Abstract

Setting: All health facility and community malnutrition screening programmes in Tonkolili, a rural Ebola-affected district in Sierra Leone.

Objectives: Before the Ebola disease outbreak, Sierra Leone had set a goal to reduce the prevalence of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) in children aged <5 years to <0.2%. We compared the number of children screened, diagnosed and treated for malnutrition before, during and after the outbreak (2013–2016).

Design: This was a retrospective cross-sectional study.

Results: Health facility screening declined from 16 805 children per month pre-outbreak to 13 510 during the outbreak (P = 0.02), and returned to pre-outbreak levels after the outbreak. Community-based screening remained stable during the outbreak, and increased by 30% post-outbreak (P < 0.001). The proportion diagnosed with moderate acute malnutrition using mid-upper arm circumference increased from respectively 3.6% and 5.1% pre-outbreak in the community and health facilities to 8.2% and 7.9% post-outbreak (P < 0.001, P = 0.003). The proportion of children diagnosed with SAM using a weight-for-age ratio at health facilities increased from 1.5% pre-outbreak to 3.5% post-outbreak (P = 0.003). On average, for every four children diagnosed with SAM per month, one child completed SAM treatment.

Conclusion: After a decline in screening during the Ebola outbreak, diagnoses of acute malnutrition increased post-outbreak. Nutrition programmes need to be strengthened to pre-empt such effects in the event of future Ebola outbreaks.

Keywords: child, therapeutic feeding, health systems strengthening, operational research, SORT IT

Abstract

Contexte : Tous les programmes de dépistage de la malnutrition par les structures de santé et dans les communautés à Tonkolili, un district rural affecté par Ebola en Sierra Leone.

Objectifs : Avant la flambée épidémique d'Ebola, la Sierra Leone avait fixé l'objectif de réduire la prévalence de la malnutrition aigüe grave (MAG) chez les enfants âgés de <5 ans à < 0,2%. Nous avons comparé le nombre d'enfants dépistés, diagnostiqués et traités pour malnutrition avant, pendant et après la flambée épidémique (2013–2016).

Schéma : Une étude rétrospective transversale.

Résultats : Le dépistage dans les structures de santé a décliné de 16 805 enfants par mois avant Ebola à 13 510 pendant Ebola (P = 0,02), et il est revenu à son niveau d'avant la flambée dans la période post-Ebola. Le dépistage en communauté est resté stable pendant Ebola et a augmenté de 30% post-Ebola (P < 0,001). La proportion d'enfants ayant eu un diagnostic de malnutrition modérée aigüe en fonction du périmètre brachial a augmenté respectivement de 3,6% et de 5,1% avant Ebola en communauté et dans les structures de santé, de 8,2% et de 7,9% après Ebola (P < 0,001 ; P = 0,003). La proportion d'enfants ayant eu un diagnostic de MAG en fonction du poids pour l'âge dans les structures de santé est passée de 1,5% avant Ebola à 3,5% après Ebola (P = 0,003). En moyenne, un enfant a achevé son traitement de MAM sur quatre enfants ayant eu un diagnostic de MAG par mois.

Conclusion : Après un déclin dans le dépistage pendant la flambée épidémique d'Ebola, les diagnostics de malnutrition aigüe ont augmenté après Ebola. Un renforcement des programmes de nutrition est nécessaire pour éviter un tel effet lors de futures flambées épidémiques.

Abstract

Marco de referencia: Todos los programas institucionales y comunitarios de detección de la desnutrición en Tonkolili, un distrito rural de Sierra Leona afectado por el virus del Ébola.

Objetivos: Antes del brote epidémico por el virus del Ébola, Sierra Leona se había fijado el objetivo de disminuir a <0,2% la prevalencia de desnutrición aguda grave (SAM) en los niños <5 años de edad. En el presente estudio se comparó el número de niños que participaron en la detección sistemática de la desnutrición, el número de niños diagnosticados y el de niños tratados por desnutrición antes del brote, durante el mismo y después de él (del 2013 al 2016).

Método: Fue este un estudio transversal retrospectivo.

