown are the distance between a fluorochrome label and osteoblast-lined perimeter used to calculate mineral apposition rate (MAR) (a), an osteoclast resorbing label (b), and marrow adipocytes (c).

Cell and fluorochrome data were simultaneously collected by viewing the sections under combined visible light and ultraviolet light using the OsteoMeasure System (OsteoMetrics, Atlanta, GA, USA). Endpoints evaluated included bone area fraction (bone area/tissue area, area of total tissue evaluated occupied by cancellous bone, %), fluorochrome label length (length/tissue area, mm/mm2) and osteoclast perimeter (osteoclast perimeter/bone perimeter, %). Fluorochrome-based indices of bone formation included measurements of continuous bone formation during flight (percentage of bone lined with osteoblasts associated with the single label; %), ceased bone formation during flight (percentage of bone perimeter with label not associated with osteoblasts, %), newly initiated bone formation during flight (percentage of osteoblast perimeter not associated with label, %) and mineral apposition rate (mean distance between the fluorochrome marker and osteoblast-lined perimeter divided by number of days between the label injection and killing (15 days), μm/day). MAT (% tissue area) and adipocyte number (#/mm2) were measured and adipocyte size (μm2) was determined by dividing MAT by adipocyte number.

Statistical analysis

Mean responses were compared using independent two-sample t-tests (ground control versus flight). The required conditions for valid use of t-tests were assessed using Levene’s test for homogeneity of variance and the Anderson–Darling test for normality. When the assumption of equal variance was violated, Welch’s two-sample t-test was used for comparisons.31 When the assumption for normality was violated, the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test was performed. The Hochberg adjustment method was used to control for multiple comparisons by maintaining the familywise error rate at 5% (Hochberg 1988). Differences were considered statistically significant at P<0.05. All data are expressed as mean±s.e.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation Research Traineeship Program (DGE-0956280) and a grant from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NNX12AL24G). Grant Sponsors: NASA (NNX12AL24G) and NSF (DGE-0956280).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Orwoll, E. S. et al. Skeletal health in long-duration astronauts: nature, assessment, and management recommendations from the NASA Bone Summit. J. Bone Miner. Res. 28, 1243–1255 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibonga, J. D. Spaceflight-induced bone loss: is there an osteoporosis risk? Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 11, 92–98 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner, R. T. Invited review: what do we know about the effects of spaceflight on bone? J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 89, 840–847 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erben, R. G. Hypothesis: coupling between resorption and formation in cancellous bone remodeling is a mechanically controlled event. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 6, 82 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheller, E. L. & Rosen, C. J. What's the matter with MAT? Marrow adipose tissue, metabolism, and skeletal health. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1311, 14–30 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trudel, G. et al. Bone marrow fat accumulation after 60 days of bed rest persisted 1 year after activities were resumed along with hemopoietic stimulation: the Women International Space Simulation for Exploration study. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 107, 540–548 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wronski, T. J., Morey-Holton, E. & Jee, W. S. Cosmos 1129: spaceflight and bone changes. Physiologist 23, S79–S82 (1980). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jee, W. S., Wronski, T. J., Morey, E. R. & Kimmel, D. B. Effects of spaceflight on trabecular bone in rats. Am. J. Physiol. 244, R310–R314 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma, S., Rajaratnam, J. H., Denton, J., Hoyland, J. A. & Byers, R. J. Adipocytic proportion of bone marrow is inversely related to bone formation in osteoporosis. J. Clin. Pathol. 55, 693–698 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimble, J. M. & Nuttall, M. E. Bone and fat: old questions, new insights. Endocrine 23, 183–188 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smitka, K. & Maresova, D. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ: an update on pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory microenvironment. Prague Med. Rep. 116, 87–111 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conde, J. et al. Basic aspects of adipokines in bone metabolism. Clin. Rev. Bone Miner. Metab. 13, 11–19 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M. & Turner, R. T. The effects of spaceflight on mRNA levels for cytokines in proximal tibia of ovariectomized rats. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 69, 626–629 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wronski, T. J., Dann, L. M. & Horner, S. L. Time course of vertebral osteopenia in ovariectomized rats. Bone 10, 295–301 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavolina, J. M. et al. The effects of orbital spaceflight on bone histomorphometry and messenger ribonucleic acid levels for bone matrix proteins and skeletal signaling peptides in ovariectomized growing rats. Endocrinology 138, 1567–1576 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vico, L. et al. Effects of weightlessness on bone mass and osteoclast number in pregnant rats after a five-day spaceflight (COSMOS 1514). Bone 8, 95–103 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wronski, T. J. & Morey, E. R. Skeletal abnormalities in rats induced by simulated weightlessness. Metab. Bone Dis. Relat. Res. 4, 69–75 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, L. et al. Large adipocytes function as antigen presenting cells to activate CD4+ T cells via up-regulating MHCII in obesity. Int. J. Obes. 40, 112–120 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal, C. et al. Interferon gamma inhibits adipogenesis in vitro and prevents marrow fat infiltration in oophorectomized mice. Stem Cells 30, 1042–1048 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jee, W. S. & Yao, W. Overview: animal models of osteopenia and osteoporosis. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal. Interact. 1, 193–207 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerlind, K. C. et al. Estrogen regulates the rate of bone turnover but bone balance in ovariectomized rats is modulated by prevailing mechanical strain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 94, 4199–4204 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey, E. R., Sabelman, E. E., Turner, R. T. & Baylink, D. J. A new rat model simulating some aspects of space flight. Physiologist 22, S23–S24 (1979). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefferan, T. E. et al. Effect of gender on bone turnover in adult rats during simulated weightlessness. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 95, 1775–1780 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner, R. T., Evans, G. L., Cavolina, J. M., Halloran, B. & Morey-Holton, E. Programmed administration of parathyroid hormone increases bone formation and reduces bone loss in hindlimb-unloaded ovariectomized rats. Endocrinology 139, 4086–4091 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner, R. T., Riggs, B. L. & Spelsberg, T. C. Skeletal effects of estrogen. Endocr. Rev. 15, 275–300 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronca, A. E. et al. Effects of sex and gender on adaptations to space: reproductive health. J. Womens Health (Larchmt) 23, 967–974 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wronski, T. J., Morey-Holton, E. R., Doty, S. B., Maese, A. C. & Walsh, C. C. Histomorphometric analysis of rat skeleton following spaceflight. Am. J. Physiol. 252, R252–R255 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vico, L., Bourrin, S., Genty, C., Palle, S. & Alexandre, C. Histomorphometric analyses of cancellous bone from COSMOS 2044 rats. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 75, 2203–2208 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikle, D. D., Harris, J., Halloran, B. P. & Morey-Holton, E. Altered skeletal pattern of gene expression in response to spaceflight and hindlimb elevation. Am. J. Physiol. 267, E822–E827 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwaniec, U. T., Wronski, T. J. & Turner, R. T. Histological analysis of bone. Methods Mol. Biol. 447, 325–341 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch, B. On the comparison of several mean values: an alternative approach. Biometrika 38, 330–336 (1951). [Google Scholar]