Resultados: El tamizaje en los establecimientos sanitarios disminuyó de 16 805 niños por mes antes del brote a 13 510 niños por mes durante el mismo (P = 0,02) y la cifra inicial se recuperó después del brote. El tamizaje en la comunidad permaneció estable durante el brote y aumentó un 30% después del mismo (P < 0,001). Al utilizar como medida el perímetro braquial, la proporción de diagnósticos de desnutrición aguda moderada aumentó de 3,6% en la comunidad y 5,1% en los establecimientos antes del brote respectivamente a 8,2% y 7,9% después del mismo (P < 0,001, P = 0,003). Al aplicar los valores del peso para la edad en los establecimientos de salud, la proporción de niños con diagnóstico de SAM pasó del 1,5% antes del brote a 3,5% después del mismo (P = 0,003). En promedio, uno de cada cuatro niños en quienes se diagnosticó SAM cada mes completó su tratamiento.

Conclusión: Después de una diminución de la detección sistemática de la desnutrición aguda grave durante el brote epidémico de enfermedad del Ébola, el diagnóstico de desnutrición aguda aumentó después del brote. Es necesario fortalecer los programas de nutrición con el fin de evitar con anticipación estas repercusiones durante los brotes epidémicos en el futuro.

During 2014 and 2015, West Africa experienced the largest outbreak of Ebola virus disease (EVD) in history.1 In Sierra Leone, at least 13 992 people became infected with EVD, of whom 3955 died.2 The outbreak strained the country's already fragile health system, with consequences for health-care delivery reported across the health sector.3

The national prevalence of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) and moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) is respectively 4.0% and 9.3% using weight-for-height (WFH) ratio and 5.6% and 16.4% using weight-for-age (WFA) ratio,4 and the childhood mortality rate is 156/1000 live births.5 Before the emergence of EVD, addressing malnutrition was a national strategy and a health system priority.4 In 2011, Sierra Leone's Ministry of Health and Sanitation (MoHS) set a target to reduce SAM prevalence to 0.2% by 2016.4 The strategy to reduce malnutrition includes facility-based screening and treatment for all children who present to health facilities, and community-based mobilisation and screening with referral for facility-based treatment as required.4

EVD may have had an impact on the management of malnutrition in Sierra Leone, as has been reported for other services in EVD-affected countries.3,6,7 During the outbreak in Sierra Leone, 221 health workers lost their lives,2 funds for programmes were diverted to the EVD response, and some facilities closed or reduced their services.3 There were reports of community members and health workers being afraid to interact due to perceived risks of infection.8

A Medline literature search found no published data to date on the effects of the EVD outbreak on paediatric nutrition programmes in West Africa. We sought to examine the association between the periods before, during and after the national outbreak of service delivery within the malnutrition management programme in Tonkolili District, Sierra Leone. Our objectives were to estimate and compare 1) the number of children screened for malnutrition, 2) the number and proportion of children diagnosed with MAM and SAM amongst those screened, and 3) the number of children diagnosed with SAM who completed in-hospital and out-patient treatment for SAM, before, during and after the outbreak.

METHODS

Study design

We performed a retrospective cross-sectional study using routinely collected aggregate data on nutritional services for children aged <5 years.

Study setting

Sierra Leone, a low-income country in West Africa, with a population of 7.1 million,9 has some of the worst malnutrition and child mortality indicators in the world.5

In Tonkolili District (population 530 776 in 2015),9 the prevalence of SAM and MAM in 2011 was respectively 1.9% and 5.5% using WFH, and 3.5% and 14.8% using WFA.4 Health care is provided by 107 health facilities (104 peripheral health units [PHU], one private and two government hospitals) and through 964 community health workers (CHWs).10 The EVD outbreak in Tonkolili started on 26 June 2014, and by 1 November 2016, when the national outbreak was declared to be over, there had been 456 documented cases.2 By 1 March 2015, EVD cases in Tonkolili had declined to zero, with sporadic cases reported in August 2015 and in January 2016.11

Malnutrition programme

The nutrition programme of the MoHS includes facility- and community-based screening. In the facility-based programme, all children aged 6–59 months who present to the facility for any reason should be screened for malnutrition. ‘Fixed’ facility-based screening occurs during visits to a PHU or hospital. ‘Outreach’ screening occurs during visits to mobile clinics held in the catchment area of a given PHU. In both settings, children are screened using WFH (or length) ratio, WFA ratio and mid-upper-arm circumference (MUAC).

Community screening includes social mobilisation and sensitisation by the CHWs to the signs and symptoms of malnutrition, along with services available to prevent and treat malnutrition. Households and communities alert the CHW to any child who may be malnourished. The CHW then conducts screening in the household using the MUAC. If the criteria for MAM and SAM are met, the child is referred to the nearest facility for further assessment and treatment.

MAM and SAM are defined as WFH or WFA ratios that are respectively <2 or <3 standard deviations (SD) below the mean on the World Health Organization (WHO) standard growth chart.12 Alternatively, an MUAC of <115 mm with or without medical complications also indicates SAM, while an MUAC of between 115 and 125 mm indicates MAM.12 Children with SAM and medical complications are treated in an in-patient stabilisation treatment programme (STP), while those with SAM but without medical complications are treated in the out-patient treatment programme (OTP), per WHO guidelines.12 The two government hospitals provide in-patient treatment for SAM with medical complications, while 48 of the PHUs provide out-patient treatment for SAM without medical complications.

During the EVD outbreak, facilities with inadequate supplies and training in infection control practices were advised to avoid invasive procedures, including blood work and injectable medications. As CHWs were advised to refrain from touching patients, they provided care givers with MUAC tape measures to screen their children.13

Study population

The study population included all children aged <5 years residing in Tonkolili District who underwent health facility or community screening for malnutrition between 1 June 2013 and 30 April 2016.

Data collection

Each month, aggregate source data from PHUs and hospitals were captured in routine monitoring and evaluation registers, reported to the MoHS and entered into the electronic District Health Information System (DHIS) database. The CHWs also submitted monthly data on the number of children screened, diagnosed with MAM/SAM and referred to health facilities, after first tallying them in a standardised register. Aggregate data for the study were extracted from the DHIS database.

Data variables

We collected the following district-level variables per month and year of the study period: month and year; health service delivery type (community, facility-based fixed, facility-based outreach); method of screening (MUAC, WFH, WFA); number diagnosed with MAM; number diagnosed with SAM; number with SAM admitted for treatment, and number discharged from the STP and OTP following treatment.

Analysis and statistics

Data were double-entered using EpiData v. 3.1 for entry and v. 2.2.2.182 for analysis (EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark). We compared the following time periods: before the national Ebola outbreak (1 June 2013–30 April 2014), during the outbreak (1 June 2014–30 April 2015) and after the outbreak (1 November 2015–30 April 2016). We explored monthly trends and compared outcomes by time periods using the t-test for continuous variables and the χ2 test for proportions. For each outcome, we compared the pre-EVD period with the period during the EVD outbreak, and the pre-EVD period with the post-EVD period. To address potential effects of seasonality, each comparison period included the same calendar months. The pre- vs. post-EVD comparisons were restricted to the months inclusive of November to April in each time period. We imputed a value of zero if SAM discharge data were missing in the DHIS.

Ethics approval

The Sierra Leone National Ethics and Scientific Review Committee (Freetown), the Sierra Leone MoHS (Freetown) and the Ethics Advisory Group of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (Paris, France) approved the study. As aggregate data were used, with no names and no patient identifiers, informed patient consent was not required.

RESULTS

Data were complete for the 28 months of the study with the exception of those for SAM treatment admission and STP discharge. Six of 11 months in the pre-EVD period, 8 of 11 months during EVD and 1 of 6 months post-EVD were missing SAM admission data. Data on SAM treatment discharge from STP were missing for respectively 1, 1 and 2 months of the pre-, during and post-outbreak periods.

Malnutrition screening

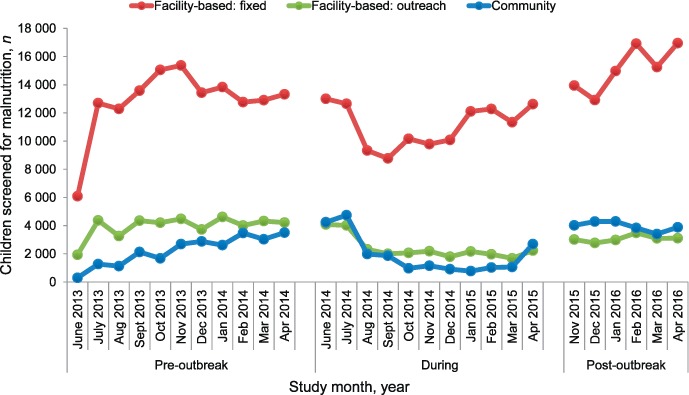

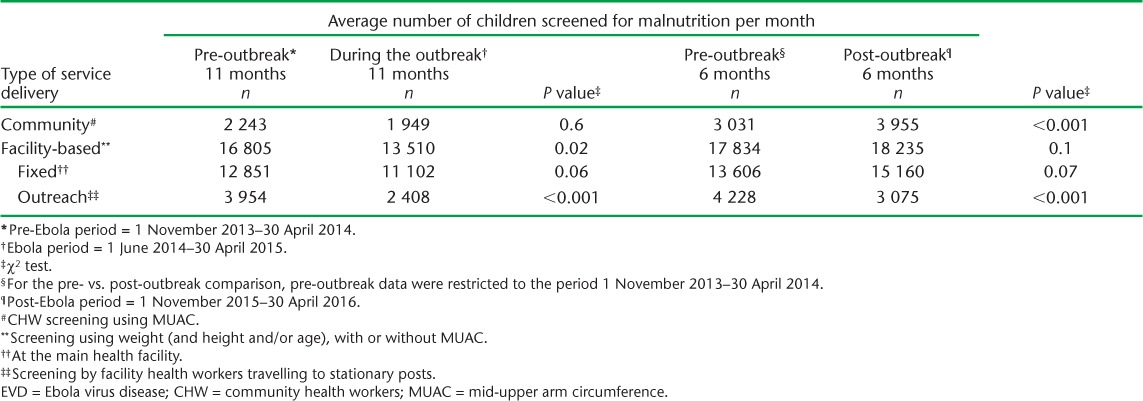

Between 8319 and 24 243 children were screened per month (Figure 1). Most (78–96%) screening was performed in facilities, where the average monthly number of children screened decreased from 16 805 pre-outbreak to 13 510 during EVD (P = 0.02), then returned to pre-outbreak levels (Table 1). The decline in facility-based screening during EVD was driven largely by the outreach sites, where average screening fell by 39% from pre-outbreak levels (P < 0.001), and which had yet to recover at the time of the study (Figure 1, Table 1). Facility-based screening at fixed sites increased after March 2015 (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Number of children screened for malnutrition before, during and after the Ebola outbreak in Tonkolili District, Sierra Leone. Fixed facility-based screening was performed by MUAC or weight-for-age or weight-for-height ratios. Outreach facility-based screening was undertaken by facility-based outreach to stationary posts. Community screening was performed by MUAC. MUAC = mid-upper arm circumference.

TABLE 1.

Number of children screened for malnutrition before, during and after the EVD outbreak, Tonkolili District, Sierra Leone

Based on monthly trends (Figure 1), although community screening declined, the average number of children screened between the pre- and during-outbreak periods remained stable (2243 vs. 1949, P = 0.6). There was an increasing trend in community screening pre-outbreak, which continued until the local outbreak began in Tonkolili, followed by a decline during the rest of the outbreak until March 2015 (Figure 1). Post-outbreak community screening was 23% higher than pre-outbreak levels (P < 0.001, Table 1).

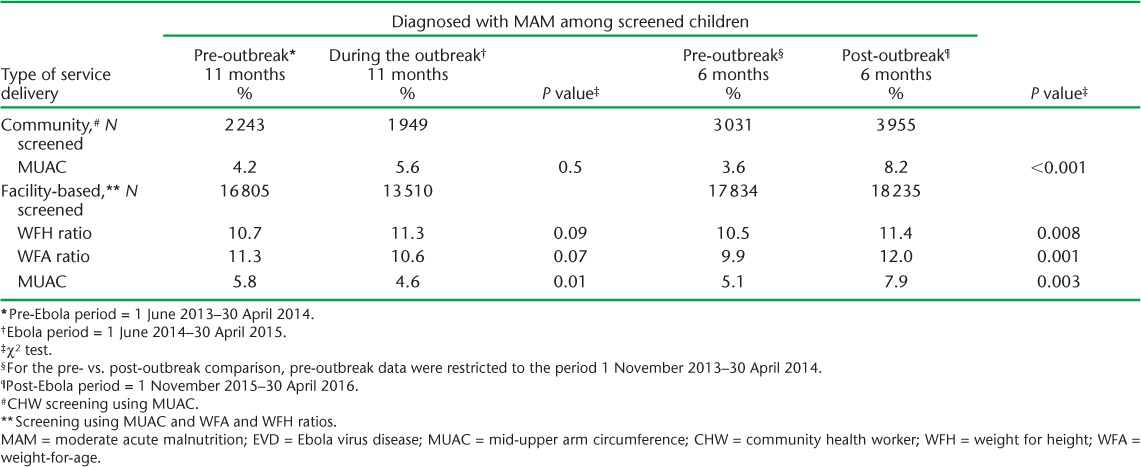

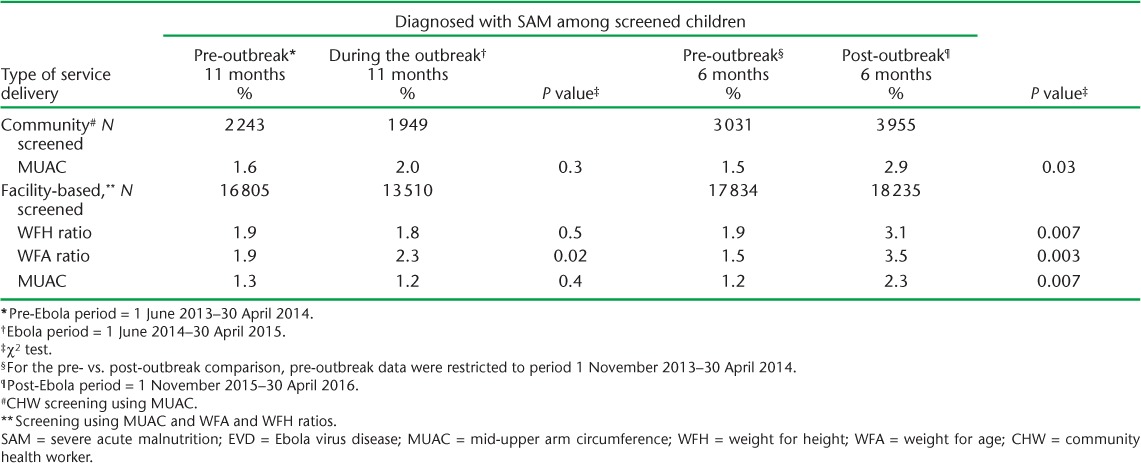

Diagnoses of MAM and SAM

There were inconsistent trends and non-significant differences in the proportion of screened children diagnosed with MAM (Table 2) or SAM (Table 3) during the outbreak compared with pre-outbreak levels. The proportion of screened children diagnosed with MAM by MUAC increased between the pre- and post-outbreak periods in the community (3.6% to 8.2%, P < 0.001) and in the health facilities (5.1% to 7.9%, P = 0.003; Table 2). MAM prevalence based on the other measures also increased between the pre- and post-outbreak periods (Tables 2 and 3). The prevalence of SAM using all measures was higher after the outbreak compared with the pre-outbreak period (Table 3). For example, 3.5% of screened children were diagnosed with SAM using WFA after the outbreak compared with the pre-outbreak period (1.5%, P = 003; Table 3), although the prevalence started increasing in March 2015 (Figure 2, Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Percentage of screened children diagnosed with MAM before, during and after the EVD outbreak, Tonkolili District, Sierra Leone

TABLE 3.

Percentage of screened children diagnosed with SAM before, during and after the EVD outbreak in Tonkolili District, Sierra Leone

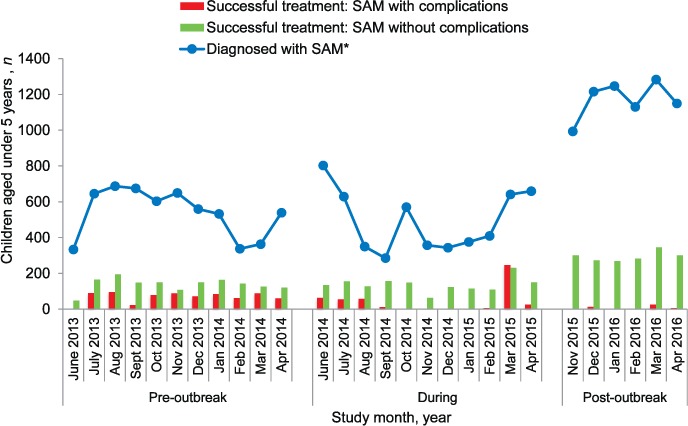

FIGURE 2.

Number of children diagnosed with SAM by weight-for-age ratios and successful completion of treatment programmes during and after the Ebola outbreak in Tonkolili District, Sierra Leone. Children diagnosed with SAM and medical complications are treated via stabilisation treatment programmes (in-patient). Children diagnosed with SAM without medical complications are treated in out-patient treatment programmes. Successful treatment was defined as the number of children discharged from stabilisation treatment programmes and out-patient treatment programmes. SAM = severe acute malnutrition.

SAM treatment completion

Figure 2 shows the monthly numbers of children diagnosed with SAM by WFA and the numbers of patients discharged from treatment (OTP and STP) over the study period. On average, one child completed SAM treatment for every four children diagnosed. The average number of children with SAM who were treated and discharged from STP per month declined from 67 pre-outbreak to 42 during the outbreak (P = 0.3). There was a spike in STP discharges in March 2015 (Figure 2). Compared with the pre-outbreak period, STP discharges declined to an average of 8 per month post-outbreak (P < 0.001). OTP discharges remained stable, at an average of 138, between the pre-outbreak and the outbreak periods (P = 0.9), but increased to 295 post-outbreak compared with pre-outbreak (P < 0.001) (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

We examined the effect of the Ebola outbreak on the screening, diagnosis and management of paediatric malnutrition in Sierra Leone. We found that screening declined during the outbreak, and that the prevalence of MAM and SAM among those screened increased post-outbreak. Across all study periods, the ratio of SAM diagnoses to treatment completion per month remained well above one.

Declines in facility-based screening for malnutrition during the outbreak were consistent with patterns observed in services for maternal health, malaria and hospital admissions across the three most affected countries.3,6,7,14 Such declines were partly due to community perceptions of and fears about contracting EVD at health facilities.8 As the number of new EVD cases in Tonkolili fell from 12 to <5 cases/week by January 2015, and to zero cases by March 2015, facility-based screening began to increase.11 The decline in outreach screening by health facilities after the outbreak began in Tonkolili was likely due to a system-wide reduction in outreach services, which had yet to return to pre-outbreak levels at the time of the study. The outbreak strategies employed by CHWs to provide care givers with MUAC tape measures13 prevented a collapse in community screening but did not make up for the shortfall. The timing and patterns of the decline, followed by the surge in facility-based (fixed) and community screening post-outbreak, suggests a major impact of the outbreak on screening services and early health system recovery.

Discrepancies in diagnoses between the MUAC and the WFA/WFH ratios are common, with an estimated 40% agreement for SAM diagnoses between MUAC and WFH ratio.12 Our findings are consistent with other studies reporting a lower prevalence of MAM and SAM using the MUAC.15 MUAC increases with age, and the use of non-standardised measurements means that older children diagnosed with SAM using the WFH ratio may not be diagnosed with SAM using the MUAC.16 As children diagnosed with MAM and SAM across the different measures may represent different subgroups of children, we restricted the comparison of MAM and SAM prevalence between the study periods to comparisons by measurement type.

The increase in prevalence of MAM and SAM diagnosed among those screened is of concern. The post-outbreak prevalence of SAM, measured using the WFA ratio, mirrors the 2010 estimates of 3.5% in Tonkolili from survey data, and is well above the national goal of <0.2%.4 The increased prevalence of SAM among children screened post-outbreak began after EVD cases in Tonkolili declined to zero/week and screening increased. Potential reasons include the possibility of underdiagnosis with care giver-provided MUAC measurements during the outbreak, leading to delayed detection once CHWs recommenced taking MUAC measurements.

The outbreak may also have increased the proportion of children with acute malnutrition. During the outbreak, there was a decline in agricultural food production and growing food insecurity.17,18 Over 12 000 children (>800 in Tonkolili District)19 lost one or both parents or care givers to EVD, and face vulnerability to poverty and malnutrition. Finally, the risk of malnutrition rose with the lack of early facility-based access to under-five services, including immunisation, leading to an increased risk of preventable childhood illness, particularly measles.20

Our findings suggest an unmet need in reducing the prevalence of malnutrition, with limited access to, and/or uptake of, appropriate management and therapeutic feeding. The low level of SAM treatment completion suggests a pre-existing health system gap that remained stable during the outbreak but worsened post-outbreak for STP and improved for OTP. The spike in STP and OTP treatments in March 2015 may reflect a surge in the reporting of treatments from previous months rather than a surge in treatments completed in March 2015, when the number of EVD cases fell to zero; we are unable, however, to verify whether this was the case. OTP may have increased post-outbreak, as it requires fewer resources, while STP requires facilities to be open, staffed and stocked with supplies for in-patient treatment. OTP may also have increased in response to the larger number of SAM diagnoses, many of which may have been uncomplicated if they represented new diagnoses. Further exploration of the root causes of the ongoing treatment gap is required.

The strengths of this study include the use of population-level programmatic data. The conduct and reporting of the study adhered to the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines and sound ethics principles,21,22 and the study was conducted to address a health-system priority for the Sierra Leone MoHS. Study limitations include the use of secondary data without validation against the original paper records. The data were extracted as monthly district-wide totals from the DHIS database, and there was a large amount of missing data on treatment outcomes for SAM, reflecting the nature of report submission and data entry into the DHIS. Because individual patient-level outcomes were not available and we used discharge from treatment as a proxy for successful treatment completion, our measure of SAM treatment outcome may not accurately reflect treatment uptake and effectiveness.

The study has important implications for Sierra Leone's health system. Prior to the outbreak, the MoHS had committed to improving child health through the elimination of fees incurred by care givers for health services provided to children under five.23 During the current recovery period, programmes targeting food security, nutrition and the loss of parents/guardians must be considered by implementers and donors looking to support paediatric services. Strengthening programmes to close the gap between SAM diagnosis and treatment is needed to address this ongoing unmet need in child health.

In conclusion, the EVD outbreak in a rural district in Sierra Leone was associated with decreased malnutrition screening during the outbreak and an increased prevalence of acute malnutrition post-outbreak. Nutrition programmes need to be strengthened to address the shortfalls created by the Ebola outbreak and to preempt such effects in future outbreaks.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted through the Structured Operational Research and Training Initiative (SORT IT), a global partnership led by the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases at the World Health Organization (WHO/TDR, Geneva, Switzerland). The training model is based on a course developed jointly by the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union, Paris, France) and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF, Geneva, Switzerland). The specific SORT IT programme that resulted in this publication was jointly developed and implemented by the WHO/TDR, the Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation (Freetown), the WHO Country Office Sierra Leone (Freetown) and the Centre for Operational Research, The Union. Mentorship and the coordination/facilitation of the SORT IT workshops were provided through the Centre for Operational Research, The Union, The Union South-East Asia Office (New Delhi, India), the Ministry of Health, Government of Karnataka (Karnataka, India), the Operational Research Unit (LUXOR) MSF, Brussels Operational Centre (Luxembourg), Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare (AMPATH, Eldoret, Kenya), the Alliance for Public Health (Kiev, Ukraine), the Institute of Tropical Medicine (Antwerp, Belgium), University of Toronto (Toronto, ON, Canada), Dignitas International (Zomba, Malawi), Partners in Health (Boston, MA, USA) and the Baroda Medical College (Gujarat, India).

The authors thank the MoHS nutrition team, the community health workers and the many individuals who worked tirelessly throughout the Ebola outbreak response in Tonkolili District and across Sierra Leone.

The SORT IT programme was funded by the Department for International Development (London, UK) and the WHO/TDR. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

In accordance with the WHO's open-access publication policy for all work funded by the WHO or authored/co-authored by WHO staff members, the WHO retains the copyright of this publication through a Creative Commons Attribution IGO licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/legalcode) that permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original work is properly cited.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. . 2014–2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. Atlanta, GA, USA: CDC, 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/2014-west-africa/index.html Accessed February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ministry of Health and Sanitation. . National Ebola Response Centre, Sierra Leone. Freetown, Sierra Leone: MoHS, 2016. http://nerc.sl/ Accessed February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Elston J W, Moosa A J, Moses F, . et al. Impact of the Ebola outbreak on health systems and population health in Sierra Leone. J Public Health 2015; E-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Government of Sierra Leone. . Sierra Leone food and nutrition security policy implementation plan 2012–2016. Freetown, Sierra Leone: Government of Sierra Leone, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Statistics Sierra Leone. . Sierra Leone Demographic and Health Survey, 2013. Freetown, Sierra Leone: Ministry of Health and Sanitation, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bolkan H A, Bash-Taqi D A, Samai M, Gerdin M, von Schreeb J.. Ebola and indirect effect on health services functions in Sierra Leone. PLOS Curr 2014; 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lori J R, Rominski S D, Perosky J E, . et al. A case series study on the effect of Ebola on facility-based deliveries in rural Liberia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015; 15: 254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dynes M, Tamba S, Vandi M A, Tomczyk B, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). . Perceptions of the risk for Ebola and health facility use among health workers and pregnant and lactating women—Kenema district, Sierra Leone, September 2014. MMWR 2015; 63: 1226– 1227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Statistics Sierra Leone. . Sierra Leone 2015 population and housing census. Provisional results, March 2016. Freetown, Sierra Leone: Ministry of Health and Sanitation, 2016. https://www.statistics.sl/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/2015-Census-Provisional-Result.pdf Accessed February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tonkolili District Health Management Team. . District Community Health Worker Database, July 2013. Tonkolili, Sierra Leone: Tonkolili District Health Management Team, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tonkolili District Health Management Team. . Tonkolili District Ebola Surveillance Report Database February 2016. Tonkolili, Sierra Leone: Tonkolili District Health Management Team, 2016?) [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Health Organization and United Nations Children's Fund. . WHO child growth standards and the identification of severe acute malnutrition in infants and children. A Joint Statement. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2009. http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/severemalnutrition/9789241598163/en/ Accessed February 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. . Recommendations for managing and preventing cases of malaria in areas with Ebola. Atlanta, GA, USA: CDC, 2015. www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/malaria-cases.html Accessed February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brolin Ribacke K J, Saulnier D D, Eriksson A, von Schreeb J.. Effects of the West Africa Ebola virus disease on health-care utilization—a systematic review. Front Public Health 2016; 4: 222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grellety E, Golden M H.. Weight-for-height and mid-upper-arm circumference should be used independently to diagnose acute malnutrition: policy implications. BMC Nutrition 2016; 1: 2. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Myatt M, Duffied A, Seal A, Pasteur F.. The effect of body shape on weight-for-height and mid-upper arm circumference based case definitions of acute malnutrition in Ethiopian children. Ann Hum Biol 2009; 36: 5– 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thomas A C, Nkunzimana T, Perez Hoyos A, Kayitakire F.. Impact of the West African Ebola virus disease outbreak on food security. Ispra, Italy: Institute for Environment and Sustainability, European Commission Joint Research Centre, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Action Against Hunger UK. . Ebola in Liberia: impact on food security and livelihoods. London, UK: Action Against Hunger, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Street Child. . The street child: Ebola orphan report. London, UK: Street Child, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Suk J E, Paez Jimenez A, Kourouma M, . et al. Post-Ebola measles outbreak in Lola, Guinea, January–June 2015. Emerg Infect Dis 2016; 22: 1107– 1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. von Elm E, Altman D G, Egger M, . et al. The STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007; 370: 1453– 1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Edginton M, Enarson D, Zachariah R, . et al. Why ethics is indispensable for good-quality operational research. Public Health Action 2012; 2: 21– 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Witter S, Wurie H, Bertone M P.. The free health care initiative: how has it affected health workers in Sierra Leone? Health Policy Plan 2015; 31: 1– 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